WHO

DISCOVERED SUPERMAN?

Rummaging

Through a Host of Claimants

WE KNOW WHO

INVENTED the Man of Steel. Jerry Siegel. But the invention in early 1933 was

followed by frustration: for the next four years plus a few months, Siegel and

his drawing partner Joe Shuster tried in vain to sell their creation to

newspaper feature syndicates and to publishers who were just hatching the

comic book business by reprinting newspaper comic strips in magazine format.

Nobody wanted this super strong refugee from the disintegrated planet Krypton.

And then, all of a sudden, Superman was “discovered” by a young editorial

assistant tangentially connected to the McClure Syndicate. Sheldon Mayer, just

out of his teens, was working with M.C. “Charlie” Gaines, who, in turn, was

functioning as a sort of freelance salesman and packager, scouting for printing

jobs for the two new color presses McClure had acquired when Bernarr

MacFadden’s scurrilous Daily Graphic folded in 1932. Hanging around the

McClure offices, Mayer saw the Superman comic strip Siegel and Shuster

had submitted in the hope of getting their brain child syndicated. And Mayer’s

brain exploded.

“I

went nuts over the thing,” Mayer said years later when remembering the event.

“It was the thing we were all looking for. It struck me as having the elements

that were popular in the movies, all the elements that were popular in novels,

and all the elements that I loved.”

But

he couldn’t convince anyone to sign up the feature. Not Gaines. Not any of the

McClure officials.

“They

all asked me what I thought of it,” Mayer said. “I thought it was great. And

they kept sending it back.”

Apparently,

Siegel and Shuster submitted their Superman idea more than once.

Ron

Goulart, in his Great American Comic Books, takes up the story: “Mayer’s

persistence got Gaines interested enough to look the material over again.”

This

time—supposedly late fall 1937 or early 1938—something clicked.

Said

Mayer: “He took it and looked at it and read it, and he said, ‘You think this

is good?’ And I said, ‘Yeah!’

Gaines,

despite having just a few years earlier participated in the publication of a

pioneering comic book of newspaper strip reprints, 1934's Famous Funnies, did not yet think of himself as a comic book publisher. Moreover, his

association with McClure was not in the editorial department. His job was

rounding up printing jobs to keep McClure’s color presses running as many hours

a day as possible. To this purpose, he had hired young Mayer to paste up

newspaper comic strips in magazine format pages for Dell Publishing Company to

produce as Popular Comics, The Funnies, and The Comics. Gaines

knew Harry Donenfeld, a somewhat shady character who operated a printing

company, Donny Press, that published “spicey” (coy sex) magazines, and

Donenfeld, Gaines heard, was taking over a comic book publishing company,

National Allied Publishing, a shoe-string enterprise run by a picturesque and

imaginative ex-cavalry officer, Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson, who was just

then on the cusp of launching a new title, Action Comics.

“Legend

has it,” writes Goulart, “that Gaines showed the Superman strips to

Donenfeld and persuaded him to add the feature to the forthcoming magazine.

Vincent Sullivan, who was editor of Action, recalled things somewhat

differently: ‘Donenfeld had little or nothing to do with the selection of

features and things of that nature.’ The samples were shown directly to editor

Sullivan. ‘When they showed this thing to me that they’d been trying to sell,

it looked good to me, and I started it. That’s how Superman got going.’”

He

told Siegel and Shuster to re-do their newspaper strip for magazine

publication, but Shuster, to meet Sullivan’s demand for a rush job, simply

performed emergency surgery on the strips: he cut them into individual panels

that he then pasted up in page-size grids and sent the final product back. By

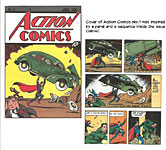

then it had been decided that Superman would be the lead feature in the first

issue of Action, and Shuster drew the cover, a reprise of an interior

panel that showed Superman lifting an automobile over his head. Action

Comics No.1, cover-dated June 1938, hit the newsstands April 18, 75 years

ago last spring (hence, this essay in commemoration of the anniversary).

“When

Harry Donenfeld first saw that cover of Superman holding that car in the air,”

Mayer remembered, “he really got worried. He felt that nobody would believe it,

that it was ridiculous—crazy.”

“Probably

because of Donenfeld’s alarm,” Goulart speculates, “the next few covers didn’t

show Superman or even mention him.” Instead, “drawn by Leo O’Mealia, they

showed plausible adventure” scenes. But “the public,” Goulart goes on, “was

far quicker to grasp the new character’s appeal.

According

to John Kobler’s profile of Siegel and Shuster in The Saturday Evening Post (June

21, 1941), sales on the first three issues of Action were not

particularly impressive. “But with the fourth, Action Comics spurted

mysteriously ahead of its fellow publications.” Said Goulart: “Donenfeld heard

the rumble of distant drums’” and ordered a newsstand survey, which discovered

the reason for the surge:

“Children

were clamoring not for Action Comics but for ‘that magazine with

Superman on it.’”

(Donenfeld

reportedly also ran a questionnaire in Action Comics No.4, asking readers

to list in order of preference their five favorite stories of the eight in the

issue. Of the 542 responses, 404 listed Superman first; another 59, second. If

Donenfeld ran a questionnaire in the fourth issue, there must’ve been earlier

indications of Action’s popularity, contradicting Kobler. Or else

Donenfeld was simply, unaccountably, indulging an impulse of insecurity with

his in-magazine query.)

Doubts

dispelled, “quivering with excitement,” Goulart said, “Donenfeld ordered

Superman splashed all over the cover of succeeding issues.”

Not

quite. Superman returns to the cover for No.7, cover-dated December 1938. But Action goes without him on the cover again until the May 1939 issue, No.12, and even

then, Superman does not appear in the scene depicted: instead, he is in a

circular inset vignette, shown breaking free of chains across his chest.

The same

device is repeated on every Action Comics cover through No. 127,

December 1948—even those with Superman in the cover illustration; and only

three covers in the rest of 1939 (July, September and November), appear without

Superman in the principal scene. In short, beginning a year after his debut,

Superman is, as Goulart says, always on Action’s cover. But the first

year’s occasional hiatus implies that Superman’s newsstand popularity was not

quite as suddenly recognized by his publisher as the legend would have it. Or

does it? The same

device is repeated on every Action Comics cover through No. 127,

December 1948—even those with Superman in the cover illustration; and only

three covers in the rest of 1939 (July, September and November), appear without

Superman in the principal scene. In short, beginning a year after his debut,

Superman is, as Goulart says, always on Action’s cover. But the first

year’s occasional hiatus implies that Superman’s newsstand popularity was not

quite as suddenly recognized by his publisher as the legend would have it. Or

does it?

The

syndicated newspaper Superman debuted January 16, 1939, distributed by

McClure. Rollout for national distribution must have begun a few months before,

in the fall of 1938; so we may safely assume that someone at McClure—and

probably various personages around Donenfeld—realized something was going on

with Superman among young readers by the time of the fourth issue. And that

was, indeed, the case, as we’ll see anon.

The

success of Superman, usually viewed as the spark that ignited the comic book

industry, was not an unalloyed serendipitous event. With Superman’s triumph at

the newsstands, comic books soon ceased being produced for general

readership—for pulp magazine readers, adults as well as young people who read

the pulps, the audience the first comic book publishers had aimed for. After

Superman, publishers shifted their focus to a youth audience. They realized

that’s where the dimes were. Thus, Superman’s success condemned comic books to

an adolescent readership for generations, stunting the growth of the medium

until the end of the 20th century.

Even

Sullivan was surprised at Superman’s sudden popularity, Goulart said: “When

asked if he’d anticipated the new hero’s success, he replied, ‘No, I don’t

think anybody did.’ He said he’d simply bought the feature because ‘it looked

good. It was different and there was a lot of action. This is what kids

wanted.’”

There

it is. That’s the legend of the advent of Superman. Superman was discovered by

20-year-old Sheldon Mayer with a mildly enthusiastic assist from 26-year-old

Vincent Sullivan.

And

then, just a few years ago, we heard from Douglas Wheeler-Nicholson, the

Major’s son, who told a different story.

INTERVIEWED

by Jim Amash in Alter Ego No.88 (August 2009), Wheeler-Nicholson fils said unequivocally that his father “discovered” Superman two years before Mayer

and Sullivan had any inkling of the character. The Mayer-Sullivan claim, said

Doug (as we’ll call him to distinguish him from his father, the Major), is

“crap”—“just nonsense.”

He

continued: “I know Action Comics was developed by the Old

Man [as he called his father] as a vehicle for Superman.”

Doug

and others of the Major’s descendants have “written proof” that the Major had

seen Superman in the summer of 1935 and had told Siegel and Shuster that he

wanted to publish the feature.

“Sullivan

had editorial say in things,” Doug said, “but he certainly didn’t discover Superman. That was already a done deal. It had been

lying on the Old Man’s desk with the Old Man saying, ‘I want it.’”

With

the arrival of Doug on the historical landscape, Shelly Mayer disappears

altogether from the discovery story, and Vincent Sullivan is present only to

have scorn and ridicule heaped on him. .

How

credible is Doug’s contention? Let’s find out.

Since

the blockbuster Wheeler-Nicholson interview appeared in Alter Ego, two

new biographies of Siegel and Shuster and Superman have been published: in

2012, Larry Tye’s Superman: The High-Flying History of America’s Most

Enduring Hero; and in 2013, Brad Ricca’s Super Boys: The Amazing

Adventures of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster—The Creators of Superman. In

pursuing the story of the discovery of Superman, I read the pertinent parts of

both of these. Each seemed, at first blush, to include new scraps of

information about Siegel and Shuster’s quest. But then I re-read Les Daniels’

1998 Superman: The Complete History and realized that it is a

surprisingly comprehensive account, especially considering that it was

virtually a “house” document (produced with the extensive cooperation of DC

Comics) and therefore unlikely to be as painstaking about such minutiae as has

been scraped up by the other authors. But in this expectation I was happily

disappointed: in fact, most of what I had supposed was fresh minutiae in the

other two books, Daniels includes or alludes to. I also read Gerard Jones’ 2004 Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters, and the Birth of the Comic Book, which is even more detailed in examining the timeline between Superman’s

conception and his inaugural publication. I also read (again) the interview

with Siegel and Shuster published in Nemo: The Classic Comics Library No.2

(August 1983).

From

all of the above, I’ve cobbled together a single plausible narrative, hitting

the main points with only a few detours along the way. It scarcely includes

every detail and nuance; for those, you should read the sources.

About

the conception of Superman, no dispute exists.

Joe

Shuster, born July 10, 1914 in Toronto, Canada, moved with his family to

Glenville, a suburb of Cleveland, Ohio in about 1924. A few years later when

enrolled in Glenville High School, he met Jerry Siegel, who was the same age,

born October 17, 1914; they were maybe 14 when they met. Both fans of what

would someday be called science fiction, the two hit it off immediately. In

about 1929, Siegel had “published” a typewritten and hectographed magazine

entitled Cosmic Stories; it may have been the first sf fanzine in the

U.S., maybe in the world. In the summer or fall of their junior year, they

produced another sf magazine, Science Fiction, and in the third issue

(January 1933), they offered a story entitled “The Reign of the Superman.” In

this incarnation, Superman is a villain, using his powers for evil purposes.

Siegel

may have been inspired by Philip Wylie’s Gladiator, whose hero, Hugo

Danner, was the son of a scientist who has turned him into a super-child. Hugo

tries to save the world, but the world, as always suspicious of anything

unusual, mocks him and uses him, turning him sour on mankind; he goes mad. But

Siegel’s evil Superman, a vagrant named Bill Dunn, seeks world domination. He

kills the scientist who injected him with the serum that gave him power, and

when the serum wears off, he realizes he should have used his powers for the

good of mankind.

A

few months later, Siegel took the lesson from Bill Dunn and reimagined Superman

as a good guy. According to the conception legend, he had this inspiration

during a sleepless night, getting out of bed every couple hours to make notes,

and the next morning, he got up and raced a eleven blocks south from his home

at 10622 Kimberley Avenue to the apartment building on Armor Avenue where

Shuster lived, and the two sat down and gave Siegel’s idea a visual identity.

But this Superman, Daniels says, had no superpowers and no costume: he wore

ordinary pants and a plain t-shirt, no emblem. No Lois. No secret identity in

the form of a mild-mannered newspaper reporter who wears eye glasses as a

disguise.

The

fictional world fairly teemed with kindred strong men. Tarzan, Doc Savage, not

to mention Hercules and Samson. Even Popeye. At one time or another, Siegel

acknowledged an interest in each of these. But novelist Brad Meltzer offered

another explanation for Siegel’s inspiration.

Siegel

had lost his father, Michel (sometimes called “Mitchell”), who died of a heart

attack while a robbery was transpiring in his second-hand clothing store at

3560 Central Avenue on the night of June 2, 1932. “I believe the world got

Superman because this kid lost his father,” Meltzer told Patrick O’Donnell and

Michael Sangiacomo at the Cleveland Plain Dealer. “It can’t be just a

coincidence,” Meltzer said, “that Michel died and within a short time, his son

creates the world’s greatest superhero.”

Deprived

of his father, young Jerry sought justice symbolically, O’Donnell and

Sangiacomo say: “He invents the ultimate crime-fighting superhero ever,

Superman, to be his instrument of vengeance” against the criminal element of

society.

In

his 2008 murder/espionage novel, Book of Lies, Meltzer has Michel die of

gunshot wounds inflicted by the robbers, the incident becoming a plot element

in the book. The surviving Siegel relatives remember hearing stories about

Michel being shot during the robbery, but the death certificate reports that

Siegel had chronic myocarditis and died of heart failure, no mention of bullet

wounds.

Jerry

Siegel never connected his father’s death to Superman—and his widow, Joanne,

doesn’t think that tragedy inspired her husband—but this fact of Jerry’s early

life had surfaced before Meltzer brought it up. In his 2004 history, Jones

rehearses, as fact, the story that Michel was shot to death in his store. Like

Meltzer, Jones believes the father’s death “had to have an effect” on Jerry. As

Jones told David Colton at USA Today, “Superman’s invulnerability to

bullets, loss of family, destruction of his homeland—all seem to overlap with

Jerry’s personal experience. There’s a connection there: the loss of a dad as a

source for Superman.”

Except

that, as Jones himself reports, the good guy Superman that Siegel invented

didn’t have superpowers, wasn’t invulnerable to bullets. He had merely

“extraordinary strength.” Moreover, as anyone who has read Jones’ tome knows,

he is as much novelist as historian, imagining conversations and semi-fictional

incidents that he sprinkles throughout his ostensibly factual account of the

birth of comic books. Jones’ technique (also employed by Brad Ricca) is an

entirely acceptable practice in biographical works, but when encountered by the

reader, it encourages a healthy skepticism.

Two

novelists, then, have been seduced by the coincidence of Siegel’s father’s

being shot to death and the subsequent creation of a fictional hero impervious

to gunfire. But sequence alone is not a cause-and-effect relationship, no

matter how it’s tarted up by the writers of fiction. What’s more, the hero’s

invulnerability, while neatly explained if he has been invented to avenge a

shooting death, cannot be so readily seen as protection against a heart attack.

I’m afraid we’re left with the highschool self-styled nerd and his passion for

early science fiction as a much more convincing explanation for the creation of

the superhero who sparked the comic book industry into being.

OVER THE NEXT

FEW WEEKS, Siegel and Shuster conjured up a Superman story (about which they

remember only that maybe the character crouched on building ledges and had a

bat-like cape—maybe, maybe not) and offered it to the publisher of a comic book

they’d just seen, Detective Dan. Consolidated Book Publishers wrote back

(August 23, 1933), saying if they ever published another comic book, they might

be interested in using the story. But nothing came of this vague proposition.

And Shuster, somehow convinced that his drawings had been so poor that they’d

condemned the effort, tore up and burned everything but the inked cover.

Jones

augments this event by reporting that Seigel, convinced Shuster’s drawings

weren’t up to the task of illustrating Superman, went looking for another

drawing partner in 1934. Russell Keaton, then ghosting Buck Rogers, was

one of the candidates; so was Mel Graff, who later created the comic strip Patsy.

When

Shuster found out what his life-long friend and presumed partner was up to, he

destroyed their first completed story in a fit of frustration, rage, and bitter

disappointment. But by 1935, Jones says, Siegel and Shuster were back together,

brooding about Superman. Superman was still undiscovered, but he had not been

lying idle. When

Shuster found out what his life-long friend and presumed partner was up to, he

destroyed their first completed story in a fit of frustration, rage, and bitter

disappointment. But by 1935, Jones says, Siegel and Shuster were back together,

brooding about Superman. Superman was still undiscovered, but he had not been

lying idle.

Although

their first Superman venture had been for Consolidate’s comic book, the boys

had not rested after that fizzle. At some point, Siegel decided to re-invent

his hero for syndication to newspapers as a comic strip. In the Nemo interview, he says that happened in late 1934. It was then, he says, that his

fabled sleepless night took place; but as Jones demonstrates, Siegel wasn’t

good at remembering dates: in one of his re-tellings of his nocturnal

inspiration, he said it was in 1931. Or 1932. And for a while, the night was

“hot,” a summer night, not in late in the year at all. For our present

purposes, however, it doesn’t matter when he tossed and turned and concocted

the heroic Superman: whenever it happened, it lead to a long gestation during

which Superman took more than one form.

In

re-conceiving for newspaper comic strip format the strong-man hero of the

Consolidated offering, Siegel added a telling element: Superman would have a

secret “civilian” identity. Other fictional heroes had secret identities—Zorro,

the Shadow. The Scarlet Pimpernel particularly. The movie starring Leslie

Howard and Merle Oberon had opened in 1934, and Jones speculates that “Howard’s

sniveling submission to Oberon’s disdain (all in the interest of preserving the

secret of Sir Percy Blakeney’s identity as the Pimpernel) proved to be the

perfect model for Clark Kent’s twisted relationship with Lois Lane.” But Siegel

claimed he didn’t care much for the movie; “The Mark of Zorro,” however, he

loved.

But

there was more to the Clark Kent persona than imitation.

Said

Siegel (in Nemo): “Clark Kent grew not only out of my private life, but

also out of Joe’s. As a high school student, I thought some day I might become

a reporter, and I had crushes on several attractive girls who either didn’t

know I existed or didn’t care I existed. ... It occurred to me: what if I was

[secretly] real terrific? What if I had something special going for me, like

jumping over buildings or throwing cars around or something like that? Then

maybe they would notice me. That night when all the thoughts were coming to me,

the concept came to me that Superman could have a dual identity, and that in one

of his identities he could be meek and mild, as I was, and wear glasses, the

way I do. The heroine, who I figured would be a girl reporter, would think he

was some sort of worm; yet she would be crazy about this Superman character who

could do all sorts of fabulous things. In fact, she was real wild about him,

and a big inside joke was that the fellow she was crazy about was also the

fellow whom she loathed. By coincidence, Joe was a carbon copy of me.”

It

is often maintained that this celebrated triangle of two is the perfect

autobiographical embodiment of Siegel and Shuster’s being what we could call

today “nerds.” Unathletic, unattractive, uninteresting and socially inept—but

mostly bookish.. But that goes too far. Some years ago, I gave a talk about how

much of the comic book industry had been, in effect, invented by Jews, and I

mentioned Superman as enacting the daydream secret identity of two nerds in

Glenville High School—just as Siegel described it. A member of the audience,

which was part of the Adult Education program at a local synagogue, pointed out

that Glenville was a largely Jewish community (in 1924, the population was 70%

Jewish), and in Siegel and Shuster’s day, “all the students at Glenville High

School would have been ‘nerds,’” reflecting a traditional emphasis on education

and intellectual and artistic aspiration in Jewish culture. No one would have

been ridiculed or made to feel inferior for being a nerd.

So

the really terrific secret identity Siegel said he aspired to did not reflect

the longing of an ignored and ostracized nerd: it reflected the lack of success

with girls that Siegel and Shuster no doubt experienced. And that is

essentially an adolescent proclivity, not nerdish. Nor Jewish.

Siegel

and Shuster prepared comic strips for the new Superman and began circulating

them to feature syndicates, hoping for a sale. Like most young cartoonists in

those days, they knew there was good money in syndicated comic strips; getting

syndicated to newspapers had always, in effect, been their first objective. The

Consolidated effort had resulted from a momentary distraction. Still, they also

occasionally approached comic book publishers, thinking such magazine

publication could serve as a launching pad into newspapers. And they even went

to men’s pulps, including one of Donenfeld’s slightly risque productions. “Joe

liked to draw sexy girls and Jerry’s work could have a rough edge,” Jones says.

“They might have felt that Superman could be adjusted to fit the naughtiness of Pep or the luridness of Spicy Detective.”

Apparently,

Siegel and Shuster produced several versions of Superman over the next months,

tailoring their presentations for whatever outlet they approached. Jones says

the version of Superman that Mayer saw was the one aimed at Donenfeld’s

magazines. In it, Superman captures a murderess (“a bottle-blonde chanteuse in

her dressing room”) thereby securing the release of a wrongfully imprisoned

woman.

Then

in early 1935, they saw the first issue of New Fun, a tabloid-size

publication with a color cover but black-and-white interior pages. Cover-dated

February 1935, it included stories that had been originated expressly for the

magazine. Unbeknownst to the Cleveland duo, New Fun’s publisher, Major

Wheeler-Nicholson, intended the magazine to serve as a sales vehicle for new

comic strips (a “catalogue,” he called it) as well as a publication for

newsstand sales. The Major had been syndicating his own serial fiction to

newspapers since about 1925. He also adapted classical literature (such as Treasure

Island and The Three Musketeers) to comic strip form with abridged

text running beneath the panels (or integrated into the pictorial layout). With New Fun, he planned to enter the syndicated comic strip business. To

that purpose, he had rounded up a few artists and writers to create new strips

for his “brochure.”

Siegel

and Shuster knew none of this when they first saw New Fun; what they saw

was simply a market for new material, and they immediately devised several

features and wrote the Major with their ideas. He liked two—Henri Duval of

France, Famed Soldier of Fortune, and Doctor Occult the Ghost Detective—and

ordered a page of each. Soon after they delivered the pages, Siegel and Shuster

received a check for $12, $6 a page, for their first published effort—in New

Fun No.6 (cover-dated October 1935).

Not

too long thereafter, the Major wrote them on June 6, 1935:

“I

am enclosing herewith a pencil sketch which seems to have been lost in the

shuffle here, as it appeared to be simply a piece of wrapping paper. I believe

that there are possibilities in this sketch and in the idea. We would be

willing to give it a tryout in the magazine if your completed job stands up

with what the pencil sketch would seem to show.”

Jones

speculates that the sketches and notes were jotted on the wrapping paper by

Shuster as he and Siegel anticipated selling Superman into national syndication

as a newspaper comic strip. Most of the phrases (“The Smash Hit Strip of

1936—SUPERMAN!” and “The Greatest Super-Hero of All Time!” and “The Strip

Destined to Sweep the Nation!”) aspire to promote the comic strip Superman. Clearly, the Major hasn’t actually seen any Superman sample strips: he wants to

see if a “completed job stands up with what the pencil sketches would seem to

show.” But how did he get the wrapping paper?

As

a youngster, Shuster often sketched on wrapping paper and the blank backs of

wall paper, and when doodling ideas in later years, he probably continued the

practice rather than using expensive artboard for the purpose. He doubtless had

sheets of such doodled-on wrapping paper lying around his room, and he may have

grabbed this sheet to wrap around the Henri and Occult strips

when he shipped them off to the Major.

Prompted

by the Major’s expressed interest in the Superman sketches, Siegel and Shuster

eventually sent him a Superman story, which they prepared even while producing

more Henri and Occult pages for New Fun. By the time they

sent him Superman, they probably realized that the Major’s magazine doubled as

a catalogue for selling features into newspaper syndication, and they were

eager to take advantage of the opportunity. On October 4, 1935, the Major

responded:

“The

Superman strip is being held for an order now pending from a national

syndicate,” he began, but then he tacked in another direction: “It is my own

idea, based on a lot of experience in selling in the syndicate game, that you

would be much better off doing Superman in full page in four colors for one of

our publications. I consider our magazines primarily catalogues of features and

the selling resistance is considerably less for color stuff than it is on daily

back-and-white. We also have pending an order for a sixteen-page tabloid in

four colors in which we could include Superman around the first of the year if

we have it in colors and running. Use your own judgment on this. I think myself

that Superman stands a very good chance.”

This

letter, more than June’s epistle, was the “written proof” that Doug had of his

father’s early commitment to Superman. But Siegel and Shuster were

disappointed. While the Major seemed to promise to market the strip, he also threw

cold water on their hopes for doing a daily comic strip. The best the Major

held out was the prospect of a color comic, perhaps a Sunday strip although

that’s not entirely clear. In the last analysis, the partners turned down the

Major’s offer because they were leery of his shaky finances. Like all of the

Major’s artists and writers, they’d been getting paid, if at all, weeks or

months after publication. And the Major’s plans for Superman were all couched

in iffy language: the deals in the offing were all just “pending”; nothing

definite. They decided to continue to try to sell Superman elsewhere and asked

the Major to return the strips they’d sent him.

Unbeknownst

to them, the Major was on the brink of bankruptcy. Without sufficient capital,

he was unable to bring out the next issue of New Fun until January 1936.

By that time, he’d secured additional backing from Donenfeld, who had been

joined by Jack Liebowitz, a much more astute financial manager than the

back-slapping deal-making Donenfeld. With Donenfeld’s support, the Major

launched his second comic book, New Comics (which eventually morphed

into Adventure Comics), and for it and another new title he intended to

publish, Tye says he sent Siegel and Shuster a list of several new features

that he wanted them to produce— Federal Men, Calling All Cars: Sandy Kean

and the Radio Squad, Spy, and Slam Bradley. As conceived by the

Major and executed by Siegel and Shuster, the two-fisted Slam Bradley was a

knock-off of Roy Crane’s successful comic strip adventurer, Captain Easy.

Slam’s debut was delayed a year until the Major could scrape together the

resources to get Detective Comics out of the chute.

SIEGEL AND

SHUSTER had plenty on their plate, but they continued to send Superman around

to syndicates and other prospective publishers. According to Tye, “by the end

of 1937, copies of Jerry and Joe’s Superman comic strip could be found in the

backs of filing cabinets and the bottoms of wastebaskets across the world of

publishing.” Among those they tried in 1936 was Popular Comics, being

run for Dell by Gaines; Siegel imagined that the reprint title, like the

Major’s New Fun, might serve as a platform for Superman, leading to

syndication. Gaines, Jones says, tried to get Superman into the title but

failed.

They

sent Superman to Ledger Syndicate, which rejected it, saying: “We feel that

editors and the public have had their fill for the time being of interplanetary

and superhuman subjects.” Space traaveling Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon

probably, but a plethora of “superhuman subjects”? Other rejections were

reputedly similar. In 1937, they approached Tip Top Comics, the reprint

vehicle for United Feature Syndicate. United held the strip for a while but on

February 18, dropped the axe:

“I

am afraid we are not ready to use your pages for some time. The trouble with Superman, for example, is that it is still a rather immature piece of work. It is

attractive because of its freshness and naivete, but this is likely to wear off

after the feature runs for a while.”

“Immature”

translates, Daniels says, “as not suited to adult newspaper readers.” The same

criticism was inherent in some other rejections. Newspaper editors had long

recognized that their comics section, while attractive to children, is aimed at

adults. And comic book publishers—most of whom at the time were publishing

reprint collections of newspaper strips—also envisioned an adult readership.

That would change with comic books, though, once Superman established a young

audience for the four-color fantasies.

In

late 1937, the Major began work on another comic book title. When he started Detective in January 1937, he had intended to bring out simultaneously a companion title, Thrilling, but couldn’t summon the financing. By the fall, he figured he

could swing it. What’s more—he desperately needed a new, successful title.

Jones says the Major was deep in debt to Donenfeld, who had financed the

printing of National’s comic books for some time; and the revenues from sales

were not, it seemed, enough to pay off the debt. The Major and his editor,

Vincent Sullivan, began collecting material for the new title, which they’d now

changed to Action Comics.

At

this point in our nail-biting narrative, the plot falls into confusion with

different players accorded the same mutually exclusive roles. I’ll start with

Jones’ version.

Looking

over what he had, Sullivan felt he needed something else—“a catchy central

character that he could splash on the cover.”

So

Sullivan went to his former cohort, Shelly Mayer, who’d been an editor for the

Major about the time of the Detective launch (he’d quit, Jones says,

when the Major couldn’t pay him, and he’d gone to work full-time for Gaines).

Sullivan asked Mayer if Gaines had anything promising laying unspoken for

around the McClure shop. And Mayer told him about Superman. And Sullivan liked

what he saw.

So

far, this elongated narrative fits into the legend more-or-less. But questions

lurk. Why did Sullivan go to Mayer? Sullivan had been the Major’s editor long

enough to know that the Major went directly to Siegel and Shuster for ideas for New Comics in late 1935; so if Sullivan needed “a catchy central

character” for Action, why didn’t he go to Siegel and Shuster? Siegel

and Shuster had a track record of cranking out concepts for the Major.

And

there are other unexplained anomalies. First among them is the letter Siegel

wrote to Liebowitz on December 6, 1937. In this epistle, Siegel describes

several new characters that, Ricca says, he is proposing for Action Comics: “Bob

Hazard, a ‘world-wide adventurer,’ and The Crimson Horseman, a ‘masked, cloaked

rider of mystery who metes out grim justice in a lawless cattle country where

the law is openly flouted’ ... The Wraith, an unusual detective with ‘abnormal

glands’ [that make his senses ‘acute to a hypersensitive degree’] ... ‘He

tracks down criminals like a prowling beast ... frightens criminals half out of

their wits because they believe him to be not of this world,’ Chesty Crane [an

athlete ‘full of sport action,’ and] Streak Marvel, a ‘scientific genius.’

“Jerry

suggests such variety because he envisions that ‘Action Comics would contain a

well-balanced list of features: adventure, western sport, and science fiction.’”

Why

is Siegel writing Liebowitz? Ricca doesn’t indicate whether Siegel’s letter is

in response to a request from Liebowitz, but why else would he write someone

he’d probably never heard of? Larry Tye says Siegel was not writing to

Liebowitz but to Gaines, in response to Gaines’ request for material for an

8-page weekly tabloid (which we’ll get to in a trice). But if Siegel is writing

Liebowitz, how did Liebowitz get involved?

By

late 1937, Donenfeld and his partners Liebowitz and Paul Sampliner (who

operated Independent News Company, a distributor of magazines and the Major’s

comic books) owned National Allied Publications. They had financed the Major’s

comics and then connived to push him to the edge of bankruptcy. Douglas

Wheeler-Nicholson maintains that Donenfeld et al juggled numbers to give the

Major the impression that his comics were losing money. One of their scams,

Doug says, was to print more comics than they knew they could sell, and when,

in the normal practice of the day, the unsold copies were returned—and in

greater number than prudent printing would yield—they said the returns proved

the comic books weren’t selling. “They claimed the firm wasn’t making any money

because of all the returns.”

In

effect, the Major was told that he was piling up more debt, and in late 1937,

Donenfeld sued for the $5,878 he was owed, pushing National Allied into

bankruptcy court. “Since the Major obviously couldn’t pay it,” Ricca writes,

“Harry Donenfeld, after a simple but cold court maneuver, bought out his debt

and became the primary partner” in the Major’s business.

Said

Jones: “In early 1938, Donenfeld sent [the Major] and his wife on a cruise to

Cuba to ‘work up new ideas.’ When they came home, the Major found the lock to

his office door changed.” He was out.

Brad

Ricca makes Donenfeld a much more active agent in all of this, but I doubt it.

Donenfelt was a glad-hander, a back-slapper, not a doer. He made a career out

of acquiring other people’s companies. He forced the Major out of his, but I

don’t think he had the acumen to run a publishing company, and he probably

would not have realized that Superman was a promising creation. In several

accounts of the arrival of Superman, Donenfeld is described as being alarmed by

the picture of Superman lifting an automobile over his head on the cover of Action

Comics No.1, thinking no one would believe it and therefore no one would

buy the comic book. Not the reaction of a discerning, innovative publisher or

of risk-taker.

The

Major may have been gone as early as December 1937. Tye says Action Comics was

assembled by Sullivan and Liebowitz, who ran the company after the Major had

been kicked out the door. That might explain Siegel’s December 6 letter to

Liebowitz, assuming Liebowitz had written him, asking for ideas for Action

Comics.

Or

maybe Siegel wrote Liebowitz unsolicited—in response to a recommendation from

Gaines. Ricca says Gaines once wrote Siegel, strongly urging him to submit

Superman to Detective, but the date of this letter is not given in Ricca’s text;

and it’s not clear from Ricca’s language whether Gaines meant Detective

Comics or the Major’s company, also called Detective Comics, which was

formed to embrace the partnership with Donenfeld-Liebowitz. Ricca cites Gaines’

letter (without quoting any of it) when his narrative is dealing with the

events of the fall of 1937. He footnotes the reference, saying it comes from

Siegel’s “Story Behind Superman No.1,” but the footnote doesn’t date the

article (although Ricca says it’s in court papers—Exhibit X—in the Superman

ownership case before U.S. District Court, Central District of California, July

28, 2008); and the article itself isn’t listed in the book’s bibliography.

Daniels

says Gaines wrote to Siegel on November 30. Gaines had “kept an eye on Siegel

and Shuster” ever since their first submission to him in 1936. Now, he may have

something for them: “We are working on an idea entirely apart and separate from

such comic books, and we are looking for several good features, each weekly

story to consist of eight complete tabloid pages.”

“Siegel

sent Superman,” Daniels goes on, “and in December he visited National’s

offices.” Either then or soon thereafter, “Gaines, whose plans for the new

tabloid were stalled, asked Siegel for permission to offer Superman to Action

Comics.” Gaines may have made his request in the letter Ricca refers to

above, adding to the request a strenuous recommendation to seek publication of

Superman with Detective Comics (both the company and the publication). Or

Gaines may have talked to Siegel about it when Siegel visited New York. If, as

Daniels says, Siegel visited National’s offices, then he probably met

Liebowitz, who may have encouraged him to make other suggestions for Action

Comics while promising to look over his Superman submission.

Tye

gives Liebowitz an even more prominent role. In an echo of Sullivan’s writing

Mayer in search of leftovers from syndicate submissions, Tye says it was

Liebowitz who initiated the contact with Gaines, asking if he had “any material

around ... stuff that had been submitted to them which had been turned down,”

quoting from Liebowitz’s unpublished autobiography. “He sent me over a pile of

stuff. Among that pile of stuff was Superman which had been submitted by

Siegel and Shuster to the syndicate which had turned it down like all other

syndicates turned it down. It was six strips, daily strips, made for

newspapers. Anyway, we liked it.” “We” is presumably Liebowitz and Sullivan.

Tye

doesn’t list Liebowitz’s unpublished masterpiece in the book’s bibliography

(although I’m working from published but uncorrected proofs; maybe the final

product lists the book; then again, why list in a bibliography an unpublished

book that is therefore not available to curious readers?). Maybe that doesn’t

matter: the quotations from Liebowitz can be seen as showing that he is

probably more interested in insinuating himself into an unparalleled publishing

history than he is in factual reportage. Liebowitz wants a pivotal role in the

history. The same may be said for Sullivan and Mayer and Douglas

Wheeler-Nicholson.

In

his autobiography, quoted by Tye, Liebowitz claims “we” cut up the Superman

strips and “made a 13-page story out of it.” He also remembers picking the

first cover and harmonizing distribution and marketing. “That was the beginning

of the comic industry as far as I was concerned,” Liebowitz says, putting

himself conspicuously right smack in the middle of all the innovations. History

belongs to those who survive to write it, and Liebowitz’s unpublished tome is a

case in point.

But

to entertain for a moment the possibility that Liebowitz’s memoir is

scrupulously honest, if he and Sullivan were assembling Action Comics,

as Tye maintains, Liebowitz doubtless knew that Sullivan had written to

Mayer—if, in fact, he did—and he could have appropriated that piece of the

history with himself as the principal actor instead of Sullivan. Daniels agrees

that Liebowitz asked Gaines for leftover syndicate submissions. But Liebowitz

was still alive when Daniels’ book was published, and he may have been asked to

review Daniels’ typescript, whereupon, he “reminded” Daniels that he,

Liebowitz, was an active agent in securing Superman.

The

possibility exists, of course, that Liebowitz and Sullivan discussed the wisdom

of tapping Gaines’ slush pile for material for Action Comics—without

Liebowitz actually contacting Gaines. Liebowitz may not have known Gaines at

that point, but Sullivan had a way to get to Gaines through his old pal and

former fellow editor, Mayer. But the pesky question remains: why would Sullivan

write Mayer when he was on familiar terms with Siegel who was well-established

as an idea man for the Major’s books?

JONES SAYS ACTION

COMICS was assembled by Sullivan and the Major—presumably before the Major

was outed. Both the Tye and Jones scenarios permit Mayer to enter into the

narrative as the person who knew about those Superman strips just lying around

the McClure office. But nothing in either scenario explains why Sullivan would

write to Mayer when he already knew about Superman—and, if he had ever been

working closely with the Major, he most assuredly did.

According

to the Major’s son: “Superman was a major subject of discussion all the way

from early fall of 1937 right through the ashcan proposal, right through all

the troubles. It was a major source of discussion in the house. The Old Man

thought it was extremely timely, and he was very specific about a Nietzschean

kind of hero at this point of the Depression, and that this would be a perfect

thing to put forth to the public at this time. He talked about it extensively.

We talked about it at the dinner table.” Doug says his father intended Action

Comics as a “vehicle” for Superman, as a “showcase” for the character.

Doug

was about nine years old at the time, but discussions at the dinner table were

a vibrant family tradition, he says, so it isn’t surprising that he’d remember

something as exciting as the Superman concept. During his interview with Amash,

Doug often denies knowing things that might support his argument—saying, “I

don’t know” or “I don’t remember”—a sign of inherent integrity. But he’s not

always right, either.

He

maintains that the first issue of Action was assembled by the Major and

Sullivan—that the Major was “actively involved” in the company through May of

1938, that Donenfeld “didn’t actually have ownership until July or August.” But

documentary evidence seems to contradict him in a few instances—the most

blatant of which is the letter by which Siegel and Shuster give up all rights

to Superman. It is dated March 1, 1938, and is signed by Jack Liebowitz for

Detective Comics, Inc. (Interestingly, the Major was not apparently as grasping

as Leibowitz and Donenfeld: in at least one documented instance, he returned to

one contributor the rights for the piece contributed.)

The

Major could still have been actively involved at that point, simply ignoring,

as was his wont, such mundane matters as the business side of his enterprise,

leaving them to the one of his partners who was more adept at such

things—Liebowitz.

The

Major was certainly still functioning in his own company in December, when the

ashcan edition of Action Comics was produced. The ashcan had a cover

drawn by Creig Flessel (a superior artist who did a lot of excellent artwork

for the Major), but the interior pages, stapled together with the cover to

secure a copyright, consist of previously published material and no Superman

pages. And Flessel’s cover evidently didn’t depict Superman.

Doug

was unequivocal in denying any discoverer role to Sullivan, Mayer or Gaines.

Such ideas were patently false, he maintained. But to deny them the role of discovering Superman is not to deny them a role in obtaining Superman

material for the first issue of Action Comics.

In

any event, Sullivan surely knew about Superman. And if, as he later said, he

liked it, why would he be writing Shelly Mayer in search of a central

character? Why wouldn’t he write Siegel, who had been so consistently supplying

good ideas to the Major’s comics? Sullivan was certainly on good terms with

Siegel (as we can tell from the letter Sullivan would write Siegel in January

1938); if he wrote Siegel, he wouldn’t be writing a stranger. Maybe Sullivan

wrote to Mayer in search of backup features for Action Comics. If he

already knew Superman would be the lead feature, he might have needed other

features. But even that explanation doesn’t dovetail with documentary evidence,

none of which mentions a need for secondary features for Action.

SULLIVAN HAD

BEEN MADE EDITOR by Donenfeld and Liebowitz, and on January 10, 1938, he wrote

to Siegel (notice that he begins with a familiar, not formal, greeting; he knew

Siegel and probably had written to him before):

“Dear

Jerry—No doubt you’re quite surprised to be hearing from me from the above

address [the office of National/Detective had moved uptown to Lexington Avenue]

... Nicholson Pub. is now in the hands of receivers, ... due to the taking over

of the publication by Detective Comics by the firm to which Mr. Liebowitz is

business manager, etc.

“I

have on hand now several features you sent to Mr. Liebowitz. ... the one

feature I liked best, and the one that seems to fit into the proposed schedule

is that ‘Superman.’ With all the work Joe [familiar reference] is doing now

[for Fun and New Adventure] could it be possible for him to still

turn out 13 pages of this new feature ... for the new magazine? Adding another

13 [pages] to his already filled schedule is loading him up to the neck. Please

let me know immediately whether or not he can do this extra

feature.”

Apart

from the core message—Sullivan wanted Superman for the first issue of Action—the

letter tantalizes with random bits of news and some questions. First, Siegel

had sent Superman to Liebowitz—perhaps in response to Gaines’ recommendation?

But according to Liebowitz’s unpublished memoir, he got the Superman strips

from Gaines. Or maybe Sullivan is simply short-circuiting the actual

sequence—Superman to Gaines, Gaines to Liebowitz, hence Siegel sent it to

Liebowitz but by a circuitous route. “Several features”? Would those be the

concepts Siegel outlined in his letter of December 6?

Second,

if National/Detective was “in the hands of receivers,” did that mean the Major

could not remain “actively involved” with the company as his son believes he

was?

Siegel

and Shuster doubtless had mixed emotions when they read Sullivan’s letter. All

along, they had hoped to get Superman into newspapers not into comic books. But

the Major’s initial thinking that his comic books were catalogues offering

strips for newspaper syndication no doubt hovered in the backs of their minds.

Says Daniels: “They still believed that comic book publication might be the

route to newspaper syndication, and they knew that the new owners of Detective

Comics, Inc., were far more solvent than Wheeler-Nicholson. The new offer

seemed like the way to go, and they agreed to turn out thirteen pages of

Superman.”

In

response, on February 1, Sullivan shipped off to them the Superman strips; on February 4, he fired off another epistle, urging speed: “Shoot the

works, PRONTO! Those thirteen pages will have to be in the office here within

three weeks’ time. ... Regards to Joe and make this first release (and the

others, too) the very best ... the initial issue of any magazine should be

without imperfections.”

Three

weeks to produce thirteen pages may not seem like so herculean a task (less

than a page a day, and they had the first adventure “storyboarded” in the comic

strip version), but Shuster was also doing other features for National. To save

time—and to respond to Sullivan’s sense of urgency—Shuster and Siegel decided

to use the art in the comic strips: they cut the panels apart and pasted them

up in comic book page format, sometimes cropping panels or extending the art to

make them fit into the perfectly rectangular grid.

(Shelly

Mayer, incidently, often claimed that he did the cutting and pasting, another

sign of his eagerness to be a part of what would become a watershed event in

the history of comic books. On the GCD Chat List in 2001, Mike Catron

speculated that Mayer was remembering work he did on Superman No.1;

early issues of that title “contained reprints of the Superman comic

strip.” A couple days later, however, Catron went through the first issue of Superman, page by page, identifying the sources of each, and concluded that none of

the newspaper Superman strip found its way into Superman No.1.

But, quoting Jim Steranko, who noted that the second issue of Superman contained newspaper strip reprints, Catron decided that Mayer was remembering those paste-ups—which, Catron allows, Mayer probably thought were for Superman No.1 (and in later years confused with Action No.1) but which ended up

in Superman No.2. A nice save for Mayer’s reputation as an industry

giant.)

Ricca

treats the reconfiguring operation as a monumental undertaking, but he has

displayed throughout the book a penchant from dramatizing incidents—including a

generous helping of child and adolescent psychology in fleshing out the story

of Siegel’s youth and Shuster’s. The early chapters in the book are novelistic

rather than documentary.

The

story that wound up the lead feature in Action Comics No.1 is a headlong

dash of action, beginning with Superman leaping through the night air carrying

a bound and gagged woman to the governor’s mansion in order to win the release

of another woman, who is innocent of the crimes the woman under Superman’s arm

has committed. Superman barges into the governor’s quarters, ripping doors off

their hinges, and persuades the governor that the wrong woman is about to be

executed. This episode, Jones opines, is a fragment from the more lurid version

of Superman that Siegel and Shuster tailored for men’s magazines.

In

the rest of the inaugural tale, Superman beats up a wife-beater, takes fellow

reporter Lois Lane out for dinner and dancing as Clark Kent, rescues her from a

gang of kidnaping hoodlums as Superman, and tackles corruption in the nation’s

capital. The relationship between Clark and Lois, her ignoring him as a wimp

and his doing better reporting on important stories, is broached, promising

more lively times ahead.

With

that, Superman was on his way to iconic status in American culture. In response

to the character’s startling newsstand popularity, the Superman title

was assembled to hit newsstands in mid-May 1939—the first comic book devoted to

the exploits of a single character. At this point, Gaines emerges as the mover

and shaker for Superman.

The

production of at least the first issue of Superman was supervised by

Gaines, who dictated content, virtually page by page. Daniels quotes from

Gaines’ March 27, 1939 letter to Siegel: “We have decided that for the first

six pages of the Superman book, we would like you to take the first page

of ‘Superman’ which appears in Action Comics No.1 and, by elaborating on

this one page, using different ideas than those contained on this page, work up

two introductory pages.”

Gaines

also specified a page that would offer “Scientific Explanations of Superman’s

Amazing Strength” and “four pages of a thrilling episode which results in

Superman becoming a reporter.”

With

a desk at McClure Syndicate, Gaines was also chiefly responsible for the

syndication of the comic strip incarnation that debuted just a few months

before, on January 16. Once the newsstand success of the character had been

determined, Gaines easily persuaded McClure to take on the feature. But it

wasn’t exactly that mythical newsstand survey after the fourth issue of Action

Comics that swung the deal.

Gaines

and Donenfeld knew well before then that they had a hit on their hands. Tye

explains that magazine distributors and newsstand dealers kept an eye on sales

from the start, particularly with a new title. Twice a month—fifteen days after

the magazines were delivered and again at the end of that month—dealers counted

the books on display and reported the numbers sold to the distributor, using

penny postcards that the distributor had left behind for the purpose. It was a

crude method, fraught with hit-or-miss pitfalls, but it was supported by the

more exact tally that was made when delivery trucks picked up unsold magazines

as they delivered the new issue.

Even

after the first issue of Action Comics, Donenfelt and Liebowitz knew the

title was a success: the first issue sold 64 percent of its print run, and

anything over 50 percent guaranteed a profit.

According

to Tye, they ran that in-magazine questionnaire in No.4 simply to refine their

interpretation of the meaning of the sales figures. And by even less scientific

means—sending “agents around Manhattan to check demand at kiosks and

drugstores”—they’d determined that Superman was the likely reason for the

title’s success. Maybe this haphazard “survey” produced the legendary anecdote

about hoards of youngsters asking for “the magazine with Superman in it.”

In

any event, the results of the fourth issue’s questionnaire confirmed the

publisher’s suppositions. Cover-dated September, Action Comics No.4

probably hit newsstands in late July or early August. By September, Gaines had

raised the question of syndication with the officials at McClure.

Donenfeld,

as the man whose company owned the rights to Superman, was deeply engaged in

negotiating the syndicate deal. He held out for 40% of the proceeds, an

astronomical amount. Syndicates usually split the profits (net income) 50/50

with cartoonists; Donenfeld’s deal presumably left only 60% of the profits to

be shared by McClure and Siegel/Shuster. But Donenfeld held the rights and had

the leverage: Tye cites figures that show sales of Action Comics had

climbed steadily with each issue.

Before

the deal was signed, according to Kobler in his Saturday Evening Post article, Siegel and Shuster “begged Donenfeld to give back the syndication

rights” that they’d signed away the previous spring. But Donenfeld said only

that if they came to New York, he was sure “we can work something out.”

What

they worked out in September 1938 was a 10-year contract: if they agreed to an

exclusive arrangement with Donenfeld, Siegel and Shuster would get $500 for

every 13-page story in the comic books, 50% of the net (after Donenfeld’s 40%)

from the comic strip, and 5% of the take from Superman movies, shirts,

sweaters, toys and other such ancillary products. Donenfeld, meanwhile, would

get an agent’s fee of 10% of McClure’s gross (the revenue before any sharing

was done, before even Donenfeld’s 40% was siphoned off).

Clearly,

Siegel and Shuster were being taken to the cleaners. Kobler speculates that for

the first year of the contract, the creators enjoyed “an increase of less than

$100 a month.” By 1942, the strip was in 285 newspapers nationwide according to

Tye. Siegel and Shuster made good money over the next ten years, but Donenfeld reaped

the bonanza. His cut in 1940 was $100,000. Kobler said Siegel and Shuster were

splitting $75,000 in 1940. Tye quotes Siegel as saying the two were sharing

only $38,000, but “even at the lower figure, he was earning $307,000 a year in

today’s dollars.” (And it’s likely, since $38,000 is about half of $75,000,

that Siegel meant his share was $38,000 not that he and Shuster were sharing

$38,000.)

Ancillary

income began almost at once. The Superman radio program started February 12,

1940. (Ominously, a couple of months later, in May 1940, the literary editor of

the Chicago Daily News, Sterling North, wrote a column about the

“national disgrace” he saw in comic books—that depicted in crude colors all

sorts of violence, bringing on the “cultural slaughter of the innocent” (young

readers)—accusing Superman of launching a cult of “bully worship.”) Animated

Superman cartoons started in September 1941.

And

that brings us to the close of the inaugural days of Superman: he’s a success

as a comic book hero and he’s starring, at last, in his own syndicated

newspaper comic strip; and Siegel and Shuster have reasonably secure jobs in

their chosen field. More entanglements and grievances ensued, but I won’t

explore them here. You can find them in Daniels, Jones, Tye and Ricca. Here,

I’m concerned chiefly with finding someone to crown with the laurels of

discovering Superman. Having surveyed the half-dozen years of Superman’s

gestation, let’s return to the question we started with: who is his discoverer?

Who among the several candidates saw the Siegel-Shuster creation and thought it

worthy of publication?

IN HIS

ACCOUNT, Les Daniels credits Liebowitz with an assist from Gaines. Larry Tye

says Liebowitz found Superman in Gaines’ slush pile, but he acknowledges that

Major Wheeler-Nicholson yearned to publish the Man of Steel earlier. Gerard

Jones gives the palm to Mayer and Sullivan but with the Major hovering in the

background (and he says it was Donenfeld who was working with Sullivan to

assemble material for the first issue of Action Comics). Brad Ricca

promotes Gaines and Donenfeld. Douglas Wheeler-Nicholson claims, without

equivocation, that his father, and only his father, was Superman’s discoverer.

Based

upon the number of credits accumulated, Gaines and Liebowitz seem good

candidates. But the Major beats them both by one more credit. Votes, however,

are not a reliable basis for making a final determination. For a more

dependable resolution, we should turn to documents. Few documents exist; and

none that support either Shelly Mayor or Vin Sullivan as Superman’s discoverer.

The documents we have—all letters from and to various parties—unhorse the

legend completely. And the earliest document recognizing by name the potential

of Superman is the Major’s October 1935 letter. Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson

is clearly the discoverer of Superman.

Some

of the other claimants, however, have legitimate and significant places in the

story. Relying chiefly upon the documents we have, we can fill in a few blanks

with reasonable supposition and construct thereby a narrative of discovery that

knits together several otherwise contentious strands. Neither Mayer or Sullivan

figure significantly in the narrative, but Gaines does.

By

the time he wrote Siegel in November 1937 about the tabloid possibility for

Superman, Gaines had seen Superman several times and probably entertained the

notion that the strong man from space could make a good comics feature.

(Otherwise, why write Siegel about the tabloid possibility?) When the tabloid

scheme fell through, Gaines could very well have urged Siegel to take Superman

to the Major. Although Ricca says Gaines wrote Siegel to this effect, he

doesn’t quote a letter, and a letter may not exist.

If,

as Daniels reports, Siegel went to New York and visited National Allied’s

offices in December 1937, that may have been when Gaines made his suggestion;

it may have been made in person rather than in writing.

Visiting

National may not have been the reason for Siegel’s trip: he may have gone to

New York to meet with Gaines about the tabloid plan. When he got to Gaines’

office, Gaines had the unhappy chore of telling the young man that the tabloid

option had evaporated. Seeking, perhaps, to assuage Siegel’s disappointment,

Gaines may, at that time, have suggested that Siegel take Superman to the

Major, to National. And Siegel may have done exactly that—visiting National’s

offices, as Daniels claims.

Siegel

knew that the Major wanted Superman, but he’d been reluctant to give the

character to the Major because of the Major’s wobbly financial history. Gaines

may have told Siegel that Liebowitz was now running things at National and that

consequently there would be no financial worries.

After

visiting with Liebowitz at National, Siegel may have decided to offer Superman,

asking Gaines to send over the Superman strips he had, plus whatever he had in

his slush pile from Siegel and Shuster. Then when he got back to Cleveland,

Siegel wrote to Liebowitz on December 6 with other ideas for features for Action

Comics. Subsequently, Sullivan, acting as Liebowitz’s editor, wrote to

Siegel, announcing Liebowitz’s decision to accept Superman. Sullivan doesn’t

mention the Major in this letter (or, at least, in as much of it as has been

quoted) nor does he allude to any previous discussions about Superman. But he

surely knew of the Major’s interest in Superman: if Superman had been a topic

of discussion around the Wheeler-Nicholson family dinner table in the fall of

1937, the Major would undoubtedly have mentioned the feature to Sullivan that

fall. Or so it would seem. Sullivan, after all, was the Major’s editor.

Based

upon his early championing of the character, the Major is clearly the

discoverer of Superman. But Gaines undoubtedly played a major role in getting

the character into print.

We

can conjure into this narrative a place for Mayer that echoes his own

statements—but without any documentation. He may well have liked Siegel’s

earliest Superman submission to Gaines and therefore promoted it to his boss,

raising Gaines’ consciousness about the feature. And when Siegel told Gaines in

December 1937 to send Superman over to National, it’s reasonable to suppose

that Gaines directed his assistant, young Mayer, to scoop up the Siegel-Shuster

stuff and send it over. As a former employee at National, Mayer knew Sullivan

and would doubtless have sent the Siegel-Shuster material to him. This

scenario, entirely speculative, supports the main outlines of the legend. No

document that I’m aware of supports this contention, but it is reasonable to

suppose that events transpired as I’ve just outlined them—making a place in

comics history for Mayer.

Sullivan

also enjoys a place in that history as editor of Action Comics—but only

as editor; not exactly the role he remembers for himself. He claims to have

written Mayer asking for any discards in the McClure slush pile. But no such

letter surfaced in any of the accounts I consulted. Moreover, if the Gaines

thread about urging Siegel to send Superman to National is accurate, Sullivan’s

letter would be superfluous. Ditto Liebowitz’s claim to have written Gaines the

same kind of letter. (In another niche of the narrative, however, Gaines’

recommendation to Siegel to send Superman to National may have been prompted by

a phone call from Liebowitz at National.)

Attempting

to wedge into Superman’s advent story as many of the errant fragments as

possible makes room for nearly everyone involved, however subsidiary their

roles may have been in actuality. But reality is often more messy than we’d

like it to be. It seems beyond dispute, however, that Major Malcolm

Wheeler-Nicholson is the first to have seen Superman as a creation worthy of

publication and to have been in a position professionally to have acted on his

opinion. The Major is the discoverer of Superman. If anyone who has waded

through this swamp of contradictory contentions has another version of the

events I’ve tried to knit together into a single narrative, I’d love to hear

it.

Return to Harv's Hindsights |