|

Getting Our Pornograph Fixed

A Fond Appreciation of Eight-Page

Dalliance So Long Ago Abandoned

The nice thing about Tijuana Bibles is that they are unequivocally pornographic. They aspire to nothing else. They do not beg for our indulgence by pretending to have some ulterior motive as socially redeeming educational tracts. There is no pretense about them. They are utterly unabashed. And that’s nice, as I said. So if you seek to define

pornography, seek no further: behold, this is it—Tijuana Bibles, the very

definition of the genre. If you ever see anything like them, you may be sure

it, too, is pornography.

It is refreshing to encounter

something unapologetically pornographic these days. So much of our cultural

detritus is equivocal about its own social standing. The debate rages

endlessly: what’s high art and what’s low art? As a culture, we have wrestled

with the issue of pornography entirely too much. We have become nearly obsessed

by it. Judging from the public prints, it is a daily intruder into our lives.

The papers are jammed with pornographic advertising for women’s lingerie. The

newsstands are overflowing with magazines whose covers flaunt pornography,

handsome virile men and beauteous women, who, together, radiate sex appeal.

Wallowing in it isn’t enough: we also want to know if we’ll be harmed by it. Is

it good or evil? Is it obscene? Should we care?

The confusion about pornography

began long ago--before, even, my time or yours. But the plain truth is that

pornography itself is not evil. If we take its meaning from the antique Greek

roots that form the word (porno = harlot + graphy = writing, drawing), we see

that pornography quite simply embraces writings and drawings that are about

sex. (Harlot’s prose, we assume, would not be entitled to a word of its own if

it weren’t about something harlots were more versed in than the average

citizen, and if their expertise is not in the sexual arena, where, then, is

it?)

In other words, there is nothing

inherent in pornography that is evil or obscene. Pornography and obscenity are

not synonymous. Pornography is something that can be objectively identified. If

it’s about sex, it’s pornography. Obscenity, on the other hand, is wholly a reflection

of personal taste. Something that is offensive to someone’s taste is often

described as “obscene.” The term, then, embraces virtually the entire range of

human experience not just sex. Photographs of piles of corpses in Nazi

concentration camps are, to me, obscene. A treatise that describes in

exhaustive detail the tortures of medieval Europe is, to me, obscene. If it

turns my stomach, if it’s revolting, it is, to me, obscene. Our confusion about pornography and

obscenity stems from the evolution of taste in our culture.

In ancient times, no one was

confused about it. Pornography was mostly enjoyed by those who could get it

(chiefly the well-to-do, admittedly); and sex was enjoyed by almost everyone.

Much pornography (like Lysistrata) was essentially humorous in character. It

was enjoyed because it displayed art or wit—inventiveness—in dealing

linguistically or graphically with humanity’s most popular subject—sex. (Sex is

popular, in case anyone should ever ask you, because it is centrally located.)

Then came the Middle Class. As

Medieval Europe evolved, the Middle Class emerged. And the Middle Class, it

soon developed, had social aspirations. It aspired to be better than it was.

Always. The story of the Middle Class is the story of upward mobility, ever

striving, ever seeking a higher social plane of existence, Goethe with a

vengeance. Aspiring to the gentility of the upper classes, the Middle Class

invented obscenity. It was entirely a matter of engineering a change in taste.

Anything that smacked too much of the vulgarity of the lower orders was deemed

inappropriate and was therefore earnestly eschewed. If they aspired to the

genteel ambiance of the higher classes, they would have to leave behind them

all the mementoes of their earlier, more sordid, existence nearer the bottom

rung of the social ladder. That, alas, included sex.

No, they didn’t actually expect to

abstain from sex altogether. They merely intended to avoid mentioning it. It

was vulgar and undignified. Any activity that required people to assume the

position of frogs was undignified. Life, they believed, would be much more

refined if they simply pretended that sex was not a part of it. And as long as

everyone kept their clothes on, they could maintain the pretense. The elegance

of their wardrobes gave the appearance of elegance to their lives. And so

nakedness was deemed obscene the better to banish it forever from the parlor.

Nakedness and sex. Sex was obscene. And therefore, so was pornography.

By the same token, if sex is not obscene,

neither is pornography. And perhaps that’s why we see so much of it around us

everyday. As a culture, we have progressed steadily in the direction of greater

reasonableness and individual freedom. That is the direction of Western

Civilization; ask anyone. In the course of this progression, several years ago

we decided quite reasonably that sex was actually a part of life. Sex, like

other aspects of the human condition, cannot be avoided so it may as well be

embraced. We embraced it. Suddenly, pornography was no longer obscene. It could

come out of hiding. And it did, albeit gradually. So now we find it on the

pages of the family newspaper, advertising women’s underwear, as I said, and in

magazines and on television, selling everything from automobiles to

refrigerators.

These developments are to be

encouraged. As long as pornography was underground, it was fairly crude stuff.

Once we get it entirely out into the open, presumably we’ll start to get some

pretty high class material—good writing, good drawing. In the old days—before

sexual liberation—we had to be content with clumsy excretions like Tijuana

Bibles.

These little eight-page sex comic

booklets (sometimes called “eight-pagers,” “bluesies,” or “jo-jo books”) began

appearing on the American scene in the late 1920s or early 1930s. Their debut

at about this time may have had something to do with the advent of cheap

printing methods. I saw my first eight-pager at about the age of nine or ten. A

friend showed me one on the playground of our school during recess. The

crudeness of the drawings was matched by the means of production: it was

printed by mimeograph. I was appalled at the pictures. What did it all mean? I

scarcely read the story. But I was fascinated despite my initial alarm.

I saw no more Tijuana Bibles in the

wild. And then about fifteen or twenty years ago some started appearing in

captivity—that is, in book compilations that began to show up in various sleazy

bookstores hither and yon. But whether or not I saw them being hawked furtively

on playgrounds or in poolhalls and saloons, they were there—“the kind men like”

(to invoke that joyfully memorable phrase).

Robert Gluckson in a paper presented

at the first Comic Art Conference in San Diego in 1992 suggests that the

production and distribution of eight-pagers was fairly extensive. Some students

of the genre say that over 2,000 different titles were published altogether.

One of Gluckson’s sources estimates that in 1939 alone, over 300 different

titles (mostly reprinting previously confected stories) were produced, totaling

three million copies. Other sources say twenty million copies were produced

yearly by the end of the decade. But we have almost no way of knowing how

accurate these estimates might be. The little booklets were drawn in attics,

printed in garages on hand-cranked machinery, and distributed surreptitiously

from the back pockets of shady vendors in alleyways and in dimly lighted rooms.

Since the traffic was wholly underground, no one was likely to keep records of

quantities.

The stories retailed in their flimsy

pages followed one of two formulae: in one, the principals have an exuberantly

successful sexual adventure; in the other, one or both of the actors fails

ignominiously. Typically, the first two pages set the scene, then pages three

through seven are enthusiastically devoted to depicting in action as explicitly

as possible the most ravenous sexual appetites in as uninhibited a manner as

imaginable, and page eight finishes with a comic punchline. In the better

examples, the punchline is a proper conclusion, a more-or-less logical outcome

of the preceding riot of raw sex; in less adept examples, the punchline has

little or nothing to do with the frenzied rutting that occupies the tumultuous

pages ahead of it.

Humor, however, well done or not, is

a vital ingredient in TJ bibles—as essential to the genre as daggers rigidly at

attention, sheaths oozing in anticipation, and meticulously detailed renderings

of their conjugation. In their comedic aspect, the eight-pagers join a long

tradition in erotic folklore. Much sexual material in most societies is

intended to be funny. The dirty joke is an ancient and enduring artifact.

Psychologically, jokes are acts of aggression by the teller; the object of the

joke teller’s hostility is the butt of the joke, or, more accurately, the

“thing laughed at.” The thing laughed at in most eight-pagers is inhibition

about sex.

It is, I think, an inhibition

peculiar to men. Most commentators on eight-pagers recognize that men are the

intended audience; the fantasies enacted are male fantasies more often than

not. (Perhaps, even, exclusively; not being female, I couldn’t say for sure.)

So why are men so intimidated by sex as to savor the ridicule of their

inhibitions? The answer, I submit, is biologically obvious: of the two sexes,

the male sex is the one that can fail to perform. And the threat of failure at

some moment of high emotion and equally elevated aspiration is what makes sex

inhibiting to men.

This simple biological fact, by the

way, is probably the key to the difference in character between men and women.

Men, as everyone knows, are more honest, more straightforward, than women. This

trait is biologically derived: it is impossible for men to fake sexual passion

(or lust, for that matter). If they are sexually aroused, any casual observer

can tell it. Women, on the other hand, can counterfeit passion with impunity:

no physical evidence will betray them. Hence, women can dissemble more

successfully than men: it’s a capacity for which their biology prepares them.

Men, however, are biologically prevented from disguising their true emotions in

this, the most fundamental of human encounters; and from this handicap, they

learn the folly of trying to dissemble at all. They are so incorrigibly forthright,

in fact, that none of them could ever undertake to sell a well-known bridge in

Brooklyn to anyone who subscribes to this theory. Certainly, I could never hope

to peddle that bridge to readers of mine. Sheerly astute as they all are

(without exception), they can tell a put-on when they see one (even when my

tongue is in only one cheek).

Biologically predisposed to honesty

or not, men are, I think, more likely to be inhibited by sex than women. And so

we find in eight-pagers that everyone is candid about their desires, entirely

open to any and all sexual practices, eager for sex to the exclusion of any

other consideration, and with their candor, openness, and eagerness, they

banish bashfulness and timidity and fear--and inhibition--from the conjugal couch.

And the concluding joke (not to mention the comic dialogue that often infects

the action throughout) completes the banishment with an outrageous guffaw: the

joke is on anyone who doesn’t accept their carnal appetites as being wholly

natural. When one of the principals fails in performance, incidentally, it is

usually a popular culture character with a reputation for virility. The lesson

in the tale is a comfort to the (male) reader: see, macho guys aren’t any more

expert at this than you are (in fact, if the truth be known, probably none of

them can ever get it up).

Laughter breeds acceptance. And it

is relaxing. Few human enterprises are as fraught with tension as a sexual

encounter, and while laughter during sex is usually counterproductive, laughter

about sex is relaxing: it relieves us from the strain of pretense, the pretense

that we are immune from the imperfections that undermine performance in bed,

or, alternately, that we are somehow above the fray, unconcerned because we are

uninterested in sex or sexual performance.

The cast of this biblical bawdry

completes the psychological sabotage the eight-pagers attempt. The characters

so joyously depicted flagrante delicto in them were chosen from popular culture

(comic strip characters, movie actors and actresses, gangsters, politicians) or

folklore (traveling salesman, bellhop, secretary applying for a job, starlet

seeking stardom). Such personalities, whether fictional or real, were old

acquaintances of the readership. As Gluckson says: “The use of familiar

characters helped destroy the artificial separation of sexuality from the rest

of readers’ lives.” To which, Les Daniels (in Comix: A History of Comic Books in America) adds: “The commentary

on [sex] which [the eight pagers] treated was implicit in the contrast between

the immaculate originals and the [sweaty] imitations. Somewhere between the two

extremes of purity and pornography lay the truth about human behavior. ...” To

see that Blondie and Tillie the Toiler had sex lives as real as those of their

readers assuaged fears and insecurities: despite these characters’ “public

appearances” in newspapers where they seemed pristine and sexless, offstage

they had “secret sex lives” just like everyone else did. Appearances were

therefore deceiving. Reality was something a little messier. To admit to this

truth was to accept one’s sexuality—perhaps even to embrace it.

The Tijuana Bibles also served an

educational function. In the days of their debut, no one talked about sex in

any precise way. The youth of America often grew up largely ignorant of the

specifics of copulation. The eight-pagers removed that ignorance. In Tijuana Bibles Book 2, underground comix

publisher Ron Turner explained: “Tijuana Bibles ... were very helpful. They

were gross and extreme but they showed us how fucking was done and that there

was more than the missionary position. And we would read them and practice what

we saw. Very instructional.”

Some maintain that TJ bibles paved

the way for comic books. Seems to me I read a diatribe one time by literary

critic Leslie Fiedler in which he maintained that these little sex comics were

reincarnated as superhero comics. The legendary chronicler of eroticism in most

of its forms agrees. Writing in the rocking rhythms of prose both erudite and

vaguely erotic, Gershon Legman noted that the comic books of the 1940s

“substitute legal blood for illegal semen, crime for coitus, in the erotic

comic book of a dozen years standing, quadrupling its size fearlessly as they

brought it forth from under the counter, legal now in its sadism where it had

been criminal then in its sex” (Tijuana

Bibles Book 3). Certainly, turgid superheroic musculature evokes at a

subconscious level images of the similarly engorged sex organs that are

flaunted in the eight-pagers.

Alas, the artwork in eight-pagers is

scarcely on a par with over-the-counter comic books. Even the earliest

commercially produced comic books were drawn better than most TJ bibles. The

best art in the latter is found on the covers, where bold lettering and design

overwhelm otherwise amateurish rendering. Inside, the drawings, while explicit,

are typically crude laboriously overwrought scratchings. Some of the art shows

individualistic style but no flare. What’s even more disappointing, few of the

naked ladies on display inspire any heavy breathing by reason of penned

pulchritude. These aren’t Playboy playmates. No mammoth mammaries. No pouting stares into the camera. No

pendulous poses or gorgeous gams. Just naked ladies. Anatomically correct but

scarcely inspirational.

The artists (who are almost all

entirely anonymous) made up for their lack of drawing ability with an almost

clinical explicitness in detailing sexual organs and methods of congress. The

informational value here superseded the entertainment function. That’s probably

why none of the examples I’ve seen display any visual sense of humor. Why, for

instance, wouldn’t the artists drawing ersatz Popeye or Alley Oop depict their

organs with the same distinctive bulge at the extremity that signifies virility

in the forearms of the characters? They passed on a marvelous opportunity for

pictorial comedy, seems to me. Clearly, they were less interested in such fine

points of cartooning than in explicitness for the sheer sake of explicitness.

By far, the best artwork in the TJ

bibles, in my view (although scarcely encyclopedic on the matter), was

committed by Wesley Morse. Morse’s

drawings are clean and expert, his line lively and confident. In this genre’s

most compendious history, Donald H. Gilmore’s four-volume Sex in Comics (Greenleaf, 1971), Gilmore identifies twelve artists

who did much of the work. He identifies them not by name but by style, giving

each distinctive manner of rendering a numerical author—Artist 1, Artist 2,

etc. Of the so-called Tijuana Dozen, Morse, Gilmore’s Artist 8, is without

quibble the best, the most consistently amusing and well-executed cartoon

drawing. If all TJ bibles had been drawn by artists of equal skill, they’d

constitute an underground of cartooning masterpieces unsurpassed until recent

times, when Playboy’s Little Annie

Fanny joined us. Morse had a nearly invisible career in comics. He had

contributed a single-page strip, Beau

Gus, to the first issue of a 1938 comic book, Circus, which ended its run with No.3 but included work by a

star-studded list of contributors—Basil

Wolverton, Jack Cole, Will Eisner, and Bob

Kane. Judging from the samples in the Gallery at the end of this Hindsight

entry, Beau Gus had an earlier life in comic strips, too, in 1933. Written, apparently,

by Bud Wiley, its run, if it had one, was doubtless very very brief, and it may

have never reached the syndication stage. In the 1920s, Morse’d produced three

very short-lived comic strips: Kitty of

the Chorus (March 20-April 14, 1925), Switchboard

Sally (which debuted June 15, 1925, and ran, probably, for less than six

months; written by H.C. Witwer), and Frolicky Fables (November 23, 1925-April 10, 1926)—all identified and

rescued from complete obscurity by Allan

Holtz in his compendium of comic strip names and dates. Morse dropped

completely out-of-sight until he re-emerged in the early 1950s, illustrating

Bazooka Joe for Woody Gelman. (For that story, visit Opus 127 by clicking here.)

Tijuana Bibles faded from the scene

in the 1950s, perhaps because Playboy and its host of imitators began to perform the educational function that

eight-pagers had served in the decades before. Without the raison d’etre of satisfying sexual curiosity to sustain their

circulation, the little sex comics had to stand on their crude art and their

gross comedy. Neither were of sufficient interest to keep the booklets in

production. Now we can find them only in esoteric reprint collections, most of

those almost as rare as the original artifacts. But these relics are still the

same joyous celebrations of sex that they were when they first seeped into the

cultural scene seventy years or more ago. I recommend you find one or two

someday and kick back and relax and let yourself be drawn into a world in which

sex preoccupies everyone’s every waking moment. A world different from the

world around us but only in its unrelenting merriment. We should all be so

lucky.

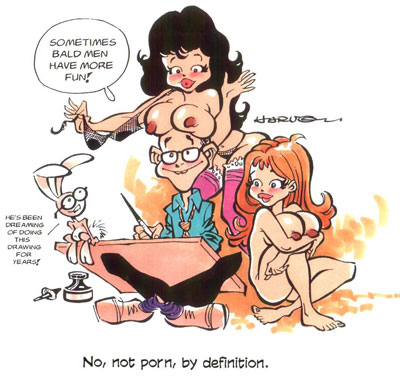

Gallery. Wesley Morse is the only cartoonist represented in the Gallery here—a few scattered panels from a couple of his TJ bibles ouevre, a two-page comic commentary from an unknown source, and two Beau Gus strips, one of which I own the original of. It’s only partly inked: the lettering is still in pencil. And I’ve reproduced one of its panels as large as the original art on the page with the eight-page items.

Footnit:

This essay, minus a few asides, appeared as the introduction to an Eros

collection of eight-pagers a few years back.

|

|||||