|

||||

|

Opus 139: Opus

139 (June 6, 2004). We begin with

a report on the Reubens Weekend of the National Cartoonists Society

that includes not only a complete list of the winners but a few of the

bon mots flung about that weekend and a glimpse inside the jurying for

the awards. We conclude with a review of two Gil Kane books, Blackmark

and Space Hawks-by turns, a ground breaking graphic narrative form and

a stunning visual narrative achievement in newspaper comics-and the

annual volume of the Best Editorial Cartoons of the Year (for the year

2003). In between, we consider the careers of two giants, Syd Hoff and

Gil Fox, who recently departed this vale, and the singular achievement

of a favorite, Jack Bradbury, also recently deceased. And we ponder

the future of the Comics Buyer's Guide, the new Disney postage stamps,

Scancarelli's misfortunes in plotting Gasoline Alley, and a few other

tidbits. It all starts next. ANOTHER BATCH

OF RUBES: NCS AWARDS FOR 2003. Strip cartoonists Pat

Brady (Rose Is Rose) and

Greg Evans (Luann) have been engaged, for the last six or seven years, in a competition.

It has been the least rambunctious competition in a world otherwise

mad with ferocious contentions: both contestants are low-key and respectful

of each other's work. They are even friends, each wishing the other

well. The competition has been so unprepossessing that few, probably,

even realized that it was going on. And now, with the presentation of

the National Cartoonists Society's Reuben for "cartoonist of the

year" to Evans, this noncombustible rivalry has ended. Brady's

nomination this year for the NCS's ultimate honor was his seventh consecutive

nomination; it was Evans' sixth, albeit not consecutive. Thus, the two

have been facing off for at least the last five years that I know of,

perhaps for all six of Evans' nomination years. And every year until

now, they both lost to someone else. The

presentation of the Reuben, a weighty statuette named for its legendary

creator and a founder of NCS, cartoonist Rube

Goldberg (who thought, when he was sculpting the object, that he

was making a lamp stand), took place in Kansas City at the annual banquet

on Saturday, May 29, during the weekend's traditional round of seminars

and cocktail parties and other tomfooleries. When he was announced as

the winner, Evans, one of the Betty's

bubbling happiness contrasted beautifully (dare I say "comically"?)

with her husband's quiet demeanor, a fittingly humorous culmination

to an evening of honors conferred and gratitudes extended. Earlier in

the evening, Jules Feiffer -cartoonist, children's

author, novelist, playwright, and perceptive chronicler of the medium's

history as well as of society's foibles-had received the Milton Caniff

Lifetime Achievement Award, named for the last great gentleman of the

comics, creator of Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon (not to mention Miss Lace).

That afternoon, during his presentation at one of the Saturday seminars,

Feiffer had reviewed the history of his love affair with comics and

speculated upon the future of the artform. Newspaper comic strips may

shrink out of existence, he said, but the form will reinvent itself;

words and pictures are part of our very nature, and that combination

will survive. Publisher John McMeel, co-founder of the Universal Press

Syndicate and Andrews McMeel Publishing (the industry leader in publishing

comic strip reprint volumes), was also summoned to the podium to be

presented with the Society's Silver T-Square for his long service championing

the profession and the artform. Said McMeel, explaining his success

by way of extending a piece of advice: "Be sure to surround yourself

with people smarter and brighter than you are." Also

presented at the banquet were the NCS Reuben "division" or

"category" awards for cartooning in its various modes-comic

strips, comic books, advertising, animation, and so on. Division awards

are juried and selected by the seventeen NCS chapters on a rotating

cycle that moves a category around from one chapter to the next over

the years. (The Reuben for "cartoonist of the year," on the

other hand, is voted on by the entire NCS membership.) Since being one

of the final three nominees in a category is a mark of peer esteem,

I'm listing here all the nominees by category; the winner in each category

is marked with an asterisk (*). Newspaper Panel Cartoon: Vic Lee (Pardon My Planet), Mark Parisi (Off the Mark), *Jerry Van Amerongen (Ballard Street); Comic Strip: Brian Basset (Red

and Rover), Glenn McCoy (The

Duplex), *Stephan Pastis (Pearls

before Swine); Greeting Card:

Richard Goldberg, Gary McCoy, *Glenn McCoy (who won this category last

year, too-and, in Gag Cartoons; he's also won in Editorial Cartoons,

and you'll notice he was among the nominees for comic strips this year;

busy guy); Newspaper Illustration: Grey Blackwell, John Klossner, *Bob Rich;

Magazine Feature / Magazine Illustration:

Steve Brodner, *Hermann Mejia (of Mad),

Ralph Steadman; Advertising Illustration:

Pat Byrnes, *Tom Richmond, Bob Staake; Editorial

Cartoon: Mike Luckovich, Ted Rall, *Tom Toles (who, two years ago,

left Buffalo, New York, to take the legendary Herblock's chair at the

Washington Post; at the time, Toles remarked,

he was thrilled to be going to Washington, D.C., which, then, he regarded

as the best place to do editorial cartooning-so he was disappointed

when he realized that the President can't read); Gag Cartoon: Robert Weber, Dean Yeagle, *Jack Ziegler (veteran New Yorker 'toonist); TV Animation: Rob Renzetti ("My Life

As A Teenage Robot"), *Paul Rudish ("Star Wars: Clone Wars"),

Tom Warburton ("Code Name: The Kids Next Door"); Feature Animation: Sylvain Chomet ("The

Triplets of Belleville"), Eric Goldberg ("Looney Tunes: Back

in Action"), *Andrew Stanton ("Finding Nemo"); Book Illustration: Bucky Jones, *Chris

Payne, Ralph Steadman; Comic Book: Eric Shanower (Age of Bronze), *Terry Moore (Strangers in Paradise), who remarked, upon

accepting the award, that he was relieved that he wouldn't have to resort

to Plan B-"booze." The third nominee for the Reuben (not to

overlook the distinction in being nominated) was Dan

Piraro, his second consecutive nomination for his newspaper panel

Bizarro. Piraro has also emerged in the

last couple years as the Society's duty emcee: he presided over the

Reuben presentations and the Sunday evening festivisties, roasting veteran

Mell Lazarus (Miss Peach, Momma). The comic book division nominees at first included

Batton Lash for his self-published comic book, Supernatural Law; but his name was subsequently removed for reasons

explained below under "Lash Out." While

all the nominees, as I've said before (Opus 136), are sterling representatives

of their craft, these round-ups always include a few mild astonishments.

I'm surprised, for instance, that the categories of Newspaper Panel

Cartoon and Comic Strip include such hefty helpings of relative newcomers.

Van Amerongen has been doing outstanding work for years and his award

is certainly over-due; but his competition, Vic Lee and Mark Parisi,

have been working for only a few years. Similarly, both Glenn McCoy

and Stephan Pastis have been producing comic strips for only a couple

years, so Pastis's win is a signal achievement. Ditto Hermann Mejia

of Mad -brilliant, no question,

but his competition included such champions as caricaturist Steve Brodner

and that china shop bull, Ralph Steadman. At the same time, van Amerongen's

win and Jack Ziegler's confirm the Society's allegiance to quality,

whether newcomer or old timer, so even in my ostensible surprise there

is no alarm. The surprises thus validate the rigor of the awards system,

which, notwithstanding, NCS is continually working to improve even more.

(One step in that direction might be, I'd say, to resolve to give awards

in this medium of visual artistry only to manifestations that cannot

be accomplished by the use, day after day, of a half-dozen rubber stamps.) Membership

in NCS stands at a little more than 600, including 449 regular members

(those who earn more than half their livelihood by cartooning), 42 associate

members (who don't), 44 retired, and 73 over 80 years of age (who don't,

therefore, pay dues any more). Attendance in Kansas City was about 350,

including about 200 members plus their spouses and families. Now in

its 58th year (Beetle Bailey's Mort Walker, who, as unofficial dean of the profession, presented

the Reuben, noted that this was his 53rd Reuben banquet),

the Society was not expected to last long by some of the less sanguine

members of the profession in the year of its birth. How, these Cassandras

wondered, could any club last for long whose members were in fierce

competition with each other for newspaper clients and magazine sales?

But last it has-perhaps because the activities of the group have always

been mostly social with only a smattering of professional preoccupations.The

Reuben Weekend is typical: a jubilant succession of cocktail parties

and dinners, it also offers seminars on Friday and Saturday, usually

"power point" presentations (that used to be slide shows)

of a cartoonist's work which he or she accompanies with a quantity of

verbal patter or explication. These

festivities commenced with a panel of cartooners from the other side

of the globe led by James Kemsley,

the current president of the Australian Cartoonists Association, NCS's

"down under" counterpart, at 80 the oldest cartoonists club

on the planet. Kemsley, who produces the national icon, Ginger

Meggs, introduced his 'tooning mates, editorial cartoonist Peter Broelman, comic strip Swamp creator Gary Clark, and Sean Leahy,

ACA's "cartoonist of the year" and creator of the strip Beyond the Black Stump. They introduced

their characters and talked about cartooning in Australia. Next, Paige Braddock, who produces the online

and comic book Jane's World,

introduced Patrick McDonnell

-who represents, she said, "everything that is good about comics."

And the Mutts master talked

about his love affair with the medium, with the way words and pictures

blend to yield unique meanings.

Mad's Nick Meglin introduced

Mad's Mort Drucker, who explained his life's work as one of the medium's

foremost caricaturists as a continuing effort "to be the best that

I can be" without imitating others, no matter how much he admired

them. He warned against the sort of rote creativity that occurs once

a cartoonist has reached that plateau where his/her performance has

achieved "a certain polish." He admonished: "Keep learning

and experimenting." Greeting card maven Sandra

Boynton, who, against all odds, revolutionized her industry, gave a hilarious and warmly humane presentation consisting largely

of a recitation of how she learned to create and operate a "power

point" presentation, illustrated by the power point presentation

as she talked. She began by asserting, unequivocally, that "I became

a cartoonist so I would never have to speak to a group-ever." Then

she demonstrated her complete mastery of the mode, every gesture and

head wag a comedic nuance. And when there were no more questions to

answer, she flashed a smile and quickly brushed her hands together in

a gesture of finality. Beautiful. Jules Feiffer resorted to the traditional

slide projector in revisiting the comics he'd fallen in love with as

a youth. And he remarked about various stages of his own career. About

the motion picture he wrote, "Carnal Knowledge," he observed

that no one, not even he, expected any actor to perform the role that

Jack Nicholson took on. It was an impossible assignment. But Nicholson,

Feiffer said, did more than anyone could wish with the part. Feiffer

later asked director Mike Nichols what he'd done to get Nicholson's

performance. He hadn't done anything, Nichols said: Nicholson came up

with it all by himself. The

parties began with a Friday afternoon visit to the offices of Universal

Press Syndicate, headquartered in Kansas City, where a small ensemble

of musicians and several pitchers of martinis assured that we got "Jazzed

with Jules," in recognition of Feiffer's long and distinguished

career. After an evening of more cocktails and heavy hors d'oeuvres,

a karaoke contest in the Fairmont Hotel's rooftop bar concluded the

day. Sunday evening was set aside for more liquid libation, hors d'oeuvres,

and the "roasting" of Momma's Mell Lazarus. Dan Piraro was,

once again, a polished emcee of the shenanigans. But his long-time predecessor

in the role, Family Circus' Bil Keane (who had given up an 'l' in

his name so that Mell could have two), most consistently achieved roars

of laughter. An accomplished deliverer of one-liners, Keane started

off with a classic: "As a rule, we roast only people we love,"

he said-"but tonight, we make an exception." This was followed

by an explosion of Keane's supreme achievement, rambling meaningless

double-talk, and several of Lazarus's closest friends, one of whom said,

"We don't get Momma. We see it every day: we just don't

get it." Cathy's Cathy Guisewite regaled the assembled

multitude with an account of her one and only date with Lazarus, an

encounter so bleak and humiliating that it made her career: "In

one unforgetable evening," she said, "Mell took a tiny spark

of insecurity in me and turned it into a 28-year career of neurotic

obsession." Lazarus, as is the custom for the roastee, had the

last word, a chance to zing every one of his pesterers. And he managed

the assignment with aplomb, beginning: "You promised you wouldn't

tell any funny jokes at my expense-and you kept your promise."

He emerged with more dignity than some of his roasters. But that, I

ween, is the object of the exercise. On

Sunday afternoon when nothing else was on the NCS schedule, several

of us joined Dan Viets on a tour of the Walt

Disney sites in the city. Disney lived in Kansas City from 1911

until he left for California in the summer of 1923, and the little two-story

house he and his family lived in for most of that time is still standing,

still occupied; and in the rear is, still, the garage young Walt helped

his father build and later used for his earliest experiments in animated

cartooning. The building in which he rented offices for his Laugh-O-gram

business is also still there, albeit about to fall down. Viets and his

associates have purchased the property and propped it up while they

raise more money to restore the building and turn it into a Disney museum.

Viets is one of the authors of an amply illustrated record of the famed

animator's early life, Walt Disney's

Missouri (200 9x12-inch pages, slick paper in hardcover; Kansas

City Star Books, 2002, $34.95; www.kcstarinfo.com

or phone StarInfo 816/234-4636), an impressive tome, which, as guide,

Viets had so memorized as to make him a walking encyclopedia. And speaking

of informative tomes, if you want to know more about Milton Caniff and

why NCS named its Lifetime Achievement Award after him, click here

to be transported to a description of Milton

Caniff Conversations, a book I edited. For Rube Goldberg's role

in all this, click here to be transported

to our Hindsight Department where he's listed among the features. LASH OUT (adapted from a report in

the online Comics Journal).

Batton Lash's self-published Supernatural Law was subsequently dropped from the award nominations

list after the initial announcement on the NCS website. A few weeks

after the posting, Lash and his wife, co-publisher and editor Jackie Estrada, received an e-mail from

NCS board member Greg Evans

that explained the disappearance of Supernatural

Law: Estrada had served as a judge on the Comic Book Division selection

committee, a circumstance that could be interpreted as a conflict of

interest. Said Evans: "The

NCS board decided to omit Batton as a nominee in the Comic Book Division.

The board felt that Jackie's position as a judge and her involvement

with the books could be seen as biased and inappropriate. So to maintain

the integrity and fairness of the awards, Batton was removed. Just wanted

to be the one to tell you before you heard it elsewhere. I should have

been more diligent at the judging and not allowed Batton to be considered.

I've accepted full responsibility for not catching it before it went

this far." Lash

and Estrada were unwitting and innocent bystanders in the NCS's continuing

effort to improve the standing of its awards. Although many of the NCS

division awards are juried by NCS chapters, the Society's membership

is predominantly syndicated cartoonists. In an effort to make sure that

all nominees represent the best work being done in their category or

division, the NCS board has in recent years gone outside the chapter

membership to find competent juries in such divisions as animation and

comic books. At the board's behest, Evans, a member of the Southern

California Cartoonists Society, the venue of which is, roughly, Next

year, the comic book selection is likely to move to a different NCS

chapter, following the practice of periodic rotation from one chapter

to another. NOUS R US. Fantagraphics' first volume

of the proposed 25-volume Peanuts

reprint project hit the New York Times Hardcover Bestseller List

, debuting at 19th place on May 23. ... Paul

Dini, who has been producing a number of elegant comic book projects

for the last several years, left Warner Bros. Animation on June 1, concluding

("at least for the foreseeable future") a 15-year career there.

In a farewell note on his www.jinglebelle.com

site, he said he'd miss working on "great projects with a truly

gifted assortment of artists and writers," but other projects beckon:

"I look forward to doing more live feature film writing, more comic

book writing (my own characters and others) and generally stretching

myself in other creative areas." ... Editoonist Jim

Larrick has been replaced at the

Columbus Dispatch by Jeff Stahler, who leaves the Cincinnati Post without an editorial cartoonist.

Larrick, who has been the staff cartoonist at the Dispatch for 22 years, will continue on

staff in the art department. No specific reason was given for the decision.

Larrick's cartoons are more in the reportorial mode than adversarial,

reflecting "conventional wisdom" on issues. And Larrick isn't

syndicated. Stahler is. Mike Curtain, associate publisher at the Dispatch,

referred to Stahler's "national reputation" in announcing

the hire; he was also complimentary about Larrick, saying that the veteran

cartoonist has "the talent to do other things." ... I just

received my second Harvey Awards ballot; and I've already received two

for the Eisners. I guess that means I could stuff the ballot boxes,

voting for my favorites twice twice. ... This month, Disney creations

finally make it to postage stamps. Mickey Mouse was conspicuously absent

from the Postal Service's comics commemoratives of 1995, but now the

Ubiquitous Rodent and his crew are comin' on strong. On June 23, the

four new 37-cent stamps will be available only at Disneyland at Anaheim,

California; the next day, the stamps will go on sale at all post offices.

The stamps ostensibly honor "Friendship," not cartoon characters,

and each stamp depicts one set of Disney's classic buddies: (1) Mickey,

Goofy and Donald Duck symbolize the perfect fun-loving relationship;

(2) Bambi and Thumper, childhood best friends; (3) Pinocchio and Jiminy

Cricket, mentoring; and (4) Mufasa and Simba (the only "new"

friends among these classics), parent and child bonding. To see the

stamps, visit www.usps.com/shop

and click on "Release Schedule" in the Collector's Corner.

CIVILIZATION'S

LAST OUTPOST. The New Yorker published, in its "Sketchbook"

in the April 15th issue, a page of Saul Steinberg's drawings, colored pencil

mostly. Steinberg has done some brilliant work over the decades, but

this page isn't among that crop. In the past, a facile pen has often

rescued otherwise infantile scrawls, but it's the line that rescues,

not the composition or conception. Here without a looping line in sight,

we have little more than childish doodles. Not everything Steinberg

does is a masterwork, aristotle. Same with the other graphic genius,

Picasso, who, legend has it, once tried to pass off as a work of art

just his signature. A 14-year-old

California animator was marched out of his schoolroom in handcuffs on

May 27. The miscreant, a student at the Walnut Creek Intermediate School,

had created an animated cartoon that his mother claimed was in the style

of South Park. Circulated on the Internet, the cartoon commented on

the boy's teacher calling him "a good looking peacock," a

remark apparently not intended as anything but playful allusion to the

kid's self-confidence. The boy heard "pee" and "cock"

and produced a cartoon in which he says: "He called me a good looking

pee-cock. Maybe I should kill him and urinate on his remains."

The school, which, like many in these post-Columbine years, has a zero

tolerance policy on violence or the threat of same, allowed itself no

choice, the school board president said, but to treat the "threat"

seriously. So the cops showed up. (Maybe a SWAT team, but it doesn't

say here.) The boy and his mother were upset that he was handcuffed

in front of his classmates, but the mother is most upset that the school

didn't phone her to tell her what they were about to do. Ahhh, the times

we live in. If permitted. In

San Francisco's free speech bastion, North Beach, Lori Haigh put a provocative

painting in the front window of her gallery on Powell Street. She'd

displayed other unconventional works before-that, after all, was actually

conventional in the venue of the Beat Generation. But this one, a rendition

of the torture of Iraqi prisoners by Guy Colwell, provoked more than

thought. Haigh started getting hate calls and threats, and her gallery

was vandalized, malcontents egging its exterior and dumping trash in

the entrance. A single mother, she closed the gallery, disillusioned

and frightened for her two children. San Francisco's avant garde community,

however, hoped to persuade her to re-open. Famed Beat poet and City

Lights bookstore owner Lawrence Ferlinghetti called the reaction to

Colwell's work "an alarming development" fostered by a growing

attitude nationwide that dissent must be suppressed. Haigh, although

not supportive of the invasion of Iraq, is not a crusader, she says.

She's torn between her desire to defend Colwell's artistic vision and

her need to preserve her business. But when callers started threatening

her children, she gave up. "I wish they would aim their criticism

where it belongs, at the military," she said; "but I can't

sacrifice my family for principles." GOOD-BYE CBG. Issue no. 1594 of The Comics Buyer's Guide is a keepsake

here at Rancid Raves Central: it's the last weekly issue of a newspaper

that's been weekly for over three decades. Alan

Light, age 17, launched it as The

Buyer's Guide for Comic Fandom in February 1971. With twenty pages

of ads, it went to 3,600 "subscribers." It was monthly at

first, but within a year or so, it was coming into my mailbox every

week. I'm not sure why the current management of CBG

decided to go back to a monthly publication schedule. A monthly publication

will be more humane: staffers can get a day off easier, I'd guess. But

the size of the new monthly "magazine," a huge page count,

is daunting. The magazine format itself was doubtless part of the temptation

to go monthly: slick stock, color pages, all that. Most editors are

easily seduced by the high production values usually associated with

magazine publication, and in a field in which graphics are paramount,

the appeal is just that much greater. And probably Krause, the publisher,

couldn't afford to staff for a weekly magazine; so if the publication

would take magazine form, it would have to be on a monthly basis. A

monthly magazine may, indeed-as proclaimed-give its readers "more"

in the way of in-depth articles and nifty illustrations. The page-count,

as I said, is impressive. Then there's the "price guide" aspect

of the enterprise. I haven't researched any of this (that is, I haven't

read extensively in CBG's

prospectus or anything like it), but my guess is that the new magazine

will include more "data" on comic book prices, their so-called

values. It will become, more and more, a publication for the most fanatic

speculator collectors, those who can barely stand to hold their comic

books in their hands for fear they'll somehow damage the things by imparting

to them a microscopic patina of palm sweat. The new monthly CBG

may be running head-to-head competition with Wizard;

sure seems that way. And I suppose the chaotic layout practices of the

Wizards will insinuate themselves into the new publication. But

for all the appeal of a slick magazine format, I suspect that advertising

was the clincher in deciding to go monthly. The weekly paper has been

for the last few years fairly consistently about 50-60 pages in scope,

a size determined more by the number of pages of ads than by the amount

of editorial material available. Compared to the size of CBG

a decade or more ago (when 100-page issues were almost common),

I suppose the publisher was diligently casting about for a way to improve

the advertising side of his equation. Dunno how the balance sheet works

out, but my guess is that the Powers That Be are convinced their advertising

revenues will go up with monthly publication. Whatever

the appearance and content of the monthly CBG,

though, I'll miss the weekly paper. I gave up reading it cover-to-cover

long ago, but as a potential vehicle for fast-breaking news, the weekly

was a boon. No other publication in fandom could cover developments

on a more timely basis. While the online version of CBG

promises to perform than function, it won't be the same as that

package in the mailbox. Hasn't been so far anyhow. But we'll see. I'll

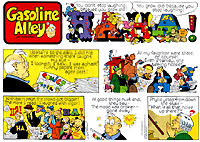

be looking forward to getting No. 1595, the first of the monthly onslaught. STRIP WATCH. In Gasoline Alley, the mystery that Walt Wallet's wife Phyllis ("Auntie

Blossm") promised to solve-explaining why Skeezix's mother left

him on Walt's doorstep 83 years ago-was being solved last week, even

though Phyllis died a month ago, ostensibly taking the secret with her

to the grave. Phyllis' death came after cartoonist Jim Scancarelli had carefully created the suspense about Skeezix for

several weeks. Her death ought to have prompted a great outcry of frustration

from Alley fans who were,

presumably, hanging on tenterhooks awaiting the revelation. Having primed

the pump, Scancarelli is too good a storyteller to disappoint us: on

May 20, he returned to the mystery and started unraveling it. Skeezix,

looking among Phyllis' effects, finds old letters from his birth mother,

Madame Octave-who, it turns out, is Phyllis' sister. Pregnant and abandoned,

for all practical purposes, by her philandering husband, Octave, a professional

singer, could scarcely cart a baby around with her, so she left her

son with ol' Walt, a bachelor at the time but one who, in sister Phyllis'

opinion, would make a good parent. And Walt lived only a couple doors

away from where Phyllis was living then, so Phyllis could keep an eye

on her sister's offspring. At the time, Phyllis was known as "Auntie

Blossom," a widow; eventually, she and Walt married. And she became

Skeezix's "mother" (although she was actually his aunt). Octave

couldn't leave the baby with her sister, Phyllis, because Phyllis was

a widow and a scandal would ensue if she suddenly turned up with a newborn

baby. In explaining this last scrap of intelligence, Scancarelli nearly

violated the strip's continuity. He'd forgotten, apparently, that Phyllis's

husband, a soldier named Jack Blossom, had been killed; he thought the

two had divorced. At the last moment, though, his memory was jogged

(by me, actually-aided considerably by Bob

Bindig), and he phoned a correction into his syndicate, Tribune

Media Services. In the strip for May 29, Walt's speech balloon in the

last panel has been altered. Originally, he said, "Phyllis was

divorced ..."; but Scancarelli changed "divorced" to

"widowed," an adjustment supposedly made before TMS had circulated

the week's strips to client newspapers. Alas, it didn't quite work out.

Some papers ran one version; some, the other. And on this ethereal 'Net,

fans pondered the discrepancy: is Phyllis a widow or a divorcee? Whatever

the case, the confusion was inaugurated, briefly; now, here, cleared

up. Scancarelli

has been puzzling about the mystery of Skeezix's abandonment for months-years

maybe. And he had set himself the task of figuring out an explanation.

The strip's creator, Frank King, had introduced Skeezix's real mother,

Madam Octave, who kidnaped her son once (as Scancarelli rehearsed earlier

this year in a flashback sequence with Walt telling Skeezix about it).

But King never got around to explaining why Madam Octave abandoned her

child. Once Scancarelli doped out an explanation, he then staged the

last three months of painstakingly wrought prolongation, interrupting

the "main story" (the explanation of Skeezix's abandonment)

for the season's most sensational development, the death of a major

character, Phyllis. All very artfully arranged and deployed. But, as

the philosophical Scancarelli will be the first to admit, the best laid

plans of men as well as mice oft gang alay (as Bobbie Burns would have

it). Jim had deliberately conducted the death of Phyllis in a way that

led some readers to suppose it might have been Walt who died. And then

when it was revealed that it was Phyllis who had expired in her sleep

that night, the sensation of the revelation was overshadowed by another

comic strip event that week: in Doonesbury, B.D. lost his leg in Iraq.

Then in the midst of the disclosures of Madam Octave's letters, Garry Trudeau again sucked the oxygen

out of the media with a Sunday Doonesbury

in which he listed all 700-plus names of the U.S. soldiers killed in

Iraq. If Scancarelli ever figures out how to deal with 104-year-old

Walt Wallet, whose demise must be imminent, he may never actually execute

the plan for fear that Trudeau will upstage him yet again as he has

now formed the habit of doing. If

not Trudeau, then maybe Aaron

McGruder. The Boondocks, now

drawn by Jennifer Seng, is no less acerbic in attacking

the policies of the Bush League, but it's panels are now filled with

more drawing than before, when McGruder resorted to an endless parade

of talking heads. Now we see actual figures. And the manga influence

is much more readily discerned. In

Betty, a strip about a middle-aged self-reliant

and self-respecting lower middle class housewife and her husband Bub

and son Junior, Betty and Bub were at a newsstand earlier this week,

where Bub looks the crop of comic books. "I used to read Batman

and Superman," he says, "and also Dr. Strange, the Fantastic

Four, and the Green Lantern, but," he continues with an anticipatory

grin of pleasure on his face, "let's see what's new and exciting."

Says Betty: "Here's one about a bald guy who works in a mail room."

And Bub, looking suddenly somewhat glum, says: "This one's about

a dead guy." The next day (June 2), he decides to buy one about

"the usual-a lone hero who stands for what's right." Betty

decides to get something like that herself, she says, and heads for

the Oprah magazines. The visual staging for this gag is essential to its

comedy (see www.comics.com

). Bub and Betty are standing next to each other in the penultimate

panel in which Betty announces her intention to find "something

like that" to read herself. In the last panel, she heads off to

the right; Bub points in the opposite direction and says, "Um ...

the comic books are this way." Betty, pointing, says: "The

Oprah magazines are this way."

Betty is one of many contemporary comic

strips produced by a team, a writer and an artist. Gerry Rasmussen draws it, and Gary

Delainey writes it. But Delainey is as much the artist as Rasmussen.

They met while in college taking art courses. They were in a painting

class together. "After class we would get together with a group

that was interested in cartooning," Rasmussen said. "We'd

have some late night 'jam sessions.' We would make up characters and

different strips. We would each start a strip on a page, which would

be the first frame, and then we would pass it to the next guy. Some

of these sessions started off with as many as twelve people. Slowly,

Gary and I felt it was time to pool our resources because we thought

we were doing some stuff that was really interesting and we worked well

together. That's how Betty was

formed." Their mutual artistic inclinations have been important

to their successful collaboration. "The thing I've really enjoyed,"

Rasmussen said, "is that we both came from a visual art background.

When Gary writes, he writes in pictures so it's not something that I

really have to translate from a written idea. He conceptualizes it visually

from the start. One of the biggest stumbling blocks in doing good comics

is to always think in pictures. ... It's all got to be in the drawings."

Delainey agrees: "A lot of times I have to draw because the writing

itself would leave Gerry scratching his head. It has to be with the

appropriate pauses and camera angles in order to come off at its maximum."

Rasmussen's drawing style has about it a comfortable lived-in feel.

An antique nimbus hovers, making me think of E.C. Segar's Popeye

but only vaguely: Rasmussen's work is entirely modern-clean, uncluttered,

blacks adeptly spotted-but modeling notches cut at the edges of noses

and necks invoke the galoot manner of the masters. Nicely done. Back

to Bub and his comic books: in the first panel on June 3, he's reading

a comic book. In the next, he's scribbling on a pad of paper as he works

a calculator. In the third, he mutters, "I was afraid of this ..."

And he turns to Betty and says, "Using the current price of comic

books as an indicator of inflation, I'm making about the same income

today as I did when I had a paper route." Timing is all. SEND-OFFS. May's toll was pretty heavy:

the cartooning firmament lost three of its stars. On May 12, Syd Hoff, veteran New Yorker cartoonist and children's book author, died of pneumonia

at a In

1987, Hoff explained his niche to Jud

Hurd, editor of Cartoonist

PROfiles: "Harold Ross,

who was the founding editor of The

New Yorker, sort of made me the Bronx correspondent of the magazine

as far as the cartoons were concerned. He thought my style represented

or was catching the image of the Jewish people, mostly in the city of

New York. My cartoons expressed my natural feeling-the types of people

I was drawing were the people I had always seen all my life. The captions

echoed what I heard these people say. I felt that I was doing something

that came naturally to me. After a few years of this, it became apparent

that I had been typed. So they were buying only this kind of drawing

from me. I wasn't really thinking of trying to emulate, for example,

the kind of [dissolute upper-crust] characters that Peter Arno was doing.

From me, they were buying cartoons about these low-income group people

who lived in tenement houses and had problems with being able to hear

what the people next door were saying, and so on. This became my bailiwick,

the environment for my drawings. Occasionally, for other magazines,

I did cartoons involving Park Avenue types, but never for

The New Yorker. Ross was the only editor I really revered and the

one who 'discovered' me, if I can use that expression. I grew up in

the Bronx and the furthest I ever got from it was when I met my wife

who came from Brooklyn. It was an inter-city romance-we've been married

49 years but it seems like 19."

Hoff was heart-broken when his wife, Dora "Dutch" Bermann

Hoff, died in 1994, but he remained active, playing handball at Miami

Beach's Flamingo Park courts until he got skin cancer. Hoff

sold cartoons to virtually every major magazine, and in the 1930s, he

produced several cartoons ridiculing the moneyed classes for a socialist

magazine; these, he signed "A. Redfield" or "A.R."

Late in the decade, he joined the ranks of newspaper cartoonists: his

Tuffy comic strip was syndicated, May 6, 1940-September 2, 1950; and

he followed that with a daily gag panel, Laugh It Off, which ran from January 6, 1958 to January 8, 1977. In

the 1950s, he starred in a series of tv programs, "Tales of Hoff,"

in which he told a story and drew cartoons. His on-camera experience

was a direct result of his second career as author of children's books.

"I

sold Danny and the Dinosaur to

HarperCollins in 1958," Hoff remarked, "and suddenly, at 46,

I had a new career." The story of the towheaded boy who rides a

brontosaurus out of the natural history museum originated in the stories

and pictures Hoff drew for his daughter while she was undergoing physical

therapy to remediate a disability. It landed at HarperCollins in late

1957, just as Random House was contemplating the launch of its Beginner

Books series, ostensibly edited by another cartoonist, Dr. Seuss, whose

The Cat in the Hat had flown off the shelves at bookstores earlier

in the year. It was the dawn of the age of "learn to read the fun

way" books; Seuss's Green

Eggs and Ham, which he wrote when challenged to write a book with

a 50-word vocabulary, appeared in 1960. At HarperCollins, Danny

was among the first titles in that publisher's I Can Read series. Hoff

would eventually produce nearly 200 books for children, including some

that he illustrated for other authors. Said Hoff's editor: "Syd

was so good at humor for young readers and for creating big-hearted

characters. There is so much competition [in entertainment], but children

are still very excited to be able to read. That magic hasn't gone away." Most of the Hoff obituaries headlined the death

of a children's book writer, not a cartoonist. But the sensibility of

a cartoonist is akin to that of a good storyteller for children. According

to Eric Nash in the New York Times

obit, "Mr. Hoff's books are so successful because they clearly

link words and pictures"-a cartoonist function. Esther Peart, a

neighbor of Hoff's in Miami Beach, recalled going to Hoff's place and

listening to him read his books. "You could tell he had such a

connection with those books," she said. Peart, who has a 7-year-old

son who reads Hoff books, isn't surprised that kids like the books.

"Maybe it's the way he related to being a kid in his books. It

so outweighs all the bells and whistles and computer games," she

said. Hoff also produced a book on how to cartoon, Learning to Cartoon (1966 reissued as The Art of Cartooning in 1973) and an ambitious and mostly successful

illustrated history of editooning, "from the earliest times to

the present ... with over 700 examples from the world's greatest cartoonists,"

Editorial and Political Cartooning

(1976). Three

days after Hoff left us, two more cartoonists died, both on May 15.

Near his home in Redding Ridge, CT, Gill

Fox died at the age of 89. In recent years, he'd been producing

editorial cartoons for a local three-times-a-week Connecticut newspaper,

the Fairfield Citizen News, but his career ran the gamut of cartooning.

His first cartooning job was as an inbetweener with Fleischer Studios,

and when that outfit moved to Florida, Fox found work in the comic art

shops of Loyd Jacquet (1935) and Harry "A" Chesler (1936-37),

and he was an editor at Quality (1940-42), where (1939-43) he also drew

covers and such dissimilarly styled features as "Death Patrol,"

"Poison Ivy," "Slap Happy Pappy," "Wun Cloo,"

"Granny Gumshoe," and "Candy." He followed, and

deftly imitated, Bill Ward on "Torchy." He could draw expertly

in any style. In fact, he claimed he had no style of his own-but he

didn't mind: "All I can say is that I love to draw-no matter in

what style it is." He arrived at this enviable situation through

diligent practice. When learning to draw, he, like most neophyte cartoonists,

copied the people whose work he admired. "I used to lie down on

a studio couch with a huge pile of originals and reproductions of the

cartoons of a man whose work I wanted to study," he explained to

Jud Hurd (Cartoonist

PROfiles, no. 6, May 1970). "This takes a good deal of time

and I'd spend hours discovering the key to his style. There's a key

to everyone's style-you begin to notice repetitious patterns, the things

the cartoonist does, the tricks he uses, etc. And when, later, you're

trying to imitate him, you also have to maintain the mood that is associated

with his feature. ... I might add that a cartoonist who had developed

his own very definite style over a period of years would find it very

difficult or impossible to to develop this ability I've been talking

about. You see, when I started this method, I didn't have a style of

my own." During

World War II, Fox found a drawing billet on the base newspaper where

he trained and then, when shipped overseas to the European Theater,

he eventually wound up on the staff of one of the editions of Stars

& Stripes, the newspaper for the armed services. When he returned

to civilian life, he freelanced for Quality and tried to get on the

staff at Johnstone & Cushing, the legendary agency doing advertising

cartoons. Staff members at J&C were essentially on-the-premises

freelancers: they were given rent-free office space and had unfettered

access to equipment and materials in return for which the artist gave

J&C assignments priority over all other freelance work. Before being

invited to join the staff, Fox freelanced out-of-the-office for a time.

His first freelance assignment was a series of roughs for the Ex-Lax

account, the famous laxative of the day. Fox recalled the circumstance:

"Just about this time, I had been leafing through some book and

had noticed a photo of Rodin's famous statue, 'The Thinker.' And I worked

an idea for the Ex-Lax roughs using this figure. Believe it or not,

it never occurred to me until I showed the roughs to Jack Cushing that

the position 'The Thinker' was in made the use of that particular cartoon

impossible in an Ex-Lax ad. Cushing really broke up when it saw it." Once

on staff at J&C, Fox joined such luminaries as Dik Browne, Lou Fine,

Creig Flessel, and Stan Drake. But Fox was eager to get a syndicated

feature and spent his spare time conjuring up ideas for strips. He later

estimated that he produced 22 strip ideas in 25 years. Before the War,

Fox had briefly drawn a ersatz Chinese philosopher newspaper panel cartoon

called Ching Chow. In the early 1950s, he teamed with a radio and tv writer,

Selma Diamond, to produce a semi-straight story strip called Jeanie (1952-54). Jeanie was an aspiring

young actress who came to New York to make it big, and the strip dealt

with her breaking into show business. (Sound familiar? Leonard Starr made it big with another strip along these lines called

On Stage, which debuted in

1957. But Jeanie wasn't the

first ingenue strip; she was preceded by Dixie

Dugan and, even, Ella Cinders,

to mention a couple strips that focused on showgirls.) Subsequently,

Fox did a humor panel about a little kid who looks remarkably (and not

at all coincidentally) like Hank Ketcham's Dennis, Wilbert

(1954-59), and, nearly simultaneously, a Sunday strip, Bumper to Bumper (1952-63) before settling in with Side Glances, a panel cartoon that had

been originated by George Clark in 1930 and continued by William Galbraith

Crawford (who signed it "Galbraith") when Clark gave it up

in 1939. Originally, Fox had come in to substitute for Crawford when

the latter took ill; in 1961, Fox took it over himself and continued

it until it expired in 1982. After that, Fox did a variety of freelance

jobs and then, in 1990, started doing political cartoons for the Connecticut

Post; when that job evaporated in 1996, Fox found work for his crusading

pen at the aforementioned Fairfield

Citizen News. Looking back over his career in an interview reported

in Alter Ego no. 12 (January 2002), Fox said

he was proudest of his political cartoons: "I've gotten more satisfaction

from doing those than anything I've ever done," he told Jim Amash.

The same day, May 15, that Fox departed this vale in Connecticut, on the other side of the country, Jack Bradbury died in Santa Rosa; he, too, was 89. Bradbury was a veteran animator, who worked on such Disney film sequences as Bambi's stage fright, the Pegasus family in the original "Fantasia," and Figaro in "Pinocchio." But Bradbury's impact on my young imagination occurred through the funny animal comic books he drew stories for, ACG titles, mostly- Ha Ha, Giggle, and Coo Coo. Like other West Coast animators of the day, he moonlighted in comic books. Bradbury had been working at Warner Brothers for a couple years when Jim "Fox & Crow" Davis set up his shop to supply comic book art to such East Coast publishers as ACG, and Bradbury joined the crew of late-night laborers, sometimes actually working in Davis's offices. Bradbury also drew Beany and Cecil Comics in the early 1950s, but the characters I loved were the ones he wrote as well as drew-Spunky the Junior Cowboy and his talking horse, Stanley. Spunky debuted in Nedor's Coo Coo no. 22, February 1946, as "Spunky the Pronto Kid." Thereupon, he meets a stray cayuse named Stanley and discovers the horse can talk. Spunky got his own title under Standard's banner in April 1949, and Spunky ran for seven issues through November 1951. Bradbury told me he wrote them all as well as drew them and had a great time doing it. Apart from Bradbury's deft anthropomorphizing of the horse, I particularly doted on the way he drew characters when running. It was, I told him, "the Bradbury Dash," in which the characters were always bent impossibly far forward at the waist, elbows up high. They even walked with their elbows up-"the Bradbury Saunter," I dubbed it. Once witnessed, never forgotten. When I met him, he was already suffering from macular degeneration and had only peripheral vision. Gasoline Alley's Jim Scancarelli is also a big Spunky fan, and he drew Stanley in one of his Sunday nostalgic pages, July 28, 2002. He sent a copy of it to Bradbury, and Bradbury, using a computer with giant type, typed a letter back: "Months ago, our long absent friend Stanley was suddenly resurrected in a Sunday issue of your grand old Gasoline Alley. He was pleased as punch, clear out of his jug-headed gourd. Now I, his long suffering stable-mate, have a swell-headed nag on my hands who thinks he might also like to be in the movies. The old hayburner has apparently lost none of his desire to take advantage of every opportunity." In a subsequent exchange of correspondence, around Christmas 2003, Jim wished Jack and his wife, Mary Jim, the season's best and told him to say "Hey" to Stanley. Bradbury wrote back: "As per your instructions, I said 'Hey' to Spunky and Stanley, and you should have seen ol' Stan's ears perk up and his face brighten. 'Where?' he shouted, looking around expectantly while drooling a bit. He thought I'd said 'hay.'" Just for laughs and a lingering look at the Bradbury Dash and the Bradbury Saunter (not to mention a talking horse), here are a couple pages for Spunky and a copy of Scancarelli's Sunday page with Stanley giving us all the horse laugh.

The

cartoonists submit what they regard as their best work, up to five cartoons;

but the published selection often betrays the conservative bent (or

gentlemanly decorum) of its editor's Southern base, and for that reason,

some of the more liberal, or iconoclastic, cartoonists have often not

been well represented in past years. Some do not participate at all-the

acerbic Pat Oliphant, for example. Still, the series is the closest

thing to a year-by-year review of the work of the nation's editorial

cartoonists available; and in recent years, the decibels of the liberal

drumbeat have somewhat increased herein, providing balance and thereby

a much more representative glimpse of the temper of the times. The

current edition, for instance, is much less doctrinaire conservative

(or "decorous") than many of the previous volumes. That may

be due, largely, to the events of the year itself. The invasion of Iraq

was the principal happening of the year, and although it went quite

well, considering, until the "mission" was "accomplished,"

it very soon thereafter deteriorated into a fiasco of mismanagement,

becoming, thereby, a windfall for editoonists, who delight more in attacking

stupidity and pomposity than it championing brilliance and humility.

Cartoons on the Iraqi adventure, then, are understandably more critical

of the Bush League's policies than supportive. The

faltering economy and the on-going failure in resolving the Israeli-Palestinian

conflict also come in for lumps. As do news media excesses. The annoyance

and ineffectuality of Homeland Security and airport screening, however,

don't seem to rate as much attention as the suspension of NASA's space

program. The

book's chapters include, in addition to the Iraq/Terrorism section,

Bush Administration, Politics, Democrats, the Economy, the Media, Foreign

Affairs, and so on. The Bush Administration does not fare well in its

section; neither do the Democrats, although their section is much briefer.

(Assembly of the book begins in November, so the results of the race

for the Democrat presidential nomination aren't touched on herein.)

A glance

at the book's index provides statistical support for the contention

that liberal as well as conservative points of view are well represented.

In many of the previous volumes, cartoonists of a conservative bent

get all five of their submitted cartoons published; the more rampant

liberals, far fewer. But this year's index reveals that many of the

liberal persuasion logged in five cartoons this year. Visual

metaphors are the weapons of the editorial cartoonist, and the clout

of an editorial cartoon lies in the impact and duration of its imagery.

A memorable picture will presumably lurk in the minds of its beholders,

influencing their opinions forevermore. Steve Sack of the Minneapolis

Star-Tribune has emerged over the past couple years, generating

striking images with his stunning new pencil-shading technique. Here's

a picture of President Bush shaking an opened box labeled "Iraqerjack-WMD

Prize Inside," and when

nothing but crackerjacks falls out, Bush mutters to himself, "Dang."

By using a child's treat as his metaphor, Sack describes Bush's predicament

in terms that reduce the entire bellicose enterprise to a childish indulgence.

Sometimes

a good gawfaw is the best comment. Addressing the recall vote in California,

Scott Stantis of the Birmingham

News drew a three-panel cartoon: in the first panel, a Californian

is holding a baseball bat aloft and saying, "I'm mad as hell and

I'm not going to take it any more"; in the next panel, he hits

himself repeatedly on the head with the baseball bat; and in the last

panel, he's prone on the ground, and he says, "So there ..." The

book contains many more memorable images from the likes of Clay Bennett,

Dave Horsey, Kevin Kallaugher, Dick Locher, Mike Luckovich, Ed Stein

and more. It also lists the award winners in cartooning for the last

year and provides a cumulative list of the winners of Pulitzer Prizes,

the Sigma Delta Chi (National Society of Professional Journalists) Awards,

and Canada's National Newspaper Awards. In short, the BECY is, as always,

a handy source of historical information as well as an entertaining,

and provocative, review of the major events of the year. Marks of Kane. Two superb books of comic

book artistry rose up out of the mire of general mediocrity last winter.

Both feature the work of one of the medium's masters, Gil Kane. Kane had been drawing comic books since he was about 16

years old in 1941 or so, and by the time he got to 1977, he'd worked

for just about every publisher and had drawn the heroic human figure

in action in just about every genre of the medium. Then came Ron

Goulart and Star Hawks.

Apart from Calvin and Hobbes

in its latter-day Sundays, there has been only one shining example in

the last half of the century of the dramatic potential of cartoon strip

layout. And that was Star Hawks. Star Hawks

was drawn by Kane and written by Goulart, who created the feature. It

ran for only four-and-a-half years (October 3, 1977-May 2, 1981), but

it was the most imaginative innovation in the newspaper strip since

adventure stories invaded the funnies. Goulart furnished fast-moving

stories, crisp and economical scripting, and more than an occasional

flash of humor. This alone made Star

Hawks almost unique among its fellows, whose stories so frequently

must plod humorlessly along through an unruly undergrowth of verbiage.

But Star Hawks' toe-hold near

the pinnacle of note-worthy comic strips is best secured by its graphic

treatment. In format, Star Hawks was a two-tier strip: it occupied the space normally filled

by a stack of two daily strips. The notion of a double-decker strip

was Flash Fairfield's. Director of Comic Art for the Newspaper Enterprise

Association syndicate, Fairfield began toying with the idea of a space

adventure strip in the summer of 1976 (in other words, before "Star

Wars"). The double-truck format he saw as a way of putting life

back into the adventure continuity strip. "Basically,

we felt that continuity strips would never make it the way they've been

presented in recent years," Fairfield recalled in Cartoonist PROfiles: "they just don't have enough space. But with

the success of tv [serial] specials such as 'Roots,' 'Rich Man, Poor

Man,' and so on, we figured we could get back into the comic sections

and demand more space. If we got more room in which to operate, then

we could show newspaper editors how exciting a continuity could be if

it had this extra space, and could demonstrate to them that readers

would be receptive to the idea." Fairfield

ran into Goulart, found out he was a science-fiction writer, read and

liked some of Goulart's books and stories, and eventually enlisted him

to write the new strip. It was an inspired choice: not only was Goulart

an sf writer of years' experience, he was a collector and fan of comics

and author of numerous books on the medium. Goulart knew and understood

comics, and the Star Hawks stories reflected his thorough

grasp of the form's nuances. Goulart contacted friend and neighbor Kane,

and the creative team for Star

Hawks was born. Kane was as inspired a choice as Goulart. The two-tier

format of the strip opened up possibilities that would be most apparent

to someone accustomed to the more expansive format of the paginated

form. And Kane, as I mentioned, was more than a little accustomed. Kane

was clearly the artist for the assignment. And he, like most of his

generation, had "studied" the newspaper strip work of such early masters

as Harold Foster in Prince Valiant,

Alex Raymond in Flash Gordon, and Milton Caniff in Terry and the Pirates. He grew up on newspaper

adventure strips in the pre-war years when they occupied lavish amounts

of space. And he, like many of his colleagues, aspired to doing a newspaper

strip. Star Hawks was a dream

coming true. "We soon realized," Goulart said, "that because of its

unique size, our strip had to have a look of its own. What we were providing

was the equivalent of a full comic book page every day. Gil decided

not to pile two dailies on top each other but to break up his space

in much more effective ways." In

its unprecedented expansive format, the strip afforded Kane the space

a high adventure story needs. Varying panel size and layout from day

to day, as I point out in a book of mine

(The Art of the Comic Book, which you can see more hints of by clicking

here), Kane broke old molds for

newspaper strips. His panels slashed vertically through the two-tier

space allotment, and Kane filled the large panels with exotic scenery

and complex machinery and crowds of fighting men: with this much elbow

room, Kane could create and sustain an authentic futuristic atmosphere

for Goulart's stories. "The story and dialogue were mine," Goulart explained,

"but the actual staging was a collaboration. Gil's input was usually

on how the story was told, not what was said. And we kicked around ideas

for characters. Gil was always enormously conscious of staging. We devoted

a great amount of time to the timing-and how you went from one scene

to another." The

spacious Star Hawks format

permitted Kane to do more than set his scenes with impressive splash

panels. Kane cut up his space to suit each day's story installment.

And on days when the narrative demanded it, he staged the story in five

or six panels, timing the action in ways that the standard one-tier

strip in the diminutive dimension of the 1970s could no longer aspire

to. Sometimes a series of strip-wide horizontal panels emphasized the

sprawling action of a sequence; sometimes the panels were narrow verticals,

suggesting slices of time or, like one of the two daily strips reproduced

near here, representing towering heights. Stylistic

achievement aside, Kane's signal accomplishment in Star Hawks lays in the manner in which he exploited the potential

of his strip's novel format, giving us an impressive demonstration of

the storytelling potential of comics art. Not since the thirties had

an adventure strip been afforded the sort of room that permits this

kind of storytelling-the kind that displays the best of which the medium

is capable. The National Cartoonists Society recognized Kane's newspaper

strip achievement with a silver plaque for best story strip in 1977-as

it had his work in comic books with similar awards in 1971, 1972, and

1975. But

after a couple years in the sun, Star

Hawks faded. Partly, the very ambitiousness of the project contributed

to its downfall. To publish Star

Hawks, newspapers had to make room on their comics pages by dropping

two other comic strips; no matter how they managed that, scores of readers

would complain. So newspapers didn't line up by the dozens to buy the

strip. Without circulation, income was iffy. And Kane, who had to earn

a living, tried to keep up his commitments with Marvel while also doing

the strip. Inevitably, he began to fall behind. Other artists helped

out. Kane fell ill; more substitutes. Then the strip acquired a new

editor who didn't like Goulart and eased him off the strip he'd invented!

Archie Goodwin took over scripting with the April 30, 1979 release.

Three months later, on July 30, Star

Hawks became a single-tier strip, like all others. But

the glorious days of the Kane-Goulart team are well preserved in this

giant 9x12-inch, 320-page volume from Hermes Press, which has published

two other Kane books (Gil Kane:

The Art of the Comics and Gil

Kane: Art and Interviews). Star

Hawks: The Complete Series ($49.99) includes the whole run of the

strip, Goulart-scripted and post-Goulart. Dailies and Sundays. The whole

enchilada. The book's only flaw is a significant one: it prints four

daily strips to a page, which reduces them to a horizontal dimension

about an inch or so smaller than they appeared when first published

in newspapers. Considering the extravagance of the visual concept of

the feature, the decision to run the strips so small seems a rank disservice

to Kane's art. But the cost of production is ever a factor in such endeavors.

And to make up somewhat for this blemish, the book is printed on slick

coated paper that is capable of retaining the smallest details in the

artwork. And the art in most of the strips is well served here. The

book is outfitted with a Foreword by Goulart and an Introduction by

Hermes' Daniel Herman. Goulart gives a short history of his partnership

with Kane; Herman rehearses Kane's career. Although the bulk of the

pages are in black-and-white, a concluding section reprints the first

two-and-a-half months of the Sunday strips in color. Star

Hawks is one of the great achievements in the medium, and we are

fortunate to have the whole of it at hand, even at the size it appears.

Even at that size, the elegance of Kane's visualizations shines forth,

and the wit and pace of Goulart's stories remain entact, racing from

page to page. One

of Kane's other great accomplishments as a visual storyteller was what

is arguably among the first graphic novels, and Fantagraphics has reprinted

both of them between a single set of covers. Blackmark:

30th Anniversary Edition (252 6x9-inch pages in paperback;

black-and-white, $16.95, www.fantagraphics.com)

actually appeared in 2002, but I didn't get a copy until recently. Blackmark

is the hero of a tale set in that fictional age of sword and sorcery

where science and magic mingle. Kane did two stories: the first traces

the title character's life from youth to maturity; the second shows

us Blackmark as ruler of his people. In both, Kane juxtaposes narrative

text and pictures replete with speech balloons, achieving a new kind

of narrative economy and dramatic power by letting words do what they

do best (describe intangibles and span time with a few phrases) and

getting pictures to do what they do best (depict emotions and actions

and to establish mood with atmospheric visuals). This is what a graphic

novel would be if it had been intended, as Kane intended it, to be something

other than long-form comic books. Each story was structured and designed

to appear as a single book-length tale. The first was published in paperback

by Bantam in 1971; the second was finished and ready for publication

when Bantam gave up on the project. A third, which Kane said he'd almost

finished penciling, never went any further. The second was subsequently

published in the late 1970s in a Marvel publication, Marvel

Preview. In this Fantagraphics incarnation, both stories appear

as Kane originally designed them but at a slightly larger dimension.

"Large enough," says publisher Gary Groth in his helpful Afterword,

"to serve as an improvement on the tiny original paperback but

small enough to maintain the quality of the art." The second story,

which had been reconfigured for the Marvel magazine, appears here as

Kane had intended it. Scripted by Archie Goodwin over Kane's concepts,

these are powerful, affecting stories, dynamically told as only the

comics medium, yoked to narrative text, can tell them. A brave beginning

for the graphic novel form. Metaphors

be with you.

To find out about Harv's books, click here. |

||||

send e-mail to R.C. Harvey Art of the Comic Book - Art of the Funnies - Accidental Ambassador Gordo - reviews - order form - Harv's Hindsights - main page |