OF

CARTOONING, RUBENS, AND ADAM'S RIB

Girlie

Cartoons and Barenekidwimmin

In

one of my former lives, I produced a regular column for the Revered Rockets Blast and Comic Collector (RBCC, as

it was known), the earliest long-lasting fanzine about comics,

published, initially, by Gordon Love, who was succeeded by James Van

Hise, who was editor/publisher when I was writing for it. In one of

the last issues, I wrote about my current short-lived career as the

propounder of magazine gag cartoons. I’d begun my part-time

pursuits in this realm by doing batches of about 20 cartoons every

month—one batch for “general interest” magazines

(like Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s,

etc.), then a batch for men’s magazines (Playboy,

Penthouse, Cavalier, etc.). To my everlasting

delight, the latter category, termed “girlie cartoons,”

sold much better than the “generals” did, so, being a

victim of the capitalist upbringing I’d suffered as a youth, I

soon began concentrating on “girlie” cartoons, eventually

to the exclusion of the other category altogether. It was not, I

confess, purely a marketing decision: I also liked drawing

barenekidwimmin. Here’s that antique RBCC essay, which, I

trust, explains everything.

Fashions come and go, in one era and out the other. In times of heightened social awareness, cartoonists, who subsist almost entirely on eraser crumbs, india ink, and other liquid emollients but who live by their wit, are apt to bend wit and elbow in an effort to justify their laboring in the ephemeral vineyards of mass entertainment. In such times, it's fashionable to say that cartoons are merely one of the many barricades from behind which potshots may be launched at the offending elements of civilization that threaten the Truth and Beauty of social order with hypocrisy and ugliness. But these justifications are made only to inquisitive newspaper and magazine reporters who attempt to pry meaningful phrases from naturally shy and retiring cartoonists. While it is true that cartoons can strip the emperor of his hypocrisy and leave him as naked as everyone always knew him to be, no cartoonist is likely to justify his work to another in terms of social conscience.

In simpler times, when we are spared the social imperative to be crusaders and other kinds of missionary, it's safe to admit the fundamental truth: the bottom line, so to speak, is that cartoonists are possessed by an irresistible urge to draw and a terminal if benevolent silliness. Left to his own devices, the cartoonist will obey these impulses and draw funny pictures. If his pictures scream Truth and Beauty in the wilderness, so be it; that's a nice by-product (perhaps even an inevitable by-product of humor), but it came into being almost incidentally. (The fact is that mendacity and ugliness are particularly attractive targets for a cartoonist: they scamper so amusingly when poked with the point of a pen.)

If nosy reporters and a trendy social sensitivity in the air make it embarrassing for your average cartoonist to admit without prevarication to a truth about his motives that seems childish in its simplicity, then the girlie cartoonist, who makes a specialty of drawing ladies in tantalizing states of undress, is likely to be embarrassed into absolute silence. Not only must he (like his fellow cartoonists) face down a charge of intemperate frivolousness, but he must out-maneuver a historical suspicion that in America has become institutionalized into tradition: the lurking Puritan conviction that an interest in naked ladies masks an interest in sex and that an interest in sex is a militant perversion. And with the renaissance of the feminist movement, the girlie cartoonist stands convicted not only of un-American activity but inhumanity as well: his well-turned girlies are sex objects. Bosoms bared, they deny women's rights. By drawing attention to female anatomy, naked ladies make sexual anonymity impossible, and sexual anonymity is, so the unraveling reasoning runs, essential to equal rights. Once unraveled, the logic resists raveling up again.

With hands and feet locked firmly in the stocks, the girlie cartoonist can scarcely comprehend the tangled skein of accusations let alone defend himself. In vain does he protest that human sexual anonymity is no more possible of achievement than propagation of the species by budding (Puritan myths to the contrary notwithstanding). Futilely does he suggest that cartoons about sex are as socially beneficial as cartoons about politics and other social ills: whatever is made the subject of humor is thereafter less capable of holding humanity enthralled by mystery, myth, or mendacity. Ineffectually does he fend off the charge of pornographer by asserting that there are no pornographic cartoons—only funny cartoons and unfunny cartoons (the latter being a contradiction in terms). Erroneously does he proclaim that he isn't interested in sex at all.

The girlie cartoonist would do better to admit the simple truth, childishly unfashionable though it be. The Puritans, after all, were at least half-right in their half-baked convictions: an interest in naked ladies does betray an interest in sex. Only in their belief that sex is perverted were the Puritans deluded: interest in sex is perverted only when furtive. The bravest of the girlie cartoonists is Bill Ward, "the headlight king," whose bountiful beauties take the exaggerative aspects of cartooning to their anatomical ultimate. Ward had the guts to admit—in print and on more than one occasion—the simple reason for his pushing a pen around hour-glass figures. "Why did I become a sexy girl artist, you ask? My first day in art school, the instructor said, ‘I suggest that you students concentrate on drawing what interests you the most . . . those who are animal lovers, draw animals; those who are sports lovers, draw athletes, etc.' Sooo," said Ward, "from then on, I've drawn girls."

|

|

In simpler untrendy times, so might Rubens, Titian and Tiepolo respond to that irreverent question. For they in their respective times and in their paintings' subjects were as much the friendly neighborhood pornographer as is the girlie cartoonist. All draw naked ladies because that's what interests them the most. There was, in those bygone ages of repressed social conscience, the alarmingly unfeminist judgement that the female form, unadorned and unabashed, was beautiful. Logic, well raveled in those pre-Puritan days, would probably even admit that eroticism had something to do with bringing in the verdict of beautiful. How else to account for the male fascination with what is, objectively considered, but an awkwardly lumpy composition fashioned from a rib-bone, a piece of rag, and a hank of hair?

In

these enlightened years of the twenty-first century, if you happen to

be possessed by an urge to draw naked ladies coupled to a terminal if

benevolent silliness, you don't become a painter whose nudes hang on

museum and gallery walls: you become a cartoonist whose nudes do

funny things on the pages of girlie magazines (which trade in

eroticism as well as humor). In the indulgence of his interest,

Ward—with bones, rags, hanks of hair, and guts—stands ham

to hock with the Grand Old Masters. He differs only in his choice of

markets and in his sense of humor. In his choice of markets, he has

no choice: girlie magazines are the only market for cartoons with

naked ladies in them. In the days before mass media, the Old Masters

drew and painted for the private collections of their patrons. (And

what is more furtive than that? But the Old Masters had no choice of

markets either.) And in drawing naked ladies in funny circumstances,

Ward and all the rest of us should, with whatever humility we can

muster, take our seats among the gods. A sense of humor is, after

all, the spark of divinity in us: in laughing at himself, man rises

above himself.

*****

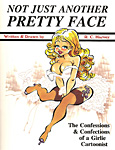

The

foregoing effusion I reprinted in a book that collected some of what

I regarded as my best girlie cartoons: Not

Just Another Pretty Face: The Confessions and Confections of a Girlie

Cartoonist, the cover of which I designed with

fiendish fervor in imitation of the covers of the classic family

magazine, The Saturday Evening Post.  The book,

by the way, is still available but only from me—for a mere $22,

including p&h; write me a note at the address at the end of the

scroll, and I’ll tell you how to order a copy. In addition to

cartoons, the book includes several essays on cartooning, one of

which serves as the Preface. Since it relates, vaguely, to the

preceding endeavor, I’m reproducing herewith:

The book,

by the way, is still available but only from me—for a mere $22,

including p&h; write me a note at the address at the end of the

scroll, and I’ll tell you how to order a copy. In addition to

cartoons, the book includes several essays on cartooning, one of

which serves as the Preface. Since it relates, vaguely, to the

preceding endeavor, I’m reproducing herewith:

You’ll read a lot about sex objects in this book, and you'll encounter an infuriatingly high number of cartoons that don't seem at all funny no matter how many lampshades you put on your head. I thought I'd do the decent thing for once (perhaps the only time in the entire contents of this tome) and warn you about both of these hazards while we're all assembled here at the beginning, preparing to dash barefoot through the pages at the right.

Before setting out, then, we may as well admit that the cartoonist is peculiarly vulnerable to attack for being a sexist pervert. He deals in a visual medium, and he draws in a sort of symbolic shorthand in which the easiest (because it's the most quickly understood) image is a stereotype. Stereotypical husbands forever march across the panels before us--and stereotypical wives and stereotypical snot-nosed kids, and bums and bosses, saints and sinners, thugs and tyrants. The visual shorthand telegraphs the cartoonist's message.

In humorous cartoons and comic strips, the stereotypical images are exaggerated for comic effect, and humanity parades before us in caricature. But even serious storytelling comic strips employ stereotypes: a razor-jawed Dick Tracy is only a slightly hyped-up version of the usual masculine hero's visage. And superhero comic books typically communicate the physical prowess of their costumed heroes with muscles that bulge and strain in turgid tension.

In such a milieu, the image of a beautiful woman is no different than the image of an ugly one: they're both stereotypes. But the image of a beautiful woman is not just another pretty face. It's also a body with the physical attributes of the sex. And those attributes, whether in humorous drawings or in serious ones, are likely to be exaggerated in order to enhance the symbolic communication function of the stereotype. Superheroines bulge as much as their masculine counterparts—and for the same reasons. And female anatomy in humorous comics is as exaggerated as any other physical feature on any other character—and for the same reasons.

But

all that exaggeration can get the hapless cartoonist into trouble

with certain segments of his audience. Take, for instance, the

cartoon I drew to celebrate the dawn of a new year in 1982.  With

typically benighted male sensitivity, I thought the cartoon ridiculed

the tendency in superhero comic books to rely more heavily upon words

to tell a story than upon pictures (a penchant I have always found

odd in a visual medium). But a lady critic of comics didn't see it

that way. Being of the mildly militant feminist persuasion, she

focused exclusively on the drawing of the masked and pendulous

superheroine. After describing my "female super-being"

("bending over, her huge globular breasts about to pop out of

the neckline . . . her equally hemispheric bottom waving in the

air"), the lady critic threw down the challenge of her question:

"Just what does the incredible exaggeration of this woman's

anatomy have to do with the humor of the Baby Comics New Year 1982?"

With

typically benighted male sensitivity, I thought the cartoon ridiculed

the tendency in superhero comic books to rely more heavily upon words

to tell a story than upon pictures (a penchant I have always found

odd in a visual medium). But a lady critic of comics didn't see it

that way. Being of the mildly militant feminist persuasion, she

focused exclusively on the drawing of the masked and pendulous

superheroine. After describing my "female super-being"

("bending over, her huge globular breasts about to pop out of

the neckline . . . her equally hemispheric bottom waving in the

air"), the lady critic threw down the challenge of her question:

"Just what does the incredible exaggeration of this woman's

anatomy have to do with the humor of the Baby Comics New Year 1982?"

The answer, I submit, is readily apparent to anyone not bent solely on making some sexist point.

The female super-being has as much to do with the point of the cartoon as the male super-being: both serve to put the cartoon in the context of superheroic comics. They are caricatures (as is everything in the cartoon) of superheroes, the background against which the cartoon operates to make its point. But just as the anatomy of the superhero in the cartoon is exaggerated by way of ridiculing strongmen in tights, so is the anatomy (and the pose) of the superheroine constructed to make a satiric point—the same point but a different sex.

And if you don't believe that comic book superheroines in tights reflect a preoccupation with tits and ass (a preoccupation that my superheroine's impossible and otherwise pointless pose was intended to satirize), then think again. And if you don't think my drawing is satirical in this way, then you misunderstand the ways in which exaggeration, caricature, and satire work.

If my superheroine is also erotic (and I'm reasonably sure she is), that serves merely to illustrate how difficult it is to satirize anything having to do with sex. Terry Southern and Mason Hoffenberg found that out in their novel Candy in the late 1950s. But I suspect their motives were no purer than mine.

Girlie cartoons of the sort I draw exist in a world of erotic fantasy: they depend for their humor upon the fantasies of that world. The world of erotic fantasy is a construct of the imagination--exactly (except for its subject) in the same way as the world of superheroes is a fantasy, a construct of the imagination. To create in one of those worlds—whether humorously or seriously—it is necessary to enter into the fantasy. I do that in my girlie cartoons as sure as Jack Kirby did in his superhero comics. Unfortunately, a willing entry into the world of erotic fantasy cannot help but act to blunt any satirical effect intended. When satire coexists with eroticism, the latter often overwhelms the former.

In a world less frazzled and overheated by moral crusades, both the eroticism and the satire would be seen. Even, perhaps, appreciated. The objective is to bring pleasure, after all—in my case, the pleasure of laughter. But the laughter must be partly at oneself.

The nature of my kind of girlie cartoon is, first, to seduce the viewer into indulging an erotic reverie, then to reveal how unrealistic that fantasy is by exaggerating it. The laughter at oneself comes, if it comes at all, when one realizes how absurd the fantasy is while at the same time admitting that it arises from a powerful preoccupation—powerful enough to have tricked one into indulging the fantasy in the first place.

Too few of us, sadly, can laugh at ourselves that readily (myself included). But it is no less a desirable goal, I think.

We pause too long at the eroticism. Sex is too powerful a preoccupation to permit the step back from oneself that is necessary before one can see himself as slightly ridiculous. As I said in the cartoon below, too often we "can't see the farce for the tease."

Until we can safely mingle sex and humor, we will still be too hung up on sex to be entirely healthy.

Until then, we will continue to hear strident voices raised against sexist cartoons. But let us not surrender too readily to these vociferous furies—no matter how righteous their anger, how worthy their cause, how sympathetic our beliefs. Let us not stop trying to provoke laughter. Laughter may well be our salvation. It can be a corrective. If we can laugh at ourselves, we take ourselves less seriously. And when that happens, perhaps the causes we so fervently espouse become slightly less urgent—and more amenable to the friendly addresses of quiet reason. Then we may accept ourselves as we are—even as we try to mold this poor clay into shapes more like a nobler vision.

We need the nobler vision, no question. But we need to see ourselves as we are, too. And mayhap fools with their motley caps and bells and their parades of stereotypes can help us to a perspective where both views are possible. In the hopeful meantime, let us not dim the only glimmer of light on this darkling plain. Why make ourselves all the more miserable by stilling the laughter? For the occasional relief from the grim business of living in an imperfect world that laughter affords us, we need as many sources of humor as possible. More, not fewer. Even girlie cartoons with their sexual stereotypes. Even when they sometimes fail to be funny, they carry on with the crusade nonetheless.