Basil Wolverton and Lena the Hyena

More than A Master Drawer of Ugly Women

MY GUESS is that no one has ever written anything about cartoonist Basil Wolverton without dwelling at the onset upon his most celebrated creation—Lena the Hyena. I’ve never written anything about him without invoking the champion Ugly Woman of All Time. I’ve reviewed two books of the Wolverton canon in the last couple years, and both times, I got Leena right up there on the launch pad paragraph. But not this time: this time, she doesn’t appear until we’re halfway through this Wolverton lucubration. And that’s how it should be: Wolverton’s achievements as a cartoonist dramatically exceed his undeniably consummate ability to draw a stupendously hideous woman.

Harvey Kurtzman would doubtless agree. “For me,” he once wrote, “Wolverton always had an integrity of style and effort. Though never aesthetic, his style was always consistent, always pure Wolverton. He never borrowed, never hacked, and he never short-changed his public. And this is a good deal of the reason why he is what few of his contemporaries can claim. Wolverton is an original.”

Ditto Will Elder, who said Wolverton’s technique was “outrageously inventive, defying every conventional standard yet upholding a very unusual sense of humor. He was a refreshing original.” Jules Feiffer, on the other hand, was of another opinion: “I don’t like his work. I think it’s ugly.” Maybe Feiffer was thinking only of Lena.

And Wolverton displayed his originality in more than 33 different features appearing in over 50 different comic book titles, a remarkable accomplishment for a relatively short active comic book career (1936 until the early 1950s). The Wolverton canon includes crisp and convincing space operas, for instance—staring Spacehawk or Meteor Martin or Shock Shannon. And his copiously detailed weird horror tales—“The Eye of Doom,” “They Crawl by Night,” “The Man Who Never Smiled.” And his surpassing rendition of the Old Testament in pictures—The Story of Man (aka The Wolverton Bible). Or, his most celebrated achievement, a host of hilarities laced with visual puns and jingling alliterative dialogue—featuring such lovable buffoons as Powerhouse Pepper, Bingbang Buster, Mystic Moot and His Magic Snoot, or the “peculiar people” series of “private peeps at preposterous punks who prowl this planet.” In this latter category, we have The Culture Corner.

A half-page comic book feature that appeared in “nearly every issue” of Fawcett’s Whiz Comics from No. 65 in May 1945 through No. 146 in June 1952, The Culture Corner is the most compact demonstration of the visual and verbal zaniness of Basil Wolverton. The working premise of the feature was simple: it was a guide to behavior for anyone who wished to appear “cultured.” Wolverton would concoct a problem (how to improve your posture, how to get out of bed gracefully, how to open a sticky window), which, as time unraveled, became wilder and more improbable (how to cure flat feet, how to laugh at a bum joke, how to stop brooding if your ears are protruding, how to fall on your face, how to eat beans without soiling your jeans) and then devise ways to solve the problem, the more outlandish the solutions, the better they suited the equally outlandish dilemmas.

And now, thanks to Fantagraphics, collector/archivist Glenn Bray and Wolverton’s son Monte, we have all of The Culture Corner between the covers of a single tome with that title (286 7x9-inch landscape pages, color; Fantagraphics hardcover, $22.99). “All” in this exemplary instance includes not only all of the published Culture Corner, but pencil roughs for unpublished (perhaps rejected) CCs and a couple successors derived from CC but never before published.

As a reprint compilation, the book achieves a distinction almost no other volume of its kind offers: almost every half-page strip, printed here one to a page, is accompanied by the pencil sketch that preceded the final art, the pencil drawing on the left facing the published version on the right in the book’s distinctive two-page spread design. As Monte Wolverton, himself a cartoonist (of the editoonery breed), explains in his introduction, his father sent a pencil version of his strip to Fawcett for approval, then produced and inked the final version if the rough was accepted.

Editor Gary Groth adds: “There are many roughs for which we do not have finished strips [41 to be exact, all published herein]; about these, we surmise that they were either rejected by the editor [at Fawcett] or never submitted (and therefore self-rejected by Wolverton).” He continues: “The strips are printed in the order in which they were drawn—based upon a handwritten chronological list by Wolverton [also published in the book]—and not in the order they were published.”

Wolverton fils observes that The Culture Corner was different from most comic book featurettes at the time: there were no continuing characters. “Each strip was a tabula rosa on which Wolverton could design the character to fit the problem. He particularly enjoyed producing The Culture Corner because he didn’t have to worry about a plot or story. Rather, his challenge was to identify some common problem, and then come up with an unlikely solution.”

So unlikely that you have to see them to believe them, and to that purpose, here are a few.

|

|

BASIL WOLVERTON, whose cartoons are so cartoony as to give veritable dictionary definition to the word, did not set out to become a cartoonist. “Born not long after the Civil War,” he wrote in the Membership Album of the National Cartoonists Society, “on July 9, 1909, in Central Point Oregon,” he “attended kindergarten quite a while but forgot to go to college.” But it didn’t matter: what he wanted to be was an actor—“preferably a comedian,” he said in an interview conducted by Dick Voll, published in Graphic Story Magazine, No. 14, a winter issue, 1971-72.

Wolverton seldom participated in any interview with a perfectly straight face, and on this occasion, having attained the antiquity of approximately 60 years, he forthrightly denied the rumor that he was an old man: “I did not ride up San Juan Hill with Roosevelt. My horse was too old to make the grade. I had to stay at the bottom of the hill and watch.”

He did, however, move from Central Point (between Medford and Grants Pass) to Vancouver, Washington, just across the Columbia River from Portland. As for his first ambition, he said: “Eventually, I heard or read that a two-bit actor earns even less than a two-bit cartoonist. Later, there were times when I wondered how that could be possible. Like everything else, cartooning has its headaches and obstacles, but it has more advantages than disadvantages. The one I like best is that I have the time and freedom to look for a job for my wife whenever she gets out of one.”

Fate, naturally, played a part. He sold his first cartoon at the age of 11; his first nationally published cartoon, when he was still in high school. It was published in America’s Humor, Wolverton said, “a contemporary of College Humor—in 1926.The cartoon showed a surgeon chopping a man in two with an ax. I was off to a delightful start.”

But after graduating from high school in 1927, he joined the staff of the Portland News as staff artist, reporter, and columnist (movie critic). In 1928-29, he successfully sold a comic strip into syndication with Independent Syndicate in New York. Entitled Marco of Mars, it was an unabashed space fantasy. Fate, again, took a hand: just before Marco could debut nationwide, another syndicate brought out another space fantasy—Buck Rogers.

“Its setting,” Wolverton recalled, “was Mexico hundreds of years in the future. Suddenly Mr. Rogers decided to go to Mars, flags flying from his ship as he sped through space. It was evident that Marco and Buck were going to arrive about the same time at Mars. This greatly disturbed the manager of the Independent Syndicate. He didn’t wish it to appear that we were trying to steal or imitate an idea; so he dropped the strip.”

Soon thereafter, the Portland News expired in the throes of the Depression, and Wolverton went on the vaudeville stage with the Pacific Northwest Circuit, doing a solo act called Goof and His Uke, his son told me. “When vaudeville died,” Wolverton pere continued, “I worked as printshop artist, railroad laborer, fruit cannery foreman, forest firefighter and hod carrier”—all the while sending cartoon material to syndicates, without success, and freelancing with ad agencies and novelty publishers. Married in 1935 (“or was it 1934?” Monte wondered), he went to Hollywood briefly in 1936 to work on a magazine published by movie actor Charles Ray; it fell through, and so did Wolverton’s application to work at Disney.

Wolverton next stormed the citadel of the Big Apple, leaving samples at United Feature Syndicate. In early 1937, Monte Bourjaily, former manager at United, formed his own syndicate, Globe, planning to market his features by means of a comic book (brochure) called Circus Comics. Asked to participate, Wolverton contributed two features, Disk Eyes the Detective and Spacehawks. Circus Comics folded after the third issue; and Globe spun out, probably because it was overloaded with features. Because Bourjaily wanted his infant syndicate to seem overflowing with talent, Wolverton signed his name to only Spacehawks; Disk Eyes was signed “Dennis Langdon.” Disk Eyes showed up again in 1943 and again in 1948 in comic books. And Spacehawks, completely revamped as Spacehawk (singular), ran for 30 episodes, 262 pages, in Target Comics, June 1940 through December 1942. Before that, however, another Wolverton sf creation, Space Patrol, debuted in Amazing Mystery Funnies in December 1939, running in seven issues and ending with the September 1940 issue.

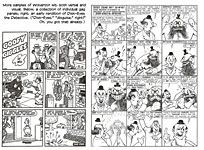

In 1942, Wolverton tried again to get syndicated with a strip about a reporter, Scoop Scuttle. “Just when the ad sheets were sent out,” he said, “there was a newsprint cutback because of the War. Scuttle was scuttled.” But he showed up in several of Lev Gleason’s comic books, and daily strips were cut up and reassembled as comic book pages at Timely Comics in Candy and Horsefeathers.

“After Circus, Amazing Mystery Funnies and Target,” Wolverton said, “sales came thick and fast. By 1942, there was more than I could handle. I’d started Powerhouse Pepper, among others. At one more, I worked seven days a week for seven months, and still couldn’t keep up.”

Apart from Spacehawk, Powerhouse Pepper was Wolverton’s longest running creation: it started in Joker Comics, No. 1, cover-dated April 1942, and appeared in numerous titles, including five issues of Powerhouse Pepper, accumulating 539 pages in 76 stories by the time Wolverton did the last one in 1948.

With Spacehawk, Wolverton was deadly serious: both story and art aspired to realistic adventure, and the cartoonist displayed a surefooted draftsmanship and confident line in drawings that were relatively simple outline formulations, elaborately enhanced by complex patterns of shading strokes. The storytelling was thoroughly competent: Wolverton’s pictures pace events deftly, and his compositions deploy variety of angles and distances for narrative as well as dramatic emphasis. Spacehawk himself never smiles. Unlikely as it may seem, he’s a flawlessly handsome matinee idol sort of leading man; he’s also physically and intellectually super-human. In one adventure, he performs brain surgery without a handbook. He uses mental telepathy to summon his faithful space aid, Dork. The plots are mostly melodramatic enactments of stunningly unlikely events. Spacehawk (who would reappear as Meteor Martin and, later, in a newspaper strip try-out, Shock Shannon) often enters the action by leaping into the fray from outer space, jumping into a scene like deux ex machina. Many of the foes he tackles in the early stories are thinly disguised Nazis; and after the U.S. got into World War II, Spacehawk confines his do-gooding to Earth, where he foils tire thieves on the home front and defeats bestial Japanese (“yellow buzzards”) at sea. These episodes were, Wolverton told Voll, his least favorite productions because he was taking direction from the publisher who told him it would be unpatriotic to have Spacehawk in space while the war was in progress.

Powerhouse Pepper was quite another hue of equinus. Powerhouse, said Voll, is Wolverton’s send-up of comic book superheroes. Like Spacehawk, he was super strong. But there, the similarities end like an exclamation point. Wolverton emphasized Powerhouse’s strength by giving him a bullet-head: from the turtleneck of his striped sweater, his head arose without a chin, like an extension of his neck. Ostensibly a boxer, Powerhouse was a smallish man, “a puny pest with the polished pate” as one of his opponents said once. He’s not particularly smart. in fact, his intellectual ability is merely ordinary. But he’s a good-hearted fellow, and his motives are uncomplicated by any desire for worldly goods (although he often happens upon wealth almost accidentally). Comics historian Don Markstein says Powerhouse is “kind, generous, and uninterested in worldly goods to the point where he once dug up an entire beach looking for a clam, and completely ignored the millions in buried treasure unearthed in the process.”

Powerhouse evokes memories of E.C. Segar’s Popeye: although he is physically more powerful than anyone he meets, he is, like Popeye, slow to anger, and only when driven to the last extremity does he finally uncork a whollop that settles the bad guy’s hash. And Powerhouse is always encountering bad guys. They are invariably brutish bullies, and they usually set about beating up Powerhouse until he gets tired of taking it. “That’s enough guff and stuff from that tough,” he says on one occasion, “—now I’ll get rough!” Powerhouse wins not so much by feats of strength but by his own indestructability: no matter what damage the bully inflicts upon him, Powerhouse seems wholly impervious. Nothing fazes him. But eventually, he’s annoyed into action.

The situations that prompt Powerhouse action are sometimes simple and unexceptional. He visits a dentist and finds himself struggling with both the dentist and another patient who wants to inflict pain. He enters a skiing contest. At a lunch counter, he finds himself sitting next to a rude guy who puts his elbow on Powerhouse’s stack of pancakes. When prospecting for gold, he must deal with another prospector who jumps his claim. Another bullying bloke tries to ace Powerhouse out of a treasure discovered by using a map Powerhouse finds in a book he’s reading. In another tale, Powerhouse foils the plan of a saboteur who tries to blow up an atomic plant.

The comedy in a typical Powerhouse adventure arises partly from the ridiculous extremes of the situations in which the bullet-headed battler finds himself, “kinetic slapstick comedic stories,” as Markstein puts it. The usual foe is a bully of monstrous mein, a genuine, four-star brute, without any redeeming compunction or grace. And the ever affable Powerhouse is niceness to the point of naivete incarnate. But the other ingredient in Powerhouse comedy was Wolverton’s use of language. The characters spoke in unrelieved alliterative rhyme, and the landscape was littered with punning signs and posters. Every panel contained a prompt to chuckle, creating a maniacally surreal backdrop against which the ludicrous extremities of Powerhouse’s predicaments play out relentlessly. Nothing else in comics matches Powerhouse. Nothing else achieves comedy in the Wolverton manner.

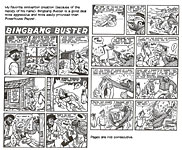

Wolverton’s oeuvre through the 1940s was almost all comedy, featuring a memorable list of alliteratively christened characters—Flip Flipflop the Flying Flash, Dr. Dimwit, Doc Rockblock, Prof. Ploop, Inspector Hector the Crime Detector, Leanbean Green, Mystic Moot and His Magic Snoot, Hash House Hank, Salesman Sid the High Pressure Kid, Dauntless Dawson, Prof. Jogg, Dr. Whakyhack the Wacky Quack, and (my favorite in name and adventures) Bingbang Buster and His Horse Hedy. A somewhat less exaggerated version of Powerhouse Pepper, Bingbang appeared in Black Diamond Western Comics, only 12 times, beginning in December 1949 and ending with the November 1951 issue. But his name belts out an unforgettable melody. Not so memorable was the name he bore for his reincarnation as a candidate for newspaper syndication, Hercules Hardy. Some of these characters appeared only once in the comic books of their debuts; some only twice or thrice.

Then came Lena the Hyena.

THE SHORTHAND TELLING of the tale is that Wolverton submitted a drawing in the contest Al Capp was running in Li’l Abner for a picture of the ugliest woman in the world, and Wolverton’s drawing won. But the longhand version of the story is somewhat more complicated.

The Li’l Abner storyline that culminated with the publication of Wolverton’s picture in October 1946 began six months earlier, at the end of March 1946, when Abner, a dedicated fan of fictional cartoonist Lester Gooch’s Fearless Fosdick, Capp’s send-up of Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy, wrote to Gooch, urging him to draw catastrophically homely women in the strip in order to compete with other, more popular, strips. Capp may have been taking another poke at Tracy: Gould had introduced the shudderingly ill-favored Gravel Gertie in the summer of 1944, and Gertie became a popular character. One of Tracy’s arch villains in 1945 had been Breathless Mahoney, who, we suppose, Gould had intended as an attractive siren of evil; but Capp, whose toothsome females were lusciously sensual, no doubt considered the angular Breathless just another homely Gould female contraption.

Gooch tries to produce a picture of an appropriately cacophonous woman but can’t. Then he learns of a supremely ugly woman, a native of Lower Slobbovia called Lena the Hyena. Thinking he might find in Lena the ideal model for a genuinely repulsive-looking female, Gooch goes to Lower Slobbovia and sees Lena. At first glance, he knows she’s ideal for his purpose. But now he’s trapped: in Lower Slobbovia, a man who sees a woman is compelled to marry her. Gooch refuses and is jailed.

Then Fosdick disappears from the newspaper because Gooch is incarcerated. Abner finds out what’s happened and goes to Lower Slobbovia, intending to marry Lena in Gooch’s stead, thereby freeing the cartoonist to resume his comic strip. But Lena declines the dubious honor: she jilts him because she’s been hearing on the radio a song—composed at the request of Abner’s unrequited paramour, Daisy Mae—the chorus of which pleads with Abner not to marry “that girl.”

This development takes place on June 15, two-and-a-half months after the Lena continuity was launched. This year of Li’l Abner was one of Capp’s best, a storytelling jag of more complexity and nuance than he usually put forth. He introduced numerous subplots and detours along the route of the Lena story, one of them being Daisy Mae’s “Don’t Marry That Girl!!” song. Capp insinuates more extraneous matter after Abner sees Lena, and the Lena tale does not resume until the end of August, two months after she has rejected Abner.

On August 20, we see Lester Gooch again for a single installment, and we learn that he did, indeed, draw Lena in his strip—but newspaper editors censored it, refusing to publish it. At the end of August, Gooch returns to the strip, vowing to draw Lena again. He does, but the strain of conjuring up a vision of the actual Lena for inspiration proves too much: Gooch collapses into fits of barking insanity. And his paper with Lena pictured on it blows out the window. For the next couple weeks, we follow the misadventures of the fluttering piece of paper. Then on September 21, Gooch’s syndicate asks readers to find the picture—“or, if they can’t, to send in their own version of Lena the Hyena. A jury of experts will select the worst of the lot, and that, undoubtedly, will be the real (ugh) Lena.” Her picture, we’re told, will be published on October 21.

For the intervening month, Capp visits Lower Slobbovia again (the natives decide to banish Lena to America) and stages the annual Sadie Hawkins Day race. He also assembles the panel of three judges—Boris Karloff, Salvador Dali, and Frank Sinatra. And they pick Wolverton’s drawing, which is published, forthwith, in the strip dated October 21. Here are highlights of the last spasms of the story.

|

|

Life magazine in its October 28 issue published Wolverton’s Lena and seven of the runners-up. The timing indicates a carefully wrought campaign: Life’s October 28 issue had to go to press just about the time Lena appeared in the strip. And that’s not all the evidence for a somewhat more elaborately conducted contest than the traditional telling of the tale suggests.

The dates of the key strips provoke suspicion about what was happening beyond its borders. The date of the unveiling of Lena in the strip, October 21, was announced in Li’l Abner on September 26, a mere four weeks prior—almost exactly the time between Capp’s deadline for submitting his daily strips and their publication date. That means, probably, that the strip for October 21 had to be submitted to the syndicate before the winner of the contest was determined: the October 21 strip was probably submitted on or about September 26. Capp doubtless left the last panel of the October 21 strip blank so the syndicate could insert the winning picture at the very last minute. Someone at the syndicate also lettered in the name and address of the winning artist in the preceding panel. Still, the contest had to be conducted and concluded at least a week before the winning picture was published. Perhaps newspapers carrying Li’l Abner actually announced the contest before the strip did on September 21.

And that’s not all that was transpiring behind the scenes of the strip. According to Life, many of the 381 newspapers that published Li’l Abner also ran Lena contests, or, perhaps, conducted “preliminaries.” Wolverton submitted seven candidates to the Portland Oregonian; and in that paper’s judgement, his submission was merely second-best, for which he collected only $25 in prize money. His pictures were subsequently sent on to Capp’s syndicate—and to judges Karloff, Dali and Sinatra, who picked the “balding, oily-haired, bush-browed, snaggle-toothed, boil-encrusted” (as Doug Harvey, no relation, put it) visage that has come down to us as the authentic portrait of the world’s most hideous-looking female of the human species. Wolverton thought the winning picture was “the tamest” of his submissions; but it won him $500.

Life and subsequent publicity claimed the contest garnered “half a million grisly entries.” If the judges actually looked at them all before picking Wolverton’s Lena, it must’ve taken longer than a couple weeks. In hindsight, without looking at, say, copies of actual newspapers that ran Li’l Abner that fall, the contest seems highly suspicious. Hanky panky might have been perpetrated all across the land. It seems probable, as I said, that in the newspapers carrying Li’l Abner, the contest was announced long before it was announced in the strip itself. Idle speculation at this point; but intriguing.

Incidentally,

Lena was not the only strangely visaged woman to appear in Li’l Abner. In 1951, Capp introduced Nancy O., a young woman with a pulchritudinous body

whose face was always averted so none of us, the strip’s readers, could see

what she looked like. The characters in the strip could see her, though, and

Li’l  Abner fell in love with Nancy O. the first time he saw her and promptly

announced his intention of marrying her. In the strip published March 20, Capp

shows us why.Subsequently, a plastic surgeon offers to replace Nancy’s face with another,

and Capp ran another contest—this time, asking readers to submit pictures of

the sweetest-looking girl they knew. The result, as we see, disappointed Abner

in the extreme. He didn’t marry Nancy O.; and he didn’t marry Daisy Mae until

March 29, 1952, the culmination of an 18-year “courtship.”

Abner fell in love with Nancy O. the first time he saw her and promptly

announced his intention of marrying her. In the strip published March 20, Capp

shows us why.Subsequently, a plastic surgeon offers to replace Nancy’s face with another,

and Capp ran another contest—this time, asking readers to submit pictures of

the sweetest-looking girl they knew. The result, as we see, disappointed Abner

in the extreme. He didn’t marry Nancy O.; and he didn’t marry Daisy Mae until

March 29, 1952, the culmination of an 18-year “courtship.”

FOR THE NEXT COUPLE OF YEARS in the wake of Lena’s ghastly debut, Wolverton picked up a lot of work—caricature assignments from advertising agencies, a national radio network, and movie studios. “At long last,” the cartoonist said, “I was able to afford an eraser for each hand and a real drawing board of my own. This was a happy event for my wife, who resented my working on her ironing board—especially when she was ironing.”

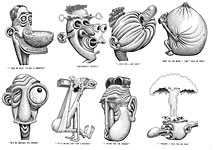

Wolverton was no slouch as a caricaturist. Hereabouts are some of his caricatures of both real and imaginary personages, including the one (upper left in the first line-up) for which he was, perhaps, the most renowned—John L. Lewis, the fiercely outspoken labor leader of the 1940s. Below Lewis, Thomas Dewey, racket-busting governor of New York, and Joseph Stalin, dictator of the Soviet Union.

|

|

The imaginary mugs on the second exhibit here are taken from a booklet entitled Barflize, wherein Wolverton depicts “common types that range the full length of the bar—and under the bar, where so many of these characters are often found and where every last one of them belongs,” as Stewart Holbrook claims in the booklet’s introduction. “I know them intimately,” he goes on, “but never before saw them with quite the blinding clarity that is one of Mr. Wolverton’s many gifts.”

Some critics fault Wolverton’s art because of its plethora of lines, alleging that “the little lines covered up his lack of ability.” Said Wolverton, a satirical tongue well in cheek: “I was dazed. I had always hoped that viewers would regard it as shading, and didn’t think even another cartoonist would get wise to the awful truth.”

But it was applause from appreciative fans that occupied him the most right after Lena’s unveiling: “I was awfully busy trying to answer fan mail from the Lena thing. In the end, I’m afraid I wasn’t that much ahead [financially], considering that it required days and days to answer mail. But material things aren’t all that count, and I was happy to have received so many communications from well-wishing people. I answered every one personally, even though it took me about six months, as I recall.”

He was mildly irked that articles about him after the Lena triumph alleged that the contest gave him a career as a cartoonist. “This was news to me,” he said. “I’d been drawing comics for national magazines for nine years, and had been a professional cartoonist for twice that long. Life later published two spreads of my work, for a total of five pages,” he went on. “They referred to me as ‘an adherent of the spaghetti and meatball school of design,’ by which the editors meant that the stuff looks just like that. The name stuck. In fact, it was somewhat exaggerated, and the agencies I later worked for referred to me in their national ads as ‘the creator of the spaghetti and meatball school of art.’ At least it was better than being refereed to as the father of Lena the Hyena.”

Despite the flush of Lena-inspired caricature jobs, Wolverton continued producing wacky comic book comedy for the rest of the decade. He concentrated on humor, he said, because “it was easier for me to do,” adding: “In cartoons one can go wild and people don’t criticize because there are no definite limits shapewise to what one is drawing.”

By 1948, he was working chiefly for only two comic book publishers, Timely and Fawcett. And he was doing work for two ad agencies, one in Portland, the other in Hollywood. “I also did caricatures for Universal-International Studios in Hollywood and for Samuel Goldwyn Productions. This kept me running up and down between [Vancouver] and Hollywood and made me forego my annual trip to New York one year.”

Wolverton enjoyed his yearly junket to the nation’s publishing capital, but his first trip there had been horribly revealing. Said Mad’s Jerry DeFuccio: “Once, when Basil ‘stumbled into New York,’ he was shocked to learn that one or two publishers were paying him only the going rates for the art. He should have been paid for ‘package jobs,’ writing the stories, penciling and inking the art, and doing the lettering. That had been conveniently ‘over-looked.’”

Wolverton realized he was at a disadvantage living and working so far away from New York. “No one else lived as far away as I did,” he said. “Publishers liked to have artists right under their thumbs at all times. That had its advantages for the artists, but I preferred foregoing those things in favor of the greater freedom I had.”

But he couldn’t help feeling a little resentful every once in a while. “There were times,” Wolverton admitted, “when I wished that I could have been the Invisible Man so that it would have been possible to sneak up and pliers-pinch all the editors and advertisers who had published or re-published my material without permission or payment. But who wants to be responsible for sore winners or losers?”

Wolverton almost always wrote as well as drew his stories, he said, “—with the exception of three or four for Martin Goodman [at Timely]. That wasn’t good because I didn’t think the way the writers did. I really don’t know if they were disappointed or gratified. I don’t imagine things in the same way that an author does, and his imagination might be superior to mine, in which event I wouldn’t really do justice to his story. Apparently the editor was satisfied. I can get along better with my own miserable imagination and without any arguments, misunderstandings and gripes. If an artist can do his own stories, jolly harmony results.”

Because he both wrote and drew his comics, Wolverton managed only about a page a day, about which he felt apologetic: “I could make two under pressure, but it wasn’t worth it,” he said, because then he wouldn’t have time to put in the detail he wanted at that rate. “I did, and still do [1971], everything myself. I used to think that when I started to slip downhill, I’d call on someone to help. But I never did. There’s nothing like doing a thing yourself if you want it done right, no matter how badly you may do it. It was a bit disappointing to see in New York, around the publishers’ offices, fellows who were capable of doing only one thing. It was, and is, the age of specialists, but it’s far better to be able to do several things than just one, as long as one can do them well. I realize my art isn’t good,” he added, “—it’s just a type of art and humor, and is pretty lowbrow and slapstick. But I do feel it’s just as funny as some of the other strips, including one or two syndicated ones.”

The distinctive alliterative rhyming dialog in a Wolverton comic “developed naturally,” the cartoonist said, “—because of my trying to dress up dialogue for my stuff.”

Wolverton’s favorite comics in the newspapers when he was young included Old Doc Yak by Sidney Smith, who later drew The Gumps. “And Hungry Hallie—no one I’ve contacted remembers Hungry Hallie, who flew around in a cigar-shaped airplane looking for food from other airplanes. That was imagination back in the years before World War I.” Later, he liked Buz Sawyer, Terry and the Pirates, and Prince Valiant. “Today [1971], I still admire the work of Roy Crane. and Walt Kelly, Al Capp, Johnny Hart, Ed Dodd. It’s good to have such a variety of styles. It’s like different kinds of music. There was a time when most of the comic book material began to look the same. It was discouraging. I could never have fitted in with that. As an untrained artist, it was beyond me.”

WHEN FUNNYBOOKS ABANDONED HUMOR for horror in the 1950s, Wolverton joined in the procession, beginning with “The End of the World,” created for Marvel’s Marvel Tales, cover-dated August 1951.

Wolverton’s weird fantasies were horrifyingly memorable. Said another disciple of the genre, Gahan Wilson: “Of course, I think Basil Wolverton’s work is magnificent. What macabre cartoonist wouldn’t? And of course he has been an influence. No small child exposed to his drawings, and I was a small child exposed to his drawings, could ever be expected to walk in a straight line again. Or vote a party ticket. I think Wolverton’s vision of the human physiognomy and the human back of the head is unique and absolutely ghastly. I am sure in day-to-day life, Wolverton is not a lycanthrope but a kind and gentle fellow, just as Boris Karloff was reputed to be, but I want to be armed the first time I meet him.”

Wolverton’s work also started appearing in Mad in the April 1954 issue. Although he wasn’t in Mad often enough to qualify as a “regular,” he nonetheless earned the sobriquet “The Michelangelo of Mad Magazine” from the New York Times.

Wolverton left comic books, he said, because rates were starting to drop—perhaps because of the emerging self-censorship imposed by the industry’s Comics Code Authority of 1954. “Even Powerhouse Pepper was ruled as too violent for reading,” Wolverton said. “I made the last episode in about 1952. [He may be misremembering; the last date I could find for Powerhouse Pepper was 1948.—RCH] ... I regretted having to leave comics, but there was beginning to be a realization that there was something better and more worthwhile closer to home.”

By this time, most of Wolverton’s creative energy he was pouring into drawing the Old Testament.

Wolverton usually listened to the radio as he worked, and he had heard Herbert W. Armstrong, founder of the Radio Church of God (later the Worldwide Church of God) soon after Armstrong had launched the evangelical enterprise in 1934. In 1941, Wolverton was baptized by Armstrong, and in 1943, he was ordained an elder in the WCG. A decade later, about the time Powerhouse Pepper stopped appearing in funnybooks, Wolverton, at Armstrong’s behest, began producing illustrations for the Book of Revelation. Soon thereafter, he started illustrating the Old Testament, a project that absorbed him until he finished it in 1972. (We reviewed The Wolverton Bible in Opus 238.)

Wolverton returned to comics briefly in 1973, drawing covers for Joe Orlando’s satiric Plop! at DC Comics. But he suffered a stroke in 1974, which presumably prevented him from returning full-time to the drawing board. He died in 1978, in Vancouver.

In his 1971 interview with Wolverton, Dick Voll asked him what he thought his best work was. “My best work technique-wise has been in caricatures,” Wolverton said. “Best satire, in Mad. Best comic book humor, in Martin Goodman’s publications. The best serious illustrations have been for Ambassador Press [publishers of The Story of Man, his pictorial Bible].”

His favorite comic book work: Spacehawk, Powerhouse Pepper, and “Eye of Doom,” that sf horror story. “As far as comic books are concerned,” Wolverton said, “I should like to be remembered for Powerhouse Pepper. In the over-all body of my material published, I prefer to be remembered for The Story of Man.”

Lucky Wolverton: those are among the works for which he is today best remembered—in our mind’s eye and in the ensuing Gallery. (For samples of The Story of Man, re-visit Opus 238; and for more mug shots, see Opus 259, wherein we reviewed The Original Art of Basil Wolverton.) After you’ve sauntered through the Gallery and feasted your eyes, keep scrolling down for an exhaustive explanation of the last exhibit—namely, four Li’l Abner strips that, while out-of-place in this Gallery, prompt a fascinating digression, through which we amble after the Gallery.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The last of our visual aids is not, as you can see, from the Wolverton oeuvre. It is, rather, from Li’l Abner, about mid-way through the Lena storyline. But I’m posting it here for reasons having absolutely nothing to do with either Lena or Wolverton. True, I found it while looking for Lena, but I’m including it because it deserves comment on its own, quite apart from the Lena storyline. It is perhaps unique in the annals of newspaper comic strips: it depicts a rape.

Al Capp was known to include sexually suggestive images in his strip—phallic noses, for instance, and vagina-like boles in gnarly trees; but here, he’s dipped into visual allegory. Daisy Mae is wandering the streets of the Big City in search of Abner (the “tall, dark young boy”), who has left Dogpatch to find his way to Lower Slobbovia to rescue Grooch. Ostensibly, the hipster and the old rich guy in this sequence want only to kiss Daisy Mae—kissing being Capp’s euphemism here for what they really want to do. And in the third strip, Capp comes as close as I’ve ever seen him come to depicting a sexual act. In that strip’s second panel, the old rich guy’s gesture with his right hand is superimposed upon Daisy Mae’s decolletage in such a way as to lend itself readily to misinterpretation: he seems about to grasp the neckline in his hand as if he would tear the blouse away from the toothsome girl’s bosom. (Yes, I confess: I’m exactly the Dirty Old Man to whom Capp addressed his furtive sexual imagery.) The rape then proceeds apace in the next two panels and into the next day’s strip as the thoroughly aroused old guy gropes Daisy Mae and then throws himself on her. Apart from the action itself, Capp’s rendering of his heroine—bare legs and shoulders and plunging neckline—imparts to the strip a patina of sensuality that heightens the sexual aura of the sequence. If this isn’t a rape scene, it can’t be just a spin-the-bottle kissing game.

On its most obvious level of harmless osculation, the sequence satirizes the carnal nature of even so-called civilized man—uncontrollable in the extreme when aroused. The old guy simply can’t help himself: once in the grip of his primal instincts, he must kiss the girl. Carnality is only an undrawn panel away. Subliminally, however, the carnal appetite is being satisfied in bodice-ripping fashion even as we watch.