CARTOONING THE ROARING TWENTIES

Part Three: January 1926 - December 19258

THE TWENTIES IN AMERICA ROARED WITH THE EXUBERANCE of a nation shaking off the fetters of the Victorian era, it roared with the defiance of the Young rebelling against the conventions of out-moded mores, it roared with the outrage of the Older Generation at the audacious behavior of their offspring, it roared with the sound of cash registers ringing up sales in celebration of the country's unprecedented prosperity. By 1926, the year the cartoons in this posting began appearing in print, the roar was deafening.

The

din of the endless all-night party the country seemed embarked on was

orchestrated by the flapper and the boot-legger, and it was augmented by

bathtub gin and other brands of illegal booze, by high-speed cars and hit men,

by the screaming headlines of tabloid newspapers that announced the fads and follies

of the moment to the waiting world, by frenzied speculation on Wall Street,

even by short skirts and bobbed hair and hip-flasks.  Contributing to this

outlandish cacophony was the clash of licentiousness and repression, of

scientific thought and religious fundamentalism, of self-indulgent Freudian

theory and self-righteous blue laws.

Contributing to this

outlandish cacophony was the clash of licentiousness and repression, of

scientific thought and religious fundamentalism, of self-indulgent Freudian

theory and self-righteous blue laws.

By 1926, the revolution in manners and morals that characterized the decade was more than a simple insurrection: it had escalated into a way of life for a substantial portion of the population, particularly the Younger Generation but by no means limited to it. Post-war disillusionment, Prohibition, the automobile, and movies and the lurid sex-and-confession magazines they spawned— together, they were a juggernaut of influence on social mores that bulldozed aside the old and often comfortable ways of thinking and behaving. In their place for awhile was nothing but unparalleled economic well-being and an overweening desire to enjoy the life that affluence enhanced. No longer merely rebellious, the Young had found a kind of affirmation for their style of living in the notions of the new age.

Popularized versions of the scientific theories of biologists and anthropologists had convinced the Young that men and women were only animals after all and that moral codes were scarcely universal among mankind and, indeed, were often little more than the petrified remains of odd tribal superstitions. Infiltrating this intellectual encampment, the Freudian gospel found willing adherents.

Sex, it seemed, was at the root of all human behavior. The unconscious desire to gratify the sexual impulses of the libido explained everything everyone did. The noblest endeavors— even the ascetic life of the monk on the mountain top— could be seen as sublimated sex drive. To achieve mental health, one must strive for an uninhibited sex life. For happiness and well being, one need only obey his/her libido.

While these attitudes led to new sexual freedom, they had even broader implications. Sex was but the organizing principle of the libido's drive for gratification: around the fringes, there were dozens of other manifestations of the same impulse, dozens of other gratifications to be satisfied. And so a self-indulgent pursuit of pleasure in many forms animated the social life of the age. Having bread in abundance, the Young looked for circuses. Everyone was out for a good time.

To a generation of parents, the behavior of American youth was scandalous. In adopting the cynicism of the times, the Young acquired a patina of sophistication under which they were alarmingly careless of custom, convention, and even law (although parents, too, evaded both the spirit and the letter of Prohibition laws).

The enclosed automobile gave them freedom to indulge every youthful whim and urge: at the merest pop of a cork, they were likely to jump into their cars and dash off to night-long parties or to the nearest Lovers' Lane where they could park and neck and pet through the wee hours in the privacy of their vehicular boudoir. And they talked endlessly— with an insouciance that astonished and shocked— about bodily functions that most respectable people scarcely dared to think about.

And by 1926, the Young had thoroughly corrupted their elders: fathers and mothers had begun aping their sons and daughters. F. Scott Fitzgerald, the novelist of the age, analyzed the phenomenon: "The sequel was like a children's party taken over by the [grown-ups], leaving the children puzzled and rather neglected and rather taken aback. Their elders, tired of watching the carnival with ill-concealed envy, had discovered that young liquor will take the place of young blood, and with a whoop, the orgy began. The younger generation was starred no longer."

The Age of Flaming Youth had dawned and bathed the entire country in its glow, and so the nation became the Land of the Young (some of whom were Old)— with Edna St. Vincent Millay its poet laureate: "My candle burns at both ends; / It will not last the night; / But, ah, my foes, and oh, my friends, / It gives a lovely light."

And the Young looked around and found that Twentieth Century America had arrived at last. The age of mass production, mass consumption, standardization, national advertising, consumer economics, business enterprise, and mass communications and entertainment was upon us. Thanks to radio and the proliferation of national periodicals, the populace was united as it never had been before— united as a vast audience to which both performers and pitchmen played. And the twenties roared with the competition for the favors of that audience.

It was the Age of Ballyhoo, the Age of Excess. The new tabloid journalism shrieked even commonplace occurrences into torrid epochal events. The most commonplace of happenings were those involving sex or crime or (with luck) both.

The Hall-Mills murder trial, for instance, which grabbed headlines for weeks in the winter of 1926 when Jane Gibson, the Pig Woman, came forward with new testimony accusing the Reverend Hall's wife of murdering her husband and Eleanor Mills, the soloist in his choir with whom he was having an affair.

Then there was the attempt that fall on the life of one of Chicago's most notorious citizens: a deadly battalion in eight touring cars drove slowly by the Hawthorne Hotel in broad daylight and raked its lobby with machine-gun fire in the hope of killing their gangland rival, Al Capone. (They failed: Scarface hugged the floor and emerged unscathed. "What shooting?" he asked when the neighborhood cop came by.)

The next season's divertissement was furnished by the alleged kidnapping of Aime Semple McPherson, the virginal-looking evangelist whose mysterious disappearance was probably not a kidnapping at all but a sexual adventure. The tabloids played it big. The story, one writer subsequently claimed, was "a kind of compendium of all the pervading nonsense, cynicism, credulity, speakeasy wit, passion for debunkery, sex-craziness, and music-hall pornography of the times."

Not that all news was so frivolous. Some events were so monumental they required no inflation to make front page headlines scream. When an unknown mail pilot named Charles A. Lindbergh flew the Atlantic nonstop and alone in May 1927, he gave the country an authentic hero to worship. And that same year Henry Ford shut down his vast River Rouge plant for over six months to re-tool for the production of the first new model car to come off his fabled assembly line since the introduction of the Model T in 1908; the Model A was unveiled December 2, 1927.

On the political front, "Silent Cal" Coolidge, the taciturn Vermonter in the White House, provided very little copy for newshounds. But prospects brightened in 1928 when the Democrats picked the "happy warrior" Al Smith to oppose Herbert Hoover's candidacy for the Presidency. Smith, outspoken foe of Prohibition and the Ku Klux Klan, furnished lively news: a vicious whispering campaign alleged that if elected, Catholic Smith would have to let the Pope run the country.

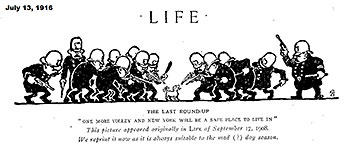

MEANWHILE, THE OLD HUMOR magazine Life mounted a Presidential campaign of its own, nominating Will Rogers to

head the "Anti-Bunk Party," the only party dedicated to the

elimination of Bunk from the political scene. (If successful, it was

acknowledged, this campaign would deprive all the other national parties of

"the sole excuse for their existence.") As soon as the polls closed, Life assiduously reported Rogers' election by the Great Silent Vote of the nation,

which went "unanimously" for Rogers, and the candidate was obliged to

carry out his only campaign promise: "If elected I absolutely and

positively agree to resign."

It

was the Era of Wonderful Nonsense. The Charleston swept the land in 1926,

joining the shimmy and the black bottom as exercises of choice on the dance

floor. The Miss America Pageant had become an institution since its

beginnings in Atlantic City in 1921, and it and other beauty contests made the

skin-tight one-piece bathing suit orthodox beachwear for ordinary female

citizens (not just for Mack Sennett's celluloid girls).

Hollywood continued to enthrall the nation with the antics of its denizens both on-screen and off. In 1926, Clara Bow rocketed into fame when she was proclaimed the It Girl— "It" being the same old sex appeal except that with Miss Bow and a generation of flappers who had discarded ankle-length skirts and high-button shoes and burlap underwear, more of "It" was showing (and a little more available), no longer a sin but a virtue.

|

|

|

And

in the canyons of Santa Monica, Tom Mix was shaping the Western into the

most durable of film genre: more than any of his cohorts, Mix established

the cowboy as knight errant, a clean-living, horse-loving stalwart for justice

and fair play.

And then in October 1927, Al Jolson talked as well as sang in The Jazz Singer, and a new era in Tinseltown was born: "flickers" were replaced by "talkies."

Elsewhere, John Barleycorn was winning the fight, much to the consternation of the blue noses. In 1927, it was estimated that there were more speakeasies in New York than there had been saloons before Prohibition. And New York's lively nightlife had been made even livelier with the 1926 election of the perfect Jazz Age politician as mayor. Saying no civilized man would go to bed the same day he woke up, debonair and fun-loving Jimmy Walker became the city's Night Mayor, touring the night clubs until all hours. With New York setting the pace, the pressure for moderating the prohibition of the 18th Amendment mounted as the decade drew to a close.

|

|

If our national life had become a circus by the middle of the 1920s, clowns surely had a prominent part to play in that life. And cartoonists, who committed their hilarities with pen and ink rather than slapstick and grease paint, seemed to have proliferated accordingly if we are to judge from the 1926-28 issues of the old Life from which I culled the cartoons on display hereabouts. And the work of two of the cartoonists of this period virtually defined the Jazz Age: John Held, Jr. and Russell Patterson.

Held's cartoons embodied the fads and frolics of the Younger Generation, particularly college youth (as I said in an earlier Twenties posting). And Patterson's pen captured the spirit of the fashionable and the sophisticated.

|

|

Technically, the work of the two men has a surface similarity: Patterson, like Held, contrasted stark solid blacks against a fine penline. But Patterson's line seems sketchier than Held's, and its wispy languor lends his pictures an airy, breezy informality in comparison to Held's studied geometric anatomy. And Patterson's almond-eyed girls are gorgeous. Patterson was a painter as well as a cartoonist, and his girls are more realistically rendered than Held's.

Held's girls are expressionistically caricatured versions of femininity; Patterson's girls are idealized visions, lithe and leggy. Held's girls are comedic emblems; Patterson's, statuesque illustrations. Held's girls are jazz age improvisations; Patterson's, symphonic orchestrations. Held's flappers are all legs and bony knees; Patterson's, long-stemmed and sveltely curvaceous, with torsos that are architectural triumphs.

|

|

That Patterson's drawings of women were built upon a sound structural knowledge is not surprising: he had begun his artistic career by studying architecture. Patterson's other artistic training was mostly catch-as-catch-can. Living in Chicago after the Word War I, he started designing interiors. Then he visited art classes at the Chicago Art Institute and soon yearned to draw people instead of buildings. So in 1920, he went to Paris and spent about a year hobnobbing with such artists as Paul Signac, Gilbert White, the Pissaro brothers, and Claude Monet. And he went to life drawing classes.

"Paris is cold from November to May,” Patterson wrote years later, “—so whenever I had a franc, I went to the only place I knew where I could get warm— a life class.” (Because the models were naked, the room had to be well-heated.)

Patterson continued:

"My favorite was close by in the Latin Quarter. It was built like a very small theater in the round. The model's platform was in the middle of the room with a pot-bellied stove on it plus a chair. There was no dressing room so the model stripped and dressed in full view. These girls were beautiful and usually made a big thing of the strip. When special models were there, you had to make it early to get a seat. The favorite was a beautiful brunette. She liked ribbons and so did the men. Her bra was tied with a ribbon in the back, her lace panties were tied on the sides. A lace band around her waist had long ribbons. These she put through loops she had on her stockings. She took her time undressing and dressing and responded shyly to the applause. From two in the afternoon until six, the girls went from one-minute poses to fifteen minutes. I learned to draw the figure."

|

|

|

When Patterson returned to Chicago, he continued for awhile drawing interiors for furniture companies, and he sold paintings. But he was mildly discontented, haunted by the recollection of the pleasant days spent drawing nudes in Paris.

At last, inspired by the flappers he saw all around him, he began putting fetching versions of them into his interiors. He soon lost his furniture accounts, but he found other outlets.

A week before Christmas in 1925, Patterson went to New York and the big time. Shortly after the first of the year, he was drawing his girls in color to adorn ads for Rolls Royce and Buick and doing color covers for William Randolph Hearst's Sunday American, alternating with Held and Nell Brinkley. He was making $2,000 a week and living the high life in the big city.

One day he and a friend were having lunch in the Madison Hotel diningroom when a dignified-looking older man with a high collar an impressive forehead walked over to their table and stuck out his hand.

"You're Russell Patterson," the man said, "and I'm Charles Dana Gibson. I've been trying to meet you for months to tell you I'm crazy about those little girls of yours."

And so the mantle passed from the delineator of one generation's ideal of feminine beauty to the maker of the next's iconography. Gibson was President (publisher) of Life, and in mid-1926, Patterson's girls began to adorn the magazine's covers and to parade through its pages. These girls were to the last years of the 1920s what Gibson's had been to the 1890s. And Patterson's set a standard for the illustrators and cartoonists of the era, influencing not only their endeavors but the perception of fashionable beauty by the public at large and by women's clothes designers, too.

IN SELECTING CARTOONS for this, the last in our Roaring Twenties series, I tried, as before, to find cartoons that convey a sense of the times. Again I confined my search to the pages of the old Life (simply because bound volumes of the magazine were more readily available than any other source). And I attempted to use at least one cartoon by every well-known cartoonist whose work appeared in the magazine from 1926 through 1928. But I also surrendered at nearly every opportunity to the impulse to choose drawings that I liked. And the drawings in combination with their captions had to be funny.

I wasn't always successful in achieving all these objectives. Sometimes a Life cartoonist's work doesn't appear here because the cartoonist was abundantly represented in a previous posting covering other years (John Held, Jr., for instance, appears frequently in Part Two of this expedition), and I wanted to make room here for newcomers. Sometimes a cartoon does not meet all the criteria: a cartoon that is particularly representative of a given cartoonist's graphic style, for instance, might not be uproariously funny. But the work of one cartoonist in particular consistently met all the criteria in nearly every instance.

Fred G. Cooper is undoubtedly one of the great unrecognized graphic technicians and comic geniuses of the day. His work is always witty and crisply drawn, and he is often incisively topical. More amazing than this, however, is the enormous range of the man's graphic styles, each deployed with assurance and panache.

|

|

Born in McMinnville, Oregon, Cooper came to New York in 1904 at the age of 21 after a brief sojourn in San Francisco. His work began immediately appearing in Life and other publications of the day, but his principal income was derived from advertising design. He created the Edison Man trade mark for Consolidated Edison, and his work for that company won him a gold medal for best industrial advertising at the World's Fair in Milan in 1906. He served as the Collier's cartoonist from 1910 to 1920 and as an editor for Life.

Cooper was most renowned among his colleagues for his lettering, and his contributions to Life were frequently page-long poems, hand-lettered and artfully decorated with whimsical apostrophes that illuminated other aspects of his subject. He also decorated the editorials in the magazine and was an accomplished caricaturist (as witness his version of Will Rogers that we saw earlier), signed, as all Cooper's work was, with a monogram of his initials— a monogram that sometimes sprouted arms and legs the better to cut capers in the corners of his work. And he was one of the half-dozen cartoonists whose work regularly appeared on the magazine's covers.

|

|

|

|

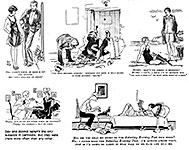

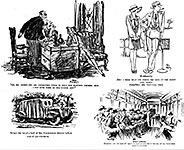

Cooper was an authentic virtuoso whose drawings were always brilliantly conceived and masterfully executed in a pyrotechnical display of visual effects astonishing in the variety of their styling. And he is distinguished by an unequaled achievement: every cartoon in the February 28, 1928 issue of Life is drawn by Cooper. It is the only time I’m aware of that a national magazine published in a single issue the cartoons of only one cartoonist.

The cartoons, as you can see nearby, feature the vaudevillian horseplay of a pair of deadpan look-alike performers, one the straight man who delivered the setup for the gag; the other, the funnyman who delivered the laugh lines—in Cooper’s case, an unending series of groaners, bad puns and off-sides word play.

|

|

|

|

Another cartoonist whom the history of the medium has mostly overlooked is J. Norman Lynd. While not as profuse a technician as Cooper, Lynd wielded his pen impressively, adapting the shading techniques of the previous decade to a simpler contemporary style, with lines so assertively delineated as to give his work an aspect of contrast the equivalent of stark solid blacks.

The cartoons of the period tend to be drawn more boldly than the cartoons of earlier times— simpler linework, more use of solid blacks. And the technologies of printing had advanced enough to permit extensive use of wash drawings, so the pages of Life were vibrant with black and white and many tones of gray.

Typical of the time is the work of Garret Price and Don Herold. Price is another of the craftsmen of the period whose work has never received adequate notice.

|

|

As brilliant in his use of blacks and grays and fragile line as Patterson and Held, Price was often featured on the cover of Life, too. In contrast to Price's realism is Herold's geometric abstractionism.

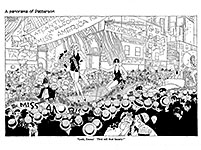

But the illustrative manner of the previous decades was scarcely dead. Gibson's work still appeared regularly in Life, and so did that of J. Conacher, Reginald Birch, and R.V. Culter, the latter having launched a nostalgic series that presented fondly remembered aspects of city life in "The Gay Nineties." In a class by himself is W.G. "Jack" Farr, whose architectural vistas always dwarfed his characters and their antics.

The modern single-speaker caption cartoon did not as yet have the field exclusively to itself. Many of the cartoons published in Life during this period are still of the antique "He-She" type (multiple-speaker caption) in which the pictures merely provide a visual setting for dialogue, and the humor arises entirely from the verbal exchange. But the single-caption cartoon was clearly on the ascent, and if its verbal-visual blending was not yet the rule, visual puns were frequent, signaling a growing awareness that the pictures and the captions ought to be mutually dependent, that when the sense of one arises from comprehending the meaning of the other and vice versa, the comedy that results is better because it is more surprising.

There are doubtless proportionally more cartoons of this kind on these pages than in my source because I tended to select these over the purely verbal gags, but the single-caption cartoon that gets its laugh with words and pictures in tandem was by no means a rarity in the years 1926-28.

AMONG THE CARTOONISTS who did magazine cartoons in the twenties were many who made their names later in other cartooning genre. Some went on to do comic strips in newspapers: Gus Edson did a number of undistinguished strips before inheriting Sidney Smith's The Gumps at Smith's death in 1935; Carl Anderson did Henry (1934); Harry Haenigsen, Penny (1943). George Storm was doing Phil Hardy (November 1925-September 1926) and Bobby Thatcher (starting in May 1927) contemporaneously with the cartoons herein, and Edwina Dumm was doing Cap Stubbs and Tippie, which she launched in 1918.

George Lichtenstein ("Litchty") started Grin and Bear It in 1932; but at the time his cartoons appeared in the 1928 Life, he was still in college (at the University of Michigan, where he was editor of the humor magazine, the Gargoyle). C.H. Sykes did political cartooning for one of the Philadelphia papers and contributed a juicy wash cartoon to Life every week.

Others were more known as illustrators: James Montgomery Flagg, Harrison Cady (who also drew "Peter Rabbit" for the Sunday funnies for three decades), and Ross Santee and Will James, cowboy artist/writers just beginning to make their splashes. Johnny Gruelle had launched his Raggedy Ann books over a decade earlier; his son Worth dabbled in his father's tradition, too, doing both cartoons and book illustrations.

Also appearing in Life were two cartoonists whose fame had been established during World War I as soldier-cartoonists: Bruce Bairnsfather, who went into the trenches with the first contingent of the British Expeditionary Force and subsequently immortalized three Tommies in his cartoons (Old Bill, Bert, and Alf); and, more well-known to Americans, A.A. Walgren, whose cartoons for the Stars and Stripes immortalized "Wally."

Some of the cartoonists herein became better known later for their work for other magazines. Paul Webb did a cartoon about hillbillies for nearly every issue of Esquire after that magazine started in 1933; Marge Henderson eventually created Little Lulu for the Saturday Evening Post and made a residual fortune on facial tissue (her story and that of Anderson and Henry can be found in Harv’s Hindsight for January 2010); Peter Arno drew the Whoops Girls for Harold Ross's The New Yorker and then carved his niche with the simplest style and boldest line in cartooning (for details, see Hindsight for June 2015); Gluyas Williams continued his anatomizing of mankind's pretentions and preoccupations in simple outline and sturdy black solid in magazines and in Robert Benchley's books (see Hindsight for December 2016 for the Gluyas Williams story.)

We close the ensuing exhibit of Life cartoons with Thomas Starling Sullivant's last published cartoon. A giant in American cartooning whose work had appeared in Life and other magazines for 35 years, Sullivant is at last receiving the notice and appreciation he deserves in a forthcoming book published by Fantagraphics, Excruciatingly Funny: The Antic Cartoons of T.S. Sullivant (for which I have supplied the Introduction—and the cartoons, which I diligently photocopied from the pages of Life).

Sullivant died August 7, 1926,* his passing marked with a reverent poem by Life editor (and fellow cartoonist) Oliver Herford (who had been associated with the maga-zine since its beginning in 1883). Herford catalogued the animals whose antics Sullivant had employed to ridicule human foibles, saying, "He held the convex mirror up to Truth / And captured her with laughter."

And so, in their own fashion, did other Life cartoonists, an array of whose cartoons we exhibit herewith—:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fitnoot. The foregoing essay was originally written as the Introduction to the third volume of Cartoons of the Roaring Twenties. Fantagraphics published the first two volumes but then, when they didn’t sell well, never got around to the third. But here at Rancid Raves, we always get around to the third—even if it’s taken a couple of months (as it has). So here it is, with lots of illuminating pictures.

* Some seemingly official sources say Sullivant died on the 8th, but I’m relying upon the New York Times obituary, published August 9 but dated August 8, which says Sullivant died “last night”—i.e., the 7th.