|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 270 (December 9, 2010). In a long and longing ramble of an installment, our Big Stories this time include a highly critical look at The New Yorker’s annual “cartoon issue,” a report on Ted Rall’s Afghanistan venture (plus a glimpse of his incendiary Anti-American Manifesto), mini-reviews of numerous Papercutz books, discussion of the latest casualties among the editorial cartooning ranks, Stan Lee’s Soldier Zero and the Wonder Woman movie (not). Here’s what’s here, in order, by department, beginning with an apology and/or correction:

Odds & Addenda: An Apology NOUS R US Spider-Man Crashes on Broadway Sale of Comics and Graphic Novels Down Lennie Peterson Is Back with The Big Picture Wuerker Wins Berryman Who’s Palle Huld? Garfield Snafu Big Nate: The Wimpy Kid

MAGAZINE CARTOONING The New Yorker’s Annual “Cartoon Issue,” A Little Lame What Is Minimalism Anyhow? Newcomers at The New Yorker Playboy Limps Into Christmas, Without Stockings or Other Raiment

RAGHEAD RITUALS AND A NEW REVOLUTION Life With Ted Rall & Company

NBM AND THE EUROPEAN CONNECTION Part One: Papercutz and the Smurfs Biography of Peyo Biography of Papercutz The Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew Graphic Novels Harry Potty and a New Line of Parody Titles Rick Parker

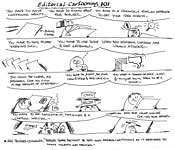

EDITOONERY Three More Lose Jobs Kirk Anderson’s Lovely Rant Ramsey’s Buck-up Last Month’s Cartoons Everyone’s Own Facts & GOP Fictions The Ethics of Partisan Journalism and Political Donations Mallard Fillmore Speaks His Mind

THE FROTH ESTATE U.S. News and World Report Goes Digital Newsweek Becomes a Daily Beast Under-reported Stories of 2009-2010 Writing Sports Stories with a Computer

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Lascivious Pix

DEPARTMENT OF JIVEY

BOOK MARQUEE Barnaby a-Borning The Economist’s Kalendar for 2011 Was Superman a Spy? The Peanuts Collection (Memorabilia and Scraps of Art) Shameless Art (Pin-ups, Of Course) Holy Sh*t! The World’s Weirdest Comic Books

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Stan Lee’s First Soldier Zero Incognito All-New Wonder Woman Disrobes Why Is There No Wonder Woman Movie?

ONWARD, THE SPREADING PUNDITRY Senator “Twitch” McConnell and Statesmanship Blue Dog Democrats, Unemployment under Reagan, and Earmarks

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—

Odds & Addenda. Way back in Opus 224, I reviewed an essay by Patrick Rosenkranz in a book entitled Underground Classics, and I complained that he didn’t question or qualify ug cartoonist Robert Williams’ paranoiac assertion that in the early 1970s, he and his cohorts feared that a government “clamp down” was coming: “We know for a fact that they were reconditioning internment camps in eastern and southern California. Our phones were being tapped, and the cops were watching down the street. It was just continual surveillance. Either we were going to get forced into the army or we’d get thrown into an internment camp.” While I could accept the possibility of the Feds’ eavesdropping on ug cartooner phones, the internment camp idea seemed to me over the top, and I said Rosenkranz ought to have made some editorial remark to the effect that Williams’ “facts” here were dubious. Well, like the man said: even paranoids have real enemies. As I was about to discover. A few weeks ago, I recycled the review on my Hare Tonic blog at tcj.com, and soon thereafter, undergrounder Jay Lynch, an old friend, wrote me about my resistence to Williams’ “facts”: “On Williams' quotes on the paranoia of the era over surveillance: Many of us did get our FBI files under the old Freedom of Information Act which confirmed said surveillance. And documents have been released and countless books written about the Fed's MK ULTRA program which further confirm that we were being watched by the Fed. So it would seem to me that the surveillance issue would be well known by the average reader of 1960s lore. And going into MK ULTRA would have been as unnecessary for Rosenkranz to have gone into as, say, the reason for Nixon's resignation.” I had forgotten about J. Edgar Hoover; had I clawed memory of him and his paranoia up from the back of my mind, I wouldn’t have questioned Williams’ claim about being surveilled. That’s not really so preposterous, given the times, and it, by itself, wouldn’t have prodded my dubiousness. But the internment camps—I still think that’s a little farfetched. For the early 1970s. Lynch tells me I’m being naive, and he may be right. In any event, I don’t question the existence of internment camps today: GeeDubya and Darth Cheney have worked their subrosa magic wonderfully. (Although I never thought I’d use “magic” and “wonderfully” in the same sentence as “GeeDubya” and “Darth Cheney.”) My apologies to Williams and to Rosenkranz.

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits Broadway’s Spider-Man, “Turn Off the Dark,” did not exactly flop on its “preview” night, November 28, but it fell short of the promise implied by the extensive treatment it received that night on “60 Minutes.” The $65 million stage production attempts to do with wires from the ceiling what the Spider-Man movies do with special effects—make the Webslinger swing into action, flying through the air with the greatest of ease over the heads of the audience, which, on this auspicious occasion, numbered 1,900. But the machinery was balky and the show stopped for various adjustments four times, with actors dangling in mid-air for minutes at a time. The mechanical failures, however, apparently had no effect upon the audience, which, for the most part, endured interruptions patiently and with warm understanding—and did not, in noticeable numbers, demand its money back for tickets that cost as little as $140 and as much as $375. Nor was the potential audience much influenced. According to report on “NBC Nightly News” the next night, most of those who planned to see the show are still eager to witness the most expensive production ever mounted in American theater, an attraction that prevails whether the machinery works or not. The show is scheduled to open January 11; but don’t hold your breath: delays have been the history of this production. As of December 5, at least three of the show’s actors have suffered injuries severe enough to keep them off-stage. “The Walking Dead,” the new series on AMC that has just concluded its inaugural 6-show season to rave reviews by critics and fans, is based upon the comic book of that name from the so-called mind of Robert Kirkman, who, contemplating the next season of the tv version, cautions funnybook-spawned fans of the tv series: “You may not have the insider knowledge you think you have. Things may play out differently with Rick and Shane. And that’s great.” In Newsweek for November 22, editoonist Rob Rogers snared both of the cartoon slots that the magazine fills each week. ... And in The Week magazine for December 10, Ed Stein got two of the five editoon slots. (We’ll show you one of his on the other $ide of the wall.) ... Free Comic Book Day in 2011 is May 7. For the first several years of this annual event, it was scheduled to coincide with the release of a blockbuster movie about a comic book superhero, but lately, FCBD has plowed a free-standing rut for itself: the first Saturday in May every year. ... Fox has announced that they have renewed “The Simpsons” for a 23rd season, making it the longest running comedy in tv history. ... Martin Sheen has been cast to play the role of Uncle Ben in the forthcoming Spider-Man movie, according to Deadline Hollywood. Sheen will join Rhys Ifans as the villain, Emma Stone as Gwen Stacy, and Andrew Garfield as Spider-Man. Sally Field is in talks to be Aunt May. The movie is slated for release July 3, 2012. ... DelawarePunchline.com is a new online humor magazine from editoonist Rob Tornoe; the December issue is up and free and full of humor columns and cartoons of all sorts. The most recent issue (No. 1673, January 2011) of the Comics Buyer’s Guide, once the industry’s holy writ, had only 58 pages. The magazine’s dimension shrunk a year or so ago when it dropped its monthly price guide feature, which pandered exclusively to wealthy collectors rather than readers of comics. But the diminished page count is less ominous than the almost complete absence of advertising. The previous issue had 40 more pages, and all of them were ads—for one company, Comic Haven Auction. Can CBG survive with such an anemic advertising allocation? Ironically, its forerunner, The Buyer’s Guide (TBG, as we used to say), was, for most of its early history, all ads. Year-to-date over-all sale of comics and graphic novels through Diamond Comic Distributors are down by 5.79% compared to sales over the first 11 months of 2009; graphic novels show a somewhat smaller decline, 4.35%. “To be fair,” ICv2 reported, “comic sales didn’t suffer nearly as much as most other entertainment sectors during the worst of the great recession in 2008 and 2009. The difference between graphic novels and comics would have been smaller save for what transpired in November. Dollar sales of periodical comics in November were down 10.2% when compared with November of 2009, but graphic novels rebounded strongly with a 14.84% jump over November 2009 fueled by the release of the latest volume of Robert Kirkman’s The Walking Dead, which has got plenty of ‘juice’ thanks to the highly popular debut of “The Walking Dead” on tv. ... The first volume of The Walking Dead, which was originally released in 2004, also made the top ten, a sure sign that the tv series is having an effect on sales.” After reporting declining sales in the Top-Selling 300 comic book titles and in graphic novels in the third quarter, ICv2 got to wondering: what if the decline in the Top 300 category were offset by increases in the rest of the range, all those titles that aren’t in the Top 300? So they did some careful re-casting of figures and formulations. The conclusion? “Sales below the Top 300 may be growing in importance, but when we look at a fairly long period (10 months) either they aren’t big enough in the aggregate to make much difference, or their sales are changing at about the same rate as the Top 300's. If anything, looking at year-to-date numbers, sales on the titles below the Top 300 are shrinking faster than sales in the Top 300, at least in periodical comics.” No rousing news there. Mort Walker went back to his alma mater, the University of Missouri in Columbia, to help with the festivities of opening an eatery in the new student union. Named Mort’s, the place honors UM’s famous graduate and the hangout he frequented when matriculating there, The Shack. Quipped Walker: “This new eatery has all the wonderful things The Shake had—tables, chairs, a ceiling.” He said he got a kick out of celebrating The Shack: “It’s like celebrating a dumpster.” ... Also in October, Walker was presented with the Cartoon Art Museum’s “Sparky” Award for 2010. Named after Charles M. “Sparky” Schulz, the award recognizes significant contributions of cartoonists who embody the talent, innovation and humanity of the Peanuts creator. Past recipients, listed in the September-October issue of the NCS Cartoonist, include Sergio Aragones, Gus Arriola, Dale Messick, Will Eisner, Creig Flessel, Phil Frank, Morrie Turner and Schulz himself. Cartooner John Backderf, creator of the uproarious scatologically satiric altie strip The City, was excused from jury duty by an Ohio judge when Derf, responding to a question, said, Yes, he did know someone who had been convicted of a crime. As reported in The Week, Derf said: “I had a close friend in high school who killed 17 people.” That was serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer, who ate parts of his victims and froze the rest in his refrigerator. His life story Derf turned into his first graphic novel. Dark

Horse will celebrate its 25th anniversary next year; this year, Greg

Evans’ Luann is passing the same quarter century milestone (with a

superlative retrospective collection that we’ll review next time; available

only online through Evans’ page at TheCartoonistStudio.com/Greg). And Jan

Eliot’s Stone Soup has passed its 15-year marker. ... Lennie

Peterson is back with his autobiographical strip, The Big Picture, in which he sardonically records his nefarious adventures and attitudes as a

failure and layabout—at the opposite extreme, that is, of a continuum with Keith

Knight’s The Knight Life at the other pole, recording the success of

the author. This time, The Big Picture is running exclusively at GoComics. Politico’s Matt Wuerker won the Berryman Award for excellence in editorial cartooning. It’s been a stellar year for Wuerker, noted Michael Cavna at ComicRiffs.com: he won the Herblock Prize in April and was named a finalist for the Pulitzer. Said Wuerker: "I'm thrilled to get the Berryman Award. I share it with all the other ink-stained wretches out there doing such great work as political cartoonists. I only wish more of them were as fortunate as me to get to work with such smart, trusting editors like mine here at Politico. It's a dream perch for a cartoonist." According to the judges, "Matt's drawings blend satire, irony and the right amount of anger to skewer the politically powerful of all persuasions." (Well, yes—but don’t all good editoons do these things? You’d think the judges could say something about what makes Wuerker’s wuerk unique.) Honorable mention for this year's Berryman went to the Post’s Tom Toles; Daryl Cagle of MSNBC; and Jimmy Margulies of the Record (New Jersey). The Berryman comes with a $2,500 prize; honorable mention is worth $500.

DANISH ACTOR Palle Huld died on November 26 in a Copenhagen retirement home; he was 96. He was a stage actor and also appeared in over 40 Danish films between 1933 and 2000, but his niche in history verges on the nearly undivulged. In 1928 at the age of 15, said Margalit Fox at the New York Times, Huld won a competition sponsored by a Danish newspaper that wanted to send a teenager around the world to celebrate the centennial of Jules Verne’s birth by reenacting Phileas Fogg’s trip “Around the World in Eighty Days” in Verne’s 1873 novel with that title. There were stipulations: the winner had to be a teenager, had to circle the globe unaccompanied, and had to complete the trip in 46 days, using any conveyance but the airplane. The paper, Politiken, picked Huld from several hundred applicants. Huld, a Boy Scout, had quit school and was working in an automobile dealership. He left Denmark on March 1, 1928, “and as he traveled by rail and steamship, the world press chronicled his every move, through England, Scotland, Canada, Japan, the Soviet Union, Poland and German,” Fox notes. “It also recorded his triumphant homecoming, after just 44 days, to a cheering crowd of 20,000 in Copenhagen.” Huld subsequently wrote a book about his adventure, A Boy Scout Around the World, published in 1929. Among the cheering throng hailing Huld upon his triumphant return, was, perhaps, a 21-year-old cartoonist named George Remi, who would, the next year, launch a comic strip feature about a teenage boy reporter, Tintin, who would travel the world in search of news and adventure. Some Tintin historians have included Huld among the possible inspirations for Herge’s intrepid boy reporter. Herge himself apparently never spoke about the matter, and Pierre Assouline, the author of the latest of the cartoonist’s biographies, Herge: The Man Who Created Tintin, told Fox he’d never heard of Huld. But coincidences are hard to overlook. Huld was a Boy Scout, and Herge, at the time, was drawing a comic strip about a Boy Scout. Given the worldwide notice Huld received, it’s hard to believe Herge, scribe to Scouting, wouldn’t have about him. Moreover, as Fox notes: “Like his comic book incarnation, Huld was fresh-faced and freckled with a turned-up nose and unruly red hair. On his journey, he was often photographed wearing plus-fours, Tintin’s breeches of choice.” Pretty conclusive evidence, seems to me.

GARFIELD FANS CAN JOIN THE ORANGE FAT CAT in his daily doings by uploading a photo of themselves at pixfusion.com. Soon after, presto!—the facial photo will appear at the summit of Jon Arbuckle’s body (or Liz Wilson’s) where the comic character’s head ought to be but, now, isn’t. Now, it’s your face instead. “A four-pack of animated comics costs 99 cents to personalize and can be streamed,” saith Matt Moore at the Associated Press. The operation is destined to move to iPhone and iPad and other mobile platforms. Said Jim Davis, Garfield’s creator: “It’s really a nod to where the industry is going. Everything’s going online.” On November 11, Garfield suffered from Davis’ nodding off several weeks before in approving for publication that day a strip in which Garfield threatens to swat a spider, who responds with a rant: “If you squish me, I shall become famous. They will hold an annual day of remembrance in my honor, you fat slob!” And, after a pause, the spider continues: “Does anyone here know why we celebrate ‘National Stupid Day’?” No one apparently noticed through the production cycle that the strip would appear on “an annual day of remembrance,” Veteran’s Day. Davis, appalled, rushed to issue an apology, saying the strip, which “seems to be making a statement about Veteran’s Day, has absolutely nothing to do with this important day of remembrance.” It had been written almost a year ago, “and I had no idea when writing it that it would appear today—of all days.” When the strip went into the production queue, Davis didn’t realize that it would run on Veteran’s Day. “What are the odds?” he said. “You can bet I’ll have a calendar that lists everything by my side in the future.” Davis noted that his brother served in Vietnam and his son, in Iraq and in Afghanistan. “You’d have to go a long way to find someone who was more proud and grateful for what our veterans have done for all of us. Please accept my sincere apologies for any offense today’s Garfield may have created. It was unintentional and regrettable.”

BIG NATE IS FOLLOWING in the Wimpy Kid’s wimpsteps and vice versa. Drawing in a simple wooden style—much like Scott Adams in Dilbert but somewhat larger and with fatter lines—Lincoln Peirce created his comic strip about middle schooler Nate Wright in the early 1990s and got it syndicated in 1991 by United Media. With his distinctive multi-cone hairdo, Nate is a self-described genius, the syndicate publicity says: equipped with only his hairdo, a No. 2 pencil and the unshakable belief that he is destined for greatness, “he fights a daily battle against overzealous teachers, undercooked cafeteria food and all-around conventionality.” Although it runs today in about 200 newspapers, Big Nate is not what the average citizen would call a roaring success. Until the Wimpy Kid books came along and showed just how to make a fortune with simple wooden-stiff artwork. Last March, HarperCollins Children’s Books launched the first of a six-book series starring Peirce’s character: Big Nate: In a Class by Himself. At least two other titles have been released: Big Nate Strikes Again and Big Nate From the Top. The first two are more-or-less original effusions for the books; the third title begins to exploit the fertile ground of reprints, harvesting its content from the strip’s 20-year inventory. This could go on forever, or at least to within a couple months of infinity. These volumes are obvious attempts to cash in on the Wimpy Kid Phenomenon. And a certain perverse poetic justice lurks therein. Jeff Kinney, the Wimpy creator, was a big fan of Big Nate, saying: “Lincoln Peirce is one of my cartooning heroes, and Big Nate ranks as a comics classic. Year in and year out, Big Nate is among the best comics on the funnies page.” When Kinney was an undergraduate at the University of Maryland (from whence cometh Frank Cho and Aaron McGruder—the place is a hothouse of cartooning talent), he wrote to the Baltimore Sun, calling Peirce’s strip “the best of the new generation of cartoons that make the comics page worth reading.” Is it, then, too much to suppose that Kinney, after realizing he would probably not become a political cartoonist, stared at Peirce’s “comics classic” and said to himself: “I could do that.” And did, creating the first of the Wimpy wonders.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, comicsdc.blogspot.com and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

Quotes and Mots This time, a sampling of inscriptions on t-shirts. You have to know that these alleged witticisms are intended to be on t-shirts: in the strange and wonderful way that comedy works, if you saw them as stand-alone mottos or bumper stickers, the humor is diminished. Here are some: In dog beers, I’ve only had one. Life is short: buy the shoes. Just call me butter because I’m on a roll. I before e except after c. Weird? My garage needs me now. The least I can do is be there for it. Handyman’s rule: cut to fit; beat into place.

***** I sometimes mourn urban progress. For many years, the Shubert Theater in Chicago was across the street from Burt’s Shoes; then Burt’s Shoes was replaced by Payless Shoes and poetry died an unremarked death.

MAGAZINE CARTOONING FOR ALL IT’S WORTH The annual indulgence from The New Yorker showed up a couple weeks ago. Dated November 1, the so-called “cartoon issue” is, as usual, a mixed blessing at best; at worst, a grudging nod in the direction of the artform that keeps the magazine afloat—beguiling readers as well as filling coffers. Some years ago, the magazine’s management acknowledged that its Cartoon Bank generated enough income to tip the balance sheet from the red to the black. And even the effetely journalistic editors have sometimes admitted that most of The New Yorker’s readers skim through each issue to smile at the cartoons before getting serious with the articles. Still, the blessings of the “cartoon issue” are mixed. On the one hand, it’s gratifying that one of the last two remaining major markets for magazine cartoons thinks cartoons are important enough to warrant an annual celebration of this sort; on the other hand, it’s disappointing that, after the promising 1997 beginning of the series that featured text pieces about cartooning and/or cartoonists, the magazine hasn’t subsequently been able to find much to write about in connection with the artform or those who practice it. I once offered my essay on World War I’s doughboy cartoonist Wally Wallgren, famed cohort of New Yorker founder Harold Ross at the Stars and Stripes, who, perversely, never made it to Ross’s new magazine when it got launched; but they were having none of it, so I sent it to Hogan’s Alley. (If you didn’t see it there, you can find it here, in Harv’s Hindsights for February 2009.) Instead of a text piece about cartooning or cartoonists, the editors have in recent “cartoon issues,” including this one, published an article about a comedian, thinking, apparently, that since cartoons incite laughter, anything that provokes laughter is suitable fodder for the “cartoon issue.” This year, it’s 27-year-old Aziz Ansari, whose parents immigrated to South Carolina from India before Ansari was born, so he speaks with a Southern accent rather than the British-inflected Indian. If you watch “Parks and Recreation,” you’d recognize him as Tom Haverford, “an inept ladies’ man”; but I don’t watch “Parks and Recreation,” so I don’t recognize him at all, but I’m looking forward to reading the article even though it’s not about a cartoonist. The 122 pages of this issue of The New Yorker are like most issues: they carry a generous sprinkling of cartoons throughout. It qualifies as the “cartoon issue” by reason of an 18-page section devoted entirely to cartoons: 18 single-panel cartoons of the usual sort plus 8 manifestations of Roz Chast, a 4-page comic strip by Zachary Kanin (“Noah’s Ark,” funny but pointless except for its irreverence), and 6 of the past winners of the magazine’s weekly Caption Contest, ostensibly celebrating the Contest’s fifth anniversary but actually a cheap way to fill 2 more pages with reprints rather than fresh inventions. I’ve never quite understood the fascination Chast holds for The New Yorker audience. Her comedy takes the form of determined cataloguing, which, admittedly, is usually a mildly (it aims for no more) and insightfully amusing assessment of our societal foibles; but her drawings are close to the worst among equals. (The worst are the attempts of Bob Mankoff, the magazine’s cartoon editor.)

WAIT! Time out! We interrupt this epidemic of logorrhea for an Important Denial followed by an Object Lesson. Denial first: I don’t really think Roz Chast’s drawing is the worst in the magazine, maybe not even close to the worst. I got carried off by the sentence as I was writing it—it and the next one. Object Lesson: I fell into the pit that an amateur writer sometimes staggers into: casting around, desperately looking for words to string together, he finally pulls together enough for a sentence, which, upon inspection, he thinks is just too cute or clever and so he lets it stand there even though he doesn’t, quite, agree with what he just wrote. In my case, I liked the “worst among equals” fillip, but I also realized that I didn’t think Chast actually made that grade so I stuck “close” in there, which led me, pell mell, into who the worst drawer might be, and Mankoff’s “attempts” qualified him. Nicely ironic, he being the cartoon editor, and I still believe his drawings are the worst in the magazine. But Chast, as it stands right now, is the victim of a sentence gone rogue rather than considered opinion. Good writers, as opposed to amateur scribblers, are careful not to be seduced by witty sentences into saying things they don’t believe. Years ago, witnessing just such a performance by a writer whose facility with words I admired, I realized that some of what he’d written he probably didn’t quite believe—but he liked the seeming astuteness or hilarity or euphony of the sentences that were proclaiming these half-truths, so he left them alone. I decided I wouldn’t do that. But here, I just did. Or I just about did. So now I’m trying to redeem myself by saying what I actually believe about Chast’s drawings, deploying, for the purpose, a modicum of precision. They’re pretty lame, the drawings. (“Lame” is the word I was toying with before I got sucked into the “worst among equals” formulation. I should have stuck with “lame.”) They’re lame because her line lacks confidence, and so do her compositions. The faces of all her characters look the same, and her command of anatomy is tenuous: she can’t draw hands (or, to judge from the evidence persistently before us, ears), and the arms of her characters look like spaghetti. And the cross-hatching that she does is more knitting than shading. Yes, her drawing still might be close to the worst in the magazine, but she’s not alone. She’s with Ed Koren’s shaggy humanoids and Bruce Eric Kaplan’s wide-stance matrons and David Sipress’s tiny-footed wobblies and Barbara Smaller’s finicky shading that is desperately searching for a reason for being in the drawing. I realize I’m being irreverently hard on these eminences, but when I think of Peter Arno and Helen Hokinson and Charles Addams and George Price—not to mention Sam Cobean, Whitney Darrow Jr., Chon Day, Alan Dunn, F.B. Modell, Saul Steinberg, Gluyas Williams and Eldon Dedini (to let slip the names of a few of the Grand Masters of the Medium)—I have to wonder how this other lot get published so often in a magazine renowned for what it calls its “drawings.” It is a mystery best explained by the cartoon editor, whose own drawing ability is just a shade worse than these others. There. I think that’s what I really mean. And now we can rejoin our garrulity at exactly the place where its irrepressible flow was interrupted.

HEREIN, CHAST GETS the first 4 pages of “The Funnies” section. The cartoon section that is the heart of the “cartoon issue” is thereby kicked off by lame drawings. Four pages of them. In person, Chast is a very funny lady; she was one of the speakers at the OSU Festival of Cartoon Art last month, and she was lively and thoroughly engaging with wickedly perceptive comments on both the world at large and her cartoony version of it. Not at all the wizened maiden aunt in a shawl sort of personality her cartoons lead you to imagine. Two of the cartoons in “The Funnies” are treated with the kind of disdain for visual art that suggests the editors don’t really want to do a “cartoon issue” at all. These two drawings are printed straddling the gutter, which means that parts of each drawing are obscured, tucked into the magazine’s binding in willful disregard for the cartoonists’ having drawn them the way they did because they thought the entire drawing, including all its parts, should be viewed. From the editors’ perspective, the cartoonists were obviously misguided in this infantile conviction. Considerations other than artistic reign in other departments of the magazine—on the cover, for instance. The mailing label that sends each week’s issue unerringly to subscribers is pasted on the cover art, defacing it. The magazine pays great sums for the art that decorates its covers (in 2004, Eldon Dedini noted that he could make $4,000 for a cover drawing), but then defiles it by laminating a foreign object onto it. In one memorable instance, a drawing by Sempe of the interior of a gigantic theater with an orchestra on stage and a single diminutive individual in the audience, the label was pasted over the person in the audience thereby obliterating altogether the humor, which rested entirely on the contrast between the tininess of the only patron in the midst of the vastness of its ocean of seats. Seized every once in a while by a nearly uncontrollable sense of outrage at this kind of abuse, I have occasionally written the art director, Francoise Mouly, to urge that if the label cannot be moved to the back cover (a maneuver that the Post Office doubtless wouldn’t object to), then at least use an adhesive that permits a subscriber to peel the label off in order to behold the cover art in a wholly unblemished state. As it is presently, if you peel off the label, you take part of the artwork with it, as you’ll see in a trice. I met Ms. Mouly at the OSU Festival and asked about the label. Her response revealed that the label has been an issue at the magazine for some time: I’m not the only reader whose artistic sensibilities have been offended. But since the capacious machinery for applying the mailing label has been set up for several light years and admits of no tinkering whatsoever, nothing, she averred, can be done about the desecration. We can put a man on the moon, but we can’t retool the mailing label machine. Too bad. Sad. The

“cartoon issue’s” cover is more cartoony than the usual cover art, as you can

see nearby. Brunetti has committed this kind of “art” before, and he’s about to do it again on the cover of Marvel’s Strange Tales II No. 3, as we can see in the other visual aids assembled near here. Brunetti, who teaches courses in design, illustration and the graphic novel at Chicago’s Columbia College, is an unusually articulate and observant practitioner of the arts of cartooning; he has written a book, Cartooning: Philosophy and Practice, which is due in the spring, and I’m looking forward to reading it. But I hope he gets the spheroid phase of his cartooning out of his system before committing too much more of it. Chris

Ware performed a similar exercise with tiny circles for the cover of the

June 14-21 issue of The New Yorker, the Literary Issue. His usual

drawing style, which also has a ruler-and-compass aspect, I like better despite

its wallpaper effects. The kitchen scene of another of his New Yorker covers

was attached in publication to a fold-out two-page comic strip that exploited

the traditional grid layout of comic book pages by treating the pages like a

board game. Fascinating stuff but hardly hilarious. Then again, I don’t think

Ware aims to be comical: his artistic intention is to exploit the form for his

own amusement—and ours, mild though it may be.

SOME OF OUR MORE EXCITABLE COHORTS call Brunetti’s and Ware’s spherical mannerisms “minimalist art.” Giving this style a name imparts a measure of status and dignity. But it’s only marginally minimalistic as perpetrated by Brunetti amd Ware. At your elbow now are some examples of genuine minimalism: Jim Ivey’s caricatures (followed by a page from his sketchbook); Mark Tonra’s short-lived comic strip spasm of graphic brilliance, Jimmy; even, just under Jimmy strips, one of my scribbles, but most certainly, Tonra’s other short-lived comic strip (circa 1997), On Top of the World, about life in a prison.

The ostensible stars of OTOTW are two convicts, Mugs, the little guy with a Napoleon complex, and his humble and resilient cellmate Knuckles, the big guy. The prevailing plot is their indefatigable engineering of an escape that is usually foiled. But Tonra was canny enough to know that a little of that goes a long way (albeit, not much beyond prison walls), so he cast the strip with an assortment of personages whose interests and assorted afflictions would provoke gags of the non-escaping sort. They are pictured, left to right, immediately below the OTOTW visual aid: Knuckles and Mugs, the foppish warden, Lackey (a guard), Princess the Warden’s daughter, Cozzer Swindle (Mugs’ irrational uncle and overconfident attorney), Ma (Mugs’ pugnacious and protective mother in deep denial exceeded by a mother’s pride), Kappy (the oldest living Civil War veteran in captivity), and Noozy, tattletale and confidant—a street-smart ankle-biter with a thirst for nickels. Ivey and Tonra are assuredly minimalists. But not so much Ware and Brunetti. They’re practitioners of geometry, not drawing. Possibly my antipathy towards stick-figure minimalism is prompted by too much stick figure shtick these days. Not only is there too much of it, but it’s now being treated as an artform, a grievous insult to any kind of artistic sensibility on the sidelines. Stick figure artistry (see how terrible that sounds?) is more in evidence online than in print, but this primitive visual form is starting to seep into books. From explosm.net, Cyanide & Happiness has morphed into a print volume, followed, with unseemly haste, by Ice Cream & Sadness. I must admit, however shamefacedly, that the drawings by Kris Wilson, Rob DeBleyker, Matt Melvin, and Dave McElfatrick are a little more persuasive than many other manifestations of the mannerism: the figures look like scraps of cloth hanging in a closet, which gives them at least weight. Besides, in our proximate example (next up), the toilet is perfectly rendered in a nearly realistic way. Another

practitioner of a slapdash minimalism that approaches stick figuration, Eric

Kim, has earned my grudging admiration by adapting all 36 of Shakespeare’s

plays to two-panel narratives in an 88 6x6-inch page paperback entitled, strange

as it may seem, The Complete Plays of William Shakespeare, merely $9.99

from inkskratch.com (with two k’s). No lover of the works of the Avonic Bard

can afford to deprive himself for long of possession of this masterwork. I made

some gestures at a review in Opus 265; since then, I’ve acquired my copy of the

tome and can show you two of Kim’s adaptations, Taming of the Shrew and Lear. Enjoy. And if you think this treatment of the Bard is a desecration,

remember what ol’ Willy Wagstaff himself said: “Brevity is the soul of wit.”

And shtick figuration is the tool of nits.

A FEW MORE

pictures before we depart the premises of The New Yorker. Interviewed at the blog.CartoonBank.com, Katz said he taught himself to draw by copying the Ninja Turtles and got into trouble in the third grade when he drew an erotic scene with the turtles. He pitched some cartoons to Mad while still in high school but didn’t sell any. At Harvard, he worked on the storied Harvard Lampoon, where he met Zach Kanin, also destined to be a New Yorker cartoonist. After college, Katz went to Los Angeles, thinking he could write for television but ending up writing for the Internet instead at comedy.com. He admits to making “a lot of YouTube videos that are now a source of great embarassment to me. Most of the videos involved eating pizza. They would pay for our props, so we always worked pizza into every video so we could get a free meal.” Then Kanin told Katz that Mankoff was looking for an assistant at The New Yorker and Katz applied and got the job, which was mostly sorting out the thousands of submissions for the weekly cartoon captioning competition. It was a privileged position: he sold his first cartoon after only “several months” of submitting; most neophytes submit for so many years that they are no longer neophytes by the time they’re published. Another

signature that showed up about the same time as Katz’s is “e flake,” which

stands for the unlikely name “Emily Flake.” Asked if that is her real

name, she said: “All too real, my friend, all too real.” When not doing cartoons for America’s most sophisticated weekly magazine, Flake does them for alternative weekly newspapers, usually in the form of a comic strip called Lulu Eightball. Flake calls herself an “illustratrix.” She explained it to fellow New Yorker cartoonist Drew Dernavich, who interviewed her in July 2008: “I hit upon ‘illustratrix’ because technically it just means ‘lady illustrator’ and I thought it would be interesting and memorable. Same reason I like to show up for portfolio reviews bleeding from the eyes, say, or speaking in tongues.” You can tell right away that this Flake is one tough pastry. She got into cartooning, she said, “because when I shoot for serious, I hit maudlin, and things get uglier from there.” She doesn’t consider cartooning an art or a craft necessarily. “I consider it a tasty, life-giving millstone hung round my neck. A beloved millstone. Also, maybe a little something like necromancy.” Occasionally, the editors of altie weeklies take umbrage at some of the Flakey language in her cartoons. “My editor in Birmingham sometimes objects to quirks of accent or wording, questioning my use of the word ‘turlit’ for ‘toilet’in a panel featuring pantsing; and the Charlottesville paper recently declined to run a particularly filthy strip called ‘X-Rated Acts of Tenderness.’ And I have edited myself on a couple occasions, substituting a rash gag for a harelip joke and not using the line ‘The only Chinese things I want right now is rocks and pussy.’ But generally speaking,” she concluded, “I am given a great deal of leeway. I am a lucky girl.” Operating, I suppose, from the aged axiom that “the style is the man” coupled to another equally hoary myth, “you are what you eat,” Flake believes certain foods make her funnier. “Chocolate cream pie helps me to be hilarious whether I’m eating it or throwing it,” she explained. “Does bourbon count as a food? What about nitrous?” What about coffee? “I take it black as my heart,” she cooed, “and bitter as my soul.” End of interview. The other new style I’ve noticed lately—in at least one cartoon that was published in the September 27 issue—is signed “esmay.” Which could be “E.S. May.” Or “E. Smay.” But is probably Esmay. About him (or her) I have yet to discover any biographical or professional fact beyond the bare appearance of his cartooning style, which seems grossly cross-hatched with nicely definitive outlining. One of the best things in the “cartoon issue” is the series of color spots by cartoonist Charles Barsotti. The New Yorker has always run tiny spot drawings by anonymous artists to break up the dull gray monotony of its columns of type, but a few years ago, the magazine began featuring the work of a different artist in each issue, using a series of spots by the same individual and crediting that person on the table of contents page. Sometimes the spots even depicted a sequence of actions or incidents. This time, the spot artist is Barsotti, a graduate of Hallmark Cards and once cartoon editor for the Saturday Evening Post, which folded in January 1970. He says William Shawn (The New Yorker’s second editor, who succeeded founder Harold Ross at Ross’s death) and cartoon editor Jim Geraghty “unfolded” him, and he became a contract New Yorker cartooner. He also tinkers with design, as you can tell from his spot drawings parading across the page under Flake and Esmay. Despite all the carping herein about The New Yorker’s imperfect realization of my hopes for a “cartoon issue,” I rejoice at the magazine’s annual tribute to gag cartoonists and their artistry. As you can tell, my disappointment masks a fervent hope for better and better, but at least we’re starting at pretty dang good.

IN SHARP CONTRAST to the festive celebratory aura festooning The New Yorker, in Playboy, the other last great outlet for magazine cartoonists, we have what might be the prolongation of a dirge. Without the equivalent of the Cartoon Bank, Hugh Hefner’s skin mag is desperately flailing about to survive an ongoing financial crisis. A recent report has Hef selling at auction quantities of the original art produced for the magazine over the years, but “cartoon bank” this is not. It’s an auction—a sell-off— not a bank, not a savings and loan institution; and the artwork consists, I gather, of the original illustrations for short stories and articles, not, yet, cartoons. I’ve been tracking Playboy’s declining deployment of the cartoon artform over the last couple years. But when this year’s December issue arrived, I was momentarily cheered: after a year of comparatively thin issues (averaging 120-130 pages each), the anyule Christmas issue, usually the magazine’s next-to-biggest issue of the year (the biggest being January’s, which comes out about Christmas time), toted up 198 pages. “Big” by present-day Playboy standards. And there seemed to be quite a few more cartoons than have lately been offered in the typical issue. A substantial proportional increase in full-page cartoons: a total of only 7 but that’s a leap from November’s 5 and just 4 in last May and June. (Not including Olivia’s pinuptoon.) And the smaller dimension cartoons numbered 18, including a 2-page spread of 7 cartoons from “Christmases past.” That’s 25 total, compared to 14 in November, 12 in May and 20 in June (including 8 John Dempsey reprints in a 2-page spread). But the accurate measure of cartoon usage is in the ratio of cartoons to total pages in the magazine because the number of cartoons is a factor of the number of pages (in theory, the more pages, the more cartoons; and vice versa). The ratio in December’s issue is 1/8, including the cartoons from Christmases past; in November, 1/10; in May, 1/11; and in June, 1/10.5. In other words, in December, mathematically, we could encounter a cartoon every 8 pages; in November, every 10 pages; etc. So December’s issue, even considering the greater page count, was friendlier to cartoons than November’s or May’s or June’s. But this December is a far cry from the colossuses of bygone Yuletides: in 1967, the December issue numbered 320 pages; in 1972, 346 pages (both with a concomitant compliment of cartoons). This December issue contains other matters of interest. First, Olivia’s pinuptoon is Bettie Page, a nostalgic homage, no doubt, to the iconic pin-up’s January 1955 appearance, her first in the magazine, wearing an extremely abbreviated Santa costume (just the cap) for the “Christmas issue.” And one of the full-page cartoons is one of the late Rowland B. Wilson’s, not the best of his work but better than nothing and a pastel reminder of yesteryears. Don’t know if it’s a reprint, but I suspect not; it’s probably culled from Playboy’s extensive inventory of purchased cartoons not yet published. Staying in the cartooning arena: you can obtain a daily desk calendar of reprinted Playboy cartoons—that’s 365 cartoons, one a day, for 2011; available online at theplayboyshop.com. That’s in addition to the magazine’s other calendar, the customary wall hanging calendar of Playmates past, which is also touted in this issue. Beyond cartoons, we find several signs of Playboy seeking new sources of revenue by branding products other than barenekkidwimmin. Playboy cigars and fragrances are advertised; and we are alerted to a forthcoming line of Playboy booze—gin, whiskey, etc. Each product getting at least a lavish, full-page ad; the liquor, two pages for each kind. But there are also signs of scrimping and saving. As every accountant knows, the bottom line can be improved in two ways—by increasing revenue and/or by reducing expenses. Playboy has been systematically cutting costs by reprinting the treasures of the past. In this issue, an extensive 8-page section of pictorial pulchritude from issues published in the 1980s is thinly disguised as a review of the decade: some of the tinier photos depict such eminences of the period as Ronald Reagan, ET, Prince, Edwin Meese (“Reagan’s moral paladin,” who supervised a study of the effects of pornography on Americans, producing an illustrated report as pornographic as the material it studied), and the advents of AIDS and Mel Gibson. But the bigger pictures on each page were of the Playmates of the period. The oddest aspect of this homage to the past is the accompanying article by Neal Gabler. Entitled “Why We Love the 80s,” the piece never mentions or even alludes to the dozens of pictures of naked women that we would expect this text to be discussing, given its proximity and title. Instead, Gabler conducts a screed in prose: “The 1980s ... was the most schizoid of the decades—both boom and bust, both libertine and churchy, both full of bluster and full of doubt—and in retrospect it seems less a distinct era than a 10-year exercise in willful obliviousness manifested largely as hyperbolic rhetoric and gaudy exhibitionism ... all posturing and profligacy....” After that introduction, Gabler cherry-picks the decade—the rise of the religious right, rampant drug use, death of John Lennon (“closed the door on the 1960s with its remnants of idealism and hope”), Madonna (“the decade’s muse,” her “material girl proclaiming her sex wasn’t for free and it wasn’t for fun: it was a commercial transaction just like everything else in the decade”)—creating with soaring rhetoric and searing examples support for his argument about the distinctive “personality” of the period. But as much as I admire the pyrotechnics of his styling, what he finds distinctive about the 1980s, I find peculiar to most of the second half of the century. Ironically, this pictorial and verbal homage to the 1980s perfectly embodies in the abstract the essence of the Playboy publishing philosophy: for the sake of social and marketing acceptability, surround pictures of unencumbered feminine embonpoint that are the real attraction of the magazine with a smoke-screen of sober texts on cultural issues that completely ignores (or pretends to) the magazine’s raw appeal. The cover and the front sections of the magazine have lately made Playboy indistinguishable from laddie magazines like Maxim, a market niche Hefner is clearly hoping to gain a share in, but with the interior pages, Hef is proclaiming Playboy’s difference with brash excess. In addition to the 8-page section devoted to photographs of the bare-ass ladies of the 1980s, this issue offers two photo essays examining the unadorned female epidermis plus the usual monthly Playmate: 6 pages of the latter and 8 of Kendra Wilkinson and another 6 of a woman channeling ballet in the buff. Not counting the occasional nude in the customary year-end survey of “Sex in Cinema,” the Christmas issue of Playboy declares its unrivaled place in publishing history with 28 pages of pictures of ecdysiastic wimmin. Altogether, that’s 14% of the magazine devoted to the distaff birthday suit. No laddie mag manages a similar feat. If nudity will secure Playboy a niche in the voyeur market of today’s men’s magazines (as it did in bygone times), issues like this will do the job. Speaking of calendars, which we were a few tirades back, I have been a votary in the annual ritual of the pin-up calendar since before I remember. I no longer buy Playmate calendars, but I still admire them, sometimes in an envious mode. A dozen years ago, I gave in to what had become a yearly temptation—to do a pin-up calendar of my own devising. The difference from the usual run of women in the buff is that my barenekkidwimmin are cartoons of lascivious ladies, accompanied by representatives of the avian and amphibian communities (a crow and a frog) making snide remarks about the displays going off all around them. I committed this spasm of self-indulgence with a calendar for 1997 and then reissued it for 1999. Whilst unpacking a box the other day, I ran across what remains of my experiment, a dozen or so calendars for the last year in the millennium. I will reluctantly part with them for merely $15 each (including p&h). Here’s a sample of two of the more prominent months and an order blank that you can print off and send to me with your check. Do not dawdle: only a few copies of this cultural landmark are left.

WITHOUT WINDING UP ANY SORT of Death Watch, I’ve been keeping a close eye on the cartoon content of Parade, the newspaper Sunday supplement magazine, which, until the last few months, offered a feature called The Cartoon Parade, usually 3-4 cartoons per issue. Recent issues, however, have seen the number drop precipitously to one. But November 28's issue was back to 3. Alas, they’re tiny—about 2x2 inches, running down a narrow column instead of splendidly across the top of the page.

PERSIFLAGE AND BADINAGE Jane Fonda on relationships: “It doesn’t start with love, right? It starts with sex and grows into love.” A new trend, no doubt. All this time, I thought romance began with lust. Raw realism. “Take another drink and walk a little slower: life is not sweet, but it’s nourishing.”—Larry Calloway “Never ascribe to malice that which can adequately be explained by incompetence.”—Napoleon ***** Surely, you jest. Yes, I jest. And don’t call me Shirley. In fond memory of Dr. Rumack (Leslie Nelson)

RAGHEAD RITUALS AND A NEW REVOLUTION Ted Rall, gadfly columnist and raging iconoclast cartoonist, lately of the wilds of Afghanistan’s fly-infested deserts where he spent the month of August with two other crazed cartooners, Matt Bors and Steven Cloud, is back to plague his country with the Truth As He Sees It (several acres of which we share as common ground). In his journalist garb, Rall took to the pages of the venerable Editor & Publisher to assail the highly dubious practice of embedding reporters in Iraq and Afghanistan. Embedded reporters can’t report on Afghanistan, Rall said: they report only what they see “through the carefully monitored lens of the U.S. military.” Traveling with soldiers, they become battlefield buddies with the soldiers—a plus: they see the horrendous difficulty of the military assignment and ordinary acts of heroism; but they don’t talk to Afghans—a distinct minus: they can scarcely report on the status of the military mission, which is to win the hearts and minds of the country’s citizens, if they don’t talk to any citizens. Traveling with the troops is supposed to make a reporter safer. Not so, Rall said: “More journalists have gotten killed by IEDs and crossfire while traveling with U.S. and NATO forces than going it alone, independently.” True, perhaps; but since almost all reporters travel with the military, comparing their fate to that of the few unescorted journalists is bound to produce just the statistic Rall reports. “Embedding is a dubious idea at best,” Rall said. “It magnifies the media’s inherent bias for the fighting men and women from ‘their’ side, and it exposes journalists to the accusation that they are shills for the occupation. ... Important stories—those that don’t involve U.S. military operations—never get covered.” The embed program is not just bad journalism: it’s bad for the allied mission itself. The Rall trio stumped the country unembedded. Unlike embedded reporters, they saw and talked with Afghans. “Not talking to Afghans is part of the reason the U.S. military is losing the war,” Rall said. “They don’t ask Afghans what they want. We did. Their answer was usually the same: ‘Please, no more soldiers. We don’t need them. We need help.’ By help,” Rall concluded, “they mean reconstruction and jobs programs.”

RALL AND HIS COMPANIONS went to Afghanistan because they wanted to see whatever it was that the embedded journalists weren’t seeing. Rall had been before: he’d gone to Afghanistan in the fall of 2001 to report on the invasion. It was dangerous then. “I was one of 45 members of what we loosely called a ‘convoy,’” Rall said, “—we went in together, and when rogue Northern Alliance soldiers began hunting us down to kill us, we fled together. During the three weeks in between, we were on our own.” And he and Bors and Cloud were on their own this time, too, for most of their time in country. For a month, from dingy hotel rooms, they drew cartoons about what they saw and heard, and when they got back, Rall and Bors were interviewed by various news media, including Funny Times, which, otherwise, stays focused on editorial cartoons, gag cartoons, and humor columns. Asked what he thought was the most important thing about Afghanistan that Americans should know but weren’t hearing about, Rall said: “There is lots of reporting from Afghanistan, but it’s so obsessively focused on U.S. troops that it is effectively useless. Oddly, the war is irrelevant to the lives of the Afghan people. It’s possible to spend day after day, even in major cities, without ever seeing a U.S. or NATO soldier. Most of the battles occur in remote areas near the Pakistani border. And there are virtually no independent reporters raveling unembedded. “The main takeaway,” he continued, “ is that the U.S. isn’t even trying to provide basic security for the Afghan people. American forces have the technology and Afghans have the intelligence necessary to stop the neo-Taliban and their new criminal gangster allies. [See R&R, Opus 267.] But they aren’t lifting a finger to do so. As a result, the Afghan people are being terrorized—and not only by them, but by the Afghan National Police, who are hopelessly corrupt, underpaid, and under-equipped.” Asked about the Afghans’ attitudes towards Americans, Bors answered: “Afghans love Americans regardless of what they think of our government. Unlike many Americans, they are able to separate people from the actions of their government, probably as a result of a lifetime of repressive and corrupt governments that never paid attention to the people’s needs. They assume it’s like that here”; i.e., Americans, like Afghans, are “different” from their government. After his experience in Afghanistan, would Bors venture again into such an environment? “Yes,” he answered promptly. “I’d like to visit other war-torn hell holes that my country has invaded and report back on what I see..” Rall was asked what changes, if any, have taken place in Afghanistan since his 2001 trip. “Infrastructure is a big change,” he said. “Back in 2001, it was the 14th century: no electricity, no food, no water, no phones, no businesses, no nothing. Donkeys were the principal form of transport. Now there are cell phones, cars, and the donkeys are gone. Electricity four hours a day might not sound like much, but it’s enough time to charge your devices. Technology makes it easier for travelers, and also for Afghans. I know that their lives have improved in that respect.” “And yet,” Rall told Michael Cavna at ComicRiffs, “people are pessimistic. Mostly, this is because the U.S. and its Allies got started late. ... Nothing substantial got started until 2005. By then, it was too late for the U.S. to make a good first impression. Also, Afghans think we haven't done nearly enough: we're a superpower, so why haven't we been able to make more happen faster? Also, the security situation has deteriorated.” In the Funny Times interview, Rall continued: “The high spirits and hopefulness I saw in 2001 are gone. They know the neo-Taliban will be running things next year or by 2012, that the rapists will be ruling the nights again as they did pre-1996. Afghans are staring into the abyss. They’re scared and angry and know the future looks bleak.” The neo-Taliban, Rall said, “are the madrassa kids [graduates of fundamentalist religious schools], alienated twentysomethings looking for a mission in life. Unlike the old Taliban [which were motivated by religious beliefs], they have little sense of destiny or religion. They’re amoral and dangerous.” (See Opus 267 for more of what Rall said about the “new” Taliban.) Yes, they saw Taliban. “We frequently passed through areas controlled by the Taliban,” Rall said. “It might be more accurate to call them ‘not controlled by the government.’ The Taliban come and go in areas with low government presence. Anyway, we talked to people I’m pretty sure were sympathetic to or were actual members of the Taliban.

ASKED WHAT WERE THE SCARIEST moments of the trip, Bors quipped: “Using the bathroom after Ted.” But he went on to recall the night that they were “unceremoniously kicked off” a reconstruction base where they’d settled in for the night. It was the only time the cartoonists were being “protected” by armed guards. Said Bors: “They drove us in a convoy of hummers to the local, bullet-riddled hotel in the middle of the night, alerting the entire town to our presence. Las they drove us, the only thing I could think about was how ironic it would be to get IED’d during the only drive we took escorted by armed guards.” The cartoonists had decided to spend the night at the reconstruction base “on a lark,” Rall explained when talking with Cavna. “They agreed to let us, but then their commanding officer ordered them to kick us out because we weren't accredited with the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF). In the middle of the night! You have to understand: there are many Afghans who have never been outside at night. The night belongs to [violent criminals]—and now the Taliban. Instead of being low-key, they drove us, lights flashing, in armored vehicles into town. We thought we'd be IED'ed. Then, upon arrival, the soldiers, bristling with weaponry, delivered us to a hotel with no security whatsoever ... full of tough-looking Afghan men breaking fast [it was Ramadan]. We would rather have walked in. Also, couldn't they have waited until morning? It was irresponsible; they endangered our lives as well as their own. It merely confirmed my belief that dealing with the authorities only causes trouble. Reporters should have nothing to do with the military.” “There was nowhere to go,” he went on in the Funny Times interview. “We were stuck there for three days, knowing that we could be kidnaped at any moment. It was low-grade terror. We went about our business and hoped for the best. Worrying wouldn’t have accomplished anything, so we didn’t.” The funniest thing that happened to them was in a hotel room in Chaghcheran, Bors said. “We were attacked by at least 50,000 flies. I might be exaggerating slightly there, but not by much. They flew in our eyeballs, flew in our ears when we were trying to sleep. Eventually, we were driven mad and started laughing hysterically and making up crazy stories about the flies, kind of like how crazy people in insane asylums act.” He paused. “You had to be there,” he said. “But I’m glad you weren’t.” Rall chimed in: “The bargaining was always the craziest and funniest thing ever. In Afghanistan, a deal is never a deal. You settle on a price for a good or service—a meal, a taxi ride, hotel room, whatever—and you shake on it. Then, after you receive it, they demand twice as much as you all agreed. When you balk, they yell at you until you pony up more dough. What’s funny is that, by American standards, they have no leverage. After all, you’ve already eaten the meal or stayed in the room or been delivered to your destination. And you’re leaving town. And yet, it works. It drove Matt and Steve crazy. I thought it was funny watching their response to this perfidy.” “Afghans view you as an ATM,” he told Cavna. “But it's worth it. And for every dishonest Afghan there's one with fierce integrity.” Said Cavna: “You went there largely to report the story of the Afghan people, away from the war zones—how they live, how they cope. Do you feel you were able to ‘get’ that story? That you had both sufficient time and access?” “The best you can do is scratch the surface,” Rall said. “Which we did. I feel like we got the story as well as anyone could. Certainly we did a better job than the embedded reporters who spend all their time on base shopping at the PX. No one talks to them at all. But I could have used much more time. ... There's never enough time. Still, I'm fairly confident that I have a decent understanding of what's going on and how Afghans see things at this, the beginning of the end of the U.S. occupation of Afghanistan.”

IN 2001, BEFORE AND AFTER going to Afghanistan, Rall maintained that one of the reasons the U.S. invaded the country was to secure the safe installation of a proposed pipeline route through Afghanistan from untapped oil fields in Kazakhstan north of Afghanistan to the port of Karachi in southern Pakistan. And so we invaded Afghanistan instead of, say, Pakistan or Tajikistan or southern Kyrgyzstan—where the training camps for radical guerilla outfits like Al Qaeda were actually located. And once we’d ousted the Taliban, we installed Hamid Karzai as president: Karzai is rumored to have once consulted with (and perhaps still does) Unocal (Union Oil Company of California, a subsidiary of Chevron), the oil giant whose interests we were expected to advance with that pipeline (or, if not Unocal, Karzai may have consulted for one of the many oil companies that are part of the CentGas consortium sponsoring the Trans-Afghanistan Pipeline project). So one of the things Rall wanted to know was how work was progressing on that pipeline. “Begun in 1995,” Rall said, “this oil and gas scheme got a lot of attention, particularly in Michael Moore’s ‘Fahrenheit 911.’ Has construction begun? No reporter has tried to find out.” But Rall did. He went where the pipeline should be and found no evidence whatsoever of any construction. “They never broke ground,” he wrote in E&P. Still, Rall doesn’t think his explanation for the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 is wrong. “At the time,” he wrote me when I asked about it, “I said that the pipeline was either the reason or one of the major reasons for the invasion. I didn't discount geopolitical considerations such as intimidating Iran, India, Pakistan and China, not to mention the fact that the war was a dry run for the main event, the invasion of Iraq. I don't think I was wrong. Asian news outlets are still full of stories about the presidents of Turkmenistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan meeting to discuss the pipeline. Major banks have signed on. Roads have been built to service this thing. So the pipeline isn't some wacky conspiracy theory. But it is also true that construction has not begun—and likely never will. (Which, by the way, I predicted back in 2001 as well.)” Pipeline or not, Rall’s cartoons and those of Bors and Cloud reveal a good deal more about Afghanistan than the so-called “news” media reports we’ve seen. Rall’s cartoons will be published in a book from Hill and Wang in the fall of 2011. Until then, here’s a short gallery of his Afghanistan work and that of Bors and Cloud.

MEANWHILE, Rall, having just completed one stunt, is embarked on a new one: his latest book, The Anti-American Manifesto, is stirring up the natives. Rall, fed up with our nonfunctioning political machinery that cannot grow out of its current bitterly partisan mode, suggests it’s time for a revolution—not a tea party, but an outright revolution, which, he insists, is the only way to bring real change to the American political system. We don’t need to merely throw the rascals out by voting against them: we need to storm the citadel and shut it down and put something better in its place. At least, I think that’s what he’s saying; I haven’t read the book or, even, seen a copy, but I’ve been watching Rall being interviewed and seeing what his cohorts in the editorial cartooning fraternity are saying. At RussiaToday on YouTube, Rall said: "The Anti-American Manifesto is addressing the fact that neither the Democrats nor the Republicans are able or willing to address the biggest problems facing the U.S. today, which are the economy, the environment, healthcare and the wars. And now you have to ask yourself as an American do you want to tolerate the system that is unresponsive and not going to go anywhere, or do you want to change it. The Anti-American Manifesto is not anti-American: it is anti the American government, or more specifically, this American government. We can do better and that's what I want to do." On Dylan Ratigan’s MSNBC show, Rall posited that political change comes about through one of four ways: political process, bond and insurance markets (essentially, an economic revolution, I gather), passive resistance, or violence. Violence, he said, is the last resort. But, he continues, “no meaningful political change has ever taken place without violence or the credible threat of violence.” The political process has been thoroughly discredited in recent years; its been established as completely nonfunctional, so it cannot achieve change. The money markets have bought and paid for the government and both are co-conspirators in devising ways for the public at large to support the political and financial moguls but not the middle class or anyone else in the lower tax brackets. (I’m guessing that’s about what Rall says in his book—judging his previous diatribes and the current screed.) Yes, passive resistence would be nice, he admits: “If you could get everybody to stop paying their mortgage, say, it would work. But you can’t even get everybody to stop littering.” That leaves violence. Or the credible threat of violence. “It’s up to the people,” Rall said, and then he quoted John Loche, who maintained that the people have “an obligation” to revolt when government fails. And our government, Rall would say, is failing. If Rall is seen as advocating violent overthrow of the government, he can get himself into pretty deep hot water with the feds. I asked him if the FBI has been knocking on his door lately, and he said: “Aside from the funny clicking sounds on my phone, I haven't heard from them.” And then he remembered: “But those clicking sounds were there before the book.” Without having, yet, read the book, I can only suppose Rall dodges the issue by couching his argument as a metaphysical contemplation rather than as a program urging action. We get some hint of the way he may be going in his explanation to Ratigan of his choice of title for the book, The Anti-American Manifesto: “That’s what everyone will call it anyway,” Rall said. He just got there first.

NBM AND THE EUROPEAN CONNECTION: PART ONE, PAPERCUTZ In one of my earlier lives, I went down to the sea and ships with Johnny Masefield, who knew what we’d find there well enough—the flung spray and the blown spume and a vagrant gypsy life where the wind’s like a whetted knife and the best we could hope for was a merry yarn from a laughing fellow rover. And I spent three years sailing the deep blue Mediterranean, bounding over the heaving main (or vice versa) and occasionally putting in to port. We were often in Cannes, but for a few days in the winter of 1961-62, we anchored off Marseilles. The horizon seaward was spiked by the tower of the famed Chateau d’If, the fortress island prison from which Edmond Dantes escaped in a canvas wrap to become the Count of Monte Cristo. Otherwise, Marseilles was a colorless port, a dull gray business-like sort of place compared to our more frequent port-of-call, the frivolous sunny recreational Cannes with its white sand beach, bikinis, storied Carlton Hotel, and palm-lined Boulevard de la Croisette. But we went ashore whenever we could anyhow, regardless of the clime or ambiance. A drink’s a drink for a’that, Robbie. One day when wandering by myself along the waterfront, I came to a book shop on a side street corner. In contrast to neighboring windowless stores, which sealed themselves up against the impertinence of the prying eyes of passers-by, the book shop’s outward walls were all window, and the lighted interior made the place glow warmly, beckoning rather than foreboding in that otherwise gray neighborhood under equally gray skies. I don’t speak or read French very well (despite having passed a test on it for some of the initials after my name), but I could tell it was a book shop: looking in through the window, I saw little else but books. So I went in. There, heaped up on a table near the window, were piles of books with cartoon characters on the covers. Thick books, two inches of 9x12 inch pages. One of the words on the cover was “album”; another was Spirou. Opening one, I could see that each of these tomes bound together a dozen or more previous issues of a magazine. Flimsy but glossy paper. And each issue of the magazine Spirou included several full page comic strips. Different strips. Detective strips, cowboy strips, Arabian flying carpet strips, little kid gang strips, serious seafaring strips, strips about pilots and soldiers, animals and knights in and out of armor, and the French king’s musketeers. Most of the strips told stories serially, one or two pages in each issue of the magazine, continuing in subsequent issues. (Later, I learned that after a story had concluded, the serial pages of a given title would be bound together in a single book publication, called an “album,” giving the term a second meaning, the one that endures today, the first usage having fallen victim to history). I couldn’t read a word in the speech balloons, but I bought a half-dozen of the bound-together collections of back issues of Spirou magazine, selecting them at random from the piles, and carried them off. Back aboard ship, I thumbed my way through each of the albums, admiring the drawings in the strips, the proliferation of styles—some realistically rendered; others, cartoony. But even if the people were bigfoot caricatures of the human [sic] sapiens, the backgrounds were copiously detailed—still without being photographically illustrative—lending to the doings depicted an undeniable authenticity, the kind of faux reality upon which any self-respecting visual art depends. Here, just at your elbow, are some of the things I saw and studied, a glorious profusion of antic energetic styles.

A few years later, after I’d escaped the nautical life (it was, after all, but a fleeting thing) and returned to the drawingboard, the Spirou albums became part of my studio morgue, the visual reference file that any cartoonist keeps close at hand. And when pawing the albums’ pages to assemble the gallery of samples we’ve just wandered through, I renewed my acquaintance with some of the pictures I’d copied pieces of—a candelabra with candle-wax dripping, the folds of a drape suspended on a bar over a doorway. And I remembered being intrigued but baffled by the miniature blue characters called “Schtroumpfs” who had cropped up en masse in a strip of the medieval adventures of Johan and Pirlouit. If the strip had been drawn in a realistic manner, the arrival of the Schtroumpfs would have fractured the aura of authenticity, but Johan and Pirlouit and their friends and foes were rendered as cartoon characters, not real people, and so the Schtroumpfs did no violence to the ambiance of the strip. These dwarfies with their cone-shaped hats (known as Phrygian caps) multiplied in the pages of Spirou, showing up on game pages and in a mini-comic book bound in the middle of some issues. (Pull out the pages and fold them twice, making tiny 4x6 inch booklets—miniature comic books of miniature people.) Years afterward, the tiny happily contented trolls immigrated to these shores, and they were called Smurfs; they proliferated briefly and then seemed to fade away. Or perhaps my attention was simply diverted elsewhere. The Smurfs were animated in movies and on tv, but never showed up in print, it seemed to me. In print, they existed only in my memory of those pages of the albums now stowed safely away in the subterranean depths of the Rancid Raves Book Grotto. So when Jim Salicrup, editor-in-chief at Papercutz, sent me copies of two of its newest series, I was all ears and rejoiced: here, at last, were the Schtroumpfs in print where I could watch them for long intervals, at leisure, rather than trying to appreciate their antics as they flickered too quickly by in their animated incarnations. The second book in the series, which appeared in my mailbox with the inaugural volume, rehearses the origin of the blue imps in Johan and Pirlouit. Finally, that mystery is solved! But it merely whetted my appetite to know more about the characters and their creator, who signed his work “Peyo.” So I looked him up in the Google caverns. You can do the same; but here are the high points of what you’ll find.