|

|||||||

|

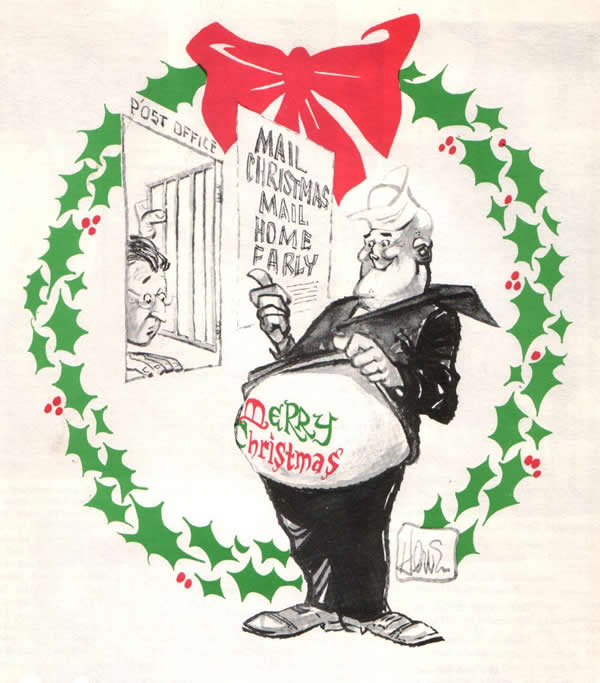

Our bag of gifts for you at this time of year includes an assortment of ’tooner Christmas cards from yesteryear, taken from the December issue of Slice of Wry, the newsletter of the Southern California Cartoonists Society, ably edited by Terry Van Kirk, who assembled these specimens from who knows where.

Beyond that, our chief focus this time is on a Round-up of the

Events of the Cartooning Year—best books, best strips, best comics, etc. The

usual array of year-end topics, but this conglomeration includes reviews of

some books I haven’t even read yet, a feat of criticism nearly overwhelming in

its audacity. But we are nothing here if not audacious. The sensation of this

Opus is ex-Mormon editooner Steve Benson’s outing of Mitt Romney’s fraudulent

claim to political independence. We also include an entirely superfluous essay

on the pagan and Christian origins of Hallowe’en and Christmas, say a fond

appreciative farewell to Al Scaduto, and offer one more excerpt from Meanwhile, my biography of Milton Caniff

(to which I’ve shamelessly appended a review of the book by Allan Holtz and

several samplings of other reviews of the book, all, naturally, stupendously

enthusiastic). Here’s what’s here, in order, by department:

Corrections and Up-Dates

NOUS R US

Watterson Documentary?

Another Post-9/11 Graphic Novel by Jacobson and Colon

Marjane Satrapi Doesn’t Like “Graphic Novel”

Disney Religion

Dagwood Shoppes Lets HQ Staffers Go

Spider-Man’s Appeal

Wonder Woman’s Feminism?

THE TRUTH ABOUT ROMNEY’S MORMONISM

From Ex-Mormon Editoonist Steve Benson

Sundblom Was Santa Claus

HALLOWE’EN AND YULETIDE

An Essay on Origins both Pagan and Christian

ROUNDING UP 2007

Best Books of the Year

Reprint Landmarks

Comic News Events of the

Year

Best and Worst Comic Strips

The Worst Thing

Best Comic Books

Anniversaries

Deaths

PEEVES & PERSIFLAGE

Colorado Shooting and the Gun Lobby

Mallard Filmore and Hillary Clinton

AL SCADUTO: Saying Farewell

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE

Fear Agent, Killing Girl, Blackgass

Warren Ellis Speaks

DEPARTMENT OF SHAMELESS

PROMOTION

Exerpt from Meanwhile—A

Biography of Milton Caniff

Review of Meanwhile by Allan Holtz

The “Best” of the Other Reviews of Meanwhile

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate

the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can

print off a copy of just this lengthy installment for reading later, at your

leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu—

CORRECTIONS AND UP-DATES

Right Up C’here, In Front

Where You Can’t Miss It

Sorry, my mistake—Newsday is not, as I averred last time, without a full-time staff editoonist. Walt Handelsman, who won the Pulitzer

last year, is on staff there, all the time.

And

“the Girl of Qatif” who was sentenced by a Saudi Arabian court to prison and

200 lashes after being gang raped was pardoned last week by King Abdullah. Her

offense, you’ll recall from Opus 215, was being in a car with a man she was not

related to when seven men attacked and raped them both. Her sentence shocked

many in the West, including George WMD Bush, who said if the same thing

happened to one of his daughters, he would be “angry at those who committed the

crime. And I’d be angry at a state that didn’t support the victim.” Such strong

criticism coming from Saudi Arabia’s strongest ally may have induced the Saudi

monarch to (as he put it) “alleviate the suffering of his citizens” even

though, in this case, he was, he said, convinced that the initial verdict was

fair.

NOUS R US

All the News That Gives Us

Fits

Caricatures and animation can help catch criminals,

according to a study by Charlie Frowd reported at gadgetell.com by Colbert Low.

Recognition rates improve among eye witnesses to crimes when they see the

accused miscreant’s facial features exaggerated in caricature. ... On the

criminal side, at Rikers Island prison in New York, inmates who are enrolled in

art classes were recently assigned to design a comic book, said Carrie Melago

at the New York Daily News. One

prisoner came up with Hood Surfer, “a teen from Brooklyn who gets hit in the

head by a meteor, causing his skateboard to float.” Sound a little familiar?

According to his creator, Darius Welch, an 18-year-old facing burglary and

grand larceny charges, the Hood Surfer “decided to start saving the ‘hood.’”

... A film about Bill Watterson, the

reclusive creator of Calvin and Hobbes, may

be in the offing. Guest blogger Charles Brubaker said at DailyCartoonist.com

that cartoonist Keith Knight of The K Chronicles has been interviewed

for a Watterson documentary. I doubt that Watterson himself will show up for

it. ... The original art for a 1955 Peanuts strip depicting Charlie Brown and other baseball players in the rain went for

$113,525 at an auction held by the Heritage Auction Galleries of Dallas, saith Editor & Publisher, adding that DailyCartoonist blogger Alan

Gardner attributed the high price partly to the controversial biography of Charles Schulz by David Michaelis. ... Sid Jacobson and Ernie Colon will be back in August 2008 with a sequel to their 9/11 Report graphic novel. In the new

160 6x9-inch page book, entitled After

9/11: America’s War on Terrorism (2001 - ), they intend to portray “what we

knew and when, and how we ended up where we are—how America’s War on Terror

unfolded and unraveled.” My guess is that this book will do much better than

the last.

Back

at the Beloit Daily News, which

suspended Wiley Miller’s Non Sequitur because a chicken in a KKK

hood seemed, to some, racist, editor William R. Barth announced on December 18

that the paper’s readers had spoken: Non

Sequitur would return to the funnies page. “The Daily News garnered a bit of national publicity over the chicken

affair,” Barth said in announcing the verdict, “—though not necessarily the

kind we’d want. There’s a big difference, of course, between suspending a

feature and canceling it. Non Sequitur,

like other features that run in the newspaper, is there by invitation. That

invitation can be withdrawn at any time, for any reason,” he finished,

menacingly. “That’s not censorship. That’s business.” Barth also complained,

good naturedly, about cartoonists “sticking together.” He cited the online and

syndicated strip The New Adventures of

Queen Victoria, which consists of a static succession of photos of ol’

Vicky puffing speech balloons of wisdom. (You can see it at GoComics.com.) In

this case, on December 15, three weeks after the Daily News suspended Non

Sequitur, we see her apparently picketing the Beloit Daily News, saying: “Don’t you see? By killing a cartoon

because it was against the KKK, you put your paper in the position of

supporting the KKK!” A voice from inside the newspaper office says: “That logic

escapes me.” To which Vicky retorts: “As does all logic. Good day, sir.”

Marjane Satrapi, who was approached by

Hollywood to turn her graphic novel, Persepolis, into a film almost as soon as the book came out, didn’t, at first, want to make

a film. “I thought it was the worst idea,” she told Jamin Brophy-Warren at the Wall Street Journal. “But they give you

enough money and you can have a studio—you have to be crazy to say no.” The

animated feature was hand-drawn in France rather than being computer-animated

in Asia because Satrapi isn’t computer literate. “I don’t know how to write

email,” she said. But she was the co-director of the film, and so it had to be

hand-drawn so that she would understand what was going on: “If you don’t

understand it, you can’t make changes,” she explained. She doesn’t like the

term “graphic novel,” by the way. “It’s a word that publishers created for the

bourgeois to read comics without feeling bad. Comics is just a way of

narrating. It’s just a media type. Chris

Ware doesn’t like it either: he says it sounds like Lady Chatterley’s Lover.”

A

religious studies professor at Memorial University of Newfoundland will be teaching

the Disney religion in a course

called “Religion and Disney: Not Just Another Mickey Mouse Course” (RELS 3812),

a title nearly provocative enough to induce me to enroll long-distance.

Professor Jennifer Porter believes, quite sensibly, that “belief systems” are

implicit in all Walt Disney’s films. That’s scarcely a novel notion: any film

by any filmmaker, any work of art by any artist, embodies the maker’s beliefs.

In Disney’s case, however, the beliefs doubtless reflect Disney’s upbringing in

a conservative Christian home. Said Porter: “There’s a faith component embedded

in them all. ... [But] Disney movies seem to deliberately avoid direct

religious references and favor supernatural intervention rather than divine

intervention. We’ll study what went into his decision to avoid religious

references, to make religion generic, to have his characters sing songs instead

of offer prayers at crucial moments.” Disguising religion is an honored

Hollywood tradition: how else do you market movies to the largest number of

viewers?—a number likely to include the full range of American religious

convictions.

The

main attraction at Dagwood Sandwich

Shoppes is a 1 ½ -pound, double-decker, 24-ingredient behemoth called “The

Dagwood,” priced at $8.90. The plan for the restaurant chain, launched in May

2006, was similarly ambitious, reports Richard Mullins at the Tampa Tribune. Dean Young, manager of his father’s legacy, the comic strip Blondie, and restaurant executive Lamar

Berry planned to sell about 100 marketing territories in the U.S. for

$200,000-300,000 each. Those who bought them would, in turn, sell franchises at

$220,000 apiece. The company’s website lists 20 locations, including 13 built

and operating and the remainder under development. But apparently the plan is

not unfolding rapidly or remuneratively enough to support the corporate

headquarters, which has laid off most of its staff. Presumably, the

headquarters operation was mostly selling territories and franchises, for which

it once employed “probably fewer than 100 people” but now gets by with only

four. The Sandwich Shoppes are still open and building Dagwoods, and the

company has no immediate plans to do anything otherwise with them.

On

January 9, The Amazing Spider-Man will

begin shipping three times a month for the new story arc, “Brand New Day,” with

editor Steve Wacker holding the reins. In a Marvel Comics news release, Ben

Morse asked Wacker why Spider-Man “continues to endure as such a popular

character.” Said Wacker: “It all boils down to Peter Parker. He’s as

approachable and as likable a charger as you can find in literature. There are

Peter Parkers in everything we read and watch [today], so it’s probably easy to

forget how novel a character he was when Steve

Ditko and Stan Lee create him.”

Everywhere thereafter, heroes with problems popped up. “I think there’s a

certain amount of ‘watching a car wreck’ for a lot of readers,” Wacker

continued, “where we can’t wait to see what goes wrong for Pete. I also think

readers all have that same feeling that if we had these powers, we could find a

way to use them effectively to make a better life for ourselves. Peter Parker

on the other hand sees them as a curse and can’t seem to stop letting his

secret life screw up his private one.” In the new story arc, Wacker said,

“we’re going to take some time to really explore and expand the supporting cast

in a way that I don’t think has been done for a long time.”

Grady

Hendrix in the New York Sun notes

that Wonder Woman’s creator, William

Marston, “never intended Wonder Woman to be a feminist.” A psychologist who

lived with his wife and lover in a cozy menage a trois—“both women served as inspiration for Wonder Woman”— Marston

“felt that women were more honest and unfailing than men, and he championed

their ascent in society.” He also wrote stories in which bondage was a theme.

Wonder Woman’s newest writer, a former hairdresser named Gail Simone, says she has no agenda for her stories. “I just want

to give the reader as good a story as I can write,” she said. In the first

Simone story, Wonder Woman suddenly realizes that the gorilla [sic] gang she’s

fighting is not evil—just misguided. “She lets them move into her apartment but

only after their leader kneels and kisses her lasso.” Thus, Hendrix concludes,

“while the new Wonder Woman series portrays its heroine as strong and

compassionate, it also carries a whiff of slightly sexualized dominance.” In

other words, Wonder Woman is, again, “just the way her creator wanted her.” I

think, though, that Hendrix means “guerilla” not “gorilla.”

The

building that was built in Boca Raton, Florida, to house the International Museum of Cartoon Art has

been standing empty since Mort Walker moved the IMCA out several years ago, but next fall, an upscale, rodizio-style

steakhouse, ZED451, will open on the ground floor of the two-story building,

reports Alexandra Clough at the Palm

Beach Post. Another part of the building will be occupied by a bookstore.

The building is being renovated and transformed into a multi-use complex. A

cultural-arts center will move into the second floor, and another restaurant

will fill out the rest of the ground floor.

ROMNEY, MORMONISM, AND THE

TRUTH ACCORDING TO

CARTOONIST STEVE BENSON,

EX-MORMON

By Dave Astor

Published in Editor

& Publisher online: December 18, 2007; 3:50 pm

Steve Benson, editorial

cartoonist for the Arizona

Republic and a grandson of Ezra Taft

Benson, once Mormon church president, left the church in 1993, the same year he

won the Pulitzer. One of the reasons he left the church, he told Dave Astor at Editor

& Publisher, was because he was

disgusted by Mormon officials trying to fool church members and the general

public into believing that his 94-year-old grandfather was still capable of

leading the church. “He was not mentally or physically in a place where he

could make any meaningful decisions,” Benson said. “I know it because I saw his

condition with my own eyes.” Possessed of an acerbic and inventive wit, Benson,

for as long as I’ve known him, has never been bashful about expressing his

opinions—a valuable occupational hazard for political cartoonists. He has been

critical of George W. (“Warlord”) Bush, and he opposes the war in Iraq. After

Romney’s press conference on religion and politics in America, Astor contacted

Benson to get his take on Romney’s presentation. Benson was not impressed. In

fact, it would be fair to say he was aghast. He refers to his former religion

as a “cult,” and he is highly critical of Romney’s attempt to convince

Americans that his being a Mormon would not affect his behavior in the Oval

Office. Here’s Astor’s article, verbatim and entire except for the portions

I’ve already quoted in the foregoing.

As an ex-Mormon, Arizona

Republic editorial cartoonist Steve

Benson has strong opinions about current Mormon Mitt Romney. He said the

Republican candidate's recent speech on religion should not be trusted by media

people and other Americans. In his talk, Romney said "I believe in my

Mormon faith" while also noting that the church's "teachings"

would not influence his decisions if elected president.

"Yeah,

right," responded Benson, adding that "Romney also believes in

misrepresenting what his Mormon Church actually espouses."

Benson

told E&P that, in his view, a

Mormon believer is required by church doctrine (as dictated by the church's

"living prophet") to "obey God's commands" over anything

else. He said "Romney, like all 'temple Mormons,' made his secret vows

using Masonic-derived handshakes, passwords, and symbolic death oaths that he

promised in the temple never to reveal to the outside world"—and that

Romney also secretly vowed to devote his "time, talents" and more

"to the building of the Mormon religion on earth."

So,

said Benson, the only way Romney could be truly independent of the church as

U.S. president would be to disavow Mormon doctrine. "He hasn't done

that," said the Creators Syndicate-distributed cartoonist.

"When

Mitt says he belongs to a church that doesn't tell him what to do, that's

false; it's a 24/7, do-what-you're-told-to-do church," asserted Benson.

Benson

said journalists have basically given Romney a free pass on the

"fundamental contradiction" between being an observant Mormon and a

U.S. president. "Most journalists don't know about actual Mormon teachings

and practices," noted the cartoonist, adding that they instead see the

religion as perhaps "strange" but "rather benign."

Romney

"needs to face an informed member of the media with 'cojones' who has a

working and perhaps personal experience with Mormonism," said Benson.

"It would be harder for Romney to do his well-practiced duck and

dodge."

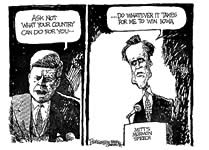

Benson

himself drew a post-Romney speech cartoon that pictured John F. Kennedy saying

"Ask not what your country can do for you..." followed by Romney

saying "...do whatever it takes for me to win Iowa." (Many people

believe Romney gave what he hoped would be a JFK-like speech on religion

because he was losing support in Iowa.) But Benson said he hasn't heavily

focused on Romney's Mormonism in other cartoons. "Religious issues are

very touchy," he said. "I do what I can, but I pick my battles." Another

reason Benson distrusts the words in Romney's speech is because the candidate

has changed his public positions on issues such as abortion and gay rights to

woo conservative GOP voters in states like Iowa rather than the more liberal

voters he once courted to become governor of Massachusetts. "He flips and

flops like Jesus is coming tomorrow," said the cartoonist. "It's like

Romney is reading from the Mormon Church playbook."

Benson

explained his last comment by noting that the Mormon Church has also

"publicly flipped 180 degrees when it feels it's necessary for its image,

for its financial solvency, and for political expediency." He mentioned,

by way of example, that black Mormons weren't allowed into the priesthood until

1978. And while polygamy has been publicly disavowed by the Mormon Church,

Benson said "the church still holds that it will be practiced as a matter

of eternal doctrine in heaven. The church also currently performs polygamist

marriage 'sealings' in its temples around the world."

Benson

predicted that Romney will not win the Republican presidential nomination. If

Romney is nominated, added the cartoonist, he will not defeat his Democratic

opponent.

Voters,

said Benson, "are not ready for someone in the Oval Office who has

committed to absolute obedience to a religion they feel is extremely odd and

not in the American mainstream. I trust the rational U.S. electorate, not the

weird Mormon God."

Immediately upon publication of the preceding

article, Benson began to receive responses, by the bushel. Astor talked to him

again about the reactions and on December 20, wrote the following report for E&P Online (here, verbatim):

When editorial cartoonist Steve Benson criticized

Mormon Mitt Romney in an E&P story earlier this week, reaction was fast and furious. Many blog posters

backed Benson, but many others blasted the grandson of former Mormon Church

President Ezra Taft Benson. For instance, they asked why the Arizona Republic/Creators Syndicate

cartoonist didn't also criticize Mormon politicians such as Democrat Harry

Reid, and they said Benson's 1993 switch from Mormonism to ex-Mormonism made

him as much of a "flip-flopper" as he accused Republican presidential

candidate Romney of being.

E&P called Benson again today to get

his response.

Benson—who

contended in the earlier story that a devout, "temple-endowed" Mormon

U.S. president can't be truly independent of the Mormon Church—said he didn't

criticize Reid because the Senate Majority Leader "is not making an issue

of his Mormon devotion. He's not standing up in a carefully orchestrated stage

play and explaining his religion to the American people. Romney's speech was a

tactical move to woo fundamentalist Christians in the hotly contested Iowa

political caucus. He invited this scrutiny. And, unlike Romney, Reid's not

running for the most powerful position in the free world."

The

cartoonist continued: "Besides, it doesn't seem that Harry Reid's religion

is as strong an operating force in his life or decisions as it is for

Romney." Benson added with a laugh: "How could it be, given the

conservative politics of most Mormons. Hell, Reid's a Democrat!"

Responding

to the flip-flop charge, Benson said he left Mormonism because church leaders

were misrepresenting his aged grandfather's health and because of the

"sexist, racist, and homophobic" aspects he saw in the religion. But

Romney, said the 1993 Pulitzer Prize winner, has jettisoned liberal positions

out of "political expediency" as the former Massachusetts governor

tries to convince conservative GOP voters to make him their presidential

candidate.

"I'm

not running for political office," said Benson. "I left Mormonism

with no pretense of remaining devout— and I didn't do the Romney act of staying

in while changing my spots faster than a leopard on steroids."

When

asked his reaction to the negative e-mails he has received and the critical

blog posts that have been written since the E&P story, Benson said he isn't surprised that Mormons are very defensive about his

comments.

"One

of my Mormon critics called me a 'turncoat,'" Benson e-mailed after

today's phone interview. "So I asked him to be a good Christian, do what Jesus

would do and give me his own coat. Haven't see the coat yet. Anyway, like the

old saying goes, 'hit pigeons flutter.'"

But

the cartoonist feels no one has disproved anything he said about Romney or the

nature of Mormonism's secret temple oaths and rituals. "The proof is in

the pudding," Benson said in the e-mail. "The trouble is, the Mormon

Church doesn't want anyone to go poking around in its pudding."

The

previous E&P article— which can

be seen here—links to the many negative and positive blog comments made about

Benson and Mormonism. It can be found at:

http://www.editorandpublisher.com/eandp/news/article_display.jsp?vnu_content_id=1003686826

Fascinating Footnote. Much of the news retailed in this segment

is culled from articles eventually indexed at http://www.rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html,

the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic

strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes

dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other

sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with

cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s www.povonline.com,

Alan Gardner’s www.DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s www.comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC

blog, http://www.comicsdc.blogspot.com For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you

can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s http://www.strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches

of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

Xmas Factoids

In 2006, a British Reader’s Digest survey found that the “top white lie parents tell

their children” is about the existence of Santa Claus, reported Mike Pearson at

the Rocky Mountain News, “—followed

by the Tooth Fairy, the assertion that carrots give you good night vision and

that picking your nose causes your head to cave in and your nose to fall off.”

The

Amalgamated Order of Real Bearded Santas has more than 1,000 members.

Haddon H. Sundblom unwittingly did more

to make the Santa Claus icon than he did to sell Coca Cola in the winter, and

he did plenty for Coke: winter is not an auspicious season for marketing cool

drinks, but Sundblom’s apple-cheeked Santa, sipping a Coke as he filled

stockings from the late 1930s to the mid-1950s, convinced people that the soft

drink was a year-around beverage. According to James B. Twitchell in his Twenty Ads That Shook the World,

Sundblom’s first model was a salesman friend, Lou Prentis of Muskegon,

Michigan, but after Prentis died, “Sundblom went to the mirror and painted

himself. Haddon was a big man and a big drinker. Mrs. Claus was based on Mrs.

Sundblom.”

Famous

People Born on Christmas Day:

Sir Isaac Newton (1642), Humphrey Bogart (1899),

Alice Cooper (1945).

Famous

People Who Died on Christmas Day:

W.C. Fields (1946), Charlie Chaplin (1977), Dean

Martin (1995), James Brown (2006).

.

HALLOWE’EN AND YULETIDE

An Essay for the Occasion

Nothing terrifies the Righteous quite as much as a

secular holiday. Hallowe’en is suddenly vulnerable. It was, until recently, the

sixth most profitable American holiday—after, in order, Christmas, Mother’s

Day, Valentine’s Day, Easter, and Father’s Day. Lately, I suspect, judging from

the amount of black and orange detritus on display in stores as early as Labor

Day, Hallowe’en has moved up on the list and may be second to Christmas. And

nothing proclaims secularity quite as persuasively as a bloated but satisfied

profit motive. But Hallowe’en terrifies the Righteous for another reason: all those

witches and goblins and ghosties roaming the neighborhood give the holiday a

Satanic nimbus. Letters protesting the worship of the Devil poured into the

local public prints this fall. They all objected to giving countenance to this

hell spawn festival that might also be of pagan origins. I had to smile:

Hallowe’en is no more a pagan holiday than Christmas.

The

clue to its origins is in the name, a contracted form of “hallow even,” the eve

(or evening, the day before) of All Hallows’ Day, now known as All Saints’ Day,

a Christian feast. Until 835 C.E., when Pope Gregory IV moved All Saints’ Day

from May 13 to November 1, Hallowe’en was, indeed, a pagan festival,

celebrating the end of the harvest season in Ireland and elsewhere. Moreover,

the ancient Gaels got extra mileage out of the event by believing that on

October 31, as Wikipedia puts it, “the boundaries between the worlds of the

living and the dead overlapped, and the deceased would come back to life” and

wander around, infesting the neighborhood with their hideous apparitions.

Later, during the Roman occupation of the Celtic country, various Latinate

traditions were incorporated into the festivities, among them, Feralia, a day

in late October that celebrated Pomona, the goddess of fruit, whose symbol was

the apple (from whence, we suppose, the present pastime of bobbing for apples

came). A venerable vegetable is also associated with Hallowe’en—the humble

pumpkin. In Ireland, where the practice of carving a vegetable originated, the

carving was performed on a turnip because, apparently, they had no pumpkins. In

the U.S., pumpkins were more readily available and were larger and easier to

carve. The carved pumpkin with its facial features illuminated from within

where a brain should be is often called a jack-o’-lantern after the Irish

legendary character, Stingy Jack, “a greedy, gambling, hard-drinking old farmer

who tricked the devil into climbing a tree and trapped him by carving a cross

on the trunk of the tree; in revenge, the devil cursed Jack, dooming him to

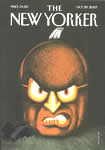

forever wander the earth at night.” The Hallowe’en cover of The New Yorker reminds us that we have

our own Stingy Jack in Darth Cheney, who is parsimonious with news about

government operations, sneaking around to launch nefarious plots in secret and

tricking his countrymen up a tree, where we remain to this day, helpless and

nearly impoverished by Jack’s machinations. Gregory’s

choice of the date to move All Saints’ Day to is consistent with a common early

Christian practice of spreading its beliefs by superimposing on a pagan

festival a Christian holiday, thereby overlaying an ungodly event with a new

religious observance. This maneuver slipped the new religion in on the devotees

of the previous one that already had a religious significance for the native

population, so it was a simple matter to convince them to incorporate other

nuances of theology into their rituals. And since the local populace could

continue to celebrate its traditional pagan rites albeit under a different

name, they were easily “converted” to the new religion.

State

religions had followed this strategy for centuries. When the nomadic Greeks,

who worshiped a male god, Zeus, swept down the Greek peninsula and conquered a

succession of agricultural communities that revered goddesses, usually an Earth

Mother who guaranteed the fertility of the land, the invading Greeks invariably

arranged for Zeus to wed the goddess. The marriage assured the Greeks that the

conquered tribe would be obedient to their new masters just as the wife was

always obedient to her husband. As a simple historical matter, the Greeks’

repeated deployment of this tactic resulted in Zeus having several wives or

mistresses, all preserved in the mythology of the culture.

It

is doubtful, however, that the lamination of All Saints Day onto the pagan All

Hallows Day was another manifestation of the ancient Greek practice. We’re told

there seems to be no actual evidence that Gregory chose November 1 for this

reason. But there is ample evidence that late December was chosen as the time

of Jesus’ birth for precisely the Greek reason—to entice pagan Romans to

convert to Christianity without losing their winter festival, Saturnalia,

which, like similar events in other pagan cultures, celebrated the winter

solstice. In pre-Christian Britain, the winter solstice festival was called

“geol,” from which the present “yule” is derived. The New Testament doesn’t

give us a date for the birth of Christ, so early Christians made one up. It’s

not known, however, when or why December 25 was chosen. The most important gods

in the Mideastern pagan religions of Ishtar and Mithra were born on December

25, so maybe that date was elected to make it easier for adherents of these

religions to convert to Christianity. But December 25 was not popularized as

the date of Jesus’ birth until 221 C.E.; according to Wikipedia, that’s when

Sextus Julius Africanus wrote about it in his Chronographiai, a reference book for Christians.

In

any event, it’s clear from the histories of Hallowe’en and Christmas that both

have their origins in pagan customs. So if we are to eschew Hallowe’en for its

paganism, we must, perforce, abandon celebration of Christmas for the same

reason. And there would be nothing new in that.

Celebration

of Christ’s birthday was not, at first, encouraged. “In 245 C.E., the

theologian Origen denounced the idea of celebrating Jesus’ birthday ‘as if he

were a king pharaoh.’” In the Middle Ages, Epiphany was the event celebrated—the

“showing forth” of the Christ child to the visiting magi, which, by tradition,

took place on the Twelfth Day after Christmas, January 6 (hence, the storied

twelve days of Christmas). But Christmas Day gradually superceded Epiphany as a

public festival, and by the High Middle Ages, caroling—originally dancing as

well as singing—was popular. The custom, which probably continued the “unruly

traditions” of Saturnalia and Yule, was occasionally condemned as lewd, and

“misrule”—drunkenness, promiscuity, gambling—was an important aspect of the

festivities. After the English Civil War, Puritan rulers banned Christmas

celebrations in 1647, and they were outlawed here in Boston for 22 years, until

1681. Christmas festivities fell out of favor in the U.S. after the American

Revolution because they were considered an English tradition. By the 1820s,

“British writers began to worry that Christmas was dying out” and made efforts

to revive the holiday. Charles Dickens’ 1843 book, A Christmas Carol, “played a major role in reinventing Christmas as

a holiday emphasizing family, goodwill, and compassion over communal

celebration and hedonistic excess.” In the U.S., stories by Washington Irving

in the 1820s and Clement Clarke Moore’s 1822 poem A Visit from St. Nicholas performed the same service. So successful

were these efforts that it is today difficult to imagine a time when Christmas

was not a family festival with plentiful food and song and gifts galore.

Once

gift-giving hitched the celebration of Christmas to the capitalistic motive,

the holiday was well on its way in this country to being a thoroughly secular

occasion, represented not by the Nativity so much as by Moore’s jolly old elf

with a white beard. The secularization achieved its apogee in recent times with

efforts by various Concerned Citizens to guarantee the First Amendment’s

separation of church and state by prohibiting the use of public funds for

mounting Christmas displays that involved mangers and sheep and figurines of

infants in swaddling cloths. Last year in the Great Northwest (Seattle?

Portland?), a Concerned Citizen even got a Christmas tree removed from a public

place on the grounds that evergreens are somehow Christian and would therefore

offend non-Christian citizens who happened upon the display. With that, the

probity of Political Correctness reached the pinnacles of absurdity. By

government proclamation in 1870, Christmas was declared a federal holiday, like

the Fourth of July and Veterans’ Day. Because religion is officially excluded from

government by the Constitution (which, as we all know now, thanks to Mitt

Romney, prohibits any religious test as a prerequisite for public office),

declaring Christmas a federal holiday ipso facto makes it a secular occasion,

not a religious one. “Federal” is, by Constitutional definition, not

“religious.” It would be impossible, then, for a municipally funded Nativity

scene in the town square to be seen as a religious symbol. It is, rather, a

secular symbol of the folkways of the society. This convoluted twist of logic

escapes the notice of many citizens, however, who persist in quarreling about

Christmas displays violating the principle of the separation of church and

state—despite the issue having been settled in court several times. In 1984 and

twice in 1999, courts decided that “the establishment of Christmas Day as a

legal public holiday does not violate the Establishment Clause because it has a

valid secular purpose”—namely, I suppose, to sell as many consumer goods as

possible, thereby stimulating an always flagging economy. The U.S. Supreme

Court upheld the latter decision on December 19, 2000.

The

dual nature of Christmas as both secular and sacred inspired such public

spirited personages as Bill O’Reilly to protest loudly and often in recent years

against the secularization of the occasion, seeing in secularization the

vulgarization and co-option of a sacred observance by purely commercial

interests and calling for a return to “the true meaning of Christmas.” Putting

Christ back into Christmas was Reilly’s poignant cry as he tried to rally a

campaign to put religion back into the public square along with Nativity

scenes, sheep, and swaddling cloth. I confess that certain of the P.C. usages

that have cropped up lately—Holiday Tree instead of Christmas Tree, Season’s

Greetings instead of Merry Christmas—are a little cloying in their unctuous

propriety. One year I did a Christmas card (that is, a Holiday Greeting Card)

depicting carolers, and I was about to caption it “God Rest Ye Merrie Gentlemen,”

invoking the old carol, when I realized that “gentlemen” would offend

feminists. Similarly “God” would offend atheists. Removing the offending words,

I was left with “Rest Ye Merrie,” which doesn’t, now that I think about it,

have much connection to Christmas. I guess that was the point of the exercise.

But I’m not an O’Reilly fan, and I don’t want to put Christ back in Christmas:

I want to just leave it in there and not disturb it. We are not a Christian

society or a Judeo-Christian society so much as we are both—and all.

Pluralistic. So we ought to tolerate those who wish their non-Christian friends

“Merry Christmas” just as we tolerate Jewish friends wishing us “Happy

Chanukah” and rabble-rousing friends proclaiming “a Festivus for the rest of

us” during this “winterval.” So Merry Christmas to all of you pagans from all

of us pagans— and to all a good and silent night.

A Few Yaps from Yip

Yip Harburg was the great American lyricist who wrote

“Somewhere, Over the Rainbow,l” “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?”, “April in

Paris,” “It’s Only a Paper Moon,” and Finian’s Rainbow. He also wrote his share

of verse, much of it, perhaps all of it, collected in the aptly entitled Rhymes for the Irreverent. Here are a

couple:

Before And After

I cannot for the life of me

Recall at all, at all

The life I led

Before I tread

This small terrestrial ball.

Why then should I ponder

On the mystery of my kind?

Why bother with my great beyond

Without my great behind?

The Welfare (Island) State

Our affluent society

Provides the poor with piety,

And also a variety

Of homes for many brave ...

The Hospital, the Prison

The Cathedral and the Grave.

Red, White and Blue Cross

you’re paid to stop a bullet,

It’s a soldier’s job, they say.

And so you stop the bullet,

And then they stop your pay.

ROUNDING UP THE YEAR 2007

Once again this year, being of weak will and

enfeebled faculties after weeks of resisting the blandishments of Holiday Sales

in nearby shopping malls, we surrender again to that temptation that insinuates

itself into every periodical at this season: yes, we’ll look back on the last

twelve-month to see what is worth remembering.

In

the late forties and early fifties, the final leafing of the golden autumn of

comic books before the chill of the Code winter, the newsstands overflowed with

scores of new comics every week. No one could have read them all. And nowhere

could we find graphic novels, cartoonist biographies, critical histories or

scholarly dissertations. Just comic books, too many to read regularly. By the time

I returned to the four-color fold in the early 1970s, the gold had faded, and

the quantity was greatly diminished. For a few years, it was possible to read

virtually every comic book regularly published. That changed. And now, we’re in

another golden age, and once again, we are afforded an impossible plentitude.

Comic books—the paginated cartoon strip pamphlets—alone are too many to read

regularly. And to that impossibility, we can add cartoonist biographies,

reprints of classic strips, graphic novels, manga, histories both chronological

and critical. Altogether, 500-600 separate titles every month. A wonderful

heaping up. But the best of the year? Who is equipped with time enough to read it

all and determine which are the best? Herewith, then, not “the best of the

year” but “the best of those I saw this year.” And in the benevolent spirit of

holiday abandon, I deliberately refrain from defining “best.”

BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR

Meanwhile: A Biography of

Milton Caniff, Creator of Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon, by me. If I don’t think it’s one of the

best of this year or any other, why did I do it?

Alexander

Raymond by Tom Roberts;

I’m not sure it’s out yet, but, having seen color proofs of its sumptuous

pages, it’ll be one of the best, however that’s defined.

Abandon

the Old in Tokyo by

Yoshihiro Tatsumi

Brian

Fairrington and Daryl Cagle’s Best

Political Cartoons of the Year, 2008 Edition. Out just a couple weeks ago.

Cartoon

America: Comic Art in the Library of Congress, edited

and with intro by Harry Katz, formerly the graphic arts curator in LOC’s Prints

and Photographs Division; a wealth of often rare examples of the cartoonists

arts.

Killed

Cartoons: Casualties from the War on Free Expression, collected and annotated by David Wallis.

As the Islamic Hooligans gain control of Western Civilization, we need to be

reminded of what we’re losing.

And

a couple graphic novels. I haven’t read that many this year, but two seemed notable: The Professor’s Daughter by Joann Sfar

and drawn by Emanuel Guibert; perfectly charming; and Cancer Vixen by Marisa Acocella Marchetto about the horrors of her

encounter with breast cancer, a cartooning tour de force and a powerful subject

to boot.

Marchetto

has just joined MyBreastCancerNetwork.com “as an expert,” saith

sev.prnewswire.com. She’ll produce a weekly cartoon blog that chronicles her

life as a breast cancer survivor and activist. With typical iconoclastic verve,

the fashionista cartoonist says of this new enterprise: “I’m going to blast a

bright light on the dark details of this dreaded disease as I continue kicking

cancer’s bony ass in killer five-inch heels. We are not victims, we are Vixens.

I can’t wait to meet and connect with all you Vixens out there.”

REPRINT LANDMARKS

David Kunzle’s two Topffer tomes: Father of the Comic Strip: Rudolphe Topffer, and Rudolphe Topffer: The Complete

Comic Strips; both from University Press of Mississippi

Pete Maresca’s monumental Sundays with Walt & Skeenix and his Sammy Sneeze; both reviewed last time,

Opus 215.

Ulrich

Merkl’s Dream of the Rarebit Fiend (complete);

another of those giant life-size tomes.

IDW’s Complete Dick Tracy series

Jeff

Smith’s Bone, in color—from Scholastic

More

of J.R. Williams’ “Bull of the

Woods,” a subtitle of Williams’ long-running Out Our Way, in handy paperback from Lee Hardware. (Well, look it

up on the Web.)

Shel

Silvestein Around the World,

obviously intended to make me green with envy. Again.

Fantagraphics’

stunning The Kat Who Walked in Beauty, reprinting the “panoramic” daily strips of 1920, a variety of George Herriman’s cartoon artistry

almost overlooked in the usual fever to extol the wonders of his full-page

weekend extravaganzas. But these vintage Kat dailies are just as impressive, perhaps even more so because Herriman had to

work with a much narrower focus.

Promising Books That I Haven’t Read Yet

Chester Gould: A Daughter’s

Biography of the Creator of Dick Tracy by Jean Gould O’Connell (125 7x10-inch pages, hardback; $45 from www.mcfarlandpub.com ; or 800-253-2187). The author was about four

years old when her father’s classic gumshoe strip was launched in the fall of

1931, so her personal on-site recollections do not include much in detail about

the earliest years of the strip, but she’s mined the family archives for

illustrative materials for her father’s ten previous years in Chicago during

which he submitted 60 comic strip ideas to the Chicago Tribune-New York Daily

News’ honcho, Joseph Patterson, all rejected; the book includes examples of 8

of the 60. Even if she can’t testify out of on-the-spot experience about much

that happened before, say, 1937, when she’d have been about ten, O’Connell, an

only child, was curious about her father’s work and obviously talked to him a

good deal about it. She regales us with numerous anecdotes that were clearly

told to her by her father—like the story of how Smith Davis, an agent for

newspaper publishers, tried to get Gould to leave the Tribune-News Syndicate

for Marshall Field’s embryonic enterprise, the Chicago Sun, to which he had just seduced Milton Caniff in 1944. Field, through Davis, offered Gould the same

guarantee he’d given Caniff: $100,000 a year. Gould’s answer: “I’m not going to

leave the Tribune. ... You give Mr.

Field a big thank you, and tell him I’m working for the outfit that gave me the

only break I’ve ever had in my life, and a million dollars wouldn’t get me

away.”

Stop

Forgetting to Remember (208

6x9-inch pages, often in two colors; hardback, $19.95), an “autobiography” of a

fictional cartooner, Walter Kurtz, by Peter

Kuper, 48, who is actually telling his own life story, or, at least,

significant pieces of it. “I moved my point-of-view over just a bit in part

because most autobiographies diverge from truth all the time, and I was

interested in it as A Story rather just My Story,” he told Gilbert A. Bouchard

at the Edmonton Journal. “This shift

also allows me to keep this project focused.” Continued Bouchard: “The use of

an alter-ego allowed him to work different kinds of comic-art writing into the

book—travel stories, journalism, fantasy, dreams and a wicked parody of Richie

Rich (a comic Kuper worked on in the early 1980s) that slams GeeDubya and his

administration—while still keeping a fairly linear story readers can easily

follow.” I like the Dedication, which begins: “Dedicated to the girls who let

me get past first base and to my wife, who got me home.”

The

System of Comics by

Thierry Groensteen, a comics scholar born in Brussels, Belgium. This volume

(198 6x9-inch pages, hardback; $40), from the University Press of Mississippi

(one of my publishers), is the first English translation of the original 1999

work and fairly bristles with learned argot. Chapter titles alone are daunting

albeit provocative: The Spatio-Topical System; Restrained Arthrology: The

Sequence; and General Arthrology: The Network. “Arthrology” is, I gather, “the

linear semantic relations that govern the breakdown.” It is taken, Groensteen

tells us, from the Greek arthron, “articulation.” By arthrological gyrations, the cartoonist determines the

spatio-topia of his creation—that is, the distribution of spaces and the

occupation of places. Early in his argument, Groensteen writes: “The precedence

[that Groensteen accords] to the order of spatial and topological relations goes

against most widespread opinion, which holds that, in comics, spatial

organization will be totally pledged to the narrative strategies, and commanded

by them. The story will create or dictate, relative to its development, the

number, the dimension, and the disposition of panels. I believe on the contrary

that, from the instant that an author begins the comics story that he

undertakes, he thinks of this story, and his work still to be born, within a

given mental form with which he must negotiate.”

This

is ponderous going, I ween, and may take us nowhere that we haven’t been

before, Groensteen’s contention to the contrary notwithstanding. Groensteen is

audacious enough to believe he is flying in the face of received opinion (or

conventional wisdom) about how comics are made. But, judging—admittedly

prematurely—from the evidence of the quoted sentence, I disagree. Groensteen

seems to be saying that a cartoonist begins with a preconceived notion of the

form his story will take—that is, I assume, a “form” of images in panels

sequenced for narrative clarity. Can’t quarrel with that. But having decided to

tell a story through the medium of comics, the “author” then must do precisely

what Groensteen seems to say he isn’t going to do—that is, adopt “narrative strategies”

that will determine the spatial and topological (amount of space and placement

within it of images, I suppose) relations within the form he has decided to

exploit. How else, after all, could a cartoonist tell a story? Probably

Groensteen will tell us as the tome reveals its secrets, but I’m already

disposed to thinking that the whole enterprise will turn out to be an exercise

in draping high-fallutin’ lingo around the ordinary, traditional and wholly

commonsensical operations of the cartoonist: once committed to comics as a

narrative form, the cartoonist breaks his tale into units of imagery, panels,

and fills the panels with pictures and speech balloons in an order that will

clearly advance his story by providing the essential information, manipulating,

throughout, the size of the images and the frequency of panels in order to

sustain suspense and enhance the drama of the incidents in the story. Or, as

Groensteen puts it, the cartoonist’s “system constitutes an organic totality

that associates a complex combination of elements, parameters, and multiple

procedures.” I thought that’s what I just said, only somewhat less obscurely;

but what do I know? Still, the headings under which Groensteen will do all this

are sometimes delicious—“The Pregnancy of the Panel,” for instance.

The

Supernatural Law Companion: A Readers Guide to Wolff & Byrd, Counselors of

the Macabre, Their Practice, Clientele, and Private Lives, by Jackie Estrada and Batton Lash. At last—a “way in” to one of the medium’s most

tantalizing and deftly executed comic book series, featuring a team of lawyers,

Wolff and Byrd, who represent supernatural beings—zombies, werewolves, etc.

Lash, the cartooner whose creation Wolf

& Byrd: Counselors of the Mcabre is, provides the Introduction, tracing

the history of his brain-child from its 1979 birth as a comic strip in The Brooklyn Paper, a free weekly that

was distributed in the immediate neighborhood of courthouses and law offices in

downtown Brooklyn, through its 1983 reincarnation in The National Law Journal, where it lasted for fourteen years,

overlapping the eventual emergence in 1992 of the spook-bedeviled law firm in

comic book form, soon after Lash married Estrada. The bulk of the volume is

devoted to issue-by-issue synopses of the stories in the comic books, with

“annotations” by page number that explain the often (now) obscure references

with which Lash imbues his tales. The book concludes with a list of characters

and a gallery of pictures showing how the appearances of Wolff and Byrd have evolved

over the years (almost thirty!). And Lash reminds us of his first promotion,

which includes the brilliant tagline: “Beware of the Creatures of the Night:

They Have Lawyers!” Just $10 for 90 6x9-inch pages, black-and-white; www.exhibitapress.com

BOOKS I WANT TO REVIEW BUT

HAVEN’T YET

Arguing the Comics, embodying a brilliantly conceived notion

by Jeet Heer and Kent Worchester, who collect here over two dozen fugitive and

hard-to-find essays about comics written by otherwise sane and dignified

literary critics or popular culture mavens.

Crockett

Johnson’s newly

discovered Magic Beach in m/s; I’ve

read it and it promises to shed light on some of the Barnaby ethos, but I need time to work it out and combine it with a

massive appreciation of the said Barnaby.

A

flotilla of books by some of the legendary limners of the curvaceous gender—Bill Wenzel, Dan DeCarlo, Bill Ward, Jack

Cole—all from Fantagraphics; none published this year, as I recall, but

still, all deserving a long and lingering look.

COMICS NEWS EVENTS OF THE

YEAR

Schulz and Peanuts, the biography by David Michaelis, is

securing its hold on bestseller lists by advertising the Schulz family’s

disapproval of parts of it. Schulz’s story is a fascinating one, and Michaelis

tells as much of it as he can well, often lyrically. But while we come to

realize that Schulz the man was a chronic melancholic, we never meet the

cartoonist, and that’s too bad in a biography of the man who defined himself by

saying he was a cartoonist. My full review will appear in The Comics Journal sometime in February in a special “roundtable

discussion” of Michaelis’ book.

Lynn Johnston’s For Better or For Worse continues as a hybrid, some new, some

reruns.

FoxTrot ends daily releases; only

Sunday from now own; and Bill Amend gets the Reuben at the

annual convention of the National Cartoonists Society in May.

Jim Toomey’s fishy friends in Sherman’s Lagoon take on human form and walk on land for a week or

so.

“Masters

of American Comics” exhibit travels around the country and stirs up the

jawboning classes, who wonder why there are no women masters (or mistresses)

and where Walt Kelly ranks.

In January, Cartoon Network’s “Aqua Teen Hunger

Force” mounts a promotional stunt in Boston that so incites the security

minions that streets are closed and traffic diverted, creating confusion and

turmoil in the city—and raucous hilarity elsewhere.

Death

comes to the funnies again: in Rudy Park,

Uncle Mort expires on Jan 12; in Funky

Winkerbean, Lisa Moore dies of cancer, October 4; and in Dilbert, Asok the Indian genius died

December 7. But he subsequently came back as his own clone.

John Marshall is at last permitted to sign as the

artist on Blondie, Jan 7

Film version of Frank

Miller’s “300" hit theaters in February

Lost Girls by Alan

Moore and Mellinda Gebbie, the

year’s most inflammatory publishing “event.”

American

Born Chinese by Gene

Yang, got almost as much publicity as Lost

Girls because it was the “first graphic novel” to be nominated for National

Book Award; it didn’t win but garnered the NCS best comic book award instead.

(“Comic book”? No, it’s a graphic novel.)

Pulitzer goes to Walt

Handelsman at Newsday; half his

portfolio of 20 submissions included animated editoons; first time Pulitzer has

recognized animation.

International Comic-Con San Diego caps attendance,

setting maximum number for each day’s attendance

Death

of Captain America and, symbolically, of the American values of privacy and

personal liberty

Fantagraphics and Harlan Ellison settle, removing a

threat to the economic viability of FBI

Manga declines in sales in Japan!!

Comic books make it to mobile phones

Reincarnation

of Cartoonist PROfiles on the

dock: Stay ’Tooned!, edited by John Read, out early in 2008 (and I have a

column therein, culled from these very pixels).

Two

releases of Berk Breathed’s Opus dropped because they made

references to Islamic matters

THE WORST AND THE BEST COMIC

STRIPS

Worst new comic strip of the year, Diesel Sweeties, by Richard Stevens

Best Comic Strip of the Year, Brooke McEldowney’s 9

Chickweed Lane. Still.

My favorite R&R posting: “The Unforgettable Jane”

in Op. 202

ANNUAL FRAUD

The New Yorker’s “cartoon issue,” which, while running

more cartoons than usual, is otherwise almost devoid of extolling text, by

which neglect an excellent opportunity to champion the medium is forfeit. Alas.

THE WORST THING OF THE YEAR

Of all the things that happened during 2007, I liked

least the make-over of Betty and Veronica in Nos. 151-54 of Betty and Veronica’s Digest. Ick. The

gang at Archie supposed this treatment would bring in rafts of manga fans.

Dunno if it did. But if it did, get ready for a massive re-design of Bob Montana’s characters, whose

appearance was perfected by Dan DeCarlo. (And if you don’t know who Dan DeCarlo was, you can find out more with at least

two Fantagraphics books, aforementioned.)

BEST COMIC BOOKS

Army@Love by Rick

Veitch

Darwyn Cooke’s monthly Spirit books from DC

Casanova by Matt

Fraction with art by Gabriel Ba and Fabio Moon

Welcome to Tranquility by Gail

Simone with Neil Googe’s art

ANNIVERSARIES

Centennials for Mutt

and Jeff, Milton Caniff’s birth,

ditto Herge’s.

Andre Fanquin’s exquisite Gaston Lagaffe is 50; and so is the Association of American

Editorial Cartoonists and Dr. Seuss’s Cat

in the Hat

Creators Syndicate is 20

Wiley Miller’s Non

Sequitur, 15 as of February 16

Comic Press News was 16 in April

Stan Sakai’s Usagi

Yojimbo reached No. 100 at Dark Horse

PASSIN’ THROUGH

Sometimes Happy, Sometimes Blue, But We’ll Remember

You

Those Who Left Us in the

Last Twelve Months Or So

Since We Last Ran Up This

Sad Tally

Jerry Bails, creator of fandom

Paul Rigby, Australian editooner

Dave Cochran

Chris Glenn of CBS radio news, friend of my youth

Joe Barbera

Marty Nodell, creator of Green Lantern

Jack Burnley, creator of Starman

Joe Edwards,

co-inventor of Archie

Iwao Takamoto,

creator of Scooby-Doo

Jay Kennedy,

editor in chief at King Features

Marshall Rogers

Johnny Hart,

creator of B.C. and The Wizard of Id

Brant Parker, who

drew The Wizard of Id

Doug Marlette,

editoonist and stripper with Kudzu

Roger Armstrong

Buck Brown of Playboy’s libidinous Granny fame

Howie Schneider (Eek and Meek, Sunshine Club, Circus of P.J.

Bimbo)

J.B. Handelsman,

New Yorker ’toonist

Silas H. Rhodes,

founder of the Legendary School of Visual Arts

David Hilberman,

co-creator of UPA studio

Shirley Slesinger

Lasswell, widow of Fred (Snuffy Smith) Lasswell, last seen suing Disney for her share of their Pooh proceeds

Phil Frank of San

Francisco

Richard Goldwater

at Archie Comics

James Kemsley,

the Aussie who did Ginger Meggs

Bob Bindig

Paul Norris,

creator of Aquaman and longtime steward of Brick

Bradford

Al Scaduto (see

below)

*****

PEEVES & PERSIFLAGE

Cal Thomas is on

the cusp of wetting his pants with excitement over the recent shooting in a

megachurch in Colorado Springs just south of Denver. A crazed 24-year-old man

named Matthew Murray, brooding over how much the world owed him and how little

he was collecting in wealth or fame or friendships despite his having solicited

at local church institutions, spent a year arming himself with an assortment of

handguns and assault rifles and focusing his a vengeful discontent on

“Christians,” who, he said on the Internet, “are to blame for most of the

problems in the world,”and then on Sunday, December 9, he loaded up his arsenal

and stormed into a church-sponsored youth mission, shot and killed a couple

people, then drove to the sponsoring church, parked in the church parking lot

as the congregation was leaving the morning service, and shot and killed some

more people, two teenage girls and their father; he survived, they didn’t. Then

Murray entered the social hall of the church. There, he was confronted by a

former police woman, Jeanne Assam, who was serving as a security guard in the

church. She

drew her handgun

and shot him. She didn’t kill him, but her shots halted his progress, and he

thereupon turned one of his handguns on himself and committed suicide.

Several

curiosities attend this event. First, Assam was licensed to carry a concealed

weapon and was a trained law enforcement officer, and she was “on duty” at the

church, doing what she’d volunteered to do—provide security and protect the

population. Second, Murray obtained all of his arsenal legally, over a year’s

time, complying with all gun laws, none of which disqualified him from owning

weapons. Third, apparently a lot of churches now engage security guards to

protect their parishioners attending religious or recreational activities on

the premises. Fourth, Assam conducted herself in every way “by the

book”—identifying herself to Murray as a security guard and demanding that he

put down his weapons, and, when he continued shooting, she stood in the

hallway, oblivious to the danger, and fired at him. Fifth, Assam is a very

photogenic woman with long layered blonde hair, which, together with her

thoroughly professional demeanor and courage under fire, makes her an ideal

front-page totem for gun ownership. (Here she is, being thanked by a grateful

parishioner.) For

Cal Thomas, the incident validated the gun lobby’s contention that the right to

bear arms is the best insurance against lawless violence. “I’ve been waiting

for years for this to happen,” he crowed. “The unarmed (disarmed?) are easy

targets for crazed gunmen armed with grievances, weapons and ammunition. Now

someone has shot back, probably saving many lives. All the gun-control laws

that have been passed and are still being contemplated could not have had the

affect of one armed, trained and law-abiding citizen on the scene. ... The

point is that gun laws will not deter criminals with evil intent and police

can’t be everywhere they’re needed. But killers can be stopped by law-abiding

citizens with guns.”

Despite

my profound aversion to guns as toys or armament, it’s hard to argue with

Thomas’ conclusion. Here, the gun laws didn’t stop Murray from arming himself

to excess. Time and again recently, we’ve seen well-designed gun-control laws

rendered ineffective simply because those charged with enforcing them

overlooked something. With our human propensity for error, no network of laws

is likely to be leak-proof—particularly in a society as solicitous of privacy

and individual freedoms as ours. I’d feel a lot better if we weren’t such a

gun-totin’ bunch in this country. But we are. And as a result, I doubt that any

truly effective gun-control legislation can ever be enacted. Whether such laws

should be on the books or not is beside the point. The point, I suppose, is

that we are a society that has in its churches armed security guards who

believe God stands by their sides as they gun down rampaging intruders. That’s

what we’re living with.

Pat Bagley’s cartoon on the Colorado shooting has layers of meaning: he manages to depict the unyielding dedication of the gun lobby, giving it a frenzied religious tinge that echoes the motives of deranged Murray. Pithy Pronouncements

Time flies like the wind; fruit flies like

bananas. —Gus Arriola

Give

me levity or give me death. —A Nony Mous

The

income tax has made liars out of more Americans than golf.—Will Rogers

The

sport of skiing consists of wearing $3,000-worth of clothes and equipment and

driving 200 miles in the snow in order to stand around at a bar and get drunk.

—P.J. O’Rourke

Mallard Is an Example of How

Women in Politics Are Treated

From Daily Record, www.kvnews.com; December 14, 2007

To the Editor:

Directly

after watching Bill Moyers' Journal on PBS Friday night, I picked up the Daily Record and turned to the editorial

page, and, though I seldom do so, read the political cartoon, Mallard Fillmore, which once again

attacked Hillary Clinton. The

irony did not escape me.

Bill

Moyers' guest had been Kathleen Hall Jamieson, who spoke on misogyny on the

Internet in particular, and sexist vilification of female political candidates

in the mainstream media in general.

Jamieson

suggests that there is a deep fear in America about women holding power; that

the assumption is that any woman in power will by necessity emasculate men.

Jamieson goes on to say that Americans have a long history of sexist attacks on

women in power, frequently using religion to reinforce patriarchal ideas.

On

the Internet, portraying Ms. Clinton with graphic sexual images and vulgar,

gross, profanity reduces her to a sexual stereotype, increasing the likelihood

that people won't vote for her based on what she can offer the country as a

candidate, but rather on perceptions of her as a female who somehow doesn't

exemplify the feminine ideal.

By

portraying Clinton as having no qualifications beyond being married to a former

president, Mallard Fillmore planted

the idea that she has value only in the traditional role of wife, disregarding

any other career qualifications she possesses.

Treating

a viable political candidate with nastiness and disdain because of sex, race,

or religious belief is not only injurious to women, but also harmful to the

humanity in all of us. Americans must move past their fear and distrust of

powerful women and find a candidate to support, rather than denouncing one

because of a campaign of hate and raw sexual violence.

Anna

C. Powell

BADINAGE AND BAGATELLES

At comicbloc.com,

Eric Moreno interviewed Greg Rucka,

asking him, among other things, if he remembered the first time he realized

there was a craft going on in the stories. Rucka said: “Daredevil: Born Again.

I remember going, ‘Holy shit! This is actually being written.’ And, ‘Holy Shit!

Look at this art! I’ve never seen anything like it!’ And, ‘Holy Shit! Look at

the way the point of view shifts. They’re using different first-person

narration!’ I went nuts. I blame Frank

Miller, as most of us do.”

John Romita, Jr., asked in 2001 by

Henrik Andreasen if his father influenced him, responded (as quoted in

Sequential Tart last month): “He affected me in my way of life because he is my

father, and that has translated into my art and storytelling, but the art is

different because we are different people. Growing up, his artistic influences

were mostly cinematic because he is big on films, and we would talk about the

same movie over and over.” Andreasen then observed that JRJR is “obviously

influenced by Kirby,” noting that JRJR made use of “Kirby’s ‘dynamic blockiness’”

in his run on Thor. Said Romita: “I

find the assessment to be true. Kirby’s influence is, among other things, due

to his work on his character Thor, and when I began to do Thor myself, my

influence by Jack Kirby became more

apparent because of his influence on me when I was younger. Just like John Buscema has influenced me—and, of

course, my father, as I mentioned before. One of the more important things my

father taught me was how to weight the illustrations—when to hold back, and

when to use a lot of power.”

Art

and Life and Tragedy. Holding up a mirror to reality in New Orleans’

Lower Ninth Ward one day in December, actors from New York stood among the

weeds in a blasted block of destroyed houses and dead trees and presented

Samuel Beckett’s bleak 1949 play, “Waiting for Godot.” Godot, you’ll remember,

never showed up.

WE’RE ALL BROTHERS, AND WE’RE ONLY PASSIN’ THROUGH

Sometimes happy, sometimes blue,

But I’m so glad I ran into you---

We’re all brothers, and we’re only passin’ through.

Old Folk Ballad Lustily Sung By Walt Conley in His

Trademark Husky Rasp of a Voice at the Last Resort in Denver, Lo

These Many Years Ago

Al Scaduto, 1928-2007

Al Scaduto, who

cartoonist Mike Lynch called “the last of the great bigfoot cartoonists,” died

December 7, Pearl Harbor Day; he was 79. Scaduto’s professional biography is

remarkably short: he spent his entire career doing the syndicated panel cartoon

feature, They’ll Do It Every Time, but in perpetuating this happy relic from another age, Scaduto performed a minor

miracle: visually, he gave it a modern up-to-date patina while preserving its

vintage aura.

Scaduto

was born July 12, 1928, in the Bronx, New York. He attended the School of

Industrial Arts, now called the School of Art and Design. SIA was founded, Scaduto

liked to report, by four young art teachers in 1936 who built desks from old

orange crates and plywood. At SIA, Scaduto met a trio of other students, all

destined for cartooning—Sy Barry, Joe

Giella, and Emilio Squeglio.

Scaduto also attended classes at the Art Students League, and he sold his first

cartoons while still in high school at SIA. Needing money to attend his senior

prom, he worked up two pages of comics and sold them to King Features for its Popeye comic book. When he graduated in

1946, he knocked again at the door of the syndicate. “I thought I would give it

a shot,” he told Dirk Perrefort at the Connecticut

Post last winter, “and they gave me a job as an office boy. I did that for

about eight months before they made me a corrections artist.” Two years later,

he was working on They’ll Do It Every

Time (“TDIET,”as it’s often abbreviated).

TDIET

takes a humorous look at human hypocrisy, ironically dramatizing the

inconsistencies and quirky twists of fate that plague us all. Its purpose, said

Martin Sheridan in his Comics and Their

Creators, is to “deflate the ego of chiselers, pests, fakers, office

loafers and bombastic bosses. The human failings depicted strike a responsive

chord because the incidents are true to life, sugar-coated with humor to bring

a good-natured laugh at the expense of a familiar figure in home, office or

country club.” In his Comic Art in

America, Stephen Becker elaborated: “Behind every assertion of the human

ego, there lurks a blatant hypocrisy. Behind every accident of bad timing,

there lurks a malignant fate.”

Essentially

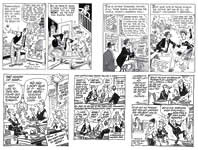

a panel cartoon, TDIET often takes two panels to make its point. Here’s J.P.

Honcho, for instance, berating his secretary Lula for being a few minutes late

to work: “Nine o’clock means nine o’clock! I don’t care if your bus broke

down—no alibis, y’hear?!” But in the next panel, ol’ J.P. is dictating a letter

to the self-same Lula, making up excuses for being weeks late with a shipment:

“Dear Sirs—uh, er—due to conditions beyond our control—floods, strikes,

blizzards—y’know, Lula—stall ’em for a month or so—yas, yas. ...” Over Lula’s

head hovers a silent scream, labeled “The urge to ship him to the moon

posthaste.”

In

another recent TDIET, wife Annoya urges husband Arfo on to shovel the walks in the

dead of winter: “You can do it! It’ll only take you two hours or so. The

exercise will do you good!” But when, come summer, Arfo picks up his bag of

clubs to go golfing, Annoya sings another song: “Golf? No, no—lugging that

heavy golf bag can’t be good for you. You’ve got to take it easy, y’hear?” To

which Arfo responds with a thought balloon, invoking a comment that frequently

accompanies such reverses: “It’s enough to make a grown man cry, but good.”

The

feature was invented on February 5, 1929 by sports cartoonist Jimmy Hatlo at the old Call-Bulletin in San Francisco. Legend

has it that Hatlo conjured up the first one to take the place of a syndicated

cartoon that got lost in the mail, failing to arrive by press time. It

stimulated enough response from readers that Hatlo repeated it occasionally,

then regularly—prompted, usually, by readers who submitted examples of life’s

little hypocrisies from their own experience. In 1936, King Features picked it

up for national distribution, beginning May 4, and “They’ll do it every time”

was soon a catch phrase nationwide. Readers who sent in ideas that Hatlo used

he acknowledged “with thanx and a tip of the Hatlo hat,” giving their name and

home town with a drawing of a tiny comic character tipping his fedora in a

credit box at the bottom corner of the feature. By

the mid-1940s, Hatlo had acquired an assistant and stopped working full-time on

the feature. In 1948, the assistant, Bob

Dunn, needed help and turned to Scaduto. By then, one of the characters in

the panel had developed into her own Sunday strip, Little Iodine, which debuted July 4, 1943. She was the mischievous

pre-teen daughter of another continuing character in the panel, Henry

Tremblechin, who was forever bullied by a blustering bombastic boss named J.P.

Bigdome. The names are perfect for the personalities: Tremblechin, the

intimidated employee; Bigdome, the towering employer (who was originally named

Old Man Grudgeon); Iodine, the lovely little girl with a bratty sting. Hatlo

and Dunn loved Dickensian names for characters—Lushwell, the party boy; I.

Uriah Phootkiss, the unctuous underling; Octave Teargass, a songwriter—not to

mention a picturesque parade that included Twerpington, Wartley, Squatwell,

Culvert, Droolberry, Belfry, and my favorite for a fashionable young woman,

Aspidestra.

Scaduto

drew the Little Iodine strip and her

comic book, when it came along in 1950 (first issue, cover-dated March; last

issue, April 1962). According to Mark Evanier, Dunn did the writing and Scaduto

did most of the drawing; by the time Hatlo died in 1963, his presence had long

ago ceased being felt. Hy Eisman joined the production crew about this time, concentrating on Little Iodine until it ceased in 1986.

(Eisman currently does two other vintage strips, The Katzenjammer Kids and Popeye.) Dunn died in 1989, and Scaduto took over the entire production of

TDIET, writing as well as drawing it. The feature was named Best Newspaper

Panel by the National Cartoonists Society in 1979 and 1992.

To

Scaduto, TDIET was “not a joke strip but a satire on human behavior. It’s the

things that bug us in life. The object of the strip is for people to read it

and say, ‘Hey, that happened to me or someone I know.’ I think that’s why it’s

been so successful.”

Because

many of the situations in TDIET were inspired by reader suggestions, the

temptation is to think that the feature was written by the volunteers. But few

of those ideas are comic without the fine-tuning touch of the cartoonist.

Scaduto streamlined the verbiage, added a comedic verbal twist here and there,

and laminated it into a joke with pictures that turned frustration into

hilarity. In the first example posted here, volunteer Y. Parker may have

supplied the notion that people who place fussy orders for fancy frills with

their food in restaurants then spoil the concoction with condiments, but

Scaduto’s prose added a layer of sarcasm, and the frenzied action and assorted

audience in the setting of the second panel transformed mere sarcasm into

satiric comedy. Scaduto’s love of Dickensian names equaled that of his predecessors’—Judlow Lockjaw, Bula Patoot, Anson Pantz, Ragweed and his wife Nubbia, Drusella and Dragbutt, Bunson, Leadbutt, Naggia, and Wombo, and my favorite recurring name, Lugnut. But his singular achievement as a cartoonist was to modernize the Hatlo-Dunn visual style without destroying its essence. He did this chiefly by eliminating the “hay” that modeled forms in the vintage drawings, but he retained some linear shading for the sake of textural variety, preserving thereby the pictorial “feel” of the feature. He also replaced the Hatlo-Dunn button nose on male characters with a bulbous Parker House roll; and on female characters, in place of their pointy nose, Scaduto drew tiny pert turnips. These larger facial features made the drawings funny even though they were much smaller than the earlier TDIET artwork, and the humorous pictures gave the feature a prevailing vivacity. Instead of being an antique, Scaduto’s TDIET was as modern as the news and fads of the day. In the gallery of examples in this vicinity, the two cartoons on the top are Hatlo’s; those across the bottom are Scaduto’s—for the sake of comparison.