|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Opus 224 (May 31, 2008). The Big News—who won the Reuben? And what else transpired in the Big Easy during the Reuben Weekend? Our Big Feature this time—Ed Stein’s Denver Square strip, the last of the local-focus newspaper strips, ends. Plus an extensive review of the annual Brooks’ compilation of the Best Editorial Cartoons of the Year—compared to Cagle-Fairrington’s similar volume. And we also ask a provocative question about the purpose of movement in an animated editorial cartoon. Without further adieu, here’s what’s here, in order, by Department— NOUS R US MoCCA Program, Dark Horse’s 20 Manga Anniversary, Fantagraphics Signs with Diamond, Danish Dozen in Canada and in Holland, The Five Most Unintentionally Hilarious Comic Strips, Gumby Rampant, Forbes’ Fifteen Wealthiest Fictional Characters CARTOONIST OF THE YEAR NAMED IN NEW ORLEANS A Full Report on NCS’s Reubens Weekend in the Big Easy Protesting the Orphan Works Act Wiley Miller’s Prognostication and Tom Heintjes’ ANIMATED POLITICAL CARTOONS Why Add Movement? PASSIN’ THROUGH Thelma Keane, Frances Arriola, & Mel Casson GRAPHIC NOVEL IN CAMBODIA EDITOONERY Cartooning Scott McClellan Charles Brooks’ Best Editorial Cartoons of the Year: A Review ONE MORE LAST BOW Ed Stein’s Denver Square Drives Off Into the Sunset Leo Garza Was Second to the Last And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this lengthy installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu— NOUS R US All the News That Gives Us Fits The program for this year's MoCCA Art Festival, the weekend of June 7-8, features a mix of animators, cartoonists, graphic artists, and writers. “Our special guests,” announced a press release, “include Jessica Abel, Rebecca Donner, David Hajdu, David Heatley, Chip Kidd, Alex Robinson, Frank Santoro, and Brian Wood. Saturday's program opens with author Blake Bell talking about his new Steve Ditko biography, and closes with Dan Nadel in conversation with Chris Forgues (CF), whose comics, according to one critic, ‘exude the ease of someone just now putting all the pieces together to make for consistent great work.’ Sunday's program opens with an illustrated history of radical cartooning, by social movement cartoonist Nick Thorkelson, and closes with a screening of new animated shorts from Scandinavia.” All Saturday-Sunday programming will be held at the MoCCA Gallery, 594 Broadway (Suite 401), just below Houston. The MoCCA Art Festival, now in its seventh year, is an annual fundraiser for the Museum of Comic and Cartoon Art (MoCCA). This year’s MoCCA Art Festival Award will be presented to Bill Plympton, is an internationally renowned cartoonist, illustrator, and animator, whose cartoons have appeared in major newspapers and magazines, from the Village Voice and New York Times to Vogue, Rolling Stone, and Vanity Fair. He is the author and/or illustrator of numerous books and graphic novels, including Hair High, Mutant Aliens, Tube Strips, and The Sleazy Cartoons of Bill Plympton. He is probably best known for his short and full-length animated films, which include “The Tune,” “I Married a Strange Person,” “Guard Dog,”and “Idiots and Angels,” which premiered earlier this year. The MoCCA Award is presented to a creative figure whose work has elevated the cartoon arts. Previous recipients include Jules Feiffer in 2002, Art Spiegelman (2003), Roz Chast (2004), Neal Adams (2005), Gahan Wilson (2006), and Alison Bechdel (2007). Disney is getting into graphic novels, reports Borys Kit at the Hollywood Reporter, with a scheme to create titles that will serve as the basis for new film projects. .. PoliticalBastards.com is the website creation of Jocelyne Leger and Mike Shelton, who both worked at California’s Orange County Register before taking buyouts in November 2006. According to Editor & Publisher, the website will feature a new animated editorial cartoon every week along with other content. ... Fun Home author Alison Bechdel is taking a sabbatical of unspecified length from her 1983-launched Dykes to Watch Out For comic strip in order to finish her next graphic memoir, Love Life: A Case Study, which has a fall 2009 deadline. Added E&P: “About a year ago, Bechdel decreased the frequency of Dykes from one every two weeks to one every four weeks. ... IDW’s forthcoming volume reprinting Noel Sickles’ Scorchy Smith will be 40 pages longer than originally intended, announced ICv2. The book will include all 900 of Sickles’ strips, the only complete reprinting I’m aware of, plus three 22x11-inch fold-outs, and Bruce Canwell’s “first-ever biographical essay” on Sickles, which has grown to 32,000 words, a trove. We examined Sickles’ watershed contributions to the medium in October 2004 in a Hindsight piece entitled “The Unsung Sickles,” here. ... Spring Lake, Michigan, will include a Winsor McCay Day on June 17 during the town’s Lake Heritage Festival, saith E&P; Spring Lake is McCay’s home town. Dark Horse is celebrating 20 years of publishing manga in the U.S. The first was Godzilla no. 1, which was reprinted from the Japanese original with a rough translation by publisher Mike Richardson and Randy Stradley, now vice president of publishing. “I couldn’t read any Japanese,” said Stradley, “but I loved the pacing of the visual storytelling.” American readers were familiar with the character, and the book stirred a positive response, which prompted the next manga publication, Johji Manabe’s Outlanders, and manga has been part of the Dark Horse stable ever since. The company set out to attract female readers in 1994, when it began publishing Oh My Goddess, and it has recently teamed with CLAMP, an all-female group of manga artists and writers in Japan, to produce new books that will be released next year simultaneously in Japan, Korea, and the U.S. Dark Horse has also begun publishing manhwa, Korean comics, reserving the term manga solely for graphic novels from Japan. In a surprising move, Fantagraphics Books has signed on with Diamond Comic Distributors for exclusive distribution of its products to the comics direct market shops, worldwide, reported Tom Spurgeon at comicsreporter.com, effectively ending FB’s longstanding wholesaling operation. When Diamond began creating its distribution universe of exclusive relationships in the 1990s, FB had stood for non-exclusive arrangements and undertook to handle its own distribution, overtly resisting Diamond’s maneuver to create a monopoly with itself at the pivot. But times change. The direct market is today dominated by Diamond, and it seems increasingly unlikely that any other distribution operation will emerge to threaten it. Resisting the monopoly no longer harbors a potential, and it costs too much. FB is “probably the largest publisher left that doesn’t have some sort of arrangement with Diamond,” observed Eric Reynolds, FB’s marketing mogul, and that “made it tough for us to penetrate the direct market in any meaningful way ... and, frankly, we got a lot of crap for not serving the direct market better,” he told indiejones.wizarduniverse.com. With FB no longer selling direct to comics shops, the publisher’s staff can devote its energies to developing other sales and promotional efforts, according to Reynolds. W.W. Norton will continue to distribute FB to the rest of the retail world, and FB will also continue its relationship with Last Gasp and Bud Plant, both of whom do business with the direct market. Some observers believe the new arrangement will have minimal “and probably positive” impact on retailers; ditto on FB itself. Some worry about Diamond’s “less than stellar reputation” for restocking sold-out titles at retail outlets, but one reason underlying the FB move could be that the company has been selling less and less through the direct market. With Diamond as its exclusive direct market distributor, FB will be able to design its own section in the monthly catalogue, Previews, thereby enhancing and strengthening its connection to direct market shops. Another reservation about Diamond arises from the company’s policies and philosophies, which, in the past, have seemed a little straight-laced for modern popular culture tastes. But Diamond, it would seem, has adopted a more realistic, market-based attitude: if it’ll sell, sell it. And Diamond has been distributing FB’s controversial and decidedly unconservative Eros (porn) imprint for some time. Meanwhile, the Fantagraphics foray into retail, its bookstore in Seattle, which opened about 18 months ago, is “doing great,” Reynolds told me. “I’m frankly surprised at how well it’s done. It’s become something of a local institution, and we have events about every other week.” The Danish Dozen continue to plague the West by provoking free speech confrontations. Canadian Ezra Levant says the Canadian government, through the Human Rights Commission, is stifling freedom of speech by trying to arbitrate what publications are allowed to print. Levant reprinted the Danish cartoons when he was publisher of Calgary’s Western Standard in 2006, and Syed Soharwardy of the Islamic Supreme Council of Canada and the Edmonton Muslim Council filed a complaint under the Human Rights Act, alleging, reported Kristen Thompson at metronews.ca, that Levant risked exposing Muslim Canadians to hatred or contempt. "There are some proper limits on free speech," Levant said, adding he agrees with outlawing treason, defamation and slander. "None of these apply to the offence for which I've been charged. We (printed the cartoons) … as a prosecutor might put a piece of evidence into court as an exhibit. There were riots overseas over (the) cartoons—here's what they looked like." He said criminalizing news reporting is Orwellian. "Are these people who truly believe in human rights, who are speaking for the downtrodden? Or are they people who pick up a weapon … against anyone who dares have a political discussion against them?" he said. "These rules are so vague and malleable they can be abused, (and) to enforce them equally would be to censor anything offensive." Muslim ire continues to raise hackles in Holland, where a freelance Internet cartoonist was arrested in early May for “insulting people,” leading one wag among American editoonists to quip: “What next? Plumber picked up for unclogging sink?” The cartoons were insulting, however, because their apparent targets were Muslims and racial minorities as well as run-of-the-mill leftists. The cartoonist, who labors under the pseudonym “Gregorius Nekschot” (“shot in the back of the neck”), was arrested on “suspicion of violating hate speech laws,” reported the Associated Press via msnbc.msn.com, and the police deployed a considerable show of force—the arresting officers numbered ten or so, suggesting intimidation on a massive scale. Both the cartoonist and his online publisher, Uitgeveri Xtra, have received death threats, aided and abetted by the Minister of Justice which released the cartoonist’s identity, exposing him to the possibility of assassination. Scarcely a wild improbability in those parts: some of his cartoons have appeared on the website of Theo van Gogh, the filmmaker who was murdered by a Muslim radical in November 2004 because of van Gogh’s unfavorable characterization of Islam. Nekschot’s work also appears in HP/De Tijd, “a major Dutch language weekly news magazine, and he has published two books. One recent cartoon on his website caricatured a Christian fundamentalist and Muslim fundamentalist as zombies who met at an anti-gay rally and now wished to marry.” Several of his cartoons (which can be seen here, you may have to keep re-trying the link, http://gregoriusnekschot.nl/) seem to me crude as well as heavy-handed, and it reminded at least one American observer of anti-Semite cartoons produced in Nazi Germany, but in the sequel, that untidy association has become somewhat obscured. The furor surrounding his arrest and release the next day revealed, according to marketwire.com, that the Dutch Secret Service has a division “dedicated to checking all the cartoons being published in the country for their political correctness,” which provoked Dutch cartoonist Peter Nieuwendijk, founder and president of the Federation of Cartoonists Organizations (FECO), “the largest cartooning organization in the world,” to take massive satirical revenge. He has called upon all the cartoonists in the world to send all their cartoons, new and old, to “the Cartoon Police of the Ministry of Justice” to flood them with work to do. Nieuwendijk also asked the Minister to appoint a few of the working group to sit in on an international cartoon competition of the Dutch Cartoon Festival of 2009 “in order to alleviate any fear of reprisals and/or uninvited police raids.” The FECO attack is supported several cartoonist organizations, including the U.S.-based Cartoonists Rights Network, International, a watchdog operation that monitors persecutions of cartoonists world wide; its website is www.cartonistsrights.com, where interested parties may obtain Dutch Minister of Justice e-mail addresses for submitting cartoons. Editoonist Chip Bok claims he is today alive because of cartooning. Jill Gosche at advertiser-tribune.com reported that when Bok was about 10 years old, his mother, hoping to get him to focus, made him sit at her dressing table to do his homework. “Before he knew it, he started to doodle and put his mother's red fingernail polish on a lamp. An explosion followed, and glass and red polish flew everywhere.” But Bok, assiduously doodling away, had his head down, and his face was thus protected from flying shards of glass. "I tell everybody cartooning saved my life," Bok said. He told this story during his presentation at the Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Center as part of the current exhibition, "Illustrating the Gilded Age: Political Cartoons and the Press in American Politics and Culture, 1877-1901.” ... And in case you ever wondered how Tom Toles works, here he is: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/video/2008/05/15/VI2008051503449.html ... ComicsDC’s Mike Rhode disagreed with my characterization last time of comic book stores as “claustrophobic storage facilities that sell their product out of cardboard boxes.” Not all comic book stores are like that, he says: “The Big Planet chain in D.C. has basically sworn off back issues and really functions more as a big store. It’s been several years since I’ve been there, but Chicago Comics was much the same way. I think the best stores are not like what you describe. ... The Internet has made some back issue business very different though, and I’m surprised that stores stick with it so much.” Mike’s right, I’m sure—there are comic book stores that aren’t claustrophobic with storage boxes of back issues. I visited one on the northern edge of the Village in New York—Fantasy World?—that was thoroughly purged of back issues and seemed to specialize in action figures and games as well as current issues of comics. But most of the stores I’ve visited over the last few years are still pretty deeply into back issues and storage boxes. ... Editor & Publisher reports that Bill Hinds, who does two comic strips (Cleats and Tank McNamara, the latter with Jeff Millar) as well as Buzz Beamer for Sports Illustrated Kids and “Buzz Beamer” animations for SIKids.com, is adding yet another feature to his life: an animated humor column called “Hindsight,” apparently for the Houston Chronicle. ... E&P also notes that editoonist Joe Heller at Wisconsin’s Green Bay Post-Gazette is joining the animation ranks, starting with “Stayin’ Alive” about Hillary Clinton. The Age of Mischief is upon us, and in commemoration thereof, we refer you to cracked.com where you may, if so disposed, find discussion of “The 5 Most Unintentionally Hilarious Comic Strips.” They include: Rex Morgan, for its homosexual innuendo; Dick Tracy, “outstandingly sub-par artwork and hilariously gruesome deaths”; Mary Worth, for its “hilariously callous approach to ruining other people’s lives”; Mark Trail, “comically nonsensical plots and misplaced speech balloons” (which inadvertently cause animals in the wild to speak); and Gil Thorp, “terrible art and theorizing about the nature of the time warp the writer is in.” You have to see it to believe it. ... The Illinois Toll Highway Authority hopes to alert drivers to construction locations and congestion through a “Know Before You Go” campaign that employs a heavily muscled but cross-eyed caped crusader called Captain Tollway. A cross-eyed strong man is probably more inhibition to guidance than help; besides, we’re already awash in longjohn legions. ... In what Publishers Weekly calls “Comics Bestsellers,” Jeff Kenney’s Diary of a Wimpy Kind: Rocerick Rules ranks at the top of the Top Ten as of June 1. Most of the rest of the list was taken up with manga graphic novels except for Batman: The Killing Joke in fourth place, Dark Wraith of Shannara in seventh, and Bone: Ghost Circles in ninth. I’ve never been a big fan of Gumby, the green glob of clay who debuted in stop-motion “clay-mation” on “The Howdy Doody Show” in 1956. As a teenager, I thought I was too old to watch “Howdy Doody,” but I was happy to read, in a recent online story from Australia, theage.com, that Art Clokey, Gumby’s creator, bought back rights to the character in 1962 and has controlled the character ever since. Gumby enjoyed a “kitschy revival” in the 1980s and appeared in his own feature-length movie in 1995. At 86, his creator is ailing, affected by strokes in 2005, but his son, Joe, born in 1961, has been immersed in the Gumby ambiance all his life. “The smell of clay and film instantly take him back to his early childhood, and many of the Toyland toys featured in the sixties episodes were raided from his toybox.” And today, Joe is running the show as another Gumby movie goes into pre-production at Clokey Studios. Joe hopes to revitalize his father’s animation technique. Said he: “Computer animation is still trying to copy the look of stop motion, but it never really works because you can’t copy ‘real life.’ There’s something really special about real lighting hitting real objects—something tactile and powerful about it.” Joe has tried to retain the essential innocence of the original series, which was infused with random ideas his father had absorbed from Buddhism, Christianity and Indian spiritual gurus. “My father had a rough childhood,” Joe recalled. “His dad died in a car accident, and his mother’s new husband didn’t want him. He was put in a halfway house, but then he was adopted as a 12-year-old troubled boy by a wonderful man. They went on trips in the summers, they went to Siberia together, and Mexico, painting in the desert, and his creativity just blossomed.” For intense fans of Gumby—and they are, I understand, legion—Shock DVD has released Gumby, Vol. 1: The ‘50s and ‘60s. Every year, Forbes magazine, which has become the world’s Foremost Authority on such subjects, lists the fifteen wealthiest fictional characters, and we’re happy to report that Scrooge McDuck, with an estimated net worth of $28.8 billion, is still the richest of the lot. After Scrooge, the rest of the top five, in order, are: Richie Rich, $16.1 billion; Jed Clampett (“Beverly Hillbillies”), $11 billion; C. Montgomery Burns (“The Simpsons”), $8.4 billion; and, in fifth place, Bruce Wayne, $7 billion. We can’t help noticing that four of the top five are the creations of cartoonists, for whom, we assume, it’s easier to conjure up fictitious fortunes than it is for screen writers or novelists, although why this should be is quite beyond explanation. Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at http://www.rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s www.povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s www.DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s www.comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, http://www.comicsdc.blogspot.com For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s http://www.strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon. CARTOONIST OF THE YEAR NAMED IN THE BIG EASY

If your newspaper runs Wiley Miller’s Non Sequitur on Sundays, you may have guessed, if you are inclined toward leaping at conclusions, who won the NCS Reuben as “cartoonist of the year.” Wiley, who drew his May 25 strip 6-7 weeks ago—making it a high-wire performance of dauntless daring or colossal cynicism (or, perhaps, cynical daring)—effectively predicted which one of the three nominees would win by congratulating Al Jaffee, the 87-year-old cartoonist famed for “fold-ins” on the last page of Mad magazine. And just to make sure we all knew who he was talking about, Wiley devoted the Sunday strip to a fold-in made by his perspicacious young heroine, Danae.

Wiley was

not alone in commemorating the New Orleans meeting of the National

Cartoonists Society over Memorial Day Weekend. Greg

Evans in Luann also dedicated his Sunday May 25 strip to his brethren in the

inky-fingered fraternity. But Wiley, by then, had already gone Evans

one better, devoting the previous Sunday to NCS and other New Orleans

disasters. Wiley’s

daring in predicting the Reuben winner this year is not quite as

stupendously audacious as it seems. In recent years, NCS arranges,

every once in a while, for one of the Reuben nominees to be a heroic

figure in the history of cartooning—Will

Eisner in 1998, Jack

Davis in 2000—and whenever that gesture

of recognition is made, the titan inevitably wins over the two other The next evening, wearing a crown and seated in a horse-drawn carriage with another Mad legend, Jack Davis, Jaffee led a parade of cartoonists flinging bead necklaces through the streets of the French Quarter, a typical New Orleans jazz band preceding the ensemble, to the dining finale of the weekend at Broussard’s Restaurant, where everyone lined up for a lavish New Orleans buffet.

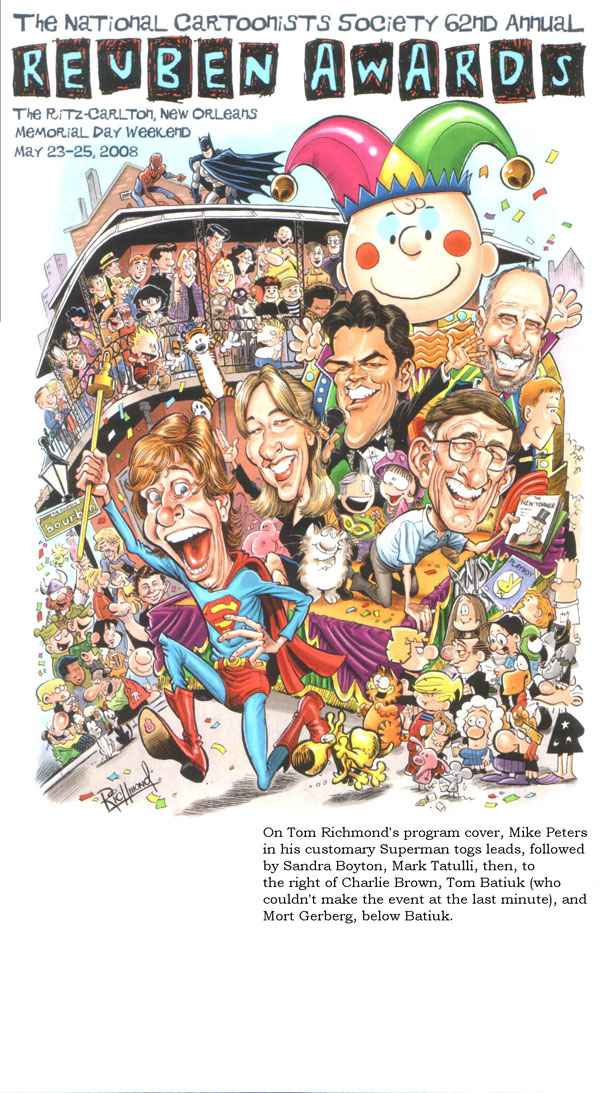

At the Reuben banquet on Saturday, Sandra Boynton, greeting card entrepreneur, Grammy-nominated song writer and comical illustrator and author, received the Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award. She also won the Reuben division award for book illustration. Earlier in the day, she had made a presentation that included a film of various personages singing songs she’d written for a children’s CD entitled Blue Moo: 17 Jukebox Hits from Way Back Never, accompanied by the illustrated book she won the award for. The songs with repetitive and dull lyrics are mostly badly sung—and that’s the intentional, and successful, comedy in the album. In her presentations, Boyton’s humor tends toward deadpan: typically, she strings together long syntactical episodes of highfallutin’ verbiage, then punctures the cumulative effect with a self-deprecating conclusion. So delicately is this sort of humor constructed that she must either memorize a script or read it; she chose to read it, both during her presentation and in her acceptance of the Caniff Award that evening. Attorney Stuart Rees was awarded the Silver T-Square for his tireless work on behalf of cartoonists and the Society, and NCS presented the first Jay Kennedy Award, named for the late highly regarded editor-in-chief of King Features, to Juana Medina, who moved to the U.S. from her native Bogota, Colombia, in 1998 to continue her studies at the Corcoran College of Art and Design in Washington, D.C., and then at the Rhode Island School of Design, where she now regularly contributes cartoons to the weekly campus magazine, College Hill Independent, produced by students at nearby Brown University and RISD. The Kennedy Award is accompanied by a $5,000 scholarship from the NCS Foundation, which, this year, received more than 200 applications. In her application, Medina wrote: “I grew up in a country where war has been a constant since long before I was born. Our voices have been quieted by terrorist acts and constant threats from both governmental and clandestine groups, up to a point where the smell of gunpowder and the countless bomb threats become a part of our daily life. ... I found situations where there is little I can do to change reality, but I have found in cartooning a voice that strongly reflects my feelings and intentions. I have found a way to raise consciousness without scolding, fuming or losing my stomach to an ulcer.” Winners of the Reuben “division awards” were also announced at the Saturday banquet. Since being nominated is as distinct an honor as winning, I’m listing here all the nominees, starring (*) the winner in each division: Comic Books—Nick Abadzis (Laika), Bryan Lee O’Malley (Scott Pilgrim Gets It Together), *Shaun Tan (The Arrivals, a graphic novel, not, strictly speaking, a comic book; Tan was not present to receive his award); Newspaper Comic Strips—Paul Gilligan (Pooch Café), *Jim Meddick (Monty; Meddick was not present to receive his award), Richard Thompson (Cul de Sac); Newspaper Panel Cartoons—*Chad Carpenter (Tundra), Glenn and Gary McCoy (The Flying McCoys), Kieran Meehan (Meehan), a Scot who also does the comic strip A Lawyer, A Doctor & A Cop; Newspaper Illustration—Drew Friedman, *Sean Kelly, Ed Murawinksi; Magazine Gag Cartoons—Benita Epstein, *Mort Gerberg, Glenn McCoy; Editorial Cartoons—Gary Brookins, Michael Ramirez, *Bill Schorr; Greeting Cards—Gary McCoy, Glenn McCoy, *Dave Mowder; Magazine Feature Illustration—*Daryll Collins, John Klossner, Tom Richmond; Book Illustration—Nancy Beiman (Prepare to Board), *Sandra Boyton (Blue Moo), Jay Stephens (Robots); Television Animation—Sandra Equiha and Jorge Gutierrez (“El Tigre: The Adventures of Manny Rivers”), *Stephen Silver (“Kim Possible”), Richard Webber (“Purple and Brown”); Feature Animation—Brad Bird (“Ratatouille”), Sylvain Deboissy (“Surf’s Up”), *David Silverman (“The Simpsons Movie”); Advertising Illustration—Jack Pittman, *Tom Ricmond, Tom Stiglich. Tom Heintjes, editor of Hogan's Alley, handicapped the strip division award competition for ComicsDC: “Three great strips by respected veterans—a very tough field that exemplifies some of the best work on the comics page today. Should Win: Meddick produces a strip that every other cartoonist loves, and it has completely transcended its roots as a spinoff of a toy. While Cul de Sac and first-time nominee Thompson will win much hardware in years to come, the strip is probably too new to win, without even a full year under its belt. Still, its inclusion among the nominees demonstrates the respect it has already earned. Will Win: Who needs a robot? Meddick wins this award for the first time, an overdue honor." Heintjes, as we see, did better as a prognosticator than Wiley Miller: the strip division is less fraught with actuarial likelihood than the Reuben competition; see Footnit below. Mike Peters, editoonist and creator of Mother Goose and Grimm, was Master of Ceremonies for the Reuben Banquet, taking the podium vacated after last year by Dan Piraro. Peters’ performance included ripping off his tear-away tuxedo to reveal, beneath, the Superman suit he always wears under his street clothes, and a riff on Patrick McDonnell’s Mutts, to which Peters could not help but compare his own strip that also features a dog and, occasionally, a cat but, alas, has never won accolades for animal activism like Mutts has. Peters began by saying how wonderful Mutts is, then he recalled that every time he opens Editor & Publisher, he sees yet another article extolling the public-spirited virtues of “the goddamn Mutts” for spotlighting the good work of yet another animal shelter. Peters announced his decision to try for similar commendations by devoting future Grimm installments to representing an underrepresented and abused species—bugs, say, tape worms in particular. His remarks were illustrated by pictures of Grimm with a tape worm partially protruding from the dog’s, er, anus, saying, “It’s really dark in here.” Hilarious, but you probably had to be there. At afternoon seminars on Friday and Saturday, we contemplated gag cartooning, cartoonist biography, and comic stripping. Mort Gerberg began a brief review of his career by noting that when he started out, he was told magazine gag cartooning was a dying craft. Twenty years later, he was told the same thing; and, even now, still more years later, he hears the mantra. He showed cartoons from a recent collection of gag cartoons he edited on death and dying and old age, Last Laughs (which we reviewed here in Opus 218). Nancy Goldstein talked about her research into the life and cartooning artistry of Jackie Ormes (Goldstein’s biography, Jackie Ormes: The First African American Woman Cartoonist, is reviewed in Opus 219). And then Mark Tatulli, who draws both Heart of the City and Lio, made a presentation that concentrated mostly on the protest mail he gets about Lio’s corrupt morality. “All I ever wanted was to do a comic strip,” Tatulli began, “and now, with two daily strips, all I ever do is comic strips.” Tatulli, erstwhile art director in film and tv, did at least two comic strips before hitting on Heart of the City, his first strip to endure. Mr. Fipps, focused on a junior high teacher, was his debut strip; then came Ben Halos, about a couple of ne’er-do-well angels. Heart of the City, featuring a little fun-loving city girl and her single mom, began November 23, 1998, and is now in 80-100 strips, not enough to make a living for Tatulli, so he concocted Lio, which started May 16, 2006; and Lio, being about the perverted amusements of the young, is in 300 or more newspapers. It’s a living. But Tatulli’s daily life is fraught with letters from irate readers, mostly tightly-wound religious enthusiasts, who object to the Satanism they see lurking in every Lio panel, or “concerned citizens,” who see Nazism or some other perversion in the strip. Tatulli showed some of the strips that had inspired the most virulent correspondence and read the letters. Very revealing—I am forever astonished at the wondrous torque the average mind can achieve if set loose among the civilized world.. I asked if any of his correspondents realized that he drew both Heart and Lio. Apparently not. Tatulli suggested that he use a pen-name for Lio, but his syndicate, Universal Press, advised against it. He signs the strips differently, but some newspapers print the cartoonist’s name next to the strip’s title, so illegible signatures might not always help in protecting Tatulli from attack by outraged multitudes.

Attendance at this year’s Reuben weekend reached almost 350, including the spouses and families of cartoonists and syndicate representatives; of that number, slightly over half, about 180, were cartoonists, practicing and retired. Mort Walker was not present this year for the first time anyone can remember, due to illness in his immediate family; and Bil Keane, the legendary longtime emcee of the proceedings, was also absent: his wife was dying of Alzheimers; see our report down the scroll. During the weekend, many cartoonists signed letters about the Orphan Works Act that NCS subsequently forwarded to the appropriate congressmen. The Orphan Works Act of 2008, if adopted, will modify copyright law. The letter explains cartoonists’ objections: “Under the Orphan Works Act, any person or company desiring to use my work for free need only conduct a ‘diligent search’ for me. If the search fails, the image is deemed ‘orphaned.’ The key requirement of a diligent search will be to run the image through privately owned and managed databases. I (the artist) will be asked to pay to digitize every cartoon I’ve ever published, and then pay again to have it catalogued in the databases of private for-profit companies. The average cartoonist has thousands of images, so the cost of compliance will be exorbitant and most cartoonist simply will not be able to afford it. Furthermore, regardless of the type of third party use and regardless of my efforts to register my works with the Copyright Office and private databases, if I discover an infringing use, I will only be entitled to the amount paid on the open market between willing sellers and buyers in similar deals. Since there will no longer be penalties for infringement, the Orphan Works Act actually encourages, rather than deters, infringement. I strenuously object to commercial enterprises using my work for free in the pursuit of profit and then only having to pay me a modest amount if I somehow catch them in the act.” At posting time, I don’t know of the outcome of the pending legislation, which was introduced, reportedly, at the behest of Google, seeking, no doubt, to extend its tentacles. Since I am too deaf to hear much of what is said at the various podiums of the festivities, my most satisfying hours were spent in informal conversation between sessions and at meals. Joe Wos, Executive Director of the Toonseum, told me the museum is hoping to move into its own facility soon; it opened as a gallery in the Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh last fall. Over a succession of drinks and finger-food, I talked with Ron Evry, who produces a daily podcast featuring the funniest stories from the public domain, usually by persons almost wholly unknown to today’s readers; http://slapcast.com/users/revry. I got acquainted with Allan Gardner, one-time editorial cartoonist in Utah, father of triplets plus one, and now proprietor of dailycartoonist.com. Gardner knows the identity of the Bad Cartoonist but isn’t talking (sworn to secrecy); he thinks Editoonery’s Evil Eminence, who has gone to ground since early March, may re-surface on the eve of the annual convention of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists (AAEC) in late June. I got better acquainted with John Read, editor/publisher of Stay Tooned magazine, copies of the first issue of which were floating happily around the premises while Read dashed hither and yon, interviewing various personages for the second issue, out this summer. Brian Walker told me someone is working on a biography of George Herriman—about whom, I’d say, after 1986's Krazy Kat: The Art of George Herriman by Patrick McDonnell, Karen O’Connell and Georgia Riley de Havenon, not much more is likely to be uncovered. Walker is working up a succession of exhibits at the Schulz Museum in Santa Rosa on the languages of cartooning: the first, on the “language of lines” in comic strips, has already opened; next, the language of personality and character; finally, the language of place. We also talked about the forthcoming “complete Beetle Bailey” to be published by Checker, reportedly out last month; and a compilation of all of Sam’s Strip, due from Fantagraphics in the fall. Mell Lazarus is working on a third novel; his first, The Boss Is Crazy, Too (based upon his experiences as comics editor at Toby Press, publishers of Al Capp enterprises), was followed by a second, Neighborhood Watch. Lazarus’s Momma is still a spritely pest of a relative after 38 years in syndication. “Doing it is a habit,” Lazarus remarked to me when I expressed glad amazement that it was still going; Miss Peach, his earlier (1957) creation, was similarly long-lived: it ended after 45 years. I talked with Stan Goldberg for a while about his career with Stan Lee in the early days of the Marvel Universe. Goldberg was in charge of color, and he noted, with a grin, how all the villains wore dark costumes and the heroes, brightly-hued duds. I also talked with Dan Martin, who has been drawing the 100-plus-year-old Weatherbird at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, about the exhibition he recently assembled of art by cartoonists who were born or bred in St. Louis, including, among other luminaries, Al Hirschfeld. I escaped the asylum occasionally during the weekend to dip into a beignet and chicory coffee at the Café du Monde (“It seemed like an ordinary day until I had coffee with Jesus at the Café du Monde”—dunno who said it, but it was posted on the wall of the establishment and I admire the wave length) and to divest a dozen or so half-shells of their oysters at Felix, a French Quarter landmark. I also wandered into Jack’s Gallery, where prints of Al Hirschfeld caricatures were going for $1,900 to $2,800, and Tom Everhart’s interpretive lithographic prints of Peanuts characters were exhibited at prices I don’t even want to contemplate long enough to report them here. Everhart, the docent of the place told me, is the only person officially authorized to use Peanuts images—provided he laminates the characters with his own visual interpretations and doesn’t imitate Schulz’s. Cleavage was on display almost everywhere among civilians, but I saw no barenekidwimmin, alas, except on the posters plastered at the doorways of Bourbon Street dives. You could hardly see them, though, because of the high decibel racket made by the so-called bands within. At the few souvenir shops I stepped into, I looked for my favorite T-shirt slogan—“Let the Good Times Roll” in French (which comes out something like “Laissez le Bontemps Rollez,” not French at all, I ween)—but found not a remnant of this vestige of yesteryear. Voodoo stuff is big now, the T-shirts bear smutty slogans (below a picture of scantily clad bimbo holding a crab or lobster, “Shuck Me, Suck Me, Eat Me Raw”), and all the little figurines are of alligators in jazz bands. I admired a sign—“It is our aim to keep this toilet clean. Gentlemen: Your aim will help. Stand closer: it’s shorter than you think. Ladies: Please remain seated during the entire performance”—but bought only a couple of books: Blues Poetry, selected and edited by Kevin Young, and Mysterious Marie Laveau, Voodoo Queen by Raymond Martinez, wherein I learned that the success of Marie Laveau (1794-1881), a mulatto in a community “where culture was high and the Christian religion eminent,” was due largely to her canny decision to mix voodoo practices and beliefs with those of Christianity. She had statues of saints, incense and holy water in her residence as well as the Alabaster box, the black cat, and the rooster. Gris gris and holy water. As hairdresser to the elite of New Orleans, she also knew the right people—the wives and mistresses of the rich and famous, from whence she derived knowledge that made her feared and therefore powerful. Years ago in one of my former lives, I managed a convention in New Orleans at which the alleged great great granddaughter of Marie Laveau was engaged to make a presentation. My assignment, she told me, was to meet her back stage with a bottle of Johnny Walker. She took a few healthy belts from the bottle, consuming about a third of it, then went on stage in her flowing robes and performed her “act,” a ranting ritual by which she insulted white people for being racist. The crowd, mostly white and all liberal-minded school teachers, sat and took it as though they, personally, deserved it. Gris gris indeed—it has powers still. Not much evidence in the French Quarter of Katrina’s ravages: the Quarter is on some of the city’s high ground and wasn’t deluged. Wind and rain but no flood waters. Elsewhere in the city, though, particularly in the Ninth Ward, few houses remain. Still. Years afterwards. The Big Easy has become the Big Shame of America. As a preamble to the weekend’s festivities, on Friday, members of NCS helped Habitat for Humanity build houses in the desolated neighborhoods. Making a presentation during the Reuben Banquet, Arnold Roth commended his colleagues for their good work, adding that while they were out pounding nails in planks and building houses, he and a few others had been “down in the bar, building a habitat for drunks, which,” he added, “is harder than it seems.” Most things, sadly, are. But it’s easy to take good photographs in a picturesque locale, as witness the accompanying views of Veaux Carre (“Old Square” in French, a reference to the original New Orleans, which was, then, what we now call the French Quarter).

P.S. Drat: this keyboard, for all its spellcheck encumbrances, doesn’t know that necklace isn’t spelled neckless. Footnit: Incidentally, Wiley claims no special insight in predicting Jaffe’s win: “Really, it was a no-brainer,” he told me. “When I saw he was a nominee, I got to thinking, who was NOT going to vote for such a beloved icon as Al Jaffee? He's 87 years old and everyone loves him! He might have even gotten Dan Piraro's and Dave Coverly's vote! It's not a matter of bias on the part of the NCS, it's simply human nature. And as cartoonists, we're supposed to be observers of human nature... and I know the membership of this organization all too well. So this was really a one-time deal. Ordinarily, you can't really tell how the voting will go for the Reuben or any of the division awards. I had several people ask me if I had some ‘inside information’ on the Reuben winner. It just made me laugh. Can you imagine anyone less likely than me to have any inside information on anything within NCS? [Wiley has been highly critical of some NCS machinations in the past.] Besides, they do hold that information very tight, as they should. I sent Jeff Keane [NCS President] a copy of the strip several weeks ago, just to give him a head’s up, and I got no hint from him one way or the other on the accuracy of the cartoon.” I’m glad Jaffee won—as are his legions of admirers in the profession, all declaring that the recognition was long over-due and the recipient indubitably deserving. I agree, heartily. But the constellation of such sentiments suggests that, with Jaffee—as with Eisner and Davis—the Ruben was conferred in recognition of a lifetime of superior achievement in cartooning, not, as denominated in the award’s descriptor, for something the recipient had done in the previous twelve months that qualified him to be “cartoonist of the year.” Some suggest that when NCS decreed a dozen years ago that no cartoonist could win the Reuben more than once (after Bill Watterson and Calvin and Hobbes had won in 1986 and again two years later), the Reuben effectively became the “lifetime achievement award,” not the “cartoonist of the year” award. And the apparent confusion of purposes that hovers over the winners of recent years seemingly supports the contention. Until you delve further back in history—before the one-to-a-cartooner dictum—and find such Reuben winners as Otto Soglow (in 1966), Walter Berndt (1969), Bob Dunn (1975), and Ernie Bushmiller (1976) and discover that NCS has a healthy tradition of giving the Reuben as a “lifetime achievement award.” So Eisner, Davis and Jaffee are scarcely recent phenomena: the Society has always been confused. Read & Relish It's not whether you win or lose, but how you place the blame. When blondes have more fun, do they know it? Learn

from your parents’ mistakes: use birth control. ANIMATED CARTOONS The New Yorker Starts Moving, with Instructive Implications for Editooning To wax theoretical for a nonce or two, if you’re going to animate a cartoon, you do it, presumably, because the comedy will be enhanced by the motion. If movement fails to raise the risibles, why animate? As political cartoonists on every hand scramble to make their cartoons Internetworthy by animating them, the question assumes a more than casual consequence. Movement alone, in and of itself, isn’t necessarily funny, so the way something is animated is critical. Walt Handelsman at Newsday earned a Pulitzer a year ago with a portfolio of cartoons half of which were animations. One of his more notable creations subsequently was a cartoon commenting on the “three o’clock in the morning phone call” at the White House, a tv ad that Hillary’s troops had concocted a month or so ago. Handelsman’s animation depicted a terrorist in beard and turban phoning from a rocky hillside, presumably to send a shock wave of alarm pulsing through the presidential manse. But he would be forever stymied: his phone call got stuck in a cycle of voice mail instructions—“To complain in English, press one; to complain in Spanish, press two” and so on. Or words to that effect. The cartoon was not so much a comment on the folly of the theory embodied in the “three o’clock phone call” proposition as it was, instead, a wry assault on the intolerable frustration induced by an encounter with the mechanical incomprehension of voice mail routing contrivances. The animation consisted mostly of portraying the mounting exasperation of the telephoning terrorist. The cartoon could achieve much the same measure of comedy as a static picture with a speech balloon coming from the phone in the terrorist’s hand, saying, “To complain in English, press one....” Animating the feelings of the frustrated terrorist enhanced a dimension of the comedy thereby justifying the addition of movement, but the comedy being enhanced was not directed at the foolishness of making a “three o’clock phone call” a criterion for judging Presidential aptitude. Animating the terrorist’s feelings made him a sympathetic character: the more frustrated and exasperated he became, the more he was like us—our common humanity insulted by the unfeeling recording of a voice that doesn’t comprehend us. Did Handelsman want to make us feel sympathy and a common identity with a would-be terrorist? Probably not. But this discussion has already gotten entirely out-of-hand, moving off into thickets of contention that I hadn’t anticipated when I started off. Telling though the analysis of Handelsman’s animated political cartoon may be, the question is: Does the addition of motion to the basic idea of the cartoon—the impenetrability of the White House voice mail system (indeed, the voice mail system of any enterprise these days)—enhance the comedy and therefore the intensity of the ridicule embodied in the cartoon? Yes, it does. But it also has the effect of pointing the cartoon in a somewhat different direction than Handelsman may have intended. Still the question about animation remains. Shouldn’t movement enhance the comedy? In animated political cartoons, the question assumes a practical dimension to the extent that political cartoons have some application to government, prodding politicians to take meaningful societal actions rather than wholly self-serving ones. In ordinary animated cartoons, however—where simple wholesome laughter is the object, not political action—the question reverts to its entirely theoretical import. Not entirely: the laughter provoked by any cartoon—any joke—is essentially satirical, and ridicule has a societal by-product, nudging us all into better behavior, behavior that will not make us ever again the object of scornful giggling. But non-political animated cartoons seem to have less programmatic purposes. In such cartoons, then, we can study, with less distraction, the comedic function of movement. And The New Yorker has thoughtfully provided the means to this purpose. At newyorker.com, we can discover a department of “ten second animations of ‘classic cartoons’” that might reward study with an answer to our query. Each of these animated cartoons began life as a traditional, static, motionless, cartoon. Motion has been added. The question of what sort of comedy, if any, the addition of motion provides should therefore be evident. And so it is. In some instances, the motion adds comedy; in others, the motion is clearly fabricated for the sake of motion and adds nothing. In the latter category, we have a cartoon by “BEK” (Bruce Eric Kaplan), which, at first, looks like any other BEK cartoon: in it, a stolid-looking woman stands with her feet planted about a yard apart as if she expects to stop the forward progress of any SUV careening her way simply by being a determinedly immovable object. She then speaks; her lips move. And, having spoken, she turns and leaves the room. The motion here adds nothing to the interlude except the illusion of life that movement imparts to any drawing of a person. Another of the “classics” is Bob Mankoff’s cartoon of a man standing at his desk and saying into the phone: “Tuesday—no, not Tuesday. How about never? Is never good for you?” The animation here consists entirely of what we might call “the pull-away”: at the beginning, the camera is in tight close-up of a datebook which a hand and finger are pointing to; as the man talks, “Tuesday—no, not Tuesday,” the camera pulls back, slowly revealing the man who belongs to the hand, and ends, just as the man finishes talking, with the full picture of the original static cartoon in view. Movement here adds nothing; it is simply movement added in order to qualify Mankoff’s cartoon as “animated.” Movement adds nothing to P. Steiner’s cartoon of two dogs seated in front of a computer, one dog saying to the other: “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.” Movement, here, consists entirely of the dog’s mouth flapping as he talks. One by Mick Stevens seems improved by the addition of motion under the heading “April Showers,” a walking man stops when a drop of water hits him on the head, and then he falls down when hit by a giant letter “I,” followed, immediately, by “R” and “S,” leaving him prone on the pavement. April showers indeed. I inspected a few others and found no Tex Avery in evidence anywhere. Avery’s comedy was the hilarity of extreme movement, high-speed action, which, by its very exaggeration, was humorous. Nothing like that here. Perhaps New Yorker cartoons, by their very nature somewhat inert, are poor candidates for animation. Perhaps no cartoon that begins as a static vignette is a good candidate for animation. And since most editorial cartoonists begin their professional lives making static pictures, they may not be good candidates to be animators. For animated cartoons, you need Tex Avery, not Bob Mankoff. Passin’ Through Coincidence, that unexpected convergence of two otherwise unrelated events, usually brings a smile to the lips. This one, however, brings a lump and a tear, a lump in the throat and tears in the eyes. The inspirations for two beloved comic strip characters died on the same day, May 23, the first day of the annual meeting of the National Cartoonists Society: Thelma Keane, who was the Mommy character in Bil Keane’s Family Circus, and Mary Frances Sevier, who leant her name and Southern accent to a lovable Texas millionaire’s imperious daughter in Gus Arriola’s Gordo. “Thel,” an Australian by birth but an American since 1948 when she married Keane and moved to the U.S., died at an assisted living facility near their home in Paradise Valley, Arizona. She was 82. Keane told Amanda Lee Meyers at ap.google.com that when Family Circus first appeared in 1960, Thel “looked so much like Mommy that if she was in the supermarket pushing her cart around, people would come up to her and say, ‘Aren’t you the Mommy in Family Circus?—and she would admit it.” The Keane offspring, sons and daughter, and Bil Keane himself comprised the rest of the family in the cartoon. Thel filled another role in Keane’s shop: she was also his business and financial manager. Based upon her recommendation, “Keane became one of the first syndicated newspaper cartoonists to win back all rights to his feature,” Meyers wrote. Said Keane: “There was nothing I did in the cartoon world or in the business world that she wasn’t the instigator of, and she certainly deserves all the credit that I get credit for.” They met during World War II in a war bond drive office in Brisbane, Australia, where Bil worked as a promotional artist for the U.S. Army and Thel was an accounting secretary. She was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s about five years ago, but she was singing and dancing at her birthday last month when the family visited her. “We all had time to say goodbye in the end,” said her daughter, Gayle. Keane said his wife may be gone but she is still with him. “Losing Thel is a heartbreaking thing for me,” he said. “However, it makes me realize how important she was to my worldly success, and I know where she is now. I feel that she’s still helping me and probably giving me the inspirations you can only get from an angel in heaven.” She is survived by her husband and five children, including Jeff, who has been finishing the cartoon for his father in recent years and is now president of the National Cartoonists Society, and Glen, an animator in the Disney Studios. ***** Frances Arriola, whom Gus called “Fran,” died at home of myeloma fibrosis, a bone marrow disorder in which not enough red blood cells are produced; she was 94. She and Gus met when they both worked at MGM, Gus as an assistant animator and Frances as a painter in the ink and paint department. She was born in Deming, New Mexico, but most of her childhood had been spent in Monroe, Louisiana, where she acquire her languid accent. They met at a studio Christmas party in 1939, when Gus managed to maneuver her, a recent divorcee, under the mistletoe. “He kissed me,” Frances remembered. “He just came up and kissed me, and then he turned around and walked off down the hall—.” “I was entranced,” Gus said. “I was in shock,” Frances said, “—who was that?” Gus started leaving comic drawings on her desk after that, and they began having lunch together, taking their brown bags of sandwiches with them as they strolled around back lot no. 2, looking at the sets and the occasional movie star. “I chased her all over the back lot,” Gus said. “Harpo Marx and Groucho and Mickey Rooney chased her, too, but I caught her.” But not until he went into the Army in the fall of 1942, a year after Gordo had started and a year after Pearl Harbor. Gus went to Culver City to the First Motion Picture Unit at Hal Roach Studios while Frances continued at MGM, now producing animations for the Navy, and when the Navy announced that it intended to draft her and some of her co-workers as WAVES and send them to Washington, Gus intervened. “Gus didn’t want me to go,” Frances said, “and so I said, ‘Well, okay then, we’ll get married.’” And they did, on January 16, 1943. They set up housekeeping at an apartment within walking distance of the post, and Gus lived at home, spending evenings and weekends producing a Sunday only Gordo. Their son, Carlin, was born January 23, 1946, the same day Gus was discharged. “We got out together,” Gus would quip. By the time Carlin was in grade school, he was inspiring gags for a character in the strip, Gordo’s nephew Pepito. And when they were both about ten, Gus introduced a little girl into the strip, the spoiled brat daughter of a Texas oilman who even has her own personal valet—“smahty butlah,” the long-suffering Ashmead. She had the same name—first, middle, and maiden last—as the cartoonist’s wife, and her Southern accent was also borrowed from Frances. Gus always denied that he borrowed any of the comic strip character’s haughty mannerisms from his wife: the kid in the strip was named after Frances because of her accent, not her attitude. “When I first met her,” Gus told me, “Frances had a real deep Southern accent.” And he enlisted her to help him with the girl in the strip. “I had her dream up her accent again—she’d sort of lost it by then,” he said. “I would give her lines to say—the written speeches for the character—and she would say them, and I’d write them down, spelling them phonetically to get the sound right.” From this unique collaboration emerged one of the strip’s most distinctive personalities. And

Frances helped in other ways, too: she was a sounding board for gag

ideas, and she sometimes filled in solid blacks in the strip. As

Carlin grew older, he joined his mother in helping his father refine

gags, even coming up with jokes. It was a team. It was broken up in

1980 when Carlin died of complications from injuries received in a

car accident in From Editor & Publisher: Cartoonist Mel Casson has died in Connecticut at the age of 87, King Features Syndicate reported. Casson illustrated Redeye, a parody about a 19th-century tribe of Native Americans, and then scripted the strip too, after Redeye writer Bill Yates retired in 1999. The Boston-born Casson signed a cartooning contract with The Saturday Evening Post at the very young age of 17. He also drew for other magazines as well as The New York Times. After highly decorated service in World War II, Casson created the syndicated Jeff Crockett strip. Then he served in the Korean War before starting the syndicated Sparky and Angel children's panels. Casson subsequently collaborated on the It's Me Dilly comic and later the Mixed Singles strip that evolved into Boomer. Casson, whose cartoons have been published in five books, also did advertising art. And he served as a writer-producer for ABC-TV, where he created the shows "Draw Me a Laugh" and "You Be the Judge.” GRAPHIC NOVEL IN CAMBODIA Verbatim from time.com by Krista Mahr; April 10, 2008 When French-Khmer graphic artist Ing Phouséra—or Séra, to use his pen name—first started drawing comics about life under the Khmer Rouge, he didn't have a lot to go on. He had fled Cambodia as a teen in April 1975, when Phnom Penh fell to Pol Pot's forces, and had lived in Paris his whole adult life. Visual arts—except in the service of propaganda—were banned during the four years of Khmer Rouge oppression, leaving scant images of a period in which nearly 20% of Séra's compatriots died. So he used his imagination, and in 2005 tentatively staged an exhibition of the results in Phnom Penh—his first back on home soil. "I was there with my drawing, talking about a period I didn't know," says Séra. But the gamble worked. "When Cambodians came to see it, they were shocked. They said, 'It was like that.'" Growing up in Phnom Penh between the worlds of his French mother and Khmer father, Séra routinely escaped into the pages of French comics, and again as a young refugee in Paris. Now the author of a dozen graphic novels—three of which have been about Cambodia's war years—he is working to rekindle Cambodia's interest in the art form. Since his debut showing in Phnom Penh, he has been regularly returning to the city of his boyhood to hold workshops for aspiring illustrators. "It's important to try to approach the reality of our times," he says. "This is a media that only needs a pen and paper to express something." He is also helping to publish the nation's first anthology of up-and-coming comic-book artists, (Re)géné Rations: The New Khmer Graphic Novel, due in June. In so doing, Séra and his collaborators are blowing the dust off a subculture that has endured decades of neglect. Cambodia started printing domestic comics in the mid-1960s, according to Our Books, an organization that archives comics that survived the war and promotes comic-book culture in Cambodia. Though many of that generation of artists were killed, some survived the Khmer Rouge years by drawing agricultural plans for the regime, or sketching small portraits of soldiers in exchange for food. After the Vietnamese deposed Pol Pot in 1979, comics enjoyed a bright but fragile re-emergence in the 1980s, gaining a foothold in Phnom Penh's markets before the onslaught of television, movies and video that coincided with Cambodia's ensuing recovery and development. Other Asian countries had comic-book cultures resilient enough to adapt to the explosion of electronic media; unable to do the same, Cambodia's artists produced work that lay unpublished in boxes and drawers. That the revival of their fortunes should have begun halfway around the world, at Séra's Parisian drawing table, is not entirely surprising. "The Khmer diaspora has had interesting effects on Khmer culture," says John Weeks, the assistant managing editor at Our Books. Filmmakers and novelists who fled Cambodia have helped map out a record of its struggles, and émigré communities have been instrumental in keeping traditional dance and music alive after many of its best practitioners were persecuted. Séra obeyed the same impulses as many artistically minded exiles, but although he had been publishing his drawings since he was 13, it took years before comics were accepted as a suitable form for the weighty subjects he wanted to tackle. Séra started his first graphic novel about Cambodia, Impasse et Rouge—chronicling the years just before the Khmer Rouge—in 1987, five years before Art Spiegelman's Maus would win a Pulitzer for its famous depiction of the Holocaust and demonstrate that gravitas and the graphic arts were not mutually exclusive. Impasse et Rouge wasn't published for almost another 12 years. Although the following two titles about Cambodia, L'Eau et la Terre (2005) and Lendemains de Cendres (2007), were picked up in fairly quick succession by the major French comic publisher Delcourt, Séra has still not had the international success that "serious" comic books artists like Spiegelman, Daniel Clowes (Ghost World) and Marjane Satrapi (Persepolis) have enjoyed. Sera teaches drawing by day and works as a night porter at a Paris hotel to get by. For Séra, returning to Cambodia every year thus offers a chance to draw new artistic energy from—and pass on experience to—the young artists he is mentoring. Like him, the contributors to (Re)géné Rations show a willingness to tackle tough subjects—chief among them the trials of daily life in Cambodia. Developed during a series of workshops between 2005 and 2007, the students' panels, which range from simple black-and-white line drawings to detailed, full-color illustration, show street kids panhandling for change and people eking out other precarious livings, like a woman gathering lotus pods to sell in the city. Not that the artists will be better off if they intend to make a living from drawing alone. It's cheaper for small printers in Cambodia to publish a reprint of an older comic than to buy rights to a new story, and literacy rates in the country remain low. "People have the decks stacked against them a little bit," admits Weeks. For Séra, however, money has never been the point—facing the difficult realities of the nation's present is, and that goes hand in hand with facing the atrocities of the past. "I try to give some sign of those times," he says. "I try to tell people: Don't forget." EDITOONERY Afflicting the Comfortable and Comforting the Afflicted Scott

McClellan's Book Is Fodder for Many Editorial Cartoons Editorial cartoonists have done dozens of drawings about Scott McClellan's new book during the past two days. Some cartoonists enthusiastically supported the former White House press secretary's criticism of George W. Bush for actions such as the push to invade Iraq. Others wished McClellan had broken with the president earlier, and some said the author turned turncoat for the money. A few cartoonists also seconded McClellan's slam of the media for being too soft on Bush. For instance, J.D. Crowe of the Press-Register in Mobile, Ala., drew McClellan telling the media: "I was a shill for the Bush/Cheney propaganda machine, and you took everything I said at face value." One press member in the audience thinks to himself: "We're pathetic." Ann Telnaes of CartoonArts International/New York Times Syndicate shows a media person as a sheep reading McClellan's What Happened book and saying: "We weren't that baaad, were we?" Telnaes did a second cartoon picturing coffins of American soldiers coming out of a plane. "Now McClellan tells us...," says a voice coming out of one of the flag-draped boxes. Bruce Plante of the Tulsa (Okla.) World shows McClellan saying: "Can you imagine what might have happened to me if I had told the truth sooner?" In the next panel, a veteran who lost a leg in Iraq comments: "Yeah, I've been thinking about that a lot myself." Signe Wilkinson of the Philadelphia Daily News and the Washington Post Writers Group (WPWG) pictures the What Happened author signing books at a table labeled "Scott McClellan: The War I Pimped Was a Mistake." A disabled Iraq War veteran rolling by in a wheelchair comments: “Thanks for letting me know." Nick Anderson of the Houston Chronicle and WPWG shows Bush asking McClellan: "Where's your loyalty to the administration?" The former press secretary stands there mute with knives in his back labeled "Rove" and "Libby." Rob Rogers of the Pittsbugh Post-Gazette and United Media shows Bush looking at a photo of McClellan and saying: "I'm disappointed. This is NOT the obedient mouthpiece for lies and propaganda that I came to know and love." Among the artists critical of McClellan was Indianapolis Star/Creators Syndicate cartoonist Gary Varvel, who draws McClellan telling the press "I never said the Iraq War was a mistake" while thinking to himself "until I had a lucrative book deal." Steve

Kelley of the Times-Picayune in New Orleans and Creators shows McClellan saying: "During my

years as press secretary, I distorted and deceived, equivocated,

prevaricated, invented, misrepresented, and fudged for the Bush

administration. It's all in my new book." A MORE OF THE BEST Every year, I acquire both of the annual compilations of the “best” editoons of the year—Daryl Cagle’s Best Political Cartoons of the Year and Charles Brooks’ Best Editorial Cartoons of the Year, each titled suffixed with the year of the book’s publication rather than that of the cartoons. So Brooks’ current offering proclaims that it is the “2008 Edition” even though the cartoons within were all published in 2007. Just one of those oddities of publishing, kimo sabe; not to worry. I buy both tomes every year for the usual assortment of reasons: to compare them in a review here at Rancid Raves, to have a ready reference of the work of the nation’s political cartoonists over the years, and to properly enjoy of the national comedy that is our government, with its sundry social and cultural and celebrity sideshows. You’d think you wouldn’t need to buy both volumes in order to achieve the more rational of these objectives (the last-named two): the “best” cartoons are the “best,” after all, so two collections are redundant. What’s in one would also be in the other. Alas, as you may’ve guessed, not true. Now that Brooks’ 2008 Edition has arrived (206 8.5x11-inch pages, b/w; paperback from Pelican, $14.95 or $11.96 online at www.PelicanPub.com), we have at hand vivid refutation of this supposed commonsense notion. Clay Bennett, without quibble one of the country’s best editorial cartoonists, has four cartoons in Brooks and seven in Cagle without a single redundancy. How, you might quite understandably ask, can that be? The “best” is the “best”: surely, allowing for some variation not to say eccentricity in the assorted powers of human discernment, one or two of Bennett’s cartoons would be in both books. Nope. And the reason is incumbent in the methods of selection employed by the editors. Cagle, working with his co-editor Brian Fairrington, selects all the cartoons in his book. On the other hand, Brooks, who has been editing this series since its inception in 1973, is the second judge of the caliber of cartoons in his book: he selects from the five cartoons that individual editoonists have submitted. In effect, then, the “best” cartoons that comprise Brooks’ book are what the cartoonists say are their “best” work of the year. Cagle, whose 2008 Edition is reviewed here at Opus 217, says that when cartoonists are invited to pick their own “best” work, they invariably choose “important” cartoons—cartoons about Iraq, civil rights, the walking wounded, landmark legislation, and other large issues—and overlook the array of cartoons they’ve produced on such trivial subjects as Paris Hilton, Britney Spears, Larry Craig in the men’s room at the airport, and so on. In Cagle’s view, a compilation of the year’s “best” must embrace the “best” of what cartoonists actually cartooned about, the inconsequential as well as the momentous. And so that’s what he and Fairrington aim for. On four of the five cartoons Bennett submitted as his five “best,” Brooks concurred and published them. But Cagle and Fairrington are not on the same wave length as Bennett or Brooks, so their judgement about what’s “best” in an editorial cartoon does not yield the same cartoons as Bennett and Brooks chose. The two books display other, more obvious, differences, too. Cagle’s book is bigger, 276 pages vs. Brooks’ 206. And Cagle includes more cartoons, maybe twice as many as Brooks. But Brooks gives his selection better display: typically, his book has no more than two cartoons to a page, although sometimes three. Cagle seldom gives a cartoon a half-page to itself; typically, he runs three cartoons to a page, sometimes four—even five. In short, artwork—the pictures—get better treatment in the Brooks book. But there are more cartoons in Cagle, albeit many on manifestly trifling matters. Brooks also includes lists of Pulitzer and Sigma Delta Chi winners through the years and gives last year’s winner special display at the front of the book. Cagle includes no such listings. But he does publish a few informative and/or entertaining short essays on political cartooning; Brooks does not. Other differences are less obvious and derive, as I said, from the ways the editors pick their book’s contents. The content of Cagle’s book is siphoned mostly (but not exclusively) from the stable of cartoonists whose work is regularly displayed at his MSNBC.com website, so some cartoonists are bound to be missing. Neither Ann Telnaes, for instance, nor Signe Wilkinson are represented at MSNBC.com, so they aren’t in the book. Cagle’s “best” cartoons are not culled from a complete line-up of the nation’s cartoonists. But neither are Brooks’ “best”: if a cartoonist doesn’t choose to submit five of his “best” cartoons to Brooks, he won’t be represented in the Brooks collection at all. And that, as it happens, brings us to the greatest flaw in the Brooks book. Over the years, Brooks has demonstrated a preference for a conservative point-of-view as well as a distinct aversion to the more extreme manifestations of a left-careening perspective. As his reputation in this bias grew, the number of cartoonists submitting work shrunk. If you’re a left-leaning tooner, why bother submitting when you know you have a strike against you from the start? Telnaes and Wilkinson are not represented in this volume either. Nor is Tony Auth, Bill Schorr, Steve Benson, or Ben Sargent. Surprisingly, however, Ted Rall is: this year (wonder of wonders), Brooks picked one of Rall’s five submissions. And the number of liberal perspectives in the 2008 Edition is much greater than it used to be several years ago. Moreover, some liberals are as well represented as conservatives. Any cartoonist with five cartoons in the book is as favored by Brooks as it is possible to be: Brooks has picked all five of the cartoonist’s submissions. And in this year’s collection, we have such liberals as Jeff Danziger, Etta Hulme, Mike Keefe, Mike Luckovich, Nick Anderson, and Mike Peters as well-represented as Michael Ramirez, Ed Gamble, Mike Lester, Dick Locher, and Bob Ariail, all reputed conservatives. Perhaps Brooks is as disillusioned with George W. (“Wiretapper”) Bush as any liberal and so includes cartoons with that disparaging slant as an enactment of his own disappointment in the Bush League. In the Cagle collection, the supposed liberal bias of one editor (Cagle) is offset by the presumed conservative bias of the other (Fairrington). Both books this year, for perhaps the first time, seem “complete” in the sense that both liberal and conservative points-of-view are well represented. Brooks’ volume favors cartoons on “important” issues; he includes only two on Senator Craig’s foot-tapping in a Minnesota men’s room while Cagle offers 39—thirty-nine!—in fourteen pages. Fourteen pages of men’s rooms!! Most of Cagle’s selection is produced by nationally known cartoonists of sophisticated competence. But Brooks includes the work of a lot of editoonists whose efforts are still distinctly amateurish. The Brooks pages offer a modest sampling of cartoons by some of the best in the profession, but far too many of those pages carry the work of cartoonists who are probably not full-time editoonists: they are doubtless staff artists at their newspapers and occasionally produce an editorial cartoon, and their lack of experience is evident in both the quality of the drawings and the deployment of images in anything like memorable visual rhetoric. The percentage of cartoons in this category has grown over the last few years, it seems to me—just as the number of cartoonists with national reputations has shrunk, as if the former were taking the place of the latter. While Brooks’ book includes a number of cartoons by the best in the business, the impression I have in reading it is that too many of the cartoonists represented therein are not yet ready for prime time. After several years of weighing the merits of these two congeries of cartoons and proclaiming them equivalent in quality if not equal in content, this year I have decided that Cagle’s is the better of the two. Brooks’ volume is the more “serious” of the two because it concentrates on important issues; but it elevates inferior work, too. Cagle’s book giggles with too many cartoons on insignificant matters, but the cartoonists in his book are all surpassingly professional practitioners of the craft. And amid the greater number of cartoons, we can find ample evidence of the “best” on even serious subjects. Here is a sampling of Brooks’ selections—a few of the better drawn cartoons on “important” subjects that deploy memorable and telling visual metaphors.