|

||||||||||||||||||

Opus 202 (March 12, 2007). Captain America dies and the

Mainstream Media demonstrates once again how completely derelict it is, failing

to see any significance in the death. After that bombshell, what else can we

say? Well, plenty, as usual. Big Book

Sale, for one thing: yes, it’s time, once again, for us to try to dispose

of all those books we bought by mistake, not realizing we already had a copy in

the Rancid Raves Library. Plus a hoard of review copies, offered at half-price.

And we’ve lowered the prices on all those titles that were listed last time but

didn’t sell. Here’s where you can find them all. Apart from that, our

Big Event this time offers reviews and discussion of comics in other countries,

with an emphasis on Britain, including a long and amply illustrated examination

of the British wartime strip, Jane,

wherein the eponymous heroine kept on stripping. We also discuss the fate of

American newspapers again and discover that Roy Lichtenstein was a bitterly

disappointed would-be comic book cartooner. Finally, we look at the cartoons of

the political cartoonist whose obsession resulted, eventually, in the movie

“Zodiac,” and we reveal the Starbucks hoax. Here’s what’s here, in order, by

department, beginning with one of our Rare Errors:

Correction

on Wiley’s Homer

NOUS R US

Captain

America Is Dead and What That Means

Ormes

Society Formed for Black Women Cartooners

Glyph

Award Nominees

Gaston

Lagaffe’s Birthday in Brussels

AAEC’s

50th]

Doll

Man—One of the First Superheroes

Trudeau

on B.D.

Scott

Adams on the Surge

Manga

Fad

Nasty

Words in Comic Strips

Eustace

Tilley and the New Yorker’s Annual Anniversary Issue

New

Yorker Cartoonists Sound Off

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST

The

Twin Towers Conspiracy

ART FOR ART’S SAKE

Roy Lichtenstein’s Fraud

BOOK MARQUEE

New

Mutt & Jeff Reprint Coming from NBM

THE FROTH ESTATE

Are

Newspapers Being Owned Locally Again? Or Not

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE

Cross

Bronx, Lone Ranger, Jonah Hex

REPRINZ

Pickles

EDITOONERY

Asay

Retires

Tom

Toles on Censorship

SIGNS OF THE ZODIAC

Graysmith’s

Cartoons

COMIC

STRIP WATCH

Judge

Parker, Get Fuzzy, Piranha Club, Sam and Silo, Pearls before Swine, Rudy Park

Free

Comic Book Day, Cartoon Appreciation Week, and the Webslinger’s New Movie

INNOCENCE ABROAD

Reviews

of The Essential Guide to World Comics

and Great British Comics: A Century

The

Unforgettable Jane

Who

Peeled for the Normandy Invasion

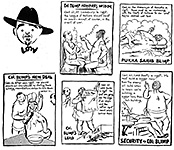

Colonel

Blimp

Starbucks

and the Great Coffee Scandal: A Hoax

And

our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by

clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just

this lengthy installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned.

Without further adieu—

RARE GAFFE

We

goofed again, one of our rare gaffs here at Rancid Raves. Last time, discussing Wiley Miller’s various enterprises,

I talked about Homer, his strip about

an inquisitive angel, saying that when he discontinued the print version in

newspapers, he offered to continue the strip online if he could interest enough

paying subscribers. And then I said that not enough signed up so Miller

cancelled the plan. Actually, Miller tells me, Homer did attract enough paying subscribers to make it worthwhile

for him to continue it, but Miller was at that very moment in the throes of

doing two other complicated things—moving himself and his family from Iowa to

California and moving Non Sequitur from

one syndicate to another. He just couldn’t find the energy or time to do the

online strip, and so he “shelved it.” He planned, then, to revive Homer in a

series of books, and, after the success of his Ordinary Basil book for children (it “has been met with nothing but

rave reviews,” he reports), the second of which will come out next fall, he

intends to return to Homer and the book plan.

NOUS R US

All the News That Gives Us Fits

Captain America is dead. Again. This time, for a change, his death

signals something other than the poverty of his writers’ imaginations. This

time, the death of Captain America represents the death of American values and,

hence, of America itself. With that, Marvel Comics has taken a defiant political stand. And it’s about time

someone did. Captain America’s death is a fitting ending to Marvel’s Civil War,

an philosophical dispute in which superheroes chose up sides on the question of

whether to register and reveal their secret identities or not. Captain America

regarded the government’s new requirement as an erosion of his civil liberties

and refused to register. But, as I understand it (yup: I’m commenting on this

without having actually read the series; I have, however, read what various

observers have said about it), Captain America eventually capitulated to Iron

Man and the rest of the gang who supported the government’s dictate. In

surrendering, Captain America gave up the American values he has always stood

for. Without those values, America isn’t America anymore. And so the death of

Captain America isn’t just the death of an individual: because he is an icon,

when he died it meant that America is dead, too. The comic book character won’t

be dead for long, of course. His comic book is still on Marvel’s publishing

schedule; and that movie is still lurking somewhere in the future. So Captain

America will be back. As Marvel Entertainment’s president Dan Buckley said:

“This is the end of Steve Rogers, the meat and potatoes guy from 1941. But

Captain America is a costume [I’d say ‘uniform’], and there are other people

who could take it over.” But if the thematic import of his death is to be

sustained, no one should don the uniform until traditional American values have

been restored—until we no longer have a national policy of torturing helpless

prisoners, eavesdropping on citizens, denying habeas corpus, and the rest. Then

the old uniform can come out of mothballs. Incidentally, the episode—death by a

sniper’s bullet—was an eerie echo of that November day in Dallas in 1963;

coupling the two murders together in this fashion gave the death of Captain

America an extra layer of emotional meaning. Neatly done, Marvel—all around.

Although the impending demise was a well-kept secret, we should have seen it

coming: given all the parallels to the real world assault on American values,

we should have guessed that someone had to die, and who better than the

American icon?

The MSM, reporting this event,

mostly missed the import of the story—that is, they didn’t understand, or even

know, the issues being explored in the Civil War series, and so they couldn’t

interpret Captain America’s demise as a thematic, political, statement. Stephen

Colbert, on the other hand, knew exactly what was at stake. Naturally, he

favored Iron Man’s side in the dispute because, as he explained on the “Colbert

Report,” Iron Man is really Tony Stark and Stark is a defense contractor, and

all patriotic Americans support defense contractors. Captain America, Colbert

explained, refused to give up “a few minor freedoms” so Americans could be safe.

The lesson, he went on, is clear: those who fight to protect American freedoms

are dangerous. Colbert realizes, of course, that Captain America will go on—the

uniform will be taken up and worn by some other patriot. And he nominated

Alberto Gonzales, recommending that the red-white-and-blue color scheme of the

time-honored threads be discarded in favor of the colors of the Emergency Alert

System.

Because organizations are widely

rumored to nurture the things they’re organized for, a graphic novelist who

works at Publisher’s Weekly has just

formed a new one dedicated to promoting black women cartoonists, the Ormes

Society, named for the legendary pioneering cartoonist of color Zelda “Jackie” Ormes. Ormes created

Torchy Brown in 1937 and syndicated her creation as Torchy Brown in Dixie to Harlem, a Sunday strip, to fifteen black

newspapers around the country, home-basing it in the Pittsburgh Courier, where Ormes was working as a sports writer.

Torchy went on a ten-year vacation in 1940, and Ormes produced single-panel

cartoons (Candy about a black maid

and Patty Jo ’n’ Ginger, about two

girls) and moved to Chicago where she worked for the Chicago Defender, albeit not in any artistic capacity. In 1950,

Torchy returned in Torchy in Heartbeats, which

lasted for about five years. In both her incarnations, Torchy flew in the face

of the custom of the times: she was neither a maid nor a mammy but a beautiful

black adventuress in the Brenda Starr tradition, complete with life-threatening

dangers and romance hanging at every cliff. According to Trina Robbins in A Century of

Women Cartoonists: “What kept the strip from being a black soap opera was

Ormes’ treatment of segregation, bigotry and, in an age when ecology was a

virtually unknown word, environmental pollution.” More information about

pioneering African American cartoonists can be found at Tim Jackson’s www.clstoons.com;

and the Ormes Society is at http://theormessociety.com

Incidentally, this year’s nominees

for Glyph Awards include two friends and associates of mine: Damian Duffy for Best Writer (with Deborah Grisom) for Day 8, a short story about a Katrina

rescue mission, and Duffy, Grisom and John

Jennings, the artist, for Story of the Year; Jennings is also nominated for

drawing the Best Character in Day 8. The Glyph Comics Awards (GCA) recognize “the best in comics made by, for, and

about people of color. ... While it is not exclusive to black creators, it does

strive to honor those who have made the greatest contributions to the comics

medium in terms of both critical and commercial appeal. By doing so, the goal

is to encourage more diverse and high quality work across the board and to

inspire new creators to add their voices to the field.” The GCA, now in its

second year, takes its name from the blog Glyphs:

The Language of the Black Comics Community at Pop Culture Shock (http://popcultureshock.com),

started in 2005 by comics journalist Rich Watson “as a means to provide news

and commentary of comics with black themes, as well as tangential topics in

fields of black science fiction/fantasy and animation.” Watson is founder of

the GCA and chairman of the committee. Nominees for Best Comic Strip are: Candorville, Darrin Bell; The K

Chronicles, Keith Knight; Templar, Arzona, Spike; (th)Ink, Knight; and Watch Your Head, Cory

Thomas. Nominees for Best Comic Book Fan Award are: Black Panther: The Bride, Crisis Aftermath: The Spectre, Firestorm Nos.

28-32, New Avengers No. 22, and Storm. The awards will be presented at the East Coast Black Age of Comics

Convention at Temple University’s Anderson Hall in Philadelphia, May 18-19.

Fans are invited to vote on the Best Comic Book at www.ecbacc.com through the month of March. Nominees in other categories are listed at the

aforementioned Pop Culture Shock site.

On March 1, everyone in Brussels

could park free. In honor of the 50th anniversary of the birth of

Gaston Lagaffe, a colossally lazy accident-prone comic strip character created

by Andre Franquin, the mayor of the

Belgium’s capital city turned off the parking meters (euronews.net). It was a

supremely fitting tribute: one of the plagues in Gaston’s travesty-laden life

involves his obsession with not paying for parking his dilapidated car. (I

recently inquired about purchasing an original Gaston Lagaffe; Kim Thompson at

Fantagraphics, another Franquin fan, told me that the most recent price he’d

seen was $30,000. There goes another of my lifelong dreams.) The December 15,

2006 issue of American Way devoted 8 pages

to a discussion of Brussels as “the international center of comic-strip art

[known in those parts as the ninth art] and home to the world’s most important

comic-strip museum, 25 comics stores, and 30 larger-than-life murals of

favorite comics characters.” The museum’s holdings include 6,000 original

drawings by 500 cartoonists, plus 40,000 comic books in 20 languages. The

museum may be the world’s “most important,” but its collection is not the

world’s largest, a distinction probably befalling Mort Walker’s National Cartoon Museum, which claims over 200,000

pieces. The Library of Congress’s collection was more than Speaking of anniversaries, February

28 was the 50th anniversary of the incorporation of the Association

of American Editorial Cartoonists, which will hold a suitable celebration at

its annual meeting over July 4 in Washington, D.C.; AAEC’s website is http://editorialcartoonists.com . ... Editor & Publisher reports that Jim Morin, editoonist

at the Miami Herald, is this year’s

winner of the $10,000 Herblock Prize. Morin, who has been at the paper almost

30 years, won the Pulitzer in 1996. ... E&P further reports that Austin Monthly magazine named the Austin American-Statesman’s editorial cartoonist Ben Sargent "one

of the 10 coolest creative people" in the Texas capital city. Sargent, a

1982 Pulitzer Prize winner, is certainly one of the snappiest dressers in editoonery,

specializing in three-piece suits and ten-gallon hats, not to mention

distinguished foliage around the chin. ... And Mike Luckovich at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution was awarded the year’s $1,500 Headliner award last week. ... Finally,

regaling us with leaks from the Pulitzer deliberations, E&P says the nominees for this years Pulitzer in editorial

cartooning are Walt Handelsaman (Newsday), Nick Anderson (Houston

Chronicle), and Mike Thompson (Detroit Free Press). In fairness, I

must note a vague memory of mine to the effect that the leaked information E&P reported last year was wrong on

one count; so, maybe again.

Golden West College in Huntington

Beach, California, is retiring its mascot of 36 years, Rustler Sam, a cowpoke

character designed by Tom K. Ryan, creator

of the comic strip Tumbleweeds. The

college, reports the Orange County

Register, is systematically modernizing its image and has already changed

the school logo from a setting sun (“too sleepy and associated with the end of

life”) to a surfboard. Sam got a make-over in the 1990s, losing the cigarette

that had always dangled from his lip. Candidates to replace the grizzled

rustler—a surfer, a wave rider, a shark, a stingray, and a sea dragon.

At arflovers.com, a gleeful site maintained with a maniacal chortle by Craig Yoe with the help of the Yoe

Studio minions, recent speculation holds that “Popeye is a stoner,” which Yoe

says he first heard of on “the terrific animation blog CartoonBrew” and

subsequently “turned up conclusive evidence that what Popeye had in his pipe

was indeed wacky tobacky (i.e., marijuana).” The word spinach, it is averred, was, at the time of Popeye’s animated

incarnation, “a popular euphemism for marijuana celebrated as such in jazz

songs.” I’ve heard spinach used to refer to folding money—even a beard—but not,

until now, mj; but I’ll take your word for it, Craig. ... At the same ethereal

venue, every Monday is Doll Man Day in honor of one of the first four-color

superheroes: Darrell Dane invented the formula that enabled him to shrink to

his minuscule crime-fighting size in Feature

Comics No. 27, cover-dated December 1939. “One of the first” indeed: Doll

Man is poised right on the cusp of the creation cycle that would flood the pulp

world with longjohn legions, most of whom are costumed colorfully but not

endowed with any superpowers. Of the superpowered sort, only Superman (in Action Comics No. 1, June 1938), Wonder

Man (in Wonder Comics No. 1, May

1939; and he was promptly sued out of existence as a Superman rip-off), and the

Human Torch and Sub-Mariner (both in Marvel

Comics No. 1, November 1939), preceded Doll Man. The first costumed but

super-less hero to arrive after Superman was the Arrow, who debuted in Funny Pages No. 21 in September 1938;

after him came another costumed do-gooder, the Crimson Avenger in Detective Comics No. 20, October 1938.

Batman, the most famous of the early spandex-clad, didn’t arrive until May 1939

in Detective Comics No. 27.

B.D. is going to make it back to

some sort of normal life. “That’s the plan,” said Doonesbury’s Garry Trudeau in

an interview with Elizabeth Gettelman in Mother

Jones (February). “I’d like to have him return to Walter Reed as a peer

visitor, so I can get into the subject of traumatic brain injury, the signature

wound of this war.” Asked how he is received by the troops, Trudeau said: “At

both readings I’ve done at the Pentagon, I signed over 400 books, so I can

hardly ask for a better reception. I got one drive-by dis from a soldier, but

it was over strips that pissed her off during Gulf War I.” His two B.D. books

have introductions by John McCain and General Richard Myers, neither of whom

groused about the strip. If they had reservations, Trudeau said, “they went

unvoiced. Both men knew where I stood on the war. But the B.D. story is

politics-free; it just means to be a clear-eyed accounting of the sorts of

sacrifices that thousands of our countrymen are making in our name.” The strip

is rarely pulled from papers these days, and when it is, “its usually about

language, not political content,” the cartoonist said. “I’ve gotten very little

public push-back on the B.D. series. Politics is only a small part of what I

do; the strip is mostly about the characters.” When Doonesbury went to Vietnam, the conflict was treated humorously,

Gettelman observed, but now war is treated more seriously—why? Said Trudeau:

“When I was writing about Vietnam, I was 22. Now I’m 58. I know more.”

Riding on the assumed popularity of

the “Ghost Rider” movie, the Comics

Buyer’s Guide for May (No. 1628) has a nice piece about Dick Ayer’s original Ghost Rider, who

was, back in the early 1950s, the star of a horse opera comic bearing his name;

he started in November 1949 as a backup feature in Tim Holt No. 11 and then graduated to his own title. Ayers’ work

always stood out: he was a skilled artist and, lucky for Ghost Rider, could

draw horses superbly, but the distinctive feature of his style was the way he

rendered the eyes of his human characters—they seemed sunken in their skulls,

burning with an almost fiendish inner madness.

Name-Dropping

and Tale-Bearing

Clint

Eastwood “is a man of few words and a gentle, beloved director,” writes Jean

Wolf in Parade (February 25). But

Eastwood, it seems, has an aversion to posing for photographs. At the Golden

Globes, when he was asked by a photographer to pose with his trophy for

“Letters from Iwo Jima,” he said: “I don’t pose. I don’t pose for anyone. Who

do you think I am—Paris Hilton?” So when, during the Oscars ceremony, Ellen

Degeneres sidled up to Eastwood on one of her forays into the audience and

inveigled the crusty movie-maker into posing for a photograph, she was

doubtless engaging in a little low-key satire, staging the event in a way that

Eastwood could scarcely decline to have his picture taken this time. She also

got Steven Spielberg to do the photographing, and that couldn’t hurt. Eastwood

was probably squirming with contradictory inner conflict, but he didn’t look

it.

Scott Adams Examines the Surge

In

his latest blog, excerpted by E&P, Dilbert’s creator subjects George W. (“Warlord”) Bush’s latest scheme to penetrating

analysis: “President Bush has unveiled his plan to achieve the top

goal

of his presidency: a popularity rating of zero. The only risk to his plan is if

this Iraqi 'surge' concept actually works. So let's examine his chances. On the

American side, all we have to do is stretch the military to the point of

breaking, spend tens of billions of dollars, and do what has never been done,

i.e. secure a major Iraqi city and let the highly capable Iraqi government

forces hold it. And popularity-wise, it would be helpful to do that without any

casualties. This is the same successful strategy that has brought democracy to

several blocks in Kabul, except at night.

“On the flip side, the insurgents

will be faced with the insurmountable task of going on vacation outside of

Baghdad until all the surging is finished. Then they can wander back, all

tanned and rested, and pick up where they left off. ...”

Manga

Fad

In

his “Manga for the Mainstream” column in the latest Comics Buyer’s Guide, Bill Aguiar, apologist for the genre, rambles

on for a couple pages about why manga aren’t in the comic book shops. At first,

Aguiar says, several years ago at the beginning of the current tidal wave,

manga publishers tried to interest the specialty stores in stocking their

books, but the comics shops weren’t—and aren’t still—making much of an effort

to sell these strange new comic books/graphic novels. So the manga publishers,

quite naturally, turned to the grown-up bookstores, where, as we all know,

they’ve taken over row upon row of bookracks. And now the presence of manga is

so pronounced and so successful in this country that indigenous publishers are

cranking out manga imitations, and comics creators are “incorporating manga

influence into their comics.” But still, comics specialty shops seem

indifferent to the genre. “Sooner or later,” Aguiar says, a new kind of store

will start cropping up on these shores—“manga stores, comics shops that only

stock manga and sell coffee or soda—stores like that already exist in Asia.”

Some enterprising entrepreneur will surely see the manga phenomenon as an

opportunity to exploit. Such stores, unlike regular bookstores, will stock “a

complete line of titles from every company,” and clerks will know the product

so they can steer customers to titles that fit their interests. Aguiar fears

that “the market will remain bifurcated”—bookstores on the one hand, comics

shops on the other—and they’ll compete with each other when they should be

complementing each other. If so, he says, it will be “another wasted

opportunity in comics history.” Comic book shops should “reach out” and offer

the kind of manga service that the Asian shops offer—expertise, coffee and

sodas—in short, a salon for manga and manga lovers, who, Aguiar argues, will

discover other comics there that they’ll like, and everyone will prosper.

Last September, the Mainichi Daily News announced that, come

January 2007, some of Shakespeare’s plays would assume manga form in Britain.

“Published by Self Made Hero, a division of Metro Media Ltd., Manga Shakespeare is designed to revive

the Bard’s lagging popularity among British teenagers, by giving the plays an

injection of ‘cool Japan.’” The first two plays to attempt to capitalize on the

manga fad in the UK are Romeo and Juliet and Hamlet, whose protagonist, according

to artist Emma Vieceli, is “the

ultimate bishonen character”: bishonen heroes, or “beautiful boys,” are

troubled, rather girlish characters, doted on by a mainly female readership.

Said Vieceli: “They need to be angsty, broody, beautiful and have lots of

trouble and strife going on in their life, and if possible die at the end.

Hamlet is absolutely perfect for that.” Churn, stomach, churn. (Angsty?)

Watching

Our Language For Us

Amy

Lago, comics editor for the Washington Post Writers Group, recently posted at www.postwritersgroup.com/groupblog a couple increments in what

deserves to be an on-going argument about what’s permissible language in strips

(“The Language Feint” and “Guilt Trips”). She discussed her editorial

encounters with such outre expressions as “bite me,” “suck,” “blow,” and “ass.”

Lago usually opts for outspokenness: “I think using staid language is a mistake

for newspapers. I think that it’s important to recognize that language

changes—what once was unacceptable to one generation becomes acceptable to

another.” I agree. But the annoying aspect of the terms I just mentioned is

that many readers aren’t quite sure whether they are nasty or not. And if

readers aren’t sure, neither are editors, who arrive at certainty, apparently,

only when it has been heavily endorsed by reader reaction. The terms themselves

are somewhat ambiguous: “suck” and “blow” may refer to the ancient and honorable

sexual exercise of fellatio; but maybe not. Or, at least, not any more.

Something “blows” or “sucks” when it is boring or obnoxious, as Christopher

Hitchens lately observed—but is fellatio either “boring” or “obnoxious”?

Confusion reigns amid the gradual mutation of meaning. And with this

vocabulary, we are in midstream, halfway between verboten and common

parlance—and therefore at neither. No wonder editors are hesitant about letting

comic strips get by with using words like these. “Geez” has finally escaped its

original association with “Jesus,” but we still can’t publish “shit happens”

with impunity. Not even “crap,” it seems. Lago applauded Scott Adams for feinting “carp” for “crap” some years ago. “‘Oh,

carp’ never caught on,” she reports, “but it was brilliant. Everybody

understood what Adams meant, but those who could choose to be offended—‘If my

child reads that word in the newspaper, he’s going to think it’s okay to say,

and it’s not!’—couldn’t be [offended], because Adams hadn’t used it.” But Lago has

been burned enough to grow cautious.

“Nowadays,” she writes, “I try to be

frank with cartoonists. I try to analyze why a strip will be viewed as

offensive to readers, how editors may react to reader complaints and whether or

not I really feel the strip will suffer cancellations if the cartoonist chooses

to go forward with a potentially problematic strip.” That’s about the best

service an editor can supply to a cartoonist. Be another (friendly)

consciousness, pointing out the various perverse misunderstandings likely to be

prompted by the usage the cartoonist has employed: Do you realize how this term

or situation can be misinterpreted by the bent and bruised psyches out there

among newspaper readers? But, Lago goes on, “nothing could have prepared me for

the reader—with a medical degree no less—who called the December 24 Pickles strip ‘sadistic.’”

When I asked about this, Lago

explained: “Earl and Opal, the elder Pickles, tell Nelson, their grandson, that

they hide the Pickle Xmas tree ornament on Xmas eve, and whoever finds it Xmas

morning gets a surprise. After Nelson leaves the room, Opal says, ‘Should we

tell him the surprise is washing the dinner dishes?’ So some idiot in Buffalo

felt the December 24 Pickles was

‘sadistic.’ Honestly, some people can't take a joke. And if you can't take a joke, why, pray tell, are you reading the

comics pages?!”

I dare not leave this subject

without a word or two about Hitchens’ essay, alluded to above. It appeared in

the July 2006 issue of Vanity Fair,

the one with Sandra Bullock in dishabille on the cover, and it, like many of

Hitchens’ utterances, is a tour de farce, an extravagant flight of reason and an enviable display of linguistic

pyrotechnics. His contention, which he advances and defends with relentless logic,

is that fellatio is “as American as apple pie.” Fellatio, he observes, comes

from the Latin verb “to suck,” which leads, with the relentless logic I

mentioned, to the question: “Which is it—blow or suck?” And that, in its turn,

leads to Hitchens’ reciting an Old Joke: “No, darling. Suck it. ‘Blow’ is a mere

figure of speech.” (Early in my lost career as a gag cartoonist, I did a

cartoon that alluded to this confusion. It sold, too—very quickly. Sales are

not necessarily indicators of high art, I realize; but sales are nothing to

sneeze over in a capitalistic society. I thought the funny part of the gag was

in imagining the girl in need of the doll. A female friend to whom I showed the

cartoon didn’t think it was at all funny. Not at all. Hitchens’ latest essay in Vanity Fair, January’s, is about

whether women have a sense of humor, so I wonder ...) Footnit: Several

school libraries have elected not to circulate Susan Patron’s Newbery

Medal-award winning children’s novel, The

Higher Power of Lucky, because the word

“scrotum” appears in the book. On the first page, no less. Take that, you

starry-eyed liberals. The scrotum in question, incidentally, belongs to a dog

that was bitten by a rattlesnake. When the 10-year-old heroine of the book

hears the odd word, she decides that it sounds “secret, but also important.”

Take that, you starry-eyed reactionaries. (The Week)

Eustace

Tilley Returns

Cartoonist Rea Irvin’s supercilious

anachronism, that 18th century boulevardier inspecting a passing

butterfly, returned to the cover of The

New Yorker to celebrate the magazine’s 82nd anniversary the last

week in February—a gratifying encore for the hide-bound geezers among us. Chris Ware’s Tilley last year was a

triumph, but it’s nice to have Irvin’s classic back for the occasion. The

magazine’s founder, Harold Ross, believed that the best thing about the first issue had been Irvin's cover

drawing, so he ran the same cover every year to celebrate the magazine's

birthday. Eventually, everyone at The New

Yorker wanted something different, but no one could think of an appropriate

substitute, so Eustace Tilley reigned on and on until, finally, during Tina

Brown’s editorship, Robert Crumb was

recruited to conjure up a more contemporary version of the Broadway dandy. His

drawing, a Village slacker, broke the mold in 1994. Thereafter, a short flurry

of variations, but Eustace soon returned again. And again.

Another flurry, this time of the

magazine’s cartoonists themselves, occurred last month at Beaver Creek, a ski

resort near Vail, Colorado. The occasion was a seminar called “Humor on the

Slopes.” Ted Alvarez of the Vail Daily

News interviewed several of the inky-fingered participants, including Drew Dernavich, who spoke for millions

of aspiring gag cartoonists when he said The

New Yorker is the pinnacle of magazine cartooning, the highest of the high. “The New Yorker is about cartoons,”

he said; “you want to be in a magazine that sees it as a valid art form.” Most New Yorker cartoonists take years, and

hundreds—perhaps thousands—of submissions before they finally get one

published. But Matthew Diffee won a

contest. “I never intended to be a cartoonist,” he said; “I was regularly doing

art and writing and performing comedy. I didn’t put the two together until I

was 29.”

Like Diffee, Chad Darbyshire (aka C. Covert Darbyshire) honed his comedic

skills through performance and writing for other performers. “I have this

picture in my mind of my tombstone,” Darbyshire said, “—He died but at least he

was in The New Yorker.” Getting

published in The New Yorker was, he

said, “intellectual confirmation because it’s the best magazine in the world.”

Dernavich and Harry Bliss have art

education backgrounds, but Dernavich’s “second career” is carving gravestones.

“If you can think of something that’s completely opposite, I guess that’s

pretty much it.” Curiously, his cartoons look carved—scraped out of linoleum

blocks.

Describing his creative process,

Bliss said: “It’s taken me years to figure out, but, basically, I just start

drawing. Maybe I’ll draw a couple out to dinner; the guy will have a smirk on

his face, and the woman will look sad. I think about what they’ve said before

and what they’ll say after, and I create this narrative—I think of the cartoon as

a frame in a film—and figure out what they’re saying at this particular

moment.” The trick, he said, is to “finish the story.” The single panel cartoon

is, for many cartoonists, “the ultimate expression of visual comedy,” Alvarez

wrote, going on to quote Dernavich: “For the best cartoons, brevity is the soul

of wit, and the shorter and sweeter, the better. If you can get it down to a

single frame, it delivers the best bang for the buck. The premise, the

visual—the joke—all have to happen at the same time, within that single frame.”

The cartoonists enjoy the

interaction they have during the seminar with an audience. “My job is to sit at

a desk and look at a blank piece of paper,” said Dernavich, “so it’s nice to

get out and draw. We assume people laugh at our cartoons, but we never get to

see it. It’s nice to see them laugh and react. Interactive drawing with an

audience, like we do here at Beaver Creek, really brings cartooning out from

behind the desk.”

Bliss agreed. “I enjoy the

spontaneity of just going for it, which comes from improvisation. The older I

get,” he continued, “the more I think about how important laughter is. I have

yet to dissect it fully, but life is tough: it’s tough getting by, and if you

can laugh along the way, it makes everything better.”

Some people, however, just can’t

laugh. In the predominantly Polish neighborhood of Greenpoint, Brooklyn, for

instance, some residents were shocked—shocked!—by a recent New Yorker cartoon by Bob

Weber, according to Joe Babcock in the New

York Daily News.

Fascinating

Footnote. Much of the news

retailed in this segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at http://www.rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John

Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature,

cartoons, bandes dessinees and

related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve

deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and

lore are Mark Evanier’s www.povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s www.DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s www.comicsreporter.com.

And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, http://www.comicsdc.blogspot.com

From

Hilaire Belloc:

From

quiet homes and first beginning,

Out

to the undiscovered ends,

There’s

nothing worth the wear of winning

But

laughter and the love of friends.

Dedicatory Ode

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST

One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis

Miller adv.

Nestled

comfortably in east central Illinois where we are sheltered from the World

Outside by vast acres of soy bean cultivation, I wasn’t aware until quite

recently of the cottage cabal of conspiracy theories about 9/11. I came across

an entire magazine devoted to advocacy of these theories, and one of them gave

me pause. The collapse of the twin towers in New York did, indeed, look suspiciously

like the result of controlled demolition—the buildings’ pancaking, floor upon

floor upon floor, into their own footprints instead of tottering and falling to

one side or the other. When I read that, I remembered thinking as I watched the

tragedy on tv that the collapse of these buildings was much too orderly.

Controlled demolition, of course. But if the buildings were deliberately blown

up, why? The mind boggles, as is its wont, at the fiendish implications.

Conspiracy theorists suffer no boggling whatsoever: they know, immediately,

that the Bush League is up to no good. Much as I loathe Baghdad Bob (“We’re

Winning the War”) Cheney and his trained chimp, I couldn’t swallow that. But

the appearance of controlled demolition—that was suspicious. Then cartooner Jim Ivey sent me pages from a 2006

issue of Skeptic magazine that

allayed my suspicious. This issue, No. 4 of Vol. 12, offers an entire article

that demolishes all of the conspiracy theories, one by one, systematically and

thoroughly. The twin tower demolition is exhaustively examined, but the most

convincing aspect of the argument was the simple assertion that controlled

demolition of buildings begins with the bottom floors, not the top ones. The

pancaking of the twin towers resembles the pancaking of a purposefully

demolished building but only because of the pancaking. “Actual implosion

demolitions always start with the bottom floors. Photo evidence shows the lower

floors of WTC 1 and 2 were intact until destroyed from above.” That’s enough for

me, but there’s more: both towers did not fall into their own

footprints; one of them tipped slightly.

According to The Week magazine, quoting the New

York Times, three 30-minute naps every week have been discovered to reduce

the risk of heart disease by 30 percent. How did they get this number, 30

percent? Ever wonder that when you read these astonishing medical statistics

that are forever cropping up? ...Also from The

Week: Anna Nicole Smith was the 11th Playmate to die before her

50th birthday. ... And again: Hugh Hefner, 80, is getting married

again, for the third time; this time, to Holly Madison, 27, one of his

girlfriends. The wedding will be taped for Hef’s reality tv show. ... And yet

again: A Chinese paraglider died when he was sucked into a storm cloud and

frozen. According to an unnamed tabloid, a member of the Chinese paragliding

team while training in Australia suddenly shot upward at a speed of around 70

fps into a huge black cloud; when a rescue ’copter found his body later, it was

frozen. ... Ray Evans, the lyricist who co-created with Jay Livingston such

hum-able songs as “Mona Lisa,” “Silver Bells,” and “Que Sera, Sera,” died the

last week of February at the age of 92. The title of the Yuletide song “Silver

Bells” was originally “Tinkle Bells” until Livingston’s wife objected,

thinking, perhaps, that “tinkle” suggested toilet training in some vague way.

... In Minnesota, Raymond Snouffer Jr. won $25,000 in the state lottery two

days running, reported The Week—“a

bit of luck that officials said defied ‘incalculable’ odds.” ... And in

California, the same magazine announced, a pediatrician refused to treat a baby

girl with an ear infection because her parents had tattoos. His faith, said Dr.

Gary Merrill, inspires him to enforce certain standards in his medical

practice—“and that means no tattoos, no body piercings, and no chewing gum.”

It’s a comfort to know that the nation is safe again from the attacks of

tattoos, body piercings, and rampant chewing gum.

MORE ART FOR ART’S SAKE

Richard

Corliss, exercising his franchise as art critic at Time, committed a long disquisition on “comics as art” on February

4, ostensibly reviewing the Masters of American Comics exhibition. He begins by

noting that aficionados of the medium have never felt comics enjoyed sufficient

status in the art world, and then he offers a reason for the neglect: “To the

arbiters of 20th century art, comics had plenty of handicaps. It was

printed on disposable paper (hence not worth saving, owning or investing in).

It was popular (the wrong people liked it), American (when high culture was a

European near-monopoly) and, worst of all, funny.” He continues: “This snobbery

still vexes Art Spiegelman. ‘I have

all sorts of issues with the idea that a Lichtenstein painting of a comic book

panel is art but the original comic panel it draws on is not considered art,’

he told Time’s Jeanne McDowell for a

2005 story we did on the exhibition. ‘I hate that whole attitude and way of

looking at this stuff. Lichtenstein did for comics what Warhol did for

Campbell’s Soup? It had nothing to do with comics. It had to do with exploiting

the form without any of the content.” Corliss eventually concludes that comics

don’t belong on a museum wall but not because he dislikes comics; in fact, he

loves comics. But the “museuming of comics,” he says, seems to glorify the

wrong thing—the pictures instead of the writing. Corliss, like too many

critics, thinks the making of comics consists of two distinct creative acts,

drawing and writing, when, as we all know, making comics consists of “writing” by “drawing.” To dramatize his point, Corliss asks whether we’d rather “see (read)

Kurtzman’s Mad or Spiegelman’s Maus illustrated by other artists or

have others write stories for which Kurtzman and Spiegelman provided the

drawings. The first, obviously, because the genius is in the writing.” True.

But, as I said, in making comics, drawing is writing. In any event, Corliss

concludes: “The way to appreciate comic book art is by reading them, in book

form” not on museum walls. ... You don’t need a museum to tell you that this

stuff is great.” Can’t quarrel with that.

But Roy Lichtenstein continues to

lurk, an annoying barb forever lodged in the side of cartooning, the emblem if

not the progenitor of the “comics are art” magpies. He lurks behind a current

exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MOMA). Entitled “Comic

Abstraction: Image-Breaking, Image-Making,” the show displays about 30 works by

13 artists who, as Roberta Smith tells us in The New York Times, “borrow one way or another from comic strips,

cartoons and animation.” The idea behind the show, she goes on, is that “the

lively and essential contamination of abstract art by popular culture that

began with Surrealists ... has greatly expanded during the last 30 years.” The

works on display “use the conventions of comics ‘not to withdraw from reality

but to address perplexing questions about war and global conflicts, the loss of

innocence and racial stereotyping.’ But in the end, the works here are mostly cute,”

Smith finishes, “neat and perfectly pleasant, implying a view of contemporary

art as mildly titillating but basically toothless entertainment.” I watched a

slideshow of some of the pieces online, and I must say that I had to work hard

to see any connection to comics in many of them. One looked like an imitation

Jackson Pollock roil of paint, not a cartoon except, perhaps, in the same way

that all of Pollock is a cartoon, a mockery of painting as an art form. Speech

balloons float across the prospect in a couple samples. In one, they float like

balloons over head. In another, the words have been deleted; ditto, the

pictures, leaving panels of different flat monochromes, sprinkled with blank

speech balloons. They say, in other words, nothing. Says Smith: “They provide

some welcome if relatively pure visual intensity, regardless of what the label

says about the cultural significance of the comics used.” She has little use

for many of MOMA’s recent shows: “Beyond the big solo retrospectives that MOMA

handles with expert aplomb, too many of the museum’s recent exhibitions have a

veneer of political piousness that limits and shortchanges everything—art,

artists, the public and the institution itself.”

But Lichtenstein endures. Last

month, Eddie Campbell wrote online

approvingly of the painter’s comics phase, that period during which

Lichtenstein achieved immortality by painting enlargements of panels from comic

books. “In theory,” said Campbell, “it was like painting a view of a building

or a vase. He worked through a long series of the same kind of thing before

applying the particular treatments he had devised, such as the mechanical dots,

to other kinds of images, ultimately including abstract images as in the

brushstrokes series. I find his whole project quite astonishing and

invigorating. It was good for art. Hell, it was even good for the comic book

medium, setting a precedent for it to be taken seriously.” I don’t know about

that. I’m not sure Lichtenstein was taking comics seriously by making paintings

of them. He seems, rather, to be mocking comics. But why do comics need to be

taken any more seriously than they are? They are read in the nation’s

newspapers every day by millions of people, for most of whom, Charlie Brown is

an intimate friend. That is the ultimate achievement of art, the accolade of

rendering the imaginary real. Like Corliss, I believe the way to best

appreciate the form is to read comics in their native, newsprint habitat, not,

necessarily, on museum walls, where they appear only fleetingly, breeding only

backache as we stand there, reading what we would enjoy better were we sitting

down and turning pages. Yes, it’s good for the cultural status of the medium.

But the social status—the power in status—in this society stems from the money

comics generate for those who do them or who deal in them.

The Lichtenstein folks, meanwhile,

are a bit defensive about the artistic accomplishment of their idol. As

Campbell reports, “On the opening page of their site, an excellent document on

the artist and his life, it says: ‘The contents of this site are for personal

and/or educational use only. Neither text nor photographs may be reproduced in

any form without the permission of the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation,’ and then

you have to click on the ‘I agree’ button” to gain entrance.” It is, as

Campbell says (“smiling at life’s daftness without a hint of indignation”) “one

last irony.” The very stuff of cartoons.

If, by chance, you think

Lichtenstein did much originating of imagery when copying panels from comic

books, visit David Barsalou’s site, http://davidbarsalou.homestead.com/LICHTENSTEINPROJECT.html, where he has

collected 85 of Lichtenstein’s masterpieces, pairing them with their four-color

inspirations. “The [art] critics,” says Barsalou, “are of one mind that

Lichtenstein made major changes, but if you look at the work, he copied them

almost verbatim. Only a few were original.” Jack Cowart, the executive director

of the Lichtenstein Foundation, is not impressed by this sort of reasoning.

“Barsalou is boring to us,” he said, quoted by Alex Beam in the Boston Globe (October 18, 2006). “Roy’s

work was a wonderment of the graphic formulae and the codification of sentiment

that had been worked out by others. Barsalou’s thesis notwithstanding, the

panels were changed in scale, color, treatment, and in their implications.

There is no exact copy.” Well, yes—there is some variation from one to the

other, but the variations are not as consequential as the similarities.

Clearly, Lichtenstein was a bitterly frustrated comic book artist, aspiring to

the fame he was denied in the funnybooks. Which editor turned him away after

pawing through his portfolio of samples? After which, the dejected Lichtenstein

went back to whatever dank basement he was using as a studio, and, like any

yearning young comic book artist, performed his apprenticeship, copying, as

nearly as he could, his favorite comic book artists, panel by panel.

Most copyright attorneys contacted

by Beam believe copyright law has been violated. Perhaps, one lawyer

speculates, there was a private settlement between DC Comics, the source of

most of the inspirational images, and the painter. But it no longer matters:

the statute of limitations for copyright infringement is three years. Russ Heath, one of the DC artists whose

work Lichtenstein appropriated, told Beam that DC was never interested in

suing, probably because there wasn’t much money to be made. “He never even had

me over for a cocktail,” sniffed Heath, “and then he died. So I guess I’m out

of luck.”

Son

of Quips & Quotes

“Dogs come when they’re called. Cats

take a message.” —Mary Bly

“The only statistics you can trust

are those you falsify yourself.” —Winston Churchill

“The man who dies rich, dies

disgraced.” —Andrew Carnegie

“If I gave a shit, you’re the first

person I’d give it to.” —A Nonny Moose

BOOK MARQUEE

Reviewing Travels in the Scriptorium, Paul

Auster’s new novel, his eleventh, Allen Barra in Salon.com wrote that the

puzzlebox-like story is “at times intriguing” but it comes to nothing. It’s

like watching a magician saw a box in half after he’s forgotten to add his

lovely assistant. Now there’s a turn of phrase worth smiling over. ... NBM

Publishing is poised to bring out the first volume of a projected multi-volume

reprinting project with the deluxe, dust-jacketed 192 8x6-inch page hardcover

of Forever Nuts: Classic Screwball

Strips, The Early Years of Mutt & Jeff ($24.95). Starting in the San Francisco Chronicle on November 15,

1907 (this is the centennial of its birth, kimo sabe), Bud Fisher’s Mutt and Jeff was not only the first

successful daily comic strip, it also established the horizontal “strip”

format. Originally featuring just the tall half of the duo and bearing his

name, A. Mutt, the strip aimed at an

adult readership: a racetrack tout, Mutt bet money on a horse that would run

later in the day, and readers had to buy tomorrow’s paper to find out if he

won. Not the sort of comedy children would cherish or, even, understand. With

the daily wager as its initial dynamic, the strip was a continuity feature from

the start, and by the late winter of 1908, the continuity was political satire:

Mutt stands trial for stealing money to bet with, and Fisher takes the occasion

to poke fun at San Francisco politicians and municipal corruption. Mutt is

judged insane and is sent to the local looney bin for a cure; there, he meets a

diminutive nutcase who thinks he’s the prize fighter, Jim Jeffries, and the

classic team was born. It was so popular a team that “Mutt and Jeff” was soon,

and forever after, the phrase we use to refer to the pairing of a tall man and

a short one. With this series, NBM is returning to its roots, in a manner of

speaking: in 1984, it launched the 12-volume hardcover reprinting of Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates, one of the company’s first publishing

endeavors and a historic achievement.

Sometime in the next month or so,

we’ll reprint here the last Mutt and Jeff comic strip, but until that auspicious occasion, we’ll continue to ponder the

puzzle Fisher left us with: What, exactly, is the relationship between Mutt and

Jeff? From the beginning, Mutt had a wife and child, but over the years, we are

prompted to wonder how Jeff fits into this relationship. Some of the daily gags

involve Mutt and his wife or Mutt and his son, Cicero. But Jeff seems always to

be present on the premises, too. Does he live with the Mutts? If so, does he

ever talk to Mrs. Mutt? I can’t remember ever seeing them together in the

strip. Sometimes, I have the impression that Mutt and Jeff are roommates in a

rooming and boarding establishment. Other times, it seems that Jeff lives

alone. But we can’t be sure. Maybe the NBM project will, at last, remove our

doubts and settle the question. Whatever the duo’s living arrangements, they

were doubtless established in the first year or so of the strip, and that, as I

understand it, is the content of the inaugural NBM volume.

BOOK SALE

And

if you haven’t yet browsed our Book Sale, click here to do so.

THE FROTH ESTATE

The Alleged News Institution

Last

fall’s November issue of Editor &

Publisher carried an article reporting on the “widespread clamor to return

newspapers to local ownership.” As we’ve noted here before, very few—maybe only

350-400—of the nation’s 1,500 daily newspapers are owned locally; most are

owned by chains or corporations, all of which trade shares on the stock market.

Investors want a continually increasing return on their investment, but they

don’t get it with newspapers. Newspapers generate the largest profit margin,

usually 20-25%, of any business in the country, but that’s not good enough for

investors who expect a steady growth. So newspapers are constantly being

prodded by their Wall Street proprietors to improve profit, which can be

achieved by two means: increase income and decrease expenditure. In a climate

that sees newspapers losing circulation, slowly but steadily, increasing income

is unlikely; so profit can be improved only by cutting costs. And that usually

means reducing payroll. One of the staff positions being eliminated regularly

in cost-cutting measures is that of editorial cartoonist. We’ve been donning

sack cloth and ashes about that for months. But another big expense for a

newspaper is its comics section. If a paper offers 30 strips a day, that will

cost at least $450 a week, or $23,400 a year. That’s a big hunk, maybe half a

top-salaried editoonist’s salary (or a third, maybe, counting the cost of

benefits). Frankly, I’m surprised that there hasn’t been a sudden boycott of

syndicated comic strips nationwide: cost-cutters are merciless, and the funnies

look frivolous enough to be ripe for cutting. So far, that hasn’t happened.

Knight Ridder, a newspaper chain that sold off all 32 of its papers a year ago,

once suggested to syndicates that subscription fees for comics be reduced or

K-R would drop the strips in all its papers; nothing came of the threat. But

public (that is, Wall Street investor) ownership of newspapers still hovers

over the comics page. So I watch with great interest the flux of financial

affairs in the newspaper industry.

Lately, many observers have opined

that if newspapers were locally owned, the constant pressure to improve on the

20% profit margin would be eased, and newspapers could go back to committing

journalism again—reporting the news in the sort of depth and breadth that makes

readers informed citizens. The article in November’s E&P by Mark Fitzgerald and Jennifer Saba constitutes a major

cheer-leading exercise for local ownership. They concede that local ownership

doesn’t necessarily produce good newspapering, quoting an analyst who said:

“Some of the worst newspapers in the country were owned locally. They were

beholden to local establishments and sacred cows. A lot of that has gone away

with chain ownership.” But Fitzgerald and Saba pretty consistently tout the

“great collective pining for the old age of family or independent newspaper

ownership,” saying the “widespread clamor ... represents a dramatic change in

course.” Well, yes and no.

Yes, a small number of major papers

have escaped the clutches of The Street and are now owned by consortia of local

entrepreneurs. The Philadelphia Inquirer and

the Philadelphia Daily News, both

purchased by McClatchy Company when it bought all the other Knight Ridder

papers, were quickly purchased when McClatchy offered them for sale. Viewed as

“dogs” by The Street, they were snapped up by local investors. McClatchy also

sold one of the papers it owned before the K-R acquisition, the largest in the

McClatchy chain, the Minneapolis Star

Tribune, to a private equity firm, seeking a tax advantage. Local

billionaires are eyeing the Los Angeles

Times, the Baltimore Sun, and the Hartford Courant, all part of the

Tribune Company’s chain, and the Tribune Company is being pressured to make

more money than these papers seem capable of, so it might sell some, or all, of

them. In these developments, Fitzgerald and Saba evidently expect us to see a

happier future for daily newspapers. It isn’t until the twelfth paragraph of

the article that we read “the movement to local ownership is more talk than

trend.” And then, a page or so later, we meet some locally owned newspapers

that have turned into financial disasters for their owners.

So, no—a dramatic change is not yet

underway. We may hope for it, and local ownership, even with its penchant for

being protective of the indigenous bovine population, is probably healthier for

newspapers than public ownership. With less investor pressure for increased

profits, the comics pages of locally owned newspapers are likely safer than

those of papers owned by The Street. But local ownership is not yet a trend,

alas; and what local ownership exists is threatened by the changing information

environment: newspapers have yet to figure out how to make maximum use of the

Internet. And until they do, newspapers will continue to be the steadily

slumping behemoths of yesteryear, slouching inexorably toward an ever

diminishing bottom line.

Out

Among the Unimportant

“A hospital bed is a parked taxi

with the meter running.” —Groucho Marx

The world’s record for keeping a

Lifesaver in the mouth with the hole intact is 7 hours and 10 minutes.—The Bathroom Trivia Almanac

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE

A

few extracts from the notebook at my elbow when I’m reading recent comic books. Cross Bronx ended its 4-issue run,

leaving me just about as baffled as I’d been at the beginning. Dubbed a

“supernatural police drama,” Michael

Avon Oeming’s story starts promisingly enough with a murder committed with

a dead cop’s gun, and when the protagonist visits the widow, exploring possible

explanations, he encounters a woman understandably bitter because her dancer

daughter was raped and disabled. In the end, a spectral young woman shows up

and avenges all the wrongs done. Is she the “ghost” of the dead raped girl? High

in suspense but obscure, like most tales of the supernatural, which phenomena

never require any explanation or logic. Keeps you turning the pages, though,

and Ivan Brandon’s art is a moody

chiaroscuro treat.

Lone

Ranger Nos. 2-3 gives us more of Sergio

Carriello’s superior painterly art. In these issues, Collins, who led the

rangers into the ambush that, eventually, resulted in the “lone” survivor, is

killed by a mysterious black man, who then kills Mrs. Abrams, and the Lone

Ranger acquires a mask. ... The last of the 4-issue series Sable and Fortune has arrived, after what seems to me a long delay,

caused, perhaps, by John Burns’ departure from the title. Maybe the delay is a figment of my imagination

brought to the surface by a fetid filing system. But the virtuoso Burns is

definitely gone. The tidy linear mannerisms of his successor, Laurenn McCubbins, are scarcely an

adequate substitute for the bravura performance Burns gave, and so it all seems

to end with a whimper, not a bang, which is partly writer Brendan Cahill’s fault, but Burns’ absence doesn’t help:

presumably, his panache with colors could have rescued the otherwise pale tale.

... Speaking of delightful stylistic treatments, we have Chris Sprouse on the 2-issue special of ExMachina, a pleasure to watch. And Brian K. Vaughan’s story offers a challenging conundrum: his hero

is forced to kill the bad guy but he doesn’t believe in the death penalty.

Jonah

Hex Nos. 13-15 is drawn by Jordi

Bernet, one of my favorite inkslingers. His style—crudely, nicely, blunt

and thorny with heavy-handed feathering—suits the subject admirably. It is a

little too cryptic to catch the grisly horror of Hex’s right eye and peeled

visage, but it catches the energy in action sequences with great verve.

Bernet’s evocation of the locale and ambiance is convincing and confident, and

the opening sequence in No. 13, with soldiers getting shot as they sit around a

campfire at night, is expertly achieved in both action and atmosphere. But the

story by Justin Gray and Jimmy Palmiotti is a trifle confused,

seems to me. Or maybe it’s me that’s confused. Ostensibly, this is Hex’s origin

story: we learn how he acquired his facial scarring, but the storyline flips

back and forth between two (or maybe three) time periods, and the sequence is

difficult to reconstruct. His eye is damaged, it seems, when he is whipped

while in the Confederate army in September 1862. Yet when he returns to the

Apache tribe he grew up in after the war, his face seems entirely unblemished;

it’s during the ensuing fight with a tribal rival that he’s burned with a hot

iron tomahawk, scarring his face. So which is it? The whipping or the tomahawk?

Some

of the 1,911 Best Things Anybody Ever Said

“The advantage of the emotions is

that they lead us astray.” —Oscar Wilde

“Wagner’s music is better than it

sounds.” —Bill Nye

“Nothing is said that has not been

said before.” —Terrence

REPRINZ

Brian Crane’s Pickles, a strip about the senior members of a family

surrounded by two generations of their offspring, has been hovering on the

newspaper horizon since 1990, when, at the age of 40, Crane, a commercial

artist in advertising, started thumbing through his sketchbook in search of

characters for a comic strip. He was also pondering the milieu for a comic

strip. “I didn’t see any senior citizens as the focus of comics and thought

people could relate to that,” Crane said last fall in an interview with Jarid

Shipley of the Nevada Appeal. “I see

similarities with my family and neighbors. When I started, I didn’t think I’d

get syndicated. When I did, I didn’t think it would be popular, so my

expectations have always been pretty low.” His tactic has apparently paid off. Pickles was named Best Comic Strip of

2001 by the National Cartoonists Society, and the strip is now in more than 500

newspapers, nationwide—a more than healthy circulation.

The members of Crane’s cast include

Earl and Opal Pickles, the elderly couple, and their daughter Sylvia and her

husband Dan, and their son Nelson, plus a somewhat obtuse dog named Roscoe and

a sly cat named Muffin. In recent years, the strip has focused more on Earl and

Opal than on the rest of the ensemble. Earl, we quickly realize, has only one

hobby—annoying his wife. And Opal, although a devoted wife, dotes on Muffin, so

don’t ask her to choose between Earl and the cat. Nelson shows up fairly often,

seeking wisdom at his grandfather’s knee. Still

Pickled after All These Years (128 8x9-inch pages; paperback, $10.95) is

Andrew McMeel’s 2004 collection of the strip and the whole cast is on display

herein. Sylvia, reacting to the news that her mother and father are going to

visit Grand Canyon, says to Opal: “I’ve heard it’s breathtaking.” “Oh, yes,”

says Opal, who is working at the ironing board. “It’s one of the three sights I

want to see before I die. The others are the pyramids of Egypt and your father

ironing his own pants.” On another occasion, Earl is out walking and runs into

his friend Clyde. Earl is holding a dog leash and Clyde asks him why. “Good

question,” says Earl. “I was just trying to figure that out myself. I must be

having a senior moment,” he continues, holding the leash up for closer

inspection, “—I can’t remember if I found a leash or lost a dog.” This compilation regales us with Opal’s pursuit of a writing career.

She writes a children’s book and then gives it to

More

of the Same

Recipe (in its entirety) for boiled

owl: Take feathers off. Clean owl and put in cooking pot with lots of water.

Add salt to taste. —The Eskimo Cookbook (1952)

“Punctuality is the thief of time.”

—Oscar Wilde again

“Platitudes are the Sundays of

stupidity.” —Unknown

“Never eat more than you can lift.”

—Miss Piggy

EDITOONERY

After 21 years with the Colorado Springs Gazette, staff editorial cartoonist Chuck Asay announced his retirement on Friday, March 2. His retirement was part of a general cutback on staff: the paper slashed 33 positions, Editor & Publisher reported, leaving 475 full-time staffers. Although the reduction seems a little drastic, 10 of the 33 positions being eliminated were “empty,” unfilled job descriptions. But not the editoon slot: it was more than filled. Asay drew charming and profusely elaborated albeit simple funny pictures that were both vintage and modern in style and appearance, and he specialized in multi-panel format—comic strips—for his cartoon commentary. He is such a staunch conservative that I very often couldn’t decipher his cartoons: From his undeviating endorsement of conservative positions, I knew what his opinion was in a general way, but the specific point he was making in a particular cartoon was sometimes obscure.

Take, for example, one of those

displayed here—in which one of his favorite characters, Lara Liberal, is protecting

the children from exposure to various dangers. It’s clear to me that Asay

thinks liberal attitudes about such things as “secondary smoke and asbestos”

result in extreme measures—laughably extreme—but how Iran’s nuclear ambitions

fit into the same series as global warming and prayer in schools is not so

clear. Does he mean that liberal attitudes toward Iran encourage jihad? How? If

we assume that the liberal position on Iran’s nukes is to let them be, then

maybe the last panel fits. But is that, really, the liberal position? Liberals

see danger from secondary smoke but not from nuke-wielding rogue states? Is

advocating negotiating with Iran somehow the equivalent of suppressing

religious speech? I don’t see the connection, but Asay’s sequence suggests

there is one.

Is he saying that talking to our

foes is wrong? Misguided? Foolish? I don’t agree that we shouldn’t talk to our

enemies, the traditional Bush League chant until recently. I think when we

withdrew from active involvement in the Israeli-Palestinian crisis as soon as

Darth Cheney came to power, we hastened the day that the U.S. would be

attacked, the day we now date September 11. Not talking to one’s enemies does

not, ipso facto, provoke them into behaving better in order to have a conversation

with us; instead, it heightens the resentment they already feel. I suppose the

problem is me, not Asay: I’m so liberal that I can’t get into the right frame

of mind to even understand a conservative attitude. Compounding the difficulty

for me might be the Biblical element. After an early career as a school teacher

at the Taos Pueblo in New Mexico, where he sharpened his drawing skills by

caricaturing tourists in the Taos plaza, Asay “found God,” as his editor put

it, a discovery that influenced his political as well as his spiritual posture.

And Asay himself once allowed that his “biblical worldview” on the issues of

the day made his cartoons different. I can’t discern a biblical aspect in the

cartoon I’m examining, but then, that may be another instance of myopia caused

by a deviant view. Dunno.

In any case, I have always admired

Asay’s drawings whether I understood his point of view or not, and I’m sorry to

think that we may see less of them. He’s still syndicated by Creators, but

whether he’ll do as much work now without a daily deadline remains to be seen.

It’s not clear whether Asay’s retirement was encouraged as part of the paper’s

over-all staff reduction; but it’s not likely that the staff cartoonist

position will be retained. The position was part of the budget; the cartoonist

was part of the staff. Asay’s editor at the Gazette bid the cartoonist a fond and personally heartfelt adieu: “Saying Chuck will be

missed is too trite. His departure leaves a hole in the heart of this page and

this newspaper.” And it leaves editor Sean Paige sadder, clearly. You can read

the whole thing, which I recommend, at http://www.gazette.com/onset?id=19782&template=article.html.

In September, Tom Toles, the editorial cartoonist at the Washington Post, went back to his former hometown, Buffalo, New

York, where he gave a talk about censorship and was interviewed by Geoff Kelly

of artvoice.com. Saying he often draws cartoons about censorship, Toles

referred to one he did about “a revived threat” from the Attorney General to

prosecute journalists for “receiving” classified information, an outrageous

prospect. Said Toles: “I took that one step further and said that anyone

reading a newspaper is receiving classified information.” He also lambasted the

White House for paying journalists to write flattering stories. “It gets to the

constellation of government control of information or manipulation of

information,” said Toles. “While not strictly in the narrowest sense

censorship, it’s a related danger.” Has he ever been censored? Yes, once, Toles

confessed—and it was while he was working at the Buffalo News. He intended to take to task a prominent local

non-governmental person, and his editor felt it was an unfair criticism. Toles

was, he said, “more-or-less outraged because more-or-less my agreement with the

last three newspapers I worked for has been that I will not be edited for

content grounds, but only [for] taste and libel.” Generally speaking, American

political cartoonists these days are pretty content with their situations,

Toles believes. “If you polled them right now, you would find a very high

degree of satisfaction in the amount of latitude that they are ordinarily

given.” But they are still not quite as free to express themselves as Toles

thinks he is. Working in the nation’s capital as opposed to Buffalo gives a

cartoonist “a highly different sense of what’s going on,” he said. You also

have “an audience that is eagerly attuned to all of this inside baseball. I’ve

likened it to sitting in the front row of the movie theater. It’s good and bad

in all the same ways: you can see the nostril hairs here much more clearly, but

there is a certain distortion that comes with being so close.” And the social

network adds another level of distortion. “So many people here know so many of

the other people involved so well that sometimes, I think, objectivity suffers.

There comes to be a language with which issues are spoken of. It’s a

circumscribed language in that certain points of view just aren’t represented.”

At the Dayton Daily News in Ohio, you can write a Mike Peters’ editorial cartoon. Sort of. (As I’ve said before, in

cartooning “writing” is “drawing”; so this exercise, as you’ll see, is not

quite either. But it sounds fun.) “Open Mike” is a blog feature at http://www.daytondailynews.com/o/content/opinion/peters/openmike/

; staff editoonist Peters draws a picture (called a “cartoon” even though it

makes no sense by itself without a caption or any other verbiage), and readers

are invited to supply words for the speech balloon. Contenders’ submissions are

published at the site, and a winner is declared every so often. The winner gets

the original art for the cartoon.

SIGNS OF THE ZODIAC

The

first letter signed by the Zodiac, the serial killer who terrorized the San

Francisco Bay Area for several years, was sent July 31, 1969; the last, July 8,

1974. The Zodiac may have begun his spree earlier—on October 30, 1966—with

Cheri Jo Bates, who was found with her throat slit and nearly decapitated in

the parking lot of Riverside City College’s library annex. A letter from

someone claiming to be her murderer was mailed to the police and the local

newspaper a month later, but the letter wasn’t signed. The Zodiac sent at least

18 letters and claimed 37 victims, but the police are sure of only seven. The

Zodiac was never caught, although some associated with the case believe one of

the 2,500 suspects interviewed, Arthur Leigh Allen, was the perpetrator; he

died several years ago. Two exhaustive books have been written about the case: Zodiac and Zodiac Unleashed. Both are still in print; the former in its 39th printing, the latter in its seventh edition. Both were written by the same man, Robert Graysmith, who was, at the

time of the murders, working at the San

Francisco Chronicle as the staff political cartoonist. In the movie

“Zodiac,” released March 2 and based upon Graysmith’s books, Graysmith is one

of the four men who become obsessed with finding the illusive killer, whose

communiques were often coded in cryptic symbols. Another of the four was

“supercop” Dave Toschi, who, Graysmith says, was the model for Clint Eastwood’s

Dirty Harry. The other two of the quartet were Toschi’s assistant, William

Armstrong, and the Chronicle’s reporter on the case, Paul Avery.

Graysmith had graduated in 1960 from

Yamato High School in Japan, where he’d worked as a sports cartoonist and

illustrator on a local paper. He earned a B.A. in fine arts at California

College in Oakland, worked as a sports cartoonist and staff artist at the Oakland Tribune for a year or so, then

in somewhat the same capacity for the Stockton

Record before landing at the Chronicle, where he remained for twenty years, nominated by the paper for a Pulitzer six

times. According to Emanuel Levy at his website, Graysmith became a diligent

investigative reporter in pursuing his interest in unsolved crimes. After the

success of Zodiac, Graysmith left

cartooning and devoted himself to a writing career, producing six true crime

volumes, including The Murder of Bob

Crane about the unresolved homicide of “Hogan’s Heroes” tv sitcom star.

Interviewed recently by Kim Voynar

at cinematical.com, Graysmith acknowledged that he was scarcely an

investigative journalist when he became involved with the Zodiac murders. “I

wasn’t even a writer!” he exclaimed. “I was a political cartoonist. I wanted to

have a career as a painter and a sculptor. All the really great American

painters were also all newspaper artists. And the thing about a newspaper

artist is you have to be fast and work on deadline and still be good. Back in

those days, they’d send you out—There’s a parade! Go draw it, quick! That’s how

they did it in those days. But you could afflict the comfortable and comfort

the afflicted [citing the creed of political cartoonists]: you could change the

world—get a bill overthrown, get a bad guy kicked out of office. You really

could make a difference with a picture [cartoon].

“So then,” he continued, “Carol

Fisher, who was our long-suffering letters-to-the-editor person, brings in

these letters. She was just always in the midst of it. And I saw the Zodiac

letter, and I was really drawn to the symbols. And he was very artistic. He did

this one, a 320-character cipher that was perfectly aligned, with no ruler

marks, and it was perfect. They guy who did that had a light table, a t-square,

drafting materials. Basically, he’s doing cartoons and symbols. See, he’s

trying to scare us with symbols, and I’m trying to fix things with symbols [as

a political cartoonist]. And there were all these police jurisdictions and

nobody was cooperating. And so I got the idea—I’ll make this book that has the

effect of a Zodiac was published in 1976. It didn’t solve the case. But it changed Graysmith’s

career. Here are some of Graysmith’s cartoons from the late 1970s, before he’d

left the field.

COMIC STRIP WATCH

Eduardo Barreto is back on Judge Parker and is doing spectacular work. Here’s the release for March 1: lookit all that drawing in the first panel. No wonder he went for the portrait of an eyeball in the last panel: he’d already spent a couple days on the strip by then. ...

And while you’re admiring Barreto’s energy and

craftsmanship, take a look at the two Get

Fuzzys from Darby Conley. In the

first, Bucky gives us a punchline in every panel; George McManus used to do the same sort of thing in his classic Bringing Up Father: Jiggs would have a

comic reaction in every panel to something his wife Maggie was saying. And in the other GF, ponder for the nonce the numerous actions in the first panel: