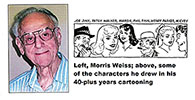

Morris

Weiss, Mickey Finn and the Palooka

A Visit with

One of the Most Durable of the Laborers in Cartooning’s Vineyards

ONE DAY IN

1934, the faux “radio announcer” in Ed Wheelan's Minute Movies comic strip made a cryptic request: "If Morris Weiss is listening,"

he said, "let him get in touch with Ed Wheelan."

Weiss

missed seeing the strip, but a friend told him about it, and when he phoned

Wheelan, the veteran cartoonist asked the 19-year-old freshly graduated High

School of Commerce student if he'd like to do the lettering on Minute

Movies. That was the beginning of Weiss's 42-year career as a cartoonist.

At

the time, Weiss was trying to decide between cartooning and illustrating as a

career. New York's High School of Commerce was conveniently located in midtown

Manhattan (where Lincoln Center is now), and Weiss took advantage of the

convenience to call upon as many illustrators and cartoonists as he

could—asking advice, showing his work, collecting original drawings.

"I

met Charles Dana Gibson," Weiss recalled when we talked in October

1992, "and James Montgomery Flagg and all the famous comic strip

artists— Edwina Dumm, the dearest, sweetest person, who was very nice to

me, who was then doing the Sinbad page [about a mischievous little dog] for the

old Life magazine and her comic strip, Tippie and Cap Stubbs.

Gibson, a kindly gentleman, said to me, I was like you once, young and

ambitious. Flagg wouldn't let me leave his apartment after drawing me until an

old friend arrived, William S. Hart.

"Among

the giants I have been privileged to meet," he continued, "were Harvey

Dunn, a great painter among illustrators and a powerful presence of a man,

who told me that you had to feel a painting in order to paint

it. And Billy DeBeck, who told me he learned how to draw with a pen by

copying Gibson's illustrations, line-for-line. And when he was broke, he sold

them for five dollars each in bars in Chicago—as Gibson originals!"

But

Weiss's cartooning career was not destined to take flight from the launching

pad of Wheelan's strip. "I tried hard," Weiss said, "but I

couldn't master the 170 Gillot point for lettering. After a week, he let me

go, and I understood why."

A

few weeks later, Weiss heard that Pedro "Pete" Llanuza was

looking for an assistant on Joe Jinks. Having found a penpoint more

congenial to his hand, Weiss became Llanuza's assistant, doing the lettering,

inking the backgrounds, cleaning up the art, and delivering the strips to the

syndicate office. "He paid me six dollars a week," Weiss said.

"And after four months, he gave me a raise to seven dollars a week."

Seeking

to increase his income, Weiss applied to Harold Knerr to do the

lettering on The Katzenjammer Kids. Later, he joined the Max Fleischer

Studios as an opaquer, his first full-time job, leaving Joe Jinks but

continuing to letter for Knerr in his spare time.

Weiss's

big break came in the spring of 1936—partly as a result of a Christmas card he

produced the previous year. Designed as a promotional piece as well as a

seasonal greeting, the card showed young Weiss at his drawingboard and, pinned

to the wall behind him, his copies of the original drawings he'd received from

cartoonists and illustrators.

He

couldn't afford to have the card printed, but his mother, who (until then)

hadn't held much hope for his career as an artist, saw "something" in

the card (as Weiss said), and she dipped into scant family savings for it to be

printed. Weiss sent it around to all the cartoonists and illustrators he'd

met, including Lank Leonard, then sports cartoonist for the New York

Sun and the George Matthew Adams Syndicate.

Leonard

had just started Mickey Finn, a strip about a kindly young work-a-day

policeman and his Irish family, and he was looking for an assistant. Seeing

among the pictures behind Weiss a rendition of Edwina Dumm's Tippie, Leonard

phoned Edwina and asked whether she knew anything about Weiss.

"Of

course, she put in some nice words for me," Weiss said. And Leonard sent

Weiss a wire, asking him to come to visit him at his Port Chester studio.

Leonard

picked the youth up at the train station. "And when we drove up to his

house and got out of the car," Weiss said, "a bunch of kids were

playing in the street, and they greeted him, Hello, Lank—Hello, Lank—Hello,

Lank. And I thought, This must be a nice man if the kids are calling him by

his first name."

And

the first time Weiss called him "Mister Leonard," Leonard corrected

him: "Not Mister Leonard—Lank." Leonard watched Weiss ink some

backgrounds for about ten minutes and then hired him. Leonard was twenty years

older than Weiss; it was the beginning of a lifelong friendship. "He was

both a big brother and a father to me," Weiss said.

Mickey

Finn, which had started April 6, 1936, was only a few weeks old at the

time. "Leonard got the idea from an Irish cop in Port Chester,"

Weiss told me. "Named Mickey Brennan, he was wonderful with kids. He

directed traffic after school, and there were always a bunch of kids around

him. That was the inspiration for Mickey Finn."

Weiss

stayed in Port Chester for half the week, working with Leonard; then he went

home to the Bronx for the other half of the week. At first, he inked

everything in the strip except the faces and hands of the characters, which

Leonard did. One day several months later, that changed.

Leonard

was an avid golfer, and he often left Weiss in the studio to ink the strips

while he played a few holes of golf. On one such occasion, Weiss had finished

all he was allowed to ink and contemplated a wait of two or three hours before

Leonard would return to finish the strips. And since Weiss would then deliver

the strips to the syndicate office in Manhattan, he knew he would have to wait

for Leonard to do his inking. Altogether, he was facing three or four hours of

enforced idleness.

"By

then I was pretty confident of my inking," Weiss said, "so I went

ahead and inked the faces and hands. Lank came in two-and-a-half hours later.

I heard him come in and take a shower. And then he came into the studio and

sat down at the drawingboard and said, ‘Okay—give me the strips.’ And I gave

him the strips, and he looked at them and said, ‘You son-of-a-gun: you inked

the faces and the hands!’ From that day on, he never inked a line on the

strips."

After

he'd been with Leonard for about six years, United Features Syndicate hired him

to draw Joe Jinks, the strip he'd left years ago. The assignment filled

out the week: continuing to do Mickey Finn for three-and-a-half days a

week in Port Chester, he did Joe Jinks in the remaining half-week at

home in the Bronx. This routine continued until he was drafted into the Army

in 1944.

When

he was released from active duty in 1945, Weiss didn't return to either of the

strips he'd been working on. Instead, he began writing and drawing teenage

comic book stories for Stan Lee at Timely Comics. He worked on Tessie

the Typist, Margie, Patsy Walker, and Miss America as well as

some love and funny animal books for other publishers. He also assisted Al

Smith on Mutt and Jeff occasionally. And in 1948, he joined the

infant National Cartoonists Society, in which he remained an active member for

years until he moved to Florida.

During

this period, Weiss had a strange encounter by phone with the creators of

Superman, Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel:

"Shuster,

who was the artist, called me up one day and asked me if I would write a comic

strip that he would draw. And I told him I wasn't interested. And strangely

enough, about a week or so later, Siegel called me up and said he wanted to

write a comic strip if I would draw it. But I told him I didn't have time to

do it either."

This

was right about the time that Shuster and Siegel’s 10-year contract with DC

Comics was on the cusp of expiring, leaving the two unemployed after a decade

doing Superman. Shuster and Siegel would soon produce Funnyman, a

short-lived comic book that debuted with a cover date of January 1948, but

before they settled on Funnyman, they apparently each thought again of pursuing

independent careers. (For the story of Funnyman, see Hindsight for

November 2006.)

In

1960, Weiss rejoined Leonard, then ensconced in Florida. "He was then

living in Miami Shores," Weiss said, "and he wanted to know if I

would join him again with the idea of eventually taking over the strip. So

that's what brought us to Florida. On the drawing, we did the same as before:

Lank would pencil the drawings (unless he was sick and then I would do the

pencils, too—and I always pencilled the girls because Lank couldn't draw a

pretty girl), and I would ink."

Weiss

worked on the stories, too: "We would talk over the storyline, and he

would be the final word on the story. And then he would pencil in the strips,

doing the writing and the drawing, and I would look over it, and if I didn't

like something, we would talk it over."

Then

in 1968, Leonard had a heart attack. Weiss recalled: "When he got out of

the hospital, he said, ‘I'm through with the strip; I want you to do everything

now, the writing and the drawing.’ And I said, ‘I'll do it on one condition:

that you don't see the strip at all until it comes out in the paper because if

I'm going to write it, I'm going to do it my way, and my storyline may be a

little more daring than you would do.’ And he said, ‘That's fine.’

"I

did that for the next two years or so until he died. In that two years, when I

would see him, he would say, ‘Hey, I liked what happened today—what's going to

happen tomorrow?’

"I

told him at the time, if you're unhappy with the story that I'm writing, then

we'll cease. But he was very pleased, and the strip held his interest, which

to me was a great compliment. And in those two years, he didn't want the

syndicate to know that he wasn't doing it any longer, so his signature stayed

on the strip. When he died (August 2, 1970), I carried on for another seven

years."

Before

Leonard died, Weiss took on yet another comic strip chore: "After I'd

been with Lank for a year or so, Charlie McAdam [of McNaught Syndicate] called

me up and asked me to lunch. And he said, ‘I'll pay you more money than Lank

is paying you if you'll do the Joe Palooka strip, the writing and the

drawing.’ And I said, ‘No, I won't leave Lank; it's a matter of

loyalty.’"

But

later, Weiss had another idea: he offered to write the continuity for Joe

Palooka, and McAdam took him up on it. Tony DiPreta continued to

draw the strip, and Weiss wrote it. But he didn't want his name on the strip:

"It

already had the signature stamp of Ham Fisher as well as DiPreta's name,

and three names would clutter up the strip. I told them that as long as my

name was on the checks that I got every week, I'd be quite happy."

For

the next several years, Weiss wrote Joe Palooka and wrote and drew Mickey

Finn.

How

did he do the writing for someone else, I wanted to know: "What did you

give the artist? Rough drawings?"

"No,

no," he said. "Just the story. If I introduced a new character, I

would tell him what the new character would look like, but I don't remember

ever giving him any drawings because I think Tony would have been offended at

that: when he saw the character described, he would realize how the character

should look."

"So

you gave him a script, like a movie script?" I asked.

"No,

not like that. I would put it into boxes, panels like a strip, and I would put

the balloons in, and I would have the tail come from Joe or Ann or Jerry."

I

said: "So in effect, you were writing just as you probably wrote your own

strip: you wrote the speech balloons out, right into the strip's panels."

"Yes,"

he said.

I

continued: "So if you're doing a week's Mickey Finn strips, say,

you first did breakdowns—breaking the story into panels—day-by-day, but you had

no written version of the story that you were working from except what was in

your head?"

"Yes,

the story was always in my head because that way you have flexibility," he

said. "A lot of times I would change the story as I went along."

I

remembered something Milton Caniff had told me: "Milton used to

say that if he got a letter from a reader that indicated the reader had figured

out what was going to happen next, he would change the ending."

Weiss

laughed. "Sometimes I would try to do that, too," he said, "—to

get a twist. I tried to fool myself. And I did that one time with one of the

Joe Palooka fights. It looked like he was going to win, but I had him lose

it."

"Joe

Palooka lost a fight?" I asked, incredulous.

"Yes,

I had him lose twice."

In Mickey

Finn, Mickey's Uncle Phil almost took over the strip, even while Leonard

was producing it. Phil was a genial but somewhat fatuous character, whose

harmless boasting made him the perfect fall guy, and as such, he provided comic

relief in the stories. Eventually, the Sunday strip focussed exclusively on

his antics and misadventures in his club, the Goat Hill Lodge of the Ancient

Order of American Grenadiers.

In

the dailies, Weiss alternated straight Mickey Finn detective stories with

humorous ones about Uncle Phil. I asked him if it was easier to do a straight

story than a humorous one.

"I

think so," he said. "But sometimes you'd hit on a good one that sort

of wrote itself. But it's interesting: most actors that I know will tell you

that it's easier to play a straight character than to play comedy. Comedians

will have much more success in a dramatic role than a dramatic actor in a comic

role. It's maybe easier to get someone to cry in a movie than to laugh."

"Where

did you get story ideas?" I wanted to know, unearthing the oldest

interview chestnut of them all.

"You

never know," Weiss said with a grin. "Edwina told me that years

ago: You'll never know where you get ideas from, she said, but you'll get

them. You just never know. I would try —when I came close to the end of a

story, my mind was already wondering where I would go next. I watched movies.

I watched television. I read papers. And if I saw something I liked, I would

say, How can I twist it around and use it?"

"It

might be a newsstory, a news item—"

"Yes,"

he said, "that happened quite a few times."

One

of the first stories Weiss did after Leonard retired sprang from Weiss's

childhood love of the movies. Fascinated by the silent flickers he saw in the

neighborhood theaters of New York's Lower East Side (to which his family had

moved from Philadelphia when he was nine), he revisited some of his favorite

movie stars by doing a story about many of them who were still around in 1968.

"Richard

Lamparski, the author of those I-wonder-what-became-of books, was kind enough

to give me phone numbers and addresses of the actors and actresses, since I

needed their written permission to draw them in the strip," Weiss

explained. "When I wrote to them, I signed the name Lank Leonard, because

his name still appeared on the comic strip."

Another

of Weiss's favorite stories recounted the culmination of Uncle Phil's courtship

of the attractive widow, Minerva Mutton. "It was an on-again, off-again

romance," Weiss said, "so I decided to invite the readers to vote on

whether Uncle Phil and Minerva should get married. They mailed their ballots

in care of their local papers.

"When

Lank read the strip that invited readers to vote, he said, ‘This is a gamble I

would never take: what if the papers don't receive much of a response?’ It

was a calculated risk since Mickey Finn was losing papers at an alarming

rate at the time. By 1970, newspapers were folding, and each collapse reduced

the number of outlets for comic strips. Continuity strips were definitely on

the way out.

"The

response, however, was overwhelming," Weiss continued, "more than

150,000 letters came in. A minister even volunteered to perform the marriage.

Had Mickey Finn been a King Features strip, they would have publicized

the event with a double-page ad in Editor & Publisher."

Weiss's

first audience was always his wife, Blanche. An accomplished artist in her own

right, she is also, Weiss said, "a great editor and story

consultant."

Mickey

Finn survived for almost eight years after Leonard died. In the end, the

evaporation of newspaper outlets reduced the income from the feature so

drastically that Weiss and McNaught decided to discontinue it with the release

for September 10, 1977. He had stopped writing Joe Palooka by then for

roughly the same reason: the job no longer paid enough to justify the effort.

Suddenly,

as Weiss tells it, he was a free man. "I was like a man let out of

prison," he said. "No more deadlines after forty-two years. A few

months later, I was sitting with a cartoonist friend in New York shortly after Ernie

Bushmiller died. I had done a few Nancy comic books when I was

doing comic books, and my friend knew this, so he told me that the United

Features Syndicate was looking for me in regards to continuing Nancy, a

big money-making strip. But I said, ‘Don't tell them where I am: I've had it

with deadlines; I value my freedom too much,’" he finished with a laugh.

"When

you were starting out," I asked, "did you think you would ever be

doing your own strip?"

"When

I started out, I had doubts, probably like everyone," he said. "And

when I went around and visited cartoonists, I would ask them if they thought I

had enough talent to make it in the business. I needed reassurance. I had no

background. I remember taking some of my drawings to Burris Jenkins, who was then doing sports cartoons for the Journal American, and I said,

‘Mr. Jenkins, do you think I have enough talent to make it?’ And he was very

angry at my question. And he said, ‘Talent won't do it for you.’ He said,

‘It's how hard you're willing to work. It doesn't matter how much talent you

have; someone can have much more talent than you, and they won't get anywhere.

But if you're willing to work and work and work, and learn and learn because

you have so much to learn, then you'll make it.’

"And

that was the best answer I could have hoped for," Weiss said.

"Because it meant I could make it if I kept drawing and drawing and

working and working."

"Interesting,"

I said. "It was the drawing you were looking for reassurance on. You

didn't walk in with a story in your head and wonder if you could do a story.

What you wanted to know was, would they tell you that you could draw well

enough. And I guess you assumed that if the day came that you were doing a

strip, the stories would arise by themselves somehow."

"Exactly,"

Weiss said. "But what I didn't know was that the ability to write doesn't

come until later years. When I was twenty-five years old, I started a gag

feature for the Philadelphia Ledger Syndicated called It Never Fails.

And it didn't go anywhere. It failed. I wasn't the humorist; I learned that I

wasn't a gag writer.

"Even

when I was doing the Joe Jinks strip," he continued, "I was

just drawing a story written by someone at the syndicate. I don't think I had

the ability to write until I was maybe thirty years old, until I came out of

the Army. The two years I spent in the Army I think matured me to quite a

degree."

I

said: "But as a young man, you never even thought about writing ability

being important."

"No,"

he said, "the drawing was everything. I figured the story would come. I

didn't realize then that the story is more important than the drawing."

After

what he called his "demise as a cartoonist," Weiss at first

panicked. He called Stan Lee, and although Lee told him he could give him all

the work he wanted, when he found out it was straight illustrative work, he

said, "Oh, no—I'm not going to work that hard. And that was the end of me

as a cartoonist."

But

he had been collecting original paintings and cartoon art all his life, and

when he found out friends of his were looking to acquire the kind of art he was

collecting, he turned his hobby into a new career.

"I

gave it more time," he said, "and I was able to find more paintings

that friends of mine wanted. I became a sort of art dealer—also enhancing my

own collection."

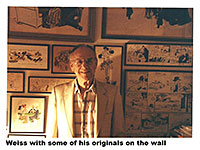

I

looked around the room of his home that we were sitting in. The walls were

festooned with paintings large and small—Leyendecker, Rockwell, Gibson, Flagg,

Abbey, Christy, Harrison Fisher,  Dean Cornwell, Norman Price, and so on. These

were the great illustrators of America's great age of magazine and book

illustration. There were also paintings by his wife Blanche and his son Jerry,

both accomplished artists. Dean Cornwell, Norman Price, and so on. These

were the great illustrators of America's great age of magazine and book

illustration. There were also paintings by his wife Blanche and his son Jerry,

both accomplished artists.

Weiss

continued: "And I had time to devote all my energy to art collecting—to

go to auctions, to make phone calls, and I was very happy. I didn't have deadlines

anymore," he said with a broad grin.

FOOTNOTE:

Weiss died May 18, 2014 in his home at West Palm Beach, Florida at the age of

98. For the story of his involvement with Ham Fisher during the famed feud with

Al Capp, see Hindsight for January 2013, “Hubris and Chutzpah.”

Return to Harv's Hindsights |