|

|||||||||||||||||

Opus 313 (July 18, 2013). Once more down the rabbit hole to continue our Annual Open Access Month: for all the month of July (starting with Opus 312 even though it’s dated June 26), the online magazine Rants & Raves, as well as archived R&R and the entire Hindsight archive—thirteen years of history, lore, reviews and commentary—is open to non-$ubscribers in the hope that they will be so thrilled with what they find that they’ll $ubscribe. Join the deliriou$ly happy throng. Our current posting focuses on editorial cartooning—the annual editorial cartoonists’ convention, Pat Oliphant, codes of ethics, plagiarism, no cartoons for NSA or Zimmerman, and Chuck Asay’s retirement. But that’s not all. We go beyond editorial cartooning to report on Uslan’s Shadow and Green Hornet and Neil Gaiman’s new Sandman, review Harold Ross and John Held, Jr.’s impact on cartooning, and play a comic strip word game. And more, of course—much more, all listed immediately below. This listing, by the way—in case you haven’t already figured it out—is to enable you to scan the contents of enormous postings like this one and pick the articles that interest you so you don’t have to scroll, paragraph after paragraph, through the whole enchilada to get to what you like. Here’s what’s here, then, in order, by department—:

NOUS R US Cartoons in Strife-ridden Egypt Odds & Addenda: Superman, DenComCon 5th, Sandy Eggo Con On Chuck Asay Retires (with Lots of Pix) Dick Locher, Sculptor

EDITOONISTS CONVENE IN SALT LAKE CITY Crowdfunding, Internet to Thomas Nast, Muhammad to Mormon Underwear Evening with Pat Oliphant Plagiarism and Code of Ethics Herblock Film Awards: Locher, Courage in Cartooning, Ink Bottle (RCH)

HAROLD ROSS & JOHN HELD, JR.

EDITOONERY Bert and Ernie at The New Yorker No One Stands for NSA? Or For Zimmerman? Ted Rall: Crusader with Feet of Clay

Rancid Raves Gallery

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Tundra Dennis’ Pledge Jivey Word Game

BOOK MARQUEE Neil Gaiman Brings Back Sandman Michael Uslan Brings Back the Shadow and the Green Hornet Kitchen Sink Returns

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Hawkeye and What Comics Can Do Fury’s Wars Gone By Ends

CODE OF ETHICS FOR EDITOONISTS Two Proposals

ONWARD THE SPREADING PUNDITRY Congress: Lame and Comatose Global Carbon Count Immigration Bill and Why No Path to Citizenship

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits CARTOONS ARE BACK ON THE FRONTLINES in Egypt, according to Jonathan Guyer at newyorker.com, who writes (in italic): From the day that Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi took office, on June 30, 2012, opposition cartoonists have been brazen in their attacks on him. Most newspaper editors refrained from mockery of Morsi's predecessor, Hosni Mubarak, during his thirty-year reign, but in the new Egypt, things are different. A law against "insulting" the President remains in the penal code, but illustrators unabashedly lampoon Morsi on a daily basis. Morsi is drawn as a cowboy, as Godzilla attacking Cairo's skyline, and, of course, as a pharaoh. He is a cleric in Muslim Brotherhood regalia. He sends a Tweet from his cell phone to the Egyptian people, as he sits on the toilet, pants dropped. He orders carryout: "I'd like the revolutionary platter…and hold the opposition." And those are just a few of the gems from dissenting newspapers. There is something distinctly Egyptian about cartoons; one researcher has even traced the art form to ancient hieroglyphs, which featured gags mocking the pharaohs. They were an important part of the 2011 revolution against Mubarak, and as cartoonists entered Tahrir Square, many saw their illustrations on placards. Some broadsheets publish as many as eight editorial cartoons on a given day. "Drawings reach people faster, are more direct, and reach a broader spectrum of people," said cartoonist Doaa El Adl. "Events happen very quickly, and the artist isn't supposed to explain events but is supposed to have a vision—and sometimes predict what might happen." "Before the revolution, we felt depressed, that things would never change, that we would die and the President will be the same," El-Adl told Guyer. "When the revolution happened we were a little surprised when we saw people in the street holding our cartoons. ... That's a big change." El-Adl is the most prominent woman cartoonist in Egypt, and she often addresses issues that most illustrators are afraid to touch, like the widespread practice of female genital mutilation. On display at newyorker.co is a selection of eight cartoons by six artist, chosen because of their audacity, their simplicity, and their punch lines. Said Guyer: “They capture the sentiments of a citizenry angered by a leader who has bounced from crisis to crisis without an inclusive and unifying vision for Egypt. (The same cartoonists, by the way, have drawn highly critical cartoons of opposition leaders, too). Thanks to the seemingly endless economic crisis and political conflict in the country right now, cartoonists might have more material than any time in Egyptian history. As eighty-seven-year-old cartoonist Ahmed Toughan—who drew under Nasser, Sadat, and Mubarak—told me, Morsi ‘is not lucky.’” In

the corner of your eye, we’ve posted one of the eight. Until lately, cartoonists at independent newspapers were not shy in depicting the excesses of the military; Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood appeared as bumblers. In recsent weeks, though, they have been supporting the military, which has arrested dozens of Islamists, with images of Brotherhood cadres armed to the teeth, defying military authority and inciting violence.

ODDS & ADDENDA AARP, the bi-monthly magazine for gaffers like moi, turned its attention, briefly, in the June/July issue to Superman, who, at 75, has been officially a candidate for membership in the Association for American Retired Persons for twenty years, but nobody noticed until now, the prompt being his 75th birthday. AARP listed “five things you never knew about Superman” (supplied by Larry Tye, author of Superman: The High-Flying History of America’s Most Enduring Hero), among which unknowns are: his middle name, Joseph; and his Social Security number, 092-09-6616. “The number actually belonged to a flesh-and-blood New Yorker, Giobatta Baiocchi, who had died a year earlier [before the 1966 issue of Action Comics that revealed the number] and whose relatives have no idea why his number was picked.” Neither do I, kimo sabe. And speaking of the Man of Steal, in the June 27 issue of City Weekly, columnist Bryan Young, reviewing the new movie (which he doesn’t like much), quotes the titular character in Quentin Tarantino’s “Kill Bill” on the Man from Krypton: “Clark Kent is how Superman views us. And what are the characteristics of Clark Kent? He’s weak. He’s unsure of himself. He’s a coward. Clark Kent is Superman’s critique on the whole human race.” Israeli authorities are expected to release on July 8 the Palestinian cartoonist Mohammed Saba'neh, 34, who has been imprisoned for five months apparently without charge. See Opus 308 for details. Other than those, we have no further information. Oooopsie: I reported last time that the Denver Comic Con registered 48,000; but subsequent information pegs it at about 61,000 (a conservative estimate, saith one of the con crew). Heidi MacDonald at PublishersWeekly.com repeats that number, and in a comparison to the populations of other cons, ranks Denver fifth largest (after, in descending order, San Diego, New York, Toronto, and Seattle. “Despicable Me 2" left “The Lone Ranger” in the dust over the Fourth of July weekend: according to studio estimates, the animated feature took in $82.5 million over the weekend and $142.3 million across the five-day holiday window; the legendary Masked Man did only $29.4 million and $48.9 million respectively. Jen Sorensen won the Robert F. Kennedy Award for excellence in journalism/editorial cartooning. This is her second “win” this year: she won in the Reuben editorial cartoon division, too. And last year, she was a finalist in the Herblock competition. TwoMorrows Publishing kicks off a year-long celebration of its 20th anniversary at the San Diego Comic-Con later this week. At its booth (1301), the publisher will offer a salivating 50% discount on most of its products. I’ll be sure to stop by. Yes, I’m goin’ to Sandy Eggo again this year, July 17-21. Wave if you see me awash in the flow along the eddying aisles of cosplaying humanity. Or visit me at the National Cartoonists Society booth, 1307-1309, Thursday, 3-5pm, and Saturday and Sunday, 1-3pm. Bud Plant will be exhibiting at the Con—his 44th consecutive year. He was there at the first one in 1970 “in the very dark, badly lit basement of the U.S. Grant hotel,” he said in a Toucan interview at comic-con.org. Entertainment Weekly staged its annual San Diego Con issue with a cover displaying Spider-Man and Electro in a stare-down. Inside are 24 pages of alleged “preview coverage,” but only two of those pages are devoted to comics—one to Marvel’s Inhumanity title; the other, to DC’s Wonder Woman: Earth One. Sad but true: comics have become movies. The remaining 22 pages—all movies and tv, beginning with 8 pages on “The Amazing Spider-Man 2.”

EVANGELICAL RIGHT-WINGER GIVES UP Not really.

But I couldn’t resist the opportunity to rib the Right. Editoonist Chuck

Asay (pronounced “Ay-see,” AC) has retired from political cartooning after

nearly 45 years of skewering the Liberuls from a Colorado Springs perch. Asay

left the Gazette, his newspaper homebase for 21 years, in late 2007 but

continued drawing for syndication with Creators. On July 7, the Gazette published

his farewell cartoon, which we’ve posted at your eye’s elbow. The cartoon includes several souvenirs of Asay’s long combat with the forces of Liberul America. On the wall, it’s clear he’s a gun supporter, and the abstracted fish identifies him as a proud Christian, the donkey trophy as a hunter (and bagger) of jackasses. On his head, Asay wears the tri-corner symbol of the Tea Party, and among those watching him hang up his brush are Obama, Bush, Clinton, and Reagan. And the little old lady the polka-dot dress, the good-intentioned but unthinking Liberul Lady. Asay spent almost his whole life in Colorado. He grew up on a farm near Alamosa in the San Luis Valley and got an art and teaching degree from Adams State College. He taught art in public schools and on an Indian reservation, fought fires, and served in the Army. He left the state temporarily in 1969 when he went to the Taos News to began a cartooning career (he also worked in advertising). He got a job working for the Gazette's one-time rival, the Colorado Springs Sun, in 1978, then moved to the Gazette when it bought and shut down the Sun in 1986. He was the region's only daily editorial cartoonist, and in his 44-plus years at the drawing board, he concocted probably 7,000 cartoons, focused on local happenings and national issues. The Gazette marked his retirement by publishing a cartoon summary of his career, and editor Wayne Laugesen delivered the eulogy (excerpts of which follow in italics): Far from Colorado, I encountered my first Chuck Asay cartoon in high school. ... Upon discovering Chuck's work, I couldn't believe these cartoons were published. They were bold, honest and fearless. Too many run-of-the-mill cartoons of the day seemed like they'd gone through a politically correct board of standards and practices that removed all spice. Some of history's most confrontational cartoons had changed the world. Chuck skewered the left and held nothing back. He wasn't polite. He wasn't safe. He never cowered in fear. Syndicates and editors knew he filled a niche, even if they didn't quite know why. Chuck was never in this for money, though it was his livelihood. He wasn't drawing to gain affection of an audience. Chuck used the talent God gave him to state and defend truth as he understood it. The Bible and Constitution were his guides. He opposed abortion and same-sex marriage, and there was no sense mincing images or words to soften a message for those who didn't want to hear it. If Chuck annoyed us, we could not ignore his cartoons. He challenged the audience. Even those who disliked his work had to trust it, because it was real. He crafted cartoons selflessly, frequently putting his job on the line by making fellow colleagues uncomfortable—including those who sign the front of payroll checks. ... Even fellow journalists who dislike Chuck's positions say they respect and admire the man. He is kind, friendly and professional. He proves that one can stand his ground—resisting whimsical tides of public sentiment—and maintain civilized, respectful relationships with people of opposite minds. Asay’s previous editor, Dan Griswold, wrote in the Foreword to a collection of Asay’s cartoons that he was “amazed by his creativity, his talent, and the power of his medium. With a few strokes of his pen, Chuck can make a reader convulse with laughter or spit with rage. ... He wields a fully automatic Uzi at point-blank range. With his pen and inkwell, he sprays the vicinity of his target—usually spend-happy politicians, meddlesome bureaucrats, or liberal social planners.” I’m one of Asay’s admirers who disagrees with his politics. I met him in Salt Lake City during the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists convention last month. When I saw his name badge, I went up to him, extended my hand, and said: “I admire your drawing. I disagree with most of what you say—and sometimes you’re so far Right I don’t even understand what you’re saying—but I love the artwork.” He smiled and thanked me, and he offered to explain his cartoons to me. Later, we agreed to meet for lunch in Castle Rock, halfway between Denver and Colorado Springs. I’m looking forward to it. Until then, here’s a too-short gallery of Asay (which includes, surprisingly, cartoons I mostly agree with).

I particularly enjoy the two cartoons at the bottom of our first exhibit, the drug education cartoon, “Fightin Just Wars,” the debate over liberty vs. security, and Clinton “Fairness.” This last took me a few minutes to figure out. It seems sensible to tax “the rich,” but not to Asay: he makes “the rich” the big horse, the real power pulling the economy, and in his jaundiced view, taxing the big horse is like putting shackles on that which powers the economy. Nice drawings though.

DICK LOCHER FAILS RETIREMENT On another front of the retirement divide, Pulitzer-winning editoonist Dick Locher, having given up doing political cartoons (see Opus 312), is still pursued by the artistic muse. In his hometown of Naperville, Illinois, he’s working with Jeff Adams, owner of inBronze, a foundry, to perfect a statue of the founder of the town, Captain Joseph Naper, who started the place in 1841. Locher researched the 1830s pretty thoroughly before making sketches of the statue. He had little to go on when creating Naper’s likeness, reports Melissa Jenco of the Chicago Tribune, “but said he was determined to make it a piece that would stand the test of time.” Said Locher: “The expression on the face and the flair of the clothes is everything.” Pointing out that he designed the body with one heel a little off the ground, he added: “The worst thing you can do to a statue like that is to plant two feet on the ground. It’s too static. This has a shelf life of 400 years, and I want it right.” “This is so much fun,” he went on, speaking not only of making the statue but of a lifetime drawing pictures “I’m the luckiest guy in the world. I never went to work a day in my life.” This isn’t Locher’s first larger-than-life statue: four years ago, he finished a towering likeness of the iconic comic strip detective he drew for 28 years: Dick Tracy, like the Naper monument will be, is part of the city’s Century Walk public art collection. See Opus 260 for photos of the statue.

Fascinating Footnit. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

MOTS & QUOTES “Being an English major in college prepares you for impersonating authority.”—Garrison Keillor “Avoid clean living.”—A Nonymous “Remembered joys are never past.”—Cyril Richard “Too much of a good thing is—WONDERFUL.”—Liberace

EDITOONISTS GET SALTY NEAR A BIG LAKE Raising the Temperature in Young’s Old Town There was a

hot time in the old town the whole time the Association of American Editorial

Cartoonists was meeting in Salt Lake City, June 27-29, Thursday through

Saturday. Temperatures soared into triple digits, breaking records nearly every

day in the city Brigham Young and 148 of his Mormon followers (arriving in 72

wagons) founded in 1847, making it officially an “old town.” The outside temperature was matched, briefly, on Saturday with occasionally heated rhetoric as the subject of plagiarism became the focus of the program and the ensuing business meeting. Otherwise, session topics ranged peacefully from crowdfunding to the incendiary nature of political cartoons, from Thomas Nast to the opportunities of Internet cartooning, from Muhammad to Mormon underwear. The profession’s most revered practitioner, Pat Oliphant, was on hand at a reception held in his honor, and another legendary editoonist, Herblock, starred in a 90-minute screening of a new documentary on his legacy. Evening entertainments included a salty edition of Todd Zuniga’s “Cartoonist Death March” and the Cartoons and Cocktails Gala Benefit at which original cartoons were auctioned off with the revenues earmarked for AAEC coffers. Afternoons were free of programming to allow for sight-seeing and other carryings-on. Host and program deviser Pat Bagley (aided and abetted by Prez Matt Wuerker) also arranged for a bus tour of the city and for art workshops conducted by AAEC members for young aspiring artist/cartoonists. In the continuing effort to make the profession more visible to the world outside the inky-fingered fraternity, many sessions were open to the public for a small admission fee. And the convention venue roved around the neighborhood of the headquarters hotel, the Little America, to the Leonardo art museum and activity center to the auditorium at the city’s main library. Early estimates peg registered attendance at about 75, of which 45 or so were fully-paying cartoonists; the rest, speakers, spouses, guests, donors, and volunteers. Local residents also attended the sessions open to them, turning out in notably large number for Saturday morning’s “Satire and the Sacred: From Muhammad to Mormon Underwear” and the auction that evening. The goodie bag issued to registrants as they checked in contained, in addition to the usual heap of helpful items (sketchpad and program booklet and list of preregistered personages), several items designed to acquaint them quickly with this year’s convention city: a map (comically rendered by Bagley, highlighting sites and establishments of the elbow-bending sort), a stick-on bee (Utah is the Bee State), a bottle of Polygamy Porter (motto: “Why have just one!”), and a shot glass bearing the emblem of Five Wives Vodka. Five Wives, introduced into the Utah market in December 2011, created a stir a year later when its makers, Ogden’s Own Distillery, sought to fill orders from Idaho, the governmental apparatus of which had determined that Five Wives would not be allowed through the state’s liquor system. Apparently, quipped Ogden’s, “Idaho didn’t like the quirky label.” Banning Five Wives created a “media firestorm” in USA Today, Time, CNN and Fox. Faced with a law suit, Idaho reversed its decision. Alerted by such souvenirs and shenanigans, we were properly revved up for the ensuing program.

THURSDAY. The day began with a technical problem: in the Leonardo auditorium, the microphones weren’t working properly, which prompted Prez Wuerker to explain: “This is why cartooning is so great: all you need is pen and paper—no electricity or wiring difficulties.” The first presentation was “Kickstarter Nation: Get Your Cartoony Ass Into Money-making Gear!” during which Matt Bors, Bill Day, and Kevin “Kal” Kallaugher talked about their successful crowdfunding adventures. All three screened the videos that ran online to “pitch” their projects; all three raised more money than their goals. Bors and Kal found funding for publications (in Kal’s case, a commemorative tome that lavishly reprinted a sampling of his 35 years drawing cartoons at The Economist); Day, for funds to pay his house mortgage so he could afford to continue to cartoon freelance (for the pittance that such endeavors reap nowadays). Day’s “pitch” included a humorous faux “history of cartooning” in which he displayed Egyptian hieroglyphics that depicted cartoonists at work (a bottle of ink was the telltale image). In desperate need after being laid off his staff job three years ago, Day said he was profoundly grateful to those who, when offered (as he put it) “a chance to be a humanitarian,” seized the opportunity and helped him through a bad economic patch. Kal reminded us that Kickstarter gets a percentage of the funds raised, and that many Kickstarter projects fail to raise the target funding. He also emphasized the amount of work that comes after the project’s funding. Typically, Kickstarter projects offer premiums to backers; he said he spends 45 minutes to an hour daily in “customer service” now that the book is published and available. He printed enough books to supply his backers—with enough left over to sell outright, creating the only profit the project generated. In the next session, “The Art of Controversy: Political Cartoons and Their Enduring Power,” Victor S. Navasky, the author of a just-published book with that title and the former editor of The Nation, began by explaining what got him started on the book project. It was the now infamous David Levine cartoon that showed Henry Kissinger, an ecstatic expression on his face, in flagrante delicto with a woman whose head is the globe of Earth—ergo, Kissinger is screwing the World. When Navasky insisted on publishing the cartoon in The Nation, his staff rebelled. We react more quickly (and more emotionally) to caricatures than to photographs, he said. But Navasky, although permitting a long staff discussion of the cartoon (including an encore with Levine present), published it anyhow. He decided, upon reflection, that what most enraged the cartoon’s critics was that it was a cartoon, a drawing intended to be funny. Making fun of something was offensive, apparently. And Navasky concluded that a similar sentiment inspired worldwide Muslim protest against the notorious Danish Dozen, cartoons of Muhammad published in 2005 in a Danish newspaper, ostensibly to demonstrate freedom of speech and the press. He

showed several cartoons that were famous for getting their cartoonists in

trouble: among them, Art Young’s wanted poster for Christ; Robert

Minor’s “Perfect Soldier”(which is also a perfect cartoon blend of word and

picture, neither making much sense without the other); David Low’s Hitler

cartoons (which inspired Hitler to demand that Low be fired); Jews depicted as

vermin in Nazi magazines; Zapiro’s celebrated picture showing South

Africa’s president, Jacob Zuma, about to rape Justice. Navasky explained the basis of powerful person’s annoyance at being cartooned: Hitler, he said, simply didn’t want to be portrayed as an ass. Navasky concluded with some questions that he didn’t answer: In a medium deploying stereotypes, how does one deal with racial stereotypes? Where do editors draw the line about what to print and what not to print?f How does one reconcile the situation in which, typically, pictures can be more powerful than words?

CITY TOUR. That afternoon, some of us took a guided bus tour of the city, the wide streets of which suggest civic planning of a stunningly prescient sort. Not so, though. When Brigham Young platted the city in the mid-1800s, he had only the most immediate practical objective in mind: he wanted the streets to be wide enough to permit wagons drawn by two horses to make U-turns in the middle of the block rather than go to the nearest intersection. At least, that’s what Host Bagley said—and he should know, being, as he is, co-author (with his brother Will) of This Is the Place: A Crossroads of Utah’s Past, an overview of the state’s history for young readers. The bus drove us by state capital bulding, Temple Square and the Tabernacle, University of Utah campus, and up to the high bluff where Brigham Young first saw the flat expanse of the Salt Lake valley stretch out before him and pronounced: “This is the right place. Drive on.” Perhaps he was expressing exhaustion and relief as much as foresight: after weeks traversing the rocky mountain ranges, flat land must’ve seemed god-sent.

THURSDAY EVENING. We convened at the Tavernacle (no, not a typo) Piano Bar for drinks and pizza and the “Cartoonist/Literary Death March,” during which emcee Todd Zuniga shepherded four cartoonists to their separate dooms. The cartoonists—Steve Benson (Arizona Republic), Signe Wilkinson (Philadephia Daily News), Ted Rall (Los Angeles Times and Universal Uclick), and Lalo Alcaraz (La Cucaracha syndicated comic strip and editoons for the L.A. Weekly)—showed a selection of their cartoons and commented thereon. Their presentations were judged by a panel of three: local bookseller Ken Sanders rendered a verdict on the “literary merit” of each presentation; personality and author (The Mormon Kama Sutra, illustrated by Pat Bagley) Sister Dottie S. Dixon, on “performance”; and Lexington Herald Leader’s Joel Pett, on “intangibles.” Benson and Wilkinson faced off in the first round. Benson, grandson of one-time U.S. Secretary of Agriculture and former Latter Day Saints Church president Ezra Taft Benson, showed what he claimed, with extravagant gestures and raucous hoots, were his Mormon cartoons, but they weren’t: they were the usual rabble-rousing Benson masterpieces. Wilkinson began by saying she was here on “false pretenses”: she had agreed to show her Quaker cartoons because she’d been led to believe Benson was going to show his Mormon cartoons. Turning to Benson, she quipped: “You might come from Mormon royalty, but around here, you’re just another genius.” Ted Rall kicked off the second round by admitting that his cartoons are not funny. Out of respect, no one laughed. His strategy is to be offensive in the manner of newspapers of yore, which reveled in scandal and sensation—and offensiveness—as a way of increasing circulation. Alas, no more. Newspaper editors in these straitened times are tabby-cats not tigers: fearful of offending and losing what few subscribers they have, they avoid controversy in all directions at once. Alcaraz then showed some of his political cartoons, including several depicting Mitt Romney, a forgotten would-be politician, attempting to appeal to the Latino Vote. In one drawing, Romney is shown wearing a gigantic sombrero; the caption, “I am the Juan.” The judges, indulging a variety of rationales absurdum ad nauseum, anointed Benson and Alacaraz winners in their respective rounds, and in the run-off competition, Zuniga posed to each cartoonist questions of a literary nature. This seemed to yr reprtr unfair: cartoonists are noted for illiterate scrawlings, not literary acumen. But both the ink-slingers exceeded everyone’s expectation. Alacaraz led during the early questioning, but Benson, who pounded the keys on one of the dual pianos to emphasize his answers (adding to the cacophony with hoorahs and other hokum), proved surprisingly literate and won at the last minute.

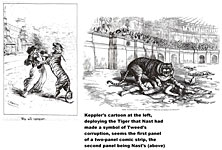

FRIDAY. After another continental breakfast at the Leonardo, we gathered in the auditorium for what Wuerker described as a somewhat more “fine arty” presentation than usual: in her “Magical Mystery Tour” Jann Haworth, artist/designer of the album cover for the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, described how the legendary collage was put together. All of the living celebrities whose faces appear in the work were contacted in advance to secure their permission. Mae West initially demured: “What would I be doing in a Lonely Hearts Club?” she wanted to know. Haworth’s role was to supervise the creation of the cover art in accordance with another artist’s design; for that, she won a Grammy, which she displayed on the lectern (the miniature speaker fell off and rolled around in ever-decreasing circles on the slanting surface). The project, involving a half-dozen or more assistants, took 10-14 days, she said. In the next session, author and historian Fiona Deans Halloran discussed aspects of her new biography, Thomas Nast: The Father of Modern Political Cartoons. She rehearsed the major events in Nast’s life, noting, among other things, that Nast first used the elephant to symbolize the Republican Party but merely popularized the donkey for the Democrats. He also reinvented Santa Claus as a jolly not a judgmental old soul—cultivating happiness not rendering verdicts about goodness or badness. Halloran

also observed that Nast was accused of stealing images from other artists

during his lifetime, accusations he denied, saying his ideas were all his own

even while openly aping images in well-known paintings. Nast’s famed cartoon

depicting the Tammany Hall tiger triumphantly straddling the figure of Reform

while growling “What Are You Going To Do About It?” is very possibly a

borrowing from a Joseph Keppler cartoon, published only three weeks

earlier (but in St. Louis, not New York, which raises doubts about whether Nast

could have seen it). Inspired by Keppler or not, Nast’s cartoon appears to be

the second of a two-panel comic strip of which Keppler’s cartoon is the first

panel. Nast was reportedly a lovable and loving person, Halloran said, and while he was very much in favor of emancipation of the slaves, he caricatured blacks cruelly and believed they were not fit for political life. As Halloran said: “It is hard to find anyone in 19th century public life who is not problematic [in this and similar matters] because they have sometimes fallen short of modern concepts of progressive thinking.” Howard Tayler, artist, cartoonist and digital entrepreneur, took us into the electronic ether with “Successful Cartooning in the Digital World.” In his highly polished presentation, Taylor urged that each cartoonist to “own your work, own your careers, own your content, own your audience, own your name (and turn it into a brand), and own the dot.com of your name.” Someone who owns all of that can sell advertising and products and become richer than Romney. Tayler listed several places that could be consulted about getting advertising on individual websites: Turn-key Networks, Google Adsense, Pulsepoint, Project Wonderful, Amazon Affiliate. Moreover, we should not be dependent upon a single paycheck; he cautioned, do not have a single source for more than 40% of income. At lunch, former Utah Senator Bob Bennett (unseated in the Republican primary by a Tea Party candidate) regaled us with his views on the current state of the Republican Party, saying that since he never expects to run for public office again, he can say whatever he wants to. His chief criticism of the GOP these days is that it is rigid, unwilling to compromise. The problem in Congress is that it is no longer “transactional”—i.e., trade-offs don’t work anymore because of standards of ideological purity. Sticking to one’s principles is laudable, he said, but we all must learn to adjust our expectations. About Mitt Romney, Bennett said he probably lost his bid for the White House because he wasn’t a “natural politician.” The afternoon was free for most, but several members (Kal, Cal Gondahl and Pat Bagley, aided by National Geographic writer and paleontologist Brian Switek) conducted for children an art workshop on drawing dinosaurs at the Natural History Museum of Utah, where we all re-convened that evening for—:

THURSDAY EVENING RECEPTION FOR PAT OLIPHANT On the way to the reception on Level 5 of the Museum, the last of the practicing editorial cartoonists in the country (as Matt Bors put it) “all passed through an exhibit of dinosaur bones.” We could not have concocted a more ironically telling circumstance. After a suitable interval of finger-fooding and adult beverage imbibing, we watched the Master as he sketched, his pictures projected onto a large screen for us all to see as he drew. He began by producing a pair of cartoons that demonstrated his apprenticeship. One of his first jobs on an Australian newspaper was to re-touch photographs. For instance, if at a high society gala, a photo depicted two magisterial matrons with a decided “nobody” somehow standing between them (sharing the spotlight, so to speak), Oliphant would cut the interloper out—literally, using a pair of scissors—and reassemble the photo without the “nobody.” To illustrate, Oliphant drew a picture of three women and, applying a razor blade, cut the central figure out. Similarly, he attended to the photographs of animals at live stock shows. Prize bulls, their genitals on rampant display, were potentially offensive. Oliphant drew one such critter and, again applying his razor blade, removed the offending body parts. “It was good practice for political cartooning,” he quipped. Some of the audience suggested topics, and when asked to re-create his favorite editorial cartoon, Oliphant drew a gaggle of priests pursuing small boys at St. Pedophilia’s. To conclude the event, Host Bagley brought forth a trophy that we were presenting to Oliphant as a token of our regard. This revered object, which Bagley held aloft in a mock ceremonial procession, was covered with a hood, but we never got to see it: just as he approached the front of the room, Bagley stumbled and dropped the hooded trophy, which fell to the floor with a glassy crash. Consternation. But not for long. Bagley left the room in chagrin, returning a few second later with a gunny sack that rattled. The episode of crash and tinkle was clearly a ploy. The real token was in the sack. He opened it to reveal —a rock. A rock about the size of a good-sized prime rib. On the rock was emblazoned a tiny penguin. Oliphant’s Punk. Bagley held the rock up over his head. “Punk rock,” he said, a look of triumph on his cherubic visage. The gunny sack, it turned out, also held dozens of small pebbles, each of which bearing the image of Punk. “Where,” I asked Bagley, “did you get all these?” “The Internet is a wonderful thing,” he grinned.

AFTER THE CROWD around Oliphant thinned a little, I went up and introduced myself to Oliphant, saying: “I want to tell you a story about an intimacy we share that you know nothing about.” I told him, then, that when I was in college in the 1950s—that is, before he came to this country from his native Australia—I started signing my cartoons with a little rabbit: “Harvey the rabbit,” I helpfully explained. “I thought Harvey the rabbit was six feet tall,” Oliphant said, displaying the vast erudition for which, among other things, he is famous. “Well, I’m five-eleven,” I said, “—and I have aspirations.” After graduating from college, I continued, I went into the Navy for several years, and when I got out, Oliphant was cartooning at the Denver Post, signing his cartoons with a tiny penguin. “I knew immediately,” I said, “that I could not continue to sign my cartoons with a rabbit: everyone would accuse me of imitating your device. So for the next forty years, I didn’t sign my cartoons with my rabbit.” Oliphant grinned sympathetically and reached out to shake my hand. And I responded in kind, shaking his hand as a gesture of forgiveness. What I didn’t tell him, however, was the other reason that I gave up the rabbit: when I returned to civilian life, I started freelancing cartoons to magazines, and one of those magazines was Playboy. I realized that if I signed my submissions to Hugh Hefner’s magazine with a rabbit, I would appear more than just a bit sycophanic, too obsequious by far. And probably wouldn’t sell a single cartoon there as a result. (But I didn’t sell any cartoons there with just my name as signature either. So much for decorum.) In

the accompanying photograph of me and Oliphant, he’s pointing to my name badge

(which I’ve reproduced next to the photo), specifically, to the rabbit that

adorns the badge. Historic. As a purely technical curiosity, I have no idea why

I’m in focus in this photo and Oliphant is not; some sophisticated mechanism in

the camera, no doubt, focuses at random on whichever face it mysteriously

chooses. Before collecting our pebbly Punk souvenirs and boarding buses to return to the Little America Hotel, we also presented a certificate of appreciation and admiration to Universal Uclick’s Lee Salem, who is on the cusp of retiring after a long career with the syndicate during which he set standards promoting editorial freedom for syndicated cartoonists. See Opus 307 for details about Salem’s achievements.

SATURDAY & PLAGIARISM. At the Salt Lake City Main Library in the Tessman Auditorium, Joe Wos, founder and curator of the Toonseum in Pittsburgh, started off the morning with “A Brief History of Plagiarism” in American cartooning. Images widely plagiarized include Ben Franklin’s celebrated “Join or Die” picture of a segmented snake (which was endlessly copied, recycled and modified—even during the Civil War), the familiar etching of the Boston Massacre, Uncle Sam, the Yellow Kid (who appeared in two sensationalizing New York newspapers simultaneously, giving rise to the expression “yellow journalism”), the Katzenjammer Kids in two incarnations, both of which ran for sixty years. Among

the most recent copycatted cartoons are Disney’s “The Lion King,” ripped off

from a Japanese animated film, and Saul Steinberg’s famed New Yorker cover that ridicules the parochialism of New Yorkers by depicting in detail the

island of Manhattan as the center of the known universe with the rest of the

United States receding into a vague but empty desert, marked only by the names

Jersey, Kansas City, Nebraska and Las Vegas, with Texas, Utah, and Chicago

added as afterthoughts, all on the other side of the Hudson River and vanishing

into the distant Pacific Ocean. Wos showed imitative images from Matt Wuerker

and Ted Rall, proving, we suppose, that almost no one can resist, from time to

time, borrowing a telling image. The much maligned Bill Day took the podium to defend himself successfully against the charge of being lazy, an accusation originating with the publicity given several of his cartoons in which he repeated the central image but changed labels or captions to re-direct the cartoon’s commentary. He was summarily crucified on the Internet, he said, without being given a chance to defend himself. He subsequently did defend his practices with a pair of blogs posted at the Cagle Cartoons website, but those efforts scarcely matched the viral circulation of his critics’ attacks. Day traced his life story, which demonstrated amply that he is decidedly not lazy but an energetic, hardworking and dedicated editorial cartoonist, who, after being laid off three years ago at the Memphis Commercial Appeal, worked odd jobs at menial tasks during the day in order to support his family—and then cartooned all night long to preserve his career. A discussion of plagiarism followed, as prelude to the AAEC Business Meeting, at which two proposals for a Code of Ethics for the Association were to be discussed. Both of these proposals are presented at the end of this posting: one, authored by Matt Bors and Ted Rall; the other, by R.C. Harvey. The nature of the discussion (but not its entirety) is indicated in the comments and summaries below. Rall, whose vociferous and repeated criticism of Day and of Daryl Cagle for re-using images (and for plagiarizing) inspired the Code of Ethics proposals, sees the political cartooning profession as “beleaguered,” the number of its practitioners dwindling as newspapers eliminate staff editorial cartoonist positions, because “we’re seen as doing low-quality work ... not serious political commentary,” thanks, at least in part, to the plagiaristic shortcuts taken by too many editorial cartoonists. Still, despite his proposal’s apparent recommendation that AAEC “police” the profession to rid it of plagiarism (much as the American Medical Profession stands guard over medical practice), Rall said he was not in favor of any formal policing mechanism; instead, AAEC members should blow the whistle whenever they see evidence of plagiarism. And even then, he added later in the discussion, only in cases of “extreme” plagiarism. “Extreme” was left undefined. At issue is not whether to be for or against plagiarism: the Association adopted a bylaw against plagiarism in 2009, including a proviso that “the Executive Board may act to permanently or temporarily suspend” any member caught copying too brazenly. The question of the moment is whether AAEC as an organization should adopt a Code of Ethics. Bors, who is most adamant about the “re-use” of images, spoke in favor of AAEC’s adopting ethical guidelines. No one spoke in favor of the Association policing editorial cartooning. Why attract criticism of the profession by broadcasting the occasional sins of a few cartoonists? Cagle pointed out that plagiarism is about work product, not ethics. Several observed that the issue has arisen previously in the not-so-distant past, and AAEC chose then not to pursue the matter. Word of mouth—particularly these days with the Web and social media hovering over everything—will provide an ample mechanism to chastise the sinners. The general consensus seemed to be that if AAEC adopts a Code of Ethics, it should not be as a bylaw but as an informative pamphlet of guidelines. The discussion ended when President Wuerker intervened to call the Business Meeting to order. The Business Meeting was brief: local residents were already waiting in line outside the room for the “Satire and Sacred” session to begin, so routine business was disposed of quickly. But nothing could be done on the Code of Ethics issue because the members in attendance did not constitute a quorum. Wuerker announced then that the questions about whether to adopt a Code of Ethics and what sort of code it might be would be put before the membership in the form of a survey. The survey would present the Rall/Bors and Harvey proposals as lists of individual items to be voted on, yes or no.

THE REST OF SATURDAY. Tessman Auditorium was filled almost to capacity (300? 400?) for the next event, open to the public, “Satire and the Sacred: From Muhammad to Mormon Underwear.” Moderator Bagley got the session off to an appropriately irreverent but affectionate start by showing one of his cartoons in which Larry King alludes to Mormonism as “ordinary people just trying to become gods” (which is the ultimate objective in Mormon theology). Another

cartoon continued in the same vein: Gahan Wilson’s “Is Nothing Sacred?” depicts

a mob of worshippers, bowing and scraping before an altar on top of which a

huge cube is labeled “Nothing.” The panelists, Daniel Peterson, author of Muhammad Prophet of God, and Victor Navasky in a return engagement, focused mostly on Islam’s apparent attitude about cartooning Muhammad. Navasky observed that although the Danish Dozen had been published in order to make a case for freedom of speech and press, in the West—say, in the New York Times—the opposite occurred. Newspapers never published the cartoons that had inspired world-wide protest among Muslims, citing “decorum” (or “respect for another religion”) as the reason. We can scarcely have “free speech” if “decorum” stops publication, Navasky said. “What about photos of the Abu Ghraib prisoners?” Navasky asked, rhetorically. Publication of pictures of Muhammad is a blatant provocation, he continued. But the provocation arises not so much from picturing Muhammad as from picturing the Prophet in a negative way, which displays disrespect. Peterson concurred. Respect for and veneration of the Prophet in Islamic communities is extreme, he said. Ditto the Koran. Muslims believe that it is up to the entire community to defend respect for the Prophet. Later in the session, cartoons attacking Mormonism in the early days were shown. Various practices of Mormons, particularly polygamy, seemed to undermine the prevailing U.S. culture. “The cartoonist draws what you cannot put into words,” Navasky summarized. In the afternoon, Steve Benson conducted a workshop for young adults on “The Art of Cartooning,” and in the Tessman Auditorium, a 90-minute documentary about Herb Block, another of the idols of the profession, was screened. “Herblock: The Black and the White,” recently premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival, was almost entirely about the cartoonist’s work; his life was barely touched upon. Perhaps the most revealing of the autobiographical aspects of the film reside in footage of Herblock’s office—its decor, chiefly piles of paper and row after row of jar after jar of pencils, all dubbed “landfill” by Joel Pett. We also learned of the long-term romantic relationship of the never-unmarried Herblock when his lady friend and companion came on camera to say a few words.. The tenor of the film was worshipful, perhaps too much so; but in its devotions lies inspiration, which is doubtless the best way to preserve Herblock’s legacy.

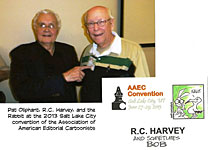

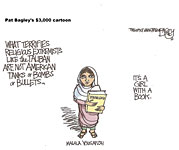

SATURDAY EVENING.The concluding event of the convention was the Cartoons and Cocktails Gala Benefit which benefitted, this year, the coffers of AAEC. In the preassembly area of the Little America Ballroom, a couple score of original cartoons (including Oliphant’s sketches from the previous night) were on display in a silent auction. After an appropriate interval of imbibation and finger-licking, a selection of original cartoons were sold in a live auction conducted with his usual flair by Kevin “Kal” Kalaugher. Open to the public, the auction offered, among other treasures, an original Doonesbury strip by Garry Trudeau, which brought about $600. The record for the evening, however, was Bagley’s: his cartoon exposing the cowardice of the Taliban in attacking a young girl for her persistence in advocating education for women fetched an astounding $3,000 from a local resident (testimony to Bagley’s standing in the community, where he has been cartooning at the Salt Lake Tribune for over 35 years, the longest tenure at one daily publication of any U.S. editorial cartoonist). Altogether, the auction brought in over $10,000 for AAEC, Bagley said.

AWARDS. After the auction, emcees Steve Kelley and Joel Pett presided over the presentation of awards—: The Locher Award is conferred annually to the best cartoonist at a U.S. college newspaper. Presented in memory of long-time AAEC member Dick Locher’s talented son John who died in 1986 at the age of 25, this year’s award went to Kara Yasui at the University of California, Los Angeles. The award includes paying expenses and transportation to the convention site for the recipient. The Locher judges said this about Yasui’s work: her cartoons “are notable for being strong both in concept and execution. Whether skewering the partisans in Washington or throwing darts a higher education issues, she shows an impressive level of sophistication in her drawings and coloring. ... Her readers at UCLA are already seeing stellar work.” The Courage in Editorial Cartooning Award is presented every year by the Cartoonists Rights Network International, a non-profit watchdog organization dedicated to protecting cartoonists whose livelihoods and, often, lives are threatened by oppressive governments that object to the criticism inherent in all political cartoons. Presented by Robert “Bro” Russell, CRNI’s Executive Director, the award this year went to Syrian cartoonist Akram Raslan, who was unable to attend, his exact whereabouts unknown. Raslan disappeared in Damascus in January and was reportedly being held incommunicado by the Assad government and tortured because he drew cartoons critical of President Bashir al-Assad and his conduct of the civil war raging in Syria. The charges include collaborating with rebel groups, working against Syria’s constitution, insulting the president, incitement to sedition, promoting revolt against the public order, undermining the prestige of the Syrian state, and being a CIA and Israeli agent. CRNI wrote the Syrian ambassador in Washington, D.C., asking him to intervene on Raslan’s behalf, and the trial, scheduled for June 3, 2013, was postponed indefinitely. The third of the evening’s awards was AAEC’s Ink Bottle Award, presented this year—surprise, surprise—to me! in recognition of my alleged service to the Association and “distinguished efforts to promote the art of editorial cartooning” (as the plaque states). I was honored and somewhat overwhelmed, having never won an award before and not regarding myself as particularly distinguished either. Following these presentations, the convention adjourned, many of the studious members finding their way to the Prez’s room for singing songs and other frivolities. Even more frivolous are the images on display in our short gallery of pictorial souvenirs, herewith—:

THE FIGHTING 1099ers Maybe it’s because everyone gets a little stoked at these annual editoonist hoorahs, but we’d scarcely got back home, when a new drumbeat began. Someone remarked about the steady decline in full-time staff editorial cartoonist gigs that “the real bloodletting” began when family-owned newspapers disappeared: “the corporate takeover of newspapers with Wall Street applying its ‘maximizing shareholder value’ formula to the reportorial enterprise” effectively ended daily print journalism as a calling. It became, perforce, an industry that had to perform as all businesses do: it had to make ever-greater profits for its shareholders. Some of us began casting a woeful eye, again, at the list—only a miserable 51 full-time staffers left. That prompted a question about who, exactly, constitutes a “staff” editoonist. The answer is right out of IRS. If you receive a W-2 form from an employer for drawing cartoons, if you get sick days, vacation time, and possibly health care from that employer, you’re probably a staff cartoonist (assuming that cartooning is your primary duty). If you’re paid per drawing and you’re filing 1099 forms in April, you’re probably a freelancer (no matter how frequent your work is published). Then came the rallying cry from “Kal” Kallaugher: “Let’s make an alternative list of those who are making a living as a freelance editorial cartoonist (henceforth called the ‘Fighting 1099ers’). This may be the new norm. But don’t despair. There’s some exciting stuff being created out there in Freelanceville. Our profession is far from dead yet!” he finished, effectively becoming the first of the Fighting 1099ers. Then he started the alternative list by naming a dozen editorial cartoonists who make a living freelancing—starting with Pat Oliphant, who hasn’t qualified as a full-time staff cartoonist since 1981 (“but his employment status has hardly tarnished his standing in the profession”). Others joined in, and in less than an hour, the list numbered close to 80. Add those to the full-time staffers and we get 130 still punchin’ and stompin’ editoonists. Not a huge number, but editorial cartooning has never been a populous profession. And tripling the number of practitioners, putting freelancers together with staffers, gives us a roster resplendent with achievement and potential. Right, Kal: we ain’t dead yet.

SALTY ADVENTURES INTO CARTOONING HISTORY Sauntering, sweltering, through the streets of Salt Lake City, I came upon a restaurant named The New Yorker. And the restaurant’s sign even preserved the typography of the famed magazine. I was momentarily astonished until I remembered that the founder of the magazine in 1925, Harold Ross, had a Salt Lake City history. In fact, as I cogitated further, I recollected that Salt Lake City was a training ground for two people whose subsequent careers substantially affected cartooning. Ross was born in Aspen, Colorado, in 1892. Aspen was on the cusp, then, of dying off. It had started as a mining camp in 1879 during the silver boom, but the boom fizzled in about 1893 when the government stopped buying silver. The Ross family moved out of Aspen when Harold was approximately eight; Aspen declined rapidly until the mid-20th century when it started skiing. The first ski run in Aspen—in Colorado—was mapped out in 1936 by speed racer Andre Roch. The first chair lift didn’t use chairs, exactly. The townspeople made a ten-passenger boat tow powered by an old mine hoist and a truck engine. But enough about the slopes. The Ross family moved around to some small Colorado towns, and then to Salt Lake City, where Harold attended high school but never graduated; he quit school after his sophomore year and went into newspapers. In high school, he’d worked on the school paper, The Red and Black. There, he met the other Salt Laker who would influence cartooning in America—a teenage artist three years older than he, John Held, Jr., who was born and raised in Salt Lake City. They became friends and both were stringers for the Salt Lake Tribune while in school, and they were sometimes sent to the Stockade, the old redlight district, to interview such stellar attractions as Ada Wilson, Belle London, and Helen Blazes. Ross was on his best, most circumspect behavior when interviewing Blazes, one of the more flamboyant madams. Not wishing to give offense, he couched his queries in the most delicate euphemisms, overusing, perhaps, the most common of them, “fallen women.” His politesse finally exasperated the plain-spoken Blazes. “Jesus Christ, kid,”she blurted out, “cut out the honey. If I had a railroad tie for every trick I’ve turned, I could build a railroad from here to San Francisco.” The teenagers grew into an unlikely pair of adults (as we see in the accompanying drawing). Ross had a reputation for hair that stood straight up into the air and, strange for the founder of a sophisticated big city magazine, for a rumpled wardrobe. Ross and Held seldom worked together post-Salt Lake (although Held drew uncharacteristic antique-looking woodcut-style cartoons about 19th century life for Ross’s magazine), but separately, they shaped hunks of the cartoon medium.

Ross had worked for at least seven papers around the country by the time he was 25, when he went into the American Expeditionary Force attacking the Hun in Europe. In Ross’s case, the attack was launched at editorial desks of the Stars and Stripes, where he was managing editor. Being an editor evidently got him to thinking: soon after he got back home, he started planning a magazine of his own. Meanwhile, Held had long left Salt Lake City for the glitter of the Jazz Age. His cartoons of round-headed sheiks in “Oxford bags” (bell-bottom trousers) and shebas in short skirts established the look of Youth in the roaring 1920s. When Ross’s magazine got going, it effectively re-defined the single-panel magazine cartoon by blending the captions and the pictures so thoroughly that neither made any comedic sense alone without the other. We don’t know if these epoch-shaping events are the result of growing up in Salt Lake City—or leaving it. So you can draw your own conclusion.

QUOTES AND MOTS “I’ll do my cryin’ in the rain.”—song by James Taylor “Everything in moderation includes moderation.”—Wish I’d Said That (Maybe I Did) “Everything I need to know, I learned from Nancy.”—Ernie Bushmiller “Retirement—twice as much husband, half as much money.”—Who?

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy Harold Ross’s

only child, The New Yorker, a veritable model of sophistication and

suavity, has, once again, entered the arena of political-societal controversy. long ago rejected the gaiety of Bert and Ernie, seeing in the rumor just another Right Wingnut sensation-mongering attempt to discredit either Sesame Street or Bert or Ernie or homosexuals or their advocates or maybe all the above. But I finally recalled the scabrous accusation, decided that The New Yorker elected to believe it for the purpose of a Supreme Court decision cover illustration, and then I applauded. As a footnote, though, is using the images of Bert and Ernie—even as clouded as they are in a dimly lit room looking at tv—plagiarism?

WHERE’S THE OTHER OPINION? Michael Minor in the Chicago Reader on June 18 pondered the one-sidedness of the editorial fraternity on the question of national security and eavesdropping on citizens’ telephones and internet activity. “Not not a single cartoonist defended the NSA,” Minor observed, “—not even to the extent of allowing that President Obama had a point when he said June 20 in San Jose that ‘you can't have 100 percent security and also also then have 100 percent privacy and zero inconvenience.’" When Minor asked the Chicago Tribune’s editorial page editor Bruce Dodd why the Trib didn’t publish one or two cartoons in that vein, Dodd told him there weren’t any. “Yet the president made a pretty good point,” Minor resumed, “and I bet a lot of these cartoonists don't disagree with it. So why didn't any of them say so? Let me propose an answer. A cartoon attacking Obama and the NSA for snooping on Americans practically draws itself. A cartoon defending the NSA surveillance as regrettable but necessary—how the hell do you draw that? A great editorial cartoon (not that any of the Tribune's was) is like a great epigram—it's easier to admire than trust. Like the gleaming Bean in Millennium Park, it's got seams but you can't see them. “As I try to figure out my own position in this debate,” Minor continued, “what I'm surest of is that it's a good thing the secret's out—some matters need to be aired, even if the public would rather go back to knowing nothing. I just wish my own convictions hadn't been undermined by that array of cartoons in the Tribune. They were five variations on the obvious.” So Minor decided to do some research. Did any cartoonist do a cartoon in support of secret spying? “My

search wasn't exhaustive, but I came across a couple of cartoons by the Houston Chronicle's Nick Anderson (whom I know a

little) that made points that are harder to pigeonhole. One showed a little

sympathy for Edward Snowden as well as wariness of the massive powers of

state. Another commented wryly on Obama's call for debate. Then

Minor turned to one of Chad Lowe’s efforts at the South Florida

Sentinel: “Maybe it can be argued that this one took the other side. At any

rate it deals in no uncertain terms with Snowden the blabber. I suppose Edward Snowden should be congratulated, in a way, for creating a national furor by exposing widespread government surveillance activities of average citizens in the name of national security. If what Snowden sought by his actions was a national self-examination of how government by, of and for the people discharges its responsibility to protect the nation, then he succeeded. As it turns out, everybody dropped the ball—especially our elected officials in Congress who were supposed to provide oversight on our behalf. When they should have been openly discussing the delicate balance between security and civil liberties and whether our current methods were knocking everything out of whack, they chose instead to keep everything hidden—no doubt because the topic is so sensitive that it amounts to a political third rail for anyone who questions it. A few did, and they were overridden. None of this justifies the young government contractor compromising programs that may well have protected us from past harm and could have in the future. It was not for him to make the unilateral decision. If our national security community were made up entirely of Edward Snowdens who felt they could simply expose all our secret programs as a matter of conscience whenever they felt like it, we’d have no secrets. Snowden broke the law, and even if what he did leads to something positive, he broke it, nevertheless. There are other avenues for accomplishing his goal. Maybe they’re slower and less glamorous, and maybe it takes more effort and perseverance to achieve results when working within the system, but they do exist. In this era when the Internet has become virtually an extension of our private selves, we shouldn’t allow the creepy feeling that our government is spying on us to cloud our realization that young Mr. Snowden may have done great damage to this country. To some, he’s a hero. To this American, he’s just a self-aggrandizing publicity hound who was too lazy to do it the hard way. Minor continues: “An impressively subtle formulation of behavior and its consequences. How in the world would Lowe convey it in a few strokes of pen and ink? He didn't try. In fact, he couldn't even sustain that level of thought [he displayed] at the keyboard. And Lowe's essay quickly deteriorated. Snowden, he asserted, had ‘other avenues for accomplishing his goal’ ([but Lowe] didn't say what they were) and should have taken them.” I agree that to convey the complexity of the ideas of Lowe’s essay in a pictorial manner is nearly impossible. And Lowe’s picture is certainly a lot less subtle than his prose. But it is nonetheless a notable stab (pardon) in the right direction, the same direction as his essay. And my disagreement with Minor on this point doesn’t unhorse the validity of his other contentions: too few editoonists spoke out in favor of NSA and natural security probably because it’s too easy to do cartoons that clamber up on whatever wagon of sensation and outrage is passing by, and translating nuanced ideas into simple imagery is impossible. And all of these judgements apply equally to—:

THE ZIMMERMAN CASE While the so-called “trial” was going on, I saw few editoons on the subject, and most of those few took one or the other of two positions, calling Zimmerman a racist lout or ridiculing the circus atmosphere created by endless legalistc punditry on cable-tv news—both highly “popular” but intellectually undistinguished attitudes, neither appropriate to the gravity or complexity of the case. And immediately upon the announcement of the verdict (“not guilty,” in case you were off visiting Mars last week), mob rule once again started gathering momentum in the nation’s streets; it worked before—when foot-stomping and breath-holding succeeded in getting George Zimmerman arrested and charged and tried—so its proponents have every expectation that it’ll work again. This time, to overturn the verdict? Or to get Zimmerman tried on another, related, charge? I was relieved when Zimmerman was found “not guilty.” Many black Americans and progressive whites were not. For black Americans, the Zimmerman verdict confirms what they already know: that America is a racist society that systematically denies racial minorities equal treatment and rights. And many progressive whites agree. (So do I, for that matter.) For Rightwing locked and loaded Americans, the Zimmerman verdict translates into a victory for gun-tottin’ rights. But the trial wasn’t about any of these matters. Nor did it “prove” any of them. For some of us, the Zimmerman verdict represents the triumph of justice—not of fairness or of rightness, but of the only justice a society can be reasonably sure of delivering, a system of justice, a judicial process that guarantees a trial by jury. Whatever the outcome in such a system, the process itself is superior to the mob rule than brought Zimmerman to trial. As a purely legal matter—not a question of morality or of the evils of racism—Zimmerman was not guilty of second degree murder, defined online in the free legal dictionary by Farlex as “a non-premeditated killing resulting from an assault in which the death of the victim was a distinct possibility.” Perhaps Zimmerman’s accosting Trayvon Martin could be seen as an “assault,” but it’s doubtful that Martin’s death could have been foreseen as a “distinct possibility” at the time of the “assault.” Zimmerman killed Martin, of that there has never been a doubt. At issue was only whether Zimmerman was acting in self-defense. At the trial, the lawyers went back and forth with witnesses to try to determine whether Zimmerman or Martin initiated the physical part of the assault. But that doesn’t matter. Judging from Zimmerman’s account to the police at the time of the incident and from the condition of his scarred head, Zimmerman was at some point under physical attack from Martin. At that point, he could reasonably be expected to fear for his well-being if not his life. Under those circumstances, he was clearly acting in self-defense, which, in this country, is usually an adequate justification for deploying deadly force. If Zimmerman is charged and tried under some other law—say, the federal “hate crime” laws (now being considered as a possibility)—the outcome could well be different. That’s the way it is in a country ruled by laws, not angry shouts in the streets. Did Zimmerman intend to kill Martin at any time? Maybe, maybe not. Maybe not even when he groped for his gun and fired it into Martin’s chest. Is Zimmerman a racist? Probably—at least insofar as most Americans are one kind of racist or another. Have black Americans been regularly and persistently persecuted by racist white Americans? No doubt at all. But Zimmerman shouldn’t have to take the fall for all of us—any more than black teenagers generally should take the fall for a few misbehaving juvenile delinquents. I looked at about 30 Zimmerman editoons this morning (Tuesday, July 16), mostly at cagle.com. Virtually all of them depicted the Zimmerman verdict as a travesty of justice and a triumph of racism—despite the testimony of one of the jurors, interviewed yesterday on CNN, that racism was never an issue among the jurors. (Well, to be fair: the cartoons were all concocted before the juror told her story.) Of the cartoons I looked at, Bill Day’s seemed the most measured (although some would say it’s a cop-out). Titled “Born Black in the U.S.A.,” it depicts a black infant as the center of a target that fills the outline of the United States map. Day clearly drew it in response to the Zimmerman verdict, but it could have been drawn at any time in the country's history with equivalent appropriateness. So it isn't so much a part of the populous parade of editoons that are piling on the Zimmerman outcome as perpetuating racism because that seems to be the right attitude to have in liberal America at the moment. Piling on right now is the easiest approach to take in drawing a single picture of comment. Day’s

cartoon is not daring or terribly insightful about the issues in the Zimmerman

case. It is, rather, a vast general statement about racism in America. It’s

worth noting because Day isn’t piling on. And just below Day’s cartoon in our exhibit, Pat Bagley also made a comment on the larger dimensions of the issue. In this case, he’s skewering a Utah population of gun-slinging Dirty Harrys, but it can apply to racism as well as gun rights. And, like Day, Bagley is not piling on in the go-with-the-crowd fashion of most post-Zimmerman cartoons. Not one of the nearly three dozen cartoons I looked at even attempted to deal with the complexity of all these issues. Too complex for a single cartoon, no doubt. But a series of cartoons—perhaps all by the same cartoonist—could perhaps deal with many aspects of the case. Instead, we have more shouts in the street. Maybe tomorrow’s crop of editoons will begin to be more nuanced. In any event, I must stop here: cartoons are popping up every few minutes on the Web—each one a possible prompt for another comment from me—and perhaps before this Opus gets posted, my criticism will have evaporated under a deluge of complex cartoons that don’t cowtow to popular sentiment but speak to the larger issues we face.

THE CRUSADER’S CLAY FOOTSIES Ted Rall, in case you hadn’t noticed, is something of a paranoid crusader on behalf of editorial cartooning. As a rhetorical strategy, he invariably takes the most extreme position on any question and then exaggerates whatever facts he can find that support whatever his contention of the moment may be. In his syndicated column for June 24, for instance, he talks about the death of editorial cartooning. “The layoffs continue,” he observes. “The Bergen Record just laid off Jimmy Margulies. ... It's the same story with syndication. It costs a paper about $15 or $20 a week for three to five cartoons by an award-winning cartoonist, but even that's too much for cash-strapped newspapers. They've slashed their syndication lists. (They say they'll use the savings to hire local cartoonists — but never do.) Many papers are doing without cartoons entirely.” Mostly, all this is true, more or less. But about those “many papers doing without cartoons entirely”? I don’t know of any. Ted—can you name two? Just a little exaggeration for rhetorical purposes. He goes on: “At newspapers, cartoonists are the first fired, the last hired. When media gatekeepers — including those on prize committees — reach out to a cartoonist, they gravitate toward old-fashioned cartoonists who use hoary tropes like donkeys, elephants, labels and lots and lots of random crosshatching. Fetishizing the past is counterproductive because it discourages innovators. Also, it doesn't work. Readers don't respond. But editors blame cartooning as a medium when their real problem is their lousy taste in cartoons.” This is an argument that he constructs out of whole cloth—cut to fit his own pet peeves of years’ standing. Since he doesn’t do cartoons with donkeys or elephants in them and doesn’t use labels, he believes, passionately, that any cartoonist who partakes of these devices is “old-fashioned.” From that conviction—not a fact, mind you, just a conviction— it is but a short step to “fetishizing the past,” and from there, he concludes that “innovators” (among whom he justifiably counts himself) are ipso facto “discouraged.” The first link in the chain of logic, however—that cartoons with donkeys and elephants and labels in them are “old-fashioned”—is opinion, not fact. On the other side of the equation, he says that readers don’t respond to old-fashioned cartoons. I don’t know about either of those propositions—the “old-fashioned” and the readers’ lack of response attributed to the hoariness. One of the latest outbursts of reader outrage concerned Jack Ohman’s cartoon about the explosion of a fertilizer plant in Texas. Ohman’s cartoons are not, in my view, “old-fashioned”; but Rall would doubtless slap that label on them. So what about reader response to Ohman’s cartoon? See Opus 310; readers responded. So Rall’s proposition—that old-fashioned cartoons don’t produce reader reaction—isn’t accurate. At least in this circumstance. Probably in many others, too. Exaggeration and careful selection of details to support one’s opinion—that’s Rall’s rhetoric. And editors who blame cartooning as a medium? Blame it for what? That absence of reader response that is itself largely a rhetorical fiction? I doubt that such editors exist. Some (perhaps many) editors may not like (or even understand) editorial cartoons; editors are, after all, word people, and cartoons are best understood by word-and-picture people. But most editors know readers like editorial cartoons: they like to applaud them, and they like to excoriate the ones they don’t like. Editors may sometimes pick “lousy cartoons,” but readers respond even to lousy cartoons if their oxen is gored. Rall tries by assembling factoids and rumors and a few random opinions (mostly his own) to construct an argument that’s chief purpose is to goad fellow cartoonists into doing better. I’m certain that’s what he thinks he’s doing. His motives are not surreptitious or otherwise stealthy maneuvers. Yet one cannot help but wonder. By denigrating the work of most other cartoonists (all those “old-fashioned” guys), he (perhaps unconsciously) touts his own work in contrast as superior. Is he trying then to persuade newspaper editors that his are the better cartoons so they would published them—or hire him instead of that lame, old-fashioned label-affixing fella on their staff with sick leave and medical benefits. Is that his real agenda?

PERSIFLAGE AND FURBELOWS “Trespassers will be shot. Survivors will be shot again.”—Anon “Life isn’t about waiting for the storm to pass: it’s about learning to dance in the rain.”—Ditto; I especially like this one.—RCH “Speak your mind but ride a fast horse.”—Another Anon copied off a wall somewhere “A bird does not sing because it has an answer. It sings because it has a song.”—Another favorite wall scrawl

THE FROTH ESTATE The Alleged News Institution SOMEWHERE IN ALL THE EXCITEMENT lately over the House of Representatives “stripping” food stamps out of the farm bill, an essential aspect of the situation was mostly overlooked by cable-news tv. And the print news media didn’t do much better. I found this sentence buried in the seventh paragraph of the Denver Post’s report: “The food stamp program doesn’t need legislation to continue, but Congress would have to pass a bill to enact changes.” Why was this undoubtedly essential fact overlooked? Because the so-called news media get no mileage out of facts: sensation pays the bills. And it’s far more sensational to interview and quote politicians on how the Republicons are ignoring the nation’s poor and contributing to the starvation of millions of children than it is to report that starvation is still being held at bay by existing law. What was stripped out of the farm bill was a cut in funding for food stamps. Republicons didn’t think the cut was deep enough. They didn’t want to cut the food stamp program; they wanted to gut the food stamp program. David Brooks confessed on July 12's PBS “News Hour” that he’d contemplated writing a column applauding the move as a way of halting our headlong dash to feed undeserving people, but then, he said, he researched a little and found that most of those receiving food stamps qualified for them. They were poor enough.

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Pictures Without Too Many Words HERE, CONTINUING THE PRACTICE of depicting “strong female characters” in skimpy attire, is the variant cover by Paolo Rivera for No.6 of Guardians of the Galaxy. With this chick on call, we don’t need Playboy much anymore. Nice treatment of her right leg—bent, turning inward; very natural.

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping Among my

favorite strips is Tundra, which creator Chad Carpenter has,

through sheer determination (with the aid of a good salesman friend, Bill

Kellogg), managed to self-syndicate to wholly unanticipated heights. Sometimes

the strip is pure nonsense, as in the first strip at hand. (But it reminds me

that I saw a hawk a few weeks ago carrying off a prairie dog in much the same

fashion as the eagle here is carting off the thrilled fish. The prairie dog

wasn’t moving; probably not too thrilled.) And Carpenter does a fair share of

penguin jokes, like the one at the bottom here; I try to save ’em all. But the

middle strip—I don’t get it. I assume the creature that’s been neutered is a

woolly mammoth. That’s his trunk sticking out. So why? What’s it mean? Is that

thing around his neck there in order to prevent him using his trunk for—what?

What obscene thing would an un-neutered mammoth be doing with its trunk? Help. There’s a collection of Tundra called Tundra: the Next Degeneration (2011), published by Tundra & Associates at www.tundracomcics.com. Slick paper, full color throughout. But that’s not why it’s worth a look: rather, because it’s a genuinely funny comic strip, of which we have grievously too few lately. And too many that are all talk, too.

ON JUNE 30, the Sunday Dennis the Menace featured the five-ana-half-year-old terrorist reciting his version of the Pledge to Allegiance: “I pledge allegiance to the flag of the united states of a miracle ... and to the republic for itchy sands ... one nation, under god, irresistible ... with licorice and juice drinks for all.” Sounds good to me.

AND HERE’S

ANOTHER JIVEY WORD GAME. “Jivey” is a portmanteau re-

PITHY PRONOUNCEMENTS “You have a group of people in charge of the House of Representatives that do not believe in gravity. When you don’t believe in gravity, you are unable to deal with renewable energy.”—Washington Governor Jay Inslee at the Democrat Governors Association Meeting in Aspen, Colorado