|

And Now,

For Something Completely Different

REST IN

PEACE AND ACCLAMATION, BARD

Celebrating

the 400th Anniversary of the Death of Willie Wagstaff

William

Shakespeare died 400 years ago on April 23, almost 52 years after he was

baptized on April 26 in Stratford-on-Avon, a ritual customarily performed

within a few days of birth. Convenience and tradition have established his

birthday as April 23, 1564; for the sake of poetry, we might say, he died on

the anniversary of his birth, his birthday. Here in Harv’s Hindsight, we

commemorate both dates on the 400th anniversary of his death this

month. And we seize the opportunity afforded to defend the Bard’s reputation.

Years

ago, I used to have ferocious arguments about Shakespeare as often as I could

with Allan Gross of Insight Studios. Allan contended with some heat the

Shakespeare did not write the celebrated plays attributed to him. Scoffing

condescendingly, I disparaged his contention with an overpowering contrary

argument that convinces sensible people everywhere that I am right and he is

wrong. Allan, being only marginally sensible, remained unconvinced. And the

recent appearance of yet another tome in the assault on the Bard’s achievement

is likely to supply him with even greater reluctance to admit that he’s wrong

and I’m right.

The

Truth Will Out: Unmasking The Real Shakespeare by William Rubinstein and

Brenda James offers yet another candidate for the dubious distinction of having

secretly authored Shakespeare’s plays. I haven’t read it. But I have read a

good deal of the literature debunking the so-called Shakespeare’s claimants,

and I am almost certain that this theory, like all of the others that have gone

before, is balderdash.

The

new candidate for the playwright of Shakesspeare’s plays is Sir Henry Neville,

who was discovered by James while she was pawing through the plays on another

errand, using a 16th century code-breaking technique. She did not

expect to discover the true identity of the person who wrote the plays, but,

she believes, she did. Once Neville was revealed, it was discovered that the

locales of the plays, arranged in their supposed order of composition, reflect

the places Neville was traveling at the times the plays were written. Moreover,

Neville’s ancestors, the Plantagenets, are always favorably portrayed in the

plays. A conclusive happenstance, obviously. And there’s more of the same. But,

as I said, I haven’t actually read the book, so I shouldn’t be dismissive of

it. Still, considering the failure of its predecessors in this exercise of

debunking Shakespearean authorship, it’s difficult not to be nonchalant.

During

a trip to England in the summer of 2005, I and my wife stayed in

Stratford-on-Avon for five days, and I tramped around the Shakespeare sites,

looking for more evidence to shore up my side of the argument. Shakespeare

being the local industry there, you can find plenty of evidence of the high

regard the Bard's contemporaries held him in. Among the evidences, an

impressive bust of the man, purporting likeness, over his grave in a local

church, the Holy Trinity. And the bust holds a pen and a piece of

parchment—symbolizing his profession ass a writer. His fellow citizens would

scarcely have erected this monument to a fraud: clearly, they believed he'd

written his plays.

That,

of course, proves nothing: if Shakespeare's alleged authorship of some three

dozen plays, many masterpieces of English literature, were part of an elaborate

conspiracy at the heart of which was the secret of the real author's identity,

the monument on the wall of that church proves only that his fellow citizens

weren't in on the secret. They, like everyone else, were fooled.

But

we don’t need to visit Stratford for validation of Shakespeare as author of the

plays attributed to him.

Doubts

about Shakespeare's authorship have their roots in an ignorance of Elizabethan

England that prevailed in the middle of the nineteenth century. Several

otherwise respectable personages became convinced that Shakespeare, a poor

glover's son in a provincial town, could not have possessed the education or

experience to have written the works of genius attributed to him. Shakespeare's

plays, these people maintained, were actually written by a contemporary of his,

a noted politician, historian and essayist named Francis Bacon, who, as a

member of the upper classes, did have the education and experience that the

plays attest to.

None

of these “Baconians,” as they became known, was a literary scholar. Nor, as

Brian Vickers noted in The Times Literary Supplement (August 17, 2005),

did any feel “the need to acquire any knowledge of English literature or of the

English language in the sixteenth century, and none bothered to read Bacon. ...

All they needed was the preconceived notion that Shakespeare could not have

written the plays while Bacon could.”

Mere

probability was not, however, enough for the Baconians. They also claimed to

have discovered “messages” hidden in the texts of the plays that disavowed

Shakespeare’s authorship and authenticated Bacon’s. The messages could be found

by deploying convoluted codes that revealed such statements as: “Shakst spur

never writ a word of them”; and “FRA BA WRT EAR AY,” which, the inventor of the

code claimed, meant, “Francis Bacon Wrote Shakespeare’s Plays.”

Unfortunately,

the codes were inconsistent: they changed from page to page. One skeptic used

one of them to find this message: “Master William Shakespeare writ the plays.”

Besides,

if Shakespeare didn’t write his plays, what was he doing? The answer: he was

translating the Bible into the King James Version. And we know this because of

his signature that he inserted into the text. If you go to the 46th Psalm and count 46 words from the beginning, you’ll get the word “shake”; and

if you count 46 words back from the ending, you’ll get “spear.”

Obviously,

applying Baconian logic, Shakespeare translated the King James Version of the

Bible. Why the 46th Psalm? That was how old Shakespeare was when he

finished.

Such

scholarly foolishness aside, the Baconian authorship theory gave birth, in due

course, to other theories, which offered other people as the probable

authors—William Stanley, the Earl of Derby; Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford;

even Christopher Marlowe, another of the playwrights in the milieu of London

theater at the time; and a half-dozen others. You can find them all described

and debunked in The Shakespeare Claimants (1962) by H.N. Gibson.

Although the arguments in favor of other authors are unrelentingly ingenious,

they are all flummery.

IN THE DECADES

SINCE the mid-1800s, we have learned a great deal more than we knew then about

Shakespeare's early life, and the more we have learned, the less unlikely it is

that a "poor glover's son" could have written the plays.

Shakespeare's

father, John, was a glover, true; but he was also a respected member of the

middle class, even the upper middle class. Elected an alderman the year after

William was born, he was eventually mayor of Stratford. He had both social

position and wealth enough to send his son to the local grammar school, where

young Will was inculcated with the usual curriculum, which included Latin and,

maybe, Greek as well as a certain amount of history and the like. In short,

little Willie Wagstaff was not "poor"; and he was not an uneducated

country bumpkin who wandered onto the London stage just in time to be adopted

by some unknown genius who wanted him to pose as the author of his plays. So

there is no longer any justification, as there was when we knew less about life

in Elizabethan England, for disbelieving that Shakespeare wrote the plays

attributed to him.

There

is, however, a mystery in Shakespeare’s life. Making someone else the author of

his plays does not solve the mystery, but the mystery has provoked other myths

about the playwright. Shakespeare married Anne Hathaway, a woman eight years

older than he, in November 1582. Various of Shakespeare’s biographers have

assumed that the older woman inaugurated him into the pleasures of the flesh

when he was 18. She became pregnant, hence the hastily arranged wedding: the

marriage bans were read only once instead of the usual three times. And six

months later, Shakespeare’s daughter Susanna was born. Twins, Hamnet and

Judith, were born to the Shakespeares in February 1585. And after that, we have

no documentation about Shakespeare until his name crops up in the 1592 jottings

of a ill-tempered writer in London, whose jape about “an upstart crow

beautified with our feathers” who is “in his own conceit the only Shake-scene

in a country” recognizes Shakespeare’s emergence as a playwright in the

nation’s capital.

From

1585 until 1592, in other words, we lost track of Shakespeare. During these

“lost years,” we know nothing of what Shakespeare might have been doing. We

have only our assumption that he somehow made his way from Stratford to London,

from glover’s son to playwright. But we have no knowledge of the steps he took.

An

ingenious pair of writers, Graham Phillips and Martin Keatman, have undertaken

the task of filling in this blank and, at the same time, explaining various

inconsistencies in Shakespeare’s life in a book entitled The Shakespeare

Conspiracy. This biography claims that the Bard led a double life. Why, for

example, is Shakespeare known in his hometown of Stratford only as a grain

merchant, not as a famous London playwright? The answer: Shakespeare didn’t

want the Stratfordians to know. The reason: when he was not writing plays or

hanging out with his fellow actors in some London tavern, he was a spy, working

in the Elizabethan Secret Service operated by Francis Walsingham.

During

the “lost years,” Shakespeare was sharpening his espionage skills while traveling

the Continent on an assortment of missions (and picking up incidental knowledge

that he would later use in writing his plays).

Phillips

and Keatman make a convincing case, but it seems built upon a shaky foundation.

The monument to Shakespeare in the Holy Trinity church was erected sometime

between his death in 1616 and the publication of 36 of his plays in the First

Folio in 1623. And it is a monument to a writer, not a grain merchant. The

Stratfordians knew Shakespeare was a writer. Phillips and Keatman’s happy

narrative is therefore a pleasant read but a fiction for all that.

Not

quite. The monument with the bust that we see today was made in 1748 when the

original required restoration, P&K say. The original memorial, the one put

in the church just after Shakespeare’s death by Stratfordians who knew him as

the well-to-do owner of the second grandest house in town (New Place), looks

quite different. The personage depicted was thinner in the face than the

present robust bust. His moustache was longer and drooped. And this original

Shakespeare was not holding a pen and a manuscript: his hands rested upon a

sack—a sack of grain, no doubt.

Obviously,

to the Stratfordians who knew him, Shakespeare was a grain merchant, not a

playwright. And P&K may well be right about the Bard’s double life.

The

evidence of the original appearance of Shakespeare bust can be found, P&K

announce, in two drawings made before the 1748 restoration: one can be found in

Nicholas Rowe’s 1709 biography of Shakespeare; the other (which we reproduce

hereabouts), in Sir William Dugdale’s 1656 Antiquities of Warwickshire.

How

come we’ve never seen these drawings before? I’ve seen several paintings that

purport to be of Shakespeare—and, of course, the familiar Martin Droeshout

engraving that appears on the title page of the First Folio—but in all the

ensuing discussions of the accuracy of the likenesses, no one mentions the two

drawings that P&K refer to, reproducing one of them in their book.

And

so suspicion and contention and frustration prevail apace. And, no doubt, ever

will.

But

these few sentences about Shakespeare’s espionage career provide me with an

excuse to post the accompanying two pictures of Shakespeare—on the left, one of

the most convivial renderings I’ve ever beheld (an interpretation, however, not

purporting at all to be a likeness).

And, on the right,

another happy interpretation, this one by the celebrated caricaturist David

Levine.

AT THE RISK OF

PROLONGING THIS DETOUR, Shakespeare’s appearance has been as hotly debated as

the authorship of his plays. For the longest time, only two portraits were

accepted as authentic likenesses of the Bard. Both of them appear in the

illustration we posted a several paragraphs ago—the bust in the Holy Trinity

church in Stratford and the frontispiece of the First Folio, the Droeshout

engraving (against an enlargement of which I am leaning in the photograph).

Posthumous renditions, both. P&K, as we’ve seen, have successfully

destroyed—or, at least, seriously undermined—the authenticity of the Holy

Trinity bust: what we see today is a reconstruction so at odds with the appearance

of the drawing of the original bust as to qualify as no more than a work of

pure imagination.

The

Droeshout engraving, then, is the only picture of Shakespeare that everyone can

agree is a fair likeness. Playwright Ben Jonson, who knew Shakespeare, strenuously

implied in his dedicatory poem in the First Folio that the engraving looked

like his fellow playwright. And other contemporaries of Jonson and Shakespeare

testified variously in agreement.

This,

however, is but the beginning of a contorted tale. Droeshout did not have the

living Shakespeare as his model: he was only 15 years old when Shakespeare

died. Droeshout was using someone else’s drawing or painting, which he copied,

as best he could, in making his engraving. Droeshout was only 21 at the time

and therefore not very experienced as an engraver. Most experts who ponder his

engraving assume that it is, at best, only a modest approximation of the

picture he used as a reference.

Where,

everyone wonders, is that picture? If it exists at all, it may be the only

portrait of Shakespeare made of the play wright when he was living. A

search for this mystery portrait has been transpiring for centuries.

Since

the National Portrait Gallery was established in London in 1856, more than 60

portraits of 16th and 17th century gentlemen have been

offered to the Gallery purporting to be portraits of Shakespeare. Most have

been proven to be less than authentic for one reason or another. The Soest

painting, for example—which appears in our early exhibit with the Holy Trinity

bust and the Droeshout engraving—was, a dozen years ago when I first assembled

the exhibit, seriously considered as a possible likeness of Shakespeare. Since

then, it has been established that the painter, Gerard Soest, used as his model

a man who was said to look like Shakespeare, not Shakespeare himself. Moreover,

the painting was done in the late 1660s, so it is scarcely a portrait of the

living Shakespeare.

The

Chandos portrait, the last of the quartet in our exhibit, was painted in about

1610, so it has the best chance of being a portrait from life. It also has the

virtue of looking a lot like the Droeshout engraving; it could well be the

model from which the young engraver worked. It acquired its present name

because it was once in the possession of the Duke of Chandos; but how he came

by it, no one knows.

Then

in 2009, another claimant came forward. This is the Cobbe portrait, so-called

because it was in the possession of the Cobbe family.  This portrait, like the

Chandos picture, looks a good deal like the Droeshout engraving—except that the

Cobbe Shakespeare’s hairline has not receded as far as the Droeshout’s (perhaps

the painter was flattering his subject). And the Cobbe Shakespeare is somewhat

thinner in the cheeks—reminding us, maybe, of the Dugdale drawing of the bust

in the Holy Trinity church. This portrait, like the

Chandos picture, looks a good deal like the Droeshout engraving—except that the

Cobbe Shakespeare’s hairline has not receded as far as the Droeshout’s (perhaps

the painter was flattering his subject). And the Cobbe Shakespeare is somewhat

thinner in the cheeks—reminding us, maybe, of the Dugdale drawing of the bust

in the Holy Trinity church.

And

the provenance of the Cobbe painting is significant: it has been with the Cobbe

family since the early 18th century, having descended to the family

through a cousin’s marriage to the great granddaughter of Shakespeare’s only

literary patron, Henry Wriothesley, the 3rd Earl of Southampton.

Here, then, is the connection to the playwright that all the other pictures

lack. Wriothesley may have had the portrait done as a gift to the poet he’d

taken under his wing.

Stanley

Wells, chairman of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, believes that the Cobbe

Shakespeare is the only portrait painted from life—in about 1610, when the

playwright was 46 years old. However, an expert specializing in 17th century art disagrees and says the portrait is of another individual

altogether. It is ever thus: every good idea is whittled down in size by some

jealous malcontent.

An

interested and dedicated amateur Shakespeare scholar, Tom Christensen, has

created another new portrait of Shakespeare by computer morphing together the

Chandos and Cobbe portraits (at rightreading.com) with  fascinating results. It

looks like all three—Chandos, Cobbe, and Droeshout. fascinating results. It

looks like all three—Chandos, Cobbe, and Droeshout.

And

then along came S. Schoenbaum, Distinguished Professor of Renaissance Studies

at the University of Maryland, who wrote William Shakespeare: A Compact

Documentary Life and used as the cover illustration for the 1987 paperback

edition the portrait posted nearby, “from a recently recovered miniature by

George Vertue” (who was born in 1684, too late to know Shakespeare in the

flesh; but it’s a nice, friendly picture of a bearded, balding

Shakespearean-like man).

And

so the search goes on. But it will go on without us for now.

FOR NOW, WE

RETURN to where we were when I so rudely interrupted us—namely, to the disputed

authorship of Shakespeare’s plays. While the excuse for finding someone else to

have written them—namely, that Shakespeare was an ignorant country lout without

the education or experience to pen masterpieces—has evaporated, the followers

of the Baconians continue, as we’ve seen in Rubinstein and James, to put

forward other claimants.

Those

who offer some other author for Shakespeare's plays must successfully perform a

succession of intellectual gymnastics. First, assuming that the general

schooling customs of the time are still viewed as not adequate for producing

Shakespeare's evident learning and knowledge, the alternate author must be

someone who can write. To prove the claimant can write, evidence of his ability

must be produced. And in producing this evidence, these theorists run into the

first contradictory predicament, to which I'll return in a trice.

The

second argument the theorists must win is the one that supplies a reason for

the alternate author's keeping his identity secret. The usual reason is that

"writing"—particularly in association with scruffy and disreputable

London actors—was not, then, a respectable profession (anymore than writing

comic books was respectable before the advent of graphic novels, which gave the

medium literary and therefore social status). If the real author were a

nobleman or a respected member of the upper class, he would not want to sully

his name and reputation by becoming known as a playwright. But (and here’s

where we come to the contradictory predicament) if such a claimant had produced

enough writing to prove that he could have written the plays, he would be known

as a writer, his reputation would, perforce, be sullied already.

Well,

maybe playwrighting was deemed a less respectable sort of writing than any

other; maybe it was just writing plays that was so shameful that the would-be

author wanted to keep his participation in London's theatrical life a deep,

dark secret. Let's grant that proposition and move to the next hurdle: why did

the secret author of the plays pick Shakespeare as his "stand-in"?

What was there about this country clodhopper that made him the obvious choice?

Assuming

that the ingenuity of the theorists can contrive an explanation for this, we

next need a convincing explanation for how the secret was kept. Clearly, this

secret was the most well-kept secret in Western Civilization: no one,

apparently, knew that Will Shakespeare, a minor-league actor who wrote plays

for his company, wasn't really writing the plays. It defies our experience of

human nature to suppose that the secret authorship would be known by several

persons, none of whom ever divulged it.

Obviously,

since no one spilled the beans, the secret was known only by Shakespeare and

the claimant himself.

How

was the secret maintained? If Shakespeare's colleagues in the acting company

didn't know about it, how did Shakespeare explain his seeming inability to make

script changes on-the-spot? If the company’s leading actor Richard Burbage

demanded an adjustment in his speech, he would, it can be imagined, expect the

playwright to make the changes right there, during rehearsal. But if

Shakespeare hadn't written the play to begin with, how could he make such

changes? Particularly with his fellow actors looking over his shoulder as he

wrote. So what would Shakespeare say to avoid the necessity of making the

changes immediately? "Okay, okay—you win. I'll make the changes tonight,

and you'll have a new speech tomorrow"?

But

maybe his colleagues did know the secret. If they did, however, why would they

keep it a secret? What compelling reason would persuade them all, to a man, to

keep the secret to the grave?

But,

enough. If the absurdity of the alternate authorship theories isn't apparent in

the difficulties surrounding their invention and maintenance, there is yet

another reason for denying their efficacy. All of the claimants are put forward

in the conviction that Shakespeare could not have written the plays—for one

reason or another. Our knowledge of his early life—of the years between his

schooling, which ended, probably, when he was about fourteen, and his arrival

in London in the early 1590s as a young man well into his twenties—while

greater than it was in the mid-1800s, is still pretty skimpy, and the vacuum

still fosters doubts about the supposed Bard's training and experience. How

could a man whose life is so unknown have the intellectual wherewithal to

produce such impressive literature?

The

answer—which, I submit, lays waste to any argument against Shakespeare's

authorship—is simplicity itself, an exercise in logic, not scholarship. The

plays are universally acknowledged as works of genius. And we cannot explain

genius. A genius doesn't need a college education in order to flourish. A

genius would find ways to educate himself about whatever he decided he needed

to know. The arguments against Shakespeare's authorship crumble away forthwith.

If the plays are the works of genius, then Shakespeare was a genius, and we

require no further explanation for his ability and achievement.

ONE OF THE

REASONS Shakespeare as author of his plays has been vulnerable to attack is

that until quite recently, his adherents were as passionate as the attackers:

neither side would admit of exceptions to their generalities or evidence that

contradicted them. Bardolators were often as misguided and misinformed as Baconians.

But that has changed.

Recent

scholarship, for instance, has admitted a couple more plays to the so-called

Shakespeare canon—"Edward III" and "Sir Thomas More." Both

are collaborations in which Shakespeare had a hand but did not produce,

single-handedly, the entire script. Similarly, “Pericles, Prince of Tyre” and

“The Two Noble Kinsmen” are collaborations. The latter is attributed, when

published in quarto in 1634, on its title page to both Shakespeare and John

Fletcher, who succeeded Shakespeare as house playwright for the King’s Men

theater company. None of these four plays, however, appear in the First Folio,

which, as we’ll soon see, has, for generations, defined the canonical

Shakespeare at 36 plays.

The

First Folio includes “Cymbeline,” “Henry VI, Part 1,” “Titus Andronicus,”

"Timon of Athens," "Measure for Measure,"

"Macbeth," and "Henry VIII"—all of which, saith today’s

scholars, involve some collaboration. The extent varies: some scholars say Shakespeare

wrote about 20% of “Henry VI, Part 1"; but “Measure for Measure” involves

only “light revision” by Thomas Middleton at some point after its original

composition. Middleton is also thought to have revised “Macbeth” in 1615 to

incorporate musical sequences.

Shakespeare

further complicated the authenticity puzzle by re-writing his own plays,

sometimes so extensively that two noticeably different versions of the same

play exist. According to St. Wikipedia, “to provide a modern text in such

cases, editors must face the choice between the original first version and the

later, revised, usually more theatrical version.” Sometimes, they have

conflated the texts to produce “a superior Ur-text,” but critics recently have

argued that conflated texts run contrary to Shakespeare’s obvious intention—to

improve upon his initial composition.

With

“King Lear,” which exists in two independent versions, “each with its own

textual integrity” and structure (one in quarto, one in the First Folio), the Oxford

Complete Works of Shakespeare, published in 1986 (and again in 2005),

provides both versions of the play. The same problem occurs with at least four

other plays—“Henry IV, Part 1,” “Hamlet,” “Troilus and Cressida,” and

“Othello.”

Stanley

Wells, one of the general editors of the Oxford Shakespeare, said a few

years ago: "The world of Shakespeare studies has largely come around to

the view that we espoused of Shakespeare as a collaborator ... [accepting]

Shakespeare as a writer working among a community of writers, and not, as he

has often been perceived in the past, the mysterious, lone-God-figure, passing

his works down ... as from an ivory tower."

The

latest play to be added to the canon, "Sir Thomas More," was never

printed until recently—and it exists in manuscript. The manuscript itself

reveals much about how plays were written: the original hand-written text,

attributed to Anthony Munday, shows the hands of at least four others, which

scholars have identified as Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, and

Shakespeare.

I

have no quarrel with Shakespeare as a collaborator in a "community of

writers" and actors, all engaged in the production of material for

staging. But in allowing Shakespeare his collaborators on a few plays, we need

not attribute all of his plays to another, or others. His collaborators were

not the sole authors of the aforementioned plays any more than Shakespeare was.

At the same time, modern scholarship, while admitting collaborators on a few of

the usual Shakespearean canon, does not admit them on all of Shakespeare's

plays.

Shakespeare's

contribution to "Sir Thomas More," by the way, consists of just two

relatively short passages, not whole scenes or subplots. The bulk of the play

is still Munday's. Presumably, the same can be said for Shakespeare's

authorship of others of his plays traditionally assigned to him but now seen as

collaborative efforts—"Measure for Measure," "Macbeth,"

etc. Shakespeare probably wrote most of these plays while various passages

within were contributed by others.

Even

in the "community of writers," Shakespeare is still presumed to have

written plays virtually single-handed; or, as in the case of “Measure for

Measure” and the other collaborations, he took a commanding lead in devising

those his name has historically been associated with. And this takes nothing

away from his genius, which is the best explanation for the superiority of

these works in the lists of dramas in the English language.

For

our entire experience of Shakespeare’s genius, we are indebted to the

publishers of the First Folio, without which, remarkable as it seems, we would

probably have never heard of Shakespeare or been able to appreciate his

literary achievement.

None

of the manuscripts of Shakespeare’s plays have survived (except for the

aforementioned “Sir Thomas Moore”) so our knowledge of his work depends

entirely on the printed plays. Only 14 of his plays were printed during his

lifetime, the quarto editions, all garbled versions of the actual texts—stolen

from prompt book versions (that were inherently corrupted for use doing

performances) or reconstructed from memory and notes taken by people who

attended the plays in performance for the purpose of “transcribing” the

proceedings to create published versions of the plays, the quartos. None of

these productions, in other words, were supervised by Shakespeare; all are, in

today’s terminology, unauthorized.

The

First Folio, published in 1623, seven years after Shakespeare died, printed 36

of his plays, the entire canon—to which scholars have subsequently added

another four that they’ve determined were partially written by Shakespeare. Of

the 40 plays now accepted as either wholly or partly written by Shakespeare, we

know of 18 only because the First Folio was published.

And

the First Folio is undeniably authoritative: it was assembled by John Heminge

and Henry Condell, names that would doubtless have been lost to history without

the First Folio. Heminge and Condell had been actors in Shakespeare’s acting

company at the Globe Theatre; they had known him personally and his plays

intimately. And by 1623, they were the last living members of that company. The

contents of the First Folio they assembled from whatever manuscripts remained

in the company’s possession plus the 14 quartos—all augmented by their fading

memories of lines they’d performed on stage alongside Shakespeare.

Heminge

and Condell said the First Folio replaced earlier published plays, the quartos,

which they called “stol’n and surreptitious copies, maimed and deformed by

frauds and stealths of injurious imposters.”

One

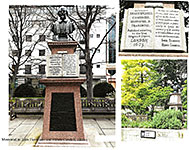

of the oft-overlooked sights in London is the so-called “publishers’ monument.”

Located in the old city far away from Trafalgar Square, the Houses of

Parliament, the Tower of London, Westminster Abbey and the rest of the usual

tourist destinations, the 1896 monument sits on the flagstone paving of a tiny

park, maybe 20x20-feet, surrounded by shrubs and benches in what was once a

corner of the churchyard of St. Mary Aldermanbury (which was all but destroyed

during the bombings of London during World War II; the remaining walls were

transported in 1966 to Fulton, Missouri, where the church was rebuilt as a

memorial to Winston Churchill, who had given there his famous “iron curtain”

speech about post World War II Russia).  Unless you went looking expressly for it, you

would not ever know it was there—a memorial to the men who “created”

Shakespeare: without them, the English language’s greatest playwright would

scarcely exist. Unless you went looking expressly for it, you

would not ever know it was there—a memorial to the men who “created”

Shakespeare: without them, the English language’s greatest playwright would

scarcely exist.

Paul

Collins, an assistant professor of English at Portland State University and

editor of the Collins Library imprint of McSweeney’s Books who appears

regularly on NPR’s “Weekend Edition” as the program’s resident literary

detective, has written a engaging, readable book about the First Folio, The

Book of William: How Shakespeare’s First Folio Conquered the World. In the

book, he conducts an anecdotal expedition—a record of his personal

journey—tracing the convoluted history of the First Folio, through several

re-issues and subsequent revisions (the Second Folio, the Third Folio, etc.)

until its contents were mangled and corrupted—to be rescued, finally, by Samuel

Johnson, who recognized that the best version of Shakespeare’s plays was in the

First Folio. By the time he made this determination, seven faux Shakespeare

plays had been added to the alleged canon in various re-issues of the First

Folio; after Johnson, those fake Shakes were consigned to the limbo they

doubtless deserve.

Only

about 500-750 copies of the First Folio were printed, and all but 233 have

disappeared (although “lost” copies continue to be found in private libraries

and obscure basements). A third of the total—82 copies—are in the Folger

Library in Washington, D.C.; but only 13 of the 82 are complete. Over the

centuries, many copies have been cannibalized, their pages removed and added to

other fragmentary copies to make them complete.

Collins’

story of the First Folio is fascinating, scholarly without being at all stuffy

or intimidating.

And

with that recommendation, we end our testament to the Bard on the 400th anniversary of his death. The vast scholarship about Shakespeare, particularly

his life and milieu, is always fascinating to me. Browsing through these

tantalizing portions of it is good fun. Too bad we have to wait for another 400

years before getting to do it again.

Metaphors

be with you.

Return to Harv's Hindsights |