BILL

WATTERSON SPEAKS

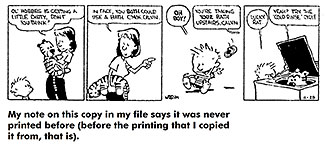

The

Cheapening of the Comics and How (and Why) To Avoid It

Bill

Watterson, who created the inestimable Calvin and Hobbes (November 18, 1985 - December 31, 1995),

was notoriously camera-shy and didn’t give many interviews after the first

couple years of the strip’s run. Watterson is easily the J.D. Salinger of

cartooning.  Two of the interviews he gave after leaving the strip are reported in

Opus 255 and Opus 317; The Comics Journal published a long interview

with him in March 1989 (No.127). In 1996, Ken Tucker, then at Entertainment

Weekly, wrote me a note to tell me he’d interviewed Watterson by phone for

the Philadelphia Inquirer, which ran the interview on April 28, 1987.

Said Tucker: “The Inquirer, true to form, didn’t realize what it had and

ran only about half the quotes I had.” That interview was but one of several

Watterson gave in the first couple years of Calvin and Hobbes. Two of the interviews he gave after leaving the strip are reported in

Opus 255 and Opus 317; The Comics Journal published a long interview

with him in March 1989 (No.127). In 1996, Ken Tucker, then at Entertainment

Weekly, wrote me a note to tell me he’d interviewed Watterson by phone for

the Philadelphia Inquirer, which ran the interview on April 28, 1987.

Said Tucker: “The Inquirer, true to form, didn’t realize what it had and

ran only about half the quotes I had.” That interview was but one of several

Watterson gave in the first couple years of Calvin and Hobbes.

Watterson

gave two speeches that I know about and, for the everlasting record, both of

them appear here. The first, given in October 1989, is a blistering but well

reasoned indictment of the syndicated comics industry. The second, the

commencement address he gave at his alma mater seven months later, only

half-way through the run of Calvin

and Hobbes, is more about the creative impulse and the pitfalls of selling

out than about cartooning, but it also offers insights into why Watterson

steadfastly refused to let his syndicate, Universal Press, merchandise his

characters.

THE

CHEAPENING OF THE COMICS

Speech by

Bill Watterson delivered at the Festival of Cartoon Art, Ohio State University,

October 27, 1989. Boldface emphases added.

I RECEIVED A

LETTER from a 10-year-old this morning. He wrote, "Dear Mr Watterson, I

have been reading Calvin and Hobbes for a long

time, and I'd like to know a few things. First, do you like the drawing of

Calvin and Hobbes I did at the bottom of the page? Are you married, and do you

have any kids? Have you ever been convicted of a felony?"

What

interested me about this last question was that he didn't ask if I'd been

apprehended or arrested, but if I'd been convicted. Maybe a lot of cartoonists

get off on technicalities, I don't know. It also interests me that he naturally

assumed I wasn't trifling with misdemeanors, but had gone straight to

aggravated assaults and car thefts.

Seeing

the high regard in which cartoonists are held today, it may surprise you to

know that I've always wanted to draw a comic strip. My dad had a couple of Peanuts books that were among the first things I

remember reading. One book was called "Snoopy," and it had a blank

title page. The next page had a picture of Snoopy. I apparently figured the

publisher had supplied the blank title page as a courtesy so the reader could

use it to trace the drawing of Snoopy underneath. I added my own frontispiece

to my dad's book. and afterward my dad must not have wanted the book back

because I still have it.

Peanuts,

Pogo, and Krazy Kat have inspired me the most over the years.

These strips are different in almost every way, but their worlds captivated me.

Looking back on them, I think they can teach us something about comic strip

potential.

Peanuts was my introduction to the world of

the comic strip, and Peanuts captured my

imagination like nothing else. Because it was the first strip I read, its many

innovations were lost on me, and I suspect most readers of Peanuts today have forgotten how it single-handedly

reconfigured the comic strip landscape in a few short years. The flat, simple

drawings, the intellectual children, the animal with thoughts and

imagination—all these things are commonplace now, and it's hard to imagine what

a revolutionary strip it was in the '50s and '60s. All I knew was that it had a

magic that other strips didn't.

A

lot of the magic for me is in those deceptively simple, stylized drawings. For

me, the few lines that make up each character, their faces, and gestures are

remarkably expressive. Two dots with parentheses around them have become the

cartoon shorthand for eyes looking uneasy or insecure. When Charlie Brown's eyes

do that, you know his stomach hurts,

Peanuts has held my interest for many years

because the strip is very funny on one level and very sad on another. Charlie

Brown suffers - and suffers in a small, private, honest way. Schultz draws

those quiet moments of self-doubt: Charlie Brown sitting on the bench, eating

peanut butter, trying to work up the nerve to talk to the little red-haired

girl - and failing. As a kid, I read Peanuts for

the funny drawings and the jokes, and later I realized that the childhood

struggles of the strip are metaphors for adult struggles as well.

Peanuts is about the search for acceptance, security, and love,

and how hard those self-affirming things are to find. The strip is also about

alienation, about ambition, about heroes, about religion, and about the search

for meaning and "happiness" in life. For a comic strip, it digs

pretty deep.

Of

course, the strip has a flair for weird humor, too. Snoopy in goggles, his

doghouse somehow riddled with bullet holes, yelling, "Curse you, Red

Baron!" is, I submit, as bizarre an image as anything ever seen on the

comics page. Peanuts defined the contemporary

comic strip.

And Pogo? Pogo was an

almost opposite approach to the comic strip. The drawings were as lush as the

foliage of its Okefenokee setting, and the dialogue was as lush as the

drawings. With the possible exception of Porkypine, there was not a

soul-searching character in the cast of hundreds. Pogo was trusting,

good-natured, and innocent, which generally meant it was Pogo's larder that got

ransacked whenever someone got hungry. Most of the other characters were

bombastic, short-sighted, full of self-importance, and not just a little

stupid. What better vehicle for political satire and commentary? Pogo was largely before my time, so, like Peanuts, I can only imagine how it must have shocked

its first readers. Considering how controversial many papers find Doonesbury in the 1980s, one has to wonder how Pogo got away with its political criticism 30 years

earlier.

Again,

much of Pogo's magic for me was in the beautiful

drawings. where the animals looked so real and animated you imagined their

noses were probably cold to the touch. Part of the magic was the amazing

dialects they spoke, which mangled English with awful puns and unintended

meanings. Part of it was the gutsiness of attacking the fur right on the

"funny" pages and pulling no punch. Part of it was the strip's basic

faith in human decency underneath all the smoke and bluster. Part of it was the

rambling storytelling, where every main road to the conclusion was avoided in

favor of endless detours. Part of it was that Grundoon talked only in

consonants, P.T. Bridgeport talked in circus posters, and Deacon Mushrat talked

in Gothic type. And, of course, part of it was that it was very, very funny.

The strip had a mood, a pace, and atmosphere that has not been seen since in

comics.

I

discovered Krazy Kat when a large anthology of

the strip was published in 1969. The book is an editorial disaster, but it did

show a lot of Krazy Kat strips, and I admired the

work immediately. Krazy Kat seems to be one of

those strips people either love or don't get at all. Krazy

Kat is nothing but variations on a simple theme, so the magic of the

strip is not so much in what it says but in how it says it. Ignatz Mouse throws

bricks at Krazy out of contempt, but Krazy interprets this as a gesture of

affection instead. Meanwhile, the law— Offissa Pupp— futilely tries to

interfere with a process that's completely satisfying to all parties for all

the wrong reasons. This weird, recycling plot can be interpreted as a metaphor

for love or politics—or it can just be enjoyed for its own lunatic charms. The

strip constantly plays with its own form, and becomes a sort of essay on

cartoon existentialism. The background scenery changes from panel to

panel, and day can turn to night and back again during a brief conversation.

Similarly,

Herriman played with language and dialect, inserting Spanish, phonetically

spelled mispronounced words, slang, and odd, alliterative phrases, giving the

strip a unique atmosphere. The drawings are scratchy and peculiar, but they

provide a beautiful visual context to the equally idiosyncratic writing. Krazy Kat's sparse Arizona landscape, like Pogo's dense Georgia swamp, is more than a backdrop.

The land is really a character in the story, and it gives a specific mood and

flavor to all the proceedings. The constraint of Krazy Kat's narrow plot seems to have set free every other aspect of the cartoon to become

poetry, and the strip is, to my mind, cartooning at its most pure.

These

three strips showed me the incredible possibilities of the cartoon medium, and

I continue to find them inspiring. All these strips work on many levels,

entertaining while they deal with other issues. These strips reflect uniquely personal views of the world, and we are richer for the

artists' visions. Reading these strips, we see life through new eyes, and maybe

understand a little more—or at least appreciate a little more—some of the

absurdities of our world. These strips are just three of my personal

favorites, but they give us some idea of how good comics can be. They argue

powerfully that comics can be vehicles for beautiful artwork and serious,

intelligent expression.

In

a way, it's surprising that comic strips have ever been that good. The comics

were invented for commercial purposes. They were, and are, a graphic feature

designed to help sell newspapers. Cartoonists work within severe space

constraints on an inflexible deadline for a mass audience. That's not the most

conducive atmosphere for the production of great art, and of course many comic

strips have been eminently dispensable. But more than occasionally, wonderful

work has been produced.

Amazingly,

much of the best cartoon work was done early on in the medium's history. The

early cartoonists, with no path before them, produced work of such

sophistication, wit, and beauty that it increasingly seems to me that cartoon

evolution is working backward. Comic strips are moving toward a primordial goo rather than away from

it.As a cartoonist, it's a bit humiliating to read work that was done

over 50 years ago and find it more imaginative than what any of us are doing

now. We've lost many of the most precious qualities of comics. Most readers

today have never seen the best comics of the past, so they don't even know what

they're missing. Not only can comics be

more than we're getting today. but the comics already have

been more than we're getting today. The reader is being gypped and

he doesn't even know it.

Consider

only the most successful strips in the papers today. Why are so many of them

poorly drawn? Why do so many offer only the simplest interchangeable gags and

puns? Why are some strips written by committees and drawn by assistants? Why

are some strips still stumbling around decades after their original creators

have retired or died? Why are some strips little more than advertisements for

dolls and greeting cards? Why do so many of the comics look the same?

If

comics can be so much, why are we settling for so little? Can't we expect more

from our comics pages?

Well,

these days, probably not. Let's look at why.

The

comics are a collaborative effort on the part of the cartoonists who draw them,

the syndicates that distribute them, and the newspapers that buy and publish

them. Each needs the other, and all have common interest in providing comics

features of a quality that attracts a devoted readership. But business and art

almost always have a rocky marriage, and in comic strips today the interests of

business are undermining the concerns of the art.

Part

of the problem is that the very idea that cartoons could be art has been slow

to take hold. I talked about Krazy Kat, Pogo, and Peanuts to show that the best cartoons have a

serious purpose underneath the jokes and funny pictures. True, comics are a

popular art, and yes, I believe their primary obligation is to entertain, but

comics can go beyond that, and when they do, they move from silliness to

significance.

The

first comic strip cartoonists were staff artists of major newspapers, and

consequently, from the beginning, cartoonists were regarded as simple employees

of their publishers rather than artists. When the creator of a popular strip

left his employer, the cartoonist was rarely able to take his creation with him

intact. Very early strips, such as The Yellow Kid, The

Katzenjammer Kids, and Buster Brown, all

appeared in two versions, one by the original creator and one by an imitator

hired by the publisher who lost the creator. The comic strip came into being as

a staff-produced graphic, and comics have never escaped the perception that

they are a newspaper "feature," like a weather report, instead of a

forum for individual expression. In fact, despite the grim violence of Dick

Tracy, the conservative politics of Little Orphan Annie, the social

satire of Li'l Abner, and the shapely women that have graced dozens of

other strips, the comics have somehow come to be thought of as

entertainment for children. Cartoonists are widely regarded as the newspaper

equivalent of Captain Kangaroo. The idea that comics are potentially

one of the most versatile artforms is sadly foreign. Our expectations and

demands for comics are not high.

Today,

comic strip cartoonists work for syndicates, not individual newspapers, but 100

years into the medium it's still the very rare cartoonist who owns his

creation. Before agreeing to sell a comic strip, syndicates generally demand

ownership of the characters, copyright, and all exploitation rights. The

cartoonist is never paid or otherwise compensated for giving up these rights:

he either gives them up or he doesn't get syndicated.

The

syndicates take the strip and sell it to newspapers and split the income with

the cartoonists. Syndicates are essentially agents. Now, can you imagine a

novelist giving his literary agent the ownership of his characters and all

reprint, television, and movie rights before the agent takes the manuscript to

a publisher? Obviously, an author would have to be a raving lunatic to agree to

such a deal, but virtually every cartoonist does exactly that when a syndicate

demands ownership before agreeing to sell the strip to newspapers. Some

syndicates take these rights forever, some syndicates for shorter periods, but

in any event, the syndicate has final authority and control over artwork it had

no hand in creating or producing. Without creator control over the work,

the comics remain a product to be exploited, not an art.

Why

does this happen? As the syndicates will tell you, no cartoonist is forced to

sign the ridiculous contracts the syndicates offer. The cartoonist is free to

stay in his $3.50 an hour bag boy job until he can think of a better way to get

his strip in the newspapers. Simply put, the syndicates offer virtually the

only shot for an unknown cartoonist to break into the daily newspaper market. The

syndicates therefore use their position of power to extort rights they do not

deserve.

Sacrificing

ownership has serious consequences for the artist. For starters, it allows the

syndicate to view the creator as a replaceable part. To most syndicates,

the creator of a popular strip is no more valuable than a hired flunky who can

mimic the original. Some syndicates can replace a cartoonist at will,

and most syndicates can replace a cartoonist as soon as he quits, retires, or

dies. This attitude is simply unconscionable, but it's the standard practice of

business.

Cartoonists

and syndicates alike tend to exaggerate the syndicate's role in making strips

successful. Ultimately, though, the level of sales is determined a lot more by

how good the strip is than by who sells it. Reader polls across the country

shows surprising consensus about which strips are good, and editors do their

best to print what the readers want. The syndicates bring the cartoon to the

market, but they can't keep it there. Only the cartoonist can do that. Syndicates

simply do not need or deserve comic strip ownership for the job they do.

By

having complete control over the comic strip, the syndicate can ruin the work.

Although there has never, ever been a successor to a comic strip half as good

as the original creator, passing strips down through generations like

secondhand clothes has been the standard practice of the business since it

began. Incredibly, syndicates still today tell young artists that they're not

good enough to draw their own strip, but they are good enough to carry on the

work of some legendary strip instead. Too often, syndicates would rather have

the dwindling income of a doddering dinosaur than let the strip die and risk

losing the spot to a rival syndicate. Consequently, the comics pages are

full of dead wood. Strips that had some relevance to the world during

the depression are now being continued by baby boomers, and the results are

embarrassing.

Suppose

you're a painter and you go to an art gallery to see if they'll represent you.

They look at your work and shake their heads. But, since you show some basic

familiarity with a paintbrush, they ask if you'd like to continue Rembrandt's

work. After all, you can paint. Rembrandt's dead, and some buyers would rather

have a Rembrandt forgery than no Rembrandt at all. It's an absurd

scenario, but this is what goes on in comic strip syndication.

Comic

strips have a natural lifetime, and any cartoonist ought to be able to quit or

retire without fear that his syndicate will hire some hack illustrator to keep

the work going. It's time syndicates stopped maiming their comic strips by

passing them on to official plagiarists. It's also time that the would-be

successors of comic strips had more respect for their own talents and for the

work of those who created something original. If someone wants to be a

cartoonist, let's see him develop his own strip instead of taking over the

duties of someone else's. We've got too many comic strip corpses being

propped up and passed for living by new cartoonists who ought to be doing

something of their own. If a cartoonist isn't good enough to make it on

his own work, he has no business being in the newspaper.

Syndicate

ownership of strips also gives them control over comic strip merchandising.

Today, newspaper sales can't bring in a fraction of the money that licensing

can bring. As the number of newspapers has diminished, and as the remaining

papers run pretty much the same 20 strips everywhere, the growth of a syndicate

now depends on dolls and greeting cards more than newspaper sales.

Consequently, the quickest contracts are going to strips with licensing

potential. One syndicate developed a comic strip after it

had settled on the products: the strip was essentially to be an advertisement

for the dolls and television shows already planned. The syndicate developed the

characters and then found someone to draw the strip. Lots of heart and

integrity in that kind of strip, yes sir. Even in

strips with more honorable beginnings, the syndicates are only too happy to

sell out a comic strip for a quick and temporary buck, and their ownership and

control allows them to do just that.

Of

course, to be fair to the syndicates, most cartoonists are happy to sell

out, too. Although not to the present extent, licensing has been around

since the beginning of the comic strip, and many cartoonists have benefitted

from the increased exposure. The character merchandise not only provides the

cartoonist with additional income, but it puts his characters in new markets

and has the potential to broaden the base of the strip and attract new readers.

I'm not against all licensing for all strips. Under the control of a

conscientious cartoonist, certain kinds of strips can be licensed tastefully

and with respect to the creation. That said, I'll add that it's very rarely

done that way. With the kind of money in licensing nowadays, it's not

surprising many cartoonists are as eager as the syndicates for easy millions,

and are willing to sacrifice the heart and soul of the strip to get it. I say

it's not surprising, but it is disappointing.

Some

very good strips have been cheapened by licensing. Licensed products, of

course, are incapable of capturing the subtleties of the original strip, and

the merchandise can alter the public perception of the strip, especially when

the merchandise is aimed at a younger audience than the strip is. The

deeper concerns of some strips are ignored or condensed to fit the simple gag

requirements of mugs and T-shirts. In addition, no one cartoonist has the time

to write and draw a daily strip anddo all the work of a

licensing program. Inevitably, extra assistants and business people are

required, and having so many cooks in the kitchen usually encourages a

blandness to suit all tastes. Strips that once had integrity and heart become

simply cute as the business moguls cash in. Once a lot of money and jobs are

riding on the status quo, it gets harder to push the experiments and new

directions that keep a strip vital. Characters lose their believability

as they start endorsing major companies and lend their faces to bedsheets and

boxer shorts. The appealing innocence and sincerity of cartoon characters is

corrupted when they use those qualities to peddle products. One starts

to question whether characters say things because they mean it or because their

sentiments sell T-shirts and greeting cards. Licensing has made some

cartoonists extremely wealthy, but at a considerable loss to the precious

little world they created. I don't buy the argument that licensing can go at

full throttle without affecting the strip. Licensing has become a monster.

Cartoonists have not been very good at recognizing it, and the syndicates don't

care.

And

then we have established cartoonists who have grown so cavalier about their

jobs that they sign strips they haven't written or drawn. Anonymous assistants

do the work while the person getting the credit is out on the golf course.

Aside from the fundamental dishonesty involved, these cartoonists again

encourage the mistaken view that once the strip's characters are

invented, any facile hireling can churn out the material. In these

strips, jokes are written by committee with the goal of not advancing the characters, but of keeping them exactly where they've always

been. So long as the characters never develop, they're utterly predictable, and

hence, so easy to write that a committee can do it. The staff of illustrators

has the same task: to keep each drawing so slick and perfect that it loses all

trace of individual quirk. That way, no one can tell who's doing it. It's

an assembly line production. It's efficient, but it makes for mindless,

repetitive, joyless comics. We need to see more creators taking pride

in their craft, and doing the work they get paid for. If writing and drawing

cartoons has become a burden for them, let's see some early retirements and

some room for new talent.

And

while cartoonists and syndicates continue to cheapen their own product,

newspapers worsen the situation by continually shrinking the comics to ever

smaller sizes.

The

newspaper business has changed. Afternoon papers are failing everywhere, and

few papers are in the competitive situation that comics were invented to promote.

Television brings that latest news at 6 and 11 in full-color action. Newspaper

circulation is not increasing with the population, while newspaper costs

continue to grow. Consequently, over the last several decades, newspapers have

been squeezing the comics into less and less space to cut expenses.

When Krazy Kat was drawn, comics regularly ran as a

full page on Sunday—an entire newspaper page all to itself. Comics were like

posters. Now most papers commonly print strips a quarter of a page on Sundays, and

sometimes even smaller. Daily strips have shrunk, too. Strips had already lost

a lot of space by the time I cut out a Pogo strip

in 1969. Today, 20 years later, I work with almost a third less space than that. As comic strips are printed smaller and smaller,

the drawings and dialogue have to get simpler and simpler to stay legible.

Cartoons are just words and pictures, and you can only eliminate so much of

either before a cartoon is deprived of its ability to entertain.

The

adventure strip, a newspaper staple in the '40s, has all but wasted away, and

we've lost much of the diversity of which the comics are capable. It's not too

surprising. At current sizes, there is no room for real dialogue, no room

to show action, no room to show exotic worlds or foreign lands, no room to tell

a decent story. Consequently, today's comics pages are filled with cartoon

characters who sit in blank backgrounds spouting silly puns. Conversation in a comic strip is a thing of the past. The wonderful dialects

and wordplays of Krazy Kat and Pogo are as impossible now as the beautiful

draftsmanship that characterized those strips and others. All the talk

about how "sophisticated" comics have become shows a woeful ignorance

of what comics used to be like. Comics are simpler and dumber than ever.

The

situation is ironic. All across the country, newspapers are going to great

expense to add color photographs, fancy graphics, and bold design to their

pages in order to entice readers away from the steady blue light of their TV

screens. It is strange that after all that expense and work, newspapers refuse

to take advantage of the comic strip, the one newspaper graphic that television

cannot imitate. When 20 strips are reduced and crammed into two monotonous

columns on one page, the result is singularly unattractive and uneffective. Newspapers

pay for their comics and then refuse to let comics do their job.

Here,

then, is the situation: despite the proven popularity of the comics, newspapers

print them miserably, while syndicates have taken it on themselves to control,

exploit, and cheapen their product. Between the two, cartoonists all but

abandon the artistic responsibilities of their craft. Somehow, I can't shake the idea that

this isn't how cartooning is supposed to be—and that cartooning will never be

more than a cheap, brainless commodity until it's published differently.

What

can be done? I'm not a businessman, but I'll toss out some ideas just to start

some discussion.

First

of all, we should keep in mind that newspapers and syndicates are by no means

essential to the production of comics, There are all sorts of ways to publish

cartoons, and if syndicates and newspapers won't hold up their end of the

bargain, maybe there's an opportunity for a new kind of publisher. Let's

start with eliminating both the syndicate and the newspaper. Consider

for a moment that there may well be a market for comic books that has never

been tapped simply because comic books have traditionally been an even

sloppier, dumber, and more exploitive market than newspaper comics. But suppose

someone published a quality cartoon magazine. Imagine full-color, big comics in

a lush, glossy format. Why not? Just because cartoons have always been treated

as schlock doesn't mean that sleazy packaging, cheap paper, poor color, bad

writing, and crude art are what comics are all about. Imagine a publisher who

recognizes that the way to attract readers is to give them quality cartoons—and

that the way to get quality cartoons is to offer artists a quality format and artistic

freedom. Is it inconceivable such a venture would work?

Or

let's say we keep the syndicates but abandon the newspapers. So long as

newspapers refuse to respect the legitimate needs of the comic strip, why don't

the syndicates take control of their product and publish the comics themselves?

Each syndicate could put out a weekly comic book of all its strips. Comic books

originally started as reprints of newspaper comics, and they were so popular an

industry was created to produce new comic books to fill the demand. Suppose the

syndicate gives each of its cartoonists five pages to draw and color any way he

wants, then binds the results, and sells them at chain bookstores and in

supermarkets with the magazines and tabloids. Offer subscriptions, too, what

the heck. Think of all the kids who unload $10 a week collecting miserably done

superhero comics, and you know there's got to be a market out there somewhere.

What syndicate is going to try something new to showcase the talent it's

collected?

Or

let's say we keep the syndicates and the newspapers. There are still

ways to improve comics. For one thing, the syndicates could again take over the

printing, and the comics could be sold to papers as a preprinted insert. Or the

syndicates could print the insert with advertising, and let the ads pay for its

inclusion in the newspaper. Either way, the syndicates could start printing

their comics big, in color, and on good quality paper that people could keep

and collect. If advertisers are paying for the comics section inserts, for

example, editors can hardly complain that they don't get a citywide exclusive

on their strips.

Or,

if we assume no syndicate has the foresight to promote the quality of its own

product, at the very least one would think an imaginative newspaper editor

could come up with a way to add another half-page of space to the comics

section and print the work as it was intended to be published. Given the

readership of the comics page, couldn't an advertiser or two be persuaded to

sponsor the comics section for a single ad of his alone at the top of the page?

I don't believe all the possibilities have been exhausted.

I

admit my ideas here are rough. Obviously, if I had any business savvy at all

myself, I'd lump the whole business tomorrow and self-publish. See, that's another alternative! My point is simply that cartoons

are not necessarily doomed to increasing stupidity and crude craftsmanship.

With the right publishing, comics can move into whole new worlds we've never

seen. Moreover, I think any effort to improve the quality of comics would very

likely be rewarded in the marketplace. Think of the people who cut out certain

comics to put on refrigerators, or to put in scrapbooks, or to send in letters,

or to stick on their office walls. Give them a nicely printed, big color comic

on good paper and see if they don't jump. I think the public would respond if

there was a publisher out there with an ounce of vision. For too long,

syndicates and cartoonists have been congratulating themselves whenever things

don't get worse. I don't think that's good enough. This very weekend

we've got syndicate executives, cartoonists, readers, and newspaper people all

together. Let's knock some heads together and see what we can do. Let's ask

people what they're doing to improve the state of comics.

I

started out talking about Peanuts, Pogo, and Krazy Kat. These strips suggest a world of

possibilities that cartoons can offer. Comics are capable of being anything the

mind can imagine. I consider it a great privilege to be a cartoonist. I love my

work, and I am grateful for the incredible forum I have to express my thoughts.

People give me their attention for a few seconds every day, and I take that as

an honor and a responsibility. I try to give readers the best strip I'm capable

of doing. I look at cartoons as an art, as a form of personal expression.

That's why I don't hire assistants, why I write and draw every line myself, why

I draw and paint special art for each of my books, and why I refuse to dilute

or corrupt the strip's message with merchandising. I want to draw

cartoons, not supervise a factory. I had a lot of fun as a kid reading

comics, and now I'm in the position where I can return some of that fun. I try

to draw the kind of strip I'd like to read, but I'm not entirely able to. This

business keeps me from doing the quality work I'd like to be doing— and because

I'm being cheated, so are my readers.

Newspapers

can do better. Syndicates can do better. Cartoonists can do better. The

business interests, in the name of efficiency, mass marketability, and profit,

profit, profit are catering to the lowest common denominator of readership and

are keeping this artform from growing. There will always be mediocre comic

strips, but we have lost much of the potential for anything else. We need more

variety on the comics page, not less. Those of us who care about the comics

need to start speaking up. This is an excellent place and time to do it.

SOME

THOUGHTS ON THE REAL WORLD

BY ONE WHO

GLIMPSED IT AND FLED

Bill

Watterson, Kenyon College Commencement. May 20, 1990. Boldface emphases added.

I HAVE A

RECURRING DREAM ABOUT KENYON. In it, I'm walking to the post office on the way

to my first class at the start of the school year.  Suddenly it occurs to

me that I don't have my schedule memorized, and I'm not sure which classes I'm

taking, or where exactly I'm supposed to be going. As I walk up the steps to

the postoffice, I realize I don't have my box key, and in fact, I can't

remember what my box number is. I'm certain that everyone I know has written me

a letter, but I can't get them. I get more flustered and annoyed by the minute.

I head back to Middle Path, racking my brains and asking myself, "How many

more years until I graduate? ...Wait, didn't I graduate already?? How old am I?" Then I wake up. Suddenly it occurs to

me that I don't have my schedule memorized, and I'm not sure which classes I'm

taking, or where exactly I'm supposed to be going. As I walk up the steps to

the postoffice, I realize I don't have my box key, and in fact, I can't

remember what my box number is. I'm certain that everyone I know has written me

a letter, but I can't get them. I get more flustered and annoyed by the minute.

I head back to Middle Path, racking my brains and asking myself, "How many

more years until I graduate? ...Wait, didn't I graduate already?? How old am I?" Then I wake up.

Experience

is food for the brain. And four years at Kenyon is a rich meal. I suppose it

should be no surprise that your brains will probably burp up Kenyon for a long

time. And I think the reason I keep having the dream is because its central

image is a metaphor for a good part of life: that is, not knowing where you're

going or what you're doing.

I

graduated exactly ten years ago. That doesn't give me a great deal of

experience to speak from, but I'm emboldened by the fact that I can't remember

a bit of my commencement, and I trust that in half an hour, you

won't remember of yours either.

In

the middle of my sophomore year at Kenyon, I decided to paint a copy of

Michelangelo's "Creation of Adam" from the Sistine Chapel on the

ceiling of my dorm room. By standing on a chair, I could reach the ceiling, and

I taped off a section, made a grid, and started to copy the picture from my art

history book.

Working

with your arm over your head is hard work, so a few of my more ingenious

friends rigged up a scaffold for me by stacking two chairs on my bed, and

laying the table from the hall lounge across the chairs and over to the top of

my closet. By climbing up onto my bed and up the chairs, I could hoist myself

onto the table, and lie in relative comfort two feet under my painting. My

roommate would then hand up my paints, and I could work for several hours at a

stretch.

The

picture took me months to do, and in fact, I didn't finish the work until very

near the end of the school year. I wasn't much of a painter then, but what the

work lacked in color sense and technical flourish, it gained in the incongruity

of having a High Renaissance masterpiece in a college dorm that had the

unmistakable odor of old beer cans and older laundry.The painting lent an air

of cosmic grandeur to my room, and it seemed to put life into a larger

perspective. Those boring, flowery English poets didn't seem quite so

important, when right above my head, God was transmitting the spark of life to

man.

My

friends and I liked the finished painting so much in fact, that we decided I

should ask permission to do it. As you might expect, the housing director was

curious to know why I wanted to paint this elaborate picture on my ceiling a

few weeks before school let out. Well, you don't get to be a sophomore at

Kenyon without learning how to fabricate ideas you never had, but I guess it

was obvious that my idea was being proposed retroactively. It ended up that I

was allowed to paint the picture, so long as I painted over it and returned the

ceiling to normal at the end of the year. And that's what I did.

Despite

the futility of the whole episode, my fondest memories of college are times

like these, where things were done out of some inexplicable inner imperative,

rather than because the work was demanded. Clearly, I never spent as much time

or work on any authorized art project, or any poli-sci paper, as I spent on

this one act of vandalism.

It's

surprising how hard we'll work when the work is done just for ourselves. And

with all due respect to John Stuart Mill, maybe utilitarianism is overrated. If

I've learned one thing from being a cartoonist, it's how important playing is

to creativity and happiness. My job is essentially to come up with 365 ideas a

year.If you ever want to find out just how uninteresting you really are, get a

job where the quality and frequency of your thoughts determine your livelihood.

I've found that the only way I can keep writing every day, year after year, is

to let my mind wander into new territories. To do that, I've had to cultivate a

kind of mental playfulness.

We're

not really taught how to recreate constructively. We need to do more than

find diversions; we need to restore and expand ourselves. Our idea of

relaxing is all too often to plop down in front of the television set and let

its pandering idiocy liquefy our brains. Shutting off the thought process is

not rejuvenating; the mind is like a car battery: it recharges by running.

You

may be surprised to find how quickly daily routine and the demands of

"just getting by” absorb your waking hours. You may be surprised to find

how quickly you start to see your politics and religion become matters of habit

rather than thought and inquiry. You may be surprised to find how quickly you

start to see your life in terms of other people's expectations rather than

issues. You may be surprised to find out how quickly reading a good book sounds

like a luxury.

At

school, new ideas are thrust at you every day. Out in the world, you'll have to

find the inner motivation to search for new ideas on your own. With any luck at

all, you'll never need to take an idea and squeeze a punchline out of it, but

as bright, creative people, you'll be called upon to generate ideas and

solutions all your lives. Letting your mind play is the best way to solve

problems. For me, it's been liberating to put myself in the mind of a

fictitious six year-old each day, and rediscover my own curiosity. I've been

amazed at how one idea leads to others if I allow my mind to play and wander. I

know a lot about dinosaurs now, and the information has helped me out of quite

a few deadlines. A playful mind is inquisitive, and learning is fun. If you

indulge your natural curiosity and retain a sense of fun in new experience, I

think you'll find it functions as a sort of shock absorber for the bumpy road

ahead.

So,

what's it like in the real world? Well, the food is better, but beyond that, I

don't recommend it.

I

don't look back on my first few years out of school with much affection, and if

I could have talked to you six months ago, I'd have encouraged you all to

flunk some classes and postpone this moment as long as possible. But

now it's too late. Unfortunately, that was all the advice I really had. When I

was sitting where you are, I was one of the lucky few who had a cushy job

waiting for me. I'd drawn political cartoons for the Collegian for four

years, and the Cincinnati Post had hired me as an editorial cartoonist.

All my friends were either dreading the infamous first year of law school, or

despondent about their chances of convincing anyone that a history degree had

any real application outside of academia.

Boy,

was I smug.

As

it turned out, my editor instantly regretted his decision to hire me. By the

end of the summer, I'd been given notice; by the beginning of winter, I was in

an unemployment line; and by the end of my first year away from Kenyon, I was

broke and living with my parents again. You can imagine how upset my dad was

when he learned that Kenyon doesn't give refunds. Watching my career explode on

the launchpad caused some soul searching. I eventually admitted that I didn't

have what it takes to be a good political cartoonist, that is, an interest in

politics, and I returned to my first love, comic strips. For years I got

nothing but rejection letters, and I was forced to accept a real job.

A real job is a job you hate. I designed car ads and grocery ads in

the windowless basement of a convenience store, and I hated every single

minute of the 4-1/2 million minutes I worked there. My fellow prisoners

at work were basically concerned about how to punch the time clock at the

perfect second where they would earn another 20 cents without doing any work

for it. It was incredible: after every break, the entire staff would stand

around in the garage where the time clock was, and wait for that last click.

And after my used car needed the head gasket replaced twice, I waited in the

garage too.

It's

funny how at Kenyon, you take for granted that the people around you think

about more than the last episode of “Dynasty.” I guess that's what it means to

be in an ivory tower.

Anyway,

after a few months at this job, I was so starved for some life of the mind

that, during my lunch break, I used to read those poli-sci books that I'd

somehow never quite finished when I was here. Some of those books were actually

kind of interesting. It was a rude shock to see just how empty and robotic life

can be when you don't care about what you're doing, and the only reason you're

there is to pay the bills.

Thoreau

said, "The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation."

That's

one of those dumb cocktail quotations that will strike fear in your heart as

you get older. Actually, I was leading a life of loud desperation.

When

it seemed I would be writing about "Midnite Madness Sale-abrations"

for the rest of my life, a friend used to console me that cream always

rises to the top. I used to think, so do people who throw themselves into the

sea.

I

tell you all this because it's worth recognizing that there is no such thing as

an overnight success. You will do well to cultivate the resources in yourself

that bring you happiness outside of success or failure. The truth is, most of

us discover where we are headed when we arrive. At that time, we turn around

and say, yes, this is obviously where I was going all along. It's a good idea

to try to enjoy the scenery on the detours, because you'll probably take a few.

I

still haven't drawn the strip as long as it took me to get the job. To endure

five years of rejection to get a job requires either a faith in oneself that

borders on delusion, or a love of the work. I loved the work. Drawing comic

strips for five years without pay drove home the point that the fun of

cartooning wasn't in the money; it was in the work. This turned out to be an

important realization when my break finally came.

Like

many people, I found that what I was chasing wasn't what I caught. I've wanted

to be a cartoonist since I was old enough to read cartoons, and I never really

thought about cartoons as being a business. It never occurred to me that a

comic strip I created would be at the mercy of a bloodsucking corporate

parasite called a syndicate, and that I'd be faced with countless ethical

decisions masquerading as simple business decisions. To make a business

decision, you don't need much philosophy; all you need is greed, and maybe a

little knowledge of how the game works.

As

my comic strip became popular, the pressure to capitalize on that popularity

increased to the point where I was spending almost as much time screaming at

executives as drawing. Cartoon merchandising is a $12 billion dollar a year

industry and the syndicate understandably wanted a piece of that pie. But the

more I though about what they wanted to do with my creation, the more

inconsistent it seemed with the reasons I draw cartoons. Selling out is

usually more a matter of buying in. Sell out, and you're really buying

into someone else's system of values, rules and rewards. The so-called

"opportunity" I faced would have meant giving up my individual voice

for that of a money-grubbing corporation. It would have meant my purpose

in writing was to sell things, not say things. My pride in craft would

be sacrificed to the efficiency of mass production and the work of assistants.

Authorship would become committee decision. Creativity would become work for

pay. Art would turn into commerce. In short, money was supposed to supply

all the meaning I'd need.

What

the syndicate wanted to do, in other words, was turn my comic strip into

everything calculated, empty and robotic that I hated about my old job. They

would turn my characters into television hucksters and T-shirt sloganeers and

deprive me of characters that actually expressed my own thoughts.

On

those terms, I found the offer easy to refuse. Unfortunately, the syndicate

also found my refusal easy to refuse, and we've been fighting for over three

years now. Such is American business, I guess, where the desire for

obscene profit mutes any discussion of conscience.

You

will find your own ethical dilemmas in all parts of your lives, both personal

and professional. We all have different desires and needs, but if we don't

discover what we want from ourselves and what we stand for, we will live

passively and unfulfilled. Sooner or later, we are all asked to compromise

ourselves and the things we care about. We define ourselves by our actions.

With each decision, we tell ourselves and the world who we are. Think about

what you want out of this life, and recognize that there are many kinds of

success. Many of you will be going on to law school, business school, medical school,

or other graduate work, and you can expect the kind of starting salary that,

with luck, will allow you to pay off your own tuition debts within your own

lifetime.

But

having an enviable career is one thing, and being a happy person is

another.

Creating

a life that reflects your values and satisfies your soul is a rare achievement. In a culture that

relentlessly promotes avarice and excess as the good life, a person happy doing

his own work is usually considered an eccentric, if not a subversive. Ambition

is only understood if it's to rise to the top of some imaginary ladder of

success. Someone who takes an undemanding job because it affords him the time

to pursue other interests and activities is considered a flake. A person who

abandons a career in order to stay home and raise children is considered not to

be living up to his potential—as if a job title and salary are the sole measure

of human worth.You'll be told in a hundred ways, some subtle and some not, to

keep climbing, and never be satisfied with where you are, who you are, and what

you're doing. There are a million ways to sell yourself out, and I

guarantee you'll hear about them.

To

invent your own life's meaning is not easy, but it's still allowed, and I think

you'll be happier for the trouble. Reading those turgid philosophers

here in these remote stone buildings may not get you a job, but if those books

have forced you to ask yourself questions about what makes life truthful,

purposeful, meaningful, and redeeming, you have the Swiss Army Knife of mental

tools, and it's going to come in handy all the time.

I

think you'll find that Kenyon touched a deep part of you. These have been

formative years. Chances are, at least, the experience of your roommates has

taught you everything ugly about human nature you ever wanted to know.With

luck, you've also had a class that transmitted a spark of insight or interest

you'd never had before. Cultivate that interest, and you may find a deeper

meaning in your life that feeds your soul and spirit. Your preparation for the

real world is not in the answers you've learned, but in the questions you've

learned how to ask yourself. Graduating from Kenyon, I suspect you'll find

yourselves quite well prepared indeed.

I

wish you all fulfillment and happiness. Congratulations on your achievement.

Phootnit. To its credit,

Universal Press—which, like all syndicates at the time, owned the rights to its

strips, including Calvin

and Hobbes— did not license Watterson’s characters without his

approval—although it had the legal right to do so. Over the years, Universal

established itself as a leader in securing cartoonists’ rights, and it would

violate its own principles by ignoring Watterson’s wishes. The syndicate

eventually realized that the cartoonist would never give in and let Calvin

and Hobbes be merchandised and stopped pestering him. The syndicate,

although disappointed, was sympathetic to Watterson’s view. Lee Salem,

at the time the syndicate official with closest ties to Watterson, said: “We

had a lot of internal discussions. ... Ultimately, we decided it was in our

best interests not to alienate the best cartoonist of his generation.”

Universal renegotiated Watterson’s contract from 20 years to 10 and signed over

the domestic copyright to the strip in 1991. And four years later, Watterson

announced that he would end the strip December 31, 1995, when his ten-year

contract expired.

Return to Harv's Hindsights |