FATHERHOOD

AND THE OFFSPRING THEREOF

Frederick

Burr Opper and Happy Hooligan

We are reminded, by NBM’s publication lately of Frederick Burr Opper’s Happy Hooligan (112 8x11-inch pages in color; hardcover, $24.95), of Opper’s sundry historic achievements in cartooning. Opper was in many respects the greatest cartoonist of his generation, the only one to achieve success in all three forms of the art being practiced during his lifetime: magazine panel cartoon, editorial cartoon, and comic strip. It is in the latter that Happy Hooligan looms prominently. Opper’s strip was the first to deploy all of the medium’s basic ingredients from its very birth.

Plainly, the ingredients of the newspaper comic strip were accruing in various places and under various hands during the last decade of the 19th century. In his watershed 1947 tome, The Comics, the venerable Coulton Waugh, looking back on this period with the benefit of mid-twentieth century hindsight, defined comics in terms of their mature form. Comics, he said, embrace three elements: (1) a narrative sequence of pictures (2) in which speech balloons are included in the drawings, the combination showcasing (3) a character or characters who reappear with each publication of the feature. As I’ve said before in other places, this last quality seems to me to be somewhat trumped up: the first two aspects of the medium are rooted in its form; the third refers to content. Clearly, a narrative sequence of pictures in which the characters speak through balloons is a comic strip whether or not the characters appear again and again. The character qualification was undoubtedly tacked on in order to eliminate all the predecessors to the Yellow Kid, with whom Waugh begins his history of comics, effectively consigning all earlier manifestations of the medium to prototypical limbo.

Waugh allows that the defining combination did not appear all at once but accumulated through the efforts of three individuals during the 1890s. First came continuing characters: James Swinnerton in San Francisco with his little bears in late 1893, early 1894; Richard Outcault in New York with the Yellow Kid in 1895.

Calling Swinnerton’s little bears “continuing characters” is a stretch. Swinnerton introduced a small bear, subsequently named "Baby Monarch,” to evoke the California state symbol, the grizzly bear, Baby Monarch being a visual device by which William Randolph Hearst’s San Francisco Examiner promoted interest in the Midwinter Exposition that opened in San Francisco in January 1984. Reader interest in the little bear prompted Hearst to direct the cartoonist to do several funny pictures of the bear to scatter throughout each edition of the paper. When the Exposition closed, the bear began appearing regularly in the "weather ears" at the top of the front page: in a box reporting temperatures and a forecast, the bear would carry an umbrella if rain were forthcoming or would be sunning himself on the beach. I suppose that’s a continuing character, but it doesn’t appear in a comic strip or, even, a single panel cartoon.

Outcault’s Yellow Kid first appeared in the New York World in a succession of large single drawings that recorded the perverse doings of some slum kids in “Hogan’s Alley.” The Yellow Kid was at least in a “comic.” Outcault was the first to employ a narrative sequence of pictures according to Waugh, but this is another of the instances of his being mistaken. "Strips" of narrative pictures had appeared in numerous forums well before Outcault's tenure at Joseph Pulitzer’s World. In the weekly humor magazines, cartoonists resorted with some frequency to comic sequences rather than single panels. Often these strips were pantomime. In any case, Outcault used the multiple-panel format only occasionally.

Reportedly, Rudolph Dirks was the first to use multi-panel strips regularly in his Katzenjammer Kids, which began December 12, 1897. Subsequently, after a decent interval, Dirks also made speech balloons a fundamental aspect of the form (although they had been employed by Outcault, too—and by other cartoonists as far back as the 18th century in Thomas Rowlandson's cartoon spoofs of British society).

By the turn of the century, the form as defined by Waugh had taken shape. The Sunday comics in color were a reality. Narrative sequences of pictures with speech balloons giving "visual voice" to the characters, the funnies in newspapers had assimilated facets of cartooning in other media and had emerged in a form now distinctly different from that of their brethren in humor magazines. The three founders of the form all eventually drew their comics in sequential panels with the characters blurting out what they had to say in puffs of dialogue. But the first cartoonist to begin drawing a comic strip in its definitive form was Opper. And in the NBM volume at hand, the second in the series, Forever Nuts: Classic Screwball Strips, we have a healthy sampling from the first 13 years of the strip’s 32-year run.

Comic strip researcher Allan Holtz supplies the book’s introduction, tracing Opper’s multi-faceted cartooning career from a surprising dearth of sources. Contemplating his diminutive pile of research material, Holtz suddenly realized that “hardly a word” was written about Fred Opper’s personality. Opper’s life story, compared to such colorful characters as Swinnerton and Bud Fisher and George McManus and Winsor McCay, “is little more than a set of statistics, a sequence of career milestones that took him to the summit of his profession but makes him as remote to us as some ancient Egyptian pharaoh.”

In a September 1922 issue of Circulation, a vintage King Features promotional publication, I found Winsor McCay making up for the deficiency with a glimpse of Opper in an article by Penelope Clarke. McCay asked her if she’d ever met Opper, and when she said she hadn’t, McCay said: “Then I’ll tell you what he’s like. In the first place he is just as sweet and kind and gentle-natured as anyone could possibly be, and he is full of fun and genuine wit, but if he were to come into this room now, you would probably say, ‘Ah, here is the owner of the building, who has come into the city for the purpose of collecting the rent. He now has it in his hip pocket, but before taking it to the bank he is going through the building to see if any reporters or artists have been driving nails into the walls.’ He isn’t that way at all, you know,” continued McCay, “and after you know him you will realize he isn’t, but that would be your first impression.”

Clarke, who, after meeting Opper, confirms McCay’s good opinion of the gentle humorist, adds her own perceptions to McCay’s description: “If you want to now what Mr. Opper looks like, visualize a man who certainly must be more but who appears to be about fifty years of age, a blonde, hair growing thin, blue eyes, a face that is wreathed in smiles upon very slight provocation and upon which there are no disfiguring lines of bad temper or unkindliness, a generous mouth and well-balanced features, a little bit undersized in stature, weight about 140 pounds and with a rapid movement of the body which comes from agility, and nimbleness of brain, rather than from nervousness.”

Without the dubious insights offered in a blatantly promotional publication, Holtz overcomes his disadvantage by telling us something about Opper’s life and career, emphasizing, as I have later on, the cartoonist’s formal pacesetting in Happy Hooligan.

Born in 1857 in Madison, Ohio, Opper quit school at the age of fourteen to work in the village store; after a few months, he found work as a printer's devil for the local weekly newspaper. While there, he learned to set type. Always drawing "comical sketches," he decided about a year later to go to New York where several of the comic weeklies were published. I found Opper recounting the experience in Orison Sweet Marden's Little Visits with Great Americans: "My self-esteem was not so great as to rate myself a full-fledged artist. My idea was to obtain a position a compositor in New York, to draw between times, and gradually to land myself where my hopes all centered." Unhappily, he discovered that to be a compositor, he would have to apprentice himself for three years. So he found a job making window cards and other advertisements for a store.

"All the leisure I had to myself," he continued, "evenings and holidays, I spent making comic sketches, and I took them to the comic papers—to the Phunny Phellow and Wild Oats. I just submitted rough sketches. Soon the editors permitted me to draw the [final] sketches also, which was a great encouragement." We assume from this that until he’d won his editors’ permission, his cartoons were inked by someone else.

After eight or ten months of this, Opper was able to make a living cartooning, and he left the store to submit cartoons and drawings to Wild Oats, Harper's Weekly, Frank Leslie's, and Century among others. In 1877, after about five years as a freelancer, he joined Leslie's as a staff artist on salary, and three years later, he left for Puck, which had been launched in 1877 by Joseph Keppler, “a disaffected Leslie’s cartoonist.” At Puck, Opper, apprenticing to Keppler and the magazine’s other cartoonist, James Wales, did both political cartoons and humorous ones. In his off hours, he also illustrated several books, among them, in 1884, humorist Bill Nye's Baled Hay, subtitled A Drier Book than Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, leading to similar assignments in other Nye tomes, including 1894's Comic History of the U.S. Deploying more realistic drawings, Opper also illustrated one of Marietta Holley’s satirical Samantha novels, Samantha at Saratoga, Or Racing after Fashion (1887).

As the Gay Nineties became somewhat more somber, Holtz tells us, Opper began to look to newspapers’ color Sunday funnies as a new and perhaps more viable opportunity, and in 1899, he left Puck and signed with the Hearst works after a short interlude moonlighting for the New York Herald. At Hearst’s Evening Journal, Opper was soon drawing political cartoons “vicious in their assaults,” saith Ben Procter in his Hearst biography, William Randolph Hearst: The Early Years, “linking ‘coal barons’ and ‘criminal trusts’ with Republican candidates.” To make his attacks all the more devastating, Opper invented an enduring symbol to stand for those of us who are forever victimized by coal barons and criminal trusts.

The great political cartoonist Thomas Nast invented the Republican elephant and Santa Claus, but Opper invented Mr. Common Man—"a foolish, cowed, insignificant and contemptible pygmy" according to a contemporary account. Later, the figure would be christened John Public, and the old Chicago Daily News’ Vaughn Shoemaker would give the enduring tax-paying dupe a middle initial, Q.

But the ever-suffering common man was not the only character that debuted in Opper’s political cartoons. “One of his most popular and influential daily series [of editoons],” Holtz reports, castigated the Republican party’s alliance with the moneyed classes and the combines of business interests called “the trusts.” (As you can see, the GOP has not changed its allegiance much in the ensuing century.) This relationship Opper portrayed by creating a cast of real and emblematic characters: President William McKinley and his vice president Teddy Roosevelt were the real personages, appearing in stinging caricature as small mischievous and sometimes willful boys; the symbolic characters were “the trusts,” who was cast as the father of the two boys, and their nursemaid, Mark Hanna, the millionaire who financed the Grand Old Pachyderm; he appeared in drag. The series was entitled Willie and His Papa and was so popular, as Holtz notes, that it was collected in a hardcover book, Willie and His Papa and the Rest of the Family, published by Grosset & Dunlap in 1901.

|

|

The book probably produced more Opper fans than the cartoons themselves had in their initial publication in the Hearst newspapers. A couple years ago after a friendly altercation with another comics chronicler about the syndicated sources of fame, I went right home and questioned the reach of the Hearst chain and syndication. My contention was that Jay N. “Ding” Darling of the Des Moines Register was the first widely syndicated editorial cartoonist; my amicable adversary contended that Opper, because he appeared chain-wide in the Hearst newspapers, would have been the first. Neither of us, strictly speaking, was correct.

First, at the time Opper started being distributed “chain-wide” to the Hearst papers, Hearst had only three papers: San Francisco Examiner, New York Journal, and the Chicago Herald-American. So Opper’s national circulation was relatively small compared to what it became once the Hearst syndication operation got going. Hearst’s International News Service, a wire service, distributed mostly text features from 1906 to 1909; but the distribution of comics doubtless began progressing to its apotheosis when, in 1913, Moses Koenigsberg started the Newspaper Feature Service, eventually christened King Features in honor of its founder (Koenigsberg, “King-town”) in 1914.

Second, Opper wasn’t the first editoonist in the Hearst firmament: the first was Homer Davenport, who, after an apprenticeships in Portland, Oregon, gravitated to the San Francisco Examiner in 1891, then to the Chicago Daily Herald in 1893 before Hearst enticed him to New York in 1895. Davenport, then, was the first editorial cartoonist to benefit from chain-wide distribution even though the chain had only two links at the time—one in San Francisco and the other in New York.

Ding, who started us on this digression, was syndicated by the Herald Tribune, starting in 1916. By then, the Hearst chain had grown to seven papers; and by then, King Features was underway, too. At the time Ding’s national syndication began in earnest, then, he would have been accompanied by both Opper and Davenport. So maybe he wasn’t the first widely syndicated editoonist, but, since he persisted on living in Des Moines and in producing daily cartoons for the Des Moines Register, which then supplied the inventory from which the Herald Tribune plucked cartoons for syndication, Ding may be counted among the first widely syndicated editorial cartoonists whose berth was not at the font of his syndicate. Later, however, starting in 1926, Ding was distributed by his newspaper’s syndicate. All of which is beside the point, fascinating though it may be. Back to Opper.

Opper also drew cartoons in other departments of the paper, and in early 1900, he began producing his longest-lasting creation, Happy Hooligan, a Sunday comic strip about a pathetic but ludicrous Irish hobo with a tin can for a hat, who could be relied upon to lose at every opportunity. (The earliest Happy Hooligan I've seen is a half-page comic strip, with speech balloons, dated January 28, 1900, in the collection of Gordon Campbell. At least, that’s what I thought I saw, and I wrote the date on a notepad I was carrying with me when I visited Campbell. Later, however, I wasn’t quite sure what the date applied to and phoned Campbell, asking him Happy’s starting date. “March 11, 1900,” he said without hesitation, invoking the traditional debut date. Because he didn’t double-check, I can’t be sure about the January date and must, therefore, resort to custom. In his earliest manifestations, incidentally, Happy was much more realistically rendered than in the samples in this vicinity. His dented tin-can hat seemed almost a fez.)

Opper created many cartoon features thereafter, including And Her Name Was Maud! about a trouble-making mule, and Alphonse and Gaston, whose title characters were so excessively polite as to inaugurate a national catch-phrase. (“After you, my dear Alphonse”; “No, after you, my dear Gaston,”quoth the duo in an alternating chorus as they bowed and scraped to each other in exaggerated deference.) Many of Opper’s creations of this period were one-shots: in common with other newspaper cartoonists of the day, Opper produced a variety of cartoon features, some on Sundays only, some on other days of the week, sometimes several days in succession. Some of the titles would surface for a day or so and then disappear, and some of them came back again, off and on, for a period of weeks or months. For a time in 1904, three of Opper’s Sunday creations were running simultaneously—Happy, Maud, and Alphonse and Gaston—and sometimes Opper put them all together in a single Sunday page. Of the miscellaneous lot, Happy lasted by far the longest, ending in 1932, when Opper was forced by failing eyesight to lay down his pen; he died five years later.

Opper

apparently kept up his prodigious performance at Hearst until the

1920s, when he “cut back,” as Holtz puts it, to the

Sunday Happy page and

three editoons a week. Early in this stupendous run, he also

illustrated humorous books, among them D.

Dinjkelspiel: His Conversations by George V.

Hobart in 1900 and, also in 1900, Mr. Dooley’s

Philosophy by FPD in which actual political

figures appeared in caricature, a few of which can be discerned in

the sample now at our elbow.

Legend has it that Opper was the first president of the Cartoonists Club that started in the late 1920s. He was also, according to Koenigsberg, the last president of the group. While all the members could agree that Opper's age, tenure and professional stature entitled him to the honor, they could not agree on a successor. Said Koenigsberg (in King News): "[The society] crashed into as many fragments as there were members. Each was of the unalterable conviction that he merited the chieftaincy."

I’m not persuaded that Koenigsberg has his facts right in this scrap of legend. There was another cartoonists organization formed in the early 1920s in connection with Cartoons magazine. It’s president was Eugene “Zim” Zimmerman, celebrated for his cartoons in Judge humor magazine, and this club, like the one Koenigsberg references, also collapsed for lack of a successor when Zim stepped down. Could be Koenigsberg has confused Opper with Zim, or vice versa. Nice mythology, though.

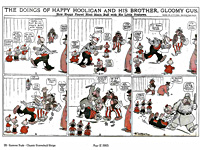

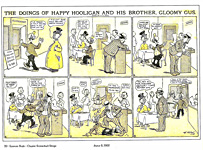

The comedic flywheel of Happy Hooligan is starkly simple: Happy, an incurably non-calculating good-hearted soul, tries to lend a helping hand in some innocuous enterprise he encounters—retrieving someone’s errant hat, say, or rescuing a cat or delivering a message—and his action misfires in some minor way that promptly escalates to catastrophe, which, in turn, leads to retribution by the personages whom he initially set out to help. Typically, they pounce on the hapless Happy and beat him up. Or his bumbling attracts the attention of nearby officers of the law, who, before too many of these Sunday disasters, would spot their trouble-prone victim and his ne’er-do-well relatives from afar and yell, “It’s the Holligans!” and descend upon the miscreants waving nightsticks.

Penelope Clarke asked Opper if Happy had been a success from the start, and Opper said: “No—he dragged frightfully at first. I thought at one time we would have to drop him.”

“Do you know what made him popular?” persisted Clarke.

“Yes, I do,” said Opper. “He became popular because of something that will make anyone popular. At first he was simply Happy Hooligan, just as you see him, but he only got into trouble and that was all. Then he began trying to help others and got into trouble because of that. That made him. Just trying to help others. He is awkward and ugly and illiterate, but he tries to help.”

The strip’s charm, if that’s the word, arose from the variety of ways Happy would be brutalized by his betters in the last two panels of the strip, the sheer unrelenting unfairness of it all—and in the ingenuity of Opper’s traps for his character: what new good deed will Happy attempt that will go awry enough to precipitate a cascade of calamity, culminating in the tramp’s being clobbered or clapped in jail? Like many early comic strips, Happy Hooligan was essentially a one-note joke: Opper repeated his formula—no good deed going unpunished—endlessly, or at least for over three decades.

Fellow cartoonist Richard Outcault, writing in the July 1926 issue of Circulation, delivered what he called “a tribute” to his colleague, “my friend Opper, ‘the dean of American caricaturists,’ saying: “The kind of humor Opper gets into his drawings tickles a certain joint in my risibility that forces a good honest laugh. Some comics create in us a gratifying smile on our insides; some please us on account of their ingenuity and good draftsmanship, but Opper’s method of expression is purely an appeal to our sense of the ridiculous. ... Humor is sanity; laughter is sanitary,” Outcault finishes, “—Mr. Opper has done his share as a grouch destroyer.”

Since Circulation’s function in the world of print journalism was to promote the sale of such features as Happy Hooligan, we expect to find little in the publication of profound analysis, and the fodder Outcault offers here is standard fare. But he inches up to a profundity when he observes that although Happy gets beaten up regularly, he just as regularly shows up the next week, eager to perform some little act of benevolence. Outcault continues: “Happy is a hog for punishment. If all the black eyes Hooligan has had were looking Opper in the face, they would frighten him to death except for one thing: there never was a look of resentment in any of those black eyes.”

The crude physicality of the strip’s ritual doubtless appealed to readers in big cities in the first couple decades of the century: many of them were newly arrived from other countries and were illiterate in English, but they could enjoy the visual mayhem taking place over Opper’s signature without being able to read a single syllable. (I don’t mean to slight foreign-language speakers: English-speaking movie-goers a few decades later doted on the same sort of physical humor in the raucous films of the Three Stooges. We didn’t progress much in the first forty years of the 20th Century.) With Opper’s comedic treatment of a mounting disaster for Happy every week, we may have stumbled on another aspect of the strip’s initial appeal: immigrants—and at the turn of the century and until the 1920s, most Americans were immigrants or their parents had been immigrants—often had a hard time: they were often beaten down by the “land of opportunity.” And maybe they saw themselves in Happy Hooligan, who, despite being beaten down again and again, always came back, happy and willing to do yet another good deed. Resilience. They saw in Happy a role model, an inspiration.

Opper insinuated into the strip what variation he could manage fairly early by introducing other cast members. As comics chronicler and collector Cole Johnson observes in the NBM book’s epilogue, after a couple years, Opper gave Happy a brother, Gloomy Gus. Writes Johnson: “Gus was the grumpy counterpoint to his brother’s sunny personality. When the idiotically optimistic Happy tried to help out or do a good deed, Gloomy would pessimistically tell him not to get involved. Sure enough, Happy would wind up in bad trouble, not to mention the cop’s clutches. The unfairness would now be doubled with Gloomy Gus somehow winding up with some reward at the end.”

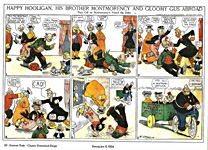

Later still, Opper added another Hooligan brother, Montmorency, “who somehow had an English accent, sported a monocle, and dressed as a ragged version of a duke.” Happy also acquired three look-alike nephews who fragmented their utterances into successive syntax like Carl Barks’ Huey, Dewey, and Louie. Eventually, Opper widened his stage even further by sending the Hooligans abroad for misadventures in distant climes for long stretches of continuity and by letting Happy find different kinds of employment—becoming a vaudeville extra, a circus roustabout, seeking the North Pole, fighting a duel with a count, being a guard at an insane asylum, going to China. In every circumstance, Happy, without fail, screws up and is admonished brutally. He was not so much the original Born Loser as he was the Beaten Loser, as we can readily see in the samples posted in our Gallery below.

Opper employed the comic strip form pretty much as he found it, simply putting all the pieces together. And he found it in the colored Sunday supplement. The next step in the evolution of the medium would result in establishing the daily "strip" format. And that was achieved by Harry Conway "Bud" Fisher in 1907, but that, as they say, is another story, one we told here in November 2007 by way of celebrating the centennial of the daily newspaper comic strip. And now, the Happy Gallery.

|

|

|

|

An earlier, shorter, version of this tirade appeared in The Comics Journal, No. 297, in the spring of 2009, albeit without as many pictures.