November

2007: Celebrating the Centennial of the Daily Newspaper Comic Strip

Mutt, Jeff

and Their Precursing Creator, Bud Fisher

One hundred years ago this month, the daily comic

strip was inaugurated in a

Mutt and Jeff attests to

the visual power of the comic strip. The

eponymous duo long ago ascended to the pantheon of American mythology: in common parlance, the names, seemingly

forever linked, always denote a visually mismatched pair, a tall person and a

short one. But as a comic strip, Mutt and Jeff enjoys another

distinction: it established the

appearance of the medium, its daily format.

Other

cartoonists (Clare Briggs, George

Herriman) may have strung their comic pictures together in single file

across a newspaper page before Mutt and

Jeff debuted on

Until Mutt and Jeff set the fashion,

newspaper cartoons usually reached readers in one of two forms: on Sunday, in colored pages of tiered panels

in sequence (some, like Winsor McCay's Little

Nemo in Slumberland, intended chiefly for children to read); on weekdays,

collections of comic drawings grouped almost haphazardly within the ruled

border of a large single-frame panel (directed mostly to adult readers). The daily cartoons were often found in a

paper's sports section and featured graphic reportage and comic commentary on

the doings of diamond, ring, track, and other arenas of athletic

competition. Harry Conway "Bud" Fisher was a sports

cartoonist on the San Francisco Chronicle,

and so, not surprisingly, the comic strip he launched that became Mutt and Jeff focussed on a

preoccupation of the sporting crowd—namely, betting.

Some

accounts of the cartoonist’s life report that Fisher was born in Chicago on

April 3, 1884 (or 1885; sources differ), but in a 1915 news release prepared by

Wheeler Syndicate, Fisher is quoted as saying he was born in San Francisco,

April 3, 1885 —“but I didn’t stay there long. We moved about rather rapidly on

account of my father’s business. My mother and father lived in

By

1928, Fisher had changed his story. In a four-part article, “Confessions of a Cartoonist,”

published weekly in The Saturday Evening Post (beginning July

28), he says he was born in a suburb of

Bud

had no luck at first in finding a newspaper job in

Soon

after arriving at the Chronicle, he,

like most early cartoonists, was assigned to the sports department, where, for

the next couple years, he did layouts and occasionally drew pictures

celebrating in humorous imagery what proper society then regarded with

disdain—the dubious prowess and feats of professional athletes, their trainers,

managers, promoters, and hangers-on and other alleged riffraff. Fisher also

occasionally did pictorial reportage for other departments of the paper. Once

he was sent to interview Enrico Caruso, when the opera star came to town.

Caruso was well known as an amateur cartoonist as well as a celebrated tenor.

“He was great,” Fisher said, “and made a picture of me while I sketched him.”

A

short time later, on

Structures

that didn’t fall down burned. The city-wide conflagration was more impressive

than the earthquake: for years afterward, surviving locals referred to the

Fisher

scarcely imagined that he was establishing an art form. “In selecting the strip

form for the picture,” he wrote in “Confessions,” “I thought I would get a

prominent position across the top of the sporting page, which I did, and that

pleased my vanity. I also thought the cartoon would be easy to read in this

form. It was.” But Fisher’s editor had been a reluctant participant in the

experiment. Two years earlier, Young had turned down Fisher’s suggestion for a

similar “strip” because, he is alleged (by Fisher) to have said, “it would take

up too much room, and readers are used to reading down the page and not

horizontally.”

By

way of introducing and describing his cast, Fisher called his strip A. Mutt. "Mutt" was short for "muttonhead"—a fool (Eric

Partridge in Slang Today and Yesterday even credits Fisher with inventing the clipped version of the term). And Augustus Mutt was indeed something of a

fool: he was a compulsive horse-player,

a "plunger." And at first the

strip concentrated almost exclusively on his daily quest for the right horse to

bet on and for the wherewithal to place the wager. We saw Mutt's wife every once in a while—and

his young son, Cicero. But no Jeff. Jeff didn't come along until later.

In

those days before national syndication, a cartoonist drew only for his own

paper, and he generally drew a cartoon just the day before it would be

published. (Syndicates would require

cartoonists to submit their work weeks in advance because it took that much

production time to prepare the material for distribution all around the

country.) The circumstance permitted

extremely topical and local comedy: the

cartoon in today's paper could be based upon the news in yesterday's paper,

often news of city hall or the nearest police precinct house. Or, in the case of sports cartoons, the

playing field or race track. It was a

circumstance Fisher seized upon and exploited. In determining which horse Mutt would bet on in the strip to be

published in, say, Tuesday morning's paper, Fisher picked a real horse that

would be running Tuesday afternoon at the Emeryville track. Fellow racing enthusiasts had to wait for

Wednesday's paper to learn the outcome of Mutt's bet. Mutt lost mostly, but, given the vicissitudes

of wagering, he won every once in a while. And that was often enough. Readers of the strip began to take his wagers seriously, interpreting

them as inside tips. Almost overnight,

they were hooked, and their addiction guaranteed the strip's continued

appearance (not to mention continued sales of the Chronicle at the newsstand). Fisher was on his way to fame as well as fortune.

But

Fisher did more for the comic strip medium than establish its format. According to John Wheeler, founder of the

Wheeler (later Bell) Syndicate (distributor of Mutt and Jeff for most of the strip's run), Fisher, "by his

guts and independence, probably did more to make the cartoon business for his

more cowardly confreres than anyone else who has ever been in it." To begin with, Fisher had the foresight to

copyright A. Mutt in his own

name—and, later, to apply for a trademark on the title. The strip was his and no one else's. And Fisher fought in court to establish his

ownership beyond question.

Fisher

began to benefit from his prescience almost at once. Press baron William Randolph Hearst, seeing

that A. Mutt seemed responsible for

his competition's increase in circulation, did what he would do again and again

over the next half century: he hired the

rival's talent away by paying more. Much

more. Hearst offered a weekly salary of

$45, double Fisher's pay at the Chronicle; and A. Mutt began running in Hearst's San Francisco Examiner within three

weeks of its debut in the other paper. It also continued to run in the Chronicle. In accordance with established practice, A. Mutt was treated as if it were the Chronicle's property: the editors simply hired another cartoonist (Russ Westover, later the creator of Tillie the Toiler) to draw the

strip. But this time, the situation was

different. The canny Fisher had taken

the precaution of copyrighting the strip in his name with its last appearance

in the Chronicle.

In

the first of his “Confessions” articles, Fisher explained that after he had

accepted the Examiner offer but

before he left the Chronicle, he

consulted a lawyer about copyright and learned that “a copyright notice [had

to] be carried when the picture or article to be copyrighted was published and

then the drawings for three successive days had to be filed in the Patent

Office in Washington to complete the copyright.” Fisher had only one day left

at the Chronicle, but he used it:

after his editor had approved his strip for that day, December 10, the

cartoonist went into the engraving room before the strip was processed and

lettered into the last panel: “Copyright, 1907, by H.C. Fisher.” He did the

same on the first two strips published the next week in the Examiner. So when the Chronicle continued publishing the strip without Fisher, he brought

suit, and the paper, once persuaded of the legitimacy of his copyright holding,

dropped its claim. The last of the Westover strips appeared on

Later,

Fisher sued again for his rights to the strip, and this time, the case went to

court. In 1914, hearing that Fisher’s contract with Hearst was coming up for

renewal, Wheeler offered Fisher a better syndication deal than Hearst was

giving him. Hearst was then paying

Fisher $300 a week; Wheeler offered the cartoonist $1,000 a week or 60% of the

revenue, whichever was greater. It was a

staggering sum, but Fisher wasn’t convinced Wheeler could make good on the

offer. Wheeler finally persuaded him by depositing a year’s salary in an escrow

account. Fisher signed a contract in December 1914; his last strip for Hearst

was published

Wheeler’s

offer hadn’t been the first that tempted Fisher away from Hearst. Shortly after

arriving in

“My

friend,” said Fisher, “I don’t know who you are, but if you will guarantee to

fire me and make it stick, I’ll meet you at

Writing

his “Confessions,” Fisher concludes the tale: “I walked away, puffing my

cigarette and left a startled and dignified substitute general manager.

Needless to say, he didn’t fire me. I guess I was pretty fresh in those days.”

Fisher's

fights for his rights as a cartoonist were not confined to the courtroom. And the fighting began early. In his Comic

Art in America, Stephen Becker tells us that while Fisher was still a staff

cartoonist for the Chronicle, the paper

reduced the size allotted to his cartoon without informing him. Fisher calmly tore up his artwork and refused

to draw for the smaller size. In effect,

he quit. But since he was obliged to

give two weeks' notice, he came to the office every day for the next few days.

He did not, however, touch pen or paper. His editor soon relented, and Fisher's cartoon resumed at its usual

dimension.

Fisher

was perfectly constituted for doing battle. According to Rube Goldberg and others who knew him well, Fisher was an inlet of self-assured independence

in a churning sea of whimpering egos. He

was antagonistic and belligerent—a cocky, scrappy, dapper hard-drinking,

carousing denizen of city rooms and saloons. His was the sort of personality that generates legends. For example, there was his habit of using his

apartment as a target range, an incident recounted by Wheeler in his book, I've Got News For You.

While

waiting for his contract with Hearst to expire, Fisher was doing no

strips. To fill his idle hours, he went

with Wheeler on an expedition south of the border to interview Pancho Villa,

the bandit who had somehow become the savior of his country. Villa gave Fisher a six-shooter that he'd

taken from the body of a man whose execution Fisher and Wheeler had been

invited to watch.

Fisher

took the pistol back to

"You're

too damn strict around here," Fisher said. "It is getting so you can't shoot off a pistol in your own place at

four in the morning without someone complaining. I'll move out tomorrow."

"You

bet you will," said the superintendent. And he did.

After

the Mexican adventure, Fisher resumed Mutt

and Jeff, this time for Wheeler, his first strip dated

Fisher quickly habituated himself to enjoying both wealth and

renown. His celebrity made him welcome in circles that were normally closed to

newspapermen and other lowlifes (such as actors and professional athletes, all

of whom were social outcasts for at least the first twenty years of the

century). The first truly famous

cartoonist, Fisher relished his position in high society, and he worked hard on

his public image (tainting the world's perception of cartoonists in the

process). Fisher bought a stable of race

horses, drove about town in a Rolls Royce, and prowled nightclubs with a

beautiful showgirl on each arm. He

married one of them, Pauline Welch—“the prettiest girl I had ever seen in my

life.” The marriage didn’t last (“comic artists do not generally make good husbands,”

Fisher said), but their friendly relationship endured. “It is comforting to

know that in any emergency there is no one I could call upon and be surer of

assistance from than my ex-wife,” Fisher wrote in 1928. Although cartoonist

enjoyed the license of a bachelor life, in 1924 he married again, this time a

titled European whom he met on a voyage home from France, the Countess Aedita

de Beaumont, only to be legally separated four months later (but she inherited

62 percent of his estate, and subsequently, the strip’s copyright notice was in

her name).

Fisher quickly habituated himself to enjoying both wealth and

renown. His celebrity made him welcome in circles that were normally closed to

newspapermen and other lowlifes (such as actors and professional athletes, all

of whom were social outcasts for at least the first twenty years of the

century). The first truly famous

cartoonist, Fisher relished his position in high society, and he worked hard on

his public image (tainting the world's perception of cartoonists in the

process). Fisher bought a stable of race

horses, drove about town in a Rolls Royce, and prowled nightclubs with a

beautiful showgirl on each arm. He

married one of them, Pauline Welch—“the prettiest girl I had ever seen in my

life.” The marriage didn’t last (“comic artists do not generally make good husbands,”

Fisher said), but their friendly relationship endured. “It is comforting to

know that in any emergency there is no one I could call upon and be surer of

assistance from than my ex-wife,” Fisher wrote in 1928. Although cartoonist

enjoyed the license of a bachelor life, in 1924 he married again, this time a

titled European whom he met on a voyage home from France, the Countess Aedita

de Beaumont, only to be legally separated four months later (but she inherited

62 percent of his estate, and subsequently, the strip’s copyright notice was in

her name).

In

April 1917, the United States, until then resolutely neutral about the

hostilities in

When

he showed up at the training camp, Fisher reported, “I knew very little about

what people did before

On

weekends, Fisher took a hotel room in nearby

In

his account of his adventures as a soldier, Fisher somewhat coyly mentions only

that his were “special duties” that “kept me along the Western Front for

several months.” He confesses that he was assigned a “staff car, which gave me

a lot of freedom and an opportunity to visit the American Front—always by way

of

Fisher

says that he saw “considerable fighting,” but it must have been from a

distance. He adds, rather gracefully, “My experience at the Front was colorless

compared with that of other soldiers so I shall not dwell on it.” But he can’t

resist his comedic urge: “One thing that always amazed me was how easy it was

to slip by the front lines. There was no sign to tell you where they were until

you got shot at.”

One

of Fisher’s duties at the censor’s office was draw Mutt and Jeff for American publication. He send his weekly batches

of six daily strips back to the states from

Fisher—and

Mutt and Jeff—served until the end of the War, and Beaverbrook had him created

a “perpetual” second lieutenant in the British army. Runyon lost his bet.

Almost

immediately upon Fisher’s discharge, Wheeler, responding to demand, contracted

with Fisher for a Sunday Mutt and Jeff. “I have never taken so great an interest in the page as in the daily pictures,”

Fisher said. “The Sunday page must necessarily be for children since it is they

who demand the funnies as soon as the newspaper comes into the house while the

strips are intended more for adult readers. I don’t think I have the point of

view of the child since I have never had one myself.” (Note that Fisher refers

to the daily releases as “strips” as distinguished from the Sunday version

which fills an entire “page” of the paper.)

Fisher

had another bias against the Sunday page. In order to allow for making the

color plates and subsequent matts for distribution to syndicate clients, the

Sunday version had to be produced several weeks in advance of publication date.

And Fisher “always contended that it keeps up the standard of the comic to draw

it as near the publication date as possible” in order to base his comedy “as

much as possible” on the news of the day.

By

the twenties, Fisher was enjoying his social life so much that he left most of

the work on the strip to Ed Mack. In

this respect, too, Fisher may have set the mold. For a long time, the average newspaper

reader, who acquired his perception of the world from what he read in his

paper, believed that the famous cartoonists whose escapades were so frequently

related on the front pages spent most of their time lolling around in fancy

nightclubs while their strips were being drawn by underpaid starving teenagers,

who slaved away in secrecy in some obscure garret. In Fisher's case, this perception was

probably close to the truth. (As it was

with another Fisher, Ham, whose Joe

Palooka was drawn by others even if it was written by its creator of

record.)

Bud

Fisher soon became a gambling, womanizing sun-dodger, who seldom handled a pen

anymore. And the more he moved in

society's salons, the less use he had for his erstwhile brethren of the

inky-fingered fraternity. He regularly

snubbed his one-time friends. "He

squandered his life and was a very unhappy man," Wheeler wrote.

Fisher

died in 1954 at the age of 70. His last

years were desolate and lonely. He was

sick and solitary in a huge museum of a

The

strip that made Fisher a wealthy celebrity graduated from pedestrian race-track

touting to classic comedy when the tall and gangling Mutt acquired his

diminutive side-kick: Mutt had

encountered Jeff among the inmates of an insane asylum in late March 1908, but

it wasn't until a year or so later that Fisher brought Jeff back into the strip

as a regular cast member. The skinny

tall man sort of adopted the short fellow, and the historic team was born. By then, the strip was appearing in Hearst's New York American, well on its way to

national distribution. Even before

Jeff's arrival, however, Fisher had pioneered another of the medium's

conventions—narrative that continues from one day to the next.

Fisher

had recognized at once the potential of the daily comic strip for bringing

readers back day after day after day. The central device of A. Mutt virtually forced the cartoonist into day-to-day continuity. Mutt places a bet one day; the outcome is

reported the next day. And Mutt promptly

places another bet. To learn whether

Mutt won or lost, we must buy a paper every day. But Fisher soon began to bait his hook with

other embellishments.

In

early January 1908, Fisher insinuated another storyline into the daily

ritual. Mutt's wife divorces him, and

Mutt begins paying court to another woman. Even in the throes of courtship, however, the plunger makes his daily

dash to the betting window. Despite his

addiction, he wins the lady's hand—only to lose her once and for all when he

deserts her at the altar in order to place a wager on a horse named Lazell

running in the Third Race that day. Subsequently, Mutt’s wife takes him back, telling him that the divorce

had been faked, a tactic she cooked up with a judge to jolt Mutt into

dependable domesticity. The scheme,

clearly, didn't work. They resume their

marriage, Mutt as devoted to the track as ever.

Obviously,

Fisher's strip was aimed at adult readership. Wagering is an adult diversion. And the strip appeared on the sports pages of the paper, a section

reflecting adult preoccupations. Obvious

factors but worth noting. The Sunday

funnies were conceived at least in part as entertainment for children. Not Fisher's strip. At first, he did seven strips a week, one for

Sunday and six for the weekdays. But the

Sunday strip ran in black-and-white on the sports page, not in the colored

comics section. He knew his

audience. And in deliberately appealing

to adult readership, Fisher once again set the pace for the medium. Although in the popular mind, the comics

still remain "kid stuff," they never were directed at youngsters in

the daily format: from the very

beginning, cartoonists wrote and drew their weekday comic "strips"

for adults.

In

yet another way, Fisher may have shaped the medium. This time, less commendably. There is ample evidence to indicate that

Fisher deliberately assumed a rudimentary drawing style for rendering the

adventures of Augustus Mutt. Fisher's

other cartoons for the Chronicle (some

drawn before he started A. Mutt; some

after) display a drawing ability that, while not spectacular, is accomplished,

better than merely adequate.  In fact, some of the pen portraits of Mutt that the strip's

continuity occasioned in 1908 show a command of the nuances of cross-hatching

and shading that is a cut above the skill otherwise revealed in the strip.

In fact, some of the pen portraits of Mutt that the strip's

continuity occasioned in 1908 show a command of the nuances of cross-hatching

and shading that is a cut above the skill otherwise revealed in the strip.

Fisher

apparently believed that cartoons of the sort he was inventing with A. Mutt should be drawn in a crude almost

clumsy manner. I'm not talking about

Mutt's heron-like appearance—his beaky, chinless visage and tall rangy build or

his raw-boned, loose-limbed all-elbows-and-knees mode of locomotion. No, I'm talking about basic anatomy and such

other artistic fundamentals as simple perspective. In giving his protagonist human dimension,

Fisher was apt to change Mutt's proportions from one panel to the next: when he bent his arms and legs, they got

longer. And the characters very often

looked as if they didn't quite fit the surroundings Fisher gave them: chairs and doorways were too small, and

various furnishings tilted wildly to conform to Fisher's idiosyncratic

understanding of perspective.

Fisher

apparently believed that cartoons of the sort he was inventing with A. Mutt should be drawn in a crude almost

clumsy manner. I'm not talking about

Mutt's heron-like appearance—his beaky, chinless visage and tall rangy build or

his raw-boned, loose-limbed all-elbows-and-knees mode of locomotion. No, I'm talking about basic anatomy and such

other artistic fundamentals as simple perspective. In giving his protagonist human dimension,

Fisher was apt to change Mutt's proportions from one panel to the next: when he bent his arms and legs, they got

longer. And the characters very often

looked as if they didn't quite fit the surroundings Fisher gave them: chairs and doorways were too small, and

various furnishings tilted wildly to conform to Fisher's idiosyncratic

understanding of perspective.

To

the extent that A. Mutt provided a

model for others to emulate—and as the roaringly successful first of its kind,

the strip's influence was considerable—Fisher demonstrated the way a comic

strip should be drawn—crudely. His

influence in this regard was not, fortunately, pervasive. Cartoonists like Winsor McCay who had a

towering talent drew in the way their talent dictated and produced art works of

great beauty. Even artists with less

skill were driven mostly by their gifts, and, drawing as well as they could,

they created reasonably accomplished pictures. But Fisher had opened a door, and through that door, many less talented

artists could now pass. More

significantly, Fisher, perhaps unwittingly, gave the reading public the

impression that comic strips should be ineptly rendered. It was an image the medium would carry for

years—decades. Regardless of how popular

comic strips became (and they were very popular indeed from the very

beginning), for much of their early history, comic strips were seen as

sensational, amateurishly drawn appeals to the baser instincts of newspaper

readers. And for that, the vulgarities

of Richard Outcault’s Yellow Kid was partly responsible; and Bud Fisher must

surely shoulder his share of the blame, too.

Speculation

about Fisher's impact upon comic strip graphics and upon the public perception

of the artistic merit of comic strips aside, it's clear that when Fisher

launched A. Mutt, he defined the new

genre almost at birth. A. Mutt presented itself as a

"strip" of pictures, its narrative was continued from day-to-day, and

it was aimed deliberately at an adult audience. At this late date in the study of comic strips (we've been pondering

them seriously at least since about 1970), it may come as a surprise that the

first of the breed burst upon the pages of a San Francisco newspaper with

virtually all of the medium's conventions in place at the very onset. Upon reflection, though, it is not quite so

astonishing. As Samuel Johnson said of

Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels,

"When once you have thought of big men and little men, it is very easy to

do the rest." With newspaper

cartoons, once the decision had been made to format them in "strips"

and run them daily, the rest—continuity from day-to-day, even adult readership—

follows logically. And these elements

were not the last of Fisher's innovations. He continued to play with the medium, and over the next two years, he

explored many facets of the form that others would take up again in later

years.

For

the first two months of his new strip's run, Fisher repeated essentially the

same gag every day, seven days a week. The punchline was Mutt's daily bet, and the last panel in every strip

showed Mutt dashing up to the betting window, knees and elbows a-flap with the

exertion of his desperate haste, a few dollars clenched in his fist. Fisher varied the daily drill in one of two

ways: Mutt's predicament on one day

might be determining which horse to bet on; on another day, his dilemma might

be how to acquire enough money to place a bet.

Mutt

often overhears a phrase in the discourse of passers-by and, taking the phrase

as some sort of omen, he bets on a horse whose name he hears in that

conversational fragment. Mutt's

compulsion is overpowering. He can be diverted

from any endeavor by chancing upon a phrase or a word that suggests which pony

to play that day. He jumps in the bay to

rescue a woman from drowning, and when she drops a word of gratitude, Mutt

abandons her to her fate in order to get to the track in time to bet on

"Thanks Be." He has a heart

attack as a result of some betting misfortune, but on his sick bed, he hears

his doctor recommend rest and "sea air," so he leaps out the hospital

window to place a bet on "Sea Air" to win. He even arises from the dead to get to the

track. Stricken by "apoplexy,"

Mutt dies and is buried. In the grave,

he overhears the grave diggers discussing that day's races, and when they

mention Pullman as a sure thing, Mutt bursts out of the earth and makes his

customary last-panel sprint to the betting window.

To

get money to bet, Mutt finds employment as a policeman, the first of many

miscellaneous jobs he'll hold over the years. But he can't keep the job: he

runs off to the track every time he hears the name of a horse. Eventually, he steals from Cicero's piggy

bank, sells the family parrot, hocks the bathtub and, eventually, the clothes

off his back.

The

comedy in these early strips arises entirely from Mutt's run of bad luck and

his overwhelming obsession. But Mutt

doesn't always lose. Because Fisher was

picking the names of real horses that ran in real races, Mutt sometimes

wins. And when he does, Fisher keeps

track of the size of Mutt's bankroll, recording its dwindling (or increasing)

amount in the last panel of each daily installment. Fortunately for the strip's comedy, Mutt loses

more often than he wins, so he never has a stake large enough to quell for long

the general feeling of frantic desperation that seems to animate him. Then on a fateful day in early February 1908,

the "great plunger," as usual in need of cash, steals money from a

pay phone. This development started

Fisher on a fresh course for his strip—and, as before, he explored new ground

for the medium.

For

a week or so, Mutt remains a fugitive from justice. He eludes the police, but he still makes his

daily dash to the track to place a bet. Caught at last, he is brought to trial, and Fisher stretched the

proceedings out for the next six weeks. Mutt still makes a wager in the last panel on most days, but the real

interest in the strip is generated by the trial. And to the natural suspense that a trial

might create, Fisher added a titillating device: the prosecuting attorney and the various

minions of the law surrounding him are devised to remind readers of several

local politicians who were engaged in a crusade to clean up the city government

of San Francisco.

In

the months of reconstruction following the earthquake, municipal graft had

flourished, inspiring a commendable civic effort to expunge the corruption.

“Reform ran mad,” wrote Bogart Rogers in American

Mercury (December 1954), and “a cabal ruled the city with a pious but iron

hand.” A grand jury handed down 383 indictments, and the trials began. The

investigation was financed by Rudolph Spreckels, who employed “a magnificently

mustached recruit from the Secret Service, William J. Burns,” who later

achieved fame by running down the culprits who blew up the Los Angeles Times building. The leading prosecuting attorney was

Francis J. Heney, “darling of the muckrackers,” who was succeed by an ambitious

young lawyer, Hiram W. Johnson.

“There

were no dull moments during the graft prosecutions,” said Rogers. “Prosecutor

Heney was shot and seriously wounded by a prospective juror named Hass, who

subsequently committed suicide in his jail cell. Police Chief W.J. Biggy was

fished, dead, from San Francisco Bay in a did-he-jump-or-was-he-pushed mystery.

The home of the star prosecution witness was wrecked by a bomb. ... Safes were

cracked; evidence stolen.”

But,

Rogers continued, “the prosecution faltered; convictions were few and far

between.” And San Franciscans were frustrated, then bored, then unhappy—then

ashamed that their city appeared so disreputably in the nation’s spotlight.

Fisher saw the entire enterprise as an opportunity: “I began to kid the

investigation in a good-natured way,” he wrote. Caricatures of the principals

in the investigation showed up in the same roles at Mutt’s trial. “I named them

after things to eat,” Fisher said in “Confessions.” Heney appeared as Attorney

Beaney; Spreckels as Pickles; a lawyer named Shortridge was Short Ribs.

Detective Burns was christened Tobasco. In his book, Wheeler elaborates on

Fisher’s method: “Fisher once saw Burns in a Turkish bath, he says, with curl

papers in his mustache, the great detective’s most pronounced facial

characteristic. The next morning in the strip, Burns was shown wearing curl

papers in his mustache. Throughout the rest of the trial, Burns made his daily

entrance with the curl papers in his mustache, much to Mr. Burns’ own chagrin.

In fact, there are some spectators who say Mr. Burns even let the corners of

his famous mustache droop for a time.”

The

references by which Fisher jogged the memories of his readers are obscure

today, but in the winter of 1908, they were doubtless clanging alarm bells in

the minds of those who read the strip. And Fisher rang the bells every day, day after day, mentioning “curl

papers,” “the $30,000" and one dignitary's "goat" (which Fisher

"got"). As political satire,

this sort of thing was pretty thin. But

as outright ridicule, heavy-handed though it was, it probably delighted

Fisher's readers: the barely veiled

references amounted to name-calling in public, a sensationalized novelty for

the embryonic comic strip form (even if the same techniques were common

practice in the news columns of many newspapers of the day).

According

to Rogers, the laughter Fisher incited gave San Franciscans a much needed

reprieve from the national humiliation their city was suffering daily as the

“graft prosecutions” dragged on without resolution. The title of his American Mercury article is “Augustus

Mutt: Hero of San Francisco.” Said Rogers: “The town grinned, smiled, guffawed

hilariously as day after day Fisher’s sharp and perspicacious pen cut the

reformers to ribbons. He did with laughs what others had failed to do with

countless solemn editorials and pompous speeches. It was widely agreed that he,

more than any other factor, stopped the Donnybrook which was saddening San

Francisco and ruining her municipal reputation.” Amid the laughter, the trials

were permitted to fade away.

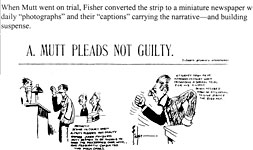

Depicting

Mutt’s trial in the newspaper, Fisher continued in the spirit of

experimentation that had inspired the initial appearance of the strip. He toyed

with the incipient form, capitalizing upon its daily recurrence and the medium

in which it appeared. He converted his

strip from a narrative of sequential visuals to a miniature newspaper. Each daily installment featured a succession

of pictures, "newspaper photos," of the principals with accompanying

captions as Fisher reported the daily developments in the Mutt Case. The strip

assumed a new "voice"—the voice of the front-page headlines of a

daily newspaper. Fisher would use the device again later

in the year; and the technique would be refined twenty years later by Roy Crane

in Wash Tubbs.

Fisher would use the device again later

in the year; and the technique would be refined twenty years later by Roy Crane

in Wash Tubbs.

The

trial is of interest today for yet another reason: it brought us to the immortal Jeff. Mutt is found guilty, of course (he was

guilty, after all), but he is released after serving only a couple days because

of suggestions of malfeasance among the officers of the court. The constant references to the corruption of

the real city government thus opened the way for Fisher to free his

protagonist. But Mutt's sanity was

brought into question during the trial, and as soon as he is released from

jail, he finds himself committed to a local insane asylum. (Fisher skimps on the reasons for this

development; and so, therefore, must we.) In the "bughouse," Mutt meets such

historic personages as Shakespeare, George

Washington, the Czar of Russia, and assorted millionaires, poets, kings, and

captains of industry. Among these

deluded souls is a short bald fellow with muttonchop whiskers who believes he

is James Jeffries, the heavyweight boxing champion of contemporary notoriety

(particularly on the sports pages where A. Mutt appeared). Little Jeff at

last has arrived, wandering on stage March 27, 1908.

Jeff

(called Jeffries for many of his earliest appearances) is the bughouse fall

guy. The other inmates are always playing tricks on the poor boob. But he doesn't seem to mind. As Fisher put it, "What's the diff? He's just as happy as if he had good

sense."

Jeff

did not immediately become Mutt's ever-present side-kick and comic

factotum. He was, rather, just another

member of the strip's growing cast. When

Mutt is released from the asylum, Jeff occasionally visits the plunger—usually

in the company of "General Delivery," another of the inmates. Through most of April and May, however,

Fisher resumed his ridiculing of the city's corrupt politicians, using the same

"newspaper format" approach as he had used during Mutt's trial. For a time, the strip ceased to be a

"strip"—a narrative sequence of drawings—becoming instead a series of

daily tableaux that poked fun at the foibles of local politicians. (All of

these strips can be witnessed in the 1977 Hyperion Press book, A. Mutt.)

When

the 1908 Presidential campaign began heating up that summer, Mutt was again linked

with Jeff. Mutt is the Bughouse Party

nominee for President, and Jeff is the other half of the ticket. This may be the first time a comic character

ran for the U.S. Presidency (and Mutt and

Jeff will do it again several times), but Fisher did not much exploit this

rich vein of material. In fact, he uses

the campaign as an excuse to reprise his now-familiar needling of San Francisco

politicos. He must have enjoyed this

sort of thing a great deal, and he probably was encouraged by public reception

of the maneuver, but the constant chorus of the same material ($30,000, curl

papers, the goat) makes dull reading in later years.

On

Election Day in November, Jeff returns to the strip (as does Mutt). Jeff makes periodic re-appearances over the

next year, eventually proving himself the ideal foil for Mutt. By mid-1909, Jeff is a regular cast member,

appearing frequently, and in July, according to historian Allan Holtz in The Early Years of Mutt and Jeff, the

strip was officially entitled Mutt and

Jeff. But according to the court papers of the 1915 legal skirmish with

Hearst, the first time the names were coupled in print was in 1910 when a

booklet reprinting a selection that year’s strips was published with the title The Mutt and Jeff Cartoons. (Fisher

filed copyright papers dated September 22, 1910. He applied to trademark the

name on November 14, 1914, just as his contract with Hearst was coming up for

renewal; the trademark was granted March 9, 1915. Hearst, meanwhile,

anticipating Fisher’s departure and hoping to secure the strip’s name for a

successor to perpetuate, began using Mutt

and Jeff as a title of the strip on December 11, 1914—but only in the New York American not in other

newspapers to which the strip was syndicated.)

Fisher

had widened the scope of his strip's focus very early in its history, as we've

seen, by turning from horse-playing to politics (from one kind of horse-play to

another, we might say). He did it

deliberately: he aimed to broaden the

appeal of the strip. And he continued to

search for ways to make Mutt and Jeff interesting to the widest possible readership. He saw that many entertainers achieved success by appealing to the

special interests of a particular group. He reasoned that "if Mutt and Jeff appealed to everyone—high-brow,

low-brow, man, woman, and child—their value to me would be much greater."

Although

he subsequently determined that "the high-brow sense of humor does not

differ much from the low-brow," he decided his other distinctions were

valid. "So I worked out a

scheme," he wrote in American

Magazine of May 1920, "which I have followed ever since. Mutt and Jeff do something one day that will

tickle the women; the next day, the kids; the next day, I try to give the old

man a laugh. If Mutt hits Jeff across the

face with a fish, Father says, `That isn't funny!' Mother sniffs and looks away without a

grin. But the small boy yells. The next day, Mother gets the laugh. And finally, I squeeze a grin out of

Father. After a while, it gets to be a

habit."

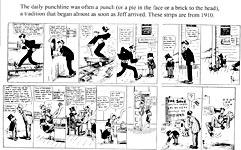

With

the emergence of Little Jeff as Mutt's partner, the strip acquired the humane

dimension that made it a classic: it

ceased to be solely a daily chorus about crass money-grubbing and became a

cautionary tale about the human condition. Mutt remained the scheming conniver that he'd always been as a

horse-player: his role in the strip was

to come up with ways to make a buck. Jeff's seeming mental deficiency made him the perfect innocent, the

ideal foil for Mutt the Materialist. And

the strip's comedy soon took its vintage form with Mutt's avaricious

aspirations perpetually frustrated by Jeff's benign and well-intentioned

ignorance. Foiled by the little man's

uncomprehending bumbling, Mutt often responds with classic vaudevillian

exasperation: the strips' punchlines are

frequently precisely that, punches. In

the best slapstick tradition of the stage, Mutt lets his pesky partner have it

in the face with a pie, a dead chicken, a brick, or whatever object he happens

to have in his hand when he realizes the little runt had scuttled yet another

scheme with his literal-minded stupidity. Being beaned with a brick was a classic Mutt and Jeff finish long before George Herriman took the same

device and turned it into krazy katty poetry.

Often

deploying gentle Jeff as his shill in a succession of careers and enterprises

together, Mutt sometimes conceives plans that have the incidental effect of

victimizing the little fellow. But we

always root for Jeff: visually, the

short guy is the underdog, and most American readers cheer for the underdog out

of cultural habit. As usual, Fisher was

perfectly aware of what he was doing:

"Mutt

is a big, simple-minded boob who is always trying and always blundering,"

Fisher once said. "The great

majority of people like Jeff much more than they do Mutt; but Mutt always has

been my pal and friend. Mutt is trying,

and making mistakes, just like the rest of us, and he is a rough worker at

times. People like Jeff because he is

smaller, and almost every person in the world is for the little guy against the

big one."

And

Little Jeff in his innocence and kindliness justifies our faith. Regardless of Mutt's machinations, Jeff

invariably winds up on top, unwittingly victorious over whatever traps or

pitfalls may have lain in his path. So

does the benevolent nature of humankind seem somehow to triumph eventually over

its baser instincts in the long, long run. We laughed at them both, but we merely tolerated Mutt and his schemes;

we loved little Jeff.

Fisher

and his assistants were able to work endless variations on their simple

theme. It wore well. The strip ran for over 75 years.

When

Ed Mack died in 1932, the strip was inherited by his sometime assistant, Al Smith. Albert Schmidt was born March

2, 1902, in Brooklyn, New York, the son of Henry Schmidt and Josephine Dice.

After attending public schools, he started in newspapering as a copy boy for

the New York Sun, leaving within a

year for the New York World, where he

followed the traditional apprenticeship route from copy boy to cartoonist:

first, he was permitted to assist other cartoonists, then he drew an occasional

fill-in cartoon, and eventually he graduated to his own regular feature. As he

launched into his cartooning career, Smith married Erna Anna Strasser on May

25, 1921. Smith’s From 9 to 5, a

panel cartoon about office life, was syndicated by the World until the newspaper folded in 1931. United Feature Syndicate

continued the strip for a short time, but when it ceased, Smith freelanced,

doing artwork for various clients, including the Works Progress Administration

and John Wheeler’s Bell Syndicate, where, presumably, he assisted Ed Mack from

time to time. When Mack died, Wheeler approached Smith about ghosting the

strip.

Smith

told the story in the newsletter of the National Cartoonists Society, The Cartoonist, on the occasion of

Fisher’s death in 1954:  “It was during the Depression years, when my wife and I had three

small girls, and I was digging ditches for the WPA in New Jersey, that I

received a phone call from John Wheeler, president of Bell Syndicate, to come

over and see him. Bud Fisher needed an assistant artist to help him with Mutt and Jeff. My wife brought the good

news in our Model T Ford while I was in mud up to my ankles digging on the job.

I threw my shovel to one side and bid my associate ditch diggers a fond but

quick good-bye, and away I went to Mutt and Jeff, and I’ve been with them ever

since.”

“It was during the Depression years, when my wife and I had three

small girls, and I was digging ditches for the WPA in New Jersey, that I

received a phone call from John Wheeler, president of Bell Syndicate, to come

over and see him. Bud Fisher needed an assistant artist to help him with Mutt and Jeff. My wife brought the good

news in our Model T Ford while I was in mud up to my ankles digging on the job.

I threw my shovel to one side and bid my associate ditch diggers a fond but

quick good-bye, and away I went to Mutt and Jeff, and I’ve been with them ever

since.”

Fisher

was not particularly easy to work for, Smith discovered: “Very few people

really know—or should I say ‘understood’—Harry Conway (Bud) Fisher. He somehow

struck me as being an individual with a dual personality. It seems he was right

on the line of being an ordinary person and a genius if there is such a line

between the two. I never knew how I would find him. One day, he would be kind,

gentle, understanding and appreciative, and the next, hell in all its fury

would break loose. A whole week’s work of comic strips would be destroyed by a

few strokes of his brush, dripping with black ink. Good was not good enough,

and right there, I think, likes the secret of his success. He always wanted the

best in everything, and he usually got it. At the time, it was very difficult

for me to understand this man. He was so different from everyone else. Early in

my career with him, he had me on the point of a nervous breakdown. I left him

and went away for a week to rest, coming back with the determination to conquer

this most unusual job. The years started to roll by and after quitting four

times and being fired once—and in each instance the following day being called

on the phone as though nothing had happened—I began to understand Mutt and

Jeff’s creator.

“Much

of the time in later years, he was ill and confined to bed in his apartment. He

was always afraid of being trapped in a fire. He never used an ashtray but

would always drop his cigarette butts into a basin of water which stood by the

side of his bed.

“We

became very close friends as the years passed by. I had many pleasant visits

with him when he would reminisce until three or four in the morning and tell me

all about the big and little events in his life. I’m a good listener, and he

liked a good listener. He could talk for hours, going from one subject to

another. I hope I brought him some joy and happiness for in his passing years,

he was a lonely man.”

Despite

the sporadic interference from the flamboyant and heavy-drinking Fisher, Smith

ably conducted the classic strip, eventually revamping it to suit his own

comedic sensibilities. Mutt became less a race track tout and sporting

enthusiast and more a paterfamilias and bread winner. The habitual gambler was thoroughly domesticated, and the

strip focused on his frustrations as husband and father, with occasional forays

into various entrepreneurial schemes. Smith’s penchant for humorous animal

antics yielded a secondary strip, Cicero’s

Cat (about the cat that belonged to Mutt’s son), in a feature that ran at

the top of the Mutt and Jeff Sunday

page. After Fisher died in 1954, Smith was permitted to sign his own name to

the strip, which he continued to do until he left it at the end of 1981, having

produced the feature over four times longer than its creator did. Smith died

five years later, November 24, 1986.

Smith’s

graphic style was more polished than that of his several ghostly predecessors

on the strip, but he nonetheless preserved the turn-of-the-century feel of the

visuals. By the end of the 1930s, the faces and anatomy of his cast had

crystallized into static doodles, stylized glyphs of human appearance,

embellished by the cross-hatching and shading techniques of the earlier era.

In 1950, he inaugurated his own feature syndicate,

the Smith Service, to provide comic strips and cartoons to weekly newspapers.

For this purpose, Smith produced two features, Rural Delivery and Remember

When. Other similarly folksy offerings included Down Main Street by Joe Dennett and Pops by George Wolfe. Active in the National Cartoonists Society,

Smith held several offices (treasurer for nine years) before being elected

president (1967-69). In 1968, his NCS colleagues awarded him the organization’s

trophy for the year’s Best Humor Strip.

In

late 1981, while Smith was still cranking out Mutt and Jeff, a coup was fomenting in the back alleys of the

syndicate. The strip was appearing in only about 40 papers, cartoonist Jim Scancarelli told me, and various of

the powers-that-were began to murmur disconsolately about it. Speculation grew

that Mutt and Jeff would do better if

it were somehow up-dated, modernized, brought into the twentieth century. An

agent, one-time syndicate employee and now a freelance prospector in feature

properties, hearing the murmurs, thought of George Breisacher.

Breisacher

was a staff artist and cartoonist at the Charlotte

Observer in North Carolina, where he had been for the last seven or eight

years. Born August 24, 1939, Breisacher had explored several occupations before

settling on cartooning. After graduating from high school in 1957, he’d worked

as a mail carrier until 1963 when he “involuntarily” entered the Army, playing

clarinet in the 158th Army Band. He left the martial musical

profession in 1965 and began to pursue a career as a newspaper

cartoonist/artist, “doing everything I could do to gain experience,” he said. A

series of jobs landed him at the Pontiac

Press in Michigan in 1967 and then, in 1973, at the Observer. In 1978, he began producing a daily comic strip with

United Feature: called Knobs, it was

about television. The strip ceased in 1980, and Breisacher thereupon embarked

upon an ambitious effort to re-enter syndication with another strip. He

submitted candidates for consideration with such frequent regularity that his

name was familiar at the syndicate and known to the freelance agent, who, as

1981 dwindled, phoned Breisacher and asked him if he’d like to take over an

old-time classic strip. Breisacher, momentarily without another strip idea to

submit, said he’d like to consider it, and the agent invited him to New York to

discuss the matter. Scancarelli, who, as we shall see, was in a position to

know, told me what happened next.

Breisacher

found himself having lunch with the agent who had invited Al Smith to join them.

During lunch, the agent, to Breisacher’s astonished consternation, told Smith

that the syndicate was unhappy with his work on Mutt and Jeff, felt the strip needed a shot of adrenalin, and was

going to ask Breisacher to administer the needed nostrum.

“So

Smith didn’t know he was on the way out when he came to lunch?” I asked

Scancarelli.

“That’s

what George told me,” said Jim. “Big surprise.”

At

the time, Scancarelli continued, Breisacher didn’t know which of the Mutt and Jeff characters was the tall

one and which was the short one, but he accepted the assignment for the sake of

the challenge. He did the strip for the first couple weeks of 1982, but,

according to Scancarelli, he modernized the look of the feature so much that

subscribing newspapers began to complain.

“George

drew it like no one had ever seen before,” Jim told me. “It was unique.”

The

syndicate asked him to tone down his treatment and draw the strip in a somewhat

less extravagant manner, which Breisacher, as it turned out, didn’t want to do.

Having concocted the new, modern style, he evidently didn’t want to scale it

back into something akin to the traditional Fisher-Smith manifestation.

Whatever the cause, Breisacher phoned his Charlotte friend and fellow

cartoonist Scancarelli, who was at the time assisting Dick Moores on Gasoline

Alley.

If

second acts are almost never as good as first acts in syndicated comic strips,

third acts are completely unheard of. And yet, Gasoline Alley has enjoyed both the impossible and the unheard of. Moores, born in 1909, performed the

impossible when, after a four-year apprenticeship on the strip, he took it over in 1960 at the retirement of

its creator, Frank King; and

Scancarelli, born in 1941 (coincidentally, on August 24, same date as

Breisacher but a few years later), did the unheard of when he succeeded Moores

at the latter’s death in 1986. Before becoming Moores’ assistant in 1979,

Scancarelli worked as a commercial artist, first in television (he made the

first color animated movie for a local tv station in his hometown, Charlotte),

then, freelance, preparing slide art. When computers came along, capable of producing slide art faster and

cheaper than an artist, Scancarelli was suddenly out of work. That’s when he joined Moores, eventually inking

everything on the strip except the characters’ faces. And then came Mutt and Jeff.

Starting

with the January 18, 1982 release, Breisacher wrote and Scancarelli drew Mutt and Jeff for the next eighteen

months, until the strip, finally, expired with its June 25, 1983 release. Their

tenure embraced the strip’s 75th anniversary on November 15, 1982,

and when, eleven years later, Gasoline

Alley passed the three-quarters century mark, Scancarelli became the only

cartoonist to have worked on two strips in their seventy-fifth year.  At first, Breisacher

turned the strips over to Scancarelli with the speech balloons lettered and

inked, but Scancarelli soon asked him not to ink the lettering: “George was a

good gag man,” Jim said, “but Mutt was a tall character, and sometimes George’s

speech balloons didn’t leave me enough room at the top of the panel to draw

Mutt at full length. With penciled speech balloons, I could shift things around

to make room for drawings.”

At first, Breisacher

turned the strips over to Scancarelli with the speech balloons lettered and

inked, but Scancarelli soon asked him not to ink the lettering: “George was a

good gag man,” Jim said, “but Mutt was a tall character, and sometimes George’s

speech balloons didn’t leave me enough room at the top of the panel to draw

Mutt at full length. With penciled speech balloons, I could shift things around

to make room for drawings.”

One

of Breisacher’s gags yielded an unexpected consequence.  The punchline gave Newark, New Jersey,

a negative glow, and the mayor promptly dispatched a letter to Breisacher, forbidding

him to ever set foot in the precincts of his fair city—“or even to fly over

it!” Scancarelli said. “Some folks take their comics seriously!”

The punchline gave Newark, New Jersey,

a negative glow, and the mayor promptly dispatched a letter to Breisacher, forbidding

him to ever set foot in the precincts of his fair city—“or even to fly over

it!” Scancarelli said. “Some folks take their comics seriously!”

Scancarelli thought Smith’s drawing style was entirely adequate, but he didn’t want to draw it that way: it tied the strip to the 1940s, he thought. He admired the appearance of the strip in the 1920s when Ed Mack was doing it.

|

|

In developing his own stylistic treatment, he modeled the construction of the characters on Mack’s—their way of walking and standing; he elongated Mutt’s nose a little and thinned it out, but it was in inking the drawings that Scancarelli streamlined the strip’s appearance and modernized it. He added just a little cross-hatching and fine-line feathering along the edges, enough to give the drawings an antique gloss, but his flexible brush strokes, waxing and waning as they delineated the figures in bold outline, burnished Mutt and Jeff to a throughly up-to-date sheen.

|

|

All

the effort Breisacher and Scancarelli devoted to the strip came, alas, to

naught. The circulation of Mutt and Jeff did

not climb miraculously, and in June 1983, a syndicate official phoned

Breisacher and invited him to lunch in New York. Breisacher flew up and had

lunch, during which, the syndicate factotum, in effect, fired the cartoonist.

Breisacher,

bemused by the coincidence of the similar circumstances of his hiring and his

firing, remarked that “it was the first time I had to fly to get fired.”

But

he wasn’t so much fired as he was retired. “The syndicate guy told George we

could continue it if we wanted to,” Scancarelli said, “but at a considerably

reduced rate. Only about half of what we’d been getting. We were splitting only

$150-200 a week as it was, and when we talked it over, we decided—six dailies

and a Sunday strip—it was too much work for too little recompense. So we gave

it up.” And so did Field Newspaper Syndicate.

Afterwards,

Scancarelli joked that he had single-handedly killed the famed strip. The gag

on June 23 had been his and his alone. Breisacher had evidently taken the day

off. “I wrote it and drew it myself,” Jim exclaimed, “and two days later, the

feature came to an end! I didn’t think the June 23 strip had been that bad!”

After

the demise of Mutt and Jeff, Breisacher

concocted his second tv-related strip, Channel

One, which he did just for the Observer; by 1988, he was doing another Observer-only

strip, this one, Ozone, offering

off-beat comedy appeared three times a week.  He also began devoting more and more of his spare

time to the National Cartoonists Society, which he had joined in 1973. He

started the Southeast chapter of NCS in 1990, the year after he took on the

editorship of The Cartoonist. He

edited the newsletter for the next nine years, then served as NCS president,

1997-99. He retired from the Observer in 2000 and died in 2003, a respected and revered member of NCS.

He also began devoting more and more of his spare

time to the National Cartoonists Society, which he had joined in 1973. He

started the Southeast chapter of NCS in 1990, the year after he took on the

editorship of The Cartoonist. He

edited the newsletter for the next nine years, then served as NCS president,

1997-99. He retired from the Observer in 2000 and died in 2003, a respected and revered member of NCS.

In

1986, Scancarelli inherited Gasoline

Alley and sustained the strip’s King-crafted homespun tone and Moore-like

crisp visuals, winning the NCS Best Story Strip Plaque in 1989. And he’s still

at it. Next year, 2008, Gasoline Alley will

be ninety on November 24, and Scancarelli will have been working on it for 29

years (signing it for 22), just a year short of his predecessor’s mark: Moores

worked on the strip for 30 years, signing it for 26. Says Scancarelli about the

writing of the Gasoline Alley: “Frank King and Dick both left very indelible

fingerprints on these characters. Their

personalities are so set that they act out the stories themselves. I just throw them into a situation, and they

go about doing whatever they’re going to do.”

Scancarelli

has done stories on such topical issues as deafness (Walt’s) and

naturalization, and he has sent members of the ensemble off on some fairly wild

adventures, too. A passionate fan of his

medium, he often devotes Sunday strips (no longer “pages’) to nostalgic

evocations of the comics of yesteryear, and he draws every installment, daily

or Sunday, with painstaking thoroughness, seemingly in defiance ofthe

hostility to cartoon art on any scale that prevails throughout the newspaper

industry. Mutt and Jeff, burnished into modernity by Scancarelli’s fluid line,

make periodic appearances in the strip. They and numerous of their vintage

paper-and-ink fellowship reside nearby at the Comic Strip Characters Retirement

Home, where their best friend, Walt Wallet, Gasoline

Alley’s senior citizen, comes to visit every so often. But even when the

gangly Mutt and the diminutive Jeff are out of sight, they’re scarcely out of

the nation’s consciousness: whenever we see a tall man with a short friend, we

cannot help but think of Mutt and Jeff. They’ve joined the immortals.

to cartoon art on any scale that prevails throughout the newspaper

industry. Mutt and Jeff, burnished into modernity by Scancarelli’s fluid line,

make periodic appearances in the strip. They and numerous of their vintage

paper-and-ink fellowship reside nearby at the Comic Strip Characters Retirement

Home, where their best friend, Walt Wallet, Gasoline

Alley’s senior citizen, comes to visit every so often. But even when the

gangly Mutt and the diminutive Jeff are out of sight, they’re scarcely out of

the nation’s consciousness: whenever we see a tall man with a short friend, we

cannot help but think of Mutt and Jeff. They’ve joined the immortals.

Some of the

foregoing appeared as a chapter in my book, The Art of the Funnies, but that material has been extensively supplemented here with

biographical information about Smith and Breisacher and Scancarelli, plus more

information about Fisher. But if this sort of expedition through the history of

the medium gives you pleasure, you’ll be happy to know there’s more of the

same, cover-to-cover, in The Art of the Funnies, an advertisement for which appears here.

send e-mail to R.C. Harvey

art of the comic book - art of the funnies - reviews - order form - rants & raves - Harv's Hindsights - return to main page