How Annie and Her Dog Sandy Lasted for Almost 86 Years

On May 13, 2010, Tribune Media Services announced its intention to stop production and distribution of one of cartooning’s iconic creations, the newspaper comic strip Little Orphan Annie. The resilient redheaded teenager is scheduled to make her last appearance in the nation’s newspapers on Sunday, June 13, just two months shy of celebrating an 86-year run. But the longevity, while notable, is deceptive: the strip foundered badly after the death of its creator, Harold Gray, in 1968, and while one of Gray’s successors righted the craft for two decades, Annie never again achieved the circulation or cultural status it enjoyed in Gray’s hands, proving yet again that a comic strip, uniquely the product of individual inspiration, usually cannot survive the death of its creator. And Gray’s strip was more idiosyncratic than most.

Born in 1894 in Kankakee, Illinois, Gray joined the staff of the Chicago Tribune soon after graduating from Purdue University in 1917. He left for military service in World War I and then returned to the Trib; but he quit in 1920 to operate his own commercial art studio. One of his clients was Sidney Smith who hired him to assist on The Gumps, the Tribune strip that was so popular that the paper set up a syndicate to sell and distribute it to other newspapers. Gray soon aspired to doing a strip himself (Smith's 1922 million-dollar contract may have helped inspire him), and he began sketching characters and imagining situations and talking to Smith about them. When Gray came up with a concept they both agreed was promising, Gray showed his idea to Captain Joe Patterson, storied head of the Tribune Syndicate. The Captain wasn't interested. But Gray kept at it. The ensuing parade of ideas was followed by a parade of rejections. It went on for months. One day while going over some of his sketches with Smith, Gray pointed to a drawing of a small gamin and declared that the boy would be an orphan.

"Not bad," Smith said, intrigued by the simplicity of the idea of a strip about an orphan, who must start out without relatives or friends or other complications. "But make the kid clean and cute and sweet to appeal to women readers."

Gray dutifully made the kid cute, gave him a head of curls, drew up a dozen sketches of the boy in various poses, and showed them to Patterson, calling his strip idea "Little Orphan Otto." For once, Patterson was interested. Searching for crowd-pleasing pathos probably, the Captain decided to try the orphan strip. But he wanted Gray to alter Otto: "The kid looks like a pansy to me," Patterson growled. "Put a skirt on him and we'll call it 'Little Orphan Annie.'" It may have been the head of curls that did it, recalling to Patterson's mind the image of Mary Pickford in her early films.

In the first volume of the IDW reprint of Little Orphan Annie, comics historian Jeet Heer reports his discovery of an alternative origin story for Annie: “In this version, Gray struck up a conversation with a young street urchin he met while roaming the streets of Chicago looking for ideas. ‘I talked to this little kid, and liked her right away,’ Gray told Editor & Publisher in 1951. ‘She had common sense, knew how to take care of herself. She had to. Her name was Annie. At the time, some 40 strips were using boys as the main characters; only three were using girls. I chose Annie for mine, and made her an orphan so she’d have no family, no tangling alliances, but freedom to go where she pleased.’”

Probably neither version is the unadulterated truth. The first smacks of legend; the second suffers from being a storyteller’s story, concocted long after the fact by which time Gray was an even better storyteller than he’d been on the outset.

The legend is that Patterson worked with Gray to plot the first few strips, telling the cartoonist to aim for adult readers. "Kids don't buy papers. Their parents do," Patterson explained. They devised a Dickensian tear-jerker of an introductory sequence: little Annie (smaller and therefore cuter at first than in her heyday) was forced to labor for her keep at the orphanage, which was as grim and oppressive as any Oliver Twist ever endured. Her fate was presided over by Miss Asthma, whose rotten disposition ringed every childish hope for adoption with a nimbus of gloom.

The first strip appeared on August 5, 1924, and concluded with Annie's bedtime prayer: "Please make me a real good little girl so nice people will adopt me. Then I can have a papa and mama to love. And if it's not too much trouble, I'd like a dolly. Amen."

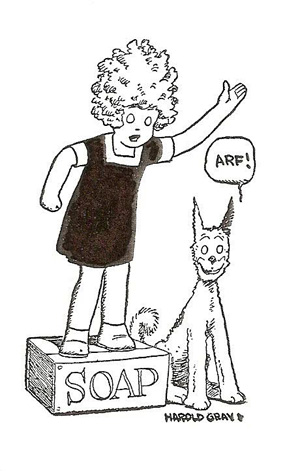

But Annie wasn't just a cute, sweet little girl. Gray quickly added dimension to her character: in the next day's strip, when a rude boy teases her, Annie wallops him in the kisser, establishing immediately that she has a certain independence of spirit in spite of her straitened circumstances.

In a short time, Annie was a popular feature, and that spirit of independence that pervaded Gray's work eventually enlisted a devoted readership. At the end of the second month of the strip's run, Gray introduced the character that would shape the philosophy of independence into a political stance: Annie is adopted by Oliver "Daddy" Warbucks, a millionaire industrialist who made his fortune manufacturing munitions during World War I. Warbucks became Gray's example of the self-made man, the self-reliant individualist who made himself what he is through purposeful enterprise. The epitome of this culture hero, Warbucks is the larger-than-life version of what all the "little people" in the strip inevitably become if they follow Annie's example of diligent labor and canny capitalism.

But to be exemplary, Annie can scarcely be a rich man's daughter. As soon as Gray had established bonds of affection between Annie and "Daddy," he sent Warbucks off on a business trip, and Annie is returned to the orphanage by the spiteful Mrs. Warbucks (who soon disappears from the strip forever). Annie is adopted again, this time by a slave-driving couple who make her life miserable. She runs away, accompanied by her only friend, a large orange-colored dog named Sandy, whom she acquired in January 1925.

The two eventually take refuge at a farm owned by the poor but kindly Mr. and Mrs. Silos. But Annie is no burden to them: through hard work and her own ingenuity, the eleven-year-old waif is able to contribute to the couple's welfare and happiness. After a few months, though, "Daddy" Warbucks finally locates Annie and takes her and Sandy back to live in splendid comfort with him. Thus did Gray inaugurate the cycle of separation and hardship, rescue and reunion that framed Annie's adventures and the quest motif that animated them throughout the strip's run. Separated from "Daddy," Annie must find the means of survival; through her unflagging perseverance, she always does.

Oddly enough perhaps, Little Orphan Annie reached the zenith of its popularity during the thirties. "Odd" because it was the decade of Franklin D. Roosevelt, the man who gave government a social conscience. FDR's mission ran in directions diametrically opposed to Gray's ideas of self-sufficiency. Under Roosevelt's tutelage, the down-trodden and the poor, the halt and the lame were encouraged to look to government for help rather than exhorted to help themselves by toiling determinedly and exercising tenaciously the principles of free enterprise. Gray's message was precisely the opposite—although it was as much an accident of his story as it was a matter of political conviction.

The best way for a little orphan girl to make her way in the world without being simply a weepy milksop is for her to be self-reliant. As a good story-teller, Gray knew that. Warbucks and the rest of Annie's entourage were natural outgrowths of this central notion. As Gray's exemplar, Warbucks could scarcely espouse self-reliance and free enterprise during the Roosevelt years without, at the same time, seeming to attack FDR's policies. And so Little Orphan Annie became the first nationally syndicated comic strip to be unabashedly, unrelievedly, "political."

Annie was not the first political strip: as we saw in the November 2007 installment of Harv’s Hindsight, Bud Fisher’s A. Mutt—the first daily strip—was the first to take political potshots in its panels. But Fisher's strip was published only in San Francisco at the time: it could reflect the opinions of its host paper to a fare-thee-well and suffer no more consequences than the editorials in the same paper (that is, the paper would presumably not be purchased by those who disagreed with the views expressed).

Gray's strip, on the other hand, was distributed nationally, and by tradition, syndicated strips steered clear of politics for fear of offending client papers who might cancel their subscriptions in retaliation. Annie was the first to break with custom. But it did so because the very essence of its story demanded it. Gray's celebrated conservatism was hardly negligible in the development of the strip's political thrust. But neither was the strip's political content artificially superimposed upon an otherwise simple tale of a wandering orphan girl and her dog. The strip's politics were organic—integral to its story and its heroine's personality.

Throughout the thirties, Annie drifted from place to place, into "Daddy's" care and out of it, spending most of her time with the ordinary folk and reviving by precept and example their faith in the values of hard work and economy. Sometimes the villainy she faced would be too much to be overcome by such simple virtue, and then "Daddy" Warbucks would show up and rescue Annie and everyone else.

In the thirties, Gray introduced another element into the harsh reality of his rendition of the Depression—the element of fantasy. Increasingly, Annie was encountering villains that were not merely greedy landlords or corrupt small-time politicians: some of them were criminals of the most unconscionable nastiness, unscrupulous schemers and plotters of the vilest sort, some with plans for world domination.

"Daddy" always arrived in time to save Annie, but not even he, powerful as he was, could punish these villains enough for their crimes. So Gray gave Warbucks aides adequate to the task. Gray had always been fascinated by the Orient (one of Warbucks' earliest cohorts had been a Chinese mandarin named Wun Wey), and he now began to employ Oriental magic against his villains. On February 3, 1935, a giant, turbaned Indian, eight (perhaps nine) feet tall, showed up as Warbuck's new right-hand man. Punjab was that paragon, a kindly man of enormous strength and vast intelligence. And he could also supply an appropriate punishment for the most unsavory villains, villains too unspeakable for ordinary legal disciplining: throwing a magic blanket over them, Punjab muttered an incomprehensible incantation and banished them from this world (presumably sending them to another, much more unpleasant, plane of existence).

Two years later, on February 21, Gray gave Warbucks another memorable assistant, a black-garbed, hooded-eyed agent of vengeance much more single-minded in purpose than Punjab and entirely humorless. His name, the Asp, evokes the poisonous viper Cleopatra deployed to achieve her suicide. The Asp’s whose homeland was (appropriately) in the Middle East where the term assassin originated.

Gray's fascination with the mysteries of the Orient culminated later in the same year with the introduction of the cryptic Mr. Am, a fatherly, bearded sort of sultan, who, Gray hinted broadly, had lived since the dawn of time and who could enter the fourth dimension and restore the dead to life. (And if readers wanted to think Mr. Am might be Gray’s version of God, the cartoonist might smile but he probably would not object.)

Fanciful as Gray's fantasy element was, it was not at all light-hearted. At first glance, his drawing ability seemed too crude for rendering either his reality or his fantasy convincingly, but upon longer acquaintance, his artwork cast a spell that enhanced his story.

In maturity in the late thirties, Gray's drawings were filled with solid blacks, heavy shadows, darkly shaded nooks and crannies. It was a comfortless world, vaguely sinister. And in that world, Gray's people stood around rigidly, posturing woodenly, as if inhibited, restrained, in their movements—perhaps because they were fearful. They seemed, in effect, nearly paralyzed with fear and apprehension. And the blank eyeballs for which Annie is famous were integral to the mood of this fearful climate.

Although there was little action in many of Gray's tales, most of them erupted in violence sooner or later. Consequently, Annie seemed perpetually immersed in a sinister night-time world that threatened to assault her at every street corner. And her blank eyeballs were marvelously appropriate to her situation. One walks through a threatening night gingerly, never looking behind or to the side for fear of seeing a sinister presence there. One keeps his eyes focused resolutely, rigidly, ahead of him, in a kind of unseeing stare—precisely the effect that Annie's eyeballs have. In such an atmosphere, when violence breaks out, we are not surprised. It belongs there. We have been led to expect it—to fear it. (The blank eyeballs would have been inspired graphic touch had Gray invented the device expressly for the purpose just described; but he was merely following one of the conventions of early comic strip art: George McManus drew Jiggs' and Maggie's eyes in the same way in Bringing Up Father, where the effect produced was quite different. In Gray's strip, though, the convention contributed substantially to the impression Gray clearly intended.)

Some readers and critics—mostly avid supporters of Roosevelt's New Deal—saw Annie as a political mouthpiece for Tribune publisher Robert McCormick's conservative views masquerading as entertainment, a not-too-subtle indoctrination attempt by the Chicago Tribune. McCormick's opposition to Roosevelt's policies had a complex root system, partly philosophical and partly economic. We needn't go into these matters at length here: for our purpose, it is perhaps enough to indicate what McCormick's detractors may have thought.

Reduced to the simplest terms, McCormick and others of his station who opposed FDR were seen as protecting their own self interest. FDR's effort to make society care for the destitute and the jobless of the Depression had to be financed, and since no one but the rich had money, it seemed logical to assume that the rich would finance social welfare through increased taxes. Thus, much of the conservative opposition to Roosevelt could be interpreted as originating in the narrowest kind of selfishness: the desire of the wealthy and powerful to preserve their wealth and power. McCormick was wealthy and powerful. Many of his class saw FDR's programs as the cutting edge of an economic revolution that threatened their very existence. They believed that if society took up the burden Roosevelt urged upon it, the existing social order would be overturned in the process.

McCormick may have shared these views to some extent, but since I have deliberately simplified (and therefore distorted) the issues here, we can give him the benefit of the doubt by viewing his war against Roosevelt from another angle. Consider the threat that the New Deal posed to McCormick's vision of America. The New Deal, with its radical restructuring of political and social order, would alter forever the traditional American way of life that the Tribune had championed throughout McCormick's stewardship. From Gasoline Alley to the U.S. flag on the front page, the Tribune stood for the values of Horatio Alger—small town life with its promise of success in return for hard work and perseverance.

Regardless of the point of view we adopt for assessing McCormick's politics, it's not surprising that many thought he dictated Annie's storylines. But the situation was scarcely as simple as that.

While the strip's political diatribes during the thirties echoed McCormick’s on the editorial pages of the Tribune, they didn't, for a long time, reflect Patterson's views, and it was Patterson who ran the Tribune Syndicate and directed the efforts of the cartoonists. With his eye ever on the common working people, Patterson sensed that most of his readers were behind Roosevelt. Moreover, the Socialist instincts of his youth, never fully abandoned, made him sympathetic to the worker's plight. In the early thirties, the Tribune’s sister paper that Patterson operated in New York, the screaming tabloid Daily News suddenly (and, remarkably, without any change in circulation or financial status) shifted its editorial ground.

In a celebrated speech to his staff, Patterson announced, "We're off on the wrong foot. The people's major interest is no longer in the playboy, Broadway and divorces, but in how they're going to eat, and from this time forward, we'll pay attention to the struggle for existence that's just beginning."

Almost alone among major newspaper publishers, the Captain supported Roosevelt and the New Deal. And his support lasted through the thirties—until, in Roosevelt's lend-lease formula for aid to Britain, Patterson thought he saw the President tipping his hand. Once Patterson, a passionate isolationist and advocate of neutrality, thought Roosevelt intended to get America into the European conflict, he broke with FDR and became as bitter a critic of his policies as McCormick, Patterson’s cousin and partner, had been for nearly a decade.

And so was born the McCormick-Patterson Axis—the opposition to Roosevelt by the combined editorial voices of the two largest newspapers in the country's two largest cities. But from March 1933 (the month Roosevelt was inaugurated for his first term) until December 1940 the cousins disagreed on Roosevelt, and Patterson defended him as passionately as McCormick attacked him viciously. Meanwhile, Gray's orphan heroine went somberly about her business—reflecting her creator's opinions, born of both political conviction and narrative necessity. And they were opinions that found enthusiastic reception among the readers of the day.

Even while attacking FDR, Little Orphan Annie addressed profound concerns among its readers. The events of the Great Depression unfolded gradually: the world did not collapse overnight. And as the economic institutions slowly crumbled, one after another, the dominant emotion among the population was fear—fear that an entire way of life, the American way, was falling apart. Gray's strip addressed and assuaged that fear. Annie's adventures proved again and again that the historic American ethic of hard work was not bankrupt and that capitalism could still work. Readers were reassured and comforted.

Annie (and Gray) joined the homefront war effort during World War II. Annie blew up a German u-boat offshore and organized the Junior Commandos to collect tons of newspapers, scrap metal and other recyclable materials used in the manufacture of munitions and other implements of war. And then all of a sudden, Gray’s politics became more overt.

What began as a storyteller’s stance morphed into a conservative’s protest. When Roosevelt was nominated for a fourth term in the summer of 1944, Gray had endured enough: he symbolized his feeling that FDR’s policies would be the death of the country by having “Daddy” Warbucks die. On his deathbed, Warbucks complains and explains: “Some have called me a dirty capitalist, but I’ve merely used the imagination and common sense and energy that kind providence gave me. Now? Well, Annie, times have changed, and I’m old and tired. I guess it’s time to go.” Warbucks simply couldn’t survive in FDR’s welfare state.

But after Roosevelt died the next spring, Gray brought Warbucks back to life. As Warbucks put it: “Somehow I feel that the climate here has changed since I went away. We’ll see....”

Gray’s politics—or, perhaps more accurately, his cultural convictions—proved to be the spark that ignited his storytelling. And no one else would combine similar elements to successfully continue Annie. When Gray died in 1968, the strip was assigned first to his assistant, Tex Blaisdell, and then to David Lettick, who made a regrettable attempt to revive Gray’s earliest Annie, the younger, cuter one; but their Annie was an anemic shadow of Gray’s. The syndicate discontinued their effort in 1974 and went to reruns of Gray classics.

But after the 1977 success of “Annie,” the Broadway musical based on the strip, the syndicate resurrected the feature in 1979, turning it over to veteran comic strip storyteller Leonard Starr, who, by then, had retired his own comic strip, Mary Perkins, On Stage—a beautifully, realistically illustrated and well-told adventure/human interest continuity. The revitalized strip was renamed Annie to foster associations with the musical, and Starr skillfully revamped the look of the strip, retaining the essential appearance of the characters and hints of the brooding atmosphere of Gray’s effort but producing visuals that were crisp and modern-looking. Starr’s Annie was a successful endeavor, but it wasn’t infused with Gray’s passion. It was thoroughly professional but emotionless.

When Starr retired in 2000, TMS (Tribune Media Services, the new incarnation of the old Tribune Syndicate) turned the writing of the strip over to a New York Daily News staffer with a penchant for comics history, Jay Maeder. The drawing was initially done by comic book veteran Andrew Pepoy, but it was a lot of drawing and very little money compared to what Pepoy could earn drawing comic books; he left after a year or so, and Alan Kupperberg took over until 2004, when Ted Slampyak assumed the drawingboard chores. He drew the last Annie strip for June 13 release.

Commenting about the end of the strip to Larry McShane at the Daily News, Slampyak said: “It’s kind of painful—almost like mourning the loss of a friend.”

Maeder’s stories veered away from Annie more often than not, featuring Oliver Warbucks as an adventuring entrepreneur and patriot—“a sort of buff, Clive Owen-type,” saith Steve Tippie, TMS vice president for licensing. Maeder introduced several new supporting cast members, some of whom would run away with the strip for weeks on end. The most attractive of these was the woman pilot, Amelia Santiago, who, in action and name, was worthy of her own comic strip. I had the sense sometimes that Maeder’s stories never actually ended: they scrambled through one threatening menace after another but then turned a corner into a new series of threats and menaces before quite resolving the previous conjuration. It was a page-turner without end—a continuous cliff-hanger. Nothing wrong with that: daily continuity strips are, almost by definition, prolonged cliff-hangers. But most of them end stories; Maeder’s Annie never seemed to.

Gray’s strip had inspired a radio show, the first late-afternoon serial for young listeners; it debuted in 1930 and continued until April 1942. Hollywood produced movie versions, and Annie merchandise flooded the marketplace from time-to-time. The 1977 musical, which is performed over and over again across America by community theaters that pay fees for the privilege, has been “an annuity” for the syndicate, according to Tippie, interviewed by Phil Rosenthal at the Chicago Tribune. And TMS isn’t likely to forget the orphan’s revenue-generating potential.

As the strip approached its discontinuation, it was being published in less than 20 newspapers; it could scarcely yield enough income to support its writer-artist team. Not even the Tribune was running the strip, once one of the paper’s biggest attractions.

Strangely, with Tippie as our source, TMS doesn’t seem to know why the strip has slipped in popularity. Officials are blaming the generally straitened circumstances in the newspaper business: the last few years, Tippie said, the strip has targeted young readers (instead of adults who are the biggest segment of comic strip readers?), and young readers don’t buy or read newspapers. Tippie and his cohorts may be confused about who reads their features, but they are not confused about potential revenue sources.

In the last panel of the last strip, we see Daddy Warbucks, who, for all practical purposes, has displaced Annie as the chief protagonist, brooding uncertainly about what happened to Annie in her latest run-in with the Butcher of the Balkans. “And, leapin’ lizards, what about her dog Sandy?” asks Rosenthal.

It’s a cliff-hanger, a Maeder specialty—“actually a show of faith that there’s still life in the old gal,” says Rosenthal. And then he quotes Tippie:

“Annie is definitely not dying,” Tippie says. “She will definitely have a life beyond this newspaper incarnation. The daily newspaper strip will go away. Now, that doesn’t mean that Annie won’t come back—whether in comic books, graphic novels, in print or electronic media. It’s just too rich a vein not to mine,” he concluded.

All that’s lacking is the prospector who discovered and developed the vein of gold 86 years ago.

*****

Now, here are some glimpses into that prospector’s vision of the auburn-haired orphan plus those of some of his successors’. We conclude with a couple examples of Gray’s laudably perverse sense of humor. Yes, he had one—even about such intimate matters as Annie’s eyeballs and her perpetually red dress.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Footnit: Most of the foregoing appreciation appeared first in a chapter, “The Captain and the Comics,” in a book of mine, The Art of the Funnies, which we sell here, perhaps the only place where you can still find it. The tome is described at tedious length here.