HUMORAMA AND ME

A Nostalgic Meandering

WE’VE CELEBRATED Playboy long enough. A couple generations of attention is plenty. Its day is gone (although its place in magazine history is secure; nobody has done what Hugh Hefner did). Its cartoon artistry—the brilliant watercolor drawings of Jack Cole —has evaporated. And Esquire long ago faded from newsstands everywhere; today, it’s merely a men’s fashion magazine with outlandish page layouts.

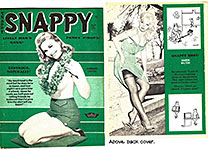

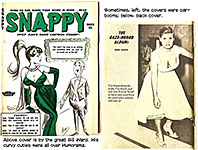

But we haven’t celebrated Humorama nearly at all. Humorama published a score or more cheap digest-size girlie magazines with an assortment of short titles—Breezy, Comedy, Eyeful of Fun, Jest, Joker, Laugh Circus, Gaze, Stare, Romp, Snappy, Zip and so on. Each title ran to about 100 4x6-inch pages and sold for 35 cents. The pages were filled with black-and-white photographs of pin-up girls in scanty attire—Bettie Page, Eve Meyer, stripper Lili St. Cyr or wannabe actresses like Loi Lansing, Tina Louise and Julie Newmar. And full-page cartoons.

|

|

Mostly cartoons.

There were verbal jokes, too, and one-liners sometimes spilled over to the tops of pages otherwise devoted to photos, but the visual content was what sold the magazines.

There was some variation between titles: Gaze and Stare had more photos and fewer cartoons; Joker and Jest had more cartoons and fewer photos. But the content varied with consumer appetites through the years, so we couldn’t tell with precision about the emphasis of any given title.

Humorama flourished through the 1950s and into the 1960s. It was part of Martin Goodman’s publishing empire (which included Marvel comics) and was headed by a relative, Abe Goodman, reportedly Martin’s brother.

Introducing the Fantagraphics Pin-Up Art of Humorama, editor Alex Chun says Humorama was started in 1938 and ran into the 1980s. The women in the photos were nakeder and nakeder in the 1960s and 1970s, and there were more photos and fewer cartoons, indicating a shift in the magazine market. By the 1980s, though, the shift swung the other way—more cartoons and fewer photos.

Humorama mags were at the bottom of The List.

Freelance cartoonists (and probably photographers) listed the magazines that comprised their market, beginning with the magazines that paid the most. Those were at the top of The List. Humorama was at the bottom.

Only one market was lower on The List than Humorama. That was Sex to Sexty, published in Texas. Humorama paid $5 for a cartoon. Sex to Sexty paid less—$2 maybe.

When peddling his wares, a cartoonist started at the top of his list with the magazines that paid the most. Back in 1959 when I first ventured into this arena, the best-paying magazines were The New Yorker and Playboy. They paid hundreds. After that came Penthouse, Cavalier and other Playboy imitators, general interest magazines like Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s, Look, National Enquirer, Saturday Review, even syndicates, King, Sun Times, followed by the rest. Saturday Evening Post paid $25-50, maybe $100, depending (although my memory is faulty on the Post). National Enquirer paid surprisingly high rates.

If you didn’t sell anything to the magazine at the top of The List, you went down The List to the next highest-paying. And from there, you went the rest of the way down The List, hopefully selling a cartoon here and there as you went. Then you got to Humorama mags.

Humorama bought only slightly risque cartoons about sex and statuesque babes. If you did cartoons that dealt with everyday life around the home, those were appropriate for Saturday Evening Post and Collier’s et al. Not for Humorama. Although Humorama occasionally published such general interest cartoons, they weren’t really appropriate for its readership of heavy-breathing men.

But

general interest cartoons were definitely not for Sex to

Sexty. I have a big 1967 book that reprints pages of Sex to Sexty magazines, binding many of them together between hard covers, and looking

through it the other day, I was mildly  shocked to see cartoons that were

grossly sexual, very crude. I can’t imagine a cartoon intended for Playboy that would have trickled down The List to get to Sex to Sexty.

shocked to see cartoons that were

grossly sexual, very crude. I can’t imagine a cartoon intended for Playboy that would have trickled down The List to get to Sex to Sexty.

Playboy and its imitators in those years—Penthouse, Cavalier, Dude, Gent, Fling, Hustler, Adam etc.—were relatively sophisticated compared to Sex to Sexty. If Playboy kissed, Sex to Sexty groped with both hands while unbuttoning its fly. One of these days, we’ll post a healthy helping of their raucous cartoons here. Until then, we’ve squeezed in a couple near here as the merest hint of things to come.

SOME CARTOONISTS WHO WORKED THE GIRLIE MARKET also worked the general interest market—Saturday Evening Post, National Equirer, and the like. And they maintained two lists, one for girlies and one for generals, and batched their cartoons accordingly.

New York was then home to more magazine publishers than any other city. Cartoonists who lived in Manhattan or close enough to commute to the City would take their cartoons in person to magazine editors’ office, hoping to sell some. Editors held open house on Wednesdays— which was “Look Day” for cartoonists. They would bring into town batches of cartoons—10-20 cartoons in a batch—to show editors.

Editors would flip through a batch of cartoons, and if they saw something they liked, they’d buy it. Most cartoonists presented only rough sketches of cartoons, so if an editor liked something, the cartoonist would take the editor’s choice back home to do a finished drawing and bring that in on the next Look Day. Sometimes an editor would “hold” a cartoon for a week or so until he decided either to buy it or reject it.

After graduating from college in 1959, I knew I would be drafted into military service within a few months, but I had an opportunity in the fall to go to New York, and I took the opportunity, thinking I’d freelance cartoons while there and try to break into the market. I had the vague idea that if I sold a few, I could then continue to sell while in the military—only by mail then instead of in person.

I concentrated on girlie/men’s mag cartoons. But I never went to Playboy to sell: at the time, Playboy didn’t have offices in New York.

Twenty years later, I returned to freelancing cartoons to magazines, this time, doing it through the mail. I produced one batch of generals and then a batch of girlies. And when the girlies sold better than the generals, I concentrated on girlies and did a general batch only every so often.

In the girlie/men’s mag market, I was selling pretty good—68%; and it was variously rumored that if you sold 50%, you were a roaring success. So I was doing better than roaring in the men’s mag market. Generals, not so good. My records say just 28%. But combined, I was selling 51%. So even incorporating generals, my sales record was pretty decent.

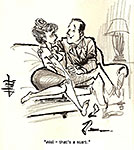

But back in 1959, all my cartoons were aimed at the men’s magazine market, and I wasn’t selling nearly as well. Nearby, I’ve posted some samples of my cartoons of that day.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The subject of many of them was a pretty girl, not in any dishabille or naked; in others, the topic was sex even if no babe appeared in the picture.

Some of the cartoons posted nearby are in a more preliminary state than others: parts of the drawing are still in pencil or are rendered in gray tone wash. My New York freelance cartoons are distinguished by a signature unusual for me: just “Harv” turned sideways and lettered in bold brush strokes, attempting to evoke Chinese calligraphy. I also drew with a ragged line that I created by “scrubbing” the line with my brush.

I worked up ideas for cartoons and drew them up Monday, Tuesday, Thursday and Friday. On weekends, I went sight-seeing in New York. Wednesdays, I went knocking on cartoon editors’ doors.

I STAYED IN NEW YORK from September to mid-November. I finally sold a cartoon to DuGent, a portmanteau word that recognized Dude and Gent, two of the magazines that the publisher of the somewhat higher class Cavalier produced. Cavalier was third or fourth down The List after Playboy in those days

I

didn’t do “roughs”: because I was entirely unknown, I thought I’d have a better

chance of selling if I finished the art to show an editor what I could do. The

cartoon editor at DuGent liked one of my cartoons and asked if my finished art

would look any different. I said “No,” and he took the cartoon as it was.

I can’t

remember if I collected a check at the point of sale or if it was mailed to me.

But I remember the amount. Twenty-five bucks. My first sale.

I can’t

remember if I collected a check at the point of sale or if it was mailed to me.

But I remember the amount. Twenty-five bucks. My first sale.

Although the cartoon was one of my “roughs,” it wasn’t as rough as some of the others we’ve looked at in which parts of the drawing are still in pencil or done entirely in the gray tones of a wash.

I also sold a couple to Humorama but not right away. I have a distinct memory of the Humorama office. It wasn’t much. On an upper floor at 667 Madison Avenue, it seemed to occupy only one room. When I got to the Humorama door, I opened it and went in, expecting to find myself, as I did everywhere else, in a reception area where I’d sit and wait my turn to see the cartoon editor.

Not at Humorama.

I walked right into the “office,” which consisted of a few desks, all littered with papers. The place was deserted except for one somewhat stout man, who, in my memory, stood amid the desks in his shirtsleeves, smoking a cigar.

When I told him I had some cartoons, he held out his hand, I gave him my file folder (my batch), and he thumbed through it while standing and returned it to me, saying, “Better luck next time, kid.”

Or some such.

Ever since then, whenever I recall the incident, I imagine that the man who rejected my cartoons was Abe Goodman. But now as I conjure up memory of the meeting, I realize that it could have been someone else, just some random Humorama employee in the otherwise empty office.

So my work was being rejected by —who? The janitor?

Could have been for all I know.

When I left New York in early November, I went back to Denver, my hometown, but since my parents had moved to Kansas City, I took a room in a downtown hotel, the Court Place Hotel on Court Place.

It was a transient hotel for people like me who needed a cheap room for a week or so at a time. My room, which was surprisingly spacious, had a table and chair, a sink with a mirror over it and running water, but no toilet. Those were in another room down the hall. In the other direction was a room with showers.

No tv in the room, but at the end of the hall was the “tv room” where residents could go to spend an evening. I went only a couple times. The room was kept dark to improve the image on the screen—so dark that I couldn’t see if there were any empty chairs or couches in the room. I was always afraid of inadvertently sitting on someone.

Once, looking down the hall from the tv room, we saw the police calling on a resident. Just like on television or in the movies, two cops stood on each side of the door. One knocked, and when the resident opened the door, the cops showed him their badges and they all went into the room.

While in Denver, I freelanced cartoons some more, this time by mail.

It

was from Denver that I sold a couple of cartoons to Humorama—as you can see by

the acceptance form that I’ve posted hereabouts.  One of the forms had plenty of numbers

on it that the editor could circle, signaling how many of your batch he’d

bought. As you see, each time ol’ Abe bought one, he circled a number for the

quantity purchased, or penciled the number in.

One of the forms had plenty of numbers

on it that the editor could circle, signaling how many of your batch he’d

bought. As you see, each time ol’ Abe bought one, he circled a number for the

quantity purchased, or penciled the number in.

Alas, I didn’t keep copies of any of my sold cartoon originals, so I can’t post them here. (The cartoon I sold to DudeGent is reproduced here from its printed incarnation in Gent.) But I can cull from my vast library of Humorama magazines a healthy sample of a title’s typical contents, and so I have, and the results are posted down the scroll a little more.

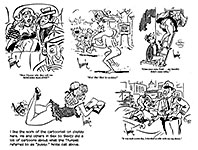

Among the cartoonists to be found frequently in Humorama titles were Bill Ward and Bill Wenzel. Famous for his deployment of conte-crayon for gray tones, Ward had left comicbooks when Fredric Wertham’s assault on the industry helped drive some publishers out of the business. (Television also helped drive them out.)

Ward was renowned for the size of the knockers on his uber maidens. He once explained that Humorama kept hounding him to increase the girls’ buxomness because readers demanded it. I guess they were all tit men.

Wenzel’s girls were similarly endowed, but Wenzel spent less time lovingly detailing the dimensions of his babes. His style was breezy and looked dashed off, and his gray wash was expertly applied. And his girls were as famous for their long legs as for their bosoms.

Together, according to Chun, Ward and Wenzel produced more than 15,000 cartoons in Humorama books.

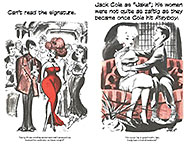

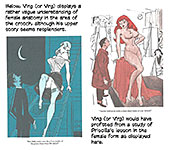

Jack Cole drew cartoons for Humorama, using the pen-name “Jake” (his wife’s nickname for him saith Chun). Dan DeCarlo often escaped Archie titles to do statuesque femmes for Humorama, signing “DSD” for his given name, Donato Salvatore DeCarlo. His female assistant once bought one of my girlie cartoons for DeCarlo when I was exhibiting at the Chicago Con, saying Dan liked cartoons with pretty girls in them.

Years later, DeCarlo was at the San Diego Con, selling prints of a couple of his girlie cartoons. I bought one and asked if he’d inscribe it to me.

“What should I write?” he asked.

“Write ‘Here’s how to draw a pretty girl’,” I said.

And so he did.

The rest of the roster of Humorama tooners includes Vic Martin, Basil Wolverton, Mad’s Dave Berg (that surprises me), Stan Goldberg (another Archie artist), Jim Mooney (who signed with a crescent moon), and Jefferson Machamer.

Now let’s conclude with an extended gallery of Humorama content, cartoons mostly but a few b/w photos, too, just for authenticating the flavor. This is more than a picture gallery: my captions carry on with the history of the publisher and the cartoonists.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|