|

WHAT

JACK KIRBY DID We all call him the King, the King of Comics. But why? What did Jack Kirby do, exactly—precisely—that earned him this highest of accolades? Lest we forget—and for those who may not know—let me offer the following recollection and appreciation. Kirby

was there at the beginning, at the dawn of comic book time. And he

remained an active and powerful creative force until he retired in

the late 1970s. At the beginning, he shaped the art of comic book

narrative more dramatically than most of his contemporaries; and

midway in his course, he almost single-handedly revitalized a

withering medium. That's what Jack Kirby did. That's the short of it. But to understand the import of these bald assertions, we need to see Kirby in the context of the history of the medium. Few saw the unique storytelling potential of the comic book at first. Initially, comic books merely reprinted newspaper strips, cutting them up and rearranging them in page format. It was a good way to make a fast buck; but it was scarcely art. Perhaps the first to see greater potential in the comic book format was a former cavalry officer turned adventure story writer, Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson. Beginning with New Fun (cover-dated February 1935), he published several comic book titles, some of which printed stories that had been produced expressly for his publications. Much of this material was created by the first comic art "shop," which had been set up in the summer of 1936 by a far-sighted entrepreneur named Harry "A" Chesler. The "shop" was a comic book factory, an assembly-line of writers and artists who worked cheaply and quickly to produce stories. Other fresh material came in over the transom. Among these unsolicited stories were several continuing features created by a couple of young men in Cleveland, Ohio. Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster had met while in high school, and after discovering a common interest in comics and science fiction, they decided to collaborate, Siegel writing stories and Shuster drawing them. After graduation from high school in 1932, together they produced several comic strips which they peddled to syndicates without success. Many of the features in earliest issues of Nicholson's comic books looked like rejected Sunday comic strips, and the first Siegel and Shuster effort the Major published may have been one of the team's attempts at newspaper syndication. This was “Doctor Occult,” and it appeared in New Fun No. 6 (October 1935). Siegel and Shuster were twenty-one years old at the time. Two-and-a-half years later, the Cleveland duo was still cranking out material, and they sold another of their failed newspaper strips to the publisher who had inherited Nicholson's nearly abortive comic book empire. This creation was Superman, and, as everyone knows, it transformed the infant comic book industry. Superman sold comic books better than anything else had. And when Batman was introduced a year later, the long underwear league was launched. The floodgates opened, and a host of heroes in colorful tights began cavorting across the four-color pages of comic book after comic book as publishers sought to cash-in on the new formula. Comic books that simply reprinted newspaper comic strips were soon in a minority. All at once, there was a voracious demand for stories and characters created exclusively for comic books. Much of the earliest original material for comic books ignored the special character of the medium. Narrative breakdown was governed by verbal content rather than story momentum. In many of the stories, there was only sporadic visual continuity from panel to panel; instead, each panel illustrated some aspect of the story, and captions carried the narrative along. In visual terms, a story might be a series of illustrations often so independent of one another as to be virtually isolated pictorial incidents—in narrative sequence, admittedly, but without connective continuity. Page layout was wholly undistinguished and, indeed, virtually purposeless. Comic book artists imitated what they saw in the Sunday funnies of their newspapers and designed pages with uniform grids of equal-sized panels, ignoring the spacious page format that would have allowed them to vary the size—both height and width—of panels for emphasis. Among the first to see a greater potential for the medium were Will Eisner and Jack Kirby. Preoccupied with the short story form, Eisner saw that visual images could be manipulated to create mood and should be carefully timed for narrative impact; but that's another story. Kirby saw, perhaps as a result of having worked briefly in animation as an in-betweener, that the potential for portraying action in comic books was not being much exploited. "Nothing around really moved," Kirby once said, recalling his early days. "I created the follow-up action which none of the strips had. In other words, another strip might have one action in one panel and an unrelated action in another panel, whereas I would have a continuous slug fight. If a guy parried, he would follow it up with a thrust. ... So it would give the strip a little motion." A little motion. With typical understatement, Kirby modestly avoided the spotlight. His modesty was ingrained. It had its origins in the ethnic and economic insecurities of New York's Lower East Side ghetto, where Kirby had been born Jacob Kurtzburg. Moreover, as a somewhat short man, Kirby always felt people overlooked him. When he teamed up with Joe Simon in 1940, Simon emerged at once as the front man, the business manager. "Joe's function was to associate with the publishers," Kirby told Will Eisner in an interview in July 1982. "He was 6' 3" and I was 5' 4"," he laughed. "The publishers would not look at me, and I took that in stride. ... [But] Joe was highly visible." Although he influenced the art of the comic book enormously, Kirby, in contrast to Eisner, did not ponder much the artistic import of what he did. He saw himself as an entertainer. "I'm in show business," he told Eisner. "I'm a performer, and I'm going to be the best performer I can." Trying to be the best got him out of the ghetto. While a teenager, he drew cartoons for a mimeograph newspaper produced by the Boy's Brotherhood Republic, a youth organization founded in 1932 by Harry Slonaker to give boys the kind of responsibility that would give them hope in those Depression years. His drawing talent surfaced early, and he soon used it to generate income for his family: he quit high school in 1934 at the beginning of his senior year, and by the following spring, he was working in Max Fleischer's animation studio. As an in-betweener, Kirby drew the sequences of pictures between "key" drawings. His drawings took a character's movement from one position to the next, thus conveying the impression of continuous motion. It was like factory work, and he didn't much like it, but it brought in a paycheck for almost two years until he found a position with Lincoln Features Syndicate, a small operation for which he drew the entire array of newspaper cartoons—editorial cartoons, comic strips, single panel information features—each in a different style. Kirby freelanced with other small syndicates, too, including Eisner and Iger's Universal Phoenix Syndicate, for which, starting in the spring of 1938, he drew several strips. Three of them were subsequently published in Jumbo Comics, a Fiction House title for which the Eisner-Iger Shop began producing material that summer. At the end of 1939, Kirby started doing comics for Victor Fox, and there he met Joe Simon. A

couple years older than Kirby, Simon had attended college and had

worked on the art staffs of a couple newspapers, where he also did

some sports and editorial cartoons. About 1938, he got involved with

comic books, doing some freelance work for the Jacquet Shop and then

for Martin Goodman's Timely comic books. A few months after Kirby

started working for Fox, Simon joined the company as editor-in-chief

of the comic book line, continuing to freelance on the side. He

recognized Kirby's talent immediately, and when Kirby, knowing of

Simon's extramural endeavors, asked if he had any work he could help

with in the evenings, Simon leaped at the opportunity. They worked

together on the second issue of Blue

Bolt (cover-dated

July 1940); it was the first collaboration of what became the most

celebrated creative team in comics. Initially, the two worked together quite closely in producing pages of story. "Jack had a great flair for comics," Simon recalled in his autobiography, The Comic Book Makers. "He could take an ordinary script and make it come alive with his dramatic interpretation. I would write the script on the [illustration] boards as we went along, sketch in rough layouts and notations, and Jack would follow up by doing more exact penciling." Simon then lettered the balloons and inked the drawings, using a brush to make it go faster. ("Brush work dried faster than pen," he explained.) Sometimes Kirby inked, too, depending upon the demands of their production schedules. And sometimes he even re-inked pages that Simon had done, fussing with this effect or that. But he didn't like inking his own drawings: "If I ink it," he once said, "I would be drawing that picture all over again for no reason at all." Eventually, Kirby, having absorbed Simon's distinctive layout skills, took over most of the actual story production, plotting the story and penciling both script and pictures on the pages. Simon concentrated on the business aspects of their partnership; he was the business manager and the salesman, knocking on publishers' doors to get work. Simon inked when he could, but often, they hired other artists to finish Kirby's work. Late in 1940, the team created the first of dozens of characters for which they are renowned. Captain America. The character was more than simply famous. In his history of the medium, Jim Steranko put it this way: "If Superman and Batman were the foundations of the business, Captain America formed the cornerstone of the industry." Captain America was a superpowered patriot, and the times were right. Most informed Americans knew the country was headed for a show-down with Hitler's Nazi Germany sooner or later. "We weren't at war yet, but everybody knew it was coming," Kirby remembered. "That's why Captain America was born. America needed a superpatriot." The costume he and Simon devised stressed their purpose: "Drape the flag on anything, and it looks good," Kirby said. "We gave him a chain mail shirt and a shield, like a modern-day crusader. ... He symbolized America." In

recent years, Simon unearthed his sketch of Captain America, claiming

it was the first to display the character in his full red, white and

blue regalia. Germany was widely suspected of having infiltrated the U.S. to sabotage manufacturing and transportation and communications. Captain America's first assignments involved battling saboteurs and fifth columnists; later, he would take on virtually the entire German army. Or so it seemed. The impact of this new comic book upon other comic book artists was immediate and lasting. Captain America No. 1 (cover-dated March 1941 but hitting the newsstands December 20, 1940) burst on the scene like a skyrocket, illuminating possibilities until then scarcely dreamed of. Although it was the energy of his compositions that distinguished his work from most other comic book productions, Kirby was also a better artist than many of the worn-out hacks or aspiring young amateurs then scratching out stories. His command of human anatomy, for instance, was thorough and sure; as a result, he could draw the spandex-clad characters with real conviction from any angle the action demanded. And there was plenty of action. In

arranging for action to be much more continuous from panel to panel

during fight sequences, Kirby said he "choreographed" those

sequences as if they were ballets, creating what Gil

Kane called "lyric violence."

To emphasize the energetic movement of his characters, Kirby said,

"I tore my characters out of the panels. I made them jump all

over the page." His characters seem to ignore the panels, their

limbs extending beyond the border lines. His figure drawings reek

body English: they are contorted to emphasize movement, power,

action. Even when simply poised for action, they seem tensely coiled

in readiness. In contrast to most comic book superhero action sequences of the day, Kirby's drawings radiate with exaggerated movement. When Captain America strikes a foe on the jaw, Kirby drew the victim bent over backward, his feet lifted off the ground by the force of the blow. The point of the blow's impact is indicated with a star-burst of lines; the course of Captain America's fist, by an arc of parallel speed lines, the sweep of the arc emphasizing, again, the power of his clout. Kirby deployed the visual resources of the medium for effect; others tried for photographic fidelity to nature. To persuade us of the reality of their superheroes, they drew realistically. In so doing, they failed to convey any sense of energetic action. In a realistically depicted fist-fight, a person struck a blow to the jaw does not leap backwards as Kirby's characters do; instead, his head jerks back and his body crumples to the ground. Artists aiming for realism would show the punched-out party mildly disarranged by the blow, his head turned to one side, say, or tilted backward. But in depicting the crucial instant, the instant immediately after the blow is struck, they drew the body still erect—beginning to sag into unconsciousness, perhaps, but scarcely flipping heels over head. And there's not much visual excitement in a picture of a crumpling body. But when Kirby showed Captain America striking a blow for freedom, the foul fellow he hits is flung rearward across a page-wide panel, the narrow dimension of the panel underscoring with its shape the force of the blow. Kirby multiplied the effect of his technique by putting Captain America and his young sidekick Bucky into combat with dozens of opponents at once. These scenes are mobbed with tumbling bodies, careening off furniture or into panel borders, and Cap and Bucky seem wading in disabled foes, up to their knees—even waists—in collapsed bodies. And the fights go on for a page at a time; in other comic books, the fights last only a panel or two. Often, Kirby depicted his characters coming directly at the reader, bursting out of the page. Suddenly, you are face-to-face with the action. You are in it. Kirby systematically sought ways to avoid monotonous drawings: "I would tip the perspective of a room to make it less static," he said. He also shifted camera angles rapidly, selecting the most dramatic perspective for his pictures: a racing automobile, seen from under the front bumper, becomes a rocket, blasting ahead at full throttle, the thrust of the distorted perspective emphasizing the direction and speed of movement. Simon's page layouts add to the impression of vigorous movement. The panels are irregularly shaped, the shapes often echoing actions depicted in them. The panels of most other superhero comic books march across the pages in hypnotically regular cadence—every panel the same size, all arranged in uniform tiers. And within the panels, the action is usually seen from the same staid straight-on angle, panel after panel, and often from the same distance. The monotony is stunning. And the contrast to the Simon and Kirby pages is vivid. As strikingly different as Kirby's visual techniques appeared to his contemporaries in early l941, his impact upon the way superheroes would be depicted henceforth resulted probably as much from the popularity of Captain America as it did from the power of the artist's style. Although there were few other artists in comics who could match Kirby's skill, there were some— Jack Burnley on Starman, for instance, and Crieg Flessel on the Sandman and Lou Fine on the Black Condor. But none of these artists were doing a hero in red-white-and-blue pitted against the looming Axis from across the Atlantic. Kirby's character was pitched to the needs of the hour. In that time of national crisis and overheated passions, the superpatriot captured an audience immediately. Simon and Kirby did the first ten issues of Captain America, and because of the immense popularity of the title, their work was highly visible. That visibility over almost a year guaranteed Kirby's pace-setting work would be seen by his peers. And once they saw it, they could not help but imitate it: the excitement of Kirby's art is simply too persuasive. "Suddenly, after Captain America," Steranko wrote, "came a platoon of red, white, and blue spangled superheroes: American Avenger, American Crusader, American Eagle, Commando Yank, Fighting Yank; in stars and stripes, Yank and Doodle, Yankee Boy, Yankee Eagle, Yankee Doodle Jones, the Liberator, the Sentinel, the Scarlet Sentry, Flagman; in the same military moniker--Captain Flag, Captain Freedom, Captain Courageous, Captain Glory, Captain Red Cross, Captain Valiant, Captain Victory." Captain America set a new standard for the way comic book stories should be told, too. Superhero comic books that were produced after Captain America appeared were drawn differently. Some of the less skilled artists imitated Kirby clumsily and so seemed unaffected by his work. But the competent artists enlivened the action of their pages considerably in the Kirby manner. At about this time, another cartoonist had begun to exert influence upon the artists who rendered superheroic adventure. Burne Hogarth, who had inherited the Sunday Tarzan strip after Hal Foster left in 1937, was drawing the human figure with such minute attention to musculature that his characters seemed flayed of the first couple layers of skin. This treatment gave dramatic emphasis to the actions being depicted: Hogath's characters, their muscles shown in bold relief, appeared to strain with the effort of their endeavors. The effect was to add visually a physical intensity to the drama of the narrative. Thanks to Superman and to artists following Kirby's lead, comic books in the late thirties and through the forties became the province of superheroes. Under the spell of artists like Hogarth and Lou Fine (to name the artist from the Eisner-Iger Shop who was perhaps the finest figure artist to work in comic books in the early years), superhero comic books were showcases for figure drawing. And in depicting as vigorously and continuously as possible the physical action associated with superheroes, the medium began to achieve something of its distinctive potential. Superheroes and comic books were made for each other. In symbionic reciprocity, they contributed to each other's success. Superheroes in comics sparked a demand for comics—and that demand created the need for original superhero material, written and drawn expressly for the medium. Comic books were the ideal medium for portraying the exploits of super beings. They were nearly the only medium at the time. You could write about superheroes in novels, or you could film their adventures. But neither books nor movies were quite up to the task of depicting superheroes' impossible feats. Books lacked the conviction, the authority and impact, of visuals. And in the movies, the incredible deeds of superheroes looked phony: the movie technology of the day had not yet developed the sophisticated special effects necessary for giving the celluloid images the authentic feel of actuality. But in comic books, the pictures made superheroics both palpable and probable. At the time, the adventures of Superman, Captain America, Captain Marvel and their ilk could be recounted only in comics because only in comics could such antics be imbued with sufficient illusion of reality to make the stories convincing. And Jack Kirby had shown, better than anyone else, how to do it. But that's not all Jack Kirby did. There's a second chapter. Superheroes seemed to fall out of favor somewhat in the years immediately after World War II. Many of the wartime superheroes had been superpatriots in the Captain America mold; without the War to fight—without the super villainies of the Nazis and the Japanese—readers doubtless felt no psychological craving for that kind of champion. Whatever the cause, the number of superhero titles declined sharply in the postwar years. At the same time, publishers were clamoring for comic book material. Wartime paper allotments had stemmed expansion during the hostilities; now paper was again available, and the publishers wanted to cash in. Although superhero titles continued to be produced, comic book makers began concentrating their efforts on other subjects that promised to generate greater sales. The search for new best-sellers resulted for a time in a great variety of comic book titles. Publishers floated trial balloons all over the horizon, concentrating first on one subject, then on another. And when one type of comic book seemed successful, everyone jumped on the bandwagon and produced a parade of similar titles. Humorous comic books featured the antics of teenagers and animals; Westerns and stories of cops and robbers received serious treatment. As the decade drew to a close, romance and crime comics began to dominate the newsstands. Simon and Kirby inaugurated the romance comic book genre with their Young Romance in the summer of 1947 (cover-dated September-October). The idea had its seeds in the humorous comics about teenagers, who were always contending with members of the opposite sex. The Simon-Kirby innovation was to treat romance seriously; their stories were told in the first person by one of the principals in manner of a "true confession" (to invoke the name of one of the popular magazines of the day). The pacesetter for the crime titles was undeniably Lev Gleason's Crime Does Not Pay. Observing the newsstands loaded with magazines like True Detective, Official Detective and Master Detective, Gleason decided to start a comic book of "true stories" of criminals. Edited by Charles Biro, the first issue appeared in the spring of 1942. It sold well from the first, and as the decade drew to a close, it was an industry leader. Under Biro's guiding hand (initially, he drew the stories as well as writing them), the books emphasized characterization, and the stories had a strong moral thread stitched into their fabric. In fashioning his "true stories," Biro focussed on individual criminals, and in tracing their lives of crime, he showed not only how they became crooks but what undesirable human beings they became in consequence. The moral lesson was implicit in the career of the criminal—in his increasing depravity—as well as in his fate, his ultimate defeat at the hands of the law. This strenuous moralizing was just barely enough to temper the dramatic power of the stories themselves—all those pages of brightly colored action drawings. The pages that concentrated on the crook. And in the hands of many of Biro's imitators, the moralizing became muted, and the lessons were lost amid the turgid excitement of headlong lawless action. The apparent newsstand success of Crime Does Not Pay encouraged imitation in the postwar scramble for something that would sell as well as superhero titles had during the War. And imitation bred excess as each copycat tried to out-sensationalize the others. Simon and Kirby were among the first to take Biro's book as inspiration. In the winter of 1947, they revamped Headline Comics, converting it with the March issue from a collection of stories about boy heroes to an anthology of the deeds of gangsters and murderers. In their restraint on matters of violence and sex, Simon and Kirby were the exceptions rather than the rule. Everyone else, it seemed, tried to out-do the Gleason title. In the increasingly frenzied search for new and more spectacular sensations, the moral content of the crime comics was soon eclipsed by blood and bosoms. The undermining flaw in the crime comic book design, the genre's narrative technique, emerged more and more clearly. As the protagonist of the tale, the outlaw stood in the narrative spotlight traditionally occupied by the hero of a story. Hence, by this storytelling maneuver, the crook became the ostensible hero. And by implication, the crook's career became "heroic," and the life of crime was held up, however unintentionally, as worthy of admiration. This unintended by-product of a narrative method fueled the argument against comics being advanced in the postwar years by a psychiatrist named Fredric Wertham and many others. (For details about Wertham and the crusade against comics, consult Hindsight for “Wertham Revisited,” March 2007, an examination of his book, Seduction of the Innocent, and “Why Can’t Bad Comics Have Bad Effects?” March 2006. Best to read them in that order.) Another new genre emerged at the end of the decade, and it attracted even greater criticism. The earliest comic book of horror stories was probably Adventures Into the Unknown, first published by the American Comics Group in the fall of 1948. These were tales of eerie events and ghosts and goblins and other creatures of the supernatural night. Nothing much came of this single title's foray into the terror-fraught world of the paranormal at first. But by the time Bill Gaines and Al Feldstein began telling horror stories in EC Comics in the spring of 1950, the time was ripe for the genre. In horror and crime comic books, the industry had at last found a winning substitute for the superpatriot titles of the war years. EC and its legions of imitators gave Wertham and his followers all they could have hoped for. Virtually every publisher produced a horror title sooner or later in the early fifties. Even Simon and Kirby joined the crowd—with Black Magic, starting in October 1950. The newsstands seemed glutted with crime and horror comic books, and newspapers blared daily about a wave of juvenile delinquency surging across the land. Parents became increasingly alarmed. The cry to ban comics grew louder. To forestall government censorship, comic book publishers banded together in 1954 and created the Comics Code Authority to establish and enforce stringent regulations about what could not be printed in comic books. And that was the beginning of the end. Distributors were reluctant to carry any comic books not bearing the CCA seal. Without distributors to get titles to the newsstands, publishers faced certain extinction. Many stopped publishing comic books altogether. EC Comics, most of which used words in their titles that were forbidden by the Code, simply went out of existence. Companies that continued to publish comics produced pablum: only the most innocuous kinds of stories could pass muster with the CCA censors. As an art form, the medium languished: the strictures of a censored medium are not conducive to creative experimentation. The boom years were clearly over. Television, which became a nation-wide medium in the mid-fifties, was partly responsible for the decline of the comic book industry. But the anti-comic book crusade had also played a large role in the demise of the business. A spate of comic books based upon television shows flooded the newsstands with undistinguished work for a few years, then in the spring of 1960 at DC Comics (then called National Periodical Publications, the publishing oak tree that grew out of Nicholson's acorns), editor Julius Schwartz made a fateful decision. Schwartz had engineered a revival of interest in superhero comics by refurbishing two of DC's oldest characters, the Flash and the Green Lantern (in 1956 and 1959 respectively). Seeking to extend his winning streak, Schwartz decided to launch a new title in which several superheroes would act as a team. From a marketing point of view, the plan seemed relatively risk-free. First, in teaming several superheroes, it repeated a popular device from the forties; what sold well then might just sell well again. Secondly, by putting several superheroes on the cover of the magazine, Schwartz avoided gambling on the popularity of a single character to sell the comic book. The Justice League of America (cover-dated October-November 1960) confirmed Schwartz's instincts; it sold well. Over at Atlas Comics (once Timely Comics, soon to be Marvel Comics), publisher Martin Goodman directed his editor, Stan Lee, to come up with something akin to the Justice League in order to cash in on the apparent resurgent interest in superheroes. And Stan Lee turned to Jack Kirby. Kirby had been working with Lee since late in 1958 when the company had been near death's door. Kirby had come to the office looking for work. "I came in, and they were moving out the furniture," Kirby recalled. "They were taking the desks out. I had a family and a house and I needed work, and Atlas was coming apart! Stan Lee is sitting on a chair crying. He didn't know what to do. I told him to stop crying. I said, Go in to Martin and tell him to stop moving the furniture out, and I'll see that the books make money. And I came up with a raft of new books, and all these books began to make money." These were what Kirby called "the monster books"—Strange Worlds, Tales to Astonish, Tales of Suspense, tales of the supernatural with creatures from outer space. He also contributed to the company's string of westerns, Kid Colt Outlaw, Gunsmoke, Rawhide Kid and Two-Gun Kid. It was a busy time for Kirby. In the winter of 1960, charged with creating a new team of superheroes, Lee says he conjured up "the kind of characters I could personally relate to; they'd be flesh and blood, they'd have their faults and foibles, they'd be fallible and feisty, and—most important of all—inside their colorful, costumed booties, they'd still have feet of clay." Then, he says, he wrote "a detailed first synopsis for Jack to follow" and gave it to Kirby, who went off to draw the inaugural adventures of the Fantastic Four. The result was a team of superheroes like the Justice League but with a crucial difference: they had individual personalities, flawed like everyone's, and they bickered and squabbled amongst themselves. Kirby's version of the act of creation is somewhat different. In fact, he maintained that Lee had very little to do with concocting this distinctive new breed of superhero. The two had developed a unique way of working together, a method that had the dubious benefit of permitting each to claim creator's credit. Lee would give Kirby a plot outline, often little more than an oral precis. Then Kirby, according to Lee, would "draw the entire strip [comic book story], breaking down the outline into exactly the right number of panels, replete with action and drama. Then it remained for me to take Jack's artwork and add the captions and dialogue." Who, then, created the story? Lee could say he did: he invented the plot and added the necessary explanatory verbiage at the end of the process. Kirby could say he did: not only did he give the plot and the characters a graphic reality, he (in Lee's words) provided the action and drama. Neither man is lying or stretching the truth. And both men are entirely correct. (For more in this vein, see “The Making of the Marvel Universe,” here in Hindsight, July 2003.) Their manner of producing comic books was quickly institutionalized. Lee adopted the same procedure when working with other artists who succeeded Kirby on some of the new titles that soon came pouring out of Marvel. The method had perhaps been the invention of necessity: only in this way could Lee and his stable of artists crank out enough product to keep the sales of the new comic books soaring. Assuming that Lee did, in fact, supply his artists with rough plots, he effectively delegated to them the task of fleshing out story ideas, which saved him hours of work over a typewriter. He could then use the time he saved to script dialogue and captions for the pages of narrative artwork that his artists turned in. The result was a high rate of production. And there was another benefit. The so-called "Marvel Method," whether by design or accident, had the virtue of putting the control of storytelling in the hands of the artists, who tended to tell stories pictorially rather than verbally. For comic book artists like Gil Kane, this approach was the only approach that made any sense. "I've worked from scripts," Kane said, "but the most freeing experience I've had, other than working from my own scripts, is to write according to the technique that Stan Lee and Jack Kirby worked out, which was talking over a plot line with the writer and then laying out the entire story dramatically, and afterwards the writer comes in and puts in the copy. I find that for me that is the most satisfying thing. I'm rarely in agreement with a writer. In fact, it's ridiculous that the first one to approach a white, unmarked page is the writer and not the artist, or that the writer makes all determinations on how the page is cut up and everything else. "[The Marvel Method] is the best thing in terms of writing and drawing and effecting a balance," Kane went on. "Just like a writer and a director get together when they are going to do a [movie] and discuss it, the point of view and the approaches, and then begin a basic storyline. It's best now, to do it that way, to turn out an outline, give that outline to the artist after it's already been discussed. And the artist then dramatizes it. That's what the artist is: he's a dramatizer. If the writer is in effect a structurer, the artist is a dramatizer, a storyteller. And after he's then interpreted this structure that they have both agreed on, then the writer comes on and he's able now to second guess. That means he's able to take advantage of dramatic situations that are fully developed [by the artist/dramatizer]. And I think without question that the [resulting] writing is infinitely more spontaneous, more varied, more effective than it ever could be if the writer just sits down and just types out ‘panel one, scene one’ and dictates the thing right from the start. Then the artist is merely an instrument—and not an instrument that has any choices or alternatives. [Under that circumstance,] he has this straitjacket that he has to work with, this script, which doesn't anticipate transitions, quick cuts. It doesn't anticipate a visual interpretation because if it did, then they would do storyboards, they wouldn't do script." Working in the Marvel Method, artists did more than give the characters facial expressions and their poses body language: they did narrative breakdowns and layout, thereby determining the pace of the story and the visual emphases—and with that, the essential action and drama of the stories. In theory. In practice, it didn't always work that way. As other writers joined Lee in plotting and scripting stories (and then succeeded him), they were less content with his make-shift method: the artists sometimes did not produce the visual effects the writers imagined they would. And what they did produce "ruined" the writers' concepts for stories. To correct these "errors," as I have observed elsewhere (in my book, The Art of the Comic Book, here), writers heaped expository prose onto the pages, weighing the action down with verbiage. Still, the Marvel Method, for a time (Kirby's time at any rate), restored some of the visual-verbal balance that the enthronement of writers throughout the industry had threatened for years. Although Kirby once denied outright that Lee did any writing at all on the features they created jointly—saying, instead, that he, Kirby, devised the stories himself and wrote the dialogue and captions on the backs of the illustration boards—he may have been exaggerating. At the time, he was involved in an arduous effort to retrieve his original artwork from Marvel, a complicated, painful and acrimonious endeavor. And when he was pressed about Lee's role in creating what eventually became known as the Marvel Universe of superheroes, Kirby claimed the credit. Lee, according to Kirby, did nothing but supervise production and schedules and the like. Since each of the principals directly contradicts the other, we will probably never be able to resolve the matter by relying exclusively on their testimony. The truth, as is the case in most disputes of this kind, doubtless resides a little in each camp. My guess is that Kirby did more plotting and character creation than Lee admits; Kirby probably did some writing, too—scripting speeches and captions—particularly when the new line of comics began to sell and the team had to produce more and more books faster and faster to meet the demand. But Lee's colorful command of language is his own, not at all like Kirby's way with words. The distinctive Marvel lingo was undoubtedly furnished by Lee. His role, however, was essentially that of verbal embellisher (lyricist, as Gil Kane put it); in my view, Kirby was the creative force of the team. On his own behalf, Kirby once pointed out that Lee didn't create very much of anything after he, Kirby, left Marvel in late 1970. And that's true. All Lee's highly touted creative period occurred while Kirby was in the Marvel bullpen. Kirby, on the other hand, went on to create single-handedly the highly imaginative Fourth World series of titles for DC Comics in 1971, a heroic science fiction mythology about gods fighting gods which he then plotted, drew, and scripted for two years. Kirby's lifetime record teems with characters and concepts he created. And when it comes to the Fantastic Four, the astonishing first of the new generation of superheroes—the characters that would change the nature of superhero comics—they are more likely Kirby's creations than Lee's. Everything in Kirby's career suggests that the invention of this aggregation of idiosyncratic albeit heroic personalities was but the latest step on a path he had followed most of his professional life. With the Fantastic Four, Kirby was revisiting familiar ground. He and Simon could almost be said to have specialized in fabricating teams of heroes for comic books. Their first such venture had been Young Allies for Timely in the summer of 1941; the book featured a gang of kids who tagged along with Captain America's sidekick, Bucky, providing a juvenile chorus for his deeds. Then came the Newsboy Legion, which debuted in DC's Star Spangled Comics No. 7 (cover-dated April 1942). Spotlighting a gang of so-called "bad kids" from the mean streets of New York who make good when the adult world is apparently stacked against them, the Newsboy Legion was reminiscent of the Boy's Brotherhood Republic of Kirby's youth. But the series was part of an even more visible boy gang phenomenon. Beginning in 1937, Hollywood had produced a series of movies based upon Sidney Kingsley's Broadway play, "Dead End," in which Leo Gorcey, Huntz Hall, and others played canny slum kids. The Dead End Kids movies emphasized a youthful display of camaraderie, street-smart wise-cracking youths, and, in the best American tradition, the eventual triumph of the underdog. (The movie series went by several names over the years, finishing a twelve-year run as the Bowery Boys in 1958.) When Simon and Kirby asked themselves what would happen if the Newsboy Legion went to War, the Boy Commandos resulted. Appearing first in Detective Comics No. 64 in June 1942, the Boy Commandos eventually graduated to their own title. The significant thing about the group, however, was that each of the boys came from a different Allied country: Alfy was from England; Andre, from France; Jan, Holland; and Brooklyn, from the United States. And each boy's personality reflected something of the national character associated with his place of origin. With his derby hat and accent, Brooklyn, not surprisingly (given Kirby's background), was the most picturesque of the troupe. The boys would be reincarnated again in Boys' Ranch. And there, Wabash, a Southern kid with the physiognomy of Brooklyn, is the most distinctive of the youths. In late 1956, Kirby was again working for DC Comics. He was now a solo act: Simon still worked with him on Young Romance, but comics, for all intents and purposes, were no longer his principal livelihood. At DC, Kirby worked on "monster and superstition" titles, House of Mystery and Tales of the Unexpected, and then created a continuing series. This was Challengers of the Unknown, another team adventure title. Although scripted by Dave Wood, the series was conceived by Simon and developed by Kirby: it bears the usual tell-tale signs. Beginning in Showcase No. 6 (cover-dated February 1957), the team consisted of four adults: Professor Haley, a scientist and skin-diver; Ace Morgan, a fearless jet pilot; Rocky Davis, an Olympic wrestling champion; and Red Ryan, a circus daredevil, the youngest of the quartet and something of a hothead. They had all survived a plane crash, and, feeling that they were living on borrowed time, they agreed to take on any assignment, particularly those involving unknown dangers. As before, Kirby enlivened the tales he told by making his protagonists as interesting as possible, as human. And that meant they weren't perfect. "Perfect heroes are boring to the reader," Kirby said; "they've got to have human frailties to keep the story interesting." In the Fantastic Four, then, Kirby can be seen continuing an endeavor that he had been improving upon since before the War. He gave his heroes distinctly different personalities, and he gave his stories an extra dimension by having those personalities rub up against each other, sometimes creating friction of a sort superhero comics wholly lacked. Published in 1961 (cover-dated November), The Fantastic Four comic book revitalized Goodman's business, becoming the foundation for the Marvel Comics Group. When the title sold, Kirby created other new characters (including the X-Men, whose popularity was destined to outstrip all the others and to set a new fashion for superhero teams), all based upon the now-proven premise that superheroes were people too, and they should have distinct personalties as realistic and quirky as those of their readers. After the Fantastic Four came the inarticulate Hulk, brute strength incarnate; then the Norse thunder god Thor, an early manifestation of Kirby's fascination with gods. (And in the meantime, Steve Ditko was collaborating with Lee on Spider-Man, a teen-age superhero riddled with adolescent angst, and Doctor Strange, a magician who strays into the supernatural.) While Kirby was plotting and drawing (sometimes working from Lee's ideas; sometimes, we suppose, not), Lee secured a place for himself in the history of comics by scripting Kirby's creations, lacing the editorial pages as well as the captions with outrageous alliterations and unabashed hyperbole. Lee's was no small accomplishment: his extravagant verbal gyrations gave the books a tongue-in-cheek tone, and this attracted a new readership. Kirby created the visual excitement—the characters and the adventures; Lee created the marching minions of Marvel fandom. Their combined effort bordered on mocking the very genre Kirby had helped to create before World War II. As it turned out, it was an approach that appealed to an older audience than the traditional comic book reader—namely, college students. This broader, more mature as well as more articulate readership eventually formed itself into a network of fans that became a viable market that fostered economic growth that, in turn, nurtured creativity in the medium. It began with readers of Marvel and DC Comics writing letters to the publishers about their favorite characters—and about errors in science or fact or continuity that they spotted in the latest issues of their favorites. When the letter writers started writing to one another, the network began to form. Some fans published newsletters; and some of the newsletters metamorphosed into saddle-stitched magazines. In the spring of 1961, Don and Maggie Thompson produced the mimeographed Comic Art, arguably the first "fanzine" to be devoted to all areas of cartooning—strips, books, animated cartoons, political cartoons. About the same time, Jerry Bails and Roy Thomas published Alter Ego, which concentrated on the superhero in comic books. Meanwhile, the natural impulse to meet and talk with a pen pal resulted eventually in the first comic book conventions. In April 1964, Robert Brosch convened a gathering of fans of comics, science fiction, and movies in a downtown Detroit hotel. (This effort was continued the next year by Jerry Bails and Shel Dorf, who christened the event the "Detroit Triple Fan Fair." Later, in 1970, Dorf took what he had learned about media fan conventions and founded the San Diego Comic Convention, destined to become the nation's largest such event.) In the summer of 1964, another convention for comics fans was conducted in New York by a fellow named Bernie Bubnis (who also coined the term "comicon"). A network such as now existed commanded some modicum of respect among publishers: sometimes it seemed there were almost enough such fans to constitute a buying public whose purchases alone could assure the success of various comic book titles. Then in the mid-1970s, a Brooklyn school teacher set out to prove the validity of that supposition. Phil Seuling, one of the pioneers of comic book conventions, now proposed a dangerous marketing departure to Marvel and DC. What he proposed became known as the direct sale market, and it revolutionized comic book publishing. Until the direct sale shops came into existence, comic book publishers sold their wares through national distributors of magazines and periodicals. Stores bought their publications from the distributors at a discount—say, 60% of the cover price. But if a store didn't sell all of the copies of a particular title it had purchased, it could return the unsold items for credit against their next order. Because the sale of periodicals is time-bound—that is, this month's issue is theoretically out-dated by next month's issue—there were always a number of unsold copies at the end of the month. The market was wholly unpredictable: in order to realize a sale of 130,000 copies of a comic book, a publisher might print 250,000 copies. Half of the print run would never be sold, and the unsold copies were, by agreement, destroyed as an act of good faith to assure the publisher that he had received all the revenue that a given issue could produce. (No copies, in other words, were being sold under-the-counter after the retailer had been credited with the returns.) But with the growth of a fan market, a demand for back issues had developed. Seuling's idea depended upon the vitality of that demand. If the publisher would sell directly to a store at a greater discount off cover price than through a distributor, then the stores would forfeit returns for credit. If they didn't sell all of a month's title, they'd store them for sale eventually to back-issue buyers. The deep discount and the interest in back issues made the plan economically feasible for retailers. The advantage to a publisher was that it would no longer be necessary to print 250,000 copies of a title to sell 130,000 of them. Moreover, once the network of direct sale shops was in place, publishers solicited the shops in advance of publication of all titles, and they set print runs based upon quantities ordered, yielding additional savings that promptly translated into profit. The direct sale shops made comic book publishing a money-making venture again. Since publishers no longer had to risk investment in gigantic print runs half of which routinely never sold, they had more financial resources to devote to developing titles that would appeal to the fan market, which, by the mid-1970s, was numerous enough to support the industry almost without general newsstand sales. Before long, many titles were available only through the direct sale network. And many of those were extremely individualistic artistic statements. The prospect of realizing a reasonable financial return on a relatively small investment stimulated the formation of numerous small publishing houses, often called "alternative publishers." The more publishers, the more outlets for creative expression. With a ready market for relatively personal works and a growing number of publishers willing to publish such products, the comic book industry became receptive to artistic enterprise as never before. It is perhaps not too wild a speculation to say that all of this can be traced to Jack Kirby's inspiration. It was he who laid the groundwork for superheroes with human rather than archetypal personalities. And superheroes with human failings attracted—and held—an older audience, and that continuing interest lead to direct sale comics shops as well as adult readership. That's what Jack Kirby did. When we call him the King, we do it because he virtually created the empire. Twice. Here’s a Gallery of Kirby artifacts.

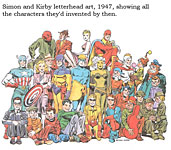

The preceding essay appeared first as a chapter in a book of mine, The Art of the Comics (more about which you can find here), and was subsequently revised for the issue of the Comics Journal that served as an extended obituary for Kirby (No. 167, April 1994); it was revised again for The Comics Journal Library, Volume 1: Jack Kirby, and again for this appearance, adding a few new facts and tinkering with some verbiage. |

||||||||