ON FRIDAY NIGHT, March 1, 1946, twenty-six cartoonists assembled at the Barberry Room on East 52nd Street in Manhattan. They met at 7 p.m. for drinks and dinner, and after dinner, they waved their inky-fingered hands and conjured into being the National Cartoonists Society. Then when the voting was over, they started a heated argument about how to define a cartoonist and retired to pour cooling emollients on the conflagration.

The Society may have been formally founded on that Friday night, but it had been gestating for years. Accounts about the birth of the Cartoonists Society vary—as is their wont among the regularly imbibing band of bon vivants who put on chalktalk hospital shows during World War II with the American Theatre Wing. Even those who were present on the legendary night in question couldn’t agree later as to exactly where they had been. Rube Goldberg said it was Quantico, Virginia. Gus Edson alleged it was Charleston, South Carolina. But the Cartoonists Society, everyone agreed, had been born far from the comforts of home on one of those long-range junkets the group made to military bases along the southeastern seaboard.

It had all started in 1943. In the early months of that year, the early results of America’s entrance into the European conflict began to trickle in from North America, filling beds in five huge hospitals in the New York area. And almost immediately, the United Services organization and the Red Cross started drumming up entertainments for the recovering GIs. Among those who heeded the summons was C.D. Russell (who drew Pete the Tramp), who mustered a small entourage of fellow cartoonists to do chalktalks for the wounded under the auspices of the U.S.O. In addition to Russell, the group usually included Bob Dunn and Paul Frehm from the King Features bullpen, and Otto Soglow (Little King) and Gus Edson (The Gumps).

“We played two spots,” Edson recalled. “Fort Hamilton and Governor’s Island. And then we quit the U.S.O.”. They were not driven out: they were lured away. By a chorus girl.

Once a Rockette at Radio City Music Hall, Toni Mendez was now a choreographer as well as a dancer, and she was an active member of the Hospital Committee of the American Theatre Wing, an organization of women in the entertainment and communications fields, which was then sponsoring several enterprises for the morale of soldiers. The Hospital Committee devoted itself to the wounded, meeting once a week to plan shows to give at armed services hospitals.

At just about the time that C.D. Russell and his troupe started feeling mutinous under U.S.O.’s wing, Toni Mendez had offered to help put together a show about New York that would use the talents of New Yorkers who were not necessarily professional entertainers. In a conversation with the director of public information at the telephone company who was a friend of Edson’s, she learned about the cartoonists and their chalktalks. She met with Edson, and they arranged the first of the A.T.W. sponsored cartoonists’ shows.

They expanded Russell’s original group to include Martin Branner (Winnie Winkle), Ray Van Buren (Abbie ’n’ Slats), Ad Carter (Just Kids), Ernie Bushmiller (Nancy), Bill Holman (Smokey Stover), Al Posen (Sweeney and Son), and Milton Caniff (Terry and the Pirates). Russell recruited an emcee for the act—Bugs Baer, humor columnist and after-dinner raconteur. Russell Patterson soon joined the more-or-less permanent ensemble, and when Baer’s other obligations side-lined him, Rube Goldberg, then doing editorial cartoons for the New York Sun, was drawn into the act (again by C.D. Russell).

The inaugural performance at Halloran Hospital on Staten Island was a unqualified success—and not entirely as a result of easel artistry. Several of the cartoonists were born comedians: they gloried in the spotlight of performing before an audience, and they augmented their drawings with waggish verbal wit and farcical flourishes that betrayed a more than nodding familiarity with burlesque houses and an almost defunct vaudeville stage. And Toni Mendez was quick to arrange an encore.

“I soon learned,” she told me, “that one way to get them to assemble on time was to arrange to meet at a bar instead of at the Wing building.”

A typical evening’s expedition began in Child’s restaurant at 57th and Fifth Avenue, where the cartoonists (some with their wives) collected to await the arrival of the bus that would transport them to their destination. As they waited—and while their number assembled—they oiled their vocal chords for the forthcoming performance. At the appointed hour, Toni Mendez (in her trademark giant chapeau) appeared at the door and beckoned.

They all clambered into the bus—a no-frills military conveyance with back-breaking springs and memorable seats of the unpadded variety—and when everyone was safely ensconced therein, it lurched into gear and headed for South Ferry en route to the distant clime of Staten Island.

THE AMERICAN THEATRE WING trips to military installations resulted in a certain quantity of lore being generated. And having created some history of their very own, the members of this dirty-fingernail fraternity delighted in regaling themselves with it for years afterwards in the meetings and publications of the Society.

It wasn’t long before some of them began to talk about finding a way of perpetuating their fellowing, of assuring its continuance after the end of the War presumably wiped out the need for the hospital shows, thereby eliminating the excuse for their periodic convenings. It may have been C.D. Russell who first put the notion into words. Tour leader Toni Mendez remembers the trip on a military transport plane during which Russell, well fortified for the flight, patroled the aisle of the plane, advocating a club for cartoonists.

“He said, Everybody has a club or an association or some kind—lumber jacks, undertakers, rug weavers, even garbage collectors—so I don’t see why we can’t have one, too. All during the flight, Rube kept saying, No—leave us alone; we’re doing fine. And C.D. turned to me,” Toni continued, “and he said, And no girls. Only boys. And he went up and down the aisle of the plane, repeating that this club would be just for boys.”

The idea had been voiced. But everyone knew no club for cartoonists would succeed without Rube’s participation. “They kept after him,” Mendez said, “until they made him agree.”

It was Russell Patterson who lobbied most convincingly for the cause. He shared a room with Rube on that storied night the Cartoonists Society was born (in either Charleston or Quantico.) Neither man could sleep, so they talked. And Patterson availed himself of the opportunity to urge Goldberg to endorse the idea of a cartoonists’ club. Rube continued to scoff at the idea at first, declaring that cartoonists were such anarchists they’d never come to meetings. They’d tried it once before in the thirties, he said, and it hadn’t worked. But Patterson was not to be put off. He persisted. Rube’s resistence began to crumble. According to Patterson (as reported by Stephen Becker), Rube finally yielded as the two climbed into bed: “All right,” he growled, “but no more than twenty-five members.” Patterson continued the story (in italics):

We’d been in bed about ten minutes when Rube raised himself to one elbow, snorted, and said, “All right. But no more than fifty members.” After that, he went to sleep. I waited for him to bring it up in the morning, but he didn’t say a word about it. Then we got on a plane to go back to New York, and when we were in the air a couple of the spark plugs turned out to be faulty. Rube was a little worried. He was mangling a cigar and looking out at the engine. Every once in a while he’d look down, as though he were estimating the fall.

“Why don’t you be the focal point of a society, Rube?” I asked him. “We can send out invitations in your name.”

“Yeah, sure,” he said. “Anything.” He peered out at the engine. “There’s no way to get out of this damn machine, I suppose.”

“Sometime when the War ends,” I said, “we ought to call a dinner meeting.”

“Absolutely,” Rube said. “How high up do you figure we are?”

“We’d have to get it well organized at the first meeting. Officers, bylaws, and maybe a regular meeting place. You’re the logical man to be president for the first year.”

“Whatever you say,” he said. “You think this pilot’s ever flown before?”

Thus was a cartoonists’ club born. It needed only a name and some semblence of formal organization. For those, it awaited the War’s end. By February 1946, a group of six of them succeeded in bullying Rube into sending out letters to call a dinner meeting for the purpose of organizing the club. The letter went out on February 20 (in italics):

Fifteen of us cartoonists were thrown together pretty often during the last few years when, as a unit, we entertained at army camps, navy bases and various hospitals.

Strangely enough, we grew to like one another. We looked forward to these meetings—and still do. There was no spirit of competition. There was plenty of glory for all. We had a swell time. Now we know that cartoonists have something in common besides a bottle of ink and a sheet of drawing board.

So we got the idea it might be a very natural thing to have a cartoonists’ club or society. Acrobats have clubs. Ski jumpers have clubs. Upholsterers have clubs. Why can’t we have a club? We can.

Any cartoonist who makes his living at it is eligible to join. But he doesn’t have to. Nobody is going to coax him. The idea is to bring a bunch of nice guys together for a little real, informal association. We can have an occasional dinner. Perhaps we might have a club room where we can make out-of-town cartoonists feel at home. We think New York is the logical headquarters for the club.

Your name has been selected to join a group to sit down at dinner to make some plans—select a name, determine the dues, elect officers, and other such nonsense.

Rube signed the letter as “temporary chairman.” At the top of the epistle appeared the names of the “temporary committee” (recognized in subsequent histories as the founders of the Society): Rube Goldberg, Ernie Bushmiler, C.D. Russell, Gus Edson, Russell Patterson, Otto Soglow, and, at the top of the list, the best-known of their number in those days, Milton Caniff, who had been an active promoter of the organization from the very first. (Goldberg’s pivotal role is reiterated in a little more detail in Harv’s Hindsight for January 2001.)

Caniff had been involved with clubs and similar groups all his life. His membership in the New York clubs in particular had given him a clear notion of what such organizations could do. Although with their emphasis on camaraderie, these clubs were chiefly social (and that alone had sufficient value to the members to justify the clubs’ existence), the very fact of organization tended to give stature to the profession thus embodied. The clubs therefore represented their professions in some sense, and they were positioned to speak for their members’ interests without being unions or anything like unions. Caniff could see that a similar club for cartoonists could perform some valuable services for its members and for the profession. It didn’t have to be a union to do so. And while its main purpose might be fellowship, the club wouldn’t have to be exclusively a social organization. Apart from a predeliction to purposefulness, Caniff would bring to the infant group an even more important quality: he had a good feel for what makes an organization cohere, for what it gives it its being. And in the early years of the National Cartoonists Society—indeed, throughout his life-long association with it—he would work long and hard to implement both his vision and his instinct. He soon became a guiding force in the group, and he remained so for life.

At least twenty-five of those to whom Goldberg sent his letter came to the Barberry Room on March 1, 1946. And the evening was a success. The organization was officially founded: it acquired a name and officers. If it was still a little unclear about its purpose, it was nonetheless lively, judging from the report in the Cartoonists Society Bulletin some months later (in italics):

We are not a union but purely a social group which we proved the opening night by almost coming to blows twice. First in the selection of a name and again when we tried to decide just what the hell a cartoonist was. After much bickering, hemming, hawing, and speech making, we chose “The Cartoonists Society” over “The Cartoonists Club.” Nuts to euphony was the attitude. Nuts to euphony too, Gus Edson shouted at the temporary chairman merely to keep the harmony rolling.

Later, the Society would add “National” to its name as a way of telling cartoonists all across the country that they, too, were welcome in its ranks. The definition of cartoonist was an important preoccupation because it would establish eligibility for membership. The question was not resolved until it had been thoroughly discussed for several meetings. Finally, the NCS constitution defined cartoonists as “professional artists who portray by text and drawing a comic or adventure story or incident, or a commentary on politics, current events, or sports.”

The elections that evening were a much more perfunctory matter. Rube Goldberg was elected president by acclamation; Russell Patterson, vice president; C.D. Russell, secretary; and, as treasurer, Caniff. A second vice president was subsequently added (“to follow the first vice president around”) in the person of Otto Soglow. In recognition that the expenses of the Society would be greater per capita for cartoonists living within easy driving distance of New York, a dues schedule with a differential for out-of-towners was set that night: cartoonists living within fifty miles of the city would pay $25 a year; the rest, $15. The twenty-six cartoonists who attended the first meeting immediately paid their dues to Caniff and declared themselves members.

ALMOST EVERY ENDEAVOR at which a cartoonist could ply a pen was represented among the charter members–comic strips, panel cartoons (both magazine and newspaper), editorial cartoons, comic books, advertising and illustration. Animation was the only branch of the craft absent from the roster of the first members.

No attendance was taken that first night; no charter signed. So there is no roster of the first members. But if we don’t know exactly who the 26 charter members were, we know they must be among the 32 names Caniff listed as having paid dues by March 13: strip cartoonists Wally Bishop (Muggs and Skeeter), Martin Branner (Winnie Winkle), Ernie Bushmiller (Nancy), Caniff, Gus Edson (The Gumps), Ham Fisher (Joe Palooka), Harry Haenigsen (Penny), Fred Harmon (Red Ryder), Jay Irving (Willie Doodle), Al Posen (Sweeney and Son), C.D. Russell (Pete the Tramp), Otto Soglow (Little King), Jack Sparling (Claire Voyant), Ray Van Buren (Abbie ‘n’ Slats), Dow Walling (Skeets), and Frank Willard (Moon Mullins); syndicated panel cartoonists Dave Breger (Mister Breger), George Clark (The Neighbors), Bob Dunn (Just the Type), Jimmy Hatlo (They’ll Do It Every Time), Bill Holman (Smokey Stover), and Stan MacGovern (Silly Milly); freelance magazine cartoonists Abner Dean and Mischa Richter, editorial cartoonists Rube Goldberg (New York Sun), Burris Jenkins (Journal American), C.D. Batchelor (Daily News), and Richard Q. Yardley (Baltimore Sun); sports cartoonist Lou Hanlon; advertising and illustration, Russell Patterson; and comic book cartoonists Joe Shuster (the artist half of Superman’s creative team, who with partner Jerome Siegel, was now inventing a new costumed hero for comic books, Funnyman) and Joe Musial. Two of this number—Bishop and Yardley—were out-of-towners and may not have been present at the March 1 meeting. But which of the remaining 30 attended the founding festivities is a lost fact.

The Cartoonists Society was now a reality. Cartoonists at last had a home, an organizational roof over their heads—thanks to the American Theatre Wing,

By mid-May, fourteen more cartoonists had signed up—including Harold Gray of Little Orphan Annie and the Society’s first animator, Paul Terry. In June, Caniff’s letterer Frank Engli joined and Popeye’s Bela Zaboly. And later in the summer, Li’l Abner’s Al Capp joined and Bruce Gentry’s Ray Bailey. When the National Cartoonists Society met to celebrate its first anniversary in March 1947, its members numbered 112, and in its ranks were most of the famous names in cartooning—Bud Fisher (Mutt and Jeff), Don Flowers (Glamor Girls), Bob Kane (Batman), Fred Lasswell (Barney Google and Snuffy Smith), George Lichty (Grin and Bear It), Zack Mosley (Smilin’ Jack), Alex Raymond (now, after his WWII stint in the Marines, doing Rip Kirby), Cliff Sterrett (Polly and Her Pals), Chic Young (Blondie), and editorial cartoonists Reg Manning and Fred O. Seibel and sport cartoonist Willard Mullin. And others. And more would follow in their ink-stained footsteps. In a year, the National Cartoonists Society had become a healthy organization, and it was slowly evolving a purpose.

They met on the fourth Wednesday of each month, and the meetings were always dinners and mostly social. They met at the Barberry Room, Toots Shor’s, “21,” Moriarity’s, “and a few other saloons” (as Goldberg put it) before finally settling in on a more-or-less regular basis at the Society of Illustrators Clubhouse on East 63rd Street, where they found the bar convivial and the atmosphere homey (particularly for forty of their number for whom the Illustrators Clubhouse was an alternative organizational home: they were members of both groups). In the custom of such clubs, each monthly dinner featured a guest speaker, a notable in a career or profession of interest to the cartoonists.

Although the fraternization of the evening was the principal attraction for most of the members, some of them began to urge taking some sort of action on various matters of serious import for cartoonists. They talked about creators’ rights and what the proper relationship should be between a syndicate and the author of one of its features. They talked about engaging legal counsel to draw up a model contract for syndicated features. And they talked about an emerging threat of censorship from external sources..

IN THE SPRING OF 1947, Caniff achieved another distinction in a career of distinctions. His peers had been watching his performance with fascination and appreciation. He had left Terry and the Pirates at the end of 1946 and had started a new adventure strip, which debuted in 234 newspapers (of which, the editors of 162 had signed before any promotional material had been produced). For Caniff’s colleagues, the ascendant Steve Canyon represented much more than another vivid demonstration of Caniff’s technical facility and storytelling virtuosity. It was all of that, but something else about the strip’s triumphant progress gave them all a special pleasure. For Caniff had pulled it off. He had done it. He had broken free of the bonds of syndicated servitude and had successfuly launched a new strip without the usual indenture. He had proven anew what Gene Ahern and Roy Crane had proven before him—that a cartoonist could leave a popular feature and start another one equally popular, this time owning the creation himself. That such a thing was possible needed to be reaffirmed: so much else that cartoonists encountered in their professional lives seemed to deny it. And what made it all so richly gratifying with Steve Canyon was that Caniff had done it so well: his new feature seemed every bit as great as its predecessor. Caniff had more than survived his transition from the old to the new: he had surpassed himself. And on the evening of May 11 at the monthly dinner meeting of the National Cartoonists Society at the Society of Illustrators Clubhouse, Caniff became the first cartoonist to be formally honored by the group as “the outstanding cartoonist of the year.”

The trophy was a handsome silver cigarette box, its lid engraved with pictures of the characters in Barney Google and Snuffy Smith, the strip that Billy DeBeck had brought to immortality before he died after a long illness in 1942. DeBeck’s widow, Mary, made the presentation to Caniff that evening. It had been her idea that the Society institute an annual award recognizing the cartoonist who was the best of the year. She would furnish the prize, she said, if it could be awarded in the name of her late husband. Known officially as the Billy DeBeck Memorial Award, it was also briefly called “the Barney”—in imitation of the film industry’s practice of referring to its most prestigious prize by an informal first name.

As long as DeBeck’s widow lived, the selection of the “cartoonist of the year” was made by a committee of one. “Mrs. DeBeck arbitrarily decided who would win,” Caniff told me years later. “I’ve never talked with anybody who was ever consulted about it. I’m not absolutely certain, of course; she may have consulted people, but no one I talked with knew of it if she did. She never consulted me—naturally, she didn’t consult me on the first one. And never after that. She just made the choice and presented the Award, and that was that.”

(In 1972, Caniff was again named “cartoonist of the year” for 1971—arriving at the designation, this time, by a selection process that was put in place after Mary DeBeck died.)

In the record books, the strip coupled to Caniff’s name for winning the first Barney is Steve Canyon, but the award officially cites him as cartoonist of the year for 1946, Terry’s last year. A certain poetry lurks in this anomoly: that a single portmanteau citation recognizes both the works for which he is most famous seems history’s quirky way of validating the fitness of the award. But practicality not poetry determined the oddity. For hard-headed promotional purposes, every cartoonist wants to be identified with the feature by which he earns his bread. And since the recipient of the DeBeck Award was urged, as a matter of stated policy, “to enjoy any amount of personal publicity which may accrue to him as a result of national interest in the bestowal of the honor,” it was virtually Society doctrine that Steve Canyon be mentioned in the same breath as Milton Caniff. And preferable as often as possible.

In 1953—after the death of DeBeck’s widow—the Barney was retired and replaced by the Reuben. It was named in honor of NCS’s first president, and the trophy is pure Goldberg. In fact, it was cast from a sculpture that Rube himself made. He didn’t create the sculpture to serve as the NCS award: when he made it, he thought he was making a lamp. Happily, Bill Crawford saw this objet d’art in Rube’s home at just about the time the Society was looking for a trophy for the Reuben, and he recognized at once that Goldberg’s lamp was destined for greater things. He substituted a bottle of ink for the light bulb and made a cast for the trophy. The first to receive the Reuben in all its glory, trophy and fanfare, was the sports cartoonist Willard Mullin, who was named cartoonist of the year in 1954. Rube received the trophy named for him in 1967, three years before he died. (The eight cartoonists who had won the Billy DeBeck Award for the years 1946-1953 were subsequently presented with Reuben statuettes and are termed Reuben winners in the annals of the Society.)

A QUESTION OF LEADERSHIP was settled by the Cartoonists Society in 1948. On the fourth Wednesday in March, numbered 24 that year, in the theater on the first floor of the Society of Illustrators Clubhouse, Rube Goldberg was presiding over the ticklish business of nominating officers for the coming election.

Goldberg had been re-elected by acclamation the year before. And he had enjoyed the occasion hugely. Never one to stand on ceremony, Goldberg relished the spontaneity and informality of an absolutely uncontested re-election by voice vote: it heightened the sense of all-embracing fellowship he felt in the conviviality of the Clubhouse bar. Although he delighted in such shenanigans, he knew the Society could not last long if all its elections were to be conducted as cheering contests: however convivial they might be, shouting matches encouraged a herd instinct and prevented new people from holding office. Congenitally opposed to most of the formal apparatus that accompanied the organizational impulse (which, as a cartoonist, he saw as a vastly amusing eccentricity of the human species), Goldberg nevertheless had been persuaded by less satiric heads that the Society must follow a prescribed routine in electing its officers.

It hadn’t taken much persuading. He had become passionately devoted to the Society—as a group of genial colleagues and as an organization. He was proud of its growth, and he wished for its continued well being. And for that, new leadership would be beneficial. Moreover, he felt he had served his turn; he was ready to step down and make room for someone else. And he was afraid one of those spontaneous demonstrations of allegiance by shouted nomination from the floor would stampede those present into another coronation by unanimous voice vote. He therefore informed the group that officers would not be elected by acclamation. They would follow the by-laws, he said, and name a nominating committee which would select a slate of candidates to be voted on by secret ballot through the mails.

He met opposition immediately. Jay Irving didn’t see why nominations couldn’t be made from the floor that very evening. Frank Robbins agreed, adding that the voting could still be done by secret ballot. Lively discussion ensued. Finally, Irving moved that nominations be made from the floor but that the election itself be conducted through the mail. The motion passed.

Goldberg then announed that he would entertain nominations for President. Predictably, he was promptly nominated. Al Posen put Goldberg’s name forward, and Raeburn Van Buren seconded. Then John Pierotti nominated Caniff and was seconded by Jay Irving. At that, Goldberg declined his nomination in favor of Caniff. And then Greg d’Alessio moved to close nominations. Seconded by Joe Musial, the motion carried, and Caniff, now unopposed, was effectively the new President of the Society.

By the end of the evening, Caniff’s de facto election was formally declared. After collecting nominations for all the other offices, Goldberg retreated from his earlier resolve and suggested that Caniff be elected by acclamation. Dudley Fisher, in town from Columbus for the occasion, made the motion, and John Pierotti seconded, and the motion carried.

The rest of the slate nominated that evening was sent out to the membership by mail ballot, and the results of the election were announced at the April 21 meeting: Russell Patterson was elected First Vice President; Bob Dunn, Second Vice President; John Pierotti, Treasurer; and C.D. Russell was returned (again) to Secretary. Goldberg called Caniff to the stage to turn the Presidency over to him, but Milton insisted that Rube carry on through the rest of the evening. Saying he’d take over the duties of the office the next morning, Caniff promised that he would not make the mistake of allowing Goldberg to retire. He said he’d keep Rube active. And Goldberg was subsequently named Honorary President, a post that kept him on the Society’s Board of Governors for the remainder of his life.

That same evening, Al Capp received the Billy DeBeck Award as cartoonist of the year for 1947.

The next morning, Caniff turned to the first of the duties he had set himself as the new President of NCS. He began a list of news items for a newsletter.

SEVERAL NCS INSTITUTIONS were established during the first half of 1948. At the February meeting, C.D. Russell was relieved of the most onerous of his tasks--taking minutes of the meetings. Henceforth, the minutes would be recorded by a real secretary, Marge Duffy. Marge worked as a secretary in the public relations department of Russell’s syndicate, King Features, and as the Society began to generate more and more correspondence, Russell had enlisted her help on an informal basis. Now it was official. Marge Duffy was eventually designated Scribe of the Society, and her name (Marge Devine after her marriage) appeared on all the Society’s publications: hers was the Society’s permanent mailing address for over thirty years. “She practically ran the damn thing,” Caniff recalled. “A real autocrat,” he said with an appreciative chuckle. “And everyone was delighted to have her be an autocrat because that’s what we needed.”

That summer, NCS held its second annual summer outing at the Shawnee Inn, a posh retreat for the big city carriage trade since 1912 and recently purchased by “the man who taught America to sing,” Fred Waring. Mel Casson had featured the popular Waring radio show in a sequence of his Jeff Crockett, and Waring had subsequently invited Casson to appear on the program. There Casson found out that Waring had a passion for cartoons and comics that was second only to his devotion to the vocal orchestrations of his Pennsylvanians, and when Waring found out about the Cartoonists Society, he invited the entire ensemble to be his guests at his resort in the Poconos. A summer weekend for the cartoonists at the picturesque country club on an island in the Delaware River became an annual event, and then a tradition. The cartoonists expressed their appreciation in their usual fashion, and the corridor to the taproom beneath the Inn’s lobby was soon lined with original cartoons dedicated to Waring. In the taproom itself, the tabletops were decorated with cartoon characters drawn especially for the purpose (artwork protected by a lamination process concocted by the inventor of the Waring Blendor).

Another noteworthy event of the summer was the June 17 dinner meeting at which British political cartoonist David Low was honored. The room was decorated with flags and cartoons from other nations, and the guest list included Whitlaw Reid, publisher of the New York Herald Tribune, syndicate foreign sales representatives, Mrs. Low, and pugilist Gene Tunney. Low was nearly overwhelmed.

“I can’t start to thank you for the privilege of being here tonight,” he said. “I never saw so many cartoonists together in my life. In England, we only have a few cartoonists, and when we meet, it’s in a taxi.” Low had just spent several days with President Truman’s entourage, observing election year preparations, so he made a few remarks about American politics (“your politics are more of a sporting event”) and then concluded with an anecdote about after-dinner speaking. “George Trubey and I were dining one night, and Mr. Churchill was present. George doesn’t like public speaking and said, Whenever I have to talk, I feel as though I had a cake of ice four-by-six resting on my stomach. Churchill said, By God, same size as mine. If ever you come to London,” Low finished, “be sure to look me up. I shall be most happy to see you. I will never forget this evening.”

“We shall never forget this evening either,” said Caniff, resuming the rostrum. “We thought when you got back to England and in the lonely hours when you were sitting there trying to think up some ideas, it would be nice if you had a reminder of your visit to the National Cartoonists Society. We thought of many things and finally came up with this–the sword of our trade,” and he flourished a silver-plated T-square. “It is inscribed to you as follows: To David Low, whose pen melts borders and spans oceans, from his friends in the National Cartoonists Society, U.S.A., New York, June 17, 1948.”

But the biggest event of the Society’s summer was the New York showing of the NCS Exhibit at the Town Hall on West 43rd Street, August 17-29. Although New York was but the next scheduled city in the Exhibit’s national tour, the Manhattan stop provided the cartoonists with the opportunity for scoring propaganda points in the struggle with their critics. In press releases, the Society touted the show as a refutation of John Mason Brown’s charge on the “Town Meeting of the Air” that comics were major contributors to making “the brain the most unused muscle in the United States.” As President of the Society (and as chairman of the Exhibit), Caniff was quoted in the Editor & Publisher article on the exhibition: “We just want to show,” he said, “that all the pyschiatrists anxious to make a buck are saying about the comics on the radio isn’t true—that we’re not all blood-thirsty goons.” The Exhibit now displayed the best work of about 120 cartoonists—comic strip and comic book artists, gag and “serious editorial” cartoonists, and animators. And the best work of such an array of professionals was not just amusing: it was also often socially useful and otherwise civilizing.

But Caniff and his minions were not content to let the show itself make their point. They used the Exhibit as a platform for mounting other good works. Proceeds from admission charges went to the Cancer Fund. Throughout the 12-day run of the show, cartoonists appeared daily to act as hosts and to do impromptu chalktalks. And they arranged special performances for various deserving groups. On the day before the official opening of the exhibition, there was a “preview” for a group of disabled servicemen, and Caniff and Goldberg and fifteen other cartoonists did a reprise of the kind of chalktalk they’d done during the War. Later, they did special chalktalks for underprivileged children. And these efforts were not in vain. They generated favorable publicity for the Exhibit and for cartooning in national periodicals—Time, Newsweek, even Variety —and in every important New York newspaper— Daily News, Herald Tribune, Post, Sun, World-Telegram, Journal-American, even the pontifical New York Times.

For all the public relations purposes for which it had been designed, the NCS Exhibit was a success. It resumed its national good will tour the next month in Chicago, but nowhere would it achieve the splash it created that August in the Town Hall in New York.

Since their hospital tours during the War, the cartoonists had been happy to wield their talents on behalf of benevolent enterprises. They had continued the hospital shows after the War, and that fall, NCS would start giving cartooning lessons to hospitalized veterans under the auspices of the American Theatre Wing. Later, NCS would sponsor an annual cartooning contest among permanently disabled vets as part of the Hospitalized Veterans Writing Project. NCS awarded the winners modest cash prizes and prevailed upon Albert Dorne’s Famous Artists correspondence school to donate drawing equipment and a complete course of study. Such endeavors attracted NCS participation for their inherent worthiness, and although the experience of the Town Hall exhibition convinced the cartoonists of the public relations value of such charitable acts (particularly in times of hostile publicity about comics), most of the NCS projects in this arena, by their very nature, generated little public notice. But when the Treasury Department launched another savings bond drive the next fall, the cartoonists threw themselves into it for all the publicity they could generate.

And at Bellevue Hospital, the year wound down in its usual uneventful way in every ward except the one in which juvenile boys were being held for thirty days’ observation. The week before Christmas, the institutional routine in these rooms was disrupted by Russell Patterson and a few of his NCS cohorts, who came in to decorate the walls. Patterson came away resolved to do what he could. As a first step, he reported his Bellevue experience at the next NCS meeting and was named chairman of a committee to develop an anti-juvenile delinquency program.

The enduring concerns of the Society as well as some of the various projects set in motion while Caniff was President were evident in the organization’s committee structure. In addition to such standard committees as Membership and Dinner Program, there were committees for the Veteran’s Hospitals Programs, for Government Projects (like selling savings bonds), and for the NCS Exhibition. Newer committees worked on the Anti-Juvenile Deliquency Program, Public Relations (an adjunct to the Newsletter, both under Alfred Andriola), and the Yearbook (a proposal to publish annually a collection of cartoons drawn by members as a money-raising project to finance the purchase of a clubhouse for the Society). And Caniff would soon solve the Newsletter’s perennial identity crisis by divorcing features from news. That spring, he started The Cartoonist, a quarterly magazine of feature articles, edited by Greg d’Alessio.

ONCE AGAIN IN THE FALL of 1949, NCS was cooperating with the Treasury Department in a drive to sell savings bonds. But this time, the Society had volunteered to send its members out on the road. It was an ambitious undertaking: a nation-wide tour stopping for three or four days in each of seventeen major cities. The road show itself consisted of teams of ten or twelve cartoonists each and a traveling display, “20,000 Years of Comics,” a 95-foot-long pictorial history that traced the development of the comic strip from cave wall scrawls to the present. In each city, a resident member of the Society worked with a sponsoring newspaper to arrange exhibit space for the display and a schedule of performances for the cartoonists. They gave chalktalks and touted bonds before civic groups, clubs of all descriptions, schools—anywhere they could find an audience.

For each of the roadshow teams of cartoonists, the tour lasted two-three weeks. A few of the cartoonists had worked ahead of their deadlines enough to relax between shows, but most of them worked in their hotel rooms into the wee hours at night, finishing weekly batches of strips. Caniff even wrote dialogue and penciled strips while on the plane between stops. It was a grueling schedule, a hectic time. And Caniff, as NCS President, appeared with more than one of the touring teams. Moreover, he worried about the itineraries in each city and kept in contact with the local chairmen throughout the two months that NCS teams were on the road. When it was over, he was exhausted. And then another troubling matter reared its head.

In the midst of the bond tour, Caniff had received a letter from Hilda Terry, wife of the Society’s secretary, Greg d’Alessio, and created of Teena, a comic strip about teenagers. Terry was writing as spokesperson for several women cartoonists, who had had about all they could take of the male exclusivity upon which the Cartoonists Society had been so defiantly founded. A social club for the boys had been all right, she pointed out, but the more visible the club became as a professional association, the more damaging it was for women cartoonists to be excluded from membership. Terry presented the argument concisely, and its logic was unassailable: “... your organization displays itself publicly as the National Cartoonists Society, and since there is no information in the title to denote that it is exclusively a men’s organization, and since a professional organization that excludes women in this day and age is unheard of and unthought of, the public is therefore left to assume, where they are interested in any cartoonist of the female sex, that said cartoonist must be excluded from your exhibitions for other reasons damaging to the cartoonist’s professional prestige, we therefore most humbly request that you either—alter your title to the National Men Cartoonists Society, or confine your activities to social and private functions, or discontinue, in effect, whatever rule or practice you have which bars otherwise qualified women cartoonists to membership for purely sexual reasons.” (This adventure is rehearsed in more detail in Harv’s Hindsight for November 2000.)

Caniff read the letter to the October 26 meeting of the Society. The gender restriction wasn’t simply a question of custom: the Society’s constitution laid down the rules of eligibility for membership, specifying that “any cartoonist (male) who signs his name to his published work” could apply for membership.

The November Newsletter printed Terry’s letter and a coupon for members to return, expressing their opinions on the question of women in the ranks. Women were overwhelmingly approved for membership. A vote conducted at the same meeting validated the opinion poll. And Hilda Terry was promptly put up for membership, the first woman candidate. Later, Mike Angelo in Philadelphia read the report of the meeting in the December Newsletter, he did his duty as a member and went out recruiting. He asked the well-known magazine gag cartoonist Barbara Shermund if she’d be interested in joining. She was, so Angelo sent her name in to the Membership Committee, the second woman candidate.

The Membership Committee, following its prescribed routine, reviewed the qualifications of all applicants for membership and then submitted the names of those who passed muster to the entire membership for a vote. At the regular meeting at the end of December, Alex Raymond, chairman of the Membership Committee, reported on the most recent of the Committee’s deliberations:

“We held a referendum in this Society about women members,” he said. “We voted and gave them the privilege of joining. I believe that we should admit people for professional ability alone. We must now vote upon the candidacy of women as they are received by my committee. We will treat them as the men.”

NCS employed the blackball to deny membership to an individual: three negative votes were enough to end a person’s quest for membership in the Society. Astonishingly, both Terry and Shermund received three negative votes. The issue of feminine membership, which everyone thought had been settled at the November meeting, was suddenly, rudely, re-opened. When the results of the balloting were announced at the January 25 meeting, the room exploded.

The issue was not decided quickly. It took months. Another referendum was conducted. This time, seventy percent of the membership voted, and two-thirds of them endorsed the idea of membership for women cartoonists. At the May meeting, they decided to vote on the women candidates at the June meeting, and in June, women were at last formally admitted to membership in the National Cartoonists Society. Subsequent to approving Terry and Shermund, the Membership Committee had also approved Edwina Dumm, whose Cap Stubbs and Tippie, a folksy strip about a boy and his dog and his grandmother, had been warming hearts with gentle humor since 1918. All three women became members in June. But another crisis was coming to a head.

AL CAPP HAD ALWAYS advocated a more activist agenda for the Society, and he had begun in December 1949 to make his case in the Newsletter as well as at the meetings he attended, calling for “the welding of the Society into an honest and solid craft guild” that would pressure syndicates into making more equitable contractual agreements with cartoonists.

As a first step towards rectifying the situation, Capp urged that the Society engage an attorney to analyze the prevailing contractual relationships between cartoonists and syndicates and that a three-person task force be appointed to pursue the project aggressively. His proposal energized the discussions in the Society’s meetings and in the bar after the meetings. Although no one could quarrel with the need to do something about their indentured status, not everyone agreed with the unionist tactic that inspired Capp’s call to action. Caniff felt his friend wasn’t being very realistic.

Caniff was sympathetic to Capp’s intentions, but he saw the Society as a pressure group not as a union. Through the collective stature of the names of its most celebrated members, he believed, the Society had influence. At the same time, he wished that NCS could do more than it was able to on behalf of its members and the profession.

Caniff appointed the task force that Al Capp lobbied for, and he made Capp the chairman of the group. But when Capp insisted that the objective of their deliberations should be some sort of union-like action, he met with disagreement and soon withdrew from the chairmanship—indeed, from all participation in the activities of the Society. He remained a member, but he had lost his enthusiasm.

The Society, however, continued to be concerned about the contractual relationships between cartoonists and syndicates even without Al Capp’s driving influence. The charge given to the task force was eventually assigned to a new committee, the Ethics Committee. And the group developed a model document that defined a more desirable situation for syndicated cartoonists. Bearing the NCS imprimatur, the model contract helped shape a new, more equitable working arrangement between many of the creators of features and their distribution partners.

At the end of March 1950, Caniff relinquished the presidential gavel to his successor. And Alex Raymond—creator of Flash Gordon, Jungle Jim, Secret Agent X-9, and, after the War, Rip Kirby—was, indeed, a successor worthy of the name. Raymond, like his predecessor, would bring dedication to the job, and in representing cartoonists to the outside world, he would lend dignity to the profession.

Raymond had been a major in the Marines during the War, and he brought to his task as NCS President a military flair for order and organization. He rearranged the Society’s casual committee structure, carefully defining the task of each committee and creating three new committees: Education, Ways and Means, and Ethics. The Education Committee was to aid educators outside the profession in fostering appreciation for the medium and to create a program of instruction in art and humor and storytelling for the members of the Society. The Ways and Means Committee was charged with devising ways to assist all kinds of needy cartoonists—the sick and destitute, the young and worthy. To the Ethics Committee fell the task of developing a “fair practices” code for the conduct of affairs between cartoonists and their syndicates. In addition, the Ethics Committee was to “outline a code of ethics for cartoonists covering their responsibilities to the public and to one another in the performance of their work.” The code should include a stand “against offensive depiction of brutality, obscenity, or anything deleterious to public morals.” The Ethics Committee also investigated complaints of unethical behavior—complaints about the practices of syndicates and other buyers of cartoons, about fellow cartoonists whose conduct may have brought discredit upon the profession. Eventually, the members of the Ethics Committee were all past presidents of NCS.

Raymond led NCS to a greater awareness of itself as an organization, and he thereby gave the Society a sharper sense of purpose. And his leadership came at just the right moment: by the time he became President, the Society had grown enough to need precisely the kind of self-consciousness he nurtured in it. NCS had outgrown its purely social function and was coming into maturity as an organization. That it was still in existence at all, though, was due in large measure to Milton Caniff.

Caniff’s involvement with the Cartoonists Society scarcely ended with the expiration of his second term as President. At Raymond’s invitation, he had a seat on the Board of Governors, and, with other past presidents, he served on the Ethics Committee for years. But in addition to such official capacities as these, he retained a nearly paternal interest in the Society for the remainder of his life—a paternal interest of the advisory but non-interferring sort. His influence was continuous, steady. He wrote thoughtful notes to officers suggesting ideas for dinner programs, special events or projects, guest speakers, members who might deserve special recognition, and the like. And after Rube Goldberg died in 1970, Caniff was elevated to a position akin to that which had been created for Rube—Honorary Chairman. This succession had the ring of poetic justice about it: the National Cartoonists Society could not have been started without Goldberg, and it might very well never have survived and matured without Caniff.

This anecdotal history of the founding of the National Cartoonists Society is taken from Meanwhile: A Biography of Milton Caniff, by yrs trly, Robert C. Harvey, published by Fantagraphics (only a few copies left; buy yours here or at Fantagraphics.com).

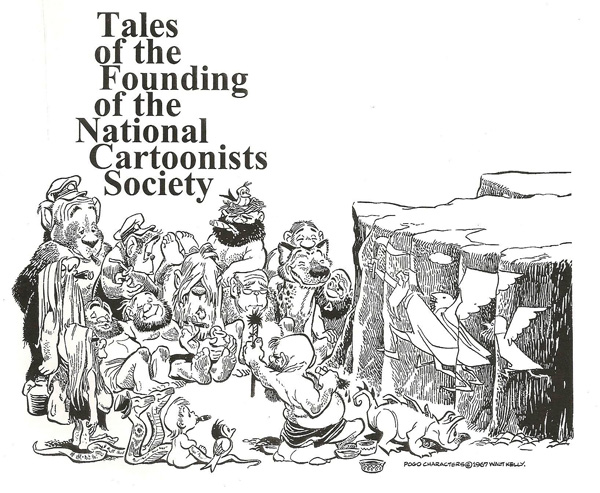

A longer version of the tale, richer in hilarious anecdote, can be obtained in my monograph Tales of the Founding of the National Cartoonists Society (20 8x11-inch pages), profusely illustrated with numerous self-caricatures of the principals and other decorations, rare almost never-before-seen art from the annals of NCS; merely $12, including p&h. Write to the Happy Harv for purchasing details.