|

Steve Ditko,

1927 - 2018

The

Uncompromised

STEVE DITKO,

DUBBED THE J.D. SALINGER OF COMICS, who has not been seen or heard in public

for 50 years, died as obscurely as he lived. They found his body in his

Manhattan apartment on June 29, but authorities said he’d been dead for a

couple of days. He was 90. He’d left Marvel and the iconic characters he

created there when he was 39.

Ditko,

along with the artist Jack Kirby and the writer and editor Stan Lee, was a central player in a seminal period in the history of comic books— the

1960s cultural phenomenon of creating the Marvel Universe, whose characters

today are ubiquitous in films, television shows and merchandise.

"Comics

are unimaginable without his influence," tweeted Patch Zircher, a

comic-book artist who has worked on Batman and Superman for DC Comics. "He

co-created Spider-man, which will be remembered as significant as Doyle

creating Sherlock Holmes or Fleming creating James Bond. Spider-man may outlast

them both."

One

of the most popular superheroes ever conceived, said Ellis Clompton at

variety.com, Spider-Man generated over 360 million book sales total since his

debut in 1962.

"Thank

you Steve Ditko, for making my childhood weirder," fantasy and graphic

novel author Neil Gaiman said in a series of tweets to his 2.7 million

followers. "He saw things his own way, and he gave us ways of seeing that

were unique. Often copied. Never equaled. I know I'm a different person because

he was in the world."

Edgar

Wright, director of movies including "Baby Driver" and "Shaun of

the Dead," said on Twitter that Ditko was "influential on countless

planes of existence."

English

TV and radio host and comic books super-fan Jonathan Martin tweeted that Ditko

was "the single greatest comic book artist and creator who ever

lived."

The

best—most extensive and detailed—treatments of Ditko’s life and work are Andy

Webster’s obit for the New York Times (to which Sandra W. Garcia

contributed) and Michael Dean’s for the Comics Journal at tcj.com; Dean

offers the most detailed bibliographic account. I’ll be using Webster’s article

as the basis for my appreciation of Ditko, adding (in italics when not

otherwise indicated) scraps and squips from other obituaries and my own

comments. But I’ll begin with Dean’s opening—:

Stan

Lee, in his credits for The Amazing Spider-Man, called the artist

“Swingin’ Steve Ditko” (issue No.10) and later “Scowlin’ Steve Ditko” (issue

No.27), but if you had to choose one adjective to attach to Ditko’s name, it

might be “Uncompromising.”

Consider

these facts:

■

At a time when Marvel cultivated a house look based on Jack Kirby’s muscular

explosiveness, Ditko stuck to his own style — all rubbery sinews and urban

shadows. In an extreme version of the famous Marvel Method, Ditko said he told

the stories visually, often with little or no input, inventing villains and

situations, which Lee retroactively scripted. When communications broke down

between the artist and writer, Ditko simply walked away without explanation.

■

Ditko’s independent Mr. A comics for Wally Wood’s witzend magazine in 1967 expressed his objectivist philosophies in bluntly abstract

scenarios, even though they had little appeal for most young comics readers and

were out of sync with countercultural ideologies of the time. He continued to

draw Mr. A for more than 50 years.

■

When Renegade Press publisher Deni Loubert accepted an Inkpot Award on

Ditko’s behalf at the 1987 San Diego Comic-Con, Ditko was reportedly outraged

and insisted that she return it.

■

Plans for a late 1990s comics series to be written and drawn by Ditko and

published by Fantagraphics were scuttled after the first issue when Ditko took

offense at a coloring mistake on the cover. Offers to make amends by printing

the art with the correct coloring in a later issue were rejected by Ditko, who

refused to do any further issues.

■

In 2007, a BBC documentary, “In Search of Steve Ditko,” tracked Ditko down to

his New York apartment but could not coax him to appear on camera or be

interviewed. Although Spider-Man co-creator Lee made a career of being in the

public eye, Ditko gave no interviews after 1968, turning down even a request

from his hero, Will Eisner.

■

He declined to cooperate with Blake Bell’s 2008 Ditko biography Strange

and Stranger: The World of Steve Ditko, calling the book, sight unseen, a

“poison sandwich,” and turned the biographer away from his door, as he had many

journalists over the years.

■

When prominent novelist Jonathan Lethem asked to include a Ditko story in the

2015 volume of The Best American Comics, Ditko turned him down.

■

Despite living a Spartan existence eking out a meager living his final years,

he refused to sell his original art, which would have been worth hundreds of

thousands of dollars. Small-press publisher Greg Theakston told of

finding the artist using original Ditko art from 1958 as a cutting board.

Some

of the mysteries about Steve Ditko we’ll try to sort out as we next wander through

Webster’s New York Times article; the rest, alas, will be buried with

the artist.

THOUGH DITKO

HAD A HAND in the early development of other signature Marvel characters —

especially the sorcerer Dr. Strange — Spider-Man was his definitive character,

and for many fans he was Spider-Man’s definitive interpreter. Ditko was noted

for his cinematic storytelling, his occasional flights into almost psychedelic

abstraction, and the philosophical convictions that often colored his work.

Scrupulously private, he had a mystique rare among industry superstars.

The

initial visual conception of Spider-Man did not come from Ditko. According to

Bell, that image came from Kirby, who penciled an origin story for the Marvel

title Amazing Fantasy in 1962 (although Kirby’s Spider-Man was much

too muscular for the incipient teenage superhero).

Writing

in Robin Snyder’s The Comics, a "first-person history"

newsletter of comics, Ditko gives his version of the story—:

"For

me, the Spider-Man saga began when Stan called me into his office and told me I

would be inking Jack Kirby's pencils on a new Marvel hero, Spider-Man. I still

don't know whose idea was Spider-Man."

Ditko

refers to Lee's interview of a previous year on "Larry King Live"

during which King reminded us of Lee's claim that he started thinking of a

spider when he saw a fly on the wall.

"You

know," Lee said, "I've been saying it so often, for all I know it

might be true." (Later in that interview, by the way, Lee insists that he

was always assisted in the creation of Marvel heroes by the artists he worked

with; but “always” wasn’t true in the early years of Marvel’s ballooning

popularity when Lee was repeatedly interviewed by reporters.)

Ditko

continues: "A leap from a fly to a spider is like from man to a cannibal.

Stan never told me who came up with the idea for Spider-Man or for the

Spider-Man story that Kirby was pencilling. Stan did tell me Spider-Man was a

teenager who had a magic ring that transformed him into an adult hero —

Spider-Man. I told Stan it sounded like Joe Simon's character, The Fly

(1959), that Kirby had some hand in, for Archie Comics. Now here is a

fly-spider connection. ... Stan phoned Kirby about The Fly; I don't know what

was said in that call."

Later,

the Kirby-pencilled pages were discarded— and so were the magic ring idea and

the notion that Spider-Man would be an adult. Had the original plan been

followed— if Ditko had said nothing about The Fly— what sort of Spider-Man

might have emerged, Ditko asks. Then answers:

"There

would be lots of nots: Not my web-designed costume, not a full

mask, no web-shooters, no spider-senses, no spider-like

action, poses, fighting style and page breakdowns, etc." As far as I'm

concerned, Ditko has made his case: he had more to do with the creation of Spider-Man

than anyone else.

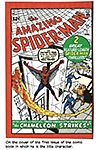

DITKO RAN WITH

THE CHARACTER (Webster takes up the story again). Spider-Man made his debut

that year (1962) in Amazing Fantasy No.15, and the character’s

popularity led to his own title, The Amazing Spider-Man, which Ditko penciled,

inked and largely plotted from 1963 to 1966. He began to get a credit-line

for plotting with No.25. But Stan Lee, the public face of Marvel Comics, often

took all the credit in the early days of the Marvel revival of the industry.

Not

to fault Lee. As I mentioned a couple paragraphs ago, the people he told that

he created Spider-Man were newspaper and magazine reporters, and in those early

days, publicity for comics was hard to come by (except for hold-over criticism

of funnybooks as primers for criminals), so Lee, understandably, telescoped the

creation story in order to get on to other aspects of the business and its

promotion that he deemed more important. Later in his career, Lee usually

credited Kirby and Ditko as “co-creators,” and, even later, he would give them

the larger billing in establishing the characters.

I

also lately discovered that Ditko’s influence on the Spider-Man comic book

began at the very beginning, quoting now from my Rants & Raves, No.303, wherein I

report on my examination of the original art of the first Spider-Man story at

the Library of Congress)—:

Judging

from the evidence at hand [i.e., the original art pages], Ditko submitted his

work to Lee in its penciled state. In this inaugural two-part Spider-Man tale,

Lee asked for three adjustments, two of which would have required re-drawing a

panel or whiting-out offending visual elements. But the original art for the

pages I contemplated featured no paste-overs and no white-out, which would have

been visible if the adjustments had been made after the art had been inked. So

Lee was looking at the penciled pages, which Ditko adjusted according to Lee’s

directions when he inked. Or, as it happens, did not adjust.

Lee

made his suggestions in pencil in the margins. The notes have been erased but

they are still discernable. The first one occurs on page 3 of Part One. The

eighth panel shows a speeding automobile that almost runs over Peter Parker

because he is so absorbed in thought that he is oblivious to his surroundings.

The penciled art apparently included an arm protruding from the interior of the

car, and that, Lee thought, implied that the car was being driven recklessly,

so he asked Ditko to remove the arm so as not to suggest to young

impressionable readers that reckless driving was acceptable. And Ditko removed

the arm, as we see in the accompanying illustration.

On

the last page of Part Two (shown nearby with page 3), Lee’s comment focuses on

the sixth panel. Here, he asks that Ditko “lift up” the second policeman’s

head. In the original, apparently the second cop’s head is lower down in the

panel—or perhaps just smaller. “Lifting it up” enhances its visibility, and

Ditko may have complied with the suggestion although the head remains pretty

small, so maybe he didn’t.

But

the other comment Lee made, his third instruction, Ditko ignored. On page eight

of Part Two, Lee’s penciled comment is next to the third panel: “Steve, omit

crook! Show door slamming!” Ditko quite sensibly ignored this command.

He

probably ignored it because omitting the crook would remove the visual interest

in the panel: a vertical line indicating closed elevator doors is scarcely a

dramatic picture, and the scene demands some drama, coming, as it does, at the

end of a presumably heated pursuit.

Ditko

may also have realized that the crook’s face, which establishes his identity at

the end of the story (look again at the previous visual aid), needs a little

more exposure than even the close-up of the next panel supplies. The figures of

the crook in both second and third panels are small, but the heavy eyebrows

provide a quick and certain means of identifying him. The profile in the fourth

panel confirms in detail the distinctive eyebrows, but profiles, as a general

rule, are not useful in identifying anyone except in profile; and the crook at

the end does not appear in profile.

Without

page eight’s several exposures of the crook’s face, including the detailed

profile, we might not be equipped to share Spider-Man’s moment of recognition

at the end, and the story with its heart-rending moral lesson would be

substantially spoiled. Ditko was right to ignore Lee’s dictum here.

Judging

solely from this instance—perhaps the only “documentary evidence” we have—Lee,

as editor and scripter, influenced how Ditko told the story that Lee plotted,

but Ditko did the actual storytelling, enhancing its emotional highs and lows,

and he didn’t always do what Lee wanted him to do. Ditko is clearly the better

visual storyteller; Lee’s advice here is either off the mark or almost

superfluous. (End of reprise of No.303 report, but bear it in mind when we

re-visit the question of who did what on Spider-Man.)

UNLIKE SUPERMAN

OR BATMAN (characters from Marvel’s chief rival at the time, National

Periodical Publications, which later became DC Comics), Spider-Man had

humanizing flaws. He was hounded, Webster continues, not praised, by the press

and the police. In his secret identity as Peter Parker, he was mocked by his

peers. And he struggled with guilt over his uncle’s death, which he felt he

could have prevented (as we’ve just seen), and fretted about his frail and

aging aunt.

Teen

superheroes, as Calvin Reid observes at publishersweekly.com, were usually

sidekicks to other superheroes. But “Spider-Man, along with his alter ego,

teenage prodigy and news photographer Peter Parker, was something different for

a new generation of comics fans. Wracked by teenage problems of isolation,

insecurity and social rejection, Parker lived at home in Queens, New York with

his aunt May, and seemed to always be scraping to make money. ...

“Ditko’s

drawings of Spider-Man’s high-flying antics were dynamically rendered— Spidey’s

bodily actions were anatomically precise as well as kinetic, his arms and

legs gesticulated in ways evocative of a spider’s movements— and his fight

scenes were meticulously choreographed and so cinematically rendered, the

characters seemed to move right across the page.”

Webster

agrees: Spider-Man’s fight scenes and aerial acrobatics had a spry kineticism

that contrasted with the brawny physicality of Kirby’s compositions. Spider-Man,

unlike the thunder god Thor and other signature Kirby characters, was not

musclebound; he was a slender teenager. While Lee’s dialogue for Spider-Man

could be buoyant, peppered with wisecracks, Ditko lent mood in his pictures.

Spider-Man’s

mask, obscuring his entire face, and his web-textured costume had a slightly

morbid aspect. Spider-Man’s pensive moments — when Peter agonized over

sacrifices his alter ego had demanded of him, for example — echoed the

psychological struggles in Ditko’s earlier horror comics.

Ditko

also helped conceive famous villains, Webster goes on, like the Green Goblin

and Dr. Octopus, and supporting characters.

STEPHEN DITKO

WAS BORN on November 2, 1927, in Johnstown, Pa. His father, also Stephen, was a

steel-mill carpenter; his mother, Anna, was a homemaker. His father bequeathed

to his son a love of newspaper strips like Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant, and the young Stephen devoured Batman and Will Eisner’s noirish Sunday

newspaper insert, The Spirit.

Young

Steve was an only child for his first seven years, Dean notes, “but was

eventually joined by two brothers and two sisters. In high school, he was a

member of the science club and a club devoted to carving model planes to aid in

the training of enemy-plane spotters. Upon graduating in 1945, he did a stint

in the Army, during which he was stationed in postwar Germany, drawing cartoons

for the military newspaper. During this time, he produced a monthly comic book

and mailed it to an audience of one: his brother Pat.

“After

returning to civilian life, Ditko enrolled in New York’s Cartoonists and

Illustrators School (today known as the School of Visual Arts), where he

studied under Batman artist Jerry Robinson. One of his classmates was

future bondage cartoonist and photographer Eric Stanton, with whom Ditko

would share a studio from 1958 to 1968.”

Robinson

said he was impressed by Ditko: “He put in the hard work and tried to

participate in our discussions on anatomy, perspective, drapery—you name it.

Steve was very creative and a very good craftsman. I think I might have had

something to do with influencing his storytelling because that’s what I

emphasized in my class. I tried to teach the students how to think about the

comic, what they wanted to do with it, and that drawing was the tool. I think I

made him a good storyteller. He showed so much promise I recommended him for a

second year. He was in my class for two years, four or five days a week, five

hours a night. It was very intense.”

Ditko’s

first work in print was in early 1953, said Webster, in a romance comic from a

minor publisher.  For three months he worked in the studio of Kirby and Joe Simon, the creators

of Captain America, before heading to Charlton Comics, which had its

headquarters in Derby, Connecticut. Charlton offered low pay and inferior

production values but creative freedom, and Ditko would return there often over

his career. During his first tour there, he would create 170 pages and 19 covers

in less than a year, despite suffering from the onset of tuberculosis, which

would sideline him for a year beginning in 1954. For three months he worked in the studio of Kirby and Joe Simon, the creators

of Captain America, before heading to Charlton Comics, which had its

headquarters in Derby, Connecticut. Charlton offered low pay and inferior

production values but creative freedom, and Ditko would return there often over

his career. During his first tour there, he would create 170 pages and 19 covers

in less than a year, despite suffering from the onset of tuberculosis, which

would sideline him for a year beginning in 1954.

The

introduction of the Comics Code Authority — a regulating body established by

the industry in 1954 in response to Senate subcommittee hearings into the

supposed influence of comics on juvenile delinquency — stifled Ditko’s Charlton

output, which had largely covered horror, crime and science fiction.

Influenced

by the artist Mort Meskin, a specialist in mood and noirish textures,

Ditko had infused his pre-Charlton work with a sweaty anxiety and recurrent

motifs of paranoia.  In “In Search of Steve Ditko” — a 2007 British documentary narrated by

the TV personality Jonathan Ross — the novelist and comic book writer Alan

Moore says that in Ditko’s work there was “a tormented elegance to the way

the characters stood, the way that they bent their hands.” In “In Search of Steve Ditko” — a 2007 British documentary narrated by

the TV personality Jonathan Ross — the novelist and comic book writer Alan

Moore says that in Ditko’s work there was “a tormented elegance to the way

the characters stood, the way that they bent their hands.”

He

added, “They always looked as if they were on the edge of some kind of

revelation or breakdown.”

In

1954, tuberculosis forced Ditko back to Pennsylvania, where he nearly died.

After a year, he returned to New York, where he approached Lee, at the time a

writer-editor for Atlas Comics, a precursor to Marvel.

Lee,

impressed with Ditko’s speed and proficiency, hired him. Atlas’s horror line,

emasculated by the code, became largely divided between Kirby’s stories,

starring generic monsters with names like Groot and Fin Fang Foom, and Ditko’s

agonized character studies.

Cutbacks

at Atlas brought Ditko back to Charlton, where he and the writer Joe Gill

created the nuclear-powered Captain Atom, before returning to what was now the

Marvel Comics Group. Marvel was in a rebirth, starting with the publication of

the Fantastic Four in 1961, and continuing with Thor and the Hulk.

Spider-Man

debuted in 1962. Kirby drew the cover of his debut, but for three years the

character was Ditko’s baby.

Ditko

helped develop other Marvel superheroes, including Iron Man and the Hulk. Of

these, probably his best-known, besides Spider-Man, was Dr. Strange, a “master

of the mystic arts,” who first appeared in 1963 in Strange Tales No.110. Even Lee conceded that Dr. Strange was Ditko’s creation: “Twas Steve’s

idea,” he once said.

For

Dr. Strange’s occult adventures and battles in alternate dimensions, Ditko

created foreboding expanses of abstract shapes and patterns, ruled by evil

sorcerers and supernatural entities. “Strange is as straight-faced a hero as

they come,” says Dean, “but ... Lee’s goofy necromantic wordplay (the Eye of

Agamotto, the Seven Bands of Cyttorak) keep things from become too dour.”

Ditko

continued with Dr. Strange for 36 issues, ending in July 1966.

But

it was with Spider-Man that Ditko flourished.

MARVEL ARTISTS

GENERALLY FOLLOWED the “Marvel method,” said Webster, in which artists built on

Lee’s synopses and were encouraged to emulate Kirby’s outsize style. Lee

would provide a plot outline (sometimes little more than a speculative

hint—what would happen if...?), and the artists would expand upon the idea,

turning it into a visual narrative, to which, later, Lee would add dialogue and

captions). It was a method that left open to debate which of the collaborators

“created” the story. And the character. Ditko, who focused less on fight

scenes and more on Peter Parker’s psyche, thus had broad license with plotting

and drawing The Amazing Spider-Man. Many fans regard Issues 31, 32 and

33 — which climax with the superhero, after reviewing his life, triumphantly

upending heavy machinery that has pinned him — as a Ditko peak.

The

first 38 issues of The Amazing Spider-Man proved to be Ditko’s most

enduring success, says Dean, continuing—:

Even

today, Spider-Man movies and comics are still trying to find their way back to

the combination of elements that Ditko instilled in the series: the youthful

exhilaration and aerial ballet of Peter Parker giving vent to his web-swinging

powers, the down-to-earth subjective point of view of a troubled adolescent,

the smoothly paced storytelling.

How

much of the character can be attributed to Ditko and how much to Lee has been

the subject of endless debate. Even Jack Kirby had a claim, having drawn the

first cover and an earlier unused Spider-Man character design and partial story

at Lee’s direction. But it was undeniably Ditko who established the look and

feel of the series as it was published. The Marvel Method gave him considerable

leeway to develop characters and storylines, and this was especially true as

Lee gradually abandoned his pre-penciling story conferences with Ditko.

When

Lee later referred to himself in interviews as Spider-Man’s creator, Ditko

objected. In Sean Howe’s Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, Lee recounted

a conversation in which Ditko told him, “Having an idea is nothing because

until it becomes a physical thing, it’s just an idea.’”

Lee

responded by arguing that “the person who has the idea is the person who

creates it.” Unless you believe that what made the first Spider-Man comics

great was that they were about a kid who gets bitten by a radioactive spider

and gains arachnid powers, then Ditko’s point seems valid. We readers didn’t

fall in love with a synopsis; we were captivated by the way Lee and Ditko

brought the idea to life.

Ditko’s

work on Spider-Man with Lee was less a collaboration than a dialectical

collision.

According to Marvel writer/editor Roy Thomas, Lee and Ditko disagreed on

just about everything, from aesthetics to politics. But it was a collision that

made possible a uniquely affecting comic book. Lee conceived the teenage,

high-school milieu but Ditko protected that world from Lee’s more fanciful,

cosmic ideas, arguing that Spidey’s villains should be rooted in the streets of

New York. The Amazing Spider-Man combined Ditko’s story pacing,

character design and wiry movements with Lee’s self-aware dialogue, Ditko’s

interiorized existential dilemmas with Lee’s trademark tension between the

ordinary and the extraordinary.

Years

later, in 1999, Lee issued an open letter to the press stating: “I have always

considered Steve Ditko to be Spider-Man’s co-creator. … I write this to ensure

that Steve Ditko receives the credit to which he is most justly entitled.”

Ditko,

in a 2002 essay printed in his Avenging World collection, dismissed the

gesture, drawing a distinction between considering Ditko to be

Spider-Man’s co-creator and avowing that Ditko is Spider-Man’s

co-creator.

On

the face of it, Ditko’s position seems to be absurdly contrarian. But maybe

Ditko understood that Lee made the statement not so much because he believed

Ditko was co-creator, but because, as he said in Marvel Comics: The Untold

Story, “Steve definitely felt that he was the co-creator of Spider-Man. …

So I said fine, I’ll tell everybody you’re the co-creator.”

DITKO’S

CONCEPTION of the series, says Webster, had been shifting, increasingly

influenced by Ayn Rand’s libertarian philosophy. Spider-Man’s villain the

Looter was named after Rand’s term for those leeching from the creative elite,

phrases like “equal value trade” crept into Parker’s words, and he voiced

resentment toward student protesters. (Lee, in speaking engagements on college

campuses, found himself in the awkward position of having to explain to irate

young audiences that such a stance was Ditko’s, not his own, as Ditko did

more and more of the Spider-Man stories, dialoging as well as drawing.)

Ditko

bristled at being denied royalties when Spider-Man had his own animated ABC

television series and was used in product tie-ins. He left Marvel in 1965 (Spider-Man No. 38 was his final issue) and worked for other publishers

before returning to Charlton.

Andy

Lewis at hollywoodreporter.com speculates that Ditko left Marvel “over a fight

with Lee, the causes of which have always remained murky. The pair had not been

on speaking terms for several years. Ditko never explained his side, and Lee

claimed not to really know what motivated Ditko's exit.

“The

best explanation suggests Ditko was frustrated at Lee's oversight and his

failure to properly share credit for Ditko's contributions to Spider-Man and

Doctor Strange. The charismatic Lee was always the face of Marvel Comics, but

Ditko (and Jack Kirby) thought Lee was more interested in self-promotion than

selling the company, and, in the process, implied that he deserved the lion's

share of the credit for creating the characters in the Marvel Universe.”

Dean

allows that there are “theories galore in the comics community” about why Ditko

left. “Some say Ditko’s new objectivist philosophy clashed one too many times

with the parameters of the Marvel universe. Certainly, Lee and Ditko had ceased

to work together. Ditko constructed his stories visually and Lee interpreted

them verbally, with neither creator consulting the other. The conflicts

reportedly stemmed from Ditko’s relationship with Goodman, who Ditko felt, owed

him merchandising royalties. The problems between Lee and Ditko might be

attributable to the fact that each served a different master, Lee obliged to

carry out Goodman’s directives and Ditko loyal to Rand and her view of the

world.”

Ditko

pursued Randian notions further, said Webster, picking up the narrative—

particularly with Mr. A, a character he

created for Wood’s witzend, a

black-and-white comic aimed at adults and unconstrained by the Comics Code. Mr.

A, attired in a white suit and conservative hat, was named after “A is A,” the

idea in Rand’s Atlas Shrugged that there is one unassailable truth, one

reality, and only white (good) and black (evil) forces in society. Unlike

mainstream superheroes, he killed criminals.

.

Back

at Charlton, Ditko created The Question, also in a suit and hat but devoid of

facial features. Like Mr. A, The Question spoke in a stilted, didactic

vernacular akin to a philosophical tract’s. (Like Captain Atom, The Question is

now owned by DC.) In 1968, Ditko said in a rare interview that The Question and

Mr. A were his favorite creations.

At

Charlton, Ditko also created Blue Beetle, reported Graeme McMillan at

hollywoodreporter.com — another insect-themed character, who in many ways

mirrored a more straight-laced, less neurotic Spider-Man — as well as The

Question and Captain Atom, all three characters who were literally ahead of

their time; all three would become successful under different writers and

artists when revived for critically-acclaimed runs at DC, while simultaneously

inspiring Nite Owl, Rorschach and Doctor Manhattan in Alan Moore and Dave

Gibbons’ Watchmen. According to Dean, Ditko refused to work on any

story that featured supernatural elements, citing objectivist principles.

For

DC itself, which Ditko joined in 1968, he created a panoply of newcomers, from

Hawk and Dove — two ideologically-opposed brothers granted powers by a

mysterious mystical force who had to work together to save the day — to Shade

the Changing Man, a former secret agent whose M-Vest allowed him to reshape

reality itself even as the political landscape around him shifted in an

ever-more-paranoid series. Another DC creation was the Creeper, a reporter crime-fighter

with a maniacal laugh whose secret identity allowed him to fight injustice

and untruth in a far more direct manner than simply writing newsstories.

Another

bout with tuberculosis derailed those series, and both Shade and the Creeper

ended within a year.

DITKO’S

AVERSION TO ATTENDING COMIC CONVENTIONS and meeting fans was well known. Early

unauthorized reproductions of his work in fanzines angered him, as did the

failure by some fanzine publishers to return originals he had lent them. By

1964 Ditko had withdrawn from the public eye, limiting exchanges to mail or

telephone. His reclusiveness, and his Randian ideas, lent his work a patina of

mystery.

The

1970s and ’80s proved comparatively fallow. Ditko’s output plummeted,

especially after Charlton’s demise in 1978. In the 1980s, there were more

stints at Marvel and DC and at the independent publisher Eclipse. However, in

1991, Ditko co-created Squirrel Girl for Marvel, who remains a fan favorite.

Even

as he receded into quasi-retirement — he never fully retired; as recently as

2016, he was still producing work that was, to all intents and purposes,

self-published with editor and friend Robin Snyder — he continued to

freelance and create new characters, according to McMillan. He returned to

Marvel to co-create Speedball and Squirrel Girl, the latter now one of the

company’s biggest successes outside of the fanboy-centric direct market. At

other publishers, he came up with Missing Man, the Mocker, Static and,

reflecting his own political views, the objectivist Mr. A.

The

one throughline that all these characters had, in addition to Ditko’s trademark

aesthetic that focused on eyes and hands to an almost fetishistic degree at

times, was that all of them were… strange. (No pun intended, McMillan adds.)

Ditko’s characters were always a little outside of the mainstream, a

celebration of the individual and the outsider even at a time when such things

were rare and superheroes traditionally aspired to be agents of the status quo.

Ditko’s creations, even those theoretically intended to be family-friendly like

Speedball and Squirrel Girl, were always just a little creepy and weird...

which is the very thing that made them memorable, and even lovable.

Throughout

the decades he worked and introduced new ideas and new characters into the

world, Ditko defied trends and followed his own off-kilter muse; he was an

auteur at a time when few existed in comics, and everyone and everything he

worked on demonstrated that. As McMillan wrote above, he was a creator ahead of

his time in terms of ideas — even Squirrel Girl took two decades from creation

to become a success, an oddly similar gap to that between the debut and

commercial peak of his Charlton characters — but also in terms of attitude.

McMillan

concludes: “Without meaning to (because his interest was always merely to do

his own thing; he was an objectivist, after all), Ditko demonstrated the value

of following your own creative impulse years before Image Comics or the

landscape surrounding it existed; without knowing it, he pointed to the future.

Comics is a lesser place without him. “

In

later years, Webster continues, Ditko created black-and-white digest-size

comics financed with Kickstarter funds and sold online. These self-published

titles, ad-free and often edited by Snyder, bore a scratchy, sometimes

pointillistic style and Randian preoccupations: rationality, “looters,”

“earners.”

In

editor/writer Snyder, Dean says, Ditko found what may have been his closest and

most enduring relationship since his studio-sharing days with Eric Stanton. Their

professional connection went back to 1983, when Snyder edited Ditko’s work on

Archie Red Circle titles like The Fly and The Mighty Crusaders.

In 1985, when Ditko left Eclipse for Charlton, Snyder again edited Ditko’s

stories in Charlton Action featuring Static. And after Charlton shut its

doors for good, Snyder oversaw Ditko’s transition to Renegade Press, working

with the artist on titles like Revolver, Murder and Static.

Their

rapport was great enough that when Renegade suspended publication in 1988,

Snyder and Ditko decided to self-publish a black-and-white collection of

Ditko’s Static stories. This was followed in 1989 and 1990 by more cheap,

black-and-white trade paperbacks mixing repackaged reprints with new material,

including The Ditko Public Service Package, a 112-page slash-and-burn

commentary on the comics industry mostly in comics form. And when mainstream

venues finally dried up for Ditko at the end of the century, these

Ditko/Snyder- published collections were the format he returned to.

UNTIL HIS

DEATH, DITKO MAINTAINED a writing studio in Manhattan, where he continued to

write and draw, though how much, and what unpublished material remains, is

unknown. He continued to be incredibly reclusive, turning down nearly all

offers to do interviews, meet fans or appear at movie premieres, reported

Lewis.

"We

didn't approach him," Scott Derrickson, director of the 2016 movie

"Doctor Strange," told Lewis. "He is private and has

intentionally stayed out of the spotlight. I hope he goes to see the movie

wherever he is, because I think we paid homage to his work."

Lewis

said comic book creator Graig Weich of BeyondComics.TV struck up a friendship

with Ditko over the last year of his life and would visit him in his Manhattan

office, where he'd find the legendary creator well-dressed and sporting a

beret, as though he had stepped out of the 1940s. Ditko continued to work on

his own creations, though he didn't share the details of them with Weich, who

recalls Ditko seeming younger than his years.

"He

wasn't 90. He seemed like a young, cool artist who happened to have an aged

body," Weich tells The Hollywood Reporter. Weich recalls asking

Ditko about his relationship with Lee, and says the artist looked down and told

him, "We're peaceful."

Weich

learned of Ditko's death when he went to visit him Friday, and the security

guard informed him of the artist's passing. The security guard also told him

that Weich was one of the few people over the past four years the artist had

allowed up into his office.

Dean

takes up the question about Ditko’s relationship with Eric Stanton, with

whom he shared a studio during his time at Marvel. He often provided inking for

Stanton’s bondage-themed, under-the-counter comics (Sweeter Gwen,

Confidential TV). Stanton told Eric Kroll (in The Art of Eric Stanton) that he would also occasionally assist on Ditko’s Spider-Man work, but denied

having any significant impact on the Marvel character.

For

his part, Dean goes on, Ditko never acknowledged doing any work on Stanton’s

comics. When asked about Stanton by Loubert and others, Ditko would shut the

conversation down.

Which

brings Dean to the final question: why did Ditko, the self-made objectivist,

who was so immune to the mores of the masses, balk at owning up to his

contributions to a few kinky comics pages? It’s a question that touches on what

may be the biggest void in public accounts of his life. Dean’s answers—:

There

is no indication that Ditko was ever intimately involved with another human

being. No marriages. No romantic flings. (A report by Will Eisner that

he had met Ditko’s “son,” was never corroborated and Eisner is generally

presumed to have mistaken Ditko’s nephew for a son.) His compulsion to sweep

his sexually themed work with Stanton under the rug may suggest a reticence

about such intimate matters. Or it may just stem from the severely

honor-bound Ditko’s determination to be discreet about his ghost work for

another artist. There was, after all, very little that Ditko wasn’t happy to

sweep under the rug.

Only

one of the accounts of Ditko’s life offered information about survivors: Ellis

Clopton says the artist is survived by a nephew.

Webster

concludes his report—:

Ditko

was inducted into the Jack Kirby Hall of Fame in 1990 and the Will Eisner Hall

of Fame in 1994. In Sam Raimi’s Hollywood feature “Spider-Man,” in 2002, the

opening credits read, “Based on the Marvel comic book by Stan Lee and Steve

Ditko.” The 2008-9 ABC animated series “The Spectacular Spider-Man” gave

similar credit.

In

2016, the Casal Solleric museum in Mallorca, Spain, presented a retrospective

of his work, “Ditko Unleashed.” That same year, Marvel Studios released the hit

film adaptation “Doctor Strange”; an opening credit read, “Based on the

characters created by Steve Ditko.”

Ditko

avoided his fans to the end. In 2014, Dan Greenfield, a writer for the website

13th Dimension, recounted reaching Ditko’s Manhattan apartment doorway in an

attempt to interview him. Ditko did not bite.

Celebrities

had slightly better luck. In the television documentary, Jonathan Ross,

accompanied by the writer Neil Gaiman, visits the Manhattan building housing

Ditko’s studio, hoping for a meeting. The two briefly receive an audience. But

on camera? Not a chance.

We

conclude with a few more of Ditko’s pictures.

Return to Harv's Hindsights |