IT'S NOT MY FAULT

Apologia pro Vita Sue

Or—The Confessions of a Comics Junkie

IT’S NOT MY FAULT. It’s John Lent’s. He is entirely to blame for the ensuing effusion. Long about the fall of 2004, during the triennial Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum’s Festival of Comic Art at Ohio State University, John Lent, editor and publisher of the International Journal of Comic Art, asked me to write about how I got into the comics history game for a series he was running, “Pioneers of Comic Art Scholarship.” So, ever eager to oblige, I did. He published the result in the Fall/Winter 2005 issue of the Journal (Vol. 7, No. 2). And now I’m re-publishing it here as the oddest way I can think of to celebrate the 300th posting of my online magazine, Rants & Raves—herewith, an autobiography of critical theory, another effort in my own series to erect a stunningly self-indulgent monument to my very own vainglorious self. With self-aggrandizing preambles like this, my strategy is to cut myself down to size. But as you will soon learn, I haven’t been roaringly successful.

IT IS ALL MY WIFE'S FAULT. She'll deny it, of course, but that is her business and need not concern us here. Here, my best recollection is that it was entirely her fault that I got mixed up in this comics and cartooning history and lore racket—which only proves that behind every grating mein there is a compassionate woman willing to take the blame.

We had been married but a mere year-and-a-half and were living in squalid comfort in what had been my bachelor apartment, the entire first floor of a two-story house just two blocks west of the railroad tracks in Champaign, Illinois. ("West of the railroad tracks in Champaign, Illinois," is virtually all of Champaign, Illinois: the town grew up around the depot, which had been built a couple miles west of the city it served, Urbana, in order to keep the traveling riff-raff safely away from the local populace. History, it should be noted, chastened Urbana for its snootiness: Champaign eventually grew larger than Urbana and got all the best stores.)

One evening, I was, as was my wont, folded into the heirloom armchair in the livingroom (an armchair I'd inherited from my father), and Linda was in the kitchen as was her wont, washing the dinner dishes. I was perusing an issue of a magazine called Media & Methods (M&M), a periodical directed at high school teachers who wished to confront modern America in its own terms by turning popular culture and mass media into curricula. I was reading an article about the presumed virtues of teaching comics in the classroom. It seemed to me a particularly inept piece of work, written by someone who had virtually no idea of the history or content of newspaper comic strips.

"What flummery," I snorted in contempt. "Why, I can do better than this!"

"Why don't you then?" Linda said, having heard my outburst over the clatter of dish-washing.

Little could she have known, at the time, that with this innocent mostly conversational (that is, nearly rhetorical) question, she would provoke her husband into a lifetime of writing and researching comics and cartooning history. Over the ensuing forty-plus years, I plunged deeper and deeper into the maelstrom of the medium, spending more time with comics than with my children. My preoccupation did not destroy our marriage, thankfully, but it surely changed it. And once I retired from my regular line of work (I was a king) and our children had fled the premises to start lives of their very own, I devoted a large portion of every day to reading and writing about comics and cartoonists. I still do.

Almost no prodding, beyond the asking of that initial provocative question, was needed to keep me going. I loved cartooning and had once planned to make it my career. That wasn't my fault either.

*****

MY FATHER WAS AN ARTIST although he never made a living at it. He had spent much of his youth riding his bicycle to the villages near his hometown of Bedford in England and sketching picturesque churches and inns in pencil and in pen and ink. I evidently inherited some of his talent: in first grade, I'd won a prize for a drawing of a WAC in full World War II uniform. (The U.S. involvement in World War II was then in its second year.) But it was my father's skill that enthralled me. He began amusing me by drawing pictures of my favorite cartoon characters—Bugs Bunny and Donald Duck and Goofy and, later, Disney's version of Pinocchio—all precisely copied in ink and beautifully colored and then framed under glass to adorn the wall of my bedroom. One evening after reading a comic book, I asked him if he'd copy one of the characters for me—Super Rabbit, I think it was. But he was otherwise occupied and, in an almost off-hand way, said, "Why don't you draw it yourself?"

So I did. A very amateurish copy, but a copy nonetheless. With that, the bug bit me. I started copying everything I found in the comic books I owned. (Among them, a character so obscure that I've never found anyone who has ever heard of him. His name, I believe, was B-1 or some such: he was named after a vitamin, which, when he took one, turned him into a superhero. Not a realistic superhero though—more of a comical one. He wore a small bottle of these magic pills around his neck on a cord.) I was seven at the time, and I began telling people I would be an artist when I grew up. Later, I learned that the kind of "artist" I aspired to being was called a "cartoonist."

I copied cartoon characters all through grade school; by the time I was in high school, all the graphic idiosyncracies of the cartoonists I'd been copying had been rearranged and congealed into a "style" distinctly my own, no longer reflecting any discernible evidence of its numerous places of origin. I took it to college at the University of Colorado, where I continued to belabor blank sheets of drawing paper with pen and ink. It was during those years that I started, almost by accident, signing my cartoons with a tiny picture of a bespectacled rabbit—a pictorial version of Jimmy Stewart's invisible "Harvey" substituting for the inscription of my actual name. I call the rabbit Cahoots, but that’s not his name: his name, of course, is Harvey. I started hiding the harried hare in the drawings, and someone flattered me by saying that looking for my rabbit in a drawing was like waiting for Hitchcock to show up in one of his movies.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

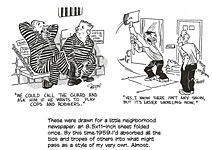

After college, I stormed the magazine citadels in New York from a garden apartment on West 82nd Street, where I'd spend 4-5 days a week conjuring up cartoon ideas and then rendering them with a juicy brush on sheets of Strathmore bristol board. Once a week—on Wednesdays, the traditional "look day" during which cartoon editors at magazines headquartered in the city received submissions in person—I made the rounds of the magazines, beginning with the highest paying ones and ending, after a long and fruitless day, at the offices of Humorama, an offshoot of Martin Goodman's publishing empire that specialized in digest-sized booklets of slightly risque cartoons and jokes and cheesey-cake photos of starlets. Humorama paid digest-sized amounts, $9, but it was better than throwing the cartoons into the trash barrel on the corner.

In none of these cartoons—nor in any I produced during my later mail-order career as a gag cartoonist—did I use my rabbit signature. I figured editors would think I was pandering to Playboy and would therefore not buy anything. (Although if I’d thought signing with a rabbit would have sold cartoons, I’d have pandered all day long.)

Regrettably,

I never made the acquaintance of any of the other cartoonists making the rounds

on "look day": I'm sure some of those people sitting around the

reception rooms were cartoonists, but I was too shy to approach them. I finally

sold a cartoon to DuGent (my best sale, $25) and a couple to Humorama.  Then, feeling the

hot breath of the military draft on my neck, I returned to Colorado, where I

freelanced advertising cartoons for a couple months, then went on to Kansas

City, enlisted in the Navy, and waited at my parents' house to be called up six

months later.

Then, feeling the

hot breath of the military draft on my neck, I returned to Colorado, where I

freelanced advertising cartoons for a couple months, then went on to Kansas

City, enlisted in the Navy, and waited at my parents' house to be called up six

months later.

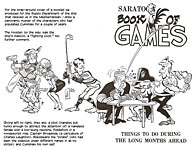

In the Navy, I drew cartoons for every publication in whatever vicinity I found myself—the "cruise book" (yearbook) at Officers Candidate School (OCS) in Newport, Rhode Island; the newspaper at Supply Corps School in Athens, Georgia; and the ship's monthly magazine aboard the USS Saratoga (CVA-60). Taking at least a full page ever issue, the Saratoga strip starred the eponymous Cumshaw, a con man and operator who virtually took command of his ship. "To cumshaw" in nautical argot means "to obtain by irregular means"; whatever is obtained by such means is usually referred to as "cumshaw."

And all the while, I envisioned the comic strip I'd do after I got out—a mock-heroic comedy-adventure opus named Fiddlefoot..

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

When I escaped the Navy (having decided that it was, at best, only a fleeting thing), I prepared a couple of "presentation books" for submitting strips to syndicates, but, alas, syndicates were no longer interested in humorous continuities, television having displaced comics as the venue for storytelling. Newspaper funnies by this time (1964) were firmly committed to gag-a-day strips, and I wasn't any good at making up jokes. (For the whole sordid tale of how I invented and failed to sell Fiddlefoot, see Harv’s Hindsight for July 2012, profusely illustrated.) So I went into teaching for a few years and wound up, finally, working for the National Council of Teachers of English, headquartered in Champaign, Illinois, right back where we started a few paragraphs ago.

*****

AS I PONDERED my wife's nearly inadvertent urging, I fancied that with my experience actually drawing cartoons, I could bring to the critical appreciation of the medium some insight that the writer of the scorned Media & Methods article clearly lacked. I believed that I knew better than he how comics worked; and I knew I had read more of their history than he had. At that time, there were only two histories of comics around—Coulton Waugh's The Comics (1947) and Stephen Becker's Comic Art in America (1959)—and I'd read and devoured them both, virtually committing them to memory.

The writer of the article I was so arrogantly belittling had bemoaned the baffling variety of art styles and story treatments and seeming purposes on the funnies pages of the nation's newspapers, claiming that this bewildering assortment made any kind of reasonable critical assessment nearly impossible. In the article I wrote in response, I countered by saying that the history of the medium provided a place to begin. Tracing that history, I showed how the comic strip had gone from joke-a-day comedy to soap-opera continuity and then to adventure stories, each requiring a different illustrative manner.

"On today's comic pages," I wrote, "we can find much of the history of the medium—in individual strips of various kinds, each of which reproduces—as an inheritance, as a 'tradition'—various high points in the art form's history. The first to reach those pinnacles of achievement are the models in whose image today's strips are fashioned. With the history of comic strips at his elbow, one can construct 'family trees,' tracing the lineage of a particular tradition back to its origins. The soap opera in Apartment 3-G is in the tradition of Mary Worth and Little Orphan Annie; these strips, in turn, derive something from The Gumps and something from Desperate Desmond. And, at the same time, the artwork in Apartment 3-G continues the standards set by Foster and Raymond. Steve Roper and similar 'crime fighting' strips continue the tradition begun by Chester Gould in Dick Tracy, and Tracy goes back through Wash Tubbs to Desperate Desmond. In artistic treatment, Roper belongs, with some qualifications, in the Caniff school of impressionistic rendering. A judgment of excellence is as much a measure of the author-artist's ability to meet—if, indeed, he does not surpass—the standards of the tradition in which he works as it is an evaluation of his individualistic combination of the ingredients that make a comic strip."

I submitted the article to Frank McLaughlin, editor of Media & Methods, hoping he would publish it as a corrective to the fiasco he'd wrought with the earlier piece. But the article was never published. Media & Methods was soon deceased, but the essence of my article is preserved in the first chapter of a book of mine, The Art of the Funnies (1994), which you can order on this website, just a click or so away.

The M&M piece wasn't my first essay into comics criticism. In freshman English in college, urged to write our term papers about something we knew about, I'd written a long paper on comic strips. This relic, however, has long since disappeared. Blondie figured in it, as I recall, and Little Abner and Pogo. But I kept no copy of it. In those primitive days before Xerox, the only way to have a copy of your work was to laboriously type it twice or to make a "carbon copy" by inserting between two sheets of typing paper a greasy piece of carbon paper that contaminated your fingers and resulted in all your pages bearing a smudged version of your finger-prints. Or one could employ amanuenses to make a fair copy by hand. I, alas, did none of these things, and so posterity is deprived of the infant ideas of my first venture into the realm of comics criticism.

My reaction to the ignorance on display in the M&M article had been to rehearse the history of comic strips in order to show that the seemingly confused melee of graphic mannerisms and story material in the newspaper funnies was actually archeological evidence of an orderly growth and development, but as I wended my way through Stephan Becker's book, I chanced upon something else, something that would give shape to other ideas about comics that were only shadows lurking in the back of my mind.

The M&M writer, while flailing around attempting to understand what he was writing about, had overlooked altogether the most striking feature of his subject. He failed to recognize comics as a unique medium, a visual one. He wrote about characters and settings (Blondie and Dagwood in a domestic comedy, Pogo and Albert in a swamp), but these aspects of comics are fundamentally literary, and comics, despite their narrative bent, are essentially a visual medium. In short, he said almost nothing about the pictures. Being myself a cartoonist (of the bush league variety), I thought the oversight was significant. The proper appreciation of the art of cartooning ought to involve pictures as well as words. A legitimate criticism of comics must embrace not just characterization and plot and storyline and narrative theme—the literary aspects of the medium—but the role of pictures in this otherwise literary enterprise. And it was Becker who offered a way of contemplating the whole of comics, not just its literary facets.

Becker looked at the Yellow Kid's nightshirt, that saffron beacon in the midst of Richard F. Outcault's pictures of slum kids, and fastened on the words thereon. The Kid "spoke" by means of the words lettered on the yellow expanse of his gown. With these messages, Becker astutely observed, "the written word had moved into the drawing; it was no longer simply a caption or a legend."

I'll overlook for the nonce that Outcault was probably not the first artist to put words into his drawings instead of consigning them to caption status below the picture. My epiphany came with what Becker said next, that the words and the pictures in comics were strangely interdependent—that "neither was satisfactory without the other" (Becker's emphasis).

Here, I thought, was the beginning of an aesthetic theory for comics. If, in a given comic strip, the joke is achieved entirely by the verbal content, then that strip is not as good an example of the cartoonist's art as a comic strip in which the joke is dependent upon both pictures and words. The art of cartooning, then, consists mostly of blending the visual and the verbal, and in the best examples of the artform, the pictures and the words blend to achieve a meaning that neither is capable of alone without the other. I've said this so many times in so many places that it's become, I'm sure, a mantra by which I am identified and pilloried. And for that, I blame Stephan Becker: it is his fault, not mine.

*****

I REALIZED AT ONCE THAT THIS FORMULATION was scarcely the sole criterion of excellence in cartooning. Not every comic strip is a perfect blend of the visual and the verbal every time. Serious storytelling strips, for instance, often rattle on for days without any noticeable visual-verbal blending. In these cases, there were other, narrative, purposes being served (all of which are laboriously explored in The Art of the Funnies and its sequel, The Art of the Comic Book). Visual-verbal blending was not the only principle of my emerging theory; but it was the first.

The visual-verbal blend principle is the first principle of an critical theory of comic strips for two reasons. It is first in importance: it derives directly from the very nature of the art. But it is first also because it is the first step in the process of evaluation, a process that involves making a successive series of "allowances" by which the visual-verbal blend principle is modified to accommodate the various categories and genres of comic strips. Many comic strips (those that tell continuing stories, particularly) cannot consistently meet the visual-verbal blend criterion. And yet many of them are excellent strips. Their excellence derives from other aspects of the art.

Dondi and Peanuts are both about children, but Dondi is a storytelling strip about an orphan boy, and it seeks in its soap opera tales and realistic rendering an illusion of real life. Dondi can be faulted when it falls short of achieving that illusion; Peanuts, which, ostensibly, aims simply to make us laugh, cannot. We can look for visual-verbal blend in both strips, but if Dondi fails to achieve it as consistently as Peanuts, there may be good reasons for that failure—reasons peculiar to the continuity genre.

Because storytelling strips tell stories that continue from day-to-day, they are freighted with an expository burden that gag strips, those that tell a different joke every day, never have to shoulder. Continuity strips tend to be much more verbal than gag strips, and the more exposition needed, the more verbal and less visual the strip becomes. A diligent cartoonist, however, attempts to restore the visual-verbal balance by resorting to variety in his compositions. Changing perspective, camera-distance, texture, and the like gives emphasis to the visual component and thereby revives the impression of visual-verbal blending. To the extent that a cartoonist tries to maintain the visual character of his strip in the face of the expository imperative for more verbiage, so is his work better than that of a cartoonist who gives us a panel-by-panel parade of talking faces, all the same distance from the camera.

Other criteria that apply more to storytelling strips than gag strips include such things as characterization, realism in illustration, authentic-sounding dialogue and so on. Once we start traipsing along this trail, we pretty quickly wander far afield from simple visual-verbal blending.

But the notion of a visual-verbal blend, it seems to me, provides critics of the medium with a way into the artform, a place at which to begin evaluating the effectiveness of a particular work. To begin—to enter the work—by looking for a visual-verbal blend automatically makes the visual content of the work as important as the verbal (or literary) content. The questions to ask focus on more than just the narrative. Does this strip make sense without the words? Without the pictures? If so, it is somewhat less an example of the cartoonist's art. By the same token, if the words in a comic strip make no sense without the pictures, we've identified, in that case, the role that pictures play in a visual-verbal medium. As a method of analysis, it focuses on the pictures as well as the words, and that, when considering a visual medium, seems eminently appropriate.

Moreover, it seems to me that this approach mimics the way cartoonists think: cartoonists usually (but not, probably, always) conjure up their cartoons by thinking in pictures as well as words. That particular quirk of the creative process is one of the things that makes them cartoonists instead of, say, portrait artists, who tend, I suppose, to think only in terms of ways of rendering facial characteristics faithfully (or satirically or horribly). Cartoonists do not, I suspect, consciously, deliberately, ponder visual-verbal blending in any sort of mechanistic way (as we are doing here). For them, the interdependence of words and pictures is, rather, a habit of thought, indulged more-or-less unconsciously. The conscious part of the process, the tip of the creative iceberg, is probably something like: How am I going to draw this without drawing it exactly the same way I've drawn it dozens of times before?

At this point in the gestation of these notions, I rested. For a time. I continued to write about cartooning though, and my so-called "theory of comics" acquired barnacles as I steered it through waves of a comics scholarship just coming in on the tide in such unrippled backwaters as The Menomonee Falls Gazette and Rockets Blast/Comic Collector. I made port, finally, at The Comics Journal, to which I've contributed for over thirty years. I also tried my hand at gag cartooning again—this time, by mail.

*****

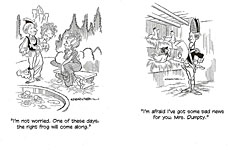

I WAS FULLY EMPLOYED then in a wholly unrelated kind of endeavor, so I had to squeeze my cartooning into an already pretty busy week. I ate a sandwich at my desk in the office and made pencil sketches for the cartoon ideas I'd solicited from prolific gag-writers around the country. On weekends, I'd ink the cartoons. I did about five a week this way, and when I had a batch of twenty, I sent them off to magazines, beginning with the highest paying and trickling slowly down the list. I'd do a batch of "general" cartoons (suitable for the Saturday Evening Post, National Enquirer, and all other "general interest" magazines); and then I'd do a batch of "girlies" for men's magazines (Playboy, Penthouse, Cavalier, and so on). (For all the tedious details of my gag cartooning career, see Harv’s Hindsight for February 2012.)

Men's magazines were about the only large category of magazines that still used single-panel cartoons. After a while, I noticed that I was selling better to men's magazines than to general interest magazines. So, reacting with the acumen of a bird dog that has flushed a covey of quail, I began concentrating on drawing barenekidwimmin for men's magazines. This suited me fine: I liked drawing barnekidwimmin better than drawing generals anyhow. But as you can tell, the choice of venue was scarcely my fault: I was merely reacting to market forces, responding to demand with an appropriate supply. Canny of me, I confess, but I submit that my motives were wholly financial and therefore, in a capitalist society, blameless. At your elbow, I’ve posted some of my favorite cartoons.

|

|

|

|

|

|

After three or four years of this, I'd had enough. Doing cartoons "on speculation," hoping to sell one or more, is a draining enterprise. All that work, and so little prospect of reward. I did pretty well with the girlie cartoons: I sold at the rate of about 50-60 percent albeit never to the high-paying markets like Playboy. But for the last year or so, I'd been doing a 4-page comic strip for one of Dugent’s magazines. It would prove my undoing as a working gag cartoonist.

Leda’s Ugly Duck was about a swan (as anyone with a nodding familiarity with the Hans Christian Andersen tale knows) and his dubious relationship with Leda, a pivotal figure, so to speak, in Greek mythology: Zeus, infatuated by her beauty after seeing her naked body while she was bathing, took the form of a swan and seduced her, a copulation that led to the birth of the heroes and heroines who created the Athenian civilization. My Leda, a wood nymph of unabashed nudity, was more interested in sex than my swan was, and I had a lot of fun luxuriating in cartoon carnality. And in financial reward without speculation.

|

|

|

|

Leda’s Ugly Duck was a commission job so I knew if my rough was approved, the rest of my work on the strip wouldn't be "on spec": it would be purchased. Guaranteed. So, naturally, I concentrated on producing Leda, foregoing gag cartoons. Alas, my fiscal bonanza was short-lived: the magazine, which had been published for decades, shut down after Leda had run in only about eight issues. Whether there was a cause-and-effect connection I don’t know. I contemplated plunging back into "speculation." But after the intoxicating Leda interlude, working “on spec” seemed like more labor than I wanted in my spare time. Besides, I'd suddenly, unexpectedly, had a new distraction thrust upon me. Again, not my fault.

*****

THE NEXT

PHASE IN MY ADDICTION was inaugurated by a letter from Milton Caniff.

More like a note, I suppose—just a 5x7-inch piece of paper with his name

printed at the top. Hand-lettered. "Harv," he began, "Today my

agent, Toni Mendez, asked if I thought you might be interested in doing that

definitive book everyone talks about." The "definitive book" was

his biography.

Although Caniff was inspired to write me about this project because his letterer, Shel Dorf (founder of the San Diego Comicon), had sent him a copy of an article I'd done, Caniff had written me once or twice before, usually notes of the same dimension as this one, to thank me for mentioning his name in something I'd written. He was pretty astute about this brand of public relations. His motto, once lettered on a card taped to his wall, was "Write that note! Make that phone call!"

One time when I was interviewing him in his studio, he took a break from his drawingboard (he was always working while answering my questions) to make a phone call to a reporter on a newspaper in Dayton, Ohio, his home town. The reporter had mentioned Caniff in a story he'd written about homecoming, and the cartoonist phoned him to acknowledge the "mention." It was a short conversation: Caniff was brilliant at packing a few sentences with punchy witticisms that would amuse as well as gratify. After he hung up, he turned to me and grinned: "It's like a pilot leaving the cockpit and walking back through the plane to talk with his crew," he said. "It raises the spirits of the troops."

Caniff often deployed such military lingo: he'd achieved both fame and fortune with comic strips about the Air Force. And he spent a lifetime raising the spirits of the troops in his profession: almost every cartoonist who was working during Caniff's long career can tell about the note he received, complimenting him on a particular day's strip or gag.

By the time I was interviewing Caniff, he'd sold his studio and home in Palm Springs, California, and had returned to New York City, where he rented two apartments in a building on East 45th Street. He lived in 31F on the thirty-first floor; his studio was in 5E, twenty-six floors below. He commuted by elevator.

The two apartments were identical in size and configuration. Each had one small bedroom, a bathroom, a livingroom, and a kitchenette. A short, narrow passageway brought visitors immediately into the livingroom, at which point, the passageway was joined at right angles by a longer corridor that led past the kitchenette to the bedroom and bath. In the Caniffs' living quarters, the hall led to the left; in his studio, to the right. The walls of the livingroom in the studio were hung with the works of cartooning friends mostly—Mort Walker, Walt Kelly, Harry Devlin, several by Noel Sickles, a few by Bill Mauldin.

The studio's several ceiling-to-floor bookcases bulged with an eclectic assortment of reference volumes, covering an astonishing array of subjects: illustrated books on military uniforms, flags, ships, and airplanes; The Air Force Wife by Shea, The Uniform Code of Military Justice, 100,000 Years of Daily Life: A Visual History, some standard reference tools (dictionaries, the World Book Encyclopedia with yearbooks, Roget's Thesaurus, Synonym Finder, a couple almanacs, The U.S. Air Force Dictionary, The American Thesaurus of Slang) and some nonstandard resources (Dictionary of Superstitions, Dictionary of the Underworld, Kenkyusha's New Japanese-English Dictionary, a dictionary of Black English, Merck's medical manual), several histories of the comics and collections of reprinted strips and cartoons, Rothenberg's Legal Protection of Literature, Art, and Music, Lowell Thomas' Back to Mandalay, Selected Letters of James Thurber, Here Is Your War by Ernie Pyle, a book on karate, Benet's John Brown's Body, and Principles of Highway Construction—in short, such an unruly tumult of subjects that only the owner's profession could explain the rationale of the collection. Tucked between books or on top of them were a few file folders, envelope boxes, piles of typing paper, and other miscellaneous caches of supplies.

The room was dominated by Caniff's drawing table in the center—a drawingboard resting on two three-foot-high filing cabinets with legroom between. Sometimes Caniff tilted the drawingboard into his lap and leaned back in his chair as he drew; sometimes he left the drawingboard resting flat on the cabinets and bent over his drawings as he worked. (Always, his right leg was elevated on an ever-present canvas campstool, a precaution against an attack of phlebitis.) Seated at his drawing table, Caniff had his back to a wall of bookshelves; in front of him against the opposite wall was a couch (over which hung most of the original artwork in the room), and between the drawing table and the couch, a coffeetable; at his right, two large windows overlooked the United Nations Plaza; turning to his left, he could look directly at the door to the outside hallway. A small portable television stood on a stand against the wall between the two windows; and under the window furthest from Caniff was a photocopier.

The bedroom down the hall was all but filled with filing cabinets containing correspondence and Caniff's reference files. There was also a single twin-sized bed where Caniff took naps. The kitchenette was small. Caniff kept a coffee pot brewing all the time, and Willie Tuck, his lifelong office manager, or sometimes Bunny, his wife, made lunches there for him, and they kept the counter and sink tidy. But they weren't given the license to do much straightening up in the livingroom, and the region around the drawing table was cluttered with the usual debris of the cartoonist's profession.

Notes were taped to the lamp over the drawingboard, and notes were taped to notes ad infinitum in streamers that sometimes dangled below the edge of the drawingboard. And newspaper clippings, photographs, file folders, magazines, pamphlets, envelopes of all sizes, and letters were heaped up in piles on nearly every available horizontal surface—on the tops of the filing cabinets upon which the drawingboard rested, on the bookcase shelf behind Caniff and on an adjacent tv tray stand that had been pressed into temporary (now permanent) service for the overflow, on an end table next to the couch, on the coffeetable, and, sometimes, on the couch itself.

When I visited, I moved a chair up to the drawing table at Caniff's left so we'd both be speaking into my tape-recorder, and I always had to create a space on the corner of the filing cabinet to put the machine. It was a small, hand-sized model, so it didn't take much room. And that was lucky because there never was much.

When Milton came in to work, the first thing he did was empty his pockets. He took out his wallet, pocket change, and an impressive clutch of keys on a ring and a chain, and he put them all on a shelf in the bookcase.

"I hate to sit around and work with anything in my pockets," he muttered as he did it. "It's lumpy enough without that," he added with a grin.

The biography had been Toni Mendez's idea, he claimed, and although he was a willing subject, he occasionally professed amazement at the whole notion.

"This kind of thing is unbelievable to me," he said once. "I never have got over the idea that I can't think anybody's interested. I know better, of course. But it still seems so self-serving to go back over all this stuff. Telling an anecdote because it's amusing—that's different. I do it in personal appearances all the time. Sometimes for a particular purpose, you don't want the truth to interfere with a good story, so you tailor it to amuse the audience or to make a point. But going through it all in the order it happened, that's something else."

He realized the publicity value of a biography, of course (and he certainly could calculate the effect on as respectful a biographer as I of remarks like the foregoing), but in the light of what others told me about his essential modesty, I suspect that his amazement was genuine albeit mild. He was scarcely in awe of himself, but whenever he had occasion to reflect on the project—whenever he thought of himself in a book that any substantial number of people might read—then he doubtless wondered that the life he led could interest them. At the edges of his consciousness, Caniff was certainly aware of his reputation and status as a kind of abstract fact of his life. But in the day-to-day business of living and working, that awareness was elbowed aside by the immediacy of the moment and the concerns of everyday matters.

Although he accepted gracefully the regard of his fans and colleagues, he was adept at turning attention away himself. He saw himself simply as a person who behaved logically in a given set of circumstances, not as a supremely gifted artist exercising his talents. Too much veneration in personal relations made him feel awkward. Shel Dorf was a devoted fan as well as a friend and his letterer, and he was not about to keep still in his reverence, but when he started working for his idol and was in daily contact with him, he found he had to change his tune:

"I found out very early on that it made him uncomfortable if I was too much in awe of him and his mega-star status," Dorf told me. "So I learned to refer to a third person, Milton Caniff —the legend not the man–about which my friend Milt would answer questions."

Upon getting Caniff's note about the "definitive book," I did a happy dance around the kitchen, explaining to my wife that doing such a book was probably what I'd been born to do. I didn't meet Caniff until a month or so later, when I went to Ohio State University where his 75th birthday was being celebrated. Meeting him, as anyone who's met him admits in mild amazement, is a flabbergasting experience. Caniff was wholly without affectation, and he had an affable manner that put every stranger at ease immediately. "Hello, Bob," he said in a roupy rumble, stretching out a hand to shake mine, "good to see you." Nothing extravagant. But his choice of words was perfect: good to see you, not good to meet you. "Meeting" is what strangers do; "seeing" is what old friends do.

During the weekend, Caniff found time to take me aside for a short discussion about the biography. He didn't want one of those "told to" books, he said—a faux autobiography written by a ghost. It would be my book. And I should say in it whatever I wanted to say; he'd live with it. The only things he'd want to change would be errors of fact, he said. And that's how we worked it. What happened next is, of course, all Caniff's fault: for the next eight years, I researched and wrote about Milton Caniff and his celebrated comic strips, Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon.

I made a couple visits to New York to interview him in his studio; otherwise, all the interviews were conducted by phone. I'd write for a few weeks, jotting down questions as they occurred, then phone him with the questions. He never shied away from a question.

The basis for my work was at Ohio State University: he'd recently left all his papers there, and they would form the kernel of the special collection that is now known as the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum. At the beginning, it was housed in a couple rooms in the old Journalism Building, dubbed the Milton Caniff Research Room. I made a couple of week-long visits there, taking copious notes and flagging reams of correspondence to be copied later by curator Lucy Caswell's patient assistants. I finished with an 1,800-page document, too monumental to interest any publisher. And that, too, was Milton's fault: his life was too long and too reflective of the history of the century to be briefly recounted.

The book languished for a dozen years, but my prolixity was eventually copy-edited by a friend, Daniel F. Yezbick, into a publishable dimension for Fantagraphics. The book, Meanwhile: A Biography of Milton Caniff, Creator of Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon, appeared in 2007, the centennial of Caniff's birth. (You can order your copy hereabouts; just click on the appropriate button.)

*****

SHORTLY AFTER I'D COMPLETED the 1,800-page draft of the Caniff book, I met Scott McCloud at a San Diego Comic Convention. He was on the brink of publishing his seminal Understanding Comics, and we immediately started quarreling about definitions of comics. We've quarreled ever since—albeit in a ferociously friendly way: we both like arguing. In producing a book about comics in comics form, McCloud attracted a lot of attention. Quite apart from the novelty of his method was the clarity he achieved in talking about complicated matters. Near the book's beginning, he arrives, after several attempts, at a workable definition of comics: comics are juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence. McCloud's thesis prompted much refining of definitions of comics hither and yon. Our arguments provoked me to refine mine, too. The tedious prose that follows, then, is his fault, not mine.

There are stories, narratives. There are verbal narratives (epic poems, novels), and there are pictorial narratives (Egyptian tomb paintings, the Bayeaux Tapestry). In my view, comics are a sub-set of pictorial narrative, therefore, all comics are pictorial narratives, but not all pictorial narratives are comics. Horses are quadrupeds, and dogs are quadrupeds, but horses are not dogs, and dogs are not horses. There are different kinds of quadrupeds, and there are different kinds of pictorial narratives. Egyptian tomb paintings are a species of pictorial narrative, but they aren't comics.

It

seems to me that the essential characteristic of "comics"—the thing

that distinguishes it from other kinds of pictorialnarratives—is the

incorporation of verbal content, which blends (as I've said countless times,

even herein) with the pictures to produce a fresh meaning that transcends the

separate meanings of the words by themselves or the pictures by themselves. To

McCloud, "sequence" is at the heart of the functioning of comics; to

me, "blending" verbal and visual content is. McCloud's definition

relies too heavily upon the pictorial character of comics and not enough upon

the verbal ingredient. Comics uniquely blend the two. No other form of static

visual narrative does this. McCloud includes verbal content (which he allows is

a kind of imagery), but it's the succession of images that is at the operative

core of his definition. I hasten to note, however, that regardless of emphasis,

neither sequence nor blending inherently excludes the other.

It

seems to me that the essential characteristic of "comics"—the thing

that distinguishes it from other kinds of pictorialnarratives—is the

incorporation of verbal content, which blends (as I've said countless times,

even herein) with the pictures to produce a fresh meaning that transcends the

separate meanings of the words by themselves or the pictures by themselves. To

McCloud, "sequence" is at the heart of the functioning of comics; to

me, "blending" verbal and visual content is. McCloud's definition

relies too heavily upon the pictorial character of comics and not enough upon

the verbal ingredient. Comics uniquely blend the two. No other form of static

visual narrative does this. McCloud includes verbal content (which he allows is

a kind of imagery), but it's the succession of images that is at the operative

core of his definition. I hasten to note, however, that regardless of emphasis,

neither sequence nor blending inherently excludes the other.

Rodolphe Topffer, the 19th century Swiss school teacher often dubbed the "father of comics" these days, seemed to lean in my direction. Commenting upon his verbal-visual creations, he wrote: "The drawings, without their text, would have only a vague meaning; the text, without the drawings, would have no meaning at all. The combination makes up a kind of novel, all the more unique in that it is no more like a novel than it is like anything else."

Topffer's comics would include even the humble single-panel gag cartoon in which, usually, the humor of the picture is secured, or revealed, by the caption below. The picture is in effect a puzzle, and the caption explains the puzzle—and vice versa. Part of the reason we laugh at a gag cartoon is because we are pleasantly surprised by cleverness of the puzzle’s solution. A gag cartoon often supplies the most vivid example of the verbal-visual blending that is at the core of the art of cartooning: the words make no comedic sense without the picture; the picture, no comedic sense without the captions.

|

|

The gag cartoon falls outside McCloud's definition because it is not a sequence of pictures. In fact, gag cartoons fall outside most definitions of comics. But not outside my description ("description" rather than "definition" because something that is defined seems completed, and I think comics are still evolving). In my view, comics consist of pictorial narratives or expositions in which words (often lettered into the picture area within speech balloons) usually contribute to the meaning of the pictures and vice versa. A pictorial narrative uses a sequence of juxtaposed pictures (i.e., a "strip" of pictures); pictorial exposition may do the same—or may not (as in single-panel cartoons—political cartoons as well as gag cartoons). My description is not a leak-proof formulation. It conveniently excludes some non-comics artifacts that McCloud's includes (a rebus, for instance); but it probably permits the inclusion of other non-comics. Comics, after all, are sometimes four-legged and sometimes two-legged and sometimes fly and sometimes don't.

But leak-proof or not, this proffer of a description sets some boundaries within which we can find most of the artistic endeavors we call comics. Even pantomime, or "wordless," comic strips—which, guided by this definition, we can see are pictorial narratives that dispense with the "usual" practice of using words as well as pictures. But that doesn't make the usual practice any the less usual. Pantomime cartoon strips are exceptional rather than usual. Usually, the interdependence of words and pictures is vital (if not essential) to comics—"vital" meaning "characteristic of life" rather than "indispensable."

The presence of verbiage in the same view or field of vision as the pictures gives immediacy to the combination, breathing the illusion of life into the medium. In a letter to me, Richard Kyle (who coined the term "graphic novel" in 1964) elaborated on the need he felt then, in 1964, for a new terminology for comic books instead of the terms already in circulation (albeit not very visibly by then—"illustories," concocted by Charles Biro, and "picto-fiction," the EC Comics contrivance): "Biro and the others apparently did not think about the fundamental nature of comics or understand some of the characteristics of our language. Comics are not 'illustories'— 'illustrated stories.' In comics, ideation, pictures, sound (including speech and sound effects), and indicators (such as motion lines and impact bursts) are all portrayed graphically in a single unified whole. Graphics do not 'illustrate' the story; they are the story. ... In the graphic story, all the universe and all the senses are portrayed graphically" [i.e., in the static visual mode].

Kyle's point, and mine (although he makes it better than I have), is that in comics everything is portrayed and conveyed in the same manner, visually. And the concurrent presence in the visual mode of speech as well as action, locale, etc., makes comics what they are, a unique kind of pictorial narrative. In fact, this concurrence, if not interdependence, may actually define the medium.

The importance to me of the verbal content in determining whether a pictorial narrative (or exposition) is comics may be best illustrated by a discussion of comic strips. Comic strips include an ingredient that single-panel gag cartoons do not. The technical hallmarks of comic strip art—the things that distinguish it—consist chiefly of narrative breakdown and speech balloons. Narrative breakdown is an aspect of sequencing images and is therefore peculiar to the comic strip branch of the cartooning family tree and to pictorial narrative in general. The narrative is broken down into separate key moments that can be depicted visually in ways that clearly convey the essential elements of the story. But in speech balloons, we have something that is unique to the comics medium. Speech balloons breathe into comics their peculiar life. In all other graphic representations—in all other pictorial narratives—characters are doomed to wordless posturing and pantomime. In comics, they speak. And they speak in the same mode as they appear—the visual not the audio mode of representation. This is unique.

The life-giving quality of these puffs of dialogue is something every cartoonist recognizes. Doonesbury's Garry Trudeau says it's "magic." The normally reclusive Trudeau made an appearance with Ted Koppel in 2002 on Koppel's late-night show, "Up Close." Koppel, noting that Trudeau always referred to himself as a writer and never as an artist, asked why.

"I feel more comfortable referring to myself as a writer," Trudeau said, "because it all starts with ideas, for me. And the writing is recreational. It's great fun. I love it. I don't think I'm particularly gifted as a writer. Comic strip writing is a weird intersection between two disciplines where you hope some kind of magic happens. If you look at a strip like Dilbert, which has awful art—and I'm the one who made the profession safe for bad art—Cathy, Dilbert, all the minimalist strips—if you look at the strip, the art is nothing to write home about, and the writing itself is sharp, but if it were in another form, it may not resonate as much as it does coming out of these little characters. There is something about the magic when you blend those two together. It just works."

If speech balloons give comics their life, then breaking the narrative into successive images gives that life duration, an existence beyond a moment. Narrative breakdown is to comics what time is to life. In fact, "timing"—pace as well as duration—is the second of the vital ingredients of comics. "Vital" but not, here, "unique." The sequential arrangement of panels cannot help but create time in some general way, but skillful manipulation of the sequencing can control time and use it to dramatic advantage.

*****

MY DESCRIPTION seems to exclude Alex Raymond's Flash Gordon and Harold Foster's Prince Valiant, iconic masterpieces that have served in such discussions as this to elevate the status of newspaper cartooning to Art. Ditto the somewhat less iconic Tarzan by Burne Hogarth and Lance by Warren Tufts. And for a long time, I agreed with the implications of my visual-verbal blend theory: these works, I said, are not comics. They consist of pictures with text underneath telling a story. They are, perforce, illustrated narratives but not comics.

I have since thought better of this flip formulation. After all, the physical relationship of pictures to words is the same as in the venerable gag cartoon, and the words undoubtedly amplify the narrative import of the picture under which they appear, and vice versa. The words don't explain the pictures as they do in a gag cartoon: they are not the key to a puzzle that the picture represents as captions are to the picture in a good gag cartoon. The relationship between pictures and words in Prince Valiant or Flash Gordon seems tangential rather than integral. In most instances of these works of Raymond, Foster, Hogarth and Tufts, the narrative, the story, is carried almost entirely in the text. We can understand the story without considering the pictures.

Well, yes, but—but the pictures in Prince Valiant undeniably create the palpable ambiance of the story; they give it sweep and grandeur. And without the pictures, Flash Gordon is a shallow, sentimental saga. Many children's books are not substantially different in appearance from Prince Valiant and Flash Gordon: every page with its brief allotment of text carries an amplifying illustration. Still, Foster and Raymond did a little more for their narratives with their pictures than the average children's book illustration does for its narrative. Within the category of pictorial narrative, Prince Valiant and Flash Gordon and Tarzan and Lance are closer to being comics than they are to being illustrated children's books.

And that's where I'd like to leave this discussion—right here, with the question suspended in a warm limbo of imprecision, half-answered, half-unanswered, rather than to belabor it further with a fussy pedagogical exactitude. Art is not precise. And appreciation of the achievements in art don't require as much precision as the pedagogue imagines it does. In the last analysis (for the time being), comics are a species of pictorial narrative. So is a rebus. So is Prince Valiant. So are many of today's children's books. "Pictorial narrative" includes all of these as subsets. But the subsets are not interchangeable: each has distinguishing characteristics that set it apart from the others. Maybe Prince Valiant and its ilk belong in a subset all by themselves.

*****

BY THE TIME I MET Scott McCloud, I was already deeply into my next book, the first one I wrote after the Caniff epic. I'd cut my book-length teeth on Caniff, but the next book was Tom Inge's fault. Inge was, and is, the Robert Emory Blackwell Professor of Humanities at Randolph-Macon College in Ashland, Virginia. With the demeanor of a Southern gentleman to go with his accent and a scholar's slight stoop to go with his preoccupations, Inge did much pioneering work insinuating the study of comics into the curricula of universities and colleges, gaining entry, usually, through the ever-widening gateway of popular culture.

I knew Inge by reputation before we ever met, but our first encounter was pure serendipity, the stuff of giddy accident and comic operetta. In the winter of 1978, I'd re-worked several installments of my Menomonee Falls Gazette series on "The Theory of Comics" into a single article, "The Aesthetics of Comics," and shipped it off to the Journal of Popular Culture. Unbeknownst to me, the JPC had planned to devote an entire issue the next year to the subject of comics. And Inge was guest editor. My submission was forwarded to him, and, as he later told me, he could scarcely believe his eyes when he opened the envelope and found my piece in it: he had been planning, he said, to ask me to write exactly this kind of article for the Comics Issue.

The book project was not quite another chorus in the music of the spheres: it was arrived at in a much less circuitous manner. Inge was the popular culture editor for the University Press of Mississippi, and in that role, he phoned one day in 1993 to suggest that I might have the makings of a book in my files. I'd been writing for The Comics Journal for a dozen years or more by then, and in my reviews I'd emulated Thomas Babbington MacCaulay, a prolific 19th century Scot whose habit was to use book reviews as excuses for writing massive essays on subjects only tangential to the book's. With MacCaulay as my guide, I'd review a book reprinting Walt Kelly's Pogo, retailing en route the biography of the cartoonist and the entire history of the strip, including, in addition to the 'possum's early comic book incarnation, Kelly's apprenticeship in a ladies' underwear factory. Inge's notion was that I could probably put a few of these essays together with very little effort to make a more-or-less cohesive book that would fit handily on the popular culture shelf of the University Press's library. So that's what I did.

Surveying the pieces I'd done for the Journal, I noticed that they covered most of the principal figures and features in the history of comics, starting with some of the earliest masters of the craft—Bud Fisher, Winsor McCay, George McManus—and continuing through the heyday of adventure strips and the advent of the comic book and its subsequent flowering into graphic novel form in the last decades of the century just about to slam shut. I could arrange these chronologically and have a sort of "aesthetic history" of the medium. I reworked portions of most of the essays to eliminate their book review aspects, leaving only the discursive MacCaulayisms, and I wrote four or five completely new chapters to fill in the blanks. The book traced the growth of comics, the development and refinement of the artform, from their newspaper forcing bed in the 1890s through comic books in the 1930s to the underground comix of the 1960s and 1970s to the graphic novel of the 1980s, using as guideposts along the way the cartoonists whose works shaped and reshaped the medium most decisively.

The resulting opus was, alas, too long.

"We need a typescript that is 320 pages long," the editor of the Press insisted.

My book was twice that length. Despite my having acquiesced, at the beginning, to the length, now that I'd finished the book, I realized that the projected typescript of 320 pages was be too short to do what I now thought the book would do—namely, show the evolution of comics from strips to books. So I protested the 320-page limitation. But my protestations fell from my lips unheeded, as is often the case. The typescript the Press was looking to publish was a 320-page typescript. Length mattered; content did not. In their view, length was my province and therefore too much of it was my fault; in my view, length was an aspect of quality and therefore a mark of distinction, not a badge of blame. Writers who would be published, however, inevitably surrender to editorial dictates, and both parties count themselves blameless. They did here.

Happily, the organization of the typescript suggested a remedy: arranged in chronological order, the chapters of the first half of the book focused mostly on the newspaper strip history of comics; the second half, the comic book history. The comic book chapters didn't begin until after the chapter on the adventure strip of the 1930s. Then following chapters on comic book pioneers like Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, Jack Kirby and Will Eisner, came chapters on Peanuts and Beetle Bailey and the displacing of the adventure strip in daily newspapers by the emerging the gag strip.

With a little rearranging and some outright lopping off, I could get the "aesthetic history" of the comic strip into the allotted number of pages, beginning with the Yellow Kid and ending with Calvin and Hobbes. I dropped a chapter on Cliff Sterrett's Polly and Her Pals and a section on Crockett Johnson's Barnaby: both are inimitable, and while I'd included others of that stripe (E.C. Segar's Popeye and George Herriman's Krazy Kat), the emphasis in the book was on those who had set a pace that others emulated, so I could skip Polly and Barnaby without doing violence to the argument of the volume.

I finished at exactly 318 pages. For the sweet sake of punctilious perversity, I wrote a two-page conclusion and sent the whole thing off. It was published as The Art of the Funnies in 1994.

The discarded half of the typescript was almost immediately accepted for a second book, The Art of the Comic Book, which appeared in 1996. Together, the pair traced the development of the comics forms and exemplified various ways of evaluating, of appreciating, the medium—starting, in every case, with entering into exemplary works by looking for visual-verbal blending. In writing an introductory chapter for the sequel with a short bridge to its predecessor, I enjoyed a Cervantes moment when I alluded to the first volume as a "previous sally." Pretty feeble, I admit, but from such tiny turnings do harmless drudges like me syphon off secret intoxication.

Tom Inge, meanwhile, had not finished with me. He persuaded me to collect and edit the second of the University Press's "conversations with cartoonists" series, Milton Caniff Conversations (2002). And when Oxford University Press started looking for short biographies of cartoonists for its American National Biography, Inge slipped them my name. I've since done a score or so cartoonist biographies for this project, now expanded into the Web. The assignments have been masochistically gratifying: the challenge is to squeeze the research and opinion into the 1,000-word allotment, for me, as you might imagine by now, a herculean endeavor, but one that, once accomplished, prompts the silvery laughter of satisfaction.

*****

I HAD LONG AGO QUITE HAPPILY ABANDONED all hope of a cartooning career: from two minor skirmishes twenty years apart, I learned that I didn't really want to be a full-time cartoonist. The first of these revelations occurred in the early 1970s. It was Bill Sheridan's fault. One of the editors of Cartoon News, a sometimes monthly magazine, he decided to start a newspaper feature syndicate, and he asked me if I wanted to do a comic strip for it. At last! my inner self shrieked—just what I've always dreamed of!

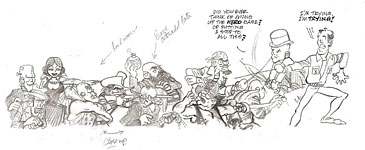

I pulled out model sheets for the characters in my most fondly conceived invention, Fiddlefoot, the aforementioned mock heroic saga, and started making notes about the inaugural sequence. The first strip, I decided, would be a single strip-wide panel depicting a mob of villainous looking hooligans attacking, at the far right, the gallant Fiddlefoot and his faithful sidekick, Threadbare. The hoodlums are equipped with bombs, cudgels, blunderbusses, and other very ugly looking weapons. Threadbare defends himself with his furled bumbershoot; Fiddlefoot, with a fencing foil. Says Threadbare: "Did you ever think of giving up the hero game? Of putting a stop to all this?" Says Fiddlefoot: "I'm trying, I'm trying."

|

|

|

The

second strip would show Fiddlefoot in different colorful heroic garb from panel

to panel, with the caption dribbling through the strip: "If you want to be

in the hero business ... you need the right equipment [in the pictures,

Fiddlefoot would change into a succession of picturesque costumes] ... Clothes

designers love people in the hero business."

I roughed out the first strip and was starting on the second when I had a thought that stopped me cold. If this worked out, I thought, I'd be drawing Fiddlefoot and Threadbare the rest of my life—the same bulging forehead, the same receding hairline and ponderous jaw. The same noses. Day after day, year after year, I'd be drawing the same noses over and over and over again. All at once, the bloom went off the rose of my life-long aspiration and in its place I saw just the thorny part—the tedium of repetitive work. I put my pencil down. I picked up all the rough drawings and the typed dialogue for two weeks' of the strip. I filed them in a single file folder and stowed it in the back of my file. I phoned Sheridan and told him I had decided not to do a comic strip for his infant syndicate.

Sheridan's syndicate, to the best of my knowledge, had a short life. Cartoon News ceased soon thereafter. I met and began a long correspondence with its other editor, onetime editorial cartoonist Jim Ivey, but I heard no more of Sheridan. And I thought no more of doing a comic strip. I did, however, perform my short-lived gag cartooning career after this adventure so the inner flame had not been thoroughly doused. It took Hank Ketcham to do that.

*****

I'D NEVER MET OR CORRESPONDED WITH THE CREATOR of Dennis the Menace, so when Ketcham phoned me one evening just before Christmas in 1988, it was wholly unexpected. (I have since learned that it was Ron Ferdinand, who did the Sunday Dennis, who prompted Ketcham in my direction.) Ketcham told me he was hoping to retire from drawing the daily Dennis panel; he'd given up doing the Sunday strip soon after it was launched, but now, he wanted to devote his time to painting and writing, and in order to do that, he needed to find someone to take over the panel. Would I be interested in trying out for the job?

By

the time he got to the question, his preamble had dropped enough hints that I

wasn't entirely bowled over by the invitation. The phone call itself had

surprised me, but after that, the question wasn't a shock. I laughed and said

he couldn't possibly realize the ramifications of his proposition. I had been

so enamored of his drawing style when Dennis was launched in 1951 that

I'd tried to imitate him, producing a panel cartoon for my high school

newspaper called I Have Skool, starring Little Louie Loudermouth. Louie

was a teenage version of Dennis, a neophyte juvenile delinquent. My school had

a larger than usual population of juvenile delinquents, so Louie was right at

home. Although a teenager, he was about Dennis' size, and he was a

thorough-going menace to his teachers and classmates. He looked a little like

Dennis around the eyes, nose, and mouth, but he had a swept-back ducktail and a

crew-cut top, a hair-style at the apogee of fashion at the time.

"I tried to imitate your drawing style then," I said, "and couldn't. I don't think I could do it now."

Seeking, no doubt, to reassure me, he said, "Oh, don't worry: I didn't draw very well then."

I was not reassured.

"We'll take it a step at a time," he went on. "We'll do it by stages, and if you successfully complete the first stage, we'll go on to the second and so on. And then if you complete all the steps and want to do the work, you'll have to come out here to live in Monterey and work in the studio."

By this time, I'd decided I'd give it a try. I didn't expect ever to be drawing Dennis: I told myself I was trying out just to see if I could pass the tests. And if I could and he offered me the job, I'd have a story to tell my grandchildren even if I declined the offer.

|

|

Ketcham

sent me model sheets of the characters and some paperback Dennis reprints to reacquaint me with the panel, a packet of tracing paper with the

guidelines for the daily panel already imprinted, and gags for six cartoons. I

was to draw the six cartoons in pencil and send them to him. The test was

whether I could set up the visual in a suitable fashion—could I compose the

visual elements for the gag in a clear and immediately understandable way? I

passed this test (barely—I wasn't aware enough, he said, of the

"acting" to be displayed by the characters), and we went on to the

next step. He returned my pencil drawings accompanied by his own penciled

versions of the same gags (much superior to mine in every way), telling me that

my next assignment was to produce the inked version of those drawings.

One of the cartoons took place in the attic of the next-door neighbor's house. In one corner of his drawing, Ketcham had put some vague doodles with the explanatory note, "Attic filled with memorabilia and junk." I stared at the drawing. Here was my moment of truth.

I decided right then that I couldn't go any further with the test, knowing that I didn't really want the job, knowing that I'd probably turn it down if it were offered. Although I wasn't all so certain of that. Penciling those first six gags, I thought, briefly, that I might take the job if offered; it was, then, worth making the try, step-by-step. But when I realized how good Ketcham really was—how much drawing he poured into those little panels—and when I realized that I'd probably never be as good as he was and how little I'd like doing all that drawing anyhow—I gave it up.

I phoned him and told him I couldn't—didn't want to—go on with it. He understood some of what I told him—that I didn't want to uproot my family and move to California. But I didn't tell him the real reasons I'd decided to stop. At the time, I was only vaguely aware of the real reasons. A couple years later, I reviewed his book about the first forty years of Dennis and sent him a copy of the review. By that time, I had come to a fuller understanding of what had happened when I saw that attic cartoon, and so I told him that rough drawing with his notes on it had revealed to me more about myself than I'd overtly recognized before. I kept a copy of my letter; here's what I wrote:

"About those of us who draw, it is often assumed that we 'love to draw.' I've seen the phrase used a lot about this cartoonist or that. I finally recognized a truth about myself that I'd never really admitted before: I don't love to draw. Not all that much. And it was the attic cartoon sketch that revealed this nugget of truth to me. Or, rather, your note: 'Attic filled with memorabilia and junk.' When I read those words, I knew—not clearly, but well enough. And after awhile, I knew it clearly: I'd have to love drawing in order to devote the time and energy that would be required to fill that attic with memorabilia and junk. Technical proficiency alone would not be enough to do the job. I'd have to love spending the time, first thinking of odd objects and then drawing them. And if I were going to spend every day drawing attics and autos and subways and crowds in stores not to mention gnarly old trees, flower gardens, door knobs, window sills, and all the other accouterments of everyday life—if I were going to be a cartoonist on a daily syndicated feature, I'd have to love to draw. And when I saw your notation, deep down I knew I didn't love drawing that much. I like drawing. But I love writing. In a lot of ways, writing is every bit as difficult as drawing. But I don't begrudge the time it takes. I welcome it. I often search out spare hours to devote to it. I like drawing cartoons and I love writing, and I love writing about cartoons and cartoonists more than anything else. And that's what I'm doing these days. When I drew my Louie Loudermouth cartoon in high school, I thought, at the time (but not now), that I was pretty good at copying you. But when I tried out for Dennis a couple years ago, I saw acres of nuance in your style that I'd never seen as a teenage cartoonist. To do all that so well, you have to love to draw. And I knew I didn't love it well enough. And so, I thought I should bow out as quickly and as gracefully as I could. So I did. Quickly anyhow; dunno about grace. Ahh, but what a thrill to have been asked...."

Admitting, at last, that I didn't love drawing, I also realized that was probably why I'd never pursued a career in cartooning with dedication enough to achieve it. My encounter with Dennis had explained my own life to me.

Ketcham wrote back, so kind and generous a note that it was an accolade, a blessing on the perversity of my choice of avocation.

"No wonder you 'love writing," he said, "—you do it so well. It flows nicely and it has a 'voice.' Yours. You're also a first-class picture-drawer, Bob—and I don't understand why you don't 'love' it. But you do know the territory, and the profession needs your extra sensitive insight. Again, merci millefois. Hank."

I could live with that. I no longer had anyone else to blame.