OTTO

SOGLOW AND THE LITTLE KING

The

Silent Runs Deep

(with

an Apostrophe to Naked Ladies in Their Baths)

OTTO

SOGLOW EARNED HIS NICHE in the pantheon of cartooning by producing the first

long-running syndicated strip to employ pantomimic action. But what he really

wanted was to be an actor.  Born December 23, 1900, in the Yorkville district of New York City,

the son of a German Jewish house painter and a cook, young Otto went to P.S. 77

at 86th Street and First Avenue, then completed only a year at

Stuyvesant High School. “I had a sister,” he once explained, “—and I had to go

to work.” Born December 23, 1900, in the Yorkville district of New York City,

the son of a German Jewish house painter and a cook, young Otto went to P.S. 77

at 86th Street and First Avenue, then completed only a year at

Stuyvesant High School. “I had a sister,” he once explained, “—and I had to go

to work.”

Deferring

a dream of a thespian future, he took a succession of odd jobs—packer, shipping

clerk, dishwasher, and errand boy. At one time, he famously had a job painting

forget-me-nots on baby rattles. He also worked as a switchboard operator—but

only for two hours. Plugging away at the switchboard, he made an unholy tangle

of telephone lines, and, realizing how hopeless the mess was, he simply put on

his cap and walked out.

Throughout

all these travails, he kept his acting ambition uppermost in mind. He regularly

wrote to motion picture companies, offering his services. “Naturally, they paid

no attention because I was just a kid,” he said later. “But one day they held a

parade through the streets to a movie convention at Grand Central Palace, and I

followed it—and landed a job! They let me sell programs at the convention.”

Soon

after World War I, he enrolled in the Art Students League, where he fell under

the influence of such instructors as John Sloan, George Luks, and Robert

Henri, founders of the “ashcan school” of American art. Says Jared Gardner

in his introduction, “The American King,” to Cartoon Monarch: Otto Soglow

and the Little King: the ashcan artists “rejected the gentle soft focus of

American impressionism in favor of gritty, political, urban realism. The world

they painted (and taught their students to paint) was a world Soglow knew well:

tenements, bars, subways, and midnight streets. Soglow’s mentors pointed out a

way to bring together his creative ambitions with his own personal experiences

and observations. The childhood Soglow would fondly recall many years

later—‘gang fights with kids from neighboring streets, stealing potatoes from

vegetable stands and toasting them in cans which swung by a wire’—was the stuff

of art at the hands of Sloan and his colleagues.”

Sloan

contributed illustrations (unfunny cartoons, Gardner says) to the leftist The

Masses, for which he served on the board, and he undoubtedly encouraged

Soglow to submit drawings and cartoons in 1922 to The Liberator, successor to The Masses. Soglow’s work for this magazine, and for The

New Masses in 1926-28, was clearly ashcan inspired.  His first published

effort in a freelance illustration career, however, was earlier, for Lariat

Magazine, a cowboy pulp. His first published

effort in a freelance illustration career, however, was earlier, for Lariat

Magazine, a cowboy pulp.

“Soglow

had never been out of New York,” reported the King Features promotional booklet Famous Artists and Writers, “but his cowboys were real authentic.”

Soglow

once said he found his first job by thumbing the telephone directory and

writing down the names of all the publications. Said he: “I took a handful of

drawings and started to call on publishing houses. I started at the Battery and

worked my way uptown from there. The following day, I started from the street I

left off the previous day.”

When

he got to 34th Street, he landed a job for a publisher of cheap pulp

magazines (perhaps Lariat Magazine). “I received seven dollars for my

first published drawing,” he recalled for Jerry Robinson in The Comics. “From

then on, I decided to become a cartoonist.”

By

1925, when Soglow joined the art staff at the New York World, he had

abandoned illustration in favor of cartooning. At the World for about a

year, he produced a series of satiric comic strips; he also continued to

freelance, contributing cartoons to Life, Judge, The New Yorker, Collier's, and other leading magazines. On October 11, 1928, he married Anna Rosen; they

had one daughter, Tona (whose name was composed of the last two letters of her

parents’ names).

Soglow’s

first cartoon in The New Yorker appeared in November 1925, just eight

months after Harold Ross launched the magazine. As a selection of his New

Yorker work of the late 1920s shows, he eschewed the dark and grimy ashcan

approach entirely for Ross’s urbane periodical. He was doing both single-panel

gag cartoons, which he rendered with a simple line in a surrealistic manner,

amply toned with gray wash, and comic strips, usually in pantomime, drawn even

more simply, the clear forerunner of his most celebrated work. But at the same

time, as we saw in our previous visual aid, he was doing ashcan-style cartoons

and illustrations for The New Masses.

In

late 1928, Soglow started doing the cartoons that first increased his

visibility in The New Yorker—the so-called “manhole” cartoons. The first

of these was published in the magazine’s December 15 issue. The same drawing

with a succession of different captions would appear regularly for some months

thereafter.

Then

in 1930 with the June 7th issue of the magazine, Soglow’s life

changed forever. The revolution was brought about by a full-page comic strip he

drew that featured a diminutive albeit rotund mute monarch. Ross liked the

character and the concept and asked Soglow to produce another. Ross was picky,

reportedly accepting at the miserly rate of six cartoons for every eight Soglow

produced, but the “little king” was soon a regular feature in the magazine, and

Soglow had inadvertently begun his life’s work.

Pantomimic

cartoon comedy was scarcely a novelty at The New Yorker: others of its

regular cartoonists—Al Freuh, Gardner Rea, Rea Irvin, Gluyas Williams, even

Peter Arno (to name a few)—had been doing pantomime comic strips for years.

But Soglow’s silent king was different: he had an

endearing personality. He seemed not to enjoy the pomp and circumstance of his

station in life: this king was always playing hooky, indulging the small boy

within him. And we smiled at his juvenile enjoyments.

But

Soglow’s labors were not confined exclusively to a cartoon throne room. He

continued to freelance his work in other publications, and in 1931, a number of

his previously unpublished cartoons of a mildly risque sort appeared in a

compilation of kindred comedy entitled The Stag at Eve, which included

cartoons by numerous other worthies—chiefly, William Steig, Gardner Rea,

Leonard Dove, Barbara Shermund, Raeburn Van Buren.

Meanwhile,

the popularity of the Little King had attracted attention at the Hearst Works,

leading to the offer of a syndication contract with King Features. Soglow

accepted the deal, but the arrangement did not proceed immediately. According

to report, Soglow was under contract to The New Yorker to produce The

Little King, and before he could take up with King Features, that contract

had to expire. While waiting for this eventuality devoutly to be wished, Soglow

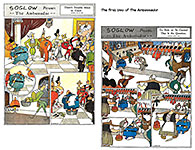

produced The Ambassador as a place holder in pantomime at the syndicate,

starting May 28, 1933.

The

Ambassador seems, at first blush, a character very similar to the Little King:

rotund in physique and August in demeanor, the Ambassador starts each weekly

adventure with appropriate pomp but inevitably finishes in a wholly incongruous

situation. Hence, the comedy. But the Ambassador was not very likeable. No

mischievous little boy lurked within the Ambassador. Nor did the incongruity of

the strips’ endings seem to reveal the fraud in the ambassadorial milieu. The

Ambassador seems, in comparison to the oft childish King, haughty rather than

humble.

The

fascinating aspect of The Ambassador resides in the inventiveness of

Soglow’s layouts in the earliest of the strips. It is as if the cartoonist,

faced with a full-page format in color for the first time, felt the need to

experiment with the form itself.

Soglow

had been doing full-page strips for the Little King at The New Yorker,

so it wasn’t the format itself that inspired such wild invention: it may have

been the presence of color that prompted him to play with the form. Or perhaps,

more likely, it was the greater expanse of a newspaper page, offering more

space for playing around with shapes and their array than the smaller New

Yorker page size.

But

the experimental phase didn’t last long: by the fall of its inaugural year, the

strip had assumed the traditional grid format of all Sunday comic strips.

Presumably, a standard format is easier for newspaper editors to work with; an

unconventional format, even if it fills over-all the customary rectangular

shape on the page, taxes the editorial patience, which, we assume, is always in

short supply when it comes to comics. (At about the same time—and for about the

same reason—George Herriman’s lyric Krazy Kat, which Sundays were

often a krazy kwilt of panels, many adrift without borders, was forced into a

grid of bordered panels.) The Ambassador lasted only fifteen months,

ending September 2, 1934.

By

then, the King’s reign at The New Yorker was over: it concluded

September 1. A week later, he was crowned into national newspaper syndication

on September 9, 1934, as a Sunday-only comic strip.

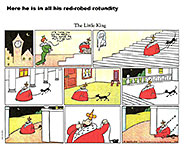

The

Little King is renowned for the utter simplicity of Soglow's drawing style

and for the title character's humility and ingenuity—and silence. Soglow's

drawings are minimalist art, diagrams in plane geometry. The body of the

Little King, a short fat fellow, is the simplest of circles. The humor of the

feature is built upon contrast: instead of behaving like a crowned head of

state, the Little King acts like an ordinary citizen (or an adventurous boy).

When

he leaves his castle because it is about to be besieged, he pauses on his way

out to leave a note for the milkman. He confers knighthood upon a courtier but

afterwards holds out his palm so the new knight can pay him a fee. He is often

more mischievous youth than reigning monarch: he is not above indulging in a

juvenile prank. He throws out the first ball to begin the baseball season; when

the ball goes over the fence and breaks a window in a nearby house, the Little

King runs away like any neighborhood kid. When the royal dishwasher quits,

leaving behind an enormous stack of dirty dishes, the Little King tackles the

problem by putting on his swim suit and taking the entire stack of dishes with

him into the swimming pool. The over-all effect of such adventures is to

ridicule pomposity while championing the joys of ordinary life. But the Little

King was not so much a satirical strip as it was a playful one.

The

simple plots of these gags work because they unfold in pantomime. The Little

King never speaks; others in the strip might say a few words occasionally in

order to clarify a situation leading to the punchline, but the King is forever

mute. With little or no verbiage to prepare us for what is coming, we must

rely entirely upon the pictures. And the visuals "narrate" the "story"

one plot increment at a time, keeping us in suspense about what the King is up

to until we reach the final panel where the "mystery" is revealed,

the surprise and/or the King's inventiveness provoking our laughter.

For

a short time during the unpleasantness in Europe in the early 1940s, Soglow

introduced a new character in the strip—Ookle the Dictator, a foil for the

Little King and a send-up of the various dictators who populated the world

stage during World War II. Ookle started as a junk dealer, but when he won a

game of poker with the King, he assumed command of the kingdom. Unlike the

King, Ookle spoke; I’m not sure that the King always listened. In fact, the

comedy of this series lay in the King’s ignoring or frustrating the Dictator’s

commands in favor of a more personal momentary pursuit.

In

addition to producing The Little King, Soglow did Sentinel Louie, another Sunday pantomime strip. Louie began as the third-page “topper”

running at the top of The Ambassador page. When The Little King started, it inherited Louie, which continued until some time in 1943, by

which time, newspapers had started to reduce the size of Sunday strips,

contributing the saved newsprint to the war effort for use elsewhere as gun

fodder.  In

1946, Soglow produced Travelin’ Gus, yet another pantomime

enterprise—this one about a streetcar driver. In

1946, Soglow produced Travelin’ Gus, yet another pantomime

enterprise—this one about a streetcar driver.

Wholly

unnoticed by histories of the medium and therefore rare enough to justify our

attention here, this strip lasted only a few months, from February (perhaps the

10th) until October 6, and we can see why: Gus lacked the endearing

personality traits of the Little King. But the humor employs the same basic maneuver—building

a mystery for several panels and then revealing an explanation in the last

panel.

The explanation, the ingenuity of the contrivance, makes us

chuckle. This approach to humor can work only with a “silent” strip: the

mystery could not easily (or persuasively) be maintained if any of the

characters spoke.

Throughout

a long career, Soglow continued to draw gag cartoons for magazines and

regularly illustrated columns and features in such periodicals as The

Saturday Evening Post; he drew decorative comic spot illustrations for The

New Yorker’s “Talk of the Town” column until 1972. He also illustrated

some 30 books, among which numbered some of his own cartoon collections: Pretty

Pictures (1931), Everything’s Rosy (1932), Another Ho Hum: More

Newsbreakers from The New Yorker (1932), The Little King (1933), Soglow’s

Confidential History of Modern England (1939), and, with D. Plotkin, Wasn’t

the Depression Terrible? (1934).

The

Little King was discontinued with the release for July 20, 1975, Soglow

having worked that far ahead before he died in his New York City apartment,

April 3, 1975. A founder of the National Cartoonists Society in 1946, Soglow

served as its president 1953-54.

He was

named “cartoonist of the year,” collecting a Reuben statuette, in 1966, and in

1972, he was the second recipient of the Society’s Elzie Segar Award “for

unique and outstanding contributions to the profession of cartooning”—a

recognition, doubtless, of his long service to the club as much as for The

Little King.

And

in NCS, he at last achieved his life-long ambition: he acted often in

vaudevillian skits performed at the Society’s dinners. He did similar turns at

events for the Society of Illustrators, of which he was also a member. He even

dressed up as the Little King for various after-dinner entertainments hither

and yon through the city. According to those who knew him, Gardner says, he is

remembered better as a performer than as a cartoonist. But for us hoipolloi, he

will be fondly remembered for the pantomime routines of a diminutive round

monarch in a red robe.

Sources.

Apart from the NCS (member) Albums and a few syndicate press releases, there is

no readily available biographical information about Otto Soglow except that

retailed (happily in carefully researched detail) by Jared Gardner in Cartoon

Monarch: Otto Soglow and the Little King (2012). The Little King is

discussed briefly in the standard histories of the medium— Comic Art in

America by Stephen Becker (1959) and The Comics by Coulton Waugh

(1947); Ron Goulart’s Encyclopedia of American Comics (1990) and The

Funnies (1995); Jerry Robinson’s The Comics: An Illustrated History of

Comic Strip Art 1895-2010 (2011), which, alas, assumes that the Little

King grew out of The Ambassador. Dates of Soglow’s various strip

creations are found in Allan Holtz’s American Newspaper Comics: An

Encyclopedic Reference Guide (2012).

Return to Harv's Hindsights |