|

|||||||||||||||||

|

EDITOONERY An Gallery of Some of the Year’s Best Political Cartoons Preceded by a Diatribe about Other “Best Lists” and Time’s Lost Nose for News Including Major Events of the Year and Under-reported News from Project Censored

BOOK REVIEW The Best Editorial Cartoons of the Year: 2008 Edition from Cagle.com - What’s Wrong with It

NOUS R US Sales of Comics Continues to Increase Free Comic Book Day Date Peter Parker and Mary Jane Split Susie MacNelly Sues TMS Gus Arriola and Jean Gould O’Connell Honors

Lynn Johnston’s Double Parting Clay Bennett’s Priorities Manga in France & at Marvel 952 Caricatures in 24 Hours Michaelis’ Schulz and Peanuts New Yorker’s Cartoon-captioning Game Editor Jailed for Publishing Danish Dozen Man Fired for Posting Dilbert Strip

Playboy’s Wonder Woman Cover Irish McCalla Nude and Vintage Sheena Reprinted Writers’ Strike Effects on Comics

Marty Links Dies at 90

Birthdays in 2008 Bugs Bunny The Lone Ranger The Smurfs Oh—and Superman

THE TWO-STRIP RULE & What it Means for African-American Cartoonists & What’s Gonna Happen on February 10

COMIC STRIP WATCH Luann, Blondie, Zippy, Funky Winkerbean Pearls before Swine, Pickles, Peanuts, Zits Doonesbury, Non Sequitur

CHRISTMAS IN THE COMICS Do Newspaper Strips Celebrate It Anymore?

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE 100 Bullets, Savage Dragon, Bomber Queen, Tank Girl, Bat Lash BOOK MARQUEE Volume 3 of Mary Perkins On Stage Dondi Another Rejection Collection from The New Yorker Mr. Oblivious

And our usual reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this super-sized installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu— EDITOONERY Some of the Best of the Year: An Aesthetic Determination Janus, the Roman god with two faces—the better to look backward and forward at the same time—gave his name to the first month of our year with good reason: we usually spend at least a few hours on the first day of the first month looking back over the events of the previous twelve with mixed feelings—head-shaking astonishment that some of them could even have happened, wild-eyed alarm that we were preoccupied with so many of the more trivial of them, not to mention such other prevailing emotions as disgust, amusement, morbid curiosity, and towering rage. We also, if we are as thoughtful as we always claim to be, ponder the future for a few minutes, hoping for a safer world, better television programming, and unrelieved happiness. And here at the Rancid Raves Intergalactic Wurlitzer, we have in recent years devoted the first Opus of the New Year to viewing some of the best examples of the art and ardor of editorial cartooning in the U.S. Editorial cartooning inevitably involves current events: if daily journalism is, as it often claims, the first, albeit rough, draft of history, editooning is the first emotional outburst at the events that provoked the first draft—unthinking sometimes, from the deepest pit of the gut always, we fervently believe. Newsweek magazine has participated in this year-end game, too, and I’ve usually criticized its editors for their empty-headed choices: in the petty tradition of their weekly Perspectives page, they always pick cartoons that make them laugh rather than think, much to the consternation of the editorial cartooning fraternity whose work the magazine deems worthy of this dubious recognition. Editoonists would rather be feared as rebellious agents of political and social change than laughed at like late-night tv talk show hosts. But their preferences matter not a whit to Newsweek, which persists in ignoring them. Or flouting them, deliberately. This year, the latter, I think. For a few years, Newsweek’s year-end issue had a political cartoon on the cover, proclaiming the summary theme of the issue. Not this year. And this year, the number of cartoons seems smaller. Their size, all about 3x3 inches, is undeniably smaller. And so is the sample: Mike Luckovich has 9 of the 12 cartoons in this issue. Luckovich is a Pulitzer- and Reuben-winning editoonist whose cartoons are often hard-hitting and unflinching, but he also likes to vary his pitches (as he puts it), throwing the occasional soft-ball Leno joke. (Most editoonists do this, knowing that humor is the hook: people enjoy laughing, and so if a cartoonist provokes a laugh every so often, he can be reasonably sure newspaper readers will read him regularly, and he can then urge his serious world-changing agenda upon them.) Since Luckovich is good at his craft, even his laugh-provoking cartoons are worthy of a second look, a circumstance profusely exemplified in this year’s Newsweek round-up. The topics are mostly trivial enough to warrant laughter: Senator Craig’s gaeity, GeeDubya’s begrudging awareness of global warming, Libby being sacrificed, Oprah campaigning for Obama, Hillary planting questions in her audiences, Thompson’s moribund campaigning style, Romney’s flip-flopping, Gore winning an Oscar, airport delays, Vick’s killing dogs, and, finally, a couple major topics although treated jocularly, the housing market and George W. (“Warlord”) Bush’s passion for invading Iran. Except for the last two, none of these “issues” rates an attack-dog cartoon, so jokes are appropriate. But in a news magazine summarizing the year’s events? This year, Time magazine, having sat on the sidelines for years, watching Newsweek get all the laughs, joined the year-end frolic, offering its pick of the year’s editoons in one of its several online “top ten” features. This selection, which can be viewed at http://www.time.com/time/specials/2007/top10/article/0,30583,1686204_1690170_1690363,00.html, is even more disastrously trivial and inconsequential than Newsweek’s crop. The cartoonists—R.J. Matson, Daryl Cagle, and Mike Peters (with two each), plus John Sherffius, Bob Englehart, Gary Clement (Canadian), and Mike Thompson—all do superior work—not a slouch among them—but Time has selected from their year’s endeavors cartoons that focus on topics that are of very little consequence. Englehart’s cartoon, for example, is about senior sex: in the first of two panels, a reporter asks an elderly couple what they think of a survey that shows senior citizens are having sex two or three times a month; in the second panel, the old guy says, “That’s all?” This is one of the Top Ten editoons of the year? Anyone even vaguely aware of the mechanisms of comedy realizes this “joke” employs one of the oldest dodges in the business; its very antiquity ought to disqualify it as a candidate for the Top Ten Editorial Cartoons. But Time’s editors are clearly clueless about comedy. The other nine topics: candidate Fred Thompson’s inability to make a good stump speech attributed to the writers’ strike, toxic toys from China, Senator Craig’s gaiety, Barry Bond’s asterisked homerun record, Iran’s Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s visit to the U.S., Obama and Cheney related, Jerry Falwell encountering evidence of gay life in heaven, and the Virginia Tech slayings. Only the last is a very serious matter. We may conclude from this that in Time’s view, cartoons deal only with insignificant albeit funny issues and cannot, therefore, be serious journalism. But then, I don’t take Time seriously anymore either. And with good reason. Aside: I’m about to launch into a lengthy diatribe about Time’s shortcomings as a newsmagazine, with a few even more discursive detours, most of which have only a tangential relationship to cartooning. If you want to skip all the fussing and fulminating, simply scroll down a few acres until you come upon a boldfaced heading announcing Some of the Best Political Cartoons of 2007; we’ll resume our customary cartoonery commentary there. Now, let me plunge into that diatribe: At the aforementioned website, Time lists the Top Ten Under-reported Newsstories of the year, betraying a news judgement that has gone grievously kilterless: the refugee problem a-borning in Somali, six nukes inadvertently loaded onto a B-52 and flown across the U.S., the U.N.’s overestimation of the number of AIDS cases worldwide, federal agency employees illegally campaigning for Republican candidates over the past six years, drug resistant tuberculosis, the oil-nourished economic boom in Angola, obesity rate leveling off among U.S. adults, new oil fields discovered in Brazil (making it more oil rich than Saudi Arabia), earmarking legislation in Congress that continues apace despite Democrat avowals to change politics as usual, and Ethiopia and Eritrea veering towards war in East Africa. I’m not disputing altogether the seriousness of some of the issues in Time’s Top Ten list, but their magnitude, it seems to me, is dwarfed when they are compared to the first ten stories in Project Censored’s list of the Top Twenty-five Censored Stories of 2007 (published in the Project’s annual tome, Censored 2008). “Censored” is perhaps too strong a term. The stories picked by the Project are generally those that are not widely covered or deeply delved into because, as we know, corporate news media devote most of their reporting resources to stories that will increase ratings or circulation. Peter Phillips, director of Project Censored, makes the case for “censored.” In the winter issue of the Project’s newsletter, he writes: “The corporate media in the U.S. like to think of themselves as the official most accurate news reporting of the day. The New York Times motto of ‘All the News That’s Fit to Print’ is a clear example of this perspective. However with corporate media coverage that increasingly focuses on a narrow range of celebrity updates, news from ‘official’ government sources, and sensationalized crimes and disasters, the self-justification of being the most ‘fit’ is no longer valid in the U.S. ... When a media fails to cover issues [that are important to the public weal], what else can we call it but censorship?” If not “censorship,” then at least “under-reported” and legitimately comparable to stories on Time’s list. Here are the first ten of Project Censored’s current list: 1) No Habeas Corpus for “Any Person,” 2) Bush Moves Toward Martial Law, 3) U.S. Military Control of Africa’s Resources, 4) Increasingly Destructive Trade Agreements, 5) Human Traffic [i.e., Slaves] Build U.S. Embassy in Iraq, 6) Operation FALCON (Federal and Local Cops Organized Nationally) Coordinates Mass Arrests of 30,000 “Fugitives” in the U.S., 7) Behind Blackwater Inc., 8) The U.S. Invasion of India, 9) Privatization of America’s Infrastructure, and 10) Vulture Funds Threaten Poor Nation’s Debt Relief. Each of these and the rest of the Top Twenty-five are discussed in detail in the book and at projectcensored.org. But even without elaboration, most of the topics I’ve listed by their cryptic headlines seem more significant than the leveling off of the obesity rate among U.S. adults or the nukes that were inadvertently loaded onto a B-52 and flown—harmlessly, I should add—all across the country. These two stories fall into the typical categories of fevered interest among ravenous tabloid readers: the first, “news you can use” (the pressure’s off: you can now eat all you want again); the second, “be afraid, be very afraid—one of these babies could have fallen on you.” In 2000, Brooke Shelby Biggs pooh-poohed Project Censored in Mother Jones (http://www.motherjones.com/commentary/columns/2000/04/projectcensored.html), saying, among other things, that to call the stories “censored” is misleading (Phillips seems to address this concern) and that “Project Censored has become a thinly veiled excuse for an alternative press self-love fest.” And maybe she was right in 2000. But glancing over the exegeses of this year’s tally isn’t a comforting experience. As Phillips says, “The common theme of [these] stories over the past year is the systemic erosion of human rights and civil liberties in both the U.S. and the world at large” by the creation of a federal authority with powers sufficiently immune from democratic redress as to establish a virtual dictatorship. The first story in the list asserts that news media failed to take sufficient note of the provisions of the Military Commissions Act that GeeDubya signed in October 2006 which allow the suspension of habeas corpus for “any person” regardless of American citizenship. While the New York Times and others gave “false comfort that America citizens will not be the victims of measures legalized by the MCA, the law is quite clear that ‘any person’ can be targeted.” Thus, “the MCA effectively does away with habeas corpus rights for all people living in the U.S. deemed by the President to be enemy combatants.” And remember the money appropriated a few years ago to rehabilitate moth-balled military bases around the country? Looks suspiciously like someone is preparing detention camps for large numbers of “enemy combatants.” No? Then consider the John Warner Defense Act of 2007 which “allows the President to station military troops anywhere in the United States and take control of state-based National Guard units without the consent of the governor or local authorities in order to ‘suppress public disorder.’” This gives GeeDubya (or whichever Democrat replaces him next year) the muscle to enforce Presidential will. And then legislation with the seemingly harmless title The Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act (AETA) of 2006 expands the term “terrorism” to include “any acts that interfere or promote interference with the operations of animal enterprises,” which, by another expansion of definition, includes “any business that uses or sells animals or animal products.” The latter would include, for instance, grocery stores that sell beef. But “animal products” is a vast category these days, including, for example, fat, gristle, hair, bone—not to mention wool and all crops upon which “animal products” (i.e., manure) may be used—some of which finds its way into things we buy that we don’t normally think of as being derived from animals. Under this law, no one can interfere with any business where animal products might be involved. Thus, “the law essentially defines protesters, boycotters or picketers of businesses in the U.S. as terrorists.” Would a President actually use such laws to detain American citizens? In the person of George W. (“Warlord”) Bush, he already has. The sixth story in the list reports on three federally coordinated mass arrests between April 2005 and October 2006 in which more than 30,000 persons were arrested and jailed, “the largest dragnet in the nation’s history. The operations, coordinated by the Justice Department and Homeland Security, directly involved over 960 agencies (state, local, and federal) ... the first time in U.S. history that all of the domestic police agencies have been put under direct control of the federal government.” I’m being alarmist in the extreme, I suppose. But if we consider how the Bush League lawyers de-code the fine print in legislation, reading into laws intentions that no one else thought were there, my alarm may not be too wildly off the wall. Assuming, then, that I’ve put you in the proper mood, consider the Violent Radicalization and Homegrown Terrorism Prevention Act passed by the House last October. Its purpose is to study various social phenomena, chiefly those involving people with radical beliefs who might turn into people who would resort to violence, and then to propose legislation that would address and eliminate this threat before radicalized individuals turn violent. “This preemptive measure of policing thought specifically identifies the Internet as a tool of radicalization,” according to the Project Censored newsletter. Authors of the law claim that “the Internet has aided in facilitating violent radicalization, ideologically based violence, and the homegrown terrorism process in the United States by providing access to broad and constant streams of terrorist-related propaganda to U.S. citizens.” Over the years, various embryonic efforts to tax or license use of the Internet have been floated; none have yet found their way into law. “Freedom of expression” has, so far, preserved unfettered use of the Internet. But how long can that last once Homeland Security has decided that one of the best ways to protect us from “homegrown terrorists” is to charge a whopping fee for use of the Internet? That will deny radicals, who, as we all know, are usually impoverished, access to the ‘Net. Fear, one more time, will trump freedom. Well, yes—I’ve wandered far afield from simply criticizing Time’s news judgement as a way of ridiculing its choices of the “top ten” political cartoons of 2007. And I’ll eventually return to the subject with my own choices of some of the best political cartoons of the year. But before I get to that, I’ve not quite finished my ranting about Time. If evidence of Time’s news sense being drastically impaired is not sufficiently unveiled in the foregoing paragraphs, we have the magazine’s annual Person of the Year selection to cinch the case against it. Vladimir Putin. C’mon. The criteria for selecting the Person of the Year, according to Time’s website, implies that the magazine’s editors will pick the “man, woman or idea that ‘for better or worse, has most influenced events in the preceding year.’” And what signal events, exactly, did Putin influence in 2007? The events that dominated the news over the last twelve months seem to me to be these: The Surge and Iraq. Undertaken in blithe defiance of a bi-partisan report calling for actions almost exactly the opposite of this military adventure, the Surge is dramatic evidence of George W. (“Warlord”) Bush’s blinding stubbornness and of his willful disregard of all advice contrary to his “gut” feelings in the pursuit of this and all other objectives of his so-called “administration.” (GeeDubya thinks his stubbornness is heroic “resolve” and his disregard of all advice is evidence of divine inspiration.) Although the Surge may have quelled, temporarily, the violence in Iraq, the real purpose of the exercise, to permit the ruling Iraqis to achieve political stability, has fallen far short: of the 18 political benchmarks set by the U.S., Iraqis have met only 3. The Walter Reed Army Medical Center scandal, the year’s most shameful event, is but part of the whole Iraqi-Global-War-on-Terror scam; as is Afghanistan and the deteriorating situation there. And when the Blackwater private army so abused its power and privilege as to give American forces another black eye in Iraq—just what we need: a gross caricature (albeit realistic) of American military arrogance and insensitivity to the local population—it demonstrated yet again the folly of privatizing the nation’s official endeavors. Meanwhile, the U.S. continues to defend torture as a viable “interrogation technique,” thereby earning the scorn of civilized peoples everywhere, and, another disgrace, thousands go on dying in Darfur while the U.S. and the rest of the world look on in seeming helplessness, their forces and political will preoccupied in Iraq. Iran and the Bomb. The country’s inexplicable loss of nuclear capacity and its president’s shenanigans on the world stage constitute a capsule representation of the phoniness of George WMD Bush’s justification for invading the country. Economy. Home mortgage defaults due to subprime loans threaten the nation’s economy. Islamic Hooliganism. Violent protesting multitudes in the streets and suicide bombers by the score, not only in Iraq, but in Palestine, Israel, and other countries—Afghanistan, etc.—dramatize the War of the 21st Century: a war waged by the pure-in-heart have-nots against the infidel haves. Early Presidential Campaigning. The year’s non-story story. None of the so-called candidates is yet the nominee of any political party, and while the aspirants are clearly “out there” campaigning for the nomination, it’s the would-be news media that have inflated a contest for the votes of a few farmers in Iowa into an event of national significance—a contest that only pundits and intellectually impoverished newsmen could turn into a year-long expedition worthy of national news coverage. And Illegal Immigration has become the phoney issue of the phoney story for much the same reason. Groveling for votes seems to justify taking every miserable political position possible on every issue. Global Warming. At last, the Bush League seems poised to accept the idea; meanwhile, Gore gets an Oscar and the Nobel Prize. But Global Warming, like Illegal Immigration, is little more than a political diversion intended to keep the ravening press and the fickle American voter amused and distracted enough that no one will notice genuinely important matters of the public weal that, unlike Global Cooling, are capable of achievement but are willfully ignored—like the condition of the nation’s infrastructure, for instance, which could be fixed but is being deliberately side-lined. It would cost money; raising taxes would be necessary. It costs nothing to blather on about Global Warming and Illegal Immigration. Justice Perverted. U.S. Attorneys are fired for failure to adhere closely enough to the Bush League agenda; Attorney General Gonzales resigns in disgrace. And Lewis “Scooter” Libby, the Vice President’s chief minion, is convicted in the CIA leak case and then effectively pardoned by GeeDubya, all of which proves, if it needs proving, that Darth Cheney’s role in the Bush League government is more extensive than anyone could imagine. Democrats Flame Out. Nancy Pelosi becomes the first female Speaker of the House as the Democrats achieve a majority in Congress, but, apart from hooting and bloviating about the sins of the Republicans, do little more than display an unwillingness or inability to effect any change in politics as usual. As a culture, we were also afflicted with the usual Tabloid Tsunami involving such significant personages as Anna Nicole Smith, Britney Spears, Paris Hilton, Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie, Jennifer Aniston, Barry Bonds, and Paul Wolfowitz, who, after being forced to resign from the World Bank, re-joined the Bush League as an advisor in the State Department. (Wait—what happened the last time the government took his advice?) Where, in any of this news, is Valdimir Putin? Nowhere. In selecting him as Person of the Year, Time persists in abdicating its journalistic responsibility in favor of selling magazines by pandering to what it imagines as the interests of the reading public. It did the same thing last year when it put a mirror on the cover of its Person of the Year issue and tried to persuade us that “we”—all of us, you and me and your mother-in-law—had done more to influence the events of the year than anyone else. (Well, sure; but what’s “news” about that?) In the last decade, Time has repeatedly copped out, choosing “groups” or “symbols”—Washington Whistleblowers, the American Soldier and then Bill and Melinda Gates and Bono—instead of doing the obvious, naming GeeDubya the Person of the Year. He and the neoconservatives he fronts for have clearly, “for better or worse,” done more to “influence the events” of recent years than anyone else. The fiasco they’ve wrought in Iraq has dominated the news of the world for six years, yet GeeDubya has been Person of the Year just twice during that period, getting on the cover of Time only when he gets “elected” to the Presidency, in 2000 and in 2004. Time, which inaugurated its “Man of the Year” cover story in 1927 in order to generate enough content to fill the magazine’s issue published the week between Christmas and New Year’s—a traditionally slow news period—has, since naming Charles Lindbergh the first of its holiday cover features, become so impressed with the intergalactic potency of its annual designation that it jealously protects its seeming dignity by denying the presumed “honor” to the obvious choice, that remarkably undignified international buffoon, George W. (“Whopper”) Bush. There can be no other explanation for ignoring him. Putin, who is undoubtedly a powerful Russian and who is making headlines by arranging to remain in power after the constitutionally imposed term limit expires in the spring, scarcely influenced much news in this country in 2007. Time’s editors probably settled in Putin because that would give them the opportunity to coin the headline they used in their cover story: A Tsar Is Born. In opting for a colossal pun, Time overlooked several cover story possibilities suggested by the major newsstories of the year, each of which, in the magazine’s usual practice, could serve as entre to examination of larger associated issues. The Surge in Iraq would have justified picking GeeDubya again (or, failing that, General David Petraeus) and would have permitted examination of a number of Iraq-related issues—the effectiveness of the Surge itself, the failure of the Democrats to stop the War, the Walter Reed scandal, privatizing the military, torture, Darfur, and, even, the error of accusing Iran of making the Bomb. (GeeDubya had the gargantuan gall to assert—in public where everyone could hear him—that the Intelligence report that revealed this claim to be an illusion wouldn’t change his mind on the subject, thereby demonstrating what we’ve all suspected for a long time: his mind is made up, and he won’t be confused by facts.) Other possibilities include the Iowa Farmer, represented, perhaps, by Grant Wood’s famed 1930 “American Gothic” portrait, as a way of exploring the folly of starting a Presidential campaign two years before Election Day. Quite apart from the irrationality of letting just the politically active minority in a small, demographically unrepresentative state determine the candidates of major political parties, there’s other damage being done by the Iowa extravaganza: for instance, because Iowa farmers raise corn by the acre, ethanol is discussed by vote-grubbing candidates as a viable alternative to fossil fuel when, in fact, it isn’t. Another aspect of the subject is the way primaries are arrayed across the country and the calendar. Rotating regional primaries would make more sense, be more democratic, and eliminate the dominance of such tiny populations as those of Iowa and New Hampshire. But GeeDubya and Petraeus are clearly the “persons of the year” by Time’s historic formulation. If not one of them, then Karl Rove, whose departure from the national stage might signal the end the Bush League’s kind of government by party politics, seeking always the political advantage rather than the public good, and would permit a discussion of Rove’s influence and, thereby, the idiotic policies of the neoconservative right, of which, we assume from the heavy turn-out of Democrats for the Iowa caucuses, we are, as a nation, thoroughly weary. And this might lead to an investigation of the uncommon and undemocratic (because secretive) influence of Darth Cheney, who, while proclaiming his detachment from Halliburton all the time, has realized an income of $200,000 per year from his former employer while serving as Vice President. Just how disinterested is he in Halliburton? His stock in the company, which, without having to bid competitively, has secured contracts in Iraq worth billions, has risen over 300 percent in 2006 alone. But Time has given up on such matters. As additional evidence of the magazine’s allegiance to the MTV culture of tabloid journalism rather than the somewhat more serious business of reporting governmental activities that voters should be aware of, we have the editors’ second runner-up for the Person of the Year designation—J.K. Rowling. As a former highschool teacher of English, I’m delighted that the Youth of the World, particularly in this country, have found the joys of print entertainment again. In this age of video games and the seductions of the Web, Rowling’s achievement is nearly miraculous. Profound as the influence of Harry Potter may be on the literacy of the world, he and his creator did not influence events much beyond the selling of the seventh, and last, book in the series. Time’s other runners-up, Al Gore and China’s Hu Jintao and, yes, David Petraeus, were better than Rowling and better than their final choice. But, as I’ve said, Time has effectively proclaimed its abandonment of journalistic responsibility in making such misbegotten choices as Putin or Rowling or, to lurch back to the subject that started me on this diatribe, the Top Ten political cartoons of the year.

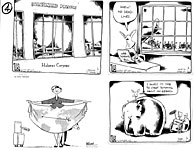

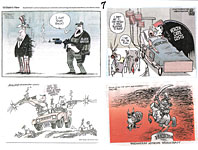

SOME OF THE BEST POLITICAL CARTOONS OF 2007 My selection of the best editoons is grounded on the nature and function of the medium. The “best” political cartoons are those in which words and pictures blend to achieve a purpose neither words nor pictures alone without the other is capable of. That purpose for a political cartoonist may be characterized as creating an image so potent and so memorable as to influence the way people think about an issue—and, subsequently, vote about it. Advocacy journalism of the most virulent sort, deploying ridicule and scorn and, yes, laughter, the cleansing balm of the riled soul. Herein, however, I am not going to limit my choices of the “best” editoons of the year to a mere ten; nor do I think my choices are all the best there is. I don’t, in the normal course of my perambulations through the public prints, see all the work of all the good editoonists in the country. My selection may even include cartoons that are not the best efforts of the cartoonist represented. So the headline above is apt: here are “some” of the best political cartoons of the year. The cartoonists on display are (more-or-less in order): John Branch, San Antonio Express; Pat Oliphant, Universal Press Syndicate; Kevin “Kal” Kallaugher, The Economist and Cartoonists and Writers Syndicate/New York Times Syndicate (CWS/NYTS); Mike Luckovich, Atlanta Journal Constitution; Ed Stein, Rocky Mountain News; Ted Rall, Universal Press Synd.; Tom Tomorrow, ThisModernWorld.com; Siergey (sorry, I failed to pick up the whole name or syndicate, if any); Tom Toles, Washington Post; Ann Telnaes, CWS/NYTS; Steve Sack, Minneapolis Star Tribune; Jeff Danziger, CWS/NYTS; Clay Bennett, Christian Science Monitor; Daryl Cagle, MSNBC.com; Mike Lester, Rome News Tribune (Georgia); Jeff Parker, Florida Today; Mike Keefe, Denver Post; Etta Hulme, Ft. Worth Star Telegram; Thomas Boldt (TAB), CagleCartoons.com; Tony Auth, Philadelphia Inquirer; Walt Handelsman, Newsday; Bill Schorr, New York Daily News; Steve Kelley, Times-Picayune (New Orleans); Joe Heller, Green Bay Press-Gazette; Robert J. Matson, St. Louis Post-Dispatch; Michael Ramirez, Investors Business Daily; Chip Bok, Akron Beacon Journal; Dave Horsey, Seattle Post-Intelligencer; and Pat Bagley, Salt Lake Tribune.

Most of them, as sterling examples of the yoking of the verbal and the visual to create telling and often memorable images, need no further explanation. But I can’t resist commenting on a few, some of which enthusiasm appears on sundry of the twelve pages in this vicinity. But some of those pages don’t have room enough for my verbal excesses, so I’m ladling it out here, by page number; the page numbers appear along the tops of each page. On Page 4, we have three of Tom Toles’ superior blendings of words and pictures; all three create memorable messages which, absent pictures, are impossible of achieving as economically otherwise. Ann Telnaes’ visual comment is similarly superb: GeeDubya, who has lied and dissembled so often that he is no longer believable even when commiserating about human tragedy, has started sending his wife out to voice American concern about the brutal crackdown in Burma, for instance, and elsewhere. Telnaes’ caricatures are always dead-on, too. On Page 9, we have one of the most unusual deployments of a political cartoon at the upper left. The Denver Post has lately taken to re-printing “archival” cartoons by Mike Keefe. This one from 1995, a powerful image in itself, gains more power as we realize it’s still pertinent after more than a dozen years: it demonstrates as nothing but a vintage image can how shamefully Congress has been dilly-dallying instead of fixing a system that is increasingly reliant upon syphoning off the financial resources of the younger generation. Steve Kelley’s cartoon (lower right) needs the pictures only to identify the speakers and their presumed attitudes; the power of Kelley’s message resides mostly in the agility of the verbal content. At the upper left of Page 11, Michael Ramirez’s message can be conveyed in no other way than this clever diagrammatic melding of words and pictures. Chip Bok’s image at the upper right is an inspired way of pointing out that Fred Thompson, coming into the campaign so late, made an ass out of himself. The juxtaposition of images in Pat Bagley’s cartoon at the lower right is a telling comparison of John F. Kennedy and Mitt Romney on the issue of religion in government: Kennedy, all sober oratory; Romney, a drive-in pandering to fast-food lovers with what we might term “McPolitics”—give ’em what they want. The next page, our 12th, is all Bagley. As I’ve mentioned before recently, Bagley has for years been flying below the national radar in political cartooning because he hasn’t been syndicated. When Cagle Cartoons started distributing Bagley’s work, he was suddenly visible in several venues—national news magazines and other newspapers. His work is powerful, his command of the medium masterful, delivering telling image after telling image. Although I think the quality of his work warrants the kind of attention it’s getting here with a whole page devoted to his cartoons, the page is also justified by reason of his recent emergence on the national editooning horizon. And that’s some of the best of the year.

BOOK REVIEW Before we drift too far out to sea and away from landlubber editorial cartooning, here’s another annual round-up, from Daryl Cagle’s political cartoon website, cagle.com, edited by Cagle, a “liberal” (more-or-less) and Brian Fairrington (a so-called conservative), The Best Political Cartoons of the Year: 2008 Edition (288 8x10-inch pages in black-and-white; paperback, $16.99), a misnomer of a title since its contents are culled from 2007's cartoonery, not 2008's. But you knew that. I’m not going to take up much of your time with this review: I’ve reported on this book every year for as many years as it’s been published, and my observations remain substantially the same. Lots of cartoons (over 800 of them) by lots of cartoonists (162) makes this volume worth putting on the shelf for purely historical reasons. The flaws in the collection include: too many cartoons printed too small, too much emphasis on trivial matters, and too many cartoons by one of the editors, Cagle, with 31 (his nearest competitor, Mike Lester, has only 19; and after that the numbers hover around a dozen for the most represented cartooners), and the overweening presence of cartoonists in Cagle’s syndicate, Cagle Cartoons, which leads one to suppose that the book is as much a promotional brochure as it is a serious compendium of the year’s events as seen by cartoonists. But there are many many other cartoonists, non-Caglers, in the book, so it’s not quite fair to say it’s merely an excuse to promote the cartoonists syndicated by Cagle Cartoons. As for Cagle focusing so rambunctiously on himself, he reported last November that he was surprised by a pile of statistics he’s been assembling to discern which of the cartoonists on his site is the most popular. And he actually blushed (he sez) to announce that he, Daryl Cagle, was at the top of the list. The rest of the top ten, in rank order, were: Pat Bagley, Eric Allie, Monte Wolverton, Matt Bors, Andy Singer, Brian Fairrington, Shannon Wheeler, Clay Bennett, and Jen Sorensen. If some of these names are not much bruted about in your household, it’s probably because several of them appear only in alternative papers or only on Cagle’s site. Cagle found other matters of interest in the list: looking at the cartoonists ranked second, third and fourth, he notes that Bagley and Wolverton are “Bush bashers who are strongly against the war in Iraq” while Allie “is a loyal Bushie and supporter of the war in Iraq.” The list includes 5 liberal alternative cartooners, an arch conservative, and “two non-alties on the left,” Cagle says. “The only trend I see,” he concludes, “is that these artists are mostly liberal, with very strong individual styles and points of view. I shouldn’t be surprised that they have loyal fans.” Ditto Cagle himself: he is good at what he does. By way of ascertaining the persistent triviality of the publication’s content, you may arrive at a snap judgement by comparing the number of pages devoted to the Don Imus brouhaha with the number commenting on the housing market crash: 14 vs. 12. Are these two occurrences actually of equal importance? The “Crazy Diaper Astronaut” who drove from Houston, Texas, to Orlando, Florida, to attack her astronaut boyfriend’s new girlfriend—wearing a diaper so she wouldn’t have to stop en route and loose any time peeing—also got 12 pages. Other sections ridicule “Kramer’s” racism, “bewildering Britney,” Harry Potter, Vick’s dog fighting career, Paris in prison, Senator Craig in the toilet (12 pages) and Anna Nicole Smith. There are only four pages each on the resignations of Rove, Gonzales, and Rumsfeld; ditto on the scandal at Walter Reed Medical Center and the collapse of the bridge in Minnesota. Saddam’s death by hanging rates 12 pages, the whole Iraq disaster only 30, shabby treatment by comparison. Take another look at my list of major events of the year again; you won’t see many of them taking a lot of pages in this collection. My criticism is that if this book is a showcase for political cartooning, it spotlights mostly whatever events can be easily turned into comedy. One could conclude, then, that editoonists are out only for laughs and have no serious journalistic or societal intentions at all. That too many readers of newspapers see political cartoonists in precisely this way is a complaint among most of the fraternity. This book perpetuates and fosters the misbegotten view that cartoonists are mere pen-wielding pranksters. This year, Cagle explains more carefully than in previous years why “we have so many cartoons about the lovesick-diaper-astronaut compared to Iraq.” It’s “because that’s what cartoonists really drew this year.” Unlike the only other annual compilation of this genre of cartooning, Pelican’s The Best Political Cartoons of the Year, edited, usually, by Charles Brooks, Cagle and Fairrington don’t ask the cartoonists to submit the cartoons that the cartoonists think are their best. The cartoonists, if left to their own devices, would pick only what they regard as their most “important” cartoons, so Cagle and Fairrington would get “lots of cartoons about Iraq, President Bush, and civil rights, and not the cartoons drawn about celebrities and popular culture”—not the cartoons that were ridiculing inconsequential events of the year. But Cagle and Fairrington do the selecting for this volume, and they choose from what the “cartoonists really drew in 2007, in the correct proportions.” Cagle claims the book is a history book. True: it’s the history of political cartooning in a given year—not the history of societies or nations or governments or global warming or of events that changed the course of human affairs. And if we take this book as an indication of the role of political cartooning in 2007, we must say that editoonists mostly aspire to be Jay Leno. Despite what they say in moments of high journalistic ambition, they’re aiming for laughs, not political clout. They’re cartoonists, after all, not historians or philosophers or political scientists. And so we get 20 pages about the hilarious antics of presidential candidates during a year that they should have been attending to government instead of cultivating Iowa farmers. The gamboling of politicians makes for some good jokes, no question. And maybe, now that I ponder it, that’s the serious thinking we’re supposed to do: maybe Cagle and company intend that we think of candidates for our nation’s highest political office as comedians. I confess, I often do just that. Not that all the cartoons in this book are on trivial subjects, drawn with the sole object of inciting laughter. Some are hard-charging, thought-fomenting cartoons. And I could easily have picked a couple dozen to include among my own harvest of “some of the best of the year.” But most, by far, just make us giggle, not think. Many, however, show impressive skill in deploying words and images for effect. Talent, in the editooning brotherhood, is not wanting.

NOUS R US All the News That Gives Us Fits The “No. 1" comics-related newsstory of 2007 was, according to Captain Comics (aka Andrew A. Smith at captaincomics.us), the continued growth in sales, which, as of the end of November, was estimated at $394.02 million, “closing in on last year’s $395.55 million.” Over-all at Diamond [Comics Distributors Inc], “sales have climbed every year since 2000, when they were in the $255-275 million range.” The Captain’s other “Top 5 Comics Stories of 2007" include: comics invasion of the Web, burgeoning reprint books of comic book features, “Spider-Man 3" being the No. 1 box-office movie of the year with $336,530,303 in ticket sales, and a cluster of “content” improvements—Marvel’s “Civil War” series, concluding with the death of Captain America and inspiring at rival DC another long series, “52"; Marvel’s comic book version of Stephen King’s Dark Tower novels; and the realistic-look make-over at Betty and Veronica. Last spring’s four issues of the Betty and Veronica Digest in which their new look debuted will be published as a graphic novel, just to prolong Archie’s studied attempt to crash the new market that the manga invasion fostered. ... Free Comic Book Day in 2008 will be Saturday, May 3, just on the cusp of the annual Cartoon Appreciation Week sponsored by the National Cartoonists Society. Peter Parker and his wife of twenty years, Mary Jane, have dissolved their marriage because of irreconcilable differences. My guess is that the colossal Spider-Man movies represent the irreconcilable part: Peter Parker isn’t married in the movies, but he is in the comic books and newspaper strip. So how do Mom and Dad explain this difficulty to their 8-year old children, masquerading as teenagers and college students when they buy the comics? To preserve the assumed integrity of the Spidey movie universe, it was necessary to eliminate this conspicuous difference. The Marvel moguls, however, will sing a different song. Said editor-in-chief Joe Quesada: “A single Spidey is truer to the spirit of the character.” Probably—if you retain in your memory his angst-ridden adolescence, the basis for the character’s uniqueness when he was first formulated by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko. “There’s a certain amount of stability that comes with being married,” Quesada told Dareh Gregorian at the New York Post. “Once he does become stable [i.e., married], you take away some of the drama that was a crucial part of his life.” I agree. But Quesada didn’t want to divorce the couple or make the web-slinger a widower because, Gregorian wrote, “that would make one of their company’s biggest icons seem too old.” The solution, I must say, is ingenuity at its apogee. Peter’s ailing Aunt May is near death, and the faustian Mephisto comes along and promises to restore her to health if Peter agrees to let him wipe out all memory of his being married to Mary Jane. She, presumably, is also brain washed of all such recollections. So is just about everyone else. No one, now, “including his beloved aunt, remembers that Peter Parker is Spider-Man” despite his having revealed his secret identity to the world during the notorious Civil War series last year. Mary Jane and Peter remember having dated and having been engaged, but they’re presently “on the outs.” We’re back at Square Two. Aaron McGruder is taking another step towards realizing his lifelong dream of becoming a Hollywood power: he’s “made a deal to develop a live-action series for the online hub Super Deluxe” (Editor & Publisher). “McGruder, whose high-profile comic strip was distributed by Universal Press syndicate 1999-2006, said he’s looking forward to doing topical commentary without the long lag of animation,” which is his current Boondocks gig in the Adult Swim on the Cartoon Network. ... The Olympian, “serving South Puget Sound” in Washington, joins the list of papers that are considering dropping B.C. and The Wizard of Id “because creator Johnny Hart died.”... Meanwhile, Susie MacNelly, widow of Shoe comic strip creator Jeff MacNelly, filed a lawsuit in November against the Tribune Media Services, charging that TMS is obstructing her plan to move the strip to King Features. TMS maintains that their contract, which expires on March 31, contains a first-refusal rights clause that enables it to extend the contract provided, as Alan Gardner points out at dailycartoonist.com, it matches any offer from another syndicate. “TMS has met King Features’ offer of $350,000,” Gardner writes, “and thereby feels it has fulfilled its contract and can extend” the original agreement with MacNelly. MacNelly, however, thinks beyond the purely monetary to ancillary possibilities, such as sales and licensing “that TMS is not providing or is incapable of providing,” and upon that basis is bringing suit. ... Gus Arriola, whose Gordo comic strip was the longest running (1941-1985) comic strip with a Mexican milieu and one of the most artistically rendered strips of all time, was honored January 19 with a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Arts Council of Monterey County in California, where Gus lives with his wife Frances. There’s a great photo of Gus at http://championsofthearts.org/Arts2008.html ; and more, taken from my stash (accumulated for the biography I wrote about him) at http://championsofthearts.org/GusPhotos.html. And there’s more about Gus in the book itself, which is described here. ... From Jeffrey M. Kersten, secretary of the Chester Gould-Dick Tracy Museum in Woodstock, Illinois: Jean Gould O’Connell’s biography of her cartoonist father has been nominated by the Mystery Writer’s of America for its 2008 Edgar Award in the category of Best Critical/Biographical Work. O’Connell is the principal founder of the Museum, housed in the Old Courthouse on Woodstock Square, said Kersten, adding: “The pride we feel here at the Museum is enormous.” Her book, which we described here in Opus 216, can be ordered through the Read Between the Lynes Bookstore in Woodstock by phoning 815/206-5967. ***** It was rumored, for a while (started by Karen Lindell at venturacountystar.com), that Lynn Johnston would actually retire from working on her celebrated comic strip, For Better or For Worse, next September. At present, the strip mixes reruns of older sequences of daily gags with installments carrying a current, 2007-2008 storyline. The rumor was that in September, the current, or “new,” material would cease and FBOFW would consist entirely of vintage material from its early years. The McGuffin was that Michael, the oldest of the Patterson offspring, married and with children of his own, would reminisce about his childhood, thereby “explaining” the older material. That’s still the plan, but Johnston won’t be giving up work on the strip altogether as it was rumored, briefly, that she would. Instead, she’ll be reworking some of the art in the older strips before they’re rerun (dailycartoonist.com). This will eliminate some of the difficulty she and her syndicate, not to mention editors of the newspapers running the strip, were having: people complained that the vintage strips looked as if they’d been drawn by some hack. Johnston’s style evolved over the years, and her current 2008 style looks much different from her older, “looser” style. That difference will, presumably, be eliminated or subdued under the new plan. Henceforth, beginning next September, all the strips published will be in the “looser” style. By then, she intends to wind up all the present yarns in the strip, gathering up the loose ends into a tidy ball. April and Anthony will somehow arrive at a future together—or not; and the stroke-ridden grandfather, Jim, will probably die. Even spending some time re-touching old artwork for the vintage reruns, Johnston will have more time on her hands than she has presently. She says she’s contacted single ladies she’s been friends with for years, and they’re planning travel and other divertissements. Unlike Ellie and John Patterson, the comic strip couple, Lynn and Rod, the cartoonist’s husband of 31 years, separated last April and intend to divorce. “He met someone else,” she told Pam Becker at the Chicago Tribune. “Well—it’s a surprise.” After a bit, she added: “Rod and I had some wonderful adventures together. If it hadn’t been for him, I wouldn’t have gone up to northern Manitoba, I wouldn’t have learned how to fly an airplane [Rod is a pilot], I wouldn’t have learned how to drive a combine and a tractor, I wouldn’t have learned Spanish. I wouldn’t have done nearly the things that I’ve done. Who knows what I would have done?” ***** Searching for a successor to editoonist Clay Bennett, The Christian Science Monitor has narrowed the field of possibilities to about a dozen, according to Clayton Jones, the paper’s editor of commentary pages. “There are a lot of good ones out there,” he told E&P. Having their own editorial cartoonist is important, Jones said, because “it’s another voice on the opinion page that’s done in a different format than text—and it draws high reader interest.” Bennett left the Monitor after ten years to join the Chattanooga Times Free Press as of January 1, replacing Bud Plante, who left Tennessee paper for the Tulsa World, which has been without a staff political cartoonist since the death last year of Doug Marlette. Bennett left the Boston-based paper because, he said, he wanted to do cartoons on local issues as well as the national and international matters that are the Monitor’s focus, and he wanted to move back South; his previous staff position had been in Florida at the St. Petersburg Times, where he had been unceremoniously fired, ostensibly for budget reasons but probably, as it developed over the years, because he didn’t share the same political views as a newly arrived editor. Interviewed by Ayumi Fukuda at businesstn.com, Bennett said the “top three priorities” for him in considering a cartooning job are “editorial freedom, job security, and quality of life. The way I see it,” he continued, “the Chattanooga Times Free Press is three for three. My highest priority, of course, would be editorial freedom. The conversations I’ve had with my old pal Bud Plante about his experiences in Chattanooga, along with my discussions on the topic with the newspaper’s publisher, Tom Griscom, convinced me that this job would offer the kind of latitude that I desire. Editorial freedom is a huge issue for any cartoonist, and a major factor in the quality of any cartooning job.” The University of Iowa now has an online digital collection of the political cartoons of one of the genre’s pacesetting practitioners, Jay “Ding” Darling of the Des Moines Register (dates of his life here). Ding was one of the first editoonists to be syndicated. Drawing nearly one cartoon a day from 1900 until he retired in 1949, he produced, he once estimated, 15,000 cartoons. The Special Collections of the UI Libraries has scanned about 6,000 of the original drawings, “along with proof sheets and microfilms,” reports Matt Kelley of Radio Iowa News. ... Mike Riga at the Brandeis Hoot (thehoot.net) lists the following as his five favorite (perhaps his notion of “the best”) movie adaptations of comic books: “Constantine” is fifth; then “Sin City,” “Hellboy,” “Road to Perdition,” and, ranking first, “Batman Begins.” Riga’s criterion, apparently, is faithfulness to the original four-color incarnation. If you want to play this game, you might begin with a copy of Film & TV Adaptations of Comics: 2007 Edition, a 149-page book by ComicsDC blogger Michael Rhode and Manfred Vogel, that lists thousands of adaptations in the U.S. and worldwide (E&P); for more about it, visit lulu.com. Manga have arrived in France, reports Takashi Morioka at nichibeitimes.com. French translations of manga have been produced for about 20 years, but recently, stores specializing in the Japanese genre have opened for business, which, apparently, has been brisk. Meanwhile, at the New York Anime Festival, December 7-9, the buzz, reported PW Comics Week’s Heidi MacDonald, was about the announcement that Marvel and Del Rey’s manga arm will hook up to produce manga interpretations of the X-men franchise. Aiming directly at the huge manga audience in this country, the first X-men title will appear in the spring of 2009; starring Kitty Pryde, the only girl in an all-boy mutant school, the X-men will be “re-imagined in a shojo (girl’s) manga version. The second title will be a shonen (boy’s) version of Wolverine.” The other excitement at the Fest, if we are to judge from another PW Comics Week report by Kai-Ming Cha, Brigid Alverson, Ed Chavez and Laura Hudson, was “bumping shoulders with waves of girls in super frilly dresses—‘gothic lolitas’—and all manner of anime fans in costume and out. The Anime Network’s maid café, where ‘waitresses’ dressed up in maid outfits (actually, adorably energetic teens, delighted to pose and dance for the cameras) greeted customers with a bow and attracted hordes of equally adorable dancing and enthusiastic teenage co-players.” The manga sex fantasy come to life, sounds like to me. John Lustig’s Last Kiss comic strip, which converts terribly serious old romance comic book art into contemporary comedy with new speech balloons speeches by Lustig, was among the casualties at the Seattle Times when the paper laid off 17 staffers in the circulation department, stopped publishing a Sunday tabloid news section for regional residents, consolidated weekday and Sunday features, and, starting in 2009, reduced the newspaper’s width by an inch to save newsprint. Lustig’s fans rained e-mail on the paper, to no avail. Last Kiss can be seen in the monthly Comics Buyer’s Guide. ... Howard Huge is back in Parade magazine; the issues of December 30 and January 6 carried the Bunny Hoest-John Reiner feature, which has been a stalwart in the weekly for several generations. ... Prince Valiant, launched in 1937, passed its 3,700th mark on January 6, 2008. ... USA Weekend is now posting its first online comic strip: by the magazine’s Creative Manager, Casey Shaw, Thurbear is a somewhat rumpled-looking version of a Care Bear (rumpled in attitude, too: he calls himself “The Couldn’t Care Less Bear”). The strip, often a single strip-wide panel, is posted weekly on Thursdays at USAWeekend.com; click on “cartoon.” ... In Singapore last month, a cartoonist “who goes by the name Peter Draw,” drew 952 caricatures, working non-stop (drinking only water but not taking so much as a toilet break) for 24 hours in a public park to raise money for Habitat for Humanity Singapore. Instead of paying Peter, his victims donated money to the cause, altogether more than $8,000 Singapore dollars, about $1,000 more than was needed to build a home, saith Margaret Perry at channelnewsasia.com. **** David Michaelis’s penultimate draft of his controversial biography, Schulz and Peanuts, was 1,800 single-spaced typewritten pages long. A two-volume opus being out of the question, he pruned the text to 900 pages—partly by excising every non-essential word or phrase, partly by pulling out whole storylines. Among the casualties, I suspect, was an examination of how Schulz’s second wife, now his widow Jeannie, appeared in the strip. Schulz’s first wife was pretty clearly reflected in the bossy Lucy; Jeannie, however, apparently inspired Charlie Brown’s gentle little sister, Sally. Michaelis’s cuts short-changed the last 20 or so years of Schulz’s life: fewer than 100 of the volume’s 566 narrative pages are devoted to Sparky’s second marriage and his subsequent career. That abbreviation accounts for some of the Schulz family’s objections to the book, but they have others, focused on factual inaccuracies and on what they regard as a skewed portrait of the cartoonist. ... Wiley Miller devoted the Non Sequitur releases of October 30-November 3 to ridiculing Michaelis’s apparent strategy in the book. In this sequence, the little girl Danae takes notes for a biography she plans to write about her father if he ever becomes “a beloved public figure,” transforming the commonplaces of his life into tragic or uncomplimentary terms. When her father deftly catches a housefly in mid-flight, exclaiming, “Gotcha! Ha! I’ve still got it—king of the fly snatchers!”, Danae jots down: “He had a lifelong penchant for killing small creatures.” I’m not sure I’d go quite that far, but Michaelis has given Wiley plenty of grounds for precisely this kind of satire. My 9,000-word review of the book and reviews by several others, including a critique by Schulz’s oldest son, Monte, will appear in a forthcoming issue of The Comics Journal. The originals of Wiley’s satirical sequence he has donated to the Charles M. Schulz Museum in Santa Rosa, California. The Reserve Bank of India is producing comic books to teach customers “financial literacy,” according to timesofindia.indiatimes.com. So far, two titles of the series are published in 13 languages, aiming at “children, and semi-urban and rural folk.” RBI plans five more titles, each focusing on different aspects of personal banking and financial management. ... Several universities have launched courses teaching how to make comics, among them: University of Cincinnati, U. Of Alaska - Fairbanks, Savannah College of Art and Design. Lisa Cornwell at AP reports that Ben Towle, director of the National Association of Comic Art Educators, says it’s too soon to have hard data on numbers or where new classes are being taught, but the Association is fielding many more inquires about starting classes. The cause of this a-borning burgeoning is, undoubtedly, the emergence of the graphic novel as a culturally respectable literary form. Gee, I didn’t know there was a “National” Association of Comic Art Educators. How many of them can there be? How many is an association’s worth? Good news, though, no matter how many (or few). ... A new game, available at Target and Barnes & Noble for $25, is based on The New Yorker’s back-page cartoon-captioning contest. The game version of the exercise requires each of 3-6 players to devise in 45 seconds a caption for a captionless cartoon dealt from a deck of cartoon cards; the dice roller picks his or her favorite and then tries to identify which player wrote it. At the Houston Chronicle, the reviewer liked the “creative calisthenics” for the brain but thought 45 seconds was a bit too short a time to concoct New Yorker-style comedy. A sample cartoon shows a giant cat eyeballing a mouse hungrily. One of the players wrote: “You wouldn’t happen to be that cartoon cat who eats only lasagna, would you?” Aleksandr Sdvizhkov, once deputy editor of the now defunct Belarus weekly newspaper Zgoda, was sentenced to three years in prison for “inciting religious hatred” by publishing eight of the Danish Dozen in February 2006 (pajamasmedia.com); other editors who have been brought to trial in various countries for the same offense were fined but none, as far as I know, have done time. It’s likely that Sdvizhkov’s jailing was motivated by political concerns other than the strictly religious. For one thing, the offending issue of the paper never reached any readers: upper management stopped distribution before it got to any vendors in Minsk. For another, Zgoda was shut down two days before the presidential election; “the cartoon affair was seen as a pretext for taking action against a news outlet covering the candidate” opposed to dictator Aleksandr Lukashenko. ... Cartoonists in many other countries often lead harrowing lives for expressing their opinions. But in Africa, they have been enjoying somewhat greater freedom to express themselves these days than of yore, according to a 1997 report at WACC Global’s website by Gado, a Tanzanian cartoonist. (Yeh: I know it’s an old report, but I believe it still sheds light on the dark continent.) In 1988, editoonist Janathan Zapiro had to go into hiding, fearing for his life, after cartooning against the apartheid regime of the day. But with the growth of multi-party politics in most African countries during the 1990s, freedom of the press has emerged, and cartoonists began to feel less intimidated. The satraps of government in some countries, however, still often behave in dictatorial fashion, so while cartoonists feel freer, they are still somewhat wary. Freedom of expression isn’t quite guaranteed everywhere in this happy land either. David Steward, an employee at the Catfish Bend Casino in Iowa, found that too much truth can be hazardous to your employment. He posted one of Scott Adams’ Dilbert strips on an office bulletinboard and was fired for it. In the strip, according to the Associate Press, the following exchange takes place: “Why does it seem as if most of the decisions in my workplace are made by drunken lemurs?” Decisions are made by people who have time not people who have talent.” “Why are talented people so busy?” “They’re fixing the problems made by people who have time.” Steward’s employers quite rightly thought the comic strip was characterizing them as drunken lemurs for their decision to lay off employees. They found that characterization “very offensive,” Clark Kauffman reported in the Des Moines Register on December 19—so obnoxious, in fact, that they were moved to review surveillance tapes to learn who had posted the comic strip, whereupon, they fired Steward. At a hearing about Steward’s unemployment benefits, a judge ruled that posting the strip was “a good-faith error in judgement.” E&P reported that when Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist blog told Steward’s story, cartoonist Norm Feuti responded, saying that some store managers get upset when their employees post copies of his strip, Retail. Said Feuti: “Sounds like these managers see a little too much of their own asinine behavior on the comics page. As far as I’m concerned, firing or threatening to fire an employee for hanging up a comic strip is nothing but an admission of guilt.”

*****

Playboy displays its sense of wonder with its February issue’s cover, Wonder Woman as

enacted by Tiffany Fallon, Playmate of the Year 2005, who shows up

entirely naked except for a pair of knee-length red boots. The rest

of the classic WW costume, star-spangled bikini bottom and red

skin-tight tube top, are painted on her ample epidermis in red, blue

and gold. The other issue to which the Wondrousness of Decorating Tiffany steers us (make way for a segue of staggering proportions) is the strike by the Writers Guild of America. At last report (Entertainment Week for January 25), the strike may have stopped production on Warner Bros’ “tentpole for summer 2009, ‘Justice League of America’” (among whom, Wonder Woman is numbered—hence the ingenuity of the segue, kimo sabe, the cover of Playboy and all—but say no more about tentpoles) (or Irish McCalla, for that matter). From the January 18 EW: “Filmmakers would like another script rewrite and are now debating whether to begin shooting without one.” They confront a January 15 deadline “to either greenlight ‘League’ for a spring production start ... or push it into the post-strike ether,” which, presumably, would put off the film’s release until the next summer, winter being a bad time for superhero shenanigans on the big screen. The strike could also affect this summer’s Sandy Eggo Comicon, lately a froth of movie moguls and actors and actresses. Said Peter Rowe at the San Diego Union-Tribune: “Sure, producers and PR people will still hold panels in Hall H to preview new product. But don’t the fans go to these panels to see the actors and the ‘star’ directors and writers? Even if the strike is settled by spring,” he continued, “it’s unclear whether Hollywood will have anything fresh to display by July 24, when the four-day Con opens.” The strike hasn’t affected animated cartoons because, Lorenza Munoz at the Los Angeles Times tells us, “animation writers are not employed under the same WGA contracts that cover live-action movies and tv programs. ... Animation largely falls under the jurisdiction of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, a union rival not on strike—or no union at all.” Moreover, since there’s virtually no limit to the number of times an animated program can be repeated and since most networks have vast inventories of vintage animated shows, none of the animated programming on tv is likely to feel any pinch from strikers. Brian K. Vaughan, one of the writers on “Lost,” will probably be devoting more of his energies than usual to his funnybook gigs, interrupting that work just to walk a picket line. To shed some light on what all the WGA excitement is about, Karyl Miller, president of the Southern California Cartoonists Society and a writer for movies and tv, posted a notice from the presidents of the WGA about negotiations up to the end of November. At issue is the recompense a writer can expect from material that will be used on the Internet, whether created expressly for that medium or being rerun from other media. For streaming tv episodes, for instance, production companies “proposed a residual structure of a single fixed payment of less than $250 for a year’s re-use of an hour-long program compared to over $20,000 payable for a network re-run. For theatrical product, they are offering no residuals whatsoever for streaming.” WGA presented “a comprehensive economic justification” for its proposals. “Our entire package would cost this industry $151 million over three years. That’s a little over a 3% increase in writer earnings each year, while company revenues are projected to grow at a rate of 10%. We are falling behind.” Which appears to be the reason for the strike. ***** One of cartooning’s pioneering women died of heart failure on January 9 at an assisted living facility in San Raphael, California. Martha Arguello, who used her maiden name in signing her cartoons Marty Links, was 90. For 35 years in a daily panel cartoon and in a comic strip on Sundays, she retailed the trials and tribulations, mostly of the romantic yearning sort, of Emmy Lou, a typical American teenager, who debuted under the title Bobby Sox on November 20, 1944, in only one newspaper, the San Francisco Chronicle, where Links worked in the Women’s World department. We’ll post a brief biography and a lingering appreciation of Links’ achievement next week in Harv’s Hindsight. ***** 2008 Birthdays: Sixty years ago, Bugs Bunny entered American folklore when introduced (albeit not by name) in “Porky’s Hare Hunt,” directed by Ben “Bugs” Hardaway. The sassy rabbit, whom animators in the studio began to call “Bugs’ bunny,” reappeared the next year in“Hare-um Scare’um”; then in 1940, Chuck Jones used Bugs’ bunny for his “Elmer’s Candid Camera” in which Elmer Fudd goes looking for “wabbits” to photograph; later the same year, Tex Avery borrowed both Elmer and Bugs’ bunny for “A Wild Hare,” the film in which the classic hunter-hunted relationship is developed, beginning with Elmer saying, “Be vew-wy quiet: I’m hunting wabbits” after which he encounters his prey, whose first words are: “What’s up, Doc?” The classic wise-guy personality was now in place, and over the years, he emerged as the consummate American folk hero, the irrepressible anti-authoritarian. “I know this defies the law of gravity,” he once said, “but I never studied law.” To academics who ponder such things, Bugs is an example of the Trickster, a defiant personage in folklore—like Puck in Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” And just 75 years ago, The Lone Ranger debuted on Detroit radio. The historic moment occurred on February 2, 1933. Oddly, the story of how he became “lone” wasn’t told until Oliver Drake, a staff writer at Republic Pictures, conjured it up in October 1937 for the first movie serial, released in 1938. The Lone Ranger’s origin is a more-or-less familiar scrap of popular culture, but the story of the creation of the character is not so well-known. It is a Rashomonic tale that varies depending upon who we listen to. Most agree, however, that there were three principals: George W. Trendle, the owner of radio station WXYZ in Detroit; his drama director, writer James Jewell; and scripter Fran Striker, who was writing stories for radio from his home in Buffalo, New York, syndicating broadcast rights to stations around the country. The ingenious and persistent Dave Holland integrated the often contradictory pieces of the story into a seamless whole in his 1988 tome, From Out of the Past: A Pictorial History of the Lone Ranger. We regaled you with extensive excerpts in Opus 192, to which you can return if you want to refresh your memory about the whole sordid process. And it was a process, an evolution, with not just one creative intelligence, but three. The Lone Ranger arrived in the newspaper funnies on Sunday, September 11, 1938; the daily strip started the next day. Both were drawn by Edmund Kressy, whose ability was marginal. He once had LR mounting his horse Silver from the wrong side; and he insisted on putting eyeballs behind the mask, which gave LR a pop-eyed appearance. Kressy was assisted for a time by a more competent artist, Jon Blummer, but the syndicate, King Features, soon passed the assignment on to Charles Flanders, who continued the strip from January 30, 1939, until December 1971. The strip was reprinted in various comic book reprint anthologies, Magic Comics, King Comics and Ace Comics, and occasionally in Dell’s Four-color series. The Smurfs turn fifty next October, but in Belgium, they started celebrating early. During the first week of January, Smurfberry cake and sarsparilla juice were served in Brussels to honor both the tiny shirtless, blue-skinned forest-dwellers and their creator, the Belgian cartoonist Pierre Culliford (1928-1992), who signed his work Peyo and called his diminutive band Schtroumpfs. Reportedly, they appeared first in a 1957 sequence of Johan et Pirlouit, a humorous mock-adventure strip set in medieval times. So maybe they’re 51 years old this year. Another source claims they didn’t emerge from Johan and Peewit (to invoke the American name) until 1960. I first ran into them in my sea-faring days during a 1962 stop-over in Marsailles where I visited a bookshop and bought an “album” reprinting some of the stories that, in accordance with French publication custom, first appeared in weekly installments in Spirou magazine. Once the Smurfs had broken free of their parent strip, their adventures were, for a time, told in an appropriately diminutive mini-comic book, bound into the magazine. The Smurfs came to this country in 1981 when Hanna-Barbera launched them in Saturday morning tv. The original Smurfs were nameless, but the Americanized version gave them names like the Disney dwarfs in “Snow White”—Hefty, Clumsy, Grouchy, Lazy, etc. The tv show lasted until 1990, saith Maurice Horn in The Encyclopedia of Cartoons, from whence some of the foregoing is purloined despite the often questionable reliability of Hornisms. Oh—and Superman. We all know he was born in the late spring of 1938, so he’ll be 70. More than that, I’m sure I don’t need to say. Except—I haven’t seen any signs of a birthday party waiting to pounce in the spring.