|

||||||||

Opus 271 (Christmas 2010). Yes, welcome to the Christmas edition of Rancid Raves, kimo sabe. I realize that it’s too late for Christmas. Then again, maybe it’s never too late for Christmas. Maybe, as the youngest amongst us often wish, Christmas should last all year. In any event, regardless, here’s our anyule greeting.

On down the scroll below, we have Part One of Part Two of our Yuletide reader service, the Christmas Wish List. Just as we are too late for Christmas, we are too late for the Wish List to be of use to your spouse as a handy guide to books you might want to find gaily packaged under the tree on Christmas morn. We’re too late for Christmas morn, too. But maybe that doesn’t matter so much. After all, who would give this list to his/her spouse anyhow? Do you trust that personage enough to make the right choices from the list? Maybe; maybe not. Let’s suppose you don’t. Not on such an important matter as this. By way of rationalizing our criminal procrastination and dereliction of duty, then, we submit that the Christmas Wish List is of much greater utilitarian value to you than to your spouse: you need it for your post-Christmas shopping spree during which you will be diligently questing the best ways to spend the money your Great Aunt Mildred gifted you with. Among the best ways is to buy some of the books reviewed below. Or you could buy some of the books listed in our “Books” department (click here or on “Books” in the red at the left). In my feverish attempt to lay hands on every comics-related publication in the known universe, I often mistakenly acquire more than one copy of a single title. When not duplicate copies from my collection, the books offered for sale herein tend to be review copies or contributors' copies (sent to me in multiples, but I need only one for my archives). Most of these, in other words, are new books, often not even read—unless otherwise noted. These surplus tomes I offer for sale in the “Books” department at ridiculously low prices, usually half-price or less. And I’ve recently purged the sale list, removing books that have lingered there for a long time without finding homes. So perusing the list—which includes several brand new acquisitions never seen before at the Rancid Raves Intergalactic Book Department—won’t take you long. And you might find just that treasure you’ve been looking for. Don’t miss out: these are single copies, offered first-come, first-served, and when a title is gone, it’s gone for good. And now, without much further ado, we get to Part One of Part Two of the Christmas Wish List—which arrives as a sort of history of NBM Publishing that includes reviews of more than a dozen old and new books from that enterprise. Next time, which ought to be in two weeks or less, we’ll post Part Two of Part Two, another dozen reviews, long and short, of new books currently on the market. Now, here’s what’s here, in order, by department:

NOUS R US Death at Marvel Flying and Crashing on Broadway Death at Archie Islamic Hooliganism Still At Large Anniversaries Hef to Get Hitched Again Jacques Tati Animated

ZUMA GOES FOR ZAPIRO The Meaning of Life Itself Revisited

EDITOONERY Seasonal Sentimentals Considered

THE FROTH ESTATE Julian Assange’s Sex Crime Described

NBM AND THE EUROPEAN CONNECTION A Dozen NBM Books, Many Recent Ones, Reviewed Including: Corto Maltese, The Story of O, First Time, Aldana, A Home for Mr. Easter, Salvatore, Elephant Man, and Papercutz’s Cyrano de Bergerac (to name a few)

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Stan Lee’s Soldier Zero (again), Traveler, and Starborn Risso’s Jonah Hex Route Des Maisons Rouge

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits On Broadway, Spider-Man continues to fall out of the sky while swinging over the heads of the audience at “Turn off the Dark,” and back at the office, publicity-starved imagination-deprived Marvel honchos have decided that the best way to attract favorable attention in the public prints is to kill off a superhero. Again. This time, they’ve chosen one of the Fantastic Four; which one remains a secret, insuring sold-out status, no doubt, for Fantastic Four No. 587, the purported issue of revelation. And at Archie Comics, the copy-cat industry continues to re-enact its forever rituals, opting for the death of one of its seasoned cast. The once venturesome Archie puppeteers—those who blessed a future Archie to marry Veronica and then Betty—revert to tedious and predictable form in the sixth issue of Life With Archie, the polygamous title that regales us with the future Archie’s marital blisses and blunders: this issue went on sale December 29, with everyone going to the funeral of Ms. Grundy, that caricature of a high school teacher and pickle-factory alum, who has died of cancer. George Gene Gustines at the New York Times quotes Jon Goldwater, co-chief executive of Archie Comics with Nancy Silberkleit, who maintains that the death of Ms. Grundy had been planned since the beginning. “The goal was to tell stories with important, real-world issues that people deal with like death, financial hardship and marriage issues,” he said. To which Gustines adds: “Making Archie’s Riverdale more relevant also led to the introduction of Kevin Keller, the first openly gay resident, who moved to town in September.” Goldwater notes that the eulogies during the Grundy funeral service were the same speeches that Michael Uslan gave for his own teachers; I don’t know whether this peculiar insight underscores the episode being real worldy or just excessively maudlin. Uslan is the writer who concocted last year’s bigamy books. Back on Broadway, the stunt actor who fell 30 feet from ceiling wires on December 20 is back on his feet after back surgery, reported the Associated Press on December 26. And the production has survived the scrutiny of a state safety inspector, who has approved “a new set of very strict safety and security measures” for the musical, which has nearly 40 aerial stunts, ample opportunity for thrills and more injuries. So far (as of December 29), four actors have been injured, and one of them, Natalie Mendoza, who suffered a concussion the first night of previews, is leaving the production because the effect of her injury makes it impossible for her to do upside-down flying stunts. The plight of the actors has started to spark controversy. John Moore, the Denver Post theater critic, begins his report with this: “Actors are expected to suffer for their art. But three fractured vertebrae, a hairline skull fracture, a broken scapula, four broken ribs and a bruised lung? Just to bring Spider-Man to the stage?” Alice Ripley, who opens in Denver with “Next to Normal” on January 4, asks on Twitter: “Does someone have to die?” Moore quotes Los Angeles-based actor Martin Kildare, who believes it’s unfair to ask singers and dancers to perform dangerous stunts that are not within their areas of expertise. Works for me. Maybe Broadway’s most expensive musical ever is just too much of a good thing.

***** The Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly has passed a new law, according to ITmedia and Sankei via Anime News Network, that will regulate anime or manga that “unjustifiably glorify or exaggerate certain sexual acts.” Voluntary self-regulation under the new law takes effect on April 1, 2011, and the restrictions on sale or rental take effect on July 1. Manga publishers are reported as reacting strongly: ten of the largest companies have said they will boycott the Tokyo Anime Fair in protest. Kate Fitzsimons at publishersweekly.com reports that comics writer J. Michael Straczynski, creator of Babylon 5 and scripter of the movie “Changeling,” “has announced he will be leaving his duties on DC's flagship titles Superman and Wonder Woman in order to write a sequel to his popular new original graphic novel, Superman: Earth One. Straczynski started ambitious new storylines on Superman and Wonder Woman, the first involving a flightless walk across the nation; the other, a new costume and backstory, complete with a full memory wipe. These stories will now be completed by Chris Roberson on Superman and Phil Hester on Wonder Woman. More details are available on DC's official blog The Source.” IDW has started releasing digital graphic novels every week for the iPad according to Comics Alliance. Just launched books include Darwyn Cooke’s The Hunter and The Outfit, and Berkeley Breathed’s Bloom County: The Complete Library Volume One. Each book contains all the material found in the print editions, all formatted for full page reading on the iPad. Pricing ranges from $4.99 to $9.99 At

koreatimes.com.kr, we learn that the South Korean Supreme Court on December 23

upheld a ruling that fined a cartoonist 3 million won ($2,600) for drawing a

cartoon containing an offensive comment against President Lee Myung-bak. The

cartoonist, 45, surnamed Choi, was indicted in June last year for writing

abusive words that he hid in the pattern on the monument on the left in the

picture. In the U.S., we can insult our leaders with much less subterfuge. Baracko Bama is often attacked in cartoons by American editoonists, but none of them have been fined yet. As far as I know. Below Choi’s cartoon are two American blasphemes with no disguised messages. The first, by Nate Beeler, suggests that the downpour of tea bags during the Recent Disturbance was brought about by Obama (“The Rainmaker”) and his agenda, so he has no one to blame but himself. Moreover, his agenda is no defense against the wrath of the tea-bag storm and is falling apart under the fury of its onslaught. Blaming the Prez (however mildly) is clearly something not allowed in South Korea. And below Beeler, is a manifestation of Bruce Tinsley’s right-wing tomfoolery in his so-called comic strip, Mallard Fillmore. With a pretty good caricature of Obama, Tinsley is saying that the Prez has little interest in governing or in solving problems; he seems mostly preoccupied with finding ways to blame the GOP for whatever fails—and, thereby, to assure his own re-election in 2012. Cynically, he also blames the Democrats for paving the way to a Republican victory. In South Korea, Tinsley could not get away with displaying so craven a version of the country’s president.

ISLAMIC HOOLIGANISM STILL Five would-be terrorists were arrested on December 29 in Denmark, where they were about to mount a “Mumbai-style” attack on the offices of Jylands-Posten, the newspaper that ignited the Muslim outcry five years ago by publishing cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad. None of the five appear to have connections to the botched December 11 suicide bombing in crowded downtown Stockholm, said the New York Times; the bomber had sent a threatening message to Swedish artist Lars Vilks, who rose to international prominence after drawing pictures in 2007 of Mohammed with a dog’s body. “I’m a constant target,” Vilks said. Meanwhile, Kurt Westergaard, the Dane whose cartoon of Muhammad with a bomb turban is the most notorious of the twelve incendiary pictures published in Jylands-Posten, has written his autobiography, The Man Behind the Lines, which contains a new version of the infamous drawing: in it, the artist, glancing at his 2005 cartoon, has a bomb on his own head, a fairly effective metaphor for the menace that has hung over him ever since. Although Westergaard does not regret the publication of his Muhammad cartoon, he said: "It travels around the world and is used and misused, and the cartoon gets a status as an icon, as I do sometimes, and I am not so happy about that. I'd like back my good old identity as an average, reliable cartoonist who pretty much never missed a deadline," he added at a news conference launching the release of his book. But he maintains that the Danish Dozen (as I call them) “have contributed to starting a necessary debate on freedom of speech. That has caused friction between Muslim and Western Christian democratic cultures and that is something we need to get through. But it should preferably happen peacefully.” His book, he told Reuters, is more than an autobiography: it is also a defense of freedom of speech, adding: “Self censorship is dangerous because you cannot see it. It is not bureaucratic as it is going on inside the heads of people." ANNIVERSARIES GALORE AGAIN. The first Dark Horse books, publisher Mike Richardson tells us in the December issue of Previews, “were pasted up on the counter of a comics shop, a fitting birthplace fo a company born out of the love of comics.” Agreed. To help celebrate the Horse’s 25th anniversary in the coming year, Richardson announced that they’ll be reviving Dark Horse Presents, an omnibus magazine that introduced new artists and comics. And while we’re horsing around, Dark Horse is partnering with Archie Comics to publish Archie Archives, which will reprint the iconic teenager’s exploits, starting with Volume 1's stories from Pep and Jackpot Comics. The immediately expiring year marked the 70th anniversary of Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories. And it was the 100th anniversary of Krazy Kat. Two signal events that we ought to have commemorated extensively here at the Rancid Raves Intergalactic Wurlitzer; but, alas, we nodded off instead. Fate of the gaffer.

***** The world’s most famous frustrated cartoonist, playboy Hugh Hefner, 84, said in a Twitter message early on December 26 that he'd given a ring to “Number One” girlfriend, Playmate Crystal Harris, 23. “This is the happiest Christmas weekend in memory,” Hef said, adding that Crystal burst into tears. This will be Hefner’s third marriage: his first in 1949 was to a highschool sweetheart, Mildred Williams, which ended ten years later after he’d become famous for barenekkidwimmin; his second, to another Playmate, Kimberly Conrad, ended in divorce last year after 21 years (most of which, 11 years, they were separated). As a mildly interested bystander, I suspect that Hef will be no more monogamous now than he has been before. Habits are hard to break for anyone, and for Hefner, perhaps impossible: he has established his satyrical reputation by maintaining an in-house bevy of girlfriends, each of whom can no doubt testify (as at least one has in a book-length tell-all; see Opus 234) to the publisher’s relentless albeit slightly pitiful attempt to sustain an image as an inexhaustible stud. The latest work of French animated filmmaker Sylain Chomet, who brought us “The Triplets of Belleville,” is “The Illusionist,” Entertainment Weekly reports, the title character of which is “an aging old-time French variety-show magician, unsuccessfully peddling his timeworn stage act in the late 1950s to audiences more interested in twist-and-shout rock-&-roll bands.” In appearance and behavior, the fictional magician is a tribute to “the late French comedy treasure Jacques Tati, the legendary Monsieur Hulot of ‘Mr. Hulot’s Holiday’” and is based upon an unproduced script by Tati, “written as a love letter to his own daughter.” In the November Previews, we see an ad for action figures of the characters in the Watchmen movie. One supposes, probably correctly, that the manufacturers will put a speedo on Dr. Manhattan. ... I confess to being either a champion procrastinator or a addle-brained old gaffer: I just remembered that I promised an opus or two ago a report on Ohio State University’s Festival of Cartoon Art, but that report hasn’t yet appeared. (I’ve been looking around, but I don’t see it anywhere.) I’ll do better next year, that is, in 2011, wherein, early on, I’ll finally tell you all about Billy Ireland and the Cartoon Library and Museum, and the Festival of last October. Stay ’tooned.

NEW YEAR’S RESOLUTION. I also resolve (in that time-honored year end custom) to return to the days of yesteryear when the opuses of Rants & Raves came more often and at somewhat lesser length—so one could actually contemplate reading one at a single sitting. This time, Opus 271, marks the beginning of what I hope will be a New Tradition of succinctitude. (Well, relative succinctitude.)

ZUMA GOES FOR CARTOONIST ZAPIRO On December 10, South African editorial cartoonist Jonathan Shapiro, known as Zapiro, was slapped with a R5-million ($756,000) defamation lawsuit by the country’s colorful president, Jacob Zuma, who names as co-defendants the editor of Zapiro’s paper, the Sunday Times, and the publishing entity, Avusa Media. At issue is a Zapiro cartoon published September 7, 2008, that shows Zuma loosening his trousers while various political allies hold Lady Justice down. African National Congress secretary-general Gwede Mantashe then says to Zuma: "Go for it, boss." We published this cartoon with a lengthy discussion of Zapiro’s career and Zuma’s in Opus 263. Zuma maintains that the cartoon humiliated and degraded him and that it was wrongful and defamatory. The cartoon, he said, was understood by the paper's readers to mean he was abusing the justice system "in as vile, degrading and violent a way, as the raping of a woman.” In devising his metaphor for the political antics of the country’s most powerful politician, Zapiro relied upon Zuma’s salacious reputation as an unrepentant womanizer; Zuma has fathered several children out of wedlock even when married to several other women. Zuma has given the three parties until December 31 to respond. Sunday Times reporter Khethiwe Chelemu quotes the paper’s attorney, who said the lawsuit came as a surprise “almost two years down the track.” Shapiro said Zuma and his legal team would be in a better position if the lawsuit was dropped. "I think the president has been badly advised. All he and his legal team are going to do is drag this case back into the public eye," he said, adding that the Human Rights Commission had exonerated him and the Sunday Times earlier this year, saying the issues covered by the cartoon were in the public domain. "I fully stand behind my cartoon and the views expressed in it, and I will not allow the president to intimidate me," Shapiro said. "We have had a very free print media for the past decade and we will fight for that freedom. He is going to have unwelcome attention on whether the cartoon was justified or not, and he is going to have an egg on his face over this case."

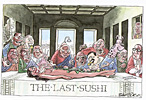

BY WAY OF UNDERSCORING HIS DETERMINATION not to be cowed, Zapiro sharpened his pen to produce yet another scandalous visual metaphor for the machinations of his country’s president, and the Mail & Guardian published it on December 23. (In South Africa, as in many other parts of the world, editorial cartoonists typically do work for more than one newspaper.) In this effort, Zapiro satisfies a long held desire to lambast the collaboration of corrupt politicians and business people. He had been searching for an appropriate image to use when a friend mentioned Leonardo da Vinci’s masterpiece, “The Last Supper.” The image seemed to mesh with the gustatory indulgences of the holidays, providing a suitable cartoon finale for the season and the year. Zapiro admitted that the final drawing presents more of an Easter image, but, he added, “I’ve been wanting to do a sushi theme for a while and that jumped into my head." The

cartoon depicts a naked woman supine on a banquet table, her body serving as a

platter for a sushi feast around which are gathered an assortment of

politicians and businessmen, from Zuma (with the shower spigot still sprouting

from his skull) to his entrepreneurial nephew. Said Zapiro: “The cartoon speaks about excess and decadence and people who have been reaching unashamedly for that. Even when confronted, they're not embarrassed.” To South Africans, the sushi platter looks startlingly familiar: she’s South Africa's self-styled "Paris Hilton," Khanyi Mbau, who pulled her own sushi stunt shortly after Kunene's. "In a way she's only there for excess but she's not a big player like any of the others are [in terms of] corruption. She's just a lightweight," said the cartoonist. The other personages in the cartoon are similarly recognizable to newspaper readers in South Africa. The figures were carefully chosen from a longer list in consultation with M&G editor Nic Dawes, who explained: "We talked and we cut out people who were not caught, were mild or were not in the news this year." Whether Zuma has taken umbrage at this depiction is not yet known hereabouts. The cartoon was published just eight days before the victims of his December 10 filing are supposed to respond. "I'm feeling confident about the court case,” Zapiro said, “—especially if this goes far and becomes an issue that is debated at the Constitutional Court and so on. I think it would be crucial publicity for freedom of expression and an important win.”. But he told reporter Verashni Pillay of the Mail & Guardian that he felt less confident about general freedom of expression in the country, with the latest threats to media freedom by government. Media and legal experts have been surprised at the two-year delay in Zuma’s reaction to the rape of Lady Justice cartoon. There have been a number of legal actions started by Zuma against Zapiro but none taken so far. Said Zapiro: “For the past 15 or 20 years I've been able to do what I've wanted to do with the help of editors. But obviously I'm not confident in freedom of expression right now. And there are clearly moves from powerful people to curb that."

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, comicsdc.blogspot.com and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

Quotes and Mots “Nobody has the right not to be offended. When I make a joke about a starving African or Stephen Hawking, that joke’s on me. Clearly, I’m the idiot there.”—Ricky Gervais (quoted in Entertainment Weekly) “Diplomacy is the art of saying ‘nice doggie’ until you can find a rock.”—Will Rogers “The Ellen DeGeneres Show is the generous show—the host keeps on giving, even after she’s handed out all the prizes.”—Ken Tucker (Entertainment Weekly, December 17) “Impatience is indispensable to getting reform started; patience is essential to seeing its promise fulfilled.”—E.J. Dionne

THE MEANING OF LIFE ITSELF Because It’s Christmas When We Ponder Such Things (A Reprise from Opus 204) One spring day at a college long ago when I’d taken on all the beer I was allowed, I went to visit Mike McLaughlin. Mike was a large fellow with a robust laugh and a booming voice who, later, made a living with it by working as a disc jockey in radio. But when I knew him back on campus, I barely knew him: he was often at parties I attended, and we knew the same people. Some of them came along on that spring day, and we luxuriated in Mike’s apartment, which, as I remember it at this distant remove, was spacious. It may even have been a whole house. It was somewhat on a hillside north of the campus, and at the back, on the southern side of the house was a livingroom with a bank of windows through which we could see the campus buildings in the distance. It was a warm and gauzy day but not very noisy, and the sunlight streaming through the windows bathed the room in a yellow-amber glow, almost like a nostalgic episode in a movie. A couch in the middle of the room faced a fireplace; no fire. For a reason that now evades me entirely, I lay down on the couch in that room and fell asleep. In broad daylight. Unprecedented at that time of my young life. Who slept in the afternoon? During the short nap that ensued, I dreamt that I had written a sentence that contained the very meaning of life. Just one sentence. And a rather short one at that. The very meaning of life within it. When I awoke, I tried to remember the sentence, but, alas, I couldn’t. And so, ever since, the meaning of life as eluded me. Until just last winter. Last winter, I was thumbing through Robert Stone’s Prime Green, a memoir of his adventures in the 1960s, and as his narrative of the decade drew to a close, he told a story about William James, the noted philosopher and psychologist, brother of the novelist, Henry. William James had imbibed a potion that included nitrous oxide and had consequently fallen asleep. Some hours later, he awoke suddenly, in high elation because he had dreamt a sentence containing the very meaning of life. William James was luckier than I: he could remember the entire thing, and he promptly wrote it down. At last, I thought as I read this far through the passage, now I’ll see that sentence I dreamt lo these many years ago. (It had to be the same sentence: there couldn’t be more than one sentence containing the very meaning of life, surely.) I hastily turned the page and found it; herewith, complete in just two independent clauses:

Hoggamous, Higgamous, Man is Polygamous; Higgamous, Hoggamous, Woman Is Monogamous. There you have it. Now we all know the meaning of life, and I, after waiting, patient but distraught, all these years for a recurrence of that instant of cosmic insight, can at last rest easy. Mike McLaughlin, however, did not rest. He went from Boulder, Colorado to Washington, D.C., which is where he found a gig doing radio. And he enjoyed the comedy of Washington. He once described the nation’s capital, meaning our government, as a huge cruise ship. It comes into port once every other year to let some passengers off and to take on some new ones, and then it puts out to sea again. Most of the time, it’s completely at sea, barely conscious of the doings of the landlubbers left behind. Perfect.

***** CHRISTMAS IS ALL ABOUT THE PAST. We wrap gifts, using what’s left of last year’s wrapping paper. We put up the tree, and we then compare it to last year’s tree and the tree of the year before that, and so on—all the way back to childhood. We hang ornaments on the tree, and as we do, we remember when we bought each one and for what reason. Christmas is memories. It’s the only holiday that’s so rooted in the past. We plan meals and other events of the season according to previous holidays’ meals and events. Christmas is familiar rituals, rituals and memories of Christmases past. So Christmas is all about the past (and the presents, I admit, because Christmas is also about children). We celebrate this year’s Christmas this year, but we bring to the celebration all the things we enjoyed about Christmas as children—memories of family customs and of family members, some no longer with us. This holiday of holidays past commemorates family and through family, community, the good things about the community we’re all members of. Christmas is one of the better impulses of Christianity—and it’s a pagan impulse, connected, far back, to heathen festivals of the winter solstice. But it’s the communal spirit of the holiday that survived and endures. Will Eisner, famed as the creator of the masked crimefighter the Spirit, used to produce a story every Yuletide called “The Spirit of Christmas.” Eisner was a Jew, and when asked why he celebrated Christmas every year in his comic strip, he said he was simply taking advantage of the season’s good will to emphasize the message. “For some reason or another,” he said, “that long-elusive aspiration for human goodness, which we share in all cultures, is present during the Christmas holiday.” His recognition of the holiday was a celebration of the human community’s fundamental benevolence. We celebrate that here, too, every year, extending warm wishes and good will towards everyone for today and tomorrow, all drawn from the ever-present past.

More Mots and Quotes “Life is too short to have anything but delusional notions about yourself.”—Gene Simmons, rock star “Marriage is nature’s way of keeping us from fighting with strangers.”—Alan King “I’m not one of those comedians who think comedy is their conscience taking a day off. My conscience never takes a day off. I can justify every joke I’ve ever done.”— Ricky Gervais (quoted in Entertainment Weekly) “It’s been a decade since I lived with my parents, but I still don’t know what to call it when I go to their house. Am I going home? Am I just visiting? And when I go back to my house, am I going home—from home?”—Aaron Karo’s Ruminations.com “Calling me a free spirit is one thing, but when you say it while using air quotes, I know you’re just calling me a whore, Grandma.”—Aaron Karo again.

EDITOONERY Afflicting the Comfortable and Comforting the Afflicted THE POWER OF A CARTOON For the last

49 Christmas Eves, the Courier-Journal in Louisville, Kentucky, has

published the same cartoon by Hugh Haynie, who was a fixture on the

paper’s editorial page for nearly four decades. This relic appears in the upper

left of the accompanying visual aid; the caption reads: “Now, let’s see—have I

forgotten anyone?” The trick in achieving one of these perpetually re-appearing heartstring jerkers is to come up with something so saccharine, so appealing to the “aw shucks—ain’t it the truth” sentiment that haunts us all, that readers will tear up at first seeing it and then will want to see the cause of their tender feelings again and again, year in, year out. Steve Breen’s “Joy” cartoon to the right of Haynie’s is well within this soppy reverential tradition. But Gary Varvel, just below Haynie, follows more the custom of most editoonists at this time of year: he uses some aspect of the season to sharpen the point of his commentary on the passing contemporary scene. Ditto Pat Bagley in the cartoon at the lower right, which assails the tedious war against Christmas in the public square. In

our next exhibit, the cartooners get hazardously wicked in deploying the season

to air their opinions. At the lower right-hand corner, we have another kind of recurring image—namely, Bill Mauldin’s famed cartoon from World War II. In Mauldin’s incarnation, the original of the cartoon, he’s making fun of the cavalryman of the modern army. By the time of WWII, the army no longer used mounted troops; the army still had cavalry, but their steeds had four wheels, not four legs. The cavalryman’s affection for horseflesh, however, hung on, as we can readily see in Mauldin’s cartoon: when the cavalryman’s jeep breaks an axle, he treats the vehicle as he would have his mount of yore. He shoots it to get it out of its misery. Mauldin’s image has been used again and again, but usually, as in this case with Nate Beeler, the original comedy has receded almost to the vanishing point. All that remains here is the image of the military high command discharging a pistol into a jeep’s hood. When we know about the cavalry allusion, though, the cartoon gains impact: just as horses have disappeared from the military establishment, so, presumably, has bigotry about gays, but the high command, Beeler says, seems as sorrowful about the disappearance of homophobia as the old horseman is at killing his disabled mount.

NAUGHTY AND NICE A roundup of Yuletide crime, compiled by SPINews at Sardonika.com, where two otherwise editorial cartooners (Mike Keefe and Tim Menees) while away their idle hours in making sense of nonsense and vice versa: Pittsburgh: Giant inflatable Christmas yard figures, led by Frosty the Snowman, Santa and Snoopy, invaded a house and held their owners captive. Shouted Frosty, "We're sick of lines of cars coming by gawking at us. It's Christmas! Leave us alone!" Raleigh: A band of terrorists were nabbed turning 10-pound fruitcakes laced with brandy into IEDs. Dallas: The real Santa escaped injury when he was shot at while up on a housetop. A gun-wielding neighbor—they all wield guns here—mistook him for "The Blind Sheik" who plotted the first World Trade Center bombing. Tuscaloosa: Two men were arrested for selling mistletoe, banned by the city "for leading to unmarried sex." Los Angeles: The Little Drummer Boy bashed up his drum then trashed a hotel room. As he admitted to security, "I was channeling Keith Moon." The North Pole: Six of Santa's elves were caught smuggling in Chinese toys laced with lead, arsenic and PCBs. Denver: Two department store Santas tore up a LoDo (Lower Downtown Denver) bar in a late-night brawl. "They have a history of bad blood," explained a Denver cop, "ever since one got a lap dance from the other's girlfriend." Chicago: Three unemployed elves were busted for hawking one-square-inch pieces of Jesus' swaddling clothes and "bits of the manger" on eBay. Washington, D.C.: Neighborhood carolers inadvertently started a "flash mob" that smashed downtown store windows, overturned cars and nearly brought down the lame-duck session of Congress.

THE FROTH ESTATE The Alleged News Institution As of December 9, the Associated Press reported that the number of journalists in jail worldwide has reached 145, the highest in fourteen years. China and Iran lead the ranks of the jailors, with 34 behind bars in each country; then comes Eritrea with 17, Myanmar with 13, and Uzbekistan with 6.

THE ACTUAL SEX CRIME of which Julian Assange is accused is finally coming to light: he is accused by two women of having condomless sex with them. The encounters were initially consensual, reported the New York Times, “but become nonconsensual when he persisted in having unprotected sex with them in defiance of their insistence that he use a condom.” Assange met both women while they were all attending a lecture last August. One of the women, a 31-year-old, was one of the organizers of the event and offered to host Assange at her apartment, according to the Associated Press; the other women, younger, was in the audience at the event. Assange had sex with them individually on different days, beginning with the older of the two. The older woman “accused Assange of pinning her down and refusing to use a condom. The second says Assange had sex with her without a condom while she was asleep.” (Did she wake up? When?) Neither woman, at the time of their separate adventures with the Wikileaks maestro, knew he was also adventuring with the other. Both women seemingly wanted to continue their relationship with Assange. Then the younger of the two, who wanted to get in touch with Assange, went to the older woman (known to her as an organizer of the event at which she met Assange, who was apparently one of the event’s speakers) to find out how to get in touch with him. That’s when each woman found out about Assange’s relationship with the other. When the two women “realized that he had had sex with both of them within a week,” they went to the police about it. Initially, their purpose was to seek advice, but when a policewoman heard their stories, she “decided there was reason to suspect they were victims of sex crimes and handed the case over to a prosecutor,” who at first dropped the rape charges, “and it would most likely have ended there had it not been for Claes Borgstrom,” Sweden’s former ombudsman for gender equity, who successfully appealed the initial decision and “got court approval for a request to interrogate Assange on suspicion of rape, sexual molestation and unlawful coercion.” It all sounds somewhat wee-wee’d up to me. Apparently, saith John F. Burns and Ravi Somalya at the New York Times, the women were “willing to continue their friendships with Assange after his alleged sexual misbehavior until they discovered by talking to each other that they had both been sexually involved with him.” Some of Assange’s supporters allege that the CIA or some other U.S. agency has fomented a plot against Assange, but the women deny any such involvement, and it surely looks to me like a simple case of two women who feel “wronged” seeking to get even somehow and being abetted by a retired gender equity crusader. Meanwhile, Assange, feeling rather penniless while in the toils of the legal system, has struck deals with Alfred A. Knopf in the U.S. and U.K. publisher Canongate to write his autobiography. The AP account quotes Assange as being “forced into penning the autobiography to keep his organization from going under.”

FOX NEWS is biased. Its news coverage is tweaked in favor of a conservative perspective. We all know that, but now concrete evidence has surfaced that indicates dark machinations below even the obviously slanted surface. As reported in the Washington Post, Media Matters for American, a liberal media-watchdog cabal, has unearthed an internal e-mail from Bill Sammon, Fox News’ Washington bureau chief, that urges Fox journalists to “refrain from asserting that the planet has warmed (or cooled) in any given period without IMMEDIATELY pointing out that such theories are based upon data that critics have called into question,” thereby creating, saith Media Matters, “a false impression of the climate issue by giving a ‘fringe’ minority of global-warming skeptics equal weight with those who have concluded the planet is growing warmer. The overwhelming, vast majority of scientists who have studied climate change accept the trend as a fact.”

MUCH FUSSING ENSUED in the wake of a report that 23% of recent high school graduates seeking to enlist in the Army fail its entrance exams, which, in the Army, have lower passing threshholds than the other services. But the alarm might have registered at lower decibels had the reporters acknowledged that in the “normal distribution” of the Bell Curve, 16% of any group will perform lower than average. Moreover, looking at a map that shows where the highest numbers of failures occur, we see that a lot of the failing applicants are in the South, notorious for poor educational systems.

NBM AND THE EUROPEAN CONNECTION PART TWO: NURTURING THE GRAPHIC NOVEL When NBM Publishing was founded in 1976, almost no one on this side of the tumultuous Atlantic had heard the term “graphic novel.” We may not have known the term, but many of us had heard about European comics—which we thought of, then, as being chiefly French—and some of us had even seen evidence of their lavish use of color and high quality reproduction values in “comic books” (which weren’t called “comic books” over there; more of that in a trice). The term “graphic novel” had been concocted several years earlier. In the fall of 1967, Bill Spicer changed the name of his magazine, Fantasy Illustrated, to Graphic Story Magazine, with the approval of one of his columnists, Richard Kyle, whose column was “Graphic Story Review,” an echo of Kyle’s earlier coinage, “graphic novel,” which he’d introduced in November 1964 in his Wonderworld contribution to K-A No. 2. Spicer’s magazine, with a greater circulation than the apa Kyle had been writing for, promoted the use of the term, later picked up by Will Eisner and others to distinguish “long form comic books” from the traditional newsstand four-color pulps. But Eisner’s watershed A Contract with God was still two years in the future in 1976. In 1976, we were still three years away from what was arguably the first all-out attempt by a major mainstream American comics publisher to match the Europeans, Warriors of the Shadow Realm, a three-issue series of elfin sorcery adventures in the Tolkien mode produced in 1979 by Marvel in the European manner. The visuals—the characters and ambiance—are a stunning evocation of gnarly Arthur Rackham, designed by John Buscema, noted throughout fandom as a superhero artist cum Conan renderer but here, outdoing himself in both conception and execution. Buscema’s pencils were inked by Rudy Nebres but only the foreground figures. Those were then colored and backgrounds fully painted by Peter Ledger. Some linear clarifications, methinks, were added to the backgrounds for smaller details. The printing, unfortunately, sometimes produced off-register pictures, but for the most part, the whole production was, for its time, extraordinary. It would take years before anyone attempted anything as ambitious, and Warriors remains, to this day, a conspicuous if almost forgotten stand-out comic book in the pantheon of four-color fiction. Fans, forever envious of the art and reproduction values in European comics, had been clamoring for a similar effort on this side of the Atlantic for several years, and this production took a giant leap in the right direction. It should have been a watershed publication, setting the pace for all future American comic books, but, alas, it proved instead to be too far ahead of its time. In 1976, Terry Nantier was a 19-year-old student at the Newhouse School of Communications division of Syracuse University and was about to take a step into the future of American comics, ahead of their time or not. He knew what the Europeans were up to because he’d spent most of his teenage years in Paris lusting after what the French called “albums” of comics. Nantier reached back across the Atlantic and recruited a couple of silent partners, Beall and Minoustchine, forming Flying Buttress Publications, a strange name unless you’ve spent a certain amount of time in Paris where the most famous flying buttresses of all are propping up the weighty walls of Notre Dame on the Isle de le Citie. “It sounded neat at the time,” the NBM website murmurs, “—especially with the slogan ‘the support of a new medium.’” Together Nantier and his partners published the first of the modern graphic novels, Racket Rumba, a 50-page send-up of the noir detective genre with a bulb-nosed gumshoe by the French cartoonist, Loro. The interior pages were black-and-white, but the cover, featuring the large nose and the daring plunge of a would-be heroine’s decolletage, was in color. Nantier called the book a “graphic album.” The year 1976 was evidently a portentous year for comics: that summer, Gary Groth and Michael Catron took over The Nostalgia Journal with No. 27, christened it The New Nostalgia Journal, and soon thereafter, re-title the magazine entirely, launching The Comics Journal in January 1977 with No. 32, poaching The Nostalgia Journal’s numbering sequence. The first Groth-Catron issue featured Groth’s extensive and thoroughly documented attack on the business practices and so-called ethics of The Buyer’s Guide’s publisher, Alan Light. But after attracting attention with this sensation, the Journal soon turned to what would become its forte—intelligent and demanding criticism of comics as an artform, which it pursues still with a persistence that established comics criticism as a distinct and honorable enterprise and may well have resulted in improvements in the medium itself. Nantier, however, was interested in establishing a beachhead, not storming the citadel. “I started this company with the vision that graphic novels were what was missing here,” he said in an interview with Herve St-Louis at comicbookbin.com. “At the time, comic strips were getting increasingly cut in papers, and comic books were getting cut out of newsstands. Comic book stores were barely starting. In Paris graphic novels were responsible for an explosion in creativity, popularity and, importantly, respectability. I thought ‘Why don't we have this in the U.S.?’ So I started NBM (then Flying Buttress) principally bringing over European graphic novels to show the way really, not with the intention of just being a Euro-comics publisher. We were the first to publish Bilal here. [The follow-up to Racket Rumba was Enki Bilal’s The Call of the Stars. Then in 1985], we wowed the world with The Mercenary, the first fully painted series of graphic novels [by Spaniard Vicente Segrelles].” The full-painting technique, however admirable in principle, risks falling short in practice of the kind of visual clarity comics usually convey whenever people are depicted at a great distance: without delineating outlines, the figures must be defined entirely by shades of color, and the smaller (the more distant) the visual elements of the picture, the less clearly do colors alone differentiate identifying forms. Segrelles seemed aware of this: people are almost always shown at mid-range or close-up; he saved his long-shots for brooding mountain ranges and glowering canyons. The result is a handsome visual feast. Segrelles hasn't the stylistic panache of either Boris or Frazetta, the undisputed masters of this sort of thing, but the moody vistas of this fantasy land are beautifully rendered, and the artist's verbal restraint gives his paintings additional narrative power: we must dwell upon them to follow the story. Segrelles’ protagonist is a cutout of the heroic mold, virtually without personality, but Segrelles knows his storytelling: he blends word and picture to good effect, letting his paintings tell the story with as little accompanying persiflage as possible. The Mercenary, we see at nbmpublishing.com/history, sold over 50,000 copies.

EARLIER, in 1984, NBM paralleled Fantagraphics again in pioneering the reprinting of classic American newspaper comic strips. That year, Fantagraphics began a complete reprinting of E.C. Segar’s “Popeye” from Thimble Theatre (as “Popeye” is formally entitled) with the Sunday strip for March 2, 1930; paperback volumes of the dailies started appearing in 1987 with the release for July 20, 1928, and continued until the entire Popeye oeuvre of Segar’s comedic genius is on display in 11 volumes. Fantagraphics is now re-issuing the work in larger format hardcover volumes. At virtually the same publishing moment in 1984, NBM went to hardcover at the start, beginning its 12-volume complete reprinting of Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates and continued in the genre in 1987 with the first of 18 hardcover volumes of Roy Crane’s classic Wash Tubbs (“Captain Easy”). The same year, Fantagraphics launched its paperback Prince Valiant project, reprinting Hal Foster’s masterwork in color (and is now re-vitalizing the project, using better source material in hardcover volumes). In 1993, NBM followed with 18 hardcover volumes reprinting Tarzan from Foster’s 1931 pages through Burne Hogarth’s, ending in 1950. Together, the two publishers demonstrated that a market exists for extensive reprint projects of vintage comic strips, a proposition that IDW is presently exploring and Classic Comics Press ditto, with On Stage, The Heart of Juliet Jones and Dondi. In 1977, the Hyperion Library of Classic American Comic Strips had debuted. The direct product of Bill Blackbeard’s archival clipping and cataloguing of early newspaper strips, the series included a couple dozen volumes, beginning, probably, with such historic strips as The Family Upstairs (where Krazy Kat debuted), A. Mutt (which became Mutt and Jeff), Bobby Thatcher (an early adventure attempt), Bringing Up Father, and Happy Hooligan. Hyperion produced a couple titles in a limited-run hardcover editions for library sales, but most of the series was in paperback. And Hyperion—alas, after a stunning opening burst of publication in this line—collapsed and went out of business. Nantier is justifiably proud of being the first to show that library-worthy expensive hardcover complete reprints are an economically viable enterprise, he told St-Louis, continuing: “Now we've relaunched ourselves into this classic strip collecting with vintage greats presented in our Forever Nuts collection with Mutt & Jeff, Happy Hooligan and Bringing Up Father. We have others up our sleeve but are not looking to flood the market. NBM has always been about quality and each book being worth publishing, not quantity.” He’s also proud of the design of these reprise volumes: “I think they're really keepsakes, lovingly designed. Forever Nuts has a strong design element but, as we've always done, not bringing attention to itself, just being a good platform to show off the star—the classic comic being collected. Our design on all our books follows that aesthetic. We're not designing magazine/periodicals/comic books. We're designing books. That means something more eternal that must have room to breathe. Not every page needs to have some full bleed art. Blank pages are okay. Less is more. You're doing a platform for your artist, not trying to invade his work with excessive splash.”

IN 1986, NBM BEGAN constructing a platform for Hugo Pratt with the first of 8 volumes of Corto Maltese graphic novels, The Brazillian Eagle. At the time, Pratt’s work was almost unknown hereabouts; some knew his name, but not his work. Born in 1927, Pratt spent his childhood in Venice; after World War II started, his father, a professional soldier in the Italian army, died a British prisoner of war in Mussolini’s Ethiopia, and Pratt and his mother were also imprisoned. After the War, Pratt found himself in Venice, where, at the age of 18, he joined a group of other Italian cartoonists to launch a magazine of adventure comics. In 1949, Pratt was in Argentina, continuing to draw comics written by others for comics magazines. For a year ending in the summer of 1960, he was in London, drawing war comics written by others for Fleetway Publications. Pratt went back to Argentina for a couple years, finally returning to Italy in 1962, when he began adapting classics of adventure literature, Treasure Island and Kidnapped for instance, for a children’s comics magazine. In 1967, Pratt met Florenzo Ivaldi and the two created a comics magazine named after Pratt’s Argentine creation, Sgt. Kirk. In the first issue, Pratt began serialization of the adventures of his most famous creation, Corto Maltese. The character’s personal history is recounted in Wikipedia. An enigmatic and laconic sea-faring soldier of fortune wandering the South Seas (when he first appears) during the first two decades of the 20th century, Corto Maltese is “a rogue with a heart of gold, tolerant and sympathetic to the underdog. Born in Valletta on July 10, 1887, he is a son of a British sailor from Cornwall and a gypsy Andalusan witch and prostitute known as La Nina de Gibraltar. As a boy growing up in the Jewish quarter of Cordoba, Maltese discovered that he had no fate line in his palm so he carved his own with a razor, determining that his fate was his to choose. ... The character embodies the author’s skepticism of national, ideological and religious assertions. Corto befriends people from all walks of life,” all stations, all classes. When

the reader of Pratt’s comics first encounters Corto Maltese in 1967's Sgt.

Kirk magazine, the character has been cast adrift at sea, bound, and

spread-eagled as if crucified by the bindings, to a raft shaped like a Maltese

cross. Pratt, as everyone probably remembers, was at the time of his greatest fame the most prominent of the European practitioners of the chiaroscuro technique of rendering that was invented by Noel Sickles and made famous by Milton Caniff. With his relatively simple outline style (however inventively it’s shadowed), Pratt evokes Sickles more than Caniff (although at one time it was impossible to tell the latter two apart). The technique is well suited to Corto Maltese’s earliest adventures, which took place in tropical climes where the blazing sun burned imagery out, leaving only the shadow side to suggest what was before our eyes. But Pratt isn’t the storyteller that either of his inspirations are. Typically, Pratt’s Corto Maltese stories contain a whopping lot of conversation, which Pratt depicts with a series of head-shots—one talking head per panel, sometimes for several pages in succession and with very little variation in camera distance or angle. This monotonous progression is punctuated every so often with scenes—spurts—of violent action, during which the drone of the character’s talk ceases almost entirely in order to let full-figure drawings tell the story. Pratt differs most from Sickles and Caniff in his willingness to subject his readers to a parade of talking heads without varying camera distance or angle. While that produces all the visual variety of a wallpaper pattern—the kind of dull sameness that Sickles and Caniff worked hard to avoid—Pratt makes the monotony work for him. As we read from panel to panel, from one talking head to the next, we fall into step with Pratt’s pacing. Slow, deliberate—monotonous. I think of one of those antique ceiling fans making slow unvarying circles overhead in some exotic tropical barroom somewhere. In the Caribbean, say, or the South Seas—just where Corto Maltese happens to have spent some of his first published adventures. Pratt’s pacing invokes the image of the fan’s slow revolving, and both suggest that life must be lived slower in places where the tropical sun beats down long and hot every day. But life is also sometimes violent. Even in the tropics. And violence disrupts the easy-going routine in the tropics—disrupts it violently, just as Pratt’s action sequences burst in and change the pace and tenor of his strip, often with compunctionless murder or meaningless mayhem. The fascination in Pratt’s Corto Maltese stories lies in such atmospherics as pacing. But it is fostered, too, by the exotic island setting—the Caribbean, for instance, vaguely magical, enchanted, voodoo-ridden perhaps. And Pratt manages to transfer those atmospherics to wherever he sends Corto Maltese next. Pratt capitalizes on this exoticism by dangling before us some of the most interesting names in comics—Corto Maltese (derived, possibly, saith Wikipedia, from the Venetian Corte Maltese, Courtyard of the Maltese), Goldmouth, Commander Rasputin, Jesus-Mary (pronounced “hay-sus” in this region, remember), Barracuda-Jack-of-all-Trades, and (this one’s a stunner) Ambiguity de Poincy. These are all slightly tattered, once-upon-a-time people—people with fragmentary histories, feverish dream-like memories, all of which hang threateningly in the background, a palpable if unspecified and mysterious past. Pratt isn’t the storyteller Sickles was or Caniff. He’s a different kind of storyteller, and he achieves his unique effect by his own means, however much his graphic style on the surface seems to mimic the two American cartoonists.

WITH A PUBLICATION SCHEDULE that included both graphic novels using European material and hardcover reprints of classic American newspaper comic strips, NBM added to its agenda some books created expressly for its imprint. Among the first, a series of true crime books by Rick Geary, “A Treasury of Victorian Murder Mysteries,” launched in 1987. Geary has apparently exhausted the 19th century in about nine books, and the series has now morphed into “A Treasury of 20th Century Murder.” The most recent of these is The Terrible Axe-man of New Orleans (80 6x9-inch pages in b/w; hardcover, $15.95). Set in the Big Easy right after World War I, Geary’s tale traces, murder by murder, a series of slaughters of Italian grocers, who are killed in their beds in the middle of the night by someone who enters the premises by breaking a panel out of a door and then, appropriating an axe found in the house, goes right for the heads of his victims, leaving blood splattered all over the place for the police to cogitate over when they discover the crime. Among the puzzles: the hole in the door created by knocking out a panel is always too small for any adult-sized person to enter. The terrible axe-murderer is never found, but, as usual with his painstaking research, Geary offers some speculations at the end of the book. Apart from the gory fascination of the tale itself, we delight, as always, in Geary’s treatment of his material. His flat, emotionless prose narrative captions are accompanied by his haunting drawings, copiously shaded with parallel lines and hachuring, in which victims (before their deaths) and neighbors and police are often depicted staring into the camera—as if in a police line-up, unspeaking witnesses to terror, frozen in dread of some sinister machination lurking in their future.

Geary deftly creates not only the horrifying atmospherics of the murders but the ambiance of the otherwise jumping jazz scene of New Orleans. It’s always a pleasure to see Geary in action.

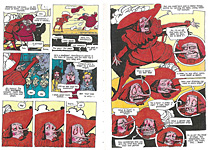

DESPITE THE SUCCESS OF MOST OF ITS TITLES, NBM, like Fantagraphics, resorted in 1991 to publishing erotic graphic novels as a way of enhancing financial stability, there being, as everyone knows, an insatiable appetite in America for sex and its numerous innuendoes. NBM’s imprint is dubbed Eurotica, with indigenous material in a subset called Amerotica. Said Nantier: “We started that with Crepax’s Story of O which we just brought back out. While this line does help us financially, we've always managed it with the view that erotic comics are a perfectly legitimate form of expression: they need not be some horrid sausage factory. We've had some very intelligent comics in this line, even if hardcore, they've had something to say, but most of all they've had very beautiful art. And that works well to this day where adult slop exists by the silo-fulls on the internet. That's how we differentiate ourselves.” Herve St-Louis asked what it might take for mainstream media to cover erotic comics adequately, to which Nantier quipped: “Balls. I'm serious! Most media cave in to the puritan pressures.” But not here at the Rancid Raves Intergalactic Hideout. Here, unafraid and dauntless, we’ll write about anything and revel in it. Even the erotic fantasies of Guido Crepax. Crepax was born in 1933 and died in 2003; in between he began carving his niche in the history of comics with the publication in 1965 of the Valentina series, starring the first of Crepax’s deliciously “innocent” young women who achieve a kind of self-knowledge through erotic adventure. In subsequent works, Crepax returns to themes involving victimized girls, sadomasochism and violence. It is not surprising, as one website notes, “that Crepax illustrated classic erotic stories like De Sade's Justine, Pauline Réage's Histoire d'O and Sacher-Masoch's Venus in Furs.” Most of the physical appearance of Crepax’s heroines was inspired by American actress Louise Brooks, whom the cartoonist reportedly adored (for more about Brooks, see Opus 177). At jahsonic.com, Crepax is quoted on his forte: “So if I have drawn whips, chains, bonds of every kind—even if I have reproduced in my pictures the most audacious bold erotic perversions—I in fact hate violence and lack of respect towards oneself and others, and all forms of excess, the extraordinary things that my poor young girls in love undergo. Valentina, Madame O [and all the rest] have nothing to do with the treatises on sexual psychopathology. They are only visionary exercises, imaginary madness transferred onto paper, deliriums, desires ruled by a purely cerebral mechanism. ... What interests me more than anything else is that the game never becomes obscene, that it is never trapped by vulgarity.” This "weaver of innocent plots" is indeed, as Frediani describes Crepax, "a hunter of butterflies.” Crepax would agree, pointing out: "From the point of view of eroticism, it's the atmosphere, the situation, which gives the scene its eroticism." All his notorious heroines are “the victims of the most barbaric treatment always amidst splendid and baroque backgrounds. Pursued through labyrinthian perils, raped, whipped, and entangled in all manner of bizarre Heath-Robinson-like torture machines, they always emerge, however, Phoenix-like from their ordeals.” The authorship of the original 1954 prose novel Story of O was for years a matter of manic speculation, but it was revealed in The New Yorker in 1994 that “Pauline Reage” was the pen name adopted by French author Anne Desclos when the book was published. The novel was based upon “love letters” she wrote to her lover, Jean Paulhan, who, fascinated by Marquis de Sade’s writings, told Desclos that he didn’t believe a woman could write that sort of material. Desclos rose to the challenge. Wikipedia sums up the novel’s action: “Story of O is a tale of female submission about a beautiful Parisian fashion photographer, O, who is blindfolded, chained, whipped, branded, pierced, made to wear a mask and taught to be constantly available for oral, vaginal and anal intercourse. Despite her harsh treatment, O grants permission beforehand for everything that occurs and her permission is consistently sought.” O’s lover takes her to a chateau where she is “trained” to be submissive through various exercises—bondage, humiliation, sexual acts with multiple partners, sodomy, and so on. She later becomes the lover of another man, and in the story’s final scene, she appears as a slave, “nude but for an owl-like mask, before a large party of guests who treat her solely as an object.” Viewed as a tale about the ultimate objectification of a woman, “the heroine has the shortest possible name, consisting solely of the letter O. Although this is in fact a shortening of the name Odile, it could also stand for ‘object’ or ‘orifice,’ an O being a symbolic representation of any ‘hole.’ The novel was strongly criticized by many feminists, who felt it glorified the abuse of women.” Mostly, I agree with the feminists. Or, at least, I find the story and Crepax’s depiction of O’s fate degrading to both women and to notions of romance and love. For me, at least, the book is not erotic—that is, intended to arouse sexual desire but in a romantic sense, love and sex; instead, the book borders on pornographic—which neglects romance and love in its drive to excite lascivious feelings. Except for groans and moans, O never speaks: she is therefore completely dehumanized. Her nudity is sometimes appealing; but the more submissive she becomes, the more she is merely naked. For many—including, no doubt, Crepax—the issue is not sex but freedom. Oddly—for most of us—submission means liberty for O. The NBM press release accompanying the book asserts that when O is “gloriously shown off” at the climactic moment, “stark naked but for an owl’s mask,” it is “her moment of glory, not, ironically, that of her lover. That she would have the courage to exhibit herself so shamelessly, on a leash, completely liberated from the constraints of society is, in fact, an act of defiance to the social suppression of sexuality.” As another commentator put it: she was ennobled; she found dignity. Believing that requires a leap of logic that I’m not quite capable of, but I can understand the intellectual gyration that yields that conviction. For

me, the interest of the NBM book (176 8.5x11-inch pages, b/w; hardcover,

$24.95) lies almost entirely in Crepax’s storytelling devices. Again quoting

the NBM press release: “In his distinctive multi-paneled breakdown of pages

which emphasizes the voyeuristic experience, the smaller panels almost making

one feel as if peeping through a keyhole, Crepax shows O’s willful descent into

complete submission.” Tiny panels of Crepax’s fragile, spidery linework focus

on telling visual details in O’s “training.” For four pages, for example, she

is whipped, the panels of all sizes start by showing her at full length and

finish by showing the aggregation of body parts visited by the lash. More to my taste is First Time (112 8.5x11 pages, b/w; hardcover, $19.95), a collection of ten short stories, each detailing in explicit but exquisite drawings the first sexual experiences of an assortment of women, all written by Sibylline, a woman administrator at Delcourt, a major French comics publisher. “The idea,” she explains in the book’s afterword, “was to provide a means for those who perhaps wanted to draw sex without daring to ask to do so. But we also wanted for it to be something more than a succession of pornographic images. We wanted to show, but we also wanted to tell. Sex is foremost an exchange, an ultimate moment of self-abandon where one must know how to set aside prudishness and anxieties. We have sex because we love it, we discover ourselves, and we teach ourselves. I wanted to tell stories that are reminders that sex is beautiful and to say that what are excesses for some are but a tender normalness for others.” Each of the stories is written from the feminine perspective. One woman tells of her first time with a man she comes to love. Another fantasizes about doing it for the first time with a waiter she lusts for. Two normally heterosexual girls get it on. A couple find a woman on the internet, who comes to their apartment and makes love to the wife, then the husband joins in. Another girl buys herself a sex toy and uses it for the first time. Each

story is drawn by a different artist, most of them Europeans; four give only

their first names—Alfred, Capucine, Vince, Rica; the others are more

forthcoming—Jerome d’Aviau, Virginie Augustin, Olivier Vatine, Cyril Pedrosa,

Dominique Bertail, and Dave McKean. Some styles are cartoony; others,

realistic. All, however, are splendidly achieved—graceful undulating linework,

unabashed nakedness, form and function in persuasive detail. But despite the

explicit visuals, romance—lust as well as affection—makes all the encounters

thoroughly humane, tender and endearing. NBM also published the complete oeuvre of Reed Waller and Kate Worley, seven volumes of Omaha the Cat Dancer, books over which the puritan among us raised such a ruckus years ago, plus several of Milo Manara’s superior efforts, a title or two from Azpiri, a series of highly comedic one-page sexual adventures in an attractive cartoony style, all under the series title Grin and Bear It, and at least half a catalogue of other erotic enterprises. But my favorites of the lot are those by Ignacio Noe, who draws the best erotic comics on the planet. His pictures are not only breathtakingly fleshy and seductive, but his stories are invariably outrageously funny. In one of the latest, Aldana (48 8.5x11-inch pages, full unabashed color; paperback, $11.95), we have page after page of shining testimony in lascivious support of my otherwise dubious contention that Noe is the best at what he does. The story is a simple roundelay, which, with its repetitive pattern, supplies ample occasion for Noe to perform his transcendent visual debaucheries. Arthur is a movie producer whose grandmother has disinherited him so he can’t produce the movie he wants to produce. Aldana is his voluptuous and sexually insatiable maid, who doesn’t desert Arthur no matter what because she loves him with an undying lascivious passion. Every chorus begins with Aldana throwing her ample, soft and pillowy bosom and the rest of her curvaceous epidermis at Arthur in her attempt to console him for his various failures. Just as Arthur is about to satisfy Aldana, a doorbell or telephone rings, and he must abandon the sumptuous Aldana in order to attend to some new money-raising scheme or pacify a representative of his grandmother—all of which involve his energetically shtupping one or more of a parade of generously endowed young women. Meanwhile, Aldana gets out of the house to run errands for him, and she inevitably runs out of gas or forgets her purse or is otherwise in need of a service or product for which she pays with her admirable body, the supplier of the service or product inevitably being a horny male. When she returns to Arthur’s digs, she finds him exhausted by his romp in the figurative hay, too spent to resume his attentions to her. The next day, the roundelay resumes with Aldana again offering herself to the despondent Arthur, and they are, again, interrupted. Nothing

particularly inventive disturbs this pattern. What is supremely inventive is

Noe’s graphic imagination, which yields scores of pictures of the most athletic

frenetic sex in comics. Erotic comics are about sex—sex and romantic love—and

barenekkidwimmin are the usual conveyances of it in erotic comics. But Noe

takes the genre nearly all the way into pornography, from tits and ass to cocks

and twats, puds and pudenda—unbridled sex for the sake of sex, romance being an

incidental if not altogether neglected element. And he’s a champion at drawing

all of it, every jot and tittle (so to speak). Aldana may love Arthur, but she

loves sex more. Motive and theme here, however, are beside the point: the point

is Noe’s stunning drawing, his surpassing command of anatomy, his bold and

authoritative line, his comedic invention in the midst of superheated throbbing

and swollen sex scenes that depict sucking and fucking in copious, panting,

sweating, spurting, juicy explicit detail. Noe draws beautiful, succulent

women, giving their faces a range of expressions. Ditto their soft voluptuous

bodies. And his male characters are likewise masterfully depicted. NBM offers three other Noe titles, all of which follow the kind of template Aldana so carnally exemplifies. In two volumes of The Piano Tuner, the title character calls upon house after house where the piano needs tuning; invariably, it’s the mistress of the house who craves a tuning, and the indefatigable tuner unflinchingly does his job every time. In The Pin-up Artist, the most recent Noe import, an aging pin-up artist, famous for his Elvgren-like paintings, reminisces about the moments of his inspiration for each of several of his coy and demure but leggy and bosomy painted ladies, and it turns out that the “original” pose was that at the climax of a episode of nearly depraved (but certainly enthusiastic) wanton sex, which left the model in mere tatters of her raiment. The artist clothed his model in his imagination and produced the tasteful pin-ups of his paintings. Nantier says Eurotica is about 40% of NBM’S sales and publishing program, and the remaining 60% is highly varied. Said he: “From the start our choices for our catalog have been to appeal to as wide an audience as possible, not just a certain group of fans. Even in the late seventies I was already actively pursuing general distribution in bookstores. Obviously it was very tough, but I learned a lot and ended up very ahead of the game compared to the rest of the comics industry in dealing with that market. By the time everyone else wanted to enter it and graphic novels were becoming a real factor in comics, we had been there, done that and were starting to get reviews in Publishers Weekly and newspapers, helping to establish comics as a respectable art form. We were also the first to distribute Dark Horse into that market, by the way.”

AMONG NBM’S RECENT OFFERINGS is A Home for Mr. Easter (200 6x8-inch pages, b/w; paperback, $13.99) by Booke A. Allen, a feel-good tale about an overweight perhaps a little retarded girl named Tesana, who, bullied by her classmates, invents a unicorn friend and, later, takes into her care a rabbit, which she is convinced is the Easter Bunny. Tesana decides to return Mr. Easter to his “home,” wherever that may be, and for the next 150 pages, she makes a heroic attempt to find it, beset by numerous threatening situations—a greedy pet store operator who, persuaded that Mr. Easter is magic, wants to keep him; a bunch of college students who use rabbits as experimental animals; protestors against lab animals; and a con-man magician who may have “owned” Mr. Easter in some previous enterprise. By the end of the book, after numerous hazardous adventures, Tesana finds a home for Mr. Easter—her own home with her vaguely uncomprehending mother, where Mr. Easter, freshly hatched out of a lately acquired egg, promises to live with her ever after, happily. Allen applies a splashy brush to good effect, giving the headlong pace of the narrative a harried appearance; see our Gallery below for a sample. In another graphic novel, Salvatore (104 6x9-inch pages, color; paperback, $14.99), we meet Nicolas De Crecy’s eponymous protagonist, a crack dog mechanic, who is repairing automobiles as a way of stealing the parts he needs to build his own specialized all-purpose vehicle that can cross bodies of water as well as expanses of land. Love-smitten Salvatore wants to get to South America where he can rendezvous with the wire-haired terrier of his dreams, Julie. He has almost finished constructing this locomotive contraption as the novel opens, but he needs one more elusive part, and much of the first two “parts” of the final work (which is to be completed, we assume, in the next volume when it is published) is devoted to his search for the missing adaptor. Into this proposition, De Crecy introduces a major albeit subordinated thread of narrative about Amandine, a nearly blind pig, whose car Salvatore repairs and who then gives birth to a dozen piglets, one of whom, Frank, the runt, gets lost in the sewers of Paris. Thereafter, whenever Amandine shows up, she’s looking for Frank. Of minor significance is another thread about an amorous cow who owns, or did own—once upon a time—a vehicle that is possibly the final resting place of the last adaptor that Salvatore needs. Eventually, we suppose, these seemingly unrelated strands will be woven neatly together in the novel’s conclusion (forthcoming). Salvatore is essentially a love story, complicated by the everyday struggles we all endure as we find ways to compromise between morality and idealism and enriched by a strain of satire. De Crecy takes digs at wild-eyed liberal critics of our consumerist society and at various avant garde trends in art, but the fundamental mechanism of his story, Salvatore’s mission to built a vehicle that can take him to Julie, is in the protagonist’s confrontation with ordinary hurdles that he overcomes with outlandish solutions: to seduce the heifer with the adaptor, he needs an inflatable bull costume. Why not? De Crecy’s wispy linework compliments the wistful tale with its own graphic eccentricities, some of which are on display in the Gallery below. And then we have Greg Houston, back again after the triumph of his outlandish blaxploitation expose, Vatican Hustle (see Opus 253), with Elephant Man (80 6x9-inch pages, b/w; paperback, $9.99), a send-up of superhero comics starring Jon Merrick, the famed deformity of the last century, who, in his effort to save Baltimore (Houston’s home town, by the way) from the Priest, the Rabbi and the Duck (a trio of unlikely comrades that have become fused together into a single crime wave with three heads through the malfunction of a fiendish scientific device), is undermined at every opportunity by a self-important tv newsman, Dick Denton, eager to prove Elephant Man is all phony and no pony. The so-called plot comes unraveled rapidly, page by page, creating havoc and hilarity on its way through an unlikely romance between EM and the beauteously buxom Tracie J. Bombasso, girl reporter, who decides she’d rather have as a boyfriend a man who can remember her birthday than a deeply tanned, bushy-eyebrowed handsome matinee idol like Denton. Houston’s haywire drawing technique, spewing distortion and loose-ends, lends its maverick visualization to this equally off-beat tale in a graphic novel that dares to use the word “peckish.” Houston’s work is perhaps best understood as the logical insane extension, in picture and plot, of what “cartooning” once was when Milt Gross and George Carlson were both practicing their craft at the same time. Now, it’s up to Houston. His books show the art of cartooning taken to the nth degree—perhaps not as far as it can go, but closer than we get most of the time, close to the ultimate extremity to which narrative pictorials can be stretched. And since you have to see it to believe it, I’ve included a few visual fragments in the ensuing NBM Gallery.