|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 344 (September 22, 2015). Another hare-raising adventure which started out as an annual “picture” posting with coverage (so to speak) of the pin-up covers of superheroine comics but finished with a report on the heavily guarded editoonists annual convention and an examination of New Yorker cartoonists, beginning with the inert work of BEK, plus reviews Graphic Canon Vol.3, Loisel’s Peter Pan, and an assortment of funnybooks (Welcome Back No.1, We Are Robin, Romita’s Superman, 1872, IDW’s Sherlock Holmes), and news about Charlie Hebdo’s latest, Farghadani’s indecency, Warren Ellis’ forthcoming James Bond, “The O’Reilly Factoid,” and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, the Bible and its reputed prohibitions, a look at the month’s editoons and an obit for Brad “Marmaduke” Anderson, and more—all fastidiously illustrated and illuminated. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department—:

NOUS R US Charlie Hebdo Again (Cartoonists’ Reactions) Farghadani Faces Indeceny Charge Ohman’s Farewell to AAEC Comic Book People 2 Out Now (A Review of Comic-Con and the Industry’s History)

ODDS & ADDENDA Staples Only through Archie No.3 James Bond 007 in November Zunar Gets Award Dr. Seuss Racist Brodner on Trump Walt Disney Biog on PBS Missing Dennis Statue Found. Or not? Archie on Radio Caricatured

THE O’REILLY FACTOID (I Love This Guy: He’s Such a Fiction)

EDITOONISTS GUARDED CONVENTION Some Excellent Cartoons On Charlie Hebdo

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Welcome Back No.1 We Are Robin Romita’s Superman Marvel’s 1872 IDW’s Sherlock Holmes Mignola’s Decorative Page in Hellboy

EDITOONERY The Month’s Events in Editorial Cartoons David Fitzsimmons Extolled

NEW YORKER CARTOONS: PART ONE The Inert Cartoons of BEK BEK Graphic Novel: Edmund and Rosemary Go to Hell

RANCID RAVES GALLERY A Plethora of Cover Pictures of Pin-Uppy Heroines

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST Lawrence Ferlinghetti Is 96: Some Poetic Excerpts Kenneth Rexroth

BOOK MARQUE Short Reviews of—: The Graphic Canon: Volume 3 Regis Loisel’s Peter Pan Kremos, Volumes 1 and 2 Previewed Scholarly Titles at McFarland

ABOUT THE BIBLE AND ITS REPUTED PROHIBITIONS

PASSIN’ THROUGH Brad Anderson

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

CHARLIE HEBDO is back in hot water—for the usual reasons: the French satirical magazine published a couple scathingly sarcastic cartoons on a sensitive subject which made the magazine look uncaring and unsympathetic about the current migration crisis engulfing Europe. One cartoon, echoing the image of a 3-year-old drowned Syrian refugee, Aylan Kurdi, locates near the body of the child a billboard advertising two kid’s menu meals for the price of one with the caption “So close to making it.” In a second cartoon, captioned, according to time.com, “Proof that Europe is Christian,” a Jesus-like character is walking on water while another is sinking head first with the former saying “Christians walk on water” and the latter saying “Muslim children sink.” “Many commentators, both in the press and on social media, expressed outrage at the magazine, with some even threatening legal action. Others have defended Charlie Hebdo, saying the cartoons were clearly intended to indict European governments for failing to address the migrant crisis.” I go with the latter. The cartoons revolve around insufficiently responsive European governments faced with a humanitarian crisis. In both cartoons, an “outside world” appears uncaring, even oblivious, to the ongoing tragedy.

AT THE WASHINGTON POST’S ComicRiffs, Michael Cavna spoke to several American editoonists about their reactions to the use of the dead boy in a cartoon. Jen Sorensen, winner of the Herblock Prize who had just returned from Turkey, said: “Strangely enough, I was just on the beach where Aylan drowned. I spent time there when I visited Turkey in June as a juror for the Aydin Doğan International Cartoon Competition, so I find that photo, and other images of refugees in Bodrum, particularly chilling. While I did find other Charlie Hebdo cartoons to contain elements of bigotry, these seem to be mocking the callousness of Europe rather than the boy himself. I believe the intention is to show sympathy for the plight of the refugees.” While reading the work as sympathetic, Sorensen notes that she would not invoke Aylan the way Charlie did. “I can see how some people might view the legs poking up out of the water [in the Jesus cartoon] as slightly too goofy a comedic trope for a tragic situation. While I have not drawn Aylan myself, if I did, I would want to do it thoughtfully, as part of a poignant cartoon. It’s not an image that lends itself to jauntiness.” Liza Donnelly, too, has spent recent days overseas. Said Cavna: “The political cartoonist/editor and New Yorker gag cartoonist has been at the fifth International Meeting of Press Cartoonists in Caen, France, where security was heightened considerably compared with previous meetings, in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attack. And while Donnelly believes strongly in press freedoms, she also believes in drawing a personal line when sitting to draw editorial lines.” “The photo of Aylan Kurdi is extremely powerful,” Donnelly told Cavna. “I believe there is no reason for a cartoonist to ‘use’ it — we can find other ways to express concern and outrage at the Syrian crisis. And to use the imagery of Aylan in that photo to create a joke — to be honest, I find that very disturbing. But, that said,” she continued, “if people want to draw cartoons that make fun of a tragically dead child, they should of course have the freedom to do so.” Mike Luckovich, the Pulitzer-winning political cartoonist for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, thought about whether to use the refugee boy’s body as a symbol — and reasoned that it is a fitting image to invoke, even if he ultimately chose not to. “I didn’t use the image. I had a rough sketch that used Aylan Kurdi to show the world’s indifference, but I ended up not drawing it,” Luckovich said. “It wasn’t because of the image of the drowned toddler, though. I just didn’t think it was a great cartoon. I think as an editorial cartoonist, using an image that’s become a worldwide symbol, even if sensitive, is completely appropriate.” Still, he believes the French weekly is wide open for another angle of criticism. “I would not have done either of those Charlie Hebdo cartoons,” he said. “First, they’re both lousy ideas. And secondly, by using the powerful image of that dead little kid, they overwhelm whatever point they were trying to make in both cartoons.” He continued: “I know Charlie Hebdo is satirical, but there is good satire and bad satire. I think both of these cartoons fall into the latter category, especially the one with the billboard of the Ronald McDonald-like character.” Jack Ohman, the editorial cartoonist at the Sacramento Bee, underscores the necessary context when drawing deceased people, especially children. “I have not employed that particular image” of Aylan, says Ohman. “I couldn’t rule it out, because there are ways to do this and make a legitimate point. That’s what we do. I have done cartoons that have used a dead person. For example, I drew a cartoon about Robert McNamara a long time ago using the Kent State shooting victim. I think, in context, I could see where some of these cartoons are effective. … Use of children is a sensitive point. It’s important to take each cartoon in context. I think some of the criticism of these cartoons were clearly, deliberately misconstrued.” Nikahang Kowsar, a Washington-based political cartoonist and refugee from persecution in his native Iran, has not employed Aylan’s image, but he appreciates why some of his colleagues have. “I have not yet used Aylan in a cartoon — it was really heartbreaking and I couldn’t do it,” said Kowsar, who was once jailed in Iran for his cartoons critical of the nation’s religious leaders. “But I certainly love many cartoons that demonstrated the depth of the Syrian refugee crisis and the human catastrophe by showing Aylan as a victim of the devastating war, and a victim of a choice that others have made.” Then Kowsar illustrates what he might have rendered. “I would have drawn president Obama preaching to Aylan’s dead body, telling him why the U.S. chose to intervene in Libya but do nothing in Syria. And Aylan’s spirit would have responded, ‘I know, you needed the Iran deal…that’s why.’ ” “Those words are powerful,” Cavna finished. “But would their context have been misinterpreted, or roundly criticized, had Kowsar actually drawn Aylan’s small, lifeless body?”

PROLONGING THE AFFRONT TO HUMAN DIGNITY By Matilda Battersby, independent.co.uk; September 9, 2015 RCH in Italics In a time fraught with religious zealotry, we cannot be too surprised that Atena Farghadani, 29, currently in an Iranian jail appealing her sentence of 12 years for criticizing the government with a cartoon, now faces further charges of “indecency” for allegedly shaking hands with her male lawyer. Amnesty International reports that charges of an “illegitimate sexual relationship short of adultery” have been brought against Farghadani and her lawyer Mohammad Moghimi amid allegations he visited her in jail and shook her hand— which is illegal in Iran. Farghadani was sentenced to 12 years and nine months in prison earlier this year when, after the publication of her cartoon protesting plans by the Iranian government to outlaw voluntary sterilization and to restrict access to contraception, she was found guilty by a Tehran court of “colluding against national security,” “spreading propaganda against the system” and “insulting members of the parliament” through her cartoon, which depicted Iranian government officials as monkeys and goats. After getting no satisfaction with a letter of complaint to the government, Farghadani recorded a video in which she explained what happened to her in Evin prison, with details including being strip-searched over a minor offence, beaten and verbally abused by guards. Too much protest. She was re-arrested in January 2015 and sentenced in June by judge Abolghassem Salavati who is notorious for leading numerous controversial trials, many of which resulted in executions. The artist now faces a fresh trial on indecency charges and Amnesty International predicts that her sentence will be extended. Farghadani is believed to be serving her sentence in Gharchak jail and is reported to have gone on hunger strike.

JACK OHMAN’S FAREWELL TO AAEC Few retiring AAEC presidents have published farewell remarks. Although many might have felt the impulse, they resisted it. Jack Ohman did not. His term, however—December last year until December this year—embraced some unusual circumstances, which he wrote about in his farewell “speech” at his newspaper’s website, sacbee.com; excerpts—: After being elected president of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists last year, I faced the usual task: organize the convention and don’t screw up. [See report on the AAEC Convention on the other side of the $ubscribers Wall.] After all, my predecessors had managed to keep the group afloat, and I had no reason to think it wouldn’t be a typical year. Then in January, cartoonists at the offices of the Charlie Hebdo magazine in Paris were slaughtered. Suddenly, I was faced with a completely new world. Instead of a nice, quiet convention in nice, quiet Columbus, Ohio, I had lots of concerns – like would any of us be murdered en masse. After the shootings at the ridiculous Pam Geller-instigated Muhammad cartoon show in Garland, Texas, I was even more concerned. So instead of a hotel lobby and convention site filled with happy editorial cartoonists (not an oxymoron), there were lobbies filled with bomb squads, bomb-sniffing dogs, a SWAT team on a nearby roof, sheriff’s deputies, and uniformed and plain-clothed Columbus police officers. I was the only president of a cartoonist group who required Secret Service protection, although the Secret Service was probably the only agency not represented. The Department of Homeland Security, formerly a cartoon subject, became my wingman as I asked for occasional updates. They hadn’t picked up any terrorist chatter, so that was a relief. ... Ohman went on to record the slow decline in the number of full-time staff editoonists, continuing—: At one time, California had at least 10 full-time staff cartoonists: three in San Francisco, three in Los Angeles, one in Long Beach, one in Sacramento, one in San Diego, and several more scattered around at smaller papers. Now it’s me, Steve Breen in San Diego and David Horsey in Los Angeles. ... In Texas, there is one: Nick Anderson at the Houston Chronicle. One. In all of Texas. Political cartooning is a precious thing in our society. It stretches the tensile strength of the First Amendment, affects public policy and gives us all a break from depressing stuff, like Donald Trump’s pink fiberglass coiffure or Hillary Clinton’s need to plan her spontaneity. As for me, I leave the presidency in November, and I am happy to go back to planning my presidential library. You’re invited to the grand opening. Just step through the metal detector and show a photo I.D.

Reflecting on his own career, Ohman said during an interview with Michael Cavna: It’s an excellent time to be me, except for the blood-pressure medication and the constant chore of keeping my hair at bay. I really feel like I am doing the best work of my career, and I enjoy each day. I started winning awards when I stopped thinking about winning awards. I started liking my work when I listened to my own voice, and not feeling so constrained by the old model. When you like your work, others will probably like it too.

ESTRADA’S SECOND BOOK OF COMIC BOOK PEOPLE IS NOW Comic Book People 2, the second of Jackie Estrada’s photographic memoir of the Sandy Eggo Comic-Con, is now out in comic book shops, Amazon, and at exhibitapress.com (156 9x12-inch pages, b/w with color section; 2015 Exhibit A Press hardcover, $34.95). The first volume (which I reviewed in Opus 341) is filled with annotated photos taken at the Comic-Con in the 1970s and 1980s; this volume concentrates on the 1990s. I reviewed the second volume in Opus 342 if you want to revisit that. In the meantime, though, Estrada was interviewed about the book by Chris Arrant, newsarama.com editor, and I’m culling from it a few of Estarda’s remarks; to wit—: “The first volume was very well received, which meant that I had to do the second one! The 1990s volume still runs the spectrum of folks in the industry (including editors, publishers, retailers along with creators), but there are a lot more photos of indy/alt cartoonists and self-publishers. I also cover such trends as the foundings of Image, Milestone, the CBLDF, and Friends of Lulu. Most of the people in this book are still around and working today.” Asked to summarize her impression of the “tone” of the Comic-Con in the 1990s and any changes apparent, Estrada said: “I think we saw more different types of conventions, more diversity of comics being produced, and a higher level of professionalism. You had the big shows like San Diego and Chicago, then lots of regional shows (like WonderCon and Heroes Con) that each developed their own character, and the alt/indy shows like APE and SPX. On top of that you had trade shows: Capital City, Diamond, ProCon. Many more companies were coming on the scene, and some of them were making big splashes with elaborate booths (Tundra and Tekno come to mind). In 1990 San Diego’s attendance was about 13,000; by 1999 it was something like 45,000. So the tent was definitely getting bigger. [For the last few years, Sandy Eggo has tallied over 130,000.—RCH] “The early and mid-1990s were boom years because of the founding of Image, the expanded direct market, the speculator market, and the burgeoning self-publishing movement. So you saw lots of new faces come into the business and on the con floor, not only creative people who otherwise wouldn’t have ventured into the medium but lots of businesspeople who thought they could cash in on all the big bucks to be made in comics. ... “No longer was press coverage devoted to ‘look how much that comic book of yours would be worth today if you’re mom hadn’t thrown it out!’ Now tv reporters would set up in front of that cool-looking display and do interviews. Other companies had to follow suit if they were to compete. And some of them competed by bringing in celebrities to do appearances at their booths, from William Shatner and Mark Hamill to Mickey Spillane and Mr. T. Meanwhile, Comic-Con created a Small Press Area and the Independent Publisher’s Pavilion (where Batton and I have exhibited for the last 20 years) in the mid-1990s to reflect that growing aspect of the industry. Also by the mid-1990s, Comic-Con had expanded from using just one end of the Convention Center to using the whole facility. “And by the end of the 1990s we were seeing the rise in the popularity of manga and anime, which correlated with higher female attendance at shows, especially San Diego. I think that’s when I first heard the word ‘cosplay,’ in relation to the Sailor Moon gangs. And as many people are fond of pointing out, we started to see more Hollywood involvement, whether it was a Ghostbusters display or Francis Ford Coppola talking about his version of Dracula. I really think we started seeing the cross-pollination between comics and the tv/film/animation industries take off in that decade. Perhaps one of the big hints of things to come was a panel and signing that Joss Whedon did in 1998 with most of the cast of Buffy the Vampire Slayer—fans went into a Beatles-like frenzy!” Asked about her favorite photos in the books, Estrada said: “The most heart-warming photos to me are the ones of my very dear friends who are no longer with us—Dave Stevens, Al Williamson, B. Kliban, Barb Rausch, to name a few. In the 1990s book, there is a 1991 photo of Sharon Sakai carrying then-baby Hannah on her back that gets me every time I look at it. I’m also fond of a photo of Chris Ware with the late Kim Thompson from 1998; Kim has a protective hand on Chris’s shoulder.” Estrada’s two books of photographs with explanatory captions are much better than I’d hoped when I first heard of them. They’re not just photo albums. They are that, and the photos are very good; but they’re much more than that. They’re history on the hoof. Don’t pass ’em by.

ODDS & ADDENDA Fiona Staples signed up for only the first three issues of the new Archie, producing absolutely exquisite work (especially the 2-page sequence in No.2 with Betty getting ready for her birthday party); Annie Wu is being billed as “guest artist” in No.4, and my bet is that she’s the new permanent artist (if they can’t convince Staples to continue). ■ Dynamite Entertainment’s first issue of James Bond 007 by Warren Ellis with Jason Masters drawing will hit the newsstands November 4, a day ahead of the new Bond movie. Entitled “VARGR,” the story has Bond returning to London after a mission of vengeance in Helsinki to assume the workload of a fallen 00 Section agent, but something evil is moving through the back streets of the city and sinister plans are being laid for Bond in Berlin. Ellis says his Bond is a much darker character, and the story is devoid of the kind of gadgets and gimmicks that the movies trade in. For Ellis, the definitive Bond is found in the mid- to late-period of Ian Fleming’s novels. “Those novels,” explains Cliff Biggers in Comic Shop News No.1474, “portray a more broken, disturbed character who seemed conflicted by the world in which he operated.” And “that,” said Ellis, “is pretty much where I’m going. That is by far the most interesting Bond, for me —the man whose job is killing him.” ■

The Malaysian cartoonist Zulkiflee Anwar Ulhaque, known as Zunar, will

receive one of this year’s International Press Freedom Awards from the

Committee to Protect Journalists, which recognizes the cartoonist for raising a

moral and unsilenced voice through his cartoons, reported Michael Cavna at

ComicRiffs. Zunar has been charged with sedition and, if convicted, could face

43 years in prison. (See Opus 343.) Zunar told Cavna that when a cartoonist

faces a moral crisis, “you need to stand and fight. You need to carry the

people’s voice through your cartoon.” Here are a couple of Zunar’s cartoons. ■

A California auction house tried to sell an early drawing by Dr. Seuss. But the cartoon, a 1929 contribution to the humor magazine Judge, failed

to attract bidders because the last of the scenarios depicted was blatantly

racist. ■ Steve Brodner, an award-winning satirical illustrator and commentator, is currently at work on a book about U.S. presidents, which inspired him, perhaps, to say (at washingonpost.com) this about this year’s Leading GOP Contender: “He may or may not seize the Republican presidential nomination next year, but Donald Trump is already making metaphors great again. Commentators can’t seem to help describing the billionaire with imagery almost as colorful as he is. While one candidate might be called divisive, Trump is a rattlesnake. And where another contender is aggressive, The Donald is Godzilla. Will Trump’s campaign keep soaring, like a personalized Boeing? Or will it eventually fall flat, like a pompadour on a humid day?” ■ PBS’s 4-hour American Experience “Walt Disney” was reasonably successful in portraying Disney as a driven, highly motivated innovating personality with few people skills and little compassion. He scored more game-changing successes than just about anyone. But the writers/producers of the show neglected certain aspects of history. Ub Iwerks, a Disney animator since the two worked together in Kansas City, invented the famous multi-plane camera, which the show brags about without mentioning Irwerks’ role. And a long segment on the astonishing success of Disney’s tv series “Davy Crockett” neglects to mention the name of the personable actor who created the role, Fess Parker. ■

The Missing Dennis has been found and is now on its way back to Monterey.

That’s the headline. The story is that a statue of Dennis the Menace was

commissioned by Dennis’ creator, Hank Ketcham, in 1988 and went on

display in Monterey, California at the Dennis the Menace Playground, designed

by Ketcham. Then during the night of October 25, 2003, the bronze statue (3½

feet high, 200 pounds) went missing. It remained missing until August 22 this

year when it was found in a scrap metal yard in Orlando, Florida. Dennis was

going to be melted with the rest of the scrap but the owner’s daughter noticed

it and recognized Dennis. Then she searched the Web and found stories about the

missing Monterey Dennis. Or was the one in the scrap heap the missing one?

Three more bronze Dennises were cast from the same mold made by Wah Ming Chang,

who directed in his will that the mold be destroyed after his death in 2003.

The other three are at the Community Hospital of the Monterey Peninsula, the

Pebble Beach backyard of Ketcham, and the Arnold Palmer Hospital for Children

in Orlando. But the latter is also missing: it disappeared in the late 1990s

during a Disney renovation of the playground where it stood. So the one found

in the scrap metal yard could be the Arnold Palmer Dennis, not the Monterey

Dennis. The Monterey Playground at present has another Dennis statue, cast from

a mold made from one of the other sculptures. So there are five Dennis statues

altogether, and one of them is still missing. ■ While we were still glowing with missing embers, a bunch of Denver comics fans discovered an antique rendering of Archie, Betty, Veronica and Jughead in which the characters look only vaguely like the famed Riverside personnel. The artwork, appearing below the photo of the Dennis statue above, is by Sam Berman, a noted caricaturist in the 1940s and 1950s, who prepared 56 caricatures of radio actors and notable personalities for the 1947 NBC Parade of Stars. The Archie portraits were promoting “The Adventures of Archie Andrews,” and the pictures look like the actors in the program not the characters in the comic book.

THE O’REILLY FACTOID Masochist that I am, I’ve taken lately to watching Bill O’Reilly’s sitcom for conservatives on Faux News, “The O’Reilly Factoid.” The show is self-proclaimed as the “highest rated cable news show in the country.” The operative word is “cable.” Broadcast news programs are seen by many more people: NBC, 8,254,000; ABC, 7,706,000; CBS, 6,529,000 (week ending August 31). Fox News gets a little over a million, and while O’Reilly’s 3,159,000 (week ending August 30) is the highest rated cable news program, he’s still a lightyear or so behind broadcast news, even the lagging CBS News. O’Reilly always introduces his “show” by warning viewers that they’re about to enter the “no spin zone.” Sure. His “news” show does more spinning than a kid’s top. One night recently, he was interviewing (talking with) a like-minded prophet, and he posed a question: What if Obama is lying about the Iran deal? Maybe it was another topic, not the Iran deal; but the point is that he prefaced the interview with “what if Obama is lying?” This is a particularly insidious device: O’Reilly can claim that he didn’t accuse Obama of lying (therefore he’s not guilty of spinning), but the ensuing conversation proceeded as if he had accused Obama of lying—and, in fact, that Obama had, indeed, lied. Spin? No, no—not O’Reilly. After the Republicon Debacle on September 16, O’Reilly called upon a fact-checker from the Washington Post to help him check facts for Carly Fiorina and The Trumpet, both of whom had been tagged as lying or misrepresenting the truth during the verbal fisticuffs. Attacking Planned Parenthood, Fiorina told a gut-churning story about seeing a taped report showing an infant— heart still beating, legs kicking— having its brain extracted while still alive. Turns out the pictures of this infant were supplied to the undercover video crew who spliced them into the tape of their field interview. The sequence was not of anything at Planned Parenthood. It was a put-up job. So was Fiorina lying? No, she wasn’t, saith O’Reilly. She couldn’t have known that the videotape she was looking at was a cobbled-up affair. So she wasn’t lying. (She apparently doesn’t have campaign advisors who might’ve warned her off this particular anecdote.) When it came to The Trumpet, though, O’Reilly had to work harder to get him off. On stage during the debate, in front of God and everyone, Jeb Bush said only one person had ever attempted to buy him off while he was governor of Florida—and that was The Donald, he said, pointing to him. Trump wanted Bush to help legalize casinos in Florida and he hosted a fundraiser for Bush and made a donation of $50,000 to the Florida Republicon Party. The Trump immediately called that accusation false. Never happened. The fact-checker I checked said that it was true that Trump wanted to establish casinos in Florida and had dispatched lobbying experts to represent his interests. Trump’s interest in Florida casinos was “well known at the time.” But O’Reilly, the “no spin” guy, managed to manipulate the apparent facts to prove that The Trump wasn’t lying. His defense of Trump hinged on the likelihood that Trump did not, himself—in person—approach Bush. Therefore, saith O’Reilly the unspun, he wasn’t lying when he asserted that Jeb’s accusation was false. In O’Reilly’s interpretation of the exchange between Trump and Bush, Trump said he didn’t do it. He, Donalt Rump, did not, himself, make any such overture. So when he said he never did it, he was telling the truth. And then O’Reilly browbeat the Washington Post fact-checker into agreeing with him. The no-spin maestro at work. Oh—the fact checker I checked? Fox News. O’Reilly has at last named the perfect vehicle for his so-called “thoughts”: it’s a book entitled Billy O’Reilly’s Legends and Lies. See? Perfect for O’Reilly. To abandon snark for a moment, the book is an anthology of biographies of outlaws and other sensational characters in the Old West. The book’s ostensible task is to separate the legends and lies from the facts about Billy the Kid, Jesse James, Wild Bill Hickok and others of the ilk. But the maneuver used by the person who actually wrote the book, David Fisher (whose name barely appears on the cover) is simply to label legends and lies as legends and lies, but he tells them anyhow. O’Reilly was the cover subject in a recent issue of Parade, the Sunday newspaper supplement. The article extolled O’Reilly as a one-time teacher and discussed his various “killing” books as accurate history. Reporter Mark K. Updegrove identified Martin Dugard as the books’ “co-author” (and, we may assume, the chief researcher). And one of the books, The Killing of Jesus —which I reviewed in Opus 324—required no more ambitious research than reading a study guide to the New Testament, and it slighted the killing of Jesus by omitting a couple of the things he said while dying on the cross. Maybe those were deemed “religious dogma” rather than historic fact, and since O’Reilly claims the book is actual history, he left out the religion parts. Who can say? But no matter how you explain it, it looks like spin to me.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com/comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

READ AND RELISH “The enjoyment of a work of art, the acceptance of an irresistible illusion, constituting, to my sense, our highest experience of ‘luxury,’ the luxury is not greatest, by my consequent measure, when the work asks for as little attention as possible. It is greatest, it is delightfully, divinely great, when we feel the surface, like the thick ice of the skater’s pond, bear without cracking the strongest pressure we throw on it.”—Henry James in his introduction to his novel, The Wings of a Dove, quoted by Len David Gold in his introduction to Jack Kirby’s Fourth World Omnibus, Volume Three.

EDITOONISTS MEET UNDER GUARD Columbus, Ohio is arguably the center of the cartoon universe. On the campus of Ohio State University in Columbus is the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum, where the world’s largest collection of original cartoon art is housed and the papers and art of some of the profession’s most distinguished practitioners are archived, supplemented by hundreds of books reprinting cartoons or discussing them. The BICL&M is housed in Sullivant Hall (not named for the great T.S. Sullivant but redolent with the association nevertheless), and the rooms of the Library are festooned with names that echo through the history of the medium—Will Eisner Seminar Room, Milton Caniff Room, Jean and Charles M. Schulz Lecture Hall, and the Lucy Shelton Caswell Reading Room, named after the founding curator of the Library. Felicitously, the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists (AAEC) held its 59th annual convention in Columbus, September 3-6, 2015, meeting at the Ireland Library and at the downtown campus of the Columbus College of Art and Design (CCAD), a five-block walk from the Renaissance Hotel where we slept, banqueted and imbibed and confabulated after hours in the hotel bistro. Somewhat less felicitously, the convention was accompanied by a small platoon of security guards and even the occasional bomb-sniffing member of the K-9 corps. There were even plainclothes cops and rumors about a SWAT team, armed and at the ready somewhere on the premises. “They were all very concerned,” Lucy Caswell, one of the host committee, told me, “—the police, the state patrol, homeland security.” They were not alarmed because they believed that the pen is mightier than the sword and could therefore rout the local population. The cause of their alarm was an exhibit of cartoons about the Charlie Hebdo massacre on the second floor gallery of the CCAD’s Canzani Center, where our meetings were held. The exhibit consisted of about three dozen cartoons, mostly by American editoonists (a few of which we’ll look at below). An additional cause was the contingent of cartoonists from other countries—including a couple of the Mideastern countries where all the outrage about cartooning Muhammad originates. With 100 registrants (including 19 from other countries), AAEC managed to get through the weekend without incident other than intellectual stimulation. One of the program sessions, however, was devoted discussing the implications of the slaughter at Charlie Hebdo. Entitled “Free Speech or Hate Speech? Drawing the Line after Charlie Hebdo,” the session was moderated by Jenny Robb, the curator of the BICL&M, and began with a presentation from Mark McKinney, a professor of French and Italian at Miami University, who successfully demonstrated that all the nasty things we’d heard about Charlie Hebdo were wrong. The satiric magazine and its staff are not obsessed with Islam (most of its covers are devoted to French politics, not religion), not racist (the magazine was tried in court in 2007 on charges of anti-Muslim racism and acquited), does not hate Muslims, and not suffering from rampant lack of support among Muslims. Among evidence of the latter, McKinney cited the staff of the magazine, which includes Muslims and other racial and ethnic minorities. Rob Rogers (Pittsburgh Post-Gazette) showed the cartoon reactions of some U.S. editorial cartoonists, and Matt Wuerker (Politico) took the microphone to speak on behalf of Garry Trudeau, whose remarks about Charlie Hebdo suggested that he thought the magazine was ganging up on the helpless and persecuted Muslim minority in France. Trudeau, rather, was urging responsibility: just because we have freedom of expression doesn’t mean we must publish cartoons offensive to Muslims. Another panelist, Michael Alexander Kahn, senior counsel at Crowell Moring and author of books on historic cartooning, reminded us that during the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln was ferociously caricatured and ridiculed. He pointed out that fear of consequences inhibited many American newspapers that refused to publish any of the cartoons associated with the Charlie Hebdo tragedy. Kahn urged newspapers to “at least” be honest about their reluctance instead of claiming “sensitivity” to religious or cultural values that newspapers don’t believe or practice, citing the publication of Holocaust photos as evidence of the usual insensitivity indulged by American journalists. The presentation sparked an energetic debate on the floor, with most advocating for exercise of a sense of responsibility: don’t irritate religious sensibilities. Some, myself included, urged an “absolute” standard of free speech. Freedom of expression cannot survive if it must steer clear of irritating the feelings of this group or that. I’m an absolutist: I accept no formal or informal limits to freedom of expression. Only absolutists are free to exercise individual choice. Whether to cartoon Muhammad (or any other “sacred” figure or image) is therefore a personal decision, which is what it ought to be. Matt Wuerker observed that none of us knew of any anti-West hostility among Muslims until after the Danish caricatures of Muhammad appeared in the fall of 2005. And even then, it wasn’t until 4-5 months after their publication that Islamic outrage surfaced in any notable way. It took that long for the agencies of agitation to muster support. Wuerker’s speculation was that once those cartoons had been published, extremist elements of the Muslim community determined they could “use that”: they could use the Danish cartoons to show that the West hated Islam, thereby fostering Islamic terrorism on an international scale. The agents of Islamic propaganda, Wuerker said, are more sophisticated in advancing their cause than we are in combating it—or in advancing our cause. Steve Benson arose to pose the question he was asked by one of his editors. If he were to do a Muhammad cartoon, he would be putting himself at risk—but also every other staff member of his newspaper (Arizona Republic). By what right was he entitled to endanger everyone around him? This is a legitimate concern of newspaper editors—particularly at those papers with staff working in the Mideast where they are more than usually vulnerable to acts of protest and/or vengeance. I commented that while I am an absolutist, my wife isn’t. And when she learned that I’d posted a caricature of Muhammad to this site several years ago, she reacted like one of those concerned newspaper editors who have staff in vulnerable places. What if some wild-eyed Islamic extremist attacked members of our family—our grandson, in particular? Was I crazy? I took down the caricature of Muhammad. (But it was a personal decision: I’d rather keep my wife happy than cause her consternation.)

THE CONVENTION COMMENCED on Thursday evening with a presentation by the inimitable Mike Peters (Dayton Daily News and the syndicated comic strip Mother Goose and Grimm), who launched into a series of comedic anecdotes about some of his misadventures. Peters’ manner is feverishly breathless, veering off, as he continues, into hilarious hysteria. To say that he told a story about how, when attending a social event at a church, he stood in line next to the priest without noticing he was standing next to the priest, and, thinking erroneously that the priest was a Marine friend of us, reached around and grabbed the man’s “package” and then, discovering his mistake, apologized and explained his behavior by saying, “I thought you were a Marine”—to say this much scarcely does justice to Peters’ presentation or his manner. He was having such a good time telling stories like this that he kept asking his wife if he could tell just one more. And he did. A couple of times. Each day of the convention began with a 5-block stroll up Gay Street (yeah, that’s its name) to the CCAD, where we collected a continental breakfast and then ate and conversed at round tables in the facility’s lobby. At noon on both Friday and Saturday, we were back at conversation at those round tables after picking up a tray of lunch at the buffet table. All very convivial. The topics of the presentations on Friday ranged across the interests of editorial cartoonists. In the first panel of the day, several editoonists (Chip Bok, Creators Syndicate; Gary Varvel, Indianapolis Star; Dwayne “Mr. Fish” Booth, freelance; and Adam Zyglis, Buffalo News) discussed their targets in the looming presidential primary season, sounding much like the pundits we all encounter on cable tv, hour after hour. Good fun for political junkies like us. In the next panel, Steve Hamaker (Plox and Jeff Smith’s Bone) and Kevin “KAL” Kallaugher (Baltlimore Sun and The Economist) talked about coloring cartoons and what impact color had on the message. They were followed by two cartoonists (Steve Sack, Minneapolis Star Tribune; and Silgne Wilkinson, Philadelphia Daily News) who displayed the “fine art” they practiced in their off hours. The celebrated satirical illustrator and caricaturist Steve Brodner showed samples of his work, saying: “My idea of caricature is ... story.” His likenesses are inevitably garbed and/or accoutered in ways that tell the subjects’ stories, linking the faces to the news they’re making. Then graphic novelist Peter Kuper (Mad’s “Spy vs. Spy” and co-founder of the political graphics magazine, World War 3 Illustrated) offered examples of his endeavors, observing along the way that the notion of red and blue states is “wrong—we’re all on the same path.” The last presentation of the day took place at the BICL&M. The authors of What Fools These Mortals Be: The Story of Puck—Michael Alexander Kahn and Richard Samuel West—conversed about the genesis of the book and its impact upon American publishing and about the artistry of the cartoonists that the magazine’s founder, Joseph Keppler, mustered to its weekly task. After which, we strolled through the Ireland galleries and viewed two exhibits—tearsheets from Puck and cartoons about World War I—as well as other treasures in the Ireland collections from Thomas Nast to Bill Watterson.

SATURDAY BEGAN with “Animating Satire,” a presentation of animated editoons by Mike Thompson (Detroit Free Press), Ann Telnaes (Washington Post), and Mark Fiore (freelance). I detected a little defensiveness in the presentations, and when I asked Telnaes about it, she said: “Animation is still not accepted as professional”—which seems odd, now that two or three editoonists have earned Pulitzers with their animations. Several cartoonists from other countries took to the stage to discuss how they fared in variously oppressive regimes. The executive director of the Cartoonists Rights Network International, Robert “Bro” Russell, ended the presentation with this admonition addressed to Islamic extremists: “You want us to stop cartooning Muhammad? Stop cutting off heads. You want respect? Stop abusing women. You must earn respect: it is not given freely.” New Yorker cartoonist Liza Donnelly showed samples of her cartoons under the heading “Politics Unusual at The New Yorker: Past and Present.” And after the “Free Speech” panel, the legendary Village Voice cartoonist—playwright, graphic novelist, children’s book author, and grand old man of comics, full of history and eccentric albeit accurate interpretations thereof—Jules Feiffer joined us via Skype. Responding to questions posed by Jeff Danziger (New York Times Syndicate), Jack Ohman (Sacramento Bee) and occasional others (Liza Donnelly: “You look great.” Feiffer: “I’ve been told that before.”), Feiffer talked about the evolution of cartooning through the funnybooks of the 1930s to the graphic novels of today, pausing en route to extol the fascination of motion pictures and their impact upon American culture. The Skype projection was huge: Feiffer’s face towered over the auditorium from just above the stage. Nate Beeler (Columbus Dispatch) thought Feiffer was like the Wizard of Oz, looming up on the screen while we asked him questions. Technically, Skype worked well. And as a result, aesthetically, Feiffer’s warmly skeptical personality came through, evaluating history through his own experiences, embroidering with humorous asides and observations as he went. “Fortunately,” he said, “at 87, you don’t remember what you did wrong.” At the concluding banquet on Saturday evening, out-going president Jack Ohman thanked everyone for being terrific. “I took the job because I love the people in the group—period,” he said. “I started as a cartoonist in Columbus at age 20, taking over Jeff MacNelly’s client list, so it was very poignant to return to Columbus after 34 years and be president of the AAEC—something in 1981 I would never have guessed I’d do.” Past presidents Mark Fiore and Matt Wuerker were presented with the Ink Bottle Award for their dedicated service to the profession, and Bro Russell presented the 2015 CRNI Courage in Editorial Cartooning Award to Atena Farghadani, the jailed Iranian artist who last spring was sentenced to more than 12 years in prison for her editorial art and community activity critical of the government. “Atena is among the most courageous humanitarians we know of,” Russell said (in an interview with Washington Post’s ComicRiffs. “When they tried to intimidate her with physical torture, she just punched right back — she refused to be brought down. Her imprisonment under this regime is one of the most unjust acts in Iran’s modern history. “This year,” Russell continued, “the decision about the award recipient was easy. It was a unanimous decision by the CRNI board of directors.” Jeff Danziger finished the evening with a short speech that included two jokes from Arnie Roth and observations about the impossibility of satirizing clownish political behavior.

ON SUNDAY, after the morning membership meeting (see minutes reported elsewhere), we were conducted on tours of the Ireland archives where we saw samples of rare cartooning items in the archival vaults. Among those, the Hale Scrapbook—a British treasure containing cartoons, engravings, letters, newspaper clippings, wood cuts, broadsides, sketches, paintings and other miscellaneous materials from 1746-1830, assembled, it is supposed, by some avid fan of cartooning and politics. The Scrapbook, originally acquired by editoonist Draper Hill and a part of the Draper Hill Collection in the Library, has been painstakingly reconstructed and has been digitized and can be viewed online. Other collections in the Library’s vaults include the extensive newspaper comic strip clippings of Bill Blackbeard’s San Francisco Academy of Comic Art; Will Eisner’s papers, original art and published work; Milton Caniff’s correspondence, original art, comic strip proof sheets of all his comic strips; and the Biographical Registry of Cartoonists, clippings and biographical information on more than 5,000 cartoonists (searchable online). Late that afternoon, survivors re-convened for a picnic at Huntington Park where the Columbus Clippers were playing the Toledo Mud Hens. The Convention ended officially with a “dead dog” gathering at a secret location in Suite 2128 of the Renaissance Hotel.

CHARLIE ON

DISPLAY. I photographed a few of the couple dozen editoons reacting to the Charlie

Hebdo massacre last January, and I’ve posted them just at the corner of

your eye. Going counterclockwise, we begin at the upper left with Matt Wuerker’s image depicting the plight of an editorial cartoonist in the age of the Cutthroat CalipHATE and oozing a little with sarcasm about the efforts of the Department of Homeland Security. Below Wuerker is a cartoon by Jason Chatfield, who inherited Australia’s iconic kid comic strip, Ginger Meggs. Here, another kid picks up the pencil of a fallen cartoonist. W. Cullum Rogers’ cartoon is one of the three or four most powerful statements in response to Islamic hooligan rampages of terror against cartoonists. God, understandably, does not comprehend the reasons for the slaughter presumably committed in his name. Next around the counterwise clock is Jack Ohman, whose images constitute a chorus of mockery for the terrorist. But at the last stop on our tour, Kevin “KAL” Kallaugher’s cartoon is the most astute deployment of the medium. With great ironic effect, it deploys against terrorists the editoonists most powerful weapon, laughter, using a device unique to cartooning—the speech balloon—and sequential panels. While cartoonists worldwide used the pencil as a symbol of defiance and resilience, KAL gives the power to the speech balloon, which gives mocking laughter an irrepressible force. You can kill us, it seems to say, but you cannot stop us from laughing at your misbegotten crusade.

MOTS & QUOTES “I never learned anything while I was talking.”—Larry King “Never buy anything that you can’t illustrate on the back of a napkin.”—Investigator Peter Lynch “Human happiness and moral duty are inseparably connected.”—George Washington

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics An admirable first issue must, above all else, contain such matter as will compel a reader to buy the second issue. At the same time, while provoking curiosity through mysteriousness, a good first issue must avoid being so mysterious as to be cryptic or incomprehensible. And, thirdly, it should introduce the title’s principals, preferably in a way that makes us care about them. Fourth, a first issue should include a complete “episode”—that is, something should happen, a crisis of some kind, which is resolved by the end of the issue, without, at the same time, detracting from the cliffhanger aspect of the effort that will compel us to buy the next issue.

LET US BEGIN with a comic book poster child for what not to do in a first issue. Christopher Sebela’s inaugural issue of Welcome Back begins with a three-page introduction that takes place (it sez here) in 1281 C.E.: there’s a killing and then a two-page spread of chaos. Next, we’re in Kansas City in 2015, walking the street with a girl who is muttering about being 26 years old, jobless, homeless, and friendless (although we soon meet her roommate, who seems friendly enough). She also tells us her preferred name is Mali, not Maizie Lirah, the name by which her smart phone addresses her. She mutters something about moving to Kansas City to make a fresh start because she’s the daughter of the devil. Next, we meet her roommate and her pet dog, Showtime, and her boyfriend shows up and we’re treated to a copulation sequence, but then Mali has what I assume is a bad dream during which she breaks her boyfriend’s nose, and he, understandably, stalks out, leaving her naked in their bed. “It was easy,” she says to Showtime, “—crossing the boyfriend off the list.” And that concludes what is the only episode in the book that makes any internal sense. It shows our heroine to be a somewhat unfeeling but disturbed bimbo. On the next page, we meet a costumed ninja-like woman who is apparently stalking someone with the intention of killing him/her. After that, we alternate between Mali and the stalker, each muttering to herself in different colored caption boxes. But I’m not entirely certain of that. The stalker finally kills her victim, alluding to some sort of “war” and to her need to find someone—probably Mali, but we’re not sure. At the end, Mali returns home from a party and, entering her apartment with gun drawn (we don’t know where she got the gun), she finds sitting on the couch what seems to be an eight-year-old boy who claims to be her father (the devil alluded to early on). There’s entirely too much unexplained mystery here. Hints and allusions are much too cryptic and mysterious. Mali may be a somewhat sympathetic person, but the drawn pistol at the end suggests she has something in common with the stalker. What? Hint, hint—but no overt explanation. However, it’s all explained in a short paragraph of text on the Boom Studios promotion page; to wit: “Mali and Tessa have lived hundreds of different lives throughout time, caught up in an eternal cycle as they take part in a war so old that neither side remembers what they’re fighting for anymore. As Mali wakes up in her newest life, she suddenly becomes self-aware and starts to question everything, especially why she continues to fight. But elsewhere, Tessa is already on the hunt.” “On

the hunt”—for Mali? I assume from this wholly external textual exposition that

Tessa is the stalker and that she’s “on the hunt” for Mali. The paragraph also

clears up some of the incomprehensible mystery that surrounds the two

characters. Now a lot of the action we’ve witnessed makes some sort of sense.

But this kind of explication should occur in the context of the story—not as an

external promotional paragraph which a reader making his/her way through the

first issue of Welcome Back might very well overlook. The story is very well drawn by Jonathan Brandon Sawyer, but his passion for detail very nearly overwhelms the narrative purpose of the pictures. He crams too much detail into panels too small to carry all that visual information. Many of the pictures are so tiny that they can’t reveal what they’re intended to reveal. Mali has a tattoo on her left shoulder, but we can’t make out what it is and therefore we don’t know its significance, if any. For the sheer sake of clarity, Sawyer ought to include some close-ups or mid-range visuals. There’s a lot of good stuff in this book, but it’s badly arranged and presented for a first issue, which ought to tempt us into buying the second. This one doesn’t.

AFTER DC’S CONVERGENCE, all their books were supposed to make sense. But they don’t. At least the two I dipped into don’t make much sense to me. I was also persuaded by something I obviously misread that the DC titles would abandon a lifetime of issue-to-issue continuity in order to be single-issue stories, done in one. I was wrong about that. Continuity still prevails. But to no avail for me. I picked up No.3 of We Are Robin. I had the notion that it would be about Batman’s sidekick. Mebbe so, but I didn’t catch a glimpse of him in this issue. Instead, it appears to be about a band of young trouble-shooters all wearing Robin-like shirts. It is very attractively drawn by Jorge Corona, but I had to look up his first name in Previews; his last name is listed on the cover, but I could find no byline inside. Written by Lee Bermejo, the story is awash in information that I could understand only if I’d read No.1 and/or No.2. Continuity lives, with a vengeance.

WHEN I SAW THAT John Romita, Jr was going to draw Superman, starting with No.42, I quickly mustered the money to buy a copy. Then I made the mistake of reading No.43 before No.42. It opened with Clark Kent in bed with Lois Lane, but Clark is merely recovering from the effects of a “solar flare,” a new Superman maneuver in which he blows himself up and destroys the immediate surroundings. There’s no canoodling: Clark is naked (his clothes burned off him in the flare) but Lois is fully attired. Superman, it seems, has lost some of his power in his current confrontation with an interstellar gang of baddies led by Hordr, who promises to reveal to the world Superman’s civilian identity if the Man of Steel won’t play ball with Hordr. But Lois foils the plan by broadcasting Superman’s secret identity world-wide. Now Hordr has no power over Superman. But Superman wishes Lois hadn’t done that. Then I went back to read No.42, in which Lois finally puts two and two together (after how many decades?) and decides that Clark Kent, without his glasses, is really Superman. It’s a touching scene in which she rips Clark’s shirt off to reveal his Superman costume beneath. In No.43, she cutely refers to our steely hero as “the cape you” as distinct from “the glasses you” (i.e., Clark Kent). In another Superman title, Superman is hanging out romantically with Wonder Woman. But in the title at hand, Lois is looking longing at Clark, and he, at her. This promises to end badly no matter how it works out. Unless— My guess is that the love triangle will be resolved by becoming a quadrangle. Clark and Lois will get it on, and meanwhile, Superman and Wonder Woman will continue their romance. Ordinary people will couple; superhero people will couple. The plain geometry is hard to avoid. Romita

didn’t disappoint. Inked faithfully by Klaus Janson, Romita’s I’ll probably buy the next issues, but only because of Romita/Janson. Well, also to see if my prediction is accurate.

SHIFTING OVER THE MARVEL, in the Secret Wars title 1872, with Steve Rogers/Captain America as the sheriff in the town of Timely (hoo-ha), Rogers is shot and killed in No.2. That leaves Tony Stark as the hero in residence, and he’s a drunk. So Fisk, ostensibly the mayor of the little town, is free to prevail in every nook and cranny. Except— Except that the gutless newspaper reporter, Ben Urich, finally resolves to do something. What, we’ll know, I assume, in the next issue. And maybe Rogers will come back to life, too.

IDW IS MAKING another of the many attempts by assorted publishers to bring Sherlock Holmes into funnybooks. Although Holmes—with Tarzan and Mickey Mouse—numbers among the world’s most recognizable fictional heroes, he doesn’t translate well into a visual medium. Conan Doyle’s consulting detective lives through words on the page, not pictures. Hence, alas, his highly verbal gyrations in every one of the cases he solves (with the possible exception of The Hound of the Baskervilles) do not translate well into a visual medium. The work at hand, based upon Nicholas Meyer’s 1974 novel and subsequent 1976 movie, The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, is no exception. Holmes, it seems, has become addicted to cocaine in a “seven-percent-solution” and Watson sets out to cure him of his addiction by taking him to Vienna where he is treated by Sigmund Freud and cured. Meyer’s story is intended to bridge the three-year gape in the Sherlockian canon between “The Final Problem” in which Holmes is presumably killed by falling off a cliff in Europe while struggling with the evil Professor James Moriarty and “The Empty House” in which Holmes, not dead at all, returns to London and resumes his detective practice. Both of these stories, Watson assures us, are fiction not, as all the other Watson-written stories are, real accounts of actual events. The two faux adventures are supposed to mask what really happened during the interval between them: Holmes, cured of his cocaine habit, wanders Europe as therapy. Holmes’ delusion about the alleged criminality of Moriarty is a defense mechanism masking a traumatic event of the detective’s childhood: his father killed his mother for committing adultery and then killed himself. Holmes’ tutor informed the youth of this tragedy; the tutor was James Moriarty. And in constructing a subconscious defense against acknowledging the tragedy, Holmes made Moriarty a colossal bad guy. Meyers wrote two other Holmes pastiches, The West End Horror (1976) and The Canary Trainer (1993), the latter an account of what Holmes did in Europe before returning to London. The IDW comic book, written by David and Scott Tipton and drawn by Ron Joseph, begins in 1939 with Watson telling of Holmes’ cocaine addiction many years before and his delusion about Moriarty. Watson and Holmes’ brother Mycroft resolve to take Holmes to see Freud, who, at the time of this narration, is a virtually unknown doctor of some sort. Despite the promise of this kind of narrative complication, the first chapter in the story (this issue) consists mostly of speech balloons in which the characters ponder the issues and narrative scraps depicting Holmes at his lowest ebb. Joseph manages to vary spectacularly the perspective on the unending series of talking heads, thus imparting to the tale some measure of visual variety, but it’s still a talking heads story. And to the extent that it will remain true to the original story, it’ll be talking heads most of the time. A central episode in which Holmes’flagging addictive mind is revived is a mystery involving a kidnaping and a plot to launch a multi-national war in Europe, which Holmes momentarily thwarts. But all the rest of the story will be highly verbal.

ANYTIME Mike

Mignola is drawing as well as writing Hellboy, I pick up a copy.

QUOTES AND MOTS “In theory, there’s no difference between theory and practice. In practice, there is.”—Yogi Berra Today, when a Republicon governor in Texas calls out the National Guard to ensure that Bronco Bama doesn’t stage a military coup, “we just shrug because it’s just another Tuesday in the lunatic asylum of American politics.”—Leonard Pitts, Jr A total of 51 U.S. law enforcement officers were killed in the line of duty in 2014, saith The Week, quoting the FBI—nearly double the number, 27, killed the year before. Forty-six were killed with guns, 10 of them during routine traffic stops.

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy WHILE IMMIGRANTS from North Africa and the Middle East are drowning in the Mediterranean in their desperation to escape the miserable conditions of life in refugee camps in Jordan and Lebanon and Turkey and the savage, brutal oppression of the Cutthroat CalipHATE in Syria and, in this country, the number of homeless children in public schools has doubled since 2006-07 (from 679,724 to 1,360,747), our so-called “news” media focus on the petty preoccupations of a religious zealot in Kentucky. Yes,

the Big News this month so far is not, surprisingly, Donalt Rump. Nope: it’s a

county clerk who went to jail rather than issue marriage licenses to gay

couples. And our first visual aid starts with a couple images pertinent to that

monumentally important issue. At the upper left, Kevin Siers starts us off with a memorable image of Kim Davis on the day of her release after five days in the pokey. Arms raised in the traditional gesture of victory, she is bookeneded by two other religious zealots—Mike Huckabee on her right, and a theocratic mullah on her left. It’s the mullah that tells Siers’ tale, reminding us that in Iran, the Islamic state that works in the Mideast, all civic and governmental power is in the hands of the state religion. The implication is that with Davis’ victory, the United States has become a theocracy with Christianity as the state religion. But Davis was not, actually, victorious: only the misguided Religious Right claim that her release is a victory for religious freedom. The constitution guarantees freedom OF religion, meaning that one is free to practice one’s religion; it does not guarantee religion a freedom FROM the laws of the society in which it is practiced. Davis’ religion does not presumably include as a basic tenet that she should recruit anyone she meets into her religious fold. So she is free to practice her religion: nothing in legalizing gay marriage prevents her from practicing her religion unless her religion mandates proselytizing. The whole issue is ridiculous on its face. A pertinent tweet: No one’s being jailed for practicing her religion; someone’s being jailed for using her position in government to force others to practice her religion. This sainted woman took a while to arrive at her sainthood. Turns out she’s been married four times, twice to the same man, but between the marriages, she managed to have twins out of wedlock. So much for the sacrament of marriage. Bill Maher had the last word on Kim Davis’ marriage license policies: all those marriages, he said—“that’s why she won’t issue marriage licenses to gay couples: she wants them all for herself.” To dredge up Davis’ sad marital history is patently unfair: those were presumably the sins of her youth; older now, she’s found religion and has given up sinning. Davis’ choice was to obey the law of the land (as recently established by a Supreme Court decision acknowledging the right of gays to marriage) or resign. Not willing to do either, she is in contempt of court for refusing to obey the law. So she’d rather go to jail than give up her paycheck ($80,000/year). How saintly is that? As an elected official, Davis could have maintained that resigning would insult those citizens who voted her into office. But she has never referred to her status as an elected official: she says only that she recognizes no authority but God’s. (See About the Bible and Its Reputed Prohibitions at the end of this posting.) That is undoubtedly her conviction. What, then, of her having sworn as an elected official to uphold the laws of the state and of the United States? God evidently supersedes such oath-taking. But if she can’t do the job as she’d sworn to do, she ought to resign. (And give up that $80,000 a year?) Kareem Abdul-Jabbbar at Time.com says that letting religion determine the civic responsibility of government officials leads to chaos. Can Christian court clerks now refuse to marry divorced people too “because Jesus spoke against divorce?” Should an Orthodox Jewish motor vehicle clerk be allowed to deny driver’s licenses to people who eat ham or drive on Saturday? No. Clearly. Government officials simply cannot cite their religious faith as justification for defying the law. “Rule of law is one of the most important things between us and barbarianism,” said Megan McArdle at Bloomberg View. “Conservatives who applaud ... Davis should take a long, hard think about how they’d feel if President Obama took a bold stand for freedom of conscience by slapping Hobby Lobby with fines in open defiance of the Supreme Court.” The very thought proves the ludicrous impossibility of Davis’ stance. And to prove the point, next in our clockwise rotation through the editoons at hand, Mike Luckovich supplies vivid images of Davis at work in other licensing venues. Upon her release, Davis returned to work, saying she would not interfere with any of her employees’ issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples. That’s what she should have done in the first place rather than make a spectacle of herself. She says she doesn’t want to be in the spotlight; and yet she chose a course of action that did exactly that. She is proving adept at the American politicians stock in trade—hypocrisy. We should waste no more time in pondering this dubious confrontation in the culture war. But, with Benjamin L.Corey, “I wonder how much support I’d get if I were elected a town clerk but refused to issue gun licenses because guns are against my religion.” A happy segue, I submit, to the other two cartoons on our first exhibit (and, not at all incidentally, to an issue we ought to be addressing instead of the Religious Right’s misguided crusade—namely, the gun control issue, which, alas, is still alive and well). Rob Rogers at the lower right performs for the National Rambo Association’s edification the same sort of rhetorical nonsense exercise that Luckovich just above offered to the Religious Right. Words rather than pictures are at the heart of both admonitions although the fish symbol in Luckovich’s second panel adds a weighty dimension to his commentary. With the last word (for this posting), David Fitzsimmons propounds a devastatingly sarcastic view of many—too many—of our elected representatives in government. “I like your courage, boy,” is the grace note, asserting just the opposite.

THE USUAL

POLITICAL SHENANIGANS are blatant in our next exhibit. Next around the clock, Joe Heller plays with Hillary’s campaign symbol, turning an array of Hillary arrows into a gigantic arrow pointing at another candidate. Below Heller, Clay Bennett provides a visual demonstration that reveals what Republicons advocate for with their continuous plea for more walls. Every wall here guards a specific demographic from any interference from any other demographic: behind Republicon walls, the country will become a pyramid of partitions isolating us from each other. Steve Sack’s cartoon at the lower left was produced some months ago, but it is as startlingly acute today as it was then, depicting a timorous line-up of Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderms, all herded together by the power of Grover Norquist. Norquist, you’ll remember, is the guy who holds the “no more taxes” hatchet over the heads of all elected officials: any one of them who votes for a new tax or increasing an older tax will risk Norquist doing a hatchet job on him in the next election—telling everyone that the candidate is in favor of taxes. The kiss of death in GOP politics these days. And

in our next visual aid, we summarize some other issues of the day, starting

with a couple of anniversaries. Below them, Jeff Danziger presents an image reversing the lion-killing episode earlier this month and showing thereby the pointlessness of the would-be hunter-warrior dentists of the world. (Walter Palmer, the culpable dentist, says he didn’t know the lion was a national shrine and if he had, he wouldn’t have “taken” it. “Taken” tells all: like many big game hunters, he doesn’t “kill” his prey—he “takes” a souvenir of his manly skill at murdering animals who are virtually defenseless against the killing contrivances of modern man.) Next, Kevin “KAL” Kalaugher addresses the same issue and uses a series of pictures to heap up evidence and then, like Danziger, condemns the ludicrous world-wide consternation over the death of Cecil the Lion by comparing the death of one lion to that of thousands of Americans killed every year by guns. In

our next exhibit, reproductive rights are among those that must be protected if

we are to survive the ministrations of big game hunters and the National Rambo

Association. Next on the clock, Signe Wilkinson takes up a related issue in a startling image that asserts that the male population is as much to blame for abortions as the female population. How about them apples, Mrs. Goldfarb? Let’s try a little equal treatment under the law. Speaking of which—laws—we have Mike Lester’s disapproving view of Mitch McConnell’s sheepish surrender to the inevitability of Bronco Bama’s triumph in the Iran agreement fiasco. The assumption is that Congress, by law, has a voice in such matters. Treaties, yes; but not “agreements,” the carefully chosen lingo describing the Iranian deal (which involves not just the GOP-despised Obama but five other nations). Scott Stantis has a more realistic assessment of the outcome of Congressional action on the Iran deal—voting approval but with crossed fingers, a sign of hope rather than conviction. Our last image is Pat Bagley’s interpretation of the photo of 3-year old Aylan Kurdi, washed up dead, like so much flotsam on a Turkish beach, a casualty of the desperate flight of Syrians and others from the miserable straits of their existence in refugee camps and oppressive regimes in the Mideast. Bagley’s use of the term “flotsam” is an ironically bitter condemnation of a world to which drowned Aylan is only so much debris. Since

the second Republicon Debacle finished only a few days ago on September 16 just

before I close this installment of Rancid Raves, I must—as usual in the grip of

an eerie compulsion—take a quick look at the results. Realizing, first, that the candidates assembled pay gushy homage to “the patron saint of all true conservatives” because they’re meeting at the revered Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, Egan goes on to observe that the GOP has moved so far to the right in recent years that “Reagan would never be allowed on stage.” The real Reagan—not the mythic imaginary one—granted amnesty to nearly 3 million illegal immigrants, vastly increased the size of the federal government, raised taxes at least four times, and nearly tripled the national debt. On abortion, Reagan gave lip-service to the “pro-life line” while President but as governor of California, he signed a legalization bill that enabled abortions to rise from 500 a year to nearly a million. On gun control, he supported the Brady bill and an assault weapons ban. He supplied money and arms to the Afghan rebels that would evolve into the Taliban. He was commander-in-chief when 248 Marines were killed by terrorists in Lebanon—a debacle that “makes Benghazi look like a game of pinochle.” By today’s standards, Reagan was a conservative “heretic.” At the lower right, Gary Varvel emphasizes The Trumpet’s debating skills; good caricatures but apart from establishing the scene of a debate, the pictures don’t add anything to the message. At the lower left, Stuart Carlson changes the subject to alert us to the Next Crisis that will be brought to us courtesy the GOP Tea Baggers. The picture puts the action in a movie theater, without which the joke wouldn’t make sense, and the metaphor of a motion picture permits Carlson to make his point: we’ve all seen this before, there’s nothing new here, just keep moving along. It promises to be a boring movie, another display of politicians’ complete disregard of the public welfare in favor of Hollywoodian posturing. Meaningless but annoying. ’Nuff said, kimo sabe.

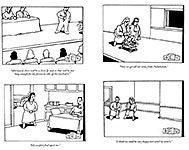

FINALLY, HERE

IS A QUARTET OF CARTOONS by Dave Fitzsimmons, whose way with a pen makes

him unique among the editooning coterie. His characters, both face and figure,

are designs not portraits. He is able to make even his caricatures into

designs—an achievement without equal in editooning. The newspaper reporter’s mangling of facts and then declaring, “I love my job,” is as enthusiastic a condemnation of the failure of America’s Froth Estate as any I’ve seen. Below that, the icons of Mount Rushmore (wonderfully designed and accurate caricatures) echo the Founding Fathers’ concern about “faction”—the emergence of political parties demanding a steadfast loyalty that assures the party’s continuing in power but ignores the welfare of the nation. What they feared has arrived. And Fitz’s exposure of the folly of McCain’s tirade about Benghazi is an older cartoon but still an accurate image for the Republicon frenzy over Hillary’s e-mails: the GOP desperately wants to make her a criminal so we’ll all forget the thousands of people killed in Iraq and Afghanistan because of the GeeDubya administration’s deluded notions about why we should invade countries in that part of the world.

NEW YORKER CARTOONS: PART ONE I can’t say how

many parts this examination of The New Yorker’s cartoons will ensue.

I’ve been toying with doing a long essay on the magazine and its cartoons, but

I keep putting it off because it seems a little ambitious for my moods at

present. My mood at present favors doing short bits not long essays, so I’ve

decided to tackle the erstwhile essay piece by piece—beginning, this time, with

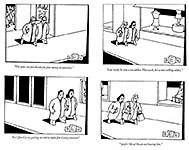

the accompanying full-page cartoon by BEK (Bruce Eric Kaplan). The New Yorker doesn’t publish many full-page cartoons these days although it used to, back in the good old days when its founding editor, Harold Ross, was still at the helm. (He died in DATE after xxx years of helming.) In fact, Ross, recognizing in his vague way that the size of a cartoon had something to do with its worth (because, perhaps, a cartoonist had to spend more creative energy—not to mention time—in the execution of such a large image)—Ross established a complicated pay scale for cartoons in which part of the formula was the size, in square inches, of the cartoon. Thomas Kunkel in his biography of Ross, Genius in Disguise, tells the story of an idea- generating session between the celebrated cartoonist Peter Arno and one-time art editor Albert Hubbell. Hubbell went to Arno’s Park Avenue apartment one afternoon where he found Arno, “a creature of the night,” still in a silk dressing gown. Arno fixed himself a hamburger and sat down to hear Hubbell’s ideas. “One that Hubbell liked and pitched hard involved a billiard table,” Kunkel writes. “But in no time, Arno was frowning. It turned out that Ross paid him a substantial bonus for full-page cartoons, which presupposed vertical concepts, so a billiard table was altogether too lateral to even consider. ‘Wait a minute, Hubb, wait a minute,’ Arno said, ‘—let’s go for those pages.’” Looking at BEK’s full-pager, it’s clear that the gag doesn’t require a vertical dimension: as a street scene, it’s more horizontal than vertical in concept. The soaring white wall behind the characters has been insinuated into a horizontal cartoon to give it the aura of verticality. Nor is the artwork of such intricacy that Kaplan needs all the space that a full page allows him. The most complicated aspect of the drawing is the tangled hair of the two people and their dog. In fact, the drawing screams stark simplicity not intricate complexity. So how is it entitled to a full page? It isn’t. Particularly in these days when the magazine allows so few full-page cartoons. However, this cartoon is fairly typical of what, for the sake of this essay, I am calling the “old style” of New Yorker cartoons. They are commandingly inert. They sit quietly on the page—well behaved, hands folded in their laps— motionless, inactive. Static, still. Torpid. In the typical inert New Yorker cartoon, the pictures have almost nothing to do with the words. And vice-versa. The pictures tell us who is talking, but the cartoon exists for the talk: the so-called comedy of the cartoon is not at all illuminated by the picture. As I’ve been saying for several centuries now, in the best cartoons, the verbal and the visual blend, neither the words nor the pictures making the same comedic sense alone without the other as they do together. The typical New Yorker cartoon of the “old style” is therefore not a good cartoon. In fact, the “old style” inert New Yorker cartoon is a bad cartoon. And

Kaplan’s cartoons are, more often than not, a virtual textbook in the “old

style” inertness. The words and pictures are so completely independent of each other that we could switch the captions around and the alleged humor is wholly unaffected. In fact, I’ve switched the captions on two of these cartoons. Can you tell which two? I thought not.

BEK’S CARTOONS

DO NOT ALWAYS FAIL as cartoons, as blends of words and pictures. In our next

visual aid, the verbal and the visual work together to achieve the cartoon’s

humor. The picture in the next cartoon around the clock offers an explanation for the speaker getting all of her news from Nickelodeon: the household watches television appropriate to the interests of the child. Below that, the empty rooms add whatever poignance we can find in the emotionless utterance of the man. An empty room with two people bracing their feet—inert. And the last cartoon’s picture sets us up to understand that the caption is prompted by whatever food the man at the table contemplates before him. In