|

||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 278 (June 14, 2011). Hare today, we

concentrate exclusively on the Reubens Weekend, May 27-29, during which the

National Cartoonists Society bestows numerous awards, including the Reuben for

“cartoonist of the year.” Our report includes

Special Rapid Rabbit Report WHO GOT THE REUBEN And Other Matters of Slight Import at the 65th Annual NCS Conclave, May 27-29

“You may not believe this,” said Randall Monroe, “but I occasionally have to re-draw my stick figures.” “That will be the line by which this Reuben Weekend is remembered,” grinned editorial cartoonist Mike Lester. And he repeated it to me as we milled around after Monroe’s presentation: “You may not believe this, but I occasionally have to re-draw my stick figures.” Although the awards distributed at the Saturday evening banquet constitute the irrefutable high point of the National Cartoonists Society’s annual convention, the preliminaries were usually instructive and often thought-provoking. These one-hour program events are called “seminars” even though they are all formal presentations by individual cartoonists, who rehearse their professional biographies and discuss their work, projecting pictures on a large screen in front of a respectful audience. Monroe was one of three Friday afternoon panelists who talked about their web comics: Monroe, xked, and Kate Beaton, Hark! A Vagrant, were led, more-or-less, through their paces by Dave Kellett, whose Sheldon began as a newspaper comic strip but graduated (or regressed) out of print into the digital ether. Kellett makes his pictures with a bold undulating line; Beaton, with appealing whip-lash brushwork. But Monroe, as he admitted, draws stick figures. Lifeless wooden stick figures. And sometimes he re-draws them, no doubt aiming for some nuance of perfection imperceptible to others. And stick figures, or near approximations thereof, might be seen as dominating this year’s presentations. Jeff Kinney and his Wimpy Kid appeared on Saturday afternoon, followed by R.O. Blechman; and Roy Doty kicked off the Friday presentations. Neither Blechman nor Doty stoop so far as to draw stick figures, but both achieve symphonic complexity in their depiction of the human condition by deploying lines of ethereal simplicity—Blechman’s, ghostly and tentative like the overwrought human spirit he often examines; Doty’s, pure and clean and quietly assertive, often in the service of an advertising client. The final presentation on Friday afternoon was Bill Griffith’s: he traced the history of his supremely odd albeit oddly engaging syndicated comic strip, Zippy, now celebrating a 40th anniversary since the title character’s debut in a 1971 underground comic book. Griffith was the exception that proved the rule: his drawings, often shaded with cross-hatching or copious slanty lines—and sometimes including vast panoramas of urban landscape—were refreshing in their unabashed and successful representational ambitions. He did a year-or-so’s strips not long ago in which picturesque roadside diners were featured, some in the shape of sombreros, others like derby hats or giant hot dogs, and on and on—a surprising and plentiful variety. (Next month in Harv’s Hindsight, we’ll be posting an article based upon my 1993 interview with Griffith; stay ’tooned.) But Griffith is an unrepentant throw-back to the glory days of newspaper comics when good or at least decent drawing ability was on display. An observer of the afternoon programs at this year’s NCS confabulation could be forgiven if he (or she) thought the Society was championing stick figures.

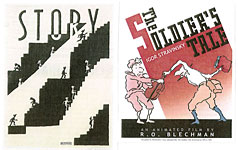

THE FIRST EVIDENCE OF THIS EMERGENT thistle among the jonquils in the garden of cartooning splendors may be the presence at the podium on Saturday afternoon of Jeff Kinney, who has parlayed childish stick-figure-like rendering into five best-selling books (the sixth, at which he is presently at work, will find his protagonist, the 12-year-old Greg Heffley, and his family snowed in and suffering from cabin fever), a series that has sold over 42 million copies world-wide, and two movies based upon the books. Not bad for stick figures, which may account for the long line of cartoonist admirers that formed after his presentation at a table where he was autographing copies of his oeuvre. “I feel like a fraud,” he said at one point, “—I couldn’t get in this organization!” Kinney is a tall, tousle-haired fellow with a Roman nose and a benign, toothy smile, beaming diffidently and almost constantly. The first impression of him as he began his talk was that he was a thoroughly nice guy, maybe even a little naive; that impression endured, but it was augmented by the self-deprecating remarks that accompanied his almost satirical description of his miraculous career, which, he alleged, had taken eight years to germinate. As one of the opening gambits in his presentation, Kinney told of meeting a kid in a bookstore or a school somewhere. The kid asked his name. “Kinney,” said Kinney. “What’s your first name?” the kid persisted. “Jeff,” said Kinney. The kid was amazed: “You have the same name as the guy who wrote those books.” While in college at the University of Maryland, Kinney drew a comic strip, Igdoof, for the campus newspaper, The Diamondback (where two other stellar cartoonists had honed the barbs of their craft—Frank Cho and Aaron McGruder). He graduated with a degree in criminal justice, but his Igdoof experience had convinced him that he wanted to be a cartoonist, so he applied for work in various outlets and submitted strips to syndicates, all of which turned him down (some citing the stillborn quality of his artwork). His dream deferred, Kinney went into computers, becoming a software engineer and creating online games and the kid-friendly website Poptropica. While sweating over a hot keyboard, Kinney decided to keep his cartooning hand active. Casting about for a subject, he did what many creative personalities urge upon aspirants: he turned to what he knew best, his own life. He explains on his website: “I wanted to write a story about all of the funny parts of growing up, and none of the serious parts. I had a pretty ordinary childhood, but lots of humorous stuff happened along the way. So I decided to write a book about what it’s really like to be a kid, or at least what it was like for me. My goal was to write a book that made people laugh. There were certain books I read as kid that really stood the test of time. I wanted to write that kind of book!” To write and draw that kind of book, that is. And the kind of book that would combine both writing and drawing, it seemed to Kinney, was an illustrated diary. He set the story in middle school because, he explained, “that’s when I maxed out talentwise” in drawing skills. His initial notion was to create a nostalgic look back to school years for adult readers. He worked on it quietly in private: “I felt this was the only good idea I was ever going to have, so I wanted to take my time.” He took years. In 2004, he prevailed upon his employer at the kids’ website FunBrain to post pages of the diary online as a sort of comic strip. Suddenly, Diary of a Wimpy Kid had a following—as many as 90,000 visitors a day. By 2006, Kinney had 1,300 pages of the diary, and he took them to the ComiCon in New York, where he met Charles Kochman, an editorial director at Abrams. A month later, Kochman phoned Kinney, saying he wanted to publish the Diary but aim it at young readers rather than adults. By the time the first book was published, Kinney had been working on the Diary for eight years. Kochman’s decision produced a bestselling sensation, but the blessing was in some respects mixed. Greg is a proud self-absorbed slacker, who thinks his parents are corny, rationalizes his worst habits, and feels put-upon by his older brother, Rodrick. Not an admirable role model, say the Diary’s detractors. “The running theme of the series is that Greg is a little kid who gets picked on, so anything he does to others is understandable under the victimhood license,” said one critic online. “But,” wrote David Browne in Parade (March 20, 2011), “little boys, and the people who want them to read more, can’t get enough Greg.” Barnes & Noble recently listed the Wimpy Kid series as more popular among 9-12 year-olds than Harry Potter books, no small matter. As the series creator, Kinney told Browne he likes “creating a feeling of dissonance with my readers. You’re expecting an adult to step in and make things right. To me, the humor comes from that—the reader being left with a sense of ‘Isn’t Greg going to learn his lesson?’ There are plenty of books where you can feel the author guiding you toward a particular conclusion. I don’t do that. I like to write for entertainment.” Still, he sometimes frets about his possible influence over impressionable young readers: “I know Greg’s not a role model,” he said, “and it’s a bit of a conflict for me. There’s a fine line between him being a lovable jerk and him being just a jerk.” But Kinney’s ambivalence is offset by the response he gets from parents who say the series has affected their children in positive ways few books have. Said Kinney: “Even if the books put just a few kids on a path toward reading, then my conflicted feelings dry up.” Kinney draws on a wacom tablet because the mechanics smooth out his lines. He dislikes ragged or rough-edged lines, admiring the thin, uniform lines in Beetle Bailey. After he’s produced a succession of pages, he strings them together for the continuity. The successful book author still commutes once a week to his job in Boston, where he continues working on games for Poptropica. He’d like to get Wimpy Kid animated, he told Browne; he’d also like to write a non-Greg sitcom and feature film. “I don’t want Wimpy Kid to be my one thing,” he said. After Kinney’s talk, I was standing next to editoonist Bob Rich, and expressed mild amazement at the length of the line of autograph-seeking cartoonists that had formed to get Kinney’s signature on one or more of the Wimpy books. I commented on the inexplicable success of wimpy drawings by quoting Lester’s opinion that Monroe’s confession will describe the weekend, and Rich responded by saying (with the perception of sheer insight): “It’s like saying, ‘I have this brilliant idea for a book, but I can’t write.’” MAYBE NCS is merely—at last—confronting the present and anticipating the future, something it has been reluctant to do. The “graphic novel” found its way into the lists of cartooning endeavors deserving awards only last year; for several of the preceding years, the winners in the comic book division were actually graphic novels—as if NCS officialdom couldn’t tell the difference. That myopia was corrected, finally, last year. (I have a history of carping about NCS’s awards “system,” and I won’t repeat the litany of sins here; interested parties, however, can find it all at Ops. 242 and 263.) I don’t mean by applauding the present to slight cartooning’s glorious past. And neither does NCS. Two of the presenters this year were also formally recognized for the achievements of their life’s work: at the Reuben Banquet, Blechman received the Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award, and Doty was given the Gold Key Award, ushering him into the NCS Hall of Fame. Blechman, animator, illustrator, graphic novelist and cartoonist, is noted for his fey scraggly-line covers for The New Yorker (19 of them), his children’s proto-graphic novel (The Juggler of Our Lady), animated tv commercials for Alka-Seltzer, and the PBS Great Performances broadcast of “The Soldier’s Tale,” a humorous albeit bleak visualization of Igor Stravinksky’s and playwright C.F. Ramuz’s theater piece. Reversing the initials of his given names, Oscar Robert, to create his “professional name,” Blechman began his career after service in World War II when he was invited by animator John Hubley to join Storyboard, Inc., an advertising studio where Blechman learned animation, storyboarding for Gene Deitch. Nothing of his was ever animated in his style at Storyboard. “I was a story man, who would visualize these things. And I don’t think all that well. I didn’t know what the hell film was all about. It really took me a long time to learn that I had to make films.” Blechman is slight of build, somewhat restrained in manner, and meandering of speech: his discourse is enlivened by the ebb and flow of asides, tangential topics taken up as he is reminded of them and then abandoned. Given his mild-mannered professorial demeanor, the occasional “hell” or “damn” with which he sprinkles his talk is wholly unexpected but always welcome as an affirmation of his common humanity and cartoonist collegiality. “When I was in college,” he said during an interview with Jeet Heer at the Comics Journal website, tcj.com/r-o-blechman-interview/ dated May 26, 2011, “I think in 1947, I thought to myself ‘the future art form is animation.’ How I came across that, I have no idea and I was wrong. It hasn’t been true yet. Although I have to say that I ought to be seeing ‘Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs.’ Except that I’m not very sympathetic to 3D animation. I like the 2D kind, but so be it. No, I don’t think that it has yet reached its prime. I think it will eventually happen, so many of the graphic novels that we are enjoying will one day be, I hope, turned into animated films. I hope by the right film makers.” Seeing animation as the ultimate art form, Blechman has tried to persuade others, Seth and Art Spiegelman for instance, to convert their graphic novels to film. “They seem not to be interested,” he allowed. “And I can understand it because their work is so self-contained and perfect as a written form, and they always think ‘Hey, it’s going to be ruined,’ but I think if they work with the right people, it can be enhanced.” Although his passion is for animation, he admits to “proud achievements in illustration ... some of my New Yorker covers were really very good and then, the ten years I did every single cover for a magazine called Story. I loved doing that stuff. It was fantastic. But I have not begun to fulfill my ideas about animation.” He showed several of his Story covers during his presentation; a couple of them are incorporated into the Comics Journal interview. (To see some of his recent work, including animation, visit huffingtonpost.com/ro-blechman.) He also showed an abridged version of “The Soldier’s Tale”—“the most gratifying of all the things I was able to do.” Fragments of a 2006 interview supply an introduction to the retrospective volume from Drawn and Quarterly, Talking Lines, wherein Blechman confesses: “As a kid, I had no interest in being an artist whatsoever. I wasn’t even a cartoonist except in high school, and that was just to show off. It didn’t occur to me until very recently that the only reason I went to the High School of Music and Art was that I was in love with my next-door neighbor, a beautiful blonde French girl who was an artist. I loved her. She painted her walls and had murals everywhere. She’d painted a donkey’s behind on the wall and the [light] switch was where his ass was, and she would ask me to ‘Turn on the lights, please.’ This, to me, was what art was all about.” Asked by Heer about the development of his distinctive minimalistic frazzled-looking drawing style, Blechman was at a loss. “I think it’s a mystery” he said. “I don’t know if any artist can say how [his style evolved]. It was a gradual, very slow, laborious process. ... A lot of it is arbitrary and artificial because you say, ‘Hey, I feel comfortable with this. I like it. I’m going to explore this.’” Heer speculates that Blechman’s Francophelia influenced his work—Jean-Michel Folon, for instance—and Blechman admitted he loved Folon’s work. I’m quoting Blechman from sources other than his NCS presentation because I’m half-deaf and couldn’t hear much of what he actually said. But I heard well enough to catch the tenor of his talk, a manner reflected in everything he’s said in printed sources, so I’ve quoted them for the sake of the flavor they impart of the artist. To Heer, Blechman remarked that he valued freedom to be playful. “I think the state of play is essential for the production of any good art,” he said. “So I have fun. I always push to the limit, which is very funny because I’m a very conventional guy.” His sense of play is doubtless what makes him a cartoonist. Heer’s interview finishes with a playful Blechman: “I watched a very interesting film two days ago. It was a documentary on the acidification of the ocean and one chemist took sparking water and put a tooth in it, and after a few days, [he] showed the tooth. And it was all broken up in the carbonated water. And so the point is that there’s a lot of bad shit in carbonated water. How about that?”

ROY DOTY’S SLOGAN seems to be his oft-uttered “I’ve been working all my life but never had a job” (or words to that effect), by which he alludes to a lifetime of freelancing. He earns a living but has never earned it by salary. The long slog began while he was in the army during World War II. The army spent months training him for various assignments in the Signal Corps, and then, as he told Frank Pauer in the March-April issue of NCS’s Cartoonist newsletter, he was re-assigned. While he was waiting for radar to be built, he did a comic strip, Corporal Qwerty, for the base newspaper at Robbins Field, Georgia. His effort evidently attracted the attention of Higher-Ups, who promptly transferred him into a more convivial billet: he was spirited away from Georgia to New York, then to England, then to Paris, where he found himself in the office of Stars and Stripes, Yank, Oversea’s Woman and Army Talks. “My rank,” Doty noted, “had been changed from radar expert to army cartoonist.” Doty drew for Stars and Stripes “when they wanted something odd and decorative and funny. I did Overseas Woman [because] I was the only one who could draw women who had little feet and little noses, instead of [bigfoot women].” He was in Paris long enough, he said, “to see the British and French cartoonists, whose work I had never seen. With their thin line, that was my milieu right from the start. That’s the way I’m going to go, I thought. I threw away my brushes and found Gillott pens.” On the staffs of various publications in those parts, he met Anatole Kovarsky and Per Ruse, “who changed his name to Pete Hansen and did the strip Lolly for many years.” For the London Daily Mail, Doty drew a weekly cartoon called A Yank in Paris and met a woman editor who knew a woman who was starting a new magazine in Paris and introduced him. “I did all the illustrations for the first issue of Elle,” he told Pauer with a chuckle. Once exposed to European cartoonists, “who were doing totally different things than I’d ever seen,” Doty found his metier doing humorous illustration. “Didn’t do a comic strip or gag cartoons. There was something [that absorbed his interest] about a page full of what I do now. Purfle—that lovely, decorative inlaid border on a guitar. Purfle. I do decorations, humorous purfle. ... Clean, simple line without a caption. Ever. Without a word balloon. Ever.” (Well, not quite: word balloons often invaded his Laugh-In comic strip of the late 1960s, as you’ll soon see.) During his presentation on Friday afternoon, Doty, avuncular and rumpled and sometimes ironically albeit smilingly caustic, engaged us all in the purfle of a 65-year career, samples of which I’ve posted hereabouts.

After he escaped the army, he found his way to New York—“all the publishing was there.” At first, no one understood his approach—only Europeans. But just as his money was about to run out, he got an assignment—three drawings for the New York Times Magazine. And he’s never looked back. “It never stopped. I got busier. The fifties were a great time to be in New York. In the fifties, I was working for everyone, plus turning out books galore ... and for three years dong one of the early kids tv shows daily on Dumont, making 40 half-hour movies at the same time.” Living in Stamford, Connecticut, Doty took the 9 a.m. train into the city every day, “ran like a frightened deer all over New York, picking up, delivering.” Then he returned home and worked on new assignments until midnight or 2 a.m.; then back to New York the next morning. “I never shared a studio with anyone, never have,” he said. “Always worked at home. Still do. It’s a great place to work but it costs you a lot of wives.” (He’s been married at least three times by my hit-or-miss calculation.) NCS was formed the year he commenced his career, but despite being put up for membership by Alex Raymond and Ernie Bushmiller, he wasn’t accepted at first. The NCS multitudes saw him as an illustrator. So Doty applied to the Society of Illustrators, who turned him down because they saw him as a cartoonist. “So I said a pox on both your houses,” Doty said. But in the mid-1960s, ironically, he was asked to make a presentation at an NCS meeting and was forthwith inducted into membership by acclamation. He has since won the NCS Advertising and Illustration division awards nine times, and the Greeting Card award once. (A grand array of Doty’s Christmas cards, which he has produced faithfully every year since 1946, is on display at cagle.com/hogan/features/christmas_cards_2008/main.asp , thanks to Hogan’s Alley.) Doty’s client list reads “like a Who’s Who in the World of American business,” his website says—Buick, Black and Decker, Ford, Macy’s, Minute Maid, Mobile Oil, Texas Instruments, Kodak, Ovaltine, Coca-Cola, and Perrier are among his past clients. His pictures have adorned packages and book covers, print advertising in glossy periodicals, and in campaigns by non-profits and on tv. His how-to home improvement series, Wordless Workshop, was syndicated for 50 years and runs, still, in The Family Handyman magazine. And for three-and-a-half years (1968-71), Doty produced the syndicated comic strip, Laugh-In, based on “Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In” tv program. “I did the first three months of gags,” he said, “and then the well ran so dry even I couldn’t believe it. I started sending out the word: ‘You gag writers, wherever you are, have I got a market for you: I pay in cash, on acceptance.’ It wasn’t much, but back then money went a lot further, and, boy, did they come pouring in.” By contract, the strip quit when the tv show ended. And Doty went back to spinning through the rest of his repertoire. “I think design and composition are what makes my stuff work,” he told Pauer. “I mean, it’s not the raison d’etre or the main thing you remember, but there’s that detail. Which I don’t have to do, but it’s the little things that make it fun. I love the decorativeness of it. I just got hooked there in Paris where I got to meet a lot of artists. Not only did they turn out funny stuff—and I watched them labor overnight just getting the idea across—but they made it attractive at the same time.” Has he thought about retirement? “About what? You have to have a job first,” he quipped; then got serious: “I would go crazy. Not on your life. Sit on some porch deck somewhere watching the waves roll in and out? And in and out. And in and out. And in. I don’t broadcast my age, but I also don’t give a damn anymore. It doesn’t show in the work, I don’t think. Without a pencil in your hand, life can be dull for us [cartoonists]. The work can be a slave-driver. But a nice one.”

DOTY WAS SPEAKING AGAIN the next morning, Saturday, at the annual business meeting, which, for years, he has enlivened with some cranky criticism of the organization. Since almost nothing else happens at the business meeting—oh, well, this year, The Family Circus’s Jeff Keane was succeeded as president by Mad’s Tom Richmond, a body-building cartooner who is renowned not only for the superiority of his caricatures but for the massive circumference of his biceps—the event could well be called the Roy Doty Hour. This year, he arose to the usual accompaniment of hoots of joyful derision, whereupon he wondered why the winners of NCS awards don’t get more publicity, particularly in their home town newspapers. Doty’s wonderment was compounded by the publicity that John Read’s traveling exhibit of Sunday comic strips, “One Fine Sunday in the Funny Pages,” was currently receiving in the Boston papers. Read’s show, which features original art from 130-40 cartoonists, all their Sunday strips for the same Sunday, April 11, 2010, ran for the month of May in Boston, with a gala reception closing the event on Sunday, May 31, the last day of the NCS meeting. It was an event on the Reubens Weekend program, so we attended in vast quantities, turning the exhibit venue into a crowded room that Sunday. The reception was announced in the paper; and the event was covered by the Boston Globe and described in the issue of the paper the day after. It was accompanied by photographs depicting and text naming some of the stellar personages in professional cartooning. But no mention of NCS or the Reubens winners of the previous night’s banquet. Not that the publicity was an unalloyed blessing. One of the photographs was of a 17-year-old girl who made the rounds at the reception and asked every cartoonist she could find to "sign her arm.” So—Read proved that it is possible to generate publicity for cartoonists; and the coverage also proved that publicity will bring out autograph-seeking fans who can be annoying. After a few murmurs in support of Doty’s wonderment, past prez Lynn Johnston rose to supply a little historical background that might explain why NCS doesn’t get much publicity. Several years ago, she reminded us, NCS leadership decided that the Reubens Weekend would be a strictly “private party”—that is, not open to the public or the press. This maneuver was aimed at eliminating those pesky arm-autograph-seeking fans who, at previous Reubens Weekends, had pestered members for their signatures, thereby diminishing the members’ ability to relax and have fun. So how, I asked myself, is a newspaper editor going to react to NCS press releases that announce the Reubens Weekend but conclude by saying, “Oh—by the way, you’re not welcome”? Into the nearest round file, of course. Doty’s concerns unhorsed by this dose of history, the meeting promptly deteriorated into adjournment, but not before we had all enjoyed the entertainment he always, without fail, prompts at the business meeting—convivial catcalls from the attending multitudes, bad jokes, and the other encumbrances of fame and affection from a mob of satirically inclined wags and scallywags. And before we go further into the wilds of the weekend, here is our Reubens Gallery for 2011.

THE WEEKEND’S RITUAL PRELIMINARIES customarily conclude with a cocktail hour before the final festive throes of the Reuben Banquet at which the awards are dispensed. But the hour of liquid refreshment is postponed for a 90-minute interval without programming so that those in attendance may perfect their attire for the evening: by tradition and decree, the Banquet is a “black-tie” affair, and tuxes and formal gowns abound. The original intention of the formal dress fiat, proclaimed in the mid-1950s, was to infuse dignity into the occasion—to demonstrate, for any who might be interested, that cartoonists were not slovenly unshaven attic-dwellers but normal human beings. In short, the Banquet as it evolved was viewed as a showcase for the profession: cartoonists were on display. This justification for impersonating penguins disappeared several years ago: since neither the public nor the press is welcome at the Banquet, the display of cartooner dignity no longer serves any purpose. The only people to witness cartoonists in tuxedoed dignity are other cartoonists, who, as a breed, recognize fraud when they see it. This year’s Reuben Banquet transpired in the venerable Copley Plaza hotel, located, since its gala opening in 1912, in the Back Bay on one edge of Copley Square, which is bounded on two of its other sides by the historic Boston Public Library with its vaulted entryway and John Sargent murals, and on another by the grandeur of Trinity Church, a gothic pile of vaguely Romanesque persuasion. A luxurious symbol of Boston's rich history and elegance, the Copley Plaza offers public spaces—lobby and meeting rooms, not to mention the dark-wood splendors of the regal Oak Room Bar—that are festooned with lavish architectural details under majestically soaring ceilings. The hotel is the perfect place for ostentatious dinners, and on the Reuben Weekend, it hosted several high school proms with aspirations to grandeur.. Attendees at the proms were, like the cartoonists, in tuxes and formal gowns, the latter of the strapless bare-shouldered sort that have survived successive waves of female fashion without changing, despite the otherwise obvious fact that we have moved into the age of cleavage and left the clavicle forever behind. So to speak. On a couple of unreported occasions, a cartoonist wandered into a prom domain, thinking the tuxedos signaled others of his kind. But such errant inkslingers quickly discovered their mistake: there were no bars at the proms. And cartoonists, as a breed, are generally more interested in bars than bare shoulders, so the teenagers were as safe and unmolested as mountaintop recluses. Bars figure prominently in the Reuben Weekend agenda. Every day, Friday through the concluding Sunday, ends with a cocktail hour with open bars offering beer and wine. One can purchase more spirited refreshments, but at exorbitant Big City Prices—$10, maybe $15, a drink. (I’m not sure of the prices: once the cost of a martini exceeds $8, the prices all look excessive beyond measure, so they may as well be $15-$25 an ounce for all I care.) The Friday and Sunday cocktail hours also feature an expansive array of hors d’oeuvres, enough for a meal. Late on Friday night, cartoonists who have lost all sense of their proper roles in civilized society participate in a raucous karaoke, which I usually avoid in order to preserve what is left of my ear drums. As the Saturday evening cocktail hour wanes, the crowd eddies into the Grand Ballroom for the awards dinner. About 400 of us, but only 176 are NCS member cartoonists; the rest are spouses, children or the minions of syndicates, who sponsor many of the cocktail hours. Seating is assigned. We can choose our tablemates in advance, but I never do (because the people I’d most like to sit with are usually surrounded by other, more important, admirers). If you don’t arrange for dining companions, the factotums of the Society assign you a table, willy nilly. This year, I was lucky: I couldn’t have chosen better. At my table were seated a couple of the profession’s distinguished elder statesmen, Jerry Robinson and his wife Gro, and Roy Doty. On my left, I was delighted to find Ed Black, a friend and fellow history enthusiast, who occasionally contributes to these pixilated pages (last time, for instance—and I forgot to credit him for the story about the stolen Superman plaque; thanks, Ed). After

dinner, the show began. And a show it was. Dancing girls waving flags

emblazoned with pictures of the characters of the nominees for the Reuben, a

band playing can-can music, and, master-minding (so to speak) and presiding

over the festivities, Tom Gammill. Gammill’s day job is as a writer for

such tv shows as “The Simpsons” and “Seinfeld.” But he also writes and

(allegedly) draws a comic strip that no newspaper will publish. Not that the

comic strip, which he calls “The Doozies,” is risque or politically

inflammatory or otherwise at all edgy. It isn’t. What it is is a badly drawn

parody of a comic strip, starring a kettle of humanoid beans infected with

terrible jokes. Gammill’s sense of humor is so lame it limps on both legs, as

you can tell from the samples posted nearby. The only other place you can find

this awful specimen of animated legumes is at GoComics; go there and search for

“The Doozies.” You’ll live to regret it, but you’ll be a better informed person

than you are now.Remember: education is not sweet, but it’s nourishing. The conferring of awards and the ensuing parade of winners across the stage was punctuated by Gammill comedy. Bits of so-called funny business in which he often enlisted the aid of the award presenters. And videos. The first of these was “Godfather, Part II,” in which NCS prez Jeff Keane played the Marlon Brando role, his cheeks stuffed with wads of cotton. Of the three other videos, two featured Gammill, playing his usual role—that of a well-meaning but clueless and inept would-be cartoonist. If, for some reason akin to the morbid curiosity that prompts us to slow down at auto accident sites in the expectation of seeing blood or gore, you want to witness some of Gammill’s putative humor in videoddities, you should prolong your visit to his GoComics niche, where you can watch a video “visit” to his “studio” or see one of several YouTube videos, "Learn to Draw with Tom Gammill," which, we are assured, “will not teach you how to draw.” In the last video of the evening, I was the butt of the joke, the victim of cruel mockery—as I had been the previous year, when (as I probably told you) Stephan Pastis appeared before the NCS Godfather seeking retribution for my having denigrated his drawing style in Pearls Before Swine by saying his stick figures looked like hors d’oeuvres on toothpicks. This year’s scoffing focused on my biography of Milton Caniff, noting, with fear and loathing, that it is over 900 pages in length. This bibliographic fact was more than cartoonists, who are accustomed to vast quantities of pictures but apparently go all aghast when confronting verbiage, can endure: most of those in the video expired before they were able to finish the book. And Mell Lazarus, one of the profession’s grand old men for whom pictures as well as words are a challenge, appeared at the end of the video, prone on his back, groaning piteously, weighed down by a copy of my book on his chest. I am told the video was hilarious. Alas, I cannot from my own experience attest to its hilarity: since I am half deaf, I could hear, at best, only half the dialogue, and while the pictures (particularly the one of Lazarus helpless on his back) were hysterically funny, I missed the import of many of the visuals because I could not hear the accompanying dialogue. But if I were to judge the content of this exotic film by the standard set in the rest of the Gammill canon, it must, indeed, have been something else indeed. I spent five or six years researching and writing the Caniff biography, but I must confess that I agree that 900-plus pages is a bit long. It’s intimidating. Frankly, I haven’t read it either. I wrote it. But I haven’t read it. Which is a much more impressive feat, I submit, than producing a comic strip without, like Gammill, being able to draw. Since

this is the second year I’ve functioned in the banquet entertainment as the

goat, I may become a permanent fixture, perhaps eventually sharing some of the

spotlight Roy Doty enjoys in the role because of his carping at the biz mtg. But enough kidding around. The Gammill Show transformed the presentation of the revered NCS awards into a bad sitcom. His comedy on stage and in videos was execrable, but it was atrocious by design. And it was therefore perfect for the occasion. Cartoonists have a high regard for the NCS awards and those who receive them feel suitably honored, but cartoonists are essentially satirists and they don’t like to be seen taking themselves so seriously, so Gammill’s parody of cartooning—in both his strips and in his video enactments of a bumbling cartoonist’s life (his pained grin on continual display)—and his lamentable jokes and skits are the perfect antidote for the occasion. Without them, the Reuben Banquet would seem much too self-important. And now, the award winners.

JUST AS WE HAD TO WAIT ALL WEEKEND to learn who won what, so have I dangled you upon similar tenterhooks. But now we get to the piece de resistance. The awards part of the program began with the presentation of the Jay Kennedy Scholarship to Diana Huh, followed by awarding the Silver T-Square “for outstanding service or contributions to the Society or the profession” to Lucy S. Caswell, the retiring curator of the Billy Ireland Library & Museum of Cartoon Art at Ohio State University. Next Roy Doty and R.O. Blechman received their awards. Then came the procession of “Reuben Division Awards” for excellence in cartooning achievement in various venues of the medium. The jurying for the Division Awards is accomplished by the NCS chapters, whose members select in the assigned category three finalists, of whom one is the winner. All the finalists appear as nominees in the months before the awards are presented, and because being nominated for any of these awards is a distinction in itself—the considered judgment of one’s peers—I’m listing here the nominees as well as the winners in each division, identifying the latter with an asterisk before their names; those with two asterisks were not present to receive their awards. NEWSPAPER COMIC STRIP—*Jeff Parker and Steve Kelley, Duston; Brian Basset, Red and Rover; Richard Thompson, Cul de Sac; NEWSPAPER PANEL CARTOON —**Glenn McCoy, Flying McCoys; Chad Carpenter, Tundra; Doug Bratton, Pop Culture Therapy; EDITORIAL CARTOON—*Gary Varvel, Mike Lester, Bob Gorrell; MAGAZINE FEATURE/MAGAZINE ILLUSTRATION—*Anton Emdin, Tom Richmond, Lou Brooks; MAGAZINE GAG CARTOON—**Gary McCoy, Zachary Kanin, Bob Eckstein; GRAPHIC NOVEL—**Joyce Farmer, Special Exits; James Sturm, Market Day; Darwyn Cooke, The Outfit; BOOK ILLUSTRATION—*Mike Lester, Jared Lee, Sandra Boynton; FEATURE ANIMATION—**Nicholas Marlet, Character Designer, How to Train Your Dragon; Glenn Keane, Animation Director, Tangled; Dean DeBlois, Chris Sanders, Directors, How to Train Your Dragon; TV ANIMATION—**Dave Filoni, Supervising Director/Production Designer, Star Wars: The Clone Wars; Dan Krall, Art Director, Scooby-Doo Mystery Incorporated; Scott Wills, Art Director, Sym-Bionic Titan; NEWSPAPER ILLUSTRATION—*Michael McParlane, Dave Whamond, Sean Kelly; GREETING CARD—**Jim Benton, Dan Collins, Teresa Roberts Logan; COMIC BOOK—**Jill Thompson, Beasts of Burden; Chris Samnee, Thor the Mighty Avenger; Stan Sakai, Usagi Yojimbo; ADVERTISING ILLUSTRATION—*Dave Whamond, Jack Pittman, Anton Emdin. Of the 13 division awards, 7 were presented to people who weren’t there. This has happened before, and Gammill had prepared for the likelihood. Assisting in presenting the trophies to the winners were two attractive young women wearing very short but very puffy dresses, gathered above the knee. When the announced winner wasn’t present, one of these leggy chorines leaped to the microphone and accepted the award for the absentee, squealing outrageously in feigned delight. Nicely, satirically, done, but it doesn’t mask a lurking suspicion: since over half the recipients were no-shows, their absence may signal the decline in the stature of the NCS awards. Perhaps there are too many of them, offered, in some instances, to rather esoteric realms of endeavor. Maybe that’s why not all the nominees bother to come to the ceremony. Or perhaps in many of those categories, other awards bestowed by other organizations are more prestigious. Not likely. Most of the NCS awards have been around since the mid-1950s: the first awards for Advertising Illustration, Editorial Cartoon, Magazine Gag Cartoon, Newspaper Panel Cartoon, and Comic Book were made in 1956; in 1957, awards for Sports Cartoon, Animation, and Humor Comic Strip were first conferred. Over the years, the categories have shifted somewhat as the Society sought a more refined definition of some. For a decade or so (1970-1981), the Comic Book category was divided into Humor and Story; then the two were rejoined in 1982. The Comic Strip performed the same evolution (in 1960 and 1989). Animation was divided into Feature and Television in 1995. And Illustration kept dividing (into Book and Magazine) and reuniting for several indecisive years. The most recent addition to the array is Greeting Card (added in 1991) and New Media for computer-related efforts (added in 2000 but apparently abandoned in 2002). Clearly, the Reuben Division Awards have a distinction that accrues to such enterprises as they age. Most of them are well over half-a-century old, old enough for prestige. No, we must look elsewhere for an explanation of the half-hearted attendance by would-be award winners. And perhaps no explanation is necessary because my observation is itself jaded and mean-spirited. Before we leave the premises, however, let me make it clear that nothing I have said should be interpreted as disparaging the achievements of the cartoonists who were nominated for NCS awards. This year, as in most others, the list of nominees includes highly accomplished practitioners of the arts of cartooning. Not a slouch, I would say, among them. Each of them deserves his/her nomination; and any of the nominees in any category would likewise deserve to win. They’re all that good. Beyond that, we should also celebrate the NCS itself: it is a joy and a delight to witness a professional organization, whose members individually are usually in life-or-death commercial competition with each other, taking some time to recognize the superior work of some of its members. When the Society was founded in 1946, there were those who said it would never last because its premise was flawed. The cartoonists who started the club were mostly syndicated cartoonists and therefore competing for the same limited space in newspapers, and the expectation that this essentially antagonistic bunch would band together under friendly terms was, obviously, delusional. That was 66 years ago, and the club is still plugging happily along. Which brings us, giddily enough, to the Very Thing that gives the festivities its reason for being and its name—the Reuben Award.

THE REUBEN is the name given to the trophy given to the “cartoonist of the year.” The official name of the winner in this competition is “best cartoonist of the year” or “outstanding cartoonist of the year.” But that designation has always bothered me. As a purely semantic matter, “best/outstanding cartoonist of the year” implies that the recipient has done something in a given year that makes him better than his peers that year. A generally indefensible proposition. To say, for instance, that Willard Mullin, the sports cartoonist whose stylistic mannerisms shaped the genre in which he worked, did something unusually good in the year 1954 for which he received the accolade “best cartoonist” overlooks entirely the otherwise obvious fact that his performance as a sports cartoonist was “the best” in that endeavor almost every year he drew sports cartoons. He did nothing better in 1954 than he’d been doing: it was all gloriously superior work. The first to receive the Society’s award as “best cartoonist of the year” was Milton Caniff, who got it in the spring of 1947 for work done the previous year. Official records for years say he got it for Steve Canyon. But that was a blatant impossibility: Steve Canyon started in January 1947. In 1946, the supposed year for which he got the award, Caniff was doing Terry and the Pirates. Probably Caniff wasn’t named “best cartoonist of the year” for either of his strips. By 1947, Caniff enjoyed such national renown that the cartooning fraternity would trot him out as a spokesman any time they needed someone distinguished to represent the profession. Beyond that, he’d made a considerable splash in the trade papers and public prints alike with the debut of Steve Canyon, which, it was loudly proclaimed, he owned himself: it was his, not the syndicate’s. At the time, virtually all comic strips were owned by the syndicates that distributed them; Caniff was not the only cartoonist to own his creation (Chic Young owned Blondie; Gene Ahern owned Judge Puffle—his King Features re-enactment of his own popular NEA Major Hoople); Roy Crane owned Buz Sawyer), but due to his popularity during World War II—and to his undeniable superiority at his craft—Caniff was the most visible of the “serious artists” who produced comic strips, and so his ownership was widely heralded as a unique, perhaps a trail-blazing, achievement, deserving, without a doubt, of recognizing him as the “best” cartoonist of that year. At the time, the Society viewed the “best cartoonist of the year” distinction as something of a promotional gimmick: it was expected, even overtly intended, that the cartoonist so designated would deploy the designation to help market his work. Since Caniff had no interest in promoting Terry and the Pirates any more, it was Steve Canyon that was attached to his name in the official NCS records—and in press reports of the achievement. (This historic ulterior function of Caniff’s winning in 1947 has been winnowed into extinction by the current leadership of the Society: although the most recent membership directory, dated 2005, begins its list of Reuben winners with Caniff and Steve Canyon, this year’s Reuben Journal, the souvenir program of the awards weekend, “corrects” the error and claims he won in 1947 for Terry and the Pirates. Logical but not accurate, as much history often is.) In short, the very first “best cartoonist of the year” probably earned the distinction in part by reason of his professional stature, but it was his actual achievement that year—his triumph in acquiring ownership of his syndicated strip—that sealed the deal. But none of the subsequent designees did anything special in the year for which they won the honor, nothing that would qualify them as the “best” for that particular year. Moreover, their “best” work may not have been done in that year, so even the narrowest interpretation of the term’s meaning isn’t, usually, applicable. Finally, to call one cartoonist the “best” implies that the others aren’t quite up to the mark that year, which is not, I submit, the Society’s intention. Consequently, I usually eliminate “best” when talking about the Reuben winner and speak only of the “cartoonist of the year,” an appellation that seems purely nominal and avoids stigmatizing everyone else. The “cartoonist of the year” is simply the one the Society singles out that year to congratulate and celebrate—usually because of the consistent excellence of his or her work. Incidentally, it’s possible that no ballots were cast the first year the award was made. The trophy, a silver cigarette box, was supplied by the widow of Billy DeBeck, who said she would furnish a suitably elegant trophy if the Society were to institute a “best cartoonist of the year” award and name it for her deceased husband, who had made a national institution of his comic strip, Barney Google (who was later joined in the title by a cantankerous hillbilly named Snuffy Smith). Caniff told me that Mrs. DeBeck chose the recipient of the first award; as far as Caniff knew, no one voted. If so, that would change almost at once (or perhaps Caniff was mistaken about the voting). The trophy itself, that silver cigarette box, was engraved with the Barney Google ensemble. It was officially named the Billy DeBeck Memorial Award; in some quarters, it was called “the Barney,” in obvious imitation of the Academy Awards’ Oscar. Caniff, by the way, had given up smoking a couple years earlier to commemorate the end of World War II. In 1953—after the death of DeBeck's widow—the Barney was retired and replaced by a heavy metal statuette, the Reuben (a representation of which appears at the opening paragraph of this Opus). It was named in honor of NCS's first president, Rube Goldberg, and the trophy was pure Goldberg. In fact, it was cast from a sculpture that Rube himself made. A whimsical creation by the man who had made his name synonymous with outlandish inventions, the statuette is a comical pile of nondescript but definitely nude male characters of the cartoony kind, who had attempted, apparently, to form a human pyramid and had enjoyed modest success in the attempt—as much success, that is, as any Goldberg invention ever achieved. The sculptor explained his creation as follows: “If you have been influenced by Freud you might say that the Reuben represents four cartoonists who hated their mothers for allowing them to become cartoonists and [who grope] for an acrobatic answer to the question of why sculptors and pretzel makers have so much in common. Or you might say that the Reuben represents the people of the world striving for a perfect balance to escape the same fate as the leaning tower of Pisa. You'd be wrong on both counts. The Reuben is pure fantasy, including the bottle of India ink that Bill Crawford placed on the posterior of the top man to give the design a little more symmetry. If the Reuben has an underlying significance in its present form, I will say that I created it to keep it from looking like a golf trophy, an Oscar, or a statuette presented to Miss Kitchen Utensils of 1953. My only hope is that each recipient will look upon it as a symbol of the admiration and love of his fellow cartoonists.” But Goldberg's explanation was just another of his inventions. He didn't create the sculpture to serve as the NCS award: when he made it, he thought he was making a lamp. The light bulb screwed into the aforementioned posterior of the uppermost figure. Happily, fellow cartoonist Crawford saw this objet d'art in Rube's home at just about the time the Society was looking for a trophy to present to the “cartoonist of the year,” and he recognized at once that Goldberg's lamp was destined for greater things. He substituted a bottle of ink for the light bulb and made a cast for the trophy. The first to receive the Reuben in all its glory, trophy and fanfare, was the sports cartoonist Willard Mullin. Rube received the trophy named for him in 1967, three years before he died. (The eight cartoonists who had won the Billy DeBeck Award for the years 1946-1953 were subsequently presented with Reuben statuettes and are termed Reuben winners in the annals of the Society.) The

honor of announcing the “cartoonist of the year” and bestowing the Reuben was,

for a time, assigned to the Reuben winner of the previous year. Lately,

however, the honor has fallen to a previous winner who is also one of the

Society’s elder statesman, Mort Walker, whose Reuben dates from 1953

when Beetle Bailey was only three years old. By then, Beetle had been in

the army only a couple years, but Walker’s shift of his strip’s milieu from

college campus to army barracks had already begun to catapult the strip’s

circulation. This year in Boston, after entertaining the assembled multitudes

with a story about how Charles Schulz became a member of NCS and then,

soon thereafter, won the Reuben—in 1955, for a strip just five years old—Walker

opened the envelope and announced this year’s “cartoonist of the year,” Richard

Thompson, who produces the comic strip Cul de Sac, which has been in

syndication for only three-and-a-half years. Runners-up were animation director Glen Keane and Stephan Pastis, who produces the comic strip Pearls

Before Swine. ANIMATOR, AUTHOR, ILLUSTRATOR and director, Keane is best known for his character animation at Walt Disney Studios in feature films including “The Little Mermaid,” “The Rescuers Down Under,” “Aladdin,” “Beauty and the Beast,” “Pocahontas,” the notably feral animation of the title character in “Tarzan,” and, most recently, “Tangle.” Keane received the 1992 Annie Award for character animation and the 2007 Winsor McCay Award for lifetime contribution to the field of animation. The son of cartoonist Bil Keane, Glen was “Billy” in his father’s newspaper panel cartoon, The Family Circus. At Disney, Keane became one of the group of young animators sometimes referred to as the “Nine New Men,” an allusion to the Nine Old Men, the animators who shaped classic Disney animation in the thirties and forties. Keane was the lead animator for Long John Silver in “Treasure Planet,” and in 2003, he began work as the director of “Tangled,” in which he and his team hoped to bring the style and warmth of traditional cel animation to computer animation, but in October 2008, due, Wikipedia says, to some “non-life-threatening health issues,” Keane stepped back as director, remaining the film’s executive producer and an animating director. Pastis, who was nominated in 2009 and 2010 and whose biceps rival Richmond’s, was a lawyer for ten years before earning a living as a cartoonist. But he doodled cartoons even while in the toils of litigation. “I hated being a lawyer,” he said in an interview published in the San Diego Comic-Con Magazine in the winter 2009; so he began submitting to syndicates ideas for a comic strip. They were roundly rejected. Then he took a character from one strip, Rat, and paired him with a character from another submission, Pig, and the unlikely team-up, in which two divergent personalities teetered in precarious balance, clicked. But Pearls Before Swine did not debut in newspapers: “They tested the strip online on Comics.com, starting in November of 2000,” Pastis said, “and a month later, it turns out that Scott Adams (Dilbert), who I did not know at the time, had been reading the strip and he liked it, and he told all his readers to go read it and—man! the hits just skyrocketed over night.” So his syndicate, United Feature, moved Pearls into print. The strip is now in about 600 newspapers. Pastis sees himself as more of a writer than a cartoonist. “If I have any skill in this business, it’s the writing,” he told the Daily Nebraskan, the campus newspaper at the University of Nebraska. “If you can write a joke well enough, you can illustrate it with stick figures,” he continued, confessing his guilt. Naturally, he believes comic strips are more about writing than drawing. “If you can draw, great. But if you can only have one skill, drawing or writing, most people would tell you the writing is more important. ... If comics were all about art, all of the big hits would come from art school graduates. But, for example, Bill Amend, who does FoxTrot, was a physicist; Scott Adams, an engineer; and I was a lawyer,” he added, putting himself, justifiably, in the same class of hit-maker as Amend and Adams. Appropriately enough for a writer, Pastis admires Ernest Hemingway—and for a reason that makes premeditated sense for a cartoonist. “A lot of people can’t get past Hemingway the man,” he said, “but if you focus on the writing, he’s the perfect writer for a cartoonist because comic strips are all about economy of words, and that is what Hemingway is all about. I read the same short story every time; it’s called ‘A Clean, Well-lighted Place.’” Pastis thinks his drawing is “okay” but admits it is “mediocre” compared to Thompson’s. “Sundays are tough,” Pastis went on, “because you’ve got to really show it on Sunday. Talking heads don’t always work. You’ve got to get a little more stuff in there. So for someone like me, it’s a challenge.” Pastis and Thompson are good friends, and Pastis thinks “Richard is phenomenally talented. ... He draws incredibly.” Pastis is not alone in holding Thompson’s work in high regard. Bill Watterson, whose Calvin and Hobbes won accolades for its artwork, says he “just slobbers” over Thompson’s drawings. Writing the introduction to the first reprint collection, Cul de Sac: This Exit, Watterson praised Thompson’s language, subtlety and whimsy, writing that the strip “has it all—intelligence, gentle humor, a delightful way with words, and, most surprising of all, wonderful, wonderful drawings. It’s a wonderful surprise to see that this level of talent is still out there,” Watterson went on elsewhere, “and that a strip like this is still possible.” Interviewed by ComicRiffs’ Michael Cavna, Watterson said that Thompson “has this huge range of cartooning skills. Richard draws all sorts of complex stuff—architecture, traffic jams, playground sets—that I would never touch. And how does he accomplish this? Well, I like to imagine him ignoring his family, living on caffeine and sugar, with his feet in a bucket of ice, working 20 hours a day. Otherwise, it’s not really fair.” Doonesbury’s Garry Trudeau said: “Of all the new comics I’ve read, only two registered as winners immediately—literally within a strip or two. The first was Calvin and Hobbes. Nineteen years later, it was Cul de Sac. A distinctive, fully evolved drawing style married to consistently funny, character-driven wit—we don’t see this often.” The extravagant admiration of Thompson’s drawing ability by other cartoonists is for the lay reader perhaps a little hard to understand. Anatomically, the figures are scarcely so fully realized as to serve as models; the figures are composed of simple geometric assemblages of circles for heads, squares for bodies, and tubes for arms and legs. The drawings sometimes seem preliminary rather than polished: we can often see the line that outlines the circle of the young heroine’s head through her nose as if Thompson hasn’t quite refined his sketch into a final drawing. His pictures bristle with sketchy scratching—casual and informal perhaps, even seeming careless—but the congeries of such lines form filigrees of thin and fragile lines. And that is what fellow cartoonists extol so enthusiastically—the simple linework, enhanced—made complex and solid appearing—by laying in variegated textures, cross-hatches, patterns, and swirls and flecks for body and modeling. “Richard dances down the thin line between something and nothing, line and volume, two dimensions and three,” says Henry Allen, a Pulitzer-winning culture critic who once edited Thompson’s contributions to the Post’s Style section. Editorial cartooning giant Pat Oliphant “revels” (says Cavna) in Thompson’s gift with pen and brush: “From the beginning of my observation,” Oliphant said, “his drawing line has been as sophisticated as his sense of humor. The bugger is indeed a genius.” No appreciation of cartoon artistry can long avoid coming to grips with the impulse that drives those who draw. Some things are more fun to draw than others, Thompson acknowledges, and “some days I give myself something fun to draw and some days something hard. Unless I’m feeling lazy; then it’s all just talking heads.” Like all cartoonists—and everyone who draws—Thompson is forever engaged, drawing by drawing, in a continual search for the perfect line. Says he: “The perfect line would be some combination of Ronald Searle and George Herriman. But then, that line would be so perfect, it wouldn’t be human.” In the age of the emerging stick figure, it is refreshing—invigorating—to see actual drawing skill lauded so loudly. But Thompson’s talent doesn’t end with his drawing ability: his lines, interesting and sublime in their simplicity and complexity, merely visualize the world he has created in Cul de Sac, which Cavna describes as “a sly, whimsical skip through suburban life with Alice Otterloop, her friends Beni and Dill, elder brother Petey and her classmates at Blisshaven Academy preschool. It’s all about sidewalk discoveries, childhood invention, parents and other authority figures who are one step behind the children’s antics. At summoning our early years, Watterson says, ‘The strip depicts all kinds of moments than ring true.’” Oliphant says: “Thompson actually sounds like the kids he draws in that amazing strip. What a gift that is, to write the way you talk. No strain, no presumption—just simple, wry storytelling with characters you can care about and love. When did you last see that in comics strips? Not since Calvin and his tiger rode off into the sunset. You would never suspect it by looking at him, but behind the quiet, mild-mannered Richard Thompson exterior lurks the real Richard Thompson. I know he would hate to be termed a genius, but that is exactly what he is.” Praise like this nearly overwhelms the unprepossessing Thompson, who shies away, leaving a fragment of his wit: “That’s something that makes me blush hard enough to induce a nosebleed.” Pastis agrees with Oliphant, saying his friend’s strip should be in every paper in the country. “There is a unique voice there,” he said. “I saw ten of his dailies when he first started. They were the samples that his syndicate, Universal, had put on their site. It was amazing. I mean, just little touches like the size of the father’s car, this tiny little car, and you know there’s something that hits you so hard about that. Like your father should be your defender; he should be strong. And to have a father who is so weak or whatever that his car can fall into a little hole in a sandbox and be lost—that’s an absolutely, utterly crazy, brilliant mind, and they don’t come along very often. He should be in 2,000 papers as far as I’m concerned.” Cul de Sac, however, is in only about 150 papers. Clearly, it’s not impressive circulation that won the admiration of Thompson’s peers. Nor is it longevity: the strip has been syndicated for just over three years. Only Watterson, who won his first Reuben in 1986 when his strip was less than two years old, attracted the applause of the inky-fingered fraternity in less time than Thompson. Thompson’s achievement, then lies in the uniqueness of his vision as well as in his skill in translating that vision. My introduction to Thompson’s cartooning was a 2004 booklet reprinting a selection of his weekly cartoon, Richard’s Poor Almanac, that he produced for the Washington Post. In this slim paperback volume, I met Thompson at his most playful, his drawings rich in caricature and textures, his comedic concepts springing from one to the next with only a nodding acquaintance between them. His pictures are funny enough by themselves, but the comedy arises in equal measure from the words, sometimes as simple verbal constructs independent of the accompanying drawings. Typically, Thompson’s humor is not of the punchline sort. He is an adept at language, and he flings it around, having a great Frisby-like time conjuring up unlikely juxtapositions and comic coinages. One Almanac offering is entitled “Manifest Disney,” the title lettered in the familiar “Disney signature” style. Elsewhere, for two pages, Thompson provides descriptions of band instruments in an effort to help readers find the “right one for you.” The bagpipe “features two settings, ‘on’ and ‘really loud.’” The Glockenspiel, he advises, “is about as musical as a baby’s pull-toy. You might as well just jingle the loose change in your pants pocket.” An inspired description. Two pages are devoted to depicting different kinds of trick-or-treaters on Hallowe’en. In the penultimate panel, we encounter a hysterical personage who shouts: “I’m the Spirit of Unreasoning Fear! Red Alert! Boil your water! Boil your mail!” Boil your water? Where did that come from? By a leapfrogging free association, Thompson goes from a danger signal—Red Alert—to the folkloric remedy for contaminated water, and from there to the next wildly improbable threat—the mail. (Or is it improbable? Anthrax was only a couple years in the past.) The next Thompson oeuvre I witnessed was Cul de Sac itself. While I admired his playful renderings, it wasn’t until I saw the strip in which Alice is watching excavation for new houses that I was thoroughly and permanently smitten. Beni, standing next to Alice, observes a backhoe at work and says: “Look, they’re digging for new houses.” To which Alice, quite reasonably, says: “Is that how they get new houses? Dig for them like potatoes?” The logic is high comedy. Cul de Sac has been compared to Calvin and Hobbes, but the comic sensibility is not at all the same. Calvin and Alice are both imaginative, but Calvin’s imagination is not so childlike as Alice’s. Calvin is Watterson being a kid—or, rather, Watterson imagining himself a kid but with his adult abilities intact so that he can not only achieve his wildest imaginings but enhance those imaginings with the empowering energy of mature creativity. When Calvin and Hobbes put the loose end of the roll of toilet paper into the toilet and flush, delighting hysterically in the frantic revolutions of the roll of tissue as it unrolls, its entire length pulled inexorably into the maelstrom by the cascading water, they are implementing a highly sophisticated scheme. It’s not a kid’s prank; it’s an adult’s. In contrast, Alice’s enterprises are wholly childlike. Determining that rocks are too glum, she paints smiley faces on “millions of them” and “releases them into the wild for everyone to enjoy.” The joke arises when we see her brother Petey, en route to school, cringing and hesitating because, he says, “I keep feeling like I’m being stared at and laughed at.” No wonder: the lawn he’s standing near is infested with smiley-faced rocks that his sister has “released.” Once he’d decided to do a strip about kids, Thompson said, “Alice and Petey came into focus pretty quickly. I knew they should be opposites; I thought of them as an irresistible force and an immovable object. Alice is a type that’d been done before in strips, the wild little hellion.” He had Beverly Cleary’s Ramona the Pest in mind. Petey, on the other hand, is a more original if also more predictable creation. Said Thompson: “As a comic strip character, Petey seemed like unexplored territory. He’s an anhedonic contrarian, fussy, picky and inert, with a fear of change. The combination of Alice and Pete is what makes the strip interesting to me.” Petey likes comics, but “his taste in comics is like his taste in most things,” Thompson went on. “When I was putting his character together in my head, I knew he wouldn’t like superheroes or violent action comics.” Instead, Petey is a devotee of “Little Neuro,” an invocation of Winsor McCay’s brilliant turn-of-the-last-century creation. “Little Neuro is a parody of Little Nemo,” Thompson explained: “he’s a little boy practically bedridden by neuroses who prefers to avoid adventures. He’s inert and therefore perfect for Petey.” Alice, on the other hand, is all carefree adventure and freefall experimentation. “Alice has my obliviousness to what’s going on,” Thompson told Cavna. “Petey is much closer to me, or at least the worst of me. He worries about dumb things; he’s a perfectionist when it’s unnecessary; he deals with the world best at a distance. One of my favorite things to do with him is to take him out of his comfort zone. ... Fish-out-of-water is always a great plot device—and Petey swims in a very small bowl.” “Alice has no filters,” said Watterson in appreciation. “Petey is all filter. What a window into introversion and the childhood craving for stability, order and control.” Still, as a character Petey is much more predictable than his younger sister: we know he’ll shy away from almost anything outside his bedroom. With Alice, we never know what she’ll do next. She is the other aspect of childhood: she’s eager for experience. All the kids in the strip are almost entirely self-absorbed: they live in their own worlds, derived from their tenuous grasp of reality, and they are so self-centered that they often talk past each other, failing to connect. Thompson, as usual, is perfectly aware of what he’s doing: “Each of the characters is off in his or her own little world,” he said at CcomicBookResources.com, “and the strip is about the small places where they overlap. I’ve always had a feeling that life is a series of non-sequiturs, and that we’re all untrustworthy narrators. The friction among the clashing points of view is an important part of the strip. It makes it richer and livelier and lets me have several things going on at once. It also lets me build strips on what might otherwise be pretty thin material, like following bugs, buying sneakers, going over a bump in the sidewalk with a kiddie car. And it puts the burden of the strip on the strength of the characters: if they don’t have an interesting point of view, the material falls apart.” Before Alice and Cul de Sac, Thompson, who has lived for nearly half his 53 years in the suburbs of Washington, D.C., earned his living as a freelance illustrator, doing work for government agencies and assorted publications, collecting honors as he drew. He won a Gold and a Silver Funny Bone Award from the Society of Illustrators for humorous illustration in 1989, and in 1995, he picked up two Reuben Division Awards from NCS—for Best Magazine/Book Illustration and for Best Newspaper Illustration. Soon thereafter, he began producing Richard’s Poor Almanac for the Post in the paper’s Saturday Style section. “The reason I got the Almanac gig was the work I did on a column the Post ran called Why Things Are. It was written by Joel Achenbach, who answered any odd or interesting question thrown at him by readers from the ridiculous to the sublime, and the editor gave me free reign to do whatever I wanted as long as it was at least tangentially about the given subject. So I ended up doing the illustrations as free-standing cartoons with dialogue in balloons and as many gags as I could cram in. Drawing a real cartoon as the next logical step,” Thompson told Tom Spurgeon at ComicsReporter.com, “and I thank the Washington Post for pushing me into that next logical step,” he added at ComicBookResources.com. The editor who hired Thompson to decorate Achenbach’s column was Gene Weingarten, now the Post’s humor columnist. When Achenbach’s column ended sometime around 1995, Weingarten phoned Thompson and asked him to try a weekly cartoon. “He’s a dream editor to work with,” Thompson said, “you just want to make him laugh good and hard, especially at something inappropriate. We had lunch and then, a year later, I gave him a couple dozen roughs and he said, ‘Okay—it took you long enough; let’s go.’ It started in June 1997 without an actual title.” Thompson remembered one of the cartoons about the one-eyed man who was king in the country of the blind—related, as we’ll see in the Thompson Gallery below, to nothing beyond its borders. “Who knows what this stuff was doing in a respected newspaper,” Thompson marveled, “but it cracked me up, and Gene liked it, and nobody actively complained. I was always expecting it to be plowed under and replaced by tire ads or garden center coupons. I’d calm my fears with the likelihood that no one was actually reading it, so why worry if the jokes made sense to anyone else?” Thompson’s third editor in the Style section, Tom Shroder, finally gave the feature a title in approximately 1999: “I’d included a reference to ‘Richard’s Poor Almanac’ in one cartoon,” Thompson remembered, “and he said, ‘Call it that.’” Shroder also urged the cartoonist to develop a weekly comic strip about Washington, but Thompson, as usual, procrastinated. It wasn’t until 2003 that he found his inspiration, as reported by Cavna. Thompson was dropping off his daughter at preschool, and he saw a “button-down woman” doing the same thing and started thinking: “This is a strange little place they’ve got going here. This single mom had a pretty good government job, dressing up every day, to go work on slightly more momentous things. Just then the mom picked up one of those plastic hamster balls, and suddenly a real hamster popped out. The mother reared back and shrieked: ‘My God—it’s alive!’” In that moment, Cavna says, Cul de Sac was born: “I was struck by adults trying to deal with this childhood reality,” Thompson said. “They were completely out of their depth, with these four-year-olds running around.” Shortly thereafter, on February 4, 2004, Cul de Sac and Alice Otterloop debuted in the Sunday Post, her surname an allusion to the suburban life beyond the D.C. beltway, in the “outer loop” of Montgomery County that Thompson loves. Alice and her friends had appeared in the Almanac before that, as anonymous “mouthy little kids” at a toddler’s roundtable “venting on the issues of the day,” Thompson said. In Cul de Sac, they acquired names and absorbed Thompson’s attention. “I don’t fool myself that the kids are particularly realistic,” he said, “but I think their concerns are those that a child would have, and their fears and the small things that they notice are true to a child’s way of thinking. A friend said the strip describes how, to a child, life is often a pile of unfamiliar things that they need to sort and understand. I like that.” Much of the subsequent Cul de Sac ambiance draws from the same well: “If you watch Alice’s mother,” Thompson wrote about one of the strips, “she is often doing odd chores: carrying things, fixing things, writing things—nothing too odd or weird, but nothing too easily identifiable. This is how I imagine a child views a parent: someone who’s always busy at some activity that the child doesn’t understand or much care about.” A couple years after the Sunday Cul de Sac started in the Post, Lee Salem, Universal Uclick’s top comics executive, spied one of Thompson’s Almanac entries—a free verse “poem” the lines of which are made up of George W. Bush’s malapropisms. Entitled “Make the Pie Higher,” it had gone viral through the Web soon after GeeDubya’s inauguration (see our Thompson Gallery down the scroll). Salem liked it and sent Thompson a note, asking if he’d ever thought about syndication. Although initially intimidated by the prospect of coming up with ideas for a daily comic strip, Thompson realized that he really wanted it: “I began wondering what my characters were doing the rest of the week, beyond Sunday-to-Sunday,” he told Cavna. “Obviously, they take on a life of their own—a novelist would tell you this—and they demand some kind of say in it.” On September 10, 2007, Alice and her friends started in 70 of the nation’s newspapers. It was, Thompson admits, the worst possible time to start a new comic strip. And “the worst possible time” has been going on for several years now. Said Trudeau: “Richard’s only apparent weakness is his timing: in a fair world, his brilliant reimagining of childhood would rule the comics page, but shrinking pages have compelled comics editors to fight a cautious rear-guard action, defending the tried-and-true at the expense of the new.” “Talent gravitates were it can have an impact,” adds Watterson. “Newspaper comic strips are still the high end of cartooning with daily audience in the tens of millions, but the mass-media model seems to be disintegrating before our eyes.” Thompson, however, was focused on the task at hand, not the changing climate for newspaper comic strips. “When I was doing Cul de Sac as a Sunday only feature,” he told ComicBookResources, “I tried to cram as much stuff into each strip as I could so that each was almost the equal of a full week of dailies. ... When it was syndicated and I had to fill seven days, I felt less compelled to squeeze so much stuff in. ... I also felt freer to stretch things over a wider span of time, and to focus on something tiny, to do silly little stuff like a full week of Dill following a bug across the lawn. The catch, of course, is to make the silly little stuff comically compelling.” THE OTHER CATCH, fate’s cruel quirk, is that about a year after Cul de Sac went into syndication, Thompson learned that he had Parkinson’s, the incurable neurodegenerative disease that slowly robs its victims of motor skills. He wrote about it on his blog on May 16, 2009: “For the last year or so, I’ve noticed a few odd symptoms: shakiness, hoarseness, silly walks, random clumsiness and the like. So the other day, I went to see a neurologist and, after having me jump through hoops, stand on my head and juggle chain saws, he said I’ve got Parkinson’s. It’s a pain in the fundament and it slows me down, but it hasn’t really affected my drawing hand at all, and it’s treatable. And it could be a useful ploy in my ever-losing battle against deadlines.” Peter Dunlap-Shohl, formerly editorial cartoonist at the Anchorage Daily News, who was diagnosed with the disease in 2002, said about it: “Getting diagnosed with this disease is to have your world struck by a meteor, transformed to ash in an instant of unexpected impact. ... All I could focus on were the words progressive, incurable, and disabling.” In his blog announcement, Thompson stressed the comically compelling—juggling with chain saws and outmaneuvering his deadlines. He takes pills four times a day and keeps on drawing. Going to the podium to accept the Reuben, he walked slowly, almost tentatively, but, at last, he grasped the heavy metal trophy and expressed his pleasure and gratitude at winning it. Later, at his blog, he said: “I'm grateful in countless ways, not the least being that I didn't fall over.” Irrepressible.

INTERVIEWED TOGETHER for the San Diego Comic-Con Magazine, Pastis and Thompson speculated about the future of comic strips. Pastis correctly sees the future of the medium tied to the future of the newspaper: “I come back to a couple of key things,” he said. “Number one, there will always be a need for local news. That is just a given. How it’s delivered to you, I don’t know; but that survives somehow. Number two, my parents’ generation—people in their sixties or so—are still getting the paper every day. They’ve got another 15 years or so left, and that’s just enough time for me to get my kids through college, so that’s all I’m going to worry about.” Thompson was a little less satirical. If newspapers collapse, he might consider doing something online that would eventually be turned into a book of the printed sort. But generally, he said, “I try not to think about it. There’s some future for comic strips, just like there’s some future for newspapers, and nobody knows what that is either. I’m the wrong one to ask, you know. I’m just trying to draw these things every day.” Each day with Parkinson’s, he says, brings “a new normality.” And as Cavna observed: “Each day also brings the chance to sit at the drafting board, ink-dipped crowquill in hand, and explore new worlds. As Alice says, ‘Every day, I test the boundaries of my dream.’” Now, the touted Thompson Gallery, pictures of the cartoonist, some of his caricatures of notable persons, GeeDuby’s “Higher Pie,” and other samples from Richard’s Poor Almanac; then a tiny smatter of Cul de Sac.

QUOTES AND MOTS “Cul de Sac may be the end of the road for syndicated newspaper strips,” said Art Spiegelman, “but what a classy place to get turned around.” “Success is a great deodorant. It takes away all your past smells.”—Elizabeth Taylor “Love is only a dirty trick played on us to achieve the continuation of the species.”—W. Somerset Maugham “No one really listens to anyone else, and if you try it for a while, you’ll see why.”—Mignon McLaughlin