|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 255 (February 3, 2010). The bargain-priced DVD of all of Playboy for its first decade, 1953-1959, prompted us to re-visit the magazine and the cartoonists who made it home during that formative ten years—Jack Cole, of course, but also the unknown (or at least unheralded) Draber—and so we spent an inordinate amount number of sentences marking first appearances and other innovations ushered into the modern era by founding publisher Hugh M. Hefner. We also celebrate the centennial of the Boy Scouts of America by digging up the cartoons and illustrations of one of its founders, Dan Beard; and ponder the myopia of a New Yorker profile of Neil Gaiman. And (trying to make up for our dereliction lately) we review a dozen new funnybooks, all listed below. Yes, I know we were going to do Osamu Tezuka this time; but the Playboy bargain just sucked up all the space—that and the surprise interview with Bill Watterson. Next time, Osamu Tezuka. This time, here’s what’s here, in order, by department: Watterson Interview NOUS R US Amazon’s Top Ten Comics and Graphic Novels Women in Comics Week Twilight Graphic Novel Preview Avatar’s Box Office Record How Many Have Died in the Funnies? Neil Gaiman in The New Yorker P. Craig Russell on The Dream Hunter Alan Moore’s New Magazine Feiffer’s Memoir HAPPY BIRTHDAY Boy Scouts of America: 100 Years Old Dan Beard, Founder and Cartoonist EDITOONERY Good Ones This Week Airport Security BOOK MARQUEE New Books Now Available BOOK REVIEWS Two Bargains: The Completely Mad Don Martin and Playboy Cover to Cover, 1950s Early Playboy Content and Its Cartoons 1953-1959 FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Dominick Fortune, 1-4 Archie Nuptial Saga, 603-605 Stumptown, 2 The Last Resort, 1-5 28 Days Later Glamourpuss, 10 FIRST ISSUES: Daytripper Cowboy Ninja Viking Nomad: Girl Without a World Greek Street The Eternal Conflicts of the Cosmic Warrior Black Widow: Deadly Origin And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go— NO REGRETS: WATTERSON’S FIRST INTERVIEW IN 15 (OR SO) YEARS Fresh newly crafted Calvin and Hobbes comic strips haven’t been in the newspaper for fourteen years. During that time, the strip’s creator, Bill Watterson, has been absent from the public prints, refusing to be interviewed or photographed. But Watterson grew up in Chagrin Falls and still makes Greater Cleveland his home, and he presumably has some residual affection, even loyalty, to the local paper, the Plain Dealer. Whatever the reason, Watterson recently answered some questions via e-mail from reporter John Campanelli. It's believed to be the first interview with the reclusive artist since 1989, apart from some exchanges in connection with the publication of The Complete Calvin and Hobbes in 2005; the following was published February 1, 2010. Q. With almost 15 years of separation and reflection, what do you think it was about Calvin and Hobbes that went beyond just capturing readers' attention, but their hearts as well? A. The only part I understand is what went into the creation of the strip. What readers take away from it is up to them. Once the strip is published, readers bring their own experiences to it, and the work takes on a life of its own. Everyone responds differently to different parts. I just tried to write honestly, and I tried to make this little world fun to look at, so people would take the time to read it. That was the full extent of my concern. You mix a bunch of ingredients, and once in a great while, chemistry happens. I can't explain why the strip caught on the way it did, and I don't think I could ever duplicate it. A lot of things have to go right all at once. Q. What are your thoughts about the legacy of your strip? A. Well, it's not a subject that keeps me up at night. Readers will always decide if the work is meaningful and relevant to them, and I can live with whatever conclusion they come to. Again, my part in all this largely ended as the ink dried. Q. Readers became friends with your characters, so understandably, they grieved—and are still grieving—when the strip ended. What would you like to tell them? A. This isn't as hard to understand as people try to make it. By the end of 10 years, I'd said pretty much everything I had come there to say. It's always better to leave the party early. If I had rolled along with the strip's popularity and repeated myself for another five, 10 or 20 years, the people now "grieving" for Calvin and Hobbes would be wishing me dead and cursing newspapers for running tedious, ancient strips like mine instead of acquiring fresher, livelier talent. And I'd be agreeing with them. I think some of the reason Calvin and Hobbes still finds an audience today is because I chose not to run the wheels off it. I've never regretted stopping when I did. Q. Because your work touched so many people, fans feel a connection to you, like they know you. They want more of your work, more Calvin, another strip, anything. It really is a sort of rock star/fan relationship. Because of your aversion to attention, how do you deal with that even today? And how do you deal with knowing that it's going to follow you for the rest of your days? A. Ah, the life of a newspaper cartoonist— how I miss the groupies, drugs and trashed hotel rooms! But since my "rock star" days, the public attention has faded a lot. In Pop Culture Time, the 1990s were eons ago. There are occasional flare-ups of weirdness, but mostly I just go about my quiet life and do my best to ignore the rest. I'm proud of the strip, enormously grateful for its success, and truly flattered that people still read it, but I wrote Calvin and Hobbes in my 30s, and I'm many miles from there. An artwork can stay frozen in time, but I stumble through the years like everyone else. I think the deeper fans understand that, and are willing to give me some room to go on with my life. Q. How soon after the U.S. Postal Service issues the Calvin stamp will you send a letter with one on the envelope? A. Immediately. I'm going to get in my horse and buggy and snail-mail a check for my newspaper subscription. Q. How do you want people to remember that 6-year-old and his tiger? A. I vote for "Calvin and Hobbes, Eighth Wonder of the World." For more about Watterson, including a link to samples of the editorial cartoons he drew for the Sun Newspapers, go here: cleveland.com/living/index.ssf/2010/02/bill_watterson_creator_of_belo.html ***** Reporter Campanelli, a comics enthusiast and former college cartoonist, scored his interview with the J.D. Salinger of cartooning without ruse. He’d started out thinking he would review Nevin Martell’s recent book, Looking for Calvin and Hobbes. “Instead of doing an article on the book,” Campanelli told Michael Cavna at Washington Post’s Comic Riffs blog, “I wanted to use the book— and the announcement of the [Calvin and Hobbes] postage stamp and the 15th anniversary of the retirement of the strip—as hooks for a wider-look article on the timelessness and enduring nature of the strip itself." To that purpose, he e-mailed Watterson a list of questions, but he was well aware of Watterson’s reputation as a recluse, so he wasn’t very hopeful of a response. “To my complete amazement,” Campanelli said, “—he responded. I've never had contact with him before.” He has no idea why Watterson chose to speak at this time, but he did so without imposing any limits or conditions. “When he sent his answers, Watterson mentioned that he trusted his words would be used in context and that the questions behind them would be clear. That's it.” Asked if there was any one thing about Watterson's responses that most surprised or intrigued him, Campanelli said: “You mean, besides that he answered them at all? I'd say what most intrigued me was his frank insight and, of course, his humor. And that he has never regretted leaving the comics pages when he did. Amazing.” NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits Until this year, the National Cartoonists Society judged graphic novels with comic books in the same category division of NCS’s annual Reuben awards. But this year, for the first time, NCS recognizes that the graphic novel is a separate, and different, genre of cartooning than the comic book. It’s about time. ... Last summer, Ruben Boling’s weekly altie strip, Tom the Dancing Bug (which doesn’t seem to be about a dancing bug—or anyone called “Tom”), won the Association of Alternate Newsweeklies’ award for Best Cartoon. A live-action comedy featuring one of the strip’s characters, Harvey Richards, Lawyer for Children, is in development at New Line Cinema. In Amsterdam, popular lawmaker Geert Wilders failed on January 13 to get a judge to reduce or drop charges against him for his 2008 short film “Fitna,” which offended many Muslims by juxtaposing Koranic verses with images of terrorism by Islamic hoodlums. Wilders is scheduled to go on trial in March for “insulting Muslims as a group and inciting hatred and discrimination against them”; Wilders argued that his anti-Islam message is protected as freedom of speech, but he lost this preliminary bout. Amazon.com listed the top ten “editor’s picks and customer favorite” comics and

graphic novels for 2009, in order, we assume, of popularity: Stitches, George Sprott,

Asterios Polyp, All-Star Superman, the Umbrella Academy: Dallas, Locas II, The

Photographer, A Drifting Life, The [Illustrated] Book of Genesis, and Masterpiece

Comics. ... Kim Thompson at Fantagraphics tells me that my magnum opus, Meanwhile: A Biography of Milton Caniff, Creator of Terry and the Pirates and Steve

Canyon, is nearly sold out: only about 400 of the initial press run of 3,500 still remain in

the publisher’s warehouse. And I have a few left here, too, safely ensconced in the

Rancid Raves Book Grotto and Gallery below; more about the book here. ... Both the McCoys, Gary and Glenn, had a cartoon in Parade’s “Cartoon Parade” January 10.

Can you tell the difference in styles? ***** “Women in Comics” week is coming, March 21-17, inspired, doubtless, by the prospect of selling more comics while also nodding ceremoniously to “the women who work in the industry and create the comics and the women who star in the comics we read each month” (Previews). The magazine’s “brand manager” Jim Meyer interviewed Gail Simone, who has lately hove into view writing the adventures of Wonder Woman, “the most iconic woman in comics,” who is also one of the most problematic. It has never been quite decided, for once and all, whether Wonder Woman (aka Diana Prince) should be a sexy superheroine or a feminist icon. Herewith a few out-takes from the Simone interview, published in the January Previews. On Wonder Woman: “Greg Rucka, one of the best Wonder Woman writers of the modern age, has said that the problem with Wonder Woman was that she was fragmented each time a new writer came on and abandoned everything the previous writers had done. I agree, so my goal was to present a human Diana, someone who had some wit and charm and an inner life, but also someone who was cohesive. ... Mainly, I wanted to ditch the idea of an arrogant speechifying aristocrat: that’s never felt like Diana to me. “ On being a woman in the comic book biz: “I love being a woman. I love being a woman who writes. But being a ‘woman writer’ is not nearly as important to me. ... Each year that goes by, I feel a little bit less like an oddity. The industry welcomed me; pros I had worshiped when I was little were incredibly kind and supportive. And now I look out and see Ivory Madison and Kathryn Immonen and Nicola Scott and so many other fierce women of impact and talent, and it all feels like a road we’re walking that’s headed somewhere wonderful. I walked it because Colleen Doran and Jill Thompson walked it for me, after Ramona Fradon and Marie Severin paved the way. People don’t buy Nicola Scott-drawn books because she’s female; they buy them because she draws like a damn bandit. ... Every interview Dwayne McDuffie [an African American comics writer] is asked about blacks in comics, when what the audience cares about is that he’s a brilliant writer. Really, what is wanted is not ‘more Asian creators.’ What is wanted is a wide range of voices, and the best available talent.” ***** Passing Through. Several notable toilers in the vineyards of popular culture left us in the last month. Erich Segal made us all weep with the novel and then the movie “Love Story” about a young college man and his wife, who dies of cancer soon after they marry; Segal died January 17 at the age of 72. Robert B. Parker, who wrote more than 50 novels, 37 of them about a Boston private eye named just Spenser, no other name, died at 77. Movie actress Jean Simmons, whose career flourished in the 1950s and 1960s in such films as “Guys and Dolls” and “Elmer Gantry” and “Spartacus,” died at 80. The “other Lone Ranger,” John Hart, the actor who took over after Clayton Moore left the tv masked man in 1952, died at 91. Hart also played Jack Armstrong in the 1947 Columbia serial of that name, based upon the radio program of the late 1930s and 1940s. French cartoonist Jacques Martin, creator of the popular comic book hero Alix and Herge’s collaborator for 19 years on the Tintin books, died at 88. And Jerome David Salinger, who wanted to be the “catcher in the rye” and caught, with his book by that name, the anti-phoney spirit of an age—specifically, teenage—died at 91, no better known to us on the day of his death than he’d been for most of his obsessively reclusive life. He was, in fact, “as famous for being a non-publishing recluse as for anything he had written,” observed Mike Littwin in the Denver Post. Some students of modern life, Littwin goes on, believe that The Catcher in the Rye would not impact today’s teenagers as much as it did before Facebook: “Holden’s self-involved take on the world is hardly radical anymore when kids self-publish every self-involved thought” in their heads on the Web. “One writer makes the case that ‘teenager’ is now less a time of life than it is a consumer demographic.” Perhaps. Although adolescent self-involvement as a manifestation of “I’m the center of the universe” is still a fairly wide-spread affliction, I’d say, so Holden Caulfield is probably still relevant. Salinger kept writing, they say, but stopped publishing; perhaps, now that he has been removed from any possibility of unwanted public adoration and acclaim, his children, or his agent, will be able to publish what he’s written all these years since he stopped publishing in 1965. GRAPHIC NOVEL PREVIEW The January 29 issue of Entertainment Weekly (the issue with a discombobulated Jay Leno on the cover) published eight pages of the 72-page Twilight Graphic Novel as a special preview of manhwa artist Young Kim’s adaptation of Stephenie Meyer’s prose novel, due for a March 16 release. With this kind of publicity, “it is no surprise,” notes ICv2, “that Twilight’s publisher, Yen Press, has set a mammoth 350,000 first print run” for the book. In an interview with EW’s Tina Jordan, author Meyer said she was pleased with Kim’s work: “Reading her version brought me back to the feeling I had when I was writing and it was just me and the characters again. I love that. I thank her for it.” Kim depicts young people as far too beautiful for my taste—and they’re all beautiful, not an ordinary-looking person in the lot. And the book perpetuates the annoying practice of printing speech balloons as semi-transparent bubbles through which we can see people and backgrounds. But I suppose Twilight fans will be ecstatic. Or moribund, if that’s their pleasure. Kim based her adaptation on Meyer’s novel not on the movie. Said Meyer: “It was important to us both that this novel be an interpretation of the novel rather than a cartoon version of the movie. Young took her inspiration direction from the descriptions in the novel, and as a result, the images are much closer to the characters I see in my head than any actual human being could be.” Meyer approved all the art, requesting only minor adjustments—the way a character’s hair was rendered, for instance. “I also asked for the cars to be changed to exactly the models that I’d described,” she said, admitting “no one cares about that besides me.” Meyer said she’s not working on any new Twight-based project at the moment; “but there’s still a possibility that I’ll go back and close some of the open doors” some day in the future. IN MOTION At the Denver Post, Lisa Kennedy said about “The Book of Eli”: “The Hughes brothers have given audiences a graphic-novel flick, but there’s no comic-book series out there on which it’s based. They enlisted comic-book artists to help hone the look, a mix of sharp duns and grays. And writer Gary Whitta, who has done most of his work in videogames and comic books, has crafted a script nearly as methodical and deliberate as its hero [played by Denzel Washington].” Used to be—remember?—when a film critic likened a movie to a comic book, it wasn’t a compliment. Walt Disney Pictures has started shooting Edgar Rice Burroughs’ “John Carter of Mars” in London; it will star Taylor Kitsch and Lynn Collins; ICv2 prints a leggy picture of Collins next to its announcement. Neither Tobey Maguire nor director Sam Raimi will be involved in “Spider-Man

4,” which, saith the Associated Press, will focus on Peter Parker in high school. The

change in personnel is occasioned, some said, by “creative differences” about the

future of the franchise. Jerome Maida at the Philadelphia News recorded some

reactions: "I actually think it's a good idea," said local writer/artist J.S. Earls (Pistolfist). "It's all about communication and if you keep telling stories with the same actors and

directors, it's more difficult to communicate with your audience effectively." Said writer Brandon Jerwa ("Battlestar Galactica"): "Personally, I wish Sony would go with the

more mature Peter Parker, employed as a teacher and juggling a couple of girlfriends,

Mary Jane and the Black Cat, maybe? They'll never go that route, but Neil Patrick

Harris would be my pick if they did. I don't necessarily think anyone should freak out

over the reboot, but I'm definitely a little nervous about how this will play out. Ultimately,

I blame Jay Leno." ***** On January 24, ICv2.com tried to come to grips with the box office phenomenon of “Avatar”: “‘Avatar’ is the first film since [John Cameron’s other film] ‘Titanic’ to top the box office for six consecutive weekends. Overseas the film has now earned $1.288 billion, eclipsing ‘Titanic’s’ 13-year-old international box office record of $1.242 billion. Of course adjusted for ticket price inflation, ‘Titanic’s’ total would be in the neighborhood of $1.66 billion. Meanwhile ‘Avatar’s’ domestic total has swelled to nearly $553 million eclipsing ‘The Dark Knight’ and within easy range of ‘Titanic’s’ record total of $600.7 million.” A few short but profitable days later, “Avatar” surpassed “Titanic’s” record. “Still,” ICv2 went on, “to put ‘Avatar’s’ considerable financial achievements in perspective, in spite of its record-setting performance, Cameron’s 3D outer space saga has still sold fewer tickets than ‘Home Alone,’ ‘Forrest Gump,’ and the first Spider-Man film.” Entertainment Weekly bent over even more in trying to put “Avatar” in its place. Adjusting for ticket-price inflation, “Avatar” plummets to 34th place in the top-earners list, “just a few notches above ‘Pinocchio.’” By this measure, “Gone with the Wind” is still at the top of the heap, followed by: ‘Star Wars,’ ‘The Sound of Music,’ ‘E.T.,’ ‘The Ten Commandments,’ ‘Titanic,’ ‘Jaws,’ ‘Doctor Zhivago,’ ‘The Exorcist,’ and ‘Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.’ The Pope, meanwhile, is not happy with “Avatar”: the Vatican newspaper faults the movie for flirting with the idea that nature worship can replace religion, “a notion the Pope has warned against,” reported the Associated Press. Ross Douthat at the New York Times sees “Avatar” as a “long apologia for pantheism—a faith that equates God with Nature and calls humanity into religious communion with the natural world.” Not a bad idea, said Gus di Zerega at Beliefnet.com: the movie’s message is that “completeness is achieved in connection with others, that harmony is the basic value and its loss the basic failing of the modern mentality.” What this world needs is more pantheists, di Zerega says, and fewer religious fanatics and “narcissistic armchair warriors eager to see others fight in endless wars.” ***** When filmmaker Oren Peli moved into a new house with his girlfriend, they heard noises during the night. “It started me thinking about setting up a video camera and letting it run while you’re asleep,” Peli told Walter Scott at Parade. “How scary would it be to go through the footage afterwards and see something happening that shouldn’t be happening?” And that’s how “Paranormal Activity” was made. It cost $15,000 to produce and has earned, as of January 10 or so, about $100 million. DEATH IN THE FUNNIES When Lisa Moore, a character in Tom Batiuk’s Funky Winkerbean, died of breast cancer in the fall of 2007, it was a major sensation and inspired countless accolades in the news media about how mature (i.e., serious) the funnies had become. Batiuk’s motive was, at first, simple: he wanted to grow as a writer by dealing with disturbing human situations; and he hoped the story, for which he, a cancer survivor himself, did a lot of research, would help people who either have cancer or who have friends or relatives with cancer. Presumably, Batiuk was successful in both his objectives: he demonstrated great skill—sensitivity and understanding as well as mastery of his medium—in handling the Lisa story, and the American Cancer society named the cartoonist to its Cancer Care Hall of Fame. Lisa, however, was not the only comic strip character to die in the history of the comics. Sam Fulwood III, reporting at the Cleveland Plain Dealer, Batiuk’s hometown newspaper, identified at least ten other comic strip characters who died. The first were in George Storm’s Phil Hardy in 1925: several supporting players were killed off during a mutiny. Comics historian Bill Blackbeard gave these deaths historic significance, saying the presence of death in comic strips made adventure continuity strips possible: if a character could die, that ramped up the reality in adventuring to a life-threatening levels. Then in The Gumps, Mary Gold, who was poised to marry another character, fell ill and, after a long illness, died, precipitating an avalanche of protest mail to creator Sidney Smith’s syndicate at the Chicago Tribune. Daddy Warbucks died twice in Harold Gray’s Little Orphan Annie. After his first death, in May 1937 of knife and bullet wounds, reader protest was so clamorous that Gray brought him back to life. But he bumped him off again in 1944 as a protest against the policies of Franklin D. Roosevelt, whose New Deal offended Gray’s conservative sensibilities to such an extent that he decreed that the self-made millionaire Warbucks couldn’t live in FDR’s world. A few months after Roosevelt died in 1945, Gray brought Warbucks back from the grave again. Warbucks explained his reappearance to Annie by saying that “the climate here has changed since I went away.” In the fall of 1941, Milton Caniff famously killed off his plain Jane character, Raven Sherman, having the villain of the moment in Terry and the Pirates shove her off the back of a speeding truck. She lingered for the next 11 days and finally died in the arms of the man who loved her, Dude Hennick. Caniff’s wife had given Raven her name, and the cartoonist joked that Mrs. Caniff never forgave him for killing off “her little girl.” Caniff had killed another supporting character, Old Pop Scott, on January 17, 1935, during the strip’s inaugural episode, mostly to demonstrate that death can happen in a comic strip: no character can be presumed immortal. Andy Lippincott, a gay character in Doonesbury, died of AIDS in 1990, raising awareness of the disease and sympathy for its sufferers. Lippincott is the only fictitious person to have a patch on the national AIDS quilt. Garry Trudeau has killed off other characters—congresswoman Lacey Davenport and her bird-watching husband, Dick, and fat-cat businessman Phil Slackmeyer. And in For Better or For Worse, Lynn Johnston killed the family dog, Farley. Dogs don’t live forever, and Johnston, who has taken great pains to make her strip as realistic as possible, knew the Old English Sheepdog would eventually have to expire, like all family pets do. She arranged a heroic departure: Farley died after saving a child from drowning in 1995. Thanks to Rancid Raves Correspondent Ed Black for the newspaper clipping detailing most of the foregoing. ICON IN BLACK In The New Yorker for January 25, Neil Gaiman is the subject of a profile entitled “Kid Goth” by Dana Goodyear, who, while remarking Gaiman’s extraordinary popularity with certain crowds of young people, misses the secret of his appeal. She fails to see that she has encapsulated the secret when she says: “Gaiman is forty-nine and English, with a pale face and a wild, corkscrewed mop of black-and-gray hair.” She fails to see the Gaiman mystique even when a full-page photograph of him appears on the page facing her description. Sex appeal, that’s the secret. Not talent, not wit. Just sex. Oh, and the all black costuming he affects. Gaiman, Goodyear explains, “is unusually prolific. In addition to horror, he writes fantasy, fairy tales, science fiction, and apocalyptic romps, in the form of novels, comics, picture books, short stories, poems, and screenplays. Now and then, he writes a song. Gaiman's books are genre pieces that refuse to remain true to their genres, and his audience is broader than any purist's: he defines his readership as ‘bipeds.’ His mode is syncretic, with sources ranging from English folktales to glam rock and the Midrash, and enchantment is his major theme: life as we know it, only prone to visitations by Norse gods, trolls, Arthurian knights, and kindergarten-age zombies.” If he could draw cartoons, it sounds like he might be today’s Shel Silverstein. But mostly, he writes. Not, however, without some trepidation. Says he: "There's always that fear of writing too much if you're a reasonably facile writer, and I'm a reasonably facile writer." Gaiman has a good opinion of himself, and not without justification. When the New York Times waited for months after its publication to review his latest book, The Graveyard Book, it didn’t matter. Sales burgeoned apace notwithstanding. "I have at this point a critic-proof career," Gaiman said. "The fans already knew about the book.” Writes Goodyear: “He attributes his recent No. 1 débuts to his ability to communicate directly with his fans: he tells them to buy a book on a certain day, and they do. ‘It means I'm nobody's bitch,’ he told me. Through his blog and Twitter, readers have a seemingly transparent window into his process. ... To his readers, Gaiman projects an image that is at once iconic author-hero and cozy bookworm. ‘At the age of four, I was bit by a radioactive awesome,’ he'll say, by way of the origin story that comics fans are conditioned to expect. Sartorially, he is remarkably like Dream, who is one of his best-loved characters and the protagonist of a monthly series called The Sandman, which he wrote for DC Comics between 1988 and 1996. He wears black: black socks, black jeans, black T-shirts, black boots, and black jackets whose pockets are loaded with small black notebooks and pots of fountain-pen ink in shades like raven. “‘Of course, he wants to become a character,’ says Stephin Merritt, who is the lead singer of the Magnetic Fields and a friend of Gaiman. ‘He's not Salvador Dali, but he's not far off. There's no hard line between his persona and his private life.’ Jon Levin, Gaiman's film agent, says he recognized his client's popularity only when he took him to a meeting at Warner Bros. and all the secretaries got up from their desks to ask for autographs. Someone said, ‘That never happens when Tom Cruise is here.’ “Everywhere Gaiman goes, he encounters women dressed as Death, Dream's sister in Sandman: black clothing, elaborate black eye makeup, and, often, an ankh charm around the neck. (Internet critics deride Gaiman's fans as ‘Twee ‘Bisexual’ Goth Girls with BPD’—borderline personality disorder—‘who are drama majors and who are destined to become cat ladies.’)” Karen Berger, his editor at DC, says: “You look around a room where Neil is, and half the fans are women, if not more.” Still Goodyear doesn’t seem to get it. “Now that he is widely read,” Goodyear says, “he is apt to publish even the most

ephemeral of his offerings, often between hard covers and with lavish illustrations. Last

spring, he released ‘Blueberry Girl,’ a bit of doggerel written for his friend Tori Amos

when she was expecting her first child. (‘Help her to help herself, help her to stand, /

help her to lose and to find. / Teach her we're only as big as our dreams. / Show her

that fortune is blind.’) It spent five weeks on the best-seller list for children's picture books.” Gaiman writes page-turners: you read on, expecting something to happen. But it seldom does. He has ideas for what he might call “stories”—concepts—but they have little or no narrative propellent. The idea doesn’t go anywhere: it just lays there, radiating allusion to Norse folklore and Shakespearean lyrics. The characters (and the readers) marinate in a broth of tingly suggestion without ever acting. They feel but they don’t think. Once, Goodyear reports, Gaiman “happened to see a shooting star. Watching it fall, he says, ‘I just did that thing where you're following a chain of thought, and you go, That looked like it was really near. What if I went and it wasn't a meteorite but it was actually like a big diamond or something? Wouldn't that be cool? And I thought, What if it was a person? And then suddenly it was like a little chain of dominoes.’ He went to Charles Vess, the artist who had illustrated the award-winning issue of Sandman, and told him the idea. That became Stardust, a nineteenth-century-style fairy tale that was first a four-part miniseries for [the Berger-edited] Vertigo imprint, with illustrations by Vess, and then a novel for William Morrow, and finally—after the model Claudia Schiffer read it and implored her husband, the director Matthew Vaughn, to make it—a movie starring Claire Danes and Michelle Pfeiffer.” I don’t know about the chain of dominoes—except for the chain that led to the novel and then the movie. But the chain that allegedly proceeds from the moment of “cool” inspiration—the chain that is the story, the narrative—I haven’t encountered, having not read Stardust, and so I can say nothing about it. But stories rooted in the supernatural have always seemed to me entirely too frothy: because the writer can evade any and all necessity to create portraits of real people, real humans with limitations as well as potentialities, his stories do not much engage me. Neil Gaiman is a big success, no question. But his stories, the few in the original Sandman series that I read, were mere page-turners: they got me going, but by the time I’d reached the end, I realized I was nowhere. Consider, for example, the first issue of P. Craig Russell’s adaptation of Gaiman’s novella The Sandman: The Dream Hunter, which appeared a little over a year ago. In the inaugural issue of this tale, a young monk in Japan lives alone among his devotions in a remote temple. He is observed by a badger and a fox who make a wager that whichever one of them can drive the monk from his temple will inherit the edifice as a home. Being magical, the animals assume other forms to frighten the monk—a hideous demon with his entourage, a beautiful young woman. The hoaxes don’t work because the monk sees through them. In the meantime, the fox has fallen in love with the monk, and when she overhears a plot to kill him, she gives up her most treasured possession to find out how to save him. As a first issue, book satisfies all of the usual criteria (see below under “First Issues”). It contains a central episode—an event with a beginning, a middle and a resolution of the conflict prompted by the beginning—namely, the monk’s successful matching wits with his foes, the badger and the fox. We come to care about the monk because he is witty and clever and a model of integrity. And the end of the issue, we are left in suspense about his fate, but the fox’s maneuvering promises some sort of solution. And maybe in a subsequent issue, we’ll see the Sandman, who makes no appearance herein. Despite its embodiment of the elements that make a satisfying first issue, The Dream Hunter doesn’t much engage me as a narrative. The monk’s problems are created by something alien to normal human experience—the magical machinations of the fox and the badger. So I cannot identify with the monk’s dilemma. And the monk’s means of escaping his predicament—seeing that one of the badger’s demons has the tail of a badger and guessing from that evidence that the being threatening him is not a demon but an badger—are likewise akin to magic. The monk is observant and clever, and I admire those qualities. But he is applying his skill to a wholly unrealistic problem, one I cannot identify with. And that is the glitch I can’t get around in any tale involving the supernatural and why, for me, Gaiman’s stories are just so much warm milk foam, page-turners without the means of absorbing the reader (i.e., me). But Russell’s pictures are something else. As far as I’m concerned, the pictures

are the story. Almost. They are all there is in the story that excites my interest. Russell’s

drawings are elegant, exquisite—and appropriately tinged Asian. As for Gaiman, Goodyear’s profile, apart from her curious myopia (as noted), is informative about the life and lifestyle of this erstwhile comics phenom and worth a read. And if it were more about Gaiman’s comics and less about his persona, it would represent a significant step in cartooning’s march to respectability and artistic status. The New Yorker! But I’m left with a puzzle: Gaiman, Johnny Cash, Alan Moore, Bob Dylan—why do all these guys dress all in black all the time? What is there about black? Funerals? A death wish? “Oh, poor little me—I’m doomed.” And aren’t we all? ANOTHER ICON IN BLACK HEARD FROM Alan “Watchmen” Moore is now producing a new bimonthly magazine called Dodgem Logic, which, says Jessica Holland at thenational.com, combines “psychedelic cartoons, whimsical confessions, political satire and recipes. Subtitled ‘Colliding Ideas To See What Happens,’ the 40-page pamphlet has the look and feel of such 1970s magazines as Oz and the International Times, with the same mixture of radical ideas, frankness and fervor. Dodgem Logic opens with a six-page article dedicated to a history of underground self-publishing, which stretches way past the usual 1970s punk fanzines, beginning with handwritten tracts ‘handed between plague carts’ in the 13th century. (Moore describes them as ‘very much like Twitter only with more leprosy and maggots.’)” The magazine, says Moore, is neither “global” nor “local”: he calls it “lobal.” The artlessness of Dodgem Logic is its charm, says Holland: “The entire magazine looks as though it was put together by students during the early days of desktop publishing: each page is designed differently from the rest and it's easy to spot a few misspellings.” She continues: “Although Moore has become known as the patron saint of graphic novels, this is not the first time his career has veered in an idiosyncratic direction. Ever since he first got kicked out of school for dealing LSD as a teenager, the writer has had a knack for doing what's least expected. Starting out as a young cartoonist for the music paper NME and local papers in the 1970s, he moved on to writing scripts for the comic-book publishing houses Marvel, 2000AD and Warrior. Since then he has written for scores of comics: reworking familiar characters from superhero characters as psychologically complex and sometimes allegorical entities, and creating new ones to express his ideas on everything from politics to the nature of time. On the way, he has blazed a trail for independent thinking (and downright stubbornness) that has made him almost as many enemies as fans.” Revered in some quarters for scorning Hollywood versions of his graphic novels, Moore said in an interview last year: “It is as if we are freshly hatched birds, looking up with our mouths open waiting for Hollywood to feed us more regurgitated worms. The Watchmen film sounds like more regurgitated worms. I for one am sick of worms." Holland goes on: “His truculence and deliberate awkwardness became part of his outlaw appeal: Moore was lampooned in an episode of ‘The Simpsons’ in 2007, where he admitted turning Bart's favorite character, Radioactive Man, into a ‘heroin-addicted jazz critic who's not radioactive.’ (Bart just shrugs and says cheerily: ‘I don't read the words; I just like when he punches people.’) Now 56, Moore shows no signs of slowing up or toeing the line. In Dodgem Logic’s tongue-in-cheek foreword, he says, while lamenting the planet's current financial, political and ecological climate, ‘Clearly, what the world needs is a trippy-looking underground mag with a self-confessed agenda of aggressive randomness. Then everything will be all right.’ And he signs off with a characteristic mixture of hubris and humor: ‘Alan Moore, 80s icon and the boss of you.’” Moore’s newest title is 25,000 Years of Erotic Literature; I haven’t see it yet, but it purports to be a fully illustrated essay contending that society’s that permit pornography to thrive tend to be advanced societies; those that don’t, are autocratic dictatorships. An interesting and provocative proposition, however fanciful it may prove to be. ***** Feiffer’s Memoir. Jules Feiffer’s long awaited autobiography, Backing into Forward (termed a “Memoir”), is among the books you can order in the January Previews, which means it is in a bookstore near you—or will be soon. “Brimming with wry punchlines,” it sez here, “slices of Americana, and pithy social commentary, Backing into Forward charts Feiffer’s rise to fame from unlikely beginnings.” Meanwhile, after half-a-century, Feiffer is back with his one-time collaborator, Norton Juster: the two are working on a new book, The Odious Ogre, for Michael di Capua Books at Scholastic. Their previous effort together was The Phantom Tollbooth, which came out in 1961; since then it has sold 3.3 million copies. Feiffer and Juster met while taking out the garbage: they lived in the same apartment building—Juster in the basement; Feiffer on the third floor. When the landlady ended their leases so she could renovate, the two took up residence in a nearby “seedy duplex.” Juster paced the floor as he conjured up a story. On the floor below, Feiffer could hear him walking around: annoyed by the noise, he came up to see what Juster was writing. Said Juster: “Then he drew sketches to go with the story. They were unbelievably good.” Juster wrote two more books, reported Sue Corbett at Publishers Weekly, but, trained as an architect, he devoted most of his energy to designing buildings for the next thirty years. Feiffer also turned away from children’s books for most of his career: “I started the weekly comic strip [in the Village Voice], trying to overthrow the government,” he quipped. But he also wrote novels, plays, and, particularly in the last few years, children’s books again. Di Capua longed to bring the duo together again, but he thought Juster’s most recent books were too “sweet” for Feiffer’s scratchy artwork and urbane sensibility. “But this story about the ogre is extremely witty and has a certain black humor to it,” di Capua said. The ogre, for instance, has an impressive vocabulary, “due mainly to having inadvertently swallowed a large dictionary while consuming the head librarian in one of the nearby towns. I knew dead certain Jules was going to want to illustrate it,” di Capua said. He was right. Now nearly finished with the artwork, Corbett continued, Feiffer reports he’s had a blast. “The one thing I will say is that, in relation to the other characters, he is possibly the biggest ogre in captivity,” Feiffer said. “He was great fun to draw, though—more fun for me than for the ogre.” Di Capua finds an echo of Feiffer’s Village Voice comic strip in The Ogre: though the ogre is “extraordinarily large, exceedingly ugly, unusually angry, constantly hungry, and absolutely merciless,” the girl he encounters, working in her cottage garden, is unfazed by his brutishness. “She’s another manifestation of Jules’s dancer,” di Capua said. Only, somehow, she’s better. “Not that I’m knocking his earlier work,” he added, “but there’s a certain freedom that’s noticeably on a higher level. You can tell he’s having a great time.” Right again, Feiffer said, who did the illustrations in pen and ink brush with colored markers, gouache “and anything else I could think of. It’s my new way of working, which I love.” In fact, he and Juster are already planning their next joint maneuver, he says.ThePhantom Ogre, or maybe The Odious Tollboothcoming in 2060. Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, comicsdc.blogspot.com and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon. MOTS & QUOTES “One of the big problems with comics is that they are too blunt: melodrama is the default mode of comics.” —Jeet Heer in an interview with Tom Spurgeon at comicsreporter.com “My heart was gladdened by an official-looking sign in the Milwaukee airport just beyond the TSA checkpoint, hanging over where you put your shoes and coat back on. The sign said: ‘Recombobulation Area.’ The English language gains a new word. Recombobulate, America.”—Garrison Keillor Denver’s major, John Hickenlooper, a trained geologist and onetime bar owner, announced his candidacy for governor recently by urging a progressive posture: “What’s ultimately the opposite of woe?” he asked. And then he answered: “Well, it’s giddyap. And right now, it’s truly giddyap time in Colorado.” Woe and whoa, right? Ha. HAPPY BIRTHDAY The Boy Scouts of America celebrates its 100th anniversary on February 8. As a boy, I

served time in the Cub Scouts and, subsequently—starting at the age of twelve—in the

Boy Scouts. Troop 63 in the Holy City of Edgewater, Colorado. Before that, though, I’d

spent hours pouring over the Scout manual, Handbook for Boys, the 1930 revision of

the original 1910 tome having found its way into my father’s library. By the time of that

edition, almost five million of the books had been published. It was a paperback

volume, but the cover was flexible, not stiff, so the book fit your hand like a glove not

like a board. I lost the copy I grew up with, but I’ve since obtained another of the same

vintage, with a cover illustration by Norman Rockwell, the unofficial official illustrator of

the Boy Scouts. The origin of the BSA is rehearsed in Chapter IV: The “Good Turn” and Knighthood: “Early in the fifth century, there rode through the forest, in what is now a corner of London, a powerful Knight, clad in full shining armor, with lance and plumes and helmet. Like his master, the great war horse was also protected by armored trappings. At his side rode his Squire, a young knight in traning, and behind came his picked patrol of men-at-arms—strong, brave, armed to the teeth. A gallant band, alert and ready. “The shrill scream of a woman in trouble startled the band. Instantly, the Knight turned aside, and spurring his charger into a full gallop, was soon at the woman’s side. One stroke of his trusty sword disposed of her captor, while his men quickly overtook and handled the other bandits. Then the frightened woman was restored to her fireside—and the Knight traveled on. Such was the spirit of these Knights of old. A ‘Good Turn’ to some one was their daily practice. “1,500 years rolled by and over that selfsame one-time forest, the great city of London has grown. All day long it had been in the hard grip of a dense, heavy fog. Traffic crept cautiously and slowly. Street lights had been ordered on by the police before noon, and now night was coming on. Danger lurked on every hand because ‘going’ was difficult even for the native. “William D. Boyce, Chicago publisher and traveler, was seeking a difficult address in old London. A boy approached him and asked, ‘May I be of service to you?’ Mr. Boyce told him where he wanted to go and the boy saluted and said, ‘Come with me, sir,’ and forthwith led him to the desired spot. Like the typical American tourist, Mr. Boyce reached in his pocket and offered the boy a shilling. The boy promptly replied, ‘No, sir, I am a Scout. Scouts do not accept tips for courtesies.’ The man in surprise murmured, ‘What do you say?’ The Scout repeated and then added, ‘Don’t you know about the Scouts?’ Mr. Boyce said, ‘Tell me about them.’ The boy did and added, ‘Their office is very near, sir. I’ll be glad to show you the way.’ “Mr. Boyce had to complete his errand first. The lad waited, however, and then led him to the office of Sir Robert Baden-Powell, founder of the British Boy Scout Association, where information about the Scout Movement was gladly given. Mr. Boyce was tremendously impressed and gathering all available information, brought it back to the United States. On February 8 the next year, Mr. Boyce and others interested in boys and citizenship formally incorporated the Boy Scouts of America. This day is observed each year as the birthday of Scouting in the United States. This ‘Good Turn’ to a stranger brought Scouting to millions of American boys.” Knighthood in flower, damsels in distress, good turns in “heavy dense London fog”—what boy wouldn’t be enchanted with this tale, most of which, obviously, is claptrap, pure window-dressing designed to raise Boyce’s chance encounter in “old London” to the level of myth and legend. To that, the American founders added Native American woodlore and the resourcefulness of pioneers. Irresistible. Boyce, by the way, was not just a “Chicago publisher”: he was one of the inventors of newspaper syndication. He sold to small town and rural newspapers printing plates or sheets of newsprint printed on one side with national or regional news; small papers then filled the unprinted sides of the newsprint with local news. The Handbook, having regaled us with the story of old London’s “Unknown Scout” (as Boyce’s savior is known in BSA lore), continues: “The final test of a good Scout is in his doing of ‘Daily Good Turns’ quietly and without boasting. “A ‘Good Turn,’” it advised, “is an extra kindness and service—something more than what courtesy and good manners would do.” And the Handbook even helpfully listed Some Modern Good Turns: put out a forest fire, let a dog out of a trap, carry mail to a prisoner, wheel a crippled man, move a sewer pipe out of the road, get a ball out of a tree for a boy, help a grocer recover spilled fruit. The list goes on for two pages, doubtless sending uncounted legions of Scouts off looking for forest fires to put out, trapped dogs, balls snared in trees, and stray sewer pipes. We can laugh today at the primitive naivety of this catalogue of kindnesses, but the book was in its 49th printing by 1930. What intrigued me, however—at an earlier age than I needed to be to join up—was not the text in the book but the pictures. Every one of its 5x7-inch pages carried several illustrations, spot drawings and diagrams. Some of the former I’ve collected in this vicinity.

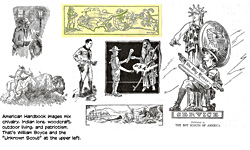

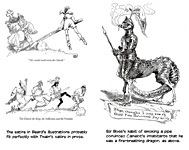

Most of the drawings were reproduced at diminutive dimensions, just the right size for small boy eyes. I was enchanted, particularly by the full-page illustration of the “trail” of Scouting advancement, which we’ve posted in this batch. Baden-Powell, a British army officer, hero of the Siege of Mafeking in South Africa during the Boer War, served in India and Afghanistan also and, based upon his practical experiences, wrote handbooks for adult army scouts and later adapted his teachings to a younger audience in the belief that physical fitness and intellectual attainments among the nation’s youth would insure a long life for the British empire. I picked up a copy of the Oxford University Press 2004 reprint of the original 1908 text of Baden-Powell’s Scouting for Boys and, skimming the table of contents, was intrigued by an appendix entitled “Continence.” “Incontinence” these days usually refers to a failure of the blader or bowels, so I wondered what Baden-Powell might have to say about its opposite. I turned to page 351 and found an essay on the evils of masturbation that Baden-Powell had drafted under the heading “Avoid Self-Abuse” but had been persuaded to leave out of the book. I can see why: it’s a genuinely horrifying treatise. Baden-Powell addresses his young readers directly: “I have told you of the dangers of drink and of smoking which, if indulged in boys, are certain to make you unhealthy in the end and therefore useless as a scout. ... But there is another practice which is perhaps more dangerous. ... The practice is called ‘self-abuse.’ And the result of self-abuse is always—mind you, always—that the boy after a time becomes weak and nervous and shy, he gets headaches and probably palpitation of the heart, and if he still carries it on too far he very often goes out of his mind and becomes an idiot. A very large number of the lunatics in our asylums have made themselves ill by indulging in this vice although at one time they were sensible cheery boys like any one of you. The use of your parts is not to play with when you are a boy but to enable you to get children when you are grown up and married. But if you misuse them while young you will not be able to use them when you are a man: they will not work then.” You can understand why in this country boys at the age of 12 were ushered into Scouting: at that age, you were poised on the precipice of adolescence, so the parental presumption was that if you got preoccupied with woodcraft, you wouldn’t notice woody when it showed up. Willliam Boyce of foggy London fame was not the only advocate in favor of scouting for boys in the U.S. In fact, he was rather a johnny-come-lately. Daniel Carter Beard had preceded him by several years. Trained as a civil engineer and surveyor, Beard abandoned that profession early. Influenced, no doubt, by his father’s being a celebrated portrait artist, Beard took up drawing, and when the family moved to New York in 1878 from northern Kentucky, where young Dan had developed a love for nature and outdoors living, Beard began studying at the Art Student’s League, and, at the age of 32, sold an illustrated article, “How to Camp Without a Tent,” to St. Nicholas, a magazine for young people. That same year, he wrote and illustrated What To Do and How To Do It: The American Boy’s Handy Book. The illustrations attracted attention, and in 1889 Beard illustrated Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. Some of his drawings (as you’ll see in a trice), inspired by Twain’s satire, achieving the potency of political cartooning. And in some of the pictures, Beard went beyond Twain’s satire, caricaturing leading political and business figures of the day with whom Beard disagreed. Beard’s illustration commissions fell off quite sharply thereafter. In 1905, Beard became editor of the wildlife magazine Recreation and formed Sons of Daniel Boone, an organization for boys that promoted conservation and outdoor living; due to its affiliation with the magazine, it also promoted circulation. A year later, Beard went to work at another magazine, Women’s Home Companion, leaving it in 1908 for the Pictorial Review, where, once again, he formed a youth group affiliated with the magazine, the Boy Pioneers. The Boy Pioneers was among several boys’ organizations that were consolidated into the Boy Scouts, and Beard was a charter member of the executive committee. He was also one of the editors of Boys’ Life, the BSA magazine, for which he wrote a popular column as “Uncle Dan.” Later, he helped his sister organize the Camp Fire Girls. Apart from my youthful involvement in Boy Scouts, my interest in Beard is prompted by the appearance of his drawings, as cartoons, in the old humor magazine Life. Here is one of the latter and some of his illustrations for Twain’s satirical novel.

The other principal in the formation of the American Boy Scouts was Ernest Thompson Seton, whose passion for the traditions of Native American life prompted him to form boys clubs to practice those ways of living in the out-of-doors. His book, The Birch-Bark Roll of the Woodcraft Indians, inspired the formation of Woodcraft tribes all around the country, starting in about 1902. Seton was an artist—he made his fortune drawing detailed pictures of birds and animals in the wild—and he had met Beard while both were studying at the Art Students League in New York. But Seton, as far as I know, never drew cartoons, so I’m slighting him in this history. Sorry. Maybe another time. Baden-Powell was also an accomplished artist; many of the illustrations in Scouting for Boys are his (perhaps even the two I’ve reproduced above). His drawing ability was useful when he was scouting enemy positions. He once famously said he’d drawn a schematic of an enemy fortification within a sketch of a butterfly wing so if he were captured he would not be revealed as a spy.

EDITOONERY Afflicting the Comfortable and Comforting the Afflicted

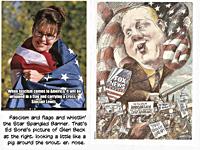

In our harvest of good editoons for the week, Mike Peters’ visual punning over the Jay-Conan affair seemed the most accurate and pungent (pun unintended but savored) on that topic, and the pun also suggested just how frivolous a distraction this episode might have become had there been no other news that week. David Fitzsimmons’ stark imagery of the Haitian tragedy— giving credit to rescue operations while also, with the clutching hand of supplication, expressing a searing sympathy for those caught in the debris of the collapsing country—moved the pile of rubble away from being the simple visual cliche so many other cartoonists had resorted to. Mike Keefe, beneath Fitzsimmons in our visual aid, supplies a persuasive image denying the logic of the Supreme Court’s decision to let corporate cash represent speech, a ruling that reverses previous Court decisions and upends a host of laws that go back more than 100 years to when Teddy Roosevelt was chasing after robber barons. If that isn’t a prime example of an activist judiciary, I dunno what better instance we could find. And at the upper right, Tom Toles adroitly deploys a popular culture metaphor to puncture the GOP’s political strategy. Funny and pointed at the same time. Below that we have Brian Fairrington’s telling image reporting the results of the Massachusetts special election. Fairrington leans to the right, so it’s easy to understand his jubilation when Scott Brown, a Republican, was elected to the U.S. Senate to fill out the rest of Teddy Kennedy’s term, all that was left of a nearly half-century of continuous Democrat incumbency. Brown’s arrival in the Senate marks the first time since 1972 that the Congressional delegation from Massachusetts has not been Democrat from top to bottom, side to side. The first time since 1952 that Massachusetts has had a Republican senator. Fairrington’s cartoon is a nicely layered comment on the historic moment. When I ponder editorial cartoons, I look for visual metaphors, images so memorable that they sear the observer’s brain pan thereby affecting whatever he/she thinks forever thereafter. At first blush, the metaphor in this cartoon is the Grand Old Pachyderm slaying a Democrat—a bloody though simple enough metaphor for the election of Scott Brown. But then I realized that the pool of blood forming under the corpse was in the shape of Massachusetts. And so the erstwhile Democrat blue state becomes, for the nonce, a Republican red. And with this fillip of visual information—likely to be overlooked by anyone not familiar with the shapes of U.S. states (and how many fresh highschool graduates these days are?)—Fairrington’s deft cartoon acquires a meaningful and supremely memorable complexity. It was the tea baggers, they say—not the hoary old elephant—that turned the trick for the Republicans. And the tea baggers are now often termed the “Tea Party,” a raucous and rude anti-government bunch of greater decibels than sense. Did you ever have tea parties when you were a kid? And if you did, wasn’t the tea always make-believe? Well, so is most of the tea bag world as envisioned by its ostensible leader, Glenn Beck, a preposterous erstwhile comedian who manages with almost every political utterance to contradict himself. Writes Thomas Frank in Playboy: “In his philosophical mode Beck often questions greed and materialism; in his political mode, he is dedicated to the utterly materialistic principle of free-market economics.” A constant cheerleader for Thomas Paine, whose pamphlets helped pave the way to the American revolution, Beck doesn’t discern that Paine disapproves of virtually every so-called “idea” in Beck’s political agenda. Beck’s reverence for the Founding Fathers’ Constitution is denounced by Paine who finds it absurd that one generation should bind succeeding generations to its way of thinking. Beck, who champions self-sufficiency and sees socialism lurking in every government program, probably never read the part of Paine’s The Rights of Man that urges old-age pensions, subsidies to the poor, welfare payments to mothers of small children, and guaranteed employment. And in The Age of Reason, it’s clear that Paine also doesn’t think much of Christianity, which Beck sees as inspiring the very words of the Constitution. No matter: in Beck’s make-believe world, facts don’t matter as much as self-serving opinions. Tea bags galore. **** Airport security faded as a topic for edtioonists and pundits. But not before David Harsanyi in the Denver Post observed that “if we are asked to remove our underwear at the airport, well, the terrorists have won.” Genuine security is not going to be possible, he continues, until we admit that terrorists “tend to come from certain places and subscribe to a certain religious affiliation.” But since such a politically incorrect posture is not likely, before long, we’ll all have to drop our trousers and bend over while a friendly TSA officer conducts a full body cavity search. At the New York Times, David Brooks averred that the most troubling aspect of the “debate” about body scanning is the childish assumption, on both the Left and the Right (where Brooks usually resides), that government has the duty and the ability to protect us from every danger. It can’t, and it won’t. ... In the struggle against terrorism, “bad things will happen, and we don’t have to lose our heads every time they do.” At Newsweek, Jon Meacham seems to concur: “So this is what winning may look like: smaller-bore plots, carried out (or not) by radicalized Islamists. ... A never-ending war is not a war we should not fight: it is just a war that never ends. The sooner we accept this, the better.” Most Americans—that is, a simple majority, 51%—think it’s okay to give up some liberties to make the U.S. safe from terrorism, according to a McClatchy-Ipsos poll. And 74% think full-body searches at airports is the most effective preventive; although 81% think better intelligence coordination is even more effective. Just 36% think “some of the governments proposals will go too far in restricting the public’s civil liberties.” Calvin Trillin, writing in The New Yorker, reports that the whole remove-the-shoes dodge was a result of a bet made by Khalid the Droll, an Islamist prankster in England, who said to his cell: “I bet I can get them to take off their shoes in airports.” And then he went out and recruited Richard Reid (described by British acquaintances as “very, very impressionable”) to put a bomb in his shoe. The underwear exercise is another of Khalid the Droll’s bets, Trillin says—and he, Trillin, predicted it in a book of his in 2006. CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv. Some in the women’s fashion trade are worried that the traditionally skinny runway models send the wrong message to American womanhood, bringing on all sorts of eating disorders. On the other hand, advocates for “plus size” models worry that these somewhat larger clothes horses send the wrong message at the obesity end of the spectrum. And then when the fashion mag V published its “size issue” featuring size-12 women, critics complained that the star of the issue, Crystal Renn, was only size 12. How could she be a “plus” at that diminutive dimension? How big is big enough? Air America, talk radio’s liberal answer to Rush Limbaugh, has pulled the plug and gone silent. ... Bankruptcies are on the rise again: with more than 1.4 million filings last year, 2009 is the seventh highest year on record, up 32 percent from 2008; there were 2 million in 2005, before the crash. ... Just hours after saying that God was punishing Haiti for making a “pact with the Devil,” televangelist Pat Robertson explained that it was all a misunderstanding: “Haiti?” he said, incredulous, “—I thought they said ‘Hades’.” Not really. This is a spoof, torvarich. (Thanks, Roy.) For about 60 years, someone has visited Edgar Allan Poe’s grave on the eve of his birth on January 19 and put roses and a half-empty bottle of cognac on the tombstone. Not this year. No one knows for sure who the mysterious midnight visitor might have been, but one possibility, a Baltimore poet and “known prankster” (according to the AP), died in his 60s the week before Poe’s birthday anniversary. In Denver’s Boettcher Concert Hall a week or so ago, the Colorado Symphony Orchestra just finished the second song of Peter Liberson’s “Neruda Songs” when someone in the audience yelled out, “That’s just awful!” “Who does he think he is? Joe Wilson?” quipped the Denver Post’s Bill Husted. On October 19, Erick Williamson, 29, a resident of suburban Fairfax County in Virginia was arrested and charged with indecent exposure because two women and a 7-year-old boy saw him naked. Williamson customarily sleeps in the nude, and he made the mistake of not donning a robe before going into his kitchen to make breakfast; the peeping toms, walking by his house, saw him through the window. A judge found Williamson guilty but didn’t fine him or sentence him to jail; Williamson is appealing. One of the states that permits medical marijuana, Colorado has been dubbed “America’s cannabis capital.” By the end of 2009, Denver had issued sales-tax licenses to more Maryjane dispensaries than there are Starbucks coffee houses in the metropolitan area—twice the number of the city’s public schools and a third more than the number of retail liquor stores. In nearby Nederland, a mountain village of about 1,400 souls (mostly refugees from an earlier, hippier, time), may soon vote to legalize the use of weed, as another mountain town, Breckenridge, already has. Nederland has 5 dispensaries and is considering holding a Cannabis Festival to celebrate the virtues of medical mj. Barack O’Bama was called to jury duty in Cook County, Illinois, but didn’t make it: he was preparing his State of the Union speech. BOOK MARQUEE Previews and Proclamations of Coming Attractions and Short Reviews Things We Knew Were Going To Happen Dept. The Archie bigamy series, Nos. 600-605 of the comic book, plus the “epilogue” in No. 606, are being issued as a 168-page paperback tome, The Archie Wedding: Will You Marry Me? for $14.95. ... IDW, jumping on the R. Crumb Illustrated Genesis Norton Bible-wagon, is offering The Bible: Eden, painted by Scott Hampton and adapted by Keith Griffen and Dave Elliott; 112 pages in paperback, $17.99. Then, not to be outdone, here comes Titan with Classic Bible Stories, Vol. 1: Jesus, The Road to Courage / Mark: The Youngest Disciple, the work of Frank Hampson and Frank “Garth” Bellamy; 112 pages in hardcover, $19.95. ... Finally, changing the subject somewhat, here’s Seth Grahame-Smith’s novel, Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, 352 pages in hardcover, $21.99. Remember that “milk sickness” Abe’s mother died of when he was nine? Turns out his mother’s “deadly affliction” was the work of, yes, a local vampire. So the Civil War, widely believed to be fought to keep the United States intact as a nation or to eliminate slavery, was actually a struggle between Lincoln and those who killed his mother. ... We didn’t see this one coming, but here it is anyhow: Dave Stevens’ posthumously compiled The Rocketeer: The Complete Adventures is given an “A” by reviewer Ken Tucker in Entertainment Weekly (January 29). BOOK REVIEWS Critiques & Crotchets Two massive reprint projects are now available at vastly reduced prices through Daedalus Books (salebooks.com): The Completely Mad Don Martin, 1956-1988: Mad’s Greatest Artists (1,000 10x14-inch pages, b/w and color) and Playboy Cover to Cover: The ’50s—Searchable Digital Archive—Every Issue, Every Page, 1953-1959, 2 books plus 2 DVDs. The Don Martin archive comes in two sumptuous volumes, linen-bound and slipcased and originally priced at $150, now available through Daedalus for $29.98. If you missed this trove when it came out in 2007, now you can get it at a bargain basement price. The write-up says it includes “every one of Martin’s strips, covers, posters, and stickers from his decades at Mad” accompanied by “tributes” from many of the other Mad cartooners and fans—Al Jaffe, Sergio Aragones, Jim “Garfield” Davis, Steven Spielberg, and Jon Stewart to name a few. The book also claims to include rare photographs, and “original pencil sketches” by Martin and his long-time writer, Duck Edwing. That’s a little extravagant: there are three (3) photographs, two group shots of the “usual gang of idiots” on one of the famed Mad junkets to exotic climes, the other of Martin sunning himself on a beach; three (3) pencil roughs by Edwing, and only one (1) pencil rough by Martin. Due to the deflation in fact of the inflated claim, I don’t know if this brace of books actually includes “every one of Martin’s” works, as touted. Missing, incidentally—but alluded to in the books’ introductory forewords and prefaces and introductions— is any evidence whatsoever of Martin’s “fine art pen and ink drawings” that decorated his home; I’d love to see evidence in support of that assertion. But the books offer nearly 1,000 pages of Martin cartoons, strips, etc., and that’s surely enough for rabid fans of Mad’s Madest cartoonist. I am not one of those, incidentally: I admire the man’s genius for uproarious visuals and wholly unprecedented sound effects (the end papers are all Martin sound effects, many of which were actually concocted by Edwing), but the slapstick bait-and-switch gags soon seem repetitive. I suspect most of Martin’s fans, as much as they enjoy his work, tire of it as a regular diet, which may account for this bargain offering. The extravagance of the book production suggests that the publisher was

operating under a delusion about Martin’s globe-girdling greatness—an idea doubtless

fostered by Martin’s widow, who managed his business—and, under the spell, over-estimated the fame of his subject, producing, instead of a compendium of cartoons, a

monument to the delusion. And when the reputed millions of Martin fans didn’t spring

for the elegance of the eulogy, the publisher For sure, there’s a huge harvest of Martin maniacality here, and even if, like me, you have to swear off for a month after spending an hour with his comedy, this collection is too good to miss at this price. For the whole Don Martin story, visit Harv’s Hindsight for May 2004, where we rehearse the events of his life and career and catalogue the quirky appeal of his cartooning. ***** The Playboy package is an even bigger bargain: originally priced at $100, it is available through Daedalus for merely $29.98. The package is a red box that’s hinged like a book, and when I opened it, I found two shallow pockets, left and right: in the one on the right are a “photo album full of behind-the-scenes views of Playboy’s first decade” and a facsimile of the magazine’s first issue; in the other, another hinged box, this one containing 2 DVDs—one is the installation disk; the other archives “every page” of the magazine from its famously undated debut in November 1953 through December 1959. The magazine’s first issue, judging from the facsimile, is surprisingly slim—just 42 pages, no ads. It contains the celebrated color photo of Marilyn Monroe, sprawled naked on her side on a sheet of velvet red, accompanied by a two-page article, unquestionably written by the magazine’s founder, Hugh M. Hefner, entitled “What Makes Marilyn?” (Not “Who Makes Marilyn”; but the sexual implication lurks.) The article, which is sprinkled with a few canned publicity photos of the sex symbol clothed, concludes: “More than either face or body, it is what little Norma Jean has learned to do with both. Caruso, they say, could break a wine glass with his voice. Marilyn shatters whole rows of beer steins with a single, seductive look. And when she turns and slowly undulates out of a room, seismographs pick up quivers a thousand miles away.” Extravagantly put, but Hef has captured exactly what it was that Marilyn did that distinguished her from all the other Hollywood starlets of the day—the way she juggled the parts of her derriere when she knew someone was watching her walking away. It wasn’t her figure or her bosom, which, after all, is scarcely as spectacular as, say, Sophia Loren’s, to name another idol of the day. No, it was Marilyn’s “going away” look that proclaimed her the sex goddess of the age. The first page in the issue is devoted to Hef’s editorial, which he begins by advising readers that “we aren’t a ‘family magazine.’ If you’re somebody’s sister, wife or mother-in-law and picked us up by mistake, please pass us along to the man in your life and get back to your Ladies Home Journal.” But you’d be hard-pressed from reading the rest of the prospectus to imagine that Playboy would in the future so studiously celebrate female anatomy and the everlasting coital encounter. “Within the pages of Playboy,” Hef continues, “you will find articles, fiction, picture stories, cartoons, humor and special features culled from many sources, past and present, to form a pleasure-primer styled to the masculine taste.” You must read between the lines and code words—“pleasure-primer,” “picture stories”—to find Marilyn, going away or not. After extolling the virtues of urban life, the indoors where “we plan on spending most of our time,” Hef concludes with a reference to Alfred Kinsey’s sensational 1948 research report on the sexual behavior of the American male (which revealed that American males often—more often than heretofore supposed—behave sexually) that so fascinated him when editing Shaft, the humor magazine at the University of Illinois: “We believe, too, that we are filling a publishing need only slightly less important than the one just taken care of by the Kinsey Report. The magazines now being produced for the city-bred male (there are two—count ’em, two) have, of late, placed so much emphasis on fashion, travel, and ‘how-to-do-it’ features on everything from avoiding a hernia to building your own steam bath, that entertainment has been all but pushed from their pages. Playboy will emphasize entertainment.” Entertainment “for Men” the cover unabashedly proclaims, boldfacing the masculine noun. The magazine’s first issue also prints numerous cartoons, one of which, a full-pager, is in color—strangely unsigned, as if the cartoonist didn’t quite want to be associated with a magazine called, probably, at the time he submitted his offerings, Stag Party. Together, the cover and the back cover of the inaugural issue deliver a precis of

the magazine’s contents and intentions—in this issue and for several years to come. On

the back cover under the heading “In This Issue,” photos of Tommy Dorsey on the

trombone and of a football player (Red Grange, as it happens), and a cartoonish

drawing of a man and woman, her blouse open to the navel, proclaiming “a humorous

tale of adultery” within (the everlasting excerpts from Boccaccio’s Decameron that

populated every issue of Playboy for decades to come, morphing, finally, into the more

generic Ribald Classic). On the cover, Marilyn waving to us and, next to her cleavage, a

tiny drawing of a running naked woman labeled “Vip on Sex.” Playboy is all there on the

front and back covers—pin-up sex, jazz, sports, titillating fiction, and cartoons. Apart from the subjects and their treatment, only a little of the first issue is original with the magazine. Much of the content is reprinted from its initial publication elsewhere and some of it is in the public domain. A Sherlock Holmes short story, reprinted “with the permission of the estate of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle,” opens with the world’s most famous detective injecting himself with the notorious “seven percent solution” of cocaine. Illustrated with a two-color drawing of Holmes (looking, here, like Christopher Plummer, who would, later, play Holmes in movies) administering the shot. “Vip on Sex” gets two pages, whereon are reprinted five Vip cartoons, all from Wild, Wild Women. Vip will show up several more times in the magazine’s first years, always in reprint. (For Vip’s history, see Harv’s Hindsight for May 2005.) An Ambrose Bierce short story is presumably pilfered from the public domain. The first issue is nonetheless remarkable for its cartoon content, all of which, apart from Vip’s cartoons, is original with this publication. In addition to Vip’s quintet, there are two more of the small dimension—and 6 full-page cartoons, two of which are photographs of fetching nekid ladies with cartoon captions, a device Hef abandoned after this issue. The ratio of cartoons to the magazine’s page count is higher than in most subsequent issues: full-pagers come in at 1/7 (one cartoon every 7 pages); small cartoons, 1/6. (The ratio of photographs of barenekidwimmin, counting those two full-page “cartoon” appearances, is 1/5, much better than the latter-day Playboy, accounting, no doubt, for the magazine’s initial success back in the early 1950s when the only nude women in photographs were those in nudist magazines, usually sold from under the counter, or, sometimes, in “photography” magazines.) Two of the cartoonists in the first issue will re-appear in virtually every issue for

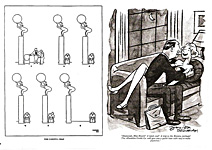

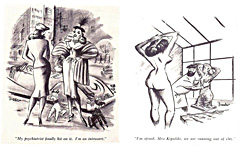

decades: Gardner Rea, with his distinctive outline style of drawing, and Al Stine,

whose illustrative artwork lent an aura of realism to the cartoons he drew. Stine’s

cartoons would soon begin to chronicle the sexual appetites and adventures of two

attractive young women, Babs and Shirley, a blonde and a brunette, as they conquered

the male populace. Another illustrator whose work appears here as a cartoon and

subsequently as decorations for articles and fiction is Ben Denison. Later, he produced

a series of cartoons in which lovingly rendered pictures of famous sports cars were the

dominant feature. One of the full-pagers in this issue looks almost as if it were rendered

by Peter Arno, but it isn’t: the cartoonist is Julien Dedman, whose work I’ve never

seen elsewhere. He appears in Playboy for several of the early issues, humorous text

pieces as well as cartoons, notably a parody of Mickey Spillane in February 1954. Then

he disappears, as far as I know, forever. Hef publishes one of his own cartoons in the debut issue, too: two art students

stand gaga in front of an abstract painting of a nude and say, “Man—is she stacked.”

This cartoon is a reprise of one Hef did while working on Shaft, where the cartoon was

printed large enough to make sense: in the first issue of Playboy, the inscription,

“nude,” under the abstract painting is missing, and so the joke is somewhat obscure.

You can find the Shaft version of the cartoon and Hef’s history as “Playboy’s First

Cartoonist” under that heading in Harv’s Hindsight for September 2008, in case you