Inkslinging and Opinion Mongering with Rob Rogers

Political Cartooning from Pittsburgh

Rob Rogers, Pittsburgh’s star editorial cartoonist, was recently named Cartoonist of the Year in the seventh annual Opinion Award adjudication by The Week magazine. The accolade, however richly deserved, is just another instance of opinion, but it is beyond debate that, for many years, Rogers was the profession’s most eligible bachelor. He finally got married a few years ago to a beautiful and intelligent woman; and now, in the same spirit of consummation prolonged until perfection could be attained, he has produced one of the best editorial cartoon books ever. Entitled No Cartoon Left Behind: The Best of Rob Rogers (390 10x12-inch pages, b/w with some color; paperback, Carnegie Mellon, $39.95), the book is a wide-ranging retrospective of the cartoonist’s 25-year stint at the a newspaper that was once the Pittsburgh Press and is now the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Rogers estimates that he’s drawn an average of 240 cartoons a year in each of those 25 years: “That’s 6,000 cartoons!” he realized in alarm. But they’re not all in this book. “Despite the title,” he said, “some of those cartoons had to be left behind.”

Still, this tome may be the largest such collection published. But size is not its only virtue: it is also one of the most thoughtfully assembled compendia of political cartoons. In addition to a healthy helping of cartoons drawn between 1984 and 2009 (the year the book was published), the volume includes a brief biography (to which we’ll get anon), samples of Rogers’ childhood portfolio and his pre-professional cartooning on college campuses, and work from his earliest professional years as well as sketches made at the major political party conventions in 2004 and 2008, a pictorial essay disclosing the source of his ideas, and a few pages reprinting letters to the editor that castigate Rogers for his bad manners and worse taste in attacking conservative politicians. But the cartoonist’s choice among liberal candidates in a presidential race has been rigidly determined by considerations other than policy: “My choice for the Democratic nominee [in 1988 when the field was littered by at least half-a-dozen wannabees] was based on issues I really cared about—big ears, big lips, funny looking glasses, and goofy bow ties [i.e., Illinois Senator Paul Simon].”

With content like this stretching before us as far as the eye can see in this volume, we can discern the authentic life of a working political cartoonist, and we also get a short and jovial account of this country’s history for the last quarter century. Sections of the book delve into the reigns of four presidents and nudge up against the fifth (Reagan to Obama) and also contemplate, giggling barely suppressed, social and cultural issues over the same period—education, the ever-failing economy, reproductive rights, gun control, and on and on. What’s more—big bonus—Rogers has carefully dated and annotated every cartoon, reminding us of the issue that inspired each of them, thus enabling us to better appreciate the acerbic wit of his pictorial commentary.

The book, which took Rogers five years to assemble and annotate, is also intelligently designed with page layouts that are varied for both emphasis and diversity. Rogers is vociferous in thanking designer Paul Schifino (schifinodesign.com) for both his friendship and his infinite patience: Rogers told me that many times during that five years, he would finish selecting cartoons for a section and then, two days after Schifino had laid it out, Rogers would come upon another cartoon—a undeniable work of gargantuan genius and sheerly perceptive political insight—that simply must be included in the completed section. Schifino always complied.

Elegance does not end with layouts. Each of the 25 sections into which the content is sorted begins with a division page that is printed on color stock, heavier than the rest of the pages, an extravagance in book publishing. A short, one-page essay orients us to the issues addressed in that section’s cartoons. Although chronology is not the chief organizing device (the chapter on the economy, for instance, includes cartoons from 1986 to 2008 in no particular order), the issues—following the succession of presidencies—effectively impose chronology on the inventory. And the chronology enables us to watch Rogers as he matures as an editoonist.

His earliest work was pointed enough, but by the 1990s—and thereafter—Rogers was hitting hard with well-honed cartoon commentary. His forte is not so much the heavily-laden visual metaphor (although he is adept enough at this maneuver) as it is in casting his cartoons carefully and then setting his actors loose in situations that reveal the folly of life in America. His specialty may lie in pointing out the hypocrisy that’s inevitably inherent in the behavior of public officials these days, and since American public officials are world champions at hypocrisy, Rogers’ revelations are an accurate reflection of the country, its government, and the temper of the times.

In composing the book’s introduction, Rogers, a past president of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists (AAEC), tried to concoct a new way of describing what he does for a living, and I think he managed a telling whopper: “Hockey player meets rodeo clown,” he wrote. “Some days I am checking politicians against the boards hard enough to make them organ donors. Other days, it’s my job to step into an otherwise tragic environment wearing baggy pants, a red nose and giant clown shoes.”

He expands on this metaphor as insightfully as the figure of speech is itself inventive, but you’ll need to get the book to see how he does it.

I met Rogers in early February 1992, just as the year’s signal political event was getting underway—the race for the White House, which would eventually pit incumbent George H.W. Bush against a nearly unknown governor of Arkansas, who would win. In those days, I was traveling around the country as advance man for a teachers’ convention, and I took advantage of my peripatetic vocation to find and interview in nearly every city I visited the newspaper’s editorial cartoonist; the results were published in Jud Hurd’s quarterly journal, Cartoonist PROfiles (now, sadly, defunct). Here’s my report of the interview with Rogers, slightly modified to accommodate later developments in the job market for editooners.

*****

IN THE MIDDLE

OF ROB ROGERS' DRAWINGBOARD, surrounded by the debris of previous days—a couple

newspaper sections, some clippings, and sketches of all the Democratic

presidential candidates then slogging through the snow in New Hampshire—was a

rough of his cartoon for the next day, the drawing that appears just at your

elbow.  The

cartoon was based upon a weekend report about President Bush telling people

that the solution to the nation's health care problems was that we should all take

better care of ourselves. Rogers was flabbergasted at the news.

The

cartoon was based upon a weekend report about President Bush telling people

that the solution to the nation's health care problems was that we should all take

better care of ourselves. Rogers was flabbergasted at the news.

"Is that it?" he said. "Is that what Bush is going to tell these sick people? Hey—just take better care of yourself. And I had this picture in my mind of your mother or father shaking a finger at you and saying, 'You better take better care of yourself.' And I thought, How's that going to help the cancer patient or the person with AIDS? What is that saying to them? I had to narrow it down, so I picked a homeless family and had them sitting there with a sign—No Job, No Home, No Health Care. They're holding out a cup, and Bush is giving them his little lecture."

The cartoon, I observed. was a classic instance of what a cartoon is—a blend of word and picture, the verbal and the visual acting in tandem to convey a message. "Without that picture of those impoverished, homeless people, there is really no point to Bush’s speech,” I said. "Who you picture in that spot is what gives the cartoon its point. This makes the words and the pictures interdependent."

Rogers agreed. "The funny thing about political cartooning," he went on, "is that you don't really have to exaggerate that much. When you do other types of cartoons, you have to exaggerate. But with political cartooning, the politicians are so funny in-and-of themselves—or so ironic. For Bush to say what he said in the face of all the problems we're having is so ironic that simply repeating it is pretty much saying it all. It was just a matter of taking those two images and putting them together. And then the cartoon says, 'Hey—look at this: isn't this ironic?'"

We were sitting in Rogers' cubicle in the offices of the Pittsburgh Press. The presidential campaign was just beginning to heat up, and Rogers had worked late on a recent evening, developing caricatures of all the Democratic candidates. It was hard work, he said, because none of the candidates were readily recognizable by the general public yet: in addition to Clinton, virtually unknown nationally at the time, the Democratic candidates included Paul Tsongas, Bob Kerrey, Tom Harkin, Larry Agvan, Douglas Wilder, Tom Laughlin, Eugene McCarthy as well as Jerry Brown, the only one of the lot with previous national visibility.

I could see the problem. Public figures must be visible enough in the news so that people can recognize them in caricature. But once a person has been in the public eye for awhile, Rogers believes, the caricature of him needn't look like him.

"My caricature of Bush has become a symbol for Bush,” he said. "It doesn't really look like him anymore. But readers have come to accept my drawing as Bush. It stands for him. And so when I give him different expressions—smiling or frowning—I don't necessarily refer to photographs to catch changes in his appearance from one expression to another because my caricature doesn't look like him anyway. It's evolved. Now my caricature of Bush is not about his facial features so much as it is about his whole persona, his air—the whole facade."

Rogers explained how different cartoonists produce caricatures that look remarkably alike: "When a new politician comes on the scene, everyone flounders for awhile until he or she becomes a familiar icon—or until they see how Jeff MacNelly draws them," he said with a laugh. "Sometimes a unique symbol will emerge—like Jimmy Carter’s toothy grin or Ronald Reagan's hair—and become a key identifier. The caricatures often begin to look the same everywhere. That isn't necessarily good, but I think that cartoonists have a knack for caricaturing the same things about a face, and that can't help but produce similar caricatures."

Exaggeration is the key to a good caricature, he believes. But there's a trick to determining which features to exaggerate.

"When I'm developing a caricature," he said, "I don't look at a photograph. Instead. 1 envision the face in my head. And whatever it is that I remember most about that person's appearance, that's what I start with. I'll draw what I remember about them. And then I'll go back and look at a photograph and adjust my drawing accordingly—however I think I need to exaggerate. But I think it's very important that what you remember visually is what you need to exaggerate. If you remember their glasses or their nose or their ears, those are the things you need to jump right on. From there on, it's just a matter of refining it. I think some caricaturists look too much at a photograph. And then they finish with a portrait instead of capturing the essence of their subject."

And here, by way of capturing essences, are a few caricatures of Rogers—two by him, and one by me—and some others in Rogers’ menagerie.

|

|

ROGERS HAS BEEN DRAWING editorial cartoons for the Pittsburgh Press since the summer of 1984 when he joined the staff after getting a Master's Degree in Fine Arts at Carnegie Mellon University. Born in Philadelphia, he grew up in Oklahoma. He drew cartoons in junior high and high school, but it wasn't until he started drawing editorial cartoons for the campus paper at Oklahoma State University that he began thinking of doing it for a living. Then after spending two years at OSU, he transferred in 1979 to Central State University in his home town, Edmond, because CSU had a better art department, he felt—and there was an instructor there who taught cartooning.

Hall Duncan offered a course in Editorial and Cartoon Art every other semester as part of his advertising curriculum. Based upon concepts embodied in the old correspondence course lessons, the cartooning course required students to explore the field. They clipped magazines and newspapers to assemble examples of the different ways cartoons are used—in advertising, gag cartoons, comic strips, editorial cartoons, and so on.

"We all had to keep a scrapbook of cartoons that showed different panel compositions, styles, and so forth," Rogers explained. "Then we developed our own comic strip character. And we'd draw a face with as many different expressions as we could come up with. That kind of thing."

When it came to instruction in drawing, Duncan took his students where they were, looking at their work and critiquing it. Rogers took the course twice, the second time as an independent study studio course.

He graduated in 1982 and came to Pittsburgh to attend the graduate school of fine art at Carnegie Mellon University. "I knew that it would probably be tough to just walk out and get a job as a cartoonist," Rogers said, "so I thought I'd get a Master's Degree and then I could teach college if I had to."

During his last semester, he started doing editorial cartoons for the University of Pittsburgh's Pitt News. The CMU paper already had too many cartoonists; he figured he'd get better exposure in the Pitt News. And his hopes were realized: the graphics editor of the Pittsburgh Press, Bruce Baumann, saw Rogers' cartoons and sent word that Rogers should call him. And that led to a happy collision of intentions.

Rogers had been sending a portfolio of his Pitt News cartoons to newspapers around the country—but not to Pittsburgh papers, which he planned to call on in person. One of the mailed portfolios landed at a Memphis paper, from whence Angus McEchran had come to join the Pittsburgh Press as editor. A Memphis friend sent him Rogers' portfolio because he knew McEchran was looking for an editorial cartoonist. The Press hadn't had a political cartoonist on staff for twenty-five years.

"Angus sent me a letter," Rogers said, "which I received the day before I was to come in for an interview with Bruce. And I was very confused. It turns out they had both seen my work and wanted me to come in for an interview, each without knowing the other had seen it. I felt very flattered and lucky. Of course, I feel like I have to make up another story to tell young cartoonists who visit me so they don't get the idea you can just wait by your phone."

Rogers was hired on a trial basis for the summer.

"They wanted me to do three cartoons a week," Rogers said. "I hadn't been doing cartoons on a daily basis, so they wanted to break me into it slowly. I was to work in the art department the other two days. I graduated on Monday, and they had me in here on Tuesday— no time off. So I did three cartoons, and then it was Friday and time to do an illustration. And it was one of those illustrations where you have to use a ruler and a rapidograph pen—some kind of infograph. And it took me forever to do it. I was used to free-hand drawing, no rulers or straight lines. So the next week, I did five cartoons! I just kept coming in with ideas, and I said, 'Do you mind if I just do five cartoons a week?'"

I laughed: "And what they didn't know is that you were just trying to avoid duty in the sweatshop of graph-making."

"Yeah," Rogers laughed too. "Actually, it worked out very well. By the end of that three-month internship, I’d done enough cartoons to find my style a little, to be more consistent."

He also found his footing. Doing a daily cartoon on demand was, at first, a daunting assignment.

"I remember that first day," Rogers said. "I went in and showed Angus my sketch, and he said, 'Okay, I have to leave here by five o'clock and I want to see the finished drawing before it goes in the paper.' I was used to spending as much time as I needed on a drawing. Suddenly, I had to do the drawing in four hours. To me at that moment, that seemed impossible. So I started drawing furiously. I finished by four and took it in to Angus.

"The next day, I was a little less nervous," he continued; "next day, a little less. And after the first week, I didn't have to show him the finished drawing anymore: he got the idea that the sketch was pretty close to what it was going to look like. So now, I just show him the sketch and get it approved."

Getting editorial approval for his cartoon does not mean that he must produce a cartoon the editor agrees with (although he usually does). I asked if the paper would print a cartoon his editor disagreed with.

"As long as it didn't run on the same day as an editorial expressing an opposing view," Rogers said. "It would be a little confusing to the reader. But since my name is signed to the cartoon and it appears on the opinion page, my editor lets me draw pretty much what I feel."

I asked if his editor ever suggested subjects to him—subjects but not viewpoints.

"Sure, sure," Rogers said. "And it's always understood that he's just suggesting a topic, and if I don't feel it's a subject I want to address that day, that's fine. But he never suggests ideas. And normally, if he suggests a subject, it's probably something in the news that I was thinking of doing sooner or later anyhow."

THE PRESS IS AN EVENING PAPER, and Rogers' deadline is 7 a.m. But he works during the previous day and tries to finish by five or six o’clock when everyone else in the office goes home for the day. "That gives me some semblance of a normal life," he explained. But sometimes—if he has tickets for a show that night and must leave the office before he can finish his cartoon—he returns later in the evening to finish.

He arrives at his office in the morning—sometime between 9 a.m. and noon, depending upon how many times he hits the snooze alarm that day. The daily editorial board meeting is at ten o’clock, and that gives him something to shoot for.

In the mornings, he reads through the newspaper and mulls over ideas. "If it's a good day, I have a sketch done and approved by noon," he said. "If it's a slow day, it'll be after noon. After I get it approved, it takes two to four hours to finish it, depending upon how much detail I have to put in—how many caricatures I have to draw."

When inking his drawing, Rogers begins with a brush. and after outlining all the figures and backgrounds, he applies the developer to the chemically-treated Duo-shade paper, using a large watercolor brush. Then he goes in with a crowquill for the crosshatching and finishing touches.

He admires the work of Jeff MacNelly and Dick Locher and recognizes their influence in his work. Rogers sees MacNelly as inspirational to newspaper editors, too: "He was at a small paper, and he won the Pulitzer. And he was young. Suddenly a lot of small papers said, 'If the Richmond News Leader can have its own cartoonist, why can't we?' That sort of started the whole thing, I think."

Not that getting into political cartooning was any easier then than it is today, with editoonists losing staff positions by the drove.

"It's a very tough field to get into," Rogers said, adding that a lot of newspapers even then, 18 years ago, were folding or merging. What Rogers said then is still applicable today, in spades: "There are a lot of good cartoonists out there who are not working for major newspapers. But I don't think that's the only way to do cartoons. You can work for small daily or weekly publications in your home town. You can do it part-time. You can create your own market by finding magazines or papers that deal with subjects you're interested in. There are so many avenues for cartoonists. But there are a lot of talented people out there looking for work, too.”

Many more today than then.

"YOU HAVE TO DRAW CARTOONS for your own enjoyment first," Rogers mused. "You have to really love to do it. Otherwise, you'll never stick with it long enough to make it."

I agreed. "It's easy to say that you have to love to draw," I said. "but there's a full load of meaning in that expression. If you come up with an idea that involves a complicated drawing, unless you like to draw, you won't put that idea forward."

"Yeah." Rogers said, "you're not going to want to spend the time."

Rogers sees the editorial cartoonist as something of a crusader, speaking for minority voices "our there" that don't have a two-by-four inch soapbox every day to speak from. And he sees a distinct function for humor in the crusade:

"Humor is one of the best ways to get your point of view across," he said. "Once you've got someone laughing, they've let their guard down and they're going to be open to what you're saying in the cartoon. Whereas if you're hitting them over the head with an idea, all they'll get is a sore head."

"Have you browsed much through the cartoons of the 1940s?" I asked. "People like Daniel Fitzpatrick. I can't remember seeing a Fitzpatrick cartoon that was funny. They were all pretty grim things."

"Yes—most of them weren't funny," Rogers said. "And I think that the face of editorial cartooning has really changed over the years. I think Pat Oliphant had a lot to do with that. But even taste in humor has changed in America—Mad magazine, 'Saturday Night Live'—all these things have influenced us over the years and have changed the kind of humor we like. I can do cartoons now that couldn't be done in the forties. Oliphant introduced the gag cartoon into political cartooning. And that's probably one reason I'm doing editorial cartoons right now because I don't think I could draw cartoons the way they were drawn back then. Those were, to me, political illustrations—with labels and so on. Heavy messages."

"Visual metaphors, really," I said. "There was a point of view there—you could see that—but they had no dynamic. They were like billboards."

"Like a logo almost," Rogers said. "You looked at it and said, 'There it is.' You didn't laugh. Maybe it moved you in some way. I think that humor is definitely the big difference in editorial cartooning today."

We talked a little about the one dimensional nature of political cartooning. "A cartoon usually assaults its target as if there were no other legitimate point of view," I observed, "but most issues don't reduce to such simple black-and-white circumstances. With almost every issue, there are alternate points of view that are viable. How do you deal with that?"

"You have to figure out how you feel about the subject, first of all," Rogers said. "An editorial cartoon is not an objective analysis of an issue. It's subjective. We're paid to be subjective."

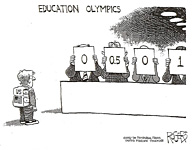

I took up his cartoon from the previous day. It showed an

American school kid being rated by Olympic Judges (the Winter Olympics were

running that week).

"Here's this education cartoon," I said. "On the face of it, the cartoon proclaims that American education is not doing well. So who is the villain in this situation? There could be a whole list of villains because it is a very complex issue. When you did this cartoon, in your mind, who was the villain? Who were you jabbing?”

"One thing about that cartoon," Rogers said, "is that I've done a zillion cartoons about how bad American education is. There's a big story on it a couple times a year. So one consideration when I started this cartoon was—how do I make it different from the ones I've done before? In a lot of my previous cartoons on the subject, the Bush Administration has been the villain—Bush being the ‘education president’ and not doing a very good job of it. But I didn't want to take that angle this time, so I tied it to the Winter Olympics—holding up score cards. And obviously, we're not doing too well. But what I'm trying to show with this cartoon is not so much who the villain is but who the victim is. And the child here is clearly the victim of a bad education."

"So you're just giving the sleeping dog a kick," I said.

"Right, exactly right. I don't think any cartoon I'm going to do is going to change the world, but if I can get Ma and Pa Smith to think about an issue—to talk about it with their family, maybe to put the cartoon on their refrigerator door—that is what I'm trying to do. That's the best I can hope for."

"You're keeping the rabble aroused," I said. "I do some editorial cartoons for the newspaper of an educational association, and the issues are always complex. The editor looks at my cartoon and says, 'Well, what about this other point? What about this? And what about that?' And I say, 'Listen—this is a cartoon. It can't be a multi-dimensional analysis of a situation.' I did a cartoon about political correctness, and he agonized over it: all his friends were politically correct, I think, and he didn't want to offend them. And I said, 'The point is to offend them. That's the whole exercise. To make them mad.' But he didn't want to make them mad. And if that's the case, you don't want a political cartoonist in your paper."

"I think you're right,” Rogers said. "The point is to offend them: to make them angry, to make them think. But not just for the sake of offending someone. You can't come into the office and say, 'There's nothing to draw about today, so I'll just make someone angry.' I don't think that's a valid reason for a cartoon."

But Rogers likes to get letters from angry readers. "I think they're a better barometer of where I'm going than letters that say, 'Oh, I just loved that cartoon,''' he said. "Then you think: 'Wait a minute. I'm doing something wrong here.' Especially when politicians phone to say how much they liked a cartoon!"

Like most political cartoonists, Rogers steers clear of politicians socially. He attends a number of civic functions, but he assiduously avoids fraternizing with the politicians in attendance.

I sympathized with his predicament: "One of the great truths of human relations: if you have any feeling for people at all, if you know individuals, you tend to like them. It's hard to make them villains then."

"I can't afford to like them," he said with a laugh. "It would jeopardize my job."

AND NOW, a gallery of Rogers, arranged, more or less, in chronological order (with occasional comment from yrs trly).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|