DICK LOCHER’S DICK TRACY

Life Backstage with an Icon

On Sunday, March 13, the last Dick Tracy drawn by Dick Locher appeared in the nation’s papers. After 28 years drawing and/or writing the iconic cops and robbers comic strip, which turns 80 next October 4, Locher is taking the rest of his life off. Born just two years before the cleaver-jawed sleuth, Locher, who has Parkinson’s, told Michael Cavna at Washington Post ComicRiffs blog that it’s time to move on; he plans to do “normal things” with his family, to travel and to paint the American Southwest. My adventure with Locher transpired in 1994, when I interviewed him and he talked about producing one of the most famous comic strips in the world. The occasion of Locher’s retirement affords a suitable moment for posting the interview, which we’ll get to in a trice. But first, a little background by way of orientation.

Tess Tracy nee Trueheart filed for divorce from her ever-sleuthing husband Richard on February 7, 1994. All across the land, brouhaha broke out in the so-called news media: it was as if the law and order icon was being somehow defrocked, leaving laws in complete disarray—that is, dis-ordered. Dick Locher was then drawing Dick Tracy, and when I met him at the Popular Culture Convention in Chicago that April, the infamous divorce was still in process. I asked him if I could come and see him sometime to discuss this shattering development. It was several months later before we finally got together on July 6 in his office in the Tribune Tower to which he resorted more-or-less daily to produce an editorial cartoon for the Chicago Tribune and its syndicate. By then, Tracy and Tess were reconciled, but the scandal was still fresh enough to justify an interview.

In the summer of 1994, Pulitzer-winner Locher had been editooning for over 20 years, longer than he’d drawn Tracy. And Tracy wasn’t his only experience at syndicated stripping: for a short while in the late 1940s after he got out of art school (and before enlisting in the Air Force, where he was a test pilot), Locher had assisted Rick Yager on Buck Rogers. And just before he inherited Dick Tracy, he had been working with Jeff MacNelly, the other Tribune editorial cartoonist, on a topical commentary strip called Clout St., which he left soon after starting work on Tracy. Locher inherited the drawing job on Dick Tracy when Rick Fletcher died in early 1983. Fletcher and Max Allan Collins had been doing the strip after its creator, Chester Gould, retired in 1977. Locher continued with Collins until 1993, when the syndicate elbowed Collins out of the picture and hired Mike Kilian to do the writing. Kilian was a journalist by day, and by night, the author of a series of mystery novels set during the Civil War.

Locher's

connection with Dick Tracy goes back to 1957, when he began a

four-and-a-half year stint as Gould's assistant. When they parted in 1961,

Locher set up his own art agency in Chicago, which he operated until 1972, when

he was hired by the Chicago Tribune as editorial cartoonist to replace

the retiring Joe Parrish. At the time, Locher had no experience at

editorial cartooning, but Gould recommended him, and he got the job on the

basis of Gould’s say-so and fewer than half-a-dozen sample cartoons he’d

produced overnight to show at his interview.

When I arrived in his office on July 6, Locher was at his drawing board, finishing that day’s editorial cartoon. He was correcting a misspelled word and muttering: “Was it Lincoln? No, it was Mark Twain who said it’s a damn poor individual who can’t spell a word more than one way.” After he fixed the error, we talked about Dick Tracy’s divorce and a number of other topics, relevant an irrelevant, as follows:

Harvey: What I wanted to find out more about was the Tracy divorce circumstance. Here's this American icon, Dick Tracy, and you and Kilian decided to subject him to something horrendous. Can you tell me about that?

Locher: Most comics are two dimensional, height and width. The third dimension is the story. Or the character. That's the third dimension. And that's what people read. They couldn't care less about how flat it looks. But we thought, Hey—let's give Tracy a fourth dimension. He bleeds. He uses deodorant. He hurts. He cries. He had taken his job for granted for so long that he didn't think much about Tess. And this came after the fact. We found a statistic: in New York City, the divorce rate among policemen is 85%. And that's extremely high. That's not bad. Let's give another side to Tracy that nobody's ever seen before: the fact that he can be hurt, emotionally. And if he is thinking about his wife, will it jeopardize his job. Will criminals be able to take advantage of him. That's something Gould had never done in Dick Tracy. Nobody's done it. Criminals taking advantage of Tracy—because his guard was down. So that was the reason for it.

We never thought it would get any media play at all. [See Footnote at the end.] We thought a few old die-hards will call in and say, Are you nuts? Are you crazy? What are you doing to Tracy? But it didn't work out that way. USA Today picked it up first and put it on the front page—What? Tracy Divorced! And from then on, it just grew. Newsweek picked it up. We ended up on sixteen tv stations and five networks. As a matter of fact, right here in this room, Katie Couric taped an interview for the “Today Show.”

NBC called up and said, We'd like to interview you about Tracy. Okay, fine. They said, The only time we can do it is 7 a.m. on Sunday morning; will you be available? Seven a.m. on Sunday morning! So I got here at 6:30 a.m., and they were here. They'd flown in on a red-eye. They went back out on a noon flight. Unbelievable what they'll do. It's incredible. But we had a good time.

Harvey: When you're developing a story like this, you and Mike Kilian, do you sit down and ]talk about it?

Locher: We talk twice a week. On Mondays, we do story for the week. And on Thursday or Friday, we'll talk again and say, How did we do? How's it look? Real simple.

Harvey: When you say you do story, you're talking about writing dialogue.

Locher: Yes. And theme. Theme first. We have a general theme that we've discussed before. We get together about three or four times a year, face to face. I go to Washington, or he comes here. And we sit down and write out two or three themes that we'd like to pursue. We don't do anything else. We each go our own way. And then we stack up stories behind the themes—intricacies, sidetracks. We compile folders, story ideas, for each theme. And then when we get together, we'll say, Hey—which one shall we go with? We pick one. And then, we'll start writing. And then also in there is the question of length—how long should the story run? We're finding out that some of them that are short are very enticing to people. And then we find out that if it's too short, people get mad. They say, We didn't get to know the characters. So that's the down side of a short story. The down side of a long story is that you can lose the readers' attention.

Harvey: Do you real feel that you are losing their attention? Do people write in and say, You lost me on that one. Or, I stopped reading that three weeks ago.

Locher: No, not really. But what happens is that people write in and say, I missed a week; what happened? And I don't want that to happen. I want the story to be good enough that they don't have to write in; they follow it every day, regardless.

Harvey: The reason that I ask is that the theory—which took shape in the fifties when television started being big competition and editors were saying, Well, you've got to have a story that's short because people can get an adventure on tv in a half-hour, so you've got to have a nine-week story or a three-week story or something like that. And I wonder if there really is any truth to that. If that isn't just editors' imagining things. These really are two different media here.

Locher: They really are.

Harvey: You can't clip out an episode from tv and put it on the refrigerator door—that was Chet Gould who said that, by the way—and you can with a comic strip. They are two different things.

Locher: Absolutely.

Harvey: So I wondered if you ever really have any evidence—if anyone has ever got any evidence—that the reading public's attention span is so limited that it can't follow a long story.

Locher: None that I've seen. However—newspapers are confronted with the fact that people under thirty don't read much.

Harvey: Hmmm.

Locher: People under thirty don't buy newspapers much. They get their fix on the news with the tv news the night before. And they read headlines. You talk to anyone under thirty and ask them what's going on, they'll give you a headline in response. And they'll have an opinion, but it won't be in depth. And the newspaper gives you the story in depth. Now, an editorial cartoon is an entirely different thing. This is six seconds worth of information right here [holding up his editorial cartoon for the day]. I think that's why it survives in the paper today. Young people gravitate to it real fast.

Harvey: That's interesting because not only is the editorial cartoon surviving, it seems to be thriving. [A situation that has dramatically changed in the opposite direction since 1994, the time of this interview.]

Locher: Oh, absolutely.

Harvey: There are more editorial cartoonists these days, it seems to me, who are full-time employees at a single newspaper and are incidentally syndicated than I think there's ever been.

Locher: Yes, yes.

Harvey: Until you go back to 1915 or something like that.

Locher: In the late sixties, it was way down. There was nothing happening. It was dead. Cartoonists would do cliches. They'd label everything. And their work could have been short columns. And all of a sudden—I’d say in the early seventies, first part of the seventies—young cartoonists started coming up. And they changed things. Their work was cutting, sharp.

Harvey: What were they doing different?

Locher: They took the labels off for one thing, and they went to the joke. Went to the one-liner. The Mike Peters style—

Harvey: Pat Oliphant.

Locher: Oliphant, exactly. A real pioneer. And people took to it. It was just waiting to happen. But the real point to make is that each feature is distinctive in its own way. We find a lot of 10-12 year olds, who are discovering the comic strip. Incredible. Young people will write in and say, We just found Dick Tracy—what's he been doing? what's his job? The sort of thing. And who is the character, Puttypuss, for example. Real primitive hand-writing. Incredible. The old die-hards, we figure they'll always be around—people over fifty, who grew up with Dick Tracy. They're the first ones to write in. But this discovery by these new kids. Simply a delight.

We won't get young marrieds at all. Marketing surveys on Dick Tracy show no young marrieds. About thirty, it starts to pick up. But from age twenty to thirty, that's when they read For Better or For Worse, Calvin and Hobbes. But that's the nature of each individual cartoon strip. If we were all alike we'd have the same readers. And we don't want that. We want a vast spread. Dick Tracy covers this area; Brenda Starr covers this area—which is great. That's the way it should be. We're in a very strong market here.

Harvey: You mean Chicago?

Locher: Yes.

Harvey: Why is it strong here as opposed to somewhere else?

Locher: Strong here as opposed to Omaha.

Harvey: Commuters reading on the train?

Locher: Just the size. New York City is Tracy's biggest area—by far. Incidentally, we're in Japan now. And Australia. But people go gravitate to a good story. The art of storytelling in my opinion is lost. You don't hear people tell stories any more. They're too busy.

Harvey: I think you might be right, but I also think that the hook is always there. People love stories.

Locher: Absolutely! They love stories. But there aren't people around to satisfy them, to give them stories. The story strip was probably presumed dead for a long time. But it isn't. Because people still like stories.

Harvey: I've noticed that the Dick Tracy strip—there are two kinds of things going on, but the over-all heading is Simplification. There's a whole lot less verbiage in the strip now than there was even six, seven years ago. Obviously, that's deliberate.

Locher: Oh, yes. It reflects the among of time people are willing to spend on the strip. We're finding out now that a lot of people are turned off on Calvin and Hobbes. Have you seen the size of the speech balloons in that strip lately? Huge. Nobody reads that much. Unless they're die-hards. And there aren't too many of those. That's a fine line to walk—the amount of verbiage. If you don't put in enough, people don't feel satisfied. Or you ruin the story. Can't tell a story without some words.

Harvey: And the more you cut down on verbiage, the less—the old method used to be to repeat in the first panel of each day's strip something from the previous day to remind people what had happened—and there's not very much of that in Dick Tracy now.

Locher: No, no. You can do that if you simplify the verbiage. We still re-cap on Sunday. You have to because a lot of people just buy the Sunday paper.

Harvey: That's another problem, of course. I wondered how—I only see the dailies. I see them in that weekly paper, The National Forum [since defunct]. And I take it because I get editorial cartoons and a lot of strips I don't see otherwise, but, boy, do they shrink the strips. I can't understand it: here's a whole newspaper devoted to comic strips, and they run them the size of postage stamps.

Locher: Oh, that hurts.

Harvey: And a lot of times, to make the strips fit, they'll squeeze the strips into narrower space—or expand them horizontally, distorting the pictures.

Locher: Hate to see that happen.

Harvey: But—to get to my question—the seven-day continuity, with the same story running all week, the Sunday has to be done 4-5 weeks before the dailies are done—

Locher: Yes, traditionally, but that's getting better because of the computer. We get 132 colors we can use, but we don't use many more than 25. And they're all numbered, all keyed, all keyed into a numbers system. All they need is a black-and-white drawing and the numbers.

Harvey: So it used to be you did dailies four weeks in advance of publication and Sundays ten weeks, and that's not true any more?

Locher: No. Six weeks for everything.

Harvey: Is that right? I used to imagine that the Sundays had to be done as the trail blazers of the story: they sort of laid out bread crumbs of plot along the way, and then the dailies had to come along and pick them up. [The metaphor was Milton Caniff’s, I think; or maybe Al Capp’s.]

Locher: Yes, yes—exactly right. And that's a good way of putting it.

Harvey: But that's no longer true. You can do the whole story straight through, six weeks out, Sundays and dailies.

Locher: Oh, yes. We do them all at once.

Harvey: Boy, that must simplify things.

Locher: Oh, yes. But unions were a part of that problem. Because all that stuff [preparing color plates] was done by hand. Yes, it used to take 8-10 weeks to get color. And Doonesbury is done three weeks out. My contract says six weeks and it's never changed. I like to be that far ahead. And so do they—the syndicate loves it!

Harvey: Well, I don't know. I imagine it is easier to live with a weekly deadline if you're at least up to the deadline or a little bit ahead. You could feel like you aren't being driven.

Locher: You don't like that old fear factor. Like the two-thousand-year-old man, who was interviewed and asked what the main form of transportation was back in cave-man days—Fear, he said. [Laughs] I'll agree that better stuff comes out of tight deadlines. Some writers don't write that way. If they can't compile it over a year's time, they can't do a book. And some of them have three books going at a time. But you can't do that with a daily comic strip. You've got to jump on it all the time.

Harvey: Let me come back to something you said earlier—you said the first thing you and Kilian do is to dope out some themes. Give me an example of what you mean by a theme.

Locher: Revenge. Hardcase Harry, who was getting out of prison and said he wanted to get Tracy. We just picked the word revenge to start with. Then we pick a character. Then we pick a story. Bearing in mind that Tracy is always in danger. Then we wanted do one with a bunch of clues. We just wrote the word clues. Sherlock Holmes was great with clues. Let's have Tracy find clues and put together the solution to the crime. We did that with Pig E. Bank. The clues were on the currency. The clues on the currency evolved after we had settled on just the notion of clues. Another thing might be lets bring back an old character. Here's the grandson of a famous crook. Nothing new in that; that's been done. But people love it. It works.

Harvey: So you come up with a theme like revenge, then a character—a crook—then the two of you go away and brood about it for a period of time, you mentioned file folders—you put scraps of paper with notes on them into the folders—

Locher: Yep. Carry a pad of paper with you, think of something, jot it down, drop it right into that folder.

Harvey: And then when you get together again, you pull out the folders—

Locher: Pull out the folders, we sit there at a nice restaurant from one o'clock until four, and we pull out little pieces of paper, we add new ones until we have a story. And it really works. Kind of a funny way to develop a story, but it works. Writing is the key. And after that is the character. It's not easy. If it were easy, everybody'd be doing it.

Harvey: And when you come up with a good character, it seems a shame to put him in jail after six weeks and forget about him—

Locher: [Laughs] Yes, or kill him off. When you have a good one, you want to hang on to him. Let him escape. He was never caught.

Harvey: So you dope out a story that's going to last a particular period of time, you know that there are certain incidents that will take place, who the characters are, maybe even how it's going to end—and then, once a week you get together and dialogue the strips?

Locher: Right. On Mondays. On the phone. I might say, Too many words in panel one; can you cut it back? Do it right away. He'll say, Dick, could I have a bird's-eye view in the first panel for what I'm trying to do? Works out really well. I worked for Gould for four years, and Monday was nothing but story. We never put pen to paper on Monday to draw. We wrote the whole week's strips on Mondays. Get Tracy into trouble. Then try to figure out how to get him out. Mike, being an author, had never worked that way, but he seems to like it. But now he says, Let's put Tracy's ass in real jeopardy. Find out what's the worst thing that could ever happen, and then work backwards.

Harvey: Get him in trouble, and then try to get him out—

Locher: Yes, it's fun. Fun to do. Very satisfying. And the letters that come in, some are good and some aren't. Some say, Gee, are you nuts? What are you trying to do? And others say, Oh, boy, that was great; could you do that again some time? You don't do your strip because of the way the letters come in.

Harvey: Caniff once told me that if he got a letter that indicated a reader had figured out how the story was going to end, he'd change the story.

Locher: Is that right? He would change it?

Harvey: He'd try to—if he had enough time left to do it.

Locher: I would do it if a bunch of people wrote in. Maybe not for just one, though. But if there were a group, I would do the same thing. If it looked so obvious. It's like the old carnival: you put up a gawdy colored sign, Come in and see the two-headed lady. That's exactly what we're trying to do. [Harvey laughs] And when they come in here, we don't want to disappoint them. If the two-headed lady is a character, we'd better have her here. And all the more power to ’em. Let's give ’em their dime's worth. If we have to blow a whistle, use smoke and mirrors, then let's do it. Let's get ’em in here.

My favorite story of all time is that one about the old Russian soldier in the field hospital. Laying there in bed. There was only one window. And his bed was next to it, so his job every morning was to describe what he saw out of the window to the rest of the patients in the ward who didn't have a window to look out of. So every morning, he'd start out—Aw, the grass is pretty today. The sky is so blue. Well, everybody wanted that bed so they could see out. Finally, the fellow in the bed next to the window died, and the next fellow got the bed. So he looked out, and there was nothing there but a blank wall. [Harvey laughs] And that's what we're doing: we're making something out of nothing.

You say Dick Tracy to anybody in the United States, and they know what you're talking about. They may not have read the strip, but they know who Dick Tracy is. Like Kodak. Like Kleenex. You might not use the product, but you know what it is.

Harvey: How does it feel to be the steward of an icon? You're holding his fate in your hands.

Locher: Yes. You really are. And it's a weighty, hefty thing. This American icon. It's like if someone took Grant Woods' American Gothic and made a comic strip out of it, if everyone agreed—you've still got to protect it. The syndicate looks at everything we do, and they look at it with a pretty critical eye. You have to use a political eye, a commercial eye—and with a storytelling eye. There's competition out there. To have been around for 63 years, that's pretty good.

Harvey: You were doing editorial cartoons at the Tribune when you were asked to do Dick Tracy—and I think I have the sequence here—but prior to that, you had worked for Gould. Is that it?

Locher: Yes, I left Gould in 1961 and started with the Tribune in 1972. About ten years. We used to have lunch together regularly. And those weren’t short lunches [he laughs]. We’d get together at noon and probably break up around 3:30 or 4 o’clock. We talked about the good old days, and what fun we had when I was working with him, and all the things we used to do. Like the machine gun episode. Do you know that story? [Harvey shakes his head, No.]

We had to draw a machine gun one day. Gould said to me, “Up on the top shelf there in the closet there’s a German paratrooper’s gun, and you might want to put that in the strip.” This was a Monday evening, just as we were getting ready to leave the office. He said, “Why don’t you wrap it up and take it home with you so that you can include it in Tracy?”

I climbed up and there was the gun, with clip but no bullets, and a police department tag on it. I imagined that he had gotten it from the police department to use as reference, long before I started to work with him. I wrapped it up in brown paper, got my briefcase full of drawings, and said, “Goodbye,” commenting that I’d see Gould on Wednesday out at his place in Woodstock [where Gould worked every day of the week except Mondays and Tuesdays, when he went to his office on the 26th floor of the Tribune Tower].

I left the building and was walking toward Union Station, and when I was about a hundred feet out of the door, I heard someone say, “Sir!” Out of the corner of my eye I could see a police car nearby. I kept right on walking, and I knew these eyes were staring at the back of my head, but I kept going. Then I heard, “Sir, I’m talking to you.”

All of a sudden, I was grabbed by the arm—gently but rather firmly—and a voice said, “Have you got a minute?” I said I was rushing to catch my train [to Naperville, where he lived], and the voice said, “This won’t take but a minute—would you step over to the police car.”

“The officer said, “What’ve you got in the package?”

“Leftover pizza,” says I.

“Would you show it to us?”

I thought this was ridiculous and that I ought to tell him the truth and take whatever was coming to me. I unwrapped the package.

“Sir,” said the cop, “you know you can’t carry a machine gun around on the streets in Chicago—that’s totally against the law, and we’re going to have to take you downtown.”

I said, “Let me explain.” And then both officers started laughing. Gould had called the police department and told them I was coming out with this machine gun in a brown paper bag. [They both laugh.]

Anyhow, I got this editorial cartooning job with the Tribune because of Gould. Joe Parrish, who was the reigning cartoonist at the time, retired; they had mandatory retirement at the time. And Gould called me up and said, Joe Parrish is leaving; get your ass down there with some editorial cartoons. And I said, I've never done any of those. And he said, Do me a favor and do about twelve of them and take them down there. Twelve! In one day! So as a favor to Chet— I had a good business going at the time out in Oak Brook, sales promotion, and we had great accounts: we had Standard Oil, Allis Chalmers, McDonalds, Cessna Aircraft—I stayed up and did twelve cartoons. Did seven. Couldn't do twelve if I had to. Brought ’em down here and they hired me. And it worked out all right. I sold my company to my partner five years later.

Harvey: Judging from that alone, you must've really rather have been a cartoonist than a commercial artist.

Locher: Yes, except that the commercial art we did was mostly cartoon.

Harvey: Oh, great.

Locher: We did cartoon instruction manuals for Allys Chalmers. Things like that. But do I have any regrets? No. If you look back, you tear yourself apart. You don't do that.

*****

ANOTHER OF LOCHER’S favorite stories is about the time he had lunch with fellow editooner John Fischetti and Chicago’s most celebrated landmark, columnist Mike Royko. Locher didn’t recount this yarn during our interview, but he told Kathy Millen at the Naperville Sun when she interviewed him about his impending retirement. Here’s Millen telling Locher’s story:

During his early days at the Chicago Tribune, Sun-Times cartoonist John Fischetti, whom Locher had never met, invited him to lunch. He joined Fischetti at a nearby restaurant and was excited to learn that columnist Mike Royko was going to join them.

Royko arrived and welcomed Locher to the Chicago journalism cabal. They had lunch and chatted. All was going well until Royko casually remarked that Fischetti’s cartoon that day was awful. Fischetti responded that his work didn’t stink as often as Royko’s did. Tempers flared as they continued to trade insults, and Locher reconsidered his choice of profession.

“Mike said, ‘John, you are finally getting to me,’ and he picked up a hard roll and threw it at Fischetti,” Locher recalled. “John then grabs Royko by the tie and drags him to the front door. When they got to the front door, they turned and waved to me as the waiter brought the check to our table.”

Royko and Fischetti exited, and Locher paid the bill.

End of story; now back to the on-going Q&A.

*****

Harvey: So you came here and were doing editorial cartoons. How did the Tracy opening occur?

Locher: The guy that was doing it, Rick Fletcher, died. He’d been Gould’s assistant. Died right at his drawing board. That was 1983. And the syndicate said, We can't let any water back up behind the bridge here, and asked me if I would be interested. And I said, I already have a job. I said, No, no. I didn't want to give up editorial cartooning. The week before, I'd won the Pulitzer. I didn't want to give it up. [Grins] Right after that. And they said, Well, take it on anyway; we'll get you an assistant. So, I did.

Harvey: Do you do an editorial cartoon every day?

Locher: Yes—five a week.

Harvey: So what's your routine for the week.

Locher: Editorial cartoon in the morning. Get up at about six thirty. Work ’til noon. Then do Dick Tracy in the afternoon.

Harvey: When's your deadline for the editorial cartoon?

Locher: One o'clock. It's liveable. I have an assistant. The only squeeze is trying to get the best damn story out in the allotted time; that's the squeeze. And you can't blame the deadline. Deadlines are going to be there whether you like them or not. They're gonna be there. If you don't like them, you'd better retire. Self discipline. A lot of times you look at the strip and say, Is that the best I can do? I guess as long as that prevails, we'll be all right. But—damn, it's frustrating when you get a week's worth done, and you see something that you could have put in there that would have made it. That's frustration. Oh, if I only—. That hurts.

Harvey: One of the reasons that Caniff was always just right up to the edge of his deadline—and I'm sure sometimes he missed it—was because he was waiting for something to happen—some little edge that he could throw in at the last minute that would prove that this strip happened just yesterday.

Locher: Yes—that's important!

Harvey: I read a report from his doctor, report on an annual physical, and the doctor made this observation. His patient told him that the reason he was behind on his deadline was that he was hoping for something amazing to turn up that he could incorporate into the story that week.

Locher: You don't want anybody to get ahead of you. I want to be the first with that idea. If you can—then you've got something going. And that's kind of nice.

Harvey: What kind of responses did you get from readers about the divorce thing?

Locher: We got a lot. Mixed. Fifty-three percent of Tribune readers are female. And we got a lot of really positive response from them. The old die-hards thought we were out of our minds. Tracy getting a divorce? And Tess? Tess Trueheart? Tess Trueheart is Tess Trueheart—the name says it all. You don't mess with that. You don't mess with American Gothic. Well, we did it: we messed with American Gothic. And we caught hell from some people. But the pluses outweighed the minuses.

Harvey: And the pluses—let's say, many of them were from women—and they were saying, It's about time Tess woke up.

Locher: Exactly right. They blamed a lot of it on Tess. Really interesting.

Harvey: How did they do that?

Locher: They said, Why doesn't she understand what he's going through? And that was a surprise. One caller on the phone said, It's about time he divorced that old bag. She's nothing but an anchor around his neck. [Laughter]

Harvey: Tell the Dan Rather story.

Locher: I was looking up at that clock. It was after five o'clock. I never like to answer the phone after five o'clock: it's never good news. [Laughs] It rang and rang, and I picked it up, and it was Dan Rather. He said, I want to be the first to know when the reconciliation happens. I said, Okay.

I have a very good friend, Paula Zahn, who is also on CBS, and she wanted to do a show, five minute segment on the morning show, on what changed Dick Tracy's mind, and what changed Tess's mind. And she thought that if I sat in the chair and played Tracy and they got an actress or model to play Tess—. It's still in the offing, but it's losing its timeliness. Fast, really fast. So Paula has to do it fast, and if she doesn't, then I'll be calling Rather.

Harvey: At that Popular Culture Convention session where I met you, you said you expected there to be a change in Tracy somehow. Maybe I'm misremembering. It's one thing to take him and put him in a circumstance in which he's never been before and see what he'll do; but—is there going to be a change?

Locher: No. Not a permanent change. He, being the man he is, adjusts to every situation— including divorce.

Harvey: I notice that when they took their second honeymoon—at some fancy beach resort—the third day he's there, he's chasing after some new mystery.

Locher: Yes, yes. That was for the benefit of a story, of course. But we wanted to keep him still in character. There's a possible crime going on; I can't ignore it. Even though Tess says I should ignore it, I can't. We thought that was staying within character. As the story evolves—and it's developing now—he's giving her excuses, little white lies, so he can continue his investigation, but it ends up and they're lovey-dovey, and they go back home, and Tracy goes back to work. Both back where they should be. We're going to get back to characters—fast. The divorce story's over.

Harvey: I have to say that the resolution of the divorce crisis, which took a Saturday afternoon, a Sunday, and a Monday—and then it was over—seemed to me not to be dramatic enough. After this tremendous build-up, and then it sort of glided through it. And I thought about that, and I thought, Well, maybe that's the way people do behave; maybe there's no big thing about a reconciliation.

Locher: If it's a big thing, then it tends to involve lawyers. We were going to make a big thing about it, but we didn't want to let Tess say, Hey, everything's all right; we're back to normal. We didn't want her to do that. Yes, it could have been written better, I think—in all fairness; it needed a little more dynamite.

Harvey: I think Tracy said something like, Well, I'm gonna go now—on vacation—and I want you to come with me. And that was it. She melted into his arms. After fifty-three years of marriage, maybe that's true: maybe that's what she would do.

Locher: I think, considering the alternatives—fifty-three years of marriage gets you on the Paul Harvey show—we wanted something a little more than that. What we're going to do now, we're going to have Tess get a job. In response to a lot of the reaction we got. Is she going to just sit at home, pop chocolates, and watch daytime television? We said—the feminists read the strip, and they watch it closely. So we're going to make her viable—not a feminist; but she's going to get a job. She wants her independence. When she gets a job, it'll have something to do with the new crime. [Laughs softly] One of the biggest reactions we got was when Tess threw a book at Tracy. The spousal abuse people—oh, Christ: they were outraged. There were editorials in newspapers about spousal abuse, and they were looking for an excuse to write about spousal abuse, and they found the excuse in the Dick Tracy strip. Ah, c'mon. Good grief. That was almost too much. But we got through it.

Harvey: You mentioned working for Rick Yager.

Locher: I'd just gotten out of art school. And he used to come down and teach one day a week, which I think is really great for people in the business to do. I do it myself. And he would come down, and I had done a pirate ship, and I found out he was a great fan of pirates. He loved the old sailing ships. Gold doubloons, and sailing the bounding main and all that. And he'd see this illustration of a pirate ship I'd done, and he said, Have you ever done any commercial stuff? Why don't you come to my office. And we went out for dinner, and he offered me a job as his assistant. And I was his assistant—not for a long time. But for a while. We stayed friends and wrote letters and all that. And when I came back and went into commercial art—I almost became an airline pilot. When I came out [of the service], they said, Hey, boy. We're going to have four-engine planes. They had Pan Am, Eastern, United—all waiting there as we walked out with our discharge papers, waiting to sign us up. But I thought, Nah—I went to art school. Rick Yager did one of my stories once.

Harvey: In Buck Rogers?

Locher: Yes, it was really funny. It was a real dumb thing, but I was so honored that he did it. We stay in touch. He calls about once a month. He lives just over in Michigan.

Harvey: Gee, I didn't realize he was still alive. [Yager died a year after this interview, on July 22, 1995; he was 85.]

Locher: We talk. We exchange Christmas cards. But I had been in commercial art studio for about three years after I got out of the Air Force, and I was teaching art at night—I was single—at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts—and Coleman Anderson, who was Chet Gould's assistant at the time, was teaching there, and we went out and had dinner one time, and he said, Chet's looking for another assistant—he wants more than just me. Would you be interested? I said, Yes—let me talk to him. So I went out to Chet's house and met him for the first time. And he gave me a week's worth of strips, and he said, Go home and draw the figures—my figures, and I'll do the script. And he did. Or rather, I did. And he evaluated it, liked it. And hired me. That was in 1957. I got married the same month I started with him.

Harvey: What did you do on the strip?

Locher: I did all the backgrounds. I was with him for four-and-a-half years, and in the last year, his wife Edna came to him and said, We're going to Hawaii. And he said, No, I'm not. He never took a vacation. Never. He'd take a day off, but no vacation. She says, We're going to Hawaii. And he says, No, we're not. And she says, Dick's going to put in the figures for you. And he said, No, he isn't. [Laughter] He never let anyone touch the figures. And she insisted. So I did the figures while he was gone for a week. And he came back, and he looked at ’em like that [over his glasses], and he took a razor blade and scraped a lot of them off and said, Naw, that's not right. But he didn't scrape all of them off. He liked some of my drawings. And he let me do more and more. His brother did all the lettering. Ray. And I did all the backgrounds and helped with story. He used my story about Tracy stranded in the canyon with Professor Whitehall from Scotland Yard. He liked that story.

Harvey: Oh, was that the one where they were stranded on an island in a canyon with steep, unclimbable walls, right?

Locher: Yes. His theory, and I give him a lot of credit for this practice, was, Let's put Tracy's ass in jeopardy. And I said, Let's have him on a deserted island. Good idea, he said—I haven't done that before. How'll we get him there? Well, I said, let's have him on a plane with a hijacker who makes him jump. And he said, Fine. It was his idea to put Whitehall there. He'd been there for a long time and he'd lost weight. He was skinny, had a white beard, long white hair. Now, Gould says, how are we going to get him out of here? That was right about the time the U.S. Army was doing a lot of missile firing, so I said, Let's have a wayward missile land in the canyon and the army will follow it, find Tracy, and take them out of there. So that's what we did. It was fun. I was sitting on a cloud.

Harvey: You obviously wanted to be a cartoonist—and a strip cartoonist. You wanted to tell stories.

Locher: Yes, I like story telling. I like incidences, too—which is what an editorial cartoon is. And I also like long, long stories.

Harvey: And if you can do both, that's nice. And you're running two completely different styles, too.

Locher: Yes, different styles. I'll never forget when I was in the Air Force and Frankie Lane came out—Mule Train, remember that one? He came in and entertained us. And he was a terrible singer. And he got up at the end of the show and passed out cigarettes to all the airmen, and he said, Look, I'm not a very good singer—but I've got style. You've gotta sell with style. You've got to get somebody to look. And once you get them to look, you give them a good story. This is all philosophical. The hard work is banging out a new story. Something new. New slant, new character.

Harvey: Back in the thirties before radio had really taken over—well, it had, but not like television—people really lived the lives of their comic strip characters, and if the characters were in trouble, this was—to the readers—a real person in trouble. Do you ever get that sense?

Locher: Yes, yes. The mail reflects it. I had Flattop's grandson one time take a shot at Tracy and crease his forehead. And a lot of people called in and asked how he was doing. Did he get paramedic treatment and do it himself—what? People really do think that this character lives. What I like to do at the National Cartoonists Society is stand up and say, It's alive, it's alive.

You can't have Tracy do anything out of character, though. People wouldn't believe in him. There used to be a ten commandments of things you couldn't do in a comic strip. All those have gone by the wayside. You couldn't show a character falling-down drunk. You couldn't show somebody being massacred by machine-gun—probably because of the St. Valentine's Day massacre here in Chicago. Couldn't show a couple in bed. Couldn't show the inside of a woman's thigh. Couldn't show a woman drunk. And you couldn't show somebody being stabbed. And Chester Gould never paid any attention to any of those [laughs].

Harvey: Yes—as you were ticking those off, I was thinking of the incidents in Dick Tracy, which illustrated Gould just doing it.

Locher: Exactly right. [They both laugh] He had somebody impaled on a flagpole once. That violates every rule there is. We can't show that now. We can't do that now. We can't show somebody being shot, directly. Syndicates won't stand for it. Readers won't either.

Harvey: Is that right?

Locher: We can show robbery. We can show rapes. We can show arson. But only on the front pages of our newspapers—not in the comic strips.

Harvey: That's funny because one of the big fascinations of Dick Tracy in the beginning was that line that went from the muzzle of the gun from the villain's forehead and out the other side with a little of the bad guy's brain being sprayed out the other side, too.

Locher: Right out the other side. Exactly right. There are so many groups out there now, just waiting for you to do something. And they'll boycott the paper, and they'll march out in front. And they just can't wait. And the syndicates say, We don't need that kind of aggravation. And what we don't need is a lost client paper. Editors say, You're giving us so much aggravation, we'll just cancel. So they don't want that. So you have to tow the line. Action like that happens off-screen. Sam Catchem can say to Tracy, Oh—nice shot, Tracy. [Laughs] And that's a handicap to work under in a detective strip. Even in Sherlock Holmes on television, they can show somebody being killed. We can't do that. And boy that's working with your hand tied behind your back.

Harvey: Really it is, in this kind of strip.

Locher: Yes, in Dick Tracy. Calvin and Hobbes, what's the deal? No big deal. Biggest thing that happens in Calvin and Hobbes is that his boggers freeze. And that—that's acceptable. [Laughs] But you can't shoot somebody. And we can never show dope, heroine. Can't picture it, can't show somebody selling it.

Harvey: Can you do a story about dope at all? I suppose you can; you just can't mention what it is they're selling. [Laughs]

Locher: Isn't that a case. Here we are with a strip like this, and we can't show any of that.

Harvey: Do you think comic strips still have a future?

Locher: Bigger than ever. With the new electronic media—CD ROMs and all that. The old strips will come back. There are people out there who have never seen any of this stuff. And they're just discovering it, and that's nice.

Harvey: So all the old stuff is going to be cycled through CD ROMs?

Locher: All the old stuff—and, today's. On-line access. Like Online America. You have to pay to get on, but that's going to increase the exposure tremendously. We had a two-hour segment on Online America, Kilian and myself, and they got a lot of people to subscribe to the two-hour question and answer session. I never typed so fast in my whole life. Electronic mail, to me, is—I don't know, people talking to each other over a keyboard. Aren't we more sophisticated than that? I don't know.

Harvey: I haven't done much of that. But I don't know quite what the fascination of that is—except for people who do a lot of writing. But what about a phone call? Okay, you get to choose the time you want to write. And you don't choose with a phone call. Is that all?

Locher: A lot of things enter into it, of course. But there's no picture. This comes over the screen, typed, to me: How do you think Tracy felt when he got the divorce paper? Well, how do you type that back? Yeh, right: he was really upset. Read the comic, that's what I wanted to say. But I tried to be sincere. I like to go on radio talk shows. I do one here about twice a year. People who call in are just so sincere. What happened to Happy Hooligan in 1917 in March? Did he really throw a brick into the mayor's office? Of course he did.

Harvey: [Laughing] Didn't you see that?

Locher: [Laughing] That's the delightful aspect of comics. And for that part, I'm eternally grateful. That people take the time to read the comics.

Harvey: Is Dick Tracy alive in your mind?

Locher: Absolutely. Gets up in the morning and puts on deodorant. Shaves.

Harvey: And when you're doing a story and you say, He would never do that—

Locher: He would never do that. If he gets out of a parked car, would he open the door on the traffic side? No, he wouldn't. [Emphatically]

Harvey: He really is that straight arrow?

Locher: Absolutely. A lot of people write in and want us to tell more about the guns. What type of bullets? Name the guns. And that's valid. I think that's all the technical aspect of the strip that people are involved with. And we never want to forget that. Although you can bore some people to death with that. Some could care less about what millimeter a gun is. But those things all enter into the equation. You have to respond to it.

Harvey: You really are conscious of a big feminine audience out there?

Locher: I was during the divorce. Now we're back where we were. Female villains are great. It comes down to one word— B I T C H. And you want to make her as bitchy as you can make her. You tell a feminist that, they'd cut your head off. But that's what she has to be. A female villain has to be ruthless. I don't want any half-way villain. All the way.

Harvey: I wonder how Caniff's Dragon Lady would fare in this feminist market.

Locher: Yes, I wonder, too.

Harvey: She was a champion character, but—

Locher: Remember the strip he did— Male Call?

Harvey: Oh, yes. Of course that wouldn't get very far today either.

Locher: I remember the strip with two pilots who took Miss Lace out for dinner, and they were showing her how they fly, and they said, It's very simple: you just fly by the seat of your pants. And she says, Oh, I'm very embarrassed. And they said, Why? She said, I'm out of uniform. Can you see that in today's newspaper? [Roaring with laughter]

Harvey: [Laughing] It'd never make it.

Locher: But what marvelous stories we have, what marvelous vignettes, what marvelous characters who have drawn comics. Incredible people. A breed all to themselves. So much, in fact, that the U.S. Postal Service is going to bring out all those stamps. And there are four major museums in the United States.

Harvey: I don't think there's any question that there's an enormous audience for comics out there, and they're passionate in their devotion to them.

Locher: They really are.

Harvey: And it is strange to me that newspapers, which are the vehicle for this medium, are treating comics so badly.

Locher: Absolutely.

Harvey: It's the only thing that newspapers have that television doesn't have.

Locher: Exactly right. I said to the editor many times, and he laughs—Add another page of comics. Add a page.

Harvey: I got into a brouhaha with a Cincinnati editor at the Ohio State Comic Art Festival a couple years ago. He was telling how every time he chooses a new comic strip, he has to throw one out. And I said, Wait a minute: why? Where is it written that you can have only one page of comics? Is it written somewhere that you can have only three pages of classified ads?

Locher: Good point, good point. Oh, you hit the nail right on the head. Exactly right. That's the biggest market they have. This old squeal factor: we'll throw one out and see how much they yell. That's not valid anymore. It used to be. We threw out Mr. Boffo. All hell broke loose. He's back in. We made room. Comics are as individual as your tooth brush; everyone likes this, likes that. That's good repartee. That people will brag about it, put it on their refrigerator. I remember Chester Gould's statement about the New York Times never having any comics. And he said, Think what a great paper they'd be if they had comics.

Harvey: [Laughter] Right. If they're a great paper now, just think of how great they'd have been if they'd run comic strips. [Laughter] You said that the squeal factor is no longer valid. How do you mean that?

Locher: They don't care.

Harvey: If people squeal—

Locher: They don't care.

Harvey: Oh, editors have already decided—regardless of the squeals they may cause.

Locher: Right. Our readership surveys show—thus. And we don't care what the squeals are.

Harvey: And I suppose they know that comics readers are quick to write. I wrote when they dropped Gasoline Alley. Got a letter back. And they said, It's a worn-out strip. Threadbare ideas. Out-dated.

Locher: But to who?

Harvey: Jim Scancarelli, who does Gasoline Alley, did a write-in stunt—readers wrote in for a Wallet family tree, and he got 90,000 requests. Nobody was helping him pay for this. He had to finance it all out of his pocket. That's big response.

Locher: Helluva response. It really is. But you know, newspaper readers are the silent majority. They really don't respond to much. As a rule. They expect a lot, but if they get it or they don't get it, we don't hear much. You hear with an editorial cartoon if you hit their favorite subject. And that's good. You don't start out to insult them. I did one on the Catholic Church—I'm Catholic. I did one about how women are second class citizens in the Catholic Church. There are no women in any position in the church. They can count the money; they can organize the choir. My point was that women can't be priests. The letters that came in were—How come you made the Pope so fat? [Laughter, both] Good gravy! What about the issue? Would you kindly respond to the issue. Well, I have to get back to work.

Harvey: Fine. Thanks for letting me pester you.

Locher: It was fun. Glad you came by.

Locher Gets Out Here

Locher, who has been in frail health for the last few years after surviving a bout with cancer, has long regarded himself as the steward of Chester Gould’s creation, an American icon, and he aimed simply to maintain the legend. As his tour with Tracy ends, Locher looked back affectionately on their years together. "He's 80 years old and he's still humming; he's vibrant. He's not dead: he's alive and well," Locher told an interviewer. "I'm going to retire after three decades, and I think he's in good hands." Namely, those of artist Joe Staton and writer Mike Curtis. But Dick Tracy, Locher believes, will carry on in much the same fashion as he has since Gould created him in 1931. Locher’s job, he felt, was to keep Tracy as Tracy-like as possible, which he did by hanging the detective off a cliff every day. “We have to make sure readers come back tomorrow,” the cartoonist said, “—to see what happened.”

The cliffhangers and death traps are the reality in the strip, and over the years, Tracy assumed the reality of a friend.

"For a long and wondrous 28** years, I've been in the right-hand seat of Tracy's squad car," Locher said, deploying a heart-felt metaphor. "I can only hope that in this time I've entertained my readers and lived up to the lofty expectations of Chester Gould's glow. It's been an incredible ride. As a person I understood Tracy and he understood me. But when you get to that next stoplight up there—Dick! That's my corner. Let me out.”

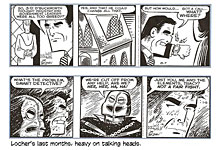

Now, here’s a short Gallery of Locher’s Tracy. In the last year or so, much more of the pictorial content of the strip is devoted to close-ups, which effectively transforms an adventure story to gossip—well, talking heads. In 1994 (and before, but we’ve got some divorce strips at hand), Locher was comparatively sparing in the use of head shots. Note, too, in Locher’s last strip, a Sunday, he takes a bow—and deservedly so. After the Gallery, some afterthoughts and a nit worth noting.

|

|

|

|

Fitnoots: Locher believed the divorce case had its roots in reality, not publicity, but when Kilian was interviewed about it, he admitted the whole thing had been concocted to drum up excitement and interest in the strip. Maybe for Kilian that was indeed the reason. But Locher had been living with Tracy longer and thought he knew the character and the ambiance well enough to believe a divorce could happen for all the reasons he offered in our interview.

** Most of the articles recording Locher’s retirement from the law and order biz say his stint on the strip lasted 32 years. This statistic comes from Locher himself, who includes in the total his four years as Gould’s assistant. But he wasn’t actually “writing” or “drawing” the strip that much during his apprenticeship, so I’ve altered the “record” to read “28 years,” the duration of his stewardship after the death of Gould and of Rich Fletcher, who had drawn the strip after Gould’s retirement—1983. From 1983 to 2011 is 28 years, not 32.