Withdrawing

the Color Line

E.

Simms Campbell, the First Famous Black Cartoonist

All

around the tiny room in the rear flat on Edgecombe Avenue in Harlem were stacks

and stacks of drawing paper with pictures on them, tottering stalagmites of

wispy pencil sketches, muscular charcoal renderings, stark black-and-white

woodcut-style renderings, and delicately hued watercolors. The linear quality

in the drawings had a nervous, searching aspect: outlines were made with

several strokes of the pencil as the artist sought exactly the right placement,

then the final delineation was made with single firm, dark stroke. Texture and

modeling were added with grease crayon or charcoal or simply repeated strokes

of a snub-nosed pencil, dashing diagonal lines back and forth across the

surface of the picture to produce gray tones from dark to light. In the

watercolor pictures, the lines were simpler, single strokes outlining figures

and features—with color added in broad daubs and easy splashes. And sometimes,

with no lines at all, modeling done with swatches of color alone.

In

the midst of the room's litter, a twenty-five-year-old man of an even, dark

cinnamon complexion sat at a drawingboard propped against the edge of a

dresser. His visitor, a white man perhaps only four or five years older than

the artist, stared at the stacks of drawings, his eyes bulging slightly as

disbelief surrendered to comprehension. He saw gag lines written below many of

the pictures, and he knew, then—beyond any hesitancy or doubt—that he had

discovered a treasure trove of cartoons, a bonanza of bonhomie as yet mostly

untapped by the publishing world at large.

"I

wanted to yell Eureka," the man said later when writing his

autobiographical Nothing But People about the early days at Esquire magazine,

"—because I saw at a glance that my troubles were over" (95).

What

Arnold Gingrich called his "troubles" early that fall of 1933 any

other magazine editor would have dubbed a blessing: his publisher in Chicago

had just phoned him in New York to tell him that the number of color pages in

the maiden issue of their new magazine had been increased from twenty-four to

thirty-six. This unanticipated bonus was troublesome only because Gingrich had

been hustling to fill twenty-four pages with color illustrations; with the

allotment suddenly increased by a third, his quest had turned into a desperate

scramble.

They

had always planned on devoting plenty of pages in the magazine to full-page

cartoons, and now, with the windfall color pages, cartoons in color seemed the

easiest solution to Gingrich's problem. All he needed was twelve good cartoons

in color. He had journeyed to New York to secure for the magazine the work of

the cartoonist whose renditions of the rounded gender would be perfect, he

knew, for a men's magazine such as Esquire planned to be.

Russell

Patterson was, Gingrich said, his "beau ideal of the kind of

cartoonist" they wanted: the "Patterson Girl," a regular fixture

on the covers of Sunday supplements and humor magazines, was as well known as

the Ziegfeld Girl. But Gingrich was on a budget, and when he met Patterson in

his studio and offered him a hundred dollars each for Patterson Girl cartoons,

Patterson had laughed. Just laughed.

"I

don't think any well-known illustrator would be interested in doing work for

your magazine at that rate," Patterson said. "But I know a young

fellow who might serve your purpose—if you don't draw the color line."

Gingrich

said he had no use for the color line—certainly not at present, desperate as he

was. "Besides," he added, "—what the hell, magazines weren't

wired for sound, so drawings would not carry any trace of any kind of

accent" (95).

So

Patterson told him about "a fantastically talented colored kid," a

graduate of the Art Institute of Chicago, who produced reams of wonderful

drawings that he was unable to sell because, Patterson averred, as a black man,

he couldn't get past the receptionist to show his wares to any editor in New

York.

He

gave Gingrich an address where the artist was living with his maiden aunt, and

Gingrich went to Harlem. "I had to step over squads of kids on the outside

stairway to get to the room where he worked," Gingrich said. And that's

how he met Elmer Campbell, who would become rich and famous as "E. Simms

Campbell," Esquire cartoonist par excellence.

Gingrich,

his ears ringing and his breathing more and more constricted, pawed excitedly

through Campbell's stacks of cartoons. "I saw that they were all

beautifully executed," he said, "whether as roughs or as finishes. My

impulse was simply to poke a finger in toward the point midway down of each

pile and say, 'How much down to here?'" (95).

He

took armloads of the cartoons away with him, leaving his check for a hundred

dollars as a "down payment" against future publication, which,

Gingrich assured the young cartoonist, would be extensive. For the next 38

years, beginning with three cartoons in the very first issue dated Autumn 1933,

Campbell's cartoons and illustrations appeared in Esquire with such regularity

that Gingrich believed the cartoonist was in every issue until he died.

Gingrich had discovered this phenomenon when assembling a collection of

cartoons for Esquire's 25th anniversary.

For

the entire quarter century, Gingrich wrote, "the common denominator was

that not one issue had ever gone to press without a cartoon by Campbell."

Thereafter, "it became a point of pride with the editors and the makeup

people to see to it that nothing should be allowed to let him spoil that

perfect record; and although there were times when it was necessary to dig up a

rough sketch out of the files and run it in its really unfinished state, for

failure to receive a fully rendered drawing on time to make a given issue's

press date, none had, until some months after his death, ever actually gone to

press without a Campbell cartoon" (97).

However

fondly and passionately Gingrich believed this, I, alas, have three issues of Esquire (January and September 1946, January 1947) without Campbell cartoons. There may

be more. But the myth is, notwithstanding, a measure of the esteem in which

Campbell was held.

In

addition to cartoons, Campbell collected pay for supplying gags that other

cartoonists illustrated—forty or fifty ideas a month, he claimed.

Said

Gingrich: "It was Campbell's roughs and our using them to inspire other

cartoonists that had the most immediate bearing on the magazine's success.

Without a doubt, it was the full-page cartoons in color, an ingredient that we

hadn't even thought of in the first place, that catapulted the magazine's

circulation from the start" (97).

Campbell's

impact did not end with cartoons. He also contributed the image of the

magazine's familiar mascot, the pop-eyed moustachio'd old rake called Esky. For

weeks, Arnold had been trying in vain to come up with a satisfactory image for

the purpose. He noticed several sketches of an impish little man among the

drawings stacked in Campbell's room and, with the artist's permission, added

the pictures to the stack of cartoons he carted off. A short time later,

sculptor Sam Berman in New York transformed the Campbell character into a

three-dimensional ceramic figurine, which was henceforth photographed for cover

appearances with every issue of the magazine.

BORN

JANUARY 2, 1906 in St. Louis, Campbell had displayed artistic talent at an

early age and resolved on a career in commercial art despite occasional

admonitions from his elders that any "Negro" with such ambitions would

be wasting his time pursuing them. He learned the fundamentals of art from his

mother, an amateur painter; his father, a high school principal, died when his

son was only four, and young Campbell went with his mother to live with an aunt

in Chicago, where, attending Englewood High School in 1923, the youth won a

national contest with an Armistice Day commemoration cartoon. The drawing

depicted a soldier kneeling at the grave of a comrade, saying: “We’ve won,

buddy.”

Campbell

went to the Lewis Institute briefly and then attended the University of Chicago

for a year before shifting to the Art Institute. While in Chicago, as reported

online at Answers.com, Campbell was one of the creators of College Comics, “a

magazine in which he did many drawings under various pseudonyms.” The magazine,

however, failed.

When

he finished at the Art Institute, Campbell was unable to find satisfying work

in Chicago and so returned to St. Louis and did some freelancing, but his most

gainful employment was as a waiter in a dining-car on the New York Central

Railroad. “It was a let-down,” Campbell said, “but it was the making of me in

this field.”

Campbell

explained during an interview by Arna Bontemps in a 1945 collection of profiles

of twelve successful African Americans, We Have Tomorrow: “Yes,

seriously,” Campbell said. “Up to then , my work had been shallow, but I

learned from my fellow waiters how close man can be to his fellow men. After

this discovery, my character began to develop, and I began to paint and draw

people as they really looked. Oh, I could always draw, but I was a failure as

an artist till I became a successful dining-car waiter.

“You

meet all kinds in a diner, you know,” Campbell continued. “Some are dainty,

some finicky, some calm and patient, some nervous, some are just would-be slave

drivers. Between meals, I spent my time making caricatures of the passengers as

well as of the other waiters and the steward. Before long, I had quite a

collection of these sketches” (quoted online at wetoowerechildren.blogspot.com).

Campbell

showed his sketches around to various advertising studios, and J.P. Sauerwein,

manager of the Triad Studios hired him. “I became one of eight artists on the

staff there in the Arcade building,” Campbell said.

Triad

was one of the midwest’s largest advertising art agencies, and Campbell stayed

there for about a year-and-a-half until 1929, when he left for the Big Apple.

After a month of fruitless pavement-pounding, he found a job with Munig

Studios, a small advertising agency that paid only a fraction of what he’d

earned at Triad. And then he ran into Ed Graham, with whom he had worked on the

campus magazine Phoenix during his brief matriculation at the University

of Chicago.

“Ed

had come on to New York ahead of me,” Campbell told Bontemps, “and he had

already broken into the humorous magazines and made a name for himself. He knew

the editors, and they knew him. I showed him some of my drawings and gags, and

right off the bat, he said, ‘I’ll take you around. This stuff is good.’”

Campbell

was also befriended by C.D. Russell, who was drawing for Judge a

full-page cartoon called Pete the Tramp (later, starting January 10,

1932, a syndicated comic strip), and got “a pat on the back” from James

Montgomery Flagg.

Before

long, Campbell said (Patterson’s contention notwithstanding), he was selling

cartoons to newspapers and the old humor magazines, Life, Judge, College

Humor, and Ballyhoo. He began attending the Academy of Design in his

spare time, and he studied at the Art Students League under George Grosz, the

exiled German satirist. In 1932, he illustrated a book of poetry by Sterling A.

Brown, Southern Road. And the next year, he illustrated Popo and

Fifina, a young adult novel set in Haiti by Bontemps and Langston Hughes.

For both, Campbell drew in stark black-and-white in the woodcut style then

peaking in popularity in the work of German Expressionists and, in this

country, with the wordless novels of Lynd Ward.

Then

he ran into Russell Patterson.

According

to the 1949 King Features Syndicate brochure, Famous Artists and Writers, Patterson

gave Campbell the advice that set him on the road to celebrity and opulence.

“Look,”

said Patterson, “you’re a good cartoonist, but you draw everything under the

sun—men, women, cats, dogs landscapes—everything. Why don’t you specialize? You

might stick to women. If there’s one thing I’ve learned in this screwy business

over the years, it’s that you can always sell a pretty girl” (n.p.).

Syndicate

promotional literature of that day is notorious these days for happy

fabrications, and the meeting with Patterson might be just such a literary

concoction. But judging from Arnold’s story and Campbell’s subsequent career,

there is doubtless more than a mere grain of truth in the anecdote. In any

event, shortly after his debut in Esquire, Campbell was getting

commissions from all around town and elsewhere.

But

it was in Esquire that he achieved the apotheosis of his art.

George

Douglas, writing about Esquire in his history, The Smart Magazines, said: "The Esquire connection meant the most to him, no doubt,

because in essence he, as much as anyone else, established the magazine's

visual style. His work was highly finished and polished, of course, and he

could render a wide variety of curvaceous females—chorus girls, innocents,

vamps, supercharged office secretaries—in moods ranging from the voluptuous to

the risible. His touch, in any case, fit Esquire to perfection. It was

slick, jaunty, tongue-in-cheek, stylishly erotic, playfully adult. So apt was

the material that it was used eventually in all manner of drawings, not only

cartoons—fashion drawings, covers, illustrations for stories and articles,

fillers of all sorts” (194).

Campbell’s

pictures shimmer with color and shapes, line and hue syncopate to conjure a

radiant world of masculine fantasies. Esquire to a incandescent T, with

cravat and well-polished shoe.

Esquire issues through the 1930s often included a half-dozen Campbell cartoons, only

one of which featured the seraglio shenanigans for which he is most fondly

remembered. In the issue for June 1940, the harem is depicted in a double-page

foldout cartoon, glorious in furiously blushing watercolor, seemingly

spontaneously splashed across  the expansive canvas. A 1948 article about

exercising uses his pictures of a comely damsel to demonstrate the exercises.

And Campbell also contributed prose articles on the nightclub life in Harlem

and other topics, all illustrated with his vibrant colors. the expansive canvas. A 1948 article about

exercising uses his pictures of a comely damsel to demonstrate the exercises.

And Campbell also contributed prose articles on the nightclub life in Harlem

and other topics, all illustrated with his vibrant colors.

In

the February 1936 issue, Campbell wrote an article about dance trends in Harlem

and illustrated it with three pages of dancing watercolor pictures. Here (in

italics) are a few paragraphs from the article; we’ll post the pictures after

the prose (which, as you will see, has an engaging scintillation of its own)—:

ALL

HARLEM DANCES. Here, in the heart of New York, between the Bronx and Central

Park, wriggling black America disports itself nightly to the Lindy Hop, the

Shim Sham Shimmy, or to Truckin’, its latest dance creation. In a score of tiny

night clubs, in low-ceilinged cabarets, shot with amber and dull red lights,

couples twist, wriggle and tap to Harlem’s high priestess—the dance. Gone are

the days of the Charleston, the Heebie Jeebies, made famous by Louis Armstrong,

and a score of lesser Stomps. For those possessed of indefatigable constitutions, it’s the Lindy Hop; for

the tap-conscious, the Shim Sham Shimmy, shortened by Harlemites to the Sham; and for everyone inclined to shuffle, it’s Truckin’. ...

Lindbergh’s

world-famous flight to France will always be commemorated by Harlem in the

Lindy Hop, an outburst of gaiety, of pent-up emotions, a dance of sheer joy and

abandonment: ‘Ole Lindy did it!—done crossed de ocean!—oh, swing it boy—swing it!’

A

couple glides across the floor, their arms are propellers, then wings, as they

spin and are off. ... A lithe black boy and a full-bosomed girl, heads thrown

back, eyes closed, strut toward each other like game cocks. ... The girl is as

loose-hipped as a marionette. The boy seems to be made of India rubber. ...

Each has his own interpretation of the Lindy, although both are keeping time to

the mad tempo. They snap their fingers, twist their shoulders, and move in an

ever-widening circle, tapping and spinning as they literally sail away. Now,

stamping their heels and swaying to the rhythm, the dancers come toward each

other: ‘Oh, get

off, boy!—slick black boy in the plum-colored suit, show ’em how to do

it!—strut—slide—strut—truck lightly.’

They

embrace, dip, and are off again. Two or three times they repeat this figure,

each swinging away, spinning, yanking the other all over the floor, and dancing

furiously around the other, finally fusing together and doing a side-kick,

holding hands tightly for balance. ...

Eliminating

every movement of exertion is the ‘Truck’ or ‘Truckin’, as it is called. It’s

done to four-four time and consists of placing the right foot behind the left

heel and sliding forward flatly on the right foot, the left knee bent and kept

close to the right leg. At the completion of the slide, the right foot is

turned abruptly outward, the body swinging right. This same movement is begun

again with the left foot, starting the slide close to the right foot, and the

right knee bent. The head is inclined to the side, arms akimbo and swinging

slightly. It’s the ‘Take it easy’ dance of Harlem.

As

to its origin, Cora La Redd of the Cotton Club, ‘Rubberlegs’ Williams, the

dance team of Red and Struggie, and numerous entertainers have claimed to have

had some part in its birth, but ‘Chunk’ Robinson, a comedian, told me it was

first used, positively, as an exit number by ‘Bilo’ Russell from Memphis,

Tennessee. It was about eleven years ago in a show called ‘The Borders of

Mexico’ with an entire Negro cast, that Russell had the happy thought of

sliding off the stage with a rifle on his shoulder. The step had no name, just

a shuffle or an ambling gait. The expression ’Truck’ was used around 1932 in

Harlem when one of the bucks of the evening in bidding adieu to his friends,

would say, ‘Well, boys, I think I’m gonna truck on home.’

My

idea is that the association of porters with carrying bags on trucks, with

Negroes pushing and shoving packages and heavy burdens could logically be

followed: to haul one’s self home—to shove on home—to ‘truck’ on home. ‘Chunk’

Robinson, however, tied the expression up with the dance and started it in New

York at Small’s Paradise, a cabaret. It was an instantaneous hit. All of the

clubs throughout the length and breadth of Manhattan, including Broadway revues

and clubs, are now featuring a ‘Truckin’ number, and one cannot tell just where

it will end. ... Where it started and where most of Harlem’s dances reach their

terpsichorean peak is the Savoy Ballroom on Lennox Avenue, the ‘Home of the

Happy Feet.’

Outside,

on the street corners, awaiting the dance hall’s opening, the boy who runs the

elevator in your building, the boot-black, the errand-boy, all of them in

ankle-length overcoats and sporting pear-gray, almost brimless hats, are as

actors awaiting their cue. Through the long, weary day, they have been menials

and domestics in the downtown white New York, but at night, in Harlem, they

throw off the garb of servility and don royal raiment. Harlem is in the

ascendancy at night.

AND

HERE’S how Campbell illustrated this exuberant exposition.

Campbell’s

pervasive presence in Esquire would easily justify dubbing the

cartoonist the spirit of Esquire in its first couple decades.

Beyond

the pages of Esquire, Campbell’s sprawling signature appeared on

cartoons published in Cosmopolitan, Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s,

Redbook, The New Yorker and other mainstream magazines. One of his drawings

was on the cover of The New Yorker for February 3, 1934; he’d had covers

on both Life and Judge earlier in the decade and again later. And

he was sought out by advertising agencies, particularly if pictures of shapely jeune

filles would help promote sales of the products. According to Answers.com,

Campbell was one of the highest paid commercial artists in the 1930s.

|

|

During

his interview with Bontemps, Campbell explained why he drew cartoons instead of

expressing himself in other so-called higher visual arts: “I prefer cartooning.

You see, I like jokes, and it’s hard to put a joke into an oil painting. Have

you ever noticed how quiet people are in art galleries? Well, I don’t think

that’s what pictures should do to you. They should make you want to laugh,

talk, shout—anything but hang your head.”

He’d

done serious paintings of the artistic sort, he went on—among them, “The Wake”

and “Levee Luncheon,” both of which in exhibition “got their share of

attention, but even then, the thing about them that critics mentioned was their

humor.”

LIVING

UP TO HIS BURGEONING INCOME, Campbell moved into the Dunbar Apartments on

Seventh Avenue, the most glamorous apartment building that African-Americans

had in New York. And there, the cartoonist met Cab Calloway, jazz musician, band

leader, and the instigator of Minnie the Moocher, whose scat

"hi-de-hi-de-hi-de-ho" enlivened the evenings at the Cotton Club

whenever Duke Ellington had gigs out-of-town. The jazz man and the cartoonist

became fast friends and frequent habitues of Harlem nights.

Calloway

loved Harlem. "Harlem in the 1930s was the hottest place in the

country," he wrote in his autobiography, Of Minnie the Moocher and Me.

"All the music and dancing you could want. And all the high-life people

were there. It was the place for a Negro to be. ... No matter how poor, you

could walk down Seventh Avenue or across 125th Street on a Sunday

afternoon after church and check out the women in their fine clothes and the

young dudes all decked out in their spats and gloves and tweeds and homburgs.

People knew how to dress, the streets were clean and tree-lined, and there were

so few cars that they were no problem. Trolleys ran down Lenox Avenue to

Central Park. People would go for picnics on a Sunday afternoon, and the young

couples would head for the private places between the rocks to spoon and make

eyes at each other. I'm not being romantic. Harlem was like that—a warm, clean,

lovely place where thousands of black folks, poor and rich, lived together and

enjoyed the life" (116-117).

Harlem

was also the destination for much of New York's night club population, white as

well as black. And Calloway and Campbell joined in.

"He

was the first Negro cartoonist to make it big,” Calloway said (employing the

term for his brethren that was then, in the mid-1970s, still racially

judicious). “By the time I met him, he was a well-established cartoonist. He

was also, like me, a hard worker, a hard drinker, and a high liver. I used to

think that I worked hard. Cotton Club shows six or seven nights a week,

matinees at the theaters a couple of afternoons, theater gigs sometimes in

between the Cotton Club shows, and benefits on the weekends. But Campbell

outdid me. He drew a carton a day, not little line drawings, but full

watercolor cartoons. And he played as hard as he worked. He loved to drink.

When we got to know each other, we would go out at night to the Harlem

after-hours joints like the Rhythm Club and just drink and talk and laugh and

raise hell until the sun came up. Somebody would get us home and pour us into

bed, and we'd be back at it again the next night.

"One

of my favorite cartoons by Simms," Calloway continued, "shows a boys'

choir in a big church. All the choirboys are white except for one big-eyed

Negro. The choir master is getting ready for the Sunday service, and he's

looking at this Negro kid with a reprimand in his eyes. The caption reads: 'And

none of that hi-de-ho stuff.' Elmer did that cartoon in 1934, and it was

published in Esquire in October of that year.

“He

and I were tight friends by then,” Calloway went on. “Jesus, I loved that man.

He was one of the straightest, most natural men I'd ever met. Unaffected, you

know, just honest and open; loud and noisy when he got drunk, and ornery as

hell when anybody disturbed him while he was working. ... Over the years, we

stayed close to each other. Many a night, he and I would hang out together

screwing around, drinking bad gin straight in after-hours joints. I would

complain to him about my wife, and he would complain to me about his. We were

personal with each other, and we could holler at each other about our problems

while we laughed at them. ... We joked and laughed and shared things, man to

man. There are few men I've had that kind of friendship with" (118-119).

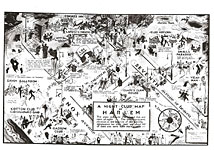

When

Campbell drew a map of Harlem night spots, Calloway proclaimed it “not an

ordinary map; it gave a better idea of what Harlem was like in those days than

I can give you with all these words. I always loved that map, and I still have

the original of it in my office at home”—as prominent in his abode as he and

the Cotton Club are at the lower left on Campbell’s map.

In

1936, Campbell moved to fashionable Westchester County where he built a

flagstone mansion on a lush four-acre tract of land, about which Gingrich

exclaimed: "It was many years before it was anything but earthshaking to

have a home of that kind [in that neighborhood] occupied by a Negro” (96).

Campbell

worked in his studio at home, sending the finished work to his clients in

Manhattan and elsewhere. Eldon Dedini, another cartoonist celebrated for his

painterly style when he was cartooning for Playboy, was under contract

to Esquire in the 1940s to produce gags for other cartoonists, and he told

me something about Campbell’s working methods. Apparently, so the story goes,

Campbell’s cartoon hadn’t arrived at the editorial offices, so a messenger was

dispatched to White Plains to pick it up. But when he arrived, he found there

was no cartoon to be picked up.

Nothing

wroth, Campbell invited the messenger into his studio, poured a tumbler of

whiskey and began to paint as he drank. He finished both the drink and cartoon

at about the same time, neither taking him very long. Probably apocryphal.

While

Campbell drew cartoons about life among the fun-loving classes and wrote

articles about the nightlife in Harlem, he was justly celebrated for drawing

pretty girls, and he gained renown for the watercolor bagnio cartoons the

populace of which he rendered in lovingly luminous flesh tones. The girls in

Campbell's cartoons looked white, but according to the cartoonist, "If

they came to life, they'd be colored. Colored girls have better breasts andmore sun and warmth," he is reported to have said; "I like a fine

backside, and they have it!"

In

April 1940, Campbell's leggy ladies began appearing in black-and-white in a

dailynewspaper cartoon called Cuties from King Features Syndicate.

Drawing with a supple pen, Campbell created pictures that contrasted the naked

linear simplicity of his girls’ long legs with the etch-like fine-line shading

that delineated their attire, a happy combination that kept Cuties going

until 1971, eventually achieving a circulation of 145 newspapers. But the

cartoonist’s photograph didn’t appear in syndicate promotional literature until

the late 1940s: a black man drawing zaftig white girls in various states of

undress, however modestly portrayed for newspaper readers, would have

scandalized the editors of papers in the South, who, as a matter of course,

would undoubtedly have canceled their subscriptions to Cuties in droves. In

April 1940, Campbell's leggy ladies began appearing in black-and-white in a

dailynewspaper cartoon called Cuties from King Features Syndicate.

Drawing with a supple pen, Campbell created pictures that contrasted the naked

linear simplicity of his girls’ long legs with the etch-like fine-line shading

that delineated their attire, a happy combination that kept Cuties going

until 1971, eventually achieving a circulation of 145 newspapers. But the

cartoonist’s photograph didn’t appear in syndicate promotional literature until

the late 1940s: a black man drawing zaftig white girls in various states of

undress, however modestly portrayed for newspaper readers, would have

scandalized the editors of papers in the South, who, as a matter of course,

would undoubtedly have canceled their subscriptions to Cuties in droves.

In

the early years of his syndication, Campbell's race was a well-kept secret at

King. And when he occasionally joined other cartoonists of the National Cartoonists

Society in roving around Manhattan nightclubs, his racial identity sometimes

underwent transformation. If the group was stopped at the door by the bigotry

of the day, Campbell's cohorts assured the officious factotum guarding the

entrance that the dark-skinned man in their company was, in fact, an Arabian

prince. Doors promptly swung open.

The

color bar began to be lifted somewhat in the 1950s, but Campbell had, perhaps,

had enough, and by then, he was able to do something about it. In 1957, he left

his baronial mansion in White Plains and moved to Switzerland, where he lived

until 1970, mailing his work to stateside clients. In the early 1960s or

thereabouts as Esquire underwent format changes, Campbell's harem girls

moved to Playboy. Campbell returned to the U.S. in the fall of 1970 and

soon thereafter learned that he had cancer. He died in January 27, 1971.

Calloway was heartbroken.

"I

have lost many relatives and friends in my years," Calloway wrote,

"but other than the death of my mother, none has struck me as Elmer

Campbell's did. It was because the man was so full of life that his death hit

me so hard." At the funeral home, Calloway was overcome. "I was angry

that he'd left me," he said. "The feeling came upon me so suddenly

that I had no control of myself. This goddamn man who I had known for so long

and spent so many drunken and sober, joyful and serious hours with had left

me." He began beating his fists on the coffin and hollering. His wife and

friends pulled him away.

Said

Calloway: "I've known and worked with people like Duke Ellington, Pearl

Bailey, Lena Horne, Dizzy Gillespie, Jonah Jones, and Bill Robinson—to name

just a few—but if you want to know the name of a guy I loved, remember E. Simms

Campbell. My friend" (120).

The

rest of us will remember Campbell as a brilliant stylist, an artist of

surpassing skill. His mastery watercolor is stunning. And he displayed similar

mastery of other illustrative modes throughout a long and prolific career. He

was inducted into the Society of Illustrators Hall of Fame in 2002.

Campbell

was, as far as I'm able to determine, the first African American cartoonist to

achieve celebrity in the world outside the black community. Although Campbell

is sometimes called the Jackie Robinson of commercial art and cartooning, that

christening is probably posthumous: unlike Robinson’s, Campbell’s race was a

secret for much of his career. But his mark on the history of American

cartooning is indelible.

Campbell's

mastery of watercolor is stunning. And he displayed similar mastery of other

manners of drawing and painting.

Return to Harv's Hindsights |