Krazy Love

How George

Herriman’s Metaphysical Comedy Evolved

Unabashedly

commercial, newspaper comic strips have traditionally been a mass medium of the

crassest sort. Introduced as circulation-building devices, comic strips were

designed to appeal to the largest possible audience. They had to sell the

newspapers they appeared in; therefore, they had to be popular. This coupling

of imperatives is perhaps what makes comic strips so decidedly American. The

comic strip was not invented in America, but the American way fostered the

medium's rapid growth and development to an extent not achieved elsewhere.

Propelled by the capitalistic impulses of the marketplace in free enterprise

competition, the comic strip bloomed and flourished in a great variety of

genres and styles. And despite its catchpenny function as commodity, the

medium was capable of artistic achievements of a very high order.

That

the crucible of commercial competition produced artistic as well as

materialistic successes is beyond question. But it is the medium rather than

the marketplace that is responsible. Comic strips are extraordinarily

susceptible to individual creative impulse. A cartoonist is a kind of one-man

band. Or, to employ a cinematic metaphor, a cartoonist is script-writer and

story editor, casting director and camera operator, prop man and make-up

artist, and producer and director and actor and actress. Not all comics are

produced by a single creative intelligence, but the medium readily permits such

individual productions. And most of the greatest strips have been the

expressions of a single creative vision, as unique with their creators as Popeye is with E. C. Segar. Among the most individual comic strip creations are the

lyrical achievements of George Herriman, Crockett Johnson, Walt Kelly and Bill

Watterson.

These

cartoonists are the lyric clowns of the medium. Their creations were bursts of

poetry. Poetry in the literary tradition is a kind of word game: its great

appeal lies in the sound and rhythm of the language and in the nuance and

interplay of metaphor and meaning. Poetry is a game for the mind, an

intellectual sport. And the creations of Herriman, Johnson, Kelly and

Watterson—Krazy Kat, Barnaby, Pogo and Calvin and

Hobbes—are likewise divertissements for the mind. Their humor is

intellectual rather than intestinal: we laugh in our heads not in our

bellies.

In

his 1924 book, The Seven Lively Arts, art critic Gilbert Seldes called

Herriman's comic strip about an allegedly lunatic cat "the most amusing

and fantastic and satisfying work of art produced in America today." This

accolade and the accompanying lengthy analysis of the strip by one of the

foremost critics of the day gave social and artistic respectability for the

first time to the erstwhile "despised medium" of cartooning. It was

Seldes who first analyzed the strip's plot and articulated Herriman's theme.

Like

any great work of art, Krazy Kat's thematic complexity is masked by its

seeming simplicity. After a couple of formative years, the plot that emerged

involved only three characters— a cat (Krazy), a mouse (Ignatz), and a dog

(Offissa Pupp)— but each is doing something profoundly contrary to its nature.

Instead of stalking the mouse, Krazy loves him and waits for him to assault

her; instead of fearing the Kat, Ignatz scorns her (or him— Krazy is without

sex, Herriman explained, like a sprite or elf) and attacks her repeatedly;

instead of chasing the Kat, the dog protects her out of love for her. This is

Herriman's eternal triangle; and each of its participants is ignorant of the

others' passions.

Into

this equation, Herriman introduced a symbol: a brick. Ignatz despises Krazy

and expresses his cynical disdain by throwing a brick at the androgynous Kat's

head. Krazy, blind with love, awaits the arrival of the brick (indeed, pines

for its advent) with joy because he/she considers the brick "a missil of

affection." Meanwhile, the dog, motivated by inclination (his love for

Krazy) as well as occupation (he's an enforcer of law and order) tries to

prevent the disorders that Ignatz attempts to perpetrate on Krazy's bean.

Ironically,

in seeking to protect the object of his affection from the assaults of the

mouse, Offissa Pupp succeeds in making his beloved Krazy happy only when he

fails to frustrate Ignatz's attack. Luckily, Offissa Pupp frequently fails in

his mission. And Ignatz, perforce, succeeds. But it is Krazy who triumphs.

As Seldes said: "The incurable romanticist, Krazy faints daily in full

possession of his illusion, and Ignatz, stupidly hurling his brick, thinking to

injure, fosters the illusion and keeps Krazy `heppy'."

Hence,

Herriman's theme: love always triumphs. And most of the time, it does so in

the strip more by accident than by design. Over the years, Herriman played out

his theme in hundreds of variations, but there was always the Kat, the Mouse,

and the brick. And the brick usually found its way to Krazy's skull— much to

the Kat's content (and often to Offissa Pupp's chagrin). The acclaimed

lyricism of Herriman's strip arises partly from the seemingly endless reprise

of this theme as Seldes first outlined it. But it arises, too, from the theme

itself and Herriman's unique treatment of it.

For

we are all of us lovers, seeking someone to love and to love us back— and

fearing an unrequited outcome. That we should find humor in a comic strip

about love that is requited more by accident than by intention is something of

a wonder. True, there is some reassurance in the  endless victories of love in Krazy

Kat. But the accidental nature of so many of those triumphs cannot but

undermine a little an over-all impulse towards confidence. And hope. And yet

we laugh. Perhaps because we are all of us lovers, and just a little krazy in

konsequence. And so like Herriman's sprite, we persist in seeing only what we

want to see. endless victories of love in Krazy

Kat. But the accidental nature of so many of those triumphs cannot but

undermine a little an over-all impulse towards confidence. And hope. And yet

we laugh. Perhaps because we are all of us lovers, and just a little krazy in

konsequence. And so like Herriman's sprite, we persist in seeing only what we

want to see.

By

this circuitous route, Seldes' interpretation of Herriman's theme is

embellished. Krazy Kat is not so much about the triumph of love as it

is about the unquenchable will to love and to be loved. Love may not, in fact,

always triumph; but we will always wish it would.

HERRIMAN'S

PAEAN TO LOVE began as a simple cat-and-mouse game in the basement of a strip

called The Family Upstairs, which first appeared August 1, 1910. The

strip had debuted under the title The Dingbat Family on June 20, 1910,

but when the apartment-dwelling Dingbats developed an obsession about the disruptive

doings of their upstairs neighbors, the strip was re-titled accordingly. Krazy

first appeared (unnamed) as the Dingbat's cat in the first week of strips. The

spacious panels in which Herriman recorded the daily trials of the Dingbats in

their feud with their neighbors always had some vacant space at the bottom, and

Herriman developed the practice of filling that space with drawings of the

antics of the cat (not yet Kat). On July 26, a mouse appears and throws what

might be a piece of brick at the cat. Thereafter, the drama that unfolds at

the feet of the Dingbats focuses on the aggressive mouse's campaign against the

cat.

By

mid-August, Herriman had drawn a line completely across the lower portion of

his strip, separating the cat and mouse game into a miniature strip of its own,

a footnote feud paralleling the combat going on above. This tiny strip

Herriman introduced with the prophetic caption: "And this," with an

arrow pointing to the strip at the right, "another romance tells."

And the mouse ends that day's antics by christening his nemesis: "Krazy

Kat," he growls, somewhat disgustedly. This exasperated utterance would

become the strip's concluding refrain and, eventually, its title. But for the

next two-and-a-half years, the Kat and the mouse carried on in their minuscule

sub-strip without a title, and the mouse didn't acquire his name until the

first days of 1911. On rare occasions, Ignatz and Krazy invaded the Dingbats'

premises, taking over the more commodious panels upstairs for their daily turn

while the baffled Dingbats looked in from below.  But it wasn't until October 28, 1913, that

they had a strip of their own. But it wasn't until October 28, 1913, that

they had a strip of their own.

Krazy’s

relationship to Ignatz was initially that of the persecuted and abused. The

Kat’s infatuation with the mouse did not become evident until the spring of

1911, and even then, it was only occasionally alluded to. It did not become an

obsession until later that year. In the Gallery at the end of this essay is a

selection of strips from the first couple years, showing the evolution of the

krazy love affair.

The

machinations of his eternal triangle (and the brick) preoccupied Herriman

throughout Krazy Kat's run. And most of the strips, whether daily or

weekend editions, are stand-alone, gag-a-day productions. But on occasion,

Herriman told continuing stories. Once Krazy was captivated by a visiting

French poodle named Kisidee Kuku. And in 1936, Herriman conducted one of his

longest continuities— a narrative opus chronicling the havoc wreaked by Krazy's

involvement with the world's most powerful katnip, "Tiger Tea."

Mostly, however, the strip was a daily dose of Herriman's lyric comedy about

love.

Herriman's

graphic style— homely, scratchy penwork— remained unchanged through Krazy

Kat's run, but the cartoonist explored and exploited the format of his

medium, exercising to its fullest his increasingly fanciful sense of design—

particularly when drawing the Sunday Krazy.

The

first "Sunday page" didn’t appear on a Sunday: it showed up on

Saturday, April 23, 1916, running in black and white in the weekend arts and

drama section of Hearst's New York Journal; the full-page Krazy would not be printed in color until June 1, 1935. But with or without color,

the full-page format stimulated Herriman's imagination, and for it, he produced

his most inventive strips— in both layout and theme, the latter often playfully

determined by the former, as we shall see anon.

While

the brick is the pivot in most of Herriman's strips, the daily strips also

reveal him playing with language and being self-conscious about the nature of

his medium. When Ignatz casually observes that "the bird is on the

wing," Krazy investigates and reports (in characteristic patois):

"From rissint obserwation, I should say that the wing is on the

bird." Another time, he is astonished at bird seed— having believed all

along that birds came from eggs.

In

Krazy's literal interpretation of language there is an innocence at one with

his romantic illusion. When Ignatz is impressed by a falling star, Krazy

allows that "them that don't fall" are more miraculous. Krazy's puns

and wordplay were the initial excuse for Ignatz's assault by brick: the mouse

stoned the Kat to punish him/her for what he considered a bad joke. From this

simple daily ritual, Herriman vaulted his strip into metaphysical realms and

immortality.

Appropriately

enough, illusion and reality meet in a dreamscape where the distinction between

them becomes forever lost, the perfect denouement for the topsy-turvy

relationship among Herriman's trio of protagonists. Seldes drew attention to

the "shifting backgrounds" in Krazy Kat— to scenery that

changes from mountain to forest to sea at will, to suit Herriman's whim for

varying his designs. Very early, in both daily and weekend installments,

Herriman invested his strip with a dream-like ambiance: evoking his favorite

retreat, Monument Valley in the desert of southeastern Utah, he created a

Surreal landscape of whimsical buttes and cavorting cactuses that changed their

shapes and moved around from panel to panel as his characters capered before

it, entirely oblivious to the metamorphosis of their background. In the radiant

absurdity of this symbolic site, the Herriman's lyricism was complete: setting

and content were a seamless whole, locale and refrain united in thematic

reprise. Here, Herriman's dream becomes an amiable reality.

In

addition to being a conglomeration of geological oddities, Monument Valley is a

desert. Its landscape is parched and vast; its human population, sparse.

Here, dwarfed by craggy monuments and isolated from the normal bustle of social

enterprise, the solitude and insignificance of individual existence becomes a

palpable thing. Baking in the desert sun, soaking up the peace and majesty of

the place and finding withal a kind of serenity, one can come to a great

appreciation of the fellowship of humankind— perhaps to an understanding of the

role of love in that fellowship.

Whether

Herriman experienced precisely these feelings we cannot say, but he was clearly

moved by the beauty of the area: "Those mesas and sunsets out in that ole

pais pintado," he once wrote, "a taste of that stuff sinks you ...

deep too...." For twenty years, he made an annual pilgrimage every summer

to Monument Valley, where he stayed in Kayenta with John and Louisa Wetherill,

who had started a Navajo trading post there in 1910. Cartoonists James

Swinnerton and Rudolph Dirks sometimes accompanied him. And they all painted

landscapes a little (Herriman less than the other two).

A MULATTO,

Herriman is the first person of color to achieve prominence in cartooning.

(Although recognized for his talent by his peers and by the press and the

public in a general way, his stature is largely a posthumous distinction.

During his lifetime, Herriman's work was esteemed by intellectuals, but their

high opinion of Krazy Kat did not translate into circulation: Krazy

Kat appeared in very few newspapers, relatively speaking. Ron Goulart,

in his Encyclopedia of Comics, says the strip never ran in more than

forty-eight papers in this country. Half of them were doubtless in the Hearst

chain, which numbered about two dozen at its peak. Hearst loved the strip and

insisted that he would keep running it as long as Herriman wanted to do it,

circulation notwithstanding.) Herriman is reported to have said he was Creole

but of mixed blood. He was probably one of the "colored" Creoles who

lived in New Orleans at the end of the nineteenth century— descendants of

"free persons of color" who had intermarried with French, Spanish,

and West Indian stock.

Herriman

was clearly sensitive about his racial origins. He had kinky black hair and

almost always wore a hat— indoors and out— probably to conceal the fact. By

all accounts, he was self-effacing, shy, and extremely private.

Herriman's

race would be of no particular interest were it not for the unique

manifestation he created for love in his strip: Krazy chooses to take an

injury (a brick to the head) as symbolic of Ignatz's love for him/her, and

Krazy is a black cat. While I would hate to see Krazy Kat converted by

well-meaning critics and scholars into an allegory about racial relations (it

would then seem somehow less universal in its message, and we all need its

reassurances, regardless of race), Herriman's sensitivity on the matter

suggests an unconscious emotional source for his inspiration. He may not have

been fully conscious of the kind of self-hatred that racial prejudice induces

in persecuted minorities, but his subconscious knew. And on the murkier levels

of the subconscious, self-hatred is associated with guilt, and guilt requires

punishment. And thus the brick, erstwhile emblem of love, becomes the

instrument of punishment. But not altogether: perhaps to Ralph Ellison's

invisible man, even abuse is a form of acknowledgement and is therefore to be

desired if all other forms fail to materialize.

African

American scholars see other artifacts of life in black America in the strip.

William W. Cook, a Dartmouth scholar of African-Americana, told me about the

comedy of reversal that Krazy Kat seems to embody. Among the characters

that populated the vaudeville stage in the early years of the twentieth century

were comic racial stereotypes left over from the days of minstrelsy. A large

imposing black woman and her diminutive no-good lazy husband comprised a

traditional stage pair. The comedy arose from the woman's endless beratings of

her husband and his ingenuity in evading the obligations she urged upon him.

Noting Krazy's color and size relative to Ignatz, Cook sees the large black

woman of the vaudeville stage in the Kat; and in the mouse, the wizened

husband. In Herriman's vision, however, their vaudeville roles have been

reversed: with every brick that reaches Krazy's skull, the browbeaten

"husband" avenges himself for the years of abuse he suffered on

stage. And Offissa Pupp is another vestige of the same vaudeville act: driven

to distraction by her husband's derelictions, the scolding stage wife often

concluded her rantings with the threat: "I'm gonna get the law on

you."

But

the strip's central ritual has a more obvious origin in another more familiar

vaudeville routine. We see it first in Bud Fisher's Mutt and Jeff. The

pie-in-the-face punchline. Mutt habitually hits Jeff after Jeff makes a

particular stupid remark, an echo of comedy on the vaudeville stage. Ignatz's

brick-throwing belongs in the same tradition. Krazy would say or do something

silly or idiotically insightful, and Ignatz would react by braining him with a

brick. It was a commonplace of comedy in those years (and to a large extent,

it still is). But Herriman, as we've seen, gave the slapstick routine a

metaphysical significance it never had on stage. And the lyric lesson came

about, I believe, through the cartoonist's impulse for visual comedy.

THE SUNDAY OR

WEEKEND full-page Krazy Kat is the fly wheel of the strip's lyric

dynamic. And it was on these pages that Herriman developed and embroidered the

strip's over-arching theme. By the time the weekend strip was launched, Krazy was five years old. In its daily version, the strip reprised its familiar

vaudeville routine with an almost endless variety of nuance. The love that

this routine obscurely symbolized was only hinted at in the daily strips. But

when Herriman gained the expanded vistas of a full page upon which to work his

magic, his grand but simple theme began to emerge in full flower. And before

too long, the weekend strip was a page-long paean to love—to its power, to our

passionate and unwavering desire for its power to triumph over all.

I

suspect that the gentle theme of love emerged on the weekend pages almost

accidentally. Judging from the earliest pages themselves, Herriman's driving

preoccupation was a playful desire to fill the space by humorously re-designing

it— and while he was about it, he re-designed the form and function of comic

strip art as well. Beginning with the first weekend page in 1916, we can watch

Herriman as he started to experiment with the form of the medium. Antic

layouts were not long in surfacing.

On

the very first weekend page, April 23, 1916, he used irregular-shaped panels,

and by June, some panels were page-wide. In July, he sometimes dropped panel

borders and sometimes used circular panels instead of rectangles; by August, he

was mixing all these devices. And by the end of October, his graphic

imagination was shaping the gags: layout sometimes determined punchline or

vice-versa as page design became functional as well as fanciful.

On

the page for July 9, 1916, page-wide panels emphasize the vastness of the

desert setting.  The opening panel the next week is likewise a whole page wide by way of

dramatizing a gag: a fatuous ostrich performer on stage addresses his

"vast and intelligent audience," which consists solely of Krazy,

whose solitude and inconsequence, in comic contrast to the ostrich's remarks,

is made hilariously plain by the emptiness around him that stretches all across

the page. The opening panel the next week is likewise a whole page wide by way of

dramatizing a gag: a fatuous ostrich performer on stage addresses his

"vast and intelligent audience," which consists solely of Krazy,

whose solitude and inconsequence, in comic contrast to the ostrich's remarks,

is made hilariously plain by the emptiness around him that stretches all across

the page.

On

September 3, Herriman sets the scene for an adventure at sea with a page-wide

panel suggesting the vast and vacant reaches of an ocean. Panel borders

disappear for much of the page in order to give emphasis to the unruly waves

that toss Krazy and Ignatz about. Then, for the conclusion, panel borders

frame a scene when the sea has grown calm.

On October 15, the entire page

consists of page-wide panels. The maneuver permits Herriman to tell one story

about Krazy at the far left of each panel while unfolding an ironic comedy in

counterpoint at the far right. The humor arises from the simultaneity of the

actions.

On

May 6, 1917, a top-to-bottom vertical panel on the right-hand side of the page

gives the comic explanation for the "mystery" outlined in the panels

on the left: how could a single brick from Ignatz bean a katbird, Krazy, and a

katfish? The vertical panel allows Herriman to explain.He shows Ignatz in a balloon over

Krazy's head and traces the path of the brick he drops from the balloon: it

hits a passing katbird first, then Krazy, then falls into the water where it

hits the katfish. katfish? The vertical panel allows Herriman to explain.He shows Ignatz in a balloon over

Krazy's head and traces the path of the brick he drops from the balloon: it

hits a passing katbird first, then Krazy, then falls into the water where it

hits the katfish.

The

next week, layout also contributes to the comedy. The bottom third of the page

is a series of drawings large enough to show Krazy bemoaning his banishment

from Ignatz at the bottom of the drawings while, simultaneously at the top of

each drawing, the usual missive of the mouse's regard is being launched in the

Kat's direction by forces over which neither Kat nor mouse has any control.

That

the stories Herriman told on the weekend Krazy Kat focussed on love is

largely incidental. Love is any storyteller's stock-in-trade. Love insinuates

itself into most human dramas. In many ways, all stories can be love

stories—as soon as the opposite sex appears or children enter a family milieu.

Love stories find their way into virtually every other kind of tale. They fit

readily into any narrative setting. War stories have love stories as subplots;

so do Westerns and whodunits and every other kind of narrative. The theme of

love is thus universal enough to furnish a focus for any story. Herriman's

sense of graphic play needed a narrative focal point. Love was the most easily

understood and adaptable organizing device at hand. Herriman seized it, and,

by making it central to an endless comic refrain, he made poetry.

On

the weekend pages, Herriman found room to indulge and develop his fantasy— his

visual playfulness, his inventiveness. His poetry. Here, then, the

quintessential Krazy blossomed. And then the daily strips took up the

chorus too, more focussed than they had been before Herriman had the weekend

page to play with. The lyricism of the theme soon permeated Herriman's week

and gave us one of the masterworks of the medium.

But

these are the maunderings of the critical faculty. For the readers (and

lovers) we all are, it is probably enough to know that regardless of the source

of Herriman's inspiration, his Kat, the embodiment of love willed into being,

is a comfort to us all— a balm of wisdom wrapped in laughter. Herriman was not

only shy: he was, according to those who knew him, also saintly. And so was

his strip.

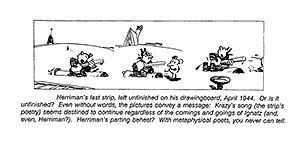

Herriman

died April 25, 1944, and his strip, too idiosyncratic for another to continue,

ceased with the Sunday page for June 25. But in soaring into metaphysical

realms, Krazy Kat had long since achieved immortality.

And

now, in a Krazy Gallery assembled from the Hyperion Press reprint tome, The

Family Upstairs: Introducing Krazy Kat, we show the evolution of Herriman’s

most celebrated characters with sundry hints of their situation during the

first months of the strip, 1910-1912. These excerpts appear here in the same order

in which they were initially published, and they show Herriman becoming

increasingly playful in the deployment of his medium’s visual resources—a broad

hint about things to come in the “weekend” Krazy of later years.

Fitnoot. The foregoing essay is a somewhat

reduced version of a chapter in a book of mine, The Art of the Funnies, which

(shameless plug) is offered for sale hereabouts.

Return to Harv's Hindsights |