THE REAL CAPTAIN EASY

And Where Roy Crane Found Him

Roy Crane’s Captain Easy, the rugged and savvy soldier of fortune who invaded Wash Tubbs on May 6, 1929 and never went away (for which we are all hysterically grateful), inspired a generation of cartoonists who patterned adventure story heroes in the comics after Crane’s creation. As I’ve said elsewhere in these parts (see Harv’s Hindsight for July 2002), it is almost impossible to overestimate the impact of this character on those who wrote and drew adventure stories in comic strips and comic books in the thirties. Murphy Anderson and Gil Kane (among others, surely) saw Easy reflected in many of the first comic book heroes. Kane, who began his comic book career in the early forties, once chanted a litany of credit to Crane before an audience at the San Diego Comic Convention: “Superman was Captain Easy,” he said; “Batman was Easy.” Caught up in the rhythm, he listed several more characters before he stopped.

Kane may have overstated the case in order to make his point. But anyone familiar with the first works of Superman’s creators, Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel, will recognize Easy in Slam Bradley, a character the two invented a year or so before Superman saw print. Bradley even had a diminutive side-kick like Wash Tubbs. And Superman/Clark Kent looks a lot like Slam Bradley. While the facial resemblance may be due more to Shuster’s limitations as an artist than to Crane’s influence, it is nonetheless clear that Captain Easy was in the minds of virtually everyone who was doing adventure stories in comics in the thirties. For the medium’s adventure genre, whether in strips or books, Easy was an archetype.

And Easy was patterned after a real person.

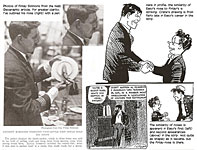

In the fall of 2005, I received an e-pistle from Dr. Victoria Simmons, who said she was the granddaughter of the man whose manner and physiognomy inspired Easy—George Finlay Simmons, who was Crane’s brother-in-law. Swept up in other minor matters for the nonce, I failed to follow up with Dr. Simons until September 2010, a shameful lapse of time, I realize. But she is marvelously patient, not to mention articulate, witty and exacting, and she sent me a biography of her grandfather and numerous candidates for illustration, all of which I post below. She was a distinct pleasure to work with, and now you can meet her, too, as she rehearses her grandfather’s story in the course of the essay that commences forthwith.

*****

DURING THE SECOND OF HIS TWO MATRICULATIONS at the University of Texas in Austin, Roy Crane met a dashing graduate student in zoology named George Finlay Simmons.

|

|

Finlay, as he was called, was six years Crane’s senior and was editor of The Longhorn, the campus magazine, to which, presumably, Crane offered cartoons and illustrations while on campus for the school year 1921-22. The two evidently hit if off: Finlay was seriously dating Armede Hatcher and probably introduced Crane to her sister, Evelyn. Finlay married Armede, called Jack (because her father wanted a boy), in the spring of 1922 just as he received his master’s degree; it would be a while before Crane could follow his example and marry the other sister on February 8, 1927.

The Hatcher sisters, according to Finlay and Jack’s granddaughter, Victoria Simmons, were the daughters of “a splendid, adventurous, and independent woman,” Virginia Mae Therrell, who, after having three children with Harry Hatcher, discovered he was a womanizer and divorced him, “raising their three daughters on her own, and working variously, over the years, as a stenographer, secretary on a ranch, and (later) as a fraternity house mother. In later years, inheriting money from a friend, she spent her time traveling.” She was, Victoria said, “an important figure in the lives of her daughters, sons-in-law, and grandchildren, and always a welcome visitor. It is perhaps because of her influence that all three daughters married men who could be considered, in their own ways, adventurers. (Ceil, the third daughter, married an engineer, Homer ‘Hoke’ Stevenson, who had worked in South America.)”

Finlay came from a family of lawyers—grandfather, father, and younger brother all went to the bar—but despite paternal pressure, he pursued a career as a naturalist, which led to a good deal more adventure than law books. He grew up in Houston and, said Victoria, “in his teens he was already publishing articles on birds, but his father advised him to keep bird-watching only as a hobby. Trying to pursue both [legal and ornithological] paths simultaneously (and wasting a lot of time at soda fountains and movie theaters and spooning with girls on front porches), he did succeed in becoming a protégé of naturalist Julian Huxley, who was at Rice University at the time. During this period he also worked as a stenographer (for a law firm), a law clerk, and a writer for the Houston Chronicle and the Houston Post. World War I intervened, putting an end to both his law studies and his work with Huxley.”

During the war, Finlay served in the medical corps. “He stayed stateside during the war, and wound up running a base hospital in Mississippi, advancing to the rank of sergeant and ultimately non-com second lieutenant. In this position he was ringside at the great influenza epidemic of the late 1910s, but seems rather blase about that in his letters.”

Just after the war and before entering the University of Texas in 1919, Finlay “worked for a while as a police secretary, getting free admission to movies and many restaurants as routine police graft, and also going along on raids for fun.

“While at Texas,” Victoria’s account continues, “Finlay worked various extra jobs, including summers in the oil fields of Orange, Texas, and after he got his MA he got a job with the Texas Game, Fish, and Oyster Commission, where he seemed to spend at least part of his time chasing poachers in a cruiser and where he caught the malaria that occasionally plagued him for the rest of his life, and which was perhaps the cause of the Parkinson's Disease that killed him” [in 1955].

But Finlay’s big adventure came “when he was recruited by the Cleveland Museum of Natural History to lead a collecting expedition in the South Atlantic, funded by the museum's chief patroness, Peg Blossom, who was the wife of a Cleveland oil baron. Through inexperience (Finlay's and the museum people's), the choices made in outfitting the expedition were bad choices, including buying an old sealing ship, a three-masted schooner with no engine, and hiring a mostly college-boy crew. (These were later replaced, in some cases with former whalers and sealers.) These choices led to the voyage of the Blossom being much longer and problem-ridden than foreseen, taking two years (1923-1926, including prep time) and including periods where they were stranded for repairs in port in West Africa or becalmed in the Sargasso Sea. However, the expedition (which included a taxidermist in the crew) brought back thousands of specimens, as well as photographs and film footage.”

Although Finlay had been hired as the Museum’s assistant curator of ornithology, “a position he was supposed to take up at the museum after his return, it was decided instead that he would leave the Museum to do the lecture tour about the expedition, and then finish his doctorate, funded by Peg Blossom. The lecture tour was typical of the traveler-explorer tours of the period, and—on the lecture circuit and as a member of the Explorers Club—Finlay became friendly with people like Lowell Thomas and (according to my father, Finlay’s son) may have had an affair with Margaret Bourke White.

Afterwards he settled in to do the Ph.D. It was just after finishing his doctorate that he was hired as professor of zoology at Montana State University (later University of Montana), and—two years after his arrival in Missoula—as president of the university, a position he held from 1936 to 1941”(despite an inauspicious beginning as referee in a noisy censorship case).

Finlay may have written the copy for the brochure about the lecture tour, dubbed “Sinbads of Science.” If he did, he’d caught the fever of high adventure: the breathless text rings with the hyperbole of comic strip excitement:

|

|

“Like the Eighth Voyage of Sinbad the Sailor is this Odyssey of Ornithology. ... The three-masted schooner Blossom, 103 tons, 109 feet overall—smaller than Columbus’ Santa Maria—has just returned from one of the strangest voyages in the annals of modern exploration. ... Captain Geo. Finlay Simmons, commander of the Blossom, and fifteen men—as advance scouts of the army of science—visited strange ports and outposts of the sea.”

In his report on the voyage in National Geographic (July 1927), Finlay is somewhat less florid but still flamboyant:

“A tiny, black-hulled schooner ... sixteen hands, all told, perhaps sixteen men for some dead man’s chest of a treasure islet. ... We met storms, head winds, and disheartening calms; men were sick from fevers and exposure, usually when they were most needed; our small boats were battered on hidden reefs and iron-bound shores, and one whaleboat was wrecked in making a difficult landing. In distant ports, of Africa and South America, there were wearisome delays while the schooner underwent the repairs always needed after many months at sea.

"Fortunately, the tragic drama at times became melodrama and even light opera—a background of native huts with too much covering and native maidens with too little; guitars softly strumming the plaintive minors of a primitive people; the hypnotic beat of a Senegambian tom-tom, summoning ebony damsels to quiver in the throes of a voodoo dance; shabby beach-combers and thirsty mariners; soldiers-of-fortune and the multi-hued warriors of colorful nations; and girls to lure the sailors from their duty—girls ranging in complexion from the sun at high noon, through the café-au-lait of Brazil and the Cape Verdes, to the blackest blue-black of Africa.”

Invoking threatening waterspouts and gales and contrary currents, the lurid text of the brochure prolongs the torrid tale: The Blossom stopped at St. Helena, and “Captain Simmons dined in Napoleon’s quarters and found a giant tortoise that might have seen the exiled emperor. ... They landed at Shipwreck Reef. They visited Pandora’s lovely Fernando Noronha, with its towering palms and waving breadfruit trees—that isle of crooked men where Captain Simmons was fed by a poisoner, shaved by a cutthroat, and surrounded at night when asleep by prowling midnight assassins. Here they fought the Vampire of the Seas, captured Davy Jones’ wolf, and found the queer two-headed snake. ... Adventure enough for a lifetime.”

While all of this rattling good time lay before Finlay in 1921-22 when Crane met him, Finlay doubtless had about him the aura of the globe-trotting naturalist that he would become. About the same time that Finlay left the University with his degree, Crane left without one. Victoria explained: “According to Finlay (via my father) it was sort of a joke at the University of Texas that Roy Crane pledged Sigma Chi (Finlay's fraternity) repeatedly, but his grades were never good enough. The fraternity finally told him that he could be a Sigma Chi if he would stop embarrassing them, and go ahead and quit school. He cared more about being a fraternity man than being a college graduate, so he did. That's the story, anyway!”

But Crane kept in touch with Finlay, particularly after they became brothers-in-law: their wives, as sisters, fostered the bond between their husbands.

WHEN DOING AN ORAL HISTORY with her father, Victoria asked him to describe Finlay in one word, and he said, “Playful.” She continued: “My father described both his parents [Finlay and Jack] as being, not only intelligent and well-read, but at ease everywhere they went, and able to make friends with people at all levels of society. According to Dad, Finlay was the sort of person who—while his wife was trying to talk to the waiter in perfect, painstaking French—would in his own bumbling French learn the guy's whole life story. Despite the pulpy writing style he employs in the National Geographic and in the brochure (blackest Africa, dusky maidens, throbbing drums, etc.), he seems not to have shared the segregationist prejudices of his era. He lived in close quarters on the Blossom with the Jamaican cook and the black Portuguese first mate Long John da Lomba, and remained friends with the latter for years afterwards. These qualities of fitting in everywhere (despite an oversize personality) and taking people as he found them may have contributed to Roy's portrayal of him as Easy.”

Finlay died before Victoria was born, but she saw many photographs of him. “When I look at Easy,” she wrote, “I see Finlay, and also my father since Finlay shared a strong resemblance with his two sons, which is also the resemblance of all of them to Easy: tall, lanky, broad-shouldered, dark-haired, clamp mouth with smile lines, narrow eyes set close beside a beaky nose, and a distinctive hatched-shaped face. The only change Roy made was to strengthen Finlay’s somewhat receding chin: Roy gave Easy a more heroic chin than genetics gave the Simmons men.

|

|

“Finlay,” she continued, “was a soft-spoken and well-read man and a Southern gentleman of the old school, but he was also (by all accounts) a strong-willed and straightforward person, happiest when fishing or bumming around and with an unexpected streak of playfulness. When my grandmother, during their courting period, very seriously asked for a list of books he had read so that they could compare intellectual influences, he responded with a list of children’s classics such as Mother Goose, Alice in Wonderland, Journey to the Center of the Earth and such boys’ series as Rover Boys and Diamond Dick.”

About the moment of inspiration resulting in the invention of Easy, Victoria cites comics historian Ron Goulart’s article in Starlog Comics Scene no. 6 (1982). In a sequence in the fall of 1928, Wash and Goozy are twice saved by a black harem slave named Bola. “Crane’s brother-in-law kidded him about this particular sequence,” Goulart noted. “‘He told me you shouldn’t have a eunuch save them,’ Crane recalled. ‘What you need is a two-fisted guy.’ Crane had been thinking about the character of Wash Tubbs for quite a while. He felt Wash was an underdog, somewhat like Jim Hawkins in Treasure Island, who ‘obviously had a hell of a time taking care of himself.’ He had these things in mind when Finlay made his criticism. A few months later, Crane introduced Easy to the strip. And ‘since this brother-in-law of mine had suggested it, I used him as a model.’”

In

1974, Crane sent Victoria’s father (Finlay’s son), Robert, a copy of Roy

Crane’s Wash Tubbs: The First Adventure Strip compiled by Gordon Campbell

and Jim Ivey. On the inside cover, he drew Wash and Easy in color and wrote:

“Dear Bob: When it took harem eunuchs to get Wash out of a jam, your dad kidded

me into giving Wash a two-fisted sidekick. To kid him back, I used Finlay as a

model for Easy.”

Given that testimony, it may be superfluous to notice the tell-tale confluence of some dates. Crane’s ties to Finlay were made secure and on-going by his marriage to Finlay’s wife’s sister in 1927, within a year of Finlay’s return from his voyage to exotic climes on the Blossom and perhaps just as the scientific Sinbad finished recording his adventures for the National Geographic. The lecture tour probably took place in 1928 (the date of the brochure’s copyright). In any event, Finlay’s specimen-buckling adventure was undoubtedly still the stuff of current family lore when, in the fall of 1928 or early 1929, Crane conjured up a two-fisted adventurer in the image of his brother-in-law; and, as noted in our introduction, Easy arrived in Wash Tubbs in May 1929.

Victoria never met Crane, but she remembered her father’s affection for the cartoonist. Her father “in his youth visited the Cranes, and my parents moved to Orlando [where the Cranes lived] after they were married and were sponsored by Eb [as Evelyn was known] into society. After they moved away, I’m not sure they ever saw the Cranes again, so all my father’s stories were based on his impressions them from boyhood to his early thirties, and after that, on occasional phone calls. ... He had many stories about Roy, but the thing I remember best is that he said Roy's drawing table was by a big window whose view was flanked by trees outside the house. On one of Dad's visits, an enormous black-and-yellow spider had built a web across the gap, right in front of the window, and Roy wouldn't let it be killed. He liked to work while watching the spider work.”

She concluded: “I definitely had the impression from my father that Roy hero-worshiped his big, rugged brother-in-law at least a bit, but then I know that Dad hero-worshiped them both.”

And so, as we’ve seen, did a generation of adventure strip cartoonists who didn’t know that the Easy they venerated was the paper-and-ink incarnation of a real personage.

Now, here is some more pictorial evidence of the adventures Finlay had on the Blossom: the rest of the lecture tour brochure, plus a photograph of the voyaging vehicle itself.

|

|

|

|

|