|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 318 (November 23, 2013). We celebrate the opening of the cathedral of cartooning arts, the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum at Ohio State University, with a report on the Festival of Cartoon Art that took place the same weekend, November 15-17, and a short history of the place. We also review books (the new Zits novel and Gaimen’s latest) and others, all of which are more generously illustrated than the usual prose tome (about which we ask: do the pictures act in concert with the words as in comics? Or are they merely illustrations), and we list the Stanley winners in Australia and report on Apple’s banning Sex Criminals, Fantagraphics getting Kickstarted, and Mickey Mouse putting on gloves among other news. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department—:

NOUS R US Comics on Broadway: Fun Home, Spider-Man Trudeau’s Alpha House Fantagraphics Gets Kickstarted Islamic Ms. Marvel Mickey Mouse’s Gloves Maggie Thompson’s Comic Book Sale

Sex Criminals Banned by Apple Stanley Awards in Australia History of the Stanleys

BILLY IRELAND CARTOON LIBRARY OPENS GRANDLY Lucy Shelton Caswell And the Cathedral of Cartooning Arts Academic Pre-Con The Festival Itself The Crisis in the Newspaper Comic Strip Kingdom Nancy Silberkleit The Ultimates Edition of the Cartoon Arts Festival

EDITOONERY Two Notables from the Past Month

THE FROTH ESTATE And the Kennedy Assassination Explained

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Cross-overs in the Funnies—Risky?

BOOK MARQUEE: REVIEWS OF—: The Madam Paul Affair Lost in the Alps Chillax (a Zits novel) Fortunately, the Milk (by Neil Gaimen) Andy Gump: His Life Story (an antique) The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE John Byrne’s Spoof, Triple Helix

Passin’ Through Walt Disney’s Daughter

NOT ONE DIME A Radical Revamp of Campaign Financing

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

Alison Bechdel’s graphic novel about growing up as a nascent lesbian in a funeral home run by her closeted gay father who eventually killed himself just as his daughter was awakening to her sexuality has debuted off Broadway as a “shattering musical,” saith The New Yorker —directed by Sam Gold, who “honors the kitschy strangeness of the Bechdel family, whose pain and joy and ambivalence come alive in Jeanine Tesori and Lisa Kron’s rich neo-Sondheim score.” “Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark,” which may be the most expensive show ever mounted on Broadway, may also rack up historic losses—perhaps as much as $60 million—when it closes on January 4. Apart from the record-setting $75 million capitalization, reports Patrick Healy in the New York Times, the show had enormous weekly expense in its special effects laden production, and then this fall, as ticket sales declined sharply “because of competition from hotter musicals and a lack of star attractions in the cast,” it incurred operating losses of hundreds of thousands of dollars every week it continued. The investors attributed the loss to the show’s “unsustainable budget and the shortcomings in the music, by Bono and the Edge of U2—a score by famous artists that was supposed to be a selling point with audiences but ended up being dismissed by critics.” Garry Trudeau’s “Alpha House,” a half-hour comedy series that’s now streaming for your fickle platform pleasure on Amazon.com, is about four Republican senators who are roommates in a Capitol Hill townhouse {washingtonpost.com}. Meanwhile, Trudeau is back at the drawingboard, and new Doonesbury strips started in the papers on November 18. Neil Gaiman’s bestselling urban fantasy novel Neverwhere has been restored to the curriculum at New Mexico’s Alamogordo High School, ending a temporary suspension due to a parental challenge. According to the school’s media specialist, the book had remained available to students in the library, although it had been pulled from English classes for several weeks until a review committee found it to be suitable and age-appropriate for study {slj.com}. Fantagraphics went to Kickstarter for financial help to get through the coming publishing year. The death last summer of Kim Thompson, one of the company’s founding partners, has had repercussions beyond the purely emotional. Thompson edited Fantagraphics’ European graphic novel line, 13 titles of which, scheduled for the Spring-Summer season, have been cancelled or postponed. Meanwhile, as publisher Gary Groth explains, the company’s fixed costs continue unabated. Without the projected revenue that selling those books would yield, the company’s cash flow was severely impacted. To make up for the shortfall and to support the publishing of 39 titles scheduled for spring and summer, Fantagraphics set out to raise $150,00; by November 21, loyal fans and supporters had pledged over $188,000. Every dollar over the initial goal will enhance the final products. The fund-raising ends December 5, so there’s still time to get on board; about 100 premiums are available, depending upon the amount donated. Marvel’s new Ms. Marvel title, due out in February, features a teenage Muslim girl from Jersey City as the title character. The series will be written by novelist and comic scribe (Cairo, Air) G. Willow Wilson, a convert to Islam, who told the New York Times that the title will deal with conflicts between familial and religious edicts and superheroics. "I do expect some negativity, not only from people who are anti-Muslim, but people who are Muslim and might want the character portrayed in a particular light," she said. The title will be drawn by Adrian Alphona (Runaways). Mickey Mouse didn’t always wear white gloves, Parade reports. When he debuted on screen in “Steamboat Willie” on November 18, 1928, he was gloveless. And he remained so until 1929's “The Opry House” when he finally put them on. Walt Disney believed the gloves made the Mouse look “more human.” Plus, they made hands easier to draw because they helped in distinguishing his hands from other black parts of his body or background. Maggie Thompson, retired senior editor of the defunct Comics Buyer’s Guide, is selling by auction portions of the comic book collection she and her husband Don amassed together over 50 years of collecting. About 500 pieces will go on Heritage Auction’s block over the next few months. Nothing in the category of Action Comics No.1, but a number of rare items still—the first issue of The Incredible Hulk, for example, and No.83 of The Avengers, featuring the first appearance of Thor. Thompson and her co-conspirators wouldn’t be surprised, saith the Associated Press, if the sale totals $1 million or more. “It’s rare to find books from such a respected collector and in such good condition,” said J.C. Vaughn, vice prez of publishing for Gemstone.

BANNED BY APPLE Floated Over the Rancid Raves Transom via CBLDF’s Website Image’s Sex Criminals No.2 has been banned from iOS comic apps, but not from iBooks, according to the publisher and the book’s creators, Matt Fraction and Chip Zdarsky. The Apple explanation was cryptic: "We found that one or more of your In-App Purchases contains content that many audiences would find objectionable, which is not in compliance with the App Store Review Guidelines." Image Publisher Eric Stephenson, in a joint interview with Fraction, Zdarsky, and the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, explained that the book was first delayed for an extended review by Apple, then banned completely. Zdarsky noted that since no indication of what content Apple found objectionable was provided, there was no way to change the book to make it acceptable. "Heck, if they were specific about the problem, we’d at least have a chance to put a black bar over something if inclined," Zdarsky told the CBLDF. "But then it looks like censorship, whereas a full banning somehow evades those kinds of optics. My mind reels." Not only was there inconsistency between different Apple stores. Stephenson noted the inconsistencies in Apple’s decision: "I mean, first off—there’s not a lot of difference between the content in issue one and issue two, but the one thing comiXology mentioned was that it may be—and they were just guessing here—because of the floating semen in issue two," he said. "But then, if that’s the tipping point... Isn’t ‘Something About Mary’ available on the iTunes store? Because I’m pretty sure that has a fairly memorable scene involving Cameron Diaz running a handful of semen through her hair thinking it’s hair gel. And there’s an episode of Girls where a guy ejaculates on Lena Dunham’s chest and you can get that on there as well, so... It’s tame content by comparison, and on top of that, the notorious Saga No.12—that’s still available on both the iBookstore and through the comiXology app. There’s no real standard, and it’s just kind of inconsistent and hypocritical." As if to confirm Stephenson’s opinion, Apple banned No.3 of the title for undisclosed violations of decorum, I suppose; and then, just to round it all of and achieve a consistency not evident yet, Apple retroactively banned No.1, too. All aboard now.

RCH

fitnut: I picked

up both copies of the title, driven—inexplicably, you probably think—by the

title and by the cover art. As a society, we’ve known “sex sells” since just

shortly before Adam and Eve got booted out of Eden, and comic books,

particularly superhero comics with superwimmin cavorting around in skin-tight

skivvies, have always been subliminally trafficking in sex, but it all went The “crime” involved herein seems related to the teenage heroine’s discovery of sex and its attendant pleasures and problems. Hardly scandalous in this day and age. I wouldn’t be surprised to find the series in use in schools in sex education classes. Incidentally, I don’t think the floating seman in No.2 is all that obvious. I thought it was a printing error.

Hallowe’en Comicfest A friend sent us a packet of Hallowe’en Comicfest comic books to give out on Hallowe’en to passing trickertreaters. I suspect most of the kids were simply agog at getting something more substantial than just candy (although we gave 'em all candy too). One kid was overheard saying, as he walked off our porch, "This is the best place ever!" I doubt that the candy we gave him inspired that praise; it was, surely, the comic book. We ran out—gave out probably 50 comics; and one kid, who somehow failed to get a comic, came back for one, but we'd just given out the last one, and he was visibly disappointed. Otherwise, we experienced no landslide reactions. Although I'm sure there were some later, among their friends.

STANLEY AWARDS IN AUSTRALIA Plucked Verbatim from the ACA Website Whilst most gala awards nights glitter and sparkle, October 26th Saturday night’s Stanley Awards for the Australian Cartoonists Association was festooned in lavish inks as Australia’s premier cartoonists gathered to celebrate not only their craft but an incredible year in Australian politics. With so much quality fodder from politics left and right, cartoonists were almost buckling under the weight of gags. “There’s been so much choice, we’ve actually been discarding high quality jokes in favour of better ones,” laughed Peter Broelman, a freelance editorial cartoonist and previous winner of Cartoonist of the Year. “We’ve been like kids in a candy store all year long.” Picking

up the awards were some of Australia’s best loved cartoonists including David

Rowe for Best Caricaturist, Glen le Lievre for Best Single Gag

Cartoonist, Gary Clark for Best Comic Strip and Mark Knight for

Best Editorial/Political Cartoonist. However, Anton Emdin scooped the

pool with Best Comic Book Artist, Best Illustrator and the coveted Gold Stanley

for Cartoonist of the Year. It is the second Gold Stanley for Emdin, having

previously won it in 2011. [Here, at your eye’s elbow, is a random sample of

Emdin’s work.—RCH] The Jim Russell Award for contribution to Australian cartooning was presented to Russ Radcliffe, commissioning editor at Scribe, for a decade of “Best Australian Political Cartoons” and a host of other political cartoon compilations. Gary Clark was also presented with a special trophy recognising his remarkable achievement of producing 10,000 Swamp daily comic strips.

History of The Stanleys In the early 1920s, leading cartoonists participated in the Artists’ Ball. This was an annual bohemian revel held at the Sydney Town Hall. When the revelry grew so boisterous for the more timid and elite fine artists that it was temporarily abandoned, the cartoonists took up the reins and for the next 30 years or so, continued to stage their own Black and White Artists Ball. Out of these shindigs the Club grew. Named the Sydney Black and White Artists’ Club, its membership included every famous cartoonist in Sydney, such as Stan Cross, Jim Bancks, Syd Nicholls, George Finey and so many others. However, realizing that there were numbers of newspaper cartoonists employed in other states and in country areas, the Sydney group decided it was time to expand their membership and activities. The name was changed to the Australian Black and White Artists’ Club and the membership grew to more than 100 members. In 1984, the membership had grown to nearly 400, and it was decided by the national committee that it was time they had awards to be presented to winners in various categories and that an annual function should be held for the presentations. In early 1985 the Awards Committee approached Trevor Kennedy, then editor-in-chief of The Bulletin, to provide exclusive sponsorship for a series of annual awards for cartoonists and other newspaper and magagazine artists. The Bulletin agreed to the sponsorship and named the event “The Bulletin Black and White Artists’ Awards” and the tradition began. Samples of members’ work was circulated to all members in the club in the form of the “voting book” and secret balloting by members for artists in six categories was conducted. The votes were forwarded anonymously to Peat Marwick and Mitchell, a leading firm of accountants that provided the names of the winners for the night

Fascinating Footnit. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com/comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

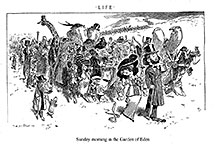

BILLY IRELAND’S GRAND OPENING Sullivant Hall on the eastern edge of the Ohio State University campus in Columbus, Ohio, could have been named after T.S. Sullivant. But it isn’t. Sullivant was the pioneering cartoonist whose pictorial hilarities depicting Biblical characters and cave men and anthropomorphic jungle animals imbued the old humor magazines Life and Judge with comical distinction from the 1890s to the 1920s.

So it would be a fitting tribute to his cartooning genius if

the building that now houses the world’s largest archive of comics art and

cartooning history bore his name. Alas, whoever Sullivant Hall is named for, it

is not the cartoonist. Rather, it bears the name of some other long forgotten

but no doubt deservedly neglected local dignitary. Sullivant Hall, whatever the

accomplishments of its namesake, came to life over the weekend of November

15-17 for the Grand Opening of the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum. The formal ribbon-cutting ceremony transpired at Sullivant Hall on Friday, November 15, at 6:30 p.m. The evening continued with a “conversation” between two OSU graduates now professional cartoonists, Jeff Smith and Paul Pope, in nearby Mershon Auditorium. The opening event was bookended by the Festival of Cartoon Art, featuring talks by cartoonists on their work and on cartooning generally on Saturday and Sunday and, on Thursday and Friday, the “academic con,” offering two dozen 15-minute paper readings by scholars of the medium. Cartoonists making presentations during the Festival included Matt Bors, Eddie Campbell, Brian Walker, Stephan Pastis, Patrick McDonnell, Hilary Price, Dylan Meconis, Brian Basset, and Kazu Kibuishi. The BICL&M began as a special collection of the OSU Library in 1977 when Milton Caniff donated to his alma mater his papers, files and much of the original art of Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon. At first called the Milton Caniff Research Room, the collection was housed in two small rooms of the old Journalism building: a reading room and an adjoining archival (storage) room. A third converted classroom was added later. I began my researches for the Caniff biography in these rooms. In 1984, Will Eisner donated materials documenting his career in comic books, instructional comics, and graphic novels. Caswell once recalled how the Eisner collection found its way to the Cartoon Library: she picked up the phone and a voice at the other end said, “Will Eisner is moving to Florida and thinking of throwing away a lot of stuff. Would you like to have it instead?” The same year, Toni Mendez, a licensing agent who represented cartoonists (notably among them, Caniff and B. Kliban), donated her papers. And in 1986, Walt Kelly’s widow donated Pogo papers and other materials related to Kelly’s tenure as president of the National Cartoonists Society. NCS has established its archives in the Cartoon Library, as has the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists. As more cartoonists donated their papers, the collection grew and soon needed more space. The first move was in 1990 to the Wexner Center for the Arts, a modern building at the High Street boundary of the campus, where the comics stuff was consigned to a basement cavern. While languishing there, the collection was increased in 1998 when Bill Blackbeard donated the holdings of his San Francisco Academy of Comic Art; at 75 tons, it’s the largest heap of newspaper comics strip tear sheets and clippings in the world. In 2000, Mort Walker donated the 200,000 original cartoons of his sadly defunct International Museum of Cartoon Art, which he had founded and nurtured and funded since 1974. The next move was the last—from 6,800 square feet to 30,000, from the Wexner Center to Sullivant Hall, a decaying facility that was gutted and extensively re-modeled to hold the BICL&M. The remodeling was funded to a great extent by two lavish donations. The largest was $7 million, donated in 2009 by the Elizabeth Ireland Graves Foundation in honor of Billy Ireland (hence, the present name of the Library & Museum); next came $3.5 million from the Charles M. Schulz Estate, $2.5 million of which matched donations from individuals and institutions all across the country and around the world. The Cartoon Library bore many names over the years, most of them laughably cumbersome as the University sought to encumber the facility with a name that described its holdings. Until 2009, the collection included a hodge-podge of visual materials, beginning at the time of Caniff’s donation with paintings, photographs, tear sheets, and book and magazine articles tracing the career of another OSU alumnus, famed magazine illustrator Jon Whitcomb. Thereafter, the collection attracted other materials of a kindred sort, prompting the name Library for Communication and Graphic Arts—a name that avoided the word cartoon as if the University regarded it as a vaguely suspicious pretender to the intellectual and artistic status of collegiate life. When the collection was moved to the Wexner Center, the moguls of the Ivory Tower finally surrendered, calling it the Cartoon, Graphic and Photographic Arts Research Library—shortened, in 1997, to the mercifully accurate Cartoon Research Library. In 2009, all the non-cartoon holdings were transferred to other special collections in the University’s library departments. The Milton Caniff Research Room was long ago retired as a name for the operation although I like to believe that the bronze plaque bearing that inscription exists somewhere on the premises. That Caniff should be subsumed by Ireland is a somehow serendipitous outcome. Ireland

was a beloved cartoonist on the staff of the Columbus Dispatch for

nearly 40 years until his death in 1935. During his long career, he poked fun

at politicians and advocated environmental causes and ridiculed the Ku Klux

Klan while also commenting on the fads and foibles of Columbus in his weekly

summary of news and views, The Passing Show, the logo of which changed

picturesquely to suit the seasons and other stray topics that wandered across

Ireland’s drawingboard. Ireland usually depicted himself as the “janitor” of

the feature, but whether he appeared or not, his signature dingbat was an Irish

shamrock, and it was always in evidence. Ireland

was already a local institution known nationally when Caniff came to the city

to enroll at OSU in 1925. Caniff needed a job in order to pay his way, and he

applied to Ireland, who gave him a try-out assignment, saying if the youth

could produce something that would “make me jump,” he’d have a job. Caniff drew

the accompanying comic strip—and got the job. The

BICL&M move to Sullivant Hall is commemorated in photographs at http://library.osu.edu/blogs/

Lucy Shelton Caswell Telling Tales about the Founding Curator of the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum I HAVE KNOWN LUCY CASWELL as a professional colleague for more than 30 years. It seems strange to me to realize the length of this relationship: most of the people I’ve known for three decades, I’ve known since we were children together, and Lucy and I were never children together. I met her in 1982 at the 75th birthday party held at Ohio State University for Milton Caniff, the gift of whose papers created much of the foundation for what is now called the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum. At the time, I recognized that Lucy was an exceedingly nice person—too nice, I thought, to have allowed herself to fall in with such a disreputable gaggle of people as cartoonists almost inevitably are. Nothing much has happened in the years since to change my mind. I still believe all of that—she’s still too nice, and cartoonists still gaggle disreputably. But along the way, I’ve learned more about Lucy. I am a chronicler of cartooning; and she is the keeper of the pertinent trove. It was inevitable, given the mission of the Cartoon Library and my obsessions, that we would spend more time together than was possible at the Caniff birthday festivities. Some years later, I returned to OSU to became one of the first persons to make extensive use of the holdings of the Cartoon Library in assembling material for the “definitive biography” that Caniff had invited me to write. I spent a week pawing through the papers that Caniff had bequeathed to the University. I came back on other occasions to continue the research, but that first week was the most memorable. In those years of the infancy of the Cartoon Library, it was housed in three small rooms in the old Journalism building. Collectively, they were called, then, the Milton Caniff Research Room because the holdings were mostly his papers. Researchers like me were supposed to do their work in the first of the rooms. In the other two rooms, the holdings of the Library were archived. As soon as I unpacked my pencil and paper in that first room, Lucy explained the protocol. She presented me with a loose-leaf notebook, the pages of which listed the Caniff materials available. I was to pick which of these hundreds of items I wanted to inspect and read, and, Luther, Lucy’s assistant, would disappear into the two-room bowels of the Library, find the item I’d asked for, and bring it out to me, so I could read it seated comfortably at the table in the front room. This system, for all its admirable aspects, soon revealed an unfortunate drawback. The catalogue notations on the pages of the loose-leaf notebook were, of necessity, cryptic rather than descriptive. And so when Luther brought me the first item I requested, I knew at a glance that it wasn’t, quite, what I’d expected. So Luther took it back while I picked another item, and then he disappeared again to retrieve it for me. This next item, like the first, was not what I thought it would be: it didn’t contain the sort of information I was looking for. So I tried again. Luther disappeared again. Again, no luck. This procedure, due, doubtless, to my own lack of perspicacity and experience as a researcher, was simply not working. At this rate, I would wear out my thumb and Luther’s his shoe leather long before I discovered anything useful for the Caniff biography. Lucy, bless her, realized the fruitlessness of this endeavor long before I did. And she immediately took remedial action. She told me to take my pad and pencil and the catalogue notebook into the second of the three rooms, where there was a work table I could sit at. There, I was closer to the material I wanted to inspect—namely, Caniff’s records, syndicate proofs of his comic strips and some original art, and, most important, his correspondence, which, filed by year, would be immediately behind me in a dozen or more filing cabinets that had been transported, whole, from his studio. Lucy then invited me to help myself to the files, provided I would be exceedingly careful to return each of the files to its appropriate place in the filing cabinet when I’d finished with them. I was happy to agree. And Lucy started holding her breath. I hasten to say that nothing this informal prevails at the Library these days. Today’s researchers, among whom I am still numbered, adhere religiously to accepted protocols that are designed to preserve the material in pristine condition while also assisting the researcher. Today, we have to wear white cotton gloves to handle any of the materials we want to inspect. But we still start with catalogues—i.e., looseleaf notebooks. I suspect that had the Grand High Director of Ohio State University Libraries known that Lucy had let me into the inner sanctum sanctorum and permitted me to rummage through the files willy nilly, Lucy might not have lasted as curator long enough to see Billy Ireland installed as the Library’s name. But those were the early days of the Cartoon Library, and all of us were sort of feeling our way. I learned, and Lucy learned. And the Cartoon Library grew and grew until it is now the world’s foremost research facility in the history and art of cartooning. And I doubt that it would have grown to such impressive dimensions if Lucy had not been the kind of curator she was. There is an entirely practical reason for such special collections as this one, and, as Lucy demonstrated in the Milton Caniff Research Room during my first visit there, she knew the practicalities and could adapt to serve them. The practicalities have no doubt changed greatly as the collection grew, and perhaps such solutions as Lucy found in those early days would no longer apply (or be acceptable) now. But Lucy can find a way. She found a way to assist me in my baptism as a researcher, and she found a way to bring to publication the biography that I finally wrote about the man whose papers started this special collection, a man whose talent and dedication shaped the newspaper comic strip medium, and the cartooning profession, in ways few others have. And I have no doubt that Lucy has found other ways to achieve other objectives over the last 36 years. She is, after all, an expert in practicality. She is also dedicated as few are to the preservation of as much of the history and artifacts of cartooning as possible. But it was her practicality that impressed me 31 years ago, and continues to impress me. And she is also—above and beyond dedication and practicality—too nice to have fallen in with such a disreputable lot as cartoonists.

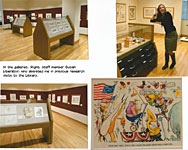

The Cathedral of Cartooning Arts The Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum is undeniably the largest facility of its kind. “We have the largest collection of cartoon and comic art in the world,” said Jenny Robb, the present curator of the Museum (and a former student and assistant of Lucy Caswell’s). “In our old space we were hidden underground and didn’t have proper exhibition space to show the artworks. So the goal here is to be more visible and provide more accessibility to our collections.” The collections are impressive: something in the neighborhood of 300,000 pieces of original art, 45,000 books on cartoonists and cartooning, 67,000 serial and comic book titles, and 2.5 million comic strip clippings and newspaper pages. “We want to be the center of the comics universe,” said Robb. At the center of that universe, Sullivant Hall stands like a cathedral of the cartooning arts. And I am reminded of another cathedral—namely, St. Paul’s, in London. In Sullivant Hall, I find an echo from St. Paul’s. St. Paul’s was the architectural masterpiece of Christopher Wren, who, as Surveyor of Works for Charles II, supervised the design and building of more than 50 of London’s churches after the Great Fire of 1666 destroyed two-thirds of the city. Wren-designed churches set one of modern architecture’s distinctive styles. Among his more spectacular achievements was St. Paul’s. Wren is buried in the crypt of St. Paul’s, and on his tomb, in Latin, are these words: If you seek his monument, look around you. We might say the same of Lucy S. Caswell and the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum.

Academic Pre-Con The Grand Opening Festival of Cartoon Art was prefaced by two days of paper reading. The papers and their readers were mostly college professorial types, and they read papers rather than speaking from notes because they’d all been threatened with early extermination if they exceeded an 18-minute time limit imposed upon each of them by the event’s design, which was organized into 75-minute clusters of four paper presentations each. After years of experimentation, it has been determined that the best way to assure that your presentation does not violate the decorum of the time limit is to write out what you wish to say, then read it aloud and time yourself. And do that over and over again until you are certain that your presentation can be made in 18 minutes. It’s all perfectly logical, but the result, too often, is monumentally boring: people invariably read too fast (in order to get done within the time allowed), and, to make sure they waste no moment by losing their place in the text, they never raise their heads but stare fixedly at their script held before their eyes. Academic presentations are therefore distinguished by a parade of apparitions, each of whom bends over a fistful of papers, muttering into the papers as rapidly as they can. The breathtaking dulness of this procedure is exacerbated in my case because, being half deaf, I don’t hear much of what they’re muttering at breakneck speed. (No: I don’t know which half is deaf, which compounds the problem.) Reading from notes always results in a more lively presentation—but, alas, it risks sabotaging the whole proceedings by going beyond the time limits. Ergo, paper reading prevails. The

two-day extravaganza was organized and operated by the energetic Jared

Gardner of Ohio State U., who never rested. For two days, he kept an

attentive eye on the operation, leaping up to the audio-visual console to help

the inept manage their visuals or to adjust microphones. No one could ask for a

better host and helper—or one more knowledgeable. I’ve posted the agenda

nearby, so you can, should you be so obsessed, print it out and read it,

thereby gaining some idea of the scope and metatextuality of it all. Since I heard only about every fourth word, this report is necessarily (sadly) skimpy. A few moments stand out, though, even though I barely understood them. I was second to the mic with a presentation about Wally Wallgren, the World War I soldier cartoonist who gained fame during the War only to vanish afterwards. You can read about Wally in Harv’s Hindsight for February 2009; that’s essentially the paper I presented, reading parts, ad-libbing others (a somewhat more elaborate version is a chapter in my book, Insider Histories of Cartooning: Little Known Comics Origins and Famous Cartoonists You Never Heard Of, which will appear about a year from now). Steve Thompson, Kelly fanaddic extraordinaire, showed a selection of Walt Kelly’s political cartoons. Corey Creekmur (University of Iowa) discussed the prolix problem of “continuity” in comic books, how the impulse to knit together all the possible worlds of superheroicism folds in on itself and eventually suffocates story and character. Among the things he said: “If I want to talk about Superman, what’s my responsibility as a critic? One panel? One page? One issue of the comic book? The run of issues produced by a single creator? (Writer or artist?) The full run of the title—including spin-offs?” Roy Cook (University of Minnesota) demonstrated as only “intertextual metafiction” can that Snoopy created Batman. Or is it vice versa? Matthew Smith (Wittenberg Univesity) talked about comics in the classroom, deploying among his visual aids a picture of an Ivory Tower that had been drawn from two perspectives at once—an impossibility that Smith didn’t notice at first. And it was Damian Duffy (a cohort from the University of Illinois) who made the telling observation that television and movies control time for a perceiver, but comics allow the perceiver to set his own pace. And James Sturm (who runs the Center for Cartoon Studies in Vermont) posed the practical fallacy: what do you do with a history major? (It’s a fallacy because it doesn’t matter. Major in history if you like history. Then go off and teach it or do something entirely different. It was Garrison Keillor who established himself as The Expert on such matters when he said: “Being an English major in college prepares you for impersonating authority.”) Andrew Funka (University of South Carolina at Sumter) read from letters exchanged between Will Eisner and Jack Katz as the latter was producing his monumental First Kingdom, speculating that Eisner was encouraged to pursue the “graphic novel” form—i.e., a serious literary work in comics form—by Katz’s example. John

Jennings, another cohort from the U. of Illinois (now at SUN Buffalo), talked

about Black Kirby, a fictional personage he and his graduate student, Stacey

Robinson, propounded, imagining an African-American comic book artist who

produces racial messages of diversity and power in the manner of Jack Kirby.

The results of their imagining are collected in a self-published book entitled Black

Kirby. From the back cover of the book: “Black Kirby functions as a highly syncretic mythopoetic framework by appropriating Jack Kirby’s bold forms and revolutionary ideas combined with themes centered around AfroFuturism, social justice, Black history, media criticism, science fiction, magical realism, and the utilization of Hip Hop culture as a methodology for creating visual expression. ... In a sense, Black Kirby appropriates the gallery as a conceptual ‘crossroads’ to examine identity as a socialized concept and to show the commonalities between Black comics creators and Jewish comics creators and how they both utilize the medium of comics as space of resistance. The duo attempts to re-mediate ‘blackness’ and other identity contexts as ‘sublime technologies’ that produce experiences that sometime limit human progress and possibility.” Because the book is a “gallery,” there are no stories in the volume; just images, usually one-pagers, each of extraordinary visual power (even rage)—all evoking Jack Kirby’s most powerful imagery. Aaron Kashtan (Georgia Institute of Technology) broke into a thicket of terminology, all subsumed under “transmediality” (works that deploy themselves over more than one medium?), which inaugurated a flotilla of brand new pedagogical polysyllables, the most spectacular of which is doubtless “affordance,” the meaning of which is not apparent from any context in which it appeared. The general drift of two days of papers seemed to descend from factual history to wildly speculative theory, from reality to fantasy (or, as someone kept saying, “VR,” “virtual reality”), culminating in the “keynote” (at the end) by Henry Jenkins, who is the Provost’s Professor of Communication, Journalism and Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California Annenberg School for Communication and the School of Cinematic Arts. With that pedigree and a book entitled Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide, he was the perfect choice to end in a crescendo of foggy intermedia textuality and affordance, the seeming destination of the two-day program, but he fooled us all, illustrating his talk by parsing a Yellow Kid page. Nicely done. Here is a selection of my notes—mostly, as you see, attempts to caricature the presenters.

The Festival Itself The Festival got underway Friday evening with the formal ribbon-cutting at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum, as depicted in the adjacent photos (all, alas, taken from a great distance with a zoom lens that did not, sadly, retain any visual detail to any observable extent).

After the ribbon was torn asunder, we all repaired across the mall to listen to Jeff Smith and Paul Pope, two OSU alumni who had experienced the Cartoon Library in various of its manifestations over the years. They appeared in rumpled casual attire, mostly black, with matching mussed up hair. I couldn’t hear much. On Saturday, Lucy Caswell was presented with the Segar Award from King Features, a statuette of E.C. Segar’s Popeye, and then commenced a parade of cartoonists giving hour-long commentaries on projected visuals from their works: Herblock Prize winner Matt Bors (editoons and the graphic novel War Is Boring), Eddie Campbell (From Hell and numerous other graphic novels), and Stephan Pastis (Pearls Before Swine) on Saturday; Brian Basset (Red and Rover) and Kazu Kibuiski (Amulet) on Sunday. Two of the Hernandez Bros, Jaime and Gilbert, appeared Saturday evening “in conversation” a la Smith and Pope, but since I hadn’t heard anything Smith and Pope said the evening before, I stayed away (and missed one of the Festivals comedic highlights, I gather from Dan Yezbick’s report, below).

The Festival’s concluding event on Saturday afternoon was a screening of the film “Stripped,” cartoonist Dave Kellett’s documentary about the newspaper comic strip industry. Started five years ago and now nearing a final stage with the help of filmmaker Fred Schroeder, the made-for-television program assesses of the current state of the art and its future. Kellett, who is a webcomics enthusiast and practitioner, admits that he began the project expecting to record the demise of newspaper comics; but as he assembled interviews with cartoonists, he changed his mind: the film now ends on a somewhat more optimistic note—adapt or die, with history showing that adaptation has been part of the medium’s history. The film itself is fast-moving—quick images of comic characters and strips, a sort of visual collage, followed by short sentence excerpts from the interviewed cartoonists on screen, then more collage. Although divided into “chapters” (“The Golden Age,” “The Creative Process,” and “The Crisis”), some of the chapters don’t go very far—“The Golden Age,” for instance, scarcely covers the ground. “The Creative Process” is better: it offers the most lengthy excerpts from cartoonist interviews (still not very long, though). In short, the film is more dazzle than deliberation. It conveys an impression rather than offering an analysis. I’m quoted twice on camera. Once I say only a single word, and I wasn’t quick enough to catch what it was. On the other occasion, I utter this profundity: “I don’t think web comics are the answer”(“comics historian” lettered beneath my picture). And that cryptic comment reveals the film’s most serious flaw. Why don’t I believe that web comics are the answer? What is the answer? Is there one? What’s the question? Throughout, the film is much the same: there’s little depth. Some of the interviews about the creative process are insightful, but there’s too little thought displayed in assessing the fate of the newspaper comic strip. It’s a subject that deserves—demands—in-depth examination and discussion. And Kellett provides very little of either. Otherwise, the film is skillfully done. Discussing a static artform, printed comic strips, Kellett and Schroeder compensate for the inherent lack of movement with quick cutting and flashing imagery. The flashing images go by quick—here and then gone. The film is copious rather than thoughtful.

The Crisis in the Newspaper Comic Strip Kingdom I’ve written briefly about this before, but every time I am confronted anew by yet another chorus of “comic strips are a dying artform,” I’m compelled to rush to the barricades again. To begin with, I don’t think comic strips are a dying artform; nor do I think newspapers are dying—the proposition upon which the death of comic strips is predicated. Why my stubborn failure to subscribe to a notion the rest of the world seems to endorse? To start near the root of the matter, the plight of metropolitan newspapers has precipitated visions of the death of comic strips. Newspapers are in financial trouble, and because they are the platform for comic strips, comic strips must also be in trouble. And there’s some evidence to support both contentions. Some but not enough. First, consider the source of the stories about the death of newspapers. That news is lofted mostly by large, metropolitan newspapers. Small city newspapers (dailies and weeklies) aren’t complaining. Why not? Because they’re not in the kind of trouble big city papers are in. They still get sufficient revenue from advertising: local businesses have no place else to advertise. In big cities with hordes of national chain stores (rather than small town Mom ‘n’ Pop establishments), businesses advertise nationally via television. And classified advertising has all but disappeared. Finally, to drive the nail in the coffin, readership is evaporating. The most populous newspaper reading demographic is the 55-to-75-year-old category. And newspapers appear too busy wringing their hands at the loss of the 18-35 age group to find ways to exploit the other demographic. I’ll come back to this in a trice. But before I leave small city newspapers, their apparent fiscal health is small comfort to us: few of them run comic strips. Their continued existence serves simply to make my point: the newspapers that are in trouble financially in this country are big city papers. Still considering the source of all the dire information: until classified advertising disappeared into the Internet, newspapers generally—and particularly those in big cities—had profit margins of roughly 30%. No other American business had profits so bountiful. And in the flush years before, say, 1999, newspapers did two things that proved disastrous. First, they modernized their printing plants and built new offices and expanded their circulation areas—all things underwritten by that robust 30% profit. When the profit margin dropped (due to loss of advertising and readers to the Internet), the papers were left with the huge debts (or circulation obligations) they’d rung up during their financial heydays. And their revenue was no longer great enough to service their debts handily. The second disaster that newspapers made for themselves is that they went public: they became corporations with shareholders whose avaricious appetite for more and more income was virtually insatiable. Newspapers, then—mostly the big city papers—were caught in a contradictory conundrum: dwindling income could not satisfy the shareholders’ growing demand for greater and greater profit. The first reaction was to reduce expenses—cut staff, shrink the circulation area. A secondary response was to shift content to the Internet, creating digital editions to attract the young readers who don’t buy print papers anymore. This maneuver seems doomed since the revenue from Internet subscribers is never likely to make up for the loss of print subscribers and advertising revenue. But papers are doing it anyhow. Comics are being dragged along. Some newspapers have a considerable roster of comic strips in their online editions. Those are less expensive. In the print edition, some papers have cut back on the number of strips they run, compensating with the online roster. The Denver Post dropped both Classic Peanuts and Doonesbury last year (I can’t think of two strips that seemed more immune to such cost-cutting moves, but there you are) but both are offered in the online edition for which the Post pays fees that are minuscule compared to the fees for publishing strips in print. And last month, the Post “streamlined” its Sunday funnies: they managed to eliminate two pages of the comics section without dropping any of the strips themselves. The paper reduced the section to four pages by shrinking the size of most strips and by deleting the “splash panels” that carry the strips’ titles. In announcing this move, the editor of the Post tried to make his readers feel better by saying that “some newspapers” have discontinued their comics altogether. So we should feel good that we have any at all, even if they’re smaller than before. Phooey, I said. And I wrote back: “I’m gratified to know that you still think comics are important enough to your readers to tell us what caused you to shrink (another word for ‘streamline’) the Sunday funnies. But when you say ‘some’ newspapers have discontinued their comics altogether, I think someone’s been blowing smoke your way. Still, to give you the benefit of the doubt, can you name, say, three metropolitan newspapers of the Post’s size or larger that have discontinued their comics? I say ‘three’ but that’s really on the short side of ‘some’ if we assume that a ‘few’ is three or four and ‘some’ is more than a ‘few.’ So—name three. Heck, name two.” The editor has yet to reply. Because he lied. I’ve checked with three of the major feature syndicates distributing comics. None of them report any metropolitan newspapers that have discontinued the comics altogether. I don’t mean to say that newspapers are not in financial straits. They are. But they’re not in as much trouble as they’d have us believe. They’ve lost that abundant 30% profit margin, and they are understandably weeping and wailing over the loss, but I’m pretty sure they’re still making a profit. Not 30% anymore, but a profit nonetheless. If they weren’t making a profit, they’d be out of business. So they’re getting used to smaller profits even if they don’t like it much and complain about it endlessly. The Denver Post is not as poor as it wants us to believe it is. A few years ago, it renegotiated the largest of its debts by making those to whom it owed the most money partners in the business. Other metropolitan newspapers have survived by similar maneuvers. About four years ago, Time magazine predicted the deaths of ten major newspapers in the country; all ten are still publishing. They’ve found a way—as all capitalists do. Still, it’s true, irrefutable actually, that newspapers are in financial trouble (largely of their own making, as I said) and comic strips (and staff editorial cartoonists) are in trouble as a direct consequence. Kellett’s movie lists 166 newspapers that have died since 2008. Catastrophic, no question. Until we examine the statistic he pulls from. The figure 166 actually includes papers that have given up their print editions as well as those that have ceased publication altogether; digital newspapers are not, technically, dead. The date cited is significant: 2008 is when the country’s economy started tanking. Lots of businesses went under. Newspapers were not alone, and the death of so many says more about the economy generally than it does about the newspaper business particularly. Moreover, the number of papers expiring peaked at the onset of the Great Recession, and the annual total of dying papers has been growing less and less as the years unravel. The newspaper dilemma is still serious, but it’s not quite as dire as Kellett wants us to believe. Meanwhile, there are about 1,400 newspapers still publishing, many in small towns and apparently thriving because they didn’t invest their profits extravagantly in the halcyon days of the last century when everyone in the newspaper business was going to the bank pretty often. We, the general public, like disaster stories, and so we have fastened on the death of newspapers as a particularly juicy one. But perhaps we ought to be more circumspect about our entertainments: some of them are fiction. Those who predict the end of both newspapers and their comic strips have been seduced into that belief by the seemingly sensible conviction that change is inevitable and that change implies the destruction of whatever it takes the place of. These disciples of change are ignoring an overriding principle in a capitalist society: money rules, and the profit motive decides everything. My take on the present predicament is that the shareholders who are demanding greater and greater profits from newspapers that suffer dropping revenues will eventually lose patience and bail out, selling their shares at a loss if need be just to escape a situation that is no longer making bales of money for them. And eventually, newspaper ownership will fall once again into the hands of private persons, billionaires with nothing to do with their money but have fun. And running a newspaper for fun and profit is the traditional name of the game. Individual owners will revert to the purposes individual newspaper owners have always espoused: they’ll opt for journalism again, not investment and profit, and they’ll practice journalism for all the good and noble reasons it has always been practiced—to inform the public and to garner power (political and financial) for the newspaper owner. This sea change is already setting in. Two large metropolitan dailies—the Washington Post and the Boston Globe—have been acquired by individual billionaire owners. In seeking to regain lost power, newspaper owners will probably continue digital editions, but they’ll also refurbish print edition tactics. If I were one of those owners, I’d go after the older demographic that constitutes most of the present readership of newspapers. That population has more discretionary income than the younger (and supposedly wealthier) demographic. The older generation no longer has the cost of raising and educating children. They want to go on trips and buy expensive automobiles. Newspapers ought to be appealing to those interests. Forget about the young folks: they’ll grow into older readers soon enough, and if a newspaper plays its cards right, it’ll get those erstwhile young and carefree persons when they’re ripe. Finally, in appealing to an older readership, newspapers will start publishing comic strips large enough for old guys like me to be able to read the words in the speech balloons. And so comic strips aren’t doomed at all: they seem poised on the cusp of another Golden Age. The newspapers that provide their platform are not dying after all; and the comics—one of the two or three most popular things people find in newspapers—will surely go on as long as those newspapers continue to publish, which, I stubbornly contend and hope to have demonstrated, will be for some time yet. And every three years hereafter, we’ll have another celebration of the living, thriving arts of cartooning at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum. (Love the ampersand. Nicely unpedagogical. Subliminal insurgency in the ivied halls of otherwise stuffy academe.)

Feetnoot Conversations between formal presentations are as meaty a part of the OSU Cartoon Art Festival as the presentations. During one of the breaks, I met Nancy Silberkleit, the estranged co-publisher of Archie Comics, whose adventures I’ve rehearsed here from time to time. Since

her fate is in the hands of numerous lawyers, she didn’t want me to report any

of our conversation, but perhaps it goes even without saying that none of Here’s the cover of a comic book she’s produced to show teens how to triumph over bullying. Stan Goldberg did the pencilling. See Opus 317 for our report on her anti-bullying crusade.

THE ULTIMATES EDITION What Marvel Might Market as the OSU Cartoon Arts Festival Dan Yezbick’s Report on the Grand Opening Weekend Top Eleven (Ten is Boring) Non-Academic Amusements and Epiphanies of the Festival—: 11. Watching my former student, Damian Duffy, wow the room with his zippy, trippy, oh-so-pithy lollapalooza of a presentation on the current crossroads of virtual comics mediation. 10. John Jennings' cutting edge Afro-Futurism presentation on the Black Kirby Project amiably shames everyone in the Schulz auditorium for not encouraging all the other "African American Male Comics Scholars" in the room. (There were none.) 9. Robert Harvey versus the Egg Timer during his magnificent presentation on the lost cartoonist, Wally Wallgren. Sometimes the undercards really are better than the title fight! 8. Henry Jenkins' powerful keynote testament to virtual, animated scholarship on the Hogan's Alley dogcatcher page finally lets that poor flailing urchin in the background finish his fall from the fire escape. He'd been hanging there terrified for more than 100 years! 7. Los Brothers Hernandez tell the entire congregated enclave that they really owe it all to their mother's love of comics and drawing, and how it weirded them out a bit when they discovered her oversized drawing of Superman staring through a magnifying glass. 6. Gilbert Hernandez takes the stage and immediately impersonates Paul Pope's shabby chic pose from the previous night's conversation. All further comedy in 2013 becomes superfluous. 5. Jeff Smith tells conference goers that all of the solid blacks in Bone and RASL were inked by brushes once owned by Milton Caniff, which he received as a gift while an OSU Undergrad from the great Lucy Shelton Caswell. 4. It is proven, that thanks to the paradoxical creative logic of self-reflexive fiction by Walt Simonson, Snoopy should probably be credited with the birth of Batman one "Dark and Stormy Night." 3. Close to 500 visitors, locals, and students gather in the heart of the OSU campus on a Saturday and not a one of them asks another about football scores. 2. I get Steve Pastis to sign my son's beloved copy of Timmy Failure. I am second in the line for fear of disappointing mine own offspring. The first person in line is an elderly lady decked out in OSU gear with several Pearls Before Swine collections to get signed for her grandchildren. She asks if I will take a photo of Pastis in action with her in the background. When I agree to assist, she discovers that I went to Michigan and refuses to let me touch her camera. 1. Thanks to Brian Walker's exhibition [assembled from the Library’s holdings expressly for the Grand Opening], I relish a little alone time with original art by Carl Barks, Will Eisner, Winsor McCay, Gahan Wilson, and many, many more but the ultimate thrill is standing next to, in front of, behind, and at every other angle from Walt Kelly’s original artwork for Pogo's seminal Earth Day rallying strip, "We have met the Enemy, and He is Us." This image has been a part of my personal and professional life since my mother first showed it to me in grade school and explained how Pogo's endless fusion of scolding joy operated in her own childhood. Over the weekend, I also encountered Pogophiles of every imaginable age and interest, including a philosophy prof who had the famous lines tattooed on his forearm for his 40th birthday (even in the correct font!). Such are the joys and wonders of the past five days. My gratitude and geekitude to all involved!

QUOTES AND MOTS “Home is a place that when you go there, they have to take you in.”—Robert Frost “Beautiful young people are accidents of nature; but beautiful old people are works of art.”—Eleanor Roosevelt “You’re only young once, but you can stay immature indefinitely.”—Ogden Nash “They tell you that you’ll lose your mind when you grow older. What they don’t tell you is that you won’t miss it.”—Malcolm Cowley “If you give up smoking, drinking and sex, you don’t actually live longer; it just seems longer.”—Clement Freud

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy WE’RE

STRUGGLING with brevity this time and so include only the two cartoons you have

at the corner of your eye. And neither deals with the Great Issues of the Day.

(Which we’ll revisit next time, after giving Thanks.) The next cartoon is torn from newspaper headlines. Signe Wilkinson, editoonist at the Philadelphia Daily News, was robbed at gunpoint on Sunday, November 17. She records the experience in the accompanying cartoon, adding her typically acerbic interpretation of events: “Today’s toon is my first clearly autobiographical editorial cartoon. Held up at gunpoint on Sunday evening at 7 p.m. in my nice, safe neighborhood, the little perp made off with my 'purse' which was a canvas bag filled with pens, paper, and sketches for my comic strip, Family Tree. It put my schedule back but warmed my heart that I've given him the tools that could change his life. Of course, learning to use the pens takes longer than learning to shoot a gun.”

THE SON OF MOTS & QUOTES “There is no cure for birth and death save to enjoy the interval.”—George Santayana “There is so much good in the worst of us and so much bad in the best of us that I hesitate to draw the line when God has not.”—Unknown (via Gary George, friend of my youth and age), but attributed to Edward Hoch (one-time governor of Kansas, but denied by him), Abraham Lincoln, Robert Louis Stevenson and a few others, all of whom said it a little differently (if they said it at all). “Blessed are the cracked because the let in the light.”—A Nony Mous

THE FROTH ESTATE The Alleged News Institution Remembers the Kennedy Assassination I MISSED MOST OF THE KENNEDY PRESIDENCY. I went on active duty in the Navy in June 1960. Eisenhower was still President. Kennedy was elected that fall, and by then, I was in uniform. In the spring of 1961, I was assigned to the USS Saratoga, a giant aircraft carrier that toured the Mediterranean for months on end. I did two such tours, and when I got out, in mid-November 1963, JFK had only a few days to live. All of the magic of the Camelot Years passed by without my paying much attention: I was at sea, literally and figuratively, ignoring politics. Not by choice, exactly: we got news magazines a few weeks after they were published, so although we were aware of what was going on, vaguely, we weren’t steeped in the Kennedy mystique. So I wasn’t much into it. And it was over on November 22, 1963. As far as I was concerned, it never happened. Not that I was unaffected. I’d just returned from taking my mother on a trip to visit relatives that week, and my first awareness of the assassination was that Friday when we pulled up to the house and I got out and picked up the newspaper—headlines screamed. Kennedy was shot. The rest of the weekend, we spent watching it all unfold on tv. So I was there then. No longer at sea. But in the ensuing months, I missed (or dismissed) most of the folderol that unfolded with the convening of the Warren Commission and its subsequent findings. As far as I am concerned, Oswald killed Kennedy; no conspiracy. Just a nut case. The assumption was that Lee Harvey Oswald hated Kennedy. Or his policies. So I was surprised to see James Reston, Jr., taking up the matter again in USA Today of November 18. Oswald killed Kennedy and yet he admired Kennedy. How’d that happen? “The truth about Oswald’s motive lies in his psychology, not in his politics,” Reston writes. “There had to have been something deeply personal within Oswald’s emotional structure to animate the murderous rage That anger was directed not against President Kennedy but against Texas Governor John Connally” who was in the front seat of the limousine Kennedy and Jackie were riding in. “With Connally, not Kennedy, Oswald had had a personal grudge. It had to do with a change that was summarily made in his miliary discharge from honorable to, he thought, dishonorable, after his three years in the Marine Corps and his foray in the Soviet Union. “Oswald knew the change would be devastating to his ability to make a living once he returned to the U.S. And so he wrote a heart-felt appeal to Connally, then the secretary of the Navy [under which administration of the Marines fell], thinking a fellow Texan would be sympathetic. But Connally spurned the appeal in a classic bureaucratic brushoff. And the slight arrived in an envelope bearing the smiling face of Connally within a Texas star and hawking his campaign for governor of Texas. From February 1962 onward, Connally became the face of Oswald’s frustration. “Both to the Warren Commission in 19674 and the House Assassinations Committee in 1978, Oswald’s wife, Marina, testified that Connally, not Kennedy, was Oswald’s target on November 22, 1963.” And it’s taken me this long to become aware of this salient fact. Sad, eh? Why isn’t information about the Connally congeries bandied about in every discussion of the Kennedy assassination? Probably (just to engage in a little paranoia) because that would destroy the conspiracy theories to which we seem, as a nation, to be so thoroughly addicted. They hinge upon which all the conspiracy theories turn is that Oswald wanted to kill Kennedy. If he didn’t—if he really wanted to hit Connally—then all the conspiracy fantasies evaporate. And a good thing, too.

T-SHIRT WIT AND WISDOM Profundities That Can Be Found on People’s Chests Sometimes Life just sucks the jelly right out of your donut Boobs—proof that men can focus on two things at once! Fah Kin Ah Sum My Train of Thought Derailed: There were No Survivors You didn’t fall out of the Stupid Tree: you were dragged through the entire Dumbass Forest! When Work feels Overwhelming, remember that YOU ARE GOING TO DIE! I didn’t fart. That was a turd whistling for the right of way. Blink if you want me! Don’t grow up: it’s a trap! Remember when being stiff in the morning was a good thing?

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping I love this

stuff—when comic strips do “cross-overs,” recruiting into one strip the

characters from another. It’s risky, though: the interloper cannot be a

character from an obscure strip, so the cartoonists executing cross-overs have

to be careful to pick characters that are well know. In Blondie, probably the only risky cameo is Opal from Pickles. The rest—Beetle, Grimm, Popeye—are all virtually icons in American pop culture. The first of the two Mother Goose and Grimm strips is delightfully a propos the Monday gag. And Garfield is perhaps as recognizable as Mickey Mouse. More than Hello Kitty anyhow. In the next one, Grimm is doing an impersonation of Opie, the slobbering dog in Garfield. I love the allusion, but I’m not sure Opie’s drool is as notorious as Garfield’s dislike of Mondays. Still, good fun. In

the next batch of four strips, probably only Beetle Bailey is deploying

an image everyone will recognize. Still, for those of us with sheer penetrating acumen, such strips are a hoot.

READ AND RELISH Selections from Jen Campbell’s book, Weird Things Customers Say in Bookstores: Customer: I want to buy a book for my mother. She likes Danielle Steel. Bookseller: Here she is, under “S” for Steel. Customer: Well, I don’t know which ones she’s already read. Do you? Bookseller: ....

-oo0oo-

Customer: Where’s your true fiction section? -oo0oo-

Customer: I don’t know why she wants it,but my wife asked for a copy of The Dinosaur Cookbook. Bookseller: The Dinah Shore Cookbook? Customer: That must be it; I wondered what she was up to.

-oo0oo-

Customer: Do you arrange your books by color? I’m looking for a blue book.

-oo0oo-

Customer: Do you have that book about those people in that place with the thing?

-oo0oo-

Customer: What books could I get to make guests look at my bookshelf and think: “Wow, that guy’s intelligent”? -oo0oo-

Customer: Do you have Harry Potter book seven, part two? Bookseller: Book seven is just one volume. Customer: But the movie has two parts, so there must be a second book. They don’t just make movies from nothing!

BOOK MARQUEE Short Reviews This time under this heading, we explore several books the artwork of which is the reason for the reviews. We start with a couple older works and then get completely current—all the way, emphasizing the function of the pictures in their narratives—:

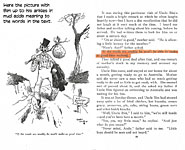

The Madam Paul Affair By Julie Doucet 88 7x9-inch pages, b/w; 2000 Drawn & Quarterly paperback, $7.95 new in 2000 ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED in French serially for 40 installments in the Montreal weekly ICI, the story seems autobiographical: Julie and her live-in boyfriend Andre find a new apartment run by Madam Paul, a gushingly friendly woman with three nephews, one of whom owns the apartment building. Strange things go on in the building. Once a man tries to kill himself by putting his head in a gas oven, for instance, and Julie gets involved by phoning the police. When Madam Paul goes missing without explanation, Julie begins to imagine the worst, and she and her friends wander the building in search of the woman—and find, instead, a still in the basement. Eventually, Madam Paul shows up again and explains everything. Slice-of-life

stuff, which Doucet spices up a bit with the pseudo mystery. But my reason for

bringing this vintage piece up now is that the artwork exemplifies an aspect of

bad art: Doucet’s style is clutter. Doucet seems compulsive about her rendering. In the third and fourth panels of our first example, why is it necessary to draw every individual brick of the building’s wall? There’s a door behind Andre and Julie in the third panel—why? And the solid black draws attention to itself as if the door were the most important image in the panel. And why spend energy drawing a doorknob that gets confused with Julie’s right hand? In the fifth panel, Julie is in her studio, painting. Her head gets lost in the attempt to draw the painting she’s working on. And the clutter-clogged communication is further confounded by Doucet’s penchant for breaking words in odd places whenever she runs out of space in a speech balloon. She divides her boyfriend’s name “An-dre.” Makes it difficult to discern meaning in the verbiage. The last panel on our next page is so full of visual information that we can scarcely sort it out. Just behind Julie there’s a telephone on a stand, accompanied by a notepad and pencils in a cup. All very realistic but why go for authenticity when it overwhelms the visual narrative? In the background, there’s a little stool and a portion of—what? the kitchen sink? And a black cat. This sort of attention to detail is admirable if you’re taking visual notes on a botanical expedition, but when the pictures interfere with the storytelling, as they do here, the verdict must be “bad art.” And what’s the shading on the front of the old guy’s shirt? Always in the same place, is it some leftover dinner? Soil? Or does it indicate bulging girth? Finally, just to belabor what should, by now, be obvious—in the next-to-last panel, Doucet again renders a door in majestic black with white trim. Why? Is the door integral to the story? I muttered a few weeks ago that we should stop tolerating bad art in graphic novels and elsewhere throughout the cartooning universe. In the early days of the medium’s growing maturity, we welcomed slice-of-life stories because they demonstrated that comics could do more than portray the physiques of superheroes and superheroines. And because Doucet did those kind of stories, we tended to overlook how badly her stories were served by the clutter of her drawings. We need to stop ignoring artwork that so obviously isn’t suited to the task the artist attempts to give it.

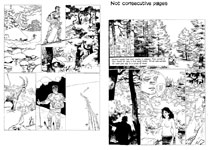

Lost in the Alps By R. Cosey 128 8.5x11-inch pages, b/w; 1996 NBM paperback, $34.98 “new”; $12 or less on Amazon IN STUNNING CONTRAST to Julie Doucet’s cluttered panels is the pristine rendering of Cosey in this graphic novel of love and danger in the alps sometime before 1930. A famous English writer, Sir Melvin Woodworth, visits a resort to trace the footsteps of his mysterious musician older brother, Dragan, who died and disappeared in the vicinity. Suffering from writer’s block, Woodworth wanders the mountainous countryside, hiking and skiing, and which affords Cosey the opportunity of drawing snow-covered hillsides, haunting in the silence of their still majesty. On one of his forays, Woodworth sees the girl Evolina bathing in a warm spring. She disappears at once, and Woodworth spends no little time trying to find her again. He hears a piano being played in a deserted building in the village. His brother played the piano there for a living, and the piano playing sounds like his brother’s way of playing. He begins writing again. Meanwhile, the glacier on the mountainside overlooking the village begins groaning and cracking, signaling that an avalanche is brewing. The village is evacuated, but Woodworth stays behind to solve the mystery of the piano player, who turns out to be Evolina, who had taken lessons from Woodworth’s brother. And it further transpires that the brother’s supposed financial success had more to do with Evo’s father than with Dragan’s musical ability. The police come to the deserted village looking for old Baptistin, Evolina’s father, who is an accomplished counterfeiter. Woodworth and Evo, now lovers, leave the village to find Baptistin, and the three flee the cops over the snowy mountains. Baptistin stays behind the lovers to delay the police; he’s successful but when he proceeds across the frozen escarpment, he falls into a crevasse, and before Woodworth, who returns in search of him, can pull him out, the crevasse closes on the old man, killing him. Woodworth and Evolina leave the alps and live happily ever after. The story is a nicely suspenseful tale with a satisfying romantic ending, but it’s Cosey’s drawings that give the narrative life with their haunting evocation of the snow-stilled mountainscapes, sometimes rendered in simple crystaline outline; sometimes, cloaked in contrasting shadow.

Here we have an object lesson in how pictures can enhance a story, a sharp contrast to the kind of hindrance we found in Madam Paul.

Chillax By Jerry Scott and Jim Borgman 242 6x9-inch pages, b/w; Harper Teen paperback, $9.99 JERRY SCOTT

AND JIM BORGMAN created this first Zits novel in an unabashed effort to lure

reluctant teenage readers into the world of printed text. With their tongues

partly in their cheeks, they say the Zits book, Chillax, is a “bridge

book” between Diary of a Wimpy Kid and Moby Dick. And Scott and

Borgman believe the book’s pictures, which proliferate through the book, one on

nearly every page, will tempt young readers to pick up the book and then read

it. The book is about the Zits protagonist, Jeremy, going to his first real rock concert—without his parents and with a mission in mind. Jeremy, remember, is an aspiring rock god. But the book is unusual not because of its story but because of the technique of its storytelling. While it’s commonly supposed that Scott writes the Zits comic strip and Borgman draws it, that’s not quite true. They are, after all, both cartoonists, so they both think as writers and drawers. "In other [comic-strip] partnerships,” Borgman told Michael Cavna at ComicRiffs, “the roles are always pretty distinct. With us, it really helps that we're both seeing the same thing with the writing and drawing." They say the division of work isn’t exactly equal, each claiming to do 75% of the work. In producing the strip, they pass ideas—and strips—back and forth a lot, making adjustments as they go. They did the same with their book: “Sometimes,” Cavna writes, “they would pass their prose back and forth, paragraph by paragraph; other times, one writer would take on a chapter to be honed later by the co-author.” Says Scott: “We try to take that idea of Diary of a Wimpy Kid, and push that and take it a step further with the illustrations." "I try to make the drawings further the story along," Borgman explains. "You need the [visual] information to get down into the story." Engaging in such big-page visual storytelling not only propels the young reader — it also liberates Borgman from the cramped quarters of the latter-day newspaper comic strip. "It's fun to break out of the little boxes," Borgman says. "In those little boxes, you can contort yourself down into that size if needed. But I did [bigger] editorial cartooning for some 30 years, and I like a big space to stretch out in." The

relationship between the book’s illustrations and its prose is more intimate

than is usually the case with an illustrated book: in Chillax, sometimes

the pictures add meaning to the words—as in the adjacent example. As in any good comic strip, visual-verbal blending gives a meaning to the combination that neither words nor pictures achieve alone without the other. It’s a nearly perfect recipe for encouraging reading.. Not all the pictures in Chillax blend with the prose in cartoon fashion. But many do. Taken all together, the pictures may tempt young readers to open the book, but the expectation—a cartoonist’s expectation—is that those readers will find the pictures explained, elaborated on, in the text, thus encouraging them to read as well as watch. Scott and Borgman are already writing their follow-up to this first novel. And they already have a rocking title: Shredded. "It's about a road trip," Scott says. "Which for us is like making a record on warm vinyl," Borgman notes.

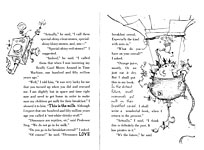

Fortunately, the Milk By Neil Gaimen with copious illustrations by Skottie Young 128 5x7-inch pages, b/w; Harper hardcover, $14.99 A TRIVIAL TALE OF BLATANT, UNRELENTING NONSENSE about a father who goes out to get milk for his son and daughter to put on their breakfast cereal. He takes so long on his errand that when he returns with the milk, he feels obliged to explain why it took him so long, so he makes up an extravagant story about being kidnaped by alien outer space monsters in Professor Steg’s Floaty-Ball-Person-Carrier (hot air balloon). He encounters numerous strange things and creatures, but, somehow, manages to retain his grasp on the milk carton and eventually escapes and gets back home. His kids, to whom he relates these adventures, don’t believe a word of it. Intended, probably, for children (or, more precisely, for parents to read to their children), the book provoked my interest because of Young’s illustrations, which occur throughout, on every page. Hereabouts, I’ve posted a few.

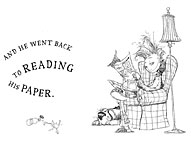

Apart from Young’s playful, antic style of drawing, the thing that intrigued me most was the possibility that the pictures and Gaimen’s prose were somehow inter-related, blending in an admired cartoonish fashion—the pictures contributing meaning to the text and vice versa—as they do in the Zits novel, Chillax. Alas, that blending doesn’t happen much. If at all. Mostly, Young’s pictures decorate the pages (superbly, hilariously), illustrating the story—showing us what Professor Steg’s Floaty-Ball-Person-Carrier looks like, for instance—amplifying but not adding meaning to the text. In short, we don’t need the pictures in order to comprehend the events of the story as we do fairly often in the Zits book. Only once, in fact, does a picture blend with the prose to reveal a meaning neither has alone without the other. At the end of the book, after his kids announce that they don’t believe his tall tale, the father says he can prove it’s all true. How? they wonder. “Well,” he said, “—here’s the milk.” That,

of course, proves nothing. But the next page reports that the father went back

to reading his paper, and we see this picture in which the father gives us a

knowing, conspiratorial look—a look that might be saying, “That’s how you prove

that a nonsense fiction is actually fact.” Or, perhaps, “Now, we both know this

is all bullshit, but let’s not spoil the fun, eh?” Or something akin. Never a fan of Neil Gaimen, I’m sad to report that this book does little to change my mind. His nonsense is too manufactured, too painstakingly contrived to provoke children’s laughter. Floaty-Ball-Person-Carrier? Lewis Carroll, he most emphatically is not. And because Gaimen is not a cartoonist either, the words and pictures don’t blend much.

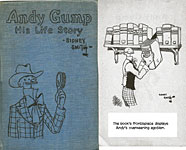

Andy Gump: His Life Story By Sidney Smith 184 5.5x8.5-inch pages, b/w; 1924 Reilly & Lee hardcover, antique prices (I bought a copy for 50 cents) THE GUMPS, you’ll remember, was a celebrated Chicago Tribune comic strip, so popular by the early 1920s that people would ask newsstand dealers for “the Gump paper,” not “the Chicago Tribune.” Whilst pondering the Zits novel and the Gaimen-Skottie book, I remembered this ancient tome, which is almost as copiously illustrated by its author, the cartoonist for The Gumps. Andy Gump,

the paterfamilias, is a champion blow-hard, an egomaniac who is easily

persuaded to write his “life story”—i.e., this volume—which, as you can see,

turns out to be a larger tome than those devoted to the lives of other

worthies, Julius Caesar, Adam (of Garden of Eden fame), Napoleon, Washington,

Lincoln, and Roosevelt. The book begins with a typical Andy utterance: “Yielding to popular demand—yes, even to popular pleading—I undertake to present so much of my autobiography as it is possible to condense into a single volume. And yet, when I think of the utter inadequacy of one volume for the task, I must smile. Smile—yes. But modestly, as is my custom.” He retails the rest of his story—infancy, youth, and adulthood—in the same temperate tones, but I’m concerned here chiefly with whether words and pictures blend in the manner of a comic strip as they often do in the Zits volume. Alas, they don’t. Sometimes, yes; but most often, the pictures are either stand-alone gags or they simply decorate the pages, adding visually no narrative information to the text they accompany. Here are a few by way of example. I’ve highlighted the prose pertinent to the pictures.