|

|||||||||||

|

NOUS R US Tracy Museum Closes after 17 Years Scott Adams Predicts Outcome of Super Bowl Handelsman Proves Power of Editoons Red Sonja/Sonya Settles Tex Avery’s Anniversary Billy Bunter Is 100 Superman Birthday Bash? Charlie Brown’s Valentine No Longer Magic Simpering Maid Cafes in Japan

PERSEPOLIS THE MOVIE A Review and some Thoughts from Satrapi DANISH DOZEN AGAIN Islamic Hooliganism Threatens Civilization Thugs Arrested in Denmark

BOOK MARQUEE Bates on Bush (Editorial Cartoons) Johnny Hart’s Growing Old with B.C. Pat Oliphant’s Leadership (More Editorial Cartoons) Mort Gerber’s Last Laughs (and an interview with the editor) Nicole Hollander’s Tales of Aging Gracefully (and an interview with the author)

COLLECTORS’ CORNICHE A Glimpse of the Great Zim

COMIC STRIP WATCH The Artistry and Wit of Today’s Funnies Edgy Humor New Comic Strip: It’s All About You by Tony Murphy

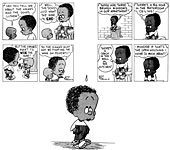

BLACK HISTORY MONTH The Tenth of February Movement and How It Failed—And Then Succeeded Morrie Turner Jackie Ormes Luther

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Reviews of Captain America No. 34 (the Return of American Values) NBM’s Tales from the Crypt Jeff Smith Talks about RASL Warren Ellis’ Prose Novel

EDITOONERY Jim Borgman and Henry Payne Discuss the State of the Art in Their Blogs

PASSIN’ THROUGH Steve Gerber

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this lengthy installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu—

NOUS R US All the News That Gives Us Fits After seventeen years of operation, the Dick Tracy Museum in Woodstock, Illinois, will close in June due to declining attendance. “The museum guest book hasn’t been signed in weeks,” said Carolyn Starks in the Chicago Tribune, “and the shelves are lined with unsold Dick Tracy pens, yellow fedoras and coffee mugs.” Housed in the historic courthouse and jail building overlooking the town square, the Museum attracted more that 6,000 visitors annually during its first years, but last year, only 3,464 visitors dropped in, paying a paltry $2 admission fee, not enough to fund the Museum’s $45,000 budget. The Museum has been operated for several years with donations from the estate of Dick Tracy’s creator, Chester Gould, who lived on his country estate near Woodstock for fifty years. The Museum’s grand opening in 1991 coincided with the debut of the Warren Beatty “Dick Tracy” film, an early screening of which was held in Woodstock’s vintage movie house on Main Street. Subsequently, the city initiated an annual festival, Dick Tracy Days, with a parade, food fare, and games. Participants came attired in yellow fedoras and often wore rubber masks of the classic Tracy villains, Flattop, B-B Eyes, or Pruneface. Dick Locher, who produces Dick Tracy these days, said the closing of the Museum was sad because it stood for an iconic comic strip character, and “comics are an American original.” For the Gould family—Gould’s only child, Jean Gould O’Connell and her son Tracy O’Connell and his wife—the decision to close the Museum was heartbreaking, they said. But they expect to open the facility again online, showcasing the strip, fan letters and some of Gould’s unpublished work. Debuting in October 1931, Dick Tracy, the first realistic procedural cops and robbers comic strip, introduced violence to the funnies pages, and the detective’s cleaver-jaw visage was eventually as well-known worldwide as Mickey Mouse’s ears. He left a reminder in the Chicago area: at the Cantigny Golf Course in Wheaton on the estate of former Tribune owner Colonel Robert R. McCormick, there’s a sand bunker in the distinctive shape of Tracy’s profile. What will become of Locher’s design for a six-foot tall, colorized bronz statue of the character, I dunno. Dilbert’s Scott Adams was among those interviewed for the 19th Scripps Howard Celebrity Super Bowl Poll in which notables are asked to predict the outcome of the game. Adams got the winner right even if he was off on the final score: “Giants 37-21. Eli Manning has more incentive to win because (he’s) trying to make his parents love him more (than) they love his older brother. That’s a bigger incentive than Tom Brady’s desire to win yet another ring and bed yet another supermodel.” ... In the February 10 issue of Parade, the Cartoon Parade of single-panel cartoons took an entire page. And in color. Howard Huge was there, as were a brace of cartoons by the McCoys, Gary and Glenn; and syndicated ’tooner Dan Piraro was present, ditto Dave Coverly. But the Cartoon Parade was back to “normal” the next week: just three cartoons (including Howard), no color. ... The writers did okay in their strike: “For the first time,” Entertainment Weekly reports, “writers who create content for the Web and cell phones will get paid for their services. ... This, ultimately, is what the writers went to war over in the first place.” ... At Ohio State U’s Cartoon Research Library, saith Editor & Publisher, an exhibit of the work of editorial cartoonist Anne Mergen opened February 1 to run until April 11. Mergen (1906-1994) “was the only female editorial cartoonist working for a daily paper when the Miami (Ohio) Daily News hired her in 1933.” Her cartoons also ran in the other Cox newspapers around the country. Editorial cartoonists are rejoicing over an apparent vindication of their box office appeal. Newsday’s web site surpassed the Wall Street Journal’s in number of visitors in the last week of January, and on January 21, the New York Times revealed the reason: Newsday editoonist Walt Handelsman’s “Baby Boomers” animation registered over 12 million hits, enough to propel Newsday’s site to astronomical heights, “convincing evidence,” said one editooning observer, “on why newspapers should keep, or hire, their own editorial cartoonist.” ... Some furious emotion erupted recently over the practice some publishers pursue in selling their new books, graphic novels in particular, at comic conventions in advance of filling the orders for the same titles at direct market comic book shops. Shop owners are upset because the convention floor sales cut into their potential revenue. But publishers claim they run so close to a loss on many titles that the only way they can break into a profit margin is by selling at conventions, in effect pre-empting shop sales. What to do? The legal squabbling over the Robert E. Howard character Red Sonja has ended. According to newsarama.com, “Red Sonja LLC, which owns the rights to Red Sonja—with a ‘j’—had filed a $5 million lawsuit in April 2006 accusing Paradox Entertainment of infringing on its trademark and attempting to create confusion in the marketplace. Paradox, which bought Conan and the entire Howard library in 2006, owns the rights to Red Sonya—with a ‘y.’” The j-Sonja was “created” by writer Roy Thomas and artist Barry Windsor-Smith for use in the Conan comic books, all based upon the muscle-bound Howard sword and sorcery scourge of the Hyborian Age. But Howard’s y-Sonya is a character from one of his stories set in the 16th century, not in the age of Conan. To settle all this mightily confusing situation, Red Sonja LLC paid Paradox a dollar for all rights to y-Sonya, so the company now owns “both” characters. Meanwhile, Paradox paid a dollar to Red Sonja LLC for “exclusive print-publication rights to ‘The Shadow of the Vulture,’ the single Howard short story in which y-Sonya appears.” That settles that. But which Red is the one in the bikini made of dimes? Speaking

of anniversaries this year, as we were last time, I inadvertently

left out the 100th anniversary on February 26 of the birth of Tex

Avery, who invented Daffy Duck and others of

the most wacky on-screen animated personalities. “It’s

appropriate that the feisty fowl would perhaps be the animator’s

most beloved invention,” said U.S. News

& World Report (January 7). “Avery

fought against the realism in animation practiced most notably by

Disney and let the characters go jaw-droppingly crazy instead.”

In short, Avery championed the notion that animated cartoons should

do things that cannot be done in any other genre of motion picture

manufacture. ... And in Britain, some diligent souls are celebrating

the 100th anniversary of the first cartoon appearance of Billy

Bunter, who arrived in the February issue of Magnet comic book.

Billy was the ultimate in unsavory schoolboy behavior: a chubby,

snivelling and deceitful hanger-on in a gang of six, he was

invariably the butt of whatever prank they played. “His

laughable habit,” writes Jim White at telegraph.co.uk, “was

to own up long before anyone accused him of anything.” Called

to the schoolmaster’s office, perhaps to receive a

long-distance phone call from his father, Billy would promptly blurt

out: “If it’s about the cake, sir, it wasn’t me,

sir. I didn’t know Mrs. Keble was even baking a cake, Sir. And

it very definitely isn’t in my desk, Sir, so there’s no

point looking in it.” Entertainment Weekly, mentioning the broadcast of “A Charlie Brown Valentine,” said: “Chuck and the Little Red-Haired Girl were way cuter before we killed the magic and read the Schulz bio.” David Michaelis’ controversial biography is the subject of a “roundtable” review in The Comics Journal No. 290 (May) wherein four of us contemplate the tome: Monte Schulz, the cartoonist’s eldest son who represents the Schulz family’s opinions and criticisms, and comics critics Kent Worcester and Jeet Heer (co-editors of Arguing the Comics, a valuable collection of long-lost essays on comics by “literary masters” like Gilbert Seldes, Robert Warshow, Walter J. Ong, Marshall McLuhan, Gershon Legman, Leslie Fiedler and Umberto Eco; we’ll take a look at it in Opus 219) and Yrs Trly. Judging from the EW note, the Schulz Empire might have grounds for a lawsuit, alleging that the revenue producing potential of the Peanuts franchise has been diminished, particularly if advertisers for the Peanuts tv specials back off because “the magic” has gone off the rose. I’ve lost the source of this next tidbit, but a note in my stack says that anime sales are down in Japan; is manga next? “Manga,” as everyone by now knows, is Japanese for “comics”; but the Japanese also use the word “comics” without compunction. In Japan, we learn via voanews.com (Voice of America) that “otaku” is the term applied to “obsessive fans of comic books and animated cartoons,” and otaku have become an economic force in the country. Anime may be on the decline, but otaku spend more than $2 billion a year on their obsession. “They represent the new recreational majority among young people,” reports VOA’s Catherine Makino in Tokyo. “They’re inspired by comic books, and they seem to have problems watching anything over the length of 15 minutes.” A quarter of a million otakku attend a twice-yearly Comic Market in Tokyo’s Akihabara district, where they line up for hours to get a table at one of the so-called “maid cafes, where waitresses dress in scanty black maid’s outfits with white aprons, black net stockings and lacy white headbands” and greet male customers by saying, “Welcome home, master.”

*****

PERSEPOLIS THE MOVIE, UP FOR AN OSCAR The animated film based upon Marjane Satrapi’s two graphic novels about her childhood in Iran during the last days of the shah and the first years of the theocratic Islamic Republic and her expatriate adolescence in Vienna is up for an Oscar against “Ratatouille” and “Surf’s Up.” I don’t know, as I write this (on Thursday, February 21) whether “Persepolis” won, but it’s collected a bushel of awards so far—among them, the National Board of Review’s Freedom of Expression Award, Krzkysztof Kieslowski Award for best feature film at the 30th Starz Denver Film Festival, and best feature film at Ottawa International Animation Festival. It was named best animated feature by both New York and Los Angeles film critics groups and nominated as best foreign language film at Golden Globes (didn’t win). The film enjoyed a 20-minuted standing ovation at the Cannes Film Festival last year, where it took the Grand Jury prize. You can find a scroll listing all these awards, and perhaps others, plus a couple previews of the film at http://movies.yahoo.com/movie/1809698229/video/500214/. By the way, the name, Persepolis, Satrapi has explained, comes from the Greeks, who gave that name to the ancient capitol of Iran. It means “city of Persians,” she said. The name is a symptom of the author's nonconformist stance, evoking, as it does, the ancient culture of Satrapi's native country by way of reminding her readers that Iran is not synonymous with the hostage-taking of 1979-80 or with the repressive rule of the mullahs since then or with the menace the Bush League sees in the present Iranian government. Whether the film won an Oscar or not—and by the time you read this, you’ll know—it’s a better movie technically than I thought it would be, judging, as I was, from the “preview” the books provide. Satrapi’s graphic novels are simply drawn. Not that they are amateurish at all—indeed, quite the contrary—but they are stylistically bland compared, say, to the spare elegance of Crockett Johnson’s simply rendered comic strip Barnaby (or his Harold books for children, drawn in the same manner). Satrapi’s style in the books is distinguished not so much by its linear qualities—although a Persian flourish sometimes emerges—as by the extensive use of solid blacks. Will Eisner used to say his shadowy Spirit stories were “five bottle” productions, counting the bottles of black ink he emptied on the pages; Satrapi’s books are, by comparison, twenty-bottle books. Otherwise, in the anatomical simplicity of her characters, the books are scarcely noteworthy. The simplicity doubtless made translating her tale into animated form easy, and the result is aesthetically satisfying: stylistically, as far as the characters and figure drawing are concerned, the film is an gratifying echo of the books. And except for a framing sequence in color, the film is all in black and white, just like the books. Unlike the books, it speaks French, with English subtitles (just the thing for a closed caption fanatic like me). The artwork in the books led me to expect limited animation, and the online previews confirmed that expectation, and limited animation is what I saw—but enhanced with numerous nuanced touches, so enhanced that the animation didn’t seem limited at all. An eye blinking at a crucial moment is the sort of thing we expect in limited animation, and we find it here, too. But there are extravagances: when a knot of nuns bends threateningly over young Marj, the crucifixes around their necks move—they dangle. Such refinements are all the more unexpected because neither Satrapi nor her collaborator, another cartoonist, a French friend named Vincent Paronnaud, have much experience at the medium. She had never animated before, and his experience is limited to bits and pieces, only a few minutes in total. Satrapi told Euan Kerr at minnesota.publicradio.org that making the animated “Persepolis” was like jumping into the sea to go 200 miles before actually learning to swim. But they learned to swim by swimming: the latter portions of the film are better than the opening sequences, which made extensive use of silhouettes—mob scenes in solid black, even a chase sequence with running figures all black from head to shoe. Creating the cinematic illusion of motion by using silhouettes is relatively easy to do: you don’t have to draw wrinkles in clothing or other such details, but visually, this is dull stuff. Before I could sink too far into a slough of despond, however, the screen began filling with modernistic cartoony almost ornamental backgrounds, textured in different ways for visual variety. A distinctive Persian embellishment appeared—curlicues and swirling lines. All very dark and black, but decorative, imparting an unexpected depth to the locales against which Satrapi’s simple figures cavorted or slouched, depending upon their mood, and mood is a big part of adolescent angst and teenage romance, the subject of the on-screen Marj’s Vienna adventures. The simple cartoony style permitted a wide range of visual storytelling maneuvers, among them, emotionally-charged exaggeration of physical actions. Marj snorts through her nose at overhearing some of the unkind cuts of her Viennese friends; her mouth opens wide in a teeth-bearing roar at her unfaithful lover; and as Marj develops a womanly figure in puberty, her breasts pop out of her chest—the extreme actions prompt laughter. Satrapi and Paronnaud use an array of gimmicks and devices to offset the otherwise monotonous limited animation. In one flashback sequence, they draw puppets to enact the country’s history under a succession of shahs. Technically, the film is a notable achievement. The story, a variation on the tale in the books (lightly garnished with some of the sexual comedy of Satrapi’s third book, Embroideries, about the feminine wiles of her sex in the patriarchal Iran), I already knew, and it is at least as good on film as in the books; and the film’s ending, particularly exquisite, is better. (For reviews of both Persepolis novels and the mischievous Embroideries, visit Opus 121, then Op. 149, then Op. 171.) Jonathan Messinger at timeout.com notes that Satrapi sees her story as universal—as much about the tribulations of a young woman and crafting identity and sorting out romantic troubles as it is about oppression. That is surely true of her story. But its acceptance and her fame arise from the work’s political posture. Like the graphic novels, the film has provoked an outpouring of enthusiastic reaction among critics and commentators, and Satrapi seems on the move much of the time, fulfilling speaking engagements at college campuses and other prestigious venues. At the Daily Nexus at the University of California - Santa Barbara, Mollie Vandor gushed: “‘Persepolis’—it’s a title that’s been whispered reverently from film geek to film geek, slowing gaining the kind of underground cache that virtually guarantees its eventual migration into the mainstream.” For a cartoonist, this sort of thing marks a huge success. But Satrapi’s triumph is more a factor of timing than of artistic supremacy. Her apparent politic view, inherently a criticism of the Iranian theocracy, panders to American and European attitudes about Iran at the moment, biases formed in this country during the hostage crisis and reinforced with the anti-American utterances by Iran’s subsequent Islamic leadership. After its publication in 2000, the first graphic novel Persepolis sold 300,000 copies in France, a record, according to Inga Pietrusi at cafebabel.com. If the graphic novels hadn’t been critical of Iran—if they had merely told the story of a girl growing up—I doubt that they or the movie would have attracted the attention that has been lavished on the books and the movie and the cartoonist. And Satrapi is perfectly aware of this benefit. Politics not art has nurtured her career. Pietrusi says the first Persepolis, subtitled The Story of a Childhood, is on the syllabus in roughly 250 American universities—including West Point, where it is hoped the book will give the Army’s office corps some understanding of life among the supposed enemy. Official Iran echoes the American view: the film is widely believed to be anti-Iranian, according to tehrantimes.com, “more dangerous than ‘300,’” a film about the Persian king Xerxes. “‘Persepolis’ is potentially more dangerous than productions such as ‘300' because the [Satrapi] film depicts some reality, which has however been mixed up with a large dose of the producers’ fantasies,” said Mahmud Hosseinizad, the program director of the Iranian state-run tv, Channel 3. Satrapi, asked if the film would be shown in Iran, answered with a smile: “Shown? No. Seen? Yes.” Perhaps surprisingly, Satrapi is highly critical of American government, a fierce critic of GeeDubya and of U.S. intervention in Iraq. Pietrusi reports that Satrapi believes that “at the root of conflict, poisoning people’s thoughts and destroying their seemingly peaceful existence, is fanaticism. ‘Today the clash is not so much between East and West, or Islam and Christianity, as between fanatics and normal people,’ [Satrapi says]. Although she isn’t religious, she says: ‘God created this world, and we just complain about the terrible things that fanatics and bombers bring about.’” Judy Stone at San Jose Mercury News said: “Although Satrapi has always been fascinated by all religions, she dislikes the ecclesiastical trappings, which she calls ‘decorations.’ ‘As long as we keep religion on a personal level, it’s great, but in a country like the United States—which is called a secular democracy—when it’s too mixed up with religion, it never has a good result. That is why I’m so scared of George W. Bush. ... Fanaticism is not necessarily religious because secular fanaticism also exists.” Rob Nelson at thephoenix.com reports that Satrapi is a starkly realistic pragmatist. Asked if “war is hell,” Satrapi said: “Yes, and so is lying. If the U.S. military were to say, ‘Okay, look—we’re coming into your region of the world because 85 percent of the oil is in this region, and we’d love to have it. We’re stronger than you, so shut up and just accept that this is the way it is,’ I could accept that, in a way. But when they wrap it in this talk of human rights and democracy, that’s when it becomes too much. Don’t tell me it’s for my own good that you’re here to fuck me over. Don’t insult my intelligence.” About George W. (“Warlord”) Bush’s “Axis of Evil,” Satrapi unloaded to Steve Appleford at lacitybeat.com: “That was copied from the Second World War. [The Axis was Germany, Italy and Japan.] The problem is that when you say that ‘axis’ of something, those people are friends, you know. Iran and Iraq are enemies, and North Korea has nothing to do with us. Creating this Axis of Evil is just nonsense. From an ethical and ideological point of view, if a fanatic in my country calls America ‘the great Satan,’ it’s extremely sad that a big democracy would use the same terminology. A democracy should not use the same weapon as the fanatics. Consider it also from a historical point of view: the people that made the terrorist attack of 9/11—there was no Iranian, no Iraqi, no North Korean between them. They were from Morocco, Pakistan, or Saudi Arabia, and those countries are America’s friends still. I don’t understand that.” She continued: “The image in the media—calling people terrorists, fanatical, etc.—is extremely condescending. It is dangerous when you start calling people from one part of the world terrorists or fanatic, and you reduce them to some abstract notion. If evil has a geographical place, and if the evil has a name, that is the beginning of fascism. That means ‘Let’s go and exterminate all of them, and the good people can live together.’ Real life is not this way. You have fanatics and narrow-minded people everywhere. The stupid man is universal.” The stupid man is, probably, ubiquitous. But Satrapi’s use of the term fascism is debatable. My Cadillac Modern Encyclopedia—“The World of Knowledge Complete in One Volume— defines fascism as “a political system characterized by totalitarianism and a complete rejection of democratic institutions, values, and procedures”—as in Mussolini’s Italy from 1922 to 1943. Satrapi’s use of the term alludes to a dictatorial determination of values, true; but her allusion is fairly imprecise, given the actual meaning of the word, and not altogether applicable here. When a population (like many Americans) starts calling another bunch of people (like radical Muslims) terrorists or fanatics, that’s group think, but it’s not fascism, which it would be if a government told its population who the terrorists and fanatics are. Alas, Satrapi is not alone in using the word in the loosest possible sense. (Sorry, that all just slipped out, nearly unbidden; sermon over.) Satrapi, who is about as far from being a fascist as can be imagined, told Euan Kerr at Minnesota Public Radio’s Morning Edition that she hopes her books and the film will foster better understanding in the West about Iranians. Said she: “If you understand that a guy who is dying is exactly like you, who likes to go to the movies, and eat ice cream and make love to his wife and has a mother and children and hopes, etc.—then it becomes much more difficult [to make war on him]. So if this movie can participate in that fact and say, ‘Hey! It’s just a matter of human beings, no matter where you come from, all of us, we are human, let’s think about that.’ Maybe that will be the right question.” To Lisa Kennedy at the Denver Post, Satrapi added: “What if you consider that the other is not the enemy, not just the ‘Axis of Evil,’ [then] bombing them isn’t as easy. Because you’re not just bombing the Axis of Evil, you’re bombing people that have parents, kids. I feel pretty humble as an artist. I don’t think I can change the world, but if I can help people ask the question, ‘Who are these people? Are they just like us? Are they human beings?’ This is the maximum I ask for. The nicest compliment we got for this movie,” she concluded, “is people saying after ten minutes they forget it’s animation. I have been saying animation isn’t a genre: it’s a medium. Suddenly, it becomes a human story. It becomes your neighbor, your sister, your friend or yourself.” Satrapi explained her choice of medium to Appleford, finishing on an evangelical note: “If we shot this movie with real people in a geographical place with some type of human being, it becomes this story of a Middle Easterner that lives so far from us, they don’t look like us, and so on. There’s something about the abstraction of the drawing—which is the first language of the human being, before writing—something about that anybody can relate to. If you make a drawing or an animation, you don’t really know where it’s happening. We did not want to make an ethnic movie; we wanted to make something universal that anyone can relate to.”

*****

THE DANISH DOZEN ONCE MORE Here We Go Again: Islamic Hooliganism Poised to Rampage The

rot in the state of Denmark continues to fester, but the country’s

vigilant anti-terrorist network has, so far, stymied violent

projects, and journalism flourishes. On February 12, the Danish

Security and Intelligence Service (PET) arrested three men who were

plotting to murder one of the cartoonists who produced the infamous

Danish Dozen in September 2005, and in a gesture to defy fanatical

Islamic intimidation, over a dozen Danish newspapers on February 13

reprinted the cartoonist’s offending cartoon, a drawing of

Muhammad with his turban shaped like a bomb, fuse buring, arguably

for Muslims the most objectionable of the twelve cartoons. Publishing Westergaard’s cartoon again “shows that terror is not only despicable but also at the end powerless,” said the editor of one of the newspapers. Other papers echoed the sentiment, affirming their commitment to freedom of the press. A tabloid, Ekstra Bladet, published all twelve of the cartoons. The conservative broadsheet Berlingske Tidende editorialized: “Freedom of expression gives you the right to think, to speak and to draw what you like ... no matter how many terrorist plots there are,” urging Danish news media “to stand united against fanaticism.” But the president of the Danish Journalists Union, saying, “This is a story that won’t die,” urged cartoonists to “keep a low profile” after the arrests were made on February 12. At least three other European newspapers—in Sweden, the Netherlands, and Spain—reprinted Westergaard’s cartoon in their coverage of the arrest of the trio of terrorists. And so did at least two U.S. newspapers, the Denver Post and the Rocky Mountain News, both published in my new hometown, the holy city of Denver; others around the country presumably did the same, reviving the right they had forfeited two years ago, alleging then that they were simply trying to be “sensitive” to the religious convictions of Muslims, who oppose any depiction of the Prophet for fear it would lead to idolatry. Muslim organizations in Europe generally condemned the three terrorists for plotting murder. The Scotsman’s Kim McLaughlin quoted the spokesman of one group, who said: “No one in Denmark deserves to live in fear.” Another said that even though publishing the cartoons was “like a knife in our hearts,” his group would take no action. Yet another said, “We have decided to neglect and ignore any possible provocation.” But the issue of Islamic sensitivities continues to simmer in Europe, particularly in the Netherlands where, according to AP’s Jan Olsen, “lawmaker Geert Wilders plans to make an anti-Quran film, portraying the religion as fascist and prone to inciting violence against women and homosexuals.” In Denmark, said another AP report, PET has foiled at least two alleged terrorist plots since the cartoon crisis. The February arrest of the would-be cartoonist assassins was essentially preventative: “Investigators believe the plot had not advanced far enough to try the suspects.” Two of the three, both Tunisians, were to be deported; the third, a Danish citizen of Moroccan origin, was released after questioning but may be tried later for violating a Danish terror law. Said Westergaard: “Of course, I fear for my life when the police intelligence service says that some people have concrete plans to kill me. But I have turned fear into anger and resentment.” Recalling his original purpose in drawing the cartoon, he told Slim Allugai of the AFP: “I wanted to show how fanatical Islamists or terrorists use religion as a kind of spiritual weapon. But naturally, I never imagined these kinds of reactions.” Describing himself as an atheist, Westergaard added: “I feel that I am fighting a righteous fight to defend freedom of expression, which is under threat.” Within days, various of the Islamic governments in the Mideast were huffing and puffing in a fine froth of indignant outrage. On February 14, AFP reported that Islamist members of Kuwaiti parliament were calling for “total political and economic boycott of Denmark.” But there was no such restraint the next day in the Gaza Strip where at least 4,000 Hamas supporters rallied to condemn publication of Westergaard’s cartoon. Masked militants blew up the YMCA library, and a virulent spokesman for the Popular Resistance Committees (PRC), Abu Abir, held a news conference and called for the Danish embassies everywhere to be bombed and the ambassadors to be killed. Said he: “We urge [Islamic fighters] to track down those who printed the cartoons, those who drew them, and those who published them, and slaughter them immediately.” In Pakistan, protesters burned a Danish flag in Karachi, but it was a small mob. In Iran, the Danish ambassador was summoned to Teheran to protest the publication of the cartoon. Reuters reported that lawmakers urged President Ahmadinejad to reconsider the country’s relationships with Denmark, and Voice of America News (voanews.com) quoted a letter signed by three quarters of Iran’s legislators that called the publication of the cartoon a “satanic act that desecrates the Islamic religion.” Another statement released by the Majlis National Security and Foreign Policy Commission was virulent, according to presstv.ir: “Unfortunately, once again a Danish paper, which is definitely affiliated to the Zionist criminals, has repeated a past insult.” In Lebanon, the Daily Star fulminated against the Danish press, calling the publication of the cartoon “extremely provocative, utterly outrageous, and malicious in intent.” It was “a deliberate attempt to malign a major religion,” and “no greater abuse of the concept of freedom” could be imagined. The paper demanded an “unconditional apology from the Danish newspapers.” Nowhere in this outburst were the murderous plans of the trio of would-be terrorists mentioned. Back in Denmark, Reuters reported, several hundred Muslims gathered in central Copenhagen on the 15th to protest, shouting “God is great!” as they marched in a more-or-less orderly, but at least not destructive, fashion. Meanwhile, elsewhere in the city, rioting in the streets by immigrant youth continued that night for the sixth night. At first, police could discern no reason for the rampaging and looting, but later, authorities determined that the young hooligans were protesting a new stop-and-search law that permitted police to search people at random for weapons. The rioting may have been fueled by the cartoon’s publication, said BBC News, but the protests began two nights before it was published. Danish Muslims, according to BBC’s religious affairs correspondent Frances Harrison, were “dismayed but determined” to continue “to build bridges,” said one imam. But mistrust, particularly of the news media, is growing. The behavior of the Danish government in its treatment of the three would-be assassins is puzzling to Muslims. “How does it make sense,” asked Imran Hussein who runs an advisory body for Muslim organizations in Denmark, “that a person who is trying to kill somebody is being arrested, charged, interrogated, and then released—and yet still we should feel that he’s a terrorist?” Official explanation for the release—that the trio’s plans had not matured enough to provide evidence for prosecution—didn’t help. It still seems a fraudulent charge. Ironically, only a few weeks before the current disturbance, the Danish Royal Library in Copenhagen announced it was trying to obtain for archival preservation all twelve of the offending cartoons, declaring them to be of “historic value,” according to the Guardian’s Robert Tait. “They have created history in Denmark,” said a spokesman for the library, adding that the drawings would not be publicly displayed but would be treated as rare books: to see them would require getting special permission. A Danish museum, however, is eager to get the cartoons on loan from the library in order to put them in an exhibit about freedom of expression. In England, lately beset by a home-grown brand of Muslim hooliganism—albeit so far (February 22) not suffering from the current spate of outrage at Danish shenanigans— the Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, opined that maybe British law should incorporate parts of Islamic sharia law since, as The Week reported, “there are so many devout Muslims in the country who refuse to recognize British law.” No sharia law that contradicted English law would be permitted, he explained, but his suggestion was immediately scoffed at by others, who pointed out that “Islamic law is supposedly the direct word of God,” which does not lend itself to piecemeal adoption.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in this segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at http://www.rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s www.povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s www.DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s www.comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, http://www.comicsdc.blogspot.com For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s http://www.strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv. The American Dialect Society voted “subprime” the Word of the Year 2007. The Word of the Year is determined in much the same way as Time magazine selects its Person of the Year: it must be a word or phrase that is newly coined to describe or name some fresh phenomenon or it can be an existing word or phrase that has risen to prominence during the year. In 2006, for instance, the Word of the Year was a phrase: to be plutoed, to pluto—meaning, to be demoted or devalued. In 2005, it was truthiness (still my favorite); in 2004, red/blue/purple states; in 2003, metrosexual; and so on through the gamut of popular culture. Surge was one of the runners-up this last year, as was waterboarding. The most creative word of 2007 was googleganger, meaning a person with your name who shows up when you google yourself. The most unnecessary—Happy Kwanhanamas, the latter combining Kwanaz + Hanukka + Christmas. The most outrageous—toe tapper, meaning homosexual. The vote for the Word of the Year was conducted on January 4, 2008, during the annual convention of the ADS. We applaud.

BOOK MARQUEE Bill

Bates is angry at GeeDubya and the Bush League and neither minces

words nor dices pictures about it. Monterey

County Herald’s executive editor

Carolina Garcia became aware of Bates’ cartoons while making

runs to the Carmel Post Office, where Bates regularly posted his

pictorial ponderings about life in Carmel-by-the-Sea on the wall next

to the traditional assortment of “wanted” posters. Bates

had been drawing celebrity portraits, doing weekly cartoons for the Carmel Pine Cone, and

painting signs for Trader Joe’s, and suddenly, he found himself

an editoonist at the Herald. A selection of his incendiary pictures has been published as Bates

on Bush—And a Few of His Lackeys (64

8x5-inch pages in b/w; $9.95 plus $3 s&h from Bates, P.O. Box

4227, Carmel, CA 93821), which includes several cartoons that the Herald editor refused

to publish, such as—two guys having coffee, and when one says,

“Did you hear? Bush had a colonoscopy,” the other

responds: “Yeah, I heard they were looking for his brain.”

Or—the GOP elephant says to Karl Rove, “Our polls are

down, Karl. How can we win in 2008?” and Rove replies: “Just

stick with fear, smear and queer. You can’t miss.” Bates

had to change Rove’s response to “Just stick with guns,

gays, and God,” but, he reports, “They still wouldn’t run it. Political correctness is killing me!”

The cartoons, one to a page, are

*****

Mostly, as you might expect from the book’s title, Johnny Hart’s Growing Old with B.C.: A 50-Year Celebration (196 8x9-inch pages in b/w; Checker, $19.95) is comic strips, three to each generously proportioned page. The book is divided into chapters, one for a short biography of the cartoonist, then one each by decade from the strip’s beginning in 1958, about 30 pages for each chapter except the 1950s and the 2000s, which were less than ten years each. The publication dates of the strips have been scrupulously removed so the value of the book as a historical document is very nearly nil. Its value as an exemplar of the highest comic strip art of which cartooning is capable is, however, immeasurable—exquisite sense of timing yoked to a blend of word and picture that demonstrate the best the medium can do. And there are some gemlike enhancements within. A few pencil sketches of the strip in embryonic state, for instance, and an anecdote or two. As a freelancing gag cartoonist, Hart once exclaimed in exasperation, “Before I am 27 years old, I will have a syndicated strip.” B.C. debuted February 17, 1958, the day before Hart’s 27th birthday. And there are photographs of some of Hart’s friends. When Hart was having trouble creating distinct personalities for his characters, his wife Bobby suggested that he pattern his characters after friends and co-workers; he did, and in one of the book’s sections appear photos of Hart’s inspirations: Peter, Thor, Clumsy Carp, Curls, Wiley, but, for the sake of gender diplomacy, not the Fat Broad or the Cute Chick. (You have to admire Hart’s chutzpah: who, today, would be so colossally incorrect as to have characters named “Fat Broad” and “Cute Chick”?) The volume reprints the very first strip but not any of the others from the first week; for those, you need to re-visit Opus 204, wherein we conduct an appreciation of Hart’s work on the occasion of his death last spring. The Anteater, who was the first member of the cast to attract a following of fans—and who appeared, soon after his introduction, in week after week of the strip—doesn’t appear at all in the 1950s chapter and shows up only a couple times in the 1960s chapter. The human (sic) sapien characters were, at first, chunkier and more triangular, but by the 1960s chapter, they’ve assumed their familiar guises. Each chapter’s title page lists the awards the strip won in that decade; in the 1990s, tellingly, the only award was the Wilbur, given by the Religious Public Relations Council for the 1995 Easter B.C.; none, sadly, in the strip’s last Hart decade. On one of the volume’s earliest pages we are told that the book was in production when Hart died last year. “He designed the cover and made the first edits before he left us,” write his children, Perri and Patti; “our mom said he went over the first draft in bed one night and spent four hours laughing.” Then we get to an introductory page upon which appears Hart’s memorable deployment of a quotation from JFK: “John F. Kennedy said, ‘There are three things which are real—God, human folly, and laughter. The first two are beyond our comprehension, so we must do what we can with the third.’ My name is Johnny Hart. I do what I can with the third.” He did a fabulous lot. It would be hard to pick the best since all of them were so hilarious. But this volume is a handy reminder.

*****

Collections

of Pat Oliphant’s incendiary

hilarities in the form of political cartoons are somewhat rarer these

days than in yore, so when, last year, Andrews McMeel announced the

latest, Leadership: Oliphant Cartoons &

Sculpture from the Bush Years (128

10x7.5-inch pages; paperback, $19.95), I pounced on a copy forthwith.

It, like all its predecessors, is well worth the money and the

perusal time. Oliphant always is. He is the champion of the political

gawfaw, pointed commentary that is also gleefully funny. Usually,

very funny. And very pointed. All without resorting to the usual

symbols and labels. As we can see here with this minuscule sampling

of the book’s contents. An Afterword by Wendy Wick Reaves, Curator of Prints and Drawings at the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian, argues that caricature itself becomes, with an editoonist’s repeated use thereof, the instrument of political comment. A freshly elected President, for instance, begins his editoon life with “funny but minimal” exaggerations. “But, fortunately for the art of satire,” Reaves continues, “each President goes to hell quite quickly in Oliphant’s view, and the caricature evolves. LBJ sags and ages; George H.W. Bush weakens; Carter shrinks; Clinton sweats, Nixon bolts. It is an unforgettable cast of characters.” And in being unforgettable, the images exert their power. “Surely,” Reaves goes on, “Oliphant’s permanent Band-Aid on President Ford’s forehead or the every-present lady’s handbag accompanying Bush Sr. are as influential as tv coverage of a ski slope tumble or journalists’ discussion of the ‘wimp’ factor.” Later, she urges us to “think how subtle the powerful influence” of verbal wit and exaggerated portraits in combination can be: “Of course, we recognize when he is being outrageous ... but humor often disguises the power the cartoonist wields. We do absorb information subconsciously while we laugh.” Despite the fun Oliphant clearly has in lambasting politicians, election years fill him with foreboding. “I hate changes in administrations,” he told John Mark Eberhart at the Kansas City Star last October. “All my villains have been in place, and it takes about six months to establish a new character—or caricature. My early drawings of Bush II almost looked human! But he’s shrunk to Carter size now.” Winner of the Pulitzer and the NCS Reuben, Oliphant values the unfettered freedom of expression that he enjoys as a syndicated-only political cartoonist. Without a home newspaper, he can do pretty much what he wants. And his syndicate, Universal Press, lets him. It is, he said, is “the best syndicate there is,” even if, he added facetiously, one of the honchos is “a cheap bastard.” Unhappily, Oliphant’s client list of newspapers includes many that are, he says, “gutless wonders,” terrified of controversy. Universal Press invariably defends Oliphant’s right to speak his mind, saying, “this is what he does” and declining to rein him in as is usually requested. Eberhart concludes with an apostrophe to the most conspicuous of today’s politicians: “Beware, all who would seek to become the nation’s 44th chief executive. Oliphant, suitably skeptical and cranky, knows the timbre of the next administration before it even begins—and it just makes him smile at the prospect of more work to do. ‘They all turn out to be bums in the end,’ he says.” The Leadership compendium does not include as many of Oliphant’s hardest-hitting cartoons as I remember he produced during the period embraced by the book. But it offers enough to suggest the power of his wit and brush, like his cartoon about Darfur that I’ve reproduced in this vicinity—accompanied by the wholly unrelated but revelatory cartoon with a paragraph of caption that he did when Gerald Ford died in December 2006. After those two, I’ve included a few from 2006 and 2005 that display Oliphant’s comedic ire to advantage, including one of a series he did with GeeDubya as a teensy monarch always accompanied by his malevolent courtier, Darth Cheney. This pairing goes a long way toward establishing a public opinion of the Bush League that Reaves would predict: through repetition, the imagery of an infantile child king and his evil advisor brands both and sears the brand in our memory.

But if this book isn’t as encyclopedic with Oliphant hard-hitters as I might wish, it does come equipped with a few pages of Foreword by P.J. O’Rourke, who claims to be a Republican but who sounds, instead, like he knows whereof he speaks. He says, for example: “Pat [by which he means Pat Oliphant] is all that stands between us and idiocy and jerkdom. Pat takes the raw material of our sin and forges it into seething indignation. As with so much of the manufacturing sector, American no longer produces seething indignation. We’ve had to outsource it to an Aussie wetback.” The Aussie weback would be, of course, Oliphant, who came to this fair land of ours in 1964, fleeing the inhibitions of his editors in the Outback and rejoicing in the liberties he was able to take under the bemused eye of Palmer Hoyt, free-wheeling publisher of the Denver Post, which had just lost its star, Paul Conrad, to the Los Angeles Times. Oliphant quickly made Hoyt and the rest of us dry our tears and take heart. “Pat arrived from Adelaide before Homeland Security had been created to guard our borders against terror,” O’Rourke observes, implying that Oliphant is a terrorist, an inference that most politicians would quickly draw. But Oliphant, we are assured by O’Rourke, is as warm and cuddly as a minuscule penguin. Punk, the minuscule penguin invoked here, was invented while Oliphant was still in Australia. The cartoonist invented him because he needed some device that would permit him to say what he really wanted to say but that his Australian bosses at gutless Down Under newspapers wouldn’t permit him to say. Predicting the weather, Oliphant is wont to say, is about as controversial as his Aussie editors ever wanted to get. So Oliphant invented Punk the Tiny Penguin to make acerbic comments on the goings-on that the cartooner depicts in the expanse of the panel above the penguin. Some people, O’Rourke claims, believe Punk is God. They believe that because whenever Oliphant’s cartoon depicts some really venal malfeasance or horrifying disaster (or “act of God”), Punk is nowhere to be seen. Like God. But Oliphant is there, and he sees.

****

Other Attractions. The Complete Mad Don Martin is out in two volumes, $150. I’ve never quite understood the wacky appeal of Martin’s cartooning, but for those who do, this is the book for them. And for more in a biographical vein, visit Harv’s Hindsight, where we rant on about him. ... The current show at the Cartoon Art Museum of San Francisco, “Sex and Sensibility,” will re-surface in book form in April, picking up a subtitle en route: Ten Women Examine the Lunacy of Love in 200 Cartoons. The show features the work of two Pulitzer-winning editoonists (Signe Wilkinson and Ann Telnaes) and eight magazine cartooners, including the editor, Liza Donnelly, plus Roz Chast, Carolita Johnson, Marisa Acocella Marchetto, Victoria Roberts, Barabara Smaller, Julia Suits, and Kim Warp, mostly of The New Yorker stable. ... I’m intrigued enough by the title to order a copy of David Hajdu’s The Ten-cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How It Changed America (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), which can be found for about fourteen bucks at various book sites (try AddALL.com). The entire series of Scott McCloud’s futuristic comic book Zot!, dubbed “a seminal work that reflects the influence of both manga and the emerging alternative comics scene” by Calvin Reid at PW Comics Week, will be reprinted in black-and-white in a 576-page volume in July by HarperCollins, one of whose associate editors, Hope Innelli, says: “Zot! [which started in 1987] is the origin of Scott’s comics. It’s where he defined his style. We’re so used to Scott explaining comics, but now, we get a chance to experience his comics.” Said McCloud: “The book is ... about the meeting of hope and disillusionment,” and it’s also “about how comics work. Even while I worked on it, I was trying to figure out what makes comics tick. After I finished Zot!, I started to work on Understanding Comics.” Although the early issues of the comic book were in color, McCloud came to believe that he could do more with black and white to explore his subject, character. “Black and white,” he said, “is much more like picture-writing.” In Zot!, he said he created a “neo-mainstream comic from all the ideas that were running through my head—alternative, superhero, manga.”

*****

Growing Old In Print In The Week’s quotations from a book called The Thing About Life Is That One Day You’ll Be Dead by David Shields, we picked up a carload lot of facts about aging, which I’m just now doing. “When you’re a young adult, the reflex that tells you it’s time to urinate occurs when your bladder is half-full. For people over the age of 65, the message isn’t received until your bladder’s nearly full.” That accounts for why, when older people have to go, they gotta go right now. And there’s more: When you’re 60, your brain possesses four times the information that it does at 20, but your ability to retrieve data stored therein is diminished. Victor Hugo said: “Forty is the old age of youth; fifty is the youth of old age.” Says Emerson: “’Tis strange that it is not in vogue to commit hara-kiri, as the Japanese do, at 60. Nature is so insulting in her hints and notices, does not pull you by the sleeve, but pulls out your teeth, tears off your hair in patches, steals your eyesight, twists your face into an ugly mask—in short, puts all contumelies upon you, without in the least abating your zeal to make a good appearance, and all this at the same time that she is molding the new figures around you into wonderful beauty, which, of course, is only making your plight worse.” Although maybe the British poet Henry Reed said it best: “As we get older, we do not get any younger.” Two notable ’tooners have lately resorted to the topic of age in assembling books for your shelf—Mort Gerber and Nicole Hollander. Gerber, who’s been in The New Yorker for over 40 years and has produced something like 40 books of cartoons and related items—his now out-of-print tome, Cartooning: The Art and the Business, is still considered a classic, said Calvin Reid at Publishers Weekly Comics Week. And now, he’s got another book out: Last Laughs: Cartoons about Aging, Retirement and the Great Beyond (208 8x10-inch pages in hardcover; $22.95). For which, Gerber rounded up 26 New Yorker ’tooners “to take a good long look at the big topics—including the Big D—of our senior years,” said Reid. “Turns out, getting older than be pretty funny.” Reid then interviews Gerber, who produced a weekly cartoon about the book business for PW from 1987 to 1994. Here are a few scraps of that interchange:

Mort Gerberg: [laughs] A combination of things. These days people are living longer, and I started to think about the idea of retiring. I love the idea of people just going on and on, living life to the fullest. There are all these older cartoonists like Frank Modell—he's 90—cartoonists that I look up to that I could get stuff from. Also there are a lot of older cartoonists who aren't being used by The New Yorker as much as they used to be—people like Bob Weber, Modell and J.B. Handelsman, who died just before the book came out—great single panel cartoonists. The New Yorker is using more younger cartoonists, but these guys are still brilliant. I was able to sample a lot of points of views on aging, retirement and death from people in their 70s, 40s and 30s, because everyone's got to deal with those issues. ... We put together a book using intelligent, literate, old-fashioned single-panel cartoons. And when I say “old-fashioned,” I mean cartoons with something to say that are also drawn well. I was able to pay well, so I was able to get a lot of original work from guys I've known and published with for 30 or 40 years. PWCW: What makes you think death is so funny? MG: Well, it was on my mind, and it's on other people's minds [laughs]. I've done a lot of cartoons about death. If the book has a message, it's really that death is a part of life, and you don't need to avoid it as a topic for discussion. That's why I asked the cartoonists to draw their own funerals. ... It's amazing how many euphemisms there are—"passed away," "go to the other side." As a society, we refuse to say we are dying. We're marvelously creative at avoiding it, and these cartoons make fun of that. Death is just an aspect of life, and if it's irritating, do a cartoon about it. That's what cartoonists do: draw about stuff that bothers them. ... The book has 132 cartoons. I kept it to a small group of cartoonists so that [they] could all publish several pieces of work. ... I told all the cartoonists what I wanted for the original work. There were a lot of duplications, so I made a bunch of piles and sorted them out—the grim reaper pile, the heaven pile, the hell pile. Then we took a look at how many grim reaper jokes we ought to keep. [My wife] Judith helped a lot. I received hundreds of cartoons on death, aging and retirement. The ones picked for the book kind of all work together. One reason a cartoon works is when there is some surprise. Varying the subject increases the surprise and the humor. PWCW: Any favorites? MG: Frank Modell is great. The New Yorker stopped buying his work, so I really wanted him in the book. But at first he kept telling me he wasn't in the cartoon business anymore. I kept asking, but he just kept refusing. But eventually he asked if Lee Lorenz [longtime New Yorker cartoonist, once the magazine’s cartoon editor] was in the book. I said, yeah. So later I'm in the doctor's office and my cellphone rings. It's Frank. He says, ‘Okay, I've done a few.’ He did 18. We took six right away. I was thrilled. PWCW: The book also includes younger New Yorker cartoonists like Marisa Acocella Marchetto, the author of the comics survivor memoir Cancer Vixen; Kim Warp, Matthew Diffee, and others. What's the state of the gag panel, the single-panel cartoon? It was once a staple editorial feature in glossy consumer magazines. MG: The reality is that there's no place for anyone coming into the business. There's no place for them to learn the craft of cartooning. When I started in 1963-64, there were still a lot of magazines. I was getting $25 a cartoon from the Realist. There were a lot of men's magazines; there was Look, Saturday Evening Post, Esquire and Playboy early on. Finally, in the late 1960s I got a chance to start with The New Yorker, but it took a long time. You had to pay your dues to get in there. Bob Weber, one of the great New Yorker cartoonists, submitted cartoons for a year before he got in—and he didn't even get a rejection note back during that time. Today, there's only The New Yorker and Playboy. I used to sell cartoons to Barron's, PW, even the Harvard Business Review. That was a motivation for doing this book. To gather together in one place a lot of really great cartoons, just like the old New Yorker. I wanted it to be a beautiful collection, a labor of love. PWCW: You close out the book with a section where you ask all the cartoonists a series of questions. The section is very funny, especially when you ask them to draw their own funerals. MG: We wanted to ask a few quirky questions to challenge the cartoonists, and it gives the book another dimension. ... I wrote the questions. A lot of the answers are similar, which is interesting. Some of the cartoonists drew themselves missing their own funerals. One of the questions asked, when you were kid, what did you want to be when you grew up? Me and Bob Weber both said the same thing: taller.

*****

Rapidly approaching dotage, I am, naturally, interested in such treatises as Gerber and company’s and in another cartoonist’s effort, prose without pictures (as nearly as I can tell), from Nicole Hollander, who, when not writing, draws the syndicated strip Sylvia. In her new perhaps scandalous book, Tales of Graceful Aging from the Planet Denial (272 5x7.5-inch pages, hardcover; $19.95), she discusses just about everything concerning women of a certain age. Jill Bauer at the Miami Herald told us about it last October; here’s her report, verbatim: ''If sixty is the new forty, when do I get to be thirty again?'' Hollander asks as she takes us with her on a hilarious, panty-wetting romp through aging. Hollander discusses everything from late-life sex with vibrators (Chapter 8, Return to Lust), to peculiar herbal remedies for menopausal symptoms. We caught up with Hollander, 68, at her home a few hours before her rehearsal at the Chicago Cultural Center where she is staging a reading of her book. Of course, we were most interested in hearing all the juicy details about Hollander's quickie affair with an old flame she hadn't seen in 45 years. Q: How has aging altered your perceptions of sexual attractiveness? A: All the way along, you're getting older and you start noticing that older people don't look at you in a sexual way anymore. Up until my 50s old men were twisting around in their cars to look at me. As a young girl I was never attracted to older men. The last great love of my life (25 years ago) was 11 years younger than me. But I've trained myself to look at men my age. Q: Have you ever been married? A: Yes, I was married once for four years to the teaching assistant in my college sociology class. I think that I felt it was some kind of rite of passage to adulthood and I had no hope for it. Q:Your recent sexcapade with an old flame was riveting— especially since you hadn't had sex in 14 years. Can you elaborate? A: I had written off this part of my life and I was fine with it. But then I got a call from an old boyfriend and the more we talked, the more we turned each other on. We're from the same generation and we're as stupid now as when we were younger. I became amazingly obsessed with this person and I got into Olympic conditioning for him. I called my friend Carol for tips and she said, ``You think I'm having sex? You must be nuts. I'm not having sex. But let me get a cigarette, because if you're having sex, I want to hear about it.'' Q: You write about how you met this old flame (who happens to be married) for a tryst in an unnamed ''Western town.'' What was your initial thought when you got off the plane and saw him? A: I was so excited that I didn't look closely at him and I knew I had to talk fast because I wasn't 6 years old anymore. But I got over that quickly because of the way he made me feel. What happens is that they don't look the same but you remember something very attractive and that's still there. Q: What provoked you to break the rules and go for it with a married former lover? A: He plunked down $9.95 on the Internet to find my address and telephone number. I guess several things went through my mind. I figured I'd better do it now. It's a chance to be bad again. And there's a familiarity there. Q: So, with the buildup and massive preparation, did the sex live up to your expectations? A: I thought it was fabulous and incredibly exciting. In the book I say it was the best sex I've ever had. What would make the best sex of your life? It does probably have to do with how far away the other sex was. Also, it has to do with how much you know. I guess I wasn't really comparing it. It's a real ''in-the-moment'' kind of thing. Q: Did this sexperience stimulate your desire to have a man in your life? A: At first I tried to replace it but I didn't really want to try out a lot of people. I had other things I wanted to do. What are the chances of me connecting with someone again? Well, what are the chances of someone calling me from 45 years ago? Whatever the chance of that is, which is slim to none, is what it would take. But I'm not sad. I'm terrifically grateful. I had no idea in the world this could happen. I felt I'd been reborn.

THE FROTH ESTATE More Cogitations About the So-called News Media Did you know that “in the largest mob sweep in years, federal and New York state authorities recently rounded up more than 80 alleged organized-crime figures, charging them with murder, loan-sharking, extortion, and other crimes”? Or that there is a high-pitched whistle or alarm siren that emits a piercing sound that is painfully annoying to the young but that can’t be heard by most people over 25? British officials are just seeking to ban the device, “which has been in use for two years in stores, schools, and municipal buildings to discourage teenagers from hanging around after hours.” Or that in Okinawa, Japan, a U.S. Marine has been arrested last week on suspicion of raping a 14-year-old girl? Or that troop reduction in Iraq will cease, temporarily, after about 30,000 of the present force (the size of the “surge,” in other words) is sent back home in August? Further cuts are not on the table at the moment, Defense Secretary Robert Gates said. And as he said it, the country was experiencing “a marked increase in attacks on the Sunni ‘awakening’ militias that have been working with the U.S.” No? Never heard of any of this? All of these fugitive events were reported in the February 22 issue of The Week. But they receive little notice on the tv news media—or anywhere else, for that matter—because of the obsessive reporting on the Presidential contest. Every night, no matter which channel you tune in to, you’ll hear Hillary and Obama and McCain say, again, what they’ve been reported, again and again, as saying, again and again and again. As if there is no other news worthy of reporting.

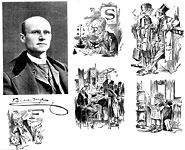

COLLECTORS’ CORNICHE Welcome to our sentimental section where I muse and marvel about antique volumes on the shelf and rare finds in old bookstores and the like. Nothing major. Skip over this if you’re busy. Here is a smattering of drawings by the great “Zim,” Eugene Zimmerman, whose career started in the late 1800s, drawing, mostly, for the humor magazine, Judge. Zim was one of the first cartoonists in the magazines of the time to produce exaggerative, caricatures of human anatomy—big foot style, the first “authentic” cartoon drawing, you might say. These pictures are taken from the pages of one of humorist Bill Nye’s books, which Zim illustrated, caricaturing Nye as he did.

COMIC STRIP WATCH You’d think, what with all the ceaseless din in the news media about primaries and caucuses, that we have enough political coverage without any help from the comics. Not so. Once a verboten topic in the funnies, politics now crops up when we least expect it. In Darrin Bell’s Candorville, for instance, Lemont Brown has figured out what Obama needs to do if he wins the nomination: “If he wins, you just know thousands of bigots are going bullet shopping. So he’s gotta pick a vice president that bigots’ll hate worse—someone the bigots wouldn’t want to risk becoming president. Obviously, his running mate should be an illegal immigrant.” Obviously, we need this kind of political commentary. It’s refreshingly straight-forward. And since we can’t find it anywhere else but in the funnies, that’s where we should look for it. In Non Sequitur, Wiley faces the issue of corporate control enforcing a conservative bias throughout their radio chains when Joe Pyle’s station changes from “news talk” to “classical polka.” Joe wonders if the change will mean he’s lost his job, but his manager assures him that the station will still need a news director and hands him a copy of the new guidelines. Joe reads it, then asks: “And if I won’t lead the news with spin on how tax cuts for the rich lead to a booming economy?” he asks. His manager clears it up for him: “Then good luck finding a new job in this recession.” In another episode of the same strip, a character manifests alarm when she learns that the primary elections will eventually produce a new President. “You mean this is real?” she gasps. Until just then, she’d thought “it was anotha stupid game show by the netwahks to covah the writah’s strike.” (This is the character with the deep fried Southern accent, which accounts for the spelling anomalies here.) “The tip-off,” her auditor tells her, “is that the game shows are more believable.” Another category of once taboo subjects includes overt reference to bodily functions or sexual activity. This taboo, too, is falling away. In Mike Peters’ Mother Goose and Grimm, Grimm notices the cat licking itself in one of the places cats often lick themselves (just under the tail) and says: “You eat your dinner with that mouth?” And in Over the Hedge, written by Michael Fry and drawn by T [no punctuation] Lewis, Hammy the nutty squirrel goes off-camera to urinate discreetly behind a tree (“tinkle, tinkle, tinkle” we hear), but in the last panel, we are permitted to see behind the tree where Hammy has pee-written “family” in the snow. On another occasion, Hammy emerges from the outhouse, where he’s done his duty, and R.J. the raccoon says, “Ahh—Dude! Someone light a match,” a reference—dare I say?—to post-evacuation fragrance, an emission of methane gas, which, as every adolescent knows, is highly combustible. In Rudy Parks, drawn by Darrin Bell over Theron Heir’s scripts, a female character uses the word “nooky” in reference to a possible sexual encounter. Heir appears to have a fondness for the word, although when he used it some months ago, he spelled it “nookie.” If you are at all intrigued by all this edginess in the funnies, you might be interested in my column Comicopia in the current issue of The Comics Journal (No. 288, February, 2008), wherein I belabor the subject even more, wavering to and fro on the question of whether they are or aren’t edgier than ever. On the other hand, much of that column’s content is culled from our very own Rancid Raves herewith, so maybe you could skip it. On yet another hand, the Journal’s lists of “The Best Comics of 2007,” provided by an array of columnists and commentators, is provocative and might be worth your while. Strips continue to display an admirable skill with words as well as pictures. In Jim Kemsley’s Ginger Meggs, a “runner up” is defined as “a polite way of saying you lost.” In Jimmy Johnson’s Arlo and Janis, Arlo delivers a cup of tea to his wife, who is soaking in a bathtub, bubbles heaped up to her chin, and when she wonders why Arlo is still hanging around after giving her the cup of tea, he says: “I’m waiting for the surfactants to weaken and natural surface tension to re-establish itself.” She says: “The bubbles to pop?” He says: “I never could fool you.” They’ve been married forever but hot desire still raises its throbbing head every so often. Verbal dexterity includes word play of all kinds. When Dagwood comes home one day and tells the eponymous Blondie that his boss has given him a bonus, handing her the money, she says: “This is confederate money!” And Dagwood responds: “You ain’t just whistlin’ Dixie.” (Is it my imagination, or is Blondie lately wittier than of yore?) In Brian Basset’s Adam, the title character takes his car to the shop, saying the vehicle is making “a funky percussion-like sound” and then imitates the sound: “Rat-a-tap-tap rat-a-tap-tap... (continuing for several more rat-a-taps). The service manager tells him the problem with the car is “break drums.” In Darby Conley’s Get Fuzzy, Rob, commenting on Satchel’s getting into a fight, says: “You put the ‘fist’ in ‘pacifist,’ my friend.” To which Satchel, quite sensibly, says: “Well, better that than the ‘paci,’ I guess.” A few days later, when the hapless mutt manages to get the toilet to overflow and flood the apartment, he explains to Rob that the guilty appliance “over-performed.” In Richard Thompson’s Cul de Sac, little Alice spreads cheer by drawing a happy face on a rock “and then releasing it into the wild for everyone to enjoy.” She says she’s drawn happy faces on “maybe ten million” little rocks. “I hope that soon they’ll cover the earth in a vast army of tiny, cute cheerful rocks.” Later, at home, her father finds a rock in his shoe that’s laughing at him. Alice applauds: “You must have happy feet.” In Get Fuzzy again, when Rob accuses Bucky Kat of having bad grammar, the vicious feline snaps back: “Lemme tell ya something, Webster. Grammar am for people who can’t think for myself. Understand me?” So bad grammar is a sign of independent thinking, thinking out-of-the-box? Works for me. In Baldo by Hector Cantu and Carlos Castellanos, the teenage protagonist is asked at school to name the parts of speech and responds: “The mouth, the tongue, the lips and sometimes the arms,” adding: “My uncle Felipe waves them all over when he talks.” Can’t argue with that. In Mike Baldwin’s single-panel cartoon, Cornered, a character shopping in the super market stops at the bottled water section to read a new sign: “Frozen Water Concentrate.” Think about it. The most consistently thought-provoking strip is Jef Mallett’s Frazz, the adventures of a hip janitor among the precocious pupils in an elementary school. On the first of February, one of the kids wonders why February is always shortened “at the end.” He continues: “Why not stick with 30 days, but start it on the 2nd or the 3rd?” Frazz says: “I like it but I don’t know why.” The kid then offers a revelation: “The first day of every month is when I’m supposed to clean my room.” A few days earlier, another kid disproves global warming by visiting an art museum and observing that in the older paintings, the people have fewer clothes—hence, obviously, it was warmer back then. Frazz says that scares him. The kid says: “Because old paintings of semi-naked people are insufficient data? Well, people have formed stronger convictions on less data,” he finishes. “Bingo,” says Frazz. The next day, the kid realizes that “scantily clad people in old paintings may not be a reliable measure of yesterday’s climate. And even if it is, it needs to be compared to more current data.” Frazz decodes for us: “Uh-huh. And the Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue comes out when?” “Any day now,” says the kid, “—I’ve had the librarian put a hold on it.” It’s a long train of thought, but, happily, it stays on track for the whole run. Conundrums (or is it “conundra”?) heap up in Frazz. Talking to Frazz over lunch, a kid looks at his packaged dessert and exclaims: “Whoa! Check out the ‘sell by’ date on my Pudding Pal. If something takes that long to go bad, how long does it take to digest?” To which Frazz quite sensibly says: “Oh, my.” And the kid goes on: “If I have a little burst of energy in junior high, we’ll know where it came from.” I

can’t let wriggle loose without comment that reference to the

bathing beauty issue of Sports Illustrated, this year’s edition of which being on the stands as I assemble

this Opus of R&R. A few pearls of wisdom eke out of strips every now and then, too. In Zits by Jerry Scott and Jim Borgman, Jeremy, having committed some sort of juvenile sin in the name of adolescent infatuation, moans: “God shouldn’t serve hormones to minors.” And, back at Cornered, one of two drunks lounging in an alley says: “It seems like small is the new big, 50 is the new 40, and drunk is the new sober.” With logic like that, he should run for office. But,

as I always say, comics are more about pictures than about words.

Well, not quite: what I always say is that the best comics are those

in which words and pictures blend to create a meaning neither conveys

alone without the other. But the medium is still a visual one, so

pictures play a dominant role. A succession of pictures “times”

the action, for example, and we have a superbly inventive instance of

timing at hand in Greg Evans’ Luann when Brad,

discussing his unrequited love life with his roommate, opens the door

and we see the subject of their discussion, the beauteous Toni,

standing just outside, fist poised to knock. The “timing”

of the strip as a whole leads to that last panel, but it, itself, is

another example of timing, the visual information “timed”

as we “read” the panel from left to right. Sweet. Sometimes,

the pictures are just funny—which is what they should be. And

then we have a clutch of strips doing odd things. First among

them—always when oddity is at hand—is Bill

Griffith’s Zippy, in which the pinheads display interest in

comic books (and Wally Wood)

and Griffith ponders the future of newspapers (as are we all). A few

days later, Zippy awakens in a “rustic dell” to find he’s

been transformed into a satyr, which makes him feel, he says, “kind

of ... satirical.” Can’t say I saw that one coming, but I

should have. Scott Adams’ Dilbert, while funny

on its own, gains in hilarity once we recall the real life incident

in which an

Finally, here’s Darrin Bell again. Not content with pissing off editors by criticizing their racial tokenism on February 10 (about which, more in a trice), he lunges at them again in Candorville on February 11 and keeps it up for another three days, taking shots at them for their benighted hide-bound inability to see what is obvious to even a casual observer: comic strips, an image-laden feature unique to newspapers, should be actively deployed in any effort to attract readers in an image-ridden age; instead, editors work deliberately to undermine this feature, reducing the size and number of comic strips in their papers. Bell isn’t telling a story here: he’s reporting facts. Just a few weeks ago, the Houston Chronicle, which had been offering more comic strips than any other major newspaper, reduced the number of pages devoted to the funnies. And other papers are doing the same in a startling display of paralyzing stupidity. In New Jersey, E&P reports, the Star-Ledger on February 17 dropped its Sunday funnies from 8 to 6 pages. But it lost only one of the 39 strips it had been running in eight pages. To achieve this miracle, it was necessary to shrink the size of the strips drastically: Prince Valiant, reports Dave Astor, is “almost unreadable.” It’s absolutely blinding to have to work in the glare of so many dim bulbs, as I’m wont to say on such occasions. Bell

finishes his diatribe by assaulting editors’ penchant to

perpetuate legacy strips, which may appeal to

*****

New Comic Strip. It’s All About You is the name of a new comic strip by Tony Murphy, launched December 31 through Washington Post Writer’s Group. The “You” in the title is probably Michael, “a caffeine-craving neurotic”who is “in a long-term pre-marriage relationship with his well-balanced, herbal-tea-drinking girlfriend, Gina. I think maybe they’re living together but I can’t say for sure, and Murphy isn’t talking. “Michael,” says Amy Lago, WPWG’s comics editor, “epitomizes today’s mentality. We’re obsessed with how we appear to the rest of the world yet desperate to win acceptance strictly by being ourselves.” Michael and Gina spend a lot of time at a local coffee shop, where they encounter friends and talk. The strip is mostly talk, a lot of it. The multi-panel medium is deployed here only to time the talk: pictures contribute almost nothing to the narrative except to identify the speakers. That is not the absolute best use of the form: in the best examples, as I always say, words and pictures blend, each contributing something to the “meaning” of the strip, a meaning neither can achieve alone without the other. (There: I’ve said it again.) The blend here tells us who is talking. Useful, even vital, but not the same as Calvin and Hobbes. The strip had a pre-syndicate life: it ran for two years in free metro papers in Boston and New York. Murphy’s drawing style renders human anatomy in lumps: the pictures remind me of oatmeal that’s been sitting around for a day, but it’s a friendly style, sticking to you while you get used to it, and Murphy spots blacks smartly, giving his images a pleasant variety. His principal characters are habitually bug-eyed which imparts to their facial expressions a glazed look as if they are going through the motions of following the latest fads but aren’t entirely committed or don’t know quite why they’re doing it. Their appearance fits their situation, though, and their situation is usually funny in a quirky way.

*****