THE WORLD OF COMIC ART

Looking Back through the Lens of a Pioneering Journal of Comic Art and Caricature

WE CAUGHT A GLIMPSE in Rancid Raves Opus 393 of Dororthy McGreal’s pioneering magazine The World of Comic Art: The Historical Journal of Comic Art and Caricature, and we promised a more detailed examination of its contents, which is about to take place. McGreal, as we noted, founded her magazine in 1966, preceding by two-and-a-half years Jud Hurd’s venerable Cartoonist PROfiles, which debuted in March 1969 and was for many years the only periodical devoted to cartooning. But for a year, from June 1966 until its summer 1967 issue, McGreal’s World was the only one of its kind, a precursor to Hurd’s and all the rest that surrounds us now in rapidly accumulating profusion.

McGreal’s World ran to only five issues, the covers of the first four we display

near here.

McGreal begins with the first issue to extol the historic standing of comic art. “In every country comic art has been the art of the people,” she writes, “—the only art that speaks the language of all mankind. It has raised a powerful voice in protest against tyranny, it has instructed the illiterate, for truly one picture is worth a thousand words, it has mirrored the daily life and thought of the Western world. ... Comic art and caricature have always spoken directly to the minds and hearts of all men.

“The indignation of a Hogarth, the protest of a Goya, the human touch of a Daumier, the cheerful vulgarity of a Rowlandson, the spirited humor of a Cruikshank, the sardonic jibes at human nature of a Wilhelm Bush, and the black humor of a Jose Guadelupe Posada have been clearly understood by the people. This is the distinguished ancestry of today’s comic art.”

The first issue’s cover story is about Moon Mullins, the comic strip that starred “a crude, raucous roughneck ... a goggle-eyed, rude, common character who loved girls and money, and he provided countless belly laughs with his crazy antics based on these two favorite interests.”

Invented in 1923 (debuting June 19) by Frank Willard, by the summer of 1966, the strip had been produced since 1958 by Ferd Johnson, who’d been Willard’s assistant from the very beginning. (For the whole history of Moon’s creation by Willard, see Harv’s Hindsight for August 2013.)

|

|

While tracing Johnson’s career, the author of the article, Ray Fisher, a commercial artist, also observes the changes Johnson has wrought in the strip: both Moon and his nephew Kayo no longer wear the derby hats Willard had inflicted on them. And Moon is a cab driver, which gives him topical mobility as well as employment and financial independence.

Johnson

had also cleaned up the artwork, abandoning the cross-hatching of his mentor’s

manner.

Another article is devoted to the career of Hugo Gernsback, who “has been given the respectful title ‘Father of Science Fiction’ as the one man who, more than any other individual, identified and blazed the trail for modern science fiction. To this title should be added ‘and Godfather to Science-Fiction Comics.’” It was in Gernsback’s magazine Amazing Stories that in 1928 a novelette, “Armageddon 2419" debuted, inspiring John Dille, president of National Newspaper Service, to create a comic strip based upon it—namely, Buck Rogers, written by Philip Nowlan and drawn by Dick Calkins.

Famed Des Moines editoonist, the late Jay N. Darling [“Ding”] gets the full biographical treatment as does Beetle Bailey’s Mort Walker, who said: “I sold my comic strip on the first try to the first syndicate I took it too. I didn’t even have a drawing board yet. ... I either borrowed one or used my little bread board. But now that I was doing a strip for the largest syndicate in the world [King Features], I decided it was time to get some art supplies!”

Methinks Walker is exaggerating: when he sold Beetle Bailey, he had been freelancing magazine cartoons for years and was editor of a cartoon magazine. (Harv’s Hindsight for January 2018 offers Walker’s professional biography and a history of Beetle.)

McGreal reprints a few of the “helpful hints” from The Complete Tribune Primer, a rare 1882 handbook for journalists by Eugene Field, illustrated by Frederick Burr Opper.

|

|

In “The Inimitable George” we learn that Cruikshank had a brother, Isaac Robert, who was also an artist. Together in 1820, “they illustrated Life In London, which featured the exploits of Jerry Hawthorn and Corinthian Tom, and the term ‘Tom and Jerry’ entered the language of the period as a phrase descriptive of a certain type of roistering, brawling London man-about-town. ...

“At

an early age, the Cruikshank brothers were exposed to the theater when their

[artist] father had numerous commissions to pain portraits and scenery, and the

fascination persisted for the rest of their lives. George was always the

thwarted actor, ready to sing and clown at every opportunity.  Among his close

friends was the famous clown and pantomimist Joseph Grimaldi, whose nickname

‘Joey’ has become a synonym for ‘clown.’...

Among his close

friends was the famous clown and pantomimist Joseph Grimaldi, whose nickname

‘Joey’ has become a synonym for ‘clown.’...

“As young men, the brothers worked hard and played hard,” gaining reputations for their drinking exploits, George particularly.

A long-time friend of the artist said: “He sacrificed to the jolly god rather oftener than occasionally, and surely no man drank with more fervour and enjoyment nor carried the liquor so kindly, so merrily.” ...

But Cruikshank gave up drinking in his fifties and became a tea-totaler for the remaining thirty years of his life, promoting the temperance cause.

“He became a difficult dinner guest as, when the wine was passed, he freely expressed his horror of strong drink and even reproved his host.”

The debut issue of the World, 50 pages plus cover, finishes with an article about Peanuts— “Of all the nice people in the world, it’s entirely possible that Charles Schulz is at the top of the list ... he treats even total strangers as if he had known them forever.”

Without a byline, the piece is probably by McGreal herself. Over the years, she proves a deft writer and insightful analyst of the arts of cartooning.

THE SECOND ISSUE begins with a cover story about Hal Foster and his Prince Valiant. Foster, it seems, was an outdoorsman from an early age: “Over sixty years ago, a ten-year-old boy sailed a thirty-foot boat alone in the dangerous waters off the Halifax coast. A few years later, aged fourteen, he was earning his living as a fur trapper in the Nova Scotia bush. ... From an early age, he had shown the self-reliance and love of the outdoors that were to make him one of the greatest adventure story writers of all time.”

Although Foster made other forays into the wild throughout his life (in 1917, he discovered a gold mine but lost it to a claim jumper), his career, as we all know, was spent at the drawing board. His first venture was drawing Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan; and then, the prince at King Arthur’s court.

McGreal

observes Burroughs in this issue, too, noting his life-long pursuit of

adventure in life as well as on the printed page. In his late sixties,

Burroughs did his bit in World War II as a correspondent in the Pacific. His is

“the story of a man who rose from the obscurity of a thirty-five year old

failure to become the head of one of the world’s most incredibly successful

business enterprises.”

The Burroughs segment concludes with a short article on J. Allen St. John, the artist who most often illustrated Tarzan.

Elsewhere, a short piece by Max Rafferty, California’s state Superintendent of Public Instruction, reprinted from the Los Angeles Times, praises the work of Li’l Abner’s Al Capp: “I suspect that in this pint-sized, peppery cartoonist we have an authentic, homegrown genius. His Abner is America itself—big, smiling, patriotic, decent, lovable, a little stupid. His Dogpatch, rickety though it is, shimmers green and gold and gladsome, as America did, once, before we set to work to ruin and pollute it in our own time.”

McGreal includes cartoonist Homer Davenport’s account of his boxing match with “Kid” McCoy, “the all-time light-heavyweight great.”

“The record books of boxing don’t show it, but only an ill-fitting pair of shoes, a second who snored, and a timekeeper who set each round to suit his fancy prevented what may have been the ring’s biggest upset.” Of course, Davenport lost.

Dale

Messick and her Brenda Starr strip with its mysterious romance

between a newspaper reporter and a doomed Basil St. John, suffering from some

incurable disease, take four pages, and then McGreal resumes the Cruikshank tale, focusing on George’s older brother Isaac Robert, upon whom the

spotlight of public attention fell first.  Bob Dunn, editorial cartoonist (virtually unknown today), and then “Australia’s Most

Famous Comic Strip”—Ginger Meggs —and the biography of Ginger’s

inventor, James C. Bancks.

Bob Dunn, editorial cartoonist (virtually unknown today), and then “Australia’s Most

Famous Comic Strip”—Ginger Meggs —and the biography of Ginger’s

inventor, James C. Bancks.

Bancks died in 1952 after 31 years directing Ginger’s juvenile antics (which a newspaper poll had determined was what had the most impact on the first half of the 20th century). The strip, a national institution, was taken over by Ron Vivian, who edged out others in a competition. After 20 years, Vivian was followed by Lloyd Piper (1973-1982), then James Kemsley (1983-2007; I knew him). When Kemsley died in 2007, Ginge acquired Jason Chatfield, who eventually moved to the U.S. and joined the National Cartoonists Society, of which he is currently the prez. Chatfield has the most active face; I watched his expressions during an NCS meeting a year ago and photographed him, as you can see nearby.

|

|

The 50-page (plus cover for $1) issue includes a gallery of various portraits of Uncle Sam and concludes with a long biography of Max Fleischer, whose animation studio was responsible for “Out of the Inkwell” with Koko the clown, Betty Boop, and, among others, Popeye. In fact, my own researches in this vicinity determined that it was the Fleischer Popeye that made the newspaper version by creator E.C. Segar famous.

The last article is a short visit with Ferd Johnson, who talks about the “topper” for his Moon Mullins—the short 3- or 4-panel strip that runs atop the Sunday Moon, Kitty Higgins, a mildly mischievous girl about the age of Moon’s nephew, Kayo.

CARTOONISTS have produced their own Christmas Cards since nobody-remembers-when, and in its third issue, Winter 1966-67 (58 pages this time, plus cover, still just a buck), McGreal’s World celebrates the season by reproducing several handfuls of the genre.

|

|

The history of the silent, bald-headed kid Henry is also rehearsed, accompanied by biographies of the character’s creator, Carl Anderson, and the two cartoonists who continued the strip after he retired—Don Trachte (Sundays) and John Liney (dailies). (I covered the same ground some years ago in Harv’s Hindsight for January 2010, if you’d like to flip back and refresh your memory.)

Marvel

Comics’ venture into animation for television is also covered. Surprisingly, Stan

Lee is barely mentioned.  Roger Armstrong’s mind-blowing performance

producing two comic strips of wildly different drawing styles— Ella Cinders (tight visuals) and Napoleon (exuberantly sketchy)—is discussed but his

stunning facilityis not much explored. I asked him several years ago how he

managed it, and he said, simply, “On Monday and Tuesday, I did Ella; on

Wednesday and Thursday, I did Napoleon.”

Roger Armstrong’s mind-blowing performance

producing two comic strips of wildly different drawing styles— Ella Cinders (tight visuals) and Napoleon (exuberantly sketchy)—is discussed but his

stunning facilityis not much explored. I asked him several years ago how he

managed it, and he said, simply, “On Monday and Tuesday, I did Ella; on

Wednesday and Thursday, I did Napoleon.”

No mystery. Right.

McGreal visits Chester Gould and his Dick Tracy and Gordon Campbell and his extensive collection of original cartoon art.

An article from Journalism Quarterly is reprinted: editoonist Jack Bender looks to the future of editorial cartooning and finds it dim but persists in believing that it has a future. [This was in 1966, remember.] He quotes several other cartoonists about the function as well as the future of the species.

Just before he died, Jay N. Darling (“Ding”) wrote: “Looking back over the whole history of picture-making, intended to accomplish any major diversion of the trend of thought of nations or the world in general, I find few, if any, political or social or religious trends which have been materially affected by the use of cartoons or pictures. I don’t remember any political campaigns which have been either won or lost because of cartoons or cartoonists.”

Bender is forced to admit that “it would appear that editorial cartoons have not, by themselves, ‘changed the world,’” but he then remembers Thomas Nast, whose cartoons ousted New York’s Boss Tweed. (A few years ago, Kevin “Kal” Kalaughter did a cartoon that affected some civic action or another; can’t remember the details, but it happened.)

Still, Bender quotes Edmund Valtman (1962 Pulitzer Prize winner): “The editoiral cartoon was once more dominant as an influence on political thought than now. This was during a period when newspapers held a virtual monopoly on the public’s attention and quest for news and opinions—the day when people stood in the railroad station, waiting for Horace Greeley’s Tribune to ‘know how to vote.’ That day is gone.”

Valtman goes on: “Editorial cartoons are widely printed now ... through syndication,” which “in many instances, has taken some fire from the cartoonists’ message because the result of trying to please everyone and displease as few clients as possible has been to encourage fence-sitting.”

Daniel Fitzpatrick at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch “pointed out that fewer cartoonists are now entering this field, which may cause a decline of quality editorial cartoons sometime in the future. Fewer are entering the field because such positions are scarce. At least part of the reason for fewer jobs for new cartoonists is syndication and free reprinting” which makes it easy for newspapers to find editoons without having to pay their own staff editoonist.

In other words, the plight of editorial cartooning in 1966-67 was pretty much what it is today, almost 50 years later.

Bender also quotes England’s David Low, who, on the occasion of his 70th birthday, was philosophical: “Life today is faster, longer and wider and the facilities for wasting time have improved enormously.”

Bender finishes by quoting another editorial cartoonist, Scott Long, who said: “”I believe cartoons will be with us as long as man remains man. ... I suspect that even in 1984, some poor devil with a touch of insolence will be drawing surreptitious, sarcastic pictures of Big Brother on the walls of a washroom in furtive protest against the injustice of the society in which he is forced to live.”

The creation of Hi and Lois by Mort Walker and Dik Browne is the subject of a 5-page article, and the issue concludes with a look at cartooning in Russia.

Russian cartooners explore such topics as the agricultural situation, “revealing bungling farm managers, broken-down machinery, and misplaced fertilizer. Bureaucrats, poor workmanship, and drunkenness are ever-present topics, and Russian cartoonists have their own ingenious devices for handling these themes. ...

“Soviets don’t have psychiatrist jokes and are just beginning to criticize doctors (e.g., ‘Will I live long enough to fill out all the forms I need to see the doctor?’). There are no golf jokes yet or beauty contests or gags about sex. But even the topics they leave out are revelatory of life in the Soviet Union.”

Russian art shows often include cartoons. “But it isn’t just the love of an art form, however, that makes the Russians delight in cartoons. It’s the assessment the cartoons make of everyday life and the sharp satire of everyday ills. The man in the street feels that the cartoonist is on his side.”

VIRGIL PARTCH “Vip” kicks off the fourth issue of McGreal’s World (still 58 pages for a buck) with a long article discussing his life as a freelance gag cartoonist and his eventual invention of Big George in order to become syndicated. The table of contents reveals the encompassing scope of McGreal’s intent, embracing nearly all the forms that cartooning takes in the realm of print. In addition to Vip’s foray into magazine cartooning, she’s included articles on editorial cartooning and syndicated strips, plus cartoons in the classroom, cartoon collecting, and cartoons on exhibit in museums.

Editoonist

and comic collector/historian Jim Ivey profiles a British editorial

cartoonist, Abu (A.M. Abraham), and then discusses “Cartoon Collecting from

Gillray to Goldberg”—i.e., his collection of original art and books about

cartooning.  Then Raeburn Van Buren tells us about his career as an

illustrator and why he gave that up to draw Abbie and Slats for Al

Capp. When the Saturday Evening Post started running newsy articles

and photographs instead of the fiction he’d been illustrating, he realized his

career as an illustrator was soon to evaporate so why not try illustrating in

comic strip form?

Then Raeburn Van Buren tells us about his career as an

illustrator and why he gave that up to draw Abbie and Slats for Al

Capp. When the Saturday Evening Post started running newsy articles

and photographs instead of the fiction he’d been illustrating, he realized his

career as an illustrator was soon to evaporate so why not try illustrating in

comic strip form?

Theresa Collins reports on a sailing trip she made with her husband, cartoonist Kreigh Collins, creator of the comic strip Kevin the Bold.

Oddly, the article barely mentions the historic nature of Collins’ achievement in newspaper comics. In his Toonopedia, Don Markstein discusses the “refocusing” Collins did when he converted his Mitzi McCoy Sunday strip to Kevin the Bold, going from a 20th century heiress’s adventures to the exploits of a 15th century Irish knight.

After mentioning several comic strips in which a secondary character became so popular that he/she took over the strip (Popeye, Nancy to name two), Markstein continues: But it's possible no other comic refocused quite so hard or quite so suddenly, as when the Mitzi McCoy strip was taken over by Kevin the Bold.

Mitzi had been a creation of cartoonist Kreigh Collins, who had made his name in magazine illustration. Newspaper Enterprise Association launched Mitzi McCoy as a Sunday-only strip on November 7, 1948. The protagonist was an heiress who had more than the usual amount of drama in her life. But it had been running less than two years when a couple of characters got to talking about Mitzi's 15th-century ancestor, a guy named Kevin. He was first mentioned on September 24, 1950. Next thing you know, the comic was titled Kevin the Bold.

Kevin,

a young Irishman, started out as a mere shepherd, tho a particularly handsome

and daring one. But within a couple of years, he was hobnobbing with King Henry

VIII. He even did odd jobs for Henry, the kind that involved swashbuckling

adventure with saucy wenches, haughty princesses, dashing rogues and the like,

usually accompanied by his pal Pedro and his young squire, Brett. It wasn't

quite up there with Prince Valiant, but it held on for almost two

decades, not a bad accomplishment considering how few adventure strips about

historical Europe ever made a real splash. There weren't, however, any media

spin-offs. End of Markstein’s description.

Yes, you read that right: Mitzi McCoy simply morphed into Kevin the Bold one Sunday two weeks after Kevin was first mentioned (the title change occurred on October 15, 1950, to be precise). Mitzi was re-titled briefly as Up Anchor when the heroine took up sailing, Kreigh Collins’ avocation. But the World article is about sailing, not comics; Collins, however, illustrated the article with pictures of ships that might have come out of Mitzi.

The

longest article in the issue is devoted to Milton Caniff, “a giant in his

field, one whose long shadow has touched and influenced the work of many other

artists.” The text is profusely illustrated—photographs, a whole page of the

first weeks of Dickie Dare and Terry and the Pirates, the

introductory strip for Steve Canyon, two pages of work done in college

and more of his earliest pre-college efforts than I’ve ever seen (and I wish

I’d seen this in time to include these specimens in my Caniff biography, now

out of print; so I’ve included them hereabouts).

McGreal wrote the piece, demonstrating her sure command of journalism and an occasional linguistic flourish. “At first, Terry was done in much the same style as Dickie Dare, but it blew through the newsprint like a monsoon out of southern Asia and established Milton Caniff as one of the top men in the comic strip field. His drawing, like that of most artists, underwent some marked changes as it evolved toward the now-familiar style.”

While McGreal doesn’t identifying the chiaroscuro mannerism of that “now-familiar style” (or its source, Caniff’s studio-mate Noel Sickles), she understands Caniff’s storytelling: “The continuity is all-important to an adventure strip, and Caniff’s journalism courses and knowledge of the theater have counted heavily in his favor. He combines the know-how of a novelist, the technique of a director, the angles of a cameraman, and the dramatic effects of lighting to produce the solid impact of his strip.”

As for Caniff’s patriotism, “he doesn’t drape himself in the flag and scream accusations against his fellow Americans [like the Vietnam protestors of the day]. His patriotism is expressed by honoring and keeping faith with the American fighting men who bear the responsibility of our country’s defense and who bear the burden of our uneasy and sometimes unclear and unpopular commitments abroad.”

THE COVER STORY in the 5th and last issue of The World of Comic Art (still 58 pages for $1) is about Johnny Hart and Brant Parker and B.C. and The Wizard of Id, prefaced by Hart’s “mood piece,” a narrative that fancifully demonstrates what the life of a daily strip cartoonist is like—a constant, nagging search for ideas. (For the whole story of Hart and Parker and their creations, see Opus 204.)

|

|

The lead story in this issue is about a somewhat lesser known cartoonist, Clare Victor Dwiggins (“Dwig”) written by his son, Don.

Growing up the son of a then-famous cartoonist “was a wonderful experience,” Don assures us, “and while there were the usual blind spots of the ‘generation gap,’ I was very lucky in that Dad spoke my language, for his friends say Dwig just never grew up.”

Dwig moved around a lot both geographically and professionally before hitting on School Days (later entitled Bill’s Diary), a panel cartoon about boys growing up. He did book illustration as well as cartoons, particularly towards the end of his career when he teamed with writer August Derleth on several titles.

|

|

“Hoboing” was in Dwig’s blood, his son reports.

“In 1925, we shipped out for Europe aboard a Belgian freighter, the trusty family Model T lashed on deck. To escape a record cold, we ended up at Nice, in Southern France. There, a bearded reporter for the Mediterranean edition of the Paris Tribune, James Thurber, visited us with his wife, Althea, and I remember a long afternoon listening to him interviewing Dwig over a pitcher of martinis. Thurber took not a single note, and I marveled the next day to find the story accurate.”

Another time, Thurber visited at the “Dwigwam” at Canada Lake in New York. “He walked through the screen door (at a time when his eyesight was fine) without spilling his drink,” Don remembers.

Other

articles include a report on an attorney who also does editorial cartoons, John

Duncan, a review of Jim Berry’s panel cartoon, Berry’s World, and a biography of Carl Ed and his Harold Teen comic strip, which

was launched May 4, 1919 as a Sunday strip; the daily was added later that

year.

“Ed

(pronounced to rhyme with Swede) became the chronicler of adolescence, the Boswell

of the spirit of youth, and he interpreted his subject matter with rare

sympathy and understanding. Many of the characters were drawn from memory: boys

in Ed’s old boyhood gang in Moline. There was Breezy, the fat boy; Shadow, the

sharp little opportunist; Goofy, the dope. Other types were less sharply

defined, although Pop Jenks [operator of the local ice cream and soft drink

parlor, where “gedunk” was a term that covered all sorts of edibles] also had

his counterpart in real life: across from Moline High School, a crusty old man

named Pop Walters ran a combination stationery storey and soda fountain. He was

a favorite of Carl and his pals, frequently letting them have stuff on the

cuff.”

In the strip, “Pop Jenks’ Sugar Bowl, the hangout from the Teen crowd, gave rise to a rash of Sugar Bowl ice cream emporiums across the country. Pop’s specialities included such toothsome items as the ‘awful-awful’ and ‘gedunk’ sundaes, Car Ed inventions which existed in name only—there were no ingredients.”

But proprietors of soda fountains nationwide were besieged with requests for these confections to such an extent that they wrote Ed, begging for recipes. And Ed obliged.

I

never encountered Harold Teen in its newspaper incarnation, but I saw a

little of it here and there, and I was fascinated with Shadow, the short guy,

to such an extent that I copied his face and put it on characters I was drawing

at the age of 15; I’ve scanned samples for a visual aid posted nearby.

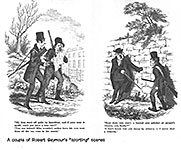

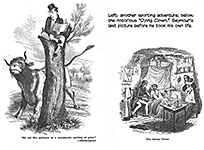

The most intriguing of this issue’s contents was a piece by McGreal on Robert Seymour, a comic illustrator contemporary of the Cruikshank brothers and John Leech.

“Seymour’s droll interpretations of everyday people deserve to be better known today,” McGreal writes. “Of these, the Cockney sporting scenes have, perhaps, best stood the test of time. The penetrating insight of his satiric jibes at the amateur ‘sportsman’ of the 1830s could apply just as easily to the heedless Nimrods and Izaak Waltons of today.”

|

|

On April 20, 1836, Seymour killed himself with his favorite shotgun. Ironically—poetically—his last drawing was for Charles Dickens’ Pickwick Papers. It portrayed “The Dying Clown.”

Speculation over the years is that Seymour killed himself because Dickens belittled Seymour’s idea out of which the Pickwick series eventually emerged. Seymour wanted to draw the bumbling amateur hunting and fishing efforts of a Cockney Nimrod Club. Dickens was to write text to accompany the drawings, but Dickens scoffed at the Nimrod Club, saying “the idea was not novel and had already been much used.”

Seymour was already brooding about his mistreatment at the hands of another writer/editor, Gilbert A’Beckett, who had founded the humor magazine Figaro. At first the relationship of the artist and the writer/editor was amiable enough, but then A’Beckett ran into financial difficulties and paid Seymour in IOUs, and when the total amounted to forty pounds, Seymour refused to draw any more for Figaro. Then A’Beckett began a series of vicious attacks on Seymour, saying, among other things, that “it is not true that Seymour has gone out of his mind because he never had any to go out of.”

A’Beckett also claimed that all of Seymours comical drawings had been based on ideas that A’Beckett supplied.

In short, A’Beckett assassinated Seymour’s reputation.

And while Seymour was suffering from that indignity, along came Dickens’ assessment of his work.

And with the second installment of the soon-to-be Pickwick Papers, Dickens changed the concept from Seymour’s to his, effectively taking the project away from its creator. “This added fresh fuel to Seymour’s smoldering resentment [over the A’Beckett business]. In his tortured mind it became a personal affront, and he become violently angry over what he considered to be an unethical and unwarranted change. ‘The Dying Clown’ was his last drawing. Before [that issue of the periodical] was published, he was dead.”

In what a poet might call a parallel circumstance, with that issue, The World of Comic Art died.

Dorothy McGreal, unlike Robert Seymour, did not die. Not, at least, with the demise of her journal. (Although she is probably resting in peace now.) But her ambitious intentions for her magazine about the history of comic art and caricature were amply and expertly exemplified in the five issues she managed to produce. However, the subscription notice in the fifth issue ($4/year for 4 issues) was, it turns out, an empty promise.

And that’s too bad. As you discern, I have the highest opinion of this magazine and wish I knew more about its creator.

Meanwhile, I have fives issues of her World and regard them as a reference resource that can be relied upon. I’m sure I’ll return to them again, from time to time.