Cecil

Jensen, Elmo, and Colonel M’Cosmic

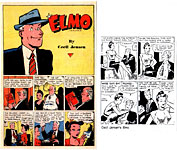

The First

Editoonist to Simultaneously Draw a Comic Strip

CECIL JENSEN,

unbeknownst to him, was one of my early cartooning idols. Because of Elmo. But Jensen, as I subsequently found out, did more than that fondly recollected

comic strip.

Jensen,

Dan Nadel tells us in his Art Out of Time: Unknown Comics Visionaries,

1900-1969, was born in 1902 in Ogden, Utah, but he spent most of his

professional life in Chicago, whence he had wended his way after graduating

high school to study at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts. After two years of

that, he worked for a variety of newspapers, including, in the early 1920s, the Los Angeles Illustrated Daily News. One day, Jensen told John Chase in Today’s Cartoon (a 1952 biographical survey of the editorial cartooning

profession), the regular cartoonist came in too drunk to draw. “I got the job,”

said Jensen.

Four

years later, he was back in Chicago at the Chicago Daily News, where he

worked for the rest of his career.

He

was the second string editoonist at the News; the first stringer was the

famed Vaughn Shoemaker. Jensen drew an editorial cartoon six days a week

(thereabouts): his cartoon appeared on the same page as Shoemaker’s. Shoes did

a three-column cartoon at the top of the page; Jensen filled two columns at the

bottom. Except on Saturday, which was Shoes’ day off, and then Cees did a

3-column ’toon for the top of the page. So—two editoons per issue: one by

Shoes, one by Cees.

Jensen

occupies a fond niche in my memory for his creation of the world’s stupidest

comic strip hero in the eponymous Elmo. Nadel supplies the tidbit that Jensen

created the strip in response to a challenge from his executive editor, Basil

(Stuffy) Walters, to whom Jensen had confided that “the comics in the News smell.” To which Walters responded: “All right—you draw a strip.” And so Jensen

did.

The

late Ed McGeean, a cartoonist friend of mine who worked at the News for

years, once told me that Shoes had no faith in Cees’ creation: he told Jensen

that Elmo wouldn’t succeed because the protagonist was too stupid. Maybe

Shoes never heard of Li’l Abner. Then again, Elmo was stupider than Abner. When

asked how Elmo would be different than other comic strips, Jensen retorted:

“The strip is supposed to be funny.” And I thought it was, hilariously so.

Elmo started October 28, 1946, and then in

1949, Elmo was supplanted as the star and lost title billing to a moppet named

Little Debbie. The strip continued under that title until 1961. Elmo was a

sort of urban Li’l Abner—except that Elmo was dumber than Abner. I admired this

kind of stupidity in a comic character. And Elmo made it all seem so easy, too—smiling

his bland, ear-to-ear grin the whole time. I loved it. I copied Elmo’s jaw and

grin in the lead characters of the comic strips I concocted in my bygone youth.

Elmo

spent most of his career working in the office of a breakfast cereal

manufacturer. Elmo actually owned the company. The previous owner, oppressed

by the responsibilities of being a millionaire and owner of a major company,

was about to jump off a bridge to his death when he was interrupted by Elmo.

Elmo, as we can see in our first visual aid (selected from the second week of

the strip’s run), suggests that the millionaire’s problems would evaporate once

he’d been swindled out of his fortune. The plutocrat, impressed by Elmo’s

irrefutable logic, gives all his fortune (stock in the cereal company) to Elmo,

saying that now Elmo will have to commit suicide.

That,

like most of what Elmo attempts, doesn’t quite work out as Elmo intends.

Eventually,

Elmo returns to his job at the cereal company, now as its owner. He is, of

course, too stupid to know that the owner of the company should be giving the

orders. Instead, he takes orders from the Commodore, an unscrupulous robber

baron who is running the company at the time. The Commodore, seeking to get

Elmo occupied with something to keep him out of his, the Commodore’s, hair,

hires a movie star to work as Elmo’s secretary. This is Sultry. And she is.

Meanwhile, perky Emmaline, Elmo’s girlfriend from back home, gets wind of all

this and comes to the big city to keep an eye on things. About this time, cute

Little Debbie shows up and becomes the face on the cereal box, selling billions

of bushels of cereal. The portion of Elmo that’s reprinted in Art

Out of Time comes from the one-shot Elmo comic book of 1948, which

completes the introductory sequence of the strip, and Little Debbie shows up at

the end of the book.

You

can’t keep a good sales girl down. Little Debbie took over, as I said,

elbowing Elmo off the marquee of his own strip. But by then, Elmo had

dropped out of the Denver Post, my hometown paper, and so I lost track

of the whole thing.

Jensen

may have been the first editorial cartoonist to produce at the same time a

syndicated comic strip although for much of Elmo/Little Debbie’s run he

produced only one editorial cartoon a week. But he was noted in Chicago circles

for another creation. Colonel M’Cosmic. Colonel M’Cosmic was vaguely

reminiscent of David Low’s fatuous Colonel Blimp (see Opus 202). But

Colonel M’Cosmic was celebrated in Chicago for his resemblance to another

fatuous pseudo military man, Colonel Robert (“Bertie”) McCormick, publisher of

the Chicago Tribune, the powerful rival of the Daily News.

McCormick

had received his commission as a colonel when he joined the Illinois National

Guard on the eve of World War I. It was a rank he earned solely by reason of

his political position as publisher of the Tribune, but McCormick so

loved the title that he retained it ever after. He had virtually no combat

experience during the European adventure and no military training to speak of;

but he fearlessly offered his opinion on military matters on the editorial page

of the Tribune whenever the subject came up on the paper’s news columns.

And he regularly harangued a radio audience from the pulpit of station WGN, the

station owned by the World’s Greatest Newspaper (as the Colonel modestly

denominated his newspaper).

The

Colonel offered his opinion fearlessly on all manner of subjects. So varied

were these subjects that the Colonel could well be imagined the world’s

foremost authority on every subject. But military matters—and war—were his

specialty. That and geopolitics generally. All during the 1930s, McCormick

lectured the world on the dangers of Nazism. In these editorial lectures, he

displayed, as his enemies were fond of saying, “one of the finest minds of the

fourteenth century.”

When

war broke out in Europe upon the German invasion of Poland in September 1939,

McCormick quickly proclaimed that “this is not our war.” The British and the

French were thoroughly competent to fight it without American assistance. In

his editorial cartoons, Shoes and Cees ridiculed McCormick and other

non-interventionists for the nativity of their views. But McCormick remained

resolutely isolationist. Until Pearl Harbor. Then the Trib was

resolutely bellicose: “We have only one task,” the paper blared, “and that is

to strike with all our might.”

Despite

this stance, McCormick continued to be critical of the government’s conduct of

the war effort and other related matters. His criticism was viewed in some

quarters as treasonous. One Chicago citizen, Jacob Sawyer, even wrote the

Colonel a letter, expressing the fear that the Tribune’s editorial

pronouncements were undermining the morale of the country. To this, McCormick

responded with a letter that eventually found its way into print in the Daily News.

McCormick

began by pointing out that Sawyer was making a mistake in believing the

powerful propaganda circulated by McCormick’s enemies. What they saw as a

campaign of hatred was actually, the Colonel said, “a constructive campaign

without which the country would be lost.” And then he went on to cite his

credentials as savior of his country by regaling Sawyer with a list of his

accomplishments in the military. “You do not know it,” McCormick rumbled, “but

the fact is that I introduced the ROTC into the schools; I introduced machine

guns into the army; I introduced mechanization; I introduced automatic rifles.

...” And so on in this vein. A remarkable display of ego, bombast, and

pomposity bordering on megalomania. And when the Daily News got its

hands on this epistle, it published it with unmitigated glee.

And

on March 25, 1942—the U.S. now plunging into hostilities in Europe and in the

Pacific—Jensen produced a cartoon to celebrate the occasion, showing Colonel

M’Cosmic surrounded by other Colonel M’Cosmics, all claiming firsts in one

military milestone after another. M’Cosmic appeared periodically in the pages

of the News thereafter, each time commemorating another of McCormick’s

pontifical pronouncements. Several of Jensen’s achievements appear hereabouts.

(A couple of these appeared in Opus 205, wherein these paragraphs first

appeared several years ago in a slightly less garnished form; I’ve since found

others of the famed M’Cosmic series, which I’ve included herewith. And I’m

repeating the text from Opus 205 because I don’t want Jensen’s historic

achievement to be lost in the welter of Rancid Raves, the ongoing and

untrammeled chronicle perforce; better here, in the “history” department.)

|

|

Genius

is in the details. Notice the hilarious accouterments: M’Cosmic wears a WWI

helmet and spurs (the mark of his stature as a cavalryman, the only kind of

officer to be, forsooth) and around his neck, a pair of binoculars (another

mark of elite officer status). Always, M’Cosmic is accompanied by a round-headed

kid, a juvenile doorman (judging from his uniform)—the M’Cosmic Grenadier, no

doubt.

So

that’s the story of Jensen’s other triumph. When John S. Knight bought the Daily

News in 1944, he told Cees to cease and desist: Knight wanted to make friends

in Chicago, not enemies. And so Colonel M’Cosmic faded away, like the old

soldier he was, to be exhumed occasionally, as he is here—fondly, wistfully.

Thankfully.

Return to Harv's Hindsights |