ROGER ARMSTRONG REVISITED

A Champion Cartoonist Talks Cartooning

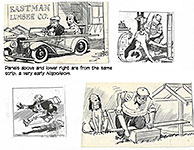

ROGER ARMSTRONG—CARTOONIST (strips and comicbooks), animator, and painter—had an effect on my life without his knowing it. I knew almost nothing about him when we “met.” Our meeting via letter was prompted by Shel Dorf, founder of the San Diego Comic-Con, who told me in about 1990 that Armstrong was selling original art by Clifford McBride for his famed Napoleon comic strip. Armstrong had taken over the Napoleon strip at the death of McBride, and he apparently wanted to get rid of some McBride originals. Shel gave me Armstrong’s address, and I wrote him, asking for particulars—price, etc. Turns out Shel was only partly correct: Armstrong was indeed selling original Napoleon art, but it was for his Napoleon, not McBride’s.

|

|

|

That’s okay, I said: I’ll be happy to own one of yours. Armstrong’s version of Napoleon was so accomplished an imitation of McBride’s manner that it was nearly impossible to tell the two versions apart.

And that inaugurated a friendship that lasted until Armstrong’s death in 2007.

I

bought an Armstrong Napoleon from him, and soon thereafter, he sent me

some McBride Napoleon originals—not a strip but individual disconnected

panels from some strips. McBride was in the habit of re-using panels from

published Napoleon strips, re-arranging the panels to tell new jokes.

And Roger had sent me a handful of those errant panels.

As our correspondence meandered on, we discussed cartooning things, and then Roger sent me a complete, intact, McBride Napoleon strip. Then he wrote me, saying: “The reason I sent along that early McBride original is because I sense a real affinity with you, and I want those McBride treasures to have good homes. I deplore this ‘wheeling-dealing’ that goes on—the feeling I get from all this is that most people who are involved in selling and trading are not really aware of the great quality inherent in these works of art and view them mainly as commodities. You convey your sense of reverence and should be the true repository!! There! I’ve said it, and I’m glad!! Enjoy, enjoy!”

In the same letter, Roger proposed a joint project. Several months before, Walter Foster, publisher of numerous how-to art books, had published Roger’s how-to cartoon book. And Jud Hurd, publisher of Cartoonist PROfiles, had phoned Roger, saying he would like to run an article in PROfiles about Roger, his career, and the book. Would he write such an article and send it in?

“Well, Harv,” Roger said, “I have made several attempts to write something and have ‘bombed.’ I can write quite well as long as it’s about someone else but not about myself!”

Then came the mutual project proposal: “How would you feel about picking my brains with a project such as I’ve outlined here in mind. Jud asked for it so it’s not as though it’d be coming in cold. It would solve a formidable problem for me.”

And so I interviewed Roger by telephone. Then I wrote up an article for Jud Hurd and sent it to Roger, who approved it. Then Jud published it in Cartoonist PROfiles No.90 (June 1991); here it is—:

Drawing Comic Strips with Roger Armstrong

Roger Armstrong has drawn cartoons more ways than most. A stylistic virtuoso, he's drawn comic books in the styles of Disney, Warner Brothers, and Hanna-Barbera. He's drawn comic strips as disparate in manner as Clifford McBride's classic Napoleon, Marge's Little Lulu, Disney's Scamp, and Ella Cinders, a continuity. With that gamut of experience, Armstrong is the logical choice to author a book on how to draw comic strips, and that's exactly the title of the book he's done for Walter Foster Publishing.

At

this point, logic wavers. Armstrong has also worked in animation as in-betweener,

animator, and story director, but at 73, he brings more to the book than his

experience in all sorts of cartooning. An accomplished painter in

watercolor and oil, he's served as director of an art museum, and he holds an

honorary doctorate in fine arts from the Art Institute of Southern

California.

Logic reasserts itself: an instructor for over 20 years in all phases of art from watercolor to figure-drawing to cartooning (mostly at the Laguna Beach School of Art), Armstrong informs the pages of his book with the practical experience of teaching as well as cartooning. A graduate of Chouinard Art Institute, he brings to cartooning the background of a artist fully trained in the classical mode. But it didn't begin that way.

It began with Zim and Clifford McBride.

Armstrong at about eleven years old was enthralled by the drawings of the great Eugene Zimmerman, whose book on cartooning he borrowed so often from the library that no one else could check it out. In recognition of his devotion to Zim, the librarian at last told him not to bother to bring the book back every two weeks for renewal: "Why don't you just keep it," she whispered to him, glancing furtively around to see that no one overheard her. (For more about Zim, visit Opus 303 for a review of the book The Lost Art of Zim.)

Young Roger also took the famed Landon Course when he was in high school, and just about that time, Napoleon debuted (official starting date, June 6, 1932; for the history of Napoleon, see Harv’s Hindsight for November 2014). Drawn with an exuberant pen and great verve, McBride's strip focused on a roly-poly bachelor and his giant pet dog— Uncle Elby and Napoleon. Elby is forever dogged (pun intended) by misfortune: if his own bumbling doesn't frustrate his plans, the clumsy meddling of his affectionate over-sized hound does.

Elby was patterned visually after McBride's uncle, Elby Eastman, who was a lumberman in Platteville, Wisconsin; Napoleon was inspired by the cartoonist's dog, a St. Bernard, but in rendering the creature, McBride slimmed him down until he looked more like an Irish Wolfhound. This was before cartoonists had made an accepted convention of talking animals in strips that also featured humans, but Napoleon needed no words: McBride made the dog's face talk, giving it a range of expression that spoke volumes.

"I saw Napoleon when it started in the Los Angeles Times," Armstrong recalled, "and I thought it was one of the most wonderful things I'd ever seen."

And when he found out that McBride lived in Altadena on New York Avenue, he resolved to meet the cartoonist. He took a bundle of drawings and knocked on McBride's front door.

"He was very gracious," Armstrong told me. "And so I went to see him every so often. He moved from the New York Avenue place to the foothills. He had a little house that was separate from the main house, and that was his studio. He was an accomplished concert pianist, by the way, and he had a concert grand in there. Well, I haunted the poor man. I'd go and lurk by his side and watch him draw, and he was very, very kind to me. Sometimes I'd have dinner over there. That's where I found out you could have spaghetti served to you by a Japanese house boy. And Clifford showed me what pen he used— Gillott 290— and all this stuff, and bit by bit, he let me do a little on the strip— simple backgrounds, and he let me do his lettering."

I asked if McBride drew rapidly. "That marvelous sketchy style," I said, "— you couldn't get the effect of such breezy abandon by drawing slowly, I wouldn't think."

"Oh, no," Armstrong said. "Clifford was so fast. The guy was incredible. A little known fact about Clifford is that when he pencilled the strip, he did not pencil it loosely. He pencilled it in exactly the detail that you see the final pen-and-ink work. It was unbelievable. I mean, he did every single bit— all the shading and everything— with the pencil before he went in to it with a pen. And he grabbed the pen way out at the end of the holder— far away from the pen point— and he used to ink that way.

“The

control he had was absolutely unreal. He knew exactly what it was going

to do— where it was going— and he put it down. Not that he inked every

pencil line as it had been drawn; he didn't. He was very fast. He

developed tremendous speed and freedom of line, and, of course, I did, too,

watching him. And that's the way I draw. I grab the pencil way out

by the eraser. And I ink that way,  too. And I paint watercolors the

same way. And I tell my students, Don't grab it way down at the end where

you'll get ink all over your fingers; grab it as far back as you can conveniently

control it."

too. And I paint watercolors the

same way. And I tell my students, Don't grab it way down at the end where

you'll get ink all over your fingers; grab it as far back as you can conveniently

control it."

Armstrong sometimes helped McBride with his jigsaw puzzle. "He was a great one for re-using old strips. He'd cut his strips into pieces and put them into an envelope, and then if he needed to put together some stuff in a hurry, he'd shake it all out and piece the panels together in a new arrangement. So he'd have me cut and paste sometimes, and he'd let me do the extra drawing in the backgrounds to fit the pieces together."

THE VISITS TO MCBRIDE'S STUDIO continued through Armstrong's high school and college years, and he'd sometimes go with McBride to Bill Ortman's Gambrinas on Euclid Street. "All the newspapermen— artists, writers— they used to hang out there. And Clifford had a special table in the back, and he and Ned Seabrook and all his cronies used to hang out there, and that's where I'd go and sit and talk with them. You know, big stuff to a twenty-year-old. Neat place."

A few years later, such acquaintances led to Armstrong's first comic strip job. A cartoonist friend told him that Fred Fox was looking for someone to draw Ella Cinders during Charlie Plumb's illness. Fox had inherited the writing chores on the strip when its co-creator Bill Conselman died only a few years after the strip started on June 1, 1925. As originally conceived, the strip gave the old rags-to-riches fairy tale a modern setting, retaining the evil stepmother and selfish step-daughters— over whom Ella triumphs by becoming a movie star despite them.

During a three-month stint on Ella, Armstrong met cartoonist Chase Craig, then an editor at Western Publishing, who, a year or so later, summoned him to Western where he joined Craig to produce the second issue (and many subsequent ones) of Looney Tunes and Merry Melodies. Starting in 1941, Armstrong first drew "Porky Pig" over Craig's scripts, then he wrote and drew "Sniffles and Mary Jane." Then when NEA picked up Bugs Bunny as a Sunday comic, Armstrong inherited the strip after the first six (which were done by Craig) and wrote and drew it for almost two years before Al Stoffel and a couple others took it over.

Armstrong did Bugs Bunny features again at various intervals over the years, so he's been associated with the Warner Brothers star for almost as long as the wascally wabbit has been around. He agrees that Bugs is THE American comic character: he could never have been invented in the British Isles or in France. "He's brash, self-assertive, self-confident," Armstrong said, "— the prototypical American."

Armstrong's job at Western led to his learning animation.

"The War was raging in Europe, and the draft board was picking off the cartoonists at Western and sending them off to shoot rifles," he said, "and pretty soon, Eleanor Packer, Craig's boss, looked around and saw that I was about the only one left. She was afraid I'd get called up pretty soon, so she got me a job with Walter Lantz, who was doing stuff for the U.S. Navy. And since that was considered vital war work, I wouldn't be drafted, she thought. So I started as an in-betweener, then did breakdowns, and finally became an assistant animator.

“But I was still doing the comic book stuff for Western, too. That was the deal. I'd punch in at the Lantz Studio at 8 o'clock every morning, work there all day, then go home and draw comic books until midnight. That went on for about a year until I was drafted— on Valentine's Day, 1944."

After the War, Armstrong returned to Western where he did a lot of Disney features for a while— "Little Hiawatha, The Little Bad Wolf," he remembered, "I did a whole bunch of Little Bad Wolf, some of the best drawing I ever did. I had a real affinity for that stuff."

And then he went to Chouinard Art Institute on the GI Bill.

Finding he couldn't make ends meet on the government's allowance, he continued drawing comic books.

"I'd go over to Chouinard about 5 o'clock in the morning and sit in the backseat of my car in the parking lot with a drawingboard and draw Bugs Bunny comic books until school started. Then I'd go to class and then go home at night and do more comic books. Pencilling only, this time— no inking."

|

|

|

|

JUST AS HE WAS ABOUT TO GRADUATE from Chouinard, Fred Fox called again. The syndicate wanted Plumb to retire, and Fox needed someone to draw Ella Cinders. Fox offered the job to Armstrong with the proviso that he take Plumb's assistant, Joe Messerli. Armstrong agreed to the stipulation, although at the time he thought an assistant would be superfluous.

"I had a bad habit of thinking of myself as the fastest draw in the West— which I partly was— and inexhaustible," Armstrong said. "But Joe turned out to be one of the blessings of my life, my absolute mainstay. I can't tell you how wonderful he was. And as I began to encounter the problems of drawing that thing— Ella in particular— I cannot tell you how happy I was to have Joe at my side."

When Ella began her life destined to be a motion picture actress, she had been modeled after Colleen Moore, a popular movie star of the day— the hair-do, the eyes. And she was, Armstrong said, undrawable.

"Why?" I asked.

"Because there's nothing to hang on to," he explained. "She's like Mickey Mouse. You see, you look at Goofy, and Goofy has all kinds of facial structure. But Mickey has no structure. And there's no structure to Ella: she's absolutely flat. You have to really become accustomed to the space between the eyes, the two little dots, and the mouth— the way that fits into the whole face. You almost have to measure it off with calipers. And you miss a fraction of an inch, and you've missed it altogether."

Plumb had faced the same predicament. And he had overcome it with outrageous ingenuity: he had invented the Ella Cinders Machine.

"The Ella Cinders Machine was a contraption Charlie Plumb rigged up with pipes and sash weights and mirrors," Armstrong said. "It was a sort of overhead projector, and you could put a drawing of Ella into it and project it onto the paper and reduce the size of the image or make it larger. It was a magnificent invention, an absolutely ingenious device. And it was the only way I could draw Ella— by tracing her from the projected image. There were two perfect drawings of Ella— a profile and a three-quarters view. No full face. So we projected one of those drawings onto the strips. We used only a profile or a three-quarters view in every strip that was drawn. In various sizes. I let Joe ink the main characters because when he came to me that's what he'd been doing for Charlie. And I did the backgrounds and all that stuff— the figures. But I let Joe ink all the faces."

"That's funny," I said. "Usually a cartoonist with an assistant does just the reverse. I understand Al Capp, for instance, let his assistants draw everything but the faces of the main characters. He never let them draw Abner or Mammy Yokum or Daisy Mae."

"Well, Joe had more experience with Ella and Blackie and Patches than I did," Armstrong laughed.

The Ella Cinders Machine was only the latest in Plumb's solutions to the problem of drawing Ella, Armstrong told me; before that, Plumb had used rubber stamps.

"At one point, he had rubber stamps made of all the main characters, of their faces in every size and from every angle he thought he would need. And he kept `em in this huge cabinet, specially built for the stamps. And if you wanted Ella turned left, one inch high, they were all categorized in the cabinet, and you'd go and pick out the one you needed and stamp it on an ink pad with photo-blue ink on it, and you'd carefully stamp the strip with it where you wanted the face. And then you'd ink it. Very cumbersome way to draw a comic strip," Armstrong chuckled.

"Yes, but it's a classic," I said. "You always hear cartoonists muttering about the repetitive work in strips. I remember one guy: noses, he said, how I hate to draw noses— I spend my life drawing noses. And you think about it, and you do: you spend your life drawing noses and the rest of the faces of the characters you're stuck with. And Plumb's rubber stamps— they're almost too perfect an evasion of the onerous. Classic."

AT JUST ABOUT THE TIME he started working on Ella, Armstrong got another phone call— this one from an old classmate from his undergraduate days at Pasadena City College. It was Margot McBride, Clifford's second wife, who had worked on the student newspaper with Armstrong long before she knew McBride. She remembered that Armstrong had helped McBride on Napoleon.

It was 1950, and McBride had just died. Margot wanted to continue the strip and engaged Armstrong to do it. Suddenly, he was doing two comic strips at once. And each one was rendered in a distinctive but wildly different style.

"How did you do that?" I asked him. "I can understand being able to draw in different styles. I can do that. But I have to think about it a lot as I'm doing it, and when I look at the drawing afterwards, I'm likely to find mistakes— a thumb that's drawn in the wrong style, Style A not Style B. And I would imagine that you can train yourself to avoid such slips if you take up a new style and do it steadily, but you were doing two styles simultaneously— flipping back and forth. How did you manage it?"

|

|

"No wonder I'm schizophrenic," Armstrong quipped. "Seriously, I just changed hats in the middle of the week, changed my philosophic approach— my attitude about inking, for instance. Ella was done very meticulously, as if it was carved out with a wire, whereas Napoleon was fast, fast, fast. Was it Shakespeare who talked about sea change? The only thing I can say is that I changed. Right in the middle of the week. I spent half the week on one strip; half on the other. A little more on Ella because it was more meticulously drawn. It wasn't that big a deal. I'd done stuff in other styles— Porky Pig, Bugs Bunny. And I was painting at this time, too— landscapes."

I wondered about the different ambiance in each strip: "In your book, you say the strip cartoonist must create a whole world, including the people in it. You have to believe in that world. And there you were, living in two different worlds. How did you feel in Napoleon's world? In Ella's?"

"Schizophrenic again," Armstrong said with a laugh. "To tell the truth, the McBride world, the world of Napoleon, was not a real world in the sense that it had any depth. Berrydale, which is where Uncle Elby lived, was a very ephemeral concept. But the world Ella lived in, which had no specific name, had more content to it. When we got her into an adventure, she moved in a much more real world. And in Napoleon, we were aware of people in the world there, but they did not constitute in my mind a real world. Berrydale was a fantasy."

"Funny you should put it that way," I said. "I've always felt the same about Napoleon. Every time I see a Napoleon strip, I feel as if I am looking through a kind of gauze screen and seeing a bright, hot, humid August afternoon where you can hear the faint buzzing of some kind of insect in the trees and all other sound seems distant and removed, and nothing really moves around very fast. A dream world, a languorous summer afternoon sort of place. Somnolent, relaxing. But not, as you say, altogether real."

Messerli and, later, Mort Taylor, helped Armstrong in the production of Napoleon as well as Ella Cinders.

"They researched for me," Armstrong said. "When I first took over the strip, I referred to Clifford's stuff a lot. And they'd go through all the release sheets and find specific poses and put them aside for me so I could draw from them. Eventually I didn't need to refer to them anymore. I'd learned the drawing well enough not to need `em.

"Napoleon

is one of my two favorite subjects," he continued. "I

absolutely adored drawing him: he moved so freely off the pen onto the

paper that it was just a sheer joy. Another favorite was the Inspector in

the Pink Panther comic books. I think he's one of the most beautifully

designed characters. I drew him later on when I was doing freelance work

for Western. But Napoleon just flows out of the end of my pen. I

can draw him practically with my eyes closed.

“Some characters I had to labor over. Ella was probably the worst. I loved her dearly: she was a dear, sweet girl. But she was hard as hell to draw. And during the time I drew her, incidentally, I subscribed to Mademoiselle magazine and Seventeen, and I used to pick up dress patterns at the dress shop. When you're dressing a girl character, you have to stay up on that stuff."

I asked him if Fred Fox had ever scripted situations in Ella that were undrawable, a tendency not unprecedented when strips are produced by writer-artist teams (even when, like Fox, the writer can also draw).

"Only once," Armstrong said. "It was during the first week of dailies, and he never did it again. But it happens. Once I was doing a ten-page Bugs Bunny story, and the writer— it was his first story for comics— wrote for one panel: Bugs comes into the room, picks up a vase, does something with it, and goes out again. One panel. Three actions. But to the writer, it was perfectly logical to have all that action in one panel."

"He'd probably learned to write by going to the movies," I said, "and in a movie, all the action takes place in one panel, that big square one on the wall."

In his book Armstrong says it's easier to do a continuity strip than a gag strip. I asked him about that.

"That's an entirely subjective statement," he said. "It's easier for me to do continuity because I'm not a very good gag man. For some people, continuity strips aren't easier. Guys like Phil Interlandi, for example— whose mind is nothing but a gag file— he would have no problem with a gag strip; he could just knock `em out. But it's easier for me to plot a story and write dialogue than to come up with gags."

Although Fox wrote Ella for most of Armstrong's stint on the strip, Armstrong wrote it for a couple years before Bill Conselman's son stepped in to write the last year or so of the strip.

"When I was plotting the story," Armstrong said, "I'd work out a six-week synopsis. Plotting is like writing a novel: I'd just tell a story and not worry about the daily installments. Then I'd break it down into weekly segments, and then I'd write the dialogue which broke it into daily strips. Some guys actually write their stories on little pieces of paper that they pin on a bulletinboard in front of them. Then they take `em off one by one as they use `em up.

"And if you're smart," he continued, "you always know where you're going before you start to ink your final drawings. I learned that the hard way at Western: once I inked several pages of a story I was doing even though I hadn't figured out the ending, and then, half-way through inking, I realized I couldn't finish the story I had in mind in the six pages they'd allowed for it. Boy, was Carl Buettner mad! He was the editor. They paid me for the pages, but we had to completely re-write the story. So I learned. Even with a daily strip, I always made sure of the end; I did the last panel first, Napoleon or Ella. I always knew where I was going. I did the gag in the last panel, and then I'd lead up to it."

"SO HOW DO YOU COME UP WITH GAGS for a gag strip?" I asked, having found at last an opening into which I could lob cartooning's perennial unanswerable question.

"Well, I'm not the world's greatest gag man," Armstrong confessed. "Now, Clifford, in his early days, was: he was a magnificent gag man. Some of the funniest damn stuff you ever saw. But eventually, you get to the point where the creative edge is blunted a little from meeting constant deadlines. He used to get frantic for gags. I did, too. There's just so much you can do with a fat man and a big dog. That's why he introduced other incidental characters— the nephew Willie, the neighbor woman.

“Margot and I devised Indian Joe, the guide on camping trips. And I did a couple of things to find gags. I subscribed to Punch, and I would go back ten years and do switches— take a gag and turn it around somehow. And I bought gags. Clifford didn't, but I did. I put some of my funny friends to work."

"Do you ever just doodle with pencil on paper in order to think of a gag?" I asked.

"Oh, sure— you can sometimes come up with gags by just drawing your characters in various situations, letting the gags grow out of that."

I told Armstrong that to the best of my knowledge, his book is the only one I know on comic strip drawing that begins where every comic strip cartoonist must begin— with speech balloons, where they should be positioned and the like. "In most how-to books I remember," I said, "speech balloons are treated as a perfunctory matter, and yet they're the absolute beginning."

"It's the heart of the thing," Armstrong agreed.

"And they must appear in the right order," I said.

"Right," he laughed. "The book is written out of the experience of my cartooning classes. I can't tell you how often I've had to tell students that English is read from left to right. You don't put the opening balloon in the first panel at the right and then put the response to the left. It just doesn't read that way. But it happens over and over and over."

When I asked about his philosophy of teaching, Armstrong said he often used principles that are found in Betty Edwards' Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, which, he said, is a psychological synthesis of Nicolaides' The Natural Way to Draw.

"But I guess I teach intuitively most of the time," he said. "I lecture, then I demonstrate, then I go around the room and work with each individual. A lot of instructors are reluctant to demonstrate. They don't seem to have the facility to sit down and knock out a drawing quickly that will show what the student should see.

“I've been told by many students that watching me do what I do is one of the major ways they learn. I believe in starting with the basics. When I teach watercolor, I have people puddling color. And the I give them a color lecture, and then I give them exercises in how to manipulate the color, and the I give them exercises in how to lay a wash. They can't paint a picture until they've done at least ten weeks of exercises.

"Philosophically," he continued, "I feel that in order to achieve a creative result, you must have the tools. If I wanted to play the piano, I could not sit down and play a Chopin waltz until I had learned that keyboard and knew it by heart and had done my five-finger exercises over and over. It's the same damn thing with painting or drawing.

“And I'm a strong believer in having my students achieve successes; I don't want them frustrated. So I try never to give a student more than I know he or she can handle. If they can handle it, then I move them on to the next thing, but I don't let people move forward until I know that they can do what I know they're going to need for the next step. Take your time and learn the basis, that's my philosophy of teaching."

Armstrong got into the teaching game by way of an art museum. He was involved with Napoleon and Ella Cinders until they ceased (1960 and 1961 respectively). Then he did The Flintstones comic strip for a year or so, and he was story director for the Hanna-Barbera prime-time television show, "Wait Til Your Father Gets Home."

And then in about 1963, his wife talked him into entering an art show sponsored by the Laguna Beach Art Association. He won second prize for a watercolor and soon found himself on the Association's board of directors; a couple months later, he was director of the Association's museum (now the Laguna Beach Museum of Art), a position he held for four years. During that time, he also drew the Little Lulu comic strip, an incongruous coupling of occupations that still gives Armstrong a chuckle.

"Every day, I'd get into my museum director's costume," he recalls, "—a nice suit, gray silk, and a vest and a necktie (my wife made me buy a couple of these get-ups)— and I'd go off to work on my ten-speed bicycle, carrying my little attache case. And I'd go in and sit at my desk and give directives to my secretary and arrange shows and so on. And at the end of the day, I'd come home, get into my blue jeans and my sweatshirt and I'd sit down and draw Little Lulu." He laughed.

After leaving the directorship, Armstrong taught at the Laguna Beach Art School (cartooning, basic drawing, oil painting, figure drawing, watercolor— everything, he said, but design). Then in about 1977, cartoonist Ed Nofziger told him he'd recommended him to the Disney people to draw Scamp, their comic strip about a mischievous pup. Nofziger had told them Armstrong was the best dog artist in the world.

"So

I went up there," Armstrong said, "and I showed my portfolio and

drawings to Don McLaughlin, who was head of the department at the time, and

they gave me a script to take home and work up. And just before I left,

McLaughlin said, Oh— wait a minute: can you draw Mickey Mouse? And

I said, Oh, God, I can't draw Mickey Mouse to save my life. And he said,

Good— you're hired."

He did Scamp for about ten years, gags supplied by the Disney Studios (Tom Yakutis did the best of them, Armstrong remembered). And he enjoyed his association with Disney: "I had the great good fortune to have the finest guys for editors. Tom Goldberg was absolutely wonderful." In addition to Scamp, Armstrong illustrated five books for the Disney Library.

He

hasn't drawn a strip regularly since 1988, but he's worked up a strip about

lawyers called Ben Barrister with writer Joe Jares.

strip about

lawyers called Ben Barrister with writer Joe Jares.

"I think it's a good idea for a strip," Armstrong said. "I think it has a place in the comic strip world. I wouldn't want to do all the drawing, though," he went on. "I'd like to do the pencilling and then had it over to one of my students to ink. I don't feel like sitting in solitary at my drawingboard these days. I could do that when I was a kid. But I'm too gregarious. I never knew that until I started teaching. And I find that this is really my forte— getting out there and communicating with people."

*****

THIS WAS THE FIRST ARTICLE I’d ever written from an interview. Starting with Roger’s, I would do several more interview articles, a half-dozen a year, for Jud’s Cartoonist PROfiles. If Roger hadn’t come along with his proposal, I would never have found my way into Cartoonist PROfiles not to mention several other outlets.

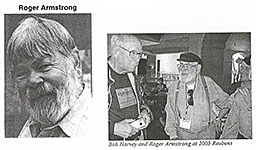

For the next seventeen years, Roger and I exchanged letters and random pieces of artwork. We met “in person” sometime along the way—at least by the time of the 2005 National Cartoonists Society’s Reubens weekend because someone took a photo of us together at that event. That was the year that Roger found himself the captive of a strange but entrancing compulsion.

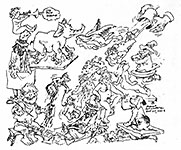

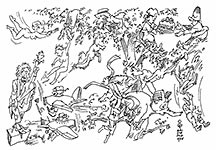

It started, he always claimed, with a bottle of walnut ink given to him by one of his students, Ruth Hunter.

“She inadvertently opened up a window of creativity for me that I haven’t experienced for years,” Armstrong said, continuing: “That link coupled with a batch of drawing pen points that I inherited from the late Karl Hubenthal, were the doorway to a series of stream-of-consciousness drawings that have become a passion with me ever since I dipped the pen into the walnut ink.”

He makes the drawings on large, 22x30-inch sheets of watercolor paper. The pictures fill the page.

“I start each giant drawing with a small image somewhere on the page,” he explained, “and let the conformation of that drawing lead me, with no conscious thought, to the next image, usually totally un-related to the first image, and so on, growing, growing until the entire page is filled with unrelated ‘doodles.’ Yes! That is what they are—doodles!

|

|

“Like New York or London,” he went on, “the total drawing is composed of many small neighborhoods, each complete unto itself, but the total is a gestalt in which the whole is greater than the sum of all of its parts.”

Roger dashed off notes to me, each noted accompanied by one or more of the pictures, reduced to 8x10 inches for the purpose.

“What in God’s name will I do with them?” he exclaimed. “They’ve become an obsession!”

He continued doing drawings in this antic mode for months, periodically sending me batches of them, recording the ever-increasing inventory each time—“32,” “over 60,” “more than 150 of these things.”

Roger was a fine painter, but the inner cartoonist lurked with a vengeance that had, at last, burst forth in a flurry of freehand hilarities—no penciling, just pen and walnut ink. At last count, he said he’d done more than 200 of them and felt no inclination to stop. Roger Armstrong’s last testament. Here are a few more of them.

|

|

|

|

|

WE MET AT VARIOUS TIMES AND PLACES over the years. Once I wandered off a beaten path to visit him at his trailer studio on the beach at Crystal Cove. (Well, it may not have been Crystal Cove; it may have been Dana Point, which was the return address on the envelope of McBride Napoleon strip panels; it’s all California to me.) Inside it was mildly messy. No surprise. Creative people are always on the lookout for the next inspiration, and when they have one, they dash off in hot pursuit, willy nilly, having little time for or interest in making anything in their surroundings tidy.

Another time, I took a detour to visit Roger and his wife, Alice Powell, also an artist, at their home in Laguna Hills. It was, I suspect, Alice’s house into which Roger married when he married Alice.

Roger subsequently opened a new studio just two miles from his home and shut down the trailer.

For several years, Roger published a newsletter that he sent out to his students and potential students. The purpose of the newsletter was to tell interested parties when he would be conducting painting classes for the next month. He taught classes of ten students each in the studio. On Saturdays, he conducted plein air classes at various picturesque Orange County locations, listed in advance in the newsletter; tuition $20. On Fridays, he taught his class at the Art Institute of Southern California at Laguna Beach.

And

what was Roger like? He was one of those individuals whose personality is

perfectly reflected in his face. Bearded, a lightly grizzled visage surmounted

by twinkling eyes, in person Roger was humorous and also opinionated, but not

offensively so. He was good company, a pleasure to be around and to exchange

letters with.

Roger died on June 7, 2007. Dennis McLellan, staff writer at the Los Angeles

Times, wrote an obituary that handily summarizes Roger’s life and achievements. Here it is—:

Roger Armstrong, whose five-decade career as a cartoonist included doing artwork for Bugs Bunny, The Flintstones and numerous other comic books as well as for comic strips featuring characters such as Little Lulu and Scamp, has died. He was 89.

Armstrong, a longtime art teacher and a noted Southern California oil and watercolor painter, died of cardiac arrest June 7 at Mission Hospital in Mission Viejo, said his wife, artist Alice Powell.

As a cartoonist for Western Publishing in Los Angeles in the 1940s, Armstrong worked on Bugs Bunny and other Warner Bros. characters— including Porky Pig and Elmer Fudd—as well as Walt Disney characters such as Little Hiawatha, the Seven Dwarfs, Donald Duck and Pluto, and Walter Lantz’s Woody Woodpecker.

Armstrong also was one of those who drew the Bugs Bunny newspaper cartoon strip from 1942 to 1944, the year he was drafted into the Army.

Armstrong, who had been cartoonist Clifford McBride’s assistant on the comic strip Napoleon and Uncle Elby, took over the strip when McBride died in 1950 and continued doing it for a decade. He also drew the cartoon strip Ella Cinders in the 1950s and later returned to working on the Bugs Bunny strip, in addition to working on the strips Little Lulu, The Flintstones and Scamp.

At Western Publishing in the 1960s and 1970s, Armstrong did comic book artwork for the Flintstones, Scooby Doo, the Pink Panther, the Inspector, Super Goof and the Beagle Boys, among others.

“He was a pioneer of doing funny animal comic books, taking an animated property from the screen and adapting it to the comic book page,” said Mark Evanier, a TV writer who wrote The Flintstones and Super Goof comic books when Armstrong was drawing them in the 1970s.

Western Publishing, Evanier said, “put Roger in everything. He was in those books for decades doing this wonderful work and kind of setting the bar for the other artists who drew for those comics.”

Cartoonist Greg Evans, who does the Luann comic strip, said Armstrong “was just one of those incredibly gifted cartoonists who could effortlessly draw anything in any style.”

Evans, a friend of Armstrong, likened the white-bearded artist to Santa Claus, complete with twinkly eyes. “Roger had this kindly, impish, gentle, fun and funny nature,” he said.

As a painter, Armstrong was primarily known for his watercolors.

His

paintings are in more than 300 private collections and in a number of public

collections, including the Museum of Cartoon Art in New York, the Smithsonian

Institution and the Laguna Art Museum.

“His art is really the art of everyday life in Southern California,” said Jean Stern, executive director of the Irvine Museum, which specializes in the art of California in the early 20th century and has two of Armstrong’s paintings in its collection.

“He painted a large series of paintings when he lived in Los Angeles and later on when he lived in Crystal Cove and Laguna Beach,” Stern said. “He’s one of those artists we really like because they paint their everyday life and the things and people around them. Essentially, where he lived became the subject matter.”

Armstrong, a former president of the National Watercolor Society, served as director of the Laguna Art Museum from 1963 to 1967.

Over the last four decades, he taught painting and drawing classes at a number of schools, including Orange Coast College in Costa Mesa, the Irvine Fine Arts Center and what is now the Laguna College of Art and Design (formerly the Laguna Beach School of Art and the Art Institute of Southern California).

Born in Los Angeles on October 12, 1917— his father, Roger Dale Armstrong, was a silent film writer and director— Armstrong knew by age 10 that he wanted to be a cartoonist.

At 16, he was earning $1 for drawing six ads per week for a local advertising agency. After graduating from high school, he attended Chouinard Art Institute on a scholarship from 1938 to 1939 but was forced by the Depression to quit and find a job.

He was working on an assembly line at Lockheed Aircraft in 1941 when he was hired at Western Publishing to draw Bugs Bunny for a new Warner Bros comic book, Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies.

Armstrong, who also had a stint working as an assistant animator at the Walter Lantz Studio in the 1940s, was the author of How to Draw Comic Strips, a 1990 book published by Walter Foster Publishing Inc.

ROGER ALWAYS included other scraps of information in his newsletter. In his April 1999 issue, he quoted a poem about death that his father, R. Dale Armstrong had written just two years before his passing in 1932. Here it is—:

Death Holds No Fear

It seemeth such a little way to me

Across to that strange country, the Beyond,

And yet, not strange, for it has grown to be

The home of those of whom I am so fond,

They seem to make familiar and most dear,

As journeying friends bring distant regions near.

So close it lies that when my sight is clear

I think I almost see the gleaming strand,

I know I feel those who have gone from here

Come near enough sometimes to touch my hand.

I often think but for our veiled eyes

We should find heaven round about us lies.

I cannot seem to make it a day to dread

When from the dear earth I shall journey out

To that still dearer country of the dead,

And join the “lost ones,” so long dreamed of.

I love this world, yet shall I love to go

And meet the friends who wait for me, I know.

I never stand above a bier and see

The seal of death sat on some loved face

But that I think: “One more to welcome me

When I shall close the intervening space

Between this land and that one over there—

One more to make the strange beyond more fair.”

And so for me there is no sting to death,

And so the grave has lost its victory.

It is but crossing, with a bated breath,

And white set face, a little strip of sea

To find the loved ones waiting on the shore,

More beautiful, more precious, than before.

Thanks, Roger.