EUGENE

ZIMMERMAN, THE GREAT “ZIM”

America’s

First Cartoonist

IF ZIM DIDN’T

INVENT “BIGFOOT” CARTOONING in America, he was at least the foremost

practitioner of the form during his career on the staff of the humor magazine Judge, roughly 1886 - 1910. Zim’s was a storybook life: in an virtual enactment of

the American dream, Zim rose from a youth of poverty to fame and fortune

through diligent application of his talent.

Born

May 25, 1862 in Basal, Switzerland, Eugene Zimmerman was the second son of

Joseph Zimmerman, a baker, and Amelie Klotz, who died giving birth to a

daughter two years later. Unable to care for his three children and earn a

living, Joseph placed his children with relatives, sending Eugene to an aunt

and uncle in Thann, Alsace, and finding employment himself nearby. In 1867,

presumably to avoid compulsory military service in the armed forces being

mustered for the impending Franco-Prussian war, he emigrated to America with

his oldest son, settling in Paterson, New Jersey.

Meanwhile,

anxious to protect their nephew from the dangers of the looming war, Eugene's

relatives sent him to America in 1869. He stayed with another aunt and uncle

in New York City for several months before going to live and work with his

father in a bakery in Paterson. Astonishingly, in one of three

autobiographical fragments, Zim says his arrival at his father’s house was a

surprise to his father.

Zim’s

account of his youth offers shocking insight into the life of a poor immigrant

boy in 19th century America. At first he labored with his father,

and he later attributed much of his success as an artist to the experience

gained in the cellar of that bakery: “There, during the small hours of the

morning, by lamplight,” he said, “I used to execute marvelous designs in

frosting, or model in dough such realistic images that people, after

purchasing, would hate to destroy them.”

His

first “newspaper experience,” he told Regina Armstrong at The Bookman in

1900, “dates back to the time of the [Horace] Greeley [presidential] campaign

[of 1872—i.e., when Eugene was about ten years old] when he helped to make the

night hideous with the cry of ‘Extra! Extra!’” hawking the Paterson Daily

Guardian.

Although

he attended school (Old Van Houten School) until he was about twelve, he

worked, too, at every available opportunity. Armstrong reports that “at one

time he unceremoniously joined his fortunes with a fish peddler, and remained

with him two years, helping him in his piscatorial profession during the spring

and summer, attending school during fall and winter. But he feels that his

education suffered severely on account of his fondness for drawing. He was wont

to ornament the fences in the neighborhood with colored crayons. During his

school days, it was considered a crime to be able to draw, and every inducement

was held out to him to reform, but caricature was his ambition.”

For

a time, Eugene served as part-time office boy for a real estate broker and

began to develop his artistic skills by lettering signs that advertised the

properties his employer managed.

At

the age of twelve, Eugene left the bakery and the city for the more appealing

outdoor work he found as a chore-boy on a succession of farms. For the next

three or four years, the youth worked for three meals a day and hand-me-down

clothing with little or no time for school and no monetary recompense at all.

He often worked from dawn to midnight, and he slept in a room in the attic or

in the barn with the horses. No wonder we needed child labor laws.

Zim

wrote of the “dreary monotony” of his “long dull years” as a farmer’s helper,

saying: “Life’s joys seemed only for others. It is a marvel to me how I ever

developed a humorous instinct in such an atmosphere of mediocrity,

heart-hunger, and sadness. Mindful of the tender love bestowed upon my

playmates by indulgent parents, I was often given to silent prayers in the

seclusion of my lonely attic bedchamber, prayers as only a kid could invent,

for the gloomy people with whom I dwelt evinced little interest in my spiritual

welfare.”

When

Zim was fifteen, the winery on the farm where he was working burned down. After

it was rebuilt, Zim lettered the name of the winery on the new windows,

attracting the attention of a passing sign painter, William Brassington, who

took him on as an apprentice, offering a bed and three meals and cast-off

clothing again; no salary. Said Zim: “During my apprenticeship to Brassington,

I scarcely knew the feel of a dollar.” But his artistic career was launched.

The same year, the weekly humor magazine Puck began publication.

With

the youth in tow, Brassington settled in Elmira, New York, to which he moved,

Zim said, because it was “more convenient to migrate than to liquidate his

heavy indebtedness.” While with Brassington, Zim gained practice drawing as

well as lettering: some of the signs Zim was assigned to do required a picture

as well as words. In 1880, Zim was hired by another sign painter, J.T. Pope, to

head his pictorial staff in nearby Horseheads, New York—this time for an actual

salary, $9 a week. During that election year, some of the pictures Zim painted

were, by modern standards, highly unusual.

Electioneering

in those days was done with rotten vegetables and clenched fists and blunt

instruments, “so that after each gorgeous political pageant, our shop was

filled with solemn bearers of optic discolorations,” Zim recounts. “In those

days, it was as fashionable for men to camouflage black eyes as it is today for

womenfolk to rouge pale cheeks and to dab red noses with rice powder.

Disguising blackened eyes to give them a natural appearance was a thriving

feature of the sign man’s profession during the late 1870s. ... Frequently, I

was called upon to match up flesh tints and rescue my patrons from the

humiliation which accompanies such a situation. For this form of art, we

charged a fee of fifty cents, regardless of the extent of the bruise or the

depth of flesh tone to be covered. At times it called for two or three priming

coats as a substantial foundation for the artistic touches that followed. I

have seen fellows carry around their eye sockets as much as a quarter of a

pound of white-lead glazed over with baby pink that attracted far more notice

than the original black eye itself, but that mattered not.”

By

this time, Zimmerman had seen copies of Puck and had decided that he

wanted to be a comic artist. On a visit to New York City in late 1882, Zim

left a portfolio of his work with relatives who arranged for Joseph Keppler, editor of Puck, to see the samples, resulting in Keppler's hiring

the young man the following May. Zim’s salary, initially $5 a week, was

quickly raised to $10, which Zimmerman supplemented with drawings for

advertisements commissioned by local businessmen, increasing his weekly

earnings to as much as $80 a week in two years. His career as a cartoonist was

underway.

While

with Puck, Zim began doing political cartoons and developing a drawing

style of gross distortion. At first, however, he simply assisted Keppler,

working at a desk near the boss’s “compartment” ... “a small, clean enclosure

in the Puck art department,” similar to other adjoining “stalls,” like

those “of fine racehorses.”

Zim

admired Keppler’s work and studied it. Walter M. Brasch, the editor and

compiler of the cartoonist’s posthumous autobiography, believes Zim acquired

his bigfoot graphic mannerisms from Keppler, but Zim maintained he did not copy

Keppler’s style. He was more influenced, he said, by L. Hopkins, who drew for

the New York Daily Graphic: “Something in his pictures hit me forcibly,

but I discovered in time that I was drifting into another man’s technique, so I

swung away from it, unconsciously creating a style of my own.”

Despite

his protestations, Zim was undoubtedly affected by what he saw Keppler doing.

Depending upon his subject, Keppler drew in either a realistic illustrative

manner or in what Zim called a “grotesque” fashion that gave his figures

disproportionately large heads with the caricatured faces. And the figures

themselves had gangly anatomy. This kind of exaggeration would later

distinguish Zim’s mature style.

(The captions on most of the Zim cartoons I’m

posting here may be too small to read easily; to enlarge them, click on Page at

the top of your screen, then on Zoom, and then pick an enlargement—say, 150%.)

Zim

was doubtless also influenced by Bernhard Gillam’s work at Puck. Gillam had joined the staff at Puck in 1881 after attracting Keppler’s

attention with his cartoons at the Daily Graphic, reputedly the first

newspaper to use pictures on a daily basis since its founding in 1873. Zim and

Gillam quickly became friends: they were the only Republicans on the Democrat Puck, which, apart from their mutual admiration of each other’s artistic

achievements, doubtless cemented their friendship.

Oddly,

Gillam did his most famous cartoon, “The Tattooed Man,” during the 1884

presidential contest between James G. Blaine and Grover Cleveland: Gillam

depicted Blaine tattooed with words that recalled all of the Republican

candidate’s ethically questionable deeds of the past. That Blaine lost the

election to the Democrat Cleveland is often attributed to the persuasiveness of

Gillam’s cartoon. But Gillam probably voted for Blaine; ditto Zim.

“Puck was not merely a comic weekly,” Zim said, “it was a very influential

political journal—and as long as it published Keppler’s and Gillam’s cartoons, Puck had no rival.”

Except

maybe The Police Gazette, Zim admitted: “Puck and The Police

Gazette used to be the leading educational features of pool rooms and

barber shops and eventually lost ground with the rise of the safety razor,

which allowed me to easily shave at home.”

But

another rival soon cut into Puck’s circulation.

Puck had been politically independent at first, “but gradually listed” left, Zim

observed, creating an opening for a Republican rival on the newsstands. It was

soon supplied by one of Puck’s stable of artists, James Wales, who left

the magazine (reputedly after a dispute with Keppler) and launched Judge in October 1881. But Judge did not become a serious Republican

challenger to Puck’s Democrat voice until William Arkell, bankrolled by

the Republican Party, purchased it in 1885. And Arkell forthwith hired Gillam

away from Keppler, offering him a salary as art editor that was half again as

much as Keppler was paying (and appealing thereby to Gillam’s sense of justice:

because Puck’s circulation had increased spectacularly with the

publication of “The Tattooed Man,” Gillam had asked for a raise but had been

refused).

Gillam

didn’t want to go by himself to Judge and persuaded Zim to accompany him

by offering to double the salary he was making at Puck. The money was

attractive, but the opportunity was probably what convinced Zim to make the

leap: as the most successful comic weekly, Puck had attracted a number

of artists, which reduced Zim’s chances at being published regularly and in

choice location on the cover, back cover, or centerspread. Zim thought his

chances for “artistic advancement” were greater at Judge; and he was

right.

“At Judge, I had absolute freedom to do as I wished and draw what I

pleased,” Zim said, “— ample space in the magazine to play with, an occasional

chance at the center double-spreads [understandably, Gillam would be featured

more often], and an option on shares of stock in the publishing company in

addition to retaining the privilege of doing outside commercial work. ... I had

a clear road ahead and no traffic cop to hold me back.” He joined Judge in December 1885; he was 23 years old. And the rest of his employed career he

would spend at Judge.

“Conducting

an illustrated weekly paper is like running a boarding house: all the scraps of

the week go into a delicious hash which is enjoyed by everyone,” Zim said. And

he clearly thrived by helping to concoct the repast.

SOMETIME IN

1885, ZIM made a significant alteration in his artistic personna: “My long name

became a burden,” he wrote, “so I threw two-thirds of it overboard, thus saving

time, space and India ink, and providing a merman for any sea nymph who cared

to salvage. A friend, a very successful business man, noticed that my

signature, ‘Zim,’ had a downward slant. Said he: ‘Never sign your name

downhill, always uphill; it looks more prosperous.’ From that moment, I have

always signed my drawings uphill for I believe there is truth in his

assertion.”

In

1886, on September 19, Zim married Mabel Alice Beard of Horseheads and they

moved to Brooklyn; they had a daughter, Laura. The marriage, however, may not

have been blissful. Brasch, basing his opinion upon what “many who knew him or

knew of him” said and upon Zim’s seldom mentioning his wife in any of his

writings, concludes that Zim “was not happy in his marriage.” Zim himself talks

about marriage only to make jokes about it. In his “how to” book for aspiring

cartoonists, he quips: “In the face of the facts before me, it would be safe

for me to state that a man, to be successful in any matter he undertakes,

should be either married or unmarried.”

He’s

a little less ambiguous in one of his humorous Horseheads “history” books, In

Dairyland, wherein, under the heading of “Domestic Hints,” he advises: “A

wife should never be awakened with a start. Always be kind and gentle when

yanking her out of bed by the heels. Keep her good natured till after breakfast

by all means.” By the same token, Zim often portrays husbands as slave drivers,

insensitive louts who lounge around the house or in nearby taverns, leaving all

the work to their wives.

But

these cynical comments may reflect the humorist rather than the husband and

father. Describing his workshop, Zim says: “Children never annoyed me in my

work. I often labored at my desk with Laura [his daughter] on my knee and

Adolph [his adopted son] playing around. ... Occasionally, the youngsters’

prattle suggested ideas for comics.” These remarks, and the gentle spoofing

tenor of his writing, suggest that his comments on marriage grew out of his

comedic sense not his domestic situation.

In

1888 or so, Zim suffered what may have been a nervous breakdown, and he and

Mabel went to Florida for a few months to recover. But he continued cartooning

for Judge, sending in his work by mail. When he returned to New York, he

and Mabel moved back to Horseheads permanently; henceforth, Zim would spend

every other week in New York at the Judge office.

In

Horseheads, Zim was a genuine hometown dignitary, and throughout his residence

there, he donated time and drawings to scores of civic enterprises. He joined

the volunteer fire-fighting Acme Hose No. 2 during his first sojourn in town in

1881 and remained a member until his death. He served as alderman 1891-1893,

and he organized a town band in1897-1900 and again in 1909-1916. The Horseheads

Historical Museum remembers the cartoonist with its special "Zim

Room," whose walls were hung with his drawings.

After

Gillam died unexpectedly of typhoid in 1896, Zim and Grant Hamilton, who

became art editor, had to increase their output for the magazine to fill the

holes in page layouts that Gillam would otherwise have filled, and Zim

reluctantly spent more time in New York. By 1901, however, Judge was in

financial difficulty, and ownership started changing hands—as did the

editorship. In 1909, the owner, Standard Oil of New Jersey, reorganized the

magazine to prevent financial collapse: page size was reduced and political

issues were usually avoided, according to Brasch. Zim quit the magazine in 1912

“for the life of a freelance,” but he had not contributed much since the

reorganization because one of the editors “turned down many good ideas for fear

of offending personal friends or acquaintances, and the advertising department

hampered us still further.”

Elsewhere

in discussing his departure from Judge, Zim says he quit because his

health was “slipping away” under the strain of working under deadline pressure.

“To give an idea of what half a century of cartooning means,” Zim writes

retrospectively in 1930, “in the course of one year, I made more than 1,000

drawings for Judge alone—front and back covers and double-page spreads,

also Judge’s library covers, all in colors, some drawn on stone, in

addition to black-and-white drawings. During a period of freelancing, I worked

for seventeen different publishers, from twelve to sixteen hours a day. It is

torture for artistic brains to toil on a time schedule like an alarm clock,” a

pressure than increased with the development of modern methods of publishing in

great quantities.

Comparing

the art of earlier periods with more modern productions, Zim says, “we find a

certain deterioration. ... I myself feel the spirit of the times and am swayed

to work as carelessly as some of the others. Not from choice, I assure you, but

to keep up with the procession. ... Commenting on the way quantity production

has affected my technique, cartoonist Walt McDougall says in his autobiography, This Is The Life!, ‘As the years went on, Zim altered his style, growing

funnier if less artistic.’

“Readers,”

Zim continues, “can observe this alteration by comparing my earlier cartoons

with the more recent ones. The latter are drawn more hastily and with fewer

lines.” But, he explains, “if an artist can produce a momentary laugh, he has

earned his money, no matter in what manner he did it.”

In

his “how to” book, Zim makes the same case by humorous example: “The main point

in the profession is ‘The Lead Pencil.’ Whenever you sketch in public, in order

to throw your audience off the track and make them think that you are a

full-fledged caricaturist, always wear a reckless air and a common twenty-five

cent necktie.”

But

in his autobiography, he also emphasizes that comical drawings benefit from

being quickly executed: “A comic cannot be drawn tediously and yet contain the

mirth which it is possible to put into a quick sketch. In the latter case, you

get the spontaneous thought and humorous action, most of which you unavoidably

destroy in polishing up the work for presentation to the public in a finished

manner.”

Earlier

on the same page, Zim confesses that “I rarely see anything funny in my own

drawings and am continually seeking better results while the humor of other

artists fills me with a sort of envious delight. My finished work always

appears defective and, as I look back upon it, I am not far from incorrect in

believing thus.”

ZIM SCARCELY

RETIRED when he left Judge. He had published the aforementioned “how to”

cartoon instruction booklet in 1905, This ’n’ That About Caricature (which was revised and added to in 1910 and published as Cartoons and

Caricature: Making the World Laugh). The book brims with sound, practical

advice about drawing—some of it, like the caution against having lines overlap

in a picture, not readily available elsewhere anymore. But Zim infiltrates the

how-to’s with other valuable tidbits:

“In

the first place, try to forget that you are a great artist and lead a natural

life. Don’t be too eccentric. Be like other poor mortals who love to earn an

honest living, and the world will love you the better for it.”

“When

you make a character sketch, be sure to append an appropriate foot. ... It’s

the proper treatment of details that earns big salaries.” Illustrated with an

array of different footwear.

“Perhaps

the hardest simple object to draw correctly from memory is a silk plug hat [top

hat]; it is so perfectly shaped that the slightest discrepancy in drawing it is

perceptible. ... An open umbrella is also very difficult.”

“Refrain

from caricaturing acquaintances unless you are sure they are not of a sensitive

nature, else you may incur their enmity. If they are sensitive or vain, they do

not deserve the attention of your pencil or pen. You may ridicule, but don’t

offend.”

Reprinted

in 2012 by Lost Art Books under the title Cartoons and Caricature, the

tome contains, says its publisher, Joseph V. Procopio, “Sage advice on a

variety of esoteric subjects, including Swiping, Booze and Bohemianism, Dealing

with Editors, and Cartoonists and Marriage.”

About

Bohemianims, Zim cautions: “To follow this life in its true sense is all very

well, but the average art student is quite apt to mix it up too freely with

beverages of amber and more ruddy tints—a nerve-wrecking and career-destroying

course.”

Recalling

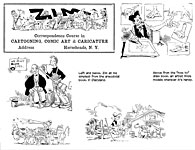

the book’s success after he had formally retired from active cartooning for Judge in 1912, Zim launched a cartoon correspondence course that expanded on the

ideas in the book. He continued the course into the next decade, generating

ample income. He also freelanced illustration for books and advertising, sold

occasional cartoons to major magazines, produced a newspaper Sunday comic strip

called Louie and Lena, and wrote and illustrated a monthly humor column,

"Homespun Phoolosophy," for Cartoons Magazine 1916-1918. In

1926, he served as the first (and only) president of the American Association

of Cartoonists and Caricaturists, which expired the next year when Cartoons

Magazine withdrew its support.

He

was also engaged in many local projects; he had written Zim’s Foolish

History of Horseheads in 1911 and a similarly entitled book about Elmira in

1912. In 1914, he produced another in the same vein, In Dairyland—a

book, he wrote in a preface, “issued in commemoration of the sesqui-centennial

of the Battle of Newtown and in celebration of the rapid rise of the hostile Indian

from a life of indolence to that of a peaceful hard-working cigar sign, with

other bits of historical data from the romantic period of the first settlers to

the frivolous days of Will Rogers.

“The

remarkable feature about this book,” he continues, “is that it can be perused

in all kinds of weather, or in any climate, without causing distress or further

expense to the purchaser, and has even aided some to forget their business

cares and many other body ailments too numerous to mention. The author believes

that such a book, at this particular time and the present condition of the

country, was a commercial necessity, for that reason he gladly laid aside his

financial obligations that he might, without delay, be prepared to meet the

enormous demand for the book which he anticipates.

“This

book was printed upon the press of the Chemung Valley Reporter. The

author whose instincts are more wet than dry intended to run the edition off on

Sayre VanDuzer’s cider press instead, but the apple crop fell due at the critical

moment and required first attention, so that the job was necessarily

transferred to the aforementioned printing plant.

“The

publishing house upon whose premises this history was printed being minus a

regularly and properly ordained chaplain, we are obliged to forego the

propriety of opening the ceremonies with the usual short prayer for the book’s

success. The author therefore asks the aid of all good christians [Zim’s lower

case] in creating a demand for the book.

“In

my opinion,” Zim concludes, “history should be overhauled at least now and then

to admit the latest facts to creep into its pages. No history to my best

knowledge is entirely indisputable, and frequent re-writing renders it more

authentic. It is with this end in view that I take up my pen to correct

previous errors and unintentional misstatements. The facts herein contained are

absolutely without blemish. Sworn statements to that effect will be made by our

head pressman, an adept in the handling of up-to-date profanity who has been retained

to do the swearing.”

The

rest of the book (of which there is much more) is a collection of anecdotes and

“historical” observations much in the same tongue-in-cheek spirit as the

foregoing paragraphs. Zim also sprinkled in a generous assortment of bon mots

and witty observations—for instance:

“Regarding

Santa Claus: What joy a harmless fib can bring unto a child, and what sorrow

the naked truth.

“Some

men’s remarks would be better appreciated if they talked less and said more.”

And

this:

“In

a nearby city there resides a well-known piano tuner who bears my family name.

A lady one day stepped from her Ford sedan and, approaching me, smilingly

inquired: ‘Are you Zimmerman, the piano tuner?’ ‘No, mum,’ said I, ‘—I’m

Zimmerman the car-tooner.’ ‘Oh, I beg pardon,’ she blushingly articulated. ‘My

car, I am gald to say, is in perfect tune, but my piano— dear me!—is just

terribly awful.!’”

All

of which proves that Zim was as good with humorous prose as he was with comical

pictures.

IN THE LAST

DECADES OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, Zim was among the most noted of his

profession. In his 1926 autobiography, This Is the Life!, cartoonist

Walt McDougal called Zim "the greatest cartoonist of the 1880s"; the Chicago

Tribune said he was "the funniest cartoonist now living." And Munsey's

Magazine in 1904 reported that he stood "alone in the point of

originality and conception and treatment. He is what artists denominate as an

‘acrobat,’ but careful scrutiny of his work will reveal the truth behind his

grotesque exaggerations."

Zim

was among the first cartoonists to draw in what eventually was regarded as the

"cartoon manner"—comparatively simple linework depicting exaggerated

anatomy and lively movement.

Most

of the inkslinging fraternity in those days were illustrators, not cartoonists. Charles Dana Gibson, for instance—famed for his exquisite penwork and

the glacially beautiful "Gibson girl"—drew in quite a realistic

style.  So did Thomas

Nast and E.W. Kemble and A.B. Frost, M. Woolf, F.M. Follett, Dan

Beard, F.T. Richards, and many others whose work was published in the humor

magazines of the time and for a decade or so into the twentieth century. Their

work was elaborately detailed, their lines thoroughly hachured and

cross-hatched, the impression realistic. Many of them did work for the humor

magazines Puck, Judge, and Life (to name the three that

flourished through the latter half of the nineteenth century) almost as a

supplement to the greater income they derived from illustrating realistically

short fiction in magazines like Leslie's Monthly or Harper’s Weekly. So did Thomas

Nast and E.W. Kemble and A.B. Frost, M. Woolf, F.M. Follett, Dan

Beard, F.T. Richards, and many others whose work was published in the humor

magazines of the time and for a decade or so into the twentieth century. Their

work was elaborately detailed, their lines thoroughly hachured and

cross-hatched, the impression realistic. Many of them did work for the humor

magazines Puck, Judge, and Life (to name the three that

flourished through the latter half of the nineteenth century) almost as a

supplement to the greater income they derived from illustrating realistically

short fiction in magazines like Leslie's Monthly or Harper’s Weekly.

But

Zim was pretty exclusively a cartoonist not an illustrator. Although he

illustrated some books, his "illustrations" were usually cartoons.

His drawings were cartoons because their juicy line-work was simpler and

because he exaggerated human anatomy for comic effect. He drew flamboyantly,

deploying a liquid line that waxed thick and waned thin to limn his comically

capering creations.

Others

were doing something of the same sort by the first decade of the twentieth

century. Art Young, for one—whose simplicity of line is very modern

indeed; but Young’s proportions—his caricatures of humanity—are much more

restrained in comparison to Zim's bigfoot oeuvre.

(For a biography of Art

Young, visit Harv’s Hindsight for February 2004.)

The

same might be said for James Montgomery Flagg, whose Nervy Nat was a

comic exaggeration even if the rest of the cast of that feature was usually

depicted rather realistically. (Flagg, by the way, came to regret his early

career as a "cartoonist," and in later life, he would very nearly

deny that he had ever drawn such things as cartoons. The accompany pictures are

of Nervy Nate as well as the first picture, an undeniably comical one lofting a

perfectly bad pun, that Flagg had published in the humor magazine Life.)

But

it was Zim’s propensity to exaggerate that made his drawings cartoons. Only T.S.

Sullivant of Zim's contemporaries regularly distorted human anatomy with

such comic abandon.

In

the spirit of humorous exaggeration, Zim during his heyday frequently employed

the crude racial stereotypes that were the common coin of comedy in his time—

his big-nosed Jews were parsimonious; his simian-faced Irishmen, drunk; and his

liver-lipped blacks, lazy.

These

thoughtlessly cruel stereotypes were the common coin of comedy until well into

the twentieth century. And Zim minted no new medium of humorous exchange when

he depicted, as he frequently did, persons of these heritages in comic

exaggeration. He was doing what nearly all his colleagues did. Writing in the

1930s, Zim comments on this practice: “Forty or fifty years ago the comic

papers took considerably more liberty in caricaturing the various races than

they do today. Jews, Negroes, and Irish came in for more than their share of

lambasting because their facial characteristics were particularly vulnerable to

caricature.”

That's

how he explained his racist pictures to himself: their faces were funny enough

in nature to be even funnier if caricatured. This is cartoonist talk, not

racist slurs. It's a man looking for comedy. And he's looking in places where

the show business of his age also looked: in vaudeville and minstrel shows,

African Americans and Jews and Irishmen were often figures of fun.

In

the article in The Bookman, written in 1900 and therefore in the time of

Zim’s egregious racial caricatures, Armstrong writes: “Zim likes the comedy of

art, character work, and especially the portrayal of country types and the

types of different nationalities [i.e., ethnic groups]. His own career has made

him see the human kinship of the world, and perhaps his distortions of

physiognomy in his characters are compatible with every one because he himself

feels that nothing is incongruous. He says that types cannot be exaggerated;

one can always find in actual life more extravagant peculiarities than are

pictured through the imagination.”

Zim

was very much a man of his times (he could scarcely be a cartoonist otherwise),

and in his day, racism was so much a fact of ordinary life that many were not

even aware that they were racists. In short, Zim was no more racist than any

other white person of his time. Which is another way of saying that they were

all racist. But they probably didn't realize it. Many white folks didn't. They

were blind to their faults. A not uncommon failing. Even today.

Even

in those bygone halcyon days, however, humorists could not with complete

impunity publish racist material. Said Zim: “Although most Hebrews enjoy jokes

on themselves, the strictly orthodox do not take kindly to that form of humor.

One time a Semitic society threatened to boycott Judge; and as our

purpose was not to offend, and as the vital part of a funny paper is its

circulation, we quickly put on the brakes. ... On another occasion, a Negro

preacher took exception to my darky cartoons,” citing several examples proving

that “colored gentlemen” were not the only ones to steal chickens, “so I had to

let up a bit on the Ethiopians.”

Writing

his autobiography in the 1930s, Zim realized that "only the most stupid

publishers" would publish then [in the 1930s] the kinds of racist cartoons

everyone was publishing at the turn of the century.

"Forty

or fifty years ago," he continued, "the comic papers took

considerably more liberty in caricaturing the various races than they do

today. Jews, Negroes, and Irish came in for more than their share of

lambasting because their facial characteristics were particularly vulnerable to

caricature."

A

cartoonist looking for comedy, Zim found it where the show business of his age

found it: in vaudeville and minstrel shows, blacks, Jews and Irishmen were

figures of fun. And in exaggerating for graphic comedy, Zim created cartoon

style drawing.

Hereabouts,

a short sampling of Zim's work in this arena. No, I don't think the sense of

humor displayed in these mindlessly vicious caricatures is praise-worthy. Nor

do I intend by publicizing their existence in This Corner to prolong the

vitality of the stereotypes Zim's cartoons trade in. Those of the politically

polite persuasion who chance upon these pictures will be appalled, of course.

And well they should be. We all should be.

But

hiding the pictures in the closet denies that they ever existed. Not only would

we be denying our past, we would be denying the evil in our past. We would be

misrepresenting our history, lying about ourselves. And if we do not

occasionally recollect the things we did of which we are now ashamed, we will

not be equipped to avoid repeating the same sins in the future. "He who

knows only his generation remains always a child." Upon this axiom is

founded all of the Jewish Holocaust literature and liturgy.

Zim's

penchant for doing cartoons about racial types is handily explained by his

visual sense of humor. In Zim's eyes, the facial features of certain minorities

lent themselves more readily than others to caricature—to exaggeration. Since

his forte in drawing for humor magazines became exaggerative drawings, it is

natural that he would resort (perhaps more than many of his fellows) to what he

perceived as the highly comic facial characteristics of those who "looked

different." And they talked funny, too.

Again,

I do not claim that Zim was not a racist. By our standards today, he clearly

was—he and most whites of his time. But his impulse was towards comedy not

contumely. He aimed to provoke laughter among his readers not bigotry. In body

of Zim's work, we have striking examples of what funny pictures really are. And

we should rejoice in them, the work of the most eminent bigfoot cartoonist of

his day and a pacesetter for his profession.

Zim

wrote at least three autobiographical fragments over his last next few years,

and he died in his home of a heart attack March 26, 1935.

For

a finale, here’s a gloriously tumbled-up mob scene of Zim characters. And then

we give Zim the last word and a comical picture of the end.

|

|

Bibliography. Virtually all of the readily

available biographical information about Eugene Zimmerman is contained in Zim:

The Autobiography of Eugene Zimmerman (1988), a compilation by Walter M.

Brasch of Zim's several autobiographical musings and drafts. Unless otherwise

noted, the utterances of Zim quoted above are taken from this book. Zim was

interviewed by Regina Armstrong and her paraphrase of his comments appear in

“The New Leaders in American Illustration” in The Bookman, June 1900.

Zim's papers and much original art are maintained at the Zim House Museum, once

the cartoonist's home in Horseheads. Most of Zim's artwork for Judge, however,

was destroyed in a fire in the magazine's office in 1908. In addition to the

twenty-volume Zim's Correspondence Course in Cartoons and Caricatures (1913),

Zimmerman's works include: A Jug Full of Wisdom: Homespun Phoolosophy (1916), Fire: Heroic Deeds for the Dingville Fire Department (1922), Foolish

History of Horseheads (1911), Foolish History of Elmira and Its Environs (1912), This and That about Caricature (1905), Language and

Etticket of Poker (1916), and In Dairyland (1914). He illustrated Bill

Nye: His Own Life Story (1926) and Nye's Wit and Humor, Poems and Yarns (1900) as well as Railway Guide (1888) by Nye and James Whitcomb

Riley.

Return to Harv's Hindsights |