A Pretty

Girl Is Not a Malady

The

Evolution of Formula and the Celebrated Graphic Style of Cliff Sterrett

MANY EARLY

COMIC STRIPS EVOLVED from their initial formulaic treatments into something

quite different than originally intended. In Cliff Sterrett's Polly and Her

Pals, for example, we find a vivid instance of a strip that ran away with

its creator, leaving its conceptual notion far behind. Polly also

demonstrates better than most comic strips how amenable the art form is to

accommodating highly individual, even eccentric, graphic styles.

No

one who has ever seen Sterrett's mature artwork ever forgets it. It is not

only distinctive: it is unique. But Sterrett has another achievement in his

quiver: he is credited with creating the first pretty girl comic strip that

lasted. And Polly and Her Pals certainly lasted. It lasted from

December 4, 1912, until June 15, 1958—over 45 years. But I don't know that I'd

call it a "pretty girl strip."

In

the first place, Polly—for most of the strip's first two decades—was hardly

what I'd call pretty. She was more like, well—ugly. Fact is, Sterrett

couldn't draw a pretty girl. But he could draw a caricature of a pretty girl.

And, oddly enough, Sterrett's caricature was so deft that it established one of

the most potent visual stereotypes of the medium. In the second place, Polly wasn't really about a pretty girl at all, so how can it be called a

"pretty girl strip"? But let's do first things first.

About

Polly's face— Coulton Waugh, the medium's venerable historian with The

Comics (1947), is absolutely right when he says she was the "first of

a type—the famous comic type based on the French doll: bulging brow, tiny nose

and mouth, deep-set eyes." Sterrett's rendering of Polly's face (which he

did most often in profile) so acutely encoded the imagined essence of

"pretty girl" that it set the style for drawing the face of a pretty

girl in profile.  Countless comic strip females followed the fashion, beginning with Fritzi Ritz

and Tillie the Toiler and Winnie Winkle. Dumb Dora and Blondie and Casper's

wife Toots were all cast in the same mold—as were most of the nameless pretty

women walk-ons in the funnies. Even Russell Patterson and Don Flowers employed

the same durable doodle for the profiles of their lithesome beauties. And

traces of it can be found in even the more realistic treatment of girls' faces

in the work of cartoonists like Milton Caniff, Alex Raymond, John Prentice, and Frank Robbins. Of those renowned for pretty girls, perhaps only Alex

Kotsky has been successful in breaking the porcelain doll visage without

shattering at the same time his heroines' appealingly pretty appearance. Countless comic strip females followed the fashion, beginning with Fritzi Ritz

and Tillie the Toiler and Winnie Winkle. Dumb Dora and Blondie and Casper's

wife Toots were all cast in the same mold—as were most of the nameless pretty

women walk-ons in the funnies. Even Russell Patterson and Don Flowers employed

the same durable doodle for the profiles of their lithesome beauties. And

traces of it can be found in even the more realistic treatment of girls' faces

in the work of cartoonists like Milton Caniff, Alex Raymond, John Prentice, and Frank Robbins. Of those renowned for pretty girls, perhaps only Alex

Kotsky has been successful in breaking the porcelain doll visage without

shattering at the same time his heroines' appealingly pretty appearance.

Sterrett

scarcely thought he was setting a fashion, of course. He was just trying to

draw a pretty girl without offending the prudish public of the day. Her face,

therefore, was about all he had to work with. But he didn't care much about

his heroine anyway: by the time Polly's profile evolved, Sterrett was honing

his strip to take a bigger satirical slice at life than the frivolous

preoccupations of a pretty girl would allow for.

Sterrett

was working for the New York Evening Telegram on the eve of Polly's creation in 1912. Like George McManus (see Harv’s Hindsight for October 2009), he was doing an alternating anthology of comic strips

dealing with love and courtship and marriage and the tribulations of parenting

in the modern world—Before and After, When a Man's Married, and For

This We Have Daughters, a perspective in triptych on relations between the

sexes. Daughters contained the seed of Polly. It retailed the

trials to which a modern young woman subjected her somewhat old-fashioned

parents. The cast consisted of Pa and Ma and Molly. And a cat. (Don't forget

the cat.) This strip attracted the attention of the ever voracious press lord

William Randolph Hearst, always on the look-out for a new crowd-pleasing attraction

for his New York Evening Journal.

In

1912, an era was dawning, the age of the New Woman. The female population was

beginning to escape from the kitchen and the home and to take a place in the

surrounding social and vocational world. Sterrett capitalized on the

situation. In Daughters, he put the age-old struggle between the older

generation and its offspring in this new context, giving his strip a unique

twist: the daughter in Sterrett's strip had an ally in her mother because they

were both, in varying degrees, rebelling against the stereotypical role for

women that society had so long held sacred. And so poor Pa found himself

alone, his traditional sensibilities being constantly bombarded from every

quarter by new fashions in both clothes and manners, his once secure and sane

Victorian world in a state of continual comic turmoil.

Hearst

could see that this strip was in perfect tune with the times, and he quickly

bid for Sterrett's services. As was his custom, he offered the cartoonist

better financial rewards than the Evening Telegram, and by the end of

the year, Sterrett was in the Hearst stable, cranking out another version of For

This We Have Daughters, this one called Positive Polly.

Positive

Polly eventually became Polly and Her Pals, but not before it

evolved a bit. The theme of Daughters had not required a particularly

good-looking daughter. It was enough that she be relentlessly modern in her

conduct; she didn't need to be physically attractive. Since Hearst seemed to

want just another version of Daughters, Sterrett paid no particular

attention to Polly's physical charms. In fact, when he drew her, he made her

plain as a post. Within a month, however, her looks began to improve.

In

his Introduction to the Hyperion Press Polly and Her Pals (1977), comics

historian Bill Blackbeard speculates that Hearst had expected Sterrett

to produce an attractive version of the New Woman and that when he saw what the

cartoonist was doing, he ordered a change. And that makes sense, but we have

no indication that it was actually the press lord himself that inspired Polly's

improved appearance. Whatever the cause, by the early February 1913, Polly was

prettier—and more stylishly coiffured and attired. The pretty girl strip was

a-borning. But the improvement was attended by other troubles.

"You

have no idea of the strict censorship we were forced to work under in those

days," Sterrett complained to Martin Sheridan in his pioneering Comics

and Their Creators (1944). "In the first place, we couldn't show a

girl's leg above the top of her shoe. Furthermore, a comic strip kiss was

unheard of, and all the action had to take place and be completed before nine

o'clock."

He

felt the same restraint even after World War I. "Many letters of

condemnation arrived from clergymen who criticized my then-daring fashions.

And all I did was show a girl's ankle."

All

the while the pretty girl was gestating and occasionally showing her ankle, the

strip was changing. (Or perhaps not changing so much as "settling in"

on its true thematic foundation.) Given the strip's basic situation, the

comedy had to arise with Polly's father, the much put-upon Samuel Perkins. Paw

was the one whose outrage at the manners and mores of modern Youth inspired

laughter. And consequently—this being a comical strip rather than a serious

continuity—Paw soon became the star of the show, with Polly little more than

his foil (or, rather, the thorn in his side). Ditto Susie Perkins, the

embattled Paw's long-suffering spouse.

Paw's

stardom resulted in other subtle shiftings of emphasis in the strip. Once Paw

emerged as the source of the strip's comedy, Sterrett sought to wring

everything he could out of the circumstance. To this purpose, he surrounded

the old man with a cast of idiosyncratic secondary characters, each of whom

could introduce Paw to some aggravating aspect of modern life. In effect,

their assorted eccentricities were designed expressly to assail Paw with

modernity in all its variations and varieties.

Because

Sterrett's secondary characters all tended to be relatives of the Perkins

family who moved in to stay, before long their household was immense. First

came Delicia Hicks, a niece. Polly's age, she is not very bright and not very

attractive, and she thus offers another way of viewing the New Woman. Then

there was Ashur Url Perkins, a stupid and vain nephew who represents the male

half of the Younger Generation equation. Carrie Meek is Susie Perkins' sister,

a sharp-tongued widow whose chief function is to spoil rotten her daughter,

Gertrude—a brat of the first water. Aunt Maggie Hicks, however, proves a match

for the Meeks: a mountain of a woman, she is as powerful a personality as her

bulk would suggest. And there were others who showed up from time to

time--Uncle Ethelbert Armitage and his son (the same age—and temperament—as

Gertrude, with whom a rivalry quickly developed; ah, there was a battle of

giants). So large a household required servants, and they, too, added to Paw's

burden. A butler who was part of the original cast soon disappeared, and an

Oriental valet named Neewah became a permanent member of the ensemble. Ditto

three black servants (cook, maid, handyman)— Manda, Liza, and Cocoa.

Taken

altogether (as Paw had to take them)—personality quirks and tics with their

modern aspirations and interpretations—they constituted a formidable assault

force, all directed at poor Paw's tradition-bound proclivities. And so the

strip was about Paw's bouts with the Modern Age. With a sensibility rooted in

the Victorian times just past (as was the sensibility of most of the readership

of the day), Paw is forever taken aback by the antics of his more up-to-date

fellow cast members. (And so is his cat.) The strip would be more aptly titled The Trials of Paw Perkins, concentrating as it does on his attempts to

cope with his daughter, her beaux, his scapegrace nephew and his painfully

plain niece, his cousins and his uncles and his aunts and their spoiled

offspring.

As

penetrating a device for gaining comic insight into contemporary events as

Sterrett had concocted with these modifications to his strip's initial formula,

he is more revered today for his drawing style than his social commentary. And

rightly so. His satire, while adroit enough and humorous and wholly accomplished,

is not spectacular. His graphic style is.

Nor

is Sterrett much remembered today for his braving the censors or for his having

introduced to the funny papers what became the conventional way of drawing a

pretty girl's face. In both these departments (and in the arena of social

satire), he could be (and was) imitated. He is remembered—nay, acclaimed—for

that which is inimitable: his bizarre but decorative and supremely attractive

drawing style.

|

|

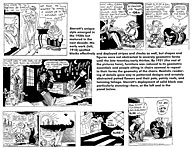

As

it reached its maturity in the twenties, Sterrett's style was a symphony of

patterned black and white designs and shapes. The syncopated rhythm of his

forms and lines did more than distinguish Sterrett's work with his own highly

individual stamp: it lifted Polly off the newspaper page. All other

strips in Polly's vicinity paled graphically into dull lines and drab

blobs. To say even this much—hyperbolic as it is—is not to say enough about

Sterrett's style. Unique, inimitable—spectacular. Still inadequate. These

words are words of appreciation not description. And until we can describe his

style, we will remain forever at once intrigued and baffled by it, tantalized

by the question: Just what, exactly, is it? How can it be described?

Waugh

made a noble attempt. He viewed Sterrett's unparalleled stylistic achievement

with a cartoonist's eye, a cartoonist's words: "Sterrett was an Old

Master at heart, one of the best and freest of them. In his portrayal of tiny

Maw and Paw, as well as the various relatives, he lets himself go and creates

an ultimate in wild stylization. These characters have a head ‘doodle' that

reminds one of a slightly flattened Edam cheese. Their noses are small rolls

stuck in front of two circles that touch. These are eyes, the irises of which

turn in together in a perpetual cross-eyed stare. The heads are squashed down

on tiny, neckless bodies whose leg extensions (what else can we call them?) are

sliced off to make enormous feet. Sterrett's anatomical phantasies reach their

limit with his animals; one, a very fine gray cat that accompanies Paw

[everywhere] and registers that tormented one's every mood, is perhaps his

noblest achievement. This cat marches with wild leg construction displaying ludicrous,

upturned feet."

But

there is more to Sterrett's style than this.

Waugh

senses an element of fine art in Sterrett's work, but the precision of his

description falters when he attempts to discuss it. "There is a sense of

pattern in Sterrett's work," he begins, "a very strong feel for

spotting and beauty of arrangement." And his verbal facility finally

trails off completely with the observation that Sterrett's drawing "has a

definite abstract art value."

Stephen

Becker, who chronicled the history of the medium the decade after Waugh

did, was not a cartoonist and therefore looked to art schools for guidance when

he came to Sterrett, and he does better at describing what he sees:

"In

the art professor's terms, Sterrett composed beautifully; each of his daily

panels is a delicate balance of black and white, and often one panel leads into

another through the simply rhythm of the lines. Sterrett usually dresses his

characters in striped or checked garments, and the play of line against shape

is masterly. If heads, hands, and feet were removed, what remained would be

pen-and-ink abstraction of a high order." This, at least, gives us

something to look for—something besides Edam cheeses and breakfast rolls,

imagery which, despite its antic accuracy, fails somehow to convey properly the

essence of Sterrett's style, its pervading sense of design.

Sterrett

himself supplied a clue to one of the guiding principles that apparently lies

behind his art. Sheridan unveils the clue: "The creator of Polly explained his unique style as an attempt to illustrate the futuristic in his

drawings. He portrays a cat with angles, furniture the same way. Sterrett's

is a symbolic world in figures."

"Futuristic."

The term is ambiguous as used by Sheridan. It can refer, simply, to things of

the future. But it also has a place in the lexicon of modern painting, and it

is to this that I think Sterrett was referring.

Aesthetic

theories of Futurism took root in the first decades of the 20th century at about the same time as Cubism flourished. These and other

contemporary theories of art—all lumped together under the rubric of “modern

art”— bloomed as artists reconceived the idea of art in the wake of

photography’s having superceded the traditional representational function of art.

Cubism made an effort to view (as it were) an object from all sides at once:

Cubists effectively flattened out the object, destroying the representational

character of their portrait of it by reducing it to its component geometric

shapes. The result was an arrangement of shapes and textures that was wholly

abstract. At the same time, there appeared to be a dynamic tension in the

relationship of the geometric forms—a suggestion of movement, of power in

motion.

Futurism

has its political and literary as well as its aesthetic aspects. Advocates of

this theory exalted speed, violent action, technology and machinery as evidence

of the power of the will in the dawning modern age, issuing great thumping

“manifestos” about “a racing automobile with its bonnet adorned with great

tubes like serpents with explosive breath ... a roaring motor car which seems

to run on machine-gun fire ... great-breasted locomotives, puffing on the rails

like enormous steel horses....”

Like

most modern art theorists, Futurists exuded obtuse argot because they were

groping for something that would rescue Art, and they didn’t know what,

exactly, that something was. So they beat drums of obscure and tortured verbal

formulations as if hoping that a useful “something” might be frightened out of

the surrounding undergrowth. As a result, it is almost impossible to find

artwork that embodies the lingo Futurists were bandying about. But we can look

at the pictures that these extravagances of language seemed to produce and see

various “somethings.”

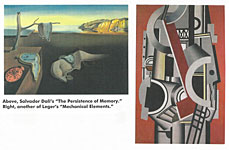

For

my purpose here, it is enough to note that Futuristic painters concerned

themselves with a sense of motion that could be revealed in the

juxtapositioning of texture and shape. Obviously, there is in Sterrett's work

much concern with the same things—the patterning of stripes and checks, of

blacks and whites, of lines and shapes. But there is an even closer connection

to Futurism.

In

their championing of modernity and its machinery, some Futuristic painters

incorporated machine-age ideas into their paintings by representing organic and

animate objects as if they were composed of mechanistic parts—metal tubes,

cubes, cylinders, spheres, and the like. One of the more famous of the

painters often dubbed Futuristic was Fernand Leger, who “wanted his

works to rival industrial products in their robust logic. Transforming the

figure into a machine and conflating machines with humanity, Leger developed a

striking language of abstraction” (Cole and Gealt in Art of the Western

World). In Leger’s well-known painting "Luncheon, Three Women"

with its tubular forms, mechanical rigidity, and angular geometry, there is

much to remind us of Sterrett's work. Moreover, in the designs behind the

women are many of the patterns Sterrett often used.

Leger's

painting was done in 1921. By the mid-twenties, artists everywhere (including

cartoonists whose work appeared in the humor magazines of the day) were

experimenting with Futurism's streamlined forms and startling patterns. And

Sterrett's mature style began to emerge in the last half of the twenties.

Clearly, some of the "abstract art value" that Waugh saw in

Sterrett's style is a Futuristic value, an indirect manifestation of Cubism.

But

there is another manifestation of modern abstract art in Sterrett's strip. If

the anatomy of his characters and the patterns and textures of their wardrobes

and surroundings are Futuristic, the shape of the "sets" in Polly is Surreal. Surrealism is another of the avant garde movements in modern art

that cropped up in Europe in the third and fourth decades of this century. It,

too, had a socio-political stance—opposition to the prevailing bourgeois view

of life. That, however, scarcely attracted Sterrett, whose strip, in making

Paw its protagonist, was at least sympathetic to the traditions of the middle

class if it did not actually uphold them. But the images that Surrealist

painters produced did attract Sterrett.

In

their images, Surrealist painters attempted to evoke a new realism by escaping

from the everyday mundane realities into the realm of a dreamlike or

nightmarish world where memory and the subconscious combined recognizable forms

with fantastic ones. This fusion of the real and the unreal would create a

higher form of realism—super-realism, or surrealism. So much for the theory.

The

most famous of the Surrealists is probably Salvador Dali (even though he

was, in effect, disowned by the most fervent of the fraternity because of his

rampant commercialization of their principles).  In his "The Persistence of Memory"

painting with its barren vista and limp melting watches, we have the very

emblem of Surrealism: a borderland between logic and magic where reality meets

fantasy, a dreamscape where an extreme perspective distorts space and where

seemingly incongruous objects and ideas are grotesquely juxtaposed in order to

appeal to an audience's subconscious feelings and impulses. And in Sterrett's

customary treatment of the settings through which his Futuristic characters

cavort, we see a clear invocation of Surrealistic imagery. In his "The Persistence of Memory"

painting with its barren vista and limp melting watches, we have the very

emblem of Surrealism: a borderland between logic and magic where reality meets

fantasy, a dreamscape where an extreme perspective distorts space and where

seemingly incongruous objects and ideas are grotesquely juxtaposed in order to

appeal to an audience's subconscious feelings and impulses. And in Sterrett's

customary treatment of the settings through which his Futuristic characters

cavort, we see a clear invocation of Surrealistic imagery.

Sterrett

began systematically toying with the realism of his pictures in the early

1920s—at the same time as he began spending summers (April through December) in

Maine in the artists’ colony of Ogunquit, where Sterrett must have encountered

other artists and probably engaged in (or was at least aware of) discussions

about the directions of modern art, including Futurism (in its mechanical

aspects) and Surrealism, both of which were then attaining some notoriety among

the avant garde.

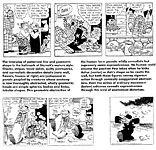

By

the mid-1920s, Sterrett was relentlessly distorting perspective in the Perkins

home and reshaping common household furnishings into fantastical forms. The

Surreal settings are wildly inventive. Polly and her pals walked through

doorways that loomed into towering archways and sat in chairs that sprouted

awnings and other attachments. Throughout the environs, Sterrett scattered a

wild assortment of potted plants with whimsical mushroom-like blooms and fronds

and questing tentacles. And Sterrett used black more extensively than many of

his contemporaries, spotting solids for startling decorative effect throughout

daily installments and creating a cascade of patterns, often at screaming odds

with each other. While the occasional reprinting of a Sunday Polly here

and there over the years has acquainted us with the transcendent eccentricity

of Sterrett's style at its most impressive—that is, when in color—we have

seldom been exposed to the black-and-white version of that style, which is

equally impressive.

But

not every installment of the strip was Surreal. Sterrett abandoned the more

extreme of his Surrealistic renditions when his story required that the reader

comprehend immediately what the setting of the strip is. In a 1927 sequence,

for instance, Paw and company (including Polly) wind up marooned on a desert

isle. And there, the pictures, while still stylized, are far less Surreal than

they were when the action was set in the Perkins home among otherwise mundane

and familiar surroundings.

It

was as if Sterrett hit upon Surrealism as a way of relieving his ennui at

having to draw the same things all the time—the same chairs, the same lamps,

the same doorways, always the same household equipage. And in relieving his

own boredom, he gave his readers a visual treat. But when he had to use his

pictures to tell the story—when he knew the reader could get essential

narrative information only from the visual element in his strip—Sterrett was

careful to make his images more representational, less fantastical and

dreamlike. My guess is that Sterrett's interest in both Futurism and

Surrealism was exclusively an artistic interest not a political or social

interest. He was attracted to graphic productions of these two movements by

the pleasing designs and decorative imagery he found in them. And he

successfully adopted some of the conventions of a few of the Futurist and

Surreal painters by way of giving his comic strip visual variety.

To

label Sterrett's style Futuristic and Surrealistic is to run a risk.

Pigeon-holes have a tendency to become potholes, pitfall prisons, tiny cages of

categories out of which it is nearly impossible to extricate someone once he's

become so incarcerated. I don't mean to do that to Sterrett. We must remember

that Futurism and Surrealism constitute, after all, only aspects of "an

abstract art value" in Sterrett's art. There is more to Sterrett than

Futurism and Surrealism.

If

we return to Becker's aside about the abstract art that would result "if

head, hands, and feet were removed," we discover the rest of Becker's

statement: "But heads, hands, and feet are not removed, and Sterrett's

style is not abstract." Not entirely anyhow. There is more in Polly than abstract art. There are also Edam cheeses, breakfast rolls, and a cat

with wildly ludicrous leg construction. In short, there is high comedy in the

visuals as well as an element of abstract art. And it's the visual comedy that

brings us back to Sterrett again and again. It's the visual comedy that has

earned him a revered place in the history of the medium.

Sterrett's

Surrealism achieved its most flamboyant expression in the Sunday pages of the

late twenties. The pages are a riot of primary colors—rampant reds, succulent

yellows, and pristine blues. And Sterrett heightened the visual impact of his

palette with copious use of solid blacks, which made the colors seem more

brilliant by providing a stark contrast to their hues. Everywhere the

Surrealism of the backgrounds is enhanced by an outrageous patterning of checks

and stripes and other, more manic, geometries and designs. The pages are agog

in exotic potted plants, fanciful embroidered pillows, abstracted cityscapes,

outlandish tubular trees with electric foliage zig-zagging across the sky. And

checkered floors—and walls, and coats and trousers and, so help me, hats. On

one occasion, Paw wears an ensemble the pants of which are checked with a

different color than the coat. Another time he wears a checkered derby.

Some

of the gags, as in George Herriman's Sunday Krazy Kat, seem

dictated by the cartoonist's desire to draw certain subjects in certain ways,

often experimental. One March 1927 page is devoted entirely to midnight scenes

around the Perkins house. We watch Kitty wander through pitch-dark rooms, parts

of which are eerily illuminated by the moonlight streaming in through windows,

creating fantastic patterns and shapes, while we overhear Paw and Maw, provoked

by Polly's sneezing, discussing the state of her health.

When

the family goes to the beach that year (as it does nearly every summer), we are

treated to an entire page in which we see only those portions of the characters

that are underwater while they are wading. Another time, we go with Paw on a

hunting jaunt through the woods—chiefly, I suspect, because Sterrett wanted to

render trees with polka-dot trunks (or striped or flowered).

Some

of the gags are positively vacuous. One Sunday, Maw forces Paw to stay home in

the evening with her instead of going to his poker game. For the whole page,

Paw watches Maw fall asleep in her chair while he and Neewah communicate

silently in gestures and glances a plan for him to escape. In the penultimate

panel, Kitty sneezes and wakes Maw, which effectively cancels the escape plan.

A yawn of a yuk. But the treat of the page (and the comedy) is in the

drawing—in Paw's expressions and his wildly abstracted body language.

This

kind of hilarity is Sterrett's forte. We watch Paw's mounting frustration as

he struggles with one bandaged hand to wash the other. Or his antics trying to

swallow a pill by drinking water from a water fountain. Or his inventiveness

in finding a way to avoid the pain of lying down with a sunburn all over his

body.

On

Sunday pages, Sterrett often demonstrated his sure touch with pantomime. On

one page, Paw marches in Futuristic ranks with dozens of tuxedo-clad

opera-goers, up and down hill-and-dale stairs, to get Polly a glass of

water—which, at the last moment, he spills. On another page, we see what Paw

sees when he inadvertently puts on Maw's spectacles instead of his

own—distortion of everything, a Surrealist's dream. And another time, Paw goes

on a fox hunt and wordlessly restores the pursued fox to its family, and we

witness the joyous reunion.

Sterrett's

graphic style has always overshadowed every other aspect of the strip. And

that is entirely appropriate: the satire of his social and domestic humor,

however insightfully constructed through the prism of Paw's discontent, is

whimsical and felicitous but not as impressive as his pictures. Still, his

approach to humor, while not notable, is not negligible either. Mostly,

Sterrett confined himself to the domestic scene, but occasionally, he left the

Perkins house to  explore other venues of contemporary living. Virtually every

summer, the family made a trip to the seaside. One summer in the thirties,

they went to a farm.In 1927, as I mentioned, we find Paw and Maw and Polly and Kitty and

the whole entourage stranded on that desert isle, far from the usual domestic

context of Sterrett's comedy. explore other venues of contemporary living. Virtually every

summer, the family made a trip to the seaside. One summer in the thirties,

they went to a farm.In 1927, as I mentioned, we find Paw and Maw and Polly and Kitty and

the whole entourage stranded on that desert isle, far from the usual domestic

context of Sterrett's comedy.

The

desert island sequence is scarcely typical Sterrett fare: it is a continuing

story, suspensefully told. While the antics of his cast are comic and the

daily installments often end with punchlines, there is also a good measure of

the kind of suspense we usually find in an adventure continuity, and Sterrett

proves adept at manipulating our engagement by providing a generous helping of

cliff-hanger endings that are both humorous and tantalizing (somewhat in the

manner of Al Capp in Li'l Abner).

|

|

Suspense

of this sort is nearly impossible to achieve without establishing an aura of

danger, and Sterrett does that, too. And more. He puts his cast through some

unaccustomed paces. In meeting the risks of day-to-day living on the island,

most of his characters—Ashur, Neewah, Maw, and most particularly Paw—have their

moments of personal heroism. All except Polly. Polly remains throughout a

caricature of the pretty girl—a sort of icon, a wall flower, a mere decoration,

as much a prop in the surreal landscape here as the potted plants are in the

Perkins home, her face forever frozen in its "pretty girl" grimace.

As

Sterrett's style matured into the 1930s, it became somewhat less inventive.

Surrealistic elements disappeared, leaving the geometric forms of Futurism, and

these became the conventions of the strip and wholly predictable.

Understandably predictable. Having initiated a novel and unique way of

rendering a comic strip, Sterrett had little choice but to imitate himself,

which he did, repeating again and again the graphic maneuvers he had introduced

until they became the familiar devices of his treatment.

Polly during the 1930s was less surprising graphically, but I like this period as

well as the more brilliantly innovative 1920s. In the thirties, Sterrett's

line seems bolder; his sense of design in the use of solid blacks and textures,

surer. He seems more confident of his art. (And, of course, he was: he was

repeating designs he had used before, and with repetition comes confidence.)

Here

we find the daily strip in the last of its glorious heydays. Polly is

more richly textured with cross-hatching and shading in the thirties than in

the twenties: the strip is a crazy-quilt cacophony of patterns and textures.

And of visual comedy. Like other supreme masters of the medium, Sterrett drew

funny. His Futuristic abstractions, his Surreal furniture—these were comic

images not philosophical ones. His characters, pop-eyed and cross-eyed

simultaneously, move through the strip by making ambulatory gestures rather

than by actually walking, one foot after the other; they lean over backwards,

trucking along by advancing one foot ahead of them, the other trailing behind

as if being dragged behind by the lead foot. And when they sit down, their

knees come up to their chins, and they are perfect comic abstractions of homo

sapiens seated; and sometimes, when they sit in overstuffed chairs whose arms

are curved, their knees and the chair's arms form a series of perfectly

parallel humps.

And

then there's the omnipresent Kitty. Kitty is Sterrett's Greek chorus: she

stalks Paw in virtually every panel, her posture mimicking his, thereby echoing

his every mood. And when she breaks cadence, the dissonance is a comic comment

on whatever Paw is doing (or is being done to him).

Polly,

meanwhile, appears no more frequently than before (which was not very often, in

case I've failed to mention it). And her every appearance is a static pose:

seated, she displays her porcelain profile with pouting lips, a rounded

shoulder and daintily arched wrist, and lots of leg. Polly had legs that went

on forever—from the knee to the ankle, that is. She is almost always depicted

sitting down because all the other characters are so squat that she'd tower

over them if standing; and when seated, her legs are bent demurely to one side,

knees together, in the classic chaste girl pose..

As

before, the daily strips usually pursue a single theme for a week or so at a

time. And the themes are usually quite mundane, scarcely earth-shaking. One

year at Thanksgiving, for instance, we find Paw preoccupied by the goose he has

purchased for the feast. A live bird, the goose soon wins Paw's affection over

the few days it is around before the holiday, and thus it avoids the dinner

platter.

Next,

the Perkins family faces Christmas. Sterrett always did a special Christmas

sequence, and the inventiveness of his treatments are a joy to witness. Santa

Claus usually makes an appearance, and marvelous things result. In 1933, Santa

turned the entire cast into Christmas toys for the season: everyone had

doweling for arms and legs, wooden balls for heads. (The sequence is virtually

prototypical of the graphic treatment of the strip itself in the 1940s.)

|

|

In

1931, the Yuletide predicament is how to find a present for Paw, who is one of

those souls who have everything. Polly and Maw solve the problem by throwing

out all his slippers, pipes, bathrobes, etc., so there will be something they

can get for him. Then a New Year's resolution leads to Paw crusading against

the brat Gertrude, followed by a search for a suitable governess for the

child. Later everyone gets spring fever for a couple weeks, then Ashur gets a

kangaroo to train as a boxer, after which, new neighbors move in next door and

baffle the Perkins with their behavior. And so on and on.

By

the 1930s, Sterrett was assaulting Paw less and less with the idiocies of the

Modern Age; indeed, the notion of "the Modern Age" was fading by

then. But Paw is still the thematic center of the strip: Polly is now

entirely a family situation comedy with Paw the archetypal pater familias, forever put upon by his numerous relatives, forever astonished by their foibles

and foolishnesses. The humor now arises from Sterrett's systematic deflation

of pomposity and arrogance. He ridiculed personages with these character flaws

by placing them in circumstances in which they come face-to-face with their own

shortcomings—a maneuver that reveals with comic effect just how far short they

fall of their good opinions of themselves.

Sterrett

was a master of pantomime, particularly, as I said, in the Sunday strips, but

he mined the verbal as well as the visual for humorous nuggets. He delighted

in the comedy that occurs when stupid people misinterpret common expressions by

taking them to mean literally what they say, but his sense of word-play

included all kinds of verbal gymnastics.

Ashur

hesitates to marry because he's afraid of failure. There ought to be a law, he

says, to make marriages "fool-proof." Paw, overhearing this,

disagrees: "What we needs is a law t'make fools marriage-proof."

Later,

Paw gets into a game of one-upsmanship with his neighbor over the scarecrows

they have in their gardens. Maw tells Paw that their scarecrow looks shabbier

than the neighbor's, so Paw hangs a tuxedo and a top hat on the scarecrow

frame, saying, "Let's see 'im 'top' that."

On

a summer voyage, Neewah gets seasick, and Paw tries to comfort him by saying

he'll soon get his sea-legs. "Too late, honorable Pa," says Neewah,

"—of what use are limbs to a man without a stummick?"

By

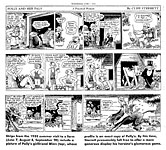

the 1940s, Polly is thoroughly stylized graphically into an endless

reprise of itself. It is still a pleasure to behold, though– with its daringly

abstract interpretations of human anatomy and its bold design quality. By

then, however, much of the work in Polly was no longer Sterrett's.

Plagued by rheumatism, he was forced to give up the daily strip. Paul Fung

took it over on March 9, 1935, after which the dailies appeared without

signature: Sterrett refused to sign work he didn't actually do. But his

signature continued appearing on the decorative Sunday strip until it ended

June 15, 1958.

Whether

in the Surreal twenties or the Depression thirties, Polly always had

about it a wholesome homespun quality just a little musty with resonances of a

by-gone age. But if the ambiance of the strip was somewhat dated in this

fashion, it is not a fault that interfered with its sense of humor. Given the

time-warped setting, Sterrett was as comfortable in the thirties as he had been

in the two preceding decades, and the tics and tropes of his idiosyncratic cast

are as amusing today as they must have been then. But the real entertainment

in Sterrett's strip is found in the cartoonist's unique and highly comedic

stylistic graphic interpretation of the human form and its environment.

Sources. Polly and Her

Pals (the first year)

by Cliff Sterrett (Hyperion Press, 1977); The Complete Color Polly and Her

Pals, Vols. 1 and 2 (1926-1929; Remco Worldservice Books, 1990 and 1991); Polly

and Her Pals (1931 dailies; Arcadia Publications, 1990); 5 issues of Polly

and Her Pals comic book (1927 dailies; Eternity Comics, October 1990 -

January 1991); Polly and Her Pals (1933 dailies, IDW, 2013); Comics

and Their Creators by Martin Sheridan (1944; rpt. Luna Press, 1971);

Coulton Waugh’s The Comics (Macmillan, 1947); Comic Art in America by

Stephen Becker (Simon and Schuster, 1959); plus Modern Art in the Making by

Bernard S. Meyers (McGraw-Hill, 1950); Art of the Western World by Bruce

Cole and Adelheid Gealt (Simon and Schuster, 1989); and Art: The Twentieth

Century by Flaminio Gukaldoni (Skira, 2008).

Return to Harv's Hindsights |