|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Opus 345 (October 30, 2015). This voluminous, copiously illustrated posting, open to all comers without entry fee or any other charge, includes these topics: Atena’s virginity test, Playmates denuded, a new but different comic-con, free speech over the last 10 years, Roy Crane defended, Jan Eliot retires Stone Soup, politics in strips, and the Pope Francis comic strip, plus reviews of comic books—Twilight Children, Mockingbird, Dr. Strange; and books— Mad’s Original Idiots, Milt Gross’ New York, Comics (A Global History), King of Comics, Walt Kelly’s Fairy Tale Parade, The War to End All Wars, and some of the best of last month’s editoons and obits for Murphy Anderson and Roger Bollen—and more, much more, all of which is listed immediately below. The purpose of the list (for those who’ve just joined us) is to make it easier for you to find what you might want to read about without having to wade through the whole magilla of topics you’re not interested in, one at a time. You don’t want to countenance my ranting about political issues under the heading of Editoonery (a review of some of the best editorial cartoons this month), fine; just skip over that when you’re scrolling through the posting. Does the 100th anniversary of King Features interest you? Fine, when you come to that book review as you scroll through this posting, stop and read. Are you a fan of Walt Kelly? Good, you can find a review of the latest compilation of Kellyworks, his Fairy Tale Parade, in the list; you’ll want to scroll down (quickly bypassing other topics) until you come to it. Want to see what the “new” Dr. Strange looks like? Excellent, just roll down the scroll until you come to that review under the heading Funnybook Fan Fare. Now, get started. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department, starting with the News Department (Nous R Us, get it?)—:

NOUS R US The Latest Assault on Decency in Iran Playmates To Put Their Clothes Back On How Opus Came Back New Comic-Con Is a Success in Columbus A Really Super Girl onTV

ODDS & ADDENDA Zunar Lecturing and Exhibiting in England Wimpy Kid on Tour New York Con Grows Graphic Novel Sales Have Biggest Year Graphic Novels on Banned Books List The Real Betty in Archie’s Adventures Peanuts Stamps for Christmas Denver Zombie Crawl

Free Speech Examined in the Wake of Danish Dozen: A Progress Report

PULP PROPAGANDA Jeet Heer Says Roy Crane Is a Propagandist (And I Have a Snit About It)

RANCID RAVES TRAVELOGUE Finding Abe Martin in Indiana

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Reviews of—: Twilight Children Mockingbird Paper Girls Beyond Belief Miracle Man Fred Hembeck Returns Dr. Strange Miami Vice Remix

EDITOONERY Some of the Month’s Best Editorial Cartoons

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Cartoony Visuals Taking Over

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Politics in Comics Only in the Comics Some Historic Moments

The Jan Eliot Story Retiring Stone Soup Creator Tells All

A Comic Strip Pope?

BOOK MARQUEE Book Reviews and Previews of—: Mad’s Original Idiots: Wally Wood, Jack Davis, Bill Elder Bill Griffith’s My Mother’s Love Affair Graphic Novel Peter Kuper’s Ruins The Multiversity Deluxe Edition

BOOK REVIEWS Milt Gross’ New York: A Lost Graphic Novel Comics: A Global History, 1968 to the Present King of Comics: 100 Years of King Features Walt Kelly’s Fairy Tales

LONG FOR PAGINATED CARTOON STRIPS (Graphic Novels) The War to End All Wars: World War One, 1914-1918 ONWARD, THE SPREADING PUNDITRY Some Things To Be Happy About

PASSIN’ THROUGH Murphy Anderson Roger Bollen Yogi Berra

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

THE LATEST ASSAULT ON DECENCY Iranian Cartoonist Tested for Virginity By Comic Book Legal Defense Fund’s Maren Williams Iranian cartoonist Atena Farghadani, currently serving a nearly 13-year prison sentence for caricaturing members of parliament as animals, last week faced trial on the further charge of “non-adultery illegitimate relations” for shaking the hand of her lawyer, Mohammad Moghimi. Moreover, Amnesty International recently learned that Farghadani was forced to undergo virginity and pregnancy tests in August, purportedly as part of the investigation. Contact between unrelated members of the opposite sex is technically illegal in Iran, but rarely prosecuted. Moghimi is also charged, and both parties could receive sentences of up to 99 lashes if convicted. In a note leaked from prison, Farghadani said that she was taken to a medical center on August 12 and subjected to a virginity test against her will. Such tests are carried out by physically checking for the presence of a hymen, and are recognized by the World Health Organization as a form of sexual violence. In addition to the assault, Farghadani also reports that she has been the target of “lewd gestures, sexual slurs and other insults” from prison guards and officials since the “illegitimate relations” charge was introduced in June. Farghadani was first arrested last August (2014) for her cartoon mocking members of parliament as they debated a bill to ban voluntary sterilization procedures such as vasectomies and tubal ligations in an effort to reverse Iran’s falling birthrate. But even before her arrest, she was already well-known to the government for her fearless advocacy on behalf of political prisoners, Baha’i minorities, and the families of protesters killed after the country’s presidential election in 2009. When Farghadani was released on bail while awaiting trial, she promptly uploaded a video to YouTube detailing abuses she suffered in prison including beatings, strip searches, and non-stop interrogations. She was rearrested in January and finally received the draconian sentence after a perfunctory jury-less trial in late May. Last month, she was honored with the 2015 Courage in Editorial Cartooning Award from Cartoonists Rights Network International. A judge is expected to rule on the “illegitimate relations” charges against both Farghadani and Moghimi this week.

PLAYMATES TO PUT THEIR CLOTHES BACK ON The big news of the month was the announcement that, starting with the March 2016 issue, Playboy will no longer publish photos of completely naked women. They’ll be somewhat undressed but not entirely. In plainer language, they’ll still be nearly naked. For the magazine that got famous by picturing naked women and then catapulted that fame into notoriety by neglecting to airbrush pubic hair out of the pictures, the announcement was a jolt just this side of volcanic. Even more shocking, 89-year-old Playboy founder/publisher Hugh Hefner, crusader for the sexual revolution in the 1950s, agreed to the nefarious plan to drop the full nudes. The Internet is the reason for this seeming descent into uncommon modesty according to Playboy CEO Scott Flanders, quoted by the Associated Press and others: “You’re now one click away from every sex act imaginable for free,” he said, “and so it’s just passe at this juncture.” But that seems suspicious to me. I think Larry Flynt, founder/publisher of a Playboy rival, Hustler, is closer to nailing the truth of the matter. (He denies, by the way, that Playboy is a competitor. “My only competitor is Gynecological Monthly,” he sniffed.) He thinks dropping nudes is a terrible mistake: “What made Playboy popular to begin with?” he asks, rhetorically. “It wasn’t the interviews. It wasn’t the editorial content. It was the centerfold. They’re taking out the main event. It just doesn’t make sense.” Flanders says Playboy’s new approach with more serious articles aims at more affluent young men. “That’s the wrong approach,” said Flynt. “You have to have broad demographic appeal if you’re going to publish a magazine. They don’t have the truck drivers. They have the college professors. They’re narrowing their demographic. You need a broad demographic to get a maximum circulation. “I think they’re losing money, and [the new nudeless approach] is a sign of desperation,” he continued, as reported at money.cnn.com. “There were a lot of advertisers that Playboy could never get because they had nudity. They take the nudity out, and they think they’re going to get more advertisers. But you take the nudity out, you lose the demographic and you can’t get advertisers [without that demographic]. So it’s a bad business decision.” Playboy has been in trouble for some time. It’s circulation, 5.6 million at its height in 1976, has dropped to about 800,000, reported Reuters. Page count has steadily eroded over the last dozen years, standing, today, at about 126 pages per issue. According to Megan McArdle at Bloomberg View, “Playboy’s American print magazine now loses millions of dollars a year, and is essentially a loss-leader for the Playboy brand, which is licensed hither and thither across the globe.” The competition for Playboy is no longer Playboy imitators (Dude, Gent, Jem, Penthouse), few of which remain. The competition is the laddie magazines—Maxim, King, FHM, Gear, Stuff, Open Your Eyes, etc. And Playboy has attempted to meet the competition by revamping its opening pages: they are now sprinkled with short, paragraph-long articles and squibs of information, snatches of statistics, and graphics—just like the laddie mags. These adjustments apparently haven’t revived the magazine’s circulation. So the editors plan a major overhaul, beginning with the March 2016 issue. Bulkier, heavier paper to make it seem more magazine than it is. And more in-depth articles. In

the midst of so much more, there will be a conspicuous less. Less female skin.

Still sexy, though, they vow. By way of demonstrating how sexy a nearly naked

woman can look, here are a few pictures clipped from the magazine (including a

recent cover!), plus the latest advertisement for the Playboy calendar

(which, the ad notes, will “include full nudity’). So

the denuding at Playboy has already started. It makes me wonder, though,

whether the same dictum will apply to cartoons in which young female embonpoint

has usually been a visual factor. Dean Yeagle, f’instance, is an expert

at it (as we can plainly tell in the adjacent visual aid). The move to clothe erstwhile nudes began with a suggestion from top editor Cory Jones. “Don’t get me wrong,” he protested, “—the twelve-year-old me is very disappointed in the current me. But it’s the right thing to do.” The “right thing”? What’s right about it? Playboy dropped full nudity at its website in August 2014. And visits increased from about 4,000 to about 16,000. With that statistic as harbinger, the next step was clear to Jones and to the other bean-counters at Playboy: do away with nudity. Whether this move will result in discontinuing the iconic centerfold is not, at the moment, known. At least, not known by me. Clearly, barenekkidwimmin are no longer as hot as they once were. If sex is the next thing to go out of fashion, there’ll soon be no readers for Playboy. Or for any other magazine. While I fear for the continuation of the human species, I fear more for the fate of cartooning. Playboy is one of the two remaining regular venues for single-panel gag cartooning in the U.S. (the other being The New Yorker). And if Hefner’s magazine is going for more articles—more text—in an effort to be a more serious, adult publication, then it wouldn’t surprise me to learn that cartoons will be discarded in the rush to adultery—er, adulthood and other grown-up notions and nostrums. The retreat from full nakedness has already set in, but I was still alarmed—shattered, really—by the magazine’s November issue, which just arrived. Full-page color cartoons were present in their usual abundance, but in the back of the magazine, there were no smaller cartoons, typically numbering 9-12 per issue. In November, none. Nada. Zero. After the magazine’s successful campaign to advance civilization by making sex acceptable in mixed company, it is discouraging in the extreme to think of that same crusading publication deliberately impoverishing civilization by eliminating the visual impulse to laughter about sex. A sad day indeed. But I’m just imagining the worst. Perhaps sanity, what little of it remains after turning away from completely naked women, will prevail at Playboy. Perhaps cartoons will endure—or make a comeback. I am encouraged by the recollection that Hef is an avid cartoon advocate (a frustrated cartoonist himself). Don’t give up hope just yet. Don’t give up hope for barenekkidwimmin either. As one Twitter wit noted: “I expect Trump to release a statement today that when he’s president, he’ll put the nudes back in Playboy and make the Playmates pay for it.”

HOW OPUS CAME BACK Interviewed on NPR’s “Fresh Air” about the reincarnation of Bloom County on Facebook, cartoonist Berkeley Breathed talked about why he brought back Opus and Company: “I watched slack-jawed in horror as they threw one of the 20th century's most iconic fictional heroes, Atticus Finch, under the bus. At the time—and this was a couple of months ago—it made me think that there would have been no Bloom County without Mockingbird because I was twelve I read it, and the book's fictional Southern small town of Maycomb had settled deep into my graphic imagination and informed it forever. If you look at any of my art for the past 30 years, there's always a small-town flavor to it. “So this summer,” Breathed went on, “just a couple months ago when Go Set A Watchman [Harper Lee’s “prequel” to To Kill a Mockingbird] was causing an uproar, I went back to my files and I pulled an old fan letter from years ago. It says (reading): ‘Dear Mr. Breathed, this is a plea from a dotty old lady and from others not dotty at all. Please don't shut down Opus. Can't you at least give him a reprieve? Opus is simply the best comic strip there is and depriving him of life is murder— a hard word to describe an obliteration of your creation. But Opus is real. He lives. Harper Lee, Monroeville, Ala.’ “When I pulled that out,” Breathed continued, “— I hadn't seen it for 25 years. And I choked up, and I thought about the preposterously ironic impossibility of my literary heroine from my childhood demanding that I not kill one of her fictional heroes. The universe throws us some obvious little pitches sometimes, and we need to be awake enough not to let them slip by. So that night I found the blank four frames of Bloom County from years before in my files, and I sat down to draw the first one in 30 years. And I posted it on Facebook in sort of a what-the-hell moment, and that's exactly how much careful reason sober forethought went into the whole thing. And then it exploded after that.” During the Fresh Air interview, Breathed recalled his 1987 Pulitzer and the negative reaction to it by editorial cartoonists and the alleged cold shoulder he got from the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists when he spoke at the 1988 AAEC Convention, alleging that when he stood up to give his speech at the concluding banquet, every editoonist in the room walked out in protest. I’m a member of AAEC, and I assure you that fellow members scoffed Breathed’s allegation. Those who attended the 1988 Convention remembered that everyone was eager to hear Breathed. No one walked out or boycotted his speech. Just a piece of fiction from one of the nation’s foremost storytellers. By the way (although not at all incidentally), George Gene Gustines at artsbeat.blog.nytimes.com reports that at the recently concluded New York Comic Con, IDW announced that a collected edition of the new online strips that Breathed has been posting on Facebook since July 13 will be available next summer and will join IDW’s library of Breathed’s work — the original Bloom County strips, the spin-offs Outland and Opus and Breathed’s college endeavor, Academia Waltz, some of his earliest political cartoons and more.

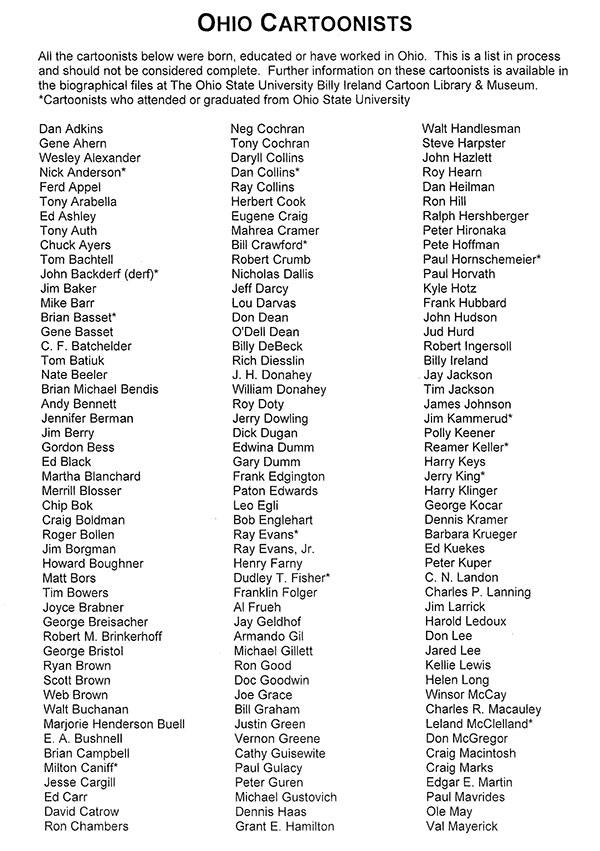

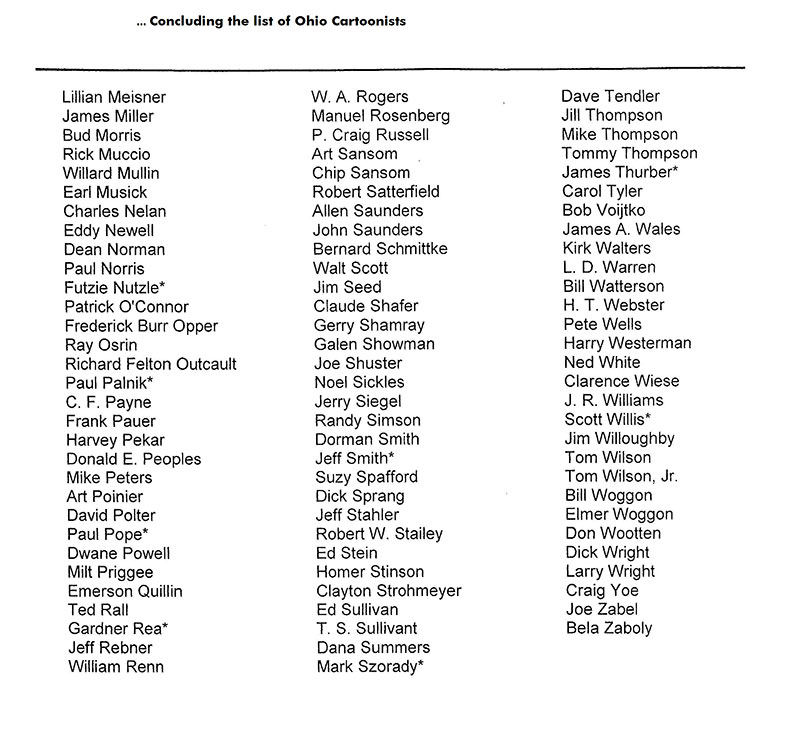

SUCCESS FOR THE NEW KID ON THE BLOCK Cartoon Crossroads Columbus is the name of the newest comic-con phenomenon. Capitalizing on Ohio as the birthplace of so many cartoonists (print out the 2-page list posted near here)

and on the Ohio State University’s Columbus campus as host of the world’s largest archive of original cartoon art and historical information, the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum, CXC (as it styles itself) was formed by Jeff Smith (creator of Bone), Lucy S. Caswell (retired curator and nurturer of the Ireland Library—once, at its beginning, simply the Milton Caniff Research Room)—Vijaya Iyer (Smith’s wife and business partner), and Tom Spurgeon (former managing editor of the Comics Journal and host of his own comics blog, ComicsReporter) to take advantage of the venue to celebrate the arts of cartooning. I suspect in the back of their collective mind there lurks a hope that CXC will become the Angouleme of America; but I may be reading too much into all this. An estimated 1,200 people attended the inaugural weekend of the event, October 1-3. CXC featured presentations and interviews with a host of comics creators—including Art Spiegelman (Maus), Kate Beaton (Hark! A Vagrant), Lalo Alcaraz (La Cucaracha), Bill Griffith (Zippy), Jaime Hernandez (Love and Rockets), Francoise Mouly (RAW and The New Yorker), Craig Thompson (Blankets and Habibi), Jerry Beck (renowned animation historian), Derf Backderf (My Friend Dahmer and other graphic novels), Grace Ellis (comic books, Lumberjanes), Dylan Horrocks (comic books, Hicksville), Jeff Lemire (comic books, Descender, Essex County Trilogy), Rafael Rosado (animation), Katie Shelly (altie comics), and others. “What makes this show unique is Columbus itself,” said Smith, CXC’s President and Artistic Director. “We have unprecedented levels of institutional support for cartooning and comics here, from the museums and schools to the Thurber House with its annual Graphic Novelist in Residence, which recognizes outstanding new talent.” Looking around at the institutional engagement in cartooning arts over the last several years, Smith said: “It feels like this is the moment to try to grab that energy.” He continued: “The reason I wanted to do this is because half of my life is drawing in my studio and the other half is going out to comic book festivals, and over 25 years, I’ve seen which parts of each show that I like the best.” And he and his cohorts set out to put the best into CXC. And more: “This festival brings the whole city into the celebration.” CXC promotional information says the event’s mission “is to celebrate the diversity of the cartoon arts, including animation, editorial cartoons, comic strips, comic books, and graphic novels, and to highlight the city of Columbus and its comics community to the world, working to secure the brightest possible future for the next generation of comics-makers.” CXC takes the place of the triennial Festival of Cartoon Art that was staged by and at the Ireland Library every third year since 1983. Said Jenny Robb, the current curator at the Ireland: “The Festival was a wonderful event, but participation was capped at 300 people. While attendees enjoyed the intimate nature of the Festival, we wished that we could find a way to allow more people to participate and to celebrate the art form.” CXC is the way. Cartoonist Derf Backderf, who, with Smith, contributed to the campus newspaper while both were undergraduates at OSU, was so eager to participate in the first CXC that he cut short a book tour that took him through the French Alps so he could attend every day of CXC, according to the columbusalive.com report of Melissa Starker. Derf has given up his long-running altie comic, The City, to concentrate on graphic novels. His first, Trash, has just been published, giving him a different perspective on the growing comics profession. “There’s a big shift going on in the comics world,” Derf said. “The 45-year-old fanboys can continue to read their beloved Marvel and DC sock-’em-ups, and more power to them, but the throng that makes up the new generation of readers is looking to graphic novels and small press and webcomics, and it’s there you’ll find truly great, groundbreaking work. We need to build a network of festivals to support these types of comics since we’re largely shut out of mainsteam comic book shops and comic cons. That’s why I’m so thrilled CXC has come on the scene. The Midwest desperately needs a major show and the association with the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum gives CXC a huge advantage.” CXC featured receptions, cocktail parties, and an exhibit. Cartoonist Batton Lash (Supernatural Law) who exhibited at CXC reports a huge success: “It hit the ground running, right out of the gate! Good size crowd from the moment the doors opened at 11am and didn't really dissipate until maybe 3:45/4pm (and the show closed at 5!). The people were just great and the association with Ohio State and the fab Bill Ireland Cartoon Art Musuem just made Jackie and I glad we decided to attend and exhibit. As for selling our books, Jackie [his wife, Jackie Estrada] did well with her Comic Book People volumes but I didn't know what to expect with Supernatural Law sales; I was afraid that the attendees were only interested in the alt/indy cartoonists (Fantagraphics, Adhouse, etc.). But I didn't have anything to worry about— I met some long-time fans as well as newbies who liked my pitch enough to give SLaw a try! Definitely will pencil CXC in for next year and I would recommend it to cartoonists and comics fans alike without hesitation!” Next year, CXC will meet October 13-16; in 2017, September 28-October 1; in 2018, September 27-30; in 2019, September 26-29. Mark your calendar; mine’s already marked.

A REALLY SUPER GIRL I watched the debut of the new “Supergirl” tv show with mixed emotions. The opening sequence, with Kara Danvers (Melissa Benoist) coming out of hiding to fly up and save a commercial airline from crashing, was nicely conceived and executed. After that, the show fell apart for me. As Benoist plays the part, Kara/Supergirl is simply too giggly. And then there’s the whole “girl”-“woman” thing. Kara’s boss, the media magnet Cat Grant (Calista Flockhart with a new puffy upper lip), dubs the flying female airline rescuer “Supergirl” in a tv news report of the event. And Kara objects: “A female superhero! Shouldn’t she be called Superwoman? If we call her Supergirl, something less than what she is, doesn’t that make us guilty of being anti-feminist?” But, as Emily Yahr reports at the washingtonpost.com, Cat responds with her best death stare: “I’m the hero!” she says. “I stuck a label on the side of this girl. I branded her. … And what do you think is so bad about ‘girl’? I’m a girl. And your boss. And powerful and rich and hot and smart. So if you perceive Supergirl as anything less than excellent — isn’t the problem you?” “You” being all the feminist viewers who might object to the girly name. “So, that speech,” Yahr continues, “seems to exist to preemptively stop real-life critics from bashing the ‘girl’ name, right? On a recent conference call with Benoist and executive producers ... [they] told us that with this scene, they wanted to echo the potential thoughts of the audience”—: “Well, she’s an adult woman—why isn’t the show called ‘Superwoman’?” Probably, I’d say, because Benoist plays the title role like a highschool girl. Yahr goes on: The word “girl” comes up several more times in the pilot (Hank Henshaw, during a fight scene: “She’s not strong enough.” Alex Danvers, Kara’s “sister”: “Why, because she’s just a girl? Exactly what we were counting on.”) But Benoist, Yahr reported, says that she doesn’t really focus on the male-vs.-female superhero angle. “I just want people to have fun watching the show and really enjoy watching Kara’s journey as much as I’m enjoying playing it. It truly, to me, does not matter that she is a girl,” Benoist said, “because she kicks some serious ass.” Exactly what a defensive high school girl would say. “She kicks some serious ass.” And then she’d giggle. Just like Benoist’s Supergirl. Why can’t she play the part like the male actors in superhero movies do, with a little adult ironic self-deprecating humor—like Robert Downey, Jr in the Iron Man flicks?

ODDS & ADDENDA The Malaysia cartoonist Zunar is presently on a lecture tour of England while awaiting his case to come to trial in his native country. Charged with nine violations of antiquated colonial sedition laws, he could face 43 years in prison if convicted. Said Zunar: “To have my cartoons exhibited in a [British] cartoon museum at a time where I am facing pressures from the government for my works is genuine encouragement, a tribute I humbly acknowledge and am tremendously grateful for.” At Amnesty International UK’s Human rights Action Center in London, he will be participating in a forum entitled “Fight Through Cartoon, Even My Pen Has a Stand.” Zunar hopes the exhibition and tour “will create awareness on the real state of affairs and the serious limitations that exist in Malaysia where freedom of expression, freedom of the media and human rights are concerned.” ■ Jeff Kinney will embark on a global tour later this year to promote the 10th book in his Diary of a Wimpy Kid series. Diary of a Wimpy Kid: Old School will be released November 3 in the U.S. by Abrams’s Amulet Books imprint, triggering a tour with stops in 15 cities on five continents, including New York, N.Y.; Boston, Mass.; Tokyo, Japan; Beijing, China; Sydney, Australia; Madrid, Spain; London, U.K.; Lisbon, Portugal; Frankfurt, Germany; Athens, Greece; Istanbul, Turkey; Bucharest, Romania; Amsterdam, the Netherlands; Riga, Latvia; and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Said Kinney: “One of the biggest surprises of my life is that kids from all over the world seem to relate to Greg Heffley and his comic struggles. What I’ve learned is that childhood itself is a universal condition that transcends culture and language.” ■ The 2015 New York Comic Con, October 8-11 at the Javits Center, was the biggest yet, with 169,000 tickets sold—“up from 151,000 in 2014,” reported Heidi MacDonald and Calvin Reid at publishersweekly.com. That surpasses the San Diego Comic Con by at least 30,000. The increase in ticket sales, however, “ was due to event organizer ReedPop making Thursday a full day—more tickets were sold— and selling more one-day passes instead of multiple day passes, according to ReedPop global senior v-p Lance Fensterman.” ■ Despite a slight summer slump, graphic novel sales are still on the rise, according to the annual ICv2 report, yielding “the biggest year ever in 2014 with an estimated $460 million in sales, via both comics shops and traditional retailers,” said Heidi MacDonald at publishersweekly.com. “Bookstore sales hit an all-time high at $285 million, surpassing even the manga boom of the mid-Aughts,” she added. “Female readership also continues to grow: Comixology reported that the percentage of their new customers that was female had doubled over the last two years, up to 30% of new customers, from 20% in l2013.” ■ In early October comes Banned Books Week, for which the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom produces its annual “Top Ten Most Frequently Challenged Books” list. Three graphic novels are on this year’s edition: Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis (its offense: gambling, bad language, political viewpoint), Raina Telgemeier’s Drama (candid depiction of homosexuality, “a very chaste scene of two boys kissing”), and This One Summer by Marilko and JilllianTamaki (miscarriage, teen pregnancy, profanity)—all books “marked by both high quality and high popularity,” said Michael Cavna at ComicRiffs, “the latter certainly a function in drawing fire.” While it is alarming to notice how frequently graphic novels that are popular with young readers are making the ALA list, this year’s roster is based upon only 311 complaints “made formally in writing.” That’s not a big number, 311, out of the millions of books being read by millions of young people. Still, it’s sad to realize how active and dedicated some would-be censors are. ■ The original of Betty, the girl next door to Archie Andrews, is Betty Tokar Jankovich, once a girlfriend of cartoonist Bob Montana, who invented the Riverdale gang, according to George Gene Gustines at nytimes.com. Discovered by journalist/documentarian Gerald Peary, a passionate Archie fan who set out to find all the inspirations for the Archie characters, Ms. Jankovich at 94 remembers dating Montana. After graduating from high school, she and her sister Helen worked in a cafeteria in the same building that housed MLJ Comics. They met Montana and Harry Lucey, another Archie cartoonist, and they went out on a double date, after which, the couples switched partners, Lucey dating Helen, whom he eventually married. Betty, meanwhile, soon broke off with Montana: “I really liked him,” she said, “but I didn’t think I would be much of an asset to his career—I wasn’t educated enough for him. So we broke up and went our separate ways.” She eventually married the police chief of Perth Amboy. Montana, Betty said, “had a very nice life, and I married a very nice young man. It turned out beautifully.” ■

Just in time for Christmas, the U.S. Postal Service is offering Christmas

postage stamps celebrating a 50th anniversary—namely, scenes from

1965's “A Charlie Brown Christmas,” the first tv show deploying Charles

Schulz’s beloved comic strip characters. ■ Denver hosted the 10th annual Zombie Crawl on downtown’s 16th Street Mall on October 17. Thousands lurched along the street in bloodied clothing and decayed facial make-up in what was billed as the largest event of its kind. That so many took part helps explain the success of comic-cons: these days, people apparently love dressing up to assume the role of their favorite character, and comic-cons give them all the excuse they need so they attend in droves, converting what once were venues for collecting comic books into costume parades.

FREE SPEECH IN THE WAKE OF THE DANISH DOZEN September 30, 2015, marked the 10th anniversary of the publication of twelve cartoons depicting the Prophet Muhammad in Danish Newspaper Jyllands-Posten, an editorial decision that would ignite a global battle of values over the relationship between free speech and religion that is still ongoing, reported Jacob Mchangama in Copenhagen in early October. Said he (in italics)—: On one side of this conflict are those who insist that free speech includes the right to offend any idea, religious or secular, and that tolerance means putting up with those expressions that you most despise. On the other side are those who believe that religion, and in particular Islam, must be protected from scorn and mockery, a small minority of whom are willing to use violence to enforce a “jihadist’s veto.” In between are the many members of what Salman Rushdie has called the “but-brigade,” people who are formally committed to free speech, but for whom a commitment to tolerance and social peace means imposing society-wide norms of self-censorship on ideas that may offend or hurt members of religious or ethnic groups. In a world where, according to Freedom House, only 14 percent of the population live in states with free speech, and where respect for press freedom is at its lowest point in more than 10 years, the stakes of this battle are very high indeed. Will the hard won freedoms of conscience and expression prevail, or will even liberal democracies internalize a sugar-coated version of the red lines of the “jihadist veto?” Fleming Rose, the newspaper’s editor who commissioned the cartoons as a way of testing the extent of Islamic intimidation of freedom of the press, was immediately a pariah, an Islamophobe, a thoughtless and primitive bigot. One of his foremost critics was presented with a prestigious award for his “courageous statements [criticizing Rose] in the Cartoon Affair.” Since then, Mchangama said, “at least five serious terrorist attempts against Jyllands-Posten and some of the main protagonists of the cartoon crisis have been thwarted, including a plot masterminded by American-Pakistani terrorist David Headley that included plans to behead as many Jyllands-Posten journalists as possible and throw their heads on to the street below. These events, and the subsequent attack against Charlie Hebdo, which reprinted the Danish cartoons in 2006, have had an effect on intellectuals and public opinion.” But times change. In 2015, Fleming Rose received the same award that his critic had received in 2006, the presentation calling Rose “a strong and central actor in the international debate on free speech,” defending a “principled” and “nuanced” stand. And opinion polls show a corresponding change. In 2006, 43 percent of the Danish population supported Jyllands-Posten’s decision to publish the cartoons, with 49 percent opposed. In January 2015, shortly after the attack against Charlie Hebdo, the ranks of the supporters had swollen to 65 percent, with only 17 percent opposed. For a month or so we were all Charlie, and several of Jyllands-Posten’s former detractors now acknowledged that in fact there was a threat against free speech from radical Islamists. But “things changed again the following month,” Mchangama said. The attack on a free speech debate and a synagogue in Copenhagen by an Islamist gunman on February 14 this year, resulting in two fatalities, ushered in fear once again. “While the Charlie Hebdo affair put the but-brigade on the defensive, the events on February 14 in Copenhagen gave it new life.” Journalists were told not to show any of the Muhammad cartoons. Lars Refn, chairman of the Danish Association of Cartoonists, told a newspaper that no media would ever be allowed to republish the cartoons again, since it would amount to “a terrorist attack against all Muslims in the world.” That’s 1.6 billion people. Mchangama reported that a Danish school leader said the cartoons should not be included in school books, even when the cartoon crisis was part of the school curriculum, since it might “provoke” Muslim children. The leader “did not explain why it was more important to protect the religious feelings of Muslim children than, say, the feelings of Jewish children confronted with pictures of swastikas or the Holocaust in history books on World War II; or why no ban exists on black school children being confronted with pictures from the dark days of slavery. “Outside Denmark the sugar coating of the ‘jihadist’s veto’ has also taken hold,” Mchangama said. “On October 1, PBS’s Newshour aired a piece on the anniversary of the cartoons (in which both Flemming Rose and I appeared). In an ‘editor’s note,’ the news anchor explained that PBS has a “policy of not showing images of the prophet Muhammad,” since they are “offensive” to some viewers. Yet when in June PBS covered the fallout from Donald Trump’s derogatory comments on Mexicans, Newshour had no qualms about quoting verbatim from Trump’s comments, although they were clearly offensive to many Mexicans.” The absurdity of such policies becomes apparent when the spokesperson for the Islamic Society of Denmark “insists that one should not ‘force people’ to be ‘humiliated’ and ‘dishonored’ [by publishing the cartoons]. Yet on several occasions the ISD have hosted Islamic scholars such as Haitham Al-Haddad, who has called for the stoning of women and called homosexuality ‘a crime’ and ‘a scourge.’ So while [the spokesperson] is happy to use freedom of expression and religion to spread ideas deeply offensive toward women and gays, he wants a ‘but’ inserted when it comes to Islam, and news media — from Denmark to the US — have complied.” Mchangama concluded: “There can be little doubt that the past 10 years have proven Flemming Rose right when on September 30, 2005, he wrote that ‘the public debate is being intimidated,’ and warned that ‘we’re on a slippery slope, where no one can predict what the result of self-censorship will be.’ Fortunately, the prescience of Rose’s prophecy has had a salutary effect on public opinion. But whether it will be enough to conquer the fear that has paralyzed editors and newsrooms is yet to be seen.”

Jacob Mchangama is the executive director of Justitia, a Copenhagen-based think tank focusing on human rights and the rule of law. He has taught international human rights law at the University of Copenhagen and written on human rights in Foreign Policy, Foreign Affairs, Wall Street Journal Europe and The Times.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com/comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

READ & RELISH From Over the Internet Transom: an interesting turn of events in Mt. Vernon, Texas ... Diamond D's brothel began construction on an expansion of their building to increase their ever-growing business. In response, the local Baptist Church started a campaign to block the business from expanding— with morning, afternoon, and evening prayer sessions at their church. Work on Diamond D's progressed right up until the week before the grand re-opening when lightning struck the whorehouse and burned it to the ground! After the cat-house was burned to the ground by the lightning strike, the church folks were rather smug in their outlook, bragging about "the power of prayer." But late last week "Big Jugs" Jill Diamond, the owner/madam, sued the church, the preacher and the entire congregation on the grounds that the church ... "was ultimately responsible for the demise of her building and her business— either through direct or indirect divine actions or means." In its reply to the court, the church vehemently and vociferously denied any and all responsibility or any connection to the building's demise. The crusty old judge read through the plaintiff's complaint and the defendant's reply, and at the opening hearing he commented: “I don't know how the hell I'm going to decide this case, but it appears from the paperwork, that we now have a whorehouse owner who staunchly believes in the power of prayer, and an entire church congregation that thinks it's all bullshit."

PULP PROPAGANDA Roy Crane’s Buz Sawyer comic strip was famous for adventurous battles against Ameria’s Cold War foes. But no one knew that the U.S. government was behind it all. WITH THE WORDS ABOVE, the New Republic headlines and annotates a 6-page article by Jeet Heer in its November issue. That’s this November, November 2015. That’s 72 years after Crane launched Buz Sawyer, 68 years since the commencement of the Cold War, and about 24 years since the Cold War ended with the dissolution of the USSR. How Heer managed to convince his editors at the magazine that this piece of ancient history was pertinent enough today to expend 6 pages on I’ll never know. Heer has been writing about cartooning and comics from a Canadian homebase for a couple decades, and he has lately surfaced as a “senior editor” at the New Republic (which, itself, has undergone a change in design and emphasis if not focus). Dunno what “senior editors” do, but I suspect it less to do with editing and more to do with producing articles regularly, which Heer does with numbing frequency. A glance at the headlines of Heet’s articles over the last few months reveal his unsurprising profoundly liberal interest in lambasting Donald Trump (“the voice of aggrieved privilege” whose so-called populism is a species of “authoritarian bigotry”), Playboy (“today’s upwardly mobile men are too busy with work to imitate the Playboy lifestyle”), Bernie Sanders (who says he wants revolution but “he’s not much different than Hillary”), and that bulwark of conservatism, the National Review (“when will National Review apologize for cooperating with murderous dictator Augusto Pinochet”—another shred of antiquity). Not that Heer always exploits the distant past for sensational headlines. He also writes: “If the Charleston killer was ‘the last Rhodesian,’ then National Review's conservatives were the first American Rhodesians.” And “Dylann Roof and the intersection of psychology and extremist ideology.” But he always keeps an eye on the past: “The Second Republican Debate Was Just Like Seinfeld’s ‘Festivus’: the Republican Party is still debating decisions made by the Bush presidents and even Ronald Reagan.” Throughout, Heer is articulate and incisive. He also sometimes reveals a talent for couching statements of pedestrian fact in the most melodramatic diction, leering with innuendo and sneering with insidious accusation. He always attacks from a liberal redoubt, making him an asset at the New Republic. He is against conservatives with an eloquent passion (thereby endearing him to me and others of my ilk). And he’s never far from the comics. “Superhero Comics Have a Race Problem,” he headlines a piece about Ta-Nehisi Coates, “the celebrated writer behind Marvel’s new Black Panther series.” And he finds comics even in contemporary politics: “Ted Cruz wasn’t wrong to call Watchmen’s Rorschach a hero.” All of Heer’s output is dense with historical fact and pop culture allusion. He’s an excellent writer of fine muscular prose, and he often has startlingly original insights into the topics he tackles. But he occasionally slips in questionable assertions. In an article about auteurs vs collaborators in producing comics, he refers to Harvey Pekar, whose “career shows both the promise and peril of comics collaboration. As a would-be cartoonist in the 1970s, Pekar had a keen ear for dialogue as well as a stand-up comedian’s ability to reshape everyday experiences into resonant anecdotes.” I’m not sure I’d say Pekar’s autobiographical stories reveal a gift for reshaping personal experience that is akin to that of a stand-up comedian’s. Pekar’s work is distinguished by his ability to turn a slice of his life into an insightful story not necessarily a joke. His stories brim with irony and self-revelatory frustration. Yes, humorous in a self-deprecatory fashion, but likening Pekar’s stories to stand-up comedy goes a step too far. And Heer frequently takes that step. In the same article, Heer turns to Jack Kirby and his work for Marvel, in most of which he was collaborating with Stan Lee. Heer churns out these two paragraphs (in italics), jammed with fact: For Kirby, teamwork wasn’t just an economic necessity but tied to his worldview as a New Deal Democrat. Born in the tenements of New York in 1917, Kirby saw life through the prism of groups: his family, the gangs who ruled the street, the Boys Brotherhood Republic (a youth group that offered an alternative to gang life), the studio he formed with fellow cartoonist Joe Simon in 1940 (which led to the creation of Captain America), the army he was drafted into in 1943. Kirby was anti-individualist and constantly created stories about partnerships and teams: Captain America and Bucky, the Boy Commandos, the Newsboy Legion, Boys’ Ranch, the Challengers of the Unknown, the Fantastic Four, the X-Men, the Avengers, the Howling Commandos, Nick Fury and Shield. Even the very popular romance comics Simon and Kirby created in the late 1940s and 1950s were ultimately about collective experiences, focusing on how families form and fall apart. Kirby’s core belief that human life is a collective endeavor stands in sharp contrast to his ideological opposite among Marvel artists, Steve Ditko. Ditko, even before converting to Ayn Rand’s objectivism in the early 1960s, never cared for groups, but created stories about isolated, often-misunderstood loners, most famously Spider-Man and Dr. Strange. If Kirby was the New Deal liberal focused on groups come to together to overcome historical crises, Ditko was the libertarian who exalted singular, oddball heroes. For Kirby, life was the contention of large historical forces embodied in groups; for Ditko, life is the struggle of the unique person against social forces that try to suppress their individuality. In the dazzle of fact coupled to an original observation (comparing Kirby’s collaborative impulse to Ditko’s auteurial impulse to explain the different kinds of stories they produced) the dubious premise upon which Heer bases his observation slips merrily by. The implication is that Kirby was disposed to collaboration in his creative endeavors because of the collective experiences of his life. But Kirby’s life in groups is scarcely unique. Thousands of Americans experienced life “through the prism” of the same groups—family, youth groups (Boy Scouts and others), and the army. So how did Kirby’s living through these common experiences produce in him a belief in collective endeavor that made him somehow different from everyone else who saw life through the same prism? Or was he so different? If not, Heer’s proposition collapses. And what, then, explains Ditko’s opposite stance? Heer may be absolutely right in his interpretation. But the evidence he musters is questionable: it’s too general to yield the peculiar, individual result he claims for it. In his treatment of Roy Crane and Buz Sawyer, Heer performs another kindred slight of rhetorical hand. Heer visited Syracuse University where Crane’s papers are archived, and in that stash, he found letters from Crane to government officials and vice versa, indicating that during World War II and the ensuing Cold War, Crane had been producing adventure stories in support of government policies. This, Heer concludes, indicates that Crane was part of the government’s propaganda machine. Heer reminds us (in italics) that newspaper comic strips were very popular: They were among the most popular features in newspapers, with adults as likely to read them as children. As Edward Brunner, an English professor at Southern Illinois University, is quoted in Pressing the Fight: Print, Propaganda, and the Cold War, newspapers were “powerful delivery systems for information and entertainment,” no section more so than “the funny pages—the one place visited by almost every reader, young or old, urban or rural, rich or poor, overeducated or uneducated.” A 1950 poll by New York University found that 82.1 percent of college-educated newspaper readers read the comics. Crane’s reach was significant: His audience, at its peak, grew to between 20 million and 30 million people. So if you wanted to get out a message—and the government clearly did, and still does, for that matter—comic strips were as logical a place to do it as any. Contemporary entertainers like Kathryn Bigelow (“Zero Dark Thirty”) and Joel Surnow (“24") have been branded as mouthpieces for the U.S. anti-terror agenda, carrying water for the government’s escapades in the Middle East. It’s hard to deny “Zero Dark Thirty” served up the CIA’s justification for using torture to find Osama bin Laden, and “24” helped normalize the government-friendly idea of torture as an instrument of policy. But—as far as we know!—no one in the U.S. government dictated to Bigelow or Surnow what should be in the work. With Crane, however, we have a clear and well-documented case study in how government officials can micromanage the production of popular culture, a salutary lesson in how propaganda works. As early as 1940 with the debate over whether to enter the European war raging, Crane, Heer says, broke with syndicate policy of neutrality on the issue and created storylines for Captain Easy that “insisted that the European war couldn’t be avoided.” Heer then quotes letters to support his contention. In 1942, Crane wrote Elmer Davis, director of the United States Office of War Information, “pitching his services”: “Those in Washington have almost overlooked one of the niftiest propaganda mediums to be found in the USA— newspaper comic strips .... On my own initiative, I began some propaganda work about two years ago, in an effort to wake people up to the danger confronting us. It was necessary to be pretty subtle as office [i.e., the syndicate] regulations did not permit any mention of war.” Crane suggested the government set up a department and coordinator who could tell cartoonists which themes they should integrate into their narratives. (Boldface emphasis is mine—RCH.) When in 1943 Crane left his earlier creations— Wash Tubbs and Captain Easy —at NEA syndicate to start a new strip, Buz Sawyer, for King Features syndicate, he did it for ownership of the feature and a larger cut of the profits, Heer concedes, “but it was also in alignment with his commitment to pro-war propaganda.” Unlike Captain Easy (who, until the U.S. entered World War II, was a civilian), Buz Sawyer was in uniform, in the Navy, and he was therefore a logical proponent for military action. Although Crane wanted to work with the Navy, it took him a while, Heer says, to win the Navy’s trust enough that its officials would work with him. Heer quotes letters indicating that Crane happily complied with the Navy’s requests and suggestions about storylines that would promote Navy objectives. In return, the Navy supplied information that enabled Crane to give his strip a patina of authenticity. Heer admits (in italics) in the hyperpatriotic atmosphere of World War II, there was nothing unusual about Crane’s work with the Navy. Other cartoonists and entertainers were doing the same thing. One Disney strip showed none other than Mickey Mouse dropping a bomb on Berlin. This was the era when directors such as Frank Capra took time off from feature films to produce propaganda documentaries like the Why We Fight series. But unlike these other contributors, Crane’s propaganda efforts continued after the war. He maintained his close ties to the Navy and later expanded to other branches of government. Politically, Crane became something of a hawkish Cold War liberal, which made him especially eager to work with the State Department. For Heer, “a hawkish Cold War liberal” is roughly today the equivalent of a right-wing war-mongering psychopath of which, to a frothing-at-the-mouth liberal like Heer, there is no mad dog worse than. Heer cites a few examples of Crane following suggestions from the State Department, but he also allows that sometimes Crane didn’t take the suggestions. Still, in Heer’s view, Crane was providing propaganda. His entertainments were “designed to deceive the American people”: The millions of Americans who read Buz Sawyer in 1952 would have gotten a very distorted image of Iran. They would have seen a country where Americans were chiefly helping to avert a famine, where the major threat of disorder came from Soviet spies, where Americans were good-hearted aid officials, where control of the oil supply wasn’t a factor, and where the U.S. government had no conflict with the democratically elected government. In fact, the next year, 1953, the U.S., in its CIA guise, provided support and financial assistance to overthrow the democratically elected government of Premier Mosaddeq. (Heer doesn’t mention the coup.) The propaganda in Buz’s mission to Iran the previous year had certainly been misleading. But it’s a stretch, I believe, to say that Crane was intentionally deceiving the American people, which is the implication of Heer’s assertion. Moreover, Crane, like most Americans at the time, probably believed what his government told him. Heer concedes, however, that through the 1950s, Crane was “no longer getting direct orders from the State Department.” But he was still in “close contact with high Navy officials, who were always eager to use him as a megaphone for their worldview.” Their worldview, according to the evidence that Heer musters, was that Communism was evil and needed to be defeated. During the Cold War, any American who didn’t hold this view of Communists would not be happily tolerated in the public square or the entertainment industry. So how is Crane different? He isn’t. Nor is he subversive in any way, despite Heer’s strenuous insinuations to the contrary. Heer goes to great pains to imply that Crane’s support of State Department/Navy/American objectives is somehow a betrayal of his role as a creative artist if not also some sort of treasonable activity. Heer finishes by reporting that in the early 1960s Crane began getting complaints from newspaper editors that “the propaganda was being laid on too thick.” And that, indeed—judging from Heer’s examples—may be the case. But thickly laid-on pro-American anti-Communist propaganda in those days was all around us: we all played along. Crane, I submit, was no different. Leaping ahead a few years to the late 1960s, Heer notes that in a letter in the Syracuse Crane archives, Crane admitted “several prominent newspapers dropped him because they thought he was too politically strident.” In the reading order of Heer’s article, this fact emerges in the wake of the “complaints” lodged earlier about thick propaganda, compounding the persistence of Crane’s sin. Crane’s politics in those days supported the Vietnam War. And at the same time, the anti-Vietnam War protests were brewing on campuses across the nation—and in the minds of many politicians and the citizenry generally. While Buz was no longer on active duty, he was still often an undercover agent of some sort on America’s behalf. And it was on behalf of America that the Vietnam War was being waged. Milton Caniff’s Steve Canyon experienced similar “complaints” and losses of subscribing newspapers during this period. Caniff was, until late in the Vietnam era, supportive of the conflict in Southeast Asia. But even if he weren’t, he told me, his comic strip’s protagonist was a military man, and Steve Canyon was obliged to do his duty—which, in those times, meant waging war and supporting the military in Vietnam. The strip’s seeming support of the increasingly unpopular war was simply an aspect of Steve’s character: to sustain the authenticity of the character, Caniff had to make him supportive of the military—and the war. Later, Caniff admitted in a sequence in the strip that the anti-war movement was thoroughly understandable, even admirable, the protests as American as the Revolutionary War in the 1770s. But by then, Steve Canyon had lost a lot of newspapers. Crane was as dedicated to infusing his strip with authenticity as Caniff famously was. Caniff had connections in the Air Force that helped him in this regard; Crane, in the Navy. Comic strips with military settings suffered during this time—both Buz Sawyer and Steve Canyon—and Caniff’s earlier masterpiece, Terry and the Pirates, which was finally discontinued a few years later, in 1973, just as the Vietnam War was winding down. Or out. Regardless, the thrust of Heer’s article remains: Crane had sold his creative soul to propagandize for the American government. And Heer lards his article with other snide asides in support of his belief that Crane was not a very reliable creative personality. In tracing Crane’s life, Heer reports that at the University of Texas, Crane “won a reputation as a ne’er-do-well whose low marks were matched only by high gambling debts.” I haven’t heard about the gambling before, but low marks in the academic career of a man who subsequently became famous in a creative enterprise has never been a bad thing before. But it is to Heer, who then refers to Crane as a “wastrel.” And he goes on in this vein: “... his wastrel days reached their apex in his decision to pursue a career in cartooning.” With that, Heer goes off the rails. As a writer about and afficionado of cartooning, why would he so emphatically imply that cartooning is a profession particularly suited to layabouts and wastrels? Because taking that view of the profession re-enforces his opinion that Crane was a disreputable character, just the sort of person you’d expect to be “deceiving the American people” and working with government propaganda machinery. Heer bends history a little, too, to bolster his argument. He says Crane’s Wash Tubbs “was a precursor to the teen humor genre that would later achieve its codified form in the Archie comics.” But Wash Tubbs, which began in 1924, was preceded by a much more popular strip about American adolescent life, Harold Teen, which began in 1919 and shaped cultural attitudes about teenagers through the 1920s. And Heer says Crane’s iconic soldier of fortune, Captain Easy, was a womanizer: “to put it mildly, [Easy] liked the ladies,” Heer says. While it’s true that Easy was forever rescuing toothsome damsels in distress, he never so much as kisses any of them. He undoubtedly liked them, but he’s hardly in the business of pursuing women. Sex is not the subject of Crane’s Captain Easy; adventure is. And rescuing damsels in distress. But for Heer, alleging that Easy was in the soldier of fortune game for sexual adventures makes Buz Sawyer, whose squeaky clean-living is “an unambiguous embodiment of virtue,” the perfect wholesome vehicle to propagandize for the government. In sum, Heer’s article is a hatchet job on Crane. For all the detail Heer conjures up, his purpose is to smear Crane, and many of his details are mustered to that purpose. Heer, too young (his B.A. from Toronoto University is dated 1991) to have experienced much of the Cold War at its height, does not give sufficient credence to a prominent fact about that period: during World War II and the Cold War, patriotism was permitted. Even encouraged. Whatever propagandizing Crane was doing during those years embodied the cultural milieu of the times. Crane started getting pushback from newspaper editors during the Vietnam War period, when the bloom was going off the rose of unquestioning support for government. Like many of his generation, Heer has a tendency to crucify the past on the cross of today’s values. Ever since Vietnam and, subsequently, Watergate, we, as nation, have been reluctant to accept the “government version” of almost anything. Government, while not exactly evil, is certainly an amoral presence with questionable (if not impure) motives. And people who work to advance government programs are suspicious. Hence, Crane would be a suspicious operative were he propagandizing for the government today. But he worked in another era when patriotism and support of the government was expected, even demanded, in all entertainers, Hollywood personalities and cartoonists alike. An unintended irony of Heer’s screed, however, is that he is crucifying Crane for doing something that most writers about cartooning tend to champion. In cultivating government (Navy) sources, Crane was in part seeking information about the service that he could use to give his strip the aura of authenticity that would enhance the realism in the drama of Buz’s adventures. But Crane was doing something even more significant in the annals of syndicated cartooning. As he espoused and spread government propaganda, Crane was exercising his personal opinions in his creation about issues of the day—something all cartoonists aspire to do, something most afficionados of the medium admire in cartoonists, something fans have applauded as comics have increasingly been freed of a traditional restraint that exacted neutrality on social and political issues. In expressing his beliefs about war-making before and during World War II and in sprinkling support for the American side in the Cold War, Crane was offering his opinion on these matters in his strip. Something syndicates generally frowned on. Something that Garry Trudeau has done consistently in Doonesbury, something comics afficionados admire in Trudeau. Trudeau’s was a somewhat different perspective on somewhat different topics, but it was as personal as Crane’s was a generation before. If Heer doesn’t agree with the point of view Crane espoused, so be it. But that doesn’t make Crane some sort of traitor, a collaborator with an untrustworthy government. In fact, he is an early example of creative independence in a mass medium that didn’t often, in those distant days, encourage such individuality. A second unintended irony pervades Heer’s essay: he is as much a propagandist for unfettered liberal views as he alleges Crane was for the State Department’s international schemes. I like Heer’s stuff, and I read it with pleasure. He is an excellent writer and, often, an original thinker, both worthy of admiration. But I have to be wary of the way he slips in biases and opinions that are often not well-grounded in actual fact.

RANCID RAVES TRAVELOGUE A Visit to Abe Martin Lodge I WAS IN INDIANA last month, visiting relatives, but I encountered a charming scrap of cartooning lore while there, thanks to my nephew, who recommended that we dine one evening at the Abe Martin Lodge, a resort atop Kin Hubbard Ridge in Brown County State Park just down the road a piece from Nashville, Indiana, a small town with artist colony aspirations and numerous souvenir shops, tourist traps, and parking problems. Dedicated and named in 1932, Abe Martin Lodge now boasts 84 sleeping rooms (two beds and a bathroom each), meeting and conference rooms, a dining room/restaurant, an indoor water park and, scattered around the immediate vicinity, numerous cabins for rent. The Lodge claims to be “only one of a few resorts in the world named after a cartoon character.” “Only one of a few” is a curious statement, hedged with qualifiers that handily undermine disputation—if any. (Well, there’s Disneyland, but Disney wasn’t a cartoon character; and the defunct Dogpatch U.S.A. in northwest Arkansas, but Dogpatch, although individual enough to be a virtual character in Al Capp’s Li’l Abner, was the locale, not a personage. So unless anyone can think of a resort named after a cartoon character, Abe Martin Lodge stands undisputed—despite the qualifiers.) And who, you ask, was Abe Martin? Glad

you asked. He was the comical concoction of Kin Hubbard, an Indiana cartoonist

and humorist renowned for three decades, 1900-1930. In the rest of this article, however, we focus on Abe Martin as he appears in the resort that bears his name. Our visit begins with a few of Hubbard’s renderings of the character and then wanders off into the Lodge and the Abe Martin exhibits that can be found therein.

Abe Martin, incidentally, is still being published—in reprint, I suspect, in the newspaper that Hubbard’s father published in Ohio, the Bellafontaine Examiner. The publisher nowadays is Kin Hubbard’s grandson.

MY TRAVEL PLANS FOR 2015 Just Over the Internet Transom I have been in many places, but I've never been in Cahoots. Apparently, you can't go alone. You have to be in Cahoots with someone. I've also never been in Cognito. I hear no one recognizes you there. I have, however, been in Sane. They don't have an airport; you have to be driven there. I have made several trips there, thanks to my friends, family and work. I would like to go to Conclusions, but you have to jump, and I'm not too much on physical activity anymore. I have also been in Doubt. That is a sad place to go, and I try not to visit there too often. I've been in Flexible, but only when it was very important to stand firm. Sometimes I'm in Capable, and I go there more often as I'm getting older. One of my favorite places to be is in Suspense! It really gets the adrenaline flowing and pumps up the old heart! At my age I need all the stimuli I can get! I may have been in Continent, but I don't remember what country I was in. It's an age thing. They tell me it is very wet and damp there.

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics An admirable first issue must, above all else, contain such matter as will compel a reader to buy the second issue. At the same time, while provoking curiosity through mysteriousness, a good first issue must avoid being so mysterious as to be cryptic or incomprehensible. And, thirdly, it should introduce the title’s principals, preferably in a way that makes us care about them. Fourth, a first issue should include a complete “episode”—that is, something should happen, a crisis of some kind, which is resolved by the end of the issue, without, at the same time, detracting from the cliffhanger aspect of the effort that will compel us to buy the next issue.

THE STORY in the first issue of Twilight Children is almost a typical Gilbert Hernandez enterprise: it takes place in a small seaside Latin American village, some of the protagonists are children, an extra-marital affair is in progress, and much of the narrative transpires pictorially without any verbiage. But two things seem to me a-typical: first, the book is drawn by Darwyn Cooke, not Hernandez; and a spooky sf element pervades. Cooke, who usually writes and draws his comics, got involved in the project because, according to David Betancourt at the Washington Post, he just wanted to draw, not write. When DC Vertigo’s Shelly Bond asked him what he’d like to do, Cooke, who likes to resist accepting projects, said he wanted to draw something that Hernandez would write. Said Cooke: “I thought: that’s the end of that. Gilbert will never work with me, and now I can say, ‘Well, I would have but ...’” But Hernandez was all up for the collaboration. And so it began. The first issue introduces all the cast, creates several mysteries, and ends, appropriately, on a stunningly suspenseful note. Anton is a burly fisherman who is having an affair with Tito, who is married to Nikolas, who helps run Tito’s woman’s wear shop. Bundo is the town drunk who lives alone in a shack on the beach. Years before, he fell asleep while smoking and his fallen cigarette accidentally set his home on fire; his wife and family died in the conflagration. He likes to watch three kids—Milo, Grover and Jael—play on the beach, and he warns them to stay out of a cave in the rocks. Hernandez alternates picking up one or another of three narrative strands that thread through this issue. We watch as Anton and Tito proceed in their affair, Nikolas being cheerfully oblivious and even inviting Anton to dinner some night. But one of their assignations concludes when a mysterious gigantic white ball materializes in the bedroom, connecting the affair thread to the white ball thread. The same ball appeared earlier that day on the beach, amazing the three kids, who go running for Bundo. The ball, or others like it, has appeared before so, while it amazes the local population, it is not an unfamiliar sight. The local sheriff wants Bundo to watch the ball all through the night to see what it does. But Bundo falls asleep in the enveloping darkness, and when he awakens, the ball has disappeared—as it usually does—without anyone seeing how that happens. Bundo, ashamed at his failure, runs off into the woods, leaving us to wonder how this strand will end and why it is present at all. Local authorities invite a big city scientist, Felix, to come and investigate the white ball, but by the time he arrives, the ball has disappeared. He stays, however, and the locals view him with suspicion. The kids, meanwhile, venture into the cave in the rocks on the beach and encounter the white ball there. When one youngster reaches out to touch it, a huge wind arises, blowing its way through the town. And when the kids emerge from the cave, they have blank eyeballs. They’re blind. Bundo returns to the beach in the last pages of this issue. His beach house was wrecked in the big wind, and Bundo sees the episode as a warning. And as he contemplates the wreck of his house, we see in the distance a statuesque naked woman with billowing white hair blowing in the breeze. It is the same figure that appears on the opening page of this issue. Hernandez has rounded the first installment of his tale by echoing a mysterious imagery. Several completed episodes occur. One reveals the complexity of the love triangle with Anton, Tito and Nikolas. The white ball arrives and leaves—twice—baffling everyone who encounters it. Local fishermen try to capture the ball in a net but fail. And we are left to wonder if Nikolas will discover his wife’s infidelity (and if she will tolerate Anton much longer), if the kids’ blindness is permanent or not, if Bundo is right about the incident being a warning, what the white ball is, and who (or what) the naked white-haired lady is and what her connection to the white ball might be. If any. Plenty of mysteries, but strong characterizations let us know the protagonists and care about them. And the completed episodes, by tying up portions of plot strands, both create and satisfy our desire to know more. Our interest sustained, we want to know the answers to the questions the story has, thus far, posed. Cooke’s drawing is, as always, superb. His work is in many respects similar to Hernandez’s—simple, boldly linear. But Cooke’s hand is surer than Hernandez’s, and his eye for panel composition is keener, and the book is a handsomer product as a result.

The collaboration seems to work brilliantly. Hernandez told Betancourt that working with Cooke is “like having a creative partner who doesn’t need much verbal guidance. Because Cooke is such a brilliant visual storyteller himself, Hernandez doesn’t have to get overly descriptive in conveying what he wants for the narrative.” Betancourt quotes Hernandez: “He basically doesn’t need me, but since I was there, and we’re working together, I put down a story that I thought would work on his strengths if I gave him just enough information and description and then put in my usual characterization that I have in all my stories.” Cooke said he is enjoying the “openness” of Hernandez’s scripts. He said it’s “a real treat to work with a cartoonist writing the script. It’s a very different experience.” He elaborated: “I just made sure I was honoring what Gilbert had written and wherever there was room, I tried to make sure I was adding something that might put another layer into it for the reader, or might create a juxtaposition that wasn’t expected.” Hernandez remembered a particular moment when he forgot to include descriptions for a splash page. “He thought about reaching out to Cooke,” Betancourt reported, “but decided against it, convinced that Cooke would come up with something just as good for the story.” Said Hernandez: “I just stopped myself and said, ‘Let’s see if he can come up with something.’ And he did.” The collaboration offered Cooke an opportunity that he’s been hoping to create for some time, he told Betancourt. “But there was always something that kept me in the game doing the type of books I do. This is like a deliberate move on my part to embark on another path. “Working on this project,” he continued, “is starting to unlock a few things in my mind, in terms of storytelling and maybe where I want to go. It’s helping me open doors in my head that have been more-or-less closed. When you’re working on a mainstream book, there are certain criteria, there are certain things you have to do and you have to hit. And this has been really liberating in that those rules don’t apply here.”

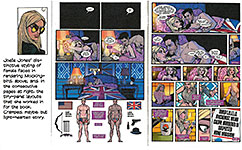

MOCKINGBIRD No.1 isn’t really a first issue. We know the character: an agent of S.H.I.E.L.D., Barbara “Bobbi” Morse has been around for a while, both before and after she was brought back from the dead by Fury. Besides, this is a one-shot “50th anniversary” issue. So the usual criteria for a first issue don’t apply. The issue opens with her awakening in bed with her current lover, Lance Hunter, but she mutters the name of a former lover, “Clint”—as in Clint Barton, Hawkeye. Lance doesn’t seem to mind, though. Barbara arises, gets dressed, reads in the morning paper that her mentor, Wilma Calvin, has been murdered, and goes to the morgue where Wilma’s corpse is residing. Joined by Wilma’s son Percy, Barbara conducts an autopsy and decides Percy killed his own mother. Percy, however, has drugged Barbara by lining her plastic gloves with neurotoxin, which knocks her out. When she recovers, she’s bound to an examining table, but she breaks free and takes Percy out. At the end of the issue, she’s back in bed with Lance, and as she turns out the light, she says, “Goodnight, Clint.” And Lance says: “You did that on purpose, right?” A nicely circular storyline, but I don’t know why writer Chelsea Cain wants Barbara to object to Lance’s “cuddling her.” Probably because cuddling is intimate, and Barbara is trying not to be too intimate with Lance. But that’s just a guess.

The book is drawn by Joelle Jones in her usual hard-edged bold linear manner. But Cain doesn’t take full advantage of Jones’ talent in rendering action sequences. As you can see in the accompanying illustrations, the narrative on many of the book’s pages is carried by multiple tiny panels that permit a focus on only parts of the person depicted. This kind of pacing is skillfully managed, creating and sustaining mood for dramatic emphasis, and Cain/Joelle make it work here. But they also contrive a huge two-page illustration of Barbara performing the autopsy under a massive ceiling light to no dramatic purpose. A conspicuous waste of space. Ditto the single page given to showing Percy hovering over Barbara’s body as she wakes up, chained to the examining table. The space would be better used in showing Barbara taking Percy down after she’s broken free of the shackles. Given the over-all success of the book, this quibble is perhaps excessive. In any event, it’s nice to see Jones at work again in a pleasingly complex tale.

HERE’S A BOOK with a genuinely descriptive title— Paper Girls. In No.1, we meet Erin having a nightmare about the Devil just before she awakens and arises at 4:30am to load up her bicycle with newspapers to deliver on her daily paper route. In one of the issue’s two complete episodes, she runs into three Hallowe’en costumed teenagers who try to bully her out of a newspaper—but she’s saved with the arrival of three other paper girls, MacKenzie Coyle and Tiffany and KJ, who, by virtue of their number and Mac’s chutzpah, chase off the trio of bad guys. The three girls, led by the cigarette-smoking MacKenzie, deliver papers as a group for mutual protection from roaming tough boys who infect the neighborhood. They invite Erin, who the episode reveals as a smart fearless twelve-year-old, to join them, and she does, splitting the trio into two duos. Erin goes with Mac. The two encounter a hostile cop who knows Mac by name—suggesting that Mac walks close to the line, legally? And then when Tiffany and KJ are attacked by “three guys in ghost costumes” who steal Tiffany’s CB, the group reconvenes to recover the stolen property. Thinking the “ghosts” might be hiding out in one of the houses under construction, the girls sneak into one of the houses and find what appears to be some sort of space ship. The thing starts glowing in the dark, and the girls rush out of the house—finding three “ghostly” figures outside, each one wrapped head-to-toe in a blanket or cloak. They are speaking a strange language, and when Mac attacks one of them and tears off the hood, a fearsome visage is revealed. The ghosts run off, leaving behind a kind of compact with an Apple symbol on it. The issue ends with Erin holding up the compact and wondering what it is. So do we. The opening nightmare sequence tells us that this book is about something more than delivering newspapers; and the encounter with the other worldly ghosts confirms our suspicion. Brian K. Vaughn is the writer of this tidy tale, and he paces it meticulously: after Erin awakens, the visuals focus, panel by panel, on the individual steps she takes to get her bag of newspapers ready to load up and deliver. Other sequences are developed with the same attention to detail, resulting in a 38-page introductory story.

As a first issue, Paper Girls does all that an inaugural outing should, provoking both interest and suspense. I’ll be back.

THE COMIC BOOK Beyond Belief is an ink-and-paper version of a podcast by Ben Acker and Ben Blacker (Acker and Blacker—can such a rhyme be real people?), who, for 10 years ending last April, wrote and produced the shows, taking them on stage with their actor friends standing at microphones reading the scripts in the manner of old-time radio. Acker and Blacker started translating “The Thrilling Adventure Hour” shows into comic book form with Sparks Nevada, Marshal on Mars, which we reviewed here in Opus 343. Beyond Belief No.1 introduces us to Frank and Sadie Doyle, a married couple whose flip patter and fondness for martinis reincarnate the Nick and Nora Charles “Thin Man” movie creations of William Powell and Myrna Loy. The Doyles are mediums, and in this debut performance, they rid a friend’s house of its various haunts. A second story records the initial meeting of Frank and Sadie. And again, Frank deploys a sigil to banish the spooks. Each of the two stories is a single completed episode—in short, a stand-alone story—so the book does not end a cliffhanger designed to bring us back for future issues. If anything will bring us back, it’s the comedy of the conversation. Part of the pleasure of this book arises from the Doyles’ lively banter; the rest of the enjoyment comes from Phil Hester’s clean boldly-lined drawings, inked by Eric Gapstur and, sometimes, Ande Parks. Hester’s panel compositions and page layouts often deviate from the normal grid, enhancing the tales with visual novelty. The two dilemmas faced and surmounted by the heroic couple are very much alike in this book, which leads me to suspect that subsequent outings will be more of the same—different enough to engage us but similar enough to be familiar. The book otherwise incorporates the trappings of a vintage radio show, blaring “The Thrilling Adventure Hour” on the opening pages and adding: “Join us in tonight’s dark episode, ‘The Donna Party’”—Donna being the name of the friend whose house the Doyles’ purge of ghosts. (“The Donna Party” also invokes memories of a famous 19th century incident of cannibalism, the Donner Party, the members of which, stranded in the wintery Sierra mountains of California, ate each other rather than starve to death. That’ll give you an idea of Acker and Blacker’s senses of humor.)