THE

GREAT TRIO COMPLETE AT LAST

Gorgeous

Biography of Alex Raymond

The

triumvirate is now complete. With the publication in the fall of 2007

of Tom Roberts’ Alex Raymond: His Life

and Art, we now have a respectable

book-length biography about each of the three cartoonists whose

illustrative styles in the 1930s set the fashion for serious

adventure comic strips, the other two being Milton

Caniff and Hal Foster.

The first of the trio of tomes was Brian M. Kane’s Hal Foster: Prince of Illustrators, Father of the Adventure Strip in 2001. While I may quibble with him about the “father of the adventure strip” designation—I’d nominate Roy Crane—the book itself is a delight. Available in paperback (with stylish dust-jacket flaps) and hardback (200 8x11-inch pages, $19.95 and $29.95 respectively), its emphasis is on illustration, and Kane, with access to the Foster family files, has assembled an impressive collection.

Only a few panels from Prince Valiant and Tarzan find their way into the book (for more of each, you need to acquire reprint volumes of the first from Fantagraphics—a few are still offered at fantagraphics.com; NBM, nbmpublishing.com, did the complete Foster Sunday Tarzan but it’s been out of print for some time, alas) so the lavishly illustrated pages present photographs of Foster at various stages of his life and career and an extensive assortment of such unpublished art as his Christmas cards and special illustrations for the program booklet of the Reubens Awards Dinner of the National Cartoonists Society—plus, in a glorious 16-page color section, paintings and full-color covers Foster did while still working as a commercial artist before taking up a commission in 1929 to illustrate Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan as a daily serial (which eventually was termed a “comic strip”) and, elsewhere, numerous cartoon sketches he made while portaging through Canada with his bride on their honeymoon.

The text, which traces Foster’s life from his Canadian origins to his Florida retirement, is somewhat off-balance: Kane devotes many paragraphs to Foster’s ancestry and early life in Canada, and if he’d given similar treatment to the artist’s career after getting Prince Valiant going in 1937, the book, doubtless, would be another 200 pages longer. But what text we have is luxuriant with little known facts about Foster: his occasional employment in the twenties as a guide on horseback and in canoe (and any fan of Prince Valiant will acknowledge Foster’s love of the out-of-doors), Foster’s selection for Valiant of a period in history that’s 500 years after the supposed time of the real King Arthur (and why Foster picked this period), Burroughs’ attempts to get the syndicate to pay Foster more (he was getting $125 a page at the peak on Tarzan; original art from this period is now sold for thousands), Foster’s working methods and advice to aspiring artists, why he selected John Cullen Murphy over Wally Wood and Gray Morrow to continue Prince Val (Murphy would do the Valiant page for 34 years, a record), and Foster’s sad last illness, when, due to surgery on his hip, he lost all memory of his 70-year career as an artist.

The book also includes a variety of tributes from other cartoonists and artists—Neal Adams, Barry Windsor-Smith, Mark Schultz, Joe Kubert, Carmine Infantino, and others—with an introduction by James Bama and a preface by Bob Lubbers. The perceptive Gil Kane is also quoted at some length: “One of the great things about his work is that in the area of romance he brought restraint, which is almost impossible. [Romance] is so elaborate and so full of souped-up accentuated quality that you never find elements of restraint, of harmony, of considered line, a considered design, or of naturalism.... [which] is one thing you hardly ever find with romance, and yet Foster’s work has the quality of naturalism within the framework of romanticism that gives it enormous range and appeal.”

Every great master of the medium should get at least a book like this one. Kane is to be applauded for his dedication and perseverance in his self-assigned task. And we all should own the book. Good as Kane’s book is on Foster, for more on Foster’s role in the history of the medium, you could, if so moved, consult a book of mine, The Art of the Funnies.

The second of the big three biographies is another book of mine, Meanwhile: A Biography of Milton Caniff, Creator of Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon (6x9-inch format, hardcover; $34.95), produced in the summer of 2007 by my stalwart publisher, Fantagraphics. The less said about this epic, perhaps, in the name of decorous discretion, the better (it’s 950 pages in length already—besides, an entirely adequate description of it is only a click away from the cover depicted at the top of the first page herewith).

My Caniff book, while amply illustrated, is more prose than picture, and Kane’s Hal Foster volume is more picture than prose; Roberts’ Raymond book is very nearly half-and-half. But of the latter two, Roberts’ is the superior: Roberts is a book designer and an illustrator himself (lately, he’s been making illustrations for Moonstone’s Doc Savage: The Lost Radio Scripts of Lester Dent as well as doing some of the covers for his own line of pulp story reprints, Black Dog Books, available through Amazon’s BookSurge imprint), and his book is an elegant example of the book designer’s art and crammed with beautiful illustrations by the artist Roberts’ so avidly admires, taken from Raymond’s pace-setting Flash Gordon, Secret Agent X-9, and Jungle Jim, the strips that established the artist’s reputation in the 1930s, and from Raymond’s stunning encore, the post-WWII Rip Kirby, plus book and magazine illustration and Christmas cards and pin-ups—a lavish compilation that includes much seldom (if ever) seen art, glowing on slick paper in full color whenever the original was in color.

Not only does Roberts cover Raymond’s early career assisting on Tim Tyler’s Luck and Blondie, but he examines Raymond’s lesser known achievements as a documentarian in the Marines during World War II and as an illustrator of fiction and advertising in the 1930s and 1940s.

For the biographical text, Roberts interviewed members of the Raymond family (four of the artist’s five children and two of his brothers) and surviving friends and assistants (chiefly Ray Burns, who assisted on Rip Kirby) and twenty-two Marine Corps veterans. The result is the only complete biography of the famed cartoonist.

Alexander Gillespie Raymond, Jr. was born October 2, 1909, in New Rochelle, New York, the first of the seven children of Alexander Gillespie Raymond, a civil engineer, and Beatrice Wallaz Crossley. Young Raymond attended Iona Preparatory School in New Rochelle on an athletic scholarship, but his plans for higher education were curtailed due to his father’s death in 1922. By 1928, money from the estate had run out, and at eighteen, Raymond went to work in order to help support the family, taking a position as an order clerk in the Wall Street brokerage firm of Chisholm and Chapman.

When he lost this position in the wake of the 1929 stock market crash, he was encouraged to exploit his talent for drawing by his neighbor, Russ Westover, the creator of the comic strip Tille the Toiler. For two months, Raymond was able to take night classes at the Grand Central School of Art, working days as a solicitor for the James Boyd Mortgage firm. On New Year’s Eve as 1930 turned into 1931, Raymond married Helen Frances Williams; they had five children.

Subsequently, in May 1931, he briefly assisted Westover, who soon secured additional work for him in the art department of King Features Syndicate, where the youth came to the attention of Chic Young; soon Raymond was assisting on Young’s Blondie. In late 1931, Raymond began assisting Young’s brother Lyman on Tim Tyler’s Luck. Cast initially in the mold of Bobby Thatcher and others of that ilk, Tim Tyler's Luck had started August 13, 1928, as an aviation strip with a kid hero. In 1932, Young took his cast to Africa, and the strip became a kind of jungle strip. At first, Young drew the strip in a cartoony style, but as the stories became more realistic, he hired assistants to render the adventures in a more realistic, illustrative manner.

“From May 1932, Raymond worked consistently with Lyman Young,” Roberts reports, “and on and off for Chic Young. Hardly a week would pass that Raymond didn’t work on either (or both) the daily or the Sunday Tim Tyler’s Luck.” Raymond did all the figure drawing in the daily and Sunday Tyler for most of 1933, drawing realistically in a confident outline style with virtually no shading or cross-hatching; it was thoroughly competent but undistinguished linework. Tyler, like all Sunday comic strips, was accompanied by a “topper,” a short shrift strip with other characters that ran at the top of the page carrying the main feature, and Raymond did Tyler’s topper, Kid Sister. Raymond had stopped working on Blondie just after Dagwood and the eponymous flapper married on February 17, 1933. (Raymond drew many of the people at the wedding.) By this time, he knew he wanted to pursue a career in cartooning; the King Features bull pen would be his launching pad.

In late 1933, King Features officials began looking for features to compete with two popular Sunday comic strips offered by rival syndicates—Buck Rogers, space adventures in a science fiction future, and Tarzan. In one of those fated celestial quirks, both of these strips had debuted on the same date, January 7, 1929.

Raymond submitted samples for the sf adventure, making two false starts —as detailed for the first time I know of by Roberts—before being awarded a Sunday page with Flash Gordon on the bottom two-thirds. He was then instructed to concoct a jungle strip as the page’s "topper.” This was Jungle Jim, which owed more to white hunter Frank Buck and animal trainer Clyde Beatty than to Burroughs.

At the same time, Raymond entered the syndicate's competition to find an artist for a new crime-fighting daily strip, which, in order to compete with the soaring popularity of Chester Gould's Dick Tracy and Norman Marsh’s Dan Dunn—Secret Operative 48, would be written by the master of hard-boiled detective fiction, Dashiell Hammett. Raymond was picked to do this strip, too, and thus he began 1934 as the illustrator of three comic strips, a virtually unprecedented circumstance—two Sunday features and a daily strip.

Doing three strips might seem, at first blush, an assignment for a superhuman, but every cartoonist doing a seven-day strip faced the same task: six daily strips and a Sunday page, which, typically, featured the flagship strip on the bottom two-thirds and a short two-tier “topper” at the top. Because of the visual detail Raymond produced for each strip, his workload was greater than that of many of his fellows at the time, but that was not the consequence so much of the number of strips as it was a measure of the artist’s dedication to his craft.

The Flash Gordon/Jungle Jim Sunday page debuted January 7 and daily Secret Agent X-9 two weeks later on January 22.

Raymond did Secret Agent X-9 for almost two years; Hammett was involved for only a little over a year. His last scripted story ended March 9, 1935. He reportedly plotted the next adventure (which ended April 20), but he had lost interest in the assignment—perhaps because of the more lucrative prospect awaiting him in Hollywood, where MGM wanted him to develop a sequel to “The Thin Man.” (After leaving X-9, Hammett would never again write fiction that was published.) Until a replacement could be found for Hammett, Raymond, it is often presumed, wrote the strip. His stories ran April 22-September 21, 1935, possibly although improbably the only evidence of his comic strip writing ability. (About which, more before we’re done here.)

Hammett's replacement was Leslie Charteris, creator of the Saint. The Charteris-Raymond collaboration (September 23-November 16, 1935) was the last X-9 adventure Raymond drew. That fall, he quit X-9 to concentrate on Flash and Jungle Jim.

Hammett, it turns out, proved a pretty good writer of comic strips. For one thing, he successfully translated his prose fiction detective persona into comic strip form. Hammett's X-9 is Sam Spade and the Continental Op all over again: tight-lipped and grim, he's a humorless, ruthless, and nameless man ("Call me Dexter—it's not my name, but it'll do"), dedicated without personal reservation to the fight against crime. (We find out his family was murdered by gangsters, so he swore vengeance.)

Raymond's visualization of Hammett's tough guy grates a little: his X-9 is a bit too dapper, more of a fashion model than a street fighter. But Hammett's dialogue reinstates his hero. When the femme fatale in the first adventure tries vamping X-9 to get her way—"I like you," she purrs, "I really do"—the agent cuts her short with a characteristically hard-boiled Hammett rejoinder: "I don't like you," he growls; "I really don't."

Hammett's first X-9 adventure ran for seven months. And the action never flags, nor does the suspense abate. As one of Hammett's biographers, William F. Nolan, observed: "In the pulp tradition of action, Hammett kept things moving. The opening adventure is full of gun fights, car crashes, gold shipments, piracy, explosions at sea, mysterious coded messages, and multiple murders." At first, Hammett fumbles in handling his new medium: the story skips from one panel to the next, leaving out key narrative elements, which we must later supply from subsequent contexts. Lapses in time between panels go unexplained. Action scenes, however, are staged across several panels, capitalizing on the visual excitement which the medium is capable of creating. Perhaps Hammett learned from such sequences the essential narrative capability of the medium: before long, his breakdowns pace events coherently and build suspense. I credit Hammett for these aspects of the strip's storytelling because after he left, the storytelling began to lurch markedly.

In contrast to the first three episodes by Hammett, the plots of the two by Raymond stumble along with motiveless actions, and narrative breakdown leap-frogs from one event to another, continuity gaps filled in with huge chunks of narration. Both these adventures rush to conclusion, much of the action taking place "off stage" so that it must be narrated to us in captions, diluting the drama of events. If Raymond did write these two sequences, they reveal clearly how badly this gifted illustrator needed a writer. Roberts believes these stories were concocted in story conferences at King Features where Raymond met with staff writers and editors. I suspect he is right: the unevenness of the storytelling from week to week suggests that more than one hand was on the tiller, and some of them had only a tenuous grasp.

Charteris was no more suited to scripting comic strips than Raymond. His X-9 story (his only work on the strip) offers a storyline that is too complicated for reading in installments, and he confuses his staggering story with too many characters and too little characterization.

If Raymond's handling of the writing for five months reveals his shortcomings for all to see, his visual treatment reaffirms his status as the leading illustrator in the comic strips of the period. All of his characters are fashion plates and the women are particularly delicious to look at. Raymond's surpassing achievement as an illustrator is highlighted by four weeks of the strip that he did not draw.

In the spring of 1935, Roberts tells us, the Hearst papers converted the Sunday comics section to tabloid format, an experiment that lasted for only six months, but Raymond felt it the whole time. Suddenly, his Jungle Jim topper became a full-page strip, effectively doubling Raymond’s Sunday drawing assignment—at precisely the time that X-9 lost its writer, increasing Raymond’s task on the daily strip. Raymond chained himself to the drawingboard for the first seven tabloid weeks, but he finally called a halt to the masochism. Jungle Jim was discontinued for six weeks, April 7 through May 12, and another artist was brought in to do the initial 24 strips in the first “Raymond-written” X-9, April 22-May 18.

It is usually assumed that Austin Briggs drew these strips, but Roberts says Briggs wasn’t hired until after the May 18 release. Starting with the third week of May, Briggs would pencil the strip for Raymond’s inks until Raymond returned to the task full-time at the end of July. But the first four weeks of the “Raymond story,” Roberts says were drawn by an otherwise virtually unknown, or at least hitherto not much remarked upon, artist, Allen Dean, who, subsequent to his X-9 gig, drew King of the Royal Mounted until 1938. The styles are clearly distinguishable: the work of Dean, who was an entirely competent illustrator, hasn't the delicacy of line and grace of figure composition that marks Raymond's work.

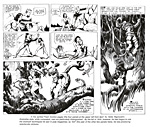

Despite Raymond's great

talent as an illustrator, his deployment of the comic strip medium at

this stage in his career was not very impressive. His strips often

lack the variety of panel composition—such things as varying

camera angles and distances—that would lend visual drama to the

story. Compared, say, to Caniff's work on Terry

and the Pirates a short time later, much of

Raymond's stint on X-9 seems a monotonous parade of panels in which the characters appear

always the same size, always seen from the same angle.  Moreover, Raymond's

people never change expression: X-9's grim albeit handsome visage

seems carved in stone, and Raymond's women, although superbly drawn

and seductively beautiful, all look alike, and when he makes both

young women in a story dark-haired—as he did in one of the

stories after Hammett left—we can't tell one from the other,

with much resulting confusion about the plot’s twists.

Moreover, Raymond's

people never change expression: X-9's grim albeit handsome visage

seems carved in stone, and Raymond's women, although superbly drawn

and seductively beautiful, all look alike, and when he makes both

young women in a story dark-haired—as he did in one of the

stories after Hammett left—we can't tell one from the other,

with much resulting confusion about the plot’s twists.

Raymond fared much better on the Sunday pages. The mode of storytelling there—by weekly installment—lent itself to his illustrator's skills without revealing his failings as a visual storyteller. And on the Sunday page, Raymond had more room in which to exercise his graphic skills. But it was more than format the fired Raymond's imagination. Jungle Jim alone was not a particularly remarkable accomplishment. Featuring the exploits of a hunter named Jim Bradley as he righted wrongs in the jungles of southeastern Asia, the strip was every bit as well-drawn as Secret Agent X-9, but after a couple of years, it is clear that Raymond's heart was not in the work.

His surpassing facility in figure drawing sustains the strip visually, but the compositions are dashed off: for panel after panel, the figures stand in studio poses by themselves with no atmospheric background. Raymond's creative energy was being poured into the feature at the bottom two-thirds of the page—Flash Gordon.

The space adventure tale focused on a handsome blond American polo player fast enough on the field to be called “Flash” Gordon, who, with bearded scientist Hans Zarkov and a beautiful girl named Dale Arden, is stranded on the planet Mongo where he battles the tyrant Ming. The stories are built archetypally around Flash as god-like redeemer, a savior from another world, who joins (and leads) an assortment of Ruritanian guerrillas in opposition to Ming the Merciless.

Raymond reportedly hired Don W. Moore, a staff writer at Argosy All-Story Weekly, to assist him in scripting the saga, but the ingenuity of the suspenseful and fast-paced plots did not imbue the characters with any more personality than required by formula fiction. The appeal of the feature derived almost entirely from Raymond's drawings, which improved rapidly during the first year of the strip, finally achieving a technical virtuosity matched on the comics pages only by Harold Foster in Prince Valiant. The graphic excellence that would distinguish Flash Gordon did not spring, full-blown, from Raymond's pen with the strip's debut. At first, he drew in the same unembellished illustrative manner he had used on Tim Tyler's Luck. But before long, he felt the influence of other styles of illustration, and the artwork in Flash began to change.

In rendering the futuristic architecture of Mongo, Raymond was influenced by Franklin Booth; and in figure drawing, by illustrators Matt Clark and John LaGatta. Like the latter, Raymond drew beautiful women exotically gowned in ways that revealed rather than concealed their contours, producing increasingly sexy renderings of Dale and the other women in the strip, all of whom started wearing exotic and revealing garments that sometimes left their wearers nearly naked. In drawing the men in his cast, Raymond, for a time, aped almost exactly Clark’s rugged masculine mannerisms. And the pictures in Flash Gordon are luxuriant with telling backgrounds, providing atmospheric surroundings against which the heroic posturing of the handsome blond hero acquires a majestic aura.

By August 1934, Raymond was feathering his linework and modeling figures more extensively, and he began brushing shading into the landscape of Mongo, giving the scenery texture as well as topography. And by the end of the year, Raymond's drawings showed the influence of the dry brush technique of pulp magazine illustrators: his brush strokes were orchestrations of tiny parallel lines, suggesting thereby the stroke of a brush nearly dry of ink. Although Raymond sometimes let his brush go dry, he normally kept enough ink on the implement to give his drawings a liquid sheen. The appearance of dry-brushing, however, gave his pictures great depth and textural beauty, and he employed the same techniques in Jungle Jim and Secret Agent X-9.

|

|

Raymond’s style continued to evolve, however, and by 1939, his lines are thinner, more continuous and graceful and less sketchy. His pictures of this period are defined more by linework and less by shading; they had become exquisite tableaux, delicately rendered in copious detail. In this period—from 1939 until 1944 when Raymond joined the Marines for the rest of World War II—Raymond's work closely resembled Hal Foster's in Prince Valiant; it was the only time the work of these two great illustrators looked much alike stylistically.

In the summer of 1934, Raymond began to vary the layout of the Flash page. The strip had been designed in a four-tier format—four stacked rows of panels. As Raymond's imagination became more and more engaged with the feature, this format seemed increasingly restrictive. In July, he started using an occasional two-tier panel in which a picture spanned vertically the space of two tiers on the four-tier grid in order to capture more dramatically the atmosphere in which his hero lived. A Booth-like city in the sky is pictured in one such large panel, the increased vertical space giving the scene a dramatic impact it would not have had in a single-tier panel.

Seeing the results, Raymond quickly abandoned the four-tier layout in favor of a three-tier arrangement that gave him room to develop all his pictures more extensively. With the larger panels, his backgrounds grew more lavish, and the strip's locale acquired an authentic ambiance. And in these spacious surroundings, the heroic posturing of his characters lent the entire enterprise a mythic air. The fantasy world of Flash Gordon was becoming manifestly real. By 1936, the strip was being drawn on a two-tier grid, every panel at least twice as large as the panels had been when Flash began.

Early in 1938, Raymond, perhaps following Foster's lead, had begun to eschew speech balloons in Flash, but he floated his characters' remarks in clusters of verbiage near their heads; a year later, he began burying speech within quotation marks in the caption blocks at the bottom of each panel, leaving the rest of the space free for drawing. By this time, his storytelling technique was established. He simply illustrated bits of narrative prose, in one superbly rendered picture after another.

There is no question that it was Raymond's art that brought Flash Gordon alive, his art that made the characters live in the minds of their readers. But that art could not flourish, could not reach the luxuriance of its full growth, in the small daily panels of Secret Agent X-9. Despite the considerable merit of Raymond's work on X-9, neither the format nor the subject was amenable to the levitating magic that his art performed in Flash. And while the format of Jungle Jim was initially ample enough, the subject did not fire Raymond's imagination as did the mythology of the redeemer Flash Gordon on the planet Mongo. Flash Gordon is a clear instance of subject and artist locked in symbiotic embrace, the artist driven to achieve at ever higher levels by his subject, the subject elevated in turn by the artist's endeavors.

But Raymond was not to be the only steward of his creations. A daily Flash Gordon strip debuted in 1940, drawn by Austin Briggs; Raymond was not at all involved with this version. Flash Gordon inspired celluloid interpretation that may be better known than the comic strip. In 1936, the first of three movie serials starring Buster Crabbe appeared. Jungle Jim spawned thirteen feature-length motion pictures (1948-1954), all starring Johnny Weismuller, who had left his Tarzan movie role after sixteen years. Both strips also resulted in radio and television series. Secret Agent X-9 was serialized in movies and radio, too, but with less success.

War had been brewing in Europe during the entire run of Raymond’s three strips, but comic strips, traditionally occupying a make-believe reality, mostly overlooked Hitler and his machinations. With the invasion of Poland in September 1939, however, and the take-over of France the next spring, no one could ignore the inevitable. In 1940, the United States inaugurated a draft to reconstitute its military forces, and in the spring of 1941, Raymond rallied Flash Gordon to the cause. Flash returned to Earth on July 6 and spent six months with Navy aviators over the Atlantic. Six months later, shortly after Pearl Harbor precipitated America’s plunge into the hostilities, Jungle Jim’s boat is torpedoed by an Axis submarine, and he’s soon in the U.S. Army, fighting the Japanese hordes. But Raymond still sat at his drawing board, growing more restive about doing his duty.

Over the next few years, four of his five brothers enlisted in various branches of military service, and finally Raymond could no longer restrain himself. Roberts quotes the artist: “Call it patriotism if you like, but I just had to get into this fight. I had three kids. I wasn’t young. And comic artists were getting easy deferments because they were considered necessary for morale at home. But I’ve always been the kind of a guy who gets a lump in his throat when a band plays the ‘Star Spangled Banner’ and the flag goes by.”

Raymond enlisted in the Marines on February 15, 1944, commissioned a captain in the Corps’ public relations arm. His last Flash Gordon appeared May 7; Jungle Jim, May 21. For six months in Philadelphia, he kept asking for combat duty and finally got it: he was assigned to the USS Gilbert Islands, an aircraft carrier in the Pacific, where, from April 1945 until the end of the War that fall, he served as Public Information Officer, charged with observing and documenting the life of a Marine squadron. Raymond took photographs, drew and painted pictures and designed posters, all intended to help present the Marine Corps in a positive light to the world beyond the Corps. He saw action from aboard ship in the South Pacific at Okinawa, Balikpapan, and Borneo. He was released from active duty on January 6, 1946, with the permanent rank of major.

Raymond expected to return to Flash Gordon and Jungle Jim, but when he inquired about his imminent return, he was officially advised, by letter, that he was expecting the impossible. Since he had left his comic strips voluntarily to enlist, King Features was not obliged to hire him back to do either strip (which would have displaced Briggs, who was then doing them both). According to Raymond relatives whom Roberts interviewed, Raymond carried for the rest of his life a bitter resentment about being “cast off with so little regard.”

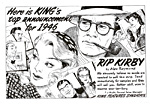

But King wasn’t about to let one of its stars go into eclipse: they asked him to create a new strip, offering him a huge signing bonus, and when Raymond signed, it was with the stipulation that he would own the new strip and receive 60 percent of the profits, not the usual fifty. Taking a suggestion by Ward Greene, the syndicate’s general manager, Raymond developed a daily-only strip about a detective.

A Marine officer returning to civilian life, the title character Rip Kirby (who was, for a time, named Rip O’Rourke) was a startling departure among comic strip heroes: though dashing and debonair, he was an unabashed intellectual (he even wore spectacles), moved in the best circles of society, employed a British man servant, and had a beautiful girlfriend who was a professional model. The girlfriend, a statuesque blonde named Honey Dorian (who, in preliminary sketches, was called Taffy), was a figment of the artist’s imagination, as almost all unbelievably beautiful women are, but Rip and his valet Desmond were modeled by Marines Raymond had served with.

|

|

|

In promoting the strip, Raymond was able to put aside his disappointment about not being able to return to Flash Gordon, assuming a rhetorical posture that he may, eventually, have come to believe, uttering this sadly ironic evasion: “There was nothing wrong with Flash Gordon,” he said, probably answering the question, Why aren’t you doing the strip that made you famous? “I still consider Flash excellent escapism. [But] the war made a realist out of me. I lost my taste for the fantastic out in the Pacific. ... The exaggerated adventure strip will always be popular, I suppose, but in my new feature, I wanted to get away from the wild type adventure. This is my own choice. I wanted to do something different and more down to earth. I think the fantastic stuff has been overdone. I think the field is jammed with it, and I’d rather in my new strip have a man that will be more real.”

Beginning March 4 (not, as Roberts has it, March 3, which was a Sunday in 1946), Rip Kirby started with a bang—a gunshot. In the four panels of the first day’s strip, we learn that Kirby has a valet who is as much devoted friend as servant and that Kirby is an “athlete, scientist, amateur sleuth” and a decorated Marine reservist. Then Raymond hangs us over a cliff in the last panel when Kirby hears a pistol shot. The rest of the opening week is as expertly done as the first day, a tour de force of serial suspense, every day ending with a provoking panel, and each strip telling us a little more about Kirby. By the sixth day, we’ve got Honey Dorian to look at, and Raymond puts her long legs on ample display while also revealing that his hero is a musician and likes to sit at his piano (a grand piano) and noodle around on the ivories.

|

|

For his new strip, which, as a daily, would never appear in color, Raymond developed yet another distinctive illustrative style, deploying solid blacks dramatically in contrast to crisp fine-line penwork, giving the strip an appearance that set it apart from his earlier work. Observes Roberts: “Not having the benefit of [Sunday] color, Raymond nevertheless [colored] through his use of varying linework ... [creating] color through contrast, though the use of black, white and gray areas.”

Rip Kiby achieved rapid success, and Raymond developed a memorable series of secondary characters, usually criminally inclined—the toothsome Pagan Lee, competition for Honey, and the disfigured Mangler, Rip’s nemesis, and Joe Seven, Fingers Moray, Lady Lillyput among others. Roberts feels that Raymond’s work in Rip Kirby “inspired all the soap opera style strips of the fifties and sixties,” from Rex Morgan to The Heart of Juliet Jones, On Stage, Apartment 3-G, and Ben Casey—“all,” Roberts says, “are stepchildren of Rip Kirby. Every one of these can trace its origins to the success of Raymond’s strip.”

Raymond was named Outstanding Cartoonist of the Year in 1949 by the National Cartoonists Society and served as the Society's third president (1950-52), establishing the organization's committee structure and actively campaigning for comics as an art form.

In the late 1930s, while also producing his two weekly comic strips, Raymond had actively pursued a career as an illustrator, influenced, perhaps, by Briggs, who had little regard for comic strip work, thinking illustration was the higher art form. Raymond illustrated covers in Hearst’s weekend magazine supplement and stories in Collier’s as well as other specialty magazines like The Elks Magazine, but after 1941, he stopped chasing after such assignments.

Said he: “I decided honestly that comic art work is an art form in itself. It reflects the life and times more accurately and is more creative. An illustrator works with camera and models. A comic artist begins with a white sheet of paper and is playwright, director, editor and artist all at once.”

As president of NCS, Raymond actively promoted this idea through personal appearances and exhibitions of original comic art by fellow NCS members (the first of which had taken place before Raymond was president, under the auspices of his predecessor, Milton Caniff).

Raymond worked no longer on Rip Kirby, ten years, than he did on Flash Gordon, and he might have advanced the art of daily strip cartooning even more had he not died, tragically, while driving fellow cartoonist Stan Drake (Juliet Jones) in the latter’s new sports car, a Corvette convertible, on September 6, 1956. Roberts rehearses the events of Raymond’s “last day” in detail.

It had rained earlier in the day, but it had stopped, briefly, long enough that they put the top down on the car; when it began raining again during Raymond’s stint at the wheel, he, not wanting to stop to put the top down, speeded up. When they surmounted a hill on Clappboard Road near Westport, Connecticut, the Corvette took flight, and when it landed at the side of the road, it turned over and slid, crashing against a tree. Raymond, who had fastened his seat belt when he took the wheel, was killed instantly; Drake, who was not belted in, was thrown clear and survived, although he had to have both ears re-attached surgically.

Raymond’s last Rip Kirby was published September 29, 1956. The strip was then assigned to John Prentice, who masterfully continued in Raymond’s manner until he died on May 23, 1999, the strip brought to a conclusion on June 26, 1999, by Frank Bolle (who, through no fault of his own, has administered the coup de grace to more strips than any other artist on the stripscape).

Some observers, including, it seems, Drake, believe that Raymond deliberately courted death in the months before the Clappboard Road catastrophe. In Hogan’s Alley No. 3, Arlen Schumer reports that Drake learned after the accident that “Raymond had been hospitalized due to injuries sustained in auto accidents” four times in the previous month. “He had been trying to kill himself,” Drake said. Raymond’s motive, according to Schumer, was that he was having an affair and his wife refused to give him a divorce (but they were, Schumer says, “living apart”).

Committing suicide strikes me as an odd way for a man of Raymond’s sophistication to react to his disappointment in romance, however profound it may have been, and Roberts apparently gives no credence to the idea: he doesn’t mention it. Nor, probably out of consideration for Raymond’s surviving family, does he mention any of Raymond’s alleged affairs, although he lets stand in a quotation from Raymond’s assistant, Ray Burns, a vague allusion to “personal problems” that Raymond’s sympathetic secretary was probably “privy to.”

But if Roberts left Raymond’s extramarital adventures out of the book, it is probably the only aspect of the famed artist’s life and art that isn’t between these covers.

For as long as I’ve known him—at least ten years, maybe fifteen or more—Tom Roberts has been working on a book about Raymond. Roberts is a perfectionist, and he wanted the Raymond book to look perfect. Or, if not perfect, at least it should look the way Roberts wanted it to look, exactly. He shopped the book around to various publishers, but, for one reason or another, none of them would serve his purpose. Mostly, they wanted to tell him how to do the book; and Roberts already knew how to do the book, and it wasn’t quite the way the publishers wanted him to do it.

With Adventure House, however, he finally came upon a publisher willing to let him design the book his way. And so he has. Tom set the type and laid out the pages; he’d already written the book and, over the years, refined his selection of illustrations. And the publisher contributed color on nearly every page. It is, without question, a gorgeous book, just the sort of setting Alex Raymond deserves.

The final result, Tom’s perfect book about Raymond, 320 pages in horizontal 12x9-inch format, provides an ample showcase for Raymond art, and Roberts has found troves of rare and sometimes previously unpublished pictures. There’s the book’s cover, for instance, which we displayed at the beginning of this homage to Raymond. Some who’ve seen this design have wondered why Roberts didn’t use a picture of Flash Gordon, undoubtedly Raymond’s most celebrated creation. One reason, Tom told me, is that he was looking for a horizontal orientation, and most of the best Flash pictures are vertical. Besides, Flash has been on view in many venues over the decades, and Tom wanted something fresh. So he settled on the pin-up you saw when we started out on this perambulation.

Raymond was an early devotee of the feminine form. As a kid, Raymond drew pictures of pretty girls; his earliest published drawing, at the age of twelve, was of a beautiful woman. The book contains a never-before-published series of photographs of Raymond drawing from a nude model. Like most cartoonists, Raymond, as a routine matter, drew from images in his head; most of the photographs we see of him drawing from models (mostly clothed models) are staged for publicity purposes, but occasionally, to keep his mental images real, he hired a model and drew from the model. This artist-and-model series represents one of those times.

The pin-up on the book’s cover is one of two or three Raymond produced for Esquire when the magazine was looking for a replacement for George Petty; two of Raymond’s offerings were published in the magazine, but not this one. It has never been published in color before. And Tom had access to the original art. A fresh, rare image taken from original art—just the thing for the cover of a coffee-table tome about one of America’s premiere artists.

And the art inside is just as stunning, and often, as rare. You’ll find several Flash Gordon color guides, for example—silver prints hand-colored by Raymond. And photographs of the Marine friends of Raymond’s who served as physical models for Rip Kirby and Desmond. All painstakingly arrayed to suit Roberts’ passion for perfection.

Tom showed me a photograph of Raymond and his wife Helen, looking at the original of a Secret Agent X-9 strip.

“I knew when the photograph was taken, generally,” Tom said, “but I couldn’t find the actual strip in any of the reprints or materials I had.”

The photograph doesn’t reproduce the art on the strip very clearly, but it’s clear enough to recognize solid black shapes and their sequence. Tom couldn’t find the corresponding strip in any Secret Agent X-9 published run. Was it ever published? Was this strip a rare, unpublished Secret Agent X-9?

Roberts puzzled over the mystery for months. Then he had a thought: maybe the photograph had been flopped when it was printed. He flopped it back, and then, almost immediately, he found the corresponding Secret Agent X-9 strip in the published run of the feature. Mystery solved; perfectionist satisfied.

Alas, Roberts prose is not among the book’s miscellaneous perfections and many virtues. Tom makes no claim to being a “writer.” His forte is book design. And he not only designed every page of this book: he also did all the preproduction work. The book is undeniably a glamorous showcase for Raymond’s superb art, but Roberts’ text falls far short of matching the visual content of the book. The verbiage is laced with cliches and brims with over-inflated ga-ga about Raymond’s talent—nay, genius. In describing the artist’s only appearance in Saturday Evening Post, Roberts writes: “These [three story] illustrations, for the grandest of all magazines, marked a pinnacle and a fitting climax to Raymond’s illustration career. After having finally broken into the highest profile magazine, he would never again illustrate the written word for any publication.” The venues in which Raymond’s illustrations appeared are invariably “prestigious,” the pictures “delightful” and “wonderful.”

Roberts also lets himself fall into a snare that awaits many biographers faced with writing about some aspect of the life story of a person about whom little is known outside of the work they have done. Lacking information about a particular period in the subject’s life, the biographer writes about the times in which the person lived and lavishes unnecessary paragraphs on the scenery. We learn, for instance, that Raymond’s boyhood home has “interior doors of tongue-and-grove construction” and “a coal-burning hot-air furnace with horizontal floor registers.” Horizontal floor registers? (as Steve Duin exclaims in his blog’s review).The narrative of Raymond’s childhood is festooned with biographical details about his father and his father’s ancestry.

The chapter on Raymond’s service in the Marine Corps is jammed with operational details about his squadron’s exploits, history of the ship, and military engagements at Guadalcanal and Bougainville. It imparts a military flavor to the narrative, but that’s much more than we need to know in order to appreciate Raymond’s accomplishments. (Oddly, considering Raymond’s interest in and skill at portraying pin-up quality pictures of toothsome women, this chapter includes only one pin-up; surely, under the circumstances, he produced more than one for the sake of his shipmates’ morale during his tour aboard the USS Gilbert Islands. If so, alas, Roberts was unable to find any of them.)

But Roberts’ obsession with minute detail, superfluous though some of it proves to be, also leads him to examine and discuss some matters seldom adequately dealt with. He describes the tasks accomplished in a typical syndicate bullpen, and we learn more about what Raymond did in the Marines than is available anywhere else. Roberts’ history of pin-ups from Charles Dana Gibson through Howard Chandler Christy and Harrison Fisher to George Petty is probably largely irrelevant and, by rhetorical weight, too long, but nonetheless welcome, and it includes at least one memorable sentence: “Changing styles and tastes brought new beauties to the ball.”

Roberts’ meticulousness is sometimes annoying, but it serves him well in masterful descriptions of such artistic endeavors as dry-brush illustrative technique, which he executes impressively with great verbal precision. On the other hand, his compulsion to include even tangential details increases the possibility of committing some drastic fubar (“f–ked up beyond all recognition,” an old Marine Corps expression). He tells us that Buck Rogers was syndicated by NEA (Newspaper Enterprise Association); that may be, but most of my sources say it was distributed by NNS (Nick Nichols Syndicate). And it was four years, not three, after Buck’s 1929 debut that King Features first entered the lists with a competitor, Brick Bradford, on August 21, 1933. In one place, Roberts says Buck “did not catch on quickly”; in another, a couple dozen pages later, he says it “very shortly found a huge readership.” Not quite as noticeable a gaffe as Roberts’ description of “pen and ink drawings” in which “Raymond effectively showcased his expert handling of the brush.” But the champion gasper of the lot is when, while pursuing Hammett’s career, he wanders into Hollywood and the Thin Man movies, saying that Nick Charles is played by William Powell and Charles’ wife Nora by Mary Astor, not Myrna Loy.

Startling as such errors might be, I’ve listed almost all of Roberts’ sins here. In other words, of the thousands of details he musters up for the book, he gets nearly all of them right, a signal accomplishment.

If Roberts isn’t as artistic a writer as he is book designer, his prose, however inflated and pretentious, gives us as complete and carefully researched a life of Raymond as we are likely to get. Moreover, to quibble about Roberts’ dubious writing skills is to miss the point: this is a book about an illustrator/cartoonist, and it is the book’s visual rhetoric, selected and often discovered by Roberts, that convinces us of Raymond’s achievement. Reflecting Roberts’ own interest, the book includes much more of Raymond’s oeuvre as an illustrator than of his comic strip work. But the latter is adequately represented, and Roberts supplies some superb Jungle Jim samples, which I gratefully appreciate: this strip is usually overlooked in deference to the more spectacular Flash Gordon.

At least once, however, the book cries out for more Rip Kirby: Roberts calls the strips of May 1956 “among the finest drawings ever done in the daily strip format” but provides only one strip by way of example.

Of Raymond’s purely illustration work, there’s more here than ever anywhere else.

Divided into chapters by the focus of Raymond’s work and career, the book devotes only 4 chapters, 112 of its 320 pages, to the comic strips. Raymond’s various illustration enterprises, including the Marine Corps and pin-ups, consume 5 chapters and 144 pages (2 more chapters and 162 pages if we include Christmas cards and a “gallery” of miscellaneous illustrations).

The allotment of chapters and pages reveals the emphasis of the book, but dividing Raymond’s career into discrete chapters, while a logical, perhaps even inevitable, way of proceeding, occasionally results in tangles that knot the narrative. Austin Briggs, for instance, was first employed by Raymond on Secret Agent X-9, but since the Flash Gordon chapter precedes the X-9 chapter, we meet Briggs without an adequate introduction, which Roberts supplies in the X-9 chapter. A quibble, I admit, but an annoyance to the reader—a trivial irritation, however, in the context of the monumental mass of details Roberts has assembled.

One of the details that Roberts takes up is the nagging puzzle of how much writing Raymond did on his strips. Don Moore has long been credited with “writing” Flash and, Roberts says, Jungle Jim. But King Features has nothing in its files that illuminates the issue, so Roberts resorts to published articles and other sources, making a good case for his contention that Moore’s “writing” was much less than scripting the strips. What Moore did, in Roberts’ judgement, was draft scripts from Raymond’s plot outlines, scripts that Raymond then refined, tinkering with the wording and other aspects of the narrative to suit his own sensibility. With access to the Raymond family archives, Roberts was able to examine what little evidence survives: papers that “show examples of Raymond writing and altering dialog for the Flash Gordon Sunday page.” But Roberts doesn’t let his case rest on this single shred of evidence.

From an interview with Raymond, probably in the spring of 1936, Roberts concludes that Moore didn’t begin writing for Raymond until sometime between August and December 1935. The article reports that Raymond “now has an assistant who handles the story angle, but the cartoonist still assembles the material.” Roberts adjusts the last to read “[story] material,” a modification that only muddies the water: if an assistant handles “the story angle,” what “story material” is left to assemble? The article’s original writer, Eleanor Key, may have been so baffled by the writing/drawing antics of cartoonists that by the “material” she says Raymond “assembled” she may have meant the pictures. But without access to the article itself, its entire context, we can’t say for sure, and the article is a newspaper clipping, undated, in the family collection, unavailable for checking. We must, therefore, trust Roberts’ judgement, which he exercises again in concluding his argument for Raymond’s primacy in the writing of Flash Gordon.

If Moore didn’t start working with Raymond until mid- or late-1936, then Raymond presumably wrote and scripted the strip for its first two-and-a-half years, and Roberts, inspecting the run of the feature, says “there’s no point where the scripting changes noticeably enough to suggest a new contributor.” Thus, an internal consistency demonstrates that Raymond “continued to control the direction and pacing” and spare verbal quality of the strips even after Moore joined him, further testimony in support of Roberts’ contention that Raymond did most of the “writing” of his strips.

Raymond also worked with other writers, King Features staffers, during the hiatus between Hammett and Charteris on Secret Agent X-9, a maneuver that Roberts suggests lay the groundwork for the method by which Rip Kirby was produced. With Rip Kirby, there is no doubt: the strip was concocted by Raymond in weekly story conferences with King’s general manager, Ward Greene, who had been writing novels in his off hours since 1929 and would eventually produce ten of them, including Death in the Deep South, a 1936 opus that was the basis for the movie “They Won’t Forget” with Claude Rains and Lana Turner. Sylvan Byck, King’s comics editor, was also part of the writing team. After the weekly confabulation, Raymond probably did the actual scripting and dialoging of the strip. After Greene died in 1956, the story conferences apparently expired, too, and the writing of Rip Kirby was done by Fred Dickensen, although Raymond may have “written” the strip for a brief time before Dickensen was signed up.

I don't mean by belaboring the writing question to belittle Raymond's achievements— only to pinpoint them, to give him his due for what he actually did. And he did plenty.

That Flash Gordon, Dale Arden, Ming the Merciless and all the rest have become a part of the American cultural heritage is, in itself, a testament to Raymond's accomplishment as well as to the power of the medium. Like Sherlock Holmes before him and James Bond afterwards, Flash Gordon leapt from the printed page into the hearts and minds of his readers and eventually emerged on the motion picture screen. But even before his celluloid incarnation in the 1936 serial, Flash was already as real to his readers as it is possible for a literary creation to be. And that was due almost entirely to Raymond, whose consummate artistry stamped the strip, the characters, and the stories with an illusion of reality that was more than convincing: it was spectacular. And Roberts’ book is a fittingly gorgeous testimony to Raymond’s achievement.

Raymond’s place in the history of his profession is established and secured by his brilliance as an illustrator. The technical triumph he achieved in the three strips he launched in 1934 helped establish the illustrative mode as the best way of visualizing a serious adventure story. His work and Foster's created the visual standard by which all such comic strips would henceforth be measured.

But, to betray both my

bias and my shameless entrepreneurial impulse, the real master of the

comic strip form as a verbal as well as a visual enterprise was

Milton Caniff—who, as Foster labored in the African jungles of

the Sunday Tarzan and

Raymond started dashing from the jungles of southeast Asia to the

drawingrooms of urban America to the alien tyranny of Ming's

Mongo—was waiting in the wings, doing a warm-up with a comic

strip about a boy who dreamed great adventures for himself. But

that’s another story. And it’s told elsewhere. You know

where.

GALLERY. Before we depart these premises, here are two examples of Raymond’s illustration work, in color: one from his magazine illustration career, the other from his Marine Corps efforts.

|

|

Footnit: The foregoing appeared initially in The Comics Journal, January 2009, No. 295.