THE TRUE

HISTORY OF EUSTACE TILLEY

And of Other

Fictional and Non-fictional “Characters” at the New Yorker

ALFRED D’ORSAY

was not the sort of fellow I’d invite into my home for a drink, dinner, and

deep philosophical conversation in the Rancid Raves Library over a vintage

bandy. Reading between the lines of even a short biography (such as

Wikipedia’s), we learn that Comte d’Orsay, while an amateur painter and

sculptor of modest attainment, was a calculating social climber and parasite of

somewhat more conspicuous success. He was the sort of fellow who would make off

with his host’s wife. And in fact, that’s exactly what he did—with an eye on

both her charms and her fortune.

Born

in Paris in 1801, son of a Bonapartist general and the illegitimate daughter of

a duke and an adventuress, D’Orsay entered the French army of the restored

Bourbon monarchy at the age of 20 and while in London attending the coronation

of George IV, he became acquainted with the first Earl of Blessington and his

wife Marguerite, reputedly forming a menage a trois, which may account for at

least some of his attraction for George Gordon, Lord Byron, who was rumored to

have indulged in a similarly illicit affair with his half sister, Augusta.

Byron praised Comte d’Orsay’s “gifts and accomplishments” and his knowledge of

men and manners and his prowess of observation. And probably envied the count’s

domestic arrangements.

At

26, D’Orsay married Blessington’s 15-year-old daughter Harriet by a previous

wife, hoping to secure a claim to the Blessington estate, but when Blessington

died two years later, his widow took up with D’Orsay, and the two of them

established a fashionable salon for the literary and artistic society of

London. Harriet, finally having had enough, separated from D’Orsay in 1838,

effecting a settlement in which, in exchange for her paying off 100,000 pounds

of his debt (about $150,000 at today’s exchange rate, but only a portion of

what he owed), he gave up any claim to the Blessington fortune.

At

his salon, D’Orsay met Benjamin Disraeli and Edward Bulwer-Lyton, other young

dandies of the day, and they became such friends that Disraeli asked him to be

his second when it appeared he would fight a duel with the son of an Irish

agitator. D’Orsay, however, declined the dubious honor on the grounds of being

a foreigner.

Comte

d’Orsay went bankrupt in 1849 and returned to Paris; Marguerite, after selling

all her possessions, followed him there but died a few weeks later, leaving him

heartbroken and without means. He dabbled in portrait painting, but as a

Bonapartist, he probably banked on his acquaintance with Prince Louis Napoleon,

who had been elected President of France in 1848, subsequently, in 1852, through

a coup d’etat, establishing himself as Emperor Napoleon III. Leery of D’Orsay’s

dependability, Napoleon appointed the count to the harmless post of Director of

the Beaux-Arts, but D’Orsay died of a spinal infection just a few days after

the appointment was announced.

In

his day, D’Orsay was a model of men’s fashion but scarcely a model of decorum

and propriety. With his appetites and indulgences, he may, however, have been

right at home in New York’s Roaring Twenties. In fact, by a circuitous route, he

was exactly that. Which brings us, by the sort of oblique roundabout manner of

the writers of articles in The New Yorker, to Eustace Tilley, the actual

subject of this posting.

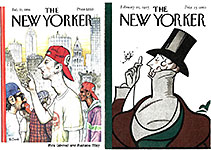

Eustace

Tilley is the name given to the 19th century boulevardier languidly

inspecting a passing butterfly through his monocle on the cover of the first

issue of The New Yorker dated February 21, 1925. The same picture

appeared on the magazine’s anniversary issue every year until 1994, when a new

editor at The New Yorker, Tina Brown, suddenly violated

hide-bound tradition by replacing Tilley with a 20th century version

of the boulevardier, a chronic slacker and layabout drawn by Robert Crumb.

Nothing was ever the same at The New Yorker since. Nothing was ever the same at The New Yorker since.

Crumb’s

drawing arrived at the magazine without explanation, said art director Francoise

Mouly. “We noticed that it showed the view in front of our old offices on

42nd Street, but we didn’t realize that it was also a play on Eustace

Tilley.” Understanding that the picture was a parody of Eustace Tilley, Brown

seized upon it as a way of breaking a 69-year logjam: she put Crumb’s Tilley,

subsequently christened Elvis Tilley, on the cover of that year’s anniversary

issue.

As Lee Lorenz, one-time cartoon editor at the magazine told me, Eustace

Tilley appeared on the cover of the anniversary issue because no one could

think of an appropriate alternative. So year after year, Eustace Tilley

returned. Without too much difficulty, we can see how this custom had become a

habit. It was Harold Ross’s fault.

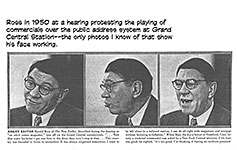

Without

question, Harold Ross was the world's most unlikely candidate for

editor-founder of the nation's most sophisticated magazine of humor and

urbanity. A frontier kid with only a tenth-grade education, he was born

November 6, 1892, in Aspen, Colorado, then a mining camp. The Ross family moved

around to some small Colorado towns, and then to Salt Lake City, where Harold

attended high school but never graduated; he quit school after his sophomore

year and went into newspapers. In high school, he’d worked on the school paper, The Red and Black.

There,

he met the other Salt Laker who would influence cartooning in America—a teenage

artist three years older than he, John Held, Jr., who was born and

raised in Salt Lake City.

They

became friends and both were stringers for the Salt Lake Tribune while

in school, and they were sometimes sent to the Stockade, the old redlight

district, to interview such stellar attractions as Ada Wilson, Belle London,

and Helen Blazes. For more on this adventure, visit Harv’s Hindsight cited

below.

When

Ross left Salt Lake City as a teenager, he became a slovenly tramp newspaperman

who spend his years before World War I roving from one newspaper to another, a

common type in those years. By the time he was 25, he had worked for at least

seven papers around the country; then he joined the American Expeditionary

Force attacking the Hun in Europe.

During

the War, he worked on Stars and Stripes, the armed forces newspaper,

where he was nominally managing editor. The staff was a convivial crew, and

after the War, they all landed in New York; there, Ross was encouraged to

launch, after a false start or two editing other magazines, The New Yorker.

The magazine struggled in fiscal red ink for years, but Ross never wavered in

pursuit of his vision. (You can find more of the history of the magazine’s

founding in Harv’s Hindsight—for October 2004, masquerading as a

history of gag cartooning, and for February 2009 in the story of doughboy

cartoonist Wally Wallgren.)

Ross

remained throughout his life the same contradictory sort—a rowdy, gangly,

mussed-up hick-looking wight with electric hair (a sort of brush cut standing

on its ends), Hapsburg lower lip, gap-toothed grin, a droll sense of humor, and

a profane vocabulary. In both his uncouth eccentricity and sheer doggedness,

Ross was without equal in American journalism.  He was also very, very lucky. He was also very, very lucky.

Ross

knew what he wanted The New Yorker to be, but he couldn’t articulate his

vision in order to guide his writers and cartoonists. So they all fumbled

around for several months and a couple years until something started to gel.

Eustace Tilley was one of Ross’s first fumbles. And it turned out to be a very

lucky fumble.

By

mid-February 1925, the first issue of The New Yorker was ready to go to

the printer. But it lacked a cover. “Ross toyed with various concepts for this

crucial first cover,” said Ross’s biographer, David Kunkel in Genius in

Disguise, “and he asked several artists to work up sketches on what

amounted to a dreadful visual cliche, a curtain going up on Manhattan. What he

got back was predictably static and maddeningly literal.”

At

the last minute, Ross turned, luckily, to his art editor, Rea Irvin.

IRVIN WAS BORN

August 26, 1881, in San Francisco, California, to which his parents had

journeyed by covered wagon in the 1850s. Although Irvin attended Hopkins Art

Institute in San Francisco, he also entertained the idea of a career in acting,

which he pursued briefly beginning in 1903. He then served in the art

departments of several newspapers, including the Honolulu Advertiser,

but eventually, he moved to New York, and by the 1920s he had achieved a good

measure of success as a newspaper and magazine cartoonist, becoming art editor

of the humor magazine Life. His thespian inclinations remained, however,

finding expression in his theatrical manner of attire and in his demeanor,

which radiated the stage presence of an accomplished actor. A lumbering bear of

a man albeit soft-spoken, he was a familiar figure at both the Players Club and

the Dutch Treat Club.

As

Ross refined his plans for The New Yorker in the latter months of 1924,

he enlisted Irvin to help with the art chores. Irvin, who had just been

replaced as art editor at Life, had a flourishing freelance art

business, but he agreed to serve as "art consultant" (Ross eschewed formal titles), stipulating that he could afford to give only

one day a week to the task, for which he was paid $75 and shares of the

magazine’s stock.

The

day that Irvin gave to the magazine every week was the day he helped Ross

select the cartoons for the next issue. The "art meeting" was "one of the great New Yorker institutions," according to Russell Maloney, a member of the staff for many years who, in the

August 30, 1947 issue of The Saturday Review of Literature, described

the process, "hardly changed by the passage of the

years," by which the cartoons are selected.

"The art meeting has always been attended

by Ross and Irvin, the first art editor. The current art editor attends; so

does one of the fiction editors; Mrs. White does if she is in town. [She's E.B.

White's wife, who was Katharine Angell when she started editing fiction and

poetry shortly after the magazine began.] These people sit four abreast at a

conference table, while the [cartoons], one after another, are laid on an easel

in front of them. At each of the four places at the table is a pad, pencil,

ashtray, and knitting needle. The knitting needle is for pointing at faulty

details in pictures. Ross rejects pictures firmly and rapidly, perhaps one

every ten seconds. 'Nah ... nah ... nah.' A really bad picture wrings from him

the exclamation 'Buckwheat"' —a practical compromise between the

violence of his feelings and the restraint he feels in the presence of Mrs.

White or a lady secretary [taking notes on the proceedings]. 'Who's talking?'

he will ask occasionally; this means that the drawing will get sent back to the

artist to have the speaker's mouth opened wide. Now and then Ross gets lost in

the intricacies of perspective. 'Where am I supposed to be?' he

will unhappily inquire, gazing into the picture. If nobody can say exactly

where Ross is supposed to be, out the picture goes."

Irvin's

taste in art was expansive: he liked classic and modern art, he was sympathetic

to anything new, and he knew good craftsmanship when he saw it. Moreover, he

was articulate about art: he could tell artists specifically what to do to

improve their work and to make it acceptable to the magazine. When a drawing

amused him during the art conference, he chuckled; and he often gave little

lectures on art appreciation. Irvin's presence and his manner undoubtedly educated

Ross in the subtleties of cartooning, refining the editor's taste and raising

his standards.

In

his 1959 book, The Years with Ross, James Thurber, assessing

Irvin's contribution to the magazine, says unequivocally that Irvin "did

more to develop the style and excellence of New Yorker drawings and

covers than anyone else, and was the main and shining reason that the

magazine's comic art in the first two years was far superior to its humorous

prose."

In

her Defining New Yorker Humor, Judith Yaross Lee agrees that Irvin was

essential: noting his "taste for ironically related images and

text," she goes on to say that _what is often

called the 'New Yorker cartoon' deserves to be called 'the Irvin

cartoon.'"

Since The New Yorker style of cartoon set the pace for American magazine

cartooning since the early 1930s, Irvin looms large in the history of the

medium as a major influence. In fact, he might even be said to be the "father" of modern magazine gag cartooning (see the aforementioned history of gag

cartooning in Harv’s Hindsight).

IN TURNING TO

IRVIN for the magazine’s first cover, Ross asked for a picture that “would make

the subscribers feel that we’ve been in business for years and know our way

around,” said Dale Kramer in Ross and the New Yorker—“anything that

might suggest sophistication and gaiety,” added Kunkel. Over the months of

preparation for The New Yorker’s debut, Irvin had prepared the layout

for the first issue and designed the distinctive typeface for the magazine,

modifying a face developed by Carl Purington Rollins. He also drew most of the

department headings, including, for the first section of the magazine (called,

initially, Of All Things), a monocled Regency-era scribe in a high collar with

his nose in the air. The same personage is shown gazing through his monocle at

an assortment of thespian caricatures for the Theatre department.

|

|

About

the owl: I have no idea why an owl figures so importantly in all of the Talk of

the Town headings. Is it intended to suggest a “night owl,” a creature of the

evening and wee hours, haunting speakeasys and saloons? Whatever—whoever (“who,

who”?)—the owl has been as faithful an attendant at The New Yorker as

Irvin’s dandy; he’s there even today, winking at us conspiratorially.

In

waiting until the last possible minute before enlisting Irvin for one more try

at a cover illustration (he’d already done one of the lifeless curtain

raisers), Ross hadn’t given his art editor much time. Desperate, Irvin went

back to his files for the pictures that had inspired the 19th century dandy that headed two of the magazine’s departments. Since the

character appeared twice in the first issue already, why not on the cover too?

Irvin might have settled for something similar to the cover he drew for Life the previous fall, instead he turned again to an 1834 caricature of the Comte

Alfred d’Orsay at the height of his stylish influence (bringing us, in the

manner of New Yorker writers, back again to the otherwise wholly

superfluous, but tenuously, slyly, pertinent paragraphs of our opening gambit).

Irvin

again added a monocle to signify supercilious intellect and, this time, a

butterfly for whimsey, producing an elegant emblem of insouciant detachment.

(This incarnation of D’Orsay seems harmless

enough that we might invite him to dinner—only to discover, doubtless, that his

conversation was so vacuous that we could tolerate his company only once a

year.)

Irvin’s

picture was perfect. The perfect portrait of a seeming sophisticated

man-about-town who is so vapidly empty-headed as to find a fluttering insect an

object worthy of minute inspection. What prospective first-time reader-buyers

thought of this incongruous picture when they saw it on the newsstand, we

can’t, with authority, say. Certainly they knew nothing about the Comte d’Orsay

or his vaguely shady but entirely extraneous machinations of the previous

century, so they were no doubt baffled by the image of a man dressed in the

height of 19th century fashion covering what purported to be a

magazine of contemporary jazz age sophistication and wit.

But

what they thought, at this last minute of preparing the first issue for the

printer, was, like everything we now know about Comte d’Orsay, irrelevant.

Ross, knowing nothing of d’Orsay, loved the drawing. Despite the time-warped

attire, Irvin’s picture of a would-be sophisticate gently ridiculed the very

people the magazine aimed to appeal to, embodying exactly Ross’s intention.

Irvin’s dandy set the tone and intent for everything that followed—within the

first issue and all subsequent issues.

Ross

always said Irvin’s cover was the best thing in the first issue. It was so apt

an emblem for the magazine that no one could ever think of a suitable sequel to

use for the ensuing anniversary issues. In fact, until the first anniversary

issue, probably no one had given any thought to anniversary issues. That the

magazine had survived a year since its debut, running deeply into the red, was

miraculous, so to celebrate the miracle, Ross and his cohorts no doubt decided

to repeat the cover image of the first issue as a gesture of defiant

triumph—“Look at me" I’m still here, snooty and distant as

ever.”

Perhaps

for substantially the same reason, Ross repeated the cover again on The New

Yorker’s second anniversary and then the third, by which time, the magazine

was running a little in the black. The habit was formed. Thereafter, Ross ran

the same cover every year on the last issue in February. And until the advent

of Tina Brown, Ross's successors did the same in honor of the founder (and of

Irvin). So Irvin's haughty dandy, anachronistically attired in top hat and high

collar, graced the cover of America’s most urbane weekly magazine once a year

for nearly 70 years. And he continued to appear inside every issue of the

magazine in the heading for the opening section, Talk of the Town. Still does.

But

Irvin’s Regency dude didn’t get a name until he was almost six months old.

IN THE SUMMER

of 1925, Ross had another of his routine fits of exasperation—this time, about

“the goddam inside cover” of the magazine, which was “embarrassingly empty of

advertising” as Judy Yaross Lee puts it. So he asked humorist Corey Ford to

fill the page with comical subscription promotions for the magazine.

Ford

would become an occasional diner at the famed “round table” lunches of writers,

actors, critics and other wits (among them, Robert Benchley, Dorothy Parker, Alexander

Woollcott, cartoonist Ralph Barton and, often, Ross) that were held daily

through the 1920s at Manhattan’s Algonquin Hotel just a block away from The

New Yorker’s offices.

“Although

Ross was liked by the Round Table group,” Ford wrote in his 1967 memoir, The

Time of Laughter, “its members did not take him seriously, and his raffish

face and gawky manner made him the butt of continual ‘joshing’ as he called it.

Woollcott [another fugitive from the WWI Stars and Stripes, who, with

Ross and his wife and a fourth cohort, co-owned the midtown apartment they all

lived in], considered Ross his personal protégé and described him as ‘a

dishonest Abe Lincoln.’”

Ross

may have been ribbed for his country-boy appearance and demeanor, but he

regularly moved in celebrity circles. The apartment he lived in was designed by

its tenants who remodeled it, connecting two adjoining brownhouses, and it

became a gathering place for artists and literary types, including such

dignitaries as George Gershwin, Edna St. Vincent Millay, F. Scott Fitzgerald,

Irving Berlin, Dorothy Parker and Harpo Marx

Ford,

who would soon make his way into this exalted company, was born and raised in

New York City and had just graduated from Columbia where he edited the campus

humor magazine, Jester. He would eventually author 30 books and over 500

magazine articles, mostly humorous, but in 1924, he was peddling his comedy

around town to humor magazines like the old Life and Judge. At

the latter, he met and grew to like Ross, who was then enduring his brief

frustrating tenure as that magazine’s editor.

In

his memoir, Ford confessed that “it is hard to say what inspired my immediate

confidence in Ross. He looked like a bucolic bumpkin, his features plain to the

point of being homely, his big hands flailing in all directions to bolster his

inarticulate speech. Often he would leave a sentence unfinished, and fling both

arms aloft in utter futility. He was always perched on the edge of his chair

ready to leap up and start pacing the room in restless pursuit of an idea. Even

when standing in one spot, he managed to remain in motion, jangling a pocketful

of keys and loose change or stabbing the air with a forefinger or banging the

desk as his voice rose to a squawk.

“Ross

seldom laughed aloud. If something amused him, his upper body heaved

spasmodically a couple of times, and his heavy lips parted in a broad silent

grin, showing large teeth with a gap in the center. He wore his coarse brown

hair brushed upright to a height of three inches; and now and then, when he was

embarrassed or frustrated, he would rub a hand across his face and comb his

fingers back through the thatch of hair in one prolonged gesture of confusion,

or explode with a heartfelt ‘Jesus"’ and then grin at his own ineptness.

“His

language was a curious admixture of roundhouse oaths and bits of antiquated

slang which dated back to my earliest childhood—bughouse, spooning, stuck on

her, sis. After a tirade, his mobile face would light with sheepish amusement

and he would sigh, ‘God, how I pity me.’

“It

was his balancing sense of humor about himself, I think, that made him a great

editor, another of the half-dozen greatest I’ve known. ‘All right, Ford,’ he

would conclude an interview with me, waving a limp hand in dismissal, ‘God

bless you.’”

In

picking him to fill the hole on the inside cover, Ford said Ross was recalling

a “random series” Ford did “on the Fugitive Art of Manhattan—beards and

moustaches on subway ads, chalked sketches on brick walls, doodles on Wall

Street blotters, and the like. In his impulsive way, he called me into his

office and began jangling coins and pacing the floor. Could I do a series of

promotion ads to fill the goddam inside cover. Have the first one by tomorrow?

Done and done. God bless you.”

Irvin

suggested to Ford that he use the inside cover to parody the kind of burlesque

in-house testimonial that Vanity Fair was then running. Ford obligingly

produced twenty-one “chapters” (including an unnumbered Introduction) in an

epic entitled “The Making of a Magazine.” Each chapter delved into some arcane

aspect of the magazine’s production: beginning with “Securing Paper for The

New Yorker,” Ford discussed in exhaustive pseudo-scientific detail how

paper is made from wood and from rags, how ink is obtained from squids, how

type is “mined” deep underground, how the pages are bound together, how

punctuation marks are cultivated, how contributors are nurtured, and so on.

Before

getting into these mechanics of magazine production, Ford assembled some

statistics (“the Funny Little Things”) testifying to the immensity of The

New Yorker’s circulation.

“Here

it is Friday,” he commences, “and at a rough estimate, there have been probably

thirty or eighty millions of people who have bought The New Yorker since

last night; and the returns from Maine are not due till tomorrow. This means

that if you add all these figures together and multiply them by the number you

just thought of, then the card there in your hand is the eight of clubs.”

At

the time, the circulation of Ross’s brain child was minuscule, scarcely between

“thirty or eighty” (which?) millions.

Not

content with perpetrating a paragraph of this ludicrous nonsense, Ford forges

on: “Perhaps the following illustration may serve to bring home to the average

mind the magnitude of these figures: first, conceive in your mind’s eye the

entire population of New York, New Haven, Hartford and a fourth city about the

size of Pittsburgh (let us say, Pittsburgh), and picture them arranged kneeling

side by side single file in a long line, all blindfolded and holding in their

hands the combined output of the New York Times, the Saturday Evening

Post, and Dr. Frank Crane. Now suppose that someone were to sneak up and

give the first man in line a sudden shove. Why, over they all would go like so

many nine-pins, and wouldn’t it be fun though?”

He

concludes with a promise to conduct a “tour” through the “great organization

behind that circulation, making stops at Tennessee and other points of interest

along the way. ... For this trip we should advise a complete change of

clothing, two blankets, and comfortable footwear, since there is nothing so

important on a journey as easy feet except (ah, yes)—The New Yorker.”

And

here, amid the concatenation of increasingly meaningless statistics, we first

see “Mr. Tilley.”  He appears in an illustration that compares a towering stack of New

Yorker magazines (B) to the Leaning Tower of Pisa (A). Because Mr. Tilley

is included chiefly to provide a human dimension against which the height of

the two towers can be compared, he is pictured at a monstrously diminutive

size. We can see only that he wears a top hat and carries a cane and is

referred to as “Our Mr. Tilley.” No first name yet. And he isn’t mentioned in

the surrounding text at all. He appears in an illustration that compares a towering stack of New

Yorker magazines (B) to the Leaning Tower of Pisa (A). Because Mr. Tilley

is included chiefly to provide a human dimension against which the height of

the two towers can be compared, he is pictured at a monstrously diminutive

size. We can see only that he wears a top hat and carries a cane and is

referred to as “Our Mr. Tilley.” No first name yet. And he isn’t mentioned in

the surrounding text at all.

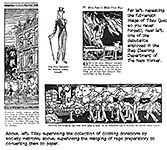

In

the next chapter of Ford’s “Tour through the Vast Organization of The New

Yorker,” Tilley is pictured directing the cutting down of trees for making into

paper. Compared to the size of the trees, he is still pictured very small, but

we can discern a top hat, cane, and cut-away coat—formal attire. And the

caption tells us that he is “Our Mr. Eustace Tilley.”

According

to Ford in his memoir, the last name he borrowed from a maiden aunt. And he

says he chose the first name “for euphony,” a patently false but lugubriously

comical claim. Eustace is scarcely euphonious with Tilley. Instead, the

assertion reveals only Ford’s penchant for word play: euphony = Eustace. More

likely, he chose Eustace because he liked the high-toned but vaguely effete

sound of a fraternity brother’s name, Eustace L. Taylor.

While

Eustace Tilley is named in the text of most of the other chapters in Ford’s

saga and appears in the illustrations accompanying all of the rest of the

series, we don’t get a good look at him until Chapter XVII, when he appears in

close-up; and the last chapter provides a portrait at full length.  Close-up, Ford’s

Tilley looks absolutely nothing like Irvin’s Tilley. In the last chapter’s

portrait, we see the top-hatted figure in a cut-away coat, striped trousers and

spats, carrying a cane and wearing—a monocle. Close-up, Ford’s

Tilley looks absolutely nothing like Irvin’s Tilley. In the last chapter’s

portrait, we see the top-hatted figure in a cut-away coat, striped trousers and

spats, carrying a cane and wearing—a monocle.

The

monocle is the only physical evidence that Ford’s “Our Mr. Eustace Tilley” is

the same as Irvin’s cover creation. In fact, of course, they aren’t the same at

all. Ford’s Tilley is a 20th century fop-about-town; Irvin’s is an

elegant refugee from the early years of the previous century.

Ford’s

Tilley is drawn throughout the series by Johan Bull, who had recently

been added to the magazine’s staff having just immigrated to the U.S. from his

native Norway; for Talk of the Town, Bull supplied spot drawings, wonderfully

deft and clean-cut renderings.

He also illustrated longer articles in the magazine with

supple wash drawings, and he produced two-page “cartoon essays” (groupings of

cartoons all illuminating the same subject) in naked linear style. He was

remarkably versatile, resorting sometimes to an entirely different sketchy

manner for cartoons.

Bull

may have been, after Irvin, one of the most accomplished artists to work in the

cartoon form in the early New Yorker. Bull’s crisp drawings show up in

various other American magazines of the day, but he seems, unaccountably, to

have disappeared from New Yorker annals altogether: he shows up in none

of the reprint tomes that started coming out in 1928. His last cartoon for the

magazine appeared in the issue dated October 22, 1927; his first, July 4, 1925.

(We’ve included a portfolio of his New Yorker art in our Rancid Raves

Gallery down the R&R scroll.)

Bull

was in good company in those early years. The magazine featured much more

purely decorative art, illustrative only in the sense that pictures of festive

restaurant diners might accompany an article about New York nightlife. Reginald

Marsh often supplied ash-can scenes of city street life spread across the

bottoms of the two facing pages that followed the Talk of the Town opening.

Two-page spreads of cartoon essays were common. Helen Hokinson, famed

for her matronly ladies, provided a couple such spreads during that first

summer, neither featuring her plump, doughy matrons; one was a visit to the

beach, and the sun bathers were all young people; the women, shapely rather

than dumpy.

Spot

drawings were not tiny inserts as they are today: in the early issues, spot

drawings took as much space as their subjects needed. During the notorious

“monkey trial” in Dayton, Tennessee, which unfolded during The New Yorker’s inaugural summer, caricatures of William Jennings Bryan sometimes broke

up columns of gray type the content of which had nothing to do with the Scopes

Trial. Almost in the manner of editorial cartoons, the drawings themselves

commented on the evolutionary questions being addressed.

Page

layouts under Irvin’s watchful eye were much more free-spirited, particularly

in the several pages of Talk of the Town: layouts continually changed to suit

lavish display of the art, the subjects of which were often merely tangential

to the prose surrounding them.

Cartoons

were only part of the magazine’s visual content. Eventually, most of the

visuals were cartoons—until Tina Brown arrived. Then, overnight, photographs

were introduced, and other kinds of decorative art showed up throughout the

magazine.

BUT, TO RETURN

to our Tilley history and the identity question we left dangling: how do we

connect Ford’s Eustace Tilley that Johan Bull attires in modern dress with

Irvin’s cover drawing of a Regency boulevardier in 19th century

garb? How did the name get transferred from one to the other?

The

conundrum is all the more puzzling when we notice that the dandy of Irvin’s

design appears in every one of Ford’s chapters as a decoration at an upper

corner of the border surrounding the treatise. Two Tilleys? Or only one—the one

in modern dress, the only one given a name?

We

don’t find out that Irvin’s creation is Eustace Tilley until someone at The

New Yorker tells us that’s his name. And exactly when that happened, I

can’t say. Ford doesn’t know either: he says only that “in time, Irvin’s

creation became known as Eustace Tilley”—without remarking at all upon the

discrepancy in the appearance of the two characters. And so, with no more

evidence than a monocle, the lepidoptera fan, himself more social butterfly

than the object of his lassitudinal gaze, came to be called Eustace Tilley; his

namesake, “Our Mr. Eustace Tilley” of Ford’s put-ons, faded in memory and in

fact.

But

before we leave him behind, let’s glimpse the comedy of Ford’s essays, all

worth more exposure than they ever get. And here, we accompany these excerpts

with some of Bull’s illustrations—by way of giving the only authentic Eustace

Tilley, an otherwise airy nothing, a local habitation and a moment of fame.

Here’s

the conclusion of Ford’s discussion of “Securing Paper for The New Yorker”:

“Although

most of the paper is made nowadays from trees, nevertheless, there is a certain

percentage which is made the old way, by picking it up here and there. The

material best suited to this work has been found to be an oblong sheet of green

paper issued by the United States Government and bearing the words ‘Five

Dollars.’ From this single scrap, enough paper can be procured to print 52

copies of the magazine; and to any reader who will submit such a bill to The

New Yorker, the editors will mail a year’s subscription free.”

A

year’s subscription, we rightly conclude, is $5. Some of Ford’s essays plug

subscriptions, but not all; restraint is the mark of the sophisticate, even the

mock sophisticate.

Nurturing

forests of trees to make into paper requires a vast number of “paperjacks”—so

many that “an area equal to half the State of Kansas is needed to raise

sufficient grain to feed these men and an area equal to the other half of

Kansas is needed to clothe them. To meet this problem it was necessary for The

New Yorker to purchase Kansas, at considerable expense.

“The

merry paperjacks often indulge in friendly contests of skill, testing their

prowess in chopping with the axe. Fred, a powerful Canuck, who if laid end to

end would reach six feet four in his stocking feet, was recently declared the

champion paperjack.”

Our

Mr. Eustace Tilley is the Field Superintendent of paperjacks.

It

is subsequently discovered that “the very best paper is made from rags,” which

causes a massive adjustment in the production of the magazine. Gathering rags

suddenly takes precedence over chopping down trees. “In the early days, the

editors gave their shirts, handkerchiefs and socks to be made into paper.” But

the supply was soon exhausted. “At this crucial moment, a young member of the

staff entered the room clad only in a barrel, bearing in his outstretched hand

the remainder of his clothing,” which he donated to the cause.

In

the accompanying illustration, “Our Mr. Eustace Tilley, Director of the

Committee on Paper Shortage, may be seen supervising the collection of

offerings by society matrons who gave their finery to relieve the paper

shortage of 1882.”

The

next chapter is devoted to a description of how rags are made into paper.

Bull’s illustrations show “one of the many debutantes employed in the Rag

Cleaning Department of The New Yorker. On the table may be seen the hat

and gloves of Our Mr. Eustace Tilley, one of The New Yorker’s Directors-in-Chief of Rag Cleaning.”

Another

illustration shows “the thrashing and mangling of rags from which paper is

made. In the background may be discerned Mr. Eustace Tilley himself.”

When

pondering “the actual work of printing itself,” Ford emphasizes the importance

of type: “Were it not for type, The New Yorker would have to be printed

in pictures instead, and probably would sell for two cents in the subway like

the illustrated Graphic, sometimes laughingly referred to as a

‘newspaper.’”

The New York Evening Graphic, founded only a year earlier, in 1924, by Bernarr

Macfadden, a physical cultist, was notorious for its doctored photographs, many

of which faked scandalous scenes involving well-know personages.

Before

the discovery that letters of the alphabet must be mined “far underground,” the

magazine “obtained its letters from alphabet blocks, noodle soup, or even the

monograms on the editor’s watch and cuff links; and letters were used

sparingly, hell being spelled ‘h–l’ and damn ‘d—m’ in those times.”

Then

a prospector in Chile, “while washing out the dirt at the bottom of a stream

preparatory to taking a bath, suddenly discovered two R’s, a Y and a battered

figure which might have been an E or an F or part of an old bed spring. Seizing

his pickax, he struck down into the earth and uncovered a rich vein of alphabet,

including the letter S, which had been missing up to that time, our forefathers

using F instead of S, as for example ‘Funny face’ for ‘Sunny face,’ followed by

a sock on the jaw.”

Alas,

the “rich vein of alphabet” was missing W, resulting in the magazine being

called The Ne Yorker until “the memorable (will we ever forget it?) late

afternoon of Thursday, August 26, 1823, when young Joseph Pulitzer,

while putting his head between his legs to avoid a playful ceiling draught,

considered the problem from a new angle and discovered that what was being

exploited as an M vein was really a rich strain of inverted W. By turning the

dredging machinery upside down and working it standing on their heads, our

workmen were able to mine excellent W’s from then on.”

In

Bull’s accompanying illustration, “Our Mr. Eustace Tilley, Field Superintendent

of Type Mining [attired, as always, in cutaway coat, striped trousers, top hat

and monocle], may be seen in the background registering polite, though

conservative, surprise.”

No

effort is spared in the mining of letters, we are assured. “In The New

Yorker type mines, operated by the Type Representative Mr. Eustace Tilley,

one letter receives just as much attention as the next and is read and answered

personally by Mr. Tilley himself. Sometimes these letters contain a five-dollar

bill and to all such correspondents, Mr. Tilley invariably mails back a year’s

subscription, just to show his appreciation and good will.”

In

the next chapter of his disquisition, Ford takes up the matter of arranging the

letters into words and words into sentences. “Sentences in The New Yorker vary

in length from six inches to six months or $100 fine or both.”

Bull’s

illustration shows “a group of The New Yorker’s highly-specialized

General Utility Men puzzling over the carefully selected bench-made syllables

which will eventually be put together as words, sentences and articles. In the

left background may be seen Our Mr. Eustace Tilley, one of The New Yorker’s staff

of Syntax Engineers.”

In

succeeding chapters, we learn that punctuation marks are cultivated at a farm,

and that at its founding in 1867 (the date varies from chapter to chapter), the

magazine was delivered by the editor on a high-wheel cycle, an operation

described as “peddling his wares.”

When

Ford arrives at the actual printing of The New Yorker, he is forced to

describe the gigantic electrical printing press (“named Bertha”) which,

“according to legend,” consists of only 24,927 pieces, “over half of which were

cotter pins.” When the editors ran out of spare parts, they advertised for more

and received a goodly quantity, including “a piston ring, three fly-wheels, and

a rare gasket, or female gadget.”

But

Our Narrator found the printing operation itself “too long and difficult to

describe here, where it may help the reader to form some conception of this

important step in the Making of a Magazine.” Wait—what? So Our Narrator, after

asserting that a description of the printing operation may help the reader

understand “this important step” (a circular statement in itself), he refrains

from offering the description. The height of nonsense—at which, as we all now

acknowledge, Corey Ford was proving marvelously adept.

The

magazine and its staff and printing plant were housed in a 74-floor structure

occupying eight city blocks, and each department was put into a separate room

of its own, each named “Private” —“after the father of Our Mr. Tilley, a

private in the Civil War.” The departments were connected by an intricate

network of pneumatic tubes through which pieces of the magazine are conveyed

elsewhere until they emerge as a whole issue of The New Yorker.

Later,

in order to provide housing for the magazine’s millions of staff members, Our

Mr. Eustace Tilley purchased Manhattan Island in 1893, “ingeniously” evolving

the name of the place from the name of the magazine—New York.

Bull

provided illustrations showing a movie critic at work and Our Mr. Eustace

Tilley christening the island “New York” in the presence of a couple local

citizens (whose names no longer signify much to us) and such historic

personages as Christopher Columbus, Napoleon, Pope Gregory VII, Edgar Poe,

George Washington, Caesar and Lief Erickson.

The

last of Ford’s chapters is devoted to a description (with illustrations) of

“the original New Yorker building, destroyed by fire in 1868" (pictured is Grant’s Tomb), the interior of the present headquarters where

contributors wait to see the editor (depicted is the inside of Grand Central

Station), the printing press Bertha, and the present New Yorker buildings,

where the staff meets every day in weekly meetings.

And

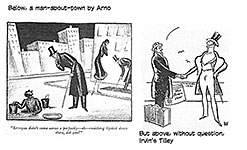

so we conclude the True History of Our Mr. Eustace Tilley, who, by proclamation

in lieu of any substantial evidence, is the same person as Rea Irvin depicted

on the cover of the first issue of The New Yorker. As noted in the array

of Bull’s Talk of the Town spot drawings, Our Mr. Eustace Tilley—that is, Johan

Bull’s Tilley—may have appeared at least once outside of the Ford narrative.

And he also may be discerned, perhaps, in the accompanying cartoon by Peter

Arno: the top hat is maybe a clue, but the defining monocle is altogether

missing. Probably not Our Mr. Eustace Tilley at all.

Irvin’s

Tilley also appeared at least once beyond the cover or any of the department

headings Irvin designed. He appears next to the aforeposted Arno cartoon in his

customary Irvin garb, welcoming a visitor to New York, the British actor

Michael Arlen. Don’t know who drew the picture, but the signature seems to be a

dingbat of that irrepressible owl. Perhaps in recognition of his persistence,

we ought to give him (it) a name. How about Comte d’Orsay?

EUSTACE TILLEY,

as it turns out, is not the only fabricated personage lurking the editorial

offices and the pages of The New Yorker. For almost forty of its

ninety-year existence, Owen Ketherry has been writing to some readers in

response to their letters. Not all readers who write the magazine get a letter

in response: only those who write to point out an error. The magazine has been,

since the beginning, paranoid about making mistakes in print. And when an alert

reader catches an error and writes about it, Owen Ketherry dutifully responds.

But

Owen Ketherry, like Eustace Tilley, is not a real person. The name is an

anagram of “The New Yorker” and represents a collective response, Rachel Taylor

tells us in the April 1999 issue of Brill’s Content (now sadly defunct).

“Reader correspondence is routed through the letters editor, the fact-checking department

and occasionally the writer and editor of the story [at issue]—all before it

reaches ‘Ketherry’s’ desk,” explains deputy editor Pamel McCarthy. ... Because

‘so many people are involved’ in responding to reader corrections, ‘it does

seem appropriate that the response come from the magazine rather than one

person.’”

Owen

Ketherry has been signing response letters since at least 1975 or so.

Taylor

asked editor David Remnick whether it was appropriate for a magazine of The

New Yorker’s standing and reputation to lie to its readers.

“I

don’t think it’s a lie,” he said, “—it’s an institutional rubric,” adding that

the Owen Ketherry tradition is “harmless. The key thing,” he continued, “is

that letters are answered institutionally. The  editor of the magazine cannot

personally answer hundreds and hundreds of letters” (from know-it-all readers

who’ve made a spare-time vocation of pouncing on imagined—or real—errors). editor of the magazine cannot

personally answer hundreds and hundreds of letters” (from know-it-all readers

who’ve made a spare-time vocation of pouncing on imagined—or real—errors).

The Brill Content report is illustrated with a picture of the imaginary Owen

Ketherry.Ingeniously fashioned by Rollin McGrail, Owen Ketherry looks remarkably

like Bull’s Tilley might look if he’d survived his short life in 1925 to

displace Irvin’s Tilley.

BUT IRVIN’S

TILLEY keeps reappearing, as we said at the beginning of this disquisition,

every year on the cover of the magazine’s issue for the last week of February.

Until, that is, 1994, when Crumb’s Elvis Tilley took the place of honor.

After

that—the habit having been broken, shattered—other “Tilleys” surfaced on the

covers of succeeding anniversary issues. Eustace Tilley returned in 1995 to

soothe the feelings of rampant traditionalists (like moi), but the year after,

we had “Eustacia Tilley”—a feminine image at long last"—then Art Spiegelman produced a rendering of Chester Gould’s cleaver-jawed detective, “Dick Tilley.”

Eustace

Tilley was back again for a couple years, then William Wegman dressed

one of his dogs in dandy duds and called it “Putting on the Dog.” Eustace

Tilley returned until 2008, a presidential election year, when two Tilleys

adorned the cover, one upside down, together creating the impression of a face

card. One looked like Hillary Clinton; the other, Barack Obama. The title:

Eustace Tillarobama. One year, the butterfly was featured in a six-panel cover

comic strip.

The

covers from 2012 through last year have been “takes” on Tilley—a blurred image

like that on the computer screen as your computer is loading, a “Brooklyn

Tilley” (an somewhat artsy dude in his apartment, and through the window, in

just the right juxtaposition to the man’s raised right hand, we see a panel

truck out in the street with a butterfly painted on the back door), and last

year, “Night Windows,” a silhouette of Tilley formed by lighted windows of

buildings in the New York night.

For

a few years, readers were invited to participate in annual Eustace Tilley

contests, contributing comic-strip Tilleys, dog Tilleys, tattooed Tilleys,

emoji Tilleys, and twerking Tilleys.

But in 2015, the anniversary Tilley

had to be different, as art director Mouly remembers. She was asked by editor

Remnick months in advance to come up a way to celebrate the magazine’s 90th birthday.

She

turned, as she does every week, “to our artists for ideas, and this time we

decided to publish more than one. We picked nine covers for our ninety

years”—one for each decade—“selecting images that reflect the talent and

diversity of our contributors and the range of artistic media they use: oil

painting for Kadir Nelson and Anita Kunz; pen and ink with watercolor for Roz

Chast, Barry Blitt, and Istvan Banyai; oil pastel for Lorenzo Mattotti; collage

for Peter Mendelsund; and digital art for Christoph Niemann. Some of these

artists are regulars—this is Barry Blitt’s eighty-eighth New Yorker cover and Lorenzo Mattotti’s thirtieth.

Others are newcomers. Each brings Eustace Tilley squarely into the twenty-first

century, and proves that art is as alive on the cover of the magazine today as

it was in 1925.”

And

here they are, all nine of the covers, one of which, Blitt’s, consists of nine

separate images.

Blitt explains: “I thought it would be amusing to

present Eustace Tilley in the various styles that have come and gone over the

past ninety years. So I showed the inveterate dandy coming unstuck in time,

appearing as greaser, hipster, hippie, yuppie and punk, among others.”

So

does that make 97 covers for Blitt?

His

Eustace Tilleys look pretty good, but his fragile sometimes wavering penline

bespeaks a kind of tentativeness, and in more complex compositions, that lack

of confidence is a distinct blemish—in my so-called mind, anyhow. But then,

Blitt’s rich and famous, and I’m just a harmless drudge, laboring enviously in

the digital backwaters.

The

anniversary issue prints all nine of the covers, including Blitt’s nine-Tilley

cover: three as actual covers, one after the other at the front of the

magazine; then all nine, in miniature on the table of contents page.

Behind

the opening trio of covers, the magazine does little to celebrate the occasion:

nine one-page essays, called “snaps” (for “snapshots,” I assume), each focusing

on some minutiae of each decade; and an article by Ian Frazier about Ellin

Mackay, a New York heiress who in November of 1925 revitalized the magazine

with a tart piece entitled “Why We go to Cabarets: A Post-Debutante Explains.”

After

committing this attack on high society, she committed another: herself the

debutante daughter of a wealthy family, she defied her Catholic father and, as

Ford put it, “eloped with a [Jewish] former Bowery saloon piano player named

Izzy Baline, who had changed his name to Irving Berlin” while becoming the most

famous song-writer in the world. Ellin’s father never spoke to her again. Her

marriage to Berlin, however, was a loving and lasting one.

Months

before their marriage (and before the article in The New Yorker), newspaper

gossip about the couple was rampant, so when Mackay’s article appeared, her

name and the debunking attitude of the piece created a mild sensation (that

Ross’s wife, Jane Grant, who worked at the New York Times, was astute to

exploit, making sure newspaper reporters knew of the article before it actually

appeared).

Rumors

of the couple’s supposed engagement swirled for weeks before their January 4,

1926 wedding, and news of the impending marriage surfaced a few hours before

(or immediately after) the fact, and ravenous reporters pursued the newly weds

until they found refuge in Ross’s house on 47th Street, where they

stayed until their ship sailed for a honeymoon cruise to Europe.

That’s

the story told by Margaret Chase Harriman in her 1951 account of life around

the lunch table at the Algonquin Hotel, The Vicious Circle. The refuge

at Ross’s emphasized Ross’s role in the event, which suited Harriman’s purpose.

But there are other versions of the nuptials.

According

to Frazier, the wedding took place at the Municipal Building with only Berlin’s

business manager and wife present. And right after the ceremony, the fresh

bride phoned Ross to say she wouldn’t get her new article in on time because

she was leaving town in twenty minutes. They apparently did not take refuge at

Ross’s.

Other

versions of the romance’s climactic moments suggest that the newly weds did not

leave town immediately. And the article Mackay was late in submitting

apparently never showed up: she did only one article after the Cabaret piece,

and it was published before her marriage.

But

there were other ramifications.

James

Thurber, then in

France, read about the sensation of Mackay’s article in the Paris edition of

the New York Herald and decided that The New Yorker sounded like

the kind of magazine he would like to write for. After the magazine had

published a few of his short pieces, Thurber joined the staff in 1927.

Frazier

sprinkles New Yorker history along the way as he traces Mackay’s story.

Nicely informative. But it’s Eustace Tilley who is the icon of the magazine’s

ninety years.

“WE ARE

ENCOURAGED TO GO ON”

BUT EUSTACE

TILLEY was not Harold Ross. Eustace Tilley, Ford said (and he would know) would

have cut Ross dead had the two ever chanced to meet. For all his presumed

empty-headedness, Tilley was a fashion plate, a model of male attire in the

1830s. His wardrobe may have been seriously out-of-style in New York’s roaring

twenties, but he nonetheless radiated a sense of style wherever he turned up.

Ross emphatically did not.

More

of a character than either Tilley or Ketherry, Ross famously had no sense of

style. “His clothes never quite fit,” Ford said. “He favored dark suits and

ties, a subsconscious instinct for camouflage. He had a passionate desire to be

anonymous and devised elaborate schemes to enter or leave his office without

being seen. He walked slouched forward” and his hair was forever mussed.

And

it is Ross, not Tilley, who made The New Yorker what it was, a brilliant

exemplar of journalistic integrity and urbanity.

Kunkel’s

biography of Ross is doubtless the most authoritative, but Thurber’s is the

most personal and insightful. And colorful.

Thurber

begins by remembering a party held to entertain the editors of Britain’s Punch a year after Ross’s death. Thurber missed the party but weeks later had

lunch with Punch cartoonist Rowland Emett.

“I’m

sorry you didn’t get to meet Ross,” Thurber said upon sitting down at the

table.

“Oh,

but I did,” said Emett, referring to the party. “He was all over the place.

Nobody talked about anybody else.”

And

Ross, a bundle of eccentricities and a storehouse of anecdotal oddities for

others, was a rich source of conversational matter. Nobody called him anything

but “Ross,” for example, and that bothered him. Even though he didn’t like his

first name, Harriman attests, “and winces if anybody does address

him by it.”

“I

like my last name,” he admitted. “My grouse is that in my office I am almost

totally surrounded by people who call me Mr. Ross. This makes a

man feel old.”

Thurber

recalls his first meeting with Ross, “this exhilarating and exasperating man,”

at The New Yorker office. When Thurber told him that he wanted to write,

Ross launched into a tirade about writers and editors and the state of American

civilization generally:

“Writers

are a dime a dozen, Thurber. What I want is an editor. I can’t find editors.

Nobody grows up. Do you know English? Everybody thinks he knows English, but

nobody does. I think it’s because of the goddam women schooteachers. [He turned

away from the window through which he had been staring and glared at Thurber as

if he were on the witness stand and Ross was the prosecuting attorney.]

“I

want to make a business office out of this place,” Ross continued, “—like any

business office. I’m surrounded by women and children. We have no manpower or

ingenuity. I never know where anybody is, and I can’t find out. Nobody ever tells

me anything. They sit out there at their desks, getting me deeper and deeper

into God knows what. Nobody has any self-discipline, nobody gets anything done.

Nobody knows how to delegate anything.

“What

I need,” he plunged onward, “is a man who can sit at a central desk and make

this place operate like a business office, keep track of things, find out where

people are. I am, by God, gong to keep sex out of this office. Sex is an

incident. You’ve got to hold the artists’ hands,” Ross went on, skidding off

into another of his convictions, “—artists never go anywhere. They don’t know

anybody. They’re antisocial.”

If

Ross didn’t know what was going on, it may well have been his own fault. Ford

tells of a Ross eruption during a noisy re-modeling project transpiring in the

offices. Annoyed by the racket, Ross yelled at his secretary, “Go find out what

the hell is going on, but don’t tell me.”

Thurber

reports that “one of the minor problems that grew into a quandary as I went

along [writing The Years with Ross] was Ross’s virtual inability to talk

without a continuous flow of profanity. As in the case of many other Americans,

it formed the skeleton of his speech, the very foundation of his manner and

matter, and to cut it out would leave him unrecognizable to his intimates or

even to those who knew him casually. I intensely believe that Ross was never

actually conscious of his profanity, or of the nature of blasphemy itself. He

was merely using sounds that make communication possible for him, and without

which he would have been almost tongue-tied. Ross’s ‘goddam’ referred to a god

that had nothing to do with the Diety, and his ‘Geezus,’ as I have spelled it,

belongs in the same category.”

According

to Ford, “Ross had a paternal attitude toward his staff, but Thurber was an

object of his special solicitude since Ross had convinced himself that Thurber

was impractical and helpless.” Thurber took advantage of this misconception by

playing pranks on his editor. The ultimate prank, you might say, was the book

he wrote about Ross.

Frazier

says he was surprised when he learned that many people at The New Yorker didn’t

like Thurber’s book: “Robert Bingham, then the executive editor, told me that

the book made Ross look like a buffoon when he was in fact a brilliant and sensitive

editor, the greatest of his day.”

That’s

too bad if Thurber’s book lends itself to this misinterpretation. The book was,

in fact, a labor of love—Thurber’s love for Ross. The penultimate paragraph in

the book is this:

“A

hundred editorials, after his death, acclaimed the genius of the Colorado

urchin who had reached the High Place the hard way. The back files of the

magazine in his years shine with triumphs that time cannot darken. Scores of

admiring, and envious, editors attested to his brilliant command of a staff of

wartime writers whose coverage of all theaters of the conflict forms one of the

outstanding accomplishments of American journalism, good writing, and excellent

editing. Many eulogies of him ended with the identical words: ‘He was a great

editor.’ He made, as I have said, a lot of friends and lost a few; he made the

right enemies and kept them all. Some of the things he touched were smudged,

but most of them were stained with a special and lasting light, as hard to

describe as the light in a painting.”

Thurber

concludes his book by quoting a sentence from the Advance of Lynchburg,

Virginia. It had been framed and hung on the wall of Ross’s office; he was that

proud of it. “It is a supposedly ‘funny’ magazine doing one of the most

intelligent, honest, public-spirited jobs, a service to civilization, that has

ever been rendered by any one publication.”

Clearly,

Thurber agreed with that assessment.

But

that didn’t prevent him from appreciating Ross’s peculiarities. Ditto Harriman,

who writes: “A great deal has been said and written about Ross’s naivete, and

this is a delusion that he does nothing to correct, being a man who often looks

puzzled and has a habit of rubbing his hand over his face in a gesture of

seeming bewilderment. Actually, he is about as naive and bewildered as

Machiavelli, Winston Churchill, Gypsy Rose Lee or the President of Standard

Oil.”

|

|

She

goes on to describe some of what made Ross a great editor: “Perhaps his truest

quality is a sort of tired but unconquerable enthusiasm. After twenty-five

years of editing The New Yorker, his viewpoint still is always fresh and

unfailingly interested. He reads every word of every piece that goes into the

magazine and, in most cases, makes careful [meticulous] marginal notes to the

author [asking for clarification or suggesting other avenues to pursue—before

the article is published]. Ross’s marginal queries—treasured by all who have

received them—are a wonderful combination of his own wish to ‘assume a

reasonable degree of enlightenment’ on the part of New Yorker readers,

and the general belief of editors everywhere that the reading public don’t know

from nothing.

“He

is the most helpful editor in the world,” Harriman says, without qualification.

Ford describes Ross’s approach to a manuscript as akin to that of a field

marshal attacking an opposing army. Another victim of the editor’s scrutiny

said Ross “regarded every sentence as the enemy, and believed that if a man

watched closely enough, he would discover the vulnerable spot, the essential

weakness. He devoted his life to making the weak strong.”

Said

Harriman: “He has an ear for an effective story just as he has an eye for the

right or wrong word.” And he trains his “searchlight gaze” with equal

determination upon the cartoons for the magazine—with the result that American

gag cartooning was thoroughly revitalized (a story told in the aforementioned Harv’s

Hindsight on gag cartoons and The New Yorker.)

Time magazine, against whose

editor/founder Henry Luce Ross was often poised, wrote a respectful article

when Ross died. Ross’s so-called feud with Time/Life was based largely upon his

disapproval of the Luce kind of journalism. Ross once wrote in a note to E.B.

White: “Life does a story on the placid and historic Thames and

finds nude sunbathers on its banks. This must be the fifty-eighth way of

working in naked women.”

Still,

when Ross died, Time was laudatory:

“Harold

Ross once defiantly accepted the description of his magazine as an ‘adult comic

book.’ This was a less-than-just verdict on the magazine that caused or charted

wide changes in American humor, fiction and reporting, but it was quite in

keeping with the arrogant character of Editor Ross to accept it. ... Rumpled,

wild-haired and irascible, Ross talked in an ear-splitting voice, a combination

of rasp and quack. He often expressed himself in skid-row profanity or by

grunts or gap-toothed grins. He had the energy of a bull, and a bull-like

charm. Though he often sounded as crass as a cymbal, he had an amazing

sensitivity for words, a pouncing eye for the phony, a rigorous taste. He was a

great editor. ...

“His

fiercest prejudice was against writing that was not crystal clear. ... Ross

insisted on knowing everything about the subject and the people [of every

article], right down to their blood pressure. On the margins of manuscripts he

scrawled scores of choleric questions and comments: ‘Who he?’ ‘What’s that?’

‘Don’t think.’ ... Though his profanity was as natural and unconscious as his

breathing, he was puritanical about the printed word. He even barred such words

as ‘armpit’ and ‘pratfall.’” Speculating about the future of The New Yorker

without its founder, Time finished: “No one can take Ross’s place [with his]

snarling, unappeasable appetite for excellence.”

Kunkel

cites two of Ross’s most “notorious queries” in the margins of manuscripts,

demonstrating his “quest for absolute clarity”:

“Two

characters were chatting beside a fireplace, Emily Hahn wrote. ‘Which side of

the fireplace?’ Ross queried. In his account of John F. Kennedy’s PT-109 wreck

in the South Pacific, John Hersey reported that Kennedy ‘wrote a message’ on a

coconut to some native islanders. ‘With what, for God’s sake?’ Ross demanded.”

Careful

and exacting as Ross was, he seldom offered a writer or cartoonist overt praise

in any detailed or formal way. In a famous instance, he went to compliment

White, Thurber’s cohort in establishing (more than any other two people) the

literate cosmopolitan tone of the magazine. White enjoyed a peculiar

distinction among the magazine’s writers: Ross almost never tinkered with

White’s prose, such was his estimation of its merit, but he almost never

complimented White either. On this occasion, however, Ross was moved to

comment. Finding White away from his desk, Ross left a note expressing his

pleasure about White’s latest exposition: “I am encouraged to go on.”

Painfully

shy, White was comfortable only when alone and writing. He picked up his

nickname, Andy, at Cornell (“students named White,” said Kunkel, “tended to be

dubbed Andy after the university’s first president, Andrew D. White”) where he

edited the campus newspaper. After college, White held a couple of “tedious

jobs” and submitted light verse and an occasional prose piece to The New

Yorker. Ross recognized “a fresh voice and clarity of style” and invited

White to join the staff, which, after a trial period, White did in early 1927.

In

White, Ross found “a seemingly effortless producer of crystalline prose that

was at once unforced, bemused, ironic,” said Kunkel, who continued, quoting

Marc Connelly: “White brought the steel and music to the magazine.”

He

also brought Thurber. Soon after joining the staff, White met Thurber at a

party, and, upon learning that Thurber aspired to being a writer—and had

contributed short articles to the magazine— White encouraged him to visit the

office. Whereupon, Ross, who “had somehow got it into his head that Thurber and

White had been bosom pals for years,” hired Thurber on the spot. He also

assigned the two of them to the same office, thereby creating the forcing bed

for The New Yorker’s distinctive tone and manner.

Said

Kunkel: “If White provided the steel and music, Thurber contributed the right

amount of phosphate and mischief. They spurred each other on, wrote to please

each other, and soon came to form a kind of double helix at the core of The

New Yorker. As Brendan Gill said, at some point Ross realized that ‘though

the magazine was his, the persona of the magazine must be White-Thurber.’”

We

already know, thanks to Thurber’s recitation of a Ross diatribe, that Ross had

an aversion to sex. But that was only in regard to the magazine. He diligently kept

any sexy stuff out of The New Yorker. But he was scarcely a puritan in

life. Married three times and divorced twice, Ross apparently had a somewhat

free-wheeling sex life between wives. And many of his paramours were celebrated

Broadway stars or eager starlets. Nor was Ross very bashful about matters of

sex.

Once

one of his editors was in conference with him and noticed that Ross was

fidgeting uncomfortably in his chair. After a while, relates Kunkel, whose

story this is, the visitor asked Ross what was wrong.

“They

ought to have covers, wooden or metal covers of some kind, around the goddamn

radiators,” Ross blurted.

Confused,

the visitor said: “What radiators? Here—in the office?”

“Good

God, no,” Ross said. “At the Ritz. I had this dame in bed and it got cold so I

got up and walked over to the window to shut it. I had to lean over to shut the

window, and my you-know-what dangled down on this red-hot radiator. Feels like

a second-degree burn, for Christ’s sake. Now about this article you brought in

here ...”

As The New Yorker matured, the names of its writers appeared less and less

frequently in its pages. (Bylines have re-appeared in recent years.) Ross

insisted that the magazine was a collective project, no one more important (or

deserving of public recognition) than anyone else. Ross’s name never appeared

in the magazine until after he was dead: “H.W. Ross” headlined the obit on the

first page of the issue for December 15, 1951.

Despite

his fanatical quest for anonymity, Ross was a celebrity—an authentic personage,

known for what he was and did rather than for simply being famous, today’s only

celebrity laurel. When he died on December 6, the news spread around the world

on the front pages of newspapers.

“More-or-less

by common consent” among the staff, Kunkel said, the task of writing Ross’s

obituary for the magazine fell to White. “A more difficult thing had never been

asked of him. He was still in shock himself ... and there was little time.

Ornery to the very end, Ross died just as they next issue of The New Yorker was

about to close.”

White

began by referring to the situation—deadline looming—which “was known, in these

offices that Ross was so fond of, as a jam.” And while Ross “always knew when

we were in a jam and usually got on the phone to offer advice and comfort and

support,” he wasn’t around to do that anymore.

As

White worked on the obit, people drifted in and out of his office, “offering

help and solace, if not seeking the same,” Kunkel said. “Suddenly, from down

the corridor near the bank of elevators, rose a primal wailing: ‘Andy An-dy’ ... A staffer who was there remembers

the sound as almost spectral, one of pain, yet tinged with fear. She ran into

the hall and there found Thurber moving slowly down the corridor, hands to the

wall, groping his way from doorway to doorway. ‘Andy’

he called again. By now almost fully blind, Thurber seldom ventured to the

magazine, and on such occasions he was never without his wife or someone else

to lead him. But now, robbed of his friend and mentor, Thurber had never seemed

so vulnerable, so utterly alone. Instinctively he was drawn back to The New

Yorker, as was White, as were all the rest, like children drawn to their father’s

grave.”

White’s

obituary was scarcely standard fare for the genre. It didn’t cite Ross’s

birthdate or birthplace nor, indeed, did it scroll through his professional

life before The New Yorker. In fact, we had to read it carefully to know

that the name in the headline, “H.W. Ross,” belonged to the man who had founded

the magazine. It was as if the obit assumed that everyone reading it already

knew who Ross was and what he had done in order to be entitled to an obit on

the first page of that issue of The New Yorker. In that, White was

probably right: Ross was, as we’ve already observed, well-known, a genuine

celebrity.

What

White wrote that day after Ross’s death was not an obituary: it was, as White

himself  admitted, a love letter. We’ve posted the whole thing here; and if you

can’t read the tiny type or enlarge it enough, print it out: the image is clear

enough to read in hardcopy. admitted, a love letter. We’ve posted the whole thing here; and if you

can’t read the tiny type or enlarge it enough, print it out: the image is clear

enough to read in hardcopy.

White

wrote mostly about Ross’s relationship to his magazine, to the kind of

journalism it fostered, and to those who helped produce it. “It took a little

while to get on to the fact that Ross, more violently than almost anybody, was

proceeding in a good direction, and carrying others along with him, under torrential

conditions. He was like a boat being driven at the mercy of some internal

squall, a disturbance he himself only half understood and of which he was at

times suspicious.

“His

dream,” White continues, “was a simple dream; it was pure and had no frills: he

wanted the magazine to be good, to be funny, and to be fair.”

White

ends by invoking Ross’s habitual remark upon parting with a staff member after

a conversation or meeting (“calm or stormy”): “He would wave his hand,

gesturing you away. ‘All right,’ he would say. ‘God bless you.’”

White

elaborated in a generous and heartfelt farewell to his boss:

“Ross

usually took God’s name in vain if he took it at all. But when he sent you away

with this benediction, which he uttered briskly and affectionately, and in

which he and God seemed all scrambled together, it carried a warmth and

sincerity that never failed to carry over. The words are so familiar to his

helpers and friends here that they provide the only possible way to conclude

this hasty notice and to take our leave. We cannot convey his manner. But with

much love in our heart, we say, for everybody, ‘All right, Ross. God bless

you!’”

Authentic

enough but not entirely accurate. Probably, White was habitually obeying Ross’s

own dictum that no profanity should sully the pages of The New Yorker.

Here at Rancid Raves, however, we harbor no such scruples. To faithfully

represent Ross’s usual parting expression, White’s concluding line should have

read: “All right. God bless you, goddamit.” That blend of blasphemy and

emotion, as Corey Ford said, was Harold Ross.

AND NOW, here’s

a selection of Johan Bull’s work for The New Yorker during the

two years his cartoons appeared therein—:

Return to Harv's Hindsights |