|

|||||||||||

|

NOUS R US

Shooter Returns to the Legion

Books for Teen Girls

Keith Knight Gets Harvey

The Beloved

Femlin on Display

Comics for Cell Phones

Iranians Get Top Honors at International Cartoon

Contest

What the FBI-Ellison Settlement Was

Lynn Johnston

on Her Hybrid FBOFW

Infamy at the Famous Palm Restaurant

Ku Klux Klan Komics

Who Is Asok?

Cartoonist PROfiles To Be Reincarnated

Zippy History

Cooke Quits

Spirit

THE PERVERSE

POWER OF THE CARTOON IMAGE

A Reprise of the Danish Dozen, This Time in Sweden

Other Insensitive Cartooning

Burying the Past in order to Deny it: Won’t Work

SAN DIEGO COMIC-CON WRAP-UP

EDITOONERY

Jobs Continue to Evaporate

The Froth

Estate

Murdoch Conquers the Street

LAND OF MY

YOUTH

Denver: A Two-Newspaper Town

And What’s in the Papers

Paris Hilton

Is a Comic Book Character—No Surprise!

JIM IVEY

No Crusader He: Just a Reporter, M’am

COMIC STRIP

WATCH

Zits, FBOFW, Lio and Peanuts, Beetle’s 57th,

Prickly City’s politics, Agnes, and more

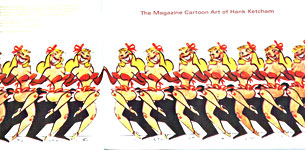

BOOK MARQUEE

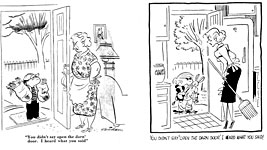

Ketcham’s Magazine Cartoons

Harvey’s Little Louie Loutermouth

Puff for Children

Voutch from Paris

Lisa’s Story: The Other Shoe

FEINSTEIN’S

BOOK

The Ancient

Pursuit as a Sport

Phil Frank Dies

FUNNYBOOK FAN

FARE

Army @ War

Lobster Johnson

Batman Lobo

Shane Glines

Ra’s al Ghul Again

MORE UNDER

THE SPREADING PUNDITRY

More Than Anyone Can Reasonably Absorb at One Sitting

Truly Tedious

And don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by

clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just

this lengthy installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned.

Without further adieu—

NOUS R US

All the News

That Gives Us Fits

For the past month, you’ve been living on canned

goods, articles and opuses I preserved in July for consumption in August whilst

I was trekking cross-country to Colorado, where, withal, I now reside. Safely

ensconced if not yet entirely unpacked (it takes more than a month to unpack

400-plus boxes of books, kimo sabe), I resume the Rancid Raves vigil,

monitoring the Vast Newsmongering Media for signs of cartooning life. We

“resume,” I say, without bothering to backtrack in order to regale you with

colorful bits we otherwise missed in August. What happened in August, stays in

August.

On

the eve of “Heroes” return for a second season on NBC channels, we learn from a

DC Comics press release that the funnybook factory will publish a hardcover

graphic novel based on the tv show, Heroes,

Inc. (240 pages; $29.99). With interior art by Tim Sale plus Michael

Turner, Phil Jimenez, Koi Turnbull, Marcus To and others, the volume will

feature alternate covers by Alex Ross and Jim Lee and an introduction by “Heroes”

star Masi Oka Hiro. ... The one-time editor-in-chief at Marvel, Jim Shooter, who began his comic book

career at the age of 14, writing stories for DC’s Legion of Super-Heroes in 1966, is returning to the title, starting

with No. 37. Shooter left DC in 1976, and he’s returning just in time to create

a story arc that will culminate in the 50th anniversary of the band

of young superheroes. Said Shooter: “I have always loved the concept of the

Legion—young heroes in a fantastic future. The characters have changed a

little, but not enough to spoil the party for me. These are the first comics

characters I ever wrote. They’re still very special to me. I’m having a ball,”

he added, “—I see no reason not to stick around for a long time.” ... Both DC

and Marvel are gearing up titles aimed at a new audience for comic books,

manga-nurtured teenage girls. Beginning with Plain Janes, DC launched a line of graphic novels under the banner

Minx, headed by Executive Editor Karen Berger, one of the chief architects of

DC’s Vertigo line, the most adventurous in comics. “We were looking at the

success of manga as a great sign that teenage girls were actually reading

comics again,” Berger told Matt Phillips at the Wall Street Journal, adding, in an interview with Sean Boyl at

comicbloc.com, “We haven’t had that specific readership since—what? romance

comics [in the 1950s], which were still on a very fringe basis.” Unlike manga,

which translate and reprint Japanese sources but reduce production costs by not

reformatting the books so they must be read from back to front, right to left,

as they are in the country of their origin, DC’s Minx books are manufactured

from scratch in the U.S.: they’re written in English and read from front to

back, left to right, in the usual English-language manner. Cecil Castellucci,

who wrote the first of the Plain Janes,

doesn’t aim specifically at girls when writing. “I just write stories,” she

told Liz Behler at comicbloc.com. “It just happens to be that mostly they tend

to lean towards girls, but I think a good story is a good story to be enjoyed

by all.” Jim Rugg, who drew the book, chimed in on the same note: “I wouldn’t

change the art for a male audience. My approach to the art was fairly realistic

and there wasn’t anything I did to cater to either gender.” Marvel’s approach

to the young female audience is somewhat different, according to Phillips:

“Instead of starting a separate line, the company has been hiring writers known

for their established female following.”

The

October issue of Vanity Fair, the one

with Nicole Kidman, lips parted, baring her bra on the cover, publishes an

excerpt from David Michaelis’ Schulz and

Peanuts: A Biography. Entitled “American Beagle,” the piece is about Snoopy and how he grew from a beagle to

a symbol of the triumph of imagination. (That part, the “symbol of the triumph

of imagination,” is me, not Michaelis; although it might be—I haven’t read this

part of the book yet.) Vanity Fair, which typically has female skin on its cover but hard-nosed reportage inside,

costs $4.50; for merely seven times that amount, you can get the whole Schulz book. But it won’t have bare

female flesh on the cover. ... The coveted Harvey Award (no relation) for best

syndicated comic went to Keith Knight for

his self-syndicated The K Chronicles.

Editor & Publisher reveals that Keef won over four other contenders: Garry Trudeau (Doonesbury), Tony

Millionaire (Maakies), Patrick McDonnell (Mutts), and Antiques: The

Comic Strip by J.C. Vaughn, and Bredan and Frian Fraim. ... To mark the 60th anniversary of the

Air Force and its one-time unofficial spokesman, Steve Canyon, retired Air

Force Master Sgt. Russ Maheras has

produced a new Steve Canyon strip for Air Force Times, a civilian weekly

newspaper that covers that branch of the military. According to E&P, the color strip is “set in the

present and follows Brig. General Steve Canyon as he investigates Taliban

activity in a remote valley in the mountains of Afghanistan.” Canyon’s other

creator, Milton Caniff, would be

celebrating the 100th anniversary of his birth this year. And if you

haven’t yet bought my book about Caniff, click here to visit a

description of it where you’ll be persuaded. ... Mikhaela Reid, a cartoonist, was married to Masheka Wood, a cartoonist, by Ted

Rall, another cartoonist. The last time this sort of thing happened, saith E&P, was in 2001, when Cindy Procious, editoonist for the Huntsville Times (Ala.) was married to Clay Bennett, editoonist for the Christian Science Monitor, by Dennis Draughton, then editoonist for

the Scranton Times (Pa.).

At

the Franklin Bowles Gallery in both San Francisco and New York City, “LeRoy Neiman’s Femlin: 50 Years of

Femlin,” original ink drawings from the pages of Playboy, will be on display through September. Neiman, 86, began

his association at Playboy with the

cuddly little elfin nude, attired in black stockings and arm-length gloves, in

1954, virtually at the launch of the magazine. “Let it be known,” he writes at

the Franklin Bowles website, “I love Femlin! Femlin is an emancipated attention-getter,

a quirky prankster, rambunctious, joyous, but vulnerable—an antidote against

boredom and the humdrum.” The Femlin, whose Rubenesque albeit somehow dainty

embonpoint can be seen regularly on the Playboy Party Jokes page, is one of the happiest visual conceptions of

the century. I’ve bought several of the Playboy Party Jokes books just to get

an inventory of Femlin images. Denis

Kitchen, at one time, was trying to get Playboy to allow him to produce a Femlin figurine, even had a prototype, which I

glimpsed in the back of the booth one time, lo these many years ago when the

Chicago Con had not yet been enchanted—when it convened at the Ramada Inn

instead of the Rosemont Convention Center. ... Bill Crouch, the Rancid Raves

operative who told me about the Femlin show, also reports that the Westport

Historical Society just opened “A Cartoon Legacy: Beetle Bailey - Hi and Lois -

Hagar the Horrible, The Walker-Browne

Family Collaboration,” an exhibition the title of which looks as if it was

compounded expressly to slap opponents of “legacy strips” in the face. Or,

perhaps, just to rub their noses in evidences of the kind of superior

achievement collaboration can produce even over generations. The show will be

on display until January 4, 2008. Visit westporthistory.org.

Comics in the Ether. Japan has blazed another

trail into the future for comics—comic books on mobile phones. The first comic

book to be released exclusively on cell phone in the U.S. is Thunder Road, “a post-apocalyptic

adventure” by Sean Demory, drawn by Steven Sanders, and offered initially just

a few weeks ago by uClick, the digital arm of Universal Press syndicate,

through its GoComics service (where, online, you can find excerpted squibs and

scraps of Rancid Raves, should you be so inclined). Reporting for the

Associated Press, David Twiddy notes: “For $4.49 a month on Verizon—or $3.99 a

month for AT&T and Sprint—subscribers can view nearly a dozen different

traditional comic books.” Current offerings include Bone, Teenage Ninja Turtles, and such new arrivals as “the crime

noirish Umbra and the Hindu-folklore

inspired Devi,” with new chapters or

issues for each title added weekly. GoComics displays one panel at a time,

reformatted from the print version with larger typefaces in word balloons.

Pushing the phone’s buttons advances the view from panel to successive panel,

and the reader can also scroll across the larger images. “Mobile comics have

been a cellular mainstay for years in manga-crazy Japan, where some titles

already begin life on cell phones before going to print,” said Twiddy. Although

just starting out in the U.S., Twiddy says uClick claims 55,000 subscribers a

month “in the first year of offering its GoComics service.” TokyoPop, which

supplies most of GoComics manga titles, is experimenting with animation and

“other cinematic touches,” including tie-ins with “manga-themed games, ring

tones, wallpaper and other content.” Wireless companies are still somewhat

uncommitted, though: “small screens and short battery lives make online reading

a chore.” But steadily advancing technology will doubtless erase such

reservations.

Sanders

admits the small screen presents challenges in devising the visuals, but the

new medium also offers opportunities for the cartoonist to control how the

reader peruses the story, one panel at a time without being able to skip ahead

to the last panel, where the surprises lay in wait. “I think the future of

comics itself lies in digital format,” Sanders said. He observes that with the

disappearance of the 10-cent comic book of yore, comics are no longer a cheap

form of entertainment. From this realization, Sanders draws a startling

insight: Comic books priced at $3-4 aren’t likely to attract purchasers other

than those who are already “heavily invested” in comics and used to reading

them—and buying them at today’s prices. The economics of the funnybook biz seem

poised to work against developing a future audience.

Elsewhere: Editor &

Publisher’s 2007 Syndicate Directory is out, listing all the features currently

distributed by syndicates. A tally of the comic strips on today’s horizon comes

to 206; it was 214 last year. But the panel cartoons have gained a little—150

as opposed to 147 last year. At a time when various pundits are predicting the

demise of newspaper comics, this nearly static status is encouraging. ... The Week magazine, which appeared as a

fresh face among the weekly newsmags a couple years ago, earned my applause by

using a painted cover that usually featured a caricature of the week’s big news-maker—a

cover political cartoon, in full color. The magazine also devoted a page or two

every issue to an array of the best editorial cartoons of the week, another

plus. And the cartoons were usually fairly tough-minded—not the Jay Leno sort

of editoon that Newsweek typically

publishes. Lately, alas, the cartoons have become more laugh-inducing than

thought-provoking. ... According to dutchnews.nl, the best read magazine in the

Netherlands is the Donald Duck comic

book. ... From Editor & Publisher,

we learn that Tom Toles, the

unflinching editoonist at the Washington

Post, ranked 48th in GQ’s list of

“The 50 Most Powerful People in D.C.” The Post’s executive editor Len Downie agreed with the magazine’s choice: “Whenever

people from the newsroom get together, Tom is there—no matter if it’s a local

subject, a national subject, an international subject. That’s not something you

normally expect from an editorial cartoonist.” ... At the first International

Cartoon Contest in Syria, 207 cartoonists representing 29 countries

participated, with 13 Iranian cartoonists collecting the top prizes. The event

honors Palestinian cartoonist Naji al-Ali, saith presstv.ir, “the most famous

political cartoonist in the Arab world,” who produced more than 40,000 drawings

and created a cartoon character, Handala, “who has bcome an icon of Palestinian

defiance.” Al-Ali was shot to death by “unknown persons” in London in 1987; the

next year, the International Federation of Newspaper Publishers posthumously

awarded him the Golden Pen of Freedom. ... Harlan

Ellison’s suit against Fantagraphics Books for defamation was resolved some

weeks ago, shrouded in legally imposed silence. But newly released court

records reported by Mark Rahner at the Seattle

Times reveal the gist of the agreement: “The two parties will stop messing

with each other,” and Fantagraphics is removing the two passages in its

history, Comics As Art, that provoked

Ellison’s suit. Moreover, in future editions of The Comics Journal Library Vol. 6: The Writers, Ellison’s name will

be expunged—as well as a 1980 interview with publisher Gary Groth that resulted

in another suit being brought this time against both Groth and Ellison by

Michael Fleisher, who alleged libel. Groth gets 30 days and 500 words on

Ellison’s website (www.harlanellison.com) to rebut Ellison’s

statements “that accuse Groth of embezzling funds in the Fleisher litigation

and soliciting contributions to the Fantagraphics Legal Defense Fund under

false pretenses” and other claims, most of which are doubtless further

instances of the famous Ellison tendency to extravagance in verbal appearances.

... HarperCollins is planning graphic novel adaptations of the works of J.R.R.

Tolkein, Agatha Christie and C.S. Lewis. ... The New Yorker has introduced a board game version of its back-page

cartoon caption-writing contest; the game went on sale in Target stores in

early August, and it had been on sale in Barnes & Noble and independent

book stores earlier in the year.

Lynn Johnston’s “hybrid” version of her

popular strip, For Better or For Worse, began September 3. As we’ve reported before, Johnston originally thought she’d

just end the strip this fall. She’s sixty, she said, and she wanted

deadline-free time to do other things that she’d always wanted to do. And she

has a health issue: she suffers from dystonia, a neurological condition that

makes her hands tremble. She controls it with medication, but it’s still there,

lurking. And she’d run through the storyteller’s cycle, as she told Chris

Mautner at the Patriot News: “A

husband and wife who have children, the children grow up and now they have

children. Michael has children who are the same age that he and Elizabeth were

when the strip began.” It seemed a good time to dismount from the cycle. I suspect

Johnston’s syndicate, Universal Press, wanted her to reconsider. Maybe not:

Universal is extraordinarily accommodating of its cartoonists’ wishes. Whatever

the case, Johnston had second thoughts about stopping, and then she had the

hybrid notion: re-run FBOFW strips

from its early years as if Michael is telling the family history to his

children.

This

was a happier solution, happier than stopping altogether, cold turkey. It would

cut down on the time needed to produce the strip, freeing Johnston to do those

other things she wanted to do; and the strip’s fans would still have the strip

to read. (And many of the fans had never seen the early years of FBOFW because it hadn’t been in all that

many papers when it started.) Moreover, the hybrid option assuaged the

storyteller. Ultimately, she told Mautner, she couldn’t stop in September: “The

characters sort of won’t let me.” There are loose ends, danging plot threads.

The hybrid permits her to tie them all up, slowly, over the next few years as

she mixes new material in with the re-running material. “I’m interested and

readers are interested to know what is going to happen with Anthony and

Elizabeth,” she said, referring to the divorced father whom Elizabeth dated

when they were both in high school. “That resolution can’t happen too fast,”

Johnston continued. “They’ve only just started to see each other again after a

long time apart. Both have had other relationships and now he has a child and

some baggage, and so does she. You just can’t wrap it up too quickly.” The

hybrid permits the storyteller to do what she’s always done—to examine her

characters, their personalities and motivations, why they do what they do. It

was to answer those sorts of questions that she began telling stories: FBOFW started as a gag-a-day strip about

a young family, but then Johnson began to wonder—why did Ellie do that? What

will happen next because of what she did? The same kind of curiosity drives her

now.

“A

lot of people didn’t like Anthony,” she said. “But you see, Anthony has never

really had an opportunity to be recognized and understood by everybody. He was

just a shadow figure. And all the reader has seen is little bits and pieces.

And so that’s another reason why the [run of] the strip has to be extended—so

that Anthony’s character can be more fully explored. And his [failed] marriage

discussed and his relationship as a single parent and his business sense and

the things he likes to do. He’s just not a complete character, and it’s hard to

accept that Elizabeth, who is a well-known character, should be lost to someone

that nobody knows.” Before the current hybrid started, Johnston had Elizabeth

explaining the failure of Anthony’s marriage to a friend. The process of

understanding Anthony has begun. It will continue, weaving in and out of the

story Michael is telling his children of his own childhood.

The Permanence of Infamy. The Palm was originally a

speakeasy in New York. Located on Second Avenue just around the corner from the

offices of King Features, the place became a hangout for cartoonists and

newspapermen in the 1920s and 1930s, and the cartoonists, falling,

occasionally, under the influence of the spirits of the place, decorated the

walls with pictures of their comic strip characters. The Palm eventually became

a legitimate restaurant and saloon and opened an overflow facility across the

street, dubbed Palm Too. Inspired by the second bistro’s success, the founders

opened yet another adjunct in Washington, D.C. Then in Dallas, Los Angeles,

Denver—even San Diego. All have cartoon murals, but the vintage work is in the

original joint in New York. The Washington Palm recently underwent renovation

and moved its entrance to the side. It also moved the caricatures from the old

entrance to the new one. Jeff Dufour and Patrick Gavin at the Washington Examiner wondered whether one

of those caricatures would mysteriously “disappear.” Would Mark Foley’s mug,

which has greeted guests at the old entrance, continue beaming on them in the

new entrance? Or would the now disgraced congressional sex fiend be consigned

to limbo? Probably, Foley will still be there. “What’s politics without a

little scandal?” asked a Palm spokesman. “You can be famous, infamous, or

forgotten—with few exceptions, once you’re on the wall, you’re on the wall.” Said

Dufour-Gavin: “That also answers the question about former Rep. Randy ‘Duke’

Cunningham’s visage on the restaurant’s back wall, as well. It’s here to stay.”

More Elsewhere. The indefatigable Craig Yoe at his arflovers.com site has uncovered yet another

strange fragment of comics history—Ku Klux Klan Komics. Shocked and awed, Yoe

notes that in the strip, Our Ku Klux Klan by cartooner Al Zere, the “Klan is

kind of a cute, lovable Shmoo-like mob of aggressive masked do-gooders who you

call upon, kind of like Superman, to right life’s little wrongs—getting rid of

meddling mothers of girlfriends, putting snobby rich dudes in their place,

etc.” The strip ran in the New York

Evening Post in the early 1920s, demonstrating that the Klan had some sort of followership up north. In fact,

Indiana was a hotbed of Klan activity in the 1920s. ... Asok, the weirdly

brilliant character in Dilbert, is a

native of the sub-continent India, named after an Indian colleague of Scott Adams, the strip’s creator. I

have wondered, occasionally, where the name came from; now I know. Asok arrived

in the strip in 1996 as a summer intern. Despite being “mentally superior to

most people on earth,” Asok was laid off when his job was outsourced to India,

so he joined the company to which his job was outsourced and now works by

“Indian Standard Time.” He was earlier denied permission to be a regular

employee, reports the Hindu in New

Delhi, even though he performed the functions of a senior engineer and was told

“as you gain experience, you’ll realize that all logical questions are

considered insubordination.” ... Baldo,

a comic strip about a teenage Latino and his family by Hector Cantu and drawn by Carlos

Castellanos, will pay tribute to Latino WWII veterans with a sequence

starting September 17, featuring Benny Ramirez, a fictional American Latino now

in his eighties who lost a leg during the War. Saith E&P: “Ramirez will share his stories and discuss how he felt

about serving in a military for a

Reincarnation of Cartoonist PROfiles On the Way. From Editor & Publisher: A quarterly cartooning publication titled Stay Tooned! is scheduled to premiere in

November. "I intend to combine the best parts of Cartoonist PROfiles— telling the stories of professional

cartoonists—and The Aspiring Cartoonist—information

and instruction for cartoonists," John Read, the periodical's founder,

told E&P. "My plan includes

marketing it to working cartoonists, aspiring cartoonists, fans of cartooning,

and people who buy cartoons." The first and subsequent issues of Read's

subscription magazine will also focus on non-newspaper cartooning and

cartoonists— including animators, comic book artists, greeting card creators,

children's book illustrators, etc.

He

said the first issue will have a southern-cartoonists theme, and feature people

such as Steve Kelley, editorial

cartoonist for the Times-Picayune of

New Orleans and Creators Syndicate; Marshall

Ramsey, editorial cartoonist for the Clarion-Ledger of Jackson, Miss., and Copley News Service; Scott Stantis, the editorial cartoonist for the Birmingham (Ala.) News and Copley who also does the Prickly City strip for Universal Press Syndicate; and John Rose, who does editorial cartoons

out of the Harrisonburg (Va.) Daily News-Record as well as the Kids' Home Newspaper cartoon/activity

page for Copley and the Barney Google and

Snuffy Smith strip for King Features Syndicate. Also: comic creators Mark Pett (Lucky Cow/Universal), Marcus

Hamilton (Dennis the Menace/King), Jimmy Johnson (Arlo and Janis/United

Media), and Greg Cravens (The Buckets/United).

Read

is long-time cartooning fan who worked as an assistant director and locations

scout in the film- and TV-production industry for 20 years after graduating from

the University of Southern Mississippi. He then became a graphic designer for a

sign company in Jackson, Miss. Read has also done freelance cartoons and taught

kids how to draw cartoons. His magazine's Web site is still under construction,

but, in the meantime, Read can be reached at johnread3@hotmail.com.

A Short Zippy History. Zippy the Pinhead, Bill Griffith’s incomprehensibly

hilarious comic strip star, was once almost a tv personality. By 1997, the time

of an interview Bob Andelman conducted with the cartoonist for Mr. Media,

Griffith and his wife, cartoonist Diane Noomin, had produced nine drafts of a

live-action movie script over the previous 12 years, but nothing came of any of

them. Then they wrote several scripts for a animated tv version of the

surrealistic character, famed for saying, among other things, “Are we having

fun yet?” The expression long ago passed into common parlance, much like R.

Crumb’s “Keep on truckin’,” and, like Crumb, Griffith realizes not a dime for

originating the by-word. “The only time it annoys me,” Giffith told Andelman,

“is when it’s another cartoon character saying it.” Like Garfield or Dennis the

Menace. “The worst of all was a Ziggy t-shirt,” Griffith added. “That rankled

for a few minutes.”

Griffith

created Zippy for an underground comix title in 1970 and had no expectation of

getting into national syndication. The comic featuring Zippy, he thought, was

“too hard-edged” for mainstream consumption. “What makes people like something

is if they reinvent it themselves,” Griffith said, “—they make the character

become who they think it should be. That’s why the blandest are usually the

most successful. The most successful strips in America tend to be the ones that

are the least challenging. Zippy is

challenging. That’s not what most people what to do when they casually read

through the comics. They just want to get through it.” And a classic criticism

of Zippy is that you have to read it

twice, sometimes even more, before you get it—and sometimes, you don’t get it

even then because there’s nothing, exactly, to “get.” What can you make of

another celebrated Zippy comment: “All life is a blur of Republicans and meat”?

Admirable, awe-inspiring, apt. But what does it mean, exactly?

Zippy got into King Feature’s syndicated

line-up almost by accident. Or maybe it was an insidious plot. When Will Hearst

III took over the San Francisco Examiner, he wanted something offbeat for his readers, and in 1985, he signed up Hunter

Thompson and Zippy, which, at the

time, Griffith was self-syndicating to alternative newspapers. A year later,

Hearst’s King Features wanted the strip. Griffith, taken aback and not quite

sure he wanted the daily grind of a syndicated strip, responded with a list of

non-negotiable demands—“things I would require in order to work for them,”

Griffith told me when I interviewed him in 1992. “I had thought of the list as

a way of not working for them: they would never agree to these things, I was

certain. I said I had to keep my copyright; I had to keep the larger format— I

actually draw the strip out of proportion: it’s taller than any other strip ...

so that it has more headroom [for speech balloons]. ... You can’t censor it;

you can’t edit it. You have to guarantee me a certain amount of money weekly

because I’d be giving up my exclusive deal with the Examiner. I felt like I was taking hostages. A sort of power play.

And this guy sat across from me [his name was Alan Priaulx] and said ‘Yes’

instantly to everything. About six months later, I found out a little more about

why he was so agreeable. ... Six months after Zippy started running with King, this guy quit. Which kind of

freaked me out a little: I thought maybe I was going to go with him. But

everybody assured me that they liked Zippy and that it was doing fine.” Then Griffith got a letter from Priaulx; he was

now in a completely different business, “and he said he just wanted to tell me

what had happened, how Zippy had come

to King Features. He said he’d wanted to leave the syndicate—he wasn’t happy;

it wasn’t the right job for him—but he wanted to leave with a bang. And he said

he felt that by hiring me and by adding Zippy to the King Features roster, he was leaving a ticking time bomb on their

doorstep as he left. He just wanted to shake up King Features. He just wanted

to give them the weirdest strip in America.” The bomb is still ticking; in

1997, the time of the Andelman interview, it was in about 200 newspapers—“185

papers more than I ever thought it would be in,” Griffith told Andelman.

COOKE QUITS

SPIRIT

Darwyn Cooke, whose interpretation of Will Eisner’s Spirit has been hailed

here and elsewhere for its excellence and faithfulness to the “spirit” of the

original, will leave the title after No. 12. Cooke’s inker, J. Bone, is moving into other projects,

and Cooke doesn’t want to handle the series without him. A new creative team

had not, by early August, been named. Speaking of the Spirit led Cooke to

comment in dailypop.wordpress.com on what he sees so far in Frank Miller’s work on the movie

version of the iconic character: “I think it will be a really fantastic crime

movie, and it’s probably going to be visually stunning, but I think his

interpretation seems just a little one-sided to me. From what his interviews

indicate, he seems to be concentrating on the sex and violence. I always

thought the strip had so much more depth to it than that. Those were elements

that helped drive many of the stories, but I don’t think they were what the

strip was about. And I think at the end of the day, as nasty as the business

was that the Spirit gets involved in, it’s a hopeful strip. It’s got optimism

at its heart, and humanity. I don’t know that the movie is going to reflect

that, but I think it’s probably going to be damn exciting.”

At

the San Diego Comic-Con, Cooke had other discouraging words for the medium and

its fans. “There is no room in the direct market for new ideas,” he remarked,

echoing what others, Grant Morrison among them, have said. Presumably, the major publishers are playing with a deck

of what they’re sure will produce winning hands—namely, all the tried-and-true

long-john legions. They don’t want to risk anything on something new and

different, untried— nothing that isn’t an obvious candidate for Hollywood

treatment. And all those blockbuster movies aren’t doing the comic book medium

any good, financially. Cooke thinks direct market comics “are on their way to

extinction. ... It doesn’t matter how much money the Spider-man movies make if

it doesn’t bring anyone in to buy the comics. This theory’s been floating for

twenty years now that these movies will bring people back to comics. It doesn’t

work that way. Ask any twelve-year-old kid on the street, he probably thinks

Spider-man was created for the movie—or for the [Saturday morning tv] cartoon.

He doesn’t know it’s a comic book.” And so he doesn’t go looking for the comic

book.

Moreover,

Cooke said, the monthly comic book itself is becoming “less and less

important.” Every publisher is gearing monthly comic book production towards

the subsequent compilations that are issued shortly after a given multi-issue

story arc ends. The money these days is in graphic novels, and collections of

monthly comic book story arcs pass for “graphic novels,” and so they sell,

better than their initial publication in monthly format. In my view, one of the

most vibrant developments in four-color fiction has been the limited

mini-series in which writers and artists focus on a single story arc and the

accompanying cast of characters. Storylines and characterizations are refined

and focused, yielding books that are inevitably better than the monthly

installments of a title that is designed, apparently, to plunge ahead forever,

whether the creators have an idea for a decent story or not. One intriguing

by-product of this imperative happened at Marvel in the early days of the

Second Coming of Comic Books when Stan Lee, unable to think of suitable endings

for the handful of stories he was simultaneously scripting in various titles

for his artists, simply continued stories from issue to issue, hoping something

would occur to him. Usually, something did, eventually, and one story arc would

end and another would begin. Cooke sees the evaporation of the monthly series

as fundamentally a good thing: “Ultimately, I think we’re going to see graphic

novels, manga, superhero books, and everything else in album form [hardcover

books in the graphic novel mode], and everything else in album form in

bookstore chains, and they’ll have to fight it out with all the other product

available, which is, I think, the way it should be.”

Cooke

is looking at the graphic novel format for his next projects, he says—rumored

to be a fairy tale for children and another that will have “sex, and violence

and swearing” and “involves a lot of paranoia and craziness. I think it’ll be a

fun read for the adults out there.”

Pithy Pronouncements

Memoir

of the Day: “I start things, but I never ...” —D. Stahl

Einstein

believed, he said, “in Spinoza’s God, who reveals himself in the lawful harmony

of all that exists, but not in a God who concerns himself with the fate and the

doings of mankind.”

“I

eat cold eels and think distant thoughts.” —Jack Johnson, explaining the

attraction of black men to white women

MORE ON THE

PERVERSE POWER OF THE CARTOON IMAGE

Part I: Muslims Again

We don’t wish to insult Islam any more than we’ve

insulted Christianity or Judaism, but Muslims must eventually come to realize

that their feverish protests about cartoon depictions of the Prophet Muhammad

are becoming cliche. Boring. And with boredom comes a rapid diminishing of the

sort of attentiveness among the public that the protests are intended to

provoke. The latest outbreak took place in Sweden in Oerebro, a town west of

Stockholm, where the local paper, Nerikes

Allehanda, published on August 18 or 19 (accounts differ) a drawing of a

dog with the head of a bearded man in a turban. The drawing, which can probably

be found somewhere on the Web, is quite sketchy—almost crude— so sketchily

vague, in fact, that if the artist and the newspaper that published the drawing

hadn’t identified the face as Muhammad’s, we couldn’t possibly know who it is

intended to be. How they know is another facet of the puzzle: since

visualizations of the Prophet are prohibited by Islam (lest they inspire idolatry),

no one can possibly know what Muhammad looked like. No one, therefore, can

“caricature” him. All of which, fascinating though it may be, is beside the

point. The point is that Swedish Muslims took offense at this desecration of

their religion’s holy founder, who is revered in Islam to an extent few other

religious figures are in any other religion. About 200 Muslims staged a local

protest, the 57-member Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC) condemned

the “cartoon,” and ambassadors and other governmental dignitaries of Islamic

countries soon chimed in, all equally outraged at this provocation. Arab News reported that OIC

Secretary-General Ekmeleddin Ihsanoglu “strongly condemned the newspaper for

publishing the blasphemous caricature and said that this was an irresponsible

and despicable act with mala fide and

provocative intentions in the name of freedom of expression.” While he called

on the Swedish government “to take immediate punitive actions against the

artist and the publishers of the newspaper,” he also called upon Muslims “to

remain calm and to exercise restraint.” The Swedish prime minister, seeking to

avoid the mistake the Danish prime minister had made last year by refusing to

hold talks with Muslim ambassadors who had requested a meeting, invited

representatives of Muslim countries to meet and discuss the issues. At the same

time, he expressed regret that Muslims were offended but noted that politicians

in Sweden cannot “pass judgment on the free press.”

Despite

echoes of the Danish disturbance of last year, the drawing in Nerikes Allehanda was not, like those of

the Danish dozen, a cartoon. It was, however, a picture of Muhammad, according

to the man who drew it, Lars Vilks, who drew a series of pictures intended to

spark discussion of the principles of free expression. Another drawing shows a

giant hook-nosed pig, looming over hillside houses; its caption: “Modern Jew

sow, swollen by capitalism, on her way to tear apart some peaceful villages.”

Vilks hoped a discussion of freedom of speech would examine what limits, if

any, should be imposed. Interviewed by the news agency TT, he said he had

observed how Islam is treated with greater deference than other religions, and

yet, Vilks continued, “Muslims are able to have a go at Jews in the roughest

manner without any reaction because people are afraid to attack Muslims.” His

drawings were intended for display in an art gallery, but after several

galleries refused to display them, the issue was taken up by Nerikes Allehanda, which published one

of the drawings, the Muhammad drawing, to show what prompted the reluctance

among gallery managers.

In a

later report in Arab News, OIC’s

Ihsanoglu expressed concern that “this kind of irresponsible and provocative

incitement in the name of defending freedom of expression was leading the

international community toward more confrontation and division.” He said he

hoped a legal mechanism could be developed to prevent the recurrence of such

episodes. “Freedom of expression does not entail freedom to insult,” he said.

“There has to be a way to stop this. There are certain values that every

country abides by. There are red lines in all societies. We want them to know

that we don’t mind their criticism of our religion, but our Prophet is off

limits.” The exquisite irony in these sorts of dilemmas is that freedom is

freedom: if limits of any sort are imposed upon it, it ceases to be freedom.

While it is true that human rights is a value in Western societies and it is

equally true, as Ekrem Dumanli maintained in Todays Zaman (Cf. turkishweekly.net), that “respecting human rights

means respecting people’s identities and the sacred elements and sacraments

that form those identities,” if a society that espouses freedom of expression

begins to exempt certain subjects, whether religious or not, from examination

or comment in deference to the wishes of those who might be insulted, the slide

down the slippery slope has begun. If the Prophet is exempt, who’s next? Can’t

say anything untoward about Jesus? And then maybe George Washington? Lincoln?

Henry Ford? George W. Bush?

Many

Muslims, according to Siraj Wahab in Arab

News on September 13, believe that calls for dialogue between the Islamic

world and the West are meaningless “in the face of such extreme provocation.

They are a waste of time. Dialogue should not be two monologues in two

different directions. It will not and does not lead to any better

understanding; it does not lead to any change in positions.” Wahab added that

the lesson Muslims learned from the Danish turmoil is simple: “Boycott their

products, and then they get the message.” E-mails have started listing Swedish

products to boycott. Some Muslims, however, believe they should simply stop

responding to such provocations: “They are provoking us because they know we

can be provoked,” said one.

Meanwhile,

to complete the cliche, news.bbc.uk reports that the purported head of al-Qaeda

in Iraq has offered a $100,000 reward for the murder of Vilks—$150,000 if the

artist is “slaughtered like a lamb.”

Cliche

but tragic. Aren’t you glad you live in a secular society?

At

times like these, we will do well to remember something Doug Marlette said

(slightly paraphrased here to make it universally applicable): “Editorial

cartoons push the boundaries of free speech by the very qualities that endanger

them. Because cartoons can’t say ‘on the other hand,’ because they strain

reason and logic, and because they are hard to defend, they are the acid test

of the first Amendment, and that is why they must be preserved. As long as

cartoons exist, Americans can be assured that we still have the right and

privilege to express controversial opinions and offend powerful interests.”

Part II: The Contagion Takes

To extend the cliche: the terrorists are winning. Two

successive installments (August 26 and September 2) of Berkeley Breathed’s Sunday strip, Opus, were killed by cautious editors at about 25 of the 200 or so

newspapers carrying the feature because they feared the strips might be

offensive to Muslims. Or because of a mildly suggestive joke. Or both. In the

dubious strips, Steve Dallas, Breathed’s caricature of shallow male chauvinism,

confronts his blonde bimbo girlfriend’s equally shallow pursuit of fads. Lola

Granola dons a hijab one week and announces that she’s rejecting “decadent

Western crud,” which is okay by Steve because if she gives up the American Idol

notions of gender equality, he thinks he’ll be the sexual beneficiary of her

more submissive attitudes. The next week, Steve commands Lola to doff the burqa

she’s donned in favor of a “smokin’ hot yellow polka-dot bikini” for their day

at the beach. But when Lola returns, she’s covered head-to-toe in a “burqini,”

and she makes a joke about Steve not “getting it,” alluding, on the one hand,

to Steve’s inability to perceive the value of Muslim-inspired female modesty

and, on the other—we may assume—to the likelihood that she’ll be denying him

her sexual favors. The Washington Post,

the flagship paper for the Washington Post Writers Group syndicate that

distributes Opus, was one of the

papers declining to publish the strips. Several commentators, Eugene Volokh at

huffingtonpost.com among them, voiced alarm at the tendency they perceive in

such “censorship.” Said Volokh: “It looks like certain media outlets are

establishing or reinforcing a social norm that immunizes Islam and Muslims from

a certain kind of commentary. And we as readers and writers should try to fight

such a social norm, by criticizing those who are acting on it.” It’s fairly

clear that it’s the Muslim content of the strips—or, indeed, any

“Muslim-related humor”—that gave editors pause. The week before the first Lola

strip, Opus ridiculed Jerry Falwell, and none of the client papers dropped the

strip. Other religions clearly do not enjoy the immunity that Islam in U.S.

newspapers enjoys. Newspapers have regularly published editorial cartoons

poking fun at the inherent hypocrisies of the Catholic Church as revealed by

the sexual depredations of its priests; and few complain about it. But editors

are obviously intimidated by the violent reactions of radical Islamists. Since

the object of terrorism is to strike fear into the hearts of the populace, we

must conclude that the terrorists are winning. Even in a so-called secular

society. Among newspaper editors anyhow.

On

September 16, the butt of the joke (so to speak) in Opus was a fat lady. I’m waiting to see if that inspires protest

from obese America. It apparently didn’t intimidate any newspaper editors.

Part III: The Contagion Spreads

The success of Islamic protest against cartoons that

are alleged to be offensive has given encouragement to newspaper readers

everywhere, each of whom—every one of the millions—can find something offensive

to them in something the newspaper publishes. Most often, it seems, in an editorial

cartoon. In Cleveland, a 12-year-old girl was accidentally killed when she was

hit by a stray bullet from a gunfight in the street. The city’s mayor, reported

the Associated Press, “devoted special attention to the case, attending a news

conference at the crime scene and hugging the child’s mother, who is a friend

of his daughter.” At the Plain Dealer,

editoonist Jeff Darcy sought to

point out that a mayor’s time and effort might be better spent: a mayor ought

to be concerned about all of his city’s citizens—and all of the victims of

street violence—whether they are friends of his daughter or not. Commendable

though the mayor’s sentiment in this instance might be, it smacks, vaguely, of

a narrow focus of concern, akin to cronyism. Darcy drew a cartoon of a little

girl on the street wearing a shirt that reads: “Don’t shoot—I’m a friend of a

friend of a friend of the mayor’s daughter.” The paper’s editor subsequently

apologized to the dead girl’s parents who had complained that the cartoon was

insensitive. Of course it was. Most cartoons, as Doug Marlette has so helpfully

pointed out (above), are insensitive. Perhaps there is another way that Darcy

could have made his point. In fact, there is certainly another way. But that

way, perhaps, might have been offensive to someone else.

College

campus newspapers are particularly vulnerable: their cartoonists are often not

too expert, and their shots sometimes go astray as a result. At the University

of Virginia’s student paper, the Cavalier

Daily, cartoonist Grant Woolard wanted

to heighten awareness on campus of the terrible famine in Ethiopia. He drew a

cartoon that showed several nearly naked black men fighting each other with

sticks, stools, boots, shoes and other artifacts. The cartoon was captioned:

“Ethiopian Food Fight.” The night after the cartoon was published, 200 students

held a sit-in to protest what they saw as a racist cartoon, demanding that

Woolard, who is white, be fired. One letter to the paper’s editor the next day

said: “I see two interpretations of the cartoon: 1) Any fight between cannibals

is a food fight; 2) Ethiopians are so poor that they eat things like sticks,

chairs, or boots and are in fact fighting with their food. Either way, the

cartoon is not funny. More importantly, it is blatantly racist.” Woolard’s

motive is commendable, but, as the letter-writer demonstrates, the cartoonist

woefully underestimated the awareness of his readership. Or maybe he was dead

right. The letter-writer, at least, wasn’t even vaguely aware of the famine in

Ethiopia, and so, lacking that knowledge, he or she focused on the imagery—the

fighting naked black men—and thought that, a visualization of jungle violence,

was the cartoonist’s message.

Woolard,

appalled at what his cartoon provoked, explained: “I was not trying to

trivialize famine. When you have a food fight, you fight with food. This

cartoon [was supposed to bring] you to the realization that there’s a famine.”

There is no food, so if you’re going to have a food fight, you have to use

something else. Sticks, furniture, shoes. “In general,” Woolard continued in

his interview with the Washington Post,

“people give very little thought to starving people in other countries. But I

will admit that I really lacked the foresight in anticipating the reaction. I

should have thought that they were going to think I was portraying Africans as

savages.” Woolard’s editor, Herb Ladley, didn’t realize the implications of the

cartoon either. “This one came in late at night,” he said, “and my initial

reaction was, ‘This is offensive.’ But we print a lot of offensive things.” He

cited an earlier Woolard cartoon that depicted the Virgin Mary and indicted

that she had a sexually transmitted disease. He realized the Ethiopian cartoon

was a mistake “the instant the public raised a question about it,” he said. A

day or so later, Woolard was forced to resign, and he’s irked about it. Two of

the paper’s editors approved the cartoon for publication, and both are still on

the staff. “Editors should take equal blame,” Woolard told Barney Breen-Portnoy

at the Daily Progress in

Charlottesville: “This is not just about me. This is also about standing up for

the First Amendment.” Certainly is.

Part IV: ... and On and On into Even Our Own

Benighted Past

So sensitive have we become—hypersensitive—that we

seek to deny history rather than to risk offending anyone. When Herge’s 1930-31 version of Tintin in the Congo was reprinted again

in July, it inspired a good deal of hand-wringing about the patronizing

colonial attitude it embodied, the stereotypical caricatures of Africans, and

their portrayal as lazy and childlike. At the heart of the matter was the undeniable fact that the book is

intended for young readers. Borders in Britain and the U.S. reacted to protests

by moving the book from the children’s section to the adult section. One list

commentator scoffed astutely enough about “this over-sensitive culture and the

implicit insistence that children are more important than adults (whom,

incidentally, are treated as children).” But when he insisted, quoting Stanley

Kubrick, that “no work of art has ever done social harm though a great deal of

social harm has been done by those who have sought to protect society against

works of art which they regarded as dangerous,” he drew a scornful response

from another lister, who, citing Uncle

Tom’s Cabin and the movie “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” averred that art

most certainly does have an effect. Perhaps “no single [work] is going to

singlehandedly transform society or move an individual to violence, but that

does not mean that they have no effect.” Those who maintain that works of art

are essentially harmless are saying, at the same time, that works of art have

no effect, an assertion that flies in the face of Mein Kampf, for example, not to mention reams of anti-Semitic

material, the virulence of which in schools in Palestine fuels the Arab-Israeli

conflict. Still, it seems a little extreme in the case of Tintin in the Congo to ban the book, which is what a Congolese

student studying in Brussels sought with a law suit; ditto a Swede of Congolese

origin, who admitted, when his case was dismissed, that “the important thing

was to draw attention to the racist character of this book which no longer has

a place in 21st century society.” That, indeed, is the important

thing: call a spade a spade, if you will—call racist material racist—and we’ll

learn from it. Jonathan Zapiro, an

outspoken and courageous South African political cartoonist and no stranger to

censorship attempts (see Opus 208), commented: “Herge was ashamed in later

years and had stipulated in his will that Tintin

in the Congo not be published in English. But censorship is not a good

thing. Do you censor Alan Paton’s patronizing early works, or Salman Rushdie?

Publish with a disclaimer but don’t stop people publishing.”

Last

summer, just before the Tintin story broke, a minor hubbub occurred on one of

the comics lists I frequent when someone complained that Winsor McCay’s work reflected “a gratuitous racism.” In Nemo, the

juvenile hero is accompanied on his dream adventures by a green-skinned Flip

and a dark-skinned “Imp,” a refugee from McCay’s earlier work, Tales of the Jungle Imp, in which South

Sea Islanders or Africans scamper about. Racist, yes, but McCay was no more

racist than anyone else at his time. What we call racism today was the coin of

the realm in McCay's day. The people who weren't what we'd call racists then

were the exceptions, not the rule. Moreover, many cartoonists of that time were

not so much racists as humorists: they thought anyone who looked

"different" looked funny. So African Americans, the Irish, Jews—all

looked "different" and hence looked funny. They drew them that way

because they thought they'd get laughs. And they did.

We

live still in a racist society, and it was racist then, only, perhaps, more so.

McCay was simply channeling the prejudices of his time. When I say that

cartoonists of that day were not so much racist as humorist, I don’t mean that

they weren't racist; they were. But I think they were humorists first, racists

second. That is, they were both. But as cartoonists, it was the "different

appearance" of racially different persons that appeared to them to be

"funny," and for that reason, we have a carload lot or more of cartoons

of the late 19th and early 20th century that depict racial and ethnic

stereotypes—African Americans, Irishmen, Jews, American Indians, etc.

Cartoonists thought they looked funny; that's undoubtedly a racist attitude,

and the humor agenda does not excuse it. But cartoonists were no more (and no

less) racist than their social milieu.

Herge

explicitly acknowledged the influence of his time and place upon his portrait

of the Congo: “The fact was that I was fed on the prejudices of the bourgeois

society in which I moved. ... It was 1930. I only knew things about these

countries that people said at the time: ‘Africans were great big children ...

Thank goodness for them that we were there!’ And I portrayed these Africans

according to such criteria, in the purely paternalistic spirit which existed

then in Belgium.”

Cartoonists

almost always channel the prejudices of their time. How else would they appeal

to a general readership? It is a mistake to judge other times and places by the

standards of our own supposedly enlightened time. Well, that's not quite the

case: we can judge them, of course, and we can find them reprehensible,

but we can scarcely condemn other people in other times and places for holding

opinions typical of their time and place. Such opinions constitute "a

problem"? Well, yes; but what of it? Was Christian persecution of the Jews

in the Middle Ages a problem? Was Roman persecution of Christians a problem?

Problems imply the need for a solution, and I daresay that whatever solution we

offer today for the "problems" of the Middle Ages or the Roman Empire

is meaningless. We can't fix things back then; they've happened. We can,

presumably, fix our own derelictions, but we aren't likely to if we go around

patting ourselves on the back for our superior liberal enlightenments (compared

to the benighted McCay, say)—particularly since we are not superior or liberal

or enlightened all that much.

To

expect McCay and/or Herge to reflect our ideas of racial equality is expecting

a good deal too much; both were creatures of their times, as most cartoonists,

if successful, must be. A successful cartoonist appealing to a mass audience

had to reflect that audience’s attitudes or fail.

Fascinating Footnote. Much of the news retailed

in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at http://www.rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John

Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature,

cartoons, bandes dessinees and

related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve

deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and

lore are Mark Evanier’s www.povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s www.DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s www.comicsreporter.com.

And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, http://www.comicsdc.blogspot.com

SANDY EGGO

The last word on attendance at this year’s comics

extravaganza was more of a whimper than a bang. The Comic-Con International at

San Diego has grown steadily for 37 of its 38 years, attendance spiraling into

the stratosphere, year by year. But not this year. Despite recording three

“sold out” days this year (only one, for the first time ever, last year),

attendance seems to have leveled off at around 125,000, just about where it

stood last year. I’d been guessing 140,000-160,000 for this year, assuming,

with history as a guide, that attendance would increase by the usual

leap-frogging increments of the past. But this year, the show’s management

imposed artificial “caps” on attendance each day. “Once those caps were met, we

basically shut down,” said David Glanzer, Sandy Eggo’s pr guru, in an interview

with Tom Spurgeon at comicsreporter.com. Safety and crowd comfort were the

guiding principles. Glanzer estimated that around 50,000 people were milling

around on-site each day, and with that, the show has reached its limit at the

massive San Diego Convention Center, so it’s not likely to grow any for the

next five years, through 2012, the last year it’s booked in the facility. So

far. I don’t know whether management will seek another venue or not; not many

facilities in that part of the country are larger than the San Diego Center.

Otherwise, rumors to the contrary notwithstanding, Sandy Eggo is not likely to

try to get around its space limitation by adding a day to the show: that’s too

expensive—for everyone, exhibitors and attendees and the show itself. But,

Glanzer said, they’re considering other strategies, such as adding off-site

programming. Another rumor Glanzer shot down: Artists Alley was not smaller

this year than last. Although it was smaller in the planning stages, at the

last minute, said Glanzer, “We were able to move the Art Auction upstairs to

the Sails Pavilion so we didn’t lose any tables. ... In fact, I believe we

increased space by about 25 tables over 2006.”

Glanzer

also attempted to unhorse persistent complaints that “we’ve left our roots” in

comics for the allure of Hollywood. He was less persuasive here. Yes, from the

beginning, as he said, the Con has included science fiction and movies. Shel

Dorf, who inspired a knot of teenagers to found the Con in 1969, came West from

Detroit, where, in July 1965, he’d been among the founders of the Detroit

Triple Fan Fair, a two-day meeting for fans of fantasy literature, movies, and

comics. But over the years, one leg of this three-legged stool upon which the

Con rests has grown more than the others, creating a wholly lopsided

contraption, Hollywood’s big budgets crowding out all other considerations.

Spurgeon said he’d talked to several “medium-sized” exhibitors of comics who

said they were seriously considering not returning next year. Floor space

devoted to comics in the cavernous exhibit hall has remained about the same

year after year, but the acreage devoted to movies, tv, games, and toys has

steadily increased, and for the last several years, comics have been dwarfed by

these other aspects of the show.

When

Dorf was still active in the management of the Con, newspaper cartoonists were

always a highly visible presence at the Con. Not any longer. For most of the

past several years, only one newspaper cartoonist got Guest billing. This year, Morrie Turner of the celebrated

inter-racial strip Wee Pals and

political cartoonist Daryl Cagle served their turns. And the iconoclastic Aaron

McGruder had a session on the program, as did several cartoonists

representing the National Cartoonists Society. But newspaper cartooning usually

gets short shrift at Sandy Eggo. I admit that I felt not a little miffed this

year by the lack of attention accorded Milton

Caniff (chiefly, I confess, as it affected his official biographer). Caniff

was one of the Con’s “themes”: the 100th anniversary of his birth

was ostensibly being celebrated. It seemed an appropriate gesture: Caniff’s

influence on cartooning was immense. As Caniff’s biographer, I offered to do a

session on the art of storytelling in comics as he had refined and improved it,

relying upon my just published “definitive biography” (Caniff’s term) of

Caniff. Of course, I was flogging the book—just as Hollywood producers flog

their movies and everyone else on the program at the Con is selling their

product. That’s what program events do at the Comic-Con. But my offer to do a

session was declined. I was on the program once with a panel about the current

enthusiasm for reprinting vintage comic strips (Dick Tracy, Pogo, Peanuts, Dennis the Menace, Gasoline Alley, even Terry and the Pirates) and a second

time for a session about the “Steve Canyon” tv show of the late 1950s, where

the producers of a DVD collecting all the shows flogged their product. Neither

of this events spoke to Caniff’s cartooning genius, the only reason for

celebrating him at a comics convention. Nothing on Terry, Caniff’s pace-setting masterpiece.

I

was miffed, as I say, until I noticed that there wasn’t a single session on Herge, the creator of Tintin, who was

also a “theme” of the Con (the 100th anniversary of Herge’s birth,

too). But there were six sessions on “Star Wars” (Friday was “Star Wars Day”).

Single sessions commemorated other “themes”—Robert Heinlein, Grendel, Groo (his

25th), the Rocketeer (ditto), and for the 25th of Love and Rockets, two sessions, one for

each of the Bros Hernandez. Roy Thomas, a pace-setter in comics and an enduring

presence, was featured at two sessions. (I was delighted to learn, in a

subsequent conversation with Roy, that my suspicions about the Spider-Man newspaper strip were correct:

Stan Lee doesn’t write it. Roy Thomas does. Or, as he puts it, he “helps” Stan

Lee. He assured me that Lee approves in detail everything he, Roy, does with

the strip and sometimes makes adjustments or changes.) Surprisingly, given its

emergence in recent years, there wasn’t much on the graphic novel; nor was

there a depressing amount of programming given to manga. Lots on toys. Specialties I never imagined: the Ball-jointed

Doll Collectors had a meeting. And porn star Jenna Jameson was in attendance.

She

was there to promote her comic book. Here’s Scott Huver’s take at nypost.com:

“Showing up at the San Diego Comic-Con in a cleavage-friendly and belly-baring

ensemble that threatened to cause heart failure among hefty comic book guys

whose primary idea of a sexy night in bed is reading a yellowed copy of Josie and the Pussycats, the world’s

most famous porn star unveiled her latest entrepreneurial effort, the comic

book Shadow Hunter, a five-issue

mini-series due in 2008 that casts her as a sultry, supernatural enchantress

who uses a wicked sword—and possibly the occasional Reverse Cowgirl—to battle

the forces of evil. Published by Richard Branson and Gotham Chopra’s

celebrity-centric Virgin Comics line (insert obligatory ‘Jenna Jameson’ and

‘virgin’ joke here, and then insert second joke about the use of the word

‘insert’), Shadow Hunter is a dream

project for Jameson, who loves the idea of mixing demonic duels and double-Ds.”

The book’s creative team has not been named yet, but Jenna is enthused about

the book, which, she said, won’t shy away from her hardcore history.

To

hear her tell it, Jameson has always been aware of a “crossover” appeal linking

comic book readers and porn movie fans. Said she: “It’s all a matter of the

fact that as human beings we love fantasy ... whether it’s fighting legions of

zombies or being sexual, it’s the same sort of thing.” Well, not quite. She

might have referred to those “hefty comic book guys” reading Josie and the Pussycats for sexual

excitement, but, no—she’s trying to move into the mainstream. She doesn’t do

movies anymore; instead, she’s capitalizing on her celebrity as many other

celebrities, from Martha Stewart to Cindy Crawford, do, launching a series of

products in her name—a fragrance, a clothing line (called “Hello Jenna”), and a

lingerie company. She’s also in pre-production for a movie based upon her book, How to Make Love Like a Porn Star,

which will be called “Heartbreaker” and may star Scarlett Johansson as Jenna.

Negotiations are still in progress. Jenna’s big on “sensitivity” these days and

likes Johansson for the part because she can “bring some depth and she’s kind

of dark.”

Jenna

wants the movie to be an authentic treatment of the porn movie business, not a

“complete fabrication” like “Boogie Nights.” Jenna’s movie, she says, will be

“one hundred percent reality”—even explicit. “It has to be. Not because we want

to draw male fans [but] because I want to tell the true story.” The true story,

according to Jenna, is that “I turned something that was an industry that was

completely unaccepted by America into something that is widely accepted now.

And I think that writing my books changed things for a lot of women to accept

their sexuality and be more powerful in a way.” Apparently, she doesn’t think

that the Internet with its proclivity for delivering porn in the privacy of

one’s home had anything to do with the current boom in porn. Moreover, “because

even though I’m a porn star, I think that ... I’ve been so successful because

people can relate to me and then can see themselves dating me or being my

friend.” She is, indeed, a fantasist. She expects to star in whatever movie

results from the comic book Shadow

Hunter, and she’s looking forward to the chance to show off her athletic

talent: “I’m so athletic,” she said. “I can’t wait to do the whole—I’m a

gymnast, so I can kind of show off all my talents, finally.” All her talents.

Show them off.

Yes,

movies and Hollywood and popular culture generally have been a traditional part

of the Comic-Con mix, but not to the virtual exclusion of comics and

cartoonists, which, alas, is the quo of the present status.

Son of Pithy Pronouncements

“My

life is a performance for which I was nver given any chance to rehearse.”

—Ashleigh Brilliant in Pot-Shots

“One

of the very nicest things about life is the wayk we must regularly stop

whatever it is we are doing and devote our attention to eating.” —Luciano

Pavarotti

“About

the only thing that comes to us without effort is old age.” —Chef Gloria Pitzer

EDITOONERY

Afflicting

the Comfortable and Comforting the Afflicted

Heads continue to roll out of the nation’s newspaper

editorial offices. Craig Terry, who

for 18 years was the editorial cartoonist and graphics editor at the Northwest Florida Daily News, was

relieved of his position on August 24. It was a cost-cutting maneuver, and it

involved several other staffers, mostly from advertising. Adding insult to

injury, Terry and the others were given no notice in advance but, when told of

the decision, were immediately escorted from the building like so many

criminals. A perp walk for an editooner. Terry had to get his former assistant

to retrieve from his computer his freelance contacts and family photos, music,

and other personal data. ... On the other coast, Mike Shelton was fired last October at the Orange County Register after 24 years; he continued doing cartoons

for distribution by his syndicate, King Features, until recently, when he

stopped editooning altogether to concentrate on Internet animations. ... The San Antonio Express, which was one of

the few papers in the country with two editorial cartoonists, one liberal and

the other conservative, fired Leo Garza,

the conservative, in August; John Branch stays on. While budgetary considerations may have been a cause, the newspaper’s

management offered no reason for choosing to fire the conservative. Matthew

Sheffield at newsbusters.org wrote the paper, asking for an explanation, and

received a bland, fact-devoid response, blathering about “the numbers” and

asserting that it was “a judgment call.” (“Judgment calls,” by the way, used to

refer to a decision reached in an emergency situation where the decider had no

time to deliberate; now, at the San

Antonio Express and everywhere else, it means, simply, “it is our

opinion.”) Sheffield was outraged and wrote back: “A ‘judgment call?’ ‘About

the numbers’? What does that mean? You provide no specifics which gives you no

credibility. Don’t you find it the least bit hypocritical that you are refusing

to disclose your decision-making process when you routinely publish editorials

demanding that government and other businesses do just that? How are you doing

anything but using the ‘unfettered power’ (your phrase for the Bush White

House) you have over your editorial page without having the respect for the

public opinion to explain yourself. You owe it to the public to explain your actions

with more than peremptory phrases and dismissive language, especially as a

member of our self-appointed ‘fourth estate.’” What, indeed, about the

“public’s right to know,” which is so often invoked to support a journalist’s

mission? No response from the Express yet.

Finally,

to commemorate Fred Thompson’s entry into the Presidential Stakes, here’s Holbert at the Boston Herald, picturing the “Law and Order” D.A. making his

announcement on tv, saying: “I’m running for President ... well, to be honest,

I’m walking briskly for President. Some might even say ‘sauntering’ for

President. A pleasant stroll ... meandering ...”

THE FROTH

ESTATE

The Alleged

News Institution

Just when we thought the practice of journalism could

get no more trivial, Rupert Murdoch, notable right-winger and the last of the press barons, successfully bullied his

way into sacrosanct precincts of the Wall

Street Journal by throwing his money around and buying the paper. This

aroused consternation in the Froth Estate, most of whom still, despite the

tabloid myopia of their own journalistic efforts, respect what they perceive as

the superlative reportage going on at the WSJ.

While it’s true that the Journal was,

and may still be for all I know, a model of thorough-going objective journalism,

some commentators saw little to wring hands over: the Journal, they averred, had long ago abandoned journalistic

excellence in favor of improving its bottom line. And Michael Wolff in Vanity Fair even found something to be

happy about in the Murdoch acquisition. Say what you will about Murdoch’s

penchant for sensational news and topless bimbos on page three of his

papers—not to mention his desecration of the London Times (which, he assured the newspapering fraternity when he

bought it, he would not corrupt—then proceeded directly to corruption)—Murdoch,

Wolff said, “is the only media conglomerator who has any interest whatsoever in

print.” Moreover, “the unique thing about Murdoch as a newspaperman is that he

is, truly, the only one of his kind to understand that, to survive, he had to

get beyond newspapers—way beyond.” And so he has done exactly that. But, said

Eric Alterman in The Nation: “Examine

any Murdoch newspaper—or book publishing or network news operation for that

matter—and you will find any number of clear, inarguable abrogations of

journalistic principles in the service of the immediate interests of Murdoch’s

corporate empire. ... Whatever actual news the media properties report is

almost beside the point. When news values and business interests clash,

business wins. ... Business always wins.” And sometimes in the interest of his

businesses, his news vehicles support even left-leaning politicians. “It’s not

that Murdoch is open-minded,” Alterman says, “—it’s that he’s single-minded.”

Given Murdoch’s complete disregard for ethics of any sort, journalistic or

whatever, I worry about how he will bend the WSJ to work his will in China, where he has extensive interests.

Or, rather, how he will subvert the legendary WSJ objectivity in order to improve his investment posture in

China. That, I’m sure, is his objective in buying the paper.

LAND OF MY

YOUTH

Denver, land of my youth and now the precinct of my

dotage, was, until not too long ago, one of the last two-fisted two-newspaper

towns in America. The so-called cross-town rivalry (the papers’ offices were

actually just a few blocks apart downtown) took shape as a sometimes frenzied

contest for circulation, the Rocky

Mountain News and the Denver Post each striving mightily to drive the other out of business. This robust symptom

of journalistic enterprise disappeared a few years ago with the inauguration of

a Joint Operating Agreement that now joins the two papers at the hip. In

theory, they are still rivals, still scrapping for each other’s readership.

That, after all, is the objective of the legislation that created JOAs—to

preserve newspaper competition, and hence the quest for Truth, in cities where

more than one newspaper have survived the modern age. JOAs re-arrange two

newspaper operations to reduce the expense so that both newspapers can persist.

The papers use the same presses and printers, hence cutting production cost,

and they share in advertising revenues according to some fantastic and

ingenious formula, but they maintain separate and independent editorial and

newsroom staffs, thereby preserving the illusion that a competitive edge still

exists. In Denver, the Post and the News (which calls itself “Rocky”) even

occupy, now, the same building, a brand new edifice in downtown Denver, overlooking

the historic City Center Park.

Despite

the good, even commendable, intentions that inspired JOAs, few successful ones

remain. Without researching the matter at all, I know of only three—in Denver,

in Seattle, and in Detroit. The editorial cartoonists I know in these cities

usually shrug and grimace when I ask them how their JOA is doing. In Seattle,

at last report, one of the partners to arrangement is suing to escape it,

alleging that the other partner is the greater financial beneficiary. Or some such.

Back

in the 1940s and 1950s when I was growing up in the city, the News was a morning paper; the Post, an evening paper. Now they both

appear in the morning. The chief manifestations of the JOA are that the

classified sections of the two papers are identical and the weekend editions of

the papers appear as a single publication. On Saturday, the front page is

flagged Rocky Mountain News, with Denver Post in smaller type; on Sunday,

the reverse. Whatever the grievances harbored by staff members of the two

papers, comic strip readers can have no complaints: both the Saturday and the