|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 312 (June 26, 2013). With this hare-raising posting, we launch our Annual Open Access Month: for all the month of July (starting with Opus 312 even though it’s dated June 26), the online magazine Rants & Raves, as well as archived R&R and the entire Hindsight archive—thirteen years of history, lore, reviews and commentary—is open to non-$ubscribers in the hope that they will be so thrilled with what they find that they’ll $ubscribe. Join the happy throng. Our current posting headlines the execrable “Man of Steel” movie. It stinks. That’s the considered opinion of Our Stalwart Reviewer as spewed out copiously. We also report on the recently concluded and impressively successful second Denver Comic Con, the desecration of a Superman shrine in Cleveland, the courage of Syrian cartoonist Ali Ferzat, and the current status of Mike Diana (by reviewing the crime against him). And we review a gem of an animated film, “The Illusionist,” and numerous books, all of which are listed below. This listing, by the way—in case you haven’t already figured it out—is to enable you to scan the contents of enormous postings like this one and pick the articles that interest you so you don’t have to scroll, paragraph after paragraph, through the whole enchilada to get to what you like. Here’s what’s here, then, in order, by department—:

Side of Beef: A Birthday Celebration NOUS R US Action No.1 Found in a Wall Downey to do Iron Man Twice More Archie Bound for the Big Screen Time Turns Off Weekly Online Editoon Spotlight Buck Nekkid in the 25th Century Playboy’s Fraudulent Double Summer Issue James Joyce in Graphic Biography Another Editoonist Raptured

DENVER COMIC CON No.2

Dick Locher Retires

SUPERMAN STUFF In Entertainment Weekly Cleveland Shrines Man of Steel Movie

STORIES OF A CARTOONIST OF COURAGE Syrian Ali Ferzat

A CRIME AGAINST OUR VALUES Mike Diana Returns to Florida

EDITOONERY Some of the Latest Editorial Cartoons With the New Yorker, Too

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Zero Hero by RCH Jack Cole Outside Playboy

BOOK MARQUEE Forbidden Worlds, Vol. 2: Nos.5-8 Black Cherry Ratfist

WOODWORKS: Against the Grain Wally’s World Woodwork: Wallace Wood, 1927-1981 Came the Dawn and Other EC Stories by Wood

Halloween Classics: Graphic Classics, Vol.23 Native American Classics: Graphic Classics, Vol.24

TURNING LITERARY CLASSICS INTO CLASSY COMICS Tom Pompun and Graphic Classics

MOVIE REVIEW The Illusionist

BOOK REVIEWS Daggers Drawn: 35 Years of Kal Cartoons in The Economist The Graphic Canon: Adapting 19th Century Literary Works to Comics Form

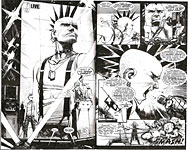

LONG FORM COMICS Graphic Novel Punk Rock Jesus

COLLECTORS’ CORNICHE RCH’s First Published Cartoon

PASSIN’ THROUGH Kim Thompson

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

A SIDE OF BEEF Your old men shall dream dreams.—Acts 2:17 AT SEVENTY-SIX, a milestone I passed a few days ago, I’m pretty sure I qualify as an Old Man. And the dreams I have tend to be of fond moments in the past rather than of glories in the future. I probably qualified as an Old Man when I was merely 65, but then there were fewer past moments to conjure up again than there are now. Among the ones available to me even then, however, is a moment at the Menger Hotel in San Antonio. The Menger is about a block from the Alamo, and it was built in 1859, just 23 years after Davy Crockett and Jim Bowie gave their all for Texas independence. Today’s Menger is an expanded version of the 1859 structure: it has been added onto at least twice since it opened. The old part is still habitable—and its rooms are specious and filled with antiquy-looking furniture and fittings; the next stage of expansion wasn’t quite up to the grandeur of the original, and the last addition is an even cheaper installation. A long lobby stretches from the old part to the newer parts, but the part I remember fondly is the “historic” bar, a replica of London’s House of Lords Pub. On my first visit to the Menger, I was on a site inspection—visiting the city and its hotels as potential sites for a future convention. And I was conducted around the Menger by two sales persons, one from the San Antonio Convention Bureau and the other from the hotel. When we entered the historic bar, the hotel sales lady said that it was here that Teddy Roosevelt first met the officers of his famed Rough Riders, which troops had gathered in San Antonio for “training” en route to embarking for Cuba. There was a bar that stretched along one side of the room; on the other side, clustered some booths (and in my recollection there were a few booths on a sort of mezzanine or loft above the other booths), and in the middle, round tables. All very woody of the dark and mahogany kind. The bar was closed at that time of day; no one was there except me and my escorts. So Teddy Roosevelt met his officers here, I thought, and I gazed around the room appreciatively. And then, standing in the middle of the room, I shouted: “A side of beef for me and my men!” For years, I’d been looking for just the right occasion to utter this imposing command. Roosevelt’s bar in the historic Menger seemed the right place, and the time was convenient.

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits JUST AS WE WERE WINDING UP for this posting, we received the sad news that Kim Thompson, co-publisher of Fantagraphics for 36 years, had died. Over the 30-plus years that I have been published by Fantagraphics (in The Comics Journal and otherwise), I worked most closely with Kim’s partner, Gary Groth, so my personal experience of Kim is too limited to afford me anything insightful to say about him—except that he was surpassingly businesslike in his dealings with me (chiefly over the annotating of the Pogo reprint books); in response to my every inquiry, he was always prompt, concise and complete. And we both loved Franquin. Many others knew him better, and some of those are quoted in the article that concludes this Opus. I hope you’ll go there to get to know Kim through those who knew him well.

SPINNING AROUND A copy of Action Comics No.1, wherein Superman debuted in 1938, was found in the wall of a Minnesota house built during the same year. Found during a renovation, it sold for $175,000, according to comicbook seller ComicConnection. It might’ve been more, but it was graded only 1.5 out of 10 because of a detached cover; a near-mint copy graded at 9.0 sold for $2.16 million in 2011. USA Today reported that Marvel Studios announced June 20 that Robert Downey Jr. has signed a deal to return as billionaire playboy philanthropist Tony Stark and his superheroic alter ego Iron Man for two more movies: the team-up film The Avengers 2, writer/director Joss Whedon's sequel to last year's $1.5 billion hit, as well as The Avengers 3. They will be Downey’s fifth and sixth times playing Iron Man on the big screen. Archie, who, at 72, may now be America's oldest teenager, is headed to the big screen for the first time, at least if a new project at Warner Brothers proceeds as planned. Brooks Barnes at the New York Times reported in early June that Warner closed a deal for a live-action adaptation of the small-town adventures of Archie, Betty, Veronica, Jughead. “As their traditional showcases melt like Arctic ice, the nation's visual commentators have one less mainstream floe to go to,” reported Mike Cavna at ComicRiffs. “Time magazine is discontinuing its popular Cartoons of the Week online feature, according to several sources. The most recent COTW published on Time's site was for mid-June.” Sad, but you have to admire Cavna’s metaphor. Hermes Press is launching a 4-issue series, Buck Rogers in the 25th Century, done by Howard Chaykin, who is reknowned in these parts for scabrous sexual adventure comics. I can’t wait. If past performance is any indicator of the future, we can look forward to Wilma (who, Chaykin protests, is merely Buck’s colleague, not a romantic interest) in garters and bustier and Buck buck-nekkid much of their interplanetary time. Playboy’s “summer issue,” dated July-August, is out. The touted “double issue” is double only in the sense that it offers two Playmates instead of one: by page count—208 pages this time vs. the customary 150 pages of late—this issue is only 35% larger than the usual issue. But it does have a two-page spread of 8 previously published Dedini cartoons, some of the funniest of his oeuvre (but none displaying his love of design particularly).

GRAPHIC NOVEL OF A NOVELIST’S LIFE James Joyce, Portrait of a Dubliner, is purported by John Spain at the Irish Independent to be “a remarkable depiction of the Dublin of the author’s time, his family, his friends, his travels in Europe and how he overcame poverty, rejection and ill-health to create some of the greatest works in the English language” (the stream-of-consciousness novel Ulysses for one). But “the core of the book” is its depiction of the James’ “all-consuming love” for his wife, Nora. “As is usual in graphic novels, the love affair is shown in an explicit manner at some points, including sections showing them cavorting together in the nude on Howth Head and naked on a bed in the town of Pola, now in Croatia.” Probably, unless I miss my guess (which I have done at least once before), the book does not record the event of their first date which no doubt contributed to James’ infatuation with his wife-to-be: she reached under the table at the pub and into James pants to jack him off. Nor, probably, does it reveal that Joyce, who drank considerably, “overcame” his poverty by begging money from his friends. According to Spain, the 228-page book has thousands of drawings “and the surprising thing is that the book is not the work of an Irish artist, but a young Spanish illustrator and Joyce admirer, Alfonso Zapico.”

ANOTHER EDITOONIST RAPTURED Sean Delonas, The New York Post‘s veteran Page Six editoonist, is taking a buyout after 23 years at the paper, he announced on his Facebook page: “Almost 23 years ago, I took a temporary 3 month job cartooning for The New York Post. Nearly 6,000 cartoons later, I’ve drawn my last cartoon for the paper. I’ve accepted a buyout. I’d like to thank all my colleagues for the great memories. I have nothing but gratitude for Mr. Murdoch and the Post. I believe the paper has a bright future and I look forward to reading it for many years to come.” “During a long career at the Post, Delonas was definitely un-PC,” wrote Kara Bloomgarden-Smoke at observer.com. “His cartoons for the tabloid at times attracted controversy—like his 2009 cartoon of cops shooting a monkey, while quipping that they will need to find someone else to write the stimulus bill, prompting cries of racism since Delonas seemed to be equating a chimp with President Obama.” Delonas plans to continue editorial cartooning by posting three new cartoons each week, with commentary, on his website. Delonas’ departure from a full-time staff position brings the national total in that category down to 51, a drop of 50% in five years.

DENVER COMIC CON THE SECOND Larger and Better THIS YEAR’S DENVER COMIC CON, May 31-June 2—the second annual fest—tallied about 48,000 attendees. More or less. Topping last year’s near-record-breaking 27,000. (A first con crowd second only to New York’s inaugural a year or so ago.) The Con moved to a much larger venue in the Denver Convention Center; the Food Court alone was about the size of the exhibit hall last year. In the aisles of the exhibit and Artists vAlley, the milling throng never thinned: all day long, for three days, the populace eddied through the displays. At

your eye’s elbow is the cover of the Denver Comic Con program booklet—by Scott

Campbell, and nicely done even if most of the women depicted are not attired in

skimpy underwear costumes. Next in the array of accompanying visuals is the big blue bear in all its actuality. The people strolling by give you an idea of the bear’s size.

And the second views of the bear are from inside the Center, where you can see one of the sights the bear sees—a statue of Superman launching himself skyward. Stan Lee, who had been signed on as a guest of honor during last year’s inaugural extravaganza, reneged the week before the Con in order to make a cameo appearance in a Marvel movie being shot at a conflicting time. William Shatner took his place. “As a result of playing Kirk—and as a result of being a celebrity—I am here taking over for Stan Lee,” Shatner said, “—who else would they have called?” Before taking to the stage to address a packed auditorium, the Denver Post reported, Shatner signed a Star Trek communicator toy for a terminally ill 9-year-old boy who couldn’t attend the event. Another “Star Trek” hero, George Takei, was also a celebrity guest. He arrived early on Friday and stayed late that night to sign autographs for all those who had been waiting in line to pick up their badges. “Many people said this was the only day they could be here, so that is why I stayed,” he said. The Friday crowd was too much for the city’s fire marshal. The doors opened at 3 p.m., but two hours earlier, a line of people estimated at 15,000 began snaking around the Convention Center, spilling across downtown Denver. The fire marshal reacted by shutting the doors, leaving (it sez here) 6,000 angry fans on the sidewalks. Con officials admitted that the size of the crowd on Friday took them by surprise. But while a couple thousand might have been stranded outside, I think 6,000 is an exaggeration. Many of those admitted were just getting into the exhibit hall at 8 p.m., the announced closing time. The Con crew kept the hall open another hour to give the recent arrivals a chance to see some of the displays and exhibits. By Saturday morning, Con operatives responded to the large numbers by adding staff in the registration area (some of whom went up and down the lines, checking people in and issuing badges). Saturday and Sunday was a smoother operation; and no one was left out on the streets. Complimenting the exhibits of comics, games, toys and other pop culture phenomenon, the program featured about a dozen simultaneous panel presentations and lectures and the like every hour—comics, tv/film, manga/animation, celebrities, education/diversity (the Con is sponsored by Denver’s Comic Book Classroom, a non-profit program teaching reading skills through comics to kids in economically straightened neighborhoods), gaming and cosplay, to mention some of the themes taken up in the Center’s meeting rooms on the floor below the exhibit hall. As with the San Diego Con and others of the ilk, many of the guest celebrities were from tv and film, but at least as many were comics personalities—Alfred Trujillo, Brian Pulido, Chris Ware, Denny O’Neil, Gerry Conway, George Perez, Doug TenNapel, Farel Dalrymple, Fiona stapes, J. Scott Campbell, Andrew Pepoy, Jim Mahfood, Jim Steranko, Joe Rukbinstein, Neal Adams, Jon Bogdanove, Matt Wagner, Mike Baron, Moritat, Ramona Fradon, Allen Bellman, Paul Ryan, Peter Bagge—and more. In short, it’s clear that the DenComCon is now a destination for comics creators and fans of comics as well as pop culture, tv and movies.

I WAS ESTABLISHED AT A TABLE in the usual habitat for cartoonists and artists. In recognition of the venue being near Colorado’s majestic mountains, Artists Alley here is called “Artists Valley” (probably because it's between peeks). The table next to mine was Allen Bellman’s, and he and his wife Roz held forth like yoemen all day for three days (and he’s 89). Bellman is one of the nearly forgotten comic book artists of the Golden Age. He joined the Marvel (then Timely) bullpen in 1942 at the age of 18 and did some backgrounds in Syd Shores’ Captain America. He also worked on the Human Torch, the Patriot, the Destroyer, and the weirdly named World War II hero, Jap-buster Johnson, among other characters and titles, and he wrote and drew a one-page feature, “Let’s Play Detective,” but it was his almost parenthetical contribution to Captain America that has underwritten his appearances at comic cons since about 2007. After his stint at Marvel, he worked for Gleason comics in the early 1950s; then after a while, he was freelancing for Marvel. But he left comics in about 1952, and following a brief career in illustration, he went to Florida where he joined a Florida newspaper as a photographer. Then in 2007, a couple of funnybook fans found him and persuaded him to venture forth into the burgeoning business of being a Golden Age celebrity at comic cons, where he appears as a Captain America/Human Torch artist. “This is what I live for now,” he told me, nodding at the milling throngs passing by his table. And it is a lively living: he signed autographs (often on cosplayers’ Captain America shields) and sold energetic sketches of Captain America and talked with whomever stopped to chat. I asked if I could photograph him with his cane, the grip of which, as you can see, is a Jaguar hood ornament. “Never could afford the car,” he quipped, “—this is as close as I could get.” He struck his comic con pose—fist defiantly, victoriously, thrust at the photographer. When little kids wanted to be photographed with him, he instructed them in how to do the fistic pose, and they did it together.

The table across from Bellman’s and also capping the end of a row of Valley tables was Ramona Fradon’s, and across from hers was Doug TenNapel’s. I’m a fan of the work of both of them. I told Fradon that I thought she did the best Plastic Man of the Silver and subsequent Ages. TenNapel’s

storytelling and rendering is among the most wildly kenetic in comics, and I

went over to his table to see what he was selling. I wound up buying three of

his graphic novels—Gear, Ratfist, and Black Cherry, “a lurid tale

of sex, violence and the supernatural” it sez on the cover (“I did this one

especially for you,” TenNapel said; so how could I resist?). I bought Gear partly because of the stunning color inside and also because it is TenNapel’s first work: it collects the six issues of the comic book title he published in 1998. “There are no people in this book,” I observed, displaying my uncanny observational skills. “That’s because I didn’t know how to draw people then,” TenNapel explained, adding that after Gear was published, he submerged himself in months of self-instructional exercises to develop an ability to portray others of his own species. Gear is dubbed a “surreal epic” for which TenNapel looked for inspiration to his pet cats, Simon, Waffle, Gordon and Mr. Black. The cats do battle with dogs and insects, using giant robots as weapons. The cats went on to star in the Nickelodeon series “Catscratch.” TenNapel began as an animator and was soon working on video games, all of which led to producing graphic novels, which he’s done at the rate of about one a year until, now, there are 13. According to Wikipedia, “he is best known for creating [in 1994] Earthworm Jim, a character that spawned a video game series, cartoon show, and a toy line.” TenNapel lives in Colorado Springs these days, so he’s close enough that he brought his entire family (wife and four kids) with him to Denver for the Con. While we were talking, his wife said she wanted a photograph of the two of us, and TenNapel readily agreed, standing up and coming out from behind his table. What a shock. I’ve run into him several times at the San Diego Con, but he’s always been seated at a table. Suddenly, I was confronted by a six-foot eight-inch hulk, standing by my side.

Later, as you can see from the visual aids just posted, I decided he’d be a perfect subject for caricature. True, but he was more difficult to capture than I thought he’d be, but I finally managed it and then transferred the image to my Artists Alley gimmick. Some years ago, I made prints of several of my magazine cartoons, removing the heads of the male characters. The gimmick is that for a modest fee, I do a caricature of the buyer and put it in the place where the head had been, making the caricatured custoemr a cartoon character—surely the goal in life for every comics fan. I also did a special drawing for the purpose—a rendering of a muscle-bound hero who is rescuing a damsel but is so clumsy in handling her that he nearly disrobes her as he rescues. It was onto this print that I put my caricature of TenNapel. I gave him the final product; the one you see here is my first attempt. Not bad, but not, yet, very good. Almost everyone who sees this gimmick in the display of headless cartoons and drawings that I arrange for my Artists Alley stints agrees that the gimmick is brilliantly conceived. But almost no one ever buys one.

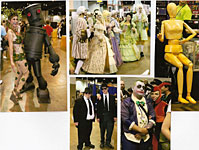

THE PARADE THAT IS THE CON continued to stream by my table and throughout the Valley and the hall all day for two-and-a-half days. I was vastly amused by the number and variety of cosplayers. My guess is that one of every five people attending the Con was in costume, playing the part of a favorite tv or movie or cartoon character. Zombies were numerous. And Star Trek warriors. I was surprised by the quantity of steam punk fashions on display. But I wondered as I watched: do any of these colorfully costumed persons ever buy anything offered for sale throughout the Con? None of the cosplayers I saw were carrying bags bulging with purchases. They were all playing but, seemingly, not buying. Still, when I asked some friends from my favorite comic book shop, they said they’d experienced great sales. No one complained. T-shirts were also big. One exhibit booth was a “tower of t-shirts,” reaching a height of at least twenty feet. T-shirts are expensive—at least $25 each, sometimes more. Merchants must charge high prices these days because the men’s clothing industry isn’t making anything on regular shirts anymore: everyone is wearing t-shirts all the time. Casual Friday has exploded into Casual Week and all but destroyed the men’s clothing business and the surrounding economy as it did. As a results, t-shirts rule, and they’re priced to prop up the entire sagging men’s shirt industry. I attended only one presentation over the weekend: Kevin G. Robinette (who lives in Denver but commutes once a week to San Francisco to teach a course in comics at a local college, which pays his expenses) talked about comics 50 years ago. In 1963, he reported, the comics industry, which many of us have assumed was dead after the Wertham-inspired “kill off” of 1954-55, was producing 296 titles a month. Most of these (21% Robinette said) were humor comics, featuring humans and tv characters. Next, with 19%, was the funny animal category; then teenagers (13%), westerns and superheroes (11% each), then war and romance (each 8%), and, finally—at the low end with merely 1%—crime. Wertham prevailed. Back in Artists Valley, I took photos of the passing throngs, some of which I’ve posted in this vicinity. See how many of the following you can find in this array: steam punkers, strangely religious paraphernalia on display, mobs, Captain America and Wonder Woman, Poison Ivy, a gaggle of 18th century French dandies and their well-coifed bimbos, a chubby Joker and a plump Superman, Harley Quinn, an artist’s model, Alice and the Mad Hatter, Hagar (?), and more. Wait’ll next year.

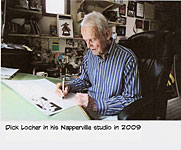

DICK LOCHER RETIRES AFTER FOUR DECADES OF EDITOONING By Scott Stantis, editorial cartoonist for the Chicago Tribune; May 20, 2013 PULITZER PRIZE-WINNING editorial cartoonist Dick Locher, 83, has put the stopper in the ink bottle for the last time after more than 40 years of capturing modern life through political cartooning. He recently announced his retirement. Dick's

career as an editorial cartoonist began inexplicably in 1973 when he was

offered the staff cartoonist position at the Chicago Tribune even though

he had no experience in the job. (He had assisted on the comic strip Dick

Tracy for many years with legendary cartoonist Chester Gould, who

recommended him for the Tribune job.) Over the years Dick had more than

10,000 cartoons published ("That's a whole lot of getting mad six times a

week," he said); won a bunch of awards, including a Pulitzer in 1983; had

a private lunch in the Oval Office with President Ronald Reagan; received two

death threats; took over drawing and writing the Dick Tracy strip (he retired

from that job in 2011); created the coveted John Locher Award for college

cartoonists to honor the memory of his deceased son; and designed the Land of

Lincoln Trophy, awarded to the winner of the Illinois-Northwestern college

football game. In

an era many consider the golden age of editorial cartooning, his work stands

among the greats. His cartoons have been nationally syndicated by Tribune Media

Services and featured in Time, Newsweek, Playboy, the Congressional

Record, Life and hundreds of newspapers internationally. Always a gifted

draftsman, his work was studied and emulated by generations of aspiring

cartoonists, myself included. Dick's work is remarkable for the power of his message

and his fearless graphic sense. What I admire most is not his incomparable resume, his wall of awards and plaudits or his ceaseless flow of creativity, be it painting or sculpting, (as I write this he is in the middle of completing a sculpture of the founder of Naperville), or even the fact that he is tall, slender and handsome to this day. What comes to my mind is a word we rarely hear, let alone use today: courtly. For all of his accomplishments I have never known Dick Locher to be anything but kind, generous with his time and always a gentleman. My respect and admiration for him is boundless. In short, when I grow up I want to be Dick Locher.

***** Feetnoots by RCH. Good work, Scott. Take the rest of the day off (as Dick was wont to quip by way of congratulating a noble effort). Dick is not only courtly but witty, a pleasure to be with and to listen to. I interviewed him several years ago, and the career-spanning result is posted in Harv’s Hindsight for March 2011. Some of Dick’s favorite stories are enshrined therein; don’t miss it if you can.

SUPERMAN COVERS ENTERTAINMENT Awash in

blockbuster movies of comic book superheroes over the last few years, Entertainment

Weekly periodically puts one of the funnybook longjohn legions on its

cover. The current issue (cover herewith) celebrates Superman’s 75th anniversary as a comic book character—and, of course, the opening of the new

blockbuster Superman flick. “Man of Steel” raked in $113 million on its opening

weekend ($125 mil if you count Thursday “screenings”; still well below “The

Avengers” record of $207.4 million but surpassing “Toy Story 3's” $110.3

million as the best June opening of all time). Only

two versions of the comic book Superman are depicted across the bottom: on the

left, Joe Shuster’s iconographic rendering (his was, after all, the very

first interpretation of his friend Jerry Siegel’s super-powered

concoction); on the right, Jim Lee’s. The big Superman on the cover is

by Neal Adams. Inside, a two-page spread lays out 18 different Supermen,

actors and comic book characters. Boring and a number of other Golden Age DC artists were summarily dismissed in 1967-68 when the company purged itself of the “old school” artists. Too bad. The purge was directed by the legendary malcontent, Mort Weisinger, who called Boring into his office and told him he was fired. Boring related the details to Richard Pachter in a 1984 interview (published in Amazing Heroes): “You mean I’m not working for you anymore?” “You’re fired,” Weisinger repeated. “Fired?” Boring, flabbergasted, persisted: “What do you mean? All you’ve got to do is stop sending me scripts.” (Why, in other words, use the word “fired”?) Weisinger went on: “Do you need a kick in the stomach to know you’re not wanted?” Wonderful fella. Said Boring: “I was kind of down—after 30 years!” As for his opinion of Weisinger: “I was afraid I’d die and go to hell and he’d be in charge!” Boring joked. “That would have been the capper!” Boring dabbled in comics for other publishers for a while, then retreated to Florida where he found a part-time job as a bank security guard. He died in 1987 of a heart attack. We’ll stage a retelling of the birth of America’s first and most ubiquitous longjohn superhero in Opus 313 (in July, during the rest of our Annual Open Access Month); one or two possible surprises, perhaps. To tide you over, here’s a short squib about Superman’s creators—:

THE SHRINE BULLDOZED AGAIN For the second time in two years, one of Cleveland’s four shrines to its spandex-clad native son has been desecrated by a driver who lost control of his vehicle. The first of this noteworthy quartet is at the city’s Hopkins International Airport: erected last October, an imposing statue of Superman stands at attention (his usual posture) in front of a verbal mural proclaiming Cleveland his birthplace. And near the clock tower at the corner of East 105th Street and St. Clair Avenue is a two-sided imitation bronze historical marker honoring Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, Superman’s creators. Set up in 2003 on the 65th anniversary of the Man of Steel’s birth, the marker manages to misspell Siegel’s name on one of its two sides. The $2,500 marker was sawed off its post and stolen last year; but the thieves returned it three weeks later, undamaged (Siegel’s name still misspelled). The house where Siegel lived when he invented Superman during a hot, sleepless night in 1933 is the third shrine. At 10622 Kimberly Avenue, just three blocks from the marker on East 105th, it was designated a landmark by the city in 1986, but it wasn’t properly refurbished until 2009, when Brad Meltzer, who’d written The Book of Lies (a sort of novel based upon supposed mysteries—among them, the death of Siegel’s father a few years before Superman was born), visited the site and, alarmed at its shabby condition, worked with the Siegel and Shuster Society (formed in 2007) to rise $111,000 for renovating. (At BradMeltzer.com, a video reportedly depicts the condition of the place before it was refurbished; I couldn’t make it work on my machine, but then, I’m notably inept at technology.) The

couple that has owned and occupied the house since 1983 is apparently delighted

by all the attention their home gets—bus-loads of passing tourists and

occasional drop-in visitors (who, if Jefferson and Hattie May Gray aren’t too

busy at the moment, might get to peek inside at the attic room where Siegel

liked to work in seclusion and where the Grays display Superman memorabilia

they’ve collected). At the time of the renovation, an “S” plaque was affixed to

the fence in front of the Gray house. The fourth Superman shrine is at the corner where Armor Avenue deadends at Parkwood Drive, the site of the apartment building where Joe Shuster lived, eleven blocks south of Siegel’s house. It was to Shuster’s that Siegel ran the morning after his sleepless night conjuring up Superman, eager to tell the young artist about this new creation; Shuster, acting upon Siegel’s prompts, then drew the first depictions of the pace-setting superhero. The

apartment building was torn down in 1974, but the Siegel and Shuster Society

built its shrine around the private home that was built there in place of the

apartment building. Raising money with an online auction, the SSS had the first

Superman story from Action Comics No.1 transferred to metal plates,

which were then hung on a fence at the property. Portions of the fence have twice been demolished by errant drivers, most recently on June 5, when Antwann Houston veered off Parkwood into the left half of the V-shaped fence shown in our visual aid, taking down also the corner plaque depicting Siegel and Shuster and describing their creation. Houston was charged with drunken driving, leaving the scene of an accident and driving without a license. The family that lives in the house behind the fence collected the plates; at least one has been badly damaged. The previous demolition took place in May 2011, when a neighbor drove his car through the other half of the V-shaped fence. The damage then was estimated at $2,600. The plates were replaced. And where was Superman when all this destruction was transpiring? In the movies. Which brings us to—:

“MAN OF STEEL” HAS ALMOST NO REDEEMING FEATURES as a movie. It may, in fact, be the worst action movie I’ve ever seen. The fight sequences were supersonic car crashes with the opponents rushing headlong at each other and knocking one another down repeatedly. And they moved too fast for a viewer to follow the presumed action; all we see is visual representations of a high wind. After a dozen or so of these head-on collisions, ennui sets in pretty numbingly. Some relief from the noise of the crashes is afforded in several nearly endless expanses of exposition. For an action movie, there were far too many extreme close-ups; we don’t need to count the hairs of Superman’s eyebrows. Apart from the wholesale destruction being wreaked on the cityscape during fights, we were also treated to unremitting sequences of slow moving—but menacing—space craft that looked like metallic crabs or sea turtles or hovering jelly fish, sequences punctuated by belching firey explosions of the highest decibels. British actor Henry Cavill is adequately stalwart and muscled heavily enough for the Superman role. The Superman’s chain-maily sort of costume is the best thing in the movie, but the cape is too long. Alas, Amy Adams is wrong for the part of Lois Lane: instead of a hard-charging reporter, we have a prom queen. Lois and Clark fall in love and, at the end of the movie, they kiss. This development severely alters the Superman mythology, in particular the love triangle that has animated the comic books for 75 years—Lois loves Superman but disdains Clark Kent, not realizing that the two are one and the same. I can’t imagine how DC consented to the violence this development does to the enduring psychic appeal of the character: every pimply-faced adolescent under the spell of the Siegel-Shuster creation can imagine that he, like nerdy Clark Kent, is secretly a champion. This movie blasts that fond daydream to tiny pieces of Kryptonite, thanks to writers Christopher Nolan and David S. Goyer, ably assisted by director Scott Snyder. The best scenes in the movie belong to Clark and his mother, feelingly played by Diane Lane. They seem unabashedly fond of each other, and their obvious affection lends their scenes emotional impact—about the only human drama around. All of the rest of the intended drama is drowned in cliched dialogue. But the movie’s most serious flaw is its relentless seriousness. The idea of a flying, invulnerable super-powered hero is laughable on its face, but most successful superhero movies of late have the saving grace of a self-deprecating sense of humor. None of that here. In fact there are only two funny lines in the two-and-a-half hour flick, and they’re both Lois’. She arrives at some frozen outpost of scientific inquiry to report on it, and endures a typically masculine us-guys-know-it-all-but-you-poor-deluded-female briefing, which she finally terminates with a quip: “Now that we’ve finished measuring dicks, maybe we can begin.” And the penultimate line in the movie is hers, and it is also humorous with double entendre. At the end of the movie, Clark decides to find a job, and he dons specs and reports to work at the Daily Planet, where Lois is the star reporter. When he is introduced to her, she pretends she doesn’t know him—despite having been gaga over him for the whole movie—stands up and shakes his hand and says: “Welcome to the Planet,” a nice play on words. The movie also supports what appears to be a stunning irrationality. If Clark is invulnerable because he comes from a planet with a different atmosphere than Earth’s, then all those Kryptonites who come looking for him with kidnaping on their agenda are similarly invulnerable. How, then, are they all killed? But they are. Some unspecified how. And Krypton’s General Zod laments their death and vows to kill all of Clark’s earthling cohorts in revenge. Clark finally dispatches the evil warlord by choking him to death, the only way he can be killed if he’s otherwise invulnerable. That seems to work. But how were all the other Kryptonites killed? Oh, and—according to Asawin Suebsaeng at motherjones.com—“one of the most fascinating things about this movie is how blatantly littered with product placement it is—roughly $160 million in product placement and promotions went into its makers' coffers. ‘Man of Steel’ has over 100 global marketing partners, surpassing Universal's 2012 animated flick ‘The Lorax,’ which reportedly had 70 partners. So if you have forgotten recently to eat at IHOP or to shop at Sears, this film will remind you to do so in big letters.” But the most troubling aspect of this production for me is the flying. Advertisements for the first Superman movie of modern times touted the flying: it was so convincingly faked that we would know, the ads insisted, that Superman can fly. This Superman takes flight like a bullet being fired. No flapping of arms, no quick crouch and then a jump up into the air. Nothing. Just—bang! out of the chute. What propels him? The only thing I can think of is, well, super flatulence. Superman farts himself into flight. And that seems a suitable end for this review. (Unintended word play—but relished nonetheless.)

QUOTES AND MOTS “We have to admire the world for not ending on us.”—Colum McCann Comedy springs from irritation: “That’s what comedy’s about. It’s the oyster that takes the irritating grain of sand and turns it into a pearl.”—Jerry Seinfeld

STORIES ABOUT A CARTOONIST OF COURAGE Updating the Adventures of Ali Ferzat (Reuters, summer 2012—a year ago) - Cartoonist Ali Farzat's hand glides over the paper, once more creating the images of defiance he says have helped mobilize Syrians to revolt against President Bashar al-Assad. Just over 12 months ago, the Syrian was kidnaped, beaten and burned in an attack he blamed on Syrian security police trying to silence him and stop him drawing the caricatures that protesters have waved aloft as they took to the streets. His

hands were smashed and he suffered facial burns, temporary loss of his eyesight

and multiple broken bones. One of Syria's most famous artists, Farzat earned recognition in the Arab world and beyond for stinging cartoons of Arab leaders such as Libya's Muammar Gaddafi and Iraq's Saddam Hussein and finally, Assad. Farzat, 60, escaped to Kuwait to recuperate. Now in Egypt, which overthrew its own president in an 18-day uprising in 2011, Farzat told Reuters he was determined to continue his work and support those still seeking to topple Assad 19 months after they began. "Everyday the revolution inches a step forward. I am very optimistic. Do you see anyone turning back?," he said, proudly gesturing with his hands to show they were back in action. "Fear has been defeated in Syria when the people marched 19 months ago against tyranny. "I began to directly draw people in power including Assad and his government officials, to break the barrier of fear, that chronic fear that Syrians suffered from for 50 years." One of his first cartoons portraying Assad—long a taboo in Syria––showed the president reluctantly ripping a page off a calendar on Thursday, knowing that Friday would bring another wave of popular protests to the streets of Syria. In another, Assad tries to hitch a lift with Gaddafi, and a third shows Assad beside a large armchair, unable to sit down because the springs have broken. [For other Ferzat cartoons done before the beating, see below.—RCH] Demonstrators carried banners of his work as new-found expressions of resistance. Farzat, who now works for Kuwait's al-Watan newspaper, has been denied entry into Iraq, Libya, Jordan and Oman because of his work. The uprising against Assad, whose family has ruled Syria in autocratic fashion for four decades, began as a peaceful protest but soon degenerated into civil war as Assad tried to exert autocratic control. More than 32,000 Syrians have been killed [at the time of this story’s publication, mid-June 2013, 90,000-plus]. Farzat said Assad initially tried to get him and other Syrian artists on his side, promising reforms to all but, he said, setting up a system of patronage to win the loyalty of some and exclude those who resisted him. "On a personal level we found Assad contradictory. One day, we would speak and agree on a specific issue. The next day we would find out he had changed his mind," said Farzat, recalling the day he decided to take on Assad in his work. "Satirizing a dictator empowers the masses. It strengthens them and undermines their enemy," he said. Assad says he is pursing reforms, but the opposition says they are meaningless without genuine participation. Sitting on his desk in a building overlooking Tahrir square, the heart of the uprising in Egypt, Farzat sketches on white paper. A tiny bird emerges, chipping and breaking off the head of an axe that sticks out of a Syrian military fatigues, a symbol of Assad's power. He quickly draws a tank unable to roll over a flower that blocks the tank from moving forward. These sketches and others will be showcased in his independent magazine Al-Domari, meaning the Lamp Lighter, which he plans to relaunch in Egypt. The magazine, which was founded in 2000 during a brief period of media freedom, was forced to shut down by Assad's government in 2003. "The magazine's purpose is to gradually remove the darkness that befell our Arab world," said Farzat. He hopes to form a symposium with young artists and cartoonists in Egypt to support the art movement that grew out of Egypt's uprising. "These cartoons stem from the sorrows of people. They give them courage and determination," said Farzat.

A Year Later: Cartoonist Still Stands Up to Syrian Regime By John D. Sutter, CNN Opinion columnist, who interviewed Syrian cartoonist Ali Ferzat in Oslo, Norway, where Ferszat was regrouping after his ordeal; story dated May 21, 2013. THE MASKED HENCHMEN grabbed three fingers on each of the Syrian political cartoonist's hands and pulled them back all the way—so far that they cracked. "Break his arms so that he doesn't ever draw again," one said. Ali Ferzat—the cartoonist who described the 2011 attack to me in a recent interview—soon found himself bleeding and left for dead near the Damascus airport. His assailants, who he believes were acting on behalf of the Syrian regime, dragged him alongside a moving car. His head and shoulder bounced on the pavement and then the men shoved him out of the vehicle, dumping him on the side of the road. Ferzat wondered if he would live, let alone draw again. It would be months before he would learn the second answer. Before I'd heard these and the other horrifying details of this attack against one of the Arab world's most notable artists, I asked Ferzat—an Arab-Santa-looking character with a smile that could cheer up Tilda Swinton [a European actress noted lately for sleeping in public as part of an artwork]—if he was sure his hands were broken to stop him from drawing cartoons critical of Syria's leader, Bashar al-Assad. His answer made me laugh. "Obviously," he said. "What do I look like to you, a chef?" I met Ferzat in at the Oslo Freedom Forum, a gathering of dissidents and human rights activists, where he received the Vaclav Havel Prize for Creative Dissent. Being in his presence was the human-rights nerd version of a basketball fan meeting LeBron. But what impressed me most about Ferzat is that he's maintained his wit and cheer despite the darkness that has fallen on him and on his country, which is in the grips of an intractable two-year war that's killed an estimated 80,000 people [over 90,000 as of this writing, June 15]. He is almost naively optimistic about Syria's future. And it's infectious. The rest of Syria's opposition should take note. As his story shows, the true strength of a revolution is in its ideas—in nonviolent actions such as drawing truth to power. Dictators do have reason to be scared of cartoons. That's why Ferzat's hands became some of the most feared objects in Syria. "They came after me," he said. "Obviously (cartooning) has power." The self-taught artist, who's in his early 60s, has been using them to mock authority since he was a young boy—first imitating cartoons he admired and then creating satire of his own. He went pro in the 1970s, gaining notoriety for publishing cartoons domestically and internationally. Back then, before the current war, Ferzat never dared to depict specific people in his cartoons. He drew autocrats and dictators, but they never looked like real, identifiable people. He did it to avoid censorship or retaliation. But that was before the war—before reports emerged, in May 2011, that a 13-year-old had been tortured and killed in Daraa, Syria. Stories like those of Hamza Ali al-Khateeb's death, which reportedly involved his genitals being mutilated, pushed Ferzat across a threshold. He started to draw exact likeness of al-Assad in his satire. Enough was enough. His pen would hold no punches. Ferzat drew al-Assad standing on the side of the road with his thumb in the air, ready to hitchhike out of Syria. A crazed Moammar Gadhafi, who was still alive at the time but later would be killed in Libya's uprising, was driving a getaway car. The message was clear: Syria's leader had to go. That was the image, he told me, that led to his attack on August 25, 2011. Ferzat's animated demeanor—his eyebrows bounce when he talks and his hands, now unbandaged, gesture wildly—flattened as he told me the story. That day, a white car with darkly tinted windows followed him out of the studio before dawn. He's been working there by candlelight to avoid detection. Frightened by the car, he drove to the center of Damascus, to a square he knew to be home to government buildings and the president's palace. The car followed and crashed into him at the square, he said, forcing him stop. Three men emerged and yanked off the doors of Ferzat's car. They pulled him from it, beat him with crowd-control batons and then yanked plastic handcuffs around his wrists. "They handcuffed me so tightly I felt that one of my wrists was going to break," he said. SANA, the Syrian state news agency, reported Ferzat "was attacked by veiled people" and that "authorities concerned are conducting an investigation." My e-mail requesting further information, however, was not responded to. And the U.S. State Department condemned the attack, saying in a statement that the al-Assad regime was sending "a clear message that (Ferzat) should stop drawing." They beat him so badly that his vision failed for days in one eye, Farzat told me, and he could barely see out of the other. Confused, Ferzat asked what was happening to him. "Don't you ever dare to cross your bosses and to cross your leaders, because Bashar al-Assad's shoe is on your face and on your head." (For evidence of the severity of that insult, recall the Bush and Ahmadinejad shoe-throwing incidents). They drove 30 minutes to a road near the Damascus airport. That's where they threw him from the car. "My white shirt was completely, totally, red from the blood," he said. He thought he surely would bleed to death there. Cars wouldn't stop, perhaps afraid to pick up a person targeted by the regime or by police. But then the first of three miracles happened: A truck's tire burst, forcing it to stop exactly in front of Ferzat. "This is like something out of a freakin' movie," Amir Ahmad Nasr, a blogger-author friend who was translating the conversation from Arabic, said to me. Ferzat threw himself into the bed of the pickup and begged the three men who drove it to take him back to the city. They agreed to drop him at the gates of Damascus, but wouldn't take him further—definitely not to a hospital—for fear of being targeted themselves. Still bleeding and barely able to see because of the beatings to his head, Ferzat wandered up to a house and asked its guard for help. Then the second miracle: The guard agreed to give him a ride to a nearby clinic, where (here's the third) doctors recognized the cartoonist and were sympathetic to his cause. They treated him at his house to avoid detection. But there was always the worry: his hands. Would he draw again? "My hands became stuck like this," he told me, tensing up his digits into a wooden, claw-like shape. "The doctors told me I needed to get treatment overseas." Fate, again, would intervene. Using a newspaper contact in Kuwait, Ferzat arranged to leave Syria and seek treatment in a hospital there. After six months of surgery and physical therapy, he was able to put pen to paper. The first cartoon he created after the attack was not diluted by fear. He drew al-Assad and Russia's Vladimir Putin walking side by side, their legs intertwined to make the shape of a Nazi swastika. Ferzat is still living in exile. But the revolution needs him. It needs his art. He's seen images of protesters and rebels carrying printouts of his drawings. So he contributes art from outside the country. The outcome of the war in Syria is anything but sure. But talk to Ferzat and his optimism will rub off on you. He's convinced he will live and draw in Syria again—that people in his country, a cradle of civilization that invented one of the world's first alphabets, are no longer afraid and eventually will triumph over the regime that would crush their spirits and their art. After hearing his story, I'm hard-pressed not to believe him.

A CRIME AGAINST OUR VALUES As the first artist ever to be convicted of criminal obscenity in the U.S., Mike Diana is the central figure in what should be roundly condemned as a national disgrace. He was convicted in Florida, a state infamous for its backwoods attitudes about sex and race (among other dubious achievements), and his conviction enjoyed considerable publicity at the time (1996-97) as an outrageous instance of police power gone amuck in a society of antiquated sexual mores. The case against Diana materialized under highly suspicious circumstances that suggested he had been targeted by an ambitious assistant state’s attorney, who, understanding perfectly the troglodyte attitudes of Floridians on matters of sex, saw Diana’s self-published comic book efforts as flagrant assaults in the moral sensibilities of a population he regarded chiefly as voters. Subsequently, in a Largo, Florida district court, Diana was found guilty on three counts, and was sentenced to a three-year probation. He was to avoid all contact with children under 18, undergo psychological testing, enroll in a journalistic ethics course, pay a $3,000 fine, and perform 1,248 hours of community service. He was also ordered to cease drawing even for personal use, and his home was to be open to visitation by the police, who, without warning or warrant, could enter the premises at any time, to discover if he was violating this ruling. He was not sentenced to any jail time, but spent four days in jail between the dates of the verdict and the sentencing. At the time, the sentence was widely decried as a draconian denial of the principles upon which this country was founded, an odious offense against individual liberty and democratic ideals, including, most obviously, freedom of speech and artistic expression. Just down the scroll, I’m posting a recent Miami News Times story by Liz Tracy because we need to be reminded about how frail our grip on so-called liberties is. And because Diana relates some aspects of his horrendous legal execution that I hadn’t heard before. Diana’s whole story is posted at Opus 284, and I recommend that you re-visit that posting to refresh your memory of just how high-handed and unjust the entire adventure was. Then come back here and continue reading (below) about Diana’s latest adventures, which includes his description of his initial encounter with the long arm of Florida law and his reaction thereto and subsequent episodes, revisited.

Mike Diana Returns to the State That Convicted Him of Obscenity By Liz Tracy at the Miami New Times; Thursday, May 16, 2013 WHEN 18-YEAR-OLD MIKE DIANA RETURNED HOME from Christmas shopping with his mom in 1990, two cops were waiting for him on the lawn of their home in Largo, near Tampa. One officer pulled from his briefcase the teenager's underground comic book Boiled Angel No.6. He flipped through the pages, showing Diana’s mother the creatures inside: a woman with a pentagram on her chest and stubs for arms, saying, "Fuck you & yer big ass." On the cover, a man with an erection and a bloody knife ripped a mangled fetus from a dead woman's belly. The policeman then informed him that he was a suspect in the Gainesville student murders. "At first I felt offended," Diana remembers. "I said, 'What about freedom of speech?'" The cop responded like a television detective: "'I don't like your attitude.'" The next day, police grilled Diana about his drawings. He gave a blood sample, at his mother's insistence, to prove his innocence in the killings. But his troubles with Florida law enforcement didn't end there. Diana was eventually convicted on three misdemeanor counts of obscenity for publishing, distributing, and advertising his works Boiled Angel No.7 and Boiled Angel No.ATE. He became the first artist in U.S. history to be convicted on criminal charges of obscenity. He spent four days in jail and three years on probation. "It was definitely a strange time," he says, reflecting upon those days. "I feel that one thing that upsets me, that I think is obscene, is the jail and prison system. A lot of people are put behind bars who don't need to be there." The sawing of babies and penises in his art, he points out, is a critique of actual situations and power structures such as religion — particularly reports of child abuse. Boiled Angel No.6 was, in fact, influenced by the murders in nearby Gainesville. The shock his art elicits allows Diana to communicate the gravity of real-life horrors. Local nomadic arts collective the End/Spring Break and Miami Art Museum have invited Diana to speak in Miami. The speech this Thursday will make a statement about censorship and art. His controversial work will be shown nearby at Bas Fisher Invitational's "Mike Diana: Miami or Bust," alongside the art of those he has influenced, including Mike Taylor, Heather Benjamin, and Mat Brinkman. "When I watched the news, read the newspaper, I couldn't ignore the reports of children being abused, and basically all the different ills of society." Diana says. "I felt like people were desensitized. ... I felt if I did comics that dealt with these issues, [it would] make people think about these things that are happening in their own communities." Back then, he was a teenager who bought Blowfly records on sale. He drove to Orlando to see GG Allin smash a whiskey bottle on his head and bleed through a nude, diarrhea-and-urine-stained performance. At the time, he says, "I was harassed by the police a lot ... curfew things. I had long hair, so I think I fit a certain type of profile that they liked to stop." Moving from upstate New York to the Tampa Bay area at age 9 was jarring for the young artist. The heat was extreme, and his teachers paddled students. His artwork evolved from "just not liking Florida, feeling like I wanted to go against the system, and feeling like I was challenging Florida in a way, with religion, and reports of child abuse." He felt there was a battle going on between old and young here. His reaction to that and his love of horror films and horror comics resulted in art that is both brutal and surprising, yet also somehow beautiful and amusing. But the literal trial he endured here was not funny. He remembers seeing the final jury selection. "I figured I was in trouble." It was, he says, "definitely not a jury of my peers. It was all elderly people." In court, Diana wasn't allowed to show other underground comic books as evidence that his work wasn't an anomaly. They were trying to prove, he says, that the Boiled Angel series wasn't "artwork anymore; it's just something that can turn people into serial killers." Now, though, he says, "I just try to make the best of everything that happened." He's working on a graphic novel about what he calls the "whole Florida ordeal.” "All these years later, I think I'm able to think about it without getting as stressed out as I used to." Today he lives in an exile of sorts in New York, where he moved when his 1994 case went into appeal. The conviction was eventually upheld, but he was granted permission to complete his probation remotely — which, among other things, forbade him from making art for three years. What's prevented him from returning to the Sunshine State, where his parents still live, isn't a hatred for the place, but lingering unpaid legal fees and a subsequent warrant for his arrest. About a year ago, a conversation with Miami artist Kathryn Marks set some wheels in motion, wheels that would eventually send him back to Florida for an exhibition and talk. She'd bought one of Diana's paintings to use as the cover of Miami beatmaker Otto von Schirach's unreleased album, appropriately titled Hermaphrodite Tampon Eater. Once she heard Diana's tale, she knew he had to come to Miami. Asked about Diana's work, Marks says: "On the most basic level, obscenity is rooted in maliciousness. Most important, it must be lacking a sense of humor, rooted in parody with a critical eye. ... What we find obscene today is very different from what it was in the early ’90s. It's pretty interesting that around the time Mike went to trial, Judas Priest was taken to court for subliminal messages in their music and 2 Live Crew was convicted of obscenity." Censorship now isn't as much of an issue as it once was. "Today the cesspools of the internet have had a desensitizing effect," Marks points out. "You can find anything if you look hard enough." As part of MAM's New Work Miami 2013 exhibition, curated by the End/Spring Break, the museum paid Diana's fines in an honorarium so he could return to Florida. "MAM is hosting this talk because of the questions Mike Diana's art and personal story raise about freedom of expression," MAM director Thom Collins says. Diana hasn't let his legal tragedies bog him down. A two-volume box set of his art was recently published by Divus London, a gallery in the United Kingdom, where he's shown in the past. He'll also have a July solo show at Superchief Gallery in New York. Over the years, he's been interviewed by Playboy and defended by Neil Gaiman, illustrated for Wired magazine, and drawn show posters for Marilyn Manson and the Voluptuous Horror of Karen Black. Once a small-town kid photocopying his comics at the local police station, where his mom was a secretary, and selling them to nerds by mail, Diana is an exciting, effective artist with possibly the best story of our time. Also with kind of the worst, weirdest luck.

Fascinating Footnit. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

In 1787, Founding Father James Madison warned: “The means of defense against foreign danger have been always the instruments of tyranny at home.” How true, as we are now finding out as never before.

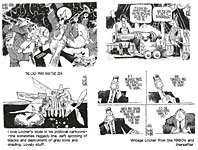

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy SPYING INTO THE LIVES, E-MAILS and telephone calls of Americans has preoccupied the Froth Estate and, consequently, editorial cartoonists for much of June.

In our first visual aid at the upper left, R.J. Matson offers an inventive image of the U.S. capital building as a listening device, but the next metaphor, Mike Luckovich’s deployment of the airport security apparatus, is even more jolting. Oddly, I could find almost no editoons supporting the necessity of spying in order to achieve something akin to national security. Well, spying is the scandal; there’s no satirical fun in calling for security. At the lower left, Luckovich also captures with a uncompromising visual the brute senselessness of the GOP’s pursuit of the Benghazi situation. The New Yorker cartoons have always had so topical a ring to them that many could well run on newspaper editorial pages. With the cartoon at the lower right, we take a look at the magazine’s reaction to the spy scandal with P.C. Vey’s effort. And in the next exhibit, we see Paul Noth’s take on the usual froth and fulmination about Obama the Socialist Dictator, who knocks over all civilized restraints in his tapping of wires and electronic ether. Below that, Dave Sipress offers a moment of truth about crowdfunding. At the upper right is one of the best caricatures of Barack Obama I’ve seen. The eyes are quite right on Eric Allie’s drawing, but over-all, it’s better than many these days. And below that, a recent masterpiece by David Horsey: the cherub’s caution (“Remember what happened when you made ’em different colors”) takes me to a better place.

PERSIFLAGE AND FURBELOWS Walter Mosley interviewed in By the Book at the New York Times: What were your favorite books as a child? I know that as a working writer I should answer this question in such a way as to make me seem intelligent; maybe Twain or Dickens, even Hesse or Conrad. I should say that I read intelligent books far beyond my years. This I believe would give intelligent readers the confidence to go out and lay down hard cash for my newest, and the one after that. But the truth is that the most beloved and the most formative books of my childhood were comic books, specifically Marvel Comics. Fantastic Four and Spider-Man, The Mighty Thor and The Invincible Iron Man; later came Daredevil and many others. These combinations of art and writing presented to me the complexities of character and the pure joy of imagining adventure. They taught me about writing dialect and how a monster can also be a hero. They lauded science and fostered the understanding that the world was more complex than any one mind, or indeed the history of all human minds, could comprehend.

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Pictures Without Too Many Words JUST RAN

ACROSS THIS FABULOUS (hoohah) piece of work when rummaging through an Antique

File. I invented a mock superhero named Zero Hero for the RocketsBlast

ComicCollector when Jim Van Hise was editor. JACK COLE’S

CARTOONS began appearing in Playboy (where he quickly established the

painterly style of color cartoon rendering for the magazine) in the spring of

1954. The cartoon you see in this neighborhood appeared in the May 1957 issue

of Tiger, a Playboy imitator—just a little over a year before

Cole committed suicide.

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv.

From The Week: College sports coaches are the highest-paid state employees in 41 states, receiving checks that surpass the salaries of governors, university presidents, and doctors and lawyers working in state agencies.

GITMO Forever. One of the first to become a captive at the Muslim Prison in Gitmo is Abdul Rahman Shalabi, 37, who has been on hunger strike since 2005. That means that for at least 7 years, he’s eaten nothing except the liquid nourishment that is forced into him through his nose twice a day. Of the 166 detainees at Guantanamo, about 48 are judged so dangerously dedicated to the extremities of the Islamist cause that they cannot be released because as soon as they are, they’ll start setting off bombs in crowded American shopping malls; nor can they be tried because evidence against them was obtained by torture, or because the troops who captured them didn’t collect any evidence or because they supported al Qaeda before the U.S. made that a crime for foreigners overseas. They constitute a predicament that is, as Time asserted, “the legal equivalent of radioactive waste”: they’ll be prisoners forever. Republicons resist Prez Obama’s proposal to move these prisoners to secure prisons in the U.S. (thereby reducing considerably the estimated $38 million per year that it costs to keep them at Gitmo), arguing that the risk of detainees’ committing future acts of terrorism outweighs the damage Gitmo does to the international reputation of the U.S. What? If they’re in prison—maximum security lock-ups—how can they commit terrorist acts? Are any of these Republicons capable of thinking?

BOOK MARQUEE Previews and Proclamations of Coming Attractions & Short Reviews This department works like a visit to the bookstore. When you browse in a bookstore, you don’t critique books. You don’t even read books: you pick up one, riffle its pages, and stop here and there to look at whatever has momentarily attracted your eye. You may read the first page or glance through the table of contents. All of that is what we do here, starting with—: Forbidden Worlds, Vol. 2: Nos. 5-8 Edited by Philip R. Simon with Foreword by Dan Nadel 190 6.5x10-inch pages, color; Dark Horse Archives hardcover, $49.99 ANOTHER IN THE DARK HORSE series exhuming historic comic book titles from the last spasm of the Golden Age, in this case, 1952 issues of the American Comics Group’s Forbidden Worlds: Exploring the Supernatural. As Nadel notes in his appreciative introduction, “Against the baroque grotesqueries of William Gaines’ EC Comics or the gutbucket horror of Harvey’s Bob Powell/Howard Nostrand stories, ACG was relatively, well, straight.” I think by “straight,” he means a little less sensationally horrifying. Good stories but not pacesetting in gruesome detail. EC has always rightfully worn the laurels for the finest artwork in comics of the period, and in the shadow of that achievement, we forget that other publishers often printed comics in which the drawing was not too shabby, ACG among the foremost. So we’re happy to have this archival project from Dark Horse to remind us of past glories that were only a little shy of glorious. Most of the artists represented in this volume are not well-remembered these days—Lou Cameron, Lin Streeter, Al Camy, George Wilhelms, Pete Riss, Sam Cooper, Paul Gattuso, Sam Cooper, Harry Lazarus, King Ward—but a few ring a bell in the memory—Paul Gustavson, Ken Bald (nice clean covers), and Al Williamson (inked by Roy Krenkel and Larry Woromay). And the reproduction of their drawings herein is mostly decent. Cameron’s bold and crisply rendered pictures, for instance, are sharp and clear (evoking the style of Johnny Craig a little). Williamson, however, does not survive happily. Through much of his early career in comics, Williamson was apprehensive about inking his own pencils: his pencils were superb, and he was afraid of ruining them in the inking. So he usually recruited artist friends to finish his work. But his inkers on the two Williamson stories here do not reproduce well: too many delicate fineline embroideries, and the fillagree gets mashed up and blotchy. Virtually all the rest of the work in this tome survives very well.

Black Cherry: A Lurid Tale of Sex, Violence, and the Supernatural By Doug TenNapel Approximately 160 6.5x10-inch pages, b/w; Image paperback, $17.99 Ratfist By Doug TenNapel 176 6.5x10-inch pages, color; Image paperback, $19.99 JUDGING FROM

THE BACKCOVER BLURB and the subtitle, Black Cherry is a fairly

straight-forward story of Eddie Paretti, “a down-on-his-luck Mafioso who is so

desperate for cash that he’s agreed to steal a dead body from his own mob boss.

Things only get worse when he discovers the body isn’t human.” The body is that

of an extra-terrestrial being, who turns up, at the end, in the most unexpected

place. There’s also a love story: Black Cherry is an exotic dancer and drug

addict with whom Eddie is in love. She slips in and out of the story, which, at

the end, turns out quite unexpectedly. Along the way, Eddie, like all TenNapel

protagonists, is in constant vigorous motion, running, swinging fists,

brandishing firearms—the usual array. Ratfist, on the other hand, is about a would-be costumed superhero, who, in civilian guise, is Ricky. In its inaugural form, the book appeared a page at a time on TenNapel’s website as he experimented with web comics. TenNapel was careful to give every page some “take-away” quality that a viewer would enjoy. Generally speaking, that results in every page ending on a suspenseful or comedic note, which gives the whole production, now assembled into a single volume, a sort of breathless excitement, an aspect that is wonderfully suited to the headlong dash that is the chief and commendably exciting aesthetic of TenNapel’s works. In

the opening sequence, Ricky resolves to propose to his girlfriend Gina, but during

the dinner at which he plans to spring this surprise, Ricky suddenly grows a

rat’s tail and his face blossoms out with rat’s hair. Ricky dons a mask in

order to hide the hair. From there on, meaning and narrative coherence

deteriorate rapidly into a frenzied rollicking romp of explosive action and

daunting plot twists and looney layouts. And strange beings. Ricky cuts his

tail off, but it acquires a life of its own and wraps itself around him like a

bandolier; henceforth, Ricky (Ratfist) deploys the tail like a whip whenever

he’s not engaging in conversation with it. Or with a rat that rides on his

shoulder most of the time. The story is a manic delight, leap-frogging from one madcap episode to the next without quite resolving the first. There’s a monkey and a cat-faced former boss at the Simian Icthus Institute where Ricky and his lab cohorts are searching for a cure for cancer. Gina, it seems, marries Rick in some other life and they have a child, but she gets cancer. At the end, she seems cured, Ricky’s face loses its rat-hair, and he gives millions of dollars that he’s inherited to cancer research. On the last page of the book, TenNapel supplies what might be a coda for the work, quoting from Ecclesiastes 3:19: “Everything is meaningless.” Or not. TenNapel, who is a conservative Christian, gets God into his stories of late, but not obtrusively—and definitely not evangelically. He’s got some heat lately from more liberal-minded souls, who find his opposition to same-sex marriage reprehensible. I support same-sex marriage (and think civil unions are no substitute for the real thing—nor do they seem to come with all the attendant legal benefits that regular marriage has; they are, therefore, a cheap, petty compromise not worthy of the name), but TenNapel doesn’t seem to be doing anything more than exercising his right to freedom of expression, and that’s okay by me, even if I disagree with his religious views. His expression, on the other hand—his wildly energetic cartooning—captivates me every time.

WOODWORKS

Against the Grain: Mad Artist Wallace Wood Edited by Bhob Stewart 238 8.5x11-inch pages, b/w with 14-page color section; 2003 TwoMorrows Limited Edition, hardcover, $59.95 Wally’s World: The Brilliant Life and Tragic Death of Wally Wood, the World Second-Best Comic Book Artist by Steve Starger and J. David Spurlock 224 7x10-inch pages, b/w with a color section; 2006 Vangard hardcover, $34.95 WoodWork: Wallace Wood, 1927-1981 342 9.5x12-inch pages, color throughout; 2012 IDW hardcover, $59.99 WALLY WOOD, OR “WOODY” as his friends called him (he never liked “Wally”), undoubtedly deserves three books. Even more. If you need some sort of justification, then you don’t know Wood’s work. Here, from Bill Mason in Against the Grain, is a hint about what you’ve missed: “After spending most of 1951 [the first year of his work for EC Comics] restlessly changing his style, alternately refining and coarsening the self-assured, effortless-looking manner of his early New Trend stories, Wallace Wood suddenly, in the May-June 1952 issues of EC science-fiction and war titles, brought eye, heart and mind into perfect synch and emerged as one of the great masters of comics illustration. [His stories of that period] are more than the first fruits of Wood’s hard-won technical mastery: they are graphic expressions of everything Wood knew and felt about life and art, and harbingers of a period of artistic growth and achievement that lasted almost [all of the next] three years.” I first encountered serious efforts at Wood biography in Nos.7-13 of Outre magazine (1997-98), in which David J. Hogan did his best with the text, and the publisher, printing on porous newsprint, did the worst he could do with tiny bits of Wood art. All of these books are better than that—heroic as it was back then; but the books at hand are not equals. The

text in Against the Grain consists of essays by many of those who knew

Wood, including Stewart and others who worked with Wood in his studio. Some

“essays” are transcripts of recorded interviews—with John Severin, for

instance, and Al Williamson. In the opening chapters, Stewart provides a

biographical overview, including lots of pre-pro Wood art. Wood’s try-out page to do Prince Valiant is here, but his notorious “Disneyland Memorial Orgy” done for Paul Krassner’s Realist (printed as the center spread in the issue for May 1967) is missing—although, perversely, Krassner, one of the essayists, described how the infamous art came about (“the most pirated drawing in history,” Wood called it). Stewart and his cohorts were doubtless trying to be discrete. They apparently did not want to besmirch Wood’s towering reputation by printing any of the brasher undertakings of his later years—no Sally Forth (one of the more voluptuous of Wood’s ever sensuous wimmin in a refreshing comedy of sf and perpetually naive disrobing), only a few panels from Cannon, Pipsqueak Papers, and The World of the Wizard King; nothing at all from Wood’s contributions to porn magazines. That

Wood was himself much less restrained in depicting the erogenous dimensions of

female characters—and doubtless enjoyed doing so—is evident in the drawings he

made while a teenager. As a teenager myself once, I shared his enthusiasm, and

took lessons in the limning of the curvaceous gender from his rendering of such Mad wimmin as the Draggin’ Lady in “Teddy and the Pirates” (Mad No.6, August

1953). Wood’s sharply angular way of drawing women’s knees when shapely legs

were bent was particularly instructive. Years later, I sent in “dues” to join one of the clubs Wood had conjured up as a fund-raising scheme; you joined, and he sent you an original drawing, and with my drawing, he sent a note, asking me what I thought of pornographic cartoons. I replied that there was no such thing as a pornographic cartoon: cartoons are either funny or they’re not. And if they’re not, then they’re not cartoons. Despite the book’s shortcomings, it is copiously illustrated and the essays provide critical analyses of Wood’s work, biographical detail, and insight into his complex personality.

Wally’s World worthy for its text rather than its pictures. The text seems a somewhat novelized recitation of the facts of Wood’s life and career—early partnerships with Harry Harrison and Joe Orlando, work for Avon, Fox, Trojan; then EC Comics, Will Eisner’s Spirit, then, after the Wertham collapse, Marvel, Tower, Charlton, Warren, Topps, followed by risque strips for Cavalcade and other magazines, then Wood’s Witzend. But the authors quote Wood’s friends and associates as factual underpinning, making the work reasonably trustworthy despite its occasional flights of narrative imagination (especially in regaling us with the stories of Wood’s youth). The art, alas, is reproduced in snippets and minuscule fragments. A 32-page color section reproduces covers mostly. Nothing much about his Overseas Weekly work (Sally Forth, Cannon); the Disney Orgy is here, but no other erotica worthy of the name. The book’s opening chapter is a detailed description of the death scene at Unit 71 of the apartment building at 15150 Parthenia Street in Van Nuys, California, where Wood was living when he committed suicide rather than (it is supposed) endure endless dialysis treatments for a failed kidney. Grim way to begin a book, but Wood’s finish is somehow an appropriately poetic end to a brilliant career that went into decline with his health.