CRACKED COWBOY

John Severin, 1921 - 2012, RIP

HERE ARE SOME OF JOHN SEVERIN’S drawings from early in his 60-year career illustrating comic books.

|

|

|

|

|

FIRST IN THE LINE-UP are the covers of four of EC Comics’ “New” Two-Fisted Tales (January 1954- February/March 1955) that Severin edited and drew stories for. He did at least one story in most issues, and in Nos. 38 and 39, he drew all four stories. I picked these four covers because they typify the kinds of stories Severin liked to draw—cowboys and Indians the Old West, British soldiers in India and other far-flung posts, and any other kind of exotic, bare-knuckle adventure.

He also liked to draw war stories, and next in the array is a page from a war story bearing one of the storied signatures of yore, a box around two names lettered in the poster font of the Old West with fat serifs and thin stems—Severin and Elder, the latter being Will Elder, who would gain everlasting fame in Mad. Severin was in Mad, too—starting with the first issue (October-November 1952). Severin’s contribution was a spoof of the stalwart gunslinging hero of the Hollywood Western, “Varmint,” the second page of which appears next in our round-up of Severin art. This page holds a hallowed place in my unwritten memoirs.

Severin’s rendering of his mock hero, Textron Quickdraw, inspired me for years. As a teenage cartoonist, I copied that manly profile—jutting square jaw, defiant lower lip, hawk nose, squinty eyes—in every cartoon character I created for at least a year. I never met Severin, but I came close once. It was at the only San Diego Comic-Con he ever attended. I went to the session spotlighting him (a large, burly-looking man with a short, full beard; wearing a cowboy hat, too, if memory serves) (which, alas, it sometimes doesn’t), and when I heard he would go from that session to his table in Artists Alley, I planned to drop by and express my admiration for his work. By way of giving visual substance to that expression, I sketched Textron Quickdraw from memory. (No great accomplishment: as I said, I’d drawn that profile again and again for over a year.) Alas, Severin, who was reputedly not big on basking in fan adoration, never got to his table. At least, not at any of the times I wandered by, clutching my Textron.

Next to Severin’s dogged gunfighter hero is his interpretation of Harvey Kurtzman’s version of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan from the second issue of Mad. It was a key story: it was with this story that Kurtzman discovered the axiom that guided Mad for the next half-century and beyond: “Satire and parody work best when what you’re talking about is accurately targeted,” he decided. “Or, to put it another way, satire and parody work only when you reveal a fundamental flaw or truth in your subject.” To expose a fallacy effectively, he had to be specific about where the fallacy lay. A parody of Westerns in general (“Varmint”) didn’t have the satiric clout that a parody of “High Noon” had. A parody of Tarzan worked better than a parody of jungle lords. And if, as Burroughs told us, Tarzan was raised by apes, then he’d participate in the “grooming” activities of the primates, picking fleas and lice of his companions as Severin’s semi-realistic treatment shows him doing on the story’s splash page.

Although most funnybook afficionados think of Westerns and war stories when they think about Severin, he worked longer in comedic satire than in any other genre. For 45 years, Severin was the mainstay of Cracked, the longest-lasting of a plethora of Mad imitators. Severin was in the first issue, and he designed the most enduring of Cracked’s mascots. At first, the magazine had three—a slovenly layabout editor, Der Editor; a sexy bimbo named Veronica; and the magazine’s janitor, Sylvester P. (for Phooey) Smythe, the image of whom Severin concocted as we see in our next visual aid. Der Editor and Veronica soon faded from Cracked’s pages; Sylvester endured.

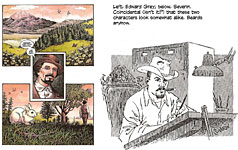

Next to Severin’s Sylvester we see a photograph (clipped from a newspaper halftone; sorry) of Severin at his drawingboard early in his career (probably from the mid-1960s) and four of his self-caricatures, created, I suspect, for Cracked.

I never liked Cracked much. It was an imitation Mad and a cheap imitation. I ignored it. (I ignored Mad, too, when, after Kurtzman’s departure, it had become an imitation of itself.) So I have nothing in the Vast Rancid Raves Library and Subterranean Mausoleum of the Cracked cannon.

I agree with Fantagraphics’ Kim Thompson, who said: “I don’t think I’m alone in thinking of Cracked for most of its run as a bunch of crap—and John Severin.”

If I’d known back then that Severin was a regular in Cracked, I might’ve bought a few issues. But I didn’t and I didn’t.

Fittingly perhaps, I learned about Severin’s death while looking at comic books. On one of my regular visits to my neighborhood comic book shop, I Want More Comics, I was perusing the rack of new arrivals when I heard one of the store owners, Keith Boyle, croak in my direction—“Severin just died.” There was a lump in his voice.

Severin had died a few days earlier, but Keith had just heard about it on the Internet, which he was browsing at the moment, looking for old comics. Or new ones.

Only a few months before, Keith had learned that Severin lived in Denver. I didn’t know that either until Keith told me. We’d been talking about inviting Severin to dinner in a classy restaurant with an intimate group of fellow admirers to celebrate his career and honor his achievement. Working through another devotee, we hadn’t realized that Severin’s health was ebbing away. The dinner plans were put on hold. And now, no dinner. Just remembrances of a glorious body of work.

JOHN SEVERIN died February 12, 2012 at age 90 in his Denver home. His comic book career included drawing gritty war stories, humor and satire in magazines like Mad and Cracked, and superheroics in titles like The Incredible Hulk and Sub-Mariner. He worked until he was 89, when he drew "Lost and Gone Forever" for a five-issue series of Witchfinder, a Dark Horse Comics title that was published just last year.

Severin was born in 1921 on the day after Christmas in Jersey City, N.J., and moved to Long Island as a child, reported Andy Lewis at HollywoodReporter.com. He got his first professional gig in 1932 at the age of 10 when Hobo News purchased some of his drawings, paying the kid a handsome buck apiece. He later attended High School of Music and Art, a Manhattan alternative public school now known as Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts. Future comics legends Harvey Kurtzman, Will Elder, Al Jaffee and Al Feldstein were among his classmates.

After graduating from high school in 1940, Severin, oddly, didn’t find a job drawing. He went to work at A.C. Sparkplug Company in Long Island City, where, according to his 1999 interview with Gary Groth in The Comics Journal (No. 215), he made 20mm shells for the British and French air forces. Why wasn’t working at a job involving drawing?

“I have no idea,” he told Groth, saying he just evolved. “Whatever came along, I just adapted to it. Some guy offered a job that sounded good, I’d take it. My drawing was just part of me. [In other words, he didn’t think of drawing as a livelihood.—RCH.] You’d think after going through that high school and the preparation they gave us there, it would come to me [that I should make a living drawing], but I never was especially bright.”

When the U.S. entered World War II in 1942, Severin enlisted and, after a succession of training camps, wound up in a camouflage unit: because he was colorblind, he could spot camouflage easier than normally sighted people. “They used me to determine whether camouflage was good or bad,” he said. Eventually, disgusted with the mundane work, he volunteered as a machine gunner and finished the War serving in the Pacific.

Upon discharge, he returned to New York where, after a short stint at the Art Students League, he joined his highschool classmates at their commercial art studio which was inventively named the Charles-William-Harvey Studio, deploying the first names of Kurtzman, Elder and another highschool chum, Charles Stern, who seemed perpetually associated with Kurtzman thereafter.

According to Severin, he just fell into drawing comic books. “I didn’t even read comic books,” he told Groth, “—oh, I shouldn’t say that. My wife told me, ‘Never tell anybody that,’” he joked, then continued: “I got into the comic business the same way I got into the bubblegum business: somebody gave me a job. This time, I did go out and get my own. But up until then, I hadn’t been involved with comics. I knew nothing about it at all.”

At the studio, he noticed Kurtzman working on comic book pages, and Kurtzman encouraged him to try to sell to the numerous comic book publishing houses then breaking out all over Manhattan. And Kurtzman also mid-wifed the birth of the Severin and Elder team: he told Severin that Elder’s inking technique, creating thick and thin lines with a brush, was more marketable than Severin’s penwork, so Elder should ink Severin’s pencil drawings.

Severin’s version of the teamup was somewhat different: “I couldn’t ink, and Willie was not good at drawing.” So Severin drew and Elder inked.

Kurtzman once evaluated the work of the team on the war stories they did: “When John and Willie used to draw these things together—boy, I just loved the results we’d get. Because John was about the best there was in drawing World War II. And Willie—John never really appreciated Willie because Willie would hurt John’s authenticity. John would draw four buttons and Willie would turn them into three-and-a-half, and that would kill John. And yet, Willie would ink his stuff with great clarity. His [Severin’s] stuff was very clear, and Willie, who had been through the whole scene, knew all about World War II. He got the flavor and he got the look. Not too dirty—these guys weren’t really crawling in filth, but they were bearded. John and Will were a great team for this stuff.”

Kurtzman saw Severin as superior in accuracy of detail; Elder, in clarity of visuals. And yet, he would eventually encourage each of them to go solo.

In 1947, freshly joined at the drawing hand, Severin and Elder sold their first collaboration, a crime story, to another famous team in comics—to Jack Kirby and Joe Simon, who were operating Prize Comics at Crestwood Publications. Eventually, Severin and Elder were producing stories about a Native American hero named American Eagle, many of which were written by Colin Dawkins, a friend with whom Severin had attended the Art Students League classes. Severin roped Dawkins into the process because he wanted the American Eagle stories to be redolent with authentic Indian lore and artifact, and he and Dawkins shared a dedication to that crusade.

When, in early 1950, Kurtzman began working for EC Comics, Severin and Elder followed him into the lair of William Gaines and his editor, Al Feldstein. Kurtzman started editing Two-Fisted Tales before the year was out, and the classic EC shop was quickly formed.

Interviewed by Bhob Stewart and Clark Dimond in 1985, Severin described the EC ethos: “Harvey knew who to give the jobs to. That's what made EC so different. You didn't just walk into an office: you were part of a group. You drank coffee with the publisher, you argued with the editor, you loaned cigarettes to the mail boy. And it showed! It showed! They shot the breeze one around the other and came up with ideas. Not in a formal manner. I mean, it wasn't ‘Run it up the flagpole—.’ These guys didn't have any flagpole. They didn't even have a flag. They just sat around and shot the breeze. ‘Hey, that was a good idea—.’

“You might go in there sometime and find two people in the office,” Severin continued. “The next time you might find eight. And it was the conversations back and forth over the editor's desk, with him saying, ‘Bill has an idea. Why don't you do this? Why don't you do that?’ And it went on and on and on all the time. Whether or not many good ideas came out of this is totally unimportant. The thing was the feeling was so totally different from any other comic company that, sort of, inside, you wanted to do your best for these guys. For the guys. Whereas you did your best for the other people because you wanted a paycheck—and wanted another script so you could get another paycheck. I wouldn't say I did it for the love of it, personally, but you wanted to do your best for them for some reason. It was like your own neighborhood gang. A cohesive group of young turks.”

EC was famous—notorious—for its horror comics, but Severin wouldn’t do horror stories. Like Kurtzman, he was uncomfortable with the genre: “I just couldn’t do it,” he told Groth. And he wouldn’t do sexy stuff either. Later, when Kurtzman was working with Hugh Hefner on Trump and, later, on the famously lascivious Playboy comic strip, Little Annie Fanny, Severin declined to help on any of these projects.

“I’m not going to work for Playboy,” he said. “It’s just that they’re pushing a way of thinking that’s totally opposed to—. I’m like the guy that says, ‘I buy Playboy. I don’t read it; I just look at the cartoons.’ I didn’t want to be in there, in the same category. ... I don’t think I should foster the [Playboy] idea. Not that anybody is gong to buy the thing because Severin’s in it, but Severin doesn’t want to be in it. That’s not my kettle of tea.”

Severin did a couple of romance stories for Prize Comics, but he was embarrassed by them.

“I knew what girls were, but I couldn’t draw them well,” he told Groth. “And [the romance books] had girls hugging guys and kissing—oh, God! I just purely couldn’t draw that. ... I just couldn’t draw girls. My girls looked real ... and these guys [drawing the romance books] were capable of drawing idealistic blondes. ... I had no interest in drawing pretty girls. I’d rather draw a horse.”

And nobody drew horses better than Severin. And the people riding horses look like they’re actually riding a horse, not just sitting there, perched on a saddle horn. His interest in Western themes may have originated in his fondness for the work of famed cowboy artist, Charles M. Russell. A girlfriend of his youth had showed him a book of Russell’s illustrated letters [Good Medicine].

“From then on,” Severin said, “I was totally, completely in love with Charles Marion Russell. He influenced me a lot. ... I liked him better than Remington. They can say all they want about Remington being an artist, but I find him pretty dead and uninteresting. Beautiful work and all, but ... Russell was—well, loose, and very accurate.”

Severin was renowned for his accuracy and the authenticity of his work—in every arena, but particularly in war stories and Westerns, where familiarity with equipage and accouterments gave the stories the thump of reality.

Michael Todd, editor for a time at Cracked, said: “One of the many great things about Severin was his eye for detail, so if there were ever any historical elements in a story, John would have the reference—in his head! Weapons, clothing, cars, buildings, furniture—anything from the beginning of time until, as he told me, about 1947, he wouldn't need any reference. Mark Evanier related that ‘Jack Kirby used to say that when he had to research some historical costume or weapon for a story, it was just as good to use a John Severin drawing as it was to find a photo of the real thing.’”

Confronted by such stories, Severin characteristically brushed them aside.

“Yeah,” he said when Groth urged him to recollect distant events for the sake of historical accuracy, “—when I look back on information about this guy Severin, I just go through a number of strange feelings. It’s like another person, sometimes. Oh, well. What the heck? I guess there’re some people who really get worried over this stuff. But that doesn’t bother me.”

Entering comics with very little background in the medium, Severin found an eager tutor in Kurtzman.

“All the artists got complete, absolute complete layouts [for the stories Kurtzman assigned to them]. Harvey was like a movie director. He knew exactly what he wanted, and he would write the story with the artist in mind, knowing what the artist would do. ... He taught me all of the things that I know about comics and that I knew had to be put into comics. He did it with his layouts, and working on it time after time, it finally got in through my thick skull. ... Sometimes it’s difficult to work with a man like that [who’d tell you exactly what to do and then criticize you if you failed to do it]. ... Working for him was delightful; it was terrible. It was just—. He brought out the best in all of us, and sometimes you’d like to break his damn neck. But, by God, he was good.”

When Kurtzman assembled a crew for the first issue of Mad, Severin was among the famed quartet: Wally Wood, Bill Elder, Jack Davis, and Severin were the regular Mad men. And Kurtzman had picked them for the assignment years before.

Bill Gaines has always strenuously implied that he invented Mad, that it was his idea: Kurtzman wanted more money, but Gaines paid by the book, and Kurtzman’s extensive researching for the two war titles he was editing and writing consumed so much of his time that he couldn’t do another book. At least, not another one like the two he was doing. So, said Gaines, he told Kurtzman to start a humor title, which, Gaines reasoned, Kurtzman could produce in a week, thus increasing his income.

But that, according to Severin, isn’t exactly how it happened. Kurtzman had been thinking about Mad for a long time, and Severin and Elder had been drawn into many conversations about a humor comic book during the Charles-William-Harvey Studio days.

Said Severin: “How we got talking about it was that I was drawing some of these screwball Westerns. I draw a lot to entertain myself, and I was drawing funny characters in a very realistic way. He asked me if I thought that sort of thing would sell. And I said, ‘Hell, I don’t know. I never tried it.’ He said, ‘Well here, I got this idea—.’ And then we started talking. And, gee, I thought the thing was great. And either then at moment or a day later, when Bill Elder got in on the conversation, we ended up, the three of us, talking about who Kurtzman would have in the book. ... We talked about the thing before he even brought the samples in [to show Gaines].”

Severin didn’t think of himself as a humorous cartoonist. He enjoyed doing it, but he did it differently than most. He believed that exaggerative, funny pictures undermined the humor.

“I think the thing is funnier if you have a serious [that is, comparatively realistically rendered] person getting pie in the face instead of a silly-looking jackass acting like a goon. He gets hit with a pie, you figure, ‘To hell with it. Who cares?’”

According to the master plan, Severin (and Wood and Elder and Davis) were in the first issue of Mad. But Severin and Elder had been divorced: each penciled and inked his own story. And they continued to do so thereafter.

Kurtzman encouraged Severin to ink his own pencils, and by then, Severin had inked himself a few times on American Eagle and other stories, including some in Kurtzman’s Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat, and through those experiences, he felt his penline became strong enough to stand on its own, without Elder’s heavier brush strokes.

Perhaps because of his experience with Elder (although their working and personal relationship was, Severin maintained, of the friendliest and most accommodating sort), Severin came to believe that divvying up the art chores was “a big mistake in the business. I don’t mean each individual instance has been a mistake. Sometimes it’s been good. But the idea of combining the artists, I mean the inker and the penciller, that’s a bad deal. You dilute both people.”

The EC gang was broken up in the mid-1950s when pressure from the Forces of Decency frightened the comic book industry into adopting a Code for content that forbade crime comics from depicting crimes and horror comic books from using the word horror in their titles. For a time, Gaines tried to keep his comic books alive, and Severin edited (and drew lots of) the New Two-Fisted Tales (which was rudderless until he took it on because Kurtzman was now fully engaged in producing Mad monthly in magazine format).

Many of the stories Severin drew in his title were written by Dawkins, who was by then a copywriter for the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency. In my mind’s rear-view mirror, they are all classic tales. Among them, were a series of adventures staring Ruby Ed Coffey, a bald, middle-aged but athletic character inspired by Little Orphan Annie’s Daddy Warbucks. Coffey commanded a tiny band of trouble-shooters that included the rough-and-tumble Cannon, based forthrightly on Roy Crane’s Captain Easy, and the dapper Dude—a band evocative of Doc Savage’s crew although Dawkins had never read any Doc Savage stories.

But Gaines’ efforts, well-intentioned and, in Dawkins and Severin’s case, beautifully executed, came to naught. He couldn’t keep the four-color magazines going. Two-Fisted Tales expired with No. 41, dated February-March 1955. The lead story, “Code of Honor,” was both written and drawn by Severin.

Severin went to work for Marvel Comics forerunner Atlas Comics, working on a variety of titles, ranging from The Incredible Hulk and Sub-Mariner to the popular war anthology The Nam. He continued drawing comics into his eighties, including work on The Punisher, Conan, and the controversial 2003 Rawhide Kid mini-series that re-imagined the Western hero as a gay gunslinger.

But Severin’s bread-and-butter for 45 years was Cracked, the most successful (that is, longest-lasting) of a bevy of an unabashed imitators of Mad.

Severin was there for the first issue of Cracked; dated March 1958, it appeared on newsstands on January 3. Severin did five of the 24 features; 9 of the issue’s 42 pages.

He had been assigned the cover for the first issue, but upon learning that the fee for doing the cover was minuscule, he surrendered his sketch to Bill Everett, whose painting, based upon Severin’s rendering; covered the magazine’s second issue.

Severin told Groth how his life-long tenure at Cracked began: “Sol Brodsky (longtime production manager at Marvel) and a friend of his put together a little off-and-on-again comic book business, and Brodsky phoned me and told me that Bob Sproul had contacted him and asked him if he would edit an imitation of Mad. He wanted to know if I’d be interested, and I said, ‘Fine.’ And that was it.”

Other early arriving sustaining contributors to Cracked included Russ Heath and Don Orechek, but Severin was there the longest—and oftenest.

“Ultimately, Cracked probably wouldn’t have survived if it weren’t for the talents of John Severin,” wrote Mark Arnold in the first of his two-volume history of the magazine, If You’re Cracked, You’re Happy. “There were many issues almost entirely drawn by him. For instance, Severin singlehandedly drew the entire 26th issue, except for a one-page Bill Elder reprint and a subscription ad by Bill Ward—a total of 50 new pages!”

Said Heath: “Cracked survived mostly due to Severin. He could do serious and crazy. No matter what it called for, he had a number of different drawing styles he could deploy. It was basically a one-man magazine for 40 years or something like that.”

Severin’s wife Michelina explained that Cracked had a separate payroll arrangement for Severin. “They would pay John regularly whether he did work or not. Sproul set it up that way. I know other people would have problems getting paid. They were slow paying. But John was a separate entity. We had an agreement, but no contract. He did the work and then he got paid.”

The magazine went through several publishers and editors, but Severin was always there. Almost.

When Mort Todd (aka Michael Delle-Femine) assumed the editorship with No. 219 in early 1986, there had been three issues without Severin in them. Todd was appalled. He was told Severin demanded too much as a page rate, but Todd found out that the previous honcho had tried to cut Severin’s rate and had demanded a kick-back. “John Severin would have none of this and turned the editor down.”

But Todd thought Severin was essentially the life-blood of the magazine, and got him back with a $500 page rate (“at a time when Marvel was paying around $125 for pencils and inks,” Todd explained).

Severin was back and remained with the magazine until it finally collapsed. Said Todd: “John Severin was a one-of-a-kind, dynamic personality with a full life and he left an amazing legacy that people will enjoy for generations to come. He has a wonderful family and a work ethic that kept him drawing to the end. He had recently drawn a fantastic cover for a periodical called Smoke Signals, that featured some Native Americans burning copies of Cracked.

“The final proof that Severin is Cracked and Cracked is Severin,” Todd said, “is the fact that the magazine thrived for years, under Mad's massive shadow—when Severin was contributing. In the early 2000s, when Cracked ownership changed hands, they couldn't afford Severin and the magazine went out of business. When it was relaunched a few years later as a slick, color magazine, Severin (and I) decided not to contribute because of the questionable editorial direction, and it bombed. Now that it has been sold again, it has resurfaced as a humor website, and quite entertaining, but as a magazine, since there is no Severin, there is no Cracked.”

Arnold asked the obvious question: “If John Severin was such a vital part of Cracked, why didn’t Al Feldstein lure him back to Mad, thus effectively putting [Mad’s only rival] out of business?” Apparently because Severin and Feldstein were not, as Michelina said, “exactly buddy-buddy.” When asked why he didn’t use Severin, Feldstein’s response was: “No comment.”

Besides what may have been a mutual antipathy, Severin enjoyed the greater opportunity and exposure at Cracked. At Mad, he might’ve had a 4-5 page feature in each issue, but at Cracked, he often did cover paintings and ten, fifteen, twenty pages a month, according to Todd.

And he enjoyed it all.

“I enjoyed the war stuff and the Westerns,” he said. “The humor stuff? It’s like a different department of the building. The humor stuff is over here, and that stuff is over there, and I never even thought to make a comparison. I feel the same about both of them.”

For greater insight into the character and accomplishments of John Severin—his charm, his ordinary uncommon decency in an age of cynicism and self-promotion, his irresistible self-deprecating sense of humor, only hinted at here in quotes taken from his interview with Gary Groth—visit The Comics Journal website, tcj.com. There, you’ll find the two-part 1999 interview in its entirety, including this story about a shotgun.

As usual, reveling in 19th century Mexican history, Severin had drawn with his customary seeming authenticity a story in which a band of bandits confront the local sheriff. Written by Archie Goodwin for Marvel’s Savage Tales title, the story turned on a sheriff possessing both a rifle and a twelve-gauge shotgun.

“I asked Archie,” Severin went on, “‘—Archie, they didn’t have those guns in those days. Where in the hell did you get that research?’ He says, ‘John, I got it from one of your old stories.’ Oh, gee! That was in a time when I would just do anything if it worked. He took it from me, thinking I was playing it straight. And the one time I cheated, he caught me.”

Groth is as passionate about accuracy as Severin, and when in their conversation he said that someone else, a then deceased artist, had colored something Severin thought he’d done, Severin backed away from his assertion, saying, “Let it go. What the hell.”

But Groth insisted that they should settle the question in order to be historically accurate.

“But how can we?” Severin said. “You’ve got one dead guy and one liar.”

Ahhh, but the lies he’s told—visual fictions that rest easily in the memory and heart, lies given such realism by his pictures that they become truths, pictures he’s drawn that will please the eye of the beholder as long as pictures last. Here are some more of them.

|

|

|

|

|

*****

ALAS, I DON’T HAVE any samples of Severin and Elder’s American Eagle work, but maybe my first visual aid above, Severin inking himself on a story about an Indian chief, will serve as a stand-in. The next page is from a Severin-drawn tale about the British army in far-flung Afghanistan (from which the Afghans eventually expelled the Brits, who didn’t understand how the natives fought). One of Severin’s favorite devices for these tales was to employ a tough but soft-hearted Irish sergeant who looked and behaved like Victor McLaglen in his classic roles, seen here in the second panel and the last two.

From the Two-Fisted Tales Severin edited, we next have pages from the stories about Ruby Ed Coffey. In the first, Ruby Ed himself is engaged in a sword fight with an unsavory bad guy; in the next, he’s giving one of his minions, Cannon, a boxing lesson when Duke comes in with a message.

The next item is a two-page spread are from one of the many Billy the Kid stories Severin did for Charlton in the mid-1950s. (The Kid looks a lot like Textron Quickdraw, seems to me.)

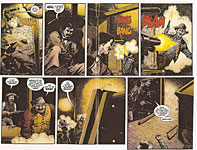

Our final examples are from Severin’s last published work, the 2011 Dark Horse Mike Mignola series, Sir Edward Grey Witchfighter. The story takes place in the Old West, one of the locales that Severin was most comfortable in. The first out-take is a double-truck spread from the first of the five-issue series, showing Grey in a gunfight against superior odds. Iconic Severin Western stuff.

Severin’s familiar style is evident, but he’s not drawing in the clean relatively unembellished manner of yore: compared to his art on the four Two-Fisted Tales covers we started with, Severin’s line here is not as continuous as it was then: it sometimes breaks into a file of tiny fragments, like John Cullen Murphy’s line during Prince Valiant’s last years, giving to the picture a delicacy, a kind of fragility, like fine china. And Severin in these Witchfigher pages gives body to his figures with fustian flourishes—bits and flicks of hachuring that model forms and give them volume and texture. If you like this treatment better than his former style, it’s a matter of taste. I like ’em both, and I rejoiced to see Severin out West again.

On our last exhibit, we have one of the last pages in the fifth and final issue of Witchfighter: pastoral and dreamlike, the scene fits the mystic ambiance of the story’s ending, but it also seems an appropriate last sighting of Severin, almost as if he’s depicted the Elysian fields of the Greek mythology, the final resting place of the souls of the heroic and virtuous, towards which he himself was heading in his last months. Maybe he even has a drawingboard out there in the ancient Greek afterlife. If so, he’s sure to be seated at it, pen in hand.