Winnie the

WAC

And the

Other Adventures of Her Creator, Vic Herman

Winnie the

WAC was to the Women’s Army Corps in World War II what Dave Breger’s Private

Breger and George Baker’s Sad Sack and Bill Mauldin’s Willie and Joe were to

the entire U.S. military—a moral booster nonpareil.  . As the only cartoon cutie in the

ranks, she’d returned to duty for the Korean War and, subsequently, for the

hostilities in Vietnam. And in 1993, she was back on active duty—this time,

recruiting for the Women's Army Corps Veteran's Association. And that’s when I

met Winnie’s creator, Vic Herman. . As the only cartoon cutie in the

ranks, she’d returned to duty for the Korean War and, subsequently, for the

hostilities in Vietnam. And in 1993, she was back on active duty—this time,

recruiting for the Women's Army Corps Veteran's Association. And that’s when I

met Winnie’s creator, Vic Herman.

Winnie’s

1993 enlistment began in the spring of that year when Major Rose McGowan, a

retired WWII WAC, discovered that Herman lived in Del Mar, a residential

community within a few stones' throws of San Diego, where McGowan was planning

a 51st WAC anniversary luncheon for the San Diego Mission 50 of the WAC VA.

McGowan promptly secured Herman as a guest of honor for the luncheon, and

within weeks, Winnie was on recruiting posters.

It

was Winnie's fifth comeback. And we should not be surprised at this

unanticipated reincarnation. She takes after her creator, who has spent a

lifetime popping up in unexpected places, first in one career and then in

another. But with Herman, we lose count pretty quickly.

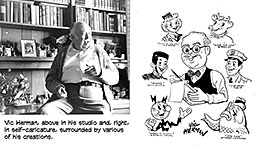

Herman

has been a puppeteer, illustrator, cartoonist, war correspondent, television

producer, art director, head of advertising agency, author, good will

ambassador, and painter. None of these were part-time employments: in every

case, he threw himself wholeheartedly, full-time, into the role he'd chosen and

made a success of it.

And

while running this variegated occupational obstacle course, Herman participated

in the creation or revitalization of several icons of the advertising

world—Elsie the Borden Cow, Reddy Kilowatt, Johnny the Philip Morris Messenger,

and Johnson & Johnson's Sad Shad, not to mention some slightly lesser known

figures, 7-Up SAM and $2 Joe.

And

Winnie.

Winnie

was Herman's first big success, and she's wholly owned by Herman.

Herman,

who is an honorary lifetime member of the WAC, invented his khakied pin-up

shortly after he was drafted in 1943 and posted to Aberdeen Proving Grounds in

Maryland for basic training. Herman had already established himself in

advertising and as a freelance cartoonist, and his superiors encouraged him to

continue in the latter endeavor during his putative free time. He did so,

attracting the attention of the editor of the base newspaper, The Flaming

Bomb. And when the editor interviewed Herman, he ended by asking the

cartoonist to invent a character for the paper.

Winnie

was the result. She was an immediate success, particularly among WACs.

"She made us laugh at ourselves," said Lita Bowman, a San Diego WAC

and WWII veteran. "She did what we did, saw the world the way we did, and

she was our hero."

Says

Herman: "I was frequently asked how I, being a man, could depict women so

well. I was lucky: I was one of the only men allowed into the women's

barracks." And into their mess hall and other behind-the-scenes locales

where he saw WACs in action and distilled from what he saw the gags that

animated Winnie.

Within

weeks, Winnie the WAC was being distributed to base newspapers worldwide

by the Army's Camp Newspaper Service (CNS), a clipsheet that included Milton

Caniff's Male Call, Leonard Samsone's The Wolf and cartoons by

Herblock. Appearing in 1,200 base papers, Winnie was an asset to be

exploited.

The

Army sponsored a Winnie look-alike contest and picked WAC Pfc Althea Semanchik,

and she and Herman went on highly publicized public relations trips to recruit

women for the WAC. In 1945, the Army Ordnance Department voted Winnie

"Ordnance Joe of 1945," an honor usually reserved for a male (and a

live one at that), Life magazine ran a three-page spread on Winnie in

the March 19, 1945 issue, and later that year, Herman published a collection of

Winnie cartoons. The book, a slender volume, sold for a buck, 50,000 copies

worth.

All

of a sudden, Herman was a famous cartoonist. But he didn't set out to be a

cartoonist.

A

man of many parts, as I've noted, Herman has two distinct artistic facets—a

realistic side and a cartooning side. And he was able to capitalize on both,

due, probably, to a talent for showmanship—a talent fostered by his earliest

experiences, which were in show business.

Although

he was born in Fall River, Massachusetts (May 12, 1919), Herman grew up in

Hollywood. His father, who was playing violin for Paul Whiteman when Herman

was born, moved his family to Los Angeles in 1921 to take a job with Fox

Studios, playing in the orchestra that supplied mood music for silent films.

The Hermans took a house on Beechwood Drive, just under the sign on the hill

overlooking the city that advertised the housing development in the vicinity—"Hollywoodland."

Herman

attended Cheremoya School, and since many of his classmates there and through

junior high school were Mexican-American, he acquired conversational Spanish

and learned to appreciate the culture of his fellow students. And like most

embryo cartoonists, he drew pictures.

"I

never thought in the beginning that I'd be a cartoonist," he told me when

I visited him in December 1993. "I was interested in drawing, but I wanted

to capture what I saw realistically. And my realistic side shows the Spanish

influence. I don't do cartoons on Mexico and Spain. That's pretty

serious."

Herman's

father, eager to advance his son's various aspirations, arranged for the boy to

have the run of Fox Studios. Young Vic learned about casting, characters,

scripts, costumes, color, camera angles and distance, timing, staging, and so

on. Watching movies being made, he gained some understanding of the ways

visual, literary, and musical elements could be combined into a unified whole.

When

Herman was about eleven, his mother, also an artist, helped him to an

apprenticeship with the Yale Puppeteers, a marionette team then producing shows

at the Teatro del Toro (Theater of the Bull) on Olvera Street in the Mexican

district of Los Angeles.

Herman’s

parents divorced in 1931, and in 1933, Herman and his mother moved to Bayonne,

New Jersey, to live with her parents. By this time, Vic, fourteen years old,

was an accomplished puppeteer, managing a repertory cast of 35 puppets, which

he had made himself out of wood with wires for joints. He staged puppet shows

in "El Teatro Pequeno" (The Little Theater), the basement of his

grandparents' home. He produced four shows: Pinocchio, Treasure Island,

Cinderella, and Uncle Tom's Shack ("shack" rather than

"cabin" to avoid payment of royalties; entrepreneurial cunning came

early).

A

fifth show was a Hollywood revue, with a variety of entertainment-world

characters—a talking monkey, a dragon that belched fire, and a Pagliacci clown

(crying on the inside while laughing on the outside), a boop-boop-a-doop girl,

a trained dog (reminiscent of Rin Tin Tin), one of the dwarfs from Rip Van

Winkle, and so on.

Herman

gave performances at Bayonne Free Library, and, while a mere teenager, lectured

at Columbia University before a class of students and professors of puppetry.

At

Bayonne High School, Vic was editor of the school paper, The Beacon, the

staff of which grew to sixty while his senior year. He also drew decorative

pictures and column headings, his first cartoons. And he became a crusading

cartoonist/editor/journalist.

The

school’s population was increasing in size so rapidly that the principal asked

Herman to do a cartoon requesting President Franklin D. Roosevelt to enlarge

the school for its growing student body. Hermand did a cartoon showing FDR

putting into the hands of Principal Daniel P. Sweeney a new and larger school.

Subsequently,

Roosevelt wrote Sweeney, promising to do something to improve the school

building and saying that Mrs. Roosevelt would visit the school to obtain the

original art for the cartoon. Herman has been told that the original hangs in

the Roosevelt Collection in Hyde Park, New York.

After

graduating from high school in 1937, Herman went to work in the art department

of Warner Brothers East in New York City where ads, posters and billboards for

the studio's movies were made. (Among his assignments, the background figures

on the Bogart-Bergman “Casablanca” poster.) Evenings, he attended classes at

the Art Students League, studying under renowned George Bridgman. Living now in

Greenwich Village, he also took courses at the Commercial Illustrators School

in the Flatiron Building in New York.

Herman's

next stop was with the advertising agency Denker, Johnson, and Fleck, where he

specialized in figure drawings made in pen and ink, scratchboard, and brush and

ink wash. After two years, he left for a position with the prestigious Young

and Rubicam ad agency. There, he met Elsie the Cow.

Elsie

had been a symbol for Borden for years, but she had always appeared as a real

cow. Now, Borden wanted Elsie to have more personality. The assignment was

given to Herman and other freelance cartoonists who had been working on the

Elsie account.

"When

I started working on Elsie," Herman said, "she was on all fours. And

then we stood her up. When we stood her up, we had to figure out how to cover

her up. But that's an udder story," he quipped, savoring the bad pun that

he delighted in repeating whenever he told this story.

They

put an apron on Elsie, and the cow and her family became characters in

page-long illustrated dramas—comic strips. They

put an apron on Elsie, and the cow and her family became characters in

page-long illustrated dramas—comic strips.

While

working at Young and Rubicam, Herman also freelanced cartoons to magazines. He

sold his first one to the venerable humor magazine Judge in 1940. After

that, he sold to all the big glossy weeklies— Saturday Evening Post,

Collier's, Liberty, as well as Esquire and others. Then in 1943, he

was drafted into the Army.

After

completing basic training at Aberdeen, Herman was assigned to the Army's Motors magazine as a field artist correspondent. His experience making on-the-spot

sketches would come in handy in one of his later careers, as we shall see. He

also drew posters, one of which showed a soldier sitting on a toilet with the

caption: "My Censored Is Moist—Raise Toilet Seats!" It was posted in

Army latrines around the world.

But

his most celebrated accomplishment during the war years was the creation of

Winnie the WAC. Before the war's end, Winnie was translated into a movie with

the luscious Carole Landis in the title role. (Herman had script approval but

wasn't much involved in the production; oddly, the Wikipedia entry for Landis

fails to list this movie as one in which she appeared.)

At

the height of their fame, Herman and Winnie were given a mini-parade on New

York’s Fifth Avenue that terminated on the steps of City Hall where they were

met by Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia.

Winnie

retired after the War but returned to active duty during the Korean War

(1950-52) and again during the Vietnam conflict (starting in 1966). For both

these morale-boasting efforts, Herman volunteered his creation in the form of

reprinted cartoons, up-dated from their original publication in the 1940s. And

she came back twice more on less belligerent occasions: the USO drafted her in

1954 for the United Defense Fund drives; and in 1985, Winnie helped the U.S.

Treasury Department sell savings bonds.

Briefly

in 1991, it seemed possible that Winnie would return for the war in the Persian

Gulf. “I hope not,” Herman said at the time, “—because I don’t want this

conflict to become another Korea or Vietnam. But if things do go bad over

there, I wouldn’t mind bringing her back to pep up moral among the troops.”

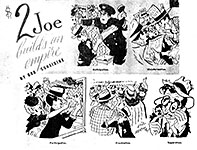

IN 1946,

HERMAN RETURNED to civilian life, trumpets blaring. Now celebrated as Winnie's

creator, he cranked out a cartoon brochure with a self-caricature on it to

announce his availability for any and all assignments. William Randolph Hearst

saw the brochure and thought Herman’s face on it was too funny to lose. He

commissioned Herman to illustrate Bob Considine's column, and when Considine

wrote about the race track, Herman's pictures featured a self-caricature dubbed

$2 Joe, who usually lost his wagers. (It was, perhaps, prophetic, as we shall

see anon.)

Herman

freelanced magazine cartoons to all the big markets (in order to hit them all,

his wife Miriam often made part of the weekly “look day” rounds every Wednesday

for him), and he did advertising cartoons.

One

day, a young fellow knocked on his studio door and volunteered to do cartoon

roughs for him; it was Mel Lazarus. Lazarus left after six months or

so, and a few months later, he phoned Herman. Lazarus was now art director of

Toby Press, the company owned by Al Capp and his brother Eliot Caplin.

And Lazarus offered Herman an assignment drawing himself in a 16-page Li'l

Abner comic book that would be used to recruit for the Navy. Herman’s

self-caricature’s name was Drawing Board McEasel. (When I interviewed Herman,

he got a chuckle out of the notion of the creator of the WAC heroine doing

recruiting for the Navy.)

By

1948, the advertising side of the operation had become so lucrative that he

formed his own cartoon advertising production company, Vic Herman Productions,

Inc. The company made television commercials, too. (Hal Holbrook once worked

in a Herman production.)

Among

Herman's clients were Western Electric, Philip Morris, Johnson & Johnson,

and 7-Up. Through them, Herman met Reddy Kilowatt, Johnny the Messenger, Sad

Shad, and 7-Up SAM and others not quite so well-known.

"I

did Reddy Kilowatt on and off for about twelve years," Herman recalled

when I interviewed him. "About the same length of time I did Elsie. I

didn't create either one of them, but Johnny was partly my creation. They had

been using just the head of the character, and when I came into it, I dressed

him up and used him at his full height."

Sad

Shad was a character Herman created to promote the clean-up of New Jersey

riverways. And he created 7-Up SAM to help 7-Up salesmen.

The

7-Up people came to Herman in 1956. The assignment was to create a dramatic

and interesting visual training program that would convey timely sales

instruction messages to 7-Up salesmen every month. The vehicle they selected

was an illustrated pamphlet, a comic book. Working with 7-Up marketing vice

president Bill Winter, Herman first devised the name of the character: SAM,

which stands for Selling, Advertising, and Merchandising.

Every

month, SAM would appear in a short story that presented a sales message geared

to current nation-wide 7-Up promotional efforts. The story format was

crucial: SAM would never preach; he would show through his own

actions how to increase sales.

Once

the magazine was launched, Herman worked with 7-Up sales training director Bob

Britton. They met monthly in St. Louis to coordinate SAM's activities,

preparing stories for the publication three months in the future. During one

such meeting, they might rough out a script for the next issue, prepare a

synopsis of SAM's activity for the following month, and begin discussing themes

for the issue after that. Actual scripting was done in Herman's New York

studio, as was the artwork.

But

Herman wasn't content to take ideas from the company's home office sales

force. He researched his subject by traveling back and forth across the

country, attending 7-Up schools, training seminars, regional meetings. In this

manner, he made certain that 7-Up SAM was fully aware of the problems and

challenges faced by his readers. Before producing the first issue (September

1956), Herman spent six months in the field, working routes with 7-Up salesmen.

"It

went over very well," Herman said. "I did 7-Up SAM magazine every

month, for seventeen years."

"How

do you come up with all these characters?" I asked.

"Think,"

Herman said. "I think."

By

way of example, he related the creation of Winnie, short and sweet:

"They

gave me a week to come up with the character. I wandered around the area to

see what was there, and I found out Aberdeen had the largest contingent of WACs

in the U.S. Army. It was obvious. So I came up with Winnie the WAC."

"So

you came up with Winnie because there were all these WACs on the base?" I

said.

"Right."

"And

there were already plenty of male cartoon soldiers," I continued.

"Mauldin's Willie and Joe, George Baker's Sad Sack, Dave Breger's Private

Breger, Dick Wingert's Hubert. But no women characters. No WACs. Until

Winnie."

"Right,"

Herman said.

Writing

the Foreword to the Winnie the WAC book, starlet Carol Landis revealed

some of the production hurdles Herman encountered (relying, no doubt, on what

Herman had told her: “The first Winnie cartoons were drawn while Vic was out on

a five-day bivouac. Others were sketched from a hospital bed while Vic

recovered from the baleful effects of a ptomaine attack. Still others first saw

the light of day on Saturday night train rides from Aberdeen to New York. And

some where even drawn quietly and calmly at Vic’s desk in the Ordnance School,

where he spends his days assisting in the preparation of training aids for

Ordnance soldiers.”

Herman

donned khaki once more in 1965. The National Cartoonists Society staged a

dinner and gala in honor of wartime cartoonists called “War Cartoonists Nite,” and

Herman was asked to make all the arrangements. It took him six months to put

it all together.

Written,

produced and directed by Herman, the event took place September 22 at the Hotel

Astor. Over 500 guests attended the dinner and the USO show afterward. The

chief attraction of the evening was a film produced by Herman that depicted the

efforts of over 125 wartime cartoonists culled from fifty years of soldiering

comics features. Guests of honor included General Omar Bradley, Walter

Cronkite, Fred Waring, and John Daly.

Herman

chuckled, recalling the evening: "I got Hugh Hefner to loan us twenty

Playboy bunnies from the New York Playboy Club to act as hostesses. Hef said,

‘I'm giving you twenty bunnies for one night. And Vic,’ he said, ‘that's one

night only.’"

Herman

grinned, looking not just a little like Esky, the familiar moustached roue that Esquire deployed as its mascot for years.

Actually,

Herman has been mistaken for Walter Cronkite more often than Esky.

He

told me about an incident that took place in the famed Pen and Pencil

restaurant where cartoonists usually convened for lunch midway through

Wednesday’s peddling day at magazine editors’ offices.

“One

Wednesday,” Herman said, “I’m eating lunch and I was delighted when a young lady

came up to me and pushed a note pad in front of me, saying, ‘May I have your

autograph?’ I was overwhelmed,” he continued. “I asked for her name and she

gave it to me, and I then wrote out a note to her thanking her for following me

in my artwork.

“Well,

she looked at my note and then at me and then again at the note and again at

me. Then she shoved the signed notepaper back to me and said, angrily: ‘I

thought you were Walter Cronkite.’”

For

his work on “War Cartoonists Nite,” Herman was presented with the NCS Award of

Honor.

IN 1960,

HERMAN TOOK AN ASSIGNMENT with Gourmet magazine, which sent him south of

the border to draw and paint the people and places of Mexico.

"That

was it—the turning point of my career," Herman said. "I went back to

Mexico, the old affection was rekindled and I was hooked for good. Ever since,

almost everything I've done has had a south of the border theme."

Parents

Publications commissioned him to write and illustrate children's books in its

Hispanic Southwest series, and Herman went back to Mexico again to research his

material, making sketches and paintings. The Mexican government took note of

the authenticity of his paintings and in 1961 began sponsoring exhibitions of

his work in the U.S. and Mexico. His one-man show, "The Many Faces of

Mexico," has traveled all over both countries. In 1967-68, it was mounted

twenty-one times in the two countries.

But

Herman's paintings are not merely mug shots. The paintings tell stories.

Simple but revealing tales. Without any kind of verbal caption, a painting may

say, "This is a Tarascan woman selling jicamas." Or, "This

youngster fishing with a net in the Boca del Rio Lagoon [in Veracruz] is an

apprentice in the commercial fishing trade."

His

work has earned the highest accolades—praise from many on both sides of the

border.

Said

Joaquin Touz Lo, noted art critic for La Nacion, Veracruz's leading

newspaper: "We were greatly surprised to see true Mexican art of this

form by an American artist. We found ourselves face to face with a fresh, new

realistic approach to painting. These are truly sensitive works, as gratifying

to the eyes as to the soul. These are the works of a many who has captured the

true feelings of Mexico today; the happiness and poetry of its people and has

felt the need of conveying his impressions with masterful strokes of the brush

into a `pictorial diary' of our daily lives so that others can share

them."

John

Brown, cultural affairs officer of the U.S. Embassy in Mexico City: "Vic

Herman has a special fondness for the Mexican people and he knows them

well."

Perhaps

the ultimate compliment, from Father Benjamin Fernandez Valenzuela of Morelia,

Michoacan: "Senior Herman paints with the hand of an American and the

heart of a Mexican."

Said

Herman: "If the many peoples of Mexico, when seeing my exhibitions,

accept my paintings as authentic in telling the story of their daily lives, and

if the peoples of the United States understand the dignity, culture and arts of

the Mexican peoples, I feel that I will have fulfilled the purpose of my

activities—that is, helping to cement the friendship between our two

countries."

Dubbed

"Ambassador with a Brush" by American Artist magazine, Herman

has spent months in Mexico over the years, prowling the country in his station

wagon searching for subjects. Typically, once he found one, he would begin

with a pencil sketch to capture the subject's likeness, sometimes with the

subject's knowledge; sometimes not. Next, he made several thumbnail sketches

to indicate the composition or pattern of the entire final picture. Sometimes

he worked with the model for a couple of days.

To

record the colors, he took color slides. When feasible, he actually bought the

clothing his subject was wearing—sombrero, shoes, rebozo (shawl), serape,

skirt, whatever— and sometimes other articles that would be pictured. With

these items at hand to guide him in the final painting, he gave the work

authentic texture as well as color. All these accouterments were tagged and

packed away in his station wagon for his return trip to the U.S. On one

occasion, an entire ox cart was dismantled and brought home in this fashion.

Back

in his studio, Herman often used a professional model to recreate his subject,

and, using the sketches and notes he collected in the field, he completed the

painting. When he was actively painting, a typical day began at 5 a.m. He

sometimes worked for a month on a single painting.

Herman

has published over 50 children's books as a result of his Parents Publications

assignment. Determined not to do the "Myrtle the Turtle" kind of

kids' book, Herman sought to depict the lives of Mexican people as

authentically as possible. And that meant research. Juanito's Railroad in

the Sky (Golden Press, 1976) is a good example.

Aimed

at ages 7-11, Juanito tells the story of a young Mexican boy's first big

test in life. When he's riding in the locomotive with his father, an engineer

on the famed Los Mochis to Chihuahua line, his father is suddenly beset by such

troubles as running out of fuel, dealing with difficult passengers, and even

life-threatening dangers. Juanito must help out and cope on his own. And he

does.

Passionate

about details and accuracy, Herman spent three years researching the visuals

for the book. He made over 20 trips to Mexico, riding horseback down over

treacherous trails into canyon regions, and even strapped himself to the

cowcatcher of a train for the 75-mile run between Los Mochis and Chihuahua to

take photographs of the terrain so his illustrations would be authentic.

"I

go where the action is," Herman said. "That's the way I covered

stories when I was a war correspondent, and that's the way I write my

books."

Another

time, while researching a book about fishing, Herman waded chest-deep into the

ocean to photograph men hauling in their nets. Suddenly, he heard people on

the shore screaming, and before he knew it, a shark sped by him, tearing at his

arm.

Juanito received a special award in graphic competition. And because of its

sensitivity and touching commentary with scenes of everyday life, it was

designated as an "Official Bicentennial Event" by its publishers, who

printed an unprecedented 75,000 copies in the first printing.

In

1968, Herman left New York and moved to southern California to be closer to the

Mexican heritage he loved. He kept the 7-Up account until 1974 and some of the

other accounts "until they wore out.” Others never wore out and were kept going

by the clients for years. By the end of the decade, Herman was wearing out,

too. "The traveling got me," he said. "I didn't retire, but I

was pushing sixty, and the traveling I did every month was incredible."

By

this time, he had clocked over 700,000 air miles working his accounts. And in

1977, his wife Miriam passed away.

DURING MY

VISIT, Herman took me and a couple mutual friends, Shel Dorf and A.R.

"Tommy" Thompson, on a tour of his Del Mar studio, which he had built

in 1970. A building entirely separate from the Herman Hacienda, the studio is

more like a second elegant home than a workshop. But it is thoroughly

functional.

The

walls of the studio's three large rooms are hung with Herman's drawings and

paintings, posters, and other memorabilia of his varied career, including

photographs of Herman with various celebrities, politicians and entertainers.

The largest room, half the building, with high cathedral ceiling and plenty of

windows, is the studio in which he paints. One tall wall is a pictorial museum

of Herman's career. Framed photos of Herman at various functions and

occasions, certificates, citations, awards, proclamations from presidents and

schools and associations.

At

the opposite end of the building is a sort of library with book shelves that go

from floor to ceiling—books on art, business, music, puppetry, writing,

journalism—and a desk. On one wall, a map of the North and South America is

studded with pins that identify the places Herman has been or is researching.

Then hidden away behind this room is the "workroom"—layout tables,

light tables, an enlarger, photoprocessing equipment, a bank of seven filing

cabinets filed with scrap, Herman's "morgue" of visual references.

In

every room, built-in cabinets store correspondence, records, mailing lists,

tools and working materials, publicity and public relations releases.

Altogether, a model of orderliness, a working studio that is also a small museum

of Herman's life and work.

Sadly,

when Herman died April 14, 1999, this picturesque personal monument and

workshop was his no longer.

Herman

loved playing the ponies. And once a year, he organized Cartoonists Day at the

Del Mar Racetrack. But he went there more often. Like $2 Joe, he’d placed too

many bets that didn’t pay off. He had to sell his property to pay his gambling

debts.

But

when I visited him in 1993, Herman was still adding to the trove in the files

and on the walls of his workshop/museum. Winnie the WAC was back, after all,

and there was work to be done. And Herman's wife Virginia was helping with the

work. She produced T-shirts and greeting cards featuring Winnie. Both the

Hermans are enthusiastic about Winnie's comeback—even though Ginny is an

ex-WAVE, a division of the Navy, “Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency

Service” (WAVES, a laboriously contrived acronym for the ocean-going branch of

the military).

Return to Harv's Hindsights |