|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 317 (October 31, 2013). Welcome to our first Double Autumnal Issue—a gargantuan hoard of purely fascinating articles about cartoonists and cartooning. Vast. (Nothing half-vast about us.) Headlining this posting is a brand new Watterson interview (yes, someone finally got him to talk), plus reports on the presumed murder of a Syrian editoonist, the truth about Walt Disney, lots of editoons on the political shenanigans of October (shutdown, debt ceiling, Tea Baggers suicide, Obamacare roll-out, etc.); and reviews of the PBS superhero documentary, Matt Bors new book, Benny Breakiron, Blondie’s first year of marriage, Hand of Fire (Charles Hatfield’s book analyzing Jack Kirby’s legacy), and farewell to the great Canadian editoonist, Roy Peterson—and more, much more. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department—:

NOUS R US Watterson Interview Watterson Film First New Asterix Book Peter Bagge and Margaret Sanger Craig Yoe Gets Dorfed Kevin Keller To Be GLAAD Spirit Day Advisor Chad Carpenter and Michale Fry Kickstarting Films Clay Jones Back at Freelance Star

JAILED SYRIAN CARTOONIST SLAIN? Editooning in China Censorship in the U.S. Matt Bors Wins Fischetti Bors’ New Book Reviewed

SUPERHERO PBS EXTRAVAGANZA FLAWED Charles Hatfield Critique

IDW Expanding into Television Archie’s Silberkleit Battles Bullying A Telling Portrait of “Uncle” Walt Disney

EDITOONERY Last Months Crop of Cartoons on—: The Shutdown The Debt Ceiling Obamacare The Outrageously Suicidal Tea-Bagged GOP Insurance Exchange Roll-out Debacle— With Accompanying Tirades and Assorted Shims

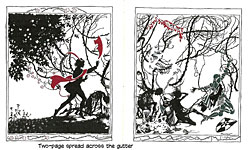

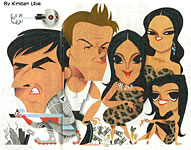

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Playboy’s Growing Myopia New York Times Sports Cartoon Arthur Rackham Silhouettes Wine Cures New Caricatural Styles

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Taboos Being Broken

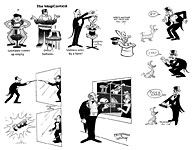

BOOK MARQUEE Short Reviews of—: Spiegelman’s Co-Mix Benny Breakiron in Red Taxis Peyo: The Life and Work of a Marvelous Storyteller The Smurfs Anthology, Vol.1 A Rabbit Under the Hat (Magic Cartoons)

BOOK REVIEWS Chic Young’s Blondie: From Honeymoon to Diaper Days (1933-1935) Hand of Fire: The Comics Art of Jack Kirby

GRAPHIC NOVELS Old City Blues, Vol.1 Off Road (Sean Murphy’s First)

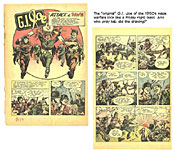

COLLECTORS’ CORNICHE Laughing Jesus The Golden Age G.I. Joe

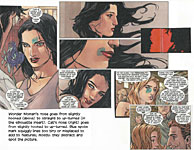

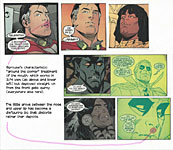

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Superman and Wonder Woman Tom Strong and the Planet of Peril Resident Alien

PASSIN’ THROUGH Roy Peterson, Canada’s Master Editoonist, 1936-2013

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

CALVIN AND HOBBES AND WATTERSON Mental

Floss, the magazine

of lasting trivia (“where knowledge junkies get their fix,” as it says on the

cover), managed to do something no other publication has: it snagged an

interview with cartoonist Bill Watterson, whose passion for personal

privacy is legendary if not obsessive. An article based upon the interview

appears in the magazine’s December issue (the cover of which, is just about

here). Here’s the e-mail exchange:

Jake Rossen: There is a tendency to rehash and

regurgitate properties with sequels and remakes. You had an idea, executed it,

then moved on. And you ignored the clamor for more. Why is it so hard for

readers to let go?

JR: Years ago, you hadn’t quite dismissed

the notion of animating the strip. Are you a fan of Pixar? Does their

competency ever make the idea of animating your creations more palatable?

JR: Your fight over protecting Calvin

and Hobbes from licensing deals, and your battle to increase the real

estate for your Sunday page comic, were notable—partially because they

indicated your incredible autonomy over your work. Had you "lost"

those battles, it appears you would have ended the strip. It reminds me of

Howard Roark and his desire to blow up his building rather than see it molested

by other hands. Was there a critical moment in your career that instilled such

unwavering creative integrity?

RCH: Undoubtedly, Watterson was pressured by Universal Press, as Universal Uclick was called then, to allow Calvin and, particularly, Hobbes the tiger to be licensed. But the pressure eased off pretty fast after Watterson made it unalterably clear that he was adamantly opposed to any such tampering with his characters. His philosophical position was that the characters lived within the comic strip; any attempt to take them out of that context would inevitably compromise the life they led therein. They would no longer be living only in the strip. And if their “lives” were compromised, so would Watterson’s creative impulse be diminished. Thereafter, Universal would periodically approach him on the matter, hoping he’d had a change of heart; but he didn’t change. I think he eventually quit the strip because he was weary of the annoyances of such overtures. But Universal played pretty straight with him. The magazine article based on this interview makes it clear that the syndicate, although disappointed, was sympathetic to Watterson’s view. Lee Salem, at the time the syndicate official with closest ties to Watterson, is quoted: “We had a lot of internal discussions.” Legally, Rossen writes, “the company could have proceeded without Watterson’s permission. But, as Salem said, ‘ultimately, we decided it was in our best interests not to alienate the best cartoonist of his generation.’ With some regret, Universal renegotiated Watterson’s contract from 20 years to 10 and signed over the domestic copyright to the strip in 1991. At last Watterson had complete autonomy over his work.” And four years later, he announced that he would end the strip December 31, 1995, when his ten-year contract expired. It was fatigue and finance, I think, that caused him to quit. As I said in Comic Book Marketplace No. 91 in May 2002: “The struggle to retain what he regarded as the integrity of his creation was surely a wearying endeavor. Watterson was cleary pretty exhausted by it. And he eventually realized that he didn’t need to continue to do it. He had money enough in the bank. Considering that the art he produced was brutalized by the medium that distributed it—the newspapers that ran comic strips so small that any real artistry is smudged away—and that he didn’t need the money, it’s no wonder that Watterson gave it up. No one goes on beating himself over the head any longer than necessary.”

JR: Where do you think the comic strip

fits in today’s culture?

JR: I’m assuming you’ve gotten wind of

people animating your strip for YouTube? Did you ever mimic cartoonists you

admired before finding your own style?

JR: Is it possible some new form of

sequential art is waiting to be discovered? Could the four-panel template die out

as newspapers dwindle?

JR: According to your collection

introductions, you took up painting after the strip ended. Why don’t you

exhibit the work?

JR: Purely for trivia and posterity’s

sake, if you could indulge some (even more) inane queries: One story that’s

made the rounds is that a plush toy manufacturer once delivered a box of Hobbes

dolls to you unsolicited, which you promptly set ablaze. For people who share

your low opinion of merchandising, this is a fairly delightful story. Did it

actually happen?

JR: I once read a mention of you

producing some original art intended for a Rolling Stone cover story

that “went south.” Considering your preference for privacy, an invasive profile

sounds like anathema. Was this very early on in the strip’s run?

JR: Owing to spite or just a foul mood,

have you ever peeled one of those stupid Calvin stickers off of a pickup truck?

Fitnoot from Poynter.org: Mental Floss Editor-in-Chief Mangesh Hattikudur says he has “no idea” why the cartoonist Bill Watterson, a Pynchon-esque recluse, chose to give an interview to Jake Rossen. Rossen somehow got Watterson’s email address, Hattikudur tells Poynter in an email. “We have a few theories: it might be because we have ties to Ohio, and a town near where he grew up (we used to operate our little shop out of Chagrin Falls; his signed comics often show up in a book store around there). Or it might be because of how Jake approached him—in a very journalistic [rather than] a fawning fan way. We weren’t totally sure it was him—even though we put two fact-checkers on the case—until his syndicate had to go to him for approval to use Calvin and Hobbes as the main art on our cover. (He’s very protective about licensing). He gave us permission immediately.” The magazine has “put other writers on the case before,” but none had Rossen’s luck, Hattikudur wrote. “It really stunned us when he pulled the interview.”

Further Feetnaught: Sam Price-Waldman at theatlantic.com reports that a forthcoming feature-length documentary, “Dear Mr. Watterson,” examines the appeal and impact of Watterson’s strip. In the film, comic strip cartoonists speak to how they were personally influenced by Calvin and Hobbes. Says Price-Waldman: “The film is a fascinating exploration into the artistic and philosophical harmony of the strip, narrated by filmmaker Joel Allen Schroeder.”

NAME-DROPPING AND TALE-BEARING The first Asterix comic book in eight years has been released after months of anticipation, reported Rene Moss at telegraph.co.uk. Five million copies of Asterix and the Picts, an adventure set in ancient Scotland—the 35th instalment in the French comic series—were released in 15 countries and 23 languages, the work of writer Jean-Yves Ferri and artist Didier Conrad, the first to produce an Asterix book not written and illustrated by one of the original creators, writer Rene Goscinny, who died in 1977, having created the series with his artist friend Albert Uderzo, who did several subsequent titles solo. The latest project of alternative cartoonist Peter Bagge (Neat Stuff and Hate) is a graphic biography, Woman Rebel: The Margaret Sanger Story, rehearsing the life of the early 20th-century birth control activist, nurse, political celebrity and founder of Planned Parenthood /Nathalie Atkinson, nationalpost.com/. ... Craig Yoe reports that he was nominated for Best Editor in the Shel Dorf Awards at the Detroit Fanfare Comic Con; he also received the 4th Annual Jerry Bails Award For Excellence in Comics Fandom. ... Fan favorite and Archie Comics' first openly gay character, Kevin Keller has been named a Spirit Day 2013 Ambassador, the first time the GLAAD organization has bestowed the honor on a fictional character /Brilan Trukitt at USA Today/. Alan Gardner at DailyCartoonist.com reports that two comic strip creators are seeking funding through Kickstarter for film projects. Tundra creator Chad Carpenter is hoping to produce a live-action comedy/suspense feature-length film based on a graphic novel he and his brother Darin wrote called Moose. “The story-line involves a mythological half-man/half-moose and an ecliptic cast of small town Alaska characters.” And Michael Fry, co-creator of Over the Hedge (with T Lewis), wants to direct a live-action/animated short called “New Soul,” about “a new human soul, before it’s born, sitting for an exit interview with an advisor. The new soul is charged with choosing his fate. It has to decide its future gender, level of intelligence, beauty and wealth all while racing the ticking clock of its impending birth.” Gardner also reports that editorial cartoonist Clay Jones, who was laid off from the Freelance-Star in 2012 due to budget cuts, has returned to his former paper as a freelance cartoonist with a weekly local cartoon to the Sunday edition plus a cartoon on the topic of his choosing for the online edition. Clay once said he’d never freelance for his former paper, but due to “a change in editors, editorial and top editor who I know well and respect very much,” he’s excited to return to cartooning: “For me, this gig isn’t as much of a big deal as the fact I’m going to start cartooning again. I’ve missed it so much and I’ve watched so many juicy issues go by. I’ve also missed a lot of opportunities to totally blast some people. I can’t wait to get going again. I’ve also missed writing a blog and can’t wait to resume that again also.” He will also do a cartoon caption contest and live blog the upcoming election night focused on the governor’s race.

JAILED SYRIAN CARTOONIST SLAIN? Akram Raslan was arrested over a year ago, on October 2, 2012, and was last seen July 26, 2013. Robert Russell, Executive Director of the Cartoonists Rights Network International, a watchdog organization that tracks the abuse and oppression of cartoonists worldwide, reported recently that Raslan has been executed. Others have disputed the report, and at this writing (October 28), Raslan’s fate has still not been ascertained for sure. Here’s Russell’s October 7 report, which I’m quoted verbatim for its passion and grasp of the situation for many cartoonists in emerging nations, followed by Public Radio International’s demurer.

Here

There Be Dragons: In Syria, Akram Raslan Is Murdered Somehow, along the way to prison, young 28-year-old Raslan (and possibly others) was peeled off, taken out and executed. He is reported to be in a mass grave somewhere near Damascus. Our reliable but for obvious reasons anonymous sources further allege that the murder of Akram and other condemned prisoners was carried out by Mohammad Nassif Kheir Bek, currently the Deputy Vice President for Security Affairs in Syria. He has already been sanctioned by the European Union for the use of violence against protesters and the Syrian civil war. Akram Raslan was the winner of the Cartoonists Rights Network International Award for Courage in Editorial Cartooning for 2013. Past award winners have hailed from Malaysia, South Africa, Turkey, Palestine, Iran, and India. Last year's winner, Ali Ferzat, was also from Syria. Here in the United States we are experts in the knowledge that editorial cartooning is a dying art. In other areas of the world, however, it is an art that people die for. CRNI has been monitoring and assisting political cartoonists in trouble for the last 20 years. They are often victims of failing regimes stamping out criticism, drug cartels squashing investigations, corporate interest protecting money and political manipulation, and religious zealots stamping out thinking. About nine months ago young Akram Raslan was abducted from the offices of his newspaper and "disappeared" into the Syrian dictator Bashir al-Assad's prisons for the next six months. Readers might remember the case of Syrian cartoonist Ali Ferzat who in 2011 had his hands broken by the Syrian regime's thugs. As they finished the job they told Ali that his broken hands would prevent him from disrespecting their master through his cartoons. Ali Ferzat was lucky. He survived the beating and eventually found safe haven in another Middle Eastern country. His revenge was to live to draw again. The hue and cry over this attack that grew from the world's journalists and cartoonists must have made an impression on Bashir al-Assad. This time, a beating wasn't enough. This time he decided to "disappear" the cartoonist permanently. We learned in late May that Akram would be part of a show trial where he would be charged with various crimes including sedition and disrespecting the head of state. The only evidence against him was his Facebook-posted cartoons encouraging people to laugh at the dictator. After his abduction, CRNI wrote a letter to the Syrian Ambassador in Washington, DC asking for his intervention in having Akram released. We quickly learned that Akram's trial would be postponed. We breathed a sigh of relief until we learned that instead of being released, additional charges of being a spy for the CIA and for Israel had been leveled against him. In Syria, under the present circumstances, these charges are a death sentence. Mark Twain once said, "Against the assault of laughter, nothing can stand." Our social scientists and our humorists will argue for the next hundred years about the mechanics and effects of laughter on human behavior. But one thing that Akram's apparent death has demonstrated above all else is how frightened the terrorists, the despots and the religious zealots are of people laughing at them. Tyrants might be able to fight off criticism or an insurrection or even assassination attempt with truncheons, bullets and terror. But where do they turn their guns to stop their people from laughing at them? Can there be any more efficient, more powerful, and cost-effective way of empowering a people than dispelling their fears with a courageous cartoon on its way to letting them laugh through their fear? It could be that Akram made a grave mistake in not running away sooner, or toning down the cartoons that he posted on his Facebook page. When I asked one of our past Award winners, Malaysian cartoonist Zunar, why he didn't take these avoidance actions in his own case, he faced me squarely and indignantly said, "This is my country. These tyrants have no more right to be here than I do." We are lucky here in the United States to have a long list of honorable, intelligent and articulate humorists who every day labor to pry open our heads and fill us with the courage to face our fears and prejudices. We are lucky that an effective rule of law protects them. Within the quagmire that has overtaken Syria and its people, it's difficult to know if right and wrong are even discernible any longer. One thing that Bashir al-Assad has proven is that on his way to protecting his own people and his own regime he is murdering Syria's dreamers and stargazers. Through the lives of people like Akram Raslan we are taught that it's not only the soldier in the heat of battle who must be called upon to exhibit courage. I am sorry I couldn't reach down into the pit and drag you out, Akram. Please forgive me. Perhaps your sacrifice will motivate us to look again into the mirror, and ask again where we straddle the line between fear and courage and challenge us, again, to take a new first step.

From

Public Radio International: The human rights group has good sources in and outside Syria. But there’s one

problem. On Facebook and Twitter, people are saying that Akram Raslan is still

alive. And Raslan’s own family doesn’t believe the reports that Akram is dead.

Following the initial report by Cartoon Rights Network International, Michael

Cavna of the blog Comic Riffs spoke to CRNI’s director Robert Russell and

afterward added some clarification. “CRNI’s report of Raslan’s death, Russell

tells us, is based on ‘a reliable source close to [his] family.’ Russell notes,

however: ‘The family is still saying that they don’t know [what happened], and

that nobody has told them anything.’ Russell has appealed for more information

about Akran Raslan on the Facebook page of the Syrian Journalists Association.”

At the

Washington Post’s ComicRiffs blog, Michael Cavna wondered if there is a chance that Raslan

could be alive, and he asked Russell. "There's a chance of it,"

Russell replied, noting that some of his contacts in Syria "will not speak

with me Up-to-date information may be found at cartoonistsrights.com. Here are a few of Raslan’s cartoons. Even if you don’t read Arabic, you can see that Raslan’s Assad is silly-looking, hence the object of laughter—something, as Bro Russell observed, no dictator is likely to tolerate.

EDITOONING IN CHINA In China, political cartoonist Wang Liming has spent three years publishing caricatures ridiculing China's leaders and is no stranger to the country's police. But it was a microblog post that got him into trouble most recently. Wang, 40, was the latest person targeted by authorities in a widening crackdown on online "rumor-mongering” that reflects a desire among Communist Party leaders "to dampen the effectiveness of the Internet to embarrass the government and press it to change,” said Maya Wang, Asia researcher for Human Rights Watch, reported by Sui-Lee Wee at Reuters (whose words we lift hereafter). Police in Beijing released Wang late Thursday, October 17, after taking him into custody at 11 p.m. on Wednesday. They had summoned Wang on a charge of "suspicion of causing a disturbance" for forwarding a post picturing a stranded grandmother holding her grandson who had starved to death in the eastern city of Yuyao, which was hit by floods two weeks ago. In an interview with Reuters, Wang said: "I told (the police), 'How can I be causing a disturbance? All I did was post a microblog.’” Wang, who is known online by his nickname, "Rebel Pepper", has had his microblog account deleted by censors 180 times, he said. Wang has more than 310,000 followers on his Sina Weibo account. State security officers first questioned Wang in 2011 in Hunan province after he had drawn a cartoon that said "One person, one vote, to change China." Wang asked them whether he was still allowed to draw cartoons. There is freedom of speech in China, the officers told him. This scale can be controlled by you and we'll not ask you to stop your work, they said. Two years later, Wang is still drawing. In one of Wang's recent cartoons, the character Winnie the Pooh was seen kicking a football. At the time, many microbloggers had seized on the likeness of President Xi Jinping and his U.S. counterpart Barack Obama with Winnie the Pooh and Tigger. Censors removed all the images and Wang's cartoon was also swiftly deleted. “For them, drawing leaders in cartoon form is a big taboo," Wang said. "I think the controls on the Internet are too harsh. They have no sense of humour. They can't accept any ridicule." People are likely to be charged with defamation if online rumors they create are visited by 5,000 Internet users or reposted more than 500 times. Wang said he knows his work has the potential to anger government officials and could put him in jeopardy, but at the same time, he cannot imagine a life of not drawing. "Many times, I tried to convince myself not to touch it anymore," Wang said. "But after a few days, I can't help it, I'm still concerned about these things. Perhaps it's the desire for a person to speak the truth, to express himself. This is very difficult to control."

CENSORSHIP EVEN IN THE LAND OF THE FREE SPEAKING Various webby sources have reported that Neil Gaiman's urban fantasy novel Neverwhere has been banned in Alamogordo High School in New Mexico. Not quite. The book has been removed from the school's "required reading list" after it was brought home by a girl whose mother objected because of the book's "sexual innuendos and harsh language.” The most recent report claims that three copies of the book remain on the library’s shelves, and there has been no attempt or request to remove them while it is being reviewed by the school board to see if it should be removed from even the school's voluntary curriculum. Karyn

M. Peterson at slj.com reported: “Gaiman originally wrote Neverwhere as

a BBC TV series, which aired in 1996, and adapted it the following year into a

novel. It was recently broadcast as a radio play for the BBC's Radio 4. In its

original review of the book, Library Journal said, ‘Gaiman's gift for

mixing the absurd with the frightful give this novel the feeling of a bedtime

story with adult sophistication. Readers will find themselves as unable to

escape this tale as the characters themselves. Highly recommended.’"

MATT BORS WINS FISCHETTI EDITORIAL CARTOON COMPETITION A Report from Columbia College Former altie

editoonist Matt Bors won the 2013 John Fischetti Editorial Cartoon

competition, hosted annually by Columbia College Chicago. Bors’ winning image,

posted here at your elbow, portrays two Native Americans sitting outside a

trailer listening to a radio account reporting that for the first time in the

United States, children of color will be the majority. “I often work in multiple panels, but sometimes all you need is one,” said Bors who recalled seeing and hearing panicked reports on the birth of non-white babies outpacing white ones. “No one in the media noted the fact that white people have only been a majority in North America for a relatively short time. Within a day it had become one of the most popular cartoons I’d ever done.” “This image simply and starkly references U.S. history and its many controversies, from the decimation of native tribes to debates about civil rights, affirmative action and whether Barack Obama is black or even born here,” said Nancy Day, chair of the Journalism department at Columbia College. “Editorial cartooning requires a unique set of skills. Bors’ winning entry demonstrates how a single image can skewer assumptions with very few words.” This national competition honors Pulitzer Prize-winning editorial cartoonist John Fischetti, whose work was published in the New York Herald Tribune, the Chicago Sun-Times and the Chicago Daily News. Following his death in 1980, his friends, family and colleagues established the political cartooning award and a scholarship fund in his memory in the Journalism Department of Columbia College. Each year, the competition honors a single image, published in the previous calendar year, that meets the highest standards of editorial cartooning and captures the zeitgeist of a particular period of American history. The judges awarded honorable mentions to Steve Breen of the San Diego Union Tribune and Nick Anderson of the Houston Chronicle, both former Fischetti winners and winners of the Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning. Bors was a 2012 Pulitzer finalist. Nationally syndicated, Bors, like many of today’s political cartoonists, draws for multiple platforms: his cartoons appear regularly in the Sacramento Bee, Portland Mercury, Pittsburgh City Paper, and on Daily Kos and are distributed by Universal Uclick. He also cartoons full time for Medium.com, where he edits the comics section, The Nib, and regularly draws for nsfwcorp magazine. Bors also delves into comics journalism. In 2012, he traveled to Afghanistan to draw comics and served as the comics journalism editor for Cartoon Movement from 2010-2012, where he edited a project on reconstruction efforts in Haiti. In 2012, Bors was the recipient of the Herblock Prize and the Society of Professional Journalists’ Sigma Delta Chi Award for his editorial cartooning. His first graphic novel, War Is Boring, a collaboration with journalist David Axe, was published in 2010 by New American Library. Through Kickstarter, Bors just published a collection of his cartoons with accompanying essays, an unusual combination these days, and the essays are as provocative as his cartoons—as you can doubtless tell from the title of the Preface: “The World Is Run by Assholes.” Fellow editoonist Jack Ohman provides the Foreword for Life Begins at Incorporation (236 8x9-inch pages, color; paperback, $20 through mattbors.com/store; you may be momentarily frustrated by finding yourself at Medium.com, where Bors hangs his hat these days, but if you keep searching under the URL just cited, you’ll eventually get to the book, which is available in both digital and hardcopy forms), and he begins: “I can sum up kick-ass cartooning in one word—Bors.” A few chapter titles indicate the scope of the book: Destination: Afghanistan, More Like Obummer, Homophobia Is Gay, One Nation Unemployed, Crouching Tea Party/Hidden Muslim, Avenging Uterus Rogues Gallery, Dear Gun Nuts, Social Media Is a Scam, Assorted Calamities. And there are more of this ilk. The screed parts of the book may eventually date the work as a whole. But until then, treat yourself to a startling array of words and pictures telling truth to Power (and making us laugh as well as cry). Here are a couple of the cartoons:

SUPERHERO EXTRAVAGANZA FLAWED But Not Much On October 18, PBS devoted all of its Tuesday prime-time schedule to the three-part documentary series "Superheroes: A Never-Ending Battle”—a cultural levitation of a genre neglected hitherto until it started getting made into movies. “That its first hour will do battle with a new episode of the Marvel Universe show ‘Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.’ is somehow appropriate,” quipped reporter Rob Owen in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Culturally serious but not very accurate. What, though, can we expect from a popular entertainment—even one as supposedly sophisticated and attuned as PBS? Funded by the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, the program, Owen said, “attempts to contextualize the stories of comic book superheroes within a greater history that includes the Great Depression, World War II, the congressional witch hunts of the 1950s, Watergate and more.” The first hour, entitled "Truth, Justice and the American Way" (1938-58), looked at the rise of patriotism that played into the birth of superheroes. The second hour, "Great Power, Great Responsibility" (1959-77) explores the impact of atomic energy, space travel and relatable problems on superheroes. And the third hour, "A Hero Can be Anyone" (1978-2013), chronicles “the rise of darker, more sophisticated storytelling.” In the first hour, one of the witnesses testifies that Jewish kids connected with the idea of superheroes—and two of the former invented the grandest of the latter, Superman/Clark Kent. No one, thankfully, mentions the golem of the Old World. Next, the narrative proclaims Captain Marvel, who surpassed Superman in popularity, the first superhero to dispense entirely with realism. Nothing was said, though, about DC bringing the law suit that put the Big Red Cheese out of business and thereby destroyed the competition. In perhaps the most egregious bit of historical legerdemain, the destructive role of crime comics in revamping the comic book industry is simply ignored. The Comics Code arrives seemingly unprompted, without provocation—and therefore without reason. The second hour of the show rehearses the rebirth of superheroes without being very specific about dates. Groups of superheroes—the Justice League, the Fantastic Four—were created, it is strenuously implied, out of the Cold War anxiety about the atomic bomb. Well, yes—in a way. Some superheroes, notably Spider-Man, were created because they were infected with atomic radiation of some fanciful sort. But in this notoriously copy-cat industry, most of the spandex set bowed onto the stage in imitation of some other superhero who had proved successful on the newsstand. Marvel’s Fantastic Four in November 1961 aped the Justice League of February 1960 because Marvel saw the success its rival was having with a superhero group title. Other dates of note in the revival are: October 1956, the debut of the “new” Flash (as the first in the sequence, probably the most important of the dates but not mentioned in the show; and while Stan Lee is credited for the new popularity of superheroes, DC’s Julie Schwartz, who started the parade with the Flash, is not much noted); August 1962, Spider-Man; December 1966, Jim Steranko’s invasion of the four-color world with his revamped Nick Fury and spectacularly visual storytelling style; January 1966, the debut of Batman on tv; June 1972, Luke Cage, the medium’s first black hero. But none of these dates are actually cited in the show Various attempts are made to connect comics to contemporary culture. Cage’s Hero for Hire is an installment of the blaxploitation movement that started, more-or-less, with the movie “Shaft” in 1971. The Punisher, who is conspicuously a Vietnam vet when he started in 1974, is offered as a distant relation to the “anti-hero” Dirty Harry who came along three years earlier in late 1971. But the sequence of Dirty Harry to the Punisher, while obvious, is not necessarily cause-and-effect, which impression the show works to create. The growth or maturing of the medium is attested to by the death of Spider-Man’s girlfriend Gwen Stacy in June 1973; with that, comics definitively “turned the corner from fantasy to real life.” The last hour of the program continues this effort by emphasizing the game-changing accomplished in 1986 by Frank Miller’s Batman and Alan Moore’s Watchmen, the latter seen as a response to conservative fascism. Similarly, the creation of the X-Men is portrayed as a corrective reaction against bigotry, but I don’t remember this theme being that evident at the start. It’s rampant in the series now and has been for quite some time. At first, however, I suspect the X-Men were seen by their adolescent readers as fellow sufferers in a world of adults who don’t understand them. Revisionist history, however, makes crusaders of them all. The formation of Image Comics is noted in passing but nothing is said about why the company was started (chiefly to escape corporate oppression and to reinvigorate storytelling by picture-making cartoonists rather than word-stringing writers). Following conversations with Adam West about tv’s campy Batman, the narrative turns to Linda Carter for her views on Wonder Woman, whom she played on tv starting in November 1975—which, in the logic of the show, ipso facto ushered in tv’s Hulk in November 1977. Both were serious attempts to make superheroes seem real; neither veered off into the previous decade’s campy formula of Batman. After that, the program virtually ignores comic books in order to extol the arrival of successful big screen incarnations of the four-color heroes beginning with Christopher Reeves’ “Superman” in late 1978. The third hour ends with a series of interviews in which various of the creative teams producing comic books proclaimed the world-changing influence of funnybook superheroes. Just a little overwrought. Stan Lee appeared several times, commenting on successive innovations in the medium. As far as I’m concerned, he was the star of the show. His tongue-in-cheek puffery put it all in much more appropriate context than the series’ closing with all the blather about our needing superheroes and Superman never dying and the like. Lee ended every one of his historically insightful pontifications with a wink. Comics historian Charles Hatfield (author, lately, of a critical analysis of Jack Kirby’s oeuvre, Hand of Fire: The Comics Art of Jack Kirby; see the Rancid Raves Book Review section down the scroll), is more critical than I. In his review of the three-parter, “PBS Documentary Fumbles” at superheroreader.org, Hatfield disparages Stan Lee’s contributions as the usual self-aggrandizing “mythology of solo creation” of the Marvel Universe in which the contributions of Steve Ditko and Jack Kirby are ignored. I didn’t get that. Lee didn’t mention the other creators of Marvel’s “marquee characters,” but he didn’t seem to be claiming he’d invented them all himself either. I suspect that Hatfield was projecting the customary criticism of Lee into the void Lee left by not crediting the artists who not only drew his creations but gave them life and stature. Hatfield calls the documentary “three hours of colorful, good-looking television and bad history.” He admires “the show’s ‘layers of imagery’—it’s rich visual presentation, which interleaves comic book images, clips from movies, tv, and games , archival footage and new interviews with comic book creators and other talking heads,” which, Hatfield says, is better done in this program than in others he’s seen. But it’s still bad history, and he details the evidence. The role of fandom in stimulating the comic book industry is entirely ignored; ditto the vital function of the direct market with its comic book shops. The comic book as art is neglected “though there is a surprisingly lengthy lovefest for Jim Steranko’s graphically hip late-sixties work.” Moreover, the documentary does not deal adequately with the crucial period between the end of World War II and the rise of the self-censoring Comics Code. “While noting in a sketchy fashion the superhero genre’s decline after the War and the emergence of other genres [notably the influence of romance comics on later superhero comics], the narrative moves altogether too quickly, and misleadingly, to the anti-comic book crusade of the early mid-fifties. ... The fact that the superhero was all but dead as a market genre prior to the imposition of the Comics Code is never acknowledged: the narration would have us believe that the [anti-comic book] crusade and the Code nearly killed the genre when in fact history shows that the genre came back precisely in the post-Code environment, indeed that the genre thrived under the Code for a considerable long time. ... In other words, [the documentary] falls into the usual superhero fan trap of making the superhero the barometer of the entire comic book industry’s health.” The third episode, Hatfield says, “is insufferable. As it seeks to widen the scope of the show beyond comic books themselves, it succumbs to extravagant self-congratulatory guff about superheroes becoming a modern mythology and a universal symbol of hope even as they colonize other media (movies, tv, gaming, etc.).” For the most part, I agree with Hatfield although I think he expects the documentary to be about the comic book industry not just its announced subject, superheroes. For a general audience—that is, the tv audience—rather than for comics cognoscenti, the program wasn’t bad. But if you want to luxuriate in a tsunami of acute scholarly invective, visit superheroreader.org and read all of Hatfield’s masterful and historically attuned review.

COMIC BOOK FIRM IDW PUBLISHING TO EXPAND INTO TELEVISION IDW Publishing has formed a television division to develop and finance projects based on its supernatural comic books, reports Richard Verrier at latimes.com. IDW, Idea and Design Works, already publishes a wide range of comic books and graphic novels based on film and television titles, including "Doctor Who," "G.I. Joe," "Star Trek" and "Transformers,” and there are movies of its own comic book series, including Sony Pictures' "30 Days of Night" in 2007. "The success of 'The Walking Dead' has opened the door for all sorts of comic books to go to the small screen," said David Alpert, a partner in Circle of Confusion, IDW’s management company. "We find the stories that are told in comic books are natural adaptations for television." And the storyboards are already done. IDW's primary business is publishing comic books, and it is the world's fourth-largest comic book publisher, behind Berkeley-based Image Comics, DC Comics and No.1-ranked Marvel Comics. IDW has 42 employees and relies on a network of about 275 freelance artists from the U.S., Chile, Australia, Britain, Japan and other countries. Demand for comic books and graphic novels has been brisk in part because of the proliferation of new digital outlets. IDW's sales, which exceed $20 million annually, are up 35% this year over last, said Chief Executive Ted Adams. "Unlike most print media that has been savaged by digital versions of content, our digital distribution is up and our print [business] is up as well," Adams said. "People are discovering comics on their digital devices."

SILBERKLEIT UP TO SOME GOOD In Svetlana Shkolnikova’s report in the Fort Lee Suburbanite about Archie Comics co-CEO Nancy Silberkleit’s visit to a school on October 15, you wouldn’t know Silberkleit is embroiled in several nasty legal struggles at the Riverdale HQ. The article was all about Silberkleit’s efforts to promote anti-bullying. Silberkleit, a former art teacher, surrounded herself at the school with artwork from various stages of comic book production as she discussed career options and her anti-bullying comic Rise Above. Silberkleit has shared her message with countless classrooms around the world over the past two years, either in person or through Erica Walters, the bullied heroine of Rise Above. In the comic, Erica begins her first day at a new middle school and learns to deal with a bully who harasses her with taunts of "braceface," dumps a soda on her, and posts the resulting photo on social media. Silberkleit said she can still identify with the embarrassed, pained expression on Erica's face as a group of students jeered at her, and she decided to pour her experiences into a comic book. Says Shkoljnikova: “She began leading talks about bullying after reading about several bullying victims who had ended their lives. She dedicated Rise Above to Mitchell Wilson, an 11-year-old Canadian who committed suicide in 2011 because his muscular dystrophy made him a regular target of attacks. “Her success at Archie Comics and the work of her foundation Rise Above Social Issues led to her inclusion in the Commerce and Industry Association of New Jersey's Women of Influence event this year.” Well, it’s about time Silberkleit got some decent publicity.

A TELLING PORTRAIT OF ‘UNCLE WALT’ The Mouse House has a reputation as a controlling institution. It is aggressive in protecting its wholesome image and its copyrights—quickly taking to court anyone caught using the symbolic Mickey or, even, Donald without permission. So Brooks Barnes at the New York Times was surprised at what he saw in the coming movie “Saving Mr. Banks,” a comedic drama about the turbulent making of “Mary Poppins” in the 1960s. In the movie, “Walt Disney acts in a very un-Disney way. He slugs back Scotch. He uses a mild curse word. He wheezes because he smokes too much. The real shocker?” Barnes goes on—“Walt Disney Studios made the film.” Barnes continues: “The movie, which stars Tom Hanks as the mustachioed founder of the Walt Disney Company and Emma Thompson as the cantankerous novelist P. L. Travers, is a small movie that cost less than $35 million to make. But its existence says something big about Disney: despite its well-earned reputation for aggressively managing its image, it can get out of the way and let filmmakers lead.” Many writers and directors don’t offer projects to Disney Studios because they believe “Disney will never make this movie, so let’s not even try.” For “Saving Mr. Banks,” the director, John Lee Hancock, said, “I was a bit afraid because we wanted to be honest about Walt. I imagined the moment when Disney would say, ‘Sorry, we like him better as a god than a human.’ To their credit, they were smart enough and brave enough to realize that a human Walt was not only a better character, but was easier to love.” “Saving Mr. Banks,” says Barnes, “at times lampoons the company’s style. ‘I won’t have her turned into one of your silly cartoons,’ Thompson’s character says of Mary Poppins. No, she says, a visit to Disneyland would not change her mind; in fact, she would be ‘sickened’ to visit that ‘dollar-printing machine.’ “And in one scene that has gotten big laughs in early screenings, Thompson’s cranky writer arrives at her hotel for meetings with Walt Disney to find her room stuffed with balloons, caramel corn and toys. Shoving a stuffed Mickey Mouse into a corner, she snaps, ‘You can stay there until you learn the art of subtlety.’ “Life imitated art last year when Thompson arrived for filming and found that Disney had done the same thing to her hotel suite. ‘Believe it or not,’ said Sean Bailey, president for production, with a twinkle in his eye, ‘we do have a sense of humor.’ And

the portrait of Walt Disney that emerges may be close to the truth. He was a

demanding boss and had a keen sense of what was funny and appropriate in a film

and how to do it, particularly when animation was in its infancy. Animator Jack

Kinney, who began working for Disney in 1931 and stayed for 20 years,

running the Goofy unit and winning five Academy Award nominations and an Oscar

for “Der Fuhrer’s Face,” revealed the sometimes cantankerous side of his

employer in his 1988 book about the early years at the studio. I’ve posted the

cover picture here because it so aptly illustrates the personality of the

Disney Kinney knew. “Walt went to great lengths to portray himself as a shy person, ‘Uncle Walt,’ a kindly, self-effacing farmboy from the Midwest who prided himself on the fact that he never owned a tuxedo. He was a great admirer of Will Rogers, and copied his mannerisms in public, which added to the image. He was certainly Midwestern—waspish, down to earth—but he could swear like a trooper, and he had a terrific ego.” About the picture on the cover, Kinney elucidates: “Walt roamed his domain with a hard-heeled stride that, along with his distinctive [cigarette] cough, warned us of his arrival. He’d crash through the door, stride to a chair, sit down, and tap his fingers on the arm until one of the guys grabbed a pointer and proceeded to tell the story [of the animated cartoon the storyboards of which were pinned on the wall]. Walt’d usually allow the guy to finish, then all the boys would hold their breath until he started talking. We studied him the way he studied the storyboards. If he coughed, you knew you’d lost his attention. A slow tap meant he was just thinking, but a fast tap meant he was losing his cool.” “It

was bandied about by the boys in the back room that Walt stopped in the studio

basement on his way in to change into his mood costume for the day. These moods

were known as ‘the Seven Faces of Walt,’” Kinney said. And then he illustrated

them. When a few Disney staffers were once asked by a reporter to describe Disney’s sense of humor, a pause ensued; after a short wait, one came up with a single telling word—rural. Said Kinney: “The sorts of things that tickled Walt were outhouse gags, goosing gags, bedpans and johnny pots, thinly disguised farts, and cows’ udders.” We’ll see ere long just how accurate “Saving Mr. Banks” is.

Fascinating Footnit. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com/comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

QUOTES AND MOTS “The fragrance always stays on the hand that gives the rose.”—Hada Bejar “24 hours in a day; 24 beers in a case. Coincidence?”—Anonymous “Of the many imprisonment possible in our world, one of the worst must be to be inarticulate—to be unable to tell another person what you reall feel.”—Roger Ebert

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy THE WEEK magazine, the only American

periodical that regularly, every issue, devotes its cover to a political

cartoon—and in full, vibrant painted color—commemorated the end

of the government shutdown and the defeat of the Grandstanding Obstructionist

Pachyderm with a picture showing Twitch McConnell and John Boehner (pronounced

“craven”) bearing the marks of having survived a fight but not without bruises

and scars. The GOP’s grinding defeat in its confrontation with Bronco Bama is not disputed by any rational observer of the passing scene. But the rabid Tea Baggers, displaying the political acumen that has distinguished their machinations all along, are unrepentant. They caused economic damage (the economy lost an estimated $24 billion due to the shutdown) and political wreckage and got absolutely nothing for it, but they are already planning to do it again when the budget issue and the debt ceiling must be negotiated again in a few months. Tea Bagger House members’ marching orders: Don’t let up, especially on the Affordable Care Act. “We’re winning this argument and now have to go back at Obamacare and getting our fiscal house in order,” saith Deedee Vaughters, a Tea Bagger in South Carolina. Grover Norquist, the no-taxes poobah, says next time they’ll have an “endgame strategy.” “We’ve made real progress, and next time, we have to reset and refocus on the debt and Obamacare,” said Representative Ted Yoho, frosh GOP from Florida. “We’ll be looking for any opportunity,” said Representative Tim Huelskamp, a Republicon from Kansas. “We took a shot at it, and we fell short, and I think we are waiting around for another battle over Obamacare.” With clowns like this in Congress, the nation’s editoonists had a field day for the first two weeks in October. Only 83 percent of the government was closed, by the way, but you’d think the whole shebang was shuttered if you attended to the ever-vigilant Froth Estate, which rejoiced in a fetid long-running story to wallow in, over and over again, day after day after day—mustering an endless parade of gasbags and pundits to testify in end-of-times terms to the looming catastrophe. Something like 800,000 government workers were “furloughed” because they were “non-essential”; as David Letterman put it, “There’s your problem, right there.” About 400,000 of the furloughed were Defense Department workers—civilians all; no military were furloughed. Another 1.3 million toiled without pay until the shutdown ended and they were able to collect back pay. At the IRS, 90% of the employees were sent home without pay; incidentally, they haven’t had a raise in three years—but Congressmen get an annual cost-of-living increase every year whether they need it or not. Much

of the cartoon commentary focused on how self-destructive the GOP effort was. In

our next visual aid, Mike Luckovich continues in the same vein: for him,

the Clueless Clucks Clan in Congress is a band of terrorists, and Luckovich

adds the grace note—they’re also blind. (I’m about to launch here into one of my not infrequent Political Tirades; if you want to avoid the foam and fury, you can skip what follows immediately by scrolling down to the first paragraph that begins with ALL CAPITAL LETTERS.) Tea Baggery threatens the very system of government that has made democracy an ideal for many still-forming nations. From across the Atlantic, the Economist noticed that the Tea Bag precedent, “if followed, would make America ungovernable. ... If a party with such a modest electoral mandate threatens to shut down government unless the other side repeals a law it does not like, apparently settled legislation will always be vulnerable to repeal by the minority. Washington will be permanently paralyzed and America condemned to chronic uncertainty.” And how much a minority is the Republicon party in Congress? In the election a year ago, noted Hendrik Hertzberg at The New Yorker, “in Senate races, Democrats drew 10 million more votes than Republicans. In the House of Representatives, Republicans, whom Democrats outpolled by a million and a half, retained their legislative majority only by dint of the vagaries of districting and re-districting.” These figures are based upon state populations: New York is more populous than many other states but has only two senators (both Democrats), who polled more votes than the two Republican senators from, say, the less populous Wyoming. The Economist also took note of the “vagaries of districting” in this country. Every ten years after the census, every state must look at its congressional districts to see that the populations thereof are roughly equal (so congressmen each represent about the same number of people). When populations shift, district boundaries are re-drawn. Re-districting is usually achieved by drawing the lines to include only the incumbent’s supporters—or fellow party members—excluding the opposition party. “This means,” explained the Economist, “that a typical congressman has no fear of losing a general election but is terrified of a primary challenge [from another member of his party]. Many therefore pander to extremists on their own side rather than forging sensible centrist deals with the other. This is no way to run a country.” Because of re-districting (or “gerrymandering,” a term used to describe the strangely shaped districts that usually result from drawing boundaries to protect incumbents), congressmen tend to live in political echo chambers: they consort with their ideological cohorts in Washington, and when they go back to their home districts, they hear from constituents who’ve been herded into enclaves of like-minded citizens. No one ever disagrees with an incumbent congressman. One possible result of this kind of politics is that Tea Baggers have come to believe that a majority of Americans oppose Obamacare. Yes, many do; but some of those who oppose it do so because they don’t think it goes far enough.

GETTING TO

THE OSTENSIBLE CAUSE of all the Tea Time tribulation, Obamacare, in our next

exhibit, Rob Rogers at the upper left states the proposition succinctly

by piling up a succession of facts: health care reform has been instituted in

this country through all the means a democracy has at its disposal. Yet the Tea

Baggers, possessed of a tunnel vision unequaled in modern times, persist in

trying to nulify a duly constituted law. (And here we go with another foaming-at-the-mouth Tirade. To avoid it, scroll down to the next paragraph that starts with CAPITAL LETTERS.) Once again, the alleged “news” media of the Froth Estate have done us no service in failing to report on the roll-out in ways that put it in context. You’d think, if you did your thinking based upon the headline reportage that passes for journalism these days, that the whole country is mired in the computerized glitches that have characterized signing up for health insurance in compliance with the individual mandate. Not so. The mandate requires that most people obtain health insurance or pay a penalty. Oddly, despite all the attention given to the mandate, 26 percent of the population isn’t aware of the requirement according to a Kaiser Family Foundation poll. And maybe that ain’t bad: after all, only about 10-15% of Americans are affected by the glitch-ridden mechanism. That’s right: 85-90% of the population don’t need to sign up for anything through the federal or state exchanges. That’s because they’re already covered: 55 percent have health insurance through their employers, 17 percent through Medicaid, 15 percent through Medicare, 10 percent through policies they have bought themselves, and 4 percent through the military. (The numbers add up to more than 85 percent because the categories aren’t exclusive, Politifact avers; some people have more than one kind of coverage.) So all the fuss and feathers about the “disaster” of the Obamacare-inspired Internet exchanges is flapping around for only about 15 percent (or less) of the nation’s population. Just 15% or less. But if you pay attention to the Froth Estate’s reporting (and the endless round of interviews of ravening partisans on both sides of the issue), you’d think the whole nation is trying to batter down the computerized obstacles to participation. The conservative opposition to the individual mandate is puzzling—if, that is, you hope for consistently logical thinking among conservatives. What the mandate requires is that individuals take responsibility for their own lives—particularly, their health welfare. What’s puzzling is that all this time, I thought the conservative philosophy called for individuals to take responsibility for their lives. And yet the conservatives seem bent on opposing that very thing in Obamacare. The Tea Bagged GOP aids and abets the confusion about Obamacare—not out of ideological disagreement, as most suppose, but because it needs an issue around which to rally the wild-eyed extremists that the party harbors as its base. The idea of the mandate was “originally a conservative idea developed in 1989 by the Heritage Foundation’s Stuart Butler to counter liberals’ efforts to establish a single-payer system,” reports kaiserhealthnews.org. “Several years afterward, Republicans used the individual mandate in a bill they offered as an alternative to Bill Clinton’s proposal to overhaul health insurance. The mandate was also incorporated as part of the Massachusetts overhaul of health insurance in 2008 under then-governor Mitt Romney.” Sowing mendacity, demagoguery and obstructionism, the GOP seeks to unhorse a law that was (as we’ve seen, thanks to Rob Rogers) adopted and endorsed by the American citizenry. As further evidence of their use of the Nazi tactic of the Big Lie, we have the Republicon contention that Obamacare will be devastating to small business. The foretold devastation is extrapolated from the law’s employer mandate that requires companies with 50 or more full-time employees to provide health insurance. But as James Surowiecki at The New Yorker (October 14) points out, “the overwhelming majority of American businesses—ninety-six percent—have fewer than 50 employees.” So 96% of American businesses aren’t affected at all by the employer mandate. Moreover, “more than 90% of companies with more than 50 employees already offer health insurance. “Only 3% are in the zone between 40 and 75 employees where the threshold will be an issue. Even if these firms get more cautious about hiring—and there’s little evidence that they will—the impact on the economy would be small.” Once again, the GOP has foisted off on the citizenry a Big Lie in order to undo the Affordable Care Act. But lying alone is not enough. Obstructionism is also necessary, the GOP believes. In another issue of The New Yorker (October 7), Atul Gawande details the three forms that most obstructionism takes: “The first is a refusal by some states to accept federal funds to expand their Medicaid programs. Under the law, the funds cover a hundred percent of state costs for three years and no less than ninety percent thereafter. Every calculation shows substantial savings for state budgets and millions more people covered. Nonetheless, twenty-five states are turning down the assistance [the number fluctuates, depending upon whether you count states “leaning” in the direction of ignoring the expansion or only those who’ve already slit their own fiscal throats]. “The second [form of obstruction] is a refusal to operate a state health exchange that would provide individuals with insurance options. In effect, conservatives [who are forever crying for smaller national government] are choosing to make Washington set up the insurance market and then complaining about government take-over. ... And some states go even further, passing measures to make it difficult for people to enroll. ... “The third form of obstructionism is outright sabotage. Conservative groups are campaigning to persuade young people, in particular, that going without insurance is ‘better for you’—advice that no responsible parent would ever give to a child. Congress has also tied up funding for the website, making delays and snags that much more inevitable.” And the funding issue reminds me about the criticism directed at the Obama administration—the State Department in particular—for refusing to beef up security when the Benghazi people asked for more. State couldn’t supply more because the GOP-controlled House had cut the budget.

IN OUR NEXT DISPLAY,

Obamacare and GOP obstructionism continue to be the topics. (Tirade alert.) Cruz and Lee are right, of course. The Republicon Party is the loser in all this. Just 28 percent of Americans now (as of October 25's issue of The Week) have a favorable view of the GOP, according to Gallup. “That’s a 10-point drop from only a month ago, and the lowest rating for any party in more than three decades.” Within days of the October report, came November 1's: A Washington Post/ABC News poll released this week found that 53 percent of Americans blamed the Republicans for the shutdown against 29 percent who blamed President Obama.” As a result of these shenanigans, the GOP is no longer the party of big business, said Robert Shapiro, chairman of the economic advisory firm Sonecon. “They’re the party of anti-government.” Despite the dropping popularity, Tea Baggers and the other ultra-conservatives refuse to accept defeat on the Obamacare issue. They’re likely to demand another “insane showdown” when the next budget and debt ceiling issues arrive early in 2014, said Ezra Klein at WashingtonPost.com. Conservative extremists still think they can force Democrats to surrender and make Obamacare disappear. Even for a party that’s been “careering ever more deeply into ideological extremism,” the strategy to threaten to wreck the economy and America’s credit rating marks a frightening new low. In fact such hostage-taking by congressional leaders has no precedent in our history, said Norm Ornstein in National Journal. Obamacare, passed by Congress and effectively re-affirmed by voters in the last election, is the law of the land. For the losers of that election to now demand that the ACA be killed anyway or they’ll shut down the government is “contemptible”—a defiant insult to democracy itself. And not something the Republicon Establishment is enthusiastic about. The conservative antipathy to party leadership may have its roots in an otherwise quite reasonable reaction to the regime of GeeDubya Bush. Yup, This Colyum’s old bogeyman is still alive and influencing his party. Daniel Larison at TheAmerican Conservative.com suggests that the present conservative wing’s tendency to resist the blandishments and advice and counsel of GOP elders is a result of their feeling betrayed by GeeDubya. Reflexively backing Bush against liberal enemies, the conservative grass roots found itself committed to the extraordinarily costly wars in Afghanistan and Iraq—and the expansion of the welfare state through unfunded Medicare prescription drug entitlement. By the end of the GeeDubya years, conservatives realized their allegiance had turned a budget surplus into a record $1.3 trillion deficit and had expanded rather than shrunk the government. Tea Baggers learned their lesson. They remember what happened the last time they compromised for the sake of party unity. Their credo: we won’t get fooled again. And so they run John Boehner (pronounced “boner”) rather than the other way around. Some believe, against all odds, that the Tea Baggers have been chastened by their defeat in confronting Obama last month. They won’t try again such extreme measures when the budget and the debt ceiling come up again in January and February. The looming mid-term election will reform extremists, say the optimists. Dropping poll numbers will make the Tea Baggers straighten up and fly right in order to get re-elected. Wrong. Take another look. Republicons would have won the showdown if they’d stood firm says Erick Erickson in RedState.com. Instead, they threw in the towel, letting Obamacare go into effect and handing the president a major victory. True conservatives must now fund primary challengers to oust these cowards. “If they refuse to fight for us, we must fight them.” The incumbent reaction to such a threat is to become more rigid, more extreme. Where it will end, no one can predict. Except, maybe, moi. I imagine that the moneyed class upon whom all politicians depend to fund election and re-election campaigns is growing weary of the Tea Baggers’ infantile antics. Big Business is accustomed to winning, to getting their way, and the moguls see that as GOP popularity plummets, their chances of influencing government dwindle. Not much, but a little. To preserve that influence, they are likely to abandon the more lunatic wing of the party. They’ll put their money on other horses. Or so I imagine.

THE ASSAULT

ON OBAMACARE specifically is the subject of the next couple of editoons. The

Tea Party itself comes in for a healthy drubbing in our next round of editoons,

beginning with Nick Anderson’s evocation of the viral image of Miley

Cyrus’ singing astride a wrecking ball. In

our next exhibit, the Tea Bagged Republicon relationship to Prez Obama is the

topic. And Pat Bagley is even more specific in his depiction of the “Stars of the Tea Party” as the stars in the old Confederate flag. They’re all there in Bagley’s slapdash but adroit caricature: Ailes, Coulter, Palin, Cruz, Mike Lee, the Koch Brothers, Cantor, Lumbaugh, Rand Paul, Hannity, Bachmann, Demint, and Beck. In using the Confederate flag as his dominant image, Bagley highlights the deeply racist bias of the Tea Baggers by allying them with the Old South’s history of slavery. And the Tea Baggers aren’t bashful about their bias. At a rally staged on the National Mall in mid-October, Obamacare and the Prez were denounced with “lunatic rhetoric” in what conservative news media called a “game-changing” event where “Don’t Tread on Me” flags were joined by a huge Confederate flag. Said Brian Beutler at Salon.com: So this is why the GOP held the nation hostage—to appease a small group of menacing “neo-Confederate fantasists.” It is scarcely an accident that of the 15 states that refuse to expand Medicaid as a way of asserting objection to the “socialism” of Obamacare, 7 are states of the one-time Confederacy. And three more in the same region are “leaning” toward rejecting the expansion, the old Solid South rises again. Since refusing to expand Medicaid means the states are giving up a healthy injection of federal funds at a time when most states need money, the tactic is almost wholly inexplicable—unless we view it as a mindless protest against a black man occupying the White House.

OUR NEXT

VISUAL AID makes the opposition to Obama even more absurd. Now

that the government is open again and paying its bills, the Republicons, ever

in search of some Obamathingy to rail against, turn to the flawed roll-out of

Obamacare’s computerized sign-up mechanism. To start us off at the upper left, Glenn McCoy, one of the more rampant salivators, ignores the problem-ridden launch in favor of simply lambasting the whole enterprise. Taking his visual cue from the expression “roll out,” he produces a crude (but effective among Tea Bagger fans) image that intends to show how Obamacare is hostile—destructive, flattening—to the U.S. A socialist steamroller, no doubt. Next on the clock, Bob Englehart dramatizes the extreme to which the Tea Bagger strategy goes: opponents of Obamacare tend to take the lurching of the launch as a sign that the entire program should be destroyed. That, as you might imagine I’d say, is benighted thinking: most of Obamacare is working just fine; the fumbling around in one area should not be taken as an indication that the entire enterprise is a failure. But try telling that to a Tea Bagger. The roll-out was badly handled, no question. And given that Obamacare and the individual mandate especially have been ripped vociferously by the vituperative of Tea Baggers and other 19th century zealots, it’s mind-bloggling that the Obama administration wasn’t more careful (even paranoid) in developing and testing the system before kicking it off. Even in an abridged description, the system is complicated: the website must first gather detailed income and other data from the applicant, combine it with eligibility data from dozens of state and federal agencies, and then offer a plan in compliance with 47 separate statutory provisions. Said Gordon Crovitz in the Wall Street Journal: it’s that “mind-numbing complexity not glitchy software that’s Obamacare’s fatal flaw.” Still, according to Stephanie Mencimer at MotherJones.com, in 2006 both GeeDubya’s Medicare Part D program for seniors and the “Romneycare” plan in Massachusetts (upon which the Affordable Care Act is based) got off to starts just as chaotic—if not worse. Romeycare’s roll-out was so bad that a full two months after launch, only 18,000 of the state’s 300,000 eligible citizens had successfully navigated the enrollment process and signed up. But the kinks got worked out, and today 96% of the state’s residents have health insurance—more than in any other state. (Yes, we’d expect Mother Jones fanatically to defend Obamacare; still, Mencimer’s assertion rings true to me since it attempts to correct an instance of the GOP’s usual misinformation effort and/or the news media’s neglect or myopia.) Back at our exhibit, at the lower right, Kevin “Kal” Kallaugher’s cartoon for the Economist presents a blockbuster image of just how destructive the Tea Baggers’ looney contrivances appear on the world stage. And, finally, Clay Bennett re-visits the extortion issue with a familiar tableau for this time of year. The imagery suggests that Obama is being petty, and I suspect that’s not quite what Bennett wanted. Turning

briefly to other issues, here are a couple cartoons on the plight of our guests

at Gitmo. We

continue to explore issues other than Tea Baggery in the next round of visual

aids. No one thinks the name “Redskins” is intended to be offensive. On Facebook, my friend Brian K. Morris reports (tongue in cheek) that the Washington Redskins have resolved to drop the most embarrassing word from their name—Washington. Another acquaintance of mine said that the expression “redskin” originated in colonial times and it referred to Native Americans’ applying red color to their faces as warpaint. Doesn’t matter, though: times change. The same acquaintance pointed out that the Minnesota Vikings are ripe for a similar name adjustment. Vikings are renowned for being fierce warriors and daring explorers—and (although seldom mentioned these days) for raping and pillaging. Surely no football team wants a reputation as rapists and pillagers. Times, they are a-changing. I blame Bob Dylan. I see no end of this kind of controversy—but a lot of silliness. Just up the road in Boulder, Christina Gonzales, the dean of students at the U. of Colorado, asked students preparing to celebrate Hallowe’en not to wear blackface or sombreros or dress up as squaws or cowboys. She warned that dressing up as someone from another culture can lead to “hurtful” portrayals of other cultures. Which flushes all sorts of questions. What about dressing up like a witch? Will that offend wiccans—or, as columnist Alicia Caldwell put it at the Denver Post—“Or descendants of women persecuted in the Salem witch trials?” What about hobos? Would a hobo costume be perceived as an insensitive depiction of migrant workers? Or a homeless person? The message, apparently, is that we should avoid stereotypes. “But what is a Hallowe’en costume if not a stereotype or a characterization. Surely that can’t be the only test, and surely all stereotypes can’t be offensive.” Caldwell consulted a CU campus expert on stereotyping. Intent matters; and so does the sensitivity of the audience. So we’re right back where we started from. The

next batch of editoons starts with Milt Priggee’s caricatures of

Clinton, Obama and the Pope. More for the sake of a laugh: the tattoo gag strikes me as being close to some sort of profound truth about our tat fixation. Dave Coverly’s attendant blow-drying the guy’s hands—hysterical. Dan Piraro is always funny and just a little quirky, and going from “my foot’s asleep” to “mine is tossing and turning” is a stunning example of what I mean.

SHIMS A shim is a wedgie used to fill in gaps in order to make something fit properly or to balance it if it teeters. Here are some that seem to serve the purpose with the shutdown/ceiling falling debacle and the ensuing roll-out fiasco:

From Sean Peirce at the dailyfelltoon.blogspot.com, Thursday, October 17: According to the latest Pew Poll, Americans now dislike the extremist Tea Party wing of the Republican Party more than they ever have before. The same poll shows Republicans are so ashamed of their extremist wing that most of them are in denial the Tea Party is even part of the GOP. What's more, the nominal leader of the Tea Party insurgents, Senator Ted Cruz of Texas, outright admitted Wednesday afternoon that his entire goal in this disaster was to raise money for any future political campaigns he might have. As Ezra Klein joked on Wednesday, Cruz may as well have been a sleeper agent for the Democratic Party, as the damage he's done to the GOP is deeper than almost anything the Democratic Party could have accomplished. Conservatives even began taking shots at their own closed loop media infrastructure, blaming it for only telling them what they wanted to hear. No surprise that the biggest blowhard in right-wing media, Rush Limbaugh, now says the Republican Party is the most irrelevant party he can remember. You built that, Mr. Limbaugh. Enjoy.

From Ana Marie Cox at TheGuardian.com: If Obamacare is really fatally flawed, “why would conservatives be so suicidally intent on preventing it from taking full effect?” Their great fear, she opines, is that “it won’t be too long until the ACA isn’t a new and scary socialist plot but just part of American life”—like those awful programs called Social Security and Medicare. In other words, what the Republicons fear most about Obamacare is that it will work.

From the New York Times (quoted and paraphrased in The Week): This is John Boehner’s shutdown. If he had allowed a floor vote on a “clean” funding resolution to keep the government open, with no “ridiculous demands,” it would have passed with a strong majority because most Republicans are keenly “aware of how badly this collapse will damage their party.” But out of fear of angering 30 to 50 Tea Partiers, Boehner cynically played a destructive game he knows Republicans cannot win—proving conclusively that he and his party are “incapable of governing.”

From Charles C.W. Cooke in NationalReview.com: [This shutdown lasted about 16 days; the shutdowns of Bill Clinton’s era (two of them, one in November 1995; the other in December 1995 into January 1996), 27 days. But the record for shutdowns probably belongs to the Reagan Administration.] Former Democratic House Speaker Tip O’Neill—beloved by liberals for his supposed knack for bipartisan compromise—shut down the government eight times during the Reagan administration. [Mostly for only a day or so each time.]

From Ezra Klein in the Washington Post: Republicans aren’t interested in negotiation. Compromise requires sacrifice from both parties, but in return for their demand to gut health-care reform, Republicans aren’t willing to give up anything of value to them. Agreeing to fund the government, or to raise the debt ceiling in two weeks, isn’t making a compromise—“it’s releasing a hostage.”

From William Falk, editor-in-chief of The Week: If not for the multiple “fiscal crises” created by Congress over the past two years, another 2 million Americans would have jobs. The unemployment rate would have dropped below 6.7 percent, and the growth of the GDP would be about 4 percent, instead of 2.5 percent. The robust economic recovery everyone’s been waiting for would finally be underway. So says a new study commissioned by longtime Republican deficit hawk Pete Peterson—no liberal. The analysis ... found that Congress’s fiscal-cliff and debt-ceiling emergencies have unsettled markets and employers, kept consumers in a cautious crouch, and paralyzed the entire system with uncertainty. The 5 percent annual cut in federal spending forced by the sequester, the economists found, has been too drastic and has retarded growth. America’s economy, in other words, is being actively sabotaged. Such self-destructive behavior is anything but conservative: vigorous growth would flood the Treasury with tax dollars and shrink the deficit. One of the flaws of democracy is that a small group of angry zealots can exert outsized influence. Just 18 percent of the U.S. population is represented by the congressmen who forced the latest crisis, but these extremists have intimidated Republican leaders, who value their own jobs more than yours.

From James Graff, executive editor of The Week: [About the malfunctioning health care website], critics have blamed faulty communications with contractors, an arrogant White House, or Big Government in general. ... At the most fundamental level, the epic fail of HealthCare.gov is a vivid demonstration of the human propensity to cling to what we want to believe, rather than what the facts tell us, when we’re facing a threat. The contractors and bureaucrats who mismanaged the launch of Obamacare had to know they were in big trouble when the massively complex software crashed during a very limited testing. Why did they go ahead with the scheduled launch anyway? For the same reason that House Republicans went ahead with a government shutdown and the threat of debt-ceiling default, even though almost everyone outside their bubble warned them that this strategy was doomed and would backfire. Psychologists call such blinkered thinking “motivated reasoning.” Human beings are primarily emotional, not rational, so we engage in “confirmation bias”: we start off with what we want to be true, look for evidence that supports our hopes, and screen out that which does not. When she was asked why she didn’t advise the White House to delay the rollout of the troubled website, Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius said, “Waiting is not really an option.” Neither, apparently, was facing an inconvenient truth.

READ AND RELISH Culled from Somewhere On the Web: An award should go to the United Airlines gate agent in New York for being smart and funny, while making her point, when confronted with a passenger who probably deserved to fly as cargo. For all of you out there who have had to deal with an irate customer, this one is for you. A crowded United Airlines flight was canceled. A single agent was re-booking a long line of inconvenienced travelers. Suddenly, an angry passenger pushed his way to the desk. He slapped his ticket on the counter and said, "I HAVE to be on this flight and it has to be FIRST CLASS." The agent replied, "I'm sorry, sir. I'll be happy to try to help you, but I've got to help these folks first; and then I'm sure we'll be able to work something out." The passenger was unimpressed. He asked loudly, so that the passengers behind him could hear, "DO YOU HAVE ANY IDEA WHO I AM?" Without hesitating, the agent smiled and grabbed her public address microphone. "May I have your attention, please?" she began, her voice heard clearly throughout the terminal. "We have a passenger here at Gate 14 WHO DOES NOT KNOW WHO HE IS. If anyone can help him with his identity, please come to Gate 14.” With the folks behind him in line laughing hysterically, the man glared at the United Airlines agent, gritted his teeth, and said, "F*** You!" Without flinching, she smiled and said, "I'm sorry sir, you'll have to get in line for that, too." Life isn't about how to survive the storm, but how to dance in the rain.

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Pictures Without Too Many Words

AT HAND is

the cover of the current (November) issue of Playboy, an unusual