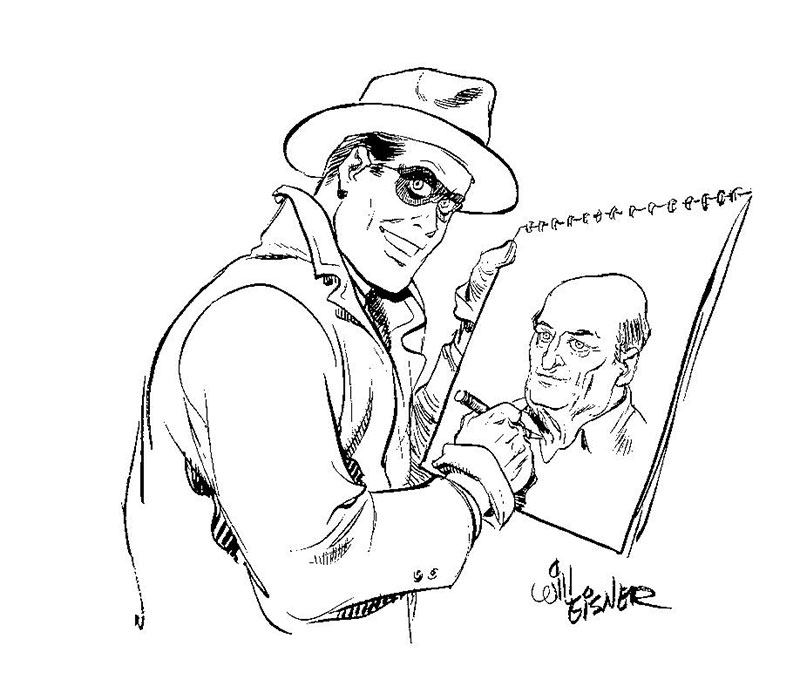

OUR LAST

SIGHT OF EISNER’S SPIRIT

Another in

our series commemorating the 100th anniversary of Will Eisner’s

birth.

DOWN THE SCROLL

a bit is the last story Will Eisner would do about the comic book character

that made him famous. It was a story he never intended to do.

“Will

Eisner did not want to do this story,” said Diana Schutz, who was

his editor at Dark Horse, which published the story.

“Really,”

she continued. “I caught him in a moment of weakness and then wouldn’t let him

forget it. I am, as Will once called me, a ‘demon editor.’”

At

the time Eisner produced the accompanying story, he had just finished The

Plot: The Secret Story of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which would

be published in 2005. It was a polemic, he told me—a book that made an

argument. The argument in The Plot was that The Protocols of the

Elders of Zion was a monstrous lie, an anti-Semitic slur that had somehow

survived despite generations of being thoroughly debunked in country after

country after country.

Eisner

had deployed the graphic novel as a polemic at least once before—in Fagin

the Jew, which had been published in 2003 just before The Plot. In Fagin,

he had undertaken to give Charles Dickens’ Jewish master thief a better

reputation and a plausible biography instead of the flat stereotype that

Dickens deployed in Oliver Twist.

It

was time, Eisner thought, that the graphic novel be put to serious use. And he

doubtless had other serious uses in mind for the art form that he had almost

single-handedly made into a literary enterprise. But he put all that aside to

do a story for Diana Shutz.

At

the time, Shutz’s editorial projects at Dark Horse included comic books

featuring the Escapist and an authorized biography of Eisner, Bob Andelman’s A

Spirited Life. The Escapist was the comic book character invented by

Kavalier and Clay, two fictional comic book creators that Michael Chabon had

invented in his 2000 novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalie & Clay as

homage to Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel, the comic book creators that invented

Superman. In 2004, Dark Horse began publishing a comic book series starring the

Escapist.

From

her unique perch as editor of the two Dark Horse projects, Shutz was able to

elbow Eisner into doing a Spirit story.

“Bob

Andelman and Eisner were hoping that Chabon would write an introduction to the

biography,” Shutz said. “And Michael was hoping that Will would write and draw

a story for the Escapist comic book in which the Spirit meets the Escapist. So

I struck a deal, negotiated a little trade. From my perspective as then-editor

of both projects, it was a win-win scenario.

“Will

used to joke that he could never refuse me anything,” she continued. “But

asking Will to return to a character whom he’d left behind in 1952—in order to,

eventually, pursue stories set in the real world about real people and their

real hopes and dreams, stories that were far more personally meaningful to Will

than the pursuit-and-vengeance standard of most adventure tales—that required

some serious sweet-talking.

“But

once Will agreed to something, he never backed down,” Shutz went on. “He sure

took his time, though, about doing this story—and I knew his heart wasn’t

really in it. Finally, I recommended that he just ditch the usual superhero

conventions altogether and write a story about these two guys, Denny Colt [aka

the Spirit] and Tom Mayflower [aka the Escapist], who actually have a lot in

common, right down to the mask (that Will always hated putting on the Spirit,

by the way).

“The

non-genre approach piqued Will’s interest,” she finished, “—and then he did me

one better, by working that approach into an adventure story, after all! God

bless him, he was so good.”

Here’s

the story—:

THE DAY AFTER

Eisner sent Schutz the finished art for the story, he checked into the hospital

in Lauderdale Lakes, Florida, for quadruple bypass surgery. The operation was

performed on December 22, 2004, and a week-and-a-half later, on January 3,

Eisner died of complications resulting from the surgery, internal bleeding. He

was only 87, and he’d played tennis almost every day until the last few months.

Eisner

was a legend, a giant, a revered figure in the history of comics. Schutz listed

the landmark achievements of his life: comics entrepreneur and creator of the

Spirit, pioneer of creators’ rights (in an era when that was considered a

preposterous notion), creator and promoter of educational comics, graphic

novelist whose first, A Contract with God, was published decades before

the format became so popular, educator and writer of Comics & Sequential

Art, the field’s seminal textbook, and the man after whom our industry

awards are named.

Despite

his fame and deserved reputation, “Will had a knack for always making you feel

special,” said Schutz.

“It

is both fitting and ironic that this Spirit story should be Will’s last work,”

she continued. “Ironic because he’d moved so far beyond the genre conventions

of The Spirit, and while he was proud of the innovations he’d created

all those years ago, he felt his graphic novels were more important, more

literary, more a testament to what comics could—and should—really be.”

And

most of his life had been dedicated to proving what comics could be.

Schultz

finished: “Yet it is absolutely fitting that Will should come full circle and

leave us with this one last Spirit story, a final gift to all his readers and

fans who clamored for half a century for just this. That should make all of us

feel very special.”

My

own regard for Eisner’s achievement began when I was still in high school in

the 1950s, copying the Spirit in my recreational doodling.  And years later when I

was creating a comic strip to sell into syndication, I continued flattering The

Spirit by imitating a couple scenes from one of Eisner’s stories. (To see

how, visit Harv’s Hindsight for July 10, 2012, “Fiddlefoot: A

Comic Strip that Never Was, Almost.”) And years later when I

was creating a comic strip to sell into syndication, I continued flattering The

Spirit by imitating a couple scenes from one of Eisner’s stories. (To see

how, visit Harv’s Hindsight for July 10, 2012, “Fiddlefoot: A

Comic Strip that Never Was, Almost.”)

My

affection for Eisner began at the moment we met and continued through

subsequent encounters, including several interviews during which I came to know

him better and better.

Five

years after he died, his renowned place in the history of the medium secure and

his prominence towering above all others, came the first of two stabs in the

back of his reputation.

On

July 1, 2010, Ken Quattro posted at his thecomicsdetective.blogspot the

transcript of Eisner’s testimony at the first copyright infringement case in

comic book history, and the transcript proved Eisner had lied—both on the stand

at the trial and in recounting the incident in later years.

Quattro

was devastated. “Will Eisner is my hero,” he said. “To me he was a Promethean

figure—creative, farsighted and flat-out brilliant. ... Nothing spoke more to

his integrity than the story of his testimony in the groundbreaking lawsuit, DC

vs Victor Fox.”

Like

Quattro, I was stricken. But I read the transcript—hoping whatever Eisner said

could be interpreted in some way that would exonerate him. No luck.

Victor

Fox had been working at DC Comics and had observed the success of Superman when

the character had debuted in Action Comics, No.1 in the spring of 1938.

The next winter, Fox, “hoping,” as Quattro put it, “to catch the coattails” of

Superman’s success, launched his own comics publishing company, and he hired

the Eisner-Iger shop to produce the lead feature, which, as Fox directed, was

an out-and-out imitation of the Man of Steel called Wonder Man.

DC

sued, claiming copyright infringement. And as the case approached trial, Fox

asked Eisner, who drew Wonder Man according to Fox’s specifications, and Jerry

Iger, Eisner’s partner, to testify that they’d created Wonder Man without

knowing about Superman.

In

telling the story in his later years, Eisner said he couldn’t do what Fox

wanted.

“It’s

not true,” he told his biographer Andelman. “Victor described the character

exactly the way he wanted him in a handwritten memo. Obviously, a complete

imitation of Superman.”

“Eisner

agonized about what he’d say at the trial,” wrote Andelman. At the time, Eisner

was only 22 years old and on the cusp of creating a career in comics. If he

told the truth, what would become of his career?

“Finally,”

said Andelman, “he decided that he couldn’t commit perjury and, when called to

the witness stand, he testified that Fox literally instructed Eisner and Iger

to copy Superman.”

The

only noticeable consequence was the Fox didn’t pay the Eisner-Iger shop for the

work it had done.

But

the transcript shows that Eisner did as Fox had demanded. That he hadn’t told

the truth. That he’d lied to protect Fox. And then when relating the story to

Andelman, he’d lied again.

It

was a sad day for the legions of Eisner fans. But we all found reasons to

excuse Eisner. We had to.

And

then last year came another blow, this time to Eisner’s reputation as the

inventor of the graphic novel.

Eisner’s

claim to have created the graphic novel with the 1978 publication of his A

Contract With God was always on shaky ground. First, the book is not a

novel: it’s a collection of short stories. And Eisner didn’t use the term

“graphic novel” in print until the second printing of the book. At one time, he

claimed he’d picked the term out of the air when pitching the book to

publishers.

The

term was pretty certainly coined by Richard Kyle in 1964. Some claim

that George Metzger produced the first graphic novel in 1976 with Beyond

Time and Again, which called itself a graphic novel on the title page.

And

there are earlier claimants. According to Paul Levitz, Harvey Kurtzman’s

Jungle Book in 1959 was “the first all-original comics in book format and a

recognizable prototype of the current graphic novel.” Or was the prototype It

Rhymes with Lust, Arnold Drake and Leslie Waller’s “picture

novel” deliciously rendered by Matt Baker and published in 1950. Or was

it 1968's His Name Is ... Savage, a magazine-sized spy thriller by Gil

Kane and Archie Goodwin that Eisner had seen and lamented its

collapse after only one issue.

At

first, when people said Eisner’s Contract was the first graphic novel,

he went along with it. As these other candidates surfaced, though, he backed

away from the claim, saying, in effect, that the term had been “in the air” at

the time, and he’d merely appropriated it without claiming to have invented

either the form or the term.

But

then last spring, in the inaugural issue of Inks, the journal of the

Comics Studies Society, an article by Andrew J. Kunka shows that Eisner was

aware of the term “graphic novel” and the evolution of the form as early as

August 1974. That’s when Jack Katz sent Eisner a copy of the first

chapter of what he called his “graphic novel,” The First Kingdom.

Katz

continued to send Eisner chapters of the book as they were published until the

last one, No.24, in 1986. Katz accompanied the books with letters, and Eisner

responded, effectively creating a 12-year correspondence in which the two

discussed and applauded the emergence of this adult-oriented form of the comics

medium.

Katz

asked Eisner to write a foreword for the series, which appears in No.23, the

penultimate issue. In it, Eisner acknowledges that Katz “carved out a position

for the graphic novel concept and helped establish a category for work produced

with literary intent.”

Kunka

also speculates that it’s also possible that Eisner saw Kyle’s column in Fantasy

Illustrated No.6 (Summer/Fall 1966) in which Kyle reviews the first issue

of Harvey’s Spirit reprints, using the terms “graphic short story” and

“graphic novel” as part of his discussion.

Still,

as I have said many times, even if Eisner didn’t invent the form or the term,

he explored its potential with great dedication and skill, perfecting the form,

and those who followed afterwards expanded the form, extending its reach,

exploring its potential—in the spirit of Will Eisner.

In

any case, Eisner’s reputation has now been sullied by two circumstances that

contradict what he had said. For those of us who have a high regard for

Eisner—both as an artist and as a man—there must be some plausible explanation

for these contradictions that leaves Eisner’s standing intact, perhaps not

inviolate but still admirable.

Here’s

mine:

Don’t

go to storytellers for factual truth. Eisner was, above all else, a

storyteller. A champion storyteller. Storytellers tell stories, and most of the

stories are made-up. Fictions. Lies. Storytellers are adept at lying. We don’t

go to storytellers for factual truth. We go to storytellers for stories, for

fictions that reveal other kinds of truth, the metaphysical kinds.

Eisner’s

story about his testimony at the DC vs Fox trial is about youthful courage in

the face of economic pressure. We all hope we’d do the same as the Eisner in

this story did.

Eisner’s

story about inventing the graphic novel form and the term denoting it is about

creative inspiration and commercial acumen, coining a term that had greater

appeal for adult readers than the much-maligned “comic book.” We all hope for

inspiration to strike us and make us rich and famous.

His

stories are inspirational. Like all good stories.

What

more can we ask of storytellers?

Just

a little more—:

At

the 1999 San Diego Comic-Con, Eisner was scheduled to appear on a panel with

Chuck Cuidera, who had just lately started coming to comic cons. A few months

before this Comic-Con, Cuidera had been interviewed about his career in comic

books, including his work with Eisner at Quality Comics—specifically, his

connection with the Blackhawks. Eisner is always credited with creating the

Blackhawks, and Cuidera, coming suddenly out of the woodwork, claimed he, not

Eisner, had created the famous team of aviating-troubleshooters.

Their

joint appearance on the same panel promised fireworks and unpleasantness.

The

panel was chaired by Mark Evanier, who, as I understand it, arranged a meeting

between Eisner and Cuidera before the panel convened.

During

the presentation, fairly early on, Evanier asked Cuidera what Eisner had

assigned him to do.

“Well,”

Cuidera joked, “—I did more of The Spirit than I did of Blackhawk!” (laughter)

Then

Eisner chimed in:

“Absolutely.

I'd like to say something, Mark, because this is heading into that. I've been

wanting to say this for a long time, because I've done conventions a lot, and

there's been a lot of talk about who invented what. It's not important who

created it. It's the guy who kept it going, and made something out if it that's

more important. Whether or not Chuck Cuidera created or thought of Blackhawk to begin with is unimportant. The fact that Chuck Cuidera made Blackhawk what it was is the important thing, and therefore, he should get the credit.

It

was the neatest piece of diplomacy I've ever witnessed. And Eisner’s remarks

have the additional virtue of being factually accurate. Eisner’s point was that

Cuidera developed the Blackhawk concept and made the creation famous and

popular.

Eisner

gave Cuidera the lion's share of credit but Eisner never denied

or confirmed Chuck's contention; nor did he, Eisner, ever say, "Chuck's

wrong: I created the Blackhawks." He dodged the bullet but gave Cuidera an

appropriate share of credit —and his dignity.

That’s

the Will Eisner I remember.

Return to Harv's Hindsights |