Morrie

Turner

To Say the

Name Is Both Eulogy and Tribute

THE

LEGENDARY AFRICAN AMERICAN CARTOONIST MORRIE TURNER sometimes said, tongue in

cheek, that when they gave African Americans Black History Month, “they gave us

the shortest month in the year.” He was joking because he knew Black History

Month expanded from Black History Week, which, he said, started with Abraham

Lincoln’s birthday and ended with Frederick Douglass’. But that was only partly

true: we don’t know which day Douglas was born on because he was born a slave,

and few people around slaves a lot in those days thought they where human

enough to keep track of their birthdays. When he grew up, Douglass chose February

14 as his birthday, but that is only two days after Lincoln’s birthday so the

interval was scarcely a week, black history or not.

About

Black History Month, Henry Louis “Skip” Gates, Jr. wrote recently: We may be “a

nation within a nation,” as the 19thcentury Black abolitionist Martin Delaney

declared, but, from slavery to freedom, our 500-year [African American] story

is indivisible from that of the nation. And to leave it out on any given day

(or to carve it out for “special display on only 28 or 29 days in February) is

to distort our common past while robbing those who will shape the future of an

expansive archive of resiliency and hope.”

Morrie

would emphatically agree. He started his Black history feature, Soul Corner, to celebrate Black

History Week one year, he said. “Then I said, ‘Wait a minute. Black history is

being made every day.’ So I can keep going.” And he did. We keep going with a

gigantic hunk of Black History this month by posting this appreciation of

Morrie, who died January 25.

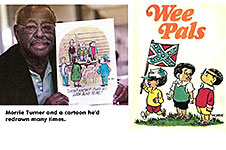

MORRIS NOLTEN

TURNER died in Sacramento, California on January 25, 2014, and if he’d lived

another 21 days, he would have been able to celebrate the 49th anniversary of the start of his comic strip Wee Pals during Black

History Month. He was hoping to make it to that. And that would have been

poetry of a celestial sort because Morrie Turner made Black history—and

American history and comics history—with his strip. He broke the color barrier

twice, said Paul Vitello in the New York Times —“as the first African

American comic strip cartoonist whose work was widely syndicated in mainstream

newspapers and as the creator of the first syndicated strip with a racially and

ethnically mixed cast of characters.”

At

the Sacramento Bee, Robert D. Davila wrote: “A cartoonist by profession,

Turner influenced American culture as a civil-rights activist, historian,

social commentator and teacher.”

He

liked to be called Morrie—and that’s how he signed his strip—so that’s what

I’ll do here.

Born

December 11, 1923 in Oakland, California, Morrie was in the newspaper business

from birth. His father was a pullman porter, and in those days, the black

newspapers of Chicago and Pittsburgh and New York and other major cities achieved

national circulation by train: pullman porters carried bundles of the papers

across the country, dropping them off into friendly hands at cities they passed

through. Morrie’s brothers sold the major black newspapers, so Morrie saw them

as soon as he could see.

Morrie

drew pictures from an early age; by the fifth grade in school, he was drawing

cartoons. His father was away from home at work much of Morrie’s childhood, and

his mother, a nurse, raised him, said Vitello—encouraging “his artistic talent

and instilling in him a reverence for a pantheon of black historical figures.”

When

he was in his teens, he was clipping out of Harlem’s Black newspaper, the Amsterdam

News, the cartoons of Ollie Harrington and trying to copy him. “Oh, man,”

Morrie said, “until then, I had never seen anybody who could drew characters

that reflect people”—black people.

Morrie

admired and wrote to Milton Caniff, who was doing Terry and the Pirates at the time. Caniff responded with a typed six-page letter of pointers on drawing

and storytelling. “It changed my whole life,” Morrie told me. “The fact that he

took the time to share all with a kid, a stranger. Didn’t impress me all that

much at the time, but it impresses the hell out of me now.” Perhaps as a

consequence, Morrie was generous in sharing time with young aspiring

cartoonists, particularly African American aspirants.

One

of them was Robb Armstrong, who now does Jump Start, a strip about a

black cop and his nurse wife, their kids and extended family. “Morrie was part

of my DNA,” Armstrong told the Los Angeles Times. “I used to carry a Wee

Pals lunchpail.” Morrie steered him into syndication. He’d been given

Armstrong’s phone number by an editor at a Philadelphia newspaper, and he

phoned the young man. Armstrong said he felt like some young Hollywood actor

getting a call from George Clooney.

Morrie

started high school at McClymonds High School in Oakland, but when his family

moved to Berkeley, he finished at Berkeley High School.

During

World War II, Morrie was in the Army Air Corps and was stationed at Tuskegee

Army Air Field. The famed all-black 332nd Fighter Group, known as

the Tuskegee Airmen, trained there, as did the black 477th Bombardment Group, which, despite being trained and ready, never saw action in

combat. Attached to the 477th, Morrie was a staff clerk and also

worked on the base newspaper as a reporter and illustrator. He did a strip

called Rail Head about a feckless recruit’s bumbling misadventures, and

he did gag cartoons—crude artwork, he remembered, but getting printed was an

education.

“It

seemed easy then,” Morrie once recalled. “Sometimes it was humor by committee,

and a lot of it was so ‘in’ that nobody outside the base could understand it.

But I began seeing the power in it. We could dig at some lieutenant, and nobody

could do a thing about it.”

Returning

to civilian life after the War, Morrie married his childhood sweetheart, Letha

Harvey (no relation) on April 6, 1946. Then Morrie chased after a number of

careers. He was a radio program host, a comedian, and briefly ran a greeting

card business and did artwork for various charitable causes. Then just about

the time of the celebrated Brown v. Topeka Education Board decision in 1954, he

hired on as a clerk at the Oakland police department. He worked there for the

next ten years, and during off hours, he freelanced cartoons and illustrations

to industrial publications and trade journals and national magazines, including

the Saturday Evening Post and other mainstream periodicals but also Ebony and Negro Digest (which became Black World) and the Chicago

Defender.

Morrie

met Charles Schulz at a gathering of California cartoonists, and they became

friends. The civil rights movement was gathering momentum with sit-ins and

marches in the South, and once while they were having lunch, Morrie asked

Schulz why he didn't have any black kids in Peanuts, and Schulz told

Morrie he should create his own.

“I

couldn’t participate in the marches in the South, and I felt I should,” Morrie

later told the San Francisco Chronicle. “I was working and had a wife

and kid. So I decided I would have my say with my pen.”

Right

about then, Dick Gregory, comedian cum civil rights activist, came along

and gave Morrie another nudge.

IN 1962,

GREGORY had published a memoir, From the Back of the Bus, about his

crusading adventures. (“Segregation is not all bad. Ever hear of a collision

where the people in the back of the bus got hurt?”) The comedian was working on

a continuation of this literary venture, a more overt autobiography, which in

1964 he would entitle Nigger (so that every time his mother hears the

word, Gregory explained, she’d know her son’s book was being discussed and

promoted). And a friend brought Gregory around to Morrie’s place to meet the

cartoonist. The two spent the day “rapping” (as Morrie put it), and Gregory

suggested that Morrie illustrate his book with cartoons and comic strips.

“It

wasn’t the kind of cartoon that I was drawing then,” Morrie remembered when I

talked at length with him last spring. “At the time,” he said, “I was doing all

right with industrial cartoons. They weren’t making a lot of money, but I was

having a lot of fun. Gregory wanted me to do some cartoons that related to

black people, and I liked the idea because it was me. All the drawings and

cartoons I’d done up to that point were not really me. They were something

foreign to me. I would create cartoons about golf, but I knew nothing about

golf. Never played the game at all. And medical cartoons, doctors, dentists—not

me.”

The

cartoons Morrie did for black magazines and newspapers like the Chicago

Defender were more to his liking. “Some were very close to being editorial

cartoons—very close,” Morrie said, “—but they were not. They were humorous,

funny, and then I realized they were funny because they were editorial

cartoons.”

But

they still weren’t Morrie. Gregory’s proposal, which eventually came to

nothing, started Morrie thinking. And just about then, Charlie Brown appeared

in a Civil War cap. Morrie pondered: what if Charlie Brown were Black? And what

if the cap were a Confederate cap? “Now that,” wrote Tom

Carter in the Cartoon Club Newsletter, “was indeed a laugh—a child so

naive he could sweep away generations of ill will with one innocent, ironic

gesture.”

“That

set everything in motion,” Morrie said.

He

began thinking about a black Peanuts. He created Nipper, the black kid

with the Confederate cap. “Nipper was named after the comedian Nipsey Russell,”

Morrie said, “—but Nipper was me.”

Morrie

surrounded Nipper with black moppets, called the strip Dinky Fellas, and

sold it to his hometown’s weekly black paper, the Berkeley Post, and to

the Chicago Defender. Dinky Fellas began July 25, 1964. And

Morrie quit the Police department job to devote himself full-time to cartooning.

The

editor at the Chicago Defender urged Morrie to sell the strip to a

mainstream metropolitan newspaper, and Morrie approached the Berkeley

Gazette, the city’s daily, but the editor wasn’t interested. Enter Lew

Little.

Since

1962, Little had been a salesman for the newspaper feature syndicate run by the San Francisco Chronicle, and in 1964, he was feeling his way towards

starting his own syndicate. On a visit to a newspaper in Washington, D.C., he’d

talked with an editor who delivered his considered opinion about the state of

comic strips in the United States: what this country needs, he said, is a comic

strip about black people. Serendipitously, a few weeks later, Little was in the

editor’s office at the Berkeley Gazette, and when he told that editor

what the editor in Washington, D.C. had said, the Gazette editor said,

“I just saw one. I don’t know the cartoonist’s name, but the strip appears in

the Berkeley Post.”

Little

went to the Post office and got Morrie’s name and phone number. He

called Morrie:

“Hello,

I’m Lew Little and I’m calling from the Post office,” he said, and

Morrie thought he was calling from the local station of the U.S. Postal

Service.

“I

thought, what kind of a syndicate would be calling from the post office? And I

told him I couldn’t see him for a couple hours.”

But

Little was not to be denied. He waited. And when Morrie finally met him, Little

offered him a contract. Morrie says he tried to discourage him, but Little was

persistent, and Morrie signed.

“A

week later,” Morrie remembered when we talked, “he phoned and asked me if I was

standing up or sitting down. I said, ‘Standing up.’ He said, ‘You better sit

down.’ And he told me Dinky Fellas would start on Monday, February 15,

1965, in three newspapers, the Los Angeles Times and two others, one in

Philadelphia.”

That

was the beginning of Lew Little’s syndicate. And Wee Pals wasn’t too far

off. The third paper may have been the Oakland Tribune. It was the Tribune’s editor who changed the name of the strip from Dinky Fellas to Wee

Pals. The old title retired on December 18, 1965. And it may have been Lew

Little who instigated the infiltration of the strip by kids of other races and

ethnicities. Morrie said that the strip got its its soul when he developed a

diverse cast that, he said, reflected his Oakland experience.

In

interviews, he said that his own ethnically diverse neighborhood inspired his

characters. “White, Filipino, Japanese, Chinese, Black — it was a rainbow,” he

told the San Francisco Chronicle. “I didn’t know that wasn’t the way it

was other places. Oakland was that way before the War. We were all equal.

Nobody had any money.”

With

an expanding and increasingly multicultural cast, Morrie found his metier and a

cause. He often said that the intent of the strip was to promote tolerance and

understanding. He wanted “to portray a world without prejudice, a world in

which people’s differences — race, religion, gender and physical and mental

ability — are cherished, not scorned.”

The

diminutive buddies started with Nipper, whose Confederate Army cap always masks

the top half of his face, and Nipper’s dog named General Lee, a soul brother

named Randy, the chubby white bespectacled intellectual Oliver; Peter, a

Mexican American; Rocky, a Native American; a Latino named Pablo; Diz, a

beret-wearing hip African American proudly wearing a dashiki and sunglasses;

George, an Asian American; Connie, a spirited feminist; the freckle-faced

Jewish Jerry; and Sibyl Wrights, a black girl who was modeled on Morrie’s wife

and Shirley Chisholm, the late New York congresswoman and civil rights leader.

Since

the early 1960s, the expression “Black Power” had been widely deployed to

emphasize racial pride and the creation of black political and cultural

institutions that would nuture and promote black interests and advance black

values. Morrie’s kids climbed on that band wagon but immediately broadened its

scope.

In

choosing a name for their club, the little pals were at first divided: the

black kids advocated Black Power; the Asian kids, Yellow Power; the Latino

kids, Brown Power. But they finally settled on the unifying Rainbow Power,

where the colors work in harmony.

Said

Morrie: “That’s the power of all colors working together. And that’s truly the

thing with the strip, and I keep trying to come up with a gag once in a while

to remind everybody what it’s all about.”

He

admitted, with a wry smile, to being a little miffed when Jesse Jackson came on

the scene with his Rainbow Coalition. Jackson may not have appropriated the

term and the idea from the strip, but to Wee Pals readers, it couldn’t

help but look like theft. Whatever the case, it was a good move: it perpetuated

the concept of racial harmony.

But

Morrie wasn’t the first to use “rainbow” to suggest racial diversity. Josephine

Baker, the African American exotic dancer who took Paris by banana tutu in the

1920s and 1930s and who spied for the Allies during World War II, adopted

twelve children from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds and called them her

Rainbow Tribe, making headlines around the world in the 1950s.

THE RIOTS IN

WATTS and other big cities in the summer of 1965 stalled sales of the strip at

five subscribers: newspaper editors were leery of publishing anything that

might stir up trouble. It was a time of panicky absurdities.

“One

of the editors at the Los Angeles Times accused me of orchestrating the

Watts Riot,” Morrie told me. “How’m I going to orchestrate a riot? The strips

are done six weeks in advance.”

Morrie

kept on, and then in the wake of the assassination of Martin Luthur King, Jr.

in April 1968, editors suddenly wanted ways to give race relations a human

face. Turner’s daily lesson in tolerance was just what was needed, and sales soared.

“The

nation felt guilty and, zoom, my numbers went up,” Morrie said. “I went to 30

newspapers in about a week. Suddenly, everybody was interested in me. You can

imagine how I felt—I mean, I’m benefitting from the assassination of Dr. King,

one of my heroes. It was kind of a bittersweet experience.”

At

its peak, Wee Pals was running in 100 newspapers.

Soon

after Wee Pals achieved wider national circulation, Vitello reported,

Morrie got an angry letter from a reader about Nipper and his Confederate hat:

“No self-respecting black person would wear such a hat,” the writer said,

suggesting that Morrie “get to know some black people.”

Said

Morrie: “I wrote back and told the person that I happen to know two black

people—my mother and my father.”

So

what about the Confederate hat, an interviewer wanted to know.

Morrie

paused, considering the question, and then replied: “Forgiveness.”

“He

was always looking for a teaching moment,” said Andrew Farago, curator of the

Comic Art Museum in San Francisco.

Turner

appealed to mainstream audiences with moderate and pragmatic messages about

inclusiveness and equality. While he explored thornier racial issues for

publications such as Black World and Ebony, even those messages

were tempered. One cartoon shows an African American father figure speaking to

a dashiki-wearing youth with an Afro hairstyle; the caption: “It’s time to talk

about Job Power.”

The

tone of the strip is resolutely positive. When

Nipper proved a flop at baseball and said that he would never be another Hank

Aaron, he dusted himself off and decided to follow the path of black

intellectuals such as Frederick Douglass and George Washington Carver.

Over

its 48-plus years, Wee Pals was distributed by eight syndicates. Lew

Little Enterprises distributed the strip from its start until April 22, 1967;

then Register and Tribune out of Des Moines, April 24, 1967 - May 7, 1972; then

King Features, May 8, 1972 - July 1, 19977; United Feature, July 2, 1977 -

September 28, 1980; Field Enterprises, September 29, 1980 - April 22, 1984;

News America, April 23, 1984 - March 15, 1987; North America, March 16, 1987 -

1990. Creators Syndicate was distributing the strip when Morrie died.

This

roll call might suggest some dissatisfaction on one side or the other, Morrie’s

or a syndicate’s. Not so. The syndicate history of Wee Pals is the

employment record of Lew Little. He went from syndicate job to syndicate job,

always advancing, and wherever he went, he took with him the strips he’d

discovered. Tom K. Ryan’s Tumbleweeds, another Lew Little discovery, has

a syndicate history that parallels Wee Pals exactly.

In

going with Creators in 1990, Morrie finally divorced himself from Little.

YEAR AFTER

YEAR, Morrie continued adding characters to diversify his cast—the deaf and

mute Sally, the Vietnamese Trinh, the bespectacled Charlotte, who is in a

wheelchair—thereby increasing the all-inclusive nature of the strip and its

relevance to everyone. But there was yet another reason for the expanding

roster:

“When

I ran out of ideas,” Morrie said, “I’d bring another character in.”

Once

when he had run out of ideas, he phoned Schulz.

“What

do you do when you run out of ideas?” Morrie asked.

Schulz’s

suggestion: “Think funny.”

I

told Morrie that Schulz once said to me that he got ideas by doodling his

characters on a pad of paper.

“Yeah,

yeah,” said Morrie, “—that’s how you think funny.”

In

1972, Morrie had added to the cast the bullying, somewhat dim white boy named

Ralph, who parrots the racist beliefs he hears at home.

“He

was prejudiced but he didn’t know he was prejudiced,” Morrie said. “Readers

didn’t like him and wanted him out of there. But he was valuable because I

could do gags with him that I couldn’t do with anybody else. I could make him

say things that were funny and that showed how ridiculous prejudice was.”

Sometimes

the jokes were a little heavy-handed. Asked soon after he moved into the

neighborhood how he likes it, Ralph says: “Black kids! Liberated females ...

Indians ... Jewish kids ... Chinese and Mexicans ... Something should be done

to improve the quality of this neighborhood, Oliver.”

And

Oliver, turning on his heel, says: “Well, as a starter, you could

move out!”

But

Ralph is back a few days later with a bandaged finger. “I cut it while making a

‘keep out’ sign,” he growls.

“Well,”

says Randy, “we learned one thing from your bandage—your blood is just red.”

“What

do you mean by that?” Ralph sneers.

“We

thought maybe it was red, white and blue,” grins Randy, walking away.

Nipper

and his friends invariably expose Ralph’s racist notions as foolish, and he

usually accepts their reproofs more-or-less good-naturedly (as good-naturedly

as scowling Ralph ever is). It was a lesson for us all—and impossible of

achieving without Ralph.

Soon

after King was killed on April 4, 1968, Schulz complied with Morrie’s

suggestion. Doubtless sensing the same societal need newspaper editors were

feeling about improving race relations, on July 31, he added to Peanuts a black character named Franklin.

“He

asked me about it,” Morrie said. “I said, just stick him in there the same way

you did all the other characters. Don’t pay any big attention to him.”

Franklin

arrived, but he didn’t go very far. Upset, perhaps, by the criticism that

Franklin looked like Pigpen, Schulz didn’t explore the possibilities much.

Interviewed in 1977, Schulz said: “I think it would be wrong for me to attempt

to do racial humor because what do I know about what it is like to be Black?”

Morrie,

on the other hand, knew. And Schulz had a high regard for Wee Pals and

what Morrie was doing.

“The

best thing I can say about the cartoons of Morrie Turner is that he really

knows what he is drawing about,” Schulz wrote as an Introduction to the first

(1969) paperback reprinting the early strip. “I have always been somewhat of a

fanatic about cartooning and comic strips in particular. It is my firm belief

that a comic strip needs a point of view. This is a unique profession and one

which requires total involvement on the part of the creator, for everything

that he has ever experienced must eventually, in one way or another, find its

way into the strip.

“When

Morrie draws about children trying to find their way in an integrated

community, the results show that Morrie has been more than a mere observer. Of

course, the best part of it all is that Wee Pals is a lot of fun. These

are good little characters and the sort of kids that you would have enjoyed

having in your own neighborhood when you were growing up.

“Morrie

is a credit to his profession,” Schulz finished, “—and I am proud to have him

as a friend.”

Schulz

wasn’t the only syndicated comic strip cartoonist to try to foster better

understanding among the races in his strip. A couple of years after Franklin

debuted, on October 5, 1970, Mort Walker introduced into his Beetle Bailey the

Afro-sporting Lt. Flap. And he arrived noisier and lasted longer.

Although

Morrie understood the reasons for the strip’s sudden spurt of client papers in

1968, he nonetheless was surprised at the continuing success of Wee Pals: “I

didn’t think the metropolitan daily newspapers would be interested in anything

Black,” he once said.

They

were, but he had to adjust to the restrictions often imposed by national

syndication. “There were very heavy restrictions on me,” he said. “I got behind

because they rejected so many strips.” But all those strips later made it into

print: “I just whited out the dates and changed them like it was new stuff, and

they used them,” he said with a grin.

Soon

after being rejected, the discarded strips were revived when Morrie went to

Vietnam in the late 1960s to entertain the troops there with five other members

of the National Cartoonists Society (NCS). He spent 27 days drawing more than

3,000 illustrations of service people on the front lines and in field

hospitals. And he did a lot of it in a borrowed wardrobe.

His

luggage got lost en route, and Family Circus’s Bil Keane came to his

rescue. “Bil was the closest one to my size,” Morrie said. “Everybody else was

so big. So Bil loaned me some clothes. I lived out of his suitcase for a long

time, and as a result, we became very close friends.”

That

will happen if you’re wearing the same clothes. Later, Keane added a

Morrie-inspired black kid to the cast of Family Circus.

What

with all the extracurricular sketching he was doing, Morrie fell behind with Wee

Pals, and by the time he was back home, he was in danger of missing

deadlines.

“I

decided to take all those strips that they had rejected and re-date them and

sent them back,” Morrie explained. “Well, they had no choice. And so they went

with those strips—and the roof didn’t fall in.”

BY THE LATE

1960s, Morrie was doing his strip mostly in the evenings and into the wee

hours. His daytime hours were often devoted to giving chalk talks to his

favorite audiences, children in schools in the Bay Area. He delighted

youngsters with drawings and inspired them with comic strips and stories about

people of color who made important contributions to America. In interviews with

the Sacramento Bee, he often spoke about his commitment to young people.

“I

like writing about children and for children,” he once said. “They are so

honest and forward, and they will tell you the truth.”

And

when he visited other cities, he usually arranged his schedule to allow for

appearances in local schools.

In

1969, he had another idea. Said he: “One year ago, prior to what has come to be

known as ‘Negro History Week,’ I decided to herald the accomplishments and

contributions of black Americans to U.S. history via the strip.” He quickly

discovered his own knowledge of African American heritage was “sorrowfully

lacking.” So he turned to his wife, “whose knowledge of the black man in

America was not much better than my own.” But Letha undertook extensive

research and reported her findings to Morrie.

“In

the process,” he said in an article in Cartoonist PROfiles (No.6, May

1970), “we slowly became educated and learned a new pride.”

And

they decided to share their knowledge —“not exclusively with the black child

for the pride and dignity it could give him, but mainly with the

deprived suburban white child, who, we felt, needed to be made aware of the

contributions of his black brothers. We felt it necessary that in the process

of learning, the child should be entertained or he would not digest the

lesson, therefore we decided that the Wee Pals characters were perfect

for the task.” Scraps of African American history began appearing as a final

panel in Wee Pals strips.

And

from there, the project expanded into a coloring book, Black and White

Coloring Book. Published by Troubadour Press, the book includes short

biographies of 15 significant black Americans and insightful moments of African

American history—like the founding of Chicago by a black man, Jean Baptiste

Pointe du Sable.

Morrie

was gratified and pleased with the sales of the book, and the success inspired

him to produce other booklets along the same lines as well as calendars and

other educational materials, including an animated cartoon biography of Martin

Luther King, Jr. The most notable of these efforts, however, was the

introduction in Wee Pals Sunday strips of Soul Corner.

Written

by Letha, it was a single panel history lesson, appended to the strip as a

stand-alone feature, presenting short biographies of notable black Americans.

The panel also satisfied the peculiar mechanical demands of syndicated Sunday

comic strips. All Sunday strips have a “drop-out” panel, a panel that can be discarded

in order to reconfigure a strip for publication in the smaller formats of

tabloid newspapers. For Wee Pals on Sundays, Soul Corner was the

drop-out as well as the drop-in. (A dubious accomplishment: alas, the latter

could not be achieved if the former was.)

Morrie

was “a tireless advocate for young people and a mentor to younger artists,”

Peter Hartlaub wrote at sfgate.com, “— his influence was felt beyond the panels

of his daily comic strip.”

His

lectures to school children about his Rainbow Power message earned him the

Brotherhood Award of the National Council of Christians and Jews in 1968 and

the B’nai B’rith Anti-Defamation League Humanitarian Award in 1969. In 1970, he

served as vice chairman of the White House Conference on Children. Morrie said

at the time: “I thought that just by exposing readers to the sight of Negroes

and Whites playing together in harmony, rather than pointing up aggravations, a

useful, if subliminal, purpose would be served, and ultimately would have as

great effect for good as all the freedom marchers in Mississippi.”

Comic

book writer/artist Jimmie Robinson wrote about Morrie’s influence on him (in

italics): He was a pioneer in many ways, but most of all I will remember him

because he came to my elementary school and inspired me to be an artist. Let me

clear this up a bit. I was in a school for the arts. It was a magnet

education/arts program in Oakland, California called Mosswood Arts. So it

wasn’t uncommon for the school to have various artists come in and speak to the

students. However, when Morrie Turner came to visit there was something

different. And for me it was that Mr. Turner was Black. In fact, in my three

years at that art school he was the only black adult artist I ever met.

When

he came to our class he spoke about his craft and showed us how he worked and

what his job demanded. He spoke about his newspaper comic strip and how he had

to write it every day. He spoke about the diverse cast of characters in his

strip, but he never once spoke about the issue of his race.

But

for me he didn’t have to. The fact that he, a black artist, even existed, spoke

volumes. I was living in the notorious West Oakland Acorn projects. It was full

of all the negative things you can dream of in an economically depressed inner-city.

I had to take two buses to get to the arts school — which took me to a magical

world away from the dark crime of my neighborhood. At the time I saw my school

as the end of the road for someone like me. But when Mr. Turner arrived—just by

his presence and career alone—he showed me that the world beyond my quirky

school was open to anyone — no matter the race of gender.

Morrie

can be credited with helping break ground for other black cartoonists such as

Brumsic Brandon Jr. (Luther), Ray Billingsley (Curtis), Darrin

Bell (Candorville), Steve Bentley (Herb and Jamaal), and Aaron

McGruder (The Boondocks). About the latter strip, Steve Chawkins at the L.A.

Times quoted Morrie saying: “Boondocks is hip-hop; Wee Pals is

cool jazz.”

In

1972, the Wee Pals characters and their Rainbow Power message reached

new audiences when they debuted on television in a Saturday-morning animated

cartoon series called “Kid Power” (September 16, 1972 - September 1, 1974).

During the 1972-73 season, another version of Wee Pals appeared on San

Francisco’s KGO-TV, “Wee Pals on the Go,” a Sunday morning show that featured

child actors playing the parts of characters in the strip.

And

on May 14, 1973, Morrie was on tv himself in “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.”

In

December 1987, Morrie, who probably spent more time with kids in schools than

at the drawing board, was inducted into the California Public Education Hall of

Fame, which spotlights the essential role of public education by honoring

California public school graduates who have made significant contributions to

society and the advancement of humanity. Two booklets that Morrie did for the

NAACP’s Back to School/Stay in School program were specifically recognized.

Done in collaboration with the program’s director, Aileen O. James, one of the

booklets illustrates the “Power to the Pupil” who gets an education, and the

other gives pointers to parents about how to be supportive in their children’s

education.

NAACP’s

objectives were to undermine negative attitudes about school, replacing them

with the positive philosophy that education is the main road to success, and to

seek out “at risk” students and offer them remediation, recreation, guidance

and parental involvement in after-school sessions.

When

Morrie was approached by James, he said, “I could hardly contain my

enthusiasm—or perhaps my ability to will a situation. I had already read about

the project and realized its importance, and I’d begun formulating in my mind

how I might contribute. When Dr. James called, she simply saved my calling her

to beg to participate. I have long understood the importance of education in

the fulfillment of a productive and satisfying life. I suppose that is part of

the reason I have spent so much of my time in schools encouraging, and

hopefully inspiring, kids to succeed as human beings through their pursuit of

education” (Cartoonist PROfiles, No.76, December 1987).

For

his work in cartooning and education, he received many awards and honors, among

them: the Sparky Award (named for Charles Schulz) from San Francisco's Cartoon

Art Museum; the Boys and Girls Club Image Award; Alameda County Education

Association Layman’s Award; California Black Chamber of Commerce Lifetime

Achievement Award and the Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award (from the National

Cartoonists Society); San Diego Comic-Con Inkpot Award; City of Oakland Unity

Award; and the California Educators Award. At the International Comic-Con at

San Diego in 2012, he received the Bob Clampett Humanitarian Award. He’s in the

halls of fame of Berkeley High School and the World Institute of Black

Communications. And he is a founder of the Northern California African American

History Museum and Library in Oakland.

Mell

Lazarus, the novelist and cartoonist who created the Miss Peach comic

strip (1957-2002) and still does Momma (which he started in 1970),

called Morrie’s work charming, accessible and imbued sensitively with a message

about racial equality. “It was a wonderful way to do it,” said Lazarus, a

former president of the National Cartoonists Society.

"Morrie

was a pioneer with his Rainbow Power many decades before it became a household

name," said Rick Newcombe, who founded Creators Syndicate in 1987. "I

started working with Morrie in 1984 [while Newcome was still working for News

America], and we clicked right from the beginning. He was warm, funny, gentle

and loving—one of the kindest people I have ever known."

Simone

Slykhous, the Creators editor who handles Wee Pals, agreed:

"Working with Morrie Turner has been a great honor. Despite being an

institution in the comics world, he was always incredibly thoughtful and

generous with his time. He even sent me personalized thank-you notes featuring

his iconic characters saying, '5Q + 5Q = 10Q.' I want to say a final '10Q' to

Morrie for all the laughs."

SOON AFTER 8

p.m. on November 4, 2008, just after the polls closed at the senior center

around the corner, Morrie’s phone started to ring. All the network

prognosticators were certain now: Barack Obama had been elected the 44th President of the United States, the first of his race to hold the office. And

Morrie’s friends called to rejoice with him.

Obama’s

candidacy had produced mixed feelings in the cartoonist. He was delighted that

the black Chicagoan was running, but he was terrified that he would be

assassinated before Election Day. And even that night, Morrie was sure a black

man had no chance of winning. But win he did, and Morrie’s phone rang all

night.

In The Believer magazine (No.67, November/December 2009), Jeff Chang

reported that one of those who called was Bil Keane, who wanted to share the

happy moment with his old friend. Wee Pals, Keane told Morrie, had

helped pave the way to this historic moment for America. “Morrie tried to find

the words to reply; finally, he said that it was only the second time in his

life he had ever felt like an American. Keane was about to tell Morrie that he

didn’t understand what he meant. But he stopped. He heard Morrie sobbing.”

MORRIE’S WIFE

LETHA died in 1994, and several years ago, Morrie moved to West Sacramento to

live with Karol Trachtenburg, who, with her daughter Jeannette Eagan, looked

after the elderly cartoonist.

He

continued to produce Wee Pals, meeting his deadlines with clock-like

dedication even as his kidneys were failing. His drawings were not as strong as

they once were, but the message (and the comedy) persisted.  He saw his work as an ongoing struggle

against intolerance. He saw his work as an ongoing struggle

against intolerance.

“That’s

what I’m supposed to do,” he told the San Jose Mercury News. “I think,

what am I supposed to be doing that I’m not doing? My mother used to say, ‘Cast

your bread upon the water.’ By saying that to me, it meant that I should give a

little.”

I

visited Morrie last spring with Tom Tanquary, an Emmy award-winning 40-year

veteran of television news (the last 20 years with NBC News and “Dateline”)

whose passion for newspaper comics has persuaded him to undertake a documentary

about them, their role in American life, the relationship they have with readers. Wee Pals is a stunning example of the kind of comics history we want to

tell. Morrie was in a wheelchair, as he has been for the last year or so. He

had a welcoming manner about him, a kind of gift: from his very first

utterance, you felt that he had known you all your life, that you were an old

friend not a virtual stranger.

He’d

been on dialysis for the last three years. He invited fans to visit him during

these treatments, saying, “No need to call first—just sign in, don a paper gown

and visit.”

He

wrote on his Facebook page Thursday, January 23: “Have been having some medical

issues that require surgery, and I’ll be recuperating for a bit.”

He

worked on the strip and other projects (he always had other projects) until the

next day, when he went to the hospital. And the day after that, he died of

complications from his kidney ailment.

On

February 9, a ceremony celebrating his life was held in Berkeley—in a hotel

ballroom so that hundreds of fans and family and friends could attend. Many

delivered remarks in remembrance of the cartoonist. Longtime broadcaster Jerri

Lange, a schoolmate of Morrie’s, looked over the crowd and said: “You look just

like the comic. Morrie would be so happy. There’s no color here: there’s just

everybody who loved Morrie.”

Another

speaker said: “Turner helped transform generations of children into adults with

a new and better way of looking at the world. Through your unique artistry and

personal kindness, you’ve helped show the world what we can be, should be, and

must be.”

He

is survived by his companion Karol Trachtenburg, his son Morris A. “Morrie”

Turner of Hercules, California, four grandchildren and nine

great-grandchildren.

And

by thousands of fans and colleagues. Some of the latter were rounded up by

Michael Cavna on his ComicRiffs blog at the Washington Post. I’m posting

most of them here—:

Wiley

Miller (Non

Sequitur): Morrie was a very good friend of mine for over 30 years, not

merely an NCS acquaintance. One of the kindest souls I have ever had the

privilege to know. Morrie’s influence on me didn’t make me a better cartoonist.

He helped make me a better person.

I’ll miss him

dearly.

Tom

Richmond (Mad artist and current president of the National Cartoonists

Society):

In 2003, the

NCS honored Morrie with the Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award. This is a

big deal and honors those who have had exemplary careers in cartooning and had

a profound impact on their field. Morrie certainly fit that bill. In fact, to

call him a mere “pioneer” or “legend” seems like a disservice considering what

he did for minorities in cartooning, and for the world itself with his message

of peace, tolerance and acceptance of all races, nationalities and religions.

Jerry

Scott (Zits and Baby Blues): He was incredibly kind,

genuinely interested in people, and always made time to talk with me when we

would see each other. He was a positive, accepting influence on so many of us

cartoonists when we were starting out in the business. Oh, and his laugh always

made me laugh.

Dave

Coverly (Speed Bump): I always felt that Wee Pals was so

successful because it was a true, organic extension of Morrie himself. The

optimism and idealism were heartfelt expressions of a true gentleman; he was

one of The Good Ones, and it was a real honor to share the comics page with

him.

Brian

Walker (Hi and Lois and comics historian): Morrie Turner was the

first African American to sell a comic strip with African American characters

to a major syndicate. ... The cast of his creation was from a variety of

backgrounds, providing a graphic testing ground for Turner’s belief in Rainbow

Power: “I decided that by exposing readers to the sight of Blacks and Whites

playing together in harmony,” Turner once claimed, “rather than pointing up

aggravations, a useful, if subliminal, purpose would be served, and ultimately

would have as great an effect for good as all the freedom marchers in

Mississippi.

Lincoln

Peirce (Big Nate): Wee Pals wasn’t in either of the newspapers my

parents subscribed to while I was growing up, so I discovered the strip through

Morrie’s reprint books. Even as a kid, I recognized that the titles of those

compilations—Funky Tales, Getting It All Together, Doing Their Thing, Kid

Power —signaled very powerfully that this strip was different. Unlike most

of the other comic strips or comic books I read as a child, which had a certain

timeless quality, Wee Pals was timely. It felt deeply authentic to me

because it was contemporary; these weren’t characters who’d been around since

the ’40s and ’50s. It felt very specific to its time, and it was a time I

recognized as my own. I didn’t have to run to my parents and ask them what a

particular Wee Pals strip meant. And the characters themselves were

great. Morrie did a tremendous job, in only a few strokes, of revealing just

what made each kid tick. From week to week, sometimes even day to day, I’d pick

a different character as my favorite. The fact that there were so many to

choose from points to the richness of the world Morrie created. He was a great

cartoonist.

Jim

Toomey (Sherman’s Lagoon): I’m so sorry to hear of Morrie’s passing.

I got to know Morrie when I was just starting out as a syndicated cartoonist

living in San Francisco. I would see him at the Bay Area National Cartoonists

Society events. He was always so supportive of the younger, up-and-coming

cartoonists, and was always generous with advice. Unlike a lot of cartoonists

you meet in person, Morrie was actually funny, and gregarious, and a lot of fun

to be around. We’ll all miss him greatly

Keith

Knight (The Knight Life, The K Chronicles, th(ink): He was a

gracious, nice and giving person. And he had this youthfulness. He was able to

retain that exuberance of being a kid, and keep that in his work. I had the

pleasure of interviewing him onstage a couple of years ago at the San Diego

Comic-Con. [I was] disappointed with the attendance, but it was good, selfish

fun for me. He told a very moving story about visiting injured soldiers in Vietnam.

And I was excited to see a lot of his early political-cartoon work. I came to

realize that Morrie’s done everything I’ve ever wanted to do, except he did it

50 years ago, both humbly and graciously. Easily the nicest guy in the

industry.

Darrin

Bell (Candorville): I didn’t know Morrie Turner well — I met him

only once. But I never forgot that meeting. I attended my first NCS Reubens

Award ceremony in San Francisco, in 2003, where I got to see Morrie receive the

Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award. Until the moment he crossed that

stage, I felt as if I were the only non-white person at the entire event — and

one of the few under 30. I practically was. I felt out of place. Nobody knew

who I was and worse, nobody I mingled with seemed to care—except my friend and

inspiration Wiley Miller, who wasn’t even in the NCS at the time. I wasn’t sure

I wanted to remain part of the NCS.

After

the awards banquet, I was standing in the hallway and I heard a man’s voice

from behind me say, “I saw you, young man, and I just wanted to say hello.” I

turned around and it was Morrie Turner. He reached out to shake my hand. As I

shook his, all the “Soul Corners” I’d read over the years seemed to flash so

fast through my mind that I couldn’t make out even one to tell him I’d read. So

what I told him was:

“When

I was a kid, we took three different newspapers. I learned to read by reading

the comics page. I loved to draw, but I assumed it was someplace I could never

be because none of the characters looked like me. I can’t tell you how

important it was, for me, to see Wee Pals in there every day, to see that it

was GOOD, and to see the achievements of people of color in that ‘Soul Corner’

on Sundays. Because I sure as hell never saw them in the rest of

the newspaper. I used to imagine myself appearing in one of those Corners

someday. I don’t think you can possibly know how many little kids you inspired,

sir.”

I

told him it was an honor to see him receive this award and that recognition of

his work by the NCS was long overdue. Decades overdue.

He

gave me a little hug and told me: “You’re doing something important just by

being here. We need people like you to BE here.”

I’m

not going anywhere, Morrie. Morrie Turner was the father of diversity on the

comics page, and I doubt I’d be here if it weren’t for him.

Eleven

years ago, I was considering walking out of that organization and not looking

back just because I felt as if I didn’t belong. Morrie Turner stopped me. Today

I’m the third vice president of the NCS. I wish I could meet him one more time

to thank him again. With just a few words, and just a few lines of ink and

color on the page, the man inspired me just as much when I was 28 as he did

when I was 5.

Andrew

Farago (Curator, Cartoon Art Museum): Morrie claimed he was finally

going to slow down in another year or two, once he’d done 50 years’ worth of Wee

Pals. That would have been nice, matching his old friend Charles Schulz’s

tenure on Peanuts, but I don’t think any of us really believed Morrie

would stop drawing. Or could stop drawing.

Nearly

every student in the Bay Area since the 1970s, especially in Morrie’s hometown

of Oakland, met him on one of his countless classroom visits, where he’d tell

kids stories about his life as a professional cartoonist, and as a proud

graduate of the Oakland public school system. As proud as Morrie was of his own

success, he was even prouder of all of the other cartoonists he inspired. And

doctors. And scientists. And teachers. Morrie never forgot where he came from,

and never missed an opportunity to inspire the next generation.

Even

in recent years, as his health declined, Morrie’s schedule barely slowed up. A

typical week involved three trips to the hospital for dialysis, a school visit,

a library appearance and maybe a comic book convention. And everywhere he went,

he showed up smiling and ready to share some of his favorite stories about

cartooning. Or about his friends. Or his military service. Or his school days.

Or whatever popped into his head. And each and every audience had a great time.

While

it’s sad that Morrie is no longer with us, the last several years of his life

were almost like an extended farewell tour. Everywhere he went, people were

thrilled to see him, whether it was the first time or the fiftieth time they’d

heard his stories. He received awards from the Cartoon Art Museum, the National

Cartoonists Society, Pittsburgh’s ToonSeum, Children’s Fairyland, and many

others. Some organizations made up awards just for the sake of getting one more

visit from Morrie. It’s rare that someone can do what he did for so long and

maintain an enthusiastic, appreciative audience of friends, family, and fans,

but Morrie was a rare kind of person. Morrie loved what he did, and everybody

loved Morrie. And Morrie loved everybody.

Jeff

Keane (former NCS president, who inherited Family Circus from his

father): Morrie was one of my Dad and Mom’s best cartoonist friends, and

the first time I met him, I could see why. ... He and Dad went to Vietnam with

the USO together. Dad literally shared the clothes off his back during the trip

due to Morrie’s luggage getting “lost” in transit (of course, them being about

the same size was a bonus, although my Dad’s taste in clothes was probably a

negative). It was the late 1960’s.

That

experience, I think, helped them form a bond that lasted till the day Dad died.

I know my Dad was thrilled and honored to present Morrie with the Milton Caniff

Lifetime Achievement award from the NCS in 2003. It was a most deserved award.

What Morrie did with his Wee Pals strip was groundbreaking, and his own

humbleness and continued joy of sharing his love of all people through his

cartoon was a true gift.

I

know he and Dad are probably laughing together right now. And if Morrie’s

luggage got misplaced on his way up there—well, I’m sure my Dad has him

covered.

Envoi. Musing about his craft, Morrie once

said: “Doing a cartoon enables you to step outside and look at yourself. It’s

like therapy, and I’ve become a better person for it.”

So,

we submit, have the readers of Wee Pals.

Sources. Some of my sources are cited at the

place they are quoted in the text. But many are not mentioned specifically—that

is, the dozens of obituaries and farewell articles of acclamation and affection

that flooded the Web as soon as Morrie’s death became known. I read as many of

them as I could find and picked up a piece of biography here, a scrap of

information there, and mashed it all together in what you’ve just read. A

general source for information about black American cartoonists is Tim

Jackson’s website which is temporarily offline because it’s being turned into a

book, tentatively entitled A Salute to the Pioneering Cartoonists of Color,

due out later this year.

Return to Harv's Hindsights |